Abstract

As shown in research and practice digitalization processes are many times limited to implementation of digital technologies without pedagogical and organizational change. In this study it is argued for a broader perspective on the concept of digitalization, viewing it as a process involving change and transformation in different stages and several organizational levels. Based on cultural–historical activity theory and the concept of levels of learning, this study will elaborate on the concept of digitalization as well as how schools are dealing with digital and educational change. Two schools known for their large-scale digitalization processes are analyzed. In the analysis, it is indicated that the object of digitalization harbors an idea that influence how digitalization is planned for and enacted within the school organization. How schools conceptualized—what is theoretically and practically meant by digitalization—influence how they plan their budget, professional development, and organizational change. With this backdrop, it is a concluded need for explicit discussions and conceptual clarifications on what digitalization is and what it involves in different school contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The development and use of digital technologies have spread like waves over schools and society (Jedeskog, 2005). Rapid growth and enhanced access to technologies are said to pose new possibilities to teach and learn (cf. Jahnke et al., 2017). Simultaneously, the integration of digital technologies in schools has been reported to be a complicated process. Several researchers report that digitalization initiatives have difficulty gaining sustainability in schools (Aesaert et al. 2015; Hauge 2014; Håkansson Lindqvist 2015) and that the technologies implemented tend to support and reproduce previous practices rather than developing new ones (Glover et al. 2016).

In their studies Agélii Genlott and Grönlund (2016) and Glover et al. (2016), argued that digitalization that is not rooted in pedagogical objects and methods can fail to transform practice and enhance students’ learning. In a research review, Islam and Grönlund (2016) continued this discussion by concluding that there has been an extensive focus on aspects of technology and that technology-use itself do not result in change and development in educational practice. Islam and Grönlund (2016) go on to say that practice and future research should focus on pedagocal, organizational and leadership aspects and “their contribution to improving and disseminating good pedagogy” (p. 216).

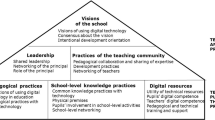

For digital transformation to take place, some researchers argue that change and support must occur at several organizational layers (cf. Pettersson 2018b; Vanderlinde and van Braak 2010), including organizational, cultural, and administrative change (Blau and Shamir-Inbal 2017; Vanderlinde and van Braak 2010; Zhang 2010). As argued by Hauge (2016), digitalization should be considered an organizational task, including various levels and competences acting within the school organization. In a similar line of thought, Pettersson (2018b) studied how schools could be strategic in enacting resources, structures, and activities to support actors, practices, and structures and establishing pedagogical and organizational objects that drive digital and educational change in schools. However, few studies have conceptualised the digitalization process via an organizational and multilevel perspective on change and transformation.

In this study, we elaborate on the concept of digitalization, viewing it as a process involving transformation in various steps and on several organizational levels. To this end, cultural–historical activity theory (CHAT; Engeström 1987; Leont’ev 1978, 1981; Vygotsky 1978), including the concepts of object, change, and transformation, will be used as an analytical framework, providing an opportunity to study school organizations as collectively created activities. In addition, this study will use the concept of levels of learning (Bateson 1972; Engeström 1987), which should be seen as an attempt to understand steps of transformation in school. Following the introduction above, this study aims to explore and understand structural and educational transformation. More specifically, the aim is to explore how digitalization is conceptualised in school as well as how structural and educational change occur in schools known for large-scale digitalization. The following research questions are raised:

-

How do actors in schools conceptualise the object and process of digitalization?

-

How do teachers, school leaders, and educational technologists deal with digital and educational change, and how do new educational practices and organizational infrastructures occur as part of digitalization?

1.1 Digitalization in school

In previous research, there have been several attempts to understand factors that influence digitalization and educational change in schools, including access to digital technologies (e.g., laptops, tablets, and mobile phones; Håkansson Lindqvist 2015; Hansson 2013), digital competence (e.g., pedagogical digital competences, TPACK, ICT skills; Pettersson 2018a; Aesaert et al. 2015; Hatlevik and Christophersen, 2013; Krumsvik et al. 2016; Mishra and Koehler 2006), development of teaching and learning designs (e.g., flipped classrooms; Lund and Hauge 2011; Olofsson and Lindberg 2014), and organizational or institutional change (e.g., administrational and institutional support, ICT infrastructures, ICT leadership, and ICT school culture; Pettersson, 2018b; Blau and Shamir-Inbal 2017; Ottestad 2008; Vanderlinde and van Braak 2010).

Researchers have concluded that digitalization in school can be a complicated process (Hauge, 2014; Håkansson Lindqvist 2015). Digitalization initiatives have problems gaining sustainability in schools (Hauge 2014; Aesaert et al. 2015), and the technologies implemented and used tend to support previous practices rather than lead to change and development (Glover et al. 2016; Håkansson Lindqvist 2015; Jenkins et al. 2011). The evidence-based research on digital transformation in teaching practices is often small-scale, and the processes are often driven by, and dependent on, individual enthusiasts (Jenkins et al. 2011; Means et al., 2009; see also Cuban, 2013). Cuban (2013) said, for example, that “incremental changes have largely left intact teaching routines that students’ grandparents visiting these schools would find familiar” (p. 112).

In a research review, Islam and Grönlund (2016) concluded that there is an been an extensive focus on aspects of technology. This was confirmed by Haelermans (2017), who continued this line of discussion to say that “having access to ICT in education will not necessarily lead to an effective use of ICT in education” (p. 101). Other researchers put forth the importance of connecting integration of technology to pedagogical objects and methods (Jahnke et al. 2017; Glover et al. 2016). Agélii Genlott and Grönlund (2016) found that digitalization that is not rooted in pedagogical objects often fails to transform practice and enhance students’ learning. Moreover, digitalization in school must be driven by new ways of thinking about teaching and learning. This was confirmed by Pettersson (2018b), who extends this argument to say that digitalization driven by pedagogical and organizational goals and visions can be more effective and sustainable in school. At the same time, two research reviews (Pettersson 2018a; Olofsson et al., 2015) show that digitalization and digital competence have primarily been studied on the level of single groups of actors, and especially teachers.

In their research review, Islam and Grönlund (2016) argued that practice and future research should “focus not only on pedagogical methods but also school organization and leadership and their contribution to improving and disseminating good pedagogy and dismantling bad habits”. (p. 216). From a student perspective, Aesaert et al. (2015) argued that educational research on, for example, digital competences and learning outcomes digitalized environments “should be multilevel in nature.. . reflecting a pupil, classroom, school and overall context level” (p. 327). Aesaert et al. (2015) further argues that focus has primarily been on factors regarding the levels of pupils, whereas “the broader classroom and school context in which pupils are embedded” (p. 327) is not accounted for.

Research shows that digitalization is a complex process requiring large-scale transformative changes (Holmgren et al., 2017; Olofsson and Lindberg 2014; Zhang 2010), and with support from school organizations and leadership (Håkansson-Lindqvist and Pettersson 2019; Kafyulilo et al. 2016). Zhang (2010) go on to say that for deep and sustainable change to be enacted, it must appear at all levels supported by comprehensive system thinking. According to Zhang (2010), such change calls for a close and dynamic interplay between macro and micro processes. However, regarding complex system thinking, Zhang (2010) suggests that schools work toward and support an interplay between various levels of the organization. Following this line of thought, Hauge (2016) suggested an ecological approach that included several organizational levels. To integrate digitalization in schools, Hauge argued for a shared understanding by school leadership, administrators, and development and learning staff, as well as the need to develop common tools for institutional learning. In their study, Vanderlinde and van Braak (2010) developed an e-capacity model reflecting “schools’ abilities to create and optimize sustainable school level and teacher level conditions that can bring about effective ICT change” (p. 543). In another study, Petersen (2014) stated that schools must find ways to formulate goals and transform them into supportive infrastructures for developing actors within the organization. Another example is Blau and Shamir-Inbal’s (2017) study on digitalization, cultural change, and development of ICT cultures in school. A recent research review supported these arguments, concluding that broader organizational perspectives on digitalization and development of digital competence are often limited in research (Pettersson 2018a, 2018b).

In the next section, we will elaborate on the theoretical framework we used to analyse digitalization and transformation in a school organization. The section includes a theoretical elaboration on what the term digitalization might mean in the context of school and how the process of digitalization could be understood in terms of small steps of learning.

1.2 Digitalization in school through the lens of activity theory

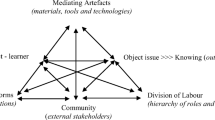

To analyse how digitalization is conceptualised and how structural and educational change occur for teachers, school leaders, and educational technologists, this paper uses the CHAT theoretical framework (Engeström 1987; Leont’ev 1978, 1981; Vygotsky 1978). The theory focuses on formation and development of object-oriented activities, providing an opportunity to study school organizations as activities that are changed and transformed. One of CHAT’s main ideas is that change and transformation are results of human action driven by an object (for example, digitalization, enhanced quality in teaching and learning practices, or enhanced access to teaching and learning) and mediated by culturally developed tools (for example, books, digital technologies, or white boards) (Cole 1996). Vygotsky (1978) described this mediated act as a three-way interaction between the subject, object, and mediating tools. Building on the concept of mediation, Engeström (1987) expanded the theory and structure of activity to include three additional collective forces framing the activity. These forces include rules directing the activity, a community in which the activity is conducted, and the division of labour among actors in the activity.

The dialectical relationship between subject, object, and tools is important from the perspective of CHAT theory. At the same time, a limitation in this field is extensive focus on tools (digital technologies) and subjects (especially teachers) without trying to understand the (pedagogical and organizational) object of digitalization. Thus, this study is an attempt to more explicitly include the object when trying to understand processes of digitalization. An important aspect of understanding the appearance and development of activities is the object of activity, characterizing the aim or goal the subjects attempt to reach (e.g., digitalization as an object in today’s schools). As argued by Kaptelinin and Nardi (2006), an object provides a basis for commitment, priorities, planning, and division of labour and as a tool for interpreting and structuring an activity. Engeström described objects as “concerns; they are generators and foci of attention, motivation, effort and meaning. Through their activities people constantly change and create new objects” (p. 3). Because an object directs activities, planning, and organization, the interpretation of its meaning among participants is important to understanding how and why activities are structured and develop. As argued by Kaptelinin and Nardi (2006), the concept of the object of activity can be a promising analytical tool providing the possibility of

understanding not only what people are doing, but also why they are doing it. The object of activity can be considered the “ultimate reason” behind various behaviours of individuals, groups, or organizations. In other words, the object of activity can be defined as a sense-maker, which gives meaning to and determines values of various entities and phenomena. Identifying the object of activity and its development over time can serve as a basis for reaching a deeper and more structured understanding of otherwise fragmented pieces of evidence. (p. 138)

Hence, more than understanding the tools used to conduct the activity (in this case, digital tools often emphasized in previous studies), the object can be used as an analytical concept for understanding how digitalization is structured and transformed in a specific school context.

For understanding change and development of objects and activities (including tools, rules, community, and division of labour), transformation forms another central concept of CHAT theory (Engeström 1987). The transformation of activities as a result of expansive learning is described as rare, deep, and comprehensive changes in human practices, meaning that previous structures and components of the activity system are reconstructed. Engeström (2001) described this process as follows:

Activity systems move through relatively long cycles of qualitative transformations. As the contradictions of an activity system are aggravated, some individual participants begin to question and deviate from its established norms. In some cases, this escalates into collaborative envisioning and a deliberate collective change effort. An expansive transformation is accomplished when the object and motive of the activity are reconceptualized to embrace radically wider horizon of possibility than in the previous mode of the activity. (p. 137).

In the context of school and digitalization, transformations could take shape as new knowledge and practices of teaching, learning, communicating, and organizing work in school. However, as a productive but painful and comprehensive process taking place in a previously described inert system with strong norms and visions of teaching and learning (cf. Cuban, 2013), processes of transformation can be somewhat rare in schools. Thus, the concept of transformation will in this study be dismantled into smaller analytical entities. In the early development of CHAT, Engeström (1987) used and developed the concept of levels of learning (Bateson 1972) for describing smaller steps or appearances of transformation. In his thesis, Engeström described these steps as Learning I, Learning IIa, Learning IIb, and Learning III. The first, Learning I, is described as minor implementations or “extremely slow and gradual improvement of tools” (Engeström 1987, p. 145). Learning II, as a more demanding step of change, was divided by Engeström (1987) into two forms: Learning IIa as a reproductive step and Learning IIb as a productive step. As a reproductive step, Learning IIa include implementation of tools (in this case, digital) without a change in practice (for example, teaching). Learning IIb, on the other hand, is characterized by experimenting with new methods and practices by reflecting on and reformulating the old. In comparison to Learning IIa, Learning IIb results in larger changes, such as new teaching practices and routines in the activity system. Learning IIb is limited to change on the individual level but can, when moving to a collective level, result in Learning III. As expressed by Engeström (1987) “creation of new instruments within Learning IIb is potentially expansive – but only potentially” (p. 149). Learning III includes the transformation of the whole activity system, including qualitative changes in object, practice, and cultural patterns of activity (Engeström 1987, 2001) (Table 1).

To sum up, conceptualising digitalization as emerging through smaller steps can enable analysis of a gradual digitalization, even though it might not end up with a complete transformation in school. The analytical focus in this study is how teachers, school leaders, and educational technologists understand the object of digitalization, how schools are implementing digital and educational change, and how new practices and infrastructures occur as part of digital transformation in schools. This, in turn, is expected to contribute to a picture of various levels of learning and thereby steps of transformation in school.

2 Method

A demonstrated in previous research, results of digitalization in school are primarily comprised of technical development characterized by lower levels of change, such as in Learning I and IIa. In this study, data were therefore generated from schools known for their digitalization processes with the attempt to capture and analyse higher and more complex levels of change and, moreover, how the object of digitalization is conceptualised in practices where digitalization seems to be more than technical implementation. Thus, this study is based on data from two Swedish upper secondary schools in two municipalities with experiences from 1:1 projects, development of remote teaching, and implementation of new learning and administration systems. Selection of respondents was based on an attempt to capture digitalization from an historical perspective (actors working over a longer period in or in relation to the school) and on various levels (teachers, administrators, school leaders, and educational technologists/digital strategists on local and regional municipality levels). Fifteen in-depth interviews (Kvale 2009) were conducted with teachers (N = 8), school leaders (N = 2), educational technologists/administrators working in local schools (N = 3), and educational technologists/digital strategists working at community/municipality levels (one of them for the education committee and responsible for leading digitization work) (N = 2).The respondents had been working between 1 and 30 years in or in relation to one of the two schools. As a background to the interview study and to deepen the analytical understanding, documents (ICT policy plans, educational development projects, etc.) were reviewed.

The semi-structured interview guide (Kvale 2009), including preformulated and follow-up questions, was informed by CHAT and, in broad terms, concerned the object of digitalization, challenges, and change related to digitalization within the two schools. For example, the respondents were asked about object of digitalization in their school and for their specific role/practice, how the object (including digital, educational, and organizational needs) had been discussed and elaborated on now and over the years (on individual and collective level), how their schools had been dealing with digital solutions and what support that had been available. Respondents were also asked to describe problems and difficulties when trying to integrate digital technologies at various organizational levels, examples of change in school and in their practices and what has been important to put forth such change.

2.1 Analysis of data

The interviews lasted between 39 and 82 min and were transcribed in their entireties. To analyse the data, a content analysis of coding and categorizing was conducted (using Nvivo) focussing on aspects of change, transformation, and support. As a first step, sentences and parts of text were coded by clustering them into broad provisional categories with names describing the content (see examples of categories). This process went back and forth, resulting in 16 categories. Categories indicating similar types of change were thereafter clustered and resulted in three broad themes: changes in teaching and learning (examples of categories: student-centred learning, digital course material, flexible teaching, interactive feedback, communication with students), change in administrative infrastructures (examples of categories: administrational overview, internal and external communication, digital planning, digital platforms, other administrative systems), and changes in organization and support (examples of categories: student support, teacher support, leadership support, collegial learning, new organizational structures, local and regional support). Thereafter, the data were read through a second time to search for additional text or sentences matching existing themes and categories or possible new ones. As a final step, each theme and category of change and transformation was compared and analysed according to the concept of levels of learning.

2.2 Object, change, and transformation in school

In this section, we present a description of each school based on stories told by school leaders, local and regional educational technologists, administrators, and teachers regarding previous and ongoing digitalization. Respondents described how they understand and conceptualise the object and process of digitalization, how they deal with digital and educational change, and how new educational practices and organizational infrastructures have occurred. Those descriptions have been supplemented by policy documents and project descriptions from the two schools.

3 School A

The first school that participated in the study is an upper secondary school located in a sparsely populated area in a middle-sized community in northern Sweden. At the time of the study, there were some 400 students and 70 teachers. For a school located in an area with long distances between home and school, the challenges have, according to the leadership and regional educational technologist, been of two kinds. On one hand, the school is obligated to provide students an equal education despite being in an area often characterized by lack of access to qualified teachers. This obligation has, on the other hand, fostered a commitment to representing new ways of teaching and learning that qualify as digital and educational change. According to the local and regional educational technologists, by adopting the concept of remote teaching, the school has invested in new teaching and learning designs, new learning platforms, development and distribution of digital learning materials, live-send lectures, and laptops or tablets for teachers and students, etc., which in turn has called for or resulted in large-scale digitalization processes at several organizational levels.

3.1 The object of digitalization

In this school, remote teaching represents the idea of educational and organizational change that seems to define the concept of digitalization in Learning III (i.e., change and transformation at an organizational level). In recent years, there have been several infusions of digital technology. All students, as part of a 1:1 initiative, have their own devices to be used in school and at home. Instead of being a developmental object for digitalization, school leaders and educational technologists at local and regional levels described the 1:1 initiative as a result of (or a tool for) ongoing digitalization historically driven by educational needs. This was described by the educational technologist:

Our digitization process actually emerged before the 1:1 initiative . . . . The need [for digital technologies] came about as we are a “bus school” [and] pick up high school students from neighbouring municipalities, which also means a lot of travel . . . . We started to think about how to solve this; for example, if students could have a study day and access learning material from home. We started to use a learning platform and have developed quite a considerable number of courses. Then we realized that when students are going to work via computers, we have to make sure they have them.

Another educational technologist stated, “It was the educational and work environmental needs that made us invest in 1:1, not because it would be trendy.. .. We ended up in a digital transformation without knowing. The school management made a decision, and we didn’t really know where [we would end up]” and that “there is a shared vision that this is something we prioritize. We have the school management to thank for this, they understand this requires time”.

From teachers’ perspectives, the digitalization was particularly described as a tool for enhanced control over tasks, course material, and communication with students; for example, fewer papers, administration, and better opportunities to teach and communicate: “I saw the benefits [of digital technologies] quite quickly; it was not about enhanced workload, but rather a relief in everyday life” and to “have everything organized, that was the initial argument”. They also made statements such as, “I don’t need to copy compendiums and other materials and our students will not lose things” and “It’s easier to help students. I can make comments directly on assignments and help students to re-organize texts”.

In sum, the examples reinforce the idea that digitalization is aimed at, and comes with, an endeavour of more than technical development of the school, as is otherwise characteristic for earlier levels of change and development, such as Learning IIa.

3.2 Processes of change and transformation

During the interviews, the respondents were asked to describe core aspects needed for reaching the object of digitalization in their school. At the school leadership level, the core of digitalization was related to change and transformation in teaching and learning. As students are geographically widely distributed, new pedagogical methods and ways of thinking about teaching and learning practices have been the central focus. As described by a respondent,

[It is important] not to get stuck on the first level, i.e., that we buy computers, and we exchange our books with digital learning materials, we exchange paper with screens, we exchange pencils with keys, and then we continue with our PowerPoint presentations and tests. Again, it has always been a conscious direction toward the goal [of integration] . . . Digitization is successful only when we have changed our way of teaching.

From a teacher perspective, changes in teaching and learning practices are mainly described as enhanced possibilities for individualized teaching, distribution of information, and become more involved in students learning, stating, “It’s easier to help students” and that, “Students can just ask us to read and I can do it directly in the computer. The teaching becomes so alive this way instead of hand[ing] in papers and wait[ing] two weeks for comments”. There were also statements that “Now I have my own digital material that can be reused” and “I don’t need to take unnecessary time from the lessons because of lost papers. However, as expressed by the teachers, these aspects require digital systems and organizational support.

The second theme of change and development is related to administrative aspects such as development of digital platforms and communication systems for teachers, students, administrators, and leadership. One educational technologist described the benefits of their digital system when it is time to “plan, book, and conduct meetings”. From an administrative perspective, the use has supported the concept that “the administration should be able to see where teachers are instead of running around searching for them”. From a teacher and student perspective, learning platforms are used to support students’ access to teaching, learning, communication, collaboration, and learning materials distributed at other premises based on contextual differences and leaning needs:

The goal was to have mirrored classrooms—that is, digital mirrored classrooms of what we did in real life, so that everyone would have a classroom on the learning platform and everything that happened, i.e., orally, in writing, submissions, materials. Yes, everything would be gathered there.

More complicated administrative change is according to the regional educational technologist related to study health:

Confidentiality is central to much of the student health staffs’ work, so they need other digital tools [than teachers]. That aside, the two major insights for the student health team have been the possibility to allow pupils to make councillor-, nurse- and psychologist appointments online, which means that pupils don’t have to be anxious about being seen by someone when they knock on the health team office doors. The other [insight], which we’ve gained through pilot testing, is the usefulness of mentometer systems in anonymous and easily feasible weekly evaluations of well-being and classroom study environments.

The third theme of change and transformation is related to organizational support at all school levels. As described by one educational technologist, there has been an ambition to not expect actors to harbour digital competence. This mind set has been an important tool for driving and supporting digitalization from various levels, including students:

Many times, the teachers get help and support but not the students . . . we do not assume that the students who come to us are already digitally competent. Surfing and playing games in your spare time are one thing . . . but using digital tools to achieve increased learning, greater commitment, and a better understanding of the subject are another thing. They didn’t get it for free just because they were born with a mobile in hand.

Accordingly, over the years, students have been offered digital course modules (including on security, integrity, knowledge and information search, development of critical thinking, and producing digital information) and digital support for schoolwork (to produce digital presentations, movies, etc.). Supporting the development of students’ digital competence is, according to teachers and educational technologists, a possibility for students to contribute to alternative ways of teaching, learning, communicating, and collaborating inside and outside the physical classroom.

For teachers and school leaders, digital and educational support have been required in various forms, deepening the learning needs expressed by the teacher group. There have been ongoing learning cafés, video instructions, and lessons held by educational technologists. Examples of more frequent support include new, extensive implementations and changes that require efforts outside teachers’ ordinary work. Using the implementation of the 1:1 initiative, learning platforms, and administrative systems as examples,

when we invested in new tablets for the students, it automatically meant that we also changed the system and changed the platform . . . it became a new digital learning environment for both teachers and students. Because of that, it was about to capsize. . . we realized that this process would stagnate and die. People will have such an inherent resistance to digitalization unless we invest time and resources in phasing this in nicely so that it becomes useful.

In sum, the examples represent educational change at various levels that moves beyond technical infusions and the first steps of learning. This was also indicated by one educational technologist’s description: “Now we are in this, how to say, more organizational and administrational process; [the] first one was mostly about pedagogical development”. It is also indicated that organizational support structures are focused on pedagogical and organizations development on the collective level, which seems related to Learning IIb, with the potential to develop Learning III.

4 School B

The second school that participated in the study is a medium-sized school located in a medium-sized community in Sweden. At the time of the study, it had approximately 500 students and 100 employees. Since 2011, all students have had their own digital devices to be used in school and at home. Prior to the 1:1 project, there had been small-scale infusion of technologies, including learning platforms and small-scale experiments with new digital learning designs.

4.1 The object of digitalization

In this school, digitalization was described by the school leader as initiated and driven by workplace environmental needs, expressed as follows:

There are a lot of people talking about digitization and IT development in terms of the ICT itself and the digitization part, but our input is the psychosocial work environment, and it is from this aspect that we drive the digitization development. . . .

As described, the paper burden, lack of communication between home and school, and endeavour to develop systems to administer teaching and learning were put forth as important objectives driving digitalization. Moreover, the vision is, according to the school leader, to become a paper-free school, meaning that tasks previously handled on paper—applications, notifications, reports, assignments, and schoolwork—should be done digitally and be available online. By pointing out this potential, digitalization is described as a tool to reduce administrative workload, which in turn enables time for teachers’ digital development in the classroom. This was described by the school leader, who stated, “Most people are driven, curious and competent. What they need are peace and quiet and to be protected from the administrative burden”, and that this “has been the driving force – reduce the paper burden and increase the digital use among colleagues and students”.

From teachers’ and local educational technologists’ perspectives, digitalization is described in similar terms as tool to “reduce the paper burden and enhance the digital competence among teachers and students”. Teachers feel that “mostly it is the need for reduced workload that many of us have suffered from. Not only for the staff but also for parents and for everyone else involved” and “It has been too much to do, so how can this be solved without hiring more staff?”

These descriptions reinforce the idea of change and transformation beyond technical infusions (Learning IIa) toward larger organizational change as part of Learning III in schools.

4.2 Processes of change and transformation

During the interviews, the respondents were asked to describe core aspects needed for reaching the object of digitalization in their school. At the school leadership level, the core of digitalization was, first, described to be budgetary and administrative reformulation, including changes in administrative work descriptions and the division of labour among teachers. Efficient and effective administrative systems and structures should in turn release time for teachers’ development in the classroom. New systems were also described by teachers to be central to new ways of communicating with students, parents, and—in the future—colleagues: “New digital systems also allow for increased exchange with parents. So, it may simplify communication between us teachers, but it will also simplify communication between teachers and the students and parents”. In the interviews, the 1:1 infusion was described as an important feature for developing new teaching and learning designs and new administrational solutions.

Second theme relates to teaching and learning. The time saved by reducing administrational and digital support functions, meetings, etc., has, according to school leaders and educational technologists, been allocated for teachers to undergo collegial learning and elaborate upon new educational learning designs. This was evident in the following quote, in which a teacher described how the school organization was re-organized to enable digital development:

First, we made changes in the school organization to release time and make space for change in the classroom. . . . Time for collective learning and collaboration [for development of digital learning practices] has been an important aspect that was made possible by the organizational change.

Moreover, the responsibility for change and development in teaching and learning practices was according to the school leader changed from top-down to bottom-up by means of new forms of collegial learning:

We have come to a culture where the problems do not belong to the school leader but to the group. . . . The idea is not that the school leader should decide to copy a paper to the students, but it should be taken care of on the floor where the competence exists. . . . We solve a lot through collegial collaboration where the knowledge is incredibly accessible.

To enable collective development of teaching and learning practices, the school leader and two of the teachers describe the importance of shared visions at all levels. This is further illustrated in the following quote: “There is a need for common sense, interest, and commitment throughout the organization—that is what drives the organization forward.. .. Basically, everyone has [a common focus] on the development of ICT.. .. There is a collective interest”.

Third theme relates to organisational support. For deep and sustainable change and development, teachers, educational technologists, and school leaders emphasize the importance of support. An educational technologist at the local school described weekly meetings for students to reflect upon digital solutions for their schoolwork, confirming that “it is not possible to have digitalized teaching if the students cannot use the digital products”. According to teachers, student support and engagement in digitalizing the classroom has meant changes in the division of labour between teachers and students: “Benefits are that the students are trained to take responsibility and the teaching can be, or it has become, much more adapted to individual needs”. On the teacher level, organizational support is arranged as collegial learning with time released to help and support each other.

At the regional level, the education technologist described their support for School B in terms of ICT inspirators selected from each school: “There are representatives from all organizations, preschool and K-12. We have a vision of sharing good examples that can be brought home [to] their schools. However, there is a problem called time”. The regional educational technologist meant that “support on [the] regional level is not enough. Schools decide how to further support digitalization” and that “there are considerable differences between schools in this region”. The solution in School B, according to both educational technologists, includes arrangements for collegial learning and support on various organizational levels bolstered by what is described as a “strong and interested leadership”. This was confirmed by the teachers, meaning, for example, that “engagement is essential. We have had support from the leaders”.

In sum, the examples given by School B reinforce the idea that digitalization is aimed at and requires change and development at all levels of an organization, with the objective of reducing the workload rather than digitalization per se. It was also indicated that professional development by means of collegial learning is related to Learning IIb (development of new ways of working), with the potential to develop Learning III (new ways of working in the overall organization).

5 Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore organizational transformation as part of digitalization in schools. More specifically, drawing on CHAT, the aim was to explore how the object of digitalization is conceptualized as well as how structural and educational change occur in schools known for large-scale digitalization.

5.1 Understanding the object of digitalization through levels of learning – A tool for discussing digitalization in school?

As discussed in research, digitalization processes are often limited to the implementation of digital technologies, without disruptions of teaching and learning practices or of organizational infrastructures for supporting digitalization (Glover et al. 2016; Håkansson Lindqvist 2015; Islam and Grönlund 2016; see also Cuban, 2013). Digital technologies tend to support previous practices rather than developing new ones (Islam and Grönlund 2016; Jenkins et al. 2011). Related to such issues, an interesting aspect of this study is how the object of digitalization and transformation is discussed and elaborated upon within each of the two schools. As argued by Kaptelinin and Nardi (2006), “the object of activity can be considered the “ultimate reason” behind various behaviors of individuals, groups, or organizations” (p. 138) “of understanding not only what people are doing, but also why they are doing it” (p. 138). The object of the activity can also be considered a “sense-maker” for why and how organizations prioritize, develop, and transform in a certain way. Related to such statements, it interesting how the object of digitalization is discussed and how this seem set the agenda for digital transformation within the two schools (in terms of new technologies without disruptions of teaching and learning practices (Learning IIa); new technologies with new educational practices (Learning IIb); or as digital, educational, and organizational school development (Learning III)). In these schools, respondents at all levels discuss and describe digitalization in terms of the organizational and educational needs required to “survive in rural areas” and “reduce the administrative workload” for staff, especially teachers. Instead of being the primary object, the technologies become a tool that enable schools to provide students with equal education, despite being in an area often characterized by lack of access to qualified teachers. This moves beyond technical infusions (compare Islam and Grönlund 2016)—and thereby beyond the first steps of learning and the use of technical tools without disruption in teaching and learning practices—and toward larger organizational change in school (se Bateson, 1972; de Lange, 2010).

The descriptions of how digitalization is elaborated upon as a potential object in these schools reinforce the idea that digitalization is aimed at, and comes with, an endeavor of more than technical development, as often characterized by the first steps of change and development. How digitalization is conceptualized—what is theoretically and practically meant by digitalization—also seems to influence how the schools organize support and professional development. As described by the respondents, digitalization focused on educational and organizational change makes support and professional development at multiple levels compelling, in a different way than before. Combined with investments in digital technologies, both schools enact student support and teachers’ professional development (TPD) activities focused on educational change at all levels (Learning IIb). In addition to technical skills, the support is focused on development of new teaching and learning designs, new ways of communicating within the organization, new ways of planning and organizing schooling in rural areas, and new ways of organizing administrative work (see Table 2 below) aimed at educational and organizational school development (Learning III). This also means that budgeting for digitalization must include more than technical infusion.

From this point of view, the object of digitalization seems to harbor an idea that defines, and guides change and digitalization processes. It points at the potential of shared meaning to guide priorities and plans and to enable development beyond access to new digital tools and towards change in classroom practices and organizational structures. However, this also points to digitalization and change being complex and diverse, with different stages, levels, and meanings.

5.2 Transformative processes and micro/macro dynamics

The analysis gave the impression of a multifaceted process with several learning steps at several organizational levels, as characterized by Learning IIb and III. As seen in this study, there are several examples of digital transformation work. Respondents at all levels in the schools seem point to a holistic view of digitalization, meaning that a commitment is needed between classroom and organization transformation—an interplay between micro- and macrodynamics.

As described by Zhang (2010), for deep and sustainable change to be enacted, change must appear at all levels. For this, digitalization requires a complex and comprehensive system thinking with close and dynamic interplay between macro and micro processes (Zhang 2010). However, for complex system thinking, Zhang (2010) suggests that schools support an interplay between different levels of the organization. Such an interplay also became evident in this study and in schools’ descriptions of rigorous support and interaction among students, teachers, parents, and school leaders as a means for digitalization and educational change at all levels. As shown in the analysis, efforts with educational change in the classroom interact for example with supportive macro-level properties. This becomes visible when schools work with close interaction between digital student support and teachers’ professional development, for example. This example illustrates how the development of students’ digital learning is expected to support digital development in school and the classroom, i.e., development from the micro- to macro-level and vice versa. Another example is strategic administrative changes on macro level with time saved for teachers’ development in classroom. In sum, this indicates how digitalization includes processes intertwined in a way that indicates a need for a holistic strategy and a macro–micro dynamic (cf. Hauge 2016). However, educational and administrative processes are understood as dependent on transparent and reliable paths for decision making, meaning that school leadership must be drivers or co-players throughout the process (compare, Håkansson-Lindqvist and Pettersson (2019).

6 Conclusions and implications for research and practice

This study adds to research and practice by conceptualizing digitalization as a process with different objects and stages that includes several organizational levels. This paper provides an empirical example of how CHAT and levels of learning (Bateson 1972; Engeström 1987) could be used to discuss digitalization and transformation in schools. Seeing digitalization from the theoretical perspective of CHAT and levels of learning reinforces the idea of a stepwise process from technology investments exemplified in previous research (LIa) to digitalization as a form of strategic educational and organizational development (LIII), and everything in between.

Since the object, according to CHAT, direct the planning, and organization of the activity (Engeström 1987; Kaptelinin and Nardi 2006), the object and learning steps could be used as a practical framework in school to stimulate explicit discussions and conceptual clarifications on what digitalization is, what it involves, and what it should or could involve or require in the specific school context. Thus, using the framework could be a potential of creating shared meaning to guide priorities and plans and to enable development beyond access to new digital tools. Such framework and discussions could also be useful at regional and municipality level for planning, prioritizing, budgeting, and decision making (what do we, as a municipality, mean by digitalization and what does it require in terms of resources and professional development). This could support schools and municipalities to create a shared path for digitalization and to guide effort, activities, budget and priorities.

To conclude, this paper provides an example of how digitalization could be conceptualized in school. However, it should be noticed that this study is based on schools known for their large-scale digitalization processes. Future research could focus on larger numbers of schools on different digitalization stages and with different objects. This could provide a more nuanced picture on how this framework could be used to understand digitalization processes in school.

References

Aesaert, K., van Braak, J., Van Nijlen, D., & Vanderlinde, R. (2015). Primary school pupils’ ICTcompetences: Extensive model and scale development. Computers & Education, 81, 326–334.

Agélii Genlott, A., & Grönlund, Å. (2016). Closing the gaps – Improving literacy and mathematics by ict-enhanced collaboration. Computers & Education, 99, 68–80.

Bateson, G. (1972). Steps of an ecology of mind. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Blau, I., & Shamir-Inbal, T. (2017). Digital competences and long-term ICT integration in school culture: The perspective of elementary school leaders. Education and Information Technologies, 22(3), 769–787.

Cole, M. (1996). Cultural phycology. A once and future discipline. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Cuban, L. (2013). Why so many structural changes in schools and so little reform in teaching practice? Journal of Educational Administration, 51(2), 109–125.

de Lange, T. (2010). Technology and pedagogy: Analysing digital practices in media education. Oslo: AIT Oslo AS.

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 14(1), 133–156.

Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Orienta-Konsultit: Helsinki.

Glover, I., Hepplestone, S., Parkin, H., Rodger, H., & Irwin, B. (2016). Pedagogy first: Realising technology enhanced learning by focusing on teaching practice. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(5), 993–1002.

Haelermans, C. (2017). Digital Tools in Education. In On Usage, Effects, and the Role of the Teacher. Stockholm: SNS Förlag https://www.sns.se/aktuellt/digital-tools-in-education-on-usage-effects-and-the-role-of-the-teacher.

Håkansson Lindqvist, M. (2015). Gaining and sustaining TEL in a 1:1 laptop initiative: Possibilities and challenges for teachers and students. Computers in the Schools, 32(1), 35–62.

Håkansson-Lindqvist, M., & Pettersson, F. (2019). Digitalization and school leadership: on the complexity of leading for digitalization in school. International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 36(3), 218–230.

Hansson, A. (2013). Arbete med skolutveckling-En potentiell gränszon mellan verksamheter? Ett verksamhetsteoretiskt perspektiv på en svensk skolas arbete över tid med att verksamhetsintegrera IT (Doctoral dissertation, Mittuniversitetet).

Hatlevik, O. E., & Christophersen, K.-A. (2013). Digital competence at the beginning of upper secondary school: Identifying factors explaining digital inclusion. Computers & Education, 63, 240–247.

Hauge, T. E. (2014). Up-take and use of technology: Bridging design for teaching and learning. Technology, Pedagogy & Education, 23(3), 311–323.

Hauge, T. E. (2016). On the life of ICT and school leadership in a large-scale reform movement. In E. Elstad (Ed.), Digital expectations and experiences in education (pp. 97-115). SensePublishers.

Holmgren, R., Haake, U., & Söderström, T. (2017). Firefighter learning at a distance: a longitudinal study. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 33(5), 500–512.

Islam, S., & Grönlund, Å. (2016). An international literature review of 1:1 computing in schools. Journal of Educational Change, 17(2), 191–222.

Jahnke, I., Bergström, P., Mårell-Olsson, E., Häll, L., & Swapna, K. (2017). Digital didactical designs as research framework – iPad integration in Nordic schools. Computers & Education, 113, 1–15.

Jedeskog, G. (2005) Ch@nging school. Implementation of ICT in Swedish School, Campaigns and Experiences 1984–2004. Uppsala University: Department of Education.

Jenkins, M., Browne, T., Walker, R., & Hewitt, R. (2011). The development of technology enhanced learning: Findings from a 2008 survey of UK higher education institutions. Interactive Learning Environments, 19(5), 447–465.

Kafyulilo, A., Fisser, P., & Voogt, J. (2016). Factors affecting teachers’continuation of technology use in teaching. Education and Information Technologies, 21(6), 1535–1554.

Kaptelinin, V., & Nardi, B. (2006). Acting with technology. Activity theory and interaction design. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Krumsvik, R. J., Jones, L. Ø., Øfstegaard, M., & Eikeland, O. J. (2016). Upper secondary school teachers’ digital competence: Analysed by demographic, personal and professional characteristics. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 11(3), 143–164.

Kvale, S. (2009). Interviews. An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. London: Sage Publications.

Leont’ev, A. N. (1978). Activity, Conciosness, and personality. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. Retrieved October 7, 2010, from http://www.marxists.org/archive/leontev/works/1978/index.htm. Accessed 10 Jan 2020.

Leont’ev, A. N. (1981). The problem of activity in psychology. In J. V. Wertsch (Ed.), The concept of activity in soviet psychology (pp. 37–71). New York: Sharpe.

Lund, A., & Hauge, T. E. (2011). Designs for teaching and learning in technology rich learning environments. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 4, 258–272.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A new framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054.

Olofsson, A. D., & Lindberg, O. (2014). Moving from theory into practice - on the informed design of educational technologies. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 23(3), 285–291.

Olofsson, A. D., Lindberg, J. O., Fransson, G., & Hauge, T. E. (2015). Uptake and Use use of Digital digital Technologies technologies in Primary primary and Secondary secondary Schools schools – a A Thematic thematic Review review of Researchresearch. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 6(4), 103–121.

Ottestad, G. (2008). Schools as digital competent organizations: Developing organisational traits to strengthen the implementation of digital founded pedagogy. International Journal of Technology, Knowledge and Society, 4(4), 10.

Petersen, A. (2014). Teachers’ perceptions of principals’ ICT leadership. Contemporary Educational Technology, 5(4), 302–315.

Pettersson, F. (2018a). On the issues of digital competence in educational contexts – a review of literature. Education and Information Technologies, 23(3), 1005–1021.

Pettersson, F. (2018b). Digitally Competent School Organizations – Developing Supportive Organizational Infrastructures. International Journal of Media, Technology & Lifelong Learning, 14(2), 132–143.

Vanderlinde, R., & van Braak, J. (2010). The e-capacity of primary schools: Development of a conceptual model and scale construction from a school improvement perspective. Computers & Education, 55, 541–553.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Zhang, J. (2010). Technology-supported learning innovation in cultural contexts. Educational Technology Research & Development, 58(2), 229–243.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Umea University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pettersson, F. Understanding digitalization and educational change in school by means of activity theory and the levels of learning concept. Educ Inf Technol 26, 187–204 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10239-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10239-8