Abstract

Background

Early onset colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence is rising under age 50, with a birth cohort effect for increasing incidence among individuals born 1950 and later. It is unclear whether increasing incidence trends will confer increased risk beyond age 50, the previously most commonly recommended age to initiate screening, when screening availability might modify incidence trends.

Aim

Evaluate US trends in colorectal cancer (CRC) for ages 40–59 years.

Methods

We analyzed counts and incidence rates for CRC, including by anatomic subsite, using the US Cancer Statistics dataset covering 100% of the population 2003–2017. Joinpoint regression was used to quantify Average Annual Percent Change (AAPC) in cancer incidence by age subgroup.

Results

470,458 CRC cases were observed age 40–59, with absolute numbers of rectal (n = 4173) and distal cases (n = 3327) per year for age 50–54 approaching age 55–59 cases for rectal (n = 4566) and distal (n = 3682) cancer by 2017. Increasing early onset rectal cancer incidence per 100,000 occuring under age 50 was observed to extend to age 50–54, from 4.9 to 6.3 for age 40–44 (AAPC 2.1; 95% CI 1.5–2.7), 9.3 to 12.0 for age 45–49 (AAPC 1.5; 95% CI 1.1–1.4), and from 16.7 to 19.5 for age 50–54 (AAPC 1.0; 95% CI 0.7–1.3).

Conclusions

CRC trends suggest observed increased risks under age 50 are also present after age 50, despite prior availability of screening for this group. Recent CRC trends support initiation of screening earlier than age 50, and promotion of “on-time” screening initiation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence rates among adults younger than 50 years are increasing, and have been attributed to a birth cohort effect after 1950 [1]. Since 2011, CRC incidence rates have also been increasing by 1% per year among ages 50–64 years [2]. These observations have led to recommendations to lower the screening initiation age to 45 years from the previously recommended 50 years, and to concerns regarding how to promote “on-time” screening at guideline-recommended ages to initiate screening [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Differences by anatomic subsite have implications for understanding risk factors and informing cancer prevention and control strategies [1, 9]. Anatomic distribution of increases among adults aged < 50 years and changes in absolute numbers of cases have not been reported in detail by 5-year age group. To address these evidence gaps, we examined recent CRC incidence trends, stratified by anatomic subsite, among individuals age 40–59. The age range examined was just before and after age 50 years—the historically most commonly recommended initiation age for CRC screening [5,6,7].

Methods

We analyzed CRC incidence data from United States Cancer Statistics (USCS), which provides 100% coverage of cancer incidence for all 50 states and the District of Columbia, utilizing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries and the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program [10]. Cancer subsites were defined as proximal (C18.0, C18.2–C18.5), distal (C18.6–C18.7), and rectal (C19.9, C20.9), and limited to primary colorectal adenocarcinomas [11]. Incidence rates were calculated using SEER*Stat v8.3.5, with rates expressed per 100,000 persons and age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population. The Joinpoint Regression Program (v4.8.0.1) was used to quantify Average Annual Percent Change (AAPC). AAPCs different from zero at p < 0.05 were considered to have a statistically significant “increase” or “decrease,” and otherwise were considered “stable.”

Results

From 2003 to 2017, 470,458 cases of CRC were recorded among ages 40–59 years (Table 1). For all ages combined, rates were stable, with overall CRC incidence per 100,000 observed to be 35.4 in 2003 and 34.8 in 2017 (AAPC − 0.1; 95% CI: − 0.4–0.3). By age, overall CRC incidence per 100,000 increased between 2003 and 2017 from 13.4 to 15.8 for ages 40–44 years (AAPC 1.3; 95% CI 1.0–1.6) and from 24.8 to 29.1 for ages 45–49 years (AAPC 1.1; 95% CI 0.8–1.4). CRC incidence between 2003 and 2017 was stable for ages 50–54 years (AAPC 0.3; 95% CI: 0.0–0.7) and decreased from 72.7 to 56.7 for ages 55–59 years (AAPC − 1.8; 95% CI − 2.2–− 1.3).

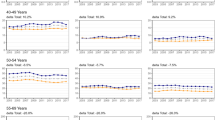

Absolute number of rectal cancer cases per year increased from 1123 to 1239 for ages 40–44 years, 2011 to 2506 for ages 45–49 years, 3189 to 4173 for ages 50–54 years, and 3901 to 4566 for ages 55–59 years between 2003 and 2017 (Fig. 1). Rectal cancer incidence per 100,000 was stable for all ages combined between 2003 and 2017 (AAPC 0.5; 95% CI: − 0.2–1.3), but increased from 4.9 to 6.3 for ages 40–44 years (AAPC 2.1; 95% CI 1.5–2.7), 9.3 to 12.0 for ages 45–49 years (AAPC 1.5; 95% CI 1.1–1.4), and 16.7 to 19.5 for ages 50–54 years (AAPC 1.0; 95% CI 0.7–1.3). Incidence per 100,000 decreased from 24.7 to 20.8 for ages 55–59 years (AAPC − 1.2; 95% CI − 2.2– − 0.1; Fig. 2 and Table 1).

Absolute number of distal colon cancer cases per year increased from 936 to 1039 for age 40–44, 1646 to 1938 for ages 45–49 years, 2900 to 3327 for ages 50–54 years, and 3336 to 3682 for ages 55–59 years between 2003 and 2017 (Fig. 1). From 2003 to 2017, distal colon cancer incidence per 100,000 was stable for all ages combined between 2003 and 2017 (AAPC 0.2; 95% CI: − 0.7–1.1), but increased from 4.1 to 5.3 for ages 40–44 years (AAPC 2.0; 95% CI 1.5–2.4), and from 7.6 to 9.3 for ages 45–49 years (AAPC 1.5; 95% CI 1.1–1.8). Distal colon cancer incidence per 100,000 between 2003 and 2017 was stable for ages 50–54 years (15.2 in 2003 vs 15.6 in 2017, AAPC 0.4, 95% CI − 0.2–1.1) and decreased from 21.1 to 16.8 for ages 55–59 years (AAPC − 1.7; 95% CI − 2.6– − 0.7; Fig. 2 and Table 1).

Absolute number of proximal colon cancer cases per year between 2003 and 2017 decreased from 1010 to 821 for ages 40–44 years, 1726 to 1643 for ages 45–49 years, 3015 to 3012 for ages 50–54 years, and 4254 to 4209 for ages 55–59 years (Fig. 1). From 2003 to 2017, proximal cancer incidence per 100,000 decreased for all ages combined (AAPC − 1.2; 95% CI: − 2.1– − 0.3), but was stable for ages 40–44 years (4.4 vs 4.2 in 2017; AAPC − 0.1; 95% CI − 0.6–0.4) and for ages 45–49 years (7.9 vs 7.9 in 2017; AAPC 0.0; 95% CI − 0.3–0.4; Fig. 2). Incidence of proximal cancer per 100,000 decreased from 15.8 to 14.1 for ages 50–54 years (AAPC − 0.6; 95% CI − 1.0– − 0.3) and from 26.9 to 19.2 for ages 55–59 years (AAPC − 2.3; 95% CI − 2.8– − 1.8) between 2003 and 2017.

Discussion

Utilizing a national sample of over 470,000 CRC cases observed between 2003 and 2017 within the US Cancer Statistics dataset, we found that increased risk trends for CRC under age 50 are also present after age 50. Specifically, we observed that rectal cancer incidence rates increased for ages 40–54 between 2003 and 2017. By 2017, counts and rates of rectal and distal cancers for ages 50–54 approached those reported for ages 55–59. We postulate that these trends are a consequence of increasing rates of rectal and distal cancer for ages 50–54 years along with decreasing rates of distal cancer among ages 55–59 years. Our data suggest that the observed increased risk for CRC under age 50 for birth cohorts born after 1950 is also present after age 50, despite the prior availability of screening for this group. As such, availability of screening for persons age 50 and beyond does not appear to “reset” the birth cohort effect for increased CRC risk observed under age 50. Rectal cancers often require multiple modalities for treatment, including radiation, chemotherapy, and surgery, and survivors often experience significant post-treatment morbidity [12]. The observed increase in absolute number of distal and rectal cancers, and in the incidence rate of rectal cancers age 50–54, highlights importance of screening uptake to reduce morbidity and mortality. CRCs, particularly rectal cancers, are detectable and preventable with currently available screening modalities such as the fecal immunochemical test and colonoscopy. However, in 2018, the proportion up-to-date with screening ranged from 61 to 63% for adults ages 50–64 years compared to 71–79% for adults ages ≥ 65 years [2, 13]. Furthermore, the proportion of individuals ages 50–54 years who were up-to-date with screening was just 48–50% [2, 12].

Our sample was large enough to allow for anatomic subsite-specific analysis of CRC trends, which enables observation of the drivers of increasing trends in CRC. We found changes in distal and rectal cancer incidence for individuals ages 40–44 and 45–49 years, and changes in rectal cancer incidence for individuals ages 50–54 years. We observed decreasing proximal cancer incidence for ages 50–54 and 55–59 years, and stable proximal incidence for ages 40–44 and 45–49 years. Data reported by Siegel et al., which has significant overlap with the US Cancer Statistics dataset data we used, have shown trends toward increasing CRC incidence from birth to age 49 for proximal, distal, and rectal cancer for time periods 2016 and earlier [2]. For the age group 50 to 64 years of age, Siegel et al. reported increasing incidence trends for cancers of the distal colon and rectum from 2012 to 2016, but not the proximal colon [2]. Our data confirm and extend Siegel et al.’s report by providing finer detail on incidence trends among age groups just before and after age 50. Additionally, our data emphasize that the increasing trend for the 50–64-year-old group reported by Siegel is currently driven by individuals age 50–54, underscoring the importance of promoting early initiation of screening at age 45, and the need to increase screening uptake for 50–54-year-olds in order to address current trends, and possibly head off future, even larger increases in age-specific incidence as birth cohorts from 1950 and younger age and grow older. Further, as the embryologic origins, molecular tumor characteristics, and associated microbial milieu may differ by anatomic site, our observation of differences in trend by site highlights the importance of considering site in studies examining risk factors for early-onset CRC, as well as for CRC early in middle age just before and after age 50 [9, 14,15,16,17].

A strength of this study is the use of USCS, which provides a national assessment of case counts between 2003 and 2017. A limitation of our analysis is that we do not have data on whether increases in CRC incidence, particularly for those age 50 and older, were occurring among people exposed versus unexposed to colorectal cancer screening tests, and cannot therefore determine whether the increased risks observed were among people who were unscreened.

Taken together, increasing CRC incidence for both ages 45–49 and 50–54 years and the low prevalence of “on-time” screening at age 50 years underscore the importance of implementing interventions to increase screening for individuals age 50–54 years. A variety of interventions may be useful in increasing screening uptake in this patient population, including offering choice of tests, and organized mailed outreach invitations to complete screening [18]. Increasing CRC incidence among adults aged 45–49 and 50–54 years also supports recent American Cancer Society [4], American College of Gastroenterology [8], and United States Preventive Services Task Force [19] recommendations to initiate average risk screening at age 45, instead of age 50 [6, 7].

References

Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, Miller KD, Ma J, Rosenberg PS, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974–2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109:djw322.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Fedewa SA, Butterly LF, Anderson JC, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:145–164.

Liang PS, Allison J, Ladabaum U, Martinez ME, Murphy CC, Schoen RE et al. Potential intended and unintended consequences of recommending initiation of colorectal cancer screening at age 45 years. Gastroenterology 2018;155:950–954.

Wolf AMD, Fontham ETH, Church TR, Flowers CR, Guerra CE, LaMonte SJ et al. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:250–281.

Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Kaltenbach T et al. Colorectal cancer screening: recommendations for physicians and patients from the U.S. multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2017;153:307–323.

Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Davidson KW, Epling JW Jr, García FAR et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 2016;315:2564–2575.

Provenzale D, Gupta S, Ahnen DJ, Markowitz AJ, Chung DC, Mayer RJ et al. NCCN guidelines insights: colorectal cancer screening, Version 1.2018. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw JNCCN 2018;16:939–949.

Shaukat A, Kahi CJ, Burke CA, Rabeneck L, Sauer BG, Rex DK. ACG clinical guidelines: colorectal cancer screening 2021. Am J Gastroenterol 2021;116:458–479.

Demb J, Earles A, Martínez ME, Bustamante R, Bryant AK, Murphy JD et al. Risk factors for colorectal cancer significantly vary by anatomic site. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2019;6:e000313.

National Program of Cancer Registries and Surveillance E, and End Results SEER*Stat Database: U.S. Cancer Statistics Incidence Analytic file -1998–2017. United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Released June 2020, based on the 2019 submission.

Howlader N NA, Krapcho M, et al., eds. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2014. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2017. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014.

Tamas K, Walenkamp AM, de Vries EG, van Vugt MA, Beets-Tan RG, van Etten B et al. Rectal and colon cancer: not just a different anatomic site. Cancer Treat Rev 2015;41:671–679.

Joseph DA, King JB, Dowling NF, Thomas CC, Richardson LC. Vital signs: colorectal cancer screening test use—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:253–259.

Carethers JM. One colon lumen but two organs. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:411–412.

Bufill JA. Colorectal cancer: evidence for distinct genetic categories based on proximal or distal tumor location. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:779–788.

Irrazábal T, Belcheva A, Girardin S, Martin A, Philpott D. The multifaceted role of the intestinal microbiota in colon cancer. Mol Cell. 2014;54:309–320.

Burnett-Hartman AN, Lee JK, Demb J, Gupta S. An update on the epidemiology, molecular characterization, diagnosis, and screening strategies for early-onsetcolorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1041–1049.

Dougherty MK, Brenner AT, Crockett SD, Gupta S, Wheeler SB, Coker-Schwimmer M et al. Evaluation of interventions intended to increase colorectal cancer screening rates in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Inter Med 2018;178:1645–1658.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Draft Recommendation Statement: Colorectal Cancer: Screening. Accessed Nov 17, 2020 at https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/colorectal-cancer-screening3#citation20.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ms. Hanin Yassin for assistance with manuscript preparation and submission.

Funding

This work was supported in part by Award Numbers R37CA222866 and F32CA239360 from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Drs. Cho and Siegel contributed equally to this research, and share co-first authorship.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cho, M.Y., Siegel, D.A., Demb, J. et al. Increasing Colorectal Cancer Incidence Before and After Age 50: Implications for Screening Initiation and Promotion of “On-Time” Screening. Dig Dis Sci 67, 4086–4091 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-021-07213-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-021-07213-w