Abstract

Proper absorption of vitamin B12 requires gastric corpus mucosa that functions appropriately and secretes intrinsic factor needed as an essential cofactor for the absorption of dietary vitamin B12 in the small bowel. Here we describe the prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency and atrophic corpus gastritis (ACG) in patients with coronary heart disease. Fasting serum was obtained from patients who were admitted for cardiovascular diseases at the Coronary Care Unit in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. The status of gastric mucosa was assessed by using the serum levels of pepsinogens I and II, gastrin-17, and Helicobacter pylori IgG antibodies and analyzed over vitamin B12 level subgroups. The study population consisted of 376 patients (mean age, 65 years [SD, 13 years], 227 [60%] males). Low vitamin B12 levels (<150 pM) were detected in 28 patients (7%). Of these 28 patients, 5 (18%) had ACG according to the biomarker assays. Altogether, another 140 patients (37%) had vitamin B12 levels between 150 and 250 pM, of whom 10 (7%) had ACG. Of the remaining patients, five (2%) had ACG. Deficiency of vitamin B12 is common among subjects with coronary heart disease. Up to 20% of these deficiencies are related to ACG.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Vitamin B12 deficiency is prevalent among the elderly [1–4]. Vitamin B12 is involved in the development of pernicious anemia, neurological disorders, and hyperhomocysteinaemia. Homocysteinemia is a factor considered to play a role also in the coronary heart disease. Many studies have been undertaken to examine the causality between homocysteine and cardiovascular disorders. The general outcome supports the hypothesis that an elevated homocysteine plasma concentration leads to an increased risk of ischemic heart disease and to increased mortality [5]. In this context, the role of vitamin B12 remains unclear [6, 7].

Absorption of vitamin B12 is a complex process, in which the stomach plays an important role. Pepsin and gastric acid, both secreted in the stomach, liberate B12 bound to proteins in the diet, and gastric parietal cells release intrinsic factor needed for proper absorption of the liberated B12 in the small bowel. Only after binding to intrinsic factor (IF) are the IF-B12 complexes absorbed in the terminal ileum. Because of the complexity of the absorption process, a vitamin B12 deficiency can develop due to several causes, where low dietary intake, low production of intrinsic factor, and gastric and ileum pathology are the most common reasons [1, 7]. Consequently, gastric dysfunction, due to either gastritis or atrophic corpus gastritis, can cause low secretion of IF, malabsorption, and, finally, vitamin B12 deficiency. Particularly in elderly age groups, atrophic gastritis is a quite common disease that does not often receive much attention and remains frequently undiagnosed. The proper diagnosis requires endoscopy and gastric biopsies, which are, furthermore, often misinterpreted and overlooked.

Serum biomarkers offer a tool for assessing the status of gastric mucosa by simple blood tests. Recently a new test is developed and described in the literature for such purposes [8–12]. On the basis of serum levels of serum pepsinogen I and gastrin-17 as well as Helicobacter pylori antibodies assayed from a blood sample, it is possible to establish with high accuracy whether the patient has gastritis, whether the gastritis is atrophic or not and which part of the stomach the atrophic changes are located. Derived from the literature, the sensitivity and specificity of the blood test panel for patients with atrophic gastritis in general (atrophic gastritis [or resection] of any topographical type versus nonatrophic Helicobacter pylori gastritis or normal stomach) were 89% (95% CI: 81%–97%) and 93% (95% CI: 86%–100%), respectively [10].

The purpose of this study was to assess the prevalence of deficiency of vitamin B12 in patients with coronary heart disease and how often this deficiency may associate with atrophic corpus gastritis. For studying the status of the gastric mucosa reliably and safely, assay of the biomarkers for atrophic gastritis (GastroPanel, Biohit Plc, Helsinki) was used.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

Patients were recruited between April 2002 and May 2003 at the Coronary Care Unit of the Heart Centre of the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. The patients for this survey were collected without any selection from the hospitalized population in a cardiovascular unit of a university hospital in the Netherlands. Information on demographics, diagnosis, and history of coronary heart disease was collected. Fasting blood samples were taken from consecutive patients after an overnight stay and were processed immediately.

Gastric status

Blood was drawn into a plastic serum tube without additives and was centrifuged (after 60 min) for 10–15 min at 2000 g. Serum samples were stored frozen at −20°C until further use. The GastroPanel assays of gastrin-17, Helicobacter pylori IgG antibodies, and pepsinogens I and II (Biohit Plc, Helsinki, Finland) were performed in the laboratory of the manufacturer from the serum samples. Samples were run at the same time to minimize assay variability.

The serum gastrin-17 assay is based on a sandwich enzyme immunoassay (ELISA) utilizing horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated to a biotin/avidin amplification system. A sandwich ELISa utilizing pepsinogen I specific capture antibody and a horseradish peroxidase detection antibody was used to assess the pepsinogen I serum levels. Similarly, a sandwich ELISA utilizng pepsinogen II specific capture antibody and a HRP detection antibody was used to assess pepsinogen II serum levels. The Helicobacter pylori IgG antibody test is a qualitative test also based on an enzyme immunoassay (ELISA) utilizing an HRP-conjugated detection antibody.

All ELISA techniques were based on measuring the absorbance after a peroxidase reaction at 450 nm. Between reaction steps the plates were washed using a BW50 Microplate Strip Washer (Biohit Plc). The absorbencies were measured using a BP800 Microplate Reader (Biohit Plc). For determination of pepsinogen I and II and gastrin-17 values, second-order polynomial fit on standard concentrations was used to interpolate/extrapolate unknown sample concentrations (automatically, with the help of BP800 built-in software (Biohit). H. pylori IgG antibodies are expressed as enzyme immunounits (EIU) according to the formula included in the test kit:

EIU levels above normal (30 EIU) were considered Helicobacter pylori positive.

All laboratory data of the GastroPanel tests were entered into the Gastrosoft software system (Biohit Plc), where the status of the stomach was calculated from the serum values and expressed as normal, atrophy predominantly corpus, atrophy predominantly antrum, and gastritis.

Vitamin B12

The Immulite analyzer (DPC, Los Angeles, CA, USA) was used for the quantitative measurement of vitamin B12 serum levels. Vitamin B12 levels were subdivided into three groups according to the laboratory standards: levels below 150 pM were considered low, levels between 150 and 250 pM as lower than normal, and levels above 250 pM as normal.

Statistics

Frequency tables were provided for all baseline demographics, vitamin B12 levels, and gastric status. Regression analysis was used to study associations between vitamin B12 and the diagnoses derived from the GastroPanel results using GastroSoft software. Moreover, Spearman correlation between Helicobacter pylori titer and vitamin B12 levels was analyzed. All analyses were undertaken using SAS statistical software, version 8.2.

Results

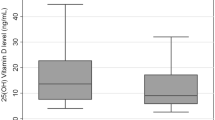

The study population comprised 376 patients with a mean age of 65 (SD 13) years. A total of 227 (60%) patients were males (Table 1). Serum levels indicating clinically significant, severe deficiency of vitamin B12 (<150 pM) were found in 28 patients (7%), and levels between 150 and 250 pM, indicating low vitamin levels, were found in 140 patients (37%). In the remaining 208 patients (55%) normal levels of vitamin B12 were found.

The associations of deficient and low levels of vitamin B12 with gastritis and atrophic corpus gastritis are presented in Table 2. It appears that 5 of 28 patients with severe vitamin B12 deficiency (18%) had atrophic corpus gastritis (ACG) according to the biomarker assays (GastroPanel). In addition, 5 of 20 patients (25%) with ACG had a severe vitamin B12 deficiency, compared to 23 of 356 patients without ACG (6%; P < 0.001). There were no differences in serum levels of B12 vitamin between patients with nonatrophic gastritis and normal, healthy stomach (Table 2). The individual level of significance between the 7% and the 2% frequency of ACG in the vitamin B12 low-normal and normal patients was statistically proven (P=0.03).

All patients with nonatrophic gastritis had H. pylori antibodies. Of the 20 patients with ACG, altogether 14 (70%) had antibodies. Of the five patients with ACG and deficiency of vitamin B12 (<150 pM), three (60%) had antibodies. The association between H. pylori seropositivity and vitamin B12 serum levels was not statistically significant (P=0.28).

Discussion

Two conclusions can be drawn from the results of the present study. First, undiagnosed clinically significant, severe deficiency of vitamin B12 (serum level <150 pM) is surprisingly prevalent in hospitalized elderly cardiovascular patients in The Netherlands but this prevalence corresponds with present literature data that a clinically significant deficiency of vitamin B12 occurs in 5%–20% of people aged 60 or over in Western populations in general [1–3]. However, in our study population, with a mean age of 65 years, we found that nearly half of the patients (45%) were vitamin deficient or had serum levels of vitamin B12 at least lower than 250 pM.

Second, low vitamin B12 levels seem to be related to ACG in a small but a noteworthy subgroup of patients. The present observations suggest that approximately one-fifth of the cardiovascular patients with severe vitamin B12 deficiency in The Netherlands have ACG as a background factor. However, the majority of patients do not seem to have malabsorption of vitamin B12 due to ACG, and they probably have a poor diet and low vitamin intake as likely causes of the deficiency.

This study has some limitations. The serum values for gastrin and pepsinogen are a model for gastric histology. Although the validation process is well described [8–12], histology is still the golden standard. Moreover, we can only compare the vitamin B12 deficiency rates with the literature, because the relation between gastric status and vitamin B12 deficiency was not studied in a control group. Information about patients’ medication was not assessed. Acid suppressive medication, e.g., proton pump inhibitors, are causal factors in the development of atrophy. It would be interesting to study the effect of these drugs on vitamin B12 levels.

The present study is an observational one and was designed only to elucidate the commonness of vitamin B12 deficiency in coronary heart patients. It does not say anything about whether the low vitamin B12 levels in cardiovascular patients influence the disease itself, or its outcomes, or whether the low vitamin levels are only reflections of vitamin deficiencies in elderly people in general. The causal associations may be, however, because of the surprising commonness of the low (<150 pM) and low-normal (150–250 pM) serum vitamin B12 levels among the present patients. It would be of interest to know whether correction of the low vitamin levels would improve the prognosis of the patients. Anyhow, the supplementation of the vitamin deficiency hardly has any drawbacks or negative influences.

The above conclusions suggest that it may be important to clear up the etiopathogenic causes (i.e., dietary versus malabsorption) if a vitamin deficiency is found or suspected. Even though a poor diet is is obviously the most prevalent cause of vitamin deficiency, deficiencies due to ACG and vitamin malabsorption seem to be so common as well that they must be taken into account in clinical and therapeutic considerations. In cases with ACG and malabsorption, vitamin supplementation will succeed most effectively with intramuscular injections only, whereas in other patients treatment of the deficiency may be possible by simple correction of the diet.

It would also be interesting to correlate vitamin B12 blood levels with those of homocysteine and folic acid and, also, with cardiovascular risk factors to ascertain whether the found vitamin B12 deficiency could further worsen the underlying coronary heart disease. This can be investigated in future research. The design of this study did not allow examination of this question, because we did not assess the cardiovascular diagnosis and risk profile.

In conclusion, our study shows that a surprisingly high number of patients with cardiovascular disease have low levels of vitamin B12, which may often remain undiagnosed and may, subsequently, remain uncorrected in proper way. ACG is a cause of the deficiency in a relatively small but remarkable subgroup of patients with low vitamin B12.

References

Nilsson-Ehle H, Landahl S, Lindstedt G, et al. (1989) Low serum cobolamin levels in a population of 70- and 75-year-old subjects. Gastrointestinal causes and hematological effects. Dig Dis Sci 34:716–723

Nilsson-Ehle H, Jagenburg R, Landahl S, et al. (1991) Serum cobolamins in the elderly: a longitudinal study of a representative population sample from age 70 to 81. Eur J Haematol 47:10–16

Yao Y, Yao SL, Yao SS, et al. (1992) Prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency among geriatric outpatients. J Fam Pract 35:524–528

Van Asselt DZB, de Groot LCPGM, van Staveren WA, et al. (1998) Role of cobalamin intake and atrophic gastritis in mild cobalamin deficiency in older Dutch subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 68:328–334

Wald DS, Law M, Morris JK (2002) Homocysteine and cardiovascular disease: evidence on causality from a meta-analysis. BMJ 325:1202–1206

Carmel R, Graan R, Jacobsen DW, et al. (1999) Serum cobalamin, homocysteine, and methylmalonic acid concentrations in a multiethnic elderly population: ethnic and sex differences in cobalamin and metabolite abnormalities. Am J Clin Nutr 70:904–910

Sipponen P, Laxén F, Huotari K, et al. (2003) Prevalence of low vitamin B12 and high homocysteine in serum in an elderly male population: association with atrophic gastritis and Helicobacter pylori infection. Scand J Gastroenterol 38:1209–1216

Kekki M, Samloff IM, Varis K, Ihamäki T (1991) Serum pepsinogen I and serum gastrin in the screening of severe atrophic corpus gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol 186:109–116

Oksanen A, Sipponen P, Miettinen A, et al. (2000) Evaluation of bleed tests to predict normal gastric mucosa. Scand J Gastroenterol 35:791–795

Sipponen P, Härkönen M, Alanko A, Suovaniemi O (2002) Diagnosis of atrophic gastritis from a serum sample. Clin Lab 48:505–515

Sipponen P, Maki T, Helske T, et al. (2002) Assays of H. pylori antibodies and serum levels of gastrin-17 and pepsinogen I in non-endoscopic diagnosis of atrophic gastritis antrum and corpus mucosa. Scand J Gastroenterol 37:785–791

Väänänen H, Vauhkonen M, Helske T, et al.(2003) Non-endoscopic diagnosis of atrophic gastritis with a blood test. Correlation between gastric histology and serum levels of gastrin-17 and pepsinogen I: a multicentre study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 15:885–891

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Professor Pentti Sipponen is scientific advisor for Biohit Plc, the company that developed the H. pylori, serum pepsinogen, and gastrin-17 assays.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Oijen, M.G.H., Sipponen, P., Laheij, R.J.F. et al. Gastric Status and Vitamin B12 Levels in Cardiovascular Patients. Dig Dis Sci 52, 2186–2189 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-006-9260-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-006-9260-8