Abstract

Secondary traumatic stress (STS), the emotional duress that results when an individual hears about the firsthand trauma experiences of another, is a significant concern for many social workers, particularly those in high-stress and trauma-exposed environments such as emergency rooms or psychiatric hospitals. Newly graduated social workers are especially susceptible to STS due to their limited experience and exposure to the emotional distress of clients. Yet, limited studies have focused on newly graduated social workers and STS. This study is twofold: (1) it attempts to provide insight into the experiences of pediatric emergency room social workers (PERSW) with STS, and (2) to explicate the utility of the findings in practical strategies to assist newly graduated and current social workers entering high-stressful work environments. A thematic analysis and semi-structured interviews were used with twenty-three pediatric emergency room social workers with at least one year of experience. The analysis revealed three themes: (1) the trauma of the job, (2) the effects of STS, and (3) coping strategies for STS. The findings underscore the need for a specialized toolkit for new graduates in pediatric emergency social work, offering resources and strategies tailored to the unique challenges of this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

The emphasis on empathy within the social work profession places clinicians at risk of experiencing secondary traumatic stress (STS). The term STS describes the emotional and behavioral reactions that arise when providing support to traumatized individuals (Figley, 1995). This phenomenon is distinct yet related to other psychological strains, such as moral distress and burnout. As defined by Ohnishi et al. (2019), moral distress arises from institutional constraints that impede ethical action in healthcare professionals, while burnout, characterized by emotional exhaustion and cynicism, results from chronic workplace stress (Lindblom et al., 2006). Though stemming from different sources, STS is particularly concerning in social work due to its direct connection to clients’ trauma experiences. The significance of self-care in social work education, as noted by Howard (2008) and Shepherd and Newell (2020), aims to mitigate the effects of STS. However, the realities of heavy caseloads, high-stress environments, and deep commitment to clients can lead to social workers neglecting their self-care, thereby increasing the risk of STS symptoms such as trauma re-experiencing, avoidance, and persistent arousal (Figley, 1995). This risk is exacerbated for social workers with traumatic histories (Gil & Weinberg, 2015), who may face complex transference and countertransference dynamics, potentially affecting their professional judgment and impeding the therapeutic process.

Newly graduated social workers, defined here as individuals who have completed their master’s in social work within the last one to two years, are particularly susceptible to STS. The transition from academic training to handling trauma cases in professional practice presents significant challenges. Without adequate coping skills, managing the complexities of trauma work can be overwhelming, potentially leading to reduced job satisfaction and hindered performance (Miller et al., 2019). Despite the focus on self-care in social work education, there remains a gap in adequately preparing new graduates for the real impact of trauma work and its profound effects on both clients and their well-being (Carello & Butler, 2014). This study serves a dual purpose: firstly, to explore the experiences of pediatric emergency room social workers in dealing with STS, and secondly, to derive and offer practical strategies based on these findings. These strategies are intended to support both new and existing social workers in effectively managing the challenges inherent in high-stress, trauma-informed environments.

Pediatric Social Workers and STS

Emotional turmoil transfer from clients to social workers, often under-recognized, is a critical area of concern in social work (Figley, 1995). Social workers working in high-stress, trauma-intensive environments such as emergency rooms, inpatient psychiatric settings, and other high-acuity medical contexts are particularly vulnerable (Renkiewicz & Hubble, 2022; Robins et al., 2009). The risk of STS and burnout in these settings is heightened due to the intense demands of the job (Sprang et al., 2011; Wagaman et al., 2015). STS has been found to affect over 50% of social workers, extending beyond typical work-related stress (Choi, 2011). The impact of STS is not limited to the professionals themselves; it also extends to the clients they serve (Michalopoulos & Aparicio, 2012). It can harm cognitive and occupational functioning, leading to a decline in the quality of care provided (Beck, 2011; Bride, 2007). The wider implications of STS on the social work profession are profound, as it can hinder the professional’s ability to provide effective mental health care and other necessary psychosocial interventions to clients in need (Lee et al., 2018; Owens-King, 2019).

Recognizing and addressing the impact of STS is crucial for social workers’ well-being and the quality of care they provide. This involves creating robust support systems, training in emotional resilience, and effective coping strategies to mitigate the risks of STS (Lounsbury, 2006; Manning-Jones et al., 2016). Such measures are essential for the health and well-being of the social workers themselves and for upholding the standard and quality of care within the social work profession. The recognition of STS in the literature provides some salient symptoms (Kelly, 2020). STS manifests in symptoms similar to those of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), occurring in individuals who, although not directly traumatized, are exposed to trauma through their work with traumatized persons (Figley, 1995). These symptoms can include intrusive thoughts, avoidance behaviors, negative alterations in mood and cognition, and changes in arousal and reactivity (American Psychiatric Association & Association, 2013).

Notably, social workers need to be equipped with the necessary resources and support to manage the negative effects of STS. Effective management of STS symptoms can lead to better clinical outcomes, including increased compassion satisfaction and reduced burnout (Butler et al., 2017). Effective coping with STS involves recognizing the signs and symptoms, understanding when and how to access support, acknowledging potential long-term effects, and sustaining mental and emotional well-being, which may include seeking professional support and resources (Wagman & Parks, 2021). A significant challenge for social workers is maintaining appropriate emotional boundaries while providing empathy and compassion to their clients and families (Keyter & Roos, 2015). This challenge can be intensified for recent graduates, who may struggle to detach themselves emotionally from work. Thus, new graduate social workers must understand and address STS through developing effective prevention and intervention strategies. However, it is important to note there is little research on effective STS management approaches, particularly those working in stressful clinical settings (Owens-King, 2019).

Social Workers, Resilience, and Post-Traumatic Growth

Social workers, regularly immersed in trauma narratives through their empathetic engagement with clients, are notably prone to STS (Badger et al., 2008). While integral to their role, this empathetic engagement also significantly heightens the risk of STS (Sabin-Farrell & Turpin, 2003). Furthermore, social work’s deep emotional investment and advocacy can amplify this risk (Harrison & Westwood, 2009). Social workers across various contexts are susceptible to STS, with risk factors including inadequate supervision, lack of social support, high caseloads, younger age, and less professional experience (Bride, 2007).

A key question in this domain is whether prolonged exposure to traumatic narratives leads to desensitization in more experienced social workers. Desensitization here refers to a decrease in emotional responsiveness due to repeated trauma exposure (Akten et al., 2023). Research indicates that while continuous exposure can lead to some level of desensitization, it does not invariably diminish empathy or care quality. Adams et al. (2006) suggest that seasoned social workers may develop effective coping mechanisms to manage their emotional responses. This adaptation should not be misconstrued as a lack of empathy. Rather, Waggamen et al. (2017) propose that experienced social workers often attain a balance between empathy and emotional regulation, which is essential for their well-being and career longevity. This equilibrium is not a sign of emotional numbness but rather a sophisticated navigation of the emotional demands of their work (Haight et al., 2017).

These insights underscore the importance of institutional support and mentoring in helping social workers navigate the potential trauma they encounter. While STS is prevalent among social workers, not all individuals exposed to traumatic narratives develop the condition (Lev et al., 2022). The variability in responses to trauma exposure can be attributed to factors like personal self-care practices, professional support systems, and maintaining a healthy work-life balance (Cohen & Collens, 2013). Moreover, the concept of post-traumatic growth, as outlined by Tedeschi and Calhoun (2004), introduces the possibility of positive changes following indirect trauma exposure, such as enhanced resilience, personal growth, or a renewed sense of purpose.

Thus, while social workers are at a heightened risk for STS due to their close work with trauma narratives, the outcomes of such exposure are not uniformly detrimental. Elements like self-care, professional support, a balanced lifestyle, and the potential for post-traumatic growth play pivotal roles in mitigating this risk. This broader understanding of the impact of trauma work on social workers emphasizes the necessity of comprehensive support systems within the profession, fostering a more holistic understanding of their experiences and promoting both personal and professional development.

Method

Study Design

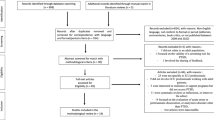

The purpose of this exploratory study is two-fold: (1) to provide insight into the experiences of pediatric emergency room social workers (PERSW) with STS and (2) to identify the coping mechanisms they use to handle STS. To achieve these objectives, the study employed a descriptive phenomenological approach. This methodology is grounded in the principles outlined by Husserl (2013) and further expounded by Creswell and Poth (2016). Descriptive phenomenology focuses on exploring the subjective experiences of individuals, offering an in-depth understanding of their perceptions, thoughts, and feelings. This approach is particularly suited to this study as it allows for exploring the participants’ experiences from an insider’s perspective, providing rich, detailed accounts of their encounters with STS. By concentrating on the pragmatic descriptions of experiences, especially in contexts such as healthcare, as explained by Matua and Van Der Wal (2015), this approach facilitates a deep exploration of the realities experienced by PERSWs. It emphasizes understanding the meanings that PERSWs assign to their experiences of STS, the conditions and contexts that shape these experiences, and how they navigate their professional roles amidst these challenges. This methodological choice is also valuable in exploring poorly understood or under-researched aspects of experiences, such as living through STS in healthcare settings. As suggested by Willis et al. (2016), focusing on descriptive phenomenology allows the research to uncover nuanced and often overlooked facets of experiences that are critical in understanding the complexity of STS in the lives of PERSWs.

Participants and Recruitment Activities

Participants were recruited based on the following inclusion criteria: PERSW with at least one year of work experience and worked at a level 1 trauma center. We recruited PERSW with at least one year or more of work experience because of the likelihood of experiencing STS and its effects (Cieslak et al., 2013), which help provide more nuanced insights into their personal experiences and coping strategies. Additionally, PERSW confirmed their employment status by displaying their employment badge. The study specifically focused on PERSWs; therefore, other emergency room staff, such as physicians, nurses, and non-medical staff, were excluded. A purposive snowball sampling technique was utilized to recruit participants. This method was chosen for its effectiveness in reaching a specific subset of professionals who meet the study’s criteria. Participants were recruited through word-of-mouth, social media, and physical flyers, also placed in strategic locations such as Level 1 trauma centers and local coffee shops frequented by healthcare professionals. The first author undertook a proactive approach by cold-calling several Level 1 trauma centers. This involved discussions about the study’s aims and objectives with relevant personnel to encourage participation. This direct outreach was instrumental in reaching a broader audience of PERSWs who may not have been accessible through other recruitment methods. Notably, four level 1 pediatric trauma centers in metropolitan areas such as Texas and Ohio reached out to participate by contacting the number on the flyer. Those eligible received an email with the necessary information regarding the nature of the study, along with a copy of the informed consent. Participants were compensated with a $20 Starbucks gift card for their time and participation.

Data Collection

Before recruitment and data collection, this study was reviewed and approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board (2022B0094). The first author conducted semi-structured open-ended interviews with participants until no new information was forthcoming and data saturation was attained. All interviews were conducted over Zoom between May 2022 and June 2022, lasting between 60 and 90 min. The interviews began with briefly explaining the study’s purpose, addressing the participants’ concerns, and obtaining verbal consent for participation and permission for audio recording. To ensure participants felt comfortable sharing, the interviewer built rapport, expressed empathy, and provided a safe space for participants to share their experiences. Each participant was assigned a pseudonym to protect their identity and confidentiality. The interview guide included questions assessing demographic information and participants’ experiences with STS, such as factors contributing to its development and strategies they have used to manage and prevent adverse symptoms (See Table 1). All interviews ended by asking participants if there were anything else they would like to add to their stories.

Data Analysis

The data analysis process for this study was carefully structured to ensure a thorough and accurate interpretation of the interviews conducted with participants. The interviews were audio-recorded on Zoom and transcribed verbatim by Landmark Associates, a professional transcription service, to maintain the integrity of the participants’ responses. The transcribed data was then uploaded into NVivo 12, a qualitative data analysis software, to facilitate efficient and systematic coding. The analysis used Colaizzi’s methods, which included the following seven steps: (1) Familiarization: Each researcher read the transcripts multiple times (2–4 times) to fully immerse themselves in the data and understand the nuances of the discussions about STS. (2) Identification of significant statements: the researchers identified and noted significant statements relevant to the studied phenomenon. (3) formulation of the meanings: the researchers formulated meanings from the significant statements. (4) clustering the themes: the researchers categorize the formulated meanings into themes. (5) development of an exhaustive description: the researchers integrated the themes into an exhaustive description of the phenomenon. (6) production of the fundamental structure: the researchers summarized the exhaustive description into concise statements that captured the essence of the phenomenon. Complementing Colaizzi’s method (Colaizzi, 1978), a thematic analysis was chosen for its flexibility and epistemological compatibility with the study’s goals. The first and second authors thoroughly read and discussed the transcripts before coding. The coding began with a line-by-line analysis (Glaser, 2007), where each researcher generated codes independently. Regular bi-weekly meetings were held for the coders to compare findings, develop additional codes, and refine existing ones. These meetings facilitated a collaborative approach to the coding process, ensuring consistency and depth in the analysis. Discrepancies in coding were resolved through discussions and reflections, following Levitt et al.‘s (2017) recommendations, thereby enhancing the reliability of the coding process. In the final coding phase, the last round of codes was meticulously reviewed to develop the final themes that accurately represented the data. This process involved careful consideration of multiple interpretations of the data (Patton,2014) to ensure that the themes were comprehensive and reflective of the participants’ experiences.

To ensure rigor and reliability in the study, Lincoln and Guba’s criteria for qualitative research (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) were rigorously applied. Credibility was achieved through bracketing, where researchers consciously set aside their preconceptions and subjective insights about the phenomenon under study. This approach was vital in maintaining objectivity and minimizing bias in the interpretation of the data. For dependability, an audit trail was meticulously maintained, recording the progression of the study, including details like recruitment responses, interview dates, and durations. This record-keeping provided a transparent and traceable account of the research process. Peer debriefing sessions were an integral part of the analysis, ensuring consistency and validity of the information gathered. These sessions served as a platform for addressing and resolving any disagreements or inconsistencies in the interpretation of the data. Finally, member checking was employed as a crucial step in the analysis. Participants were allowed to review and corroborate the interpretations of their interviews. This process clarified any potential misinterpretations of their intended meanings, thereby enhancing the accuracy of the study’s findings. Pseudonyms were used throughout the study to ensure the confidentiality and anonymity of the participants, safeguarding their identities and the sensitive nature of the information they provided.

Findings

In our study, we enrolled 23 master’s level social workers with at least a year of experience in pediatric emergency rooms from four level 1 trauma centers in Ohio and Texas. with an age range from 24 to 47 years (M = 36.91, SD = 7.08). All participants were cisgender women, and the sample was predominantly White (96%). (See Table 2).

The following three themes emerged from the analysis: (a) the trauma of the job, (b) the effect of STS, and (c) secondary traumatic stress coping strategies (see Tables 2 and 3). These themes are further discussed in greater detail in the section below.

Theme 1: The Trauma of the Job

All 23 participants stated that working as pediatric social workers involves significant exposure to trauma, primarily due to close interactions with families and children in stressful circumstances. The interview data coded in this category consisted of words and phrases the participants used to share the most emotional and challenging aspect of their job. The women shared accounts of their most challenging moments on the job, ranging from delivering news of death to managing cases of severe child abuse cases. Yara shared:

I think secondary trauma is the hardest thing to deal with. Hearing some of those stories, especially being in the children’s hospital and having to deal with many situations of abuse or maltreatment, can be emotionally draining, especially when you are working a night shift, and you keep getting those cases.

Others, like Libby, noted the struggle to maintain composure while wrestling with the overwhelming empath that can arise in difficult situations. Libby shared:

I think discussing the topic of death is probably the hardest one for me, especially because I am a parent myself. You are trying to keep your emotions in check, but I am not a robot, so I cannot. I try my hardest, but it is very difficult, and that is an understatement when a child dies just because there is this almost disbelief no matter what the circumstances are. … I think, for the most part, I have been doing this long enough where I feel confident in my clinical skills to offer support, etc., but I feel like there is absolutely nothing you can say to the parents.

Additionally, Amanda noted “that deaths are hard no matter how many times you do it.” She further explained:

I feel like you could do everything right, but this tragedy still exists. You could follow all the rules and all the recommendations, and there is still this—just this unexplained tragedy of the death of an infant.

However, some participants shared that the traumatic experiences confronted in their jobs continue to impact them significantly even today. Shree expressed, “The cases that stuck with me the most were when I started my career. I think my first death that I had, my first really bad physical abuse case that I had.”

Pediatric emergency room social workers face significant challenges due to the stress and trauma they experience in their daily work. They find it difficult to cope with the emotional impact of their experiences on the job. These findings indicate that their work takes a toll on them, making it difficult to deal with their challenges.

Theme 2: The Effects of STS on the Body

Seventeen out of twenty-three participants shared in-depth insights into STS’s physical and emotional effects, emphasizing its profound impact on pediatric emergency room social workers’ well-being. This distinction draws attention to the complex nature of STS, underscoring its pervasive influence beyond immediate, direct trauma exposure to include enduring psychological and physiological consequences for professionals in this field. The women reported both physical and mental symptoms at certain points throughout their careers. Jasmine shared:

I believe sleep becomes a challenge, particularly after difficult cases. There appears to be an adrenaline surge that aids in completing these cases, which keeps me alert and hypersensitive.

Similarly, Mariah maintained the following:

I don’t know. There’s a certain amount of physical stress you feel. At the end of that shift, I felt like I could just put my head down and sleep for 20 h. It’s draining. Deaths are draining. I mean, this person is not even related to me, but again, there are no words.

Another pediatric emergency room social worker recalled how the demands and effects of the job can sometimes leave a feeling of self-doubt. Sharrell stated:

I remember lying in bed and saying, “Oh, I do this. Then what about that I did?” Just not being able to fall asleep. I’m struggling with that.

The evidence implies that the indications don’t solely signify the instant effect of STS but also provoke anxieties about the enduring health consequences for individuals who are persistently subjected to such nerve-racking work environments.

Theme 3: Coping Strategies for STS

All the women in the study focused on their methods of coping with STS by using a variety of strategies as a form of resistance. The research data was carefully analyzed and categorized based on the participants’ words and phrases describing the importance of work-life balance and a conscious effort to maintain a clear boundary between one’s professional and personal life. Joviann shared her strategy for respite. She explained:

When I’m home, I don’t think about being there. I don’t have my work emails on my phone. I don’t typically engage in conversation about it. Being present at home with my family and being outside are the things that I think are helpful so that when the week rolls back around, and I have to go back in, I don’t feel overwhelmed.

Additionally, Jenn understood the importance of self-care and that it was not just a concept but a lifeline. She explained:

Of course, they bang self-care in your head in college, right? But I had to do that. With me, that helps. I exercise. I work out three to four times a week and do it right after work. Right when I get home, I change into workout clothes and go to the gym. That helps me. I do it daily, but I check in with myself.

Diva also explained that the key to self-care relies on the freedom to choose. She explained, “I spend time doing things I enjoy. Whether that’s honestly happy hour with friends or watching nine hours of Netflix. I honestly do whatever I feel like that day. I think that independence and not being tied to a self-care plan have benefitted me.” She further explained that cultivating a practice of self-care is important to preserve and maintain emotional resilience. She shared:

“As I said, I try to have strict boundaries, so I avoid them—especially in cases involving the media, which sometimes happens in our role. Whether it’s a very violent injury or just some other tragic injury that hits the media, I avoid all that. Some people like to know what happens, which gives them closure. For me, I don’t. I avoid news specific to that scenario. I don’t look in charts, which we’re not supposed to do anyway. I don’t look in charts to follow up and see what happened.”

Finally, Jordan took a different approach to coping and finding sanctuary within her established boundaries. Jordan revealed.

From that moment, I thought I was going on autopilot because that’s how I operate within my boundaries. If I start to feel sad, or I start to feel maybe a tear, or I start to feel it in my throat, getting choked up in my throat, I remind myself it’s not my loss. This has nothing to do with me. When the event’s happening, I am focused on the work.

Discussion

The current study sheds light on the multifaceted challenges pediatric emergency room social workers face in pediatric settings. The qualitative analysis revealed three key themes — each offering deep insights into the traumatic aspects of their work, the impact of STS, and the varied coping strategies they employ. These themes resonate with existing research and add further depth to our understanding of the demands placed on these professionals.

The Trauma of the Job

The narratives of Yara, Libby, Shree, and Amanda illustrate the emotional challenges inherent in pediatric social workers working in the emergency room. These professionals often deal with situations involving child mortality, severe violence, and distressing cases of abuse. Such scenarios substantially increase their risk of experiencing STS, as the emotional toll of these events is often profound and multifaceted. This elevated risk aligns with the findings of (Bride, 2007), who noted a high occurrence of STS among social workers, particularly those in high-stress environments like emergency rooms. The immediate and long-term psychological impact of trauma focuses on the importance of building effective social support systems for these social workers. These findings echo Figley’s (1995) concept of ‘compassion fatigue,’ where prolonged exposure to traumatic narratives gradually erodes empathy and emotional energy in caregivers. Killian (2008) provides further exploration into the challenges and risks associated with trauma assistance, explaining the complex dynamics that ERSWs navigate regularly.

Herman’s (1992) seminal work on the lasting impact of trauma exposure is particularly relevant in this context. It emphasizes the importance of addressing the immediate reactions to traumatic events and their enduring psychological and emotional repercussions on healthcare professionals. This necessitates a dual approach to support - one that provides immediate crisis intervention and another that offers ongoing psychological support to address the cumulative effects of trauma exposure. Moreover, the concept of ‘vicarious traumatization,’ as discussed by Pearlman and Saakvitne (1995), is crucial in understanding the profound impact that working with trauma survivors can have on pediatric emergency room social workers. This refers to the changes in the helper’s inner experience, worldview, self-perception, and sense of self and safety because of empathic engagement with a client’s trauma. To effectively support ERSWs, healthcare institutions should implement strategies that foster resilience and provide coping mechanisms. Rothschild (2006) suggested that these strategies include providing trauma awareness, regular supervision, opportunities for professional development, and a focus on self-care practices. A comprehensive approach that focuses on professional development and personal well-being is essential for sustaining the emotional health and professional efficacy of ERSWs in pediatric emergency settings. By addressing these workers’ immediate and long-term needs, we can better ensure their capacity to provide high-quality care to the vulnerable populations they serve.

The Effects of STS on the Body

The experiences of pediatric emergency room social workers like Jasmine, Mariah, and Sharrell, draw attention to this condition’s complex and multifaceted nature of STS. Jasmine’s struggles with sleep and Mariah’s physical exhaustion post-cases are symbolic of the profound physical toll that STS can exert on professionals. These physical symptoms witnessed in Jasmine and Mariah are consistent with findings from (Cieslak et al., 2013), who documented similar physical symptoms in people who were exposed to trauma. Furthermore, Sharrell’s experience notes the psychological effect of STS. The pressure of the job can lead to chronic overthinking, which can disrupt sleep patterns and result in heightened stress and anxiety. The psychological impact of STS experienced by Sharrell was consistent with the observation by Bride (2007).

The psychological impact of STS is significant, often leading to symptoms such as alertness, intrusive thoughts, and a heightened state of arousal (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Over time, these symptoms can worsen, resulting in reduced empathy, job dissatisfaction, and burnout among pediatric emergency room social workers, impacting the quality of care provided. Figley’s (1995) work on compassion fatigue reinforces these findings and explains how ongoing exposure to traumatic narratives can erode a caregiver’s emotional resilience. Furthermore, given the multifaceted nature of the issue, it is vital to implement comprehensive and tailored interventions that prioritize the individual’s well-being and maintain a high standard of care. A comprehensive approach is needed, including institutional support, ongoing professional development, and self-care strategies (Ray et al., 2013). Addressing STS effectively requires a multi-pronged strategy, ensuring that ERSWs can manage their immediate stress responses and build resilience against the long-term effects of their challenging work environment.

Coping Strategies for STS

Pediatric emergency room social workers encounter an assorted set of challenges, making it vital for them to adopt diverse and holistic coping methods to deal with STS. The personal strategies employed by professionals like Joviann, Diva, Jordan, and Jenn highlighted the various ways of managing STS. Joviann’s reliance on spirituality as a form of coping aligns with Pargament’s (1998) findings on the therapeutic benefits of spirituality in addressing trauma. This spiritual approach helps Joviann find meaning and solace amidst the distressing experiences encountered in their work. On the other hand, Diva emphasized self-care activities, such as engaging in social gatherings or leisure activities, which echoes the recommendations found in trauma-care literature. Turgoose et al. (2017) emphasized the importance of self-care as a critical buffer against work-related stress. They emphasize the importance of activities that allow for mental and emotional disengagement from the job demands, including activities ranging from socializing to hobbies or relaxation techniques.

Jenn’s approach to physical activity post-work focuses on the interconnectedness of physical and mental health. This practice is supported by the work of Killian (2008) and Ratey (2008), who have noted the psychological benefits of physical exercise, including stress reduction and improved mood regulation. For pediatric emergency room social workers, regular physical activity can be a valuable tool for ERSWs to mitigate their work’s physical and emotional toll. Additionally, incorporating structured debriefing sessions, as Mitchell (1983) suggested in his critical incident stress debriefing model, can be valuable to coping strategies. These sessions provide a space for pediatric emergency room social workers to process traumatic events collectively, helping to mitigate the effects of STS. Implementing mindfulness and relaxation techniques, as discussed by Kabat-Zinn (1994), also offers potential benefits. These practices can help ERSWs cultivate a sense of present-moment awareness and emotional regulation, counteracting the high-stress nature of their work.

Bridging these personal coping strategies with academic research explains the need for a holistic framework that supports ERSWs individually and within their institutional environments. This research aims to develop a comprehensive guide that addresses the intricate challenges faced by ERSWs, offering practical strategies to manage STS effectively and promote overall well-being in the demanding environment of pediatric emergency settings.

Limitations of the Study

This study had notable limitations. First, the participant pool was exclusively composed of pediatric emergency room social workers. This homogeneity limits the generalizability of the findings to other social work environments. As such, the insights and themes identified should be cautiously applied to different practice settings, considering the unique dynamics and challenges they might present. Second, the demographic composition of the participants predominantly consisted of cis-gendered white women. This lack of diversity in race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation means that the study may not fully capture the varied experiences and perspectives within the broader social work community.

Recommendations for New Graduate Social Workers

Considering these findings, this research underscores the critical importance of proactive self-care, robust professional support, and comprehensive institutional resources for managing STS in social work settings, with a particular focus on pediatric emergency room environments. A specialized toolkit has been developed to aid new social workers transitioning into these demanding roles. Drawing from the narratives of experienced professionals and empirical data, this toolkit offers a range of practical strategies and self-care insights. Its primary objective is to equip new social workers with the tools to navigate and manage the challenges and stressors inherent in pediatric emergency settings. The toolkit addresses various aspects of STS management, including coping mechanisms, resilience-building practices, and strategies for maintaining personal well-being in high-stress environments.

To ensure the toolkit’s effectiveness in real-world settings, it is essential to first widely disseminate the developed toolkit. We plan to disseminate the toolkit via various social media platforms, using hashtags to facilitate discussions where newly graduated social workers can share insights about using the toolkit. Additionally, we plan to hold a podcast session to discuss the toolkit’s components and conduct interviews with experienced social workers who can provide real-life examples. Finally, we aim to collaborate with social work schools to incorporate the toolkit into their professional development curriculum, ensuring we reach our intended audience.

It is essential to note that this toolkit has yet to be empirically tested. Although it has been designed based on current research and practical experience, its effectiveness in real-world settings has yet to be evaluated. Therefore, it is recommended to approach the implementation and impact of this toolkit with a commitment to ongoing assessment and adaptation. Future steps will involve rigorous testing for validity, including diverse perspectives to ensure broad applicability across various social work settings and demographics, underscoring a commitment to evidence-based practice and continuous improvement.

Conclusion

This study provides important insights into the experiences of pediatric emergency room social workers with STS. It underscores the significant impact of STS on these professionals and emphasizes the need for specific strategies to manage this challenge. Developing a toolkit for new graduates in this field is a step towards addressing the unique needs of this group. The implications of this research extend to social work education and practice. It emphasizes the need for specialized training and resources in high-stress environments, particularly pediatric emergencies. Educators and practitioners should consider incorporating targeted strategies into curriculum and practice better to prepare new social workers for the realities of STS. This study contributes to the existing literature by focusing on pediatric emergency room social workers, often underrepresented in STS research. It adds depth to our understanding of how STS manifests in this specific context and offers practical solutions for mitigation. Readers should take away the importance of recognizing and addressing the unique challenges faced by social workers in pediatric emergency settings. The findings and recommendations of this study aim to enhance the well-being of these professionals, ultimately leading to improved care for the vulnerable populations they serve.

References

Adams, R. E., Boscarino, J. A., & Figley, C. R. (2006). Compassion fatigue and psychological distress among social workers: A validation study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(1), 103–108.

Akten, I. M., Yıldırım, T. B., & Dığın, F. (2023). Examining the burnout levels of healthcare employees and related factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Work (Reading, Mass.), Preprint, 1–11.

American Psychiatric Association, D., &, & Association, A. P. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (Vol. 5). American psychiatric association Washington, DC. https://www.academia.edu/download/38718268/csl6820_21.pdf.

Badger, K., Royse, D., & Craig, C. (2008). Hospital social workers and indirect trauma exposure: An exploratory study of contributing factors. Health & Social Work, 33(1), 63–71.

Beck, C. T. (2011). Secondary traumatic stress in nurses: A systematic review. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 25(1), 1–10.

Bernard, J. M., & Goodyear, R. K. (1998). Fundamentals of clinical supervision. Allyn & Bacon. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1997-36712-000.

Bride, B. E. (2007). Prevalence of secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Social Work, 52(1), 63–70.

Butler, L. D., Carello, J., & Maguin, E. (2017). Trauma, stress, and self-care in clinical training: Predictors of burnout, decline in health status, secondary traumatic stress symptoms, and compassion satisfaction. Psychological Trauma: Theory Research Practice and Policy, 9(4), 416.

Carello, J., & Butler, L. D. (2014). Potentially perilous pedagogies: Teaching Trauma is not the same as trauma-informed teaching. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 15(2), 153–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2014.867571.

Choi, G. Y. (2011). Organizational impacts on the secondary traumatic stress of social workers assisting family violence or sexual assault survivors. Administration in Social Work, 35(3), 225–242.

Cieslak, R., Anderson, V., Bock, J., Moore, B. A., Peterson, A. L., & Benight, C. C. (2013). Secondary traumatic stress among mental health providers working with the military: Prevalence and its work- and exposure-related correlates. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 201, 917–925.

Cohen, K., & Collens, P. (2013). The impact of trauma work on trauma workers: A metasynthesis on vicarious trauma and vicarious posttraumatic growth. Psychological Trauma: Theory Research Practice and Policy, 5(6), 570.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310.

Colaizzi, P. F. (1978). Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. https://philpapers.org/rec/COLPRA-5.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage.

Figley, C. R. (1995). Compassion fatigue: Toward a new understanding of the costs of caringhttps://psycnet.apa.org/record/1996-97172-001.

G Glaser, B. (2007). Doing formal theory. The Sage Handbook of Grounded Theory, Part II, 97–113.

Gil, S., & Weinberg, M. (2015). Secondary trauma among social workers treating trauma clients: The role of coping strategies and internal resources. International Social Work, 58(4), 551–561. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872814564705.

Haight, W., Sugrue, E., Calhoun, M., & Black, J. (2017). Everyday coping with moral injury: The perspectives of professionals and parents involved with child protection services. Children & Youth Services Review, 82, 108–121. a9h.

Harrison, R. L., & Westwood, M. J. (2009). Preventing vicarious traumatization of mental health therapists: Identifying protective practices. Psychotherapy: Theory Research Practice Training, 46(2), 203.

Herman, J. L. (1992). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5(3), 377–391.

Howard, F. (2008). Managing stress or enhancing wellbeing? Positive psychology’s contributions to clinical supervision. Australian Psychologist, 43(2), 105–113.

Husserl, E. (2013). The idea of phenomenology: A translation of Die Idee Der Phänomenologie Husserliana II (Vol. 8). Springer Science & Business Media.

Jay Miller, J., Lee, J., Niu, C., Grise-Owens, E., & Bode, M. (2019). Self-Compassion as a predictor of Self-Care: A study of Social Work clinicians. Clinical Social Work Journal, 47(4), 321–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-019-00710-6.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and futurehttps://psycnet.apa.org/record/2003-03824-002?casa_token=a-NwUiDDWt0AAAAA:asp7XpkOHcHqktDPKiwsg-yl1G1bJX-6Xe73MhaV0U36862pOZ91CtcfkdF5YwzclcFO7bQNwUsGXWX88FuJ-SQ.

Kelly, S. (2020). Acknowledging privilege in an intentional community while working with adolescents in residential treatment. Social Work with Groups, 43(1/2), 104–108. a9h.

Keyter, A., & Roos, V. (2015). Mental health workers’ coping strategies in dealing with continuous secondary trauma. The Social Work Practitioner-Researcher, 27(3), 365–382.

Killian, K. D. (2008). Helping till it hurts? A multimethod study of compassion fatigue, burnout, and self-care in clinicians working with trauma survivors. Traumatology, 14(2), 32–44.

Lee, S. H., Lee, S. H., Lee, S. Y., Lee, B., Lee, S. H., & Park, Y. L. (2018). Psychological health status and health-related quality of life in adults with atopic dermatitis: A nationwide cross-sectional study in South Korea. Acta Dermato-Venereologica, 98(1), 89–97. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-2797. Embase.

Lev, S., Zychlinski, E., & Kagan, M. (2022). Secondary traumatic stress among Social workers: The Contribution of Resilience, Social Support, and exposure to violence and ethical conflicts. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 13(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1086/714015.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry sage. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=2oA9aWlNeooC&oi=fnd&pg=PA7&dq=Lincoln,+Y.+S.,+%26+Guba,+E.+G.+(1985).+Naturalistic+inquiry.+sage.&ots=0vjCRaOauo&sig=zp-UszJNzD5Xkp3JGikLS2Udq20.

Lindblom, K. M., Linton, S. J., Fedeli, C., & Bryngelsson, I. L. (2006). Burnout in the working population: Relations to psychosocial work factors. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 13, 51–59.

Lounsbury, C. J. (2006). Risk and protective factors of secondary traumatic stress in crisis counselors. The University of Maine. https://search.proquest.com/openview/f29398d669f839fd687beb9133d39d2c/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y&casa_token=MjBie_jCPBAAAAAA:yJrMX0mMNeS5hleq8yPX6FQ-NDYm3m4wWkdSYvOpNZUP5Im6N78nrDcn-LNPJSjnAin0mwBr

Manning-Jones, S., de Terte, I., & Stephens, C. (2016). Secondary traumatic stress, vicarious posttraumatic growth, and coping among health professionals; a comparison study. New Zealand Journal of Psychology (Online), 45(1), 20.

Marsick, V. J., & Watkins, K. (2015). Informal and incidental learning in the workplace (Routledge Revivals). Routledge. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=nW7bCQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Marsick,+V.+J.,+%26+Watkins,+K.+(2015).+Informal+and+incidental+learning+in+the+workplace+(Routledge+Revivals).+Routledge.&ots=tKk0YByV3z&sig=rcBxKRhuT2l0WHxuZXgmUu0OWJs

Matua, G. A., & Van Der Wal, D. M. (2015). Differentiating between descriptive and interpretive phenomenological research approaches. Nurse Researcher, 22(6).

Michalopoulos, L. M., & Aparicio, E. (2012). Vicarious trauma in Social workers: The role of Trauma History, Social Support, and years of experience. Journal of Aggression Maltreatment & Trauma, 21(6), 646–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2012.689422.

Mitchell, J. T. (1983). When disaster strikes: The critical incident stress debriefing process. In Journal of emergency medical services (pp. 36–39).

Morrison, E. W. (2011). Employee Voice Behavior: Integration and directions for Future Research. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 373–412. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2011.574506.

Ohnishi, K., Kitaoka, K., Nakahara, J., Välimäki, M., Kontio, R., & Anttila, M. (2019). Impact of moral sensitivity on moral distress among psychiatric nurses. Nursing Ethics, 26(5), 1473–1483.

Owens-King, A. P. (2019). Secondary traumatic stress and self-care inextricably linked. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 29(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2018.1472703.

Pargament, K. I., Smith, B. W., Koenig, H. G., & Perez, L. (1998). Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 710–724.

Pearlman, L. A., & Saakvitne, K. W. (1995). Trauma and the therapist: Countertransference and vicarious traumatization in psychotherapy with incest survivors. WW Norton & Co.

Quick, J. C. E., & Tetrick, L. E. (2003). Handbook of occupational health psychology. American Psychological Association. https://psycnet.apa.org/books/TOC/10474.

Ratey, J. J. (2008). Spark: The revolutionary new science of exercise and the brain. Hachette UK.

Renkiewicz, G. K., & Hubble, M. W. (2022). Secondary Traumatic Stress in Emergency Services Systems (STRESS) project: Quantifying and Predicting Compassion fatigue in Emergency Medical Services Personnel. Prehospital Emergency Care, 26(5), 652–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2021.1943578.

Robins, P. M., Meltzer, L., & Zelikovsky, N. (2009). The experience of secondary traumatic stress upon care providers working within a children’s hospital. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 24(4), 270–279.

Rothschild, B. (2006). Help for the helper: The psychophysiology of compassion fatigue and vicarious trauma. WW Norton & Company.

Sabin-Farrell, R., & Turpin, G. (2003). Vicarious traumatization: Implications for the mental health of health workers? Clinical Psychology Review, 23(3), 449–480.

Schön, D. A. (2017). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781315237473/reflective-practitioner-donald-sch%C3%B6n.

Schwarzer, R., & Knoll, N. (2003). Positive coping: Mastering demands and searching for meaninghttps://psycnet.apa.org/record/2003-02181-025.

Shepherd, M. A., & Newell, J. M. (2020). Stress and health in social workers: Implications for self-care practice. Best Practices in Mental Health, 16(1), 46–65.

Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2007). The recovery experience questionnaire: Development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(3), 204.

Sprang, G., Craig, C., & Clark, J. (2011). Secondary traumatic stress and burnout in child welfare workers. Child Welfare, 90(6), 149–168.

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18.

Turgoose, D., Glover, N., Barker, C., & Maddox, L. (2017). Empathy, compassion fatigue, and burnout in police officers working with rape victims. Traumatology, 23(2), 205.

Wagaman, M. A., Geiger, J. M., Shockley, C., & Segal, E. A. (2015). The role of empathy in burnout, compassion satisfaction, and secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Social Work, 60(3), 201–209.

Wagman, K. B., & Parks, L. (2021). Beyond the command: Feminist STS research and critical issues for the design of Social machines. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5(CSCW1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1145/3449175.

Willis, D. G., Sullivan-Bolyai, S., Knafl, K., & Cohen, M. Z. (2016). Distinguishing features and similarities between descriptive phenomenological and qualitative description research. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 38(9), 1185–1204.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Benavides, J.L., Modeste-James, A., Osborn, P. et al. Addressing Secondary Traumatic Stress in Pediatric Emergency Room Social Workers: A Toolkit for New Graduates. Clin Soc Work J (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-024-00930-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-024-00930-5