Abstract

Background

The ICU (intensive care unit) involves potentially traumatic work for the professionals who work there. This narrative review seeks to identify the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among ICU professionals; how PTSD has been assessed; the risk factors associated with PTSD; and the psychological support proposed.

Methods

Three databases and editorial portals were used to identify full-text articles published in English between 2009 and 2022 using the PRISMA method.

Results

Among the 914 articles obtained, 19 studies met our inclusion criteria. These were undertaken primarily during the Covid-19 period (n = 12) and focused on nurses and assistant nurses (n = 10); nurses and physicians (n = 8); or physicians only (n = 1). The presence of mild to severe PTSD among professionals ranged from 3.3 to 24% before the pandemic, to 16–73.3% after the pandemic. PTSD in ICU professionals seems specific with particularly intense intrusion symptoms. ICU professionals are confronted risk factors for PTSD: confrontation with death, unpredictability and uncertainty of care, and insecurity related to the crisis COVID-19. The studies show that improved communication, feeling protected and supported within the service, and having sufficient human and material resources seem to protect healthcare professionals from PTSD. However, they also reveal that ICU professionals find it difficult to ask for help.

Conclusion

ICU professionals are particularly at risk of developing PTSD, especially since the Covid-19 health crisis. There seems to be an urgent need to develop prevention and support policies for professionals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

The ICU receives, within a context of emergency and unpredictability, patients with serious pathological conditions whose vital risk is engaged. In these services, the mortality rate is high, varying between 20 and 25% depending on the services, and the threat of patient death is omnipresent [1]. The announcement of difficult diagnoses and severe prognoses is part of the daily life of professionals, to which must be added the patients’ moral and physical suffering, the degradation of the body, and the pain of families experiencing care of a loved one who is in distress and fear.

Since 2020, there have been unprecedented epidemic waves characterized by extreme tension [2] related to the risk of being contaminated or of contaminating others, and to the lack of trained intensive care personnel and of personal protective equipment for these workers. In addition, the lack of specific treatments, patient deaths, and the distress of families deprived of visits also contributed to a sense of helplessness among caregivers. Finally, issues of bed availability and the risk of patient triage raised many ethical and moral dilemmas within the ICU teams [3].

This work environment brings together all the risk factors for PTSD described by the Diagnostic Manual of Mental Disorders (DSMV) [4]: having to confront death—and the threat of death or serious illness—personally, or having to deal with a loved one’s (family member’s or close friend’s) serious illness. The clinical picture of PTSD is dominated by three dimensions, 1/the intrusion symptoms with nightmares, repetitive memories, hallucinations, or heightened states of alertness about traumatic event; 2/avoidance symptoms in an attempt to avoid thinking about, or having to face, traumatic situations; and 3/neurovegetative symptoms such as sleep disorders, hypervigilance, and irritability [4]. Shame and guilt are also widely described and are frequently associated with depressive manifestations related to feeling at fault [5]. All these symptoms are observable more than 1 month after exposure to the traumatic event.

We aimed to undertake a scoping review of published literature concerning PTSD in ICU healthcare workers. We focused on three broad questions: first, what is the prevalence of PTSD in critical care workers in published research before and after COVID?; second, what are the specificities of PTSD in intensive care workers and the risk factors associated with PTSD?; third, what are protective factors and the psychological support proposed by studies ?

Material and methods

This literature review is based on the narrative review method, which is preferred when one wishes to conduct an analysis of a set of studies that have used diverse methodologies with different theoretical conceptualizations [6]. Narrative reviews synthesize the results of studies without reference to the statistical significance of the results [7]. They are relevant when one wishes to make connections between studies in order to develop or evaluate a new theory or future recommendation.

Databases and search strategy

We considered all peer-reviewed full-text articles reporting an empirical study published in English between 2009 and 2022. The search for, and selection of, articles were conducted between January and March 2022, according to PRISMA guidelines. Five databases and editorial portals (Medline via PubMed, PsychINFO, Web of Science, Elsevier’s ScienceDirect, and Ovid (APA) were screened using the following terms in the title, the abstract, the keywords or the MeSH headings: (“Post-traumatic stress disorders” OR “PTSD” OR “Traumatic stress” OR “Acute stress disorder”) AND (“Healthcare” OR “Healthcare workers” OR “healthcare providers” OR “physicians ICU” OR “Nurse”) AND (“Intensive care units” OR “ICU” OR “Critical care”). We had no limitations based on geography, healthcare systems, or demographic factors. This choice of keywords allowed us to bring out the studies concerning ICU and PTSD with all the professionals combined.

Eligibility criteria

Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methodology studies examining PTSD in ICU healthcare workers (HCW) were included. Studies had to be conducted on ICU nurses, assistant nurses, physicians, and residents working with adult patients.

We excluded the following studies: (1) systematic; meta-analysis; empirical research; feedback; letters to the editor; recommendations; (2) studies focused on a population other than the ICU professionals included in our study (physical therapists; radiologists; administrative services; and so on); (3) studies conducted among sectors other than adult patients in ICU, such as patients within pediatric ICU or emergency services; (4) studies whose diagnosis did not relate to direct exposure to trauma, e.g., secondary or vicarious trauma or symptomatology assessed within 1 month of the event, e.g., acute stress or traumatic dissociation; (5) studies that addressed disorders other than PTSD, e.g., compassion fatigue, anxiety, burnout; (6) studies that addressed resiliency without examining trauma; (8) studies that spoke of trauma as a possible outcome but which did not measure it.

Selection process and data extraction

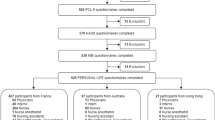

The results were screened by title and abstract by three independent reviewers (VD, AL, ALP). Where reviewers were in disagreement, the reasons for this were discussed and consensus was reached. Relevant articles were retrieved for full-text reading to identify relevant studies. Each reviewer (VD, AL, ALP) independently reported the article data in an Excel table in order to justify clearly the selection or exclusion of an article for the other reviewers. Data collected were author, title, year of publication, research country, aim of the research, method, population, and main results. In addition, when the data were clarified, reviewers noted the prevalence of PTSD in the population and the PTSD symptoms, as well as factors of vulnerability, protective factors, and psychological mechanisms for supporting HCW with trauma. Outcomes from the search terms and screening were summarized using a PRISMA flow-diagram (Fig. 1). As this was a scoping review, no formal quality analysis or summary statistics were undertaken.

Results

A narrative review of studies focusing on PTSD in ICU HCW for adult patients led to the identification of 914 potentially relevant articles (of which three studies were identified manually and added as additional references) (Fig. 1). After removing duplicates and screened for correspondence with language and format/period criteria (n = 824), the abstracts of 90 articles were reviewed. A total of five articles were eliminated from the outset, either because they did not relate to an adult population (n = 3), they focused on the validity of a screening tool for trauma (n = 1), or they involved the sharing of feedback (n = 1). Of the remaining 85 articles, 25 were not specific to ICU professionals (e.g., frontline healthcare professionals involving all medical specialties); nine did not involve ICU professionals working with adult patients; five were interested in resilience or support programs but did not access PTSD; 11 were systematic reviews or reflections, or letters to the editor from authors on the topic; 14 focused on the evaluation of acute stress or peritraumatic dissociation that had occurred within a month of the event, or analyzed a disorder other than PTSD (e.g., burnout, anxiety, depression); and two articles were inaccessible.

Overall, 19 studies were included in this narrative review. These mainly concern: nurses and assistant nurses (n = 10); nurses and physicians (n = 8); or physicians only (n = 1). They were principally conducted during the Covid-19 period (n = 12), in France (n = 3), in Canada (n = 2), in the Netherlands (n = 1), in Italy (n = 2), in the United Kingdom (n = 1), in the United States (n = 2), and in Belgium (n = 1). Only seven studies conducted before the Covid-19 pandemic were included; these were conducted in South Korea (n = 1), the Czech Republic (n = 1), the United Kingdom (n = 1), the United States (n = 3), and Australia (n = 1) (Table 1).

High prevalence of PTSD evaluated among ICU professionals in the wake of the Covid-19 health crisis

Our literature review of PTSD in ICU professionals working with an adult population over the 10 years preceding the pandemic (2009–2019), as well as during the pandemic (2020–2022), shows a renewed interest in the question of PTSD in healthcare professionals. Indeed, while our analysis over a 10 year period revealed seven studies before the crisis, 12 studies were undertaken during the Covid-19 period. The increase in the number of studies goes hand in hand with an increased risk of PTSD during this pandemic period. Indeed, studies conducted before the Covid period show the prevalence of PTSD in ICU professionals ranging from 3.3% [8] to almost 24% [9]. During the Covid period, 16% [10] to 73.3% [11] of professionals have mild to severe PTSD. While all socio-professional categories are affected [12,13,14,15], nurses are the most vulnerable to PTSD [12,13,14,15,16,17]. Finally, the IES-R [18] seems to be the measure used most often to assess PTSD in ICU professionals. This is a scale based on the DSM-V criteria [4] with three major dimensions: intrusion, avoidance, and neurovegetative symptoms.

The characteristics of PTSD in ICU healthcare professionals and risk factors

Regarding the symptomatology of PTSD in ICU professionals, intrusion symptoms appeared to be one of the most significant disorders [14]. Studies show that healthcare professionals in intensive care are confronted with risk factors for PTSD, the most important of which are related to death (death of patients, end-of-life, organ removal) [8, 19]. During the Covid crisis, the experiences of confronting death and seriously ill patients were intensified by the violence and duration of the crisis [20]. In this sense, new factors emerged that were associated with the unpredictability and uncertainty of healthcare, and with the insecurity linked to the risk of being contaminated, or of contaminating one’s family, with Covid-19, thus affecting HCW professionally and personally [11, 12, 14, 15, 17, 20, 21].

Protective factors and support systems recommended in the studies identified

Few healthcare professionals took advantage of the psychological supports available during the crisis, such as hotlines [10, 15, 22]. Laurent and her colleagues [15] noted that professionals turned primarily to more local forms of support, such as relatives, colleagues, the hierarchy, and ICU psychologists. It appears that the development of strategies based on positive thinking within ICUs had a protective effect against PTSD [15].

All the studies analyzed emphasized the importance of clear and smooth communication during a crisis in order to limit—as far as possible—feelings of fear and helplessness [11, 21]. Moreover, feeling as if one were safe in one’s own department, one had one’s team’s support, and also had sufficient material and human resources, seemed to be protective factors against PTSD [16, 21].

Discussion

Our literature review shows that it seems essential to pay particular attention to the risk of trauma in intensive care teams. Indeed, following the crisis, the prevalence of PTSD has increased to 73.3% among intensive care professionals. More than 1 year after the COVID crisis began, the prevalence of the disorder remains high (13, 7% [23] and 37% [24]). This prevalence of PTSD among ICU caregivers appears in the majority of studies in our review to exceed the prevalence of the population of health professionals, all specialties combined during the COVID crisis [25] and of the general population, which, outside the COVID period, is 8.3% over a lifetime in US [26], and more specifically in France in 2008 at 0.7% with an almost equal frequency between men and women [27].

We need to understand the traumatic risk, and in particular intrusion symptom, in the ICU in relation to the work context of the professionals. Firstly, experiencing a traumatic event in the context of work does not facilitate either the possibility of psychological reconstruction or the reduction of symptoms. Indeed, it should notice that HCW continued to work in the same environment that had caused the trauma and therefore could be impacted again, at any time, by an event that could rekindle the traumatic situation previously experienced within the service (e.g., same pathology, same room, same team). Traumatic events could be stored in one’s memory for a long time and thus be more likely to generate strong emotional reactions when HCW are faced with a similar situation [28].

The importance of PTSD in the intensive care population also leads us to question the link with other psychological difficulties highlighted in this population, notably burnout [29]. The literature highlights the link between PTSD and burnout [30], particularly during the health crisis which led to deteriorated working conditions and loss of confidence in an institution and a healthcare system that have been unable, or hardly able, to protect their workers [31]. This context makes professionals even more vulnerable, as shown in the Italian study by Lasalvia et al. [14], during the Covid period, professionals who had experienced a traumatic event at work related to Covid-19, more frequently obtained scores above the cut-off point on the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). Both at the beginning of the pandemic and two months after the crisis, studies show that the higher the level of burnout, the more severe the post-traumatic stress symptoms [32, 33]. Therefore, according to Lui et al., any initiative that helps to alleviate burnout may be useful in preventing the severity of PTSD [33].

We would like to draw attention to the fact that the results of our narrative review should also be discussed with regard to the methodology on which the identified studies are based. While the DSM-V criteria [4] relate to the international level, there is nevertheless some nosographic confusion within the studies between—on the one hand—what may be described as acute stress in the month following the event and—on the other hand—PTSD from which the healthcare worker suffers chronically: only five studies out of 17 clearly explained the temporality of the assessment of disorders. However, as Hernandez and her colleagues [34] state in their study, to diagnose PTSD effectively, one must consider the intensity of the event, on the one hand, and—on the other—the psychotraumatic manifestations arising from. Indeed, the intensity of the event and its immediate impact are not sufficient for diagnosing PTSD, it is the long-term condition of the disorders—beyond a month—that reveals the traumatic scope of the event [4].

Finally, few studies have really investigated and evaluated the relevance of prevention or support measures. It should be noted that the inability of the HCW staff to ask for help remained a significant problem. Indeed, although the available studies highlight the suffering of HCW [10], it appears that initiating a process of help or care is still difficult for healthcare professionals [15]. This results primarily from the emergency context which is associated with time constraints, heavy workloads, ignorance of psychologists’ work [15], and a medical culture of uncomplaining healthcare professionals, [10] and which does not make this process any easier. In view of the high risk of PTSD in the intensive care population, it seems essential to develop more interventional studies to measure the relevance of psychological devices within the wards. In parallel, it seems necessary to set up psycho-educational seminars for caregivers to better understand the risks of trauma, as this is a first step to enable caregivers to better identify risk situations and their consequences on their mental health [35]

This study has several limitations. Some studies may have been overlooked if their article titles, keywords, or abstracts did not clearly reflect the objective of identifying PTSD in ICU healthcare professionals. In addition, studies developed at a more local level may have been excluded from our review. Given that meta-analysis was not feasible or appropriate because of the nature and design of the studies, a narrative approach was used to summarize the data, as recommended for scoping reviews. Lastly, the Covid-19 health crisis is recent and it is still difficult to account for the real traumatic impact of this crisis on healthcare professionals over time.

Conclusion

ICU professionals are exposed to traumatic situations that can have a long-term impact and it is essential today to set up prevention and psychological support measures for this population. Studies on measures to help professionals to cope with trauma are rare. These are also contradictory because, while they advocate easier access to psychological care for ICU professionals and the active participation of these professionals and the hospital system, they underscore how difficult it is for professionals to ask for help, and for the hospital system to find resources to provide appropriate care [36].

The health crisis seamlessly transitioned from an acute and exceptional phase to a chronic phase taking the form of a normality at work [15]. The risk is to have transformed the ICU into a space of repetitive trauma without the professionals having been able to debrief them.

Availability of data and materials

No concerned.

References

Ferrand E, Robert R, Ingrand P, Lemaire F. Withholding and withdrawal of life support in intensive-care units in France: a prospective survey. Lancet. 2001;357:9–14.

Chen Q, Liang M, Li Y, Guo J, Fei D, Wang L, et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e15–6.

Robert R, Kentish-Barnes N, Boyer A, Laurent A, Azoulay E, Reignier J. Ethical dilemmas due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10:84.

Association American Psychiatric. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition: DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

Cunningham KC. Shame and guilt in PTSD emotion in posttraumatic stress disorder. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2020.

Baumeister RF. Writing a literature review. In: Prinstein MJ, editor. The portable mentor. New York: Springer; 2013.

Siddaway AP, Wood AM, Hedges LV. How to Do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annu Rev Psychol. 2019;70:747–70.

Janda R, Jandová E. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression among Czech critical care and general surgical and medical ward nurses. J Res Nurs. 2015;20:298–309.

McMeekin DE, Hickman RL, Douglas SL, Kelley CG. Stress and coping of critical care nurses after unsuccessful cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Am J Crit Care. 2017;26:128–35.

Altmayer V, Weiss N, Cao A, Marois C, Demeret S, Rohaut B, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 crisis in Paris: a differential psychological impact between regular intensive care unit staff members and reinforcement workers. Aust Crit Care. 2021;34:142–5.

Crowe S, Howard AF, Vanderspank-Wright B, Gillis P, McLeod F, Penner C, et al. The effect of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian critical care nurses providing patient care during the early phase pandemic: a mixed method study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2021;63:102999.

Caillet A, Coste C, Sanchez R, Allaouchiche B. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on ICU caregivers. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2020;39:717–22.

Greenberg N, Weston D, Hall C, Caulfield T, Williamson V, Fong K. Mental health of staff working in intensive care during Covid-19. Occup Med. 2021;71:62–7.

Lasalvia A, Bonetto C, Porru S, Carta A, Tardivo S, Bovo C, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in a highly burdened area of north-east Italy. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2021;30:e1.

Laurent A, Fournier A, Lheureux F, Poujol A-L, Deltour V, Ecarnot F, et al. Risk and protective factors for the possible development of post-traumatic stress disorder among intensive care professionals in France during the first peak of the COVID-19 epidemic. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2022;13:2011603.

Carmassi C, Dell’Oste V, Bui E, Foghi C, Bertelloni CA, Atti AR, et al. The interplay between acute post-traumatic stress, depressive and anxiety symptoms on healthcare workers functioning during the COVID-19 emergency: a multicenter study comparing regions with increasing pandemic incidence. J Affect Disord. 2022;298:209–16.

Mehta S, Yarnell C, Shah S, Dodek P, Parsons-Leigh J, Maunder R, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on intensive care unit workers: a nationwide survey. Can J Anesth. 2022;69:472–84.

Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the impact of event scale—revised. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:1489–96.

Mealer M, Burnham EL, Goode CJ, Rothbaum B, Moss M. The prevalence and impact of post traumatic stress disorder and burnout syndrome in nurses. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:1118–26.

Foli KJ, Forster A, Cheng C, Zhang L, Chiu Y. Voices from the COVID-19 frontline: nurses’ trauma and coping. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77:3853–66.

Heesakkers H, Zegers M, van Mol MMC, van den Boogaard M. The impact of the first COVID-19 surge on the mental well-being of ICU nurses: a nationwide survey study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2021;65:103034.

Loiseau M, Ecarnot F, Meunier-Beillard N, Laurent A, Fournier A, François-Purssell I, et al. Mental health support for hospital staff during the COVID-19 pandemic: characteristics of the services and feedback from the providers. Healthcare. 2022;10:1337.

Pan L, Xu Q, Kuang X, Zhang X, Fang F, Gui L, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with post-traumatic stress disorder in healthcare workers exposed to COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:572.

Carola V, Vincenzo C, Morale C, Cecchi V, Rocco M, Nicolais G. Psychological health in intensive care unit health care workers after the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare. 2022;10:2201.

Cénat JM, Blais-Rochette C, Kokou-Kpolou CK, Noorishad P-G, Mukunzi JN, McIntee S-E, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295:113599.

Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, Miller MW, Keyes KM, Friedman MJ. National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria: DSM-5 PTSD prevalence. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26:537–47.

Vaiva G, Jehel L, Cottencin O, Ducrocq F, Duchet C, Omnes C, et al. Prévalence des troubles psychotraumatiques en France métropolitaine. L’Encéphale. 2008;34:577–83.

Dennis D, Van Vernon Heerden P, Knott C, Khanna R. The nature and sources of the emotional distress felt by intensivists and the burdens that are carried: a qualitative study. Aust Crit Care. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2021.11.006.

Papazian L, Hraiech S, Loundou A, Herridge MS, Boyer L. High-level burnout in physicians and nurses working in adult ICUs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2023;49:387–400.

Restauri N, Sheridan AD. Burnout and posttraumatic stress disorder in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: intersection, impact, and interventions. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17:921–6.

Haliday H, Bonnet M, Poujol A-L, Masselin-Dubois A, Deltour V, Nguyen S, Fournier A, Laurent A, Les dispositifs groupaux à l’hôpital et en EHPAD durant la crise de la Covid-19 Quelles demandes, quelles offres, quels apports ? Prat Psychol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prps.2022.02.003.

Johnson SU, Ebrahimi OV, Hoffart A. PTSD symptoms among health workers and public service providers during the COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0241032.

Liu Y, Zou L, Yan S, Zhang P, Zhang J, Wen J, et al. Burnout and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among medical staff two years after the COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan, China: social support and resilience as mediators. J Affect Disord. 2023;321:126–33.

Hernandez JM, Munyan K, Kennedy E, Kennedy P, Shakoor K, Wisser J. Traumatic stress among frontline American nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey study. Traumatology. 2021;27:413–8.

Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA. Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. Lancet. 2009;374:1714–21.

Rangachari P, L. Woods J. Preserving organizational resilience, patient safety, and staff retention during COVID-19 requires a holistic consideration of the psychological safety of healthcare workers. IJERPH. 2020;17:4267.

Cho G-J, Kang J. Type D personality and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among intensive care unit nurses: the mediating effect of resilience. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0175067. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175067.

Colville GA, Smith JG, Brierley J, et al. Coping with staff burnout and work-related posttraumatic stress in intensive care. Pediatric Crit Care Med. 2017;18:e267–73. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000001179.

Mealer M, Conrad D, Evans J, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a resilience training program for intensive care unit nurses. Am J Crit Care. 2014;23:e97–105. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2014747.

Van Steenkiste E, Schoofs J, Gilis S, Messiaen P. Mental health impact of COVID-19 in frontline healthcare workers in a Belgian tertiary care hospital: a prospective longitudinal study. Acta Clin Belg. 2022;77:533–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/17843286.2021.1903660.

Acknowledgements

The support of School of Practitioner Psychologists, Catholic University of Paris, EA 740. Thanks to the Fondation de France for their support.

Funding

No concerned.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VD: data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing—original draft. ALP: data curation, formal analysis, methodology, supervision, writing—review. AL: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, supervision, validation, writing—review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No concerned.

Consent for publication

Yes.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Deltour, V., Poujol, AL. & Laurent, A. Post-traumatic stress disorder among ICU healthcare professionals before and after the Covid-19 health crisis: a narrative review. Ann. Intensive Care 13, 66 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-023-01145-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-023-01145-6