Abstract

Through an analysis of interviews with Southern California attorneys, supplemented by archival materials, this article contributes to the literature on gangs, critical criminology, and Gothic tropes by examining how the ambiguous nature of gang profiling allows state actors to target racialized others in various legal and administrative venues with little evidence and few procedural protections. I conceptualize gang phantasmagoria as the constant, amorphous, unpredictable, and haunting threat of racialized gang allegations and argue that the dynamic shapes the work of legal practitioners and constitutes a state mechanism of racial terror. Specifically, first I argue that government officials deploy the specter of gangs to both portray asylum seekers as monstrous threats and justify restrictions in asylum eligibility. I then illustrate how the potential for gang phantasmagoria to upend asylum applications and trigger the deportation of their clients elicits constant low-grade anxiety for attorneys. Consequently, attorneys are forced to adopt more cautious approaches to legal work in a way that indirectly facilitates the social control of young Latinx immigrants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There are two sisters with a two-year age gap between them; we will call them Aileen and Alexandra. The teenagers, who were born in Central America, are seeking refuge in Southern California. Their pro-bono immigration attorney, Manuel, walks them into a dreary United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) field office for an interview during which an Asylum Officer will assess Aileen’s asylum claim. Manuel has asked for both sisters to be present during their respective asylum interviews so that the cases can support one other. What neither Manuel nor the two sisters realize is that during this interview, they will be blindsided with an extensive gang-related interrogation. For nearly an hour, the Officer will cross-examine Aileen about gang members in her family, her home country, her neighborhood and school in the US, and more. Shortly thereafter, word of the enhanced gang interrogation will ripple through networks of attorneys, sparking apprehension and altering the way legal practitioners approach their work.

Pulling on interviews with immigration attorneys in Los Angeles, supplemented by archival analysis, I examine the implications for legal practice wrought by recent shifts in gang profiling in the asylum process. Scholars have previously critiqued gang profiling practices by local police (Bloch and Meyer 2019; Contreras 2013; Durán 2009; Muñiz 2015; Ralph 2014; Stuart 2020), federal law enforcement (Barak, León, and Maguire 2020; Chacón 2007), school personnel (Lam 2012; Rios 2017), corrections officers (Bloch and Olivares-Pelayo 2021; Lopez-Aguado 2018), immigration detention personnel (Noferi and Koulish 2014), and media outlets (Hallsworth and Young 2008) as incoherent and based on racial stereotyping. I build on this work as well as literature on phantasmagoria and Gothic criminology (Fiddler 2011; Picart and Greek 2007; Rafter and Ystehede 2010; Skott, Nyhlén, and Giritli‑Nygren 2020; Sothcott 2016; Valier 2002) to argue that gang profiling assumes a phantasmagoric quality that terrorizes Latinx immigrant youth and their attorneys.

Specifically, I argue that because an exact definition of “gang member” remains elusive, racialized, and outside of the confines of due process, gang allegations are haunting; their potential to upend applications for immigration status changes and trigger deportations elicits consistent low-grade anxiety for attorneys. Furthermore, the occasional materialization of these fears, in asylum interviews for example, encourages attorneys to adopt a more cautious approach to legal work and indirectly enhances the social control of young Latinx immigrants.

This article proceeds in five parts. First, I review literature on racialized gang profiling and phantasmagoria. In the second section, I describe my methods. Third, I analyze how political and law enforcement actors performatively construct the racialized gang specter for the purposes of restricting asylum eligibility. In the fourth section, I examine the effects of gang phantasmagoria—defined as the constant, amorphous, unpredictable, and haunting threat of racialized gang allegations—on the daily work of attorneys. Then, through the exemplary case of Aileen, Alexandra, and Manuel, I illustrate how gang allegations, heretofore haunting the background of legal work, explode into the foreground with lasting effects. Lastly, I discuss the broader implications of gang phantasmagoria for legal practice and racialized social control.

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Racialized Gang Profiling

There are several ways in which an individual can come to be categorized as a gang member or associate. Allegations do not require an arrest, charge, or conviction. Rather, people are documented as gang members primarily through discretionary assessments by law enforcement or correctional officers (Conway 2017). On the street, local police officers document alleged gang members and associates on Field Interview cards, recording intelligence information that is often unrelated to criminal actions (Brayne 2020). Staff in juvenile detention facilities, prisons, jails, and immigration detention also assess confined people for gang membership to determine security group status (Goodman 2008; Lopez-Aguado 2018; Noferi and Koulish 2014). Stefano Bloch and Enrique Alan Olivares-Pelayo (2021), for example, reveal how incarcerated individuals negotiate their racial—and racialized gang—identifications with intake officers in the correctional setting. Gang allegations also make their way to law enforcement from social workers, school personnel, and health services providers (Garcia-Leys and Brown 2019; Marston 2019).

Scholars have long bemoaned the “definitional shortcomings” endemic to determinations of gang membership (Esbebsen, Winfree, Jr., He, and Taylor 2001:105), which are often based on broadly construed, subjective criteria including clothing, tattoos, social networks, and geographic location (Bloch and Meyer 2019; Durán 2009; Durán and Campos 2019; Muñiz 2015; Rios 2017). Over-labeling and mislabeling is common (Garcia-Leys, Thompson, and Richardson 2016; Marston 2019). Gang profiling is so notoriously inconsistent that even a foundational agreement as to what constitutes a gang and gang violence has proven to be elusive (Huff and Barrows 2015; Maxson 1999; Maxson and Klein 1996; Miller 1975).

Gang profiling is highly racialized. The overwhelming majority of people in gang databases are Black and Latinx. Scholars have argued that media outlets and politicians deploy rhetoric around gangs to criminalize youth of color (Bloch 2019; Muñiz 2015) and that law enforcement apply the label to any group of youth whose behaviors “run counter to the puritanical logic and values of police” (Linnemann and McClanahan 2017:308) or elicit “bourgeois disapproval” (Ball and Curry 1995:227).

On both the local and federal levels, gang enforcement efforts target racial minority groups while overlooking other dangerous groups with similar characteristics such as white supremacist groups or law enforcement gangs (Reid and Valasik 2020). Nativist political commentators, policymakers, and immigration authorities use the image of the Latino gang member to associate immigrants with danger and to justify restrictionist immigration policies (Barak et al. 2020; Carter 2019).

Because law enforcement can classify an individual as a gang member or associate based on visual cues, like tattoos and dress, an alleged gang member may be unaware they have been categorized as such. Law enforcement has rarely been required to notify people of the allegation, instead classifying the information as “investigative” and confidential (Aba-Onu, Levy-Pounds, Salmen, and Tyner 2010:230). Lack of notification—and therefore, lack of an opportunity to contest the categorization—is problematic because gang allegations can result in increased bail and enhanced sentencing in the criminal justice system, police scrutiny on the street, denial of employment, restricted educational access, expedited deportation, denial of immigration benefits, and denial of affirmative status changes or relief, including asylum (Barak et al. 2020; Garcia-Leys, Thompson, and Richardson 2016; Howell 2019; Stuart 2020; Walker and Cesar 2020). Gang allegations are easy to apply, requiring low criteria thresholds and little in the way of due process, and enable enhanced punishment.

The amorphousness of gang criteria has created uncertainty regarding who law enforcement does or does not consider to be gang involved. Ball and Curry (1995:227) note that gangs and gang members are largely defined by what they are not—not white and not within the boundaries of respectable bourgeois behavior. Attempting to pin down what gangs are, what exactly constitutes a gang member, is akin to capturing the “correct description of a ghost” (Katz and Jackson-Jacobs 2004:106).

Phantasmagoria

Eighteenth century phantasmagorists performed light shows in which they manipulated optics to create the appearance of hallucinatory terrors. The projections were produced by a “magic lantern,” an antecedent to the contemporary slide projector, hidden from audience view (Fiddler 2011:89). The phantasms were “animated and mobile,” grew rapidly, transformed into dreadful shapes, and “seemed to surge towards the terrified spectators” (Mannoni and Brewster 1996:390). Contemporary scholars have invoked the concept of phantasmagoria to examine diversity management practices (Schwabenland and Tomlinson 2015), the birth of cinema (Gunning 2004), digital democracy (Marden 2014), neoliberalism (Jessop 2014), prisons (Fiddler 2011), and racial othering (Johnson 2001). Because scholars have employed the concept in various ways, in this section I define the three phantasmagorical characteristics that I use to examine the practice of gang labeling.

First, the spectacle of phantasmagoria is characterized by the projection of something illusory; the image represents an artifice that conceals a deeper reality. Christian De Cock, Max Baker, and Christina Volkmann (2011) deconstruct the phantasmagorical image work through which marketing departments portray financial institutions as immortal, reliable, and caring. The authors argue that behind the glossy images lie financial institutions marked by cold calculation, misplaced confidence, and incompetence. Thus, positioning a social phenomenon as phantasmagoria indicates that there is performativity at the core, something to be exposed through deeper analysis (Schwabenland and Tomlinson 2015; Fiddler 2011).

Second, while De Cock, Baker, and Volkmann (2011) examine the comforting illusions of phantasmagorical financial imaginary, the phantasmagorical image is more often one of monstrousness (Skott, Nyhlén, and Giritli‑Nygren 2020). For example, postcolonial artist and writer Diego Ramirez (2018) argues that artist Richard Mosse’s use of surveillance imagery constitutes “racial phantasmagoria” in portraying immigrants as dark-skinned invaders of Western nation-states. Gothic images are often a projection of anxieties about material insecurity, cultural miscegenation, porous racial boundaries, and compromised geographical borders (Johnson 2001; Sothcott 2016; Valier 2002). The “invocation of horrors” (Valier 2002:320) through Gothic tropes are both imbedded in and constitute a justification for punitive institutions (Rafter and Ystehede 2010; Skott, Nyhlén, and Giritli‑Nygren 2020; Sothcott 2016). These tropes include the construction of asylum seekers as a faceless, violent mass of shadowy figures who threaten national security (Valier 2002), illustrated by former president Donald Trump’s assertions regarding unaccompanied minors: “They exploited the loopholes in our laws to enter the country as unaccompanied minors. They look so innocent. They’re not innocent” (Kim 2018). Meanwhile, to defend the policy of child separation at the border, Kirstjen Nielsen, Trump’s Secretary of Homeland Security, explicitly conjured the gang phantasm, claiming, “The kids are being used as pawns by the smugglers and the traffickers […] Those are traffickers, those are smugglers and that is MS-13, those are criminals, those are abusers” (The New York Times 2018).

Third, because the projection is an ambiguous illusion, it elicits anxiety and fear. For example, in examining diversity management practices through the metaphor of phantasmagoria, Christina Schwabenland and Frances Tomlinson (2015) find “diversity” to be an ill-defined concept. Organizational personnel in charge of diversity management are consequently “located in a liminal space, between reality and illusion, with few fixed points of reference” (Schwabenland and Tomlinson 2015:1930), afraid of doing diversity management wrong or using inappropriate terms. This positionality causes anxiety and paralysis among diversity practitioners.

The concept of phantasmagoria offers an effective heuristic through which to examine gang profiling, specifically to interrogate how “difference, rather than simply being excluded or marginalized, is being staged or simulated” (Gordon 2008:16). Criminologists and social scientist have long argued that criminality or deviance is not located but rather, constructed (Becker 1963; Goffman 1963). Law enforcement and political leaders do not simply find alleged gang members in nature but rather, through a political practice of categorization, construct certain people as such. Simon Hallsworth and Tara Young (2008:184, 188) thus note that far from being a neutral description, the “gang” is “a blinding and mesmerizing concept,” “a sort of simulacra, a reification, an identical copy of a reality that may not exist,” and “a monstrous Other, an organized counter force confronting the good society.” Like other Gothic figures metaphorically associated with racialized threat, such as the vampire (Sothcott 2016), barbarian (Picart and Greek 2007), or Zombie (Linneman, Wall, and Green 2014), gang members act as “an invisible symbol” onto which anxiety and prejudices can be projected (Fraser and Atkinson 2014:156) and an “empty signifier around which contingent relations of subjectivity, power and space—that is, social order—are produced” (Meyer 2021:273).

A strong collection of literature examines how the Gothic vilification of groups, often in the form of moral panics (Cohen 1972), functions to justify their exclusion (Tosh 2019) and annihilation (Skott, Nyhlén, and Giritli‑Nygren 2020); allows for Durkheimian public vengeance that reaffirms shared social values (Sothcott 2016; Valier 2002); or enables populist political objectives through “racially divisive appeals” (Brown 2016:315). Building on this literature, I first briefly address the use of gang phantasmagoria to elicit fear in the public and to justify punitive immigration policies. I then shift to make a contribution regarding a less explored dynamic—gang phantasmagoria’s destabilizing effects on legal practitioners. I demonstrate that even before the “gang member” classification has been applied, and even if it is never applied, it acts as a sort of roaming spectral entity and constant threat that shapes legal work. For these purposes, I define gang phantasmagoria as the constant, amorphous, unpredictable, and haunting threat of racialized gang allegations. I argue that gang phantasmagoria affects the daily realities faced by legal practitioners and concretely alters their approaches to legal work. As I address in the “Discussion and Conclusion” section, the ability of law enforcement and other administrative authorities, such as immigration services, to deploy gang phantasmagoria holds broader implications for racialized social control.

Methods

The data analyzed in this article constitute a portion of a larger project that pulls on ethnographic observation, archival analysis, interviews, and quantitative analysis to examine how people come to be categorized as gang-involved and the consequences for immigration outcomes. For the portion of the project described in this article, between August 2016 and May 2018, I conducted semi-structured interviews with 19 attorneys at eight nonprofit agencies in the Los Angeles region who practice at the intersections of criminal, juvenile, and immigrant defense work, specifically with clients accused of gang affiliation.

Because defending gang allegations in immigration court requires some level of specialized knowledge of criminal law, civil law, and the mechanisms by which people come to be categorized as gang members (i.e., Field Interview cards and gang databases), there were only one to two attorneys at each nonprofit who actively sought out or were regularly assigned gang cases. Although they accepted the gang cases on which others passed, overall the attorneys in this study proportionately did mostly non-gang cases, thus bringing perspective on immigration cases that ultimately both did and did not involve gang allegations. The network of attorneys who do this work is tight-knit, meaning that I reached saturation relatively quickly, as attorneys began to refer me to other attorneys whom I already interviewed.

With the interviews, I conducted a first round of inductive open-coding by hand to develop coding categories (Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw 2011; Timmermans and Tavory 2012). I then used the themes that emerged from the first round of coding to conduct more directed coding. I wrote analytical memos in which I sorted data excerpts and integrated themes drawn inductively from the data set with theory from relevant literature. Although I did not ask attorneys specifically about their feelings in defending gang allegations, it is a theme that emerged organically across the interviews. It became clear that attorneys not only focused on legal strategy, but that the daily topography of legal work was marked by apprehension about possible gang allegations.

During the time I conducted interviews, attorneys began to experience enhanced gang interrogations during asylum interviews. I asked the attorneys to document the questions that Asylum Officers asked their clients in asylum interviews and collected their lists after several weeks for analysis. The various lists of gang-related questions were remarkably consistent with one another. Furthermore, during the same time, the Immigrant Legal Resource Center (ILRC) conducted a nationwide survey of immigration attorneys in which respondents reported the same practice of enhanced gang questioning in asylum interviews. Although I chose to limit interviews to Los Angeles attorneys to control for differences in regional USCIS offices, the affinity of my findings with the ILRC report suggests that the new practice is likely a nation-wide directive. Expanding this study nationwide would therefore represent a promising direction for future research.

Additionally, I searched the Federal Register for all Executive Orders issued between January 20, 2017 and January 20, 2021 and identified 16 (of 219 total) as relevant to either gangs, immigration, or asylum. With the 16 Executive Orders, I documented structural changes, as the immigration system is largely altered by administrative, rather than legislative, actions. Lastly, I searched the whitehouse.gov website for speeches and press conferences made by Donald Trump during his presidency (130 documents). I analyzed the speeches and remarks for portrayals of gangs or immigration. Although I refer to these documents with less frequency than other data, they provided policy context and illuminated the construction of gang phantasmagoria through rhetoric.

Background

Political Phantasmagorists: Conjuring the Gang Specter in Asylum Seekers

I been [sic] in the detention facilities where I’ve walked up to these individuals that are so called minors, 17 or under, and I’ve looked at them and I’ve looked at their eyes, Tucker, and I said that is a soon-to-be MS-13 gang member. It’s unequivocal.

Mark Morgan, then-acting director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), made the preceding statement to Tucker Carlson during a 2019 interview, summoning the nightmarish imagery of Brown children with threatening stares (Hesson 2019). I’ve looked at their eyes. His rhetoric was consistent with that of the Trump administration who projected, through a rhetorical magic lantern, horrifying images of dark young men with tattooed faces crossing into the US. Trump and then-Attorney General Bill Barr insisted that alleged gang members “aren’t people,” but rather, “vile and evil,” “savage,” “monsters,” and “animals” who “murder children and they do it as slowly and viciously as possible” (Associated Press 2020). It is important to note that while the Trump administration escalated attacks on immigrants and gangs, Democratic administrations also separate ‘deserving’ immigrants deemed worthy of US citizenship from ‘undeserving’ immigrants like alleged gang members (Tosh 2019).

The Trump administration argued that asylum loopholes allow alleged gang members to legally remain in the US (Wamsley 2019). Consequently, the administration justified heightened federal gang enforcement, border militarization, and limits on asylum eligibility, particularly for youth from Mexico and Central America, by portraying them as the new foot soldiers for gangs in the US. Directives from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), ICE, the White House, and the Department of Justice identified gang membership as a priority for enforcement and a point of compulsory exclusion from immigration benefits and relief programs (Kim 2018; Trump 2017a, b, 2018; US Attorney’s Office 2017). This was the political context that framed Manuel, Aileen, and Alexandra’s asylum interview in the late summer of 2017.

The loopholes to which Trump referred are actually legal protections for people who have suffered from or fear persecution in their home countries. Migrants must file for asylum within one year of last entry to the US and bear the burden to prove their eligibility. Individuals who have been apprehended by immigration authorities and entered into removal proceedings apply for defensive asylum, an adversarial process in immigration court where a DHS attorney will argue for the asylum seeker’s deportation (Wilkinson 2010). Immigrants who are not undergoing removal proceedings may apply for affirmative asylum (Galli 2017). Manuel identified the benefits of the affirmative asylum process, particularly for young people like Aileen and Alexandra: “It’s less adversarial because you don’t have a government attorney who’s trying to get you deported. It’s just you and an Asylum Officer who doesn’t wear a uniform.”

The attorneys in this study characterized the affirmative context as marked by relatively more anticipation because there is incomplete information as to whether a client has been categorized as a gang member. By contrast, in removal, attorneys and clients can apply for any relief that might be available and “see what sticks,” as one attorney phrased it. Nonetheless, the attorneys noted that, in practice, all cases felt defensive because an unsuccessful attempt is result in deportation. In both affirmative and defensive scenarios, authorities practice political domination by subjecting subordinated groups to long periods of anticipatory limbo punctuated by moments of elevated stress (Estévez 2020).

Certain individuals are barred from asylum, including those who have participated in past persecution or are considered a danger to US security (Manuel 2014:23; Sullivan 2014). As gang affiliation fits under both of these categories, it is “nearly impossible” for allegedly active gang members or associates, or even former gang members, to attain asylum (Wilkinson 2010:396–397). The Ninth Circuit, the First Circuit, and the Board of Immigration Appeals have all determined that former gang members are excluded from asylum eligibility, with the First Circuit writing that past affiliation with a criminal organization “is inconsistent with the principles underlying the bars to asylum and withholding of removal based on criminal behavior” (Manuel 2014:20). Apart from legal restrictions, because there is high demand for asylum, Asylum Officers are unlikely to discretionarily grant refugee status to alleged gang members or former gang members (Valdivia Ramirez, Faria, and Torres 2021).

Asylum attorneys help to arrange the facts of their client’s case into a sympathetic narrative, a difficult undertaking when asylum seekers come from regions identified by the US Government as rife with gang violence, including Mexico and Central America. Attorneys must differentiate their clients from ‘undesirable’ elements in the home country within the acceptable narrative templates delineated by the state. Because asylum interviews assess both vulnerability and complicity, asylum seekers must prove they are both threatened and nonthreatening, thus positioning themselves at the top of economies of deservingness (Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas 2012). Immigration bureaucrats execute state power on the ground by requiring that asylum seekers reach (an often unreasonably high) threshold of deservingness (Bhatia 2020).

While it has been common for politicians and political commentators to portray gang violence as a foreign product that is brought to the US by immigrants, the major transnational gangs including MS-13 and 18th Street first emerged in the US, and US political and economic hegemony continues to aggravate violence in Mexico and Central America. Once exported, scholars have demonstrated how gangs were fed in the 1990s by disenfranchised Central American youth left without opportunities as a result of civil war, US-supported coups, the economic devastation of the North American Free Trade Agreement, and the spread of American-style zero tolerance policing (Zilberg 2007; Carter 2019). Consequently, many migrants from Central America who are vulnerable to gang profiling are actually fleeing violence or threats of violence by gangs in their home countries.

Chiara Galli (2020) argues that within the context of an increasingly punitive immigration system, legal intermediaries try to manage risk by comparing a current client’s circumstances to those of past cases to assess likelihood of success. However, these assessments are constrained by the nature of the immigration system wherein an Asylum Officer has the discretion to grant refugee status or refer the case to an immigration judge for the adversarial hearing. The vague, subjective, racialized practice of gang labeling collides with an immigration decision-making process that is also notably subjective, unpredictable, and opaque.

Gang Phantasmagoria in Legal Work

The Gang Specter Looming

Inside, the office is dark, in sharp contrast to the sunlight-bleached streets of downtown Los Angeles. As I step inside, it takes a few seconds for my eyes to adjust and find Sheila, an immigration attorney who works for a local nonprofit organization, sitting at her desk in a glass-walled office. Sheila has one of her clients on her mind, a Lawful Permanent Resident soon to apply for citizenship. She explains, “He may deal with the issue. We are unsure if it has become an issue yet. I’m anticipating it might become an issue because he is from Orange County, he’s young, has tattoos […]”.

“The issue,” the unspoken electrical charge around the conversation, is a gang allegation. Because accusations of gang involvement do not need to stem from convictions, arrests, or even charges, and because notification is still relatively rare, Sheila and other attorneys have to profile their own clients according to criteria they have previously observed being used by law enforcement. The attorneys in this study considered young people of color who grew up in heavily policed urban areas to be vulnerable to gang allegations, particularly if they had tattoos or if their friends or family members had been profiled. This describes huge swaths of young people and thus, does little to narrow the scope or reduce uncertainty.

It is in this way that gang allegations haunt the background of their days. When attorneys spoke about cases in which young Latin American immigrants applied for a status change or deportation relief, they described a constant undercurrent of anxiety elicited by the potential for gang allegations. James, an attorney who defends people from gang allegations in both the criminal justice and immigration systems, recently asked one of his clients to think about any way, at any point in the past, that he may have been categorized as a gang member. James reports, “He said, ‘a cop took my picture on the street as a juvenile,’ but couldn’t think of other ways he was labeled.” Nonetheless, James worries that his client may have been entered into a gang database, identified as a gang member on a Field Interview card, or categorized by some other institution.

Even when there was no obvious evidence of a client’s gang involvement and no official indicators that they had been categorized, attorneys were nonetheless haunted by possible allegations. Attorneys thus become attentive to a hidden “shadow realm of perpetual risk and danger” that is both everywhere and nowhere (Sothcott 2016:440). For example, James worried that when local police in the US stopped and questioned, but did not formally arrest, another client, they may have still documented him as a gang member, information that would appear on a background check later. James explained,

He was with his kids in a park and they [police] started to ask to see his tattoos. He asked if they would not do it around his kids, so they took him around the bathroom in the park where they couldn’t see it. They even started fingering through his hair to see if he had any tattoos on scalp. It’s things like that that let them know.

The man James is discussing was not arrested but the search conducted by local police, particularly with its emphasis on tattoos, “let [him] know” that police suspected him of gang involvement.

At other times, attorneys fully expect that certain clients will be gang-labeled, only to have them go through an immigration process without issue. Sheila described the months-long bouts of apprehension she has felt over possible gang allegations that ultimately never materialize: “There’s been times where we freak out thinking it’s going to be an issue, and it goes through without a problem.” The gang allegations that are expected but never arrive are a relief in the moment. However, they ultimately reinforce the overall feeling of unpredictability that fuels low-grade anxiety. Next, we will return to Manuel, Aileen, and Alexandra to explore a moment in which the vague specter of gang allegations materializes into terrifying corporeality.

The Gang Specter Materializes

In the late summer of 2017, Manuel was negotiating both the oncoming heatwave and the barrage of punitive immigration policies released by the Trump administration through executive order. Despite the escalating tensions, Aileen’s interview began predictably enough; the Asylum Officer asked the standard questions related to group persecution including, “Have you ever participated in or abetted the persecution of any person on account of their race, religion, nationality, or membership in a particular social group?” As gangs fit under the umbrella of groups who engage in the harm and persecution of others, these types of questions are implicitly about gang activity. Aileen answered in the negative, and in response, the Asylum Officer inquired as to whether she knew anyone who had participated in the harm or persecution of others. Aileen revealed that her brother had been involved in a gang in her home country, a fact that Manuel and the two sisters had discussed and which Aileen was prepared to explain.

Aileen and Manuel, however, were not prepared for what came next. The Asylum Officer abruptly announced that she was going to shift to a series of questions about gang involvement. It began with direct questions about the applicant and the applicant’s family, friends, and acquaintances: “Have you even been in a gang?” “Has anyone in your family been in a gang?” “Do you have any friends who have been in a gang?” This line of inquiry is still within the realm of a normal asylum interview. Next, the officer moved onto more general questions about Aileen’s experience with gangs in her school, neighborhood, household, and city: “Were there gangs in your school in your home country?” “Do you know who the leader of the gang in your town was?” “Have you ever seen gangs in your school or neighborhood in the US?” “Did anyone you know from school grow up to join a gang?” These questions surprised Manuel because of their broad nature.

The Officer transitioned to another group of questions, ones that assessed whether Aileen or her family had provided assistance or material support to a gang: “Did your father have to pay renta?”Footnote 1 “Did you ever give support to a gang, even if you did not want to?” “Did you do any favors or run errands for a gang member, even if you did not want to?” Aileen is being positioned as a facilitator of gangs, either willing or coerced, but a facilitator nonetheless. The differentiation of victim from perpetrator can be difficult in spaces where gangs are a fact of social life, and it is in this blurry middle ground that gang phantasmagoria arises. For example, immigration officials may allege that being a victim of gang violence itself indicates gang membership under the rationale that the violence was a result of rival gang warfare (Hlass and Prandini 2018).

Manuel explained his trepidation, yet helplessness, at the line of questioning:

It was not just, is the person applying for asylum a gang member? It’s also, do they have any important information about gangs? She started asking general questions about gangs in their neighborhood, gangs in their city, and gangs at their school. Had they seen any gangs on the way to school? […] I was starting to get frustrated actually because I think it took about 45 min, this whole gang questioning so that extended the interview a lot and it tired my clients. I was not prepared for the extended gang questioning. The attorney role, when it comes to USCIS, is supposed to be silent until the end when you are given an opportunity to talk […] You have to walk fine line because you don’t want to alienate or antagonize the officer.

A nationwide survey of immigration attorneys by the Immigrant Legal Resource Center (ILRC) (Hlass and Prandini 2018:18) also uncovered expanded gang questioning by USCIS adjudicators starting in late 2017. Like the lists of gang questions provided by the attorneys in this study, the questions attained by the ILRC are broad and some of them can only be answered with numerical estimations or affirmations that gangs exist within proximity of the applicant. For example, an attorney in this study reported that when their client was unsure about the number of gang members in their town, the Asylum Officer encouraged her to roughly guess.

In Aileen’s case, more than an hour after they began, the questions about gangs just ended. Without a smooth transition, the Asylum Officer switched back to the usual interview script. Here, the destabilizing effect of gang phantasmagoria is accomplished as much through the form as with the substance of the questioning. The gang tangent appears and concludes with equal abruptness in a gas-lighting whirlwind that leaves asylum seekers and their attorneys wondering what just happened while the Officer proceeds as if nothing is out of the ordinary. As suddenly as it had materialized, the specter retreats, but not without consequence.

The Aftermath

Across the city, Sandra, an attorney who works primarily with juveniles, was reeling from a similar turn in an asylum interview but with a client who, unlike Aileen, had no family history of gang involvement. She explained, “It used to be that we would expect a gang allegation if father or brother were involved. Now if they’re from Honduras, El Salvador, or Guatemala, it’s a standard part of screening to ask about gang involvement.” Other attorneys similarly reported that even their clients who had no history of gang involvement or association were subject to an extended list of gang questions “out of nowhere” starting in the late summer and early fall of 2017.

The unexpected and sudden escalation in questions about gang involvement represents the materialization of anxiety that normally underlies the day to day work of legal practitioners, and this punctuation had lasting effects on attorneys both emotionally and professionally. As a result, some attorneys began to prepare all of their clients to answer questions about gang affiliation. Gang phantasmagoria became embedded in the asylum process and immigration attorneys felt they had no choice but to embed these practices into their own strategies for screening and preparing their clients. In the process, all asylum applicants become somewhat conceptually criminalized as potentially gang-affiliated.

Katie, a juvenile justice attorney, voiced a similar concern, “I think now we have a problem that it’s not just information sharing but you have to be on the lookout for this as a standard procedure for whichever client you may have.” Whereas Katie used to worry more about immigration authorities accessing information from other law enforcement agencies that might result in some clients being gang labeled, she now assumes that gang allegations could happen to any of her clients.

In some cases, gang phantasmagoria encouraged attorneys to become more cautious about seeking relief if their client fit the profile of gang member, particularly if their client was not already in detention or removal and thus might reveal themselves to the government through an affirmative process. Sandra explained, “If I see any gang indicators with a client, I would be hesitant to pursue active affirmative relief.” A 2019 CUNY School of Law guide to completing USCIS forms advised that immigrants who suspect they may be targeted by USCIS with gang allegations should “consult with a lawyer before you submit an application to determine if you should even apply” (Leszczynski, Arastu, Peleg, and Miller 2019:4, emphasis in original). The ambiguous and unpredictable threat of gang phantasmagoria delivers its own carnage before it even attaches to a body that can be vilified. Whether or not gang allegations ultimately materialize, fewer immigrants may seek relief to which they are entitled based on highly questionable gang profiling practices.

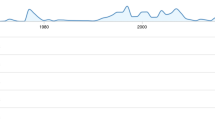

The emergence of enhanced gang questioning and categorization may be one reason behind increased asylum denial rates. While the rates of asylum applications generally increased across immigrant groups during the Trump administration, the rates of denial for Mexicans and Central Americans specifically increased. According to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (2021) at Syracuse University, from 2016 to 2019, the rates of asylum denials increased for Salvadorans from roughly 47 to 87%; 68 to 85% for Guatemalans; 74 to 86% for Hondurans; and 81 to 87% for Mexicans.

As the power of phantasmagoria is predicated on imagined possibilities, attorneys also began to speculate more about the potential for gang allegations in new spaces, further increasing the cycle of anxiety. Sheila, for example, worried about the use of gang allegations to classify a group as a terrorist organization, explaining, “I am very worried that [Jeff] Sessions and [John] Kelly are going to try to bring gangs under the Tier III undesignated terrorist organization classification and make a whole lot of people ineligible for relief that way.” This is the power of gang phantasmagoria; in a Foucauldian sense, even though gang allegations may not ultimately arise, it always feels as if they might and attorneys are forced to proceed accordingly.

Discussion and Conclusion

Through interviews with Southern California attorneys, supplemented by archival materials, I have examined how gang phantasmagoria shapes the realities and strategies of legal practitioners. The portrayal of racialized bodies as monstrous depoliticizes and normalizes state violence, reaffirms the racial order, and legitimizes spectacular punishment in the service of securing geographical borders (Higgins and Swartz 2017; Linnemann, Wall, and Green 2014). In this way, gang phantasmagoria has, first, been used by government officials performatively to portray monstrous threats to the integrity of the asylum system and the country.

Furthermore, because law enforcement and administrative immigration agencies profile people according to highly ambiguous, racialized criteria, the relentless yet mercurial potential for gang allegations envelops attorneys in a fog of apprehension as they move through their cases. Gang phantasmagoria functions as a means of low-grade dread in which asylum seekers and their attorneys know “just enough to be terrified, but not enough either to have a clear sense of what is going on or to acquire proof” (Gordon 2008:110). The unpredictability of gang profiling means that it can strike anyone who fits the racialized profile at many points in time, and the actual application of a gang label to an individual does not have to occur for gang phantasmagoria to be powerful.

However, the effect of gang phantasmagoria is enhanced by its occasional and unpredictable materialization, as is evident by the reverberation of Manuel’s and other attorneys’ experiences through their networks, a dynamic that further feeds fear and anxiety. The Trump administration’s introduction of broad gang questioning in asylum interviews represents a moment that reaffirmed and heightened already present anxieties. The aftermath had lingering consequences, including potential chilling effects as attorneys become more cautious about affirmative immigration processes that could put clients at risk, though this is yet to be seen clearly in reduced asylum application rates, a point to be followed up on in future research over the coming years.

Thus, gang phantasmagoria not only causes anxiety and fear but also paralysis. Its omnipresence and unpredictability fits within the larger context of immigration enforcement wherein immigrants live with constant uncertainty and fear as immigration agents stalk and disappear people from workplaces, homes, and schools (Menjívar and Abrego 2012). These routine yet obscure bureaucratic and enforcement processes have been shown to create and aggravate psychological distress in asylum seekers (Bhatia 2020).

While many scholars have portrayed the ambiguousness of gang profiling as an unintentional inadequacy to be corrected, ideally through cross-jurisdictionally consistent statutes (Huff and Barrows 2015), I suggest that the phantasmagoric quality of gang profiling, and therefore its very power, lies in its unpredictability; it would not otherwise constitute as effective a mechanism of racialized state terror. In this vein, Stefano Bloch and Dugan Meyer (2019) argue that conceptual ambiguity is integral to contemporary racialized security projects. Meyer (2021:279) maintains that security seeks “not to eradicate or rehabilitate such threat objects but rather to administer them, to perpetually restage and reposition the specter of insecurity just beyond reach, but close enough to excite.” The specter of the gang member is constantly unmade and re-made, a circular and omnipresent threat that, by definition, can never be eradicated. Its haunting presence allows for endless fears and thus endless repression.

If the criteria of gang membership were substantially specified and narrowed, the phantasm would not, as it now does, dynamically shift, surge, appear, disappear, haunt, and stretch to appear in new arenas. Gang phantasmagoria is expandable and contractible, allowing state actors in various legal and administrative venues to target racialized others when alternative charges are not available because they require a higher evidentiary bar. For example, in 2017, the US House of Representatives passed legislation under which the government could categorize as a gang any group, such as a church, that offers shelter to an undocumented immigrant (Criminal Alien Gang Member Removal Act 2017). More recently, the Salt Lake County District Attorney charged Black Lives Matter protesters with gang enhancements—additional time added to a sentence when a crime is considered gang related—because of their participation in first amendment protected activity, with a potential sentence of five years to life (Whitehurst 2020). Though it is very unlikely any of the protesters will receive life sentences, the shocking phantasmagoric appearance of a severe gang enhancement illustrates how authorities can deploy this punitive mechanism against people of color in a way that could have a chilling effect on legal activity.

Gang phantasmagoria is thus neither confined to the immigration system nor to the Trump administration. It was, after all, the Obama administration that institutionalized gang profiling in the immigration system in important ways, most notably through gang profiling in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) application process and in detention risk assessments (Chazaro 2016). Gang phantasmagoria has become deeply ingrained in immigration and other law enforcement practices, and the vilification of alleged gang members functions across the political spectrum in reinforcing humanistic frameworks that both enable and obscure the continuation of racialized regimes of violence and social control (Valdez 2020). As such, it is highly likely that gang phantasmagoria will continue to terrorize attorneys and their clients under subsequent administrations.

Notes

A form of protection tax that people within gang territory are forced to pay.

References

Aba-Onu, U. F., Levy-Pounds, N., Salmen, J., & Tyner, A. (2010). Evaluation of gang databases in Minnesota and recommendations for change. Information & Communications Technology Law, 19(3), 223–254.

Associated Press. (2020). Watch: Trump administration announces arrests in ‘campaign to destroy MS-13’. Public Broadcasting Service, July 15.

Ball, R. A., & Curry, G. D. (1995). The logic of definition in criminology: Purposes and methods for defining “gangs”. Criminology, 33(2), 225–245.

Barak, M. P., León, K. S., & Maguire, E. R. (2020). Conceptual and empirical obstacles in defining MS-13. Criminology & Public Policy, 19, 563–589.

Becker, H. S. (1963). Outsiders: Studies in the sociology of deviance. New York: The Free Press.

Bhatia, M. (2020). The permission to be cruel: Street–level bureaucrats and harms against people seeking asylum. Critical Criminology, 28, 277–292.

Bloch, S. (2019). Broken windows ideology and the (mis)reading of graffiti. Critical Criminology, 28, 703–720.

Bloch, S., & Meyer, D. (2019). Implicit revanchism: Gang injunctions and the security politics of white liberalism. EPD: Society and Space, 37(6), 1100–1118.

Bloch, S. & Olivares-Pelayo, E.A. (2021). Carceral geographies from inside prison gates: The micro-politics of everyday racialisation. Antipode, 53(5), 1319–1338.

Brayne, S. (2020). Predict and surveil: Data, discretion, and the future of policing. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Brown, J. A. (2016). Running on fear: Immigration, race and crime framings in contemporary GOP presidential debate discourse. Critical Criminology, 24, 315–331.

Carter, J. H. (2019). Carceral kinship: Future families of the late Leviathan. Journal of Historical Sociology, 32(1), 26–37.

Chacón, J. M. (2007). Whose community shield? Examining the removal of the ‘criminal street gang member.’ The University of Chicago Legal Forum, 317-357.

Chauvin, S., & Garcés-Mascareñas, B. (2012). “Beyond informal citizenship: The new moral economy of migrant illegality.” International Political Sociology, 6(3), 241–259.

Chazaro, A. (2016) Challenging the criminal alien paradigm. UCLA Law Review, 63, 594–664.

Cohen, S. (1972). Folk devils and moral panics: The creation of the mods and rockers. Oxford: Martin Robertson.

Contreras, R. (2013). The stickup kids: Race, drugs, violence, and the American dream. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Conway, K. (2017). Fundamentally unfair: Databases, deportation, and the crimmigrant gang member. American University Law Review, 67, 269–325.

De Cock, C., Baker, M., & Volkman, C. (2011). Financial phantasmagoria: Corporate image-work in times of crisis. Organization, 18(2), 153–172.

Criminal Alien Gang Member Removal Act, H.R. 3697, 115th Cong. (2017).

Durán, R. J. (2009). Over-inclusive gang enforcement and urban resistance: A comparison between two cities. Social Justice, 36(1), 82–101.

Durán, R. J., & Campos, J. A. (2019). Gangs, gangsters, and the impact of settler colonialism on the Latina/o experience. Sociology Compass, 14(3), 1–15.

Emerson, R.M., Fretz, R.I., & Shaw, L.L. (2011). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. Second Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Esbensen, F. A., Winfree, Jr., L. T., He, N., & Taylor, T. J. (2001). Youth gangs and definitional issues: When is a gang a gang, and why does it matter? Crime & Delinquency, 47(1), 105–130.

Estévez, A. (2020). Mexican necropolitical governmentality and the management of suffering through human rights technologies. Critical Criminology, 28, 27–42.

Fiddler, M. (2011). A ‘system of light before being a figure of stone’: The phantasmagoric prison. Crime Media Culture, 7(1), 83–97.

Fraser, A., & Atkinson, C. (2014). Making up gangs: Looping, labelling and the new politics of intelligence-led policing. Youth Justice, 14(2) 154–170.

Galli, C. (2017). A rite of reverse passage: The construction of youth migration in the US asylum process. Ethnic and Racial Studies, DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1310389

Galli, C. (2020). Humanitarian capital: How lawyers help immigrants use suffering to claim membership in the nation-state. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(11), 2181–2198.

Garcia-Leys, S., & Brown, N. (2019). Analysis of the Attorney General’s Annual Report on CalGang for 2018. Los Angeles, CA: Urban Peace Institute.

Garcia-Leys, S., Thompson, M., & Richardson, C. (2016). Mislabeled: Allegations of gang membership and their immigration consequences. UC Irvine School of Law.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Goodman, P. (2008). ‘It’s just Black, White, or Hispanic’: An observational study of racializing moves in California’s segregated prison reception centers. Law & Society Review, 42(4), 735–770.

Gordon, A. F. (2008). Ghostly matters: Haunting and the sociological imagination. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Gunning, Tom. (2004). Phantasmagoria and the manufacturing of illusions and wonder: Towards a cultural optics of the cinematic apparatus. In A. Gaudreault, C. Russell, & P. Veronneau (Eds.), The cinema: A new technology for the 20th century (pp. 31–44). Editions Payot Lausanne.

Hallsworth, S., & Young, T. (2008). Gang talk and gang talkers: A critique. Crime Media Culture, 4(2), 175–195.

Hesson, T. (2019). Trump’s pick for ICE director: I can tell which migrant children will become gang members by looking into their eyes. Politico, May 16.

Higgins, E. M., & Swartz, E. (2017). The knowing of monstrosities: Necropower, spectacular punishment and denial. Critical Criminology, 26:91–106.

Hlass, L. L., & Prandini, R. (2018). Deportation by any means necessary. San Francisco: Immigrant Legal Resource Center.

Howell, K. B. (2019). Prosecutorial misconduct: Mass gang indictments and inflammatory statements. Dickinson Law Review, 123(3), 691–712.

Huff, R. C., & Barrows, J. (2015). Documenting gang activity: Intelligence databases. In S. H. Decker & D. C. Pyrooz (Eds.), The handbook of gangs, first edition (pp. 59–77). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Jessop, B. (2014). A specter is haunting Europe: A neoliberal phantasmagoria. Critical Policy Studies, 8(3), 352–355.

Johnson, K. (2001). The scarlet feather: Racial phantasmagoria in What Maisie Knew. The Henry James Review, 22(2), 128–146.

Katz, J., & Jackson-Jacobs, C. (2004). The criminologists’ gang. In C. Sumner (Ed.), The Blackwell companion to criminology (pp. 91–124). Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Kim, S. M. (2018). Trump warns against admitting unaccompanied migrant children. The Washington Post, May 23.

Lam, K. D. (2012). Racism, schooling, and the streets: A critical analysis of Vietnamese American youth gang formation in Southern California. Journal of Southeast Asian American Education and Advancement, 7(1), DOI:https://doi.org/10.7771/2153-8999.1043

Leszczynski M., Arastu, N., Peleg, T., & Miller, R. (2019). Guide to completing U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) forms in the gang allegations context. New York: CUNY School of Law.

Linnemann, T., & McClanahan, B. (2017). From ‘filth’ and ‘insanity’ to ‘peaceful moral watchdogs’: Police, news media, and the gang label. Crime Media Culture, 13(3), 295–313.

Linnemann, T., Wall, T., & Green, E. (2014). The walking dead and killing state: Zombification and the normalization of police violence. Theoretical Criminology, 18(4), 506–527.

Lopez-Aguado, P. (2018). Stick together and come back home: Racial sorting and the spillover of carceral identity. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Mannoni, L., & Brewster, B. (1996). The phantasmagoria. Film History, 8(4), 390–415.

Manuel, K.M. (2014). Asylum and gang violence: Legal overview. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

Marden, P. (2014). The digitised public sphere: Re-defining democratic cultures or phantasmagoria? Javnost - The Public, 18(1), 5–20.

Marston, R. J. (2019). Guilt by alt-association: A review of enhanced punishment for suspected gang members. University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform, 52, 923–935.

Maxson, C. L. (1999). Gang homicide: A review and extension of the literature. In M. D. Smith & M. A. Zahn (Eds.), Homicide: A sourcebook of social research (pp. 239–254). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Maxson, C. L., & Klein, M. W. (1996). Defining gang homicide: An updated look at member and motive approaches. In C. R. Huff (Ed.), Gangs in America (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Menjívar, C., & Abrego, L. (2012). Legal violence in the lives of immigrants. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress.

Meyer, D. (2021). Security symptoms. Cultural Geographies, 28(2), 271–284.

Miller, W. B. (1975). Violence by youth gangs and youth groups as a crime problem in major American cities. National Institute for Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Muñiz, A. (2015). Police, power, and the production of racial boundaries. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Noferi, M., & Koulish, R. (2014). The immigration detention risk assessment. Georgetown Immigration Law Journal, 29, 45–94.

Picart, C. J. K., & Greek, C. (2007). Profiling the terrorist as a mass murder. In C. J. K. Picart & C. Greek (Eds.), Monsters in and among us: Toward a Gothic criminology (pp. 246–279). Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

Rafter, N., & Ystehede, P. (2010). Here be dragons: Lombroso, the Gothic and social control. In M. Deflem (Ed.), Popular culture, crime and social control (Sociology of Crime, Law and Deviance, Vol. 14) (pp. 263–284). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Ralph, L. (2014). Renegade dreams: Living through injury in gangland Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ramirez, D. (2018). Racial phantasmagoria: The demonisation of the other in Richard Mosse’s ‘Incoming’. NECSUS, 7(2), 301–307.

Reid, S. E., &Valasik, M. (2020). Alt-right gangs: A hazy shade of white. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Rios, V. M. (2017). Human targets: Schools, police, and the criminalization of Latino youth. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Schwabenland, C., &Tomlinson, F. (2015). Shadows and light: Diversity management as phantasmagoria. Human Relations, 68(12), 1913–1936.

Skott, S., Nyhlén, S., & Giritli–Nygren, K. (2020). In the shadow of the monster: Gothic narratives of violence prevention. Critical Criminology, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-020-09529-x

Sothcott, K. (2016). Late modern ambiguity and gothic narratives of justice. Critical Criminology, 24:431–444.

Stuart, F. (2020). Code of the tweet: Urban gang violence in the social media age. Social Problems, 67, 191–207.

Sullivan, L. E. (2014). Bad boys, whatcha gonna do when they come for you: An examination of the United States’ denial of asylum to young Central American males who refuse membership in transnational criminal gangs. Duquesne Law Review, 52(1), 231–262.

The New York Times. (2018). Kirstjen Nielsen addresses families separation at border: Full transcript. The New York Times, June 18.

Timmermans, S., & Tavory, I. (2012). Theory construction in qualitative research: From grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociological Theory, 30(3), 167–186.

Tosh, S. (2019). Drugs, crime, and aggravated felony deportations: Moral panic theory and the legal construction of the ‘criminal alien’. Critical Criminology, 27, 329–345.

Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. (2021). Asylum Decisions by Custody,

Trump, D.J. (2017a). Executive order 13769: Protecting the nation from foreign terrorist entry into the United States. Federal Register, 82(18), 9793–8797.

Trump, D.J. (2017b). Executive Order 13773: Enforcing federal law with respect to transnational criminal organizations and preventing international trafficking. Federal Register, 82(29), 10691–10693.

Trump, D.J. (2018). President Donald J. Trump’s State of the Union address. Washington, DC: The White House.

US Attorney’s Office. (2017). MS-13 gang members indicted for 2016 murders of three Brentwood High School students. Eastern District of New York: US Department of Justice.

Valdez, I. (2020). Reconceiving immigration politics: Walter Benjamin, violence, and labor. American Political Science Review, 114(1), 95–108.

Valdivia Ramirez, O., Faria, C., & Maria Torres, R. (2021). Good boys, gang members, asylum gained and lost: The devastating reflections of a bureaucrat-ethnographer. Emotion, Space and Society, 38, 100758.

Valier, C. (2002). Punishment, border crossings and the powers of horror. Theoretical Criminology, 6(3), 319–337.

Walker, D., & Cesar, G. T. (2020). Examining the ‘gang penalty’ in the juvenile justice system: A focal concerns perspective. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 18(4), 315–336.

Wamsley, L. (2019). Trump calls for asylum-seekers to pay fees, proposing new restrictions. National Public Radio, April 30.

Whitehurst, L. (2020). Utah protesters face charges with potential life sentence. The Washington Post, August 6.

Wilkinson, E.B. (2010). Examining the Board of Immigration Appeals’ social visibility requirement for victims of gang violence seeking asylum. Maine Law Review, 62(1), 387–419.

Zilberg, E. (2007). Gangster in guerilla face: A transnational mirror of production between the USA and El Salvador. Anthropological Theory, 7(1), 37–57.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Muñiz, A. Gang Phantasmagoria: How Racialized Gang Allegations Haunt Immigration Legal Work. Crit Crim 30, 159–175 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-022-09614-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-022-09614-3