Abstract

This paper stands in the learning tradition of H. J. Eysenck who, sixty-three years ago in 1961, wrote that pathological/psychological disorders are learned/conditioned responses or habits that are non-adaptive. Eysenck argued that persons who receive Psychological Treatment (i.e. ‘psychotherapy’) are best served when their symptom complaints are addressed with well-established learning guidelines. In a similar vein, our proposal presents a general overview of learning and following Eysenck’s lead, describes six general characteristics (Eysenck listed 6 characteristics of ‘psychotherapy’) of a learning-based proposal for Psychological Treatment. Our proposal places a heavy emphasis on the therapist’s role as teacher. In addition, four acquisition learning examples are presented showing how one constructs a learning approach that addresses psychological symptom categories.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

General Overview of Learning Theory

People learn to be who they are. Through our idiosyncratic physiological make-up and myriad developmental experiences that occur in the early caregiving environment, you and I learn how to behave. Some learning experiences or the lack thereof, ill-equip certain people to cope effectively with the adult contingencies that all of us face. Psychopathology is a term we use to describe those whose inadequate learning histories consign them to adult maladaptive patterns of functioning. Frequently, these individuals seek out mental health practitioners to help them correct abnormal behavior that stems from earlier inadequate learning. It is the authors’ opinion that the structure of whatever remedial treatment is offered should rest on learning principles. The underlying assumption of this paper is that correcting early faulty learning is the essential goal of what we call Psychological Treatment (Barlow, 2004). Several examples of early faulty learning experiences are described below to illustrate what we mean by the construct learning.

The pathological behavior of pervasive interpersonal avoidance may be learned in the presence of parents/caregivers who physically or verbally/nonverbally abuse, severely punish, or psychologically demean a growing child (e.g., Cicchetti & Toth, 1998; McCullough et al., 2015). Chronic felt-inadequacy and performance failure often accompany reports of these developmental histories. Pathologically deviant/asocial behavior may also be learned by children whose developmental years are spent observing caregiver adults who engage in asocial behavior across numerous interpersonal situations (e.g., bullying weaker individuals, petty thievery, cheating in business, pathological lying, observable admiration of authoritarian individuals, etc.). The outcome in children of such parents is often social maladaptive behavior, interpersonal conflict with peers and adults (particularly teachers), as well as personal distress (e.g., Carlson, 2012). And finally, caregivers who emotionally or physically deprive/neglect the child through patterns of detachment and withdrawal frequently produce youngsters with interpersonal engagement and relationship issues (e.g., Hammen et al., 1990). Regardless of the type of pernicious developmental history an individual experiences, the child becomes an adult. Entering adulthood, they bring with them vestiges of the early maladaptive learning and act out their history through the interpersonal encounters they have—in the family as spouses or parents, at work with colleagues or management, or in the social context with friends or acquaintances. We turn now to defining specific learning terminology and rely on Mark Bouton’s (2007) views of the learning variables operative in early learning.

Learning Terms. Bouton (2007) describes four variables that are present in all early learning environments, both normal and pathological. They are (1) environmental stimuli (symbolized by S) that contain many of the learning cues in the child’s world; the (2) behaviors (symbolized by R) a child cognitively, emotively, and motorically learns and associates with the learning cues (S); and the (3) reinforcements (symbolized by S*) that cement the learned associations between the Ss and Rs. A fourth variable, labeled (4) Occasion Setters (OS), is also associated with the R → S* associations. The OS is a learned cognitive expectancy construct providing information to the child concerning what type of reinforcement (either positive reinforcement or punishment) is likely to occur for a specific behavior in a particular context. For example, when Jim’s playmate, John, visits the home (OS), mother (S) frequently verbally punishes the boys’ behavior (R → S*); however, when another playmate, Bill, visits (OS), mother often complements/positively reinforces (S*) their play. The visits of the two different playmates function as two Occasion Setters that describe mother’s expected reinforcement (S*). By providing a cognitive expectancy function, Occasion Setters teach children what type of reinforcement (S*) to expect from their behavior (R) when emitted in different stimulus contexts (S).

A notable exception to the R → S* association examples occur when deprived/neglected children receive “no reinforcement” from parents/caregivers for whatever they do (R). This reinforcement type is symbolized by 0 (the 0 denotes the cognitive expectancy of “no reinforcement”). The R → 0 expectancy is often present among adult Psychological Treatment patients who were physically and emotionally deprived as children. Summarily, the symbols for the learning terms are listed below:

-

S = environment stimuli

-

R = behavior

-

S* = reinforcement/consequence

-

R → S* = connection between a behavior and a reinforcer

-

R → 0 = no reinforcement expected for behavior

-

OS = Occasion Setter: cognitive expectancy construct learned in a stimulus context where a behavior becomes associated with a particular type of reinforcement (either positive; punishment; or none)

To further clarify the function of the OS cognitive expectancy, three examples are provided.

-

The reinforcement type expected in the OS context in the presence of maltreating parents/caregivers (S) will lead to avoidance behavior (R): to evade or dodge the expected hurtful consequence (S*).

-

The reinforcement type expected in the OS context for children who grow up in the presence of deviant parents/caregivers (S) will lead to a mimicking of the aberrant caregiver behavior (R): to obtain positive reinforcement (S*).

-

The reinforcement type expected in the OS context for children who grow up with neglectful or depriving parents/caregivers (S): no reinforcement (0) forthcoming.

Mark Bouton (2007, p. 33), a notable and retired Pavlovian Scholar at the University of Vermont has described these four interacting learning constructs and provided the diagram in Fig. 1 to illustrate how the variables interact.

Bouton’s (2007) diagram of the four interacting learning variables

The reader will quickly recognize that Fig. 1 reflects a synthesis of Pavlovian respondent learning and Skinnerian operant learning. The implications for us here in Fig. 1 are that these learning constructs are active in every Psychological Treatment session—whether they are explicitly emphasized or not by practitioners. How we therapists behave in Psychological Treatment is done figuratively with Ivan Pavlov (1927) sitting on our left shoulders (Pavlov’s major variables are operative in our motivational, emotional, and memory work) and B. F. Skinner (1938, 1953) sitting on our right shoulders (Skinner’s major variables are operative in our behavioral evaluations and motoric training work).

General Learning Definition of Psychological Treatments

Standing in the tradition of Eysenck (1961) and proposing a learning theory definition of Psychological Treatment (Barlow, 2004) is a daunting task. It is especially challenging when viewed against the large backdrop of myriad definitions of Psychological Treatment (Barlow, 2004) and psychotherapy in our field today. Eysenck (1961) wrote about the optimal learning treatment when he penned the following:

“The methods (i.e. treatment) used are of a psychological nature, i.e., involve such mechanisms as explanation, suggestion, persuasion, and so forth…. The procedure of the therapist is based upon some formal theory regarding mental disorder in general, and the specific disorder of the patient in particular.” (1961, p. 698).

We attempted this undertaking because we opined that Psychological Treatment may achieve greater effectiveness when it is grounded in learning theory. So, how do we define Psychological Treatment from a learning theory perspective? Six defining characteristics come to mind. Each will be delineated and discussed briefly.

-

Psychological Treatment is primarily an interpersonal undertaking that includes a) a trained therapist [T]; b) a patient who presents with a DSM-5 (APA, 2013) diagnosis [P]; and c) an empirically validated treatment [Rx] designed specifically to ameliorate the diagnostic problem. These three independent variable constructs provide structure to Psychological Treatment that enable practitioners to empirically investigate the effectiveness of their work.

-

Secondly, in order to conduct empirical Psychological Treatment, an acquisition learning design must first be operationalized into measurable learning units (e.g., Long et al., 2023). There are three questions practitioners must answer in constructing the acquisition learning design: 1) At the BEGINNING of treatment: What am I trying to teach the patient to resolve the diagnosis? 2) At the TERMINATION of treatment: How much of the teaching content has the patient learned? 3) At POST TREATMENT, the empirical question is asked: Using visual inspection, does a potential “dependent” relationship exists between the outcome-process measures of change (e.g., BDI-II [Beck et al., 1996] or BAI [Beck & Steer, 1993] scores, etc.) and the acquired learning curve(s)?

-

Thirdly, single-case (intensive) design structure provides an excellent Type I pilot study design for Psychological Treatment investigations (Rounsaville et al., 2001). Intensive designs provide an effective mechanism to identify potential change variables in Type I research (e.g., McCullough, 1984, 1991, 2006; Sidman, 1960)

-

The fourth characteristic involves the learning content. It is taught to the patient and denotes the “subject matter” of Psychological Treatment. When Psychological Treatment is defined using Learning Theory, casework must implicate a “curriculum” to be taught.

-

The fifth characteristic involves the Behavioral Equation that best describes the Psychological Treatment proposed herein: B = f (Therapist x Patient). The equation describes an Interpersonal Model of Behavior. Dyadic interactions, particularly when therapists are authentically being themselves and responding to patients as reciprocal dyadic participants, create an effective learning environment for patient-change (Keller et al., 2000; Kiesler, 1988, 1996; McCullough, 2000).

-

The sixth characteristic involves the Therapist Role in Psychological Treatment. There are several features of the role. They are as follows:

-

(a)

The Therapist Role is defined as a “teaching comrade” (Long et al., 2023; McCullough, 2006; McCullough et al., 2015). Teaching and comradeship both implicate the type of didactic relationship that practitioners enact with patients.

-

(b)

Therapists work to create felt-safety in the dyadic relationship in order to augment learning. A felt-safe dyadic environment will facilitate the creation of new Occasion Setter contexts for the novel learning patients will acquire (i.e. the adaptive R → S* connections) (see Fig. 1). This will particularly be realized as patients experience positive reinforcement for the new behavior that replaces the older expectancies of punishment and rejection (S*s).

-

(c)

A third characteristic of the Therapist Role is seen in a clinician who choreographs in-session patient behavioral consequences (S*) (Skinner, 1968). Choreographing consequences means that clinicians (S), as noted above, create new Occasion Setter (OS) contexts for patients between their Rs and S*s (see Fig. 1). When patients learn to identify what consequences (S*s) their behavior has on the practitioner as well as others, behavioral change is potentiated (McCullough, 2000; McCullough et al., 2015). This frequently happens in moments when negative reinforcement occurs; that is, when felt-relief occurs in a patient for emitted adaptive behavior. Terminating felt-distress or other negative emotions for adaptive behavior enactment is the strongest remedial variable in Psychological Treatment. When negative reinforcement incidents occur, the practitioner must stop and make certain the patient attends to what just happened (i.e. identify the R → S* event).

-

(d)

A fourth characteristic of the Therapist Role is to structure the session to avoid “talking about” problems. Talking about issues occur when therapists ask “why?” questions. For example, “Why do you think you felt that way?” “Why did you behave the way you did? etc.” Therapists who spend time talking about problems rarely produce patient change. Conversely, actual problematical behaviors (R) occurring in the session make the best “treatment” targets.

-

(e)

The final Therapist role characteristic involves a willingness to become a recipient consequence for patient behavior and make the effect explicit in the dyad. Interpersonally, patients constantly affect clinicians by what they do. Directing patients’ attention to the effect/consequences they just had on the practitioner or said another way, making interpersonal effects in the dyad explicit, offers a first-hand opportunity to modify behavior. The interpersonal maneuver of disclosing “what” just occurred (R) and focusing the patient’s attention on the consequence (S*) (e.g., “When you said that, you pushed me away.”), avoids “talking about” behavior and addresses, directly, the Occasion Setter ramifications of the R → S* connection (see Fig. 1) (McCullough, 2000, 2006). This disclosure directs the patient’s attentional focus to the person of the therapist (and off of themselves) as the consequence of their behavior.

-

(a)

The six characteristics of Psychological Treatment described above illustrate the important structure and function of patient-work as we view it. The underlying foundation of our proposal is based upon Learning Theory and the learning curriculum that is taught patients to rectify the DSM-5 (APA, 2013) disorder. We turn now to providing several example verbatim scenarios that, hopefully, will clarify further how our Learning Theory proposal (combined with measurable learning units) is constructed. The example scenarios are drawn from patient symptom categories described in contemporary Psychological Treatment models.

Several Example Verbatim Learning Theory Scenarios Illustrating How Psychological Treatment Type I Designs Can Be Constructed

-

1.

Patient Overgeneralization: Refers to a pattern of drawing a general rule or conclusion on the basis of one or more isolated events (Beck et al., 1979, p. 14).

Session 3 Verbatim

Patient: You talk just like the other therapists I’ve seen. You are all just alike (R).

Therapist: What do you mean?

Patient: You try to be nice, accepting, and supportive to everything I say. You say all the right things. Seen one, seen them all.

Therapist: You make me feel like I don’t exist (introducing the interpersonal consequence: S*).

Patient: What do you mean?

Therapist: Your comment about me. You don’t even know me, and you talk like you do. Where’d you learn to talk like this—like you know someone you don’t?

Patient: It’s just what I was thinking.

Therapist: You didn’t answer my question. Try again. Where’d you learn to talk like this?

Patient: You sound like what I said bothered you.

Therapist: It did.

Patient: Well then, I’m sorry.

Therapist: Think you’ve missed my point. I still feel that I don’t exist to you—that I’m just one of many. Where did you learn to talk like this?

Patient: I don’t know. I just say the things I’m thinking when I’m with people.

Therapist: Ever thought that what you say has effects on the other person (S*)—particularly when you talk like you know them when you don’t?

Patient: Never have. Like I said, I just say things I’m thinking. I do this with everyone—gets me in trouble with others when I open my big mouth. I don’t have many friends. Nobody sticks around very long.

Therapist: Why don’t we focus on the effects your words have on me. It might help you in your conversations with others (introduction to a new Occasion Setter).

Patient: I’m game.

Comments

This scenario is an example where the clinician positions himself to become a consequential recipient of the patient’s behavior. The verbal target is overgeneralization (R) and when the patient emits it in the session, the practitioner makes the personal effects (S*) explicit. In social talk, people rarely provide feedback to people who irritate them with such comments. The usual reaction is to avoid future contact. If overgeneralization is a significant problem for this individual, teaching him to ask why and what questions before he says whatever he’s thinking must be done. Several steps must be learned: (1) stop and think about what one is going to say before speaking; (2) next, verbalize the comment as a why or what question (e.g., “Why are you being so nice to me?” or, “What are you trying to do being so nice to me?” (3) say your question; (4) observe the effect your what or why question has on the person—what’s their reaction to what you said? And lastly, log your correct steps in your Daily Dairy.

These 4 steps in the acquisition learning program for non-generalization are taught the patient. The steps are practiced in the therapy session. The steps should also be written on a whiteboard or flip-chart during sessions; the patient must also write the steps on a 3 × 5 card and carry the card around in their pocket. They must look at it once an hour and repeat it to themselves. Patients can also record the frequency per day when the steps are said to another and record how many steps were accurately performed. The first step, if overgeneralization is a longstanding habit, may be difficult to accomplish in the beginning. Patients may make overgeneralizing statements to another without thinking then, realize their oversight and make the last three steps correctly. The learning progress can be charted in a diary illustrating the frequency of occurrence of the target behaviors per day and with each encounter, rating the accuracy of the four learning-steps per encounter. The data are brought to every session where the new learning is monitored, reinforced, and discussed. This patient will be shown how to transfer their performance data on a bar graph. The graph is illustrated in Fig. 2.

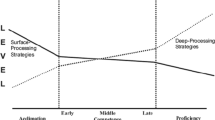

Another way to illustrate the shift in Occasion Setters context with the new non-generalization learning program is shown in Fig. 3.

-

2.

Patient Selective Abstraction: Focusing on a detail taken out of context; ignoring other more salient features of the situation and conceptualizing the whole experience on the basis of the fragment (Beck, et al., 1979, p. 14).

Session 7 Verbatim

Therapist: Mary. it’s good to see you today……..Boy, I’m tired. This has been a long day. Started at 6 AM when I had to take my son to the doctor for a check-up……You hung your head and looked away when I said I took my son to the doctor. What’s going on?

Patient: I felt that you would rather be doing anything than seeing me. I knew you would get tired of seeing me (R).

Therapist: Tell me again what you just said.

Patient: That you’d rather do anything than see me—I just know it.

Therapist: You just knocked me out of my chair with your comment! (introducing the interpersonal consequence: S*)

Patient: What do you mean?

Therapist: Just what I said.

Patient: I’m sorry, I can’t do anything right.

Therapist: You didn’t hear what I said.

Patient: I don’t understand.

Therapist: What did I just say to you?

Patient: You said I knocked you out of your chair with my comment.

Therapist: So, what do you think I meant?

Patient: You didn’t like me saying you’d rather be doing anything than seeing me.

Therapist: That’s close, but you still haven’t got it. Try again.

Patient: You think I said something wrong.

Therapist: What was wrong with your comment?

Patient: I was wrong about you.

Therapist: Yes, you were! Now, what’s the problem with your comment?

Patient: I don’t know.

Therapist: You didn’t ask me. You just told me what I thought. Why did you say that to me? (creation of a new Occasion Setter)

Patient: It’s what I thought.

Therapist: I know you thought it. What’s missing here in your comment?

Patient: I didn’t ask you what you thought.

Therapist: What else is suggested in your comment?

Patient: I expected the worse.

Therapist: Yes, right again.

Therapist: You thought something highly negative about me. Where did you learn to mind-read other people—especially negative thoughts that implicate you?

Patient: Don’t know. I just say things like that.

Therapist: They have powerful effects on others! Especially on me, and I’ve never thought what you attributed to me—that I don’t want to see you.

Patient: You haven’t?

Therapist: NO! What can you learn here?

Patient: To ask, not tell!

Therapist: You got it! Let’s make a plan to stop this sort of talk. What have you got to do first?

Patient: Think before I say anything.

Therapist: That’s a good first step; What comes next?

Patient: To ask and not jump to mind-reading negativity.

Therapist: Good. Now, what’s a third step.

Patient: It’s like what you’ve said to me before. Pay close attention to the reactions of the other person; that is, listen to what they say and how they say it. Is it a positive or negative reaction?

Therapist: Then, what’s the fourth step.

Patient: React to their reaction by saying something and focusing on what they actually say and not my negative mind-read.

Therapist: Okay, you’ve constructed a four-step program:

-

1)

Think before talking;

-

2)

Ask myself what the other person actually said;

-

3)

Observe their tone of voice;

-

4)

React to their actual comment.

Be sure you log your correct steps in your Daily Dairy whenever these events occur.

Therapist: Let’s see if we can stop your mind-reading reactions with a different kind of verbal reaction—one that pulls you out of your head and into the other person’s world. Now, write down our plan in your Daily Dairy and log one time each week when you have this sort of encounter. Please bring your Daily Dairy with you from now on and we’ll review what happened.

Comments

Mary provides a scenario example of a Beckian symptom of depression labeled Selective Abstraction (SA) (Beck et al., 1979, p. 14). We have illustrated above how the clinician verbally consequated the target behavior, SA, that Mary emitted in the session. We will illustrate a second way to graph the averaged weekly 4-step learning program to modify SA and then overlay Mary’s weekly BDI-II scores (Beck et al., 1996) over the acquisition learning curve. (see Fig. 4).

Again, another way to illustrate the shift in Occasion Setters context with the new Non-Selective Abstractive learning program is shown below in Fig. 5.

Session 3 Verbatim

Patient: I’ve never needed anyone’s help before. Always been very independent and done my thing. Losing two jobs in a row because of downsizing has left me in a mess. I called you because I didn’t know anywhere else to turn.

Therapist: Sam, are you telling me that you need help?

Patient: I don’t know what I need, but I surely feel uncomfortable sitting here and telling you all this (R).

Therapist: You mean you’ve never felt this vulnerable before now.

Patient: I guess so.

Therapist: What do you need from me?

Patient: Answering your question is about the hardest thing for me to do. I guess……I need your support right now. I feel really alone and by myself.

Therapist: Well, I’m glad you called and let’s see if I can offer you something that you’ve never needed before.

Patient: What’s that?

Therapist: Help from another person. I don’t know how you’ve survived this long without having to ask for help.

Patient: It just doesn’t feel right. I feel like I’m doing something wrong. Like I’m committing a sin or something.

Therapist: I think I can show you something that, obviously, you’ve never experienced before. (beginning the creation of an Occasion Setter)

Patient: What’s that?

Therapist: That it’s okay to need help and ask for it.

Patient: That’s hard to believe.

Therapist: I’m going to take these 3 x 5 cards and ask you to write a sentence on each one. We’ll label the cards A, B, and C. In one sentence, tell me what it’s like to feel that you are not allowed to ask for help.

Patient: I could never ask anyone for help.

Therapist: Okay, write that sentence on Card A. Good. Now. Make up another sentence for Card B. Preface the sentence with “Sometimes I feel…” and finish the sentence that says it would be okay if you asked for help.

Patient: I could never feel that it’s okay. But, I could say: Sometimes I feel that it is okay to ask for help.

Therapist: Now, write that on Card B. Now the third Card C. Write that same sentence but this time preface it with “More often than not……”.

Patient: More often than not I feel it is okay to ask for help.

Therapist: Look at the three cards and read what you’ve written.

Patient: God, I feel uncomfortable doing this. But here’s what I’ve written:

-

Card A: I could never ask anyone for help.

-

Card B: Sometimes I feel it is okay to ask for help

-

Card C: More often than not, I feel it is okay to ask for help.

Therapist: Okay. Compare each card with each other. That is, compare Card A with B and choose the one that best describes you right now. Then A with C and chose the one that’s closest to how you feel right now. Finally, choose between B and C.

Patient: I choose A over B; A over C; and B over C.

Therapist: You and I will keep talking for a few sessions and each time you come in, I’ll ask you to compare each card with the others and choose the one that best fits how you feel right then. Any questions?

Patient: No, think I’ve got it though I don’t see the point of this.

Therapist: I think you will over the next few sessions.

Comment

Teaching Sam that it is acceptable to ask for support and help from another became the goal of treatment. Assessing the acquired learning was done using a pared comparison technique developed by Shapiro (1961, 1964; Shapiro et al., 1973). The instrument is called the Personal Questionnaire (PQ). There are three levels of ratings: Card A (illness level); Card B (improvement level); and Card C (recovery level). Scoring is done with four possible combinations of choices; they are scored as follows: Card A over B, A over C, and B over C [illness] = 4.0; Card B over A, A over C, B over C [minimal improvement] = 3.0; Card B over A, C over A, B over C [significant improvement] = 2.0; Card B over A, C over A, C over B [recovery] = 1.0. Here is the way Sam’s acquisition learning of the supportive treatment goal progressed as he was taught that asking for help was okay. The Personal Questionnaire data are shown in Fig. 6.

Sam reached the acquisition learning criterion in the eleventh session (see Fig. 6). He rated feeling much more acceptance and comfortable asking for help from others than he did in Session 3. The Supportive Psychotherapy acquired learning goal had been achieved and was validated by the PQ data.

-

4.

Patient Acquisition Learning to Control Anger: Clark was a large and physically strong 52-year-old foreman working for a construction company that built highways and roads. He was diagnosed with an early-onset Persistent Depressive Disorder (PDD) lasting 35 years. The practitioner decided to administer CBASP (Long et al., 2023; McCullough, 2000; McCullough et al., 2015) but Clark’s frequent anger outbursts required addressing before CBASP could be undertaken. He was currently facing a court date for an Assault and Battery charge involving one of his workmen whom he had concussed in a fight during work. The patient would display rage whenever something happened that he did not like. In the fourth session, he asked if the session time for the next meeting could be changed. The clinician had a full schedule and could not accommodate his request. Clark became very angry with the therapist.

Session 4 Verbatim

Patient: I don’t see why you cannot make an exception for me.

Therapist: You happened to ask me at a time when my schedule is full. I have no extra spaces that I can slip you in.

Patient: LOOK HERE, I think you are lying to me! No one’s that busy (R).

Therapist: I’m very serious. I have no flexibility right now to make a schedule change.

Patient: This really makes me angry! I’ve got a situation at work that I’m facing, and I’ve got to change our time. Or, I will have to meet with you another time the following week.

Therapist: I’m locked in with our schedule. Cannot change it.

Patient: You are such a liar! You are not important enough not to make the change.

Therapist: I’m stuck with the schedule we have.

Patient: You are a horrible therapist then. You don’t take good care of your patients! How did you ever get licensed? I heard you are really supposed to be good. I must have heard wrong.

Therapist: I’m going to say again what I said. You have asked me to do something that, right now, I cannot do. My schedule will not allow it.

Patient: You are such a liar! I can’t believe this.

Therapist: Why are you beating up on me? You’re knocking the life out of me. (beginning the consequence sequence: S*)

Patient: What are you talking about?

Therapist: Just what I said. You are beating up on me, and I want to know why.

Patient: I’m just telling you what I think because you will not change our appointment time.

Therapist: You’ve called me all sorts of names, raised your voice, and kept slamming me with your anger. Why? I want to know why you’re doing this to me?

Patient: I haven’t touched you. I’m just telling you how I feel.

Therapist: I know when I’ve been hit. It hurts. And you’ve laid into me. Why?

Patient: I just got mad about your unwillingness to reschedule.

Therapist: Who taught you to hit when you couldn’t get your way?

Patient: I’ve always done this. I get mad when things don’t go my way.

Therapist: And what happens when you lose it and behave like you’ve just done with me?

Patient: Sometimes I get in real trouble. Like right now, I’ve got to go to court over a stupid fight I had at work. This jerk argued with me over something I told him to do, and I hit him.

Therapist: Just like you did with me when I couldn’t accommodate your schedule-change request.

Patient: Yea.

Therapist: Ever thought about learning to control that anger of yours (beginning the creation of a new Occasion Setter)?

Patient: You mean learning how to be a wimp.

Therapist: No. I mean learning how to behave so you don’t end up in jail for assault and battery.

Patient: I have no idea how I could change….no idea.

Therapist: I know how, and I could teach you how.

Patient: You mean how to react without getting mad.

Therapist: Yea. It would take a lot of work on your part, but I think you could learn. Sure might save you some bitter consequences like facing the court charge. You up to it even though I cannot change my schedule?

Patient: That court date is going to be a mess for me. And, it might really cost me some big bucks or time in jail.

Therapist: You up to learning another way to react to not getting what you want?

Patient: Okay, I’ll try, but I don’t think I can do it.

Therapist: I’ll show you how.

Comment

Clark did learn how to control his anger reactions though it took him four months. We constructed a 5-step acquisition anger-control learning program that consisted of the following steps:

-

1.

Identify a disagreement event or an event where someone does something you don’t like.

-

2.

Count to 10 before you say or do anything.

-

3.

Say a short comment in a calm tone of voice (e.g., “Give me a minute to think about this.”).

-

4.

Ask for more time to think about the event, or say your reaction in a calm voice.

-

5.

Observe the outcome of the disagreement or event.

Therapist: Click the event on this Event Recorder Wrist Band I’m giving you. Wear it at all times during the day. Record the frequency of disagreements each day. As soon as possible, write down the event and how many steps out of five that you successfully accomplished.

Clark and his therapist spent the next four therapy session months reviewing the frequency of disagreement events or events where someone did something he did not like. He wrote the 5-step acquisition learning program steps down on a 3 × 5 card and carried it with him wherever he went. He recorded the frequency of the target events which occurred, and they occurred often for 2–1/2 months. We illustrate Clark’s progress in Fig. 7 with two curves which “summarize” (1) the frequency of disagreement events over months, and (2) his progress at correctly performing the 5-step anger control program. Clark successfully adhered to the program and brought his anger reactions under his control.

Summary

The paper has described a learning theory proposal that we opine may strengthen the effectiveness of Psychological Treatments. Presented was a short review of Learning Theory, and then we showed how early developmental learning may be damaged in toxic parental/caregiver environments and used examples to illustrate how early maladaptive patterns of behavior follow the patient into adulthood. We discussed several learning theory terms and focused particular attention on Bouton’s (2007) Occasion Setters construct. Therapists create new Occasion Setters in the session that facilitate new acquisition learning to counter the old maladaptive patterns. We provided a general Learning Theory definition of Psychological Treatment with six characteristics; then, we described the major features of the Therapist Role—a central teaching feature of our proposal. Finally, we showed how to construct four Learning Theory case examples to modify specific symptom targets. Data examples of the change processes involved in each of the four case symptom targets were presented.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Barlow, D. H. (2004). Psychological treatments. American Psychologist, 59, 869–878.

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford Press.

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1993). Beck anxiety inventory. Harcourt Brace & Company.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). BDI-II manual. Harcourt Brace & Company.

Bouton, M. E. (2007). Learning and behavior: A contemporary synthesis. Sinauer Associates Inc.

Carlson, A. (2012). How parents influence deviant behavior among adolescents: An analysis of their family life, community and peers. Perspectives, vol 4 (6). University of New Hampshire, Scholars Repository. pp 41–51.

Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. L. (1998). The development of depression in children and adolescents. American Psychologist, 53, 221–241.

Eysenck, H.J. (1961). The effects of psychotherapy. In H.J. Eysenck (Ed.) Handbook of Abnormal Behavior. Chapter 18 (pp. 697–725). Basic Books, Inc.

Hammen, C. L., Burge, D., Burney, E., & Adrian, C. (1990). Longitudinal study of diagnoses in children and women with unipolar and bipolar affective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 47, 1112–1117.

Keller, M. B., McCullough, J. P., Jr., Klein, D. N., Arnow, B., Dunner, D. L., Gelenberg, A. J., Markowitz, J., Nemeroff, C. B., Russell, J. M., Thase, M. E., Trivedi, M., & Zajecka, J. (2000). A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. New England Journal Medicine, 342, 1462–1470.

Kiesler, D. J. (1988). Therapeutic metacommunication: Therapist impact disclosure as feedback in psychotherapy. Consulting Psychologist Press.

Kiesler, D. J. (1996). Contemporary interpersonal theory and research: Personality, psychopathology, and psychotherapy. John Wiley.

Kocsis, J. H., Gelenberg, A. J., Rothbaum, B. O., Klein, D. N., Trivedi, M. H., Manber, R., Keller, M. B., Leon, A. C., Wisniewski, S. R., Arnow, B. A., Markowitz, J. C., & Thase, M. E. (2009). Cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy and brief supportive psychotherapy for augmentation of antidepressant nonresponse in chronic depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 1178–1188. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.144

Long, L. R., Foster, M., Burr, K., Penberthy, J. K., Baker, T. N., & McCullough, J. P., Jr. (2023). Pilot study dismantling the cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy: Identifying the active ingredients. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 48, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-024-10467-z

Markowitz, J. C. (2014). What is supportive psychotherapy? Focus, 12, 285–289.

McCullough, J. P. (1984). CBASP: An interactional treatment approach for dysthymia disorder. Psychiatry, 47, 234–250.

McCullough, J. P., Jr. (1991). Psychotherapy for dysthymia: Naturalistic study of ten cases. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 179, 734–740.

McCullough, J. P., Jr. (2000). Treatment for Chronic Depression: Cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy (CBASP). Guilford.

McCullough, J. P., Jr. (2006). Treating Chronic Depression with disciplined personal involvement: CBASP. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-31066-4

McCullough, J. P., Jr., Schramm, E., & Penberthy, J. K. (2015). CBASP as a distinctive treatment for persistent depressive disorder. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2010.64.4.317

Pavlov, I.P. (1927). Conditioned reflexes. (G.V. Anrep, translation). Oxford University Press

Rounsaville, B. J., Carroll, K. M., & Onken, L. S. (2001). A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from Stage I. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 8, 133–142.

Shapiro, M. B. (1961). A method of measuring psychological changes specific to the individual psychiatric patient. British Journal of Medical Psychiatry, 34, 151–155.

Shapiro, M. B. (1964). The measurement of clinically relevant variables. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 8, 245–254.

Shapiro, M. B., Litman, G. K., Nias, D. K. B., & Hendry, E. R. (1973). A clinician’s approach to experimental research. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 29, 165–169.

Sidman, M. (1960). Tactics of scientific research: Evaluating experimental data in psychology. Basic Books Inc.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. Appleton-Century.

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. Macmillan.

Skinner, B. F. (1968). The technology of teaching. Apple-Century-Crofts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

James P. McCullough, Jr. and Lee R. Long declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Animal Rights

There were no animals studied or used in this paper.

Informed Consent

The article was a theoretical paper and no actual humans were involved other than the Author and Co-Author.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McCullough, J.P., Long, L.R. A Learning Theory Proposal that May Strengthen the Effectiveness of Psychological Treatments. Cogn Ther Res (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-024-10508-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-024-10508-7