Abstract

Background

Negative post-traumatic cognitions (PTC) are a risk factor for the development and maintenance of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTC have further been linked to symptoms of depression, anxiety, and emotion regulation (ER). We investigated the role of PTC in the treatment of PTSD patients.

Method

We analyzed data from 339 inpatients (279 female) who received inpatient trauma-focused treatment for eight to twelve weeks. PTC, symptoms of PTSD, depression, anxiety, and ER were assessed at admission and discharge. PTC assessment included negative cognitions about the self, the world, and self-blame.

Results

The results show that all symptoms and ER, and all PTC except for self-blame, decreased during treatment. Only baseline level of PTC about the self was related to changes in depression severity. The other baseline levels of PTC were not related to any changes in symptom severity. Changes in PTC about the self were related to changes in all symptoms and ER. Changes in PTC about the world were only linked to symptoms of PTSD. Changes in self-blame were only associated with symptoms of re-experiencing.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that PTC about the self play a more general and PTC about the world a more specific role in the treatment of PTSD. Further research is needed to clarify the role of self-blame in the treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is estimated that 7 out of 10 people worldwide will experience at least one traumatic event during their lifetime. Amongst those who experience a traumatic event the majority experience more than one, with an average number of three traumatic experiences (Kessler et al., 2017). Nevertheless, only about 6% of trauma survivors develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Koenen et al., 2017), which is a mental illness with debilitating symptoms including re-experiencing (e.g., intrusive thoughts, flashbacks, or nightmares), avoidance (of thoughts and activities that remind of the event), and hyperarousal (Eilers & Rosner, 2021). These symptoms result in significant impairment of personal, social, educational, or occupational functioning (World Health Organization, 2022). Key risk factors for the development of PTSD include trauma severity and lack of social support following the traumatic event (Brewin et al., 2000).

Another central risk factor for developing and maintaining PTSD symptoms are negative posttraumatic cognitions (PTC; Brewin, 2020; Dalgleish, 2004; Ehlers & Clark, 2000; Foa et al., 1999; Meiser-Stedman et al., 2009), also called maladaptive cognitive appraisals (e.g., Agar et al., 2006). PTC include negative cognitions about the world, the self, and self-blame (Agar et al., 2006; Bryant & Guthrie, 2005; Carek et al., 2010). This is reflected in the current fifth edition of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In addition to the three PTSD symptom clusters—re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal—the DSM-5 includes negative alterations in cognitions and mood as a fourth PTSD symptom cluster. Thus, it is important to further examine the role of PTC in PTSD.

There are three theoretical models explaining the mental processes in PTSD, which are highly similar (Brewin & Holmes, 2003): the dual representation theory (Brewin & Burgess, 2014), the emotional processing theory (Rauch & Foa, 2006), and the cognitive model (Ehlers & Clark, 2000). The dual representation theory focuses on how traumatic memories are stored and integrated in the brain. The emotional processing theory emphasizes the importance of processing and integrating emotional responses to the traumatic event and the cognitive model emphasizes the role of negative beliefs and assumptions. Because of the strong overlap between the models, it is difficult to empirically differentiate between them. For illustration of the processes underlying PTSD, we are focusing Ehlers and Clark’s cognitive model, which puts a strong emphasis on the negative beliefs (i.e., PTC) most relevant to the current study.

Ehlers and Clark’s (2000) cognitive model postulates that fear is the result of appraisals related to imminent danger; even though the threat is a memory of a past event, the fear is generalized to the present and leads to avoidance, which in turn perpetuates the threat. PTC about the sequelae of traumatic events can elicit a sense of current threat, which can in turn cause and maintain the symptoms of PTSD (McNally & Woud, 2019). This sense of current threat can be the result of an overgeneralization of the perceived threat to the world (e.g., “The world is a dangerous place.”) or a threat to one’s view of oneself as a capable person (e.g., “I can´t rely on myself.”). PTC pre-existing before the traumatic event, especially about oneself, can promote the development and increase the severity of PTSD symptoms (Bryant & Guthrie, 2007).

The specific role of PTC in PTSD has been examined in a meta-analysis by De la Cuesta and colleagues (2019), which included 135 studies of patients exposed to a traumatic event—as defined in the DSM-5. The meta-analysis supports the association between PTC and PTSD symptoms in patients without treatment. The association had a large effect size (r = 0.53, 95% CI = 0.51–0.56). The largest effect size was found for negative cognitions about the self (r = 0.61), followed by negative cognitions about the world (r = 0.46), and self-blame (r = 0.28). However, the meta-analysis has excluded studies with a sample of patients with a sole PTSD diagnosis or studies of PTSD treatment trials. A review by Brown et al. (2019) investigated the association between changes in PTC and changes in PTSD symptoms in the course of a treatment. The review included 65 studies of trauma-exposed individuals. Most studies have found that a reduction in negative PTC during a treatment was associated with a reduction in PTSD symptoms. This association was further supported by a randomized controlled trial, which investigated the effects of a cognitive bias modification paradigm, an intervention specifically targeting PTC (Woud et al., 2021). In this study of inpatients with PTSD, the reduction of PTC during treatment was uniquely associated with a reduction in PTSD symptoms. This effect has also been shown in an experimental study that exposed healthy participants to distressing films as an analog trauma induction and received positive or negative cognitive bias modification via an app. They found that positive modification of cognitive bias elicited training-congruent judgments compared to negative modification (Würtz et al., 2022). Other studies investigating the direction of the relationship between PTC and PTSD found that changes in PTC preceded changes in PTSD symptoms (Bryant & Guthrie, 2007; Kleim et al., 2013; Kumpula et al., 2017; Schumm et al., 2015; Zalta et al., 2014).

Previous research supports the associations between PTC and the overall PTSD symptom severity. However, there are mixed results about distinct associations between PTC and the different PTSD symptom clusters. In a longitudinal study of sexually abused women, Carper et al. (2015) found that all types of PTC are associated with all three different PTSD symptom clusters. However, studies by Foa and Rauch (2004) and by Raab et al. (2015) discovered that only changes in negative cognitions about the self and the world are related to changes in all three PTSD symptom clusters. In the study by Foa and Rauch (2004), changes in self-blame are only associated with re-experiencing and hyperarousal. Raab et al. (2015) observed that self-blame is only associated with symptoms of re-experiencing and avoidance, but not hyperarousal. The results from another study showed that negative cognitions about the self are associated with all three PTSD symptom clusters but negative cognitions about the world are only associated with avoidance and hyperarousal and not re-experiencing symptoms (Hiskey et al., 2015). In contrast to the two other studies, self-blame is not associated with any of the three PTSD symptom clusters of this study.

PTSD symptoms are often accompanied by symptoms of anxiety, depression, substance abuse (Brady, 2000), and difficulties in emotion regulation (ER; Poole et al., 2018). Therefore, the associations between changes in PTC and changes in these accompanying symptoms should also be investigated. Several studies in the review by Brown et al. (2019) also assessed symptoms of depression (e.g., Kangas et al., 2013; Nacasch et al., 2015; Schumm et al., 2015) and anxiety (e.g., Beck et al., 2016; Kangas et al., 2013). Thus far, only one study by Barlow et al. (2017) has examined the association between PTC and ER strategies, suggesting that there might be a direct link between PTC and PTSD symptoms but also an indirect link via ER (Barlow et al., 2017). According to Gross and John (2003) ER can be divided into cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. Cognitive reappraisal refers to changing the way one thinks about the meaning of a stimulus, whereas expressive suppression refers to the active inhibition of external emotional expression. Previous studies found that expressive suppression is positively associated with PTSD symptoms (Boden et al., 2013; Khan et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2015; Seligowski et al., 2015), whereas cognitive reappraisal is negatively associated with PTSD symptoms (Boden et al., 2013; Khan et al., 2021). The suppression of thoughts and emotions related to the traumatic event corresponds to the avoidance symptom cluster (First, 2013). Furthermore, difficulties in regulating emotions in interpersonal situations can contribute to the development and maintenance of mood and anxiety disorders. The interpersonal model of emotion regulation emphasizes the processes by which interpersonal interactions influence emotional experiences and suggests that interventions that target interpersonal emotion regulation may be effective in treating mood and anxiety disorders (Hofmann, 2014). Thus, ER can be an important factor in the association between PTC and symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Moreover, only one previous study has investigated the association between PTC, ER and PTSD symptoms in a sample of participants who reported childhood abuse (Barlow et al., 2017). The results show that childhood abuse is linked to greater PTSD symptom severity and negative PTC (particularly self-blame) as well as more maladaptive ER.

The Present Study

The current study aimed at deepening our understanding by assessing the association between changes in PTC and changes in symptoms of PTSD, depression, anxiety, and difficulties in ER, during an inpatient PTSD treatment. First, we tested whether symptom severity improved during the psychotherapeutic treatment in a naturalistic clinical care setting. We hypothesized that PTSD-, depression and anxiety symptoms, as well as ER and PTC improve during treatment.

Secondly, we investigated whether the baseline levels of PTC were related to changes in symptoms of PTSD, depression, anxiety and ER. Thus, we tested whether stronger PTC were associated with less changes in symptoms.

Third, we hypothesised that changes in PTC were associated with changes in symptoms of PTSD, depression and anxiety symptoms; similarly to previous studies (Beck et al., 2016; Kangas et al., 2013; Schumm et al., 2015) and to changes in ER. Thus, we tested whether reductions in PTC after treatment were associated with less symptoms and improvements in ER. Further, we hypothesized that changes in PTC about the self were most strongly associated with changes in PTSD symptoms (De La Cuesta et al., 2019).

Method

Participants

We analyzed data from 339 patients (279 women, 60 men). All participants were inpatients in a trauma treatment unit of a psychiatric-psychosomatic hospital in Austria. The hospital requires patients to have a minimum age of eighteen years, a minimum level of conversational skills in German, and be motivated to actively engage in therapy practices. All individuals with acute psychotic symptoms, current suicidal behavior, or acute intoxication are excluded from treatment. Patients are typically referred to treatment by general practitioners, psychiatrists, or other health care professionals. Patients were included in the study if their self-reported PTSD symptoms at admission exceeded a cut-off value of ≥ 45 in the Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist- Civilian Version (PCL-C), which is indicative of PTSD (Karstoft et al., 2014).

Design and Procedure

The current study retrospectively analyzed data collected during routine clinical care using a naturalistic pre-post-study design without a control group. The data was collected between June 2017 and April 2021. At first, the study aimed to examine whether symptom severity (PTSD, anxiety and depression symptoms, PTC, and ER) decreases between admission and discharge. Secondly, we calculated associations between baseline PTC and differences in symptom severity. Thirdly, we compared associations between changes in PTC and changes in symptom severity and ER.

Sociodemographic variables such as age and sex were collected in the hospital information system. All other measures were assessed using the Computer-based Health Evaluation System (Holzner et al., 2012). Participants completed the questionnaires electronically in a computer assessment room with up to seven other participants in separated cubicles. The assessment time at intake and discharge had a duration of two hours each, divided in two one-hour sessions. All participants consented to the processing of the data. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Karl Landsteiner University of Health Sciences (No: 1003/2021) and complies with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki (World-Medical-Association, 2013).

Measures

The German version of the following questionnaires were used to assess PTC, ER and PTSD, depression, and anxiety symptoms, as well as childhood trauma and symptoms of borderline personality disorder (BPD).

Post-traumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI)

The PTCI assessed PTC regarding the traumatic event about the self, the world, and self-blame, within the last month (Foa et al., 1999). Next to a total scale score, three subscale scores for PTC about the self, the world, and self-blame were calculated. Previously, the questionnaire showed acceptable to excellent internal consistency as indicated by a Cronbach´s alpha of αtotal = 0.95, αself = 0.95, αworld = 0.83, and αblame = 0.77 (Müller et al., 2010). In the current study the internal consistency was equally good with αtotal = 0.93, αself = 0.92, αworld = 0.84 and αblame = 0.74.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist—Civilian Version (PCL-C)

The PCL-C assessed symptoms of PTSD within the last month. It consists of three subscales: re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal (Höcker & Mehnert, 2012; Weathers et al., 1994). The total PCL-C score ranges from 17 to 85 (Weathers et al., 1994) and previous research has shown that a cut-off value of 45 or higher indicates a high level of PTSD symptoms (Karstoft et al., 2014).The PCL-C has previously shown excellent internal consistency for the total scale score with α = 0.94 (Conybeare et al., 2012) and acceptable to good internal consistency for the three subscales re-experiencing (α = 0.88), avoidance (α = 0.74) and hyperarousal (α = 0.88; Höcker & Mehnert, 2012). In the present study the internal consistency for the total PCL-C scale and for the re-experiencing subscale was equally good, with α = 0.78 respectively α = 0.81. The internal consistency for the two other subscales was questionable to poor with α = 0.65 for avoidance and α = 0.57 for hyperarousal. However, poor internal consistency is likely due to the fact that the present sample only includes patients with a total PCL-C score of 45 or higher, which limits variance.

Patient Health Questionnaire—Depression Module (PHQ-9)

Depression symptoms in the last two weeks were assessed with the German version of the PHQ-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001a). In previous studies the PHQ-9 showed good internal consistency (α = 0.86; Beard et al., 2016) and test–retest reliability (r = 0.84; Kroenke et al., 2001b), good convergent and discriminant validity and good sensitivity to change. To detect major depressive disorder (MDD), a cut-off score of ≥ 10 has a sensitivity and specificity of 88% each (Manea et al., 2012). The German version showed excellent psychometric properties with α = 0.90 (Reich et al., 2018). In the current study internal consistency was also good with α = 0.80.

Patient Health Questionnaire—Anxiety module (GAD-7)

The GAD-7 was used to assess the level of symptoms of Generalized Anxiety in the last 2 weeks. Williams (2014) suggest a score of 10, with a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 82%, to detect moderate anxiety disorder. The internal consistency of the GAD-7 has previously been reported as excellent (α = 0.92) and the test–retest reliability as good (r = 0.83; Spitzer et al., 2006). The German version showed similarly good psychometric properties with α = 0.85 (Hinz et al., 2017). In the present study the internal consistency was also good with α = 0.80.

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ)

The ERQ measured emotion regulation strategies and consists of two subscales: cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression (Gross & John, 2003). Previous research showed good internal consistency for the cognitive reappraisal (α = 0.89–0.90) and acceptable internal consistency for the expressive suppression (α = 0.76–0.80) subscale (Preece et al., 2020). The German version showed similar psychometric properties for reappraisal (α = 0.82) and suppression (α = 0.76; Wiltink et al., 2011). In the current study only the reappraisal subscale showed good internal consistency (α = 0.86), the internal consistency of the suppression subscale was questionable (α = 0.66).

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ)

The CTQ is a retrospective measure for childhood maltreatment in adults (Bernstein et al., 2003). The questionnaire uses 28 items to assess five types of childhood trauma: sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect. In addition to the scores for the five subscales a combined total score can be calculated. In previous studies the German version of the CTQ has shown good to excellent internal consistency (αtotal = 0.94, αemotional abuse = 0.89, αphysical abuse = 0.89, αsexual abuse = 0.96, αemotional neglect = 0.90, and αphysical neglect = 0.62) and good construct validity (Wingenfeld et al., 2010). In the current study the internal consistency ranged from excellent to questionable depending on the subscale, with αtotal = 0.91, αemotional abuse = 0.87, αphysical abuse = 0.9, αsexual abuse = 0.97, αemotional neglect = 0.60 and αphysical neglect = 0.75.

McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD)

The MSI-BPD assessed symptoms of BPD (Zanarini et al., 2003). The original English version showed acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.74), test–retest reliability (rs = 0.72), good validity, and diagnostic accuracy (Chanen et al., 2008; Noblin et al., 2013; Patel et al., 2011; Zanarini et al., 2003). The German version performed equally well with α = 0.96 (Kröger et al., 2010, 2011). The internal consistency in the current study was poor (α = 0.65).

Sociodemographic Variables

Sex (male, female) was defined in terms of the self-reported sex. Age refers to the chronological age (in years) at the time of admission. Education level was assessed based on the Austrian school system and later categorized into the following three education levels: (1) low education level (i.e., compulsory school education), (2) medium education level (i.e., secondary school education), and (3) high education level (i.e., college education).

Treatment

Participants received an eclectic mixture of trauma-focused therapy. Treatment was delivered in both individual and group settings by an interdisciplinary team and was heterogeneous between patients. Specific treatment protocols and elements included Dialectic Behavior Therapy for PTSD, Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), Imagery Rescripting & Reprocessing Therapy (IRRT), Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT), Imagery Rehearsal Therapy (IRT), Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET), Concept of Structural Dissociation (Enactive Trauma Therapy), Somatic Experiencing, Neuroaffective Relational Model (NARM), and Schema Therapy.

Treatment was chosen based on therapist’s expertise and preferences. The mandatory group therapy sessions included open-topic groups, knowledge transfer, mindfulness training group, and skills training group, each lasting 50 min per week. Additional group therapies included art therapy, music therapy, group biofeedback and animal-assisted therapy. Patients participated in group therapy about 10 times per week and received two one-hour individual psychotherapy sessions per week. Most patients stayed for eight weeks, with a range of one to 13 weeks.

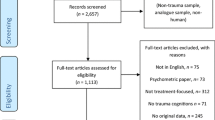

Statistical Analysis

All analyses used data with single imputations to account for missing values in questionnaires. Missing values were replaced with the mean score of the respective scale if less than 20% of the responses per scale were missing. Patients with more than 20% missing values were excluded from the analysis. Supplementary Fig. 1 displays the percentage of missing data before imputation at admission and discharge. Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 display correlations between PTC, symptoms of depression, anxiety and PTSD, and emotion regulation, at the times of admission and discharge, respectively.

First, we tested for changes between admission and discharge. To test these changes, we conducted paired-sample t-tests for all 13 measures and reported Cohen’s d effect sizes (with pooled standard deviations). To control for multiple testing, Bonferroni correction was used lowering the significance level to p ≤ 0.004. We conducted these t-Tests first, using addressing a completer sample and secondly, an intent-to-treat analysis (ITT). In the completer sample participants were only included if they provided data for both measurement points. We additionally applied the last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) method in line with ITT replacing missing values at discharge with values from admission of that particular person (= the last observation is carried forward). This method is a commonly used statistical approach for analyzing longitudinal data with repeated measures when data are missing (Lachin, 2016). It is the most conservative method for participant attrition in an intent-to-treat analysis (ITT).

Secondly, we examined the associations between PTC at admission and changes in symptoms. We only included PTC subscales, not summed PTC data. Symptoms referred to PTSD, depression, anxiety, and ER strategies. We calculated eight multiple linear regressions, with the three PTC subscales at admission as predictors, controlling for gender and age, and the respective change scores of the symptoms as exploratory variables.

Thirdly, we calculated the associations between changes in PTC and changes in symptoms..Again, we only included PTC subscales, not summed PTC data. We calculated eight multiple linear regressions, with the change scores of the three PTC subscales as predictors, controlling for gender and age and change scores of symptoms of PTSD, depression and anxiety and ER as exploratory variables.

Results

First, we describe the sample characteristics. Then we present descriptive statistics of all measures at admission, discharge, and the intent-to-treat sample with the LOCF method. Subsequently, we compare changes in all measures between admission and discharge and between admission and intent-to-treat (LOCF) with paired sample t-tests. Finally, we analyze the connections between PTC at admission and changes in symptoms of PTSD, depression and anxiety and ER as well as changes in PTC and changes in symptoms of PTSD, depression and anxiety, and ER with multiple linear regression analyses (Table 1).

Sample Characteristics

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 displays means and standard deviations of all measures at the times of admission and discharge as well as for the intent-to-treat analysis (LOCF method). The absence of discharge assessment data is either due to dropout or because of administrative and clinical reasons (e.g., they were discharged before the assessment was scheduled, holidays, scheduling conflict, sick leave of testing stuff, therapists felt that the patients were still too distressed to complete the discharge assessment).

Changes in the Course of Treatment

We used t-tests to assess changes between admission and discharge (see Table 3). There was a significant change in the PTCI total score and the two subscales negative cognitions about the world and the self with medium effect sizes. Self-blame did not show a significant change. PTSD symptoms had significantly improved in the course of treatment with medium effect sizes for the total PCL-C sum score, the PCL-C subscales avoidance and hyperarousal and low effect sizes for the re-experiencing subscale.

In the PCL-C sum score, a decrease of at least 5 points indicates a reliable improvement and a decrease of at least 10 points indicates a clinically significant improvement in PTSD symptoms. In our sample, only 121 (54%) participants had decreased at least 5 points and only 77 (34%) had decreased at least 10 points. Moreover, at the time of discharge 88.50% of patients still had a PCL-C score of 45 or higher indicating a high level of PTSD severity.

Depression and anxiety severity, ER strategies and BPD symptom severity all significantly improved in the course of treatment with high effect sizes for depression severity, medium effect sizes for anxiety severity and BPD symptoms, and low effect sizes for ER strategies. Table 3 presents patients who scored above the cut-off of 10 on the PHQ-9, indicating a moderate level of depression (Kroenke et al., 2001a). Further, the presented GAD-7 ≥ 10 indicated a moderate level of anxiety severity (Spitzer et al., 2006). Moreover, patients who had a MSI-BPD score of 7 or higher showed comorbid BPD symptomatology (Zanarini et al., 2003).

Regarding changes in depression severity, only 111 participants (45%) changed at least 5-points, which would indicate a reliable improvement (McMillan et al., 2010). Regarding anxiety symptoms, only 62 participants (26%) had reliably improved in the GAD-7 score, as indicated by a minimum change of 6-points (Bischoff et al., 2020). Concerning changes in ER strategies, the participants’ use of reappraisal increased, whereas the use of suppression of emotions decreased in the course of treatment.

The intent-to-treat data (LOCF) showed similar results for t-tests comparing the measures of PTC and symptoms of PTSD, depression and anxiety and ER between admission and discharge (see Table 4). Regarding the PTCI there was a significant change in the PTCI sum score as well as the subscales negative cognitions about the self and about the world (with small effect sizes), but no significant change for the PTCI subscale self-blame. PTSD symptoms significantly improved with medium effect sizes for the PCL-C sum score and low effect sizes for the three PCL-C subscales (re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal). Symptom severity of depression and anxiety, ER strategies, and BPD symptom severity all significantly improved in the intent-to-treat analysis with medium effect sizes for depression and anxiety severity and low effect sizes for ER strategies and BPD symptom severity.

Relationship Between PTC and Symptoms of PTSD, Depression and Anxiety, and ER

To assess the relationship between PTC and symptoms of PTSD, depression, anxiety, and ER, we calculated two sets of eight multiple linear regression analyses. Table 5 displays the results of our first set with baseline levels of PTCI as predictors and the changes in PCL-C-, PHQ-9-, GAD-7- and ERQ scores as explanatory variables. The PTCI subscale self-blame at admission was significantly associated with changes in depression severity. However, there were no other significant associations between the PTCI scale scores at admission and changes in any of the above measures.

Table 6 shows the results of the second set of regression analyses with changes in the PTCI scores as predictor variables and changes in PCL-C, PHQ-9, GAD-7 and ERQ scores as explanatory variables. Changes in the PTCI subscale negative cognitions about the self were significantly associated with changes in all the above measures. Changes in the PTCI subscale negative cognitions about the world were significantly associated with all PCL-C scores, except re-experiencing. The PTCI subscale self-blame was only significantly associated with the PCL-C subscale re-experiencing but not with any of the other measures. However, the change in the PTCI subscale self-blame was not significant (see Tables 2, 3, 4).

Discussion

This study has investigated the role of PTC on treatment outcomes of inpatients with PTSD. We were especially interested in the distinct association between PTC subscales and different PTSD symptom clusters. Additionally, we focused on the role of PTC for symptoms of depression and anxiety as well as ER strategies during treatment.

First, analyses of the treatment completers show that, except for self-blame, the other PTC (i.e., negative cognitions about the world and about the self) as well as symptoms of PTSD, depression and anxiety and ER strategies have improved between admission and discharge. The analyses using the last observation carried-forward method show the same results. Thus, regardless of selective drop-out, symptom severity improves in the course of the inpatient treatment. Hence, the eclectic trauma-focused treatment is likely to have resulted in an improvement of symptoms. This is in line with previous evidence for the effectiveness of trauma focused treatments regarding PTSD (e.g., Ehring et al., 2014; Schnurr, 2017), symptoms of depression (e.g., Ehring et al., 2008; Schumm et al., 2015), anxiety (e.g., Beck et al., 2016; Littleton et al., 2012) and ER (van Toorenburg et al., 2020). The interpretation of the current data is limited by the absence of a control group.

Although PTSD symptoms as well as symptoms of depression have improved significantly in the current study, these improvements are not reliably or clinically significant for the majority of the patients. This is indicated by the small percentage of patients for whom the improvement is above the level of the reliable change index (RCI). Unfortunately, this also suggests that there may not have been sustained improvement in PTSD symptoms in the patient group. Thus, although the eclectic inpatient trauma-focused treatment in the present study has led to a statistically significant symptom reduction, it is unclear if symptoms have been reduced sufficiently to induce sustained improvements. The relatively small effect sizes stand in contrast to the resource heavy eight-week inpatient treatment, which included two individual and 10 group therapy sessions per week. However, the effect sizes are comparable to the results of a meta-analysis on the improvement of symptom severity of inpatient psychiatric-psychosomatic rehabilitation (Sprung et al., 2018). Secondly, we have investigated associations between baseline levels of PTC on symptom changes. Only the level of negative cognitions about the self at admission is related to changes in symptoms of depression. This is unsurprising given that negative cognitions about the self include feelings of hopelessness, sadness, and the inability to cope with situations, as well as self-doubt, which are akin to a depressive thinking style. The absence of significant associations between the PTC subscales negative cognitions about the world and self-blame and symptom change might have resulted from sample characteristics. We have only included patients with PTSD, therefore the variance in PTSD symptoms may be limited, which could have influenced the analyses. In fact, the meta-analysis by De la Cuesta et al. (2019) excluded studies with an all PTSD patient sample due to the limited variance in PTSD symptoms.

Thirdly, we have assessed the association between changes in PTC and changes in symptoms of PTSD, depression, anxiety, and ER. The changes during treatment are significantly associated with changes in PTC. The results are in line with previous findings that show that PTC change with PTSD symptoms (e.g., Brown et al., 2019; De La Cuesta et al., 2019). Previous studies found that changes in PTC are associated with changes in PTSD (e.g., Ehring et al., 2014; Schnurr, 2017) changes in symptoms of depression (e.g., Ehring et al., 2008; Schumm et al., 2015) and anxiety (e.g., Beck et al., 2016; Kangas et al., 2013; Littleton et al., 2012); the current data replicates these findings. Additionally, changes in PTC are associated with changes in ER. Notably, the results support previous evidence that changes in negative cognitions about the self are most strongly related to reductions in PTSD symptoms (De La Cuesta et al., 2019; Foa & Rauch, 2004; Nacasch et al., 2015).

Negative cognitions about the self are also associated with changes in symptoms of depression and anxiety and are related to changes in ER. This suggests that the influence of negative cognitions about the self may go beyond symptom reduction and may also foster skill development—possibly because reducing negative cognitions about the self may in turn foster self-competence. In contrast, changes in negative cognitions about the world are only related to changes in symptoms of PTSD. This suggests that there might be a specific link between negative cognitions about the world and symptoms of PTSD. Changes in self-blame are only associated with changes in re-experiencing. However, self-blame has not changed significantly during treatment, thus this association is unlikely to be the result of a successful treatment of self-blame. There is contradictory evidence for the role of self-blame in PTSD treatment, even though some studies found an improvement during treatment (Beck et al., 2016; Schumm et al., 2015), the majority of studies have not (e.g., Carper et al., 2015; Foa & Rauch, 2004; Foa et al., 2005; Gray et al., 2012; Kumpula et al., 2017; McLean et al., 2019). These contradictions might have resulted from differences in the intervention programs. Since there is a great variability in treatment and treatment dose in the present sample, this might as well contribute to the finding that self-blame has not changed significantly during treatment.

A limitation of the study is that no structured diagnostic interviews were used to determine diagnoses. However, using the scores from the PCL-C allows to reliably distinguish between traumatised and non-traumatised individuals (Gelaye et al., 2017). The study is limited to measuring different types of childhood abuse but has not captured traumatic experiences in adulthood. Thus, we were not able to address the effects of different types of traumatic experiences in adulthood. Future studies should include structured assessments of the type of traumatic experiences to determine if there are differences in the associations between PTC and PTSD symptoms depending on the type of traumatic experience. Another limitation of the current study is that we have not included a control group. It is, thus, possible that changes over time in PTC may occur even without an intervention, however, the study is highly relevant to evaluate effects in a naturalistic clinical care setting. Notably, the patients in the current study have not received a uniform treatment program. Depending on the decisions of their respective therapists, they have received different treatments and therefore showed great variability in treatment and treatment dose. Some symptoms may improve with higher session frequency or different treatment. Moreover, the treatment may have been too eclectic; a solely trauma-focused CBT approach might have produced better results. Another study investigating the effects of a treatment that specifically targeted PTC using a cognitive bias modification paradigm has found that such a training can significantly improve PTC (Woud et al., 2021). However, treatment effects have not lasted until follow-up. In contrast, another study showed that adding specific cognitive interventions has not increased changes in PTC (Foa et al., 2005). Hence there might not be a need to specifically target PTC in the treatment. Further studies need to be conducted regarding these mixed results. Moreover, future studies should investigate changes in interpersonal ER (Hofmann, 2014) in response to PTSD treatment.

In summary, the present findings confirm the decrease in symptom severity and PTC during inpatient trauma-focused treatment, except for the PTC self-blame. The data show that only baseline level of PTC about the self are related to changes in depression severity. Baseline level of PTC about the world and self-blame are not associated with changes in symptom severity. The data also supports that PTC and symptoms of PTSD, depression and anxiety, and ER change with trauma-focused treatments. Particularly, reductions in negative cognitions about the self change with all symptoms and ER. Reductions in negative cognitions about the world are only linked to changes in symptoms of PTSD and Changes in self-blame are only associated with symptoms of re-experiencing. These general reductions of symptoms may be caused by the same processes. The model by Ehlers and Clark (2000) assumes that PTSD is caused by generalizing past fears about the traumatic event to the present. A treatment that successfully reduces PTC might imply that these fears (i.e., negative thoughts) are no longer generalized into the present and as a result symptoms of depression and anxiety might cease.

Given the mixed findings on the effectiveness of PTSD interventions that target PTC (Foa & Rauch, 2004; Woud et al., 2021) future studies should compare the effects of different treatments on PTSD. Further, the role of self-blame in PTSD treatment should be clarified (e.g., Carper et al., 2015; Raab et al., 2015). Specifically targeting self-blame during treatment and assessing PTC as well as PTSD symptoms on three different measurement points (pre and post-appraisal training and follow-up) would help to further investigate the causality and the direction of this underlying mechanism.

References

Agar, E., Kennedy, P., & King, N. S. (2006). The role of negative cognitive appraisals in PTSD symptoms following spinal cord injuries. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 34(04), 437. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465806002943

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, Hrsg. 5th ed). American Psychiatric Association.

Barlow, M. R., Goldsmith Turow, R. E., & Gerhart, J. (2017). Trauma appraisals, emotion regulation difficulties, and self-compassion predict posttraumatic stress symptoms following childhood abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 65, 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.01.006

Beard, C., Hsu, K. J., Rifkin, L. S., Busch, A. B., & Björgvinsson, T. (2016). Validation of the PHQ-9 in a psychiatric sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 193, 267–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.075

Beck, J. G., Tran, H. N., Dodson, T. S., Henschel, A. V., Woodward, M. J., & Eddinger, J. (2016). Cognitive trauma therapy for battered women: Replication and extension. Psychology of Violence, 6(3), 368–377. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000024

Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., Stokes, J., Handelsman, L., Medrano, M., Desmond, D., & Zule, W. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

Bischoff, T., Anderson, S. R., Heafner, J., & Tambling, R. (2020). Establishment of a reliable change index for the GAD-7. Psychology, Community & Health, 8(1), 176–187. https://doi.org/10.5964/pch.v8i1.309

Boden, M. T., Westermann, S., McRae, K., Kuo, J., Alvarez, J., Kulkarni, M. R., Gross, J. J., & Bonn-Miller, M. O. (2013). Emotion regulation and posttraumatic stress disorder: A prospective investigation. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 32(3), 296–314. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2013.32.3.296

Brady, K. T., Killeen, T. K., Brewerton, T., & Lucerini, S. (2000). Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61(Suppl 7), 22–32.

Brewin, C. R. (2020). Complex post-traumatic stress disorder: A new diagnosis in ICD-11. Bjpsych Advances, 26(3), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2019.48

Brewin, C. R., Andrews, B., & Valentine, J. D. (2000). Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(5), 748–766. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.748

Brewin, C. R., & Burgess, N. (2014). Contextualisation in the revised dual representation theory of PTSD: A response to Pearson and colleagues. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 45(1), 217–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.07.011

Brewin, C. R., & Holmes, E. A. (2003). Psychological theories of posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 23(3), 339–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(03)00033-3

Brown, L. A., Belli, G. M., Asnaani, A., & Foa, E. B. (2019). A review of the role of negative cognitions about oneself, others, and the world in the treatment of PTSD. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 43(1), 143–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-018-9938-1

Bryant, R. A., & Guthrie, R. M. (2005). Maladaptive appraisals as a risk factor for posttraumatic stress: A study of trainee firefighters. Psychological Science, 16(10), 749–752. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01608.x

Bryant, R. A., & Guthrie, R. M. (2007). Maladaptive self-appraisals before trauma exposure predict posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(5), 812–815. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.812

Carek, V., Norman, P., & Barton, J. (2010). Cognitive appraisals and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in informal caregivers of stroke survivors. Rehabilitation Psychology, 55(1), 91–96. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018417

Carper, T. L., Mills, M. A., Steenkamp, M. M., Nickerson, A., Salters-Pedneault, K., & Litz, B. T. (2015). Early PTSD symptom sub-clusters predicting chronic posttraumatic stress following sexual assault. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 7(5), 442–447. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000060

Chanen, A. M., Jovev, M., Djaja, D., McDougall, E., Yuen, H. P., Rawlings, D., & Jackson, H. J. (2008). Screening for borderline personality disorder in outpatient youth. Journal of Personality Disorders, 22(4), 353–364. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2008.22.4.353

Conybeare, D., Behar, E., Solomon, A., Newman, M. G., & Borkovec, T. D. (2012). The PTSD checklist-civilian version: Reliability, validity, and factor structure in a nonclinical sample: PCL-C in a nonclinical sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(6), 699–713. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21845

Dalgleish, T. (2004). Cognitive approaches to posttraumatic stress disorder: The evolution of multirepresentational theorizing. Psychological Bulletin, 130(2), 228–260. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.228

De La Cuesta, G., Schweizer, S., Diehle, J., Young, J., & Meiser-Stedman, R. (2019). The relationship between maladaptive appraisals and posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1620084. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1620084

Ehlers, A., & Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(4), 319–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00123-0

Ehring, T., Ehlers, A., & Glucksman, E. (2008). Do cognitive models help in predicting the severity of posttraumatic stress disorder, phobia, and depression after motor vehicle accidents? A prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.219

Ehring, T., Welboren, R., Morina, N., Wicherts, J. M., Freitag, J., & Emmelkamp, P. M. G. (2014). Meta-analysis of psychological treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder in adult survivors of childhood abuse. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(8), 645–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.10.004

Eilers, R., & Rosner, R. (2021). Die einfache und komplexe Posttraumatische Belastungsstörung in der Praxis: Eine Übersicht und Einordnung der neuen ICD-11 Kriterien in Bezug auf Kinder und Jugendliche. Kindheit Und Entwicklung, 30(3), 144–153. https://doi.org/10.1026/0942-5403/a000342

First, M. B. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edtition and clinical utility. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 201(9), 727–729. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182a2168a

Foa, E. B., Ehlers, A., Clark, D. M., Tolin, D. F., & Orsillo, S. M. (1999). The posttraumatic cognitions inventory (PTCI): Development and validation. Psychological Assessment, 11(3), 303–314. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.11.3.303

Foa, E. B., Hembree, E. A., Cahill, S. P., Rauch, S. A. M., Riggs, D. S., Feeny, N. C., & Yadin, E. (2005). Randomized trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: Outcome at academic and community clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(5), 953–964. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.953

Foa, E. B., & Rauch, S. A. M. (2004). Cognitive changes during prolonged exposure versus prolonged exposure plus cognitive restructuring in female assault survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(5), 879–884. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.879

Gelaye, B., Zheng, Y., Medina-Mora, M. E., Rondon, M. B., Sánchez, S. E., & Williams, M. A. (2017). Validity of the posttraumatic stress disorders (PTSD) checklist in pregnant women. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 179. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1304-4

Gray, M. J., Schorr, Y., Nash, W., Lebowitz, L., Amidon, A., Lansing, A., Maglione, M., Lang, A. J., & Litz, B. T. (2012). Adaptive disclosure: An open trial of a novel exposure-based intervention for service members with combat-related psychological stress injuries. Behavior Therapy, 43(2), 407–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.09.001

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

Hofmann, S. G. (2014). Interpersonal emotion regulation model of mood and anxiety disorders. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 38(5), 483–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-014-9620-1

Hinz, A., Klein, A. M., Brähler, E., Glaesmer, H., Luck, T., Riedel-Heller, S. G., Wirkner, K., & Hilbert, A. (2017). Psychometric evaluation of the generalized anxiety disorder screener GAD-7, based on a large German general population sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 210, 338–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.012

Hiskey, S., Ayres, R., Andrews, L., & Troop, N. (2015). Support for the location of negative posttraumatic cognitions in the diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder. Personality and Individual Differences, 74, 192–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.10.021

Höcker, A., & Mehnert, A. (2012). Posttraumatische Belastung bei Krebspatienten: Validierung der deutschen Version der Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist—Civilian Version (PCL-C): Posttraumatic stress in cancer patients: Validation of the German Version of the PTSD Checklist—Civilian Version (PCL-C). Zeitschrift Für Medizinische Psychologie, 21(2), 68–79. https://doi.org/10.3233/ZMP-2012-210003

Holzner, B., Giesinger, J. M., Pinggera, J., Zugal, S., Schöpf, F., Oberguggenberger, A. S., Gamper, E. M., Zabernigg, A., Weber, B., & Rumpold, G. (2012). The computer-based health evaluation software (CHES): A software for electronic patient-reported outcome monitoring. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 12(1), 126. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-12-126

Kangas, M., Milross, C., Taylor, A., & Bryant, R. A. (2013). A pilot randomized controlled trial of a brief early intervention for reducing posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depressive symptoms in newly diagnosed head and neck cancer patients: Early CBT for PTSD, anxiety and depressive symptoms for HNC. Psycho-Oncology, 22(7), 1665–1673. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3208

Karstoft, K.-I., Andersen, S. B., Bertelsen, M., & Madsen, T. (2014). Diagnostic accuracy of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist-civilian version in a representative military sample. Psychological Assessment, 26(1), 321–325. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034889

Kessler, R. C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Bromet, E. J., Cardoso, G., Degenhardt, L., de Girolamo, G., Dinolova, R. V., Ferry, F., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Huang, Y., Karam, E. G., Kawakami, N., Lee, S., Lepine, J.-P., Levinson, D., & Koenen, K. C. (2017). Trauma and PTSD in the WHO world mental health surveys. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup5), 1353383. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383

Khan, A. J., Maguen, S., Straus, L. D., Nelyan, T. C., Gross, J. J., & Cohen, B. E. (2021). Expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal in veterans with PTSD: Results from the mind your heart study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 283, 278–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.015

Kleim, B., Grey, N., Wild, J., Nussbeck, F. W., Stott, R., Hackmann, A., Clark, D. M., & Ehlers, A. (2013). Cognitive change predicts symptom reduction with cognitive therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(3), 383–393. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031290

Koenen, K. C., Ratanatharathorn, A., Ng, L., McLaughlin, K. A., Bromet, E. J., Stein, D. J., Karam, E. G., Meron Ruscio, A., Benjet, C., Scott, K., Atwoli, L., Petukhova, M., Lim, C. C. W., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Alonso, J., Bunting, B., Ciutan, M., de Girolamo, G., & Kessler, R. C. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the world mental health surveys. Psychological Medicine, 47(13), 2260–2274. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717000708

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001a). The PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001b). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Kröger, C., Huget, F., & Roepke, S. (2011). Diagnostische Effizienz des McLean Screening Instrument für Borderline-Persönlichkeitsstörung in einer Stichprobe, die eine stationäre, störungsspezifische Behandlung in Anspruch nehmen möchte. Psychotherapie Psychosomatik Medizinische, 61(11), 481–486. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1291275

Kröger, C., Vonau, M., Kliem, S., & Kosfelder, J. (2010). Screening-Instrument für die Borderline-Persönlichkeitsstörung Diagnostische Effizienz der deutschen Version des McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder. Psychotherapie Psychosomatik Medizinische, 60(10), 391–396. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1248279

Kumpula, M. J., Pentel, K. Z., Foa, E. B., LeBlanc, N. J., Bui, E., McSweeney, L. B., Knowles, K., Bosley, H., Simon, N. M., & Rauch, S. A. M. (2017). Temporal sequencing of change in posttraumatic cognitions and PTSD symptom reduction during prolonged exposure therapy. Behavior Therapy, 48(2), 156–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2016.02.008

Lachin, J. M. (2016). Fallacies of last observation carried forward analyses. Clinical Trials, 13(2), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/1740774515602688

Lee, D. J., Witte, T. K., Weathers, F. W., & Davis, M. T. (2015). Emotion regulation strategy use and posttraumatic stress disorder: Associations between multiple strategies and specific symptom clusters. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 37(3), 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-014-9477-3

Littleton, H., Buck, K., Rosman, L., & Grills-Taquechel, A. (2012). From survivor to thriver: A pilot study of an online program for rape victims. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(2), 315–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.04.002

Manea, L., Gilbody, S., & McMillan, D. (2012). Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9): A meta-analysis. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 184(3), E191–E196. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.110829

McLean, C. P., Zang, Y., Gallagher, T., Suzuki, N., Yarvis, J. S., Litz, B. T., Mintz, J., Young-McCaughan, S., Peterson, A. L., & Foa, E. B. (2019). Trauma-related cognitions and cognitive emotion regulation as mediators of PTSD change among treatment-seeking active-duty military personnel with PTSD. Behavior Therapy, 50(6), 1053–1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2019.03.006

McMillan, D., Gilbody, S., & Richards, D. (2010). Defining successful treatment outcome in depression using the PHQ-9: A comparison of methods. Journal of Affective Disorders, 127(1–3), 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.030

McNally, R. J., & Woud, M. L. (2019). Innovations in the study of appraisals and PTSD: A commentary. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 43(1), 295–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-018-09995-2

Meiser-Stedman, R., Dalgleish, T., Glucksman, E., Yule, W., & Smith, P. (2009). Maladaptive cognitive appraisals mediate the evolution of posttraumatic stress reactions: A 6-month follow-up of child and adolescent assault and motor vehicle accident survivors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(4), 778–787. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016945

Müller, J., Wessa, M., Rabe, S., Dörfel, D., Knaevelsrud, C., Flor, H., Maercker, A., & Karl, A. (2010). Psychometric properties of the posttraumatic cognitions inventory (PTCI) in a German sample of individuals with a history of trauma. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 2(2), 116–125. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018603

Nacasch, N., Huppert, J. D., Su, Y.-J., Kivity, Y., Dinshtein, Y., Yeh, R., & Foa, E. B. (2015). Are 60-minute prolonged exposure sessions with 20-minute imaginal exposure to traumatic memories sufficient to successfully treat PTSD? A randomized noninferiority clinical trial. Behavior Therapy, 46(3), 328–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2014.12.002

Noblin, J. L., Venta, A., & Sharp, C. (2013). The validity of the MSI-BPD among inpatient adolescents. Assessment, 21(2), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191112473177

Patel, A. B., Sharp, C., & Fonagy, P. (2011). Criterion validity of the MSI-BPD in a community sample of women. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 33(3), 403–408.

Poole, J. C., Dobson, K. S., & Pusch, D. (2018). Do adverse childhood experiences predict adult interpersonal difficulties? The role of emotion dysregulation. Child Abuse & Neglect, 80, 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.006

Preece, D. A., Becerra, R., Robinson, K., & Gross, J. J. (2020). The emotion regulation questionnaire: Psychometric properties in general community samples. Journal of Personality Assessment, 102(3), 348–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2018.1564319

Raab, P. A., Mackintosh, M.-A., Gros, D. F., & Morland, L. A. (2015). Examination of the content specificity of posttraumatic cognitions in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry, 78(4), 328–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.2015.1082337

Rauch, S., & Foa, E. (2006). Emotional processing theory (EPT) and exposure therapy for PTSD. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 36(2), 61–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-006-9008-y

Reich, H., Rief, W., Brähler, E., & Mewes, R. (2018). Cross-cultural validation of the German and Turkish versions of the PHQ-9: An IRT approach. BMC Psychology, 6(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-018-0238-z

Schnurr, P. P. (2017). Focusing on trauma-focused psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Current Opinion in Psychology, 14, 56–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.11.005

Schumm, J. A., Dickstein, B. D., Walter, K. H., Owens, G. P., & Chard, K. M. (2015). Changes in posttraumatic cognitions predict changes in posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms during cognitive processing therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(6), 1161–1166. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000040

Seligowski, A. V., Lee, D. J., Bardeen, J. R., & Orcutt, H. K. (2015). Emotion regulation and posttraumatic stress symptoms: A meta-analysis. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 44(2), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2014.980753

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

van Toorenburg, M. M., Sanches, S. A., Linders, B., Rozendaal, L., Voorendonk, E. M., Van Minnen, A., & De Jongh, A. (2020). Do emotion regulation difficulties affect outcome of intensive trauma-focused treatment of patients with severe PTSD? European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1724417. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1724417

Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Herman, D., Huska, J., & Keane, T. (1994). The PTSD checklist-civilian version (PCL-C) (p. 10). National Center for PTSD.

Williams, N. (2014). The GAD-7 questionnaire. Occupational Medicine, 64(3), 224–224. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqt161

Wiltink, J., Glaesmer, H., Canterino, M., Wölfling, K., Knebel, A., Kessler, H., Brähler, E., & Beutel, M. E. (2011). Regulation of emotions in the community: Suppression and reappraisal strategies and its psychometric properties. GMS Psycho-Social-Medicine. https://doi.org/10.3205/PSM000078

Wingenfeld, K., Spitzer, C., Mensebach, C., Grabe, H. J., Hill, A., Gast, U., Schlosser, N., Höpp, H., Beblo, T., & Driessen, M. (2010). Die deutsche Version des Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ): Erste Befunde zu den psychometrischen Kennwerten. Psychotherapie Psychosomatik Medizinische, 60(11), 442–450. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1247564

World Health Organization. (2022). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th ed.). https://icd.who.int/

World-Medical-Association. (2013). World medical association declaration of helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053

Woud, M. L., Blackwell, S. E., Shkreli, L., Würtz, F., Cwik, J. C., Margraf, J., Holmes, E. A., Steudte-Schmiedgen, S., Herpertz, S., & Kessler, H. (2021). The effects of modifying dysfunctional appraisals in posttraumatic stress disorder using a form of cognitive bias modification: Results of a randomized controlled trial in an inpatient setting. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 90(6), 386–402. https://doi.org/10.1159/000514166

Würtz, F., Krans, J., Blackwell, S. E., Cwik, J. C., Margraf, J., & Woud, M. L. (2022). Using cognitive bias modification-appraisal training to manipulate appraisals about the self and the world in analog trauma. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 46(1), 232–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-021-10257-x

Zalta, A. K., Gillihan, S. J., Fisher, A. J., Mintz, J., McLean, C. P., Yehuda, R., & Foa, E. B. (2014). Change in negative cognitions associated with PTSD predicts symptom reduction in prolonged exposure. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(1), 171–175. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034735

Zanarini, M. C., Vujanovic, A. A., Parachini, E. A., Boulanger, J. L., Frankenburg, F. R., & Hennen, J. (2003). A screening measure for BPD: The McLean screening instrument for borderline personality disorder (MSI-BPD). Journal of Personality Disorders, 17(6), 568–573. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.17.6.568.25355

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karl Landsteiner Privatuniversität für Gesundheitswissenschaften. Funding was provided by Gesellschaft für Forschungsförderung Niederösterreich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

The present study is a retrospective analysis of data collected during routine clinical care. The analysis was approved by the ethics commission of the Karl Landsteiner University of Health Sciences (Nr: 1020/2021).

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants and the study follows the ethical standards proposed in the Declaration of Helsinki (54). All participants consented to the use of their data.

Animal Rights

No animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gradl, S., Burghardt, J., Oppenauer, C. et al. The Role of Negative Posttraumatic Cognitions in the Treatment of Patients with Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. Cogn Ther Res 47, 851–864 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-023-10397-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-023-10397-2