Summary

Purpose

The present study investigated the interactions between emotion regulation strategies and cognitive distortions in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). We also examined differences in emotion regulation and cognitive distortions across the trauma spectrum.

Methods

The study was conducted in France between December 2019 and August 2020 and was approved by the university ethics committee. We recruited 180 participants aged over 18, with 3 groups of 60 each: (1) patients diagnosed with PTSD, (2) trauma-exposed without PTSD, (3) no history of trauma. Exclusion criteria were a history of neurological or mental disorders, psychoactive substance abuse, and a history of physical injury that could affect outcomes. All participants completed the Life Events Checklist‑5 (LEC-5), Post-traumatic Check List‑5 (PCL-5), Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES), Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ), and Cognitive Distortions scale for Adults (EDC-A). Correlation analysis was performed to observe the relationship between PTSD severity and cognitive functioning. Correlations between cognitive distortions and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies were calculated for the PTSD group. A moderation analysis of the whole sample was conducted to examine the relationship between cognitive distortions, emotion regulation strategies, and PTSD.

Results

Participants with PTSD scored significantly higher on the PCL‑5 and for dissociation than the other groups. PCL‑5 scores were positively correlated with maladaptive emotion regulation strategies and acceptance. They were also correlated with positive and negative dichotomous reasoning and negative minimization. Analysis of the PTSD group revealed correlations between maladaptive emotion regulation strategies and negative cognitive distortions. The moderation analysis revealed the cognitive distortions explaining the relationship between emotion regulation strategies and trauma exposure overall, and how they exacerbate emotional problems in PTSD.

Conclusion

The study provides indications for management of PTSD patients. Inclusion of an intermediate group of individuals exposed to trauma without PTSD revealed differences in the observed alterations. It would be interesting to extend the cross-sectional observation design to study traumatic events that may cause a specific type of disorder.

Zusammenfassung

Zweck

Die vorliegende Studie untersuchte die Wechselwirkungen zwischen Emotionsregulationsstrategien und kognitiven Verzerrungen bei posttraumatischer Belastungsstörung (PTSD). Außerdem wurden die Unterschiede in der Emotionsregulation und den kognitiven Verzerrungen innerhalb des Traumaspektrums untersucht.

Methoden

Die Studie wurde zwischen Dezember 2019 und August 2020 in Frankreich durchgeführt und von der Ethikkommission der Universität genehmigt. Es wurden 180 Teilnehmer im Alter von über 18 Jahren rekrutiert, die in 3 Gruppen zu je 60 Personen eingeteilt wurden: (1) Patienten mit diagnostizierter PTBS, (2) Traumaexponierte ohne PTBS, (3) ohne Traumaanamnese. Ausschlusskriterien waren neurologische oder psychische Störungen in der Anamnese, psychoaktiver Substanzmissbrauch und eine körperliche Verletzung in der Vorgeschichte, welche die Ergebnisse beeinflussen könnte. Alle Teilnehmenden füllten die Life Events Checklist‑5 (LEC-5), die Post-traumatic Check List‑5 (PCL-5), die Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES), den Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) und die Cognitive Distortions Scale for Adults (EDC-A) aus. Eine Korrelationsanalyse wurde durchgeführt, um die Beziehung zwischen dem Schweregrad der PTBS und den kognitiven Funktionen zu untersuchen. Die Korrelationen zwischen kognitiven Verzerrungen und maladaptiven Emotionsregulationsstrategien wurden für die PTBS-Gruppe berechnet. Eine Moderationsanalyse der gesamten Stichprobe wurde durchgeführt, um die Beziehung zwischen kognitiven Verzerrungen, Emotionsregulationsstrategien und PTBS zu untersuchen.

Ergebnisse

Teilnehmende mit PTBS erzielten signifikant höhere Werte in der PCL‑5 und für Dissoziation als die anderen Gruppen. Die PCL-5-Werte waren positiv mit maladaptiven Emotionsregulationsstrategien und Akzeptanz korreliert. Sie korrelierten auch mit positivem und negativem dichotomem Denken und negativer Minimierung. Die Analyse der PTBS-Gruppe ergab Korrelationen zwischen maladaptiven Emotionsregulationsstrategien und negativen kognitiven Verzerrungen. Die Moderationsanalyse zeigte, dass die kognitiven Verzerrungen die Beziehung zwischen den Emotionsregulationsstrategien und der Traumaexposition insgesamt erklären und wie sie die emotionalen Probleme bei PTBS verschlimmern.

Schlussfolgerung

Die Studie liefert Hinweise für das Management von PTBS-Patienten. Die Einbeziehung einer Zwischengruppe von Personen, die einem Trauma ausgesetzt waren, ohne an einer PTBS zu leiden, ergab Unterschiede bei den beobachteten Veränderungen. Es wäre interessant, das Design der Querschnittsbeobachtung zu erweitern, um traumatische Ereignisse zu untersuchen, die möglicherweise eine bestimmte Art von Störung verursachen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) causes impairments in cognitive functioning and emotion regulation, and is associated with cognitive distortions. Studies have suggested mechanisms that could explain the influence of negative thoughts on the development and maintenance of PTSD [10, 14]. Indeed, cognitive distortions often support traumatic reactions [13, 34]. Individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often manifest anxiety and fear through symptoms such as reliving the experience (repetitive and intrusive memories of an event), avoidance (avoiding things that remind them of an event), persistent negative alterations in cognition (e.g., emotion dysregulation), mood change (anxiety or depression), and hyperresponsiveness (DSM‑5, [1]).

First identified by Beck [5, 6], cognitive distortions refer to erroneous thoughts and beliefs that lead an individual to perceive events in an inappropriate manner [28]. However, they are not specific to clinical populations; anyone can exhibit reasoning biases [38]. This dysfunction of logical thinking induces negative automatic thoughts about the self, the environment, and the future. Franceschi’s [19] conceptual model is based on Beck’s [5, 6] original classification of cognitive distortions and their interactions. It is structured around a “reference class”, which consists of a set of events, phenomena, objects or stimuli in general, “duality” that allows an event in the reference class to be characterized according to a dichotomy between two poles (positive/negative, internal/external, collective/individual, etc.), and the “taxonomic system”, which is the way individuals classify the elements of the reference class according to a given duality. Franceschi [19] distinguished between general cognitive distortions (dichotomous reasoning, maximization, minimization, arbitrary focus, omission of the neutral and reclassification into the other pole) and specific distortions, defined as instances of general distortions (disqualification of one of the poles, selective abstraction, and catastrophism; Table 1). Experimental research has shown that interventions aimed at alleviating posttraumatic distress by changing negative cognitions after trauma can lead to more positive beliefs [16]. However, the cognitive distortion mechanisms activate the response element that leads individuals to relive the intense emotion associated with the trauma [37]. This explains why trauma-induced disorders are inseparable from emotional disorders. In addition, individuals with PTSD have great difficulty regulating their emotions [21]. For instance, when experiencing emotional distress, these individuals are most at risk of failing to inhibit impulsive responses [47].

According to John and Gross [27], emotion regulation is “the process by which individuals influence what emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience and express those emotions.” Several studies have observed the pivotal role of emotion regulation difficulties in PTSD (e.g., [8, 41]). Monson et al. [36] demonstrated that difficulty describing emotions (avoidance of internal emotional experiences) is associated with increased PTSD symptom severity, particularly after re-exposure [7].

Although the capacity for cognitive emotion regulation is universal, there are individual differences in the thoughts by which people regulate their emotions in response to life experiences. This explains why some individuals will have no problem regulating their emotions while others will. Garnefski et al. [20] identified nine cognitive emotion regulation strategies (Table 2), divided into two groups. First, “adaptive strategies” include acceptance (expression of beliefs of acceptance related to the event), positive concentration (concentration on happier and more pleasant thoughts), concentration on action (concentration on the phases to be taken to cope effectively with the experience), positive reevaluation (giving positive meaning to the experience and making positive deductions), and finally, putting the event into perspective (minimizing and relativizing the seriousness of the event). Secondly, “non-adaptive strategies” include self-blame (assigning responsibility for the experience to oneself), blaming others (assigning responsibility for the experience to others), rumination (obsessive thinking about the feelings associated with the experience), and dramatization (emphasizing the experience’s negative aspects). They also found strong relationships between the use of these strategies and emotional problems. In general, results suggest that people who use maladaptive cognitive styles, such as rumination, catastrophizing and self-blame, may be more vulnerable to emotional problems than those who use adaptive strategies, such as positive reappraisal.

In addition, several studies [35, 52] have reported that PTSD symptoms are associated with more limited access and less ideal use of emotion regulation strategies [55], resulting in unsuccessful efforts to avoid negative experiences [41, 44, 46, 49]. According to these studies, this is manifested through limited access to effective emotion regulation strategies, specific deficits in acceptance of emotional experiences and impulse control, and a lack of emotional clarity. Weiss et al. [55] found that individuals with PTSD report greater difficulty accepting their emotions, endorsing goal-directed behavior during distress, monitoring their behavioral impulses when distressed, and using emotion regulation strategies. Differences in emotion regulation have been found between individuals with and without PTSD following exposure to trauma [56]. Other studies have shown that emotion regulation strategies in individuals with PTSD are most often inappropriate, with links between the severity of psychopathological symptoms and overuse of maladaptive emotion regulation strategies, including avoidance, rumination and worrying [15, 18].

PTSD is known to be associated with cognitive biases [37], cognitive distortions [13], and emotion dysregulation [41]. Cognitive distortions and emotion dysregulation are also implicated in the emergence and maintenance of anxiety disorders [9, 12]. Thus, the aim of this study was to determine the interactions between cognitive distortions and emotion regulation strategies, as well as differences in cognitive functioning, particularly the production of cognitive distortions, and emotion regulation strategies across the trauma spectrum (i.e., individuals with PTSD, exposed to trauma without PTSD symptoms, and no history of trauma). Regarding the inclusion of two trauma-exposed groups (with and without PTSD), Weiss et al. [56] observed that individuals with PTSD had more difficulty managing their emotions than those without PTSD and had limited access to effective emotion regulation strategies. They postulated that this difference could be explained in part by the fact that exposure to trauma can have a positive effect, inducing adaptive responses. Some studies have shown that there are differences between individuals with PTSD following the occurrence of a traumatic event and those exposed to trauma without developing PTSD [4]. The authors found that individuals with PTSD had higher mean scores on rumination and avoidance, while those exposed to trauma without PTSD had higher overall scores on the mindfulness and observation variables. This could indicate that mindfulness is a protective factor for PTSD, as opposed to rumination and avoidance, which are risk factors.

We hypothesized first that the presence of posttraumatic symptoms would be positively correlated with cognitive distortions and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies. We expected to observe greater impairments in both variables in the clinical group. Secondly, we hypothesized that the production of cognitive distortions would be positively correlated with the use of maladaptive emotional strategies in PTSD. Finally, we examined the relationship between the three variables studied here in the whole sample; in this way, we sought to gather empirical data for future research by observing the moderating effect of cognitive distortions on the link between PTSD and emotion regulation strategies.

Method

Participants and procedure

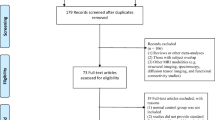

The present study was conducted in France between December 2019 and August 2020, with a break of 4 months (March–April 2020) due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It involved 180 participants in 3 groups. Group 1 (n = 60) comprised 44 women and 16 men (age: 35.86 ± 13.14 years) diagnosed with PTSD; group 2 (n = 60) was composed of 25 women and 35 men (age: 34.01 ± 11.80 years) who had been exposed to trauma without PTSD symptoms; and group 3 (n = 60) included 32 women and 28 men (age: 34.28 ± 11.91 years) with no history of trauma.

Participants in the PTSD group were recruited after psychiatric consultations at a French university hospital. They were at least 18 years old, had experienced a traumatic event in the past year, had been suffering from PTSD for more than 3 months, diagnosed by a qualified psychiatrist (WEH) based on a structured clinical interview, and had been undergoing a course of treatment/therapy for at least 4 weeks. They were therefore at the beginning of psychological and medical treatment. Participants in the trauma-exposed non-PTSD group were recruited through victim support groups; inclusion criteria were to be over 18 years of age, to have a positive history of a traumatic event but no PTSD diagnosis, and not to be receiving current treatment/therapy. Participants in the control group were recruited through notices posted on the university’s notice boards and on social media; inclusion criteria were to be over 18 years of age and to have no history of a traumatic event.

Exclusion criteria for all participants were a history of neurological or mental disorders (e.g., bipolar disorder, substance-related disorders, schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, major depressive disorders), psychoactive substance abuse, and a history of physical injury that could impact outcomes (e.g., head injury) [51].

Regarding the nature of the traumatic events: in the PTSD group, 65% had experienced physical or sexual assault, 10% had been involved in road accidents, 15% had lost a loved one following a violent death, and 10% had experienced traumatic events related to war or a risky profession. In the group without PTSD, 30% had been victims of physical or sexual assault, 20% were victims of road accidents, 5% of natural disasters, 28% of the sudden death of a loved one, and 16% of events related to their profession or to war.

All participants completed the questionnaires face-to-face with the examiner in a quiet environment. After giving their written consent, they provided sociodemographic information. They then completed the self-report questionnaires. Data were collected anonymously, and each participant was assigned a unique and random code to guarantee confidentiality. The average time taken to complete the questionnaires was 30 min.

The study was performed in accordance with the World Medical Association’s Code of ethical principles for medical research (Declaration of Helsinki). The protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the universities of Tours and Poitiers (CER-TP no.19-11-06).

Measures

Life Events Checklist for DSM-5

The Live Events Checklist for DSM‑5 (LEC-5) standard version [54] is a self-report measure designed to screen for lifetime traumatic events. The scale assesses exposure to 16 events known to potentially lead to PTSD or distress. The French version shows very good internal consistency (α = 0.94) [22].

Posttraumatic Checklist for DSM-5

The French version of the Posttraumatic Checklist for DSM‑5 (PCL-5) [2] was used to assess the severity of PTSD symptoms. This self-report 20-item questionnaire assesses the 20 symptoms of PTSD based on DSM‑5 criteria. Items are rated from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). A total score of 32 suggests PTSD [40]. The internal consistency of the PCL‑5 is satisfactory (Cronbach’s α = 0.97).

Dissociative Experiences Scale

The Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES-T) was developed by Waller et al. [53] and is composed of eight items assessing pathological dissociation. The objective is to determine the frequency with which individuals experience these events while not under the influence of alcohol. The French version shows good internal consistency (α = 0.82).

Cognitive Regulation of Emotions Questionnaire

The Cognitive Regulation of Emotions Questionnaire (CERQ) [20] comprises 36 items assessing the participants’ ability to regulate their emotions (Table 2). It has been adapted and validated in French [26]. Items are rated on a Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). In our study, the consistency of the French questionnaire was good for each subscale (Cronbach’s α coefficient ranging from 0.74 to 0.86).

Cognitive Distortions Scale for Adults (EDC-A)

The Cognitive Distortions Scale for Adults is a French tool developed by Robert et al. [43] and is used to assess the production of cognitive distortions. It is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 42 scenarios describing everyday events, with suggestions about what participants might think in a similar situation. For each scenario, the participants assign a score to the corresponding suggestion, ranging from 0 (not at all what I think) to 10 (exactly what I think). The cognitive distortions assessed are: dichotomous reasoning (i.e., interpreting events using all-or-nothing thinking, and thus perceiving a reference class only in relation to the extreme taxon of each pole), omitting the neutral (i.e., ignoring neutral aspects of the event and considering them as positive or negative), disqualifying one of the poles (i.e., characterizing the events of one of the poles in relation to those of the other pole), recharacterization in the other pole (i.e., characterizing as negative an event that should objectively be perceived as positive and vice versa), arbitrary focus (i.e., focusing on one event in the reference class and ignoring the others), minimization (i.e., considering an event as less important than it actually is), and maximization (i.e., exaggerating the importance of an event). Each cognitive distortion is targeted by six scenario/suggestion pairs, with three reflecting a positive distortion (i.e., rated toward the positive end of the spectrum), and the remaining three reflecting a negative distortion. In our study, the EDC‑A showed good internal consistency for each subscale (Cronbach’s α 0.11–0.52). For the original scale, the internal consistency for each subscale was good (0.65–0.87) [43].

Statistical analysis

The software used was SPSS 27.0.1.1 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and SPSS Hayes Process moderator [23]. Descriptive statistics were calculated for sociodemographic and psychological characteristics. Correlation analysis was performed to observe the relationship between severity of PTSD and cognitive functioning. Correlations between the production of cognitive distortions and the use of maladaptive emotion regulation strategies were then calculated for the PTSD group. A moderation analysis with the whole sample was conducted to examine the relationship between cognitive distortions, emotion regulation strategies and PTSD.

Results

Statistically significant differences between groups were detected in mean scores of all the scales (Table 3) for emotion regulation. The participants with PTSD had significantly higher scores on the PCL‑5 (53.10 ± 9.35) and for dissociation (18.96 ± 18.12) than the trauma-exposed without PTSD group (PCL-5: 17.33 ± 11.81, dissociation: 8.50 ± 10.84) and the control group (PCL-5: 2.57 ± 5.90 and dissociation: 3.41 ± 7.12).

First, the PCL‑5 scores were positively correlated with the maladaptive emotion regulation strategy subscales and with acceptance (Table 4). Regarding cognitive distortions, PCL‑5 scores were correlated with positive and negative dichotomous reasoning and negative minimization.

Similar results can be observed for the DES‑T subscales, which were positively correlated with maladaptive emotion regulation strategies and with acceptance. Regarding cognitive distortions, DEST‑T scores were correlated with positive and negative dichotomous reasoning and with requalification in the other pole.

Analysis of the trauma-exposed with PTSD group revealed correlations between maladaptive emotion regulation strategies and negative cognitive distortions (Table 5). This can be explained by the fact that negative cognitive distortions maintain posttraumatic stress.

Table 6 shows the results of the moderation analyses, revealing the cognitive distortions that significantly explain the relationship between emotion regulation strategies and PTSD in the whole sample, and in particular how they exacerbate emotional problems in PTSD. First, regarding maladaptive emotion regulation strategies, we can see a significant correlation for negative disqualification (β = 0.1579, p < 0.05), negative dichotomous reasoning (β = −0.1684, p < 0.05), positive disqualification (β = 0.1072, p < 0.05), negative arbitrary focus (β = 0.1663, p < 0.05), and omission of the neutral negative (β = −0.1214, p < 0.05). Second, regarding adaptive emotion regulation strategies, we can see a significant correlation for the negative cognitive distortions cluster (β = −0.1365, p < 0.05), omission of neutral negative (β = −0.1611, p < 0.05), omission of neutral positive (β = −1484, p < 0.05), and positive maximization (β = −0.1675, p < 0.05).

Discussion

The objective of our study was to identify the interactions between cognitive distortions (positive and negative) and emotion regulation strategies (adaptive or maladaptive) across the trauma spectrum (i.e., individuals with PTSD, individuals exposed to trauma without PTSD symptoms, and healthy individuals).

In accordance with our first hypothesis, we observed positive correlations between the severity of PTSD and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies and acceptance. These findings are in line with the scientific literature, indicating that individuals with PTSD have more difficulty managing their emotions [15, 55]. In line with our second hypothesis, we found that the production of negative cognitive distortions was positively correlated with the use of maladaptive emotion regulation strategies. Cognitive distortions are negatively biased thinking errors that increase the vulnerability of individuals [42]. Anxiety–depressive factors have a significant effect on cognitive distortions [33] and emotion regulation strategies [3]. This distorted negative thinking is characterized by a rigid thought pattern that lacks objectivity. Individuals who produce negative distortions have difficulty accessing and retrieving information and memories that are inconsistent with their current negative state [24]. Moreover, depending on the content of the negative distortions, individuals may assume that others do not think well of them due to the stress or anxiety caused by the experienced event [9] and feel guilty. If the content of their thinking is focused on themselves or the experienced event, they may lack efficacy and confidence, thereby increasing their vulnerability [42]. The correlation analyses are consistent with earlier findings [41, 48]. Again, it is the negative cognitive distortions that explain the correlation between severity of PTSD and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies.

Overall, our results confirm data in the scientific literature linking PTSD to impairments in cognitive functioning, including cognitive distortions and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies. Regarding cognitive distortions, we found a positive correlation between the severity of PTSD and requalification into the other pole (positive), dichotomous reasoning (negative), minimization (negative), maximization (negative) and total cognitive distortions (negative). This implies that the difficulties associated with these distortions increase with the severity of posttraumatic symptoms. Brewin and Holmes [10] put forward several explanations for why negative thoughts may influence the onset and maintenance of PTSD, including the fact that cognitive distortions often support traumatic reactions [13]. Conditioning caused by the traumatic event is thus an important process in the maintenance of PTSD. Nevertheless, while the development of PTSD is not systematic, a chronic response to the traumatic event can severely disrupt the ability to return to the previous lifestyle [29, 50]. Other studies have found an automatic processing bias for threatening information, consistent with long-standing reports of hypervigilance after trauma [30, 39]. This automatic processing bias is also an underlying mechanism in the production of cognitive distortions [31].

Finally, experimental research has shown that interventions aimed at modifying negative cognitions after trauma can result in more positive beliefs and consequently in less severe posttraumatic distress. Furthermore, Foa and Rothbaum [17] observed that there are two essential conditions for successful treatment of PTSD: (1) activation of the fear structure, and (2) provision of new information that is incompatible with existing pathological elements. Cognitive restructuring thus seems to be an essential part of treatment for people with PTSD.

The study by Boden et al. [8] indicated a clear association between impaired emotion management and posttraumatic symptoms. We found that “acceptance” was positively related to PTSD, raising the question of whether this strategy is specifically linked to the trauma and plays a role in emotion management alongside resilience. Our results suggest that therapeutic action targeting emotion regulation strategies could contribute to the management of individuals who have lived through a stressful experience. They also suggest that the ability to control impulsive behaviors when distressed and access to effective emotion regulation strategies may be protective factors against the development of PTSD. This suggests that treatment techniques focusing on impulsive behaviors would enable individuals to regulate their emotions appropriately. Finally, our results indicate that the links between emotional difficulties [48] and maladaptive cognitions [9] should be considered in the management of patients with PTSD.

Regarding the study design, our results show the importance of including an intermediate group of individuals who have been exposed to trauma without developing PTSD, which enabled us to observe differences between the three groups [11]. It would be interesting to extend the cross-sectional observation study methodology used here to the study of traumatic events likely to cause a specific type of disorder [32].

The main finding of this study was that the production of cognitive distortions is associated with emotion regulation strategies. Moreover, the novelty of the study is that it tested the impact of PTSD symptoms on the interactions between emotion regulation strategies and cognitive distortions. Clinically, the need to address cognitive distortions seems obvious in order to help patients identify and manage them, using cognitive restructuring techniques. Given the ubiquity of cognitive distortions (positive and negative) in the general population [38], clinicians may need specialized training in these interventions to help clients recognize their automatic thoughts, identify cognitive distortions, test their validity, and develop more functional thoughts [18]. This would help them see the effect of the trauma experience on their behavior.

Limitations

Given that people do not always have conscious access to the full range of the strategies they use, it is likely that some subtleties are not detectable in the analysis of self-reported behavioral measures. Interpersonal issues (social desirability, denial, etc.) about the experienced event, for example, may have biased the participants’ responses. We did not control for any comorbid conditions in the participants as the protocol was already extensive, and we did not wish to add a questionnaire such as the MINI. However, the International Society for Traumatic Stress studies [25] recommends that comorbidities should be treated first in order to reduce the severity of PTSD. It would therefore be interesting to take comorbidities into account in future research. Finally, there could be a recruitment bias; all the participants were volunteers, which is known to weaken the external and internal validity of a study [45].

Conclusion

Our results reveal a specific pattern of cognitive distortions and emotion regulation strategies used by people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). They suggest that the relationship between emotion regulation strategies and negative cognitive distortions underlies the severity of PTSD. They also show the importance of recruiting a group of participants who have been exposed to trauma without developing PTSD in order to identify impairments that are specific to exposure to trauma and, hence, the differential impact of those caused by PTSD. A more accurate understanding of the cognitive functioning of individuals with PTSD would enable clearer diagnosis and better management. Identifying which aspects of the individual’s cognitive and psychological functioning are impaired as a result of the trauma would make it possible to set up the most appropriate treatment program.

References

American Psychiatric Association (APA). DSM‑V diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC.: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Ashbaugh AR, Houle-Johnson S, Herbert C, El-Hage W, Brunet A. Psychometric validation of the English and French versions of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM‑5 (PCL-5). PLoS ONE. 2016;11(10):e161645. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161645.

Bardeen JR, Tull MT, Stevens EN, Gratz KL. Further investigation of the association between anxiety sensitivity and posttraumatic stress disorder: examining the influence of emotional avoidance. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2015;4(3):163–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2015.05.002.

Basharpoor S, Shafiei M, Daneshvar S. The Comparison of Experiential Avoidance, [corrected] Mindfulness and Rumination in Trauma-Exposed Individuals With and Without Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in an Iranian Sample. Archives of psychiatric nursing. 2015;29(5):279–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2015.05.004.

Beck AT. Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York: International Universities Press; 1976.

Beck JS. Cognitive therapy: basics and beyond. New York, NY: Guilford; 1995.

Berna G, Ott L, Nandrino JL. Effects of emotion regulation difficulties on the tonic and phasic cardiac autonomic response. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e102971. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102971.

Boden MT, Thompson RJ, Dizén M, Berenbaum H, Baker JP. Are emotional clarity and emotion differentiation related ? Cogn Emot. 2013;27(6):961–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2012.751899.

Booth RW, Sharma D, Dawood F, Doğan M, Emam HMA, Gönenç SS, et al. A relationship between weak attentional control and cognitive distortions, explained by negative affect. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(4):e215399. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215399.

Brewin CR, Holmes EA. Psychological theories of posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23(3):339–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00033-3.

Cascardi M, Armstrong D, Chung L, Paré D. Pupil response to threat in trauma-exposed individuals with or without PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(4):370–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22022.

Chung MC, Jalal S, Khan NU. Posttraumatic stress disorder and psychiatric comorbidity following the 2010 flood in Pakistan: exposure characteristics, cognitive distortions, and emotional suppression. Psychiatry. 2014;77(3):289–304. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2014.77.3.289.

Cieslak R, Benight CC, Caden Lehman V. Coping self-efficacy mediates the effects of negative cognitions on posttraumatic distress. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46(7):788–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.03.007.

Ehlers A, Clark DM. A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38(4):319–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00123-0.

Fairholme CP, Nosen EL, Nillni YI, Schumacher JA, Tull MT, Coffey SF. Sleep disturbance and emotion dysregulation as transdiagnostic processes in a comorbid sample. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51(9):540–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2013.05.014.

Foa EB, Rauch SAM. Cognitive changes during prolonged exposure versus prolonged exposure plus cognitive restructuring in female assault survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(5):879–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.72.5.879.

Foa EB, Rothbaum BO. Treating the trauma of rape: Cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD. New York: Guilford Press, 1998.

Foa EB, Hembree EA, Rothbaum BO. Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Emotional processing of traumatic experiences: Therapist guide. Oxford University Press; 2007. https://doi.org/10.1093/med:psych/9780195308501.001.0001.

Franceschi P. Compléments pour une théorie des distorsions cognitives. J De Thérapie Comportementale Et Cogn. 2007;17(2):84–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1155-1704(07)89710-2.

Garnefski N, Kraaij V, Spinhoven P. Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;30(8):1311–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(00)00113-6.

Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2004;26(1):41–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:joba.0000007455.08539.94.

Gray MJ, Litz BT, Hsu JL, Lombardo TW. Psychometric properties of the life events checklist. Assessment. 2004;11(4):330–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191104269954.

Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach (Methodology in the Social Sciences). 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2018.

Ingram RE, Steidtmann DK, Bistricky SL. Information processing: Attention and memory. In Dobson KS, Dozois DJA, editors. Risk factors in depression. Oxford, United Kingdom: Elsevier/Academic Press; 2008. pp. 121–43.

Bisson JI, Berliner L, Cloitre M, Forbes D, Jensen TK, Lewis C, Monson CM, Olff M, Pilling S, Riggs DS, Roberts NP, Shapiro F. The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies New Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Methodology and Development Process. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2019;32(4):475–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22421.

Jermann F, Van der Linden M, D’Acremont M, Zermatten A. Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire (CERQ). Eur J Psychol Assess. 2006;22(2):126–31. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.22.2.126.

John OP, Gross JJ. Healthy and Unhealthy Emotion Regulation: Personality Processes, Individual Differences, and Life Span Development. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:1301–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00298.x.

Kendall PC. Guiding theory for therapy with children and adolescents. In: Kendall PC, editor. Child and adolescent therapy: cognitive-behavioral procedures Guilford; 2012. pp. 3–24.

Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, Miller MW, Keyes KM, Friedman MJ. National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Journal of traumatic stress. 2013;26(5):537–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21848.

Kimble MO, Fleming K, Bandy C, Kim J, Zambetti A. Eye tracking and visual attention to threating stimuli in veterans of the Iraq war. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2010;24(3):293–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.12.006.

Kimble M, Sripad A, Fowler R, Sobolewski S, Fleming K. Negative world views after trauma: Neurophysiological evidence for negative expectancies. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2018;10(5):576–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000324.

Kira IA, Shuweikh H, Al-Huwailiah A, El-wakeel SA, Waheep NN, Ebada EE, Ibrahim ESR. The direct and indirect impact of trauma types and cumulative stressors and traumas on executive functions. Appl Neuropsychol. 2020; https://doi.org/10.1080/23279095.2020.1848835.

Kuru E, et al. Cognitive distortions in patients with social anxiety disorder: comparison of a clinical group and healthy controls. Eur J Psychiat. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpsy.2017.08.004.

Mayou R, Ehlers A, Bryant B. Posttraumatic stress disorder after motor vehicle accidents: 3‑year follow-up of a prospective longitudinal study. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40(6):665–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00069-9.

McDermott MJ, Tull MT, Gratz KL, Daughters SB, Lejuez C. The role of anxiety sensitivity and difficulties in emotion regulation in posttraumatic stress disorder among crack/cocaine dependent patients in residential substance abuse treatment. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23(5):591–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.01.006.

Monson CM, Schnurr PP, Stevens SP, Guthrie KA. Cognitive-Behavioral Couple’s Treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: initial findings. Journal of traumatic stress. 2004;17(4):341–4. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOTS.0000038483.69570.5b.

Owens GP, Chard KM, Cox TA. The relationship between maladaptive cognitions, anger expression, and posttraumatic stress disorder among veterans in residential treatment. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2008;17(4):439–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926770802473908.

Pennequin V, Combalbert N. L’influence des biais cognitifs sur l’anxiété chez des adultes non cliniques. Ann Médico-psychologiques Revue Psychiatr. 2017;175(2):103–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amp.2015.07.040.

Pineles SL, Shipherd JC, Welch LP, Yovel I. The role of attentional biases in PTSD: Is it interference or facilitation? Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45(8):1903–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.08.021.

National Center for PTSD. PTSD checklist for DSM‑5 (PCL-5).. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp. Accessed 18 Mar 2020.

Radomski SA, Read JP. Mechanistic role of emotion regulation in the PTSD and alcohol association. Traumatology. 2016;22(2):113–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000068.

Rnic K, Dozois DJA, Martin RA. Cognitive distortions, humor styles, and depression. Eur J Psychol. 2016;12(3):348–62. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v12i3.1118.

Robert A, Combalbert N, Pennequin V, Deperrois R, Ouhmad N. Création de l’Echelle de Distorsions Cognitives pour adultes (EDC-A): Etude des propriétés psychométriques en population générale et association avec l’anxiété et la dépression. Psychol Française. 2021; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psfr.2021.04.003.

Roemer L, Litz BT, Orsillo SM, Wagner AW. A preliminary investigation of the role of strategic withholding of emotions in PTSD. J Traum Stress. 2001;14(1):149–56. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1007895817502.

Sackett DL. Bias in analytic research. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1979;32(1-2):51–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(79)90012-2.

Salters-Pedneault K, Tull MT, Roemer L. The role of avoidance of emotional material in the anxiety disorders. Appl Prev Psychol. 2004;11(2):95–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appsy.2004.09.001.

Shepherd L, Wild J. Emotion regulation, physiological arousal and PTSD symptoms in trauma-exposed individuals. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2014;45(3):360–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2014.03.002.

Spinhoven P, Drost J, van Hemert B, Penninx BW. Common rather than unique aspects of repetitive negative thinking are related to depressive and anxiety disorders and symptoms. J Anxiety Disord. 2015;33:45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.05.001.

Steil R, Ehlers A. Dysfunctional meaning of posttraumatic intrusions in chronic PTSD. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38(6):537–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00069-8.

Tanielian T, Jaycox LH. Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2008. https://doi.org/10.1037/e527612010-001

Tudorache A-C, El-Hage W, Goutaudier N, Clarys D. Beyond Clinical Outcomes: Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms Favour Attentional and Memory Control Abilities for Trauma-Related Words. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2020;33(5):783–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22531.

Tull MT, Barrett HM, McMillan ES, Roemer L. A preliminary investigation of the relationship between emotion regulation difficulties and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Behav Ther. 2007;38(3):303–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2006.10.001.

Waller N, Putnam FW, Carlson EB. Types of dissociation and dissociative types: A taxometric analysis of dissociative experiences. Psychological Methods. 1996;1(3):300–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.3.300.

Weathers FW, Blake DD, Schnurr PP, Kaloupek DG, Marx BP, Keane TM. The life events checklist for DSM‑5 (LEC-5)—standard. 2013. Measurement instrument.

Weiss NH, Tull MT, Anestis MD, Gratz KL. The relative and unique contributions of emotion dysregulation and impulsivity to posttraumatic stress disorder among substance dependent inpatients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;128(1):45–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.017.

Weiss NH, Tull MT, Viana AG, Anestis MD, Gratz KL. Impulsive behaviors as an emotion regulation strategy: examining associations between PTSD, emotion dysregulation, and impulsive behaviors among substance dependent inpatients. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26(3):453–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.01.007.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

N. Ouhmad, W. El-Hage and N. Combalbert declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

The study was conducted in compliance with the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects (Declaration of Helsinki). All the participants gave their written consent after they had been informed of the purpose of the study. The study and consent procedures were approved by the ethics committee of the University (Comité d’Ethique de la Recherche Tours-Poitiers, no. 2019-11-06).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ouhmad, N., El-Hage, W. & Combalbert, N. Maladaptive cognitions and emotion regulation in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychiatr 37, 65–75 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40211-022-00453-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40211-022-00453-w