Abstract

The probable extinction of the last confirmed population of northern white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum cottoni) in the world has ignited debate regarding its species status compared to the southern white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum simum). Previous studies, based on partial mitochondrial sequences, have reported conflicting results regarding the species status of the northern white rhinoceros. We use whole mitochondrial genomes obtained using Next Generation Sequencing of four northern white rhinoceros and three southern white rhinoceros using novel primers in three overlapping fragments. Phylogenetic relationships were constructed, using Maximum Likelihood, and recovered monophyletic clades for northern white rhinoceros and southern white rhinoceros. The divergence time between the two mitochondrial DNA lineages was estimated to be between 0.46 and 0.97 million years ago using Bayesian inferences. Since there are currently only three surviving northern white rhinoceros individuals these results put into sharp focus the ongoing debate regarding the methods of species definition, and in particular the consequences of such definitions in conservation management of endangered species and subspecies. We conclude that the designation of sub-species status is more applicable to northern and southern white rhinoceros.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Habitat destruction and extensive poaching pressure have led to an extreme decline of many rhinoceros populations in the wild (Emslie 2011; Emslie and Brooks 1999). This is particularly severe in the case of the northern white rhinoceros, Ceratotherium simum cottoni (NWR). The southern white rhinoceros (SWR), Ceratotherium simum simum is still relatively abundant, with an estimated number of over 20,400 in the wild in 2012 (Knight 2013; Emslie and Knight 2014). NWR were conserved until recently in Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in Africa, but by 2000 numbers had fallen to 30 (Smith 2001), then to four in 2006, and there have been no sightings of rhinoceros in the park since 2007 (Emslie 2011). There are no other wild populations and currently only three NWR survive in captivity: an old male (named Sudan) and two females, one the daughter of Sudan, in Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya. These last three animals were moved to Kenya in 2009 in the hope that a move to more natural conditions might stimulate their breeding, given the generally better breeding performance of wild compared to captive white rhinoceros (Swaisgood 2006). Following the move to Kenya, the females started cycling and both mated. Both pure and inter-crossed (with SWR) matings occurred, demonstrating that there was no problem with mate recognition. However, perhaps due to the age of the animals, no offspring have yet resulted. The last hope for rescuing at some of the genetic diversity of the NWR now appears to be the successful interbreeding with the SWR, or to attempt more ambitious measures such as in vitro fertilization techniques with embryo transfer into surrogate SWR females, or even the use of stem cell technology. However, the latter would be complicated and costly procedures that have never before been attempted in this species.

NWR and SWR are traditionally considered as subspecies of Ceratotherium simum, but a recent study (Groves et al. 2010) suggested that NWR and SWR should be elevated to separate species status: Ceratotherium cottoni for NWR and C. simum for SWR. This creates a problem for conservation, because whereas crossing subspecies together for a genuine conservation purpose is deemed acceptable, crossing species is generally considered unacceptable, although in specialised areas such as horticulture it is commonplace. If Groves et al. (2010) are correct then attempts to save genetic resources from the NWR by interbreeding with SWR are therefore also unacceptable. As a consequence it has become necessary, firstly to examine additional genetic data that distinguishes NWR from SWR to clarify how different they are, and secondly to foster a critical appraisal of species definitions and their appropriateness in the conservation context. To achieve the first objective, we sequenced and compared the complete mitochondrial genomes of four NWR and three SWR individuals.

Materials and methods

Sampling strategy

The complete mitochondrial genome of the white rhinoceros has been sequenced (Xu and Arnason 1997) and was used as a reference sequence for the design of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers. We sequenced DNA from four NWR and three SWR individuals. All NWR samples are from Garamba National Park in what was north eastern Zaire, now Orientale Province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in Africa. SWR samples were from Hluhluwe-Imfolozi Park, South Africa (n = 2), and Waterberg Plateau, Namibia (n = 1). Ear notches were taken from individuals as part of immobilisation of NWR for radio-telemetry (WWF project 1954.01/ZR0009.02) in 1992 by A. K. Hillman-Smith. These tissue samples were cultured and total DNA extracted as described by O’Ryan et al. (1994).

Laboratory procedures

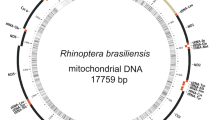

We designed three sets of overlapping primer sequences that among them amplified the entire mitochondrial genome (Table 1). Primer sets 1–3 amplified the three fragments using Kapa Taq Long Range DNA Polymerase according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR was run with an initial denaturation step of 94 °C for 10 min, with 32 cycles consisting of 50 s at 94 °C, followed by 50 s at 58 °C (first 4 cycles), 56 °C (cycles 5–8), 54 °C (cycles 9–12), 52 °C (cycles 13–16), or 50 °C (final 16 cycles), followed by an 8 min extension at 72 °C, with a final extension after the last cycle of 10 min at 72 °C. The same PCR procedure was followed for primer set 2 and primer set 3 but with 11 and 6.5 min extension times respectively. Successfully amplified PCR fragments were purified using the Wizard SV Gel and PCR Purification Kit (Promega). The amplicons were sequenced using an Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine. The Ion PLUS kit was used to generate the sequencing libraries, which was followed by emulsion PCR using the Ion One Touch 200 Template kit v2 (Life Technologies). Sequencing of the DNA from the amplicon libraries was performed on a 316 chip using the Ion PGM 200 sequencing kit v2. A total of 1 272 251 sequenced fragments, with an average size of 137 bp and a Phred score >20, were mapped to the reference white rhinoceros mitochondrial sequence (Genbank accession number NC_001808.1), using the Torrent Suite software v3.2.1. This resulted in an average coverage of 9 905.5X per nucleotide in the mitochondrial sequence. The Torrent Suite MtVariantCaller plugin was used to identify the nucleotide variants relative to the reference sequence to generate a unique mitochondrial sequence for each sample.

Analysis of genetic variation

For the construction of phylogenetic trees, the complete mitochondrial sequences of each of the other four species of extant rhinoceros were downloaded from Genbank. For purposes of calibration the complete mitochondrial sequences of appropriate out-group species were also downloaded and are listed in Table 2. To minimise the overall sequence stochastic variation four diverse members of each out-group were chosen.

For other comparisons the sequences of Homo sapiens neanderthalensis (Green et al. 2008, Accession number NC 011137), the Denisovan hominid (Krause et al. 2010, Accession number NC 013883) and ten different non-pathological human mitochondrial haplotypes from haplogroups L1a, L1b, L1c, L2a, L2b, L2c, L3b, L3d, M, and N (using the nomenclature of Ingman and Gyllensten 2006) with accession numbers AY195780, AY195783, AF346987, AY195788, AY195766, AY195785, AY195784, AY195782, AY255176 and AY195786 respectively, used for genealogical studies, and including the most diverse groups of human haplotypes (Ingman and Gyllensten 2006), were downloaded from the Human Mitochondrial Genome Database (mtdb.igp.uu.se) or from Genbank.

We aligned sequences using the automatic multiple sequence alignment option in DAPSA (Harley 2015), with final optimization by eye; this program was also used for calculation of the proportion of shared sites. Phylogenies were constructed in MEGA version 6 (Tamura et al. 2013) using Maximum Likelihood with Kimura 2-parameter substitution and gamma-distributed rates among sites using four discrete gamma categories and 1000 bootstrap replicates. Branch lengths were estimated using the BEAST package version 1.5.1 with results interpreted by its included Tracer program; 107 iterations were used as standard with burnin values adjusted to maximize the effective sample size (ESS) of the posterior distribution of the white rhino divergence node; the HKY substitution model was used with empirical base frequencies and gamma plus invariant sites (4 gamma categories) for the site heterogeneity model; a lognormal relaxed clock and Yule speciation process was employed with a UPGMA starting tree. To provide an absolute time scale for these trees, five placental calibration points were used as tree priors (normally distributed with a standard deviation of 1.3) in separate analyses to calculate distances on the branches. The use and validity of these have been summarized by Arnason et al. (2008) with E/R-55, A/C-60, C/F-52, C/P-48, and O/P-30 being respectively the estimated times of divergence between Equidae and Rhinocerotidae, Artiodactyls and Cetaceans, Caniforms and Feliforms (Flynn and Galiano 1982), Otaroidea and Phocidae, and Catarrhini and Platyrrhini. A/C-60, for example, refers to the divergence between Artiodactyla (as represented by ruminants) and Cetacea set at 60 million years ago (Arnason and Gullberg 1996).

Results

Phylogenies were constructed from the aligned mitochondrial DNA data, each one including taxa appropriate for one or other of the five calibrations. One of these is illustrated in Fig. 1. Apart from the out-group taxa, the topologies and bootstrap support values for the other four phylogenies were similar, except in the case of the Sumatran rhinoceros which had low bootstrap support in all analyses, and was placed sometimes basal in the Rhinocerotidae, as here, and sometimes as sister group to the African members of the Rhinocerotidae.

The results of the divergence time estimates for white rhinoceros performed using BEAST are summarised in Table 3. Values vary about twofold, with the C/P-48 calibration giving the minimum estimate and E/R-55 the highest. The standard deviation of the uncorrelated lognormal relaxed clock values were low, indicating only a minor degree of rate heterogeneity amongst lineages.

In the D-loop region of both northern and southern white rhinoceros there is an identical region consisting of a 10 bp repeat of the sequence ACGCATATAC from position 16,389 of the alignment to position 16,727; there are 34 repeats in all. This repeat is not found in the other rhinoceros species although we found that the Indian rhinoceros has an 8 bp repeat of ATGTACAC in the same region.

In order to compare the amount of mitochondrial (mt) DNA sequence variation between northern and southern white rhinoceros with that of another species for which similar sampling has been done, we compared the p-distances in mtDNA with those of Homo sapiens haplotypes recorded for genealogical purposes, as well as, since they are available, those of the sequences recently obtained for the Neanderthal and Denisovan hominids, generally reported as subspecies of H. sapiens. Whereas the p-distances between northern and southern white rhinoceroses individuals all gave a value of 0.009 (within northern and within southern being <0.001), values between ten extant human haplotypes varied from 0.001 to 0.006, with Neanderthal differing from extant haplotypes by 0.012–0.014 and Denisovan by 0.023–0.024 (and by 0.023 from Neanderthal).

Discussion

The white rhinoceros sequencing results using complete mitochondrial genomes confirmed the results of Tougard et al. (2001), which were based on mitochondrial Cytochrome B and 12S rRNA Genes, and those of Willerslev et al. (2009) from whole mitochondrial genomes. Our results, like Tougard et al. (2001) and Willerslev et al. (2009), show a lack of resolution for the placement of the Sumatran Rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), which in some analyses clustered with the African genera but at others with the other Asian genera. On the question as to the time of divergence of NWR and SWR, our data imply that the mtDNA genomes of NWR and SWR diverged somewhere between 0.46 and 0.97 million years ago. These divergence estimates are somewhat less than those quoted by Groves et al. (2010), which were based on only partial mtDNA sequences, and were calibrated from either Hooijer’s (1969) or Geraads’ (2005) paleontological dating. The Groves et al. (2010) study used only a single sample from each of the two white rhinoceros taxa. However, the dating of the actual lineages split between NWR and SWR is likely to be significantly more recent than the mitochondrial genome split. Sanchez-Gracia and Castresana (2012) reported how lineage divergence times can be much younger than gene divergent times, by as much as 300 % for divergence times of <1 million years, so it is possible that the two white rhinoceros lineages could have diverged even as recently as 200,000 years ago.

Supporting a more recent date for the divergence of the two white rhinoceros lineages is the unaltered structure of the repeat region in the D-loop. Such structures are inherently unstable, and are the reason for the utility of microsatellites, where the differences in their repeat number are the basis of their value in population genetics (for example in population differentiation and genetic diversity estimates).

Since there is difficulty in any attempt to date the timing of the lineage split of NWR and SWR with any high degree of accuracy (see Van Tuinen and Hadly 2004; Benton and Donoghue 2007, for reviews of the problem and Parham et al. 2012, for a recent detailed analysis), comparisons with other within-species measurements can be instructive. The simple p-distances of 0.009 between NWR and SWR that we report is greater than the maximum value of 0.006 found between some extant human mtDNA haplotypes, but is less than the difference between extant humans and either Neanderthals or Denisovans, despite these being generally referred to as the subspecies H. s. neanderthalensis and H. s. denisova.

Our estimate, although approximate, of the time of divergence of the NWR and SWR lineages, should not imply that there would necessarily be sufficient outbreeding depression to compromise the fitness of hybrid crosses of the two lineages, if this provides the only opportunity for rescuing some of the genetic contribution of NWR. However, the recent claim by Groves et al. (2010) that the two lineages should be classified as two different species, followed by an extension of their argument to the taxonomy of ungulates generally (Groves and Grubb 2011) has caused a major conservation problem in this regard. Many of the conservation biologists ‘on the ground’ who are involved in the practical implementation of conserving NWR genetic diversity (e.g. Brooks 2010) believe that crossing different species is contrary to their conservation ethos. Consequently it is becoming increasingly important to clarify the definition of what constitutes a species.

Although many species concepts have been proposed (see Frankham et al. 2012) two have been predominantly used—the Biological Species Concept (BSC; Mayr 1966, 1981), and the Phylogenetic Species Concept (PSC; Eldredge and Cracraft 1980; Cracraft 1997).

Under the BSC, species are described as “groups of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations which are reproductively isolated from other such groups” (Mayr 1966), whereas the PSC regards species as the smallest group of populations that can be distinguished by a unique set of morphological or molecular traits. Another key issue under the BSC is whether there is mate recognition. In the case of NWR we know from Ol Pejeta that the two subspecies recognise each other and will mate.

Whereas the BSC implicitly implies that lineages will have been separated for long periods of time in order to become reproductively isolated, the PSC only requires that lineages have been separated for long enough for a trait or traits to become fixed and differentiable in the two populations. The problem with this is that fixation of traits can occur very rapidly, especially when populations are small, and if they have become isolated from each other. Isolation of populations is accentuated by habitat destruction, when genetic drift can cause traits to become fixed in only a few generations. An example of this is provided by a genetic study of the Cape Mountain Zebra, Equus zebra zebra (Moodley and Harley 2005), where habitat encroachment separated populations of Mountain Zebra which had been continuous only a few hundred years ago; some of these populations underwent an extreme decrease in numbers, and microsatellite analysis showed fixed alleles in each of three well-sampled populations separated by no more than a few 100 kms. A strict application of the PSC would require these populations to be assigned to separate species. Detailed criticisms of this ‘taxonomic inflation’ have been provided by Frankham et al. (2012), Zachos et al. (2013) and Heller et al. (2013). The crux of the problem is that the PSC provides a convenient and tidy diagnosability to the species definition, which may appeal to the academic who is uninvolved with the practical conservation consequences of such a definition; it is remarkable that in this context Groves and Grubb (2011) explicitly state that fixed differences should not be evaluated in the context of their biological significance or the underlying divergence process. However, the taxonomic inflation that arises from this leads to situations such as, for example, the splitting of the klipspringer Oreotragus oreotragus, normally considered to be classified as a single species (Wilson and Reeder 2005) into 11 different species based on size differences and differing sexual dimorphism, but using very small sample sizes (sometimes <5); it would also lead to the requirement for H. sapiens to be divided into a large number of separate species (Heller et al. 2013; Zachos et al. 2013), a scenario unlikely to find widespread acceptance.

There is a simple resolution to the argument: if the PSC criteria were modified such that the criteria of fixed traits were used as a definition of subspecies instead of species, there would be much less conflict, and much less harm done to conservation management of small relict populations such as the NWR. At the very least, a comprehensive debate between proponents of the various species concepts is required to construct an acceptable compromise and thereby help prevent unilateral pronouncements with unintended consequences for wildlife management.

Since the criterion of fixed traits is inappropriate in a biological or conservation context for defining species, and since there is also no fixed time at which a lineage divergence defines a species categorisation, it seems logical to retain the current subspecies designation for northern and southern white rhinoceros. Given that the NWR is now extinct in the wild, the only remaining option for rescuing any of the genetic resources of the NWR is to cross NWR with SWR. If evidence of outbreeding depression were to be observed in the progeny of such crosses, then appropriate action could be taken in that event; nothing is to be gained by failing to undertake the experiment.

References

Arnason U, Gullberg A (1996) Cytochrome b nucleotide sequences and the identification of five primary lineages of extant cetaceans. Mol Biol Evol 13:407–417

Arnason U, Gullberg A, Widegren B (1993) Cetacean mitochondrial DNA control region: sequences of all extant baleen whales and two sperm whale species. Mol Biol Evol 10:960–970

Arnason U, Gullberg A, Burguete AS, Janke A (2000) Molecular estimates of primate divergences and new hypotheses for primate dispersal and the origin of modern humans. Hereditas 133:217–228

Arnason U, Adegoke JA, Bodin K, Born EW, EsaYB Gullberg A, Nilsson M, Short RV, Xu X, Janke A (2002) Mammalian mitogenomic relationships and the root of the eutherian tree. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:8151–8156

Arnason U, Gullberg A, Janke A, Kullberg M, Lehman N, Petrov EA, Vainola R (2006) Pinniped phylogeny and a new hypothesis for their origin and dispersal. Mol Phylogenet Evol 41:345–354

Arnason U, Gullberg A, Janke A, Kullberg M (2007) Mitogenomic analyses of caniform relationships. Mol Phylogenet Evol 45:863–874

Arnason U, Adegoke JA, Gullberg A, Harley EH, Janke A, Kullberg M (2008) Mitogenomic relationships of placental mammals and molecular estimates of their divergences. Gene 421:37–51

Benton MJ, Donoghue PCL (2007) Paleontological evidence to date the tree of life. Mol Biol Evol 24:26–53

Bon C, Berthonaud V, Maksud F, Labadie K, Poulain J, Artiguenave F, Wincker P, Aury JM, Elalouf JM (2012) Coprolites as a source of information on the genome and diet of the cave hyena. Proc R Soc B. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0358

Brooks M (2010) African rhino specialist group report. Pachyderm 48:8–15

Cracraft J (1997) Species concepts in systematics and conservation biology: an ornithological viewpoint. In: Claridge MF, Dawah HA, Wilson MR (eds) Species: the units of biodiversity. Chapman and Hall, London, pp 325–339

Douglas KC, Halbert ND, Kolenda C, Childers C, Hunter DL, Derr JN (2011) Complete mitochondrial DNA sequence analysis of Bison bison and bison-cattle hybrids: function and phylogeny. Mitochondrion 11:166–175

Eldredge N, Cracraft J (1980) Phylogenetic patterns and the evolutionary process. Columbia University Press, New York

Emslie R (2011) Ceratotherium simum ssp. cottoni. In: IUCN 2012. IUCN red list of threatened species. Version 2012.2. www.iucnredlist.org

Emslie R, Brooks M (1999) African Rhino. Status survey and conservation action plan. IUCN/SSC African Rhino Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge

Emslie R, Knight MH (2014) Update on African Rhino Status and Poaching Trends from IUCN SSC African Rhino Specialist Group (AfRSG). In: IUCN Report for 65th CITES Standing Committee Meeting

Flynn JJ, Galiano H (1982) Phylogeny of early Tertiary Carnivora, with a description of a new species of Protictis from the middle Eocene of northwestern Wyoming. Am Mus Novit 2725:1–64

Frankham R, Ballou JD, Dudash MR, Eldridge MDB, Fenster CB, Lacy RC, Mendelson JR, Porton IJ, Ralls K, Ryder OA (2012) Implications of different species concepts for conserving biodiversity. Biol Conserv 153:25–31

Geraads D (2005) Pliocene Rhinocerotidae (Mammalia) from Hadar and Dikika (lower Awash, Ethiopia), and a revision of the origin of modern African rhinos. J Vertebr Paleontol 25:451–461

Green RE et al (2008) A complete Neandertal mitochondrial genome sequence determined by high-throughput sequencing. Cell 134:416–426

Groves CP, Grubb P (2011) Ungulate Taxonomy. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Groves CP, Fernando P, Robovský J (2010) The sixth rhino: a taxonomic re-assessment of the critically endangered northern white rhinoceros. PLoS ONE. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009703

Harley EH (2015) DNA and protein sequence alignment (Dapsa, version 6.6). Computer programme distributed as shareware by the author

Hassanin A et al (2012) Pattern and timing of diversification of Cetartiodactyla (Mammalia, Laurasiatheria), as revealed by a comprehensive analysis of mitochondrial genomes. C R Biol 335:32–50

Heller R, Frandsen P, Lorenzen ED, Siegismund HR (2013) Are there really twice as many bovid species as we thought? Syst Biol 62:490–493

Hooijer DA (1969) Pleistocene east African rhinoceroses. Foss Vertebr Afr 1:71–98

Ingman M, Gyllensten U (2006) mtDB: Human Mitochondrial Genome Database, a resource for population genetics and medical sciences. Nucleic Acids Res 34(suppl 1):D749–D751

Knight MH (2013) African rhino specialist group report. Pachyderm 54:8–27

Krause J et al (2008) Mitochondrial genomes reveal an explosive radiation of extinct and extant bears near the Miocene-Pliocene boundary. BMC Evol Biol. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-220

Krause J, Fu Q, Good JM, Viola B, Shunkov MV, Derevianko AP, Pääbo S (2010) The complete mitochondrial DNA genome of an unknown hominin from southern Siberia. Nature 464:894–897

Lopez JV, Cevario S, O’Brien SJ (1996) Complete nucleotide sequences of the domestic cat (Felis catus) mitochondrial genome and a transposed mtDNA tandem repeat (Numt) in the nuclear genome. Genomics 33:229–246

Luo Y, Chen Y, Liu F, Jiang C, Gao Y (2011) Mitochondrial genome sequence of the Tibetan wild ass (Equus kiang). Mitochondr DNA 22:6–8

Mayr E (1966) Animal species and evolution. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Mayr E (1981) Biological classification: toward a synthesis of opposing methodologies. Science (New York, NY) 214:510–516

Mishmar D et al (2003) Natural selection shaped regional mtDNA variation in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:171–176

Moodley Y, Harley EH (2005) Population structuring in mountain zebras (Equus zebra): the molecular consequences of divergent demographic histories. Conserv Genet 6:953–968

O’Ryan C, Flamand JRB, Harley EH (1994) Mitochondrial DNA variation in black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis): conservation management implications. Conserv Biol 8:495–500

Parham JF et al (2012) Best practices for using paleontological data for molecular divergence dating analyses. Syst Biol 61:346–359

Sanchez-Gracia A, Castresana J (2012) Impact of Deep Coalescence on the Reliability of Species Tree Inference from Different Types of DNA Markers in Mammals. PLoS ONE. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030239

Smith KH (2001) Status of northern white rhinos and elephants in Garamba National Park, Democratic Republic of the Congo, during the wars. Pachyderm 31:79–81

Swaisgood R (2006) Scientific detective work in practice: trying to solve the mystery of poor captive-born white rhinoceros reproduction. In: CRES Report (Zoological Society of San Diego), pp 1–3

Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S (2013) MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol 30:2725–2729

Tougard C, Delefosse T, Hanni C, Montgelard C (2001) Phylogenetic relationships of the five extant rhinoceros species (Rhinocerotidae, Perissodactyla) based on mitochondrial cytochrome b and 12S rRNA genes. Mol Phylogenet Evol 19:34–44

Van Tuinen M, Hadly EA (2004) Error in estimation of rate and time inferred from the early amniote fossil record and avian molecular clocks. J Mol Evol 59:267–276

Vilstrup JT et al (2013) Equus zebra hartmannae isolate H21 mitochondrion, complete genome. Mitochondrial phylogenomics of modern and ancient equids. PLoS ONE. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055950

Willerslev E et al (2009) Analysis of complete mitochondrial genomes from extinct and extant rhinoceroses reveals lack of phylogenetic resolution. BMC Evol Biol. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-95

Wilson DE, Reeder DM (2005) Mammal species of the world. A taxonomic and geographic reference, 3rd edn. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Xiong Y, Brandley MC, Xu S, Zhou K, Yang G (2009) Seven new dolphin mitochondrial genomes and a time-calibrated phylogeny of whales. BMC Evol Biol. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-20

Xu X, Arnason U (1994) The complete mitochondrial DNA sequence of the horse, Equus caballus: extensive heteroplasmy of the control region. Gene 148:357–362

Xu X, Arnason U (1996) A complete sequence of the mitochondrial genome of the western lowland gorilla. Mol Biol Evol 13:691–698

Xu X, Arnason U (1997) The complete mitochondrial DNA sequence of the white rhinoceros, Ceratotherium simum, and comparison with the mtDNA sequence of the Indian rhinoceros, Rhinoceros unicornis. Mol Phylogenet Evol 7:189–194

Xu X, Gullberg A, Arnason U (1996a) The complete mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) of the donkey and mtDNA comparisons among four closely related mammalian species-pairs. J Mol Evol 43:438–446

Xu X, Janke A, Arnason U (1996b) The complete mitochondrial DNA sequence of the Greater Indian rhinoceros, Rhinoceros unicornis, and the Phylogenetic relationships among Carnivora, Perissodactyla, and Artiodactyla (+Cetacea). Mol Biol Evol 13:1167–1173

Zachos FE et al (2013) Species inflation and taxonomic artefacts—a critical comment on recent trends in mammalian classification. Mamm Biol 78:1–6

Zhang X, Pan F, Wu ZW (2015) Complete mitochondrial genome of Callithrix kuhlii (Primates: Callitrichinae) with phylogenetic consideration. Mitochondr DNA. doi:10.3109/19401736.2015.1060452

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Hillman-Smith for providing samples, and R. Emslie, M. Knight, D. Roberts, U. Arnason and Y. Harley for discussions and for critical comments on the manuscript. The work was funded by the National Research Foundation, South Africa, and the University of Cape Town Research Committee. Sequencing used the facilities provided at the Central Analytical Facilities Unit at the University of Stellenbosch, South Africa.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Harley, E.H., de Waal, M., Murray, S. et al. Comparison of whole mitochondrial genome sequences of northern and southern white rhinoceroses (Ceratotherium simum): the conservation consequences of species definitions. Conserv Genet 17, 1285–1291 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10592-016-0861-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10592-016-0861-2