Abstract

Indicators have been proposed as critical elements for sustained climate assessment. Indicators provide a foundation for assessing change on an ongoing basis and presenting that information in a manner that is relevant to a broad range of decisions. As part of a sustained US National Climate Assessment, a pilot indicator system was implemented, informed by recommendations and (Kenney et al. 2014; Janetos and Kenney 2015; Kenney et al. Clim Chang 135(1):85–96, 2016). This paper extends this work to recommend a framework and topical categories for a system of climate indicators for the nation. We provide an overview of the indicator system as a whole: its goals, the design criteria for the indicators and the system as a whole, the selection of sectors, the use of conceptual models to transparently identify relevant indicators, examples of the actual indicators proposed, our vision for how the overall network can be used, and how it could evolve over time. Individual papers as part of this special issue provide system or sector-specific details as to how to operationalize the conceptual framework; these recommendations do not imply any decisions that are made ultimately by US federal agencies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

There is a long history of the development of indicators in a wide range of environmental and social issues—sustainable forestry, the state of ecosystems, sustainable development goals, and economic performance (United Nations Statistical Commission 2017; National Research Council 2015; Heinz Center 2008; Hall 2001). The need for indicators is part and parcel of decision-making about complex systems. It is not possible to know everything about such systems, so a reasonable alternative is to select a subset of measures that provide information on their state, extent, and changes—whether they are physical systems, social-economic systems, or mixes of both.

As might be expected, the diversity of indicator systems is accompanied by a diversity of processes by which indicators have been developed and selected. Just focusing on indicator systems relevant to natural resource management, some have primarily been driven by user input (e.g., the Heinz Center’s State of the Nation’s Ecosystems) that were later adjust based on available data by a smaller expert groups. Others have been primarily expert-driven (e.g., the Montreal process for sustainable forestry). Indicators in other domains, e.g., economic and human well-being, similarly represent a diversity of processes for their formation and use. In general, these indicator efforts, developed for different purposes, have emphasized grouping indicators that exist instead of establishing an intellectual framework that allows for rigorous identification of indicators that exist as well as those that need to be established.

In this special issue, we present the results from a national process that originated in the US Third National Climate Assessment (NCA3; NCA when referring to the effort more broadly) and recommended by the National Research Council (2009). The process by which the indicators were derived and proposed to the US agencies of the U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP) has been described elsewhere (Kenney et al. 2016). The objective of this paper is to recommend categories of indicators to be implemented, their intellectual framework and scientific rationale, and our assessment of their readiness and where new research would make a difference. This paper does not prescribe specific indicators that ought to be included, specific papers in this special issue may provide such recommendations; instead, this paper focuses on the groupings, consistent with the conceptual framework, that one would expect in a more complete indicator system. These recommendations do not imply any decisions that are made ultimately by USGCRP. The paper provides an overview of the system as a whole: its goals, the selection of sectors, our use of conceptual models on which indicators have been based, examples of the actual indicators proposed, and our vision for how the overall network can be used, and how it could evolve over time. Individual papers as part of this special issue provide system or sector-specific details as to how to operationalize the conceptual framework.

2 Overview and goals

There were several goals for this indicator network. Because episodic assessments by the USGCRP are mandated by legislation, most importantly, we proposed to establish replicable baselines for a sustained scientific assessment effort. We recommended establishing baselines because ultimately, the USGCRP assessments must address three substantive science/policy issues:

-

Are multi-stressor impacts related to climate change getting larger, more frequent, more damaging, or less so?

-

As the USA plans and implements adaptation actions, is it becoming more or less resilient to a variable climate system and other related environmental stresses?

-

Given sub-national, national, and international climate plans and commitments, is the nation making progress on greenhouse gas emissions reductions?

The indicator network is thus based primarily on the need to establish consistent baselines against which change and variability can be measured. The information content is meant to illuminate the scientific foundation (in the broadest sense, meaning physical/natural sciences, economics, and social sciences) of discussions about adaptation and mitigation actions.

Establishing consistent baselines against which changes and variability can be measured is clearly a basic scientific goal that needs to be fulfilled so that the hard work of evaluating hypotheses about observed changes can be done. The simple fact of establishing baselines does not, however, imply that there are a priori judgments about those hypotheses. The proposed set of indicators does not presume a singular causal relationship between climate change on global or regional scales or about the role of anthropogenic climate change in any of the indicators that are tracked. And it does not imply that the indicators included in the system are the only components necessary to evaluate management decisions or understand socio-environmental system dynamics or that the goal is to develop a multi-stressor climate change cause-and-effect network. Nor is the intent to develop an early warning system. Though these other goals would have merit for climate-related decision-making, there is a separate, critical need to assess and track whether or not the nation is becoming more resilient across a range of nationally important natural and economic sectors, as intended by the Global Change Research Act (S. 169 - 101st Congress 1990). This indicator system proposes to address this challenge.

3 Design criteria

The system was designed to be end-to-end (Fig. 1) with a focus on impact indicators for national-to-regional sectors and resources of concern. Main criteria for sector inclusion were those sectors or topics previously included in one or more of the NCA. The use of assessment foci reflects the judgment of the federal agencies and their stakeholders about which topics are important enough, and which scientific literature is mature enough, to be included.

Higher-level conceptual model of the indicator system (adapted from Kenney et al. 2014)

A second criterion for selection is that indicators needed to be justified by a transparent model of how each system is structured and how it functions. To aid experts in articulating their knowledge of each system, a conceptual modeling process was utilized. Conceptual models are not new numerical simulation models, but instead articulate the current understanding of each system’s complex state and dynamics, including the indicators that best characterize those elements (National Research Council 2000; Cobb and Rixford 1998). Thus, indicators should be traceable back to an interdisciplinary understanding of each system and an understanding of how the information is meant to be used. The conceptual modeling process also helps to support interdisciplinary team development by creating a shared understanding and language for the most important components of the system.

A third criterion was that indicators needed to have a documented relationship to climate change and variability. In some cases, the indicators directly represent a characteristic of the physical climate system, e.g., radiative forcing caused by human-emitted greenhouse gases. For other indicators, the impacts and responses are multi-stressor where climate is one factor that results in the changes observed. Assessment of multi-stressor effects, impacts, and responses is necessary and consistent with the NCA legislative mandate (S. 169 - 101st Congress 1990) and reports (Melillo et al. 2014; Karl et al. 2009; National Assessment Synthesis Team 2001) and norms of the IPCC scientific assessments (IPCC 1992, 1995, 2001, 2014a, b, 2007). Importantly, regular tracking of physical climate indicators has to established a baseline by which to assess change over time; it is equally important to consistently track multi-stressor indicators to better establish baselines and understand the drivers of change more completely.

A fourth criterion is that the indicators must correspond to phenomena that are of national importance. This is not the same as saying that an indicator must be nationally representative in a statistical sense. Drought, for example, is intrinsically a regional phenomenon, but persistent drought in agricultural regions can just as clearly be a national problem. This criterion is admittedly subjective in some sense. What constitutes a nationally important phenomenon, apart from a geographically national phenomenon, is to some degree a matter of professional judgment of the important system factors. But regardless of the degree of subjectivity involved, applying this criterion means that one need not calculate average national values for phenomena for which the calculation essentially makes no sense.

The final criterion is that the indicators ought to be used. The overall system, because of its scale, cannot be a decision-specific support system. However, the potential decisions where such indicators might be useful need to be considered. To ensure that the indicators are designed to serve as boundary objects (Star and Griesemer 1989), the process of developing indicators should explicitly consider co-production processes that engage both information producers and users (Meadow et al. 2015; Biggs 1989). Coupling co-production with iterative indicator design and improvement allows for the indicators to evolve given rigorous evaluation and refinement as a result of indicator use (Kenney et al. 2016; Gerst et al. 2017; Gould and Lewis 1985). Presenting indicators with accessible metadata that includes the data, methods, and justification allows end-users to customize indicators for their own individual and decision-specific uses while designing a system to be broadly useful for assessing change in nationally important indicators (Wiggins et al. 2018).

4 Intended use and iterative improvement of the indicator system

The indicator system is designed for national, long-term assessment of key indicators of change to support climate assessments. The indicators are meant to be descriptive of nationally important changes to climate, environmental, and economic sectors (Sabine 1912). What is deemed nationally important is based on expert judgment, formalized through the conceptual models for this indicator system (Kenney et al. 2016, 2014). The indicator system is initially recommended to consist of lagging or coincident indicators (indicators that represent past and present conditions). For such indicators, a baseline would be based on a historical average. Though the indicators are intended to be decision relevant, they are not designed to be performance measures of policy effectiveness and should not be a direct function of any specific proposed responses.

The development of the proposed indicators, as articulated in the companion papers in this special issue, began with interdisciplinary teams of experts. Like many such exercises, there was embedded knowledge in those teams about the important components of the system/sector and how indicators in each individual sector are being or might be used. That knowledge is expressed explicitly in the conceptual models for each sector. But while the embedded knowledge and experience of the indicator design teams (Kenney et al. 2016) and best practices were identified and applied to the initial prototypes (Lloyd et al. 2016; Gerst et al. 2017), it does not substitute for an iterative process involving new use cases and new users (Gerst et al. 2017).

With the goal of iteratively improving indicator usability (Gould and Lewis 1985), we engaged two different user groups—scientists and nonscientists. Initial results identified elements (e.g., accessible metadata, text that easily identifies indicator key message, federal agency products, citations) that lead to trust, credibility, and saliency of the indicators and metadata as a linked boundary object (Wiggins et al. 2018; Bechhofer et al. 2010; Star and Griesemer 1989). It additionally focused on the visual design of an indicator to increase understandability and potential utility by diverse audiences (Gerst et al. 2017). Preliminary results indicate notable improvements in understandability through simple design modifications (Gerst et al. 2017; Executive Office of the President 2016); however, additional data are needed to definitively understand the magnitude of the trade-offs between understandability and utility.

Beyond the design of individual indicators, the overall system should also enable combinations of indicators to be developed to address a particular issue or concern on the part of some user community. It is difficult to ensure this capacity exists without specific issues in mind. The simplest case, of course, would be users who seek to understand at a gross level the relationship between regional and/or global temperature changes and some putative response indicator in particular sectors, e.g., coastal ocean color or heating/cooling degree days. There are many possibilities.

We should anticipate that there will be users who will use combinations of indicators from different sectors in ways that will provide information about their own unique decision contexts. The system was designed to promote customization of indicators or combinations of indicators by stakeholders for their own normative goals (Sabine 1912), through linked metadata systems to transparently describe data, methods, and reasoning. This provides the flexibility for the indicator system to meet the assessment goals for the NCA while at the same time being decision relevant through external customization.

5 Conceptual model of the indicator system

The overarching conceptual model for the indicator system is an end-to-end depiction that considers each major component of climate change (Fig. 1). It stresses that the system vision encompasses the creation of indicators for changes and variability in physical systems, in the socio-ecological systems that they affect, and in response strategies. Importantly, arrows between components do not necessarily imply strong cause-and-effect linkages. As detailed above in the design criteria, relationships among indicators may instead represent partial causation, or a strong association that is accompanied by many other causal factors not included in the system.

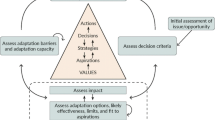

Figure 1 is a hierarchical conceptual model. Lower-level conceptual models were constructed by 13 expert technical teams, which were roughly organized around the sectors and areas of concern represented in the third National Climate Assessment chapters (Fig. 2; relevant papers this issue: Anderson et al. this issue; Arndt et al. this issue; Butler et al. this issue; Clay et al. in review; Hatfield et al. 2018; Lipp et al. this issue; Ojima et al. in review; Peters et al. 2017; Rose et al. this issue; Stanitski et al. this issue; Wilbanks et al. this issue a, b). As the boundaries between systems are fuzzy, some overlap occurred among teams with respect to system limits and indicator recommendations. However, the system addressed by each team can be thought of as its own coupled human-natural systems with individual conceptual models that are informed by guidance given to the teams by the authors of this paper.

Conceptual model of relationships among expert team systems. Solid shapes correspond to papers in special issue (with the exception of adaptation). For the sake of visual simplicity, dotted boxes group similar sectors or areas of concern, which are more likely to share indicator recommendations. Arrows indicate a link between sectors that are a combination of services, drivers, pressures, and responses. Note that each team has created their own conceptual model, which is detailed in the papers in this special issue

Expert team guidance was structured around recent work on human-natural system conceptual models that has pointed to the utility of combining two popular frameworks for decision support, Drivers-Pressures-States-Impact-Response (DPSIR), and ecosystem services (Rounsevell et al. 2010; Reis et al. 2015; Kelble et al. 2013; Poppy et al. 2014; Nassl and Löffler 2015).

DPSIR conceptualizes environmental change through a series of causal relationships (Smeets and Weterings 1999). Environmental change is initiated by drivers such as industrial production to meet a growing population and economy. These lead to pressures on ecosystems (e.g., greenhouse gas emissions), which may change the state of ecosystems such as atmospheric gas composition and temperature. Changes in states may lead to impacts, which may be reduced by responses, specifically mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation acts on pressures (e.g., reducing greenhouse gas emissions) and adaptation improves human-natural system resilience.

Ecosystem services are benefits that society recognizes as directly or indirectly coming from ecosystems (Millenium Ecosystem Assessment 2003). They are generally categorized as product provisioning (e.g., water and food), ecosystem process regulating (e.g., carbon sequestration and climate regulation), supporting production of services (e.g., nutrient cycling), or non-material cultural benefits (e.g., recreation or spiritual). They are linked to the DPSIR framework by noting that change in ecosystem states may lead to change in ecosystem services, and hence impacts (Rounsevel et al. 2010). This is advantageous for an indicator system because it emphasizes that what is ultimately being tracked are trends in services and not impacts per se. Another advantage of this combined framework is that the concept of services also applies to the goods and services produced by technological systems such as infrastructure and human health.

As an example, consider the effect of changing precipitation patterns. Tracing the arrows through Fig. 2, one can develop a narrative of this indicator category flowing through the conceptual model. Pressure on atmospheric composition from emissions changes the state of atmospheric composition, which leads to changes in physical climate state variables such as precipitation. Changes in precipitation in turn put pressure on agriculture and water cycle management, leading to potential impacts on these systems, impacts which might cascade to human health. These impacts might be reduced in the agriculture, water cycle management, and human health systems by adaptation responses. The indicators that would be used to understand precipitation trends or support decisions given these changes are context specific. The ideal indicator representation may be changes in average conditions for one system and extreme events for a different sector.

Using the literature as a point of departure, we provided the following simplified guidance to the expert teams with respect to constructing and to revising their conceptual models. As shown in Fig. 2, teams were asked to consider where their system boundaries lie and how their system interacts with others. Interactions can take the form of (i) providing or receiving ecosystem or anthropogenic services, (ii) experiencing or being the source of drivers and pressures, or (iii) receiving or enacting responses. Teams were also asked to consider internal system dynamics, such as services exchanged among sub-components, especially supporting ecosystem services, as well as pressure and responses. This framework was presented as a way for teams to check the completeness of their conceptual models and indicator recommendations, but not to dictate a template for conceptual model construction. Given the diversity of topics addressed and expertise engaged, this was a necessary and key feature of this effort. As a result, many teams chose to use more discipline-specific frames. However, their recommendations are compatible with the overarching framework shown in Figs. 1 and 2.

6 The human dimensions

Inspection of the conceptual models that have governed the selection of the indicators represented in the subsequent papers reveals the close connections between the human dimension components of each sector and natural processes. For example, the indicators of physical processes, like the summer-time extent of Arctic sea ice, or the release of radiatively important greenhouse gases, consider the interaction of human perturbations with the physical climate system, even if all the processes that modulate that interaction are imperfectly known.

For the indicators of socio-environmental impact sectors, however, the interaction of human dimension elements and the natural processes in each sector are even clearer. For example, the conceptual model used by the forest sector to determine their indicators (Anderson et al. this issue) explicitly shows the interactions with economic demand and management strategies as one of the determinants of forest status, structure, and processes, along with climate and pests. The water sector explicitly considers water management for flood control and availability given seasonal variability (Peters et al. 2017). The economic demand for food and fiber are features in nearly every impact sector. Indeed, for the energy sector, or coastal regions, or health, the human dimensions could be argued to be the most important factor of the proposed indicators (Wilbanks et al. this issue-a; Clay et al. in review).

7 Indicators for the system

The conceptual models in Figs. 1 and 2 are silent on an important issue for the proposed indicator system, which is the spatial/geographic domain that is meant to be covered. From a decision-making perspective, as noted above, the indicators are meant to be relevant to nationally important issues, even though the physical or economic phenomena themselves may be regional. But indicators of certain components of the physical climate system, only a global perspective makes sense.

Table 1 summarizes the overall proposal of indicator categories that should be included in a complete US indicator system that takes into account all the issues outlined above. The categories of indicators are detailed under the higher level conceptual model groupings (Fig. 2). The atmosphere and climate indicators include a set of global and climate impact indicators, primarily for the state of the physical climate system and its anthropogenic forcing either at a global (i.e., global context) or national scale (i.e., climate impacts). The other indicator groupings are sectorally specific, most of which are constrained to either national or regional geographic domains. More specific indicator recommendations are provided in Online Resource 1, Tables OR1–OR7, and in the special issue papers.

In the indicator groupings above, we have not been prescriptive about particular indicators which ought to be included; instead, we have focused on recommending the types of indicators that one would expect to see assessed under these groupings. The papers in this special issue provide recommendations for specific indicators and a fuller representation of the aspirational indicator set.

8 Iterative approaches to constructing the indicator systems

We described above an iterative approach for identifying and improving individual indicators for each impact sector, moving from an initial expert-derived focus to a more inclusive process that incorporates feedback from other stakeholders and decision makers. We envision the initial construction of the overall system to proceed similarly.

Iterative design is a well-established method to cyclically improve the design and utility of user-focused products given user data (Nielsen 1993; Harold et al. 2016; Gould and Lewis 1985). The initial step in the iterative approach applied to the indicator system has been to implement a pilot system of indicators, i.e., a truncated set of indicators representing all the major elements of the system described in Fig. 2. The pilot recommended for this system was published (Janetos et al. 2012; Janetos and Kenney 2015; Kenney et al. 2014; Kenney et al. 2016); the USGCRP considered these recommendations in their implemented proof-of-concept indicator set (https://www.globalchange.gov/explore/indicators).

The pilot is meant to be an experimental system, allowing the implementers to learn from how the initial subset of indicators are accessed and used in order to improve the overall system. This requires sustained commitment to research and evaluation to improve the understandability of the individual indicators and understand stakeholder indicator needs. Subsequent steps would use this evidence to make strategic decisions to build out the indicator system.

In this way, the entire indicator system would follow a similar logic to the development of individual indicators—moving from a more expert-driven system model to a more inclusive system that incorporates the insights, information needs expressed, and uses demonstrated by early adopters. This paper represents a more inclusive set of recommendations to more effectively build out a system of indicators, beyond the pilot implementation, to support the NCA.

9 Evolution of the indicator system and research priorities

The job is not done. There are many gaps in both fundamental understanding and in understanding its usefulness that should be addressed.

We recommend building out the system in several ways. The first and most obvious is adding additional indicators of status, extent, and functioning of important sectors, and possibly even adding additional nationally important sectors to the system. The papers in this special issue demonstrate that there are other possible indicators that are justified by the conceptual models in each sector that could be added.

A second is that the collection of indicators will change as our underlying knowledge of the sectors changes. Any such system is inevitably a function of the current state of our scientific understanding, as much as it is a function of the decisions that face each sector. Thus, we should expect some evolution of the overall system simply because of changes in our understanding of each individual sectors. The indicators for water resources, for example, will eventually need to include recent findings from orbital gravity field measurements, as the scientific community and water managers gain more experience with them. Indicators for adaptation and response strategies will need to take into account the growing experience that cities and other municipalities have with their own climate adaptation plans. The overall system has been intentionally designed to be flexible enough to accommodate new indicators as they become scientifically justified, and as they acquire utility or are needed to support decisions.

A third way the system can and should evolve is to fill a missing element—indicators of responses. There are many individual examples in the literature of what would constitute indicators of mitigation effectiveness and costs (Peters et al. 2017). Even though there are many papers and syntheses of the underlying foundation of adaptation actions (e.g., Noble et al. 2014; National Climate Assessment 2014), there has been no consensus, however, on what summary measures would be required to assess the effectiveness or costs of regional or national adaptation efforts (Moser et al. 2017). Indicators of response are a major need for any system of indicators that seeks to establish baselines for societal effects, as our does, and must be remedied.

Finally, leading indicators (indicators predictive of the future) could be established. The NCA is required to project “major trends for the subsequent 25 to 100 years” (S. 169 - 101st Congress 1990). Though the initial indicator recommendations focus on lagging and coincident indicators, the approach described and conceptual model developed in this paper provides the flexibility to additionally include leading indicators. The inclusion of leading indicators presents additional research challenges that are not trivial, such as the predictive method selected, verification of forecasts, and the development of baselines using historic averages or counterfactuals. However, since all decisions are focused on the future, thoughtful consideration of such indicators could provide actionable information to support policymaking.

As mentioned previously, the process of building out a system can be done incrementally over time. Indicators are foundational sustained assessment products (Buizer et al. 2013), and thus are intended both to provide graphics that assess changes for nationally important sectors and to support understanding and decision-making. At the same time, the evolution of the system will need to be flexible enough to take changes in scientific knowledge and measurements into account. Pragmatically, incrementally building out the indicator system can be strategically prioritized by (1) implementing design theory approaches, (2) using the assessment products to facilitate the development of new indicators, and (3) strategically deploying grants.

First, design theory should be used to evaluate and to iteratively improve indicator design and prioritize the development of new indicators (Harold et al. 2016; Gould and Lewis 1985). The challenge of designing this indicator system is that the audience for, and thus the potential uses of, the indicators is broad and diverse. Thus, like any decision support system (Moss et al. 2014), to ensure its utility, the system has to both be understandable and provide a useful starting point for customizing indicators for specific management purposes. It is unlikely to be perfect when initially constructed; thus, systematic evaluation allows for the components of the indicators to be refined given evidence. In addition to improving indicators within the system, engaging users can provide an approach to prioritize development of new indicators and indicator features, such as web-based customizations or metadata, based on stakeholder information needs.

Second, as new NCAs are planned and implemented, the authors will inevitably have suggestions for new indicators and how existing indicators may need to evolve to keep up with advances in knowledge or to keep pace with adaptation and mitigation responses. The assessment process can capitalize on this expertise by utilizing the authors to provide indicator recommendations for specific sectors and to help construct candidate indicators as part of the development of assessment products. Additionally, because the NCA products are also meant to support decision-making as well as summarize extant science, the audiences for those products also deserve input into the future evolution of the indicator system.

Third, input from stakeholders and authors in the NCA processes should not be the only sources of evolution for the indicator system. There will be a continuing need for innovation from the broader research community, supported by competitively awarded grants and contracts, as for any scientific enterprise. The goal of such activities should be to develop new indicators that can be tested as part of the overall system, and either incorporated or not, as demand and potential use warrants. Targeted solicitations for particular aspects of the indicator system will also be an important tool in the developers’ toolkits. For indicators developed through research to ultimately be operationalized, there needs to be clear guidance provided on the indicator system goals, decision criteria, design considerations, and metadata and method documentation. Otherwise, interesting indicators will be developed that are incompatible with the goals and needs of this system.

10 Conclusion

The proposed system of indicators presented here and in papers in this special issue has been developed to establish consistent, replicable baselines in important sectors against which change can be evaluated. And the relationships between these systems and sectors have been defined using conceptual models.

This indicator system is designed to be multi-stressor, where climate change is one of the important stressors impacting the constituent parts of the sectors and systems. Thus, there is not a predetermined bias for indicators that can be causally attributed to climate as this limits the scope of the system such that it does not meet NCA requirements. Rather, the indicator system should provide an unbiased baseline that can be used for subsequent hypothesis testing. Subject matter experts have taken the lead in identifying potential indicators, but their work will need to be augmented over time by emergent NCA goals and the needs of indicator system users, thus enriching the overall value of the system.

References

Anderson SM, Heath LS, Emery MR, Hicke JA, Little J, Lucier A, Masek JG, Peterson DL, Pouyat R, Potter KM, Robertson G, Sperry J (this issue) Developing a set of indicators to identify, monitor, and track impacts and change in forests of the United States. Climatic Change

Bechhofer S, De Roure D, Gamble M, Goble C, Buchan I (2010) Research objects: towards exchange and reuse of digital knowledge

Biggs SD (1989) Resource-poor farmer participation in research: a synthesis of experiences from nine national agricultural research stations. ISNAR

Buizer JL, Fleming P, Hays SL et al. (2013) Report on preparing the nation for change: building a sustained National Climate Assessment Process. National Climate Assessment and Development Advisory Committee.

Clay PM, Howard J, Busch DS, Colburn LL, Himes-Cornell A, Rumrill S, Zador S, Griffis R (in review). Oceans and coasts indicators: understanding and coping with climate change at the Land-Sea Interface. Climatic Change

Cobb CW, Rixford C (1998) Lessons learned from the history of social indicators, vol 1. Redefining Progress, San Francisco

Executive Office of the President, National Science and Technology Council (2016) Social and Behavioral Sciences Team Annual Report. https://sbst.gov/assets/files/2016 SBST Annual Report.pdf

Gerst MD, Kenney MA, Baer A, Wolfinger JF et al (2017) Effective visual communication of climate indicators and scientific information: synthesis, design considerations, and examples. A technical input report to the 4th National Climate Assessment Report. Version 2.0

Gould JD, Lewis C (1985) Designing for usability: key principles and what designers think. Commun ACM 3166(3170)

Hall PJ (2001) Criteria and indicators of sustainable forest management. Environ Monit Assess 67:109–119

Harold J, Lorenzoni I, Shipley TF, Coventry KR (2016) Cognitive and psychological science insights to improve climate change data visualization. Nat Clim Chang 6(12):1080–1089

Hatfield JL, Antle J, Garrett KA, Izaurralde RC, Mader T, Marshall E, Nearing M, Robertson GP, Ziska L (2018) Indicators of climate change in agricultural systems. Clim Chang:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2222-2

IPCC (1992) Climate change: The 1990 and 1992 IPCC Assessments. IPCC First Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In: Bolin B, the Core Writing Team (eds). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom, and New York, NY, USA, 398 pp.

IPCC (1995) IPCC second assessment climate change 1995: a report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. [Bolin B, Sundararaman N, and the Core Writing Team (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom, and New York, NY, USA, 398 pp

IPCC (2001) Climate change 2001: synthesis report. A Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Watson RT and the Core Writing Team (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom, and New York, NY, USA, 398 pp.

IPCC (2007) Climate change 2007: synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In: Core Writing Team, Pachauri RK, Reisinger A (eds). IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 104 pp.

IPCC (2014a) Climate change 2014: synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In: Core Writing Team, Pachauri RK, Meyer LA (eds). IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp.

IPCC (2014b) Summary for policymakers. In: Field CB, Barros VR, Dokken DJ, Mach KJ, Mastrandrea MD, Bilir TE, Chatterjee M, Ebi KL, Estrada YO, Genova RC, Girma B, Kissel ES, Levy AN, MacCracken S, Mastrandrea PR, White LL (eds) Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part A: global and sectoral aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 1–32

Janetos AC, Kenney MA (2015) Developing better indicators to track climate impacts. Front Ecol Environ 13:403. https://doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295-13.8.403

Janetos AC, Chen RS, Arndt D et al (2012) National climate assessment indicators: background, development, and examples. A technical input to the 2013 national climate assessment report. PNNL-21183. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, p 59

Karl TR, Melillo JM, Peterson TC (2009) Global climate change impacts in the United States. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p 196

Kelble CR, Loomis DK, Lovelace S, Nuttle WK, Ortner PB, Fletcher P, Cook GS, Lorenz JJ, Boyer JN (2013) The EBM-DPSER conceptual model: integrating ecosystem services into the DPSIR framework. PLoS One 8(8):e70766

Kenney MA, Janetos AC et al (2014) National climate indicators system report. National Climate Assessment Development and Advisory Committee

Kenney MA, Janetos AC, Lough GC (2016) Building an integrated US national climate indicators system. Clim Chang 135(1):85–96

Lloyd A, Dougherty C, Rogers K, Johnson I, Fox J, Janetos AC, Kenney MA (2016) Online resource 3: recommended national climate indicators system graphic style guidance. Electronic Supplementary Material published in: Kenney, M.A., Janetos, A.C. & Lough, G.C. Building an integrated U.S. National Climate Indicators System. Clim Chang 135:85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1609-1

Meadow AM, Ferguson DB, Guido Z et al (2015) Moving toward the deliberate coproduction of climate science knowledge. Weather Clim Soc 7(2):179–191

Melillo J, Richmond T, Yohe G (2014) Climate change impacts in the United States: the third National Climate Assessment. US Global Change Research Program

Millenium Ecosystem Assessment (2003) Ecosystems and human well-being: a framework for assessment. Island Press, Washington, DC

Moser SC, Coffee J, Seville A (2017). Rising to the challenge, together. The Kresge Foundation

Moss R, Scarlett PL, Kenney MA, et al (2014) Ch. 26: decision support: connecting science, risk perception, and decisions. In: Melillo JM, Richmond TC, Yohe GW (eds) Climate change impacts in the United States: the third National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, p 620–647. https://doi.org/10.7930/J0H12ZXG

Nassl M, Löffler J (2015) Ecosystem services in coupled social–ecological systems: closing the cycle of service provision and societal feedback. Ambio 44(8):737–749

National Assessment Synthesis Team (2001) Climate change impacts on the United States: the potential consequences of climate variability and change, U.S. Global Change Research Program. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p 620

National Climate Assessment (NCA) (2014), Climate change impacts in the United States. US Global Change Research Program

National Research Council (2000) Ecological indicators for the nation. National Academies Press, Washington, DC

National Research Council (2009) Restructuring federal climate research to meet the challenges of climate change. National Academies Press, Washington, DC

National Research Council (2015) Measuring Progress toward sustainability: indicators and metrics for climate change and infrastructure vulnerability. Meeting in Brief, Roundtable on Science and Technology for Sustainability. http://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/pgasite/documents/webpage/pga_168935.pdf

Nielsen J (1993) Iterative user-interface design. Computer 26(11):32–41

Noble IR, Huq S, Anokhin YA, Carmin J, Goudou D, Lansigan FP, Osman-Elasha B, Villamizar A (2014) Adaptation needs and options. In: Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part A: global and sectoral aspects. In: Field CB, Barros VR, Dokken DJ, Mach KJ, Mastrandrea MD, Bilir TE, Chatterjee M, Ebi KL, Estrada YO, Genova RC, Girma B, Kissel ES, Levy AN, MacCracken S, Mastrandrea PR, White LL (eds) Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 833–868

Ojima DS, Reyes JJ, Aicher R, Archer SR, Bailey DW, Casby-Horton SM, Cavallaro N, Tanaka JA, Washington-Allen RA (in review). Development of climate change indicators for grasslands, shrublands, rangelands, and pasturelands of the United States. Climatic Change

Peters GP, Andrew RM, Canadell JG, Fuss S, Jackson RB, Korsbakken JI, Le Q, Nakicenovic N (2017) Key indicators to track current progress and future ambition of the Paris agreement. Nat Clim Chang 7:118–122

Poppy GM, Chiotha S, Dawson TP, Eigenbrod F, Harvey CA, Honzák M, Hudson MD, Jarvis A, Madise NJ, Schreckenberg K, Shackleton CM, Villa F (2014) Food security in a perfect storm: using the ecosystem services framework to increase understanding. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 369(1639):20120288

Reis S, Morris G, Fleming LE, Beck S, Taylor T, White M, Depledge MH, Steinle S, Sabel CE, Cowie H, Hurley F, Dick JMP, Smith RI, Austen M (2015) Integrating health and environmental impact analysis. Public Health 129(10):1383–1389

Rose K, Bierwagen B, Bridgham SD, Carlisle DM, Hawkins CP, LeRoy Poff N, Read JS, Rohr J, Saros JE, Williamson CE (this issue) Indicators of the effects of climate change on freshwater ecosystems. Climatic Change.

Rounsevel MDA, Dawson TP, Harrison PA (2010) A conceptual framework to assess the effects of environmental change on ecosystem services. Biodivers Conserv 19(10):2823–2842

S. 169 - 101st Congress (1990). Global Change Research Act of 1990

Sabine GH (1912) Descriptive and normative sciences. Philos Rev 21(4):433–450

Smeets E, Weterings R (1999) Environmental indicators: typology and overview. European Environment Agency, Copenhagen

Stanitski DM, Intrieri JM, Druckenmiller ML, Fetterer F, Gerst MD, Kenney MA, Meier WN, Overland J, Stroeve J, Trainor SF (this issue) Indicators for a changing Arctic. Climatic Change

Star SL, Griesemer JR (1989) Institutional ecology, ‘translations’ and boundary objects: amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39. Soc Stud Sci 19(3):387–420

The Heinz Center (2008) The State of the nation’s ecosystems 2008: measuring the lands, waters, and living resources of the United States. The H. John Heinz III Center for Science, Economics and the Environment

United Nations Statistical Commission (2017) Global indicator framework adopted by the General Assembly (A/RES/71/313) https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/Global%20Indicator%20Framework_A.RES.71.313%20Annex.pdf

Wiggins A, Young A, and Kenney MA (2018). Exploring visual representations to support data re-use for interdisciplinary science. Association for Information Science & Technology

Wilbanks T, Conrad S, Fernandez S, Julius S, Kirshen P, Matthews M, Ruth M, Savonis M, Scarlett L, Schwartz, Jr H, Solecki W, Toole L, Zimmerman R (this issue-a). Toward indicators of the resilience of U.S. infrastructures to climate change risks. Climatic Change.

Wilbanks T, Dell J, Arent DJ, Brown MA, Buizer JL, Gough B, Newell RG, Richels RG, Scott MJ, Williams J (this issue-b) Energy system indicators of climate resilience. Climatic Change.

Acknowledgements

The National Environmental Modeling and Analysis Center at the University of North Carolina-Asheville, and specifically Caroline Dougherty, Karin Rogers, Ian Johnson, and Jim Fox collaborated on the prototype indicators visual style for the pilot. Current and previous Indicators Research Team members, who supported this work or indicator expert teams, include Ainsley Lloyd, Allison Baer, Rebecca Aicher, Felix Wolfinger, Omar Malik, Sarah Anderson, Julian Reyes, Samantha Ammons, Amanda Lamoureux, Maria Sharova, Eric Golman, Ella Clarke, Ryan Clark, Christian McGillen, Justin Shaifer, Olivia Poon, Jeremy Ardanuy, Ying Deng, Marques Gilliam, Andres Moreno, Jordan McCammon, Naseera Bland, and Michael Penansky. Members of the Indicators Technical Teams and NCADAC Indicators Working Group are included in Kenney et al. (2014).

Funding

Kenney and Gerst’s work was supported by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration grant NA09NES4400006 and NA14NES4320003 (Cooperative Climate and Satellites-CICS) at the University of Maryland/ESSIC. Janetos has been supported by Boston University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of a Special Issue on “National Indicators of Climate Changes, Impacts, and Vulnerability” edited by Anthony C. Janetos and Melissa A. Kenney

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 29 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kenney, M.A., Janetos, A.C. & Gerst, M.D. A framework for national climate indicators. Climatic Change 163, 1705–1718 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2307-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2307-y