Abstract

The work of the French illustrator and writer Gilles Bachelet has been recognised through numerous awards, but he is not yet sufficiently well known in the critical community. In this article, the multilevel humour that constructs his work is studied, both from an iconic and a textual perspective, as well as the situational humour and the humour of characters that emerge through metafiction, self-referentiality and heteroreferentiality. For this purpose, the theories of humour in children’s literature and the classifications of types of humour offered by different researchers are used as a starting point, and a mixed model of analysis applicable to Bachelet’s work as a whole is proposed. In addition, the analysis of each of the picturebooks is based on the most recent studies on the components of the current picturebook, such as its narrative construction, type of reading, characteristics and organisation of text and image. In this way, the postmodern features of Gilles Bachelet's works, which make him a crossover author, are revealed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In recent decades, several researchers have claimed the presence of humour as one of the main mechanisms of children’s and young adult literature which, however, had not received sufficient attention from the critical community (James, 1986; Cross, 2011). Cross distinguished three main theories of humour (physiological, psychological and social): ‘relief’ theories (which report the benefits of laughter), ‘incongruity’ theories of humour (the subject’s perception of something unexpected or inappropriate) and ‘superiority’ theories (which analyse the pleasure of the cognitive domain of the joke). As far as theories of humour related to developmental psychology are concerned, several researchers apply Piaget’s stages to the understanding of humour or reflect on children’s processes of detecting different humour strategies (notably McGhee, 1977 and Arter, 2019; also Ackerman, 1983 and Kummerling Meibauer, 1999, Pexman et al., 2005; among others).

However, in this study, I will focus on analysis of the humour strategies present in children’s books, which classify types of humour and propose different models of categorisation. In this sense, three types of research can be distinguished.

Firstly, there are studies that analyse a specific corpus of children’s books on the basis of theories of humour from a general perspective. In the 1980s, several proposals emerged that tried to anticipate readers’ responses to humour children’s books (Harrison, 1986) or to classify the types of humour present in children’s literature, according to characters, situations or discourses (Beckman, 1984; Cashore, 2003). Incongruity emerged as one of the main strategies (Vliet, 1986) that continues to be an important focus of analysis today (Marimón Llorca, 2017; Ruiz-Gurillo, 2017; Orozco López, 2020). More recently, studies such as Mallan (1993) have offered a general perspective on humour in children’s literature and its possible applications in the classroom. On the other hand, Dueñas (2011) and Serafini (2015) have applied theories on humour to some of the main cultural references in their language. In line with these studies, the different types of humour in children’s books that these authors use as a starting point will be applied to the analysis of Gilles Bachelet’s work. Beckman (1984) proposes three: humour characters, humour situations and humour discourse; as opposed to the classic irony/parody/satire tripartition (Orozco López, 2020), which is based on the consolidated study by Hutcheon (1984).

Secondly, in the first decades of the twenty-first century, studies on humour in children’s literature began to address more specific aspects. These studies focused on one type of humour and applied it to a particular corpus of children’s books, abandoning the previous general perspective. McGillis (2009) deals with body humour as one of the most important resources in children’s literature, including scatology. Beckett (2001) and Marín Ortiz (2002 and 2004) study parody in the work of different authors, either from the metafictional presence of painting and art or from the use of nonsense, satire and scatology. The analysis of parody will be especially important in this study, since Bachelet uses it as a humour-homage to works of art, historical or metaliterary characters. The scatological content that these researchers analyse is based on the Bakhtinian distinction, already pointed out by Cross (2011), between the "high" and the "low" applied to children’s literature (the low degrades the individual to his contact with the earth and with the lower part of his body—belly, genitals—as opposed to the "high" which elevates him to spirituality and reason. The contemporary grotesque, however, loses the regenerative character it possessed in the Middle Ages, and this is how Bachelet will apply it in his work.

Thirdly, Karababa and Alamdar (2017) identify the resources of humour in the Saftirik series and, from these, draw a model for categorising humour that encompasses three types: visual resources (physical deformation, wild exaggeration, exaggerated reduction, disguise, etc.), verbal resources (nonsense words, denominations different from the original, etc.) and situational resources (surprise situation, blunders, role reversal, etc.). Van Niekerk and Van der Westhuizen (2004) had proposed a model to study humour in children’s stories a priori, i.e., aimed at testing its validity with any work and not in an inductive way. These researchers provide a very detailed subcategorisation, which includes nineteen subcategories of situational humour, twenty-five of verbal humour and a more general view of humour based on typographies and illustrations.

These studies on humour in children’s literature form the first pillar on which the analysis of Gilles Bachelet’s work is based. The second pillar is made up of the main studies on picturebooks and crossover literature, which place him within the framework of postmodern children’s and young adult literature. Thus, insights by Nikolajeva and Scott (2006), Sipe (1998), Sipe and Pantaleo (2008), Van der Linden (2007) and Beckett (2012) aid analysis of Gilles Bachelet’s humour according to its internal and external aspects.

Therefore, on the basis of these multiple studies of humour in children’s literature, a mixed system of analysis of the humour in Gilles Bachelet’s work is proposed, addressing four main blocks: (a) multilevel visual humour and textual humour: metafiction and self-referentiality (b) situational humour: humour transgressions of everyday life and incongruity, (c) character humour: parody and children’s metafiction and (d) characteristics of the postmodern picturebook.

Gilles Bachelet in Current Children’s and Young Adult Literature

Over the last fifteen years, Gilles Bachelet has become one of the leading authors on the international children’s literature scene. His greatest success, Mon chat, le plus bête du monde, was published in 2004 and received the Baobab Picturebook Award that year. From then until the present, he began a series that consolidated his reputation as a major author and illustrator of children’s picturebooks (the most recent, Résidence Beau Séjour, in 2020), which he combines with his work as a professor of illustration at the Cambrai School of Art. With a production of children’s picturebooks that now exceeds ten, in recent decades specialised research on his work has begun to be published, from memoirs and degree theses to exhibition catalogues and magazine issues devoted entirely to his personality and publications. The quality of his picturebooks has earned him a French nomination for the Hans Christian Andersen Prize in the field of illustration in 2022. However, there is still a significant gap between the number of readers, reprints and translations of Gilles Bachelet’s picturebooks and the few analyses of his narrative and iconic strategies within the framework of post-modern children’s and young adult literature.

Among the few publications on Bachelet’s work that can be found, most of them focus on the study of his picturebooks in relation to his biography or on a brief chronological tour through each of his picturebooks (Kotwica, 2013). However, more recent studies point to Bachelet’s place in children’s literature, mainly through his humorous strategies (Van der Linden, 2017; Varrà, 2017) and the multilevel references to cultural, metaliterary or self-referential elements that the French author inserts in his picturebooks (Bruel, 2018; Cabrera, 2012; Vandevooghel, 2014; Stocchino, 2012). Empirical studies are practically non-existent, with some exceptions on reader responses to the humour of his picturebooks in early childhood education (Rérat and Monnier, 2010). A fundamental idea about Bachelet’s work has already been noted and needs further study: the relationship between the French author’s publications on social networks and his picturebooks generates digital epitexts that extend the reading of his works (Kotwica, 2013).

Finally, the interviews with the author that several magazines offer (Lallouet et al., 2018; Lallouet, 2018; Andrieux, 2018) should be taken into account, where he responds to the most important aspects of his work, since they explain the intentions regarding the use of metafiction, self-referentiality or the iconic and literary sources from which Bachelet draws (Kotwica, 2013; Hamelin, 2017).

Humour in the Work of Gilles Bachelet

This study aims to achieve two objectives. The first is to identify the strategies of humour in Gilles Bachelet’s picturebooks in the context of children’s and young adult literature. This objective derives from the first hypothesis: comic textual and iconic characteristics that constitute the main value of Gilles Bachelet’s work and give it its originality in the context of the postmodern picturebook. In turn, this objective is broken down into two micro-objectives: (a) to apply a mixed model of analysis to Bachelet’s humour, based on the proposals validated by current children’s literary criticism, and (b) to verify which principles of the postmodern picturebook appear in his works. A second objective is to pave the way for future empirical studies on the reception of Bachelet’s multilevel humour in primary school classrooms, perhaps making use of the analysis as a theoretical reference. Thus, the second hypothesis is that the multilevel humour of Gilles Bachelet’s work makes him a paradigmatic author of the transversal picturebook.

Multi-level Visual Humour and Textual Humour. Metafiction and Self-referentiality

Gilles Bachelet’s work is characterised, firstly, by the anthropomorphisation of flat, static animals and objects (Nikolajeva and Scott, 2006). The reason he chooses these main characters for his stories, as he argues in interviews (Ville de Ploufragan official, 2019), stems from his personal preference for giving expressiveness to the animals he is obsessed with drawing, an effect he does not achieve with the same intensity through humans (Ville de Ploufragan officiel, 2019). Rudd (2009) suggests that, in the process of anthropomorphising animals and objects in children’s literature, there is an impulse to control both human and animal behaviour and, at the same time, a need on the part of the author to create distance from lesser beings, closer to nature (children, animals) than the "civilised" (adults). This impulse, however, seems to hint at the anxieties of the writers who try to distance themselves from them. In Bachelet’s case, the distance produced by the anthropomorphisation of an animal or an object allows him to recreate situations that would lose their comicality from a human perspective. In Le singe à Buffon, for example, Bachelet narrates the tensions of the everyday life of a father—the character of the Count of Buffon- who is given a monkey to live with him. The monkey is the animalisation of his son Arthur and the Count is a parody of Bachelet himself, as he explains in his interviews. The picturebook is constructed by linking a series of scenes, all of which consist of the monkey’s mischief in his house over the course of a day. The unit of time, kept at twenty-four hours, recreates a father’s routine and the animal character’s ‘low’ drives (doing his business, drinking alcohol, awakening the sexual instinct, etc.). In this case, focalisation is internal as it presents the vision of the father-author (Nikolajeva and Scott, 2006) transmitted through the “collaborative” relationship (Van der Linden, 2007) of the images with the text:

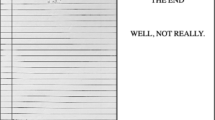

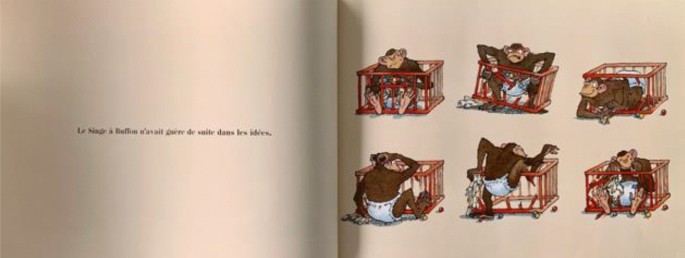

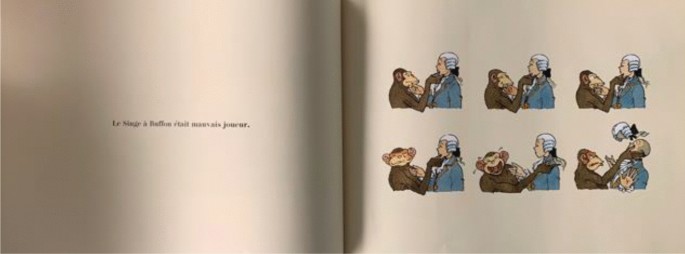

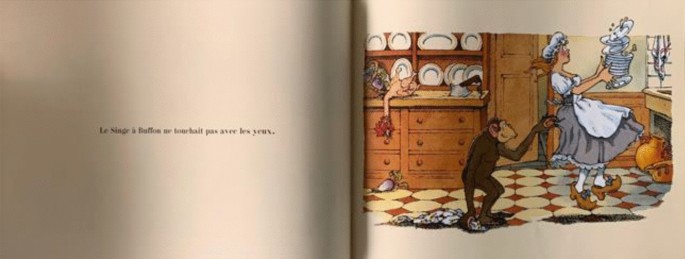

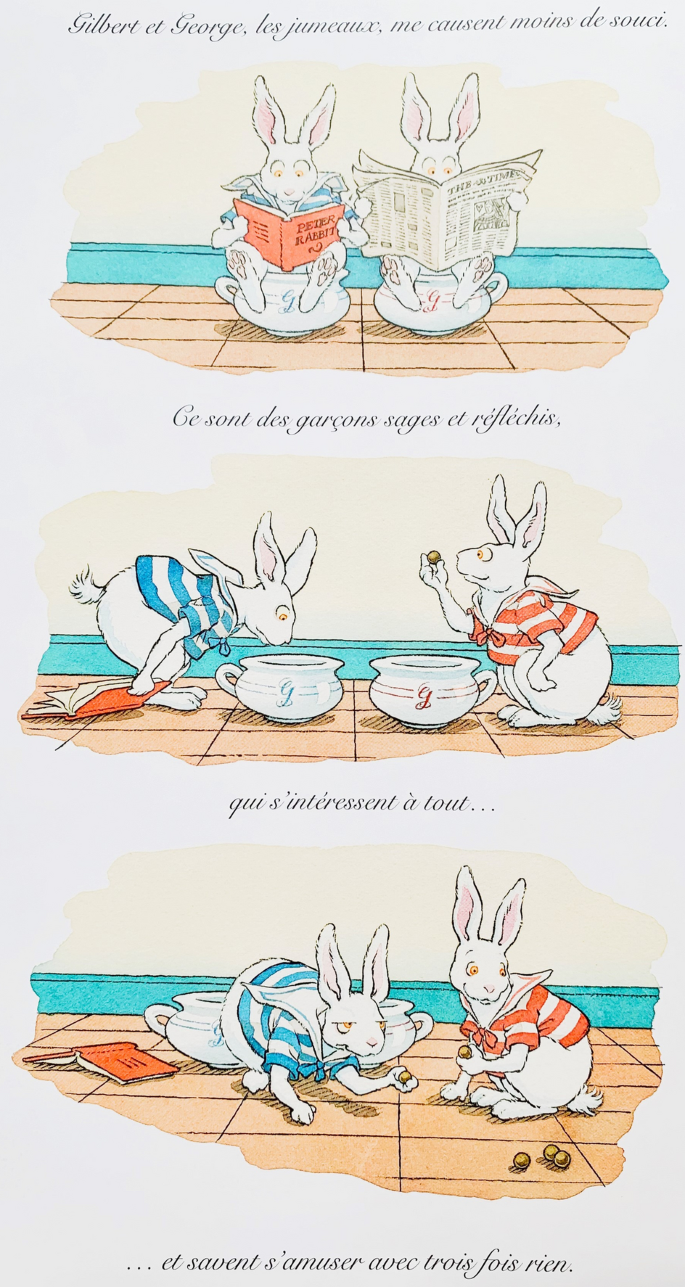

As can be seen in these three scenes (Images 1, 2 and 3) the arrangement of text and image in the picturebook is linear: text on one side of the double page (recto or verso, depending on the case) and image on the symmetrical one, creating a simultaneous succession that represents moments that are disjunct in time but are perceived in a specific order (Nikolajeva and Scott, 2006). Humour is thus created on several levels: a first literal level in which the monkey’s antics are observed with amusement and a second, more complex level, which plays with the double meanings of the expressions. The first level is in line with the more frequent anthropomorphisation of children’s picturebooks characters described by Mallan (1993) as the architects of confronting established order. On the second level, iconic-textual humour intervenes: the literalness of the sentence (“toucher avec les yeux”, for example) is complemented by the information provided by the image (“toucher avec les mains”) or requires decoding the image in order to understand the meaning of the text (“être mauvais joueur” means losing the well-known game “Je te tiens, tu me tiens par la barbichette” which consists of slapping the person who laughs first). On a third, adult level, is the empathy produced by the humorous situation of the routine of a new father, as each scene is a cliché about children’s education (having a bad temper, not touching things with your hands, never wanting to go to bed, etc.). Through this level of humour, the author broadens his readership, as he appeals not only to the feelings of children but also to the empathy of adults, who identify with the character of the Count.

Bachelet (2002), pp. 5–6

Bachelet (2002), pp. 15–16

Bachelet (2002), pp. 19–20

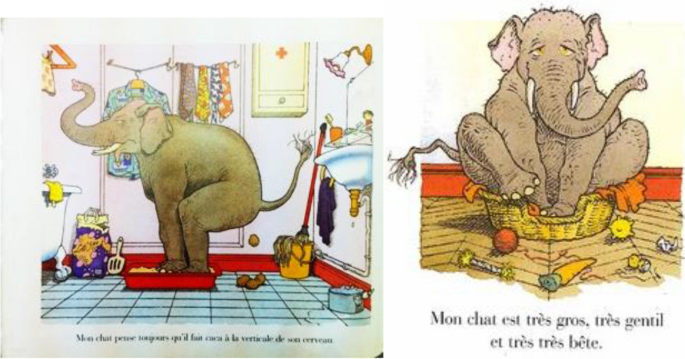

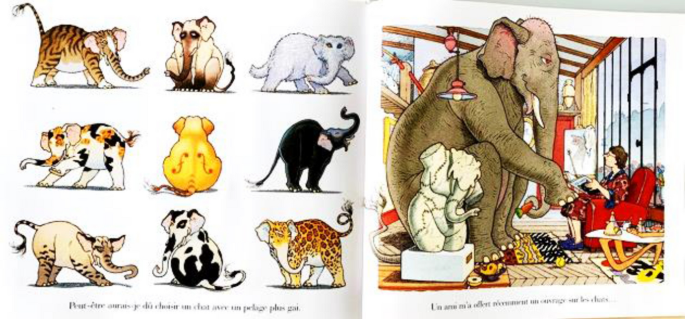

In the case of Bachelet’s famous Mon chat trilogy, the multilevel humour develops in a similar way, except that the arrangement of text and image varies slightly (recto and verso illustrated with the text placed in the footer with a white background). In this case, the first level of humour is the perception of the anthropomorphised animal: an elephant that exceeds the size of its belongings based on the concept of “physical exaggeration” (Karababa and Alamdar, 2017) and human facial expression of the animal—anger, apathy, frustration, satisfaction, etc.—(Images 4 and 5); also appealing to the culture of “the low” already described by Bakhtin and taken up by Cross (2011):

Bachelet (2004), pp. 14–15

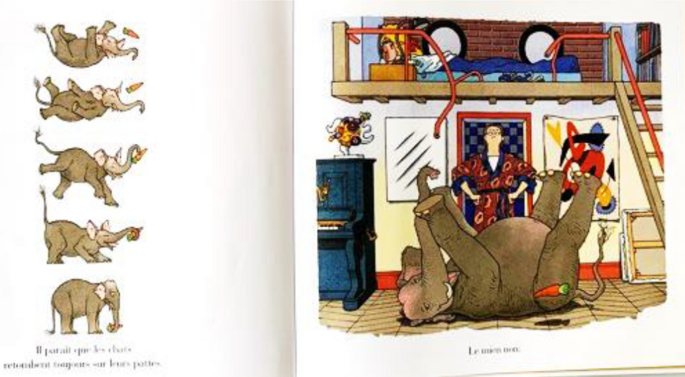

The second level of humour is determined by the text-image relationship. In this case, it is articulated in terms of “collaboration” and sometimes “disjunction” (Van der Linden, 2007). Beckett (2012) analyses this picturebook as one of the examples of crossover literature that introduces pictorial parody and, what is particularly interesting in this section, reflects the contradiction between the meaning of what is narrated and what is represented visually (Image 6):

Comicality arises precisely from the situational absurdity caused by the protagonist’s confused identity and his excessive size compared to that of a cat. This is the narrative core of the work and what researchers have valued most positively about it as a “texte résistant” (Tauveron, 1999; in Rérat and Monnier, 2010) in that it encourages multiple readings, does not exhaust itself in the first linear approach and encourages interaction between pupils as they jointly face the decoding of the picturebook (Rérat and Monnier, 2010).

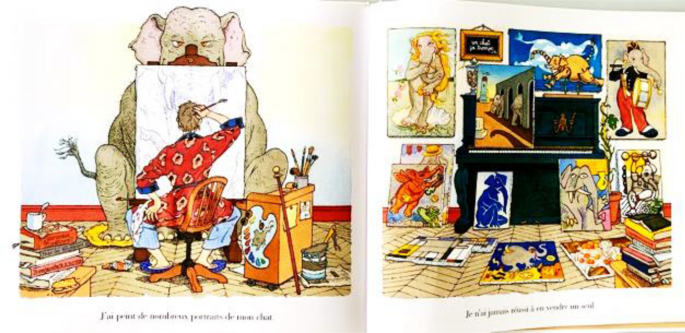

The third level emerges from metafiction and self-referentiality as part of the construction of the picturebook’s meaning. Bachelet inserts himself into the fiction again as the “father” of the animal main character and, at the same time, introduces metafictional references to his work and that of other well-known painters or illustrators (Images 7 and 8):

Bachelet (2004), pp. 16–17

Bachelet (2004), pp. 18–19

In Images 7 and 8, books about the illustrators Bachelet considers most influential in his work (Rockwell, Brunhoff, Rabier, etc.) can be seen stacked on the floor, allowing the adult reader to discover incidental detail into Bachelet’s identity and self-concept as a children’s illustrator.

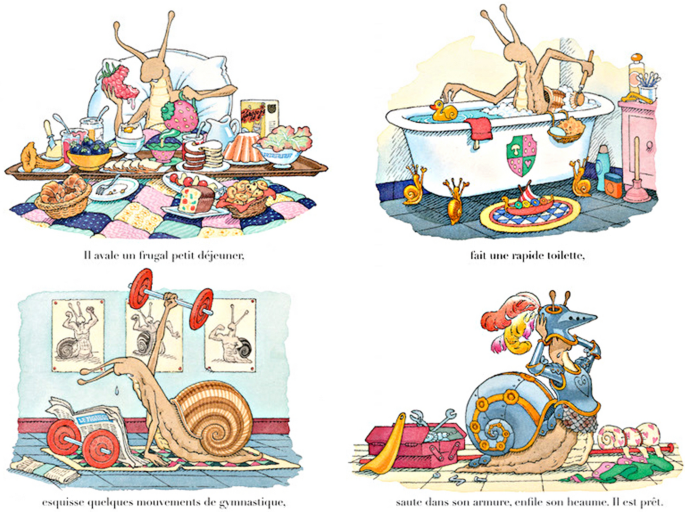

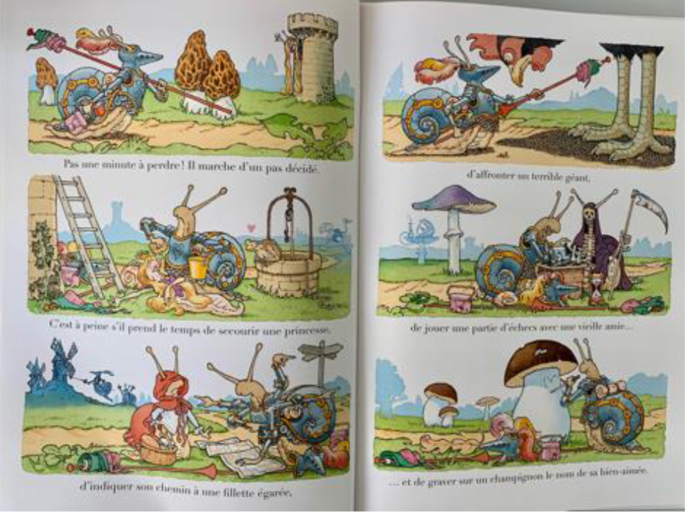

The picturebooks Le chevalier de ventre-à-terre and Résidence Beau Séjour maintain this same scheme of multilevel visual and textual humour with some nuances. In Le chevalier de ventre-à-terre the layout is similar. Bachelet combines the spread with sequences of images that bring movement to the pause produced by the reading of this double page (Nikolajeva and Scott, 2006). The second level of humour is constituted by the disjunctive relationship between text and image, while the first level is determined by the anthropomorphisation of the protagonist procrastinating snail (Image 9):

Bachelet (2014), pp. 4–5

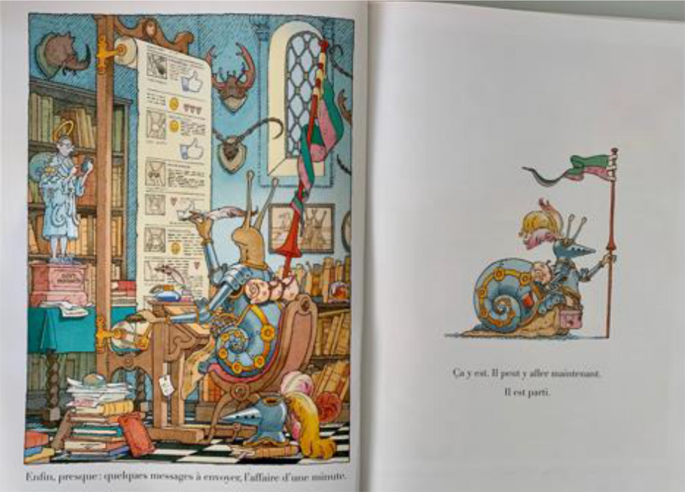

In this case, the third level is determined by the metafictional references to the universe of children’s literature, which Bachelet had already explored in other works, such as Les coulisses du livre jeunesse or Il n’y a pas d’autruches dans les contes de fées. In Le chevalier de ventre-à-terre the snail knight rescues a Rapunzel who has just fallen from the tower, guides Little Red Riding Hood on her way and turns a mushroom into Trajan’s column. The adult reader finds references to contemporary cinema—far removed from a child’s world, one imagines—in the chess game where the snail plays with death, reminiscent of Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (Image 10). On the other hand, self-referentiality once again articulates this third level, since Bachelet becomes the snail by recording the reason that led him to compose the work: the publisher of Seuil Jeunesse requested a new picturebook from the French author after the success of Madame le Lapin Blanc, but he did not finish illustrating it because he was absorbed by his publications on social networks. Reading Image 11, where this biographical component is reflected, demands a level of reading of the comedy that goes beyond the literalness of the image:

Bachelet (2014), pp. 12–13

Bachelet (2014), pp. 6–7

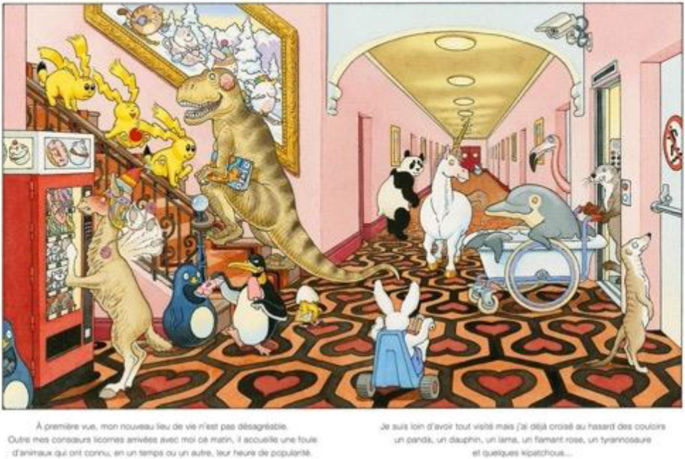

The same three levels of humour can be found in the best-known spread of Résidence Beau Séjour (Image 12):

Bachelet (2020), pp. 5–6

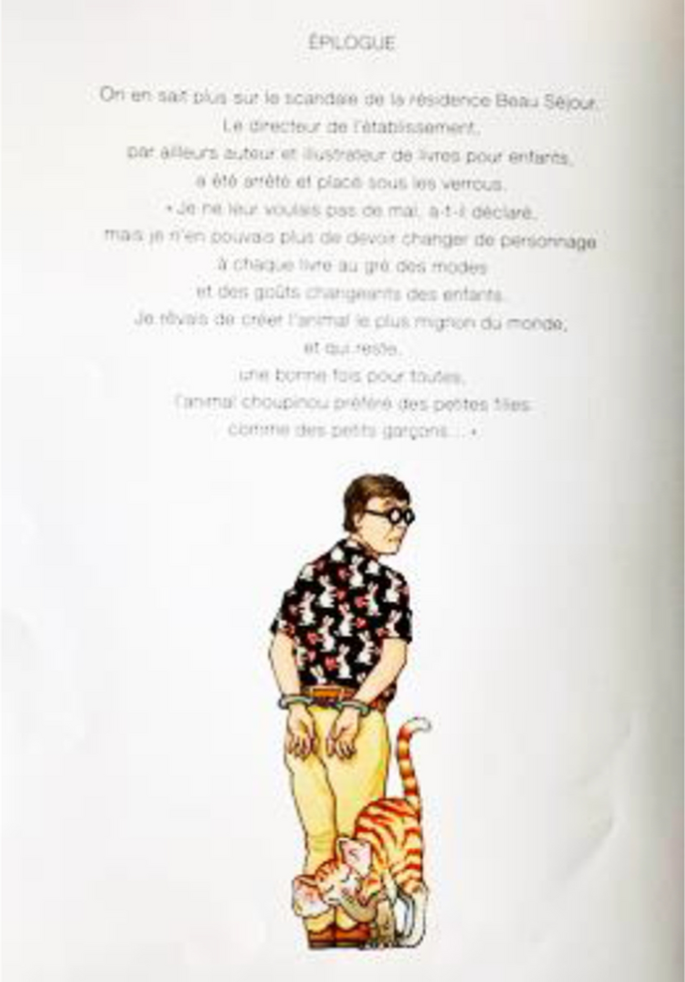

In this case, pause—as a pattern of duration when reading of the image (Nikolajeva and Scott, 2006)—is essential to understand the three levels of humour, which appeal to readers of different ages: the unicorn as a fetish object of current fashion versus the defenestrated stuffed animals of children’s rooms (Pikachu, penguins with whistles, dolphins, etc.). Once again, in this picturebook, the anthropomorphised fantastic animal (unicorn) produces the first level of humour: he goes to the beauty salon, posts for his social networks on a float in the swimming pool, bakes cakes, etc., and the second level is seen through the contradictory relationship between text and image. Bachelet’s evolution in this picturebook is not so much in the humour as in the narrative component, which moves from a succession of everyday scenes to a story based on the Poe’s “final effect” tradition, which takes up self-referentiality: the author who is done with drawing animals that generate success and becomes a mutilator of animal species (Image 13):

Bachelet (2020), p. 27

We return here to Rudd’s (2009) idea set out at the beginning of this section: that anthropomorphisation helps to express more easily the concerns and anxieties of the author himself, who explicitly expresses that the text is an autonomous entity with its own identity, not just a fictional construct (Sipe and MacGuire, 1996, in Sipe and Pantaleo, 2007).

Situational Humour. Humour Transgression of Everyday Life and Incongruity

The second type of humour that appears in Bachelet’s work is situational humour, a subcategory included in many models of child humour analysis (Van Niekerk and Van der Westhulzen 2004; Karababa and Alamdar, 2017). Van Niekerk and Van der Westhulzen (2004) develop situational humour in more detail, with nineteen subcategories found in their corpus that are partially exportable to other books. I will focus on three of them: incongruity, situational irony and awkwardness. Cross (2011) describes different modes of situational humour, such as the “humour transgression of everyday life” (p. 25) transferred to children’s picturebooks. In particular, this author explains the evolution in children’s literature from moralising works that were approached from everyday humour to others that dealt with "serious themes, often encompassing wider social concerns, in which humour is also used to temper or mask the message in some way" (Cross, 2011, p. 25).

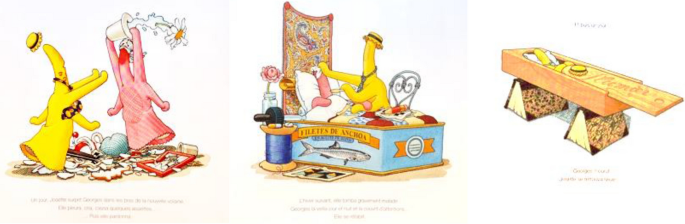

Starting from this idea, I suggest that the humour in Bachelet’s work cannot be classified according to watertight categories, but there is a very clear continuity between some types of humour and others, as they often overlap to generate a unified comedy. One of the clearest examples of situational humour is in Une histoire d’amour, starring a pair of dishwashing gloves. Once again, Bachelet resorts to anthropomorphisation, in this case of objects, and his great achievement is the movement and expressiveness he gives to each of them. The picturebook narrates a love story between the two main characters (Georges and Josette) from the time they meet until Georges’ decease. The situational humour is generated precisely by dealing with serious themes attenuated through visual humour (Images 14, 15 and 16):

In Image 14, Bachelet narrates the moment when Georges commits an infidelity and is attacked by his wife, who learns what has happened. Image 15 shows a winter in which Josette falls seriously ill, and Image 16 closes the love story with Georges’ decease. As can be seen, both visual humour and incongruity attenuate the gravity of the situations addressed: the thimble/pot with which Josette tries to attack Georges and the kiss marks on Georges’ neck (stamped seals) detract from the seriousness of the infidelity and provoke laughter; Josette’s bed/can of anchovies and the coffin/pencil case propped up with books that contains Georges add amusement to the sadness of the scene’s content. Here, the text maintains the gravity of the situation: “Et puis un jour…. Georges mourut. Josette se retrouva seule” (‘And then one day…. Georges died. Josette found herself alone’) (Bachelet, 2017, p. 27) and the situational humour is sustained solely by the visual humour.

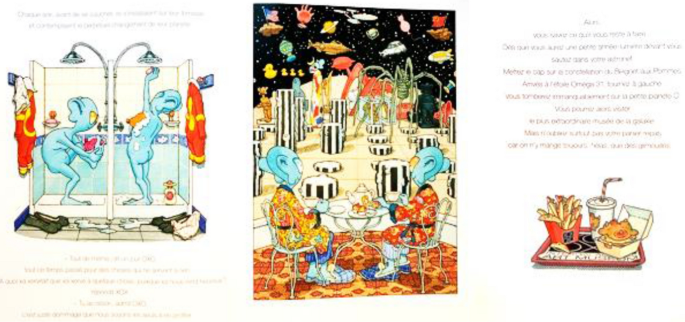

The picturebook Xox et Oxo maintains the situational humour that attenuates the tension provoked by the serious themes, but in a different way from the previous one. In this case, Bachelet introduces his critical stance on the question of the usefulness of art: two extraterrestrials living on planet Ö become sculptors thanks to a 3D photocopier that allows them to reproduce terrestrial objects they see on television. The final reflection on the usefulness of art, the central idea of the picturebook, is presented from a humour perspective with the introduction of objects converted into the universe of the planet Ö and with the transcription of its language, changing the spelling s for x (Images 17 and 18):

Incongruity acts through the introduction of an absurd context in otherwise conventional circumstances (Mallan, 1993; Cross, 2011): the conversion of the most commonly used objects in human routines into the alien world generates strangeness and astonishment and, with it, amusement through the awareness of this absurdity (Arter, 2019). Again, this learning of incongruity is related to the theory of the superiority of children’s humour described by Cross (2011).

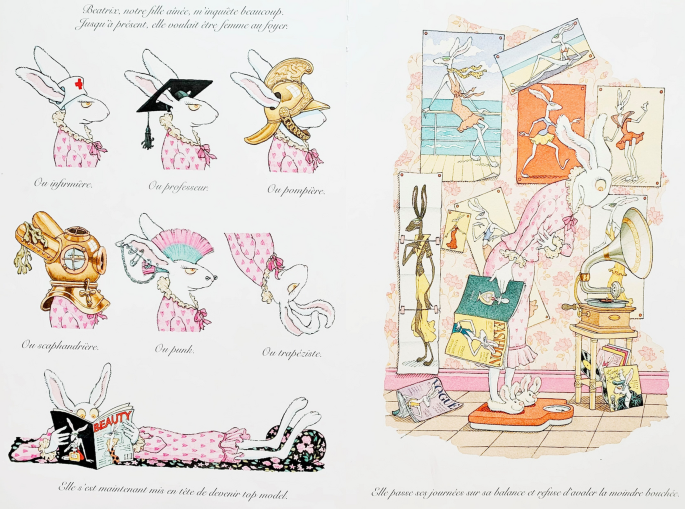

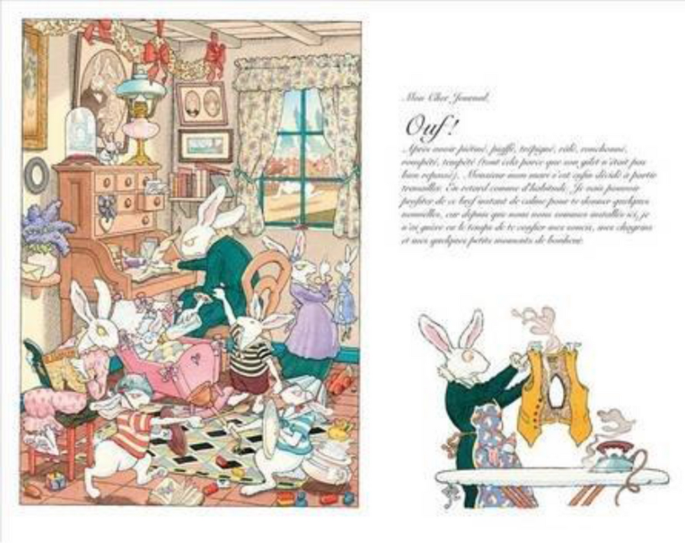

However, the most interesting example of situational humour in Bachelet’s work is to be found in one of his most critically acclaimed works: Madame le Lapin Blanc. In it, he pays homage to Alice’s universe by responding to the White Rabbit's “I’m late” from a feminist perspective, even though Bachelet acknowledged in several interviews (Hamelin, 2017; Ville de Ploufragan officiel, 2019) that his aim was not to reinterpret Alice in a gendered way. The focus is internal, as the everyday life of the White Rabbit's family is narrated by the wife, who transfers her feelings to her diary. The anthropomorphisation of the rabbits generates incongruity through the attribution of disguises and objects that are alien to them, as shown in Image 19, which pictures the different professions in which the eldest sister, Beatrix (the name of the first-born chosen as a tribute to Beatrix Potter), wishes to devote herself:

Bachelet, 2012, pp. 4–5

The scatology shown in Bachelet’s other picturebooks, as mentioned in the previous section, is not a central type of humour in his work, but rather a secondary one (Image 20):

Bachelet, 2012, p. 8

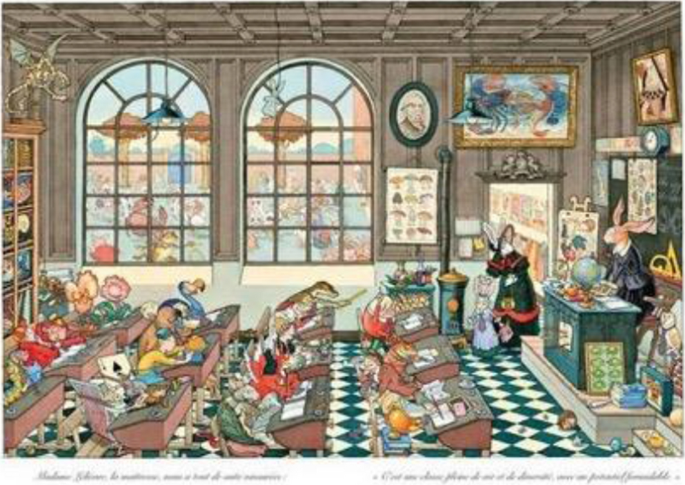

The character who rebels against societal rules from a situational perspective is represented by one of the best double-page spreads in Bachelet’s set of picturebooks, where he introduces metafiction by turning Alice’s characters into the pupils of the school attended by the middle sister (Image 21):

Bachelet, 2012, pp. 10–11

The situational humour that emerges from this double page is, once again, articulated on the basis of a multilevel proposal. The anthropomorphisation and degradation of the animal/child universe, which does not require knowledge of the hypotext, is situated on the first level of humour, while the second level requires the decoding of each of the Carrollian details hidden behind the objects (John Tenniel’s painting, for example), the characters (Mad Hatter, Humpty Dumpty, flowers, Tweedledee and Tweedledum, etc.) and the environments represented. The reading movement will thus not be linear but bidirectional (Nikolajeva and Scott, 2006): it allows for a multiple approach and a perception of the new incongruity in each reading, generated from the discovery of each metafictional reference. In this sense, the second level is both self-referential and heteroreferential: the reader can find references to other picturebooks by Bachelet (Champignon Bonaparte, Il n’y a pas d’autruches dans les contes de fées, etc.), in addition to the homage to Carroll and John Tenniel.

From a more general perspective, situational irony (Van Niekerk and Van der Westhulzen, 2004) dominates the entire picturebook, as it arises from the textual irony of what is narrated through the diary and the visual irony expressed by the gaze of the protagonist. This situational irony has facilitated the reading of Madame le Lapin Blanc from a gender perspective, with the justification that it conveys a feminist claim against the inconsiderate and selfish attitude of the patriarch (Image 22):

Bachelet, 2012, pp. 2–3

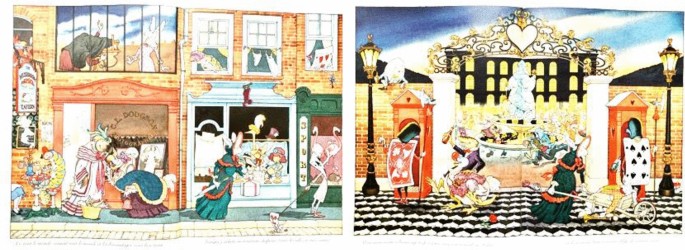

The images that show the situational irony most clearly are two of the most important double-page spreads in this picturebook (Images 23 and 24):

In them, Bachelet draws on the Carrollian universe to ironically reflect the clichés of nineteenth-century and present-day gossiping and patriarchal society: “Mais mon mari a beaucoup trop à faire avec son travail au Palais… et il est même bien souvent obligé de rentrer tard” (‘But my husband has too much to do with his work at the Palace… and he often has to come home late’) (Bachelet, 2012, pp. 24–25). In short, this situational humour is on a second level of decoding that requires the reader to be aware of the social mechanisms that underpin Bachelet’s iconic parody, and not only of the intertextual references to Alice’s universe.

The last subcategory within situational humour is “awkwardness” (Van Niekerk and Van der Westhulzen 2004), and relates this section to the next one. In his picturebooks, Bachelet introduces some situations of awkwardness related to the inflexible mechanisation of a character, in accordance with Bergson’s (1911) ideas that are still taken up by other scholars on humour in children’s literature (Vliet, 1986; Dueñas, 2011; Orozco López, 2020). In the process of anthropomorphising animals or objects, the dehumanisation of the character brings him closer to a mechanical construction, which generates a situational humour that is produced by mechanisation itself and by the absurd situation to which it leads (Image 25):

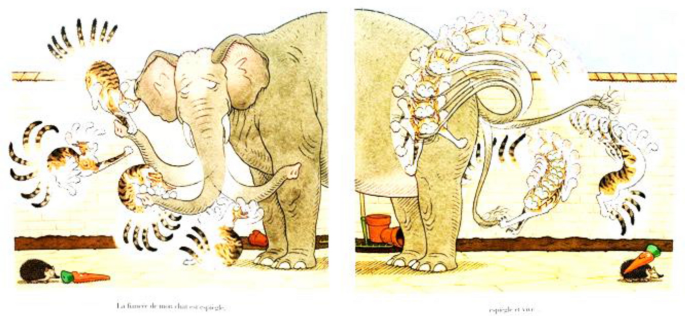

Bachelet (2009), pp. 8–9

As this image from Des nouvelles de mon chat—one of the most moving illustrations in Bachelet’s picturebooks—shows, the humour comes, on the one hand, from the character’s confusion of identity (explained above) and, on the other, from the elephant’s conversion into an object (its trunk and tail resemble two ropes) that allows the cat to play with it. The text reinforces the association of the elephant with an object: “La fiancée de mon chat est espiègle, espiègle et vive…” (‘ My cat’s fiancée is mischievous, playful and lively’) (Bachelet, 2009, pp. 8–9). As can be seen, the text omits the elephant’s feelings and focuses on the cat, who uses it as a tool for her amusement.

However, Bachelet’s picturebooks that make greater use of a character’s mechanisation as a humorous device and generate situational awkwardness are those that construct humour precisely through the character itself, as will be seen in the following section.

Character Humour. Parody and Children’s Metafiction

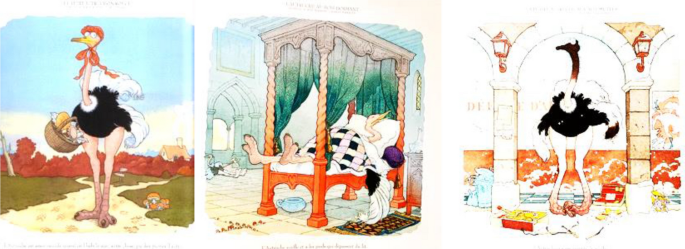

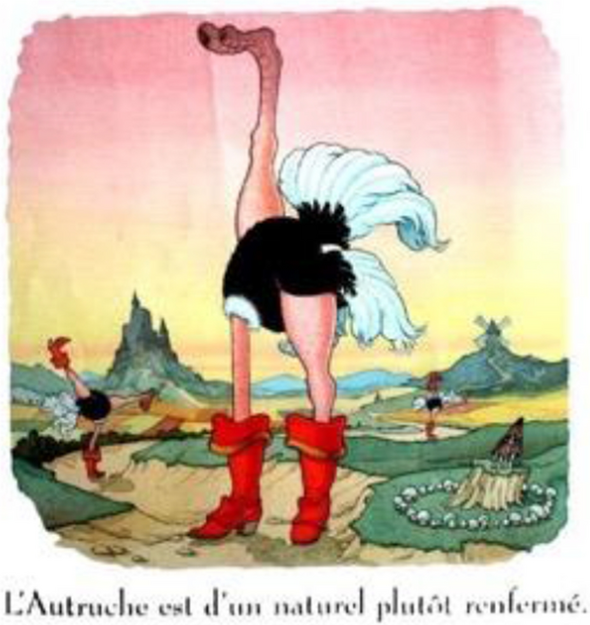

In the case of character humour, Bachelet starts from visual and verbal comedy and produces situational humour, triangulating the comic composition of the work. However, I refer to “character humour” when this type of humour prevails over the two previous ones, articulating the entire composition of the picturebook. In Il n’y a pas d’autruches dans les contes de fées, the square format of the book reinforces its arrangement around the humour of the character, since it is composed of a succession of close-ups of the ostrich disguised as one of the best-known characters from the Grimm and Andersen fairy tales (Images 26, 27 and 28):

The centre of the image is an intertextuality that emerges from character humour, constructed, in turn, through visual humour (disguise and mechanisation of the ostrich) and textual humour—disjunction between text and image and irony in the deconstruction of the story: “L’Autruche n’a pas inventé la poudre” (Bachelet, 2008, p. 5), with the idiomatic? play on words between “avoir inventé la poudre” (‘not being very clever’) and “poudre” (‘gunpowder’, as Andersen’s Little Match Girl) -. Character humour is also constructed on several levels: a first level through disguise and incongruity (with elements that are alien to him and provoke ridicule) and a second intertextual level that depends on the knowledge of the children’s hypotext. This level of recognition remains in the realm of children’s literature, without so many references to adult culture. The character’s visual traits are comical because they are conveyed through repetition and comparison with other literary characters (Nikolajeva and Scott, 2006): long legs, a tendency to hide his head when he is afraid, and a questioning gaze. In this way, the gestures add new visual dimensions of interpretation (Nikolajeva and Scott, 2006) of his awkwardness to those already provided by the excessive size of his body and limbs.

The mechanisation is evident in the interpretation of the ostrich as Puss in Boots, which is based on the hyperbole of its neck, which has become its third leg, thus establishing the analogy with a wheel (Image 29):

Bachelet, 2008, p. 10

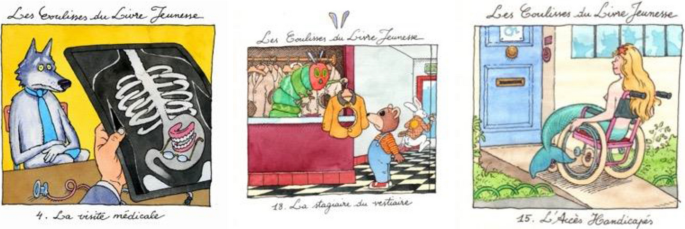

From this triangulation between visual, textual and character humour, Bachelet constructs the parody of fairy tales as a transgressive recreation of the children’s hypotext (Hutcheon, 1984). However, as Hutcheon pointed out, the postmodern parody interprets the original text with a certain degree of homage, not only from critical deconstruction, a resource that Bachelet uses more clearly in Les Coulisses du Livre Jeunesse. In this picturebook, the French author transposes the scenario of children’s stories into the everyday reality of adult life (which he had already tried in Madame le Lapin Blanc):

Little Red Riding Hood’s wolf who goes to the doctor to cure his stomach problems (Image 30) or Carle’s Gluttonous Caterpillar who returns Petit Ours’ jacket with a hole in it (Image 31) are two examples of the substitution of the children’s universe to adult everyday life, through parody and character humour. Interestingly, in this picturebook, Bachelet makes the intertextuality explicit at the end of the illustrations, making it easier for readers unfamiliar with children’s literature. Furthermore, in Image 32 it can be seen again how he uses humour and metafiction to deal with serious issues, such as the analogy between the Little Mermaid’s tail and a physical handicap.

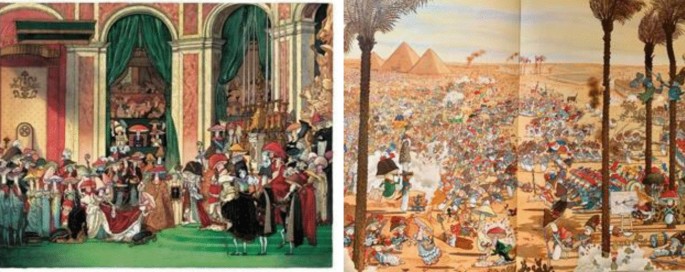

Finally, one of Bachelet’s best picturebooks is constructed precisely through character humour: Champiginon Bonaparte. Bruel (2018) noted that Bachelet’s referential system ranged from open quotation to encryption, parodic evocation and allusion. In this picturebook, he draws on his passion for mycology (whose sources Bruel makes explicit) to construct a critical parody of Napoleon Bonaparte. The focus of the work is the movement of the mushroom as it grows and, above all, the facial expression that denotes ambition, perspicacity and the will to dominate his fellow man. The picturebook is full of self-references to his works and heteroreferences to early 19th-century French history, and pictorial metafiction takes centre stage, with the reproduction on double silent pages of great works of painting in a mycological key, by means of a mise-en-abyme (Images 33 and 34):

Thus, satire and parody are key to Bachelet’s work from pictorial and literary intertextuality, which demands a more complex reading than that of literal humour, since the reader must know the content of the parodied work/biography in order to understand the joke (Beckett, 2001). As Mallan (1993) states, one of the aims of parody is the author’s attempt to persuade the reader to reconsider conventional stereotypes, as well as to find amusement in intertextual connections (McGillis, 2009).

Conclusions

Bachelet’s work shows the fulfilment of the first hypothesis and of the two objectives set out at the beginning: that the originality of the his picturebooks is based on multilevel humour, built on the features of the postmodern, for the definition of which I take the six characteristics described by Sipe and McGuire (1996, in Sipe and Pantaleo, 2008). First, Bachelet blurs the distinctions between ‘high’ and ‘low’ humour through the combination of subtle intertextuality and complex cultural references and the occasional recourse to scatology and sexuality. Secondly, he explores the boundaries between author, narrator and reader, constructing self-referential discourses and animalising their concerns, beliefs and thoughts which he attenuates through visual, textual and situational humour. Thirdly, his works reveal multiple intertextual connections, transferred in an ironic and parodic way. Fourthly, his picturebooks are articulated on the basis of a multiplicity of meanings and non-linear reading directions, which are not exhausted in the first approach to the text but resist its interpretation at different ages. Fifthly, his proposals have a playful character, in which the reader is invited to participate actively in these intertextual searches, in the activation of previous knowledge and in the construction of the meaning of each humour discourse. Sixthly and finally, Bachelet offers a metafictive stance by drawing attention to the text as an independent literary entity, and not as a fictional secondary world (Sipe and MacGuire, 1996, in Sipe and Pantaleo, 2008).

At the same time, as I have suggested, Bachelet’s picturebooks make him a paradigmatic author of the picturebook crossover. Following Beckett’s (2012) considerations and in relation to the characteristics of post-modernity exposed above, they are multilevel works that adapt to all ages because they invite different forms of reading, according to the reader’s experience. They are also “artist’s books”, in that they challenge the limits of the book itself and experiment with format and design, according to the type of humour articulated by each of them. They combine humour through the interaction between text and image with purely visual humour that sometimes relates to wordless picturebooks through the use of silent double-page spreads. References to the fine arts are constant, both from the point of view of parody and metadiscourse and from the allusion to Bachelet’s own stylistic sources or to the artistic movements with which he identifies himself. Finally, his work tackles cross-generational themes previously considered aimed at adults that rarely feature in children’s literature (death, infidelity, imperialism, the difficulty of parent–child relationships), attenuating their seriousness through situational humour.

With all this, the aim of my analysis is to contribute to establishing a theoretical reference on humour in Gilles Bachelet’s work within the framework of postmodern picturebooks and crossover literature. In this way, I hope it will serve as a guide for future empirical studies that transfer the reading of his works to primary school classrooms and analyse children’s reading responses. At the same time, it will allow interested readers to approach Bachelet’s work from a critical perspective, since his consolidation in the publishing scene is already evident.

Change history

25 September 2021

There is typo error in CV part, right at the end line, it includes a sentence from the reviewer" now it has been corrected

References

Ackerman, Brian P. (1983). Form and Function in Children's Understanding of Ironic Utterances. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 35, 487–509.

Andrieux, Brigitte. (2018). Irrésistible Gilles Bachelet. La Revue Des Livres Pour Enfants, 301, 104–125.

Arter, Lisa M. (2019). Linguistic Gymnastics: Humor and Wordplay in Children’s and Adolescent Literature. In Eleni Loizou and Susan L. Recchia (Eds.), Research on Young Children’s Humor. Theoretical and Practical Implications for Early Childhood Education, (pp. 169–183). Cham: Springer.

Bachelet, Gilles. (2002). Le Singe à Buffon. Paris: Seuil Jeunesse.

Bachelet, Gilles. (2004). Mon Chat, Le plus Bête Du Monde. Paris: Seuil Jeunesse.

Bachelet, Gilles. (2005). Champignon Bonaparte. Paris: Seuil Jeunesse.

Bachelet, Gilles. (2008). Il N’y a Pas D’autruches Dans Les Contes De Fées. Paris: Seuil Jeunesse.

Bachelet, Gilles. (2009). Des Nouvelles De Mon Chat. Paris: Seuil Jeunesse.

Bachelet, Gilles. (2012). Madame Le Lapin Blanc. Paris: Seuil Jeunesse.

Bachelet, Gilles. (2014). Le Chevalier De Ventre-à-Terre. Paris: Seuil Jeunesse.

Bachelet, Gilles. (2015). Les Coulisses Du Livre Jeunesse. Paris: Seuil Jeunesse.

Bachelet, Gilles. (2017). Une Histoire D’amour. Paris: Seuil Jeunesse.

Bachelet, Gilles. (2018). XOX et OXO. Paris: Seuil Jeunesse.

Bachelet, Gilles. (2020). Résidence Beau Séjour. Paris: Seuil Jeunesse.

Beckett, Sandra. (2012). Crossover Picturebooks. A Genre for All Ages. New York: Routledge.

Beckett, Sandra. (2001). Parodic Play with Paintings in Picturebooks. Children’s Literature., 29, 175–195.

Bekman, Aileen K. (1984). The psychology of humor and children’s funny books: where do they meet? Paper presented at the 17th Annual Meeting of the Keystone State Reading Association, Hershey PA, 11–14 November; microfilm ED 258194.

Bergson, Henri. (1911). Laughter; An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic. London: Macmillan.

Bruel, Christian. (2018). Les Histoires Naturelles de Gilles Bachelet. La Revue Des Livres Pour Enfants., 301, 126–137.

Cabrera, Roberto. (2012). Duplicados del yo Autorial en la Literatura Infantil: Maniobras Autoficcionales en Anthony Browne y Gilles Bachelet. Revista Laboratorio, 7, 1–19.

Cashore, Kristin. (2003). Humor, Simplicity and Experimentation in the Picturebooks of Jon Agee. Children’s Literature in Education, 34(2), 147–181.

Cross, Julie. (2011). Humor in Contemporary Junior Literature. New York: Routledge.

Dueñas, José Domingo. (2011). Fomentar el Deleite: el Humor en la Literatura Juvenil. ANILIJ (anuario De Investigación En Literatura Infantil y Juvenil)., 9, 21–31.

Hamelín. (2017). Nella testa di Gilles Bachelet. Intervista Con L’autore. Oblò, 1, 28–53.

Harrison, James. (1986). Reader/listener Response to Humour in Children’s Books. CCL, 44, 25–32.

Hutcheon, Linda. (1984). A Theory of Parody. The Teachings of Twentieth-Century Art Forms. New York: Routledge.

Karababa, Safiye, and Alamdar, Suphi Günes. (2017). Humor in Children’s Literature Books: Saftirik Example. International Journal of Language Academy, 5(8), 331–347.

Kotwica, Janine. (2013). Gilles Bachelet. Humour Toujours. Catalogue de l’éxposition. Amiens: Yvert-Ympam.

Kummerling Meibauer, Bettina. (1999). Metalinguistic Awareness and the Child’s Developing Concept of Irony: The Relationship Between Pictures and Text in Ironic Picturebooks. The Lion and the Unicorn, 23, 157–183.

Lallouet, Marie. (2018). Éditer Gilles Bachelet. Entretien Avec Céline Ottenwaelter. La Revue Des Livres Pour Enfants, 301, 156–164.

Lallouet, Marie, et al. (2018). La Revue des Livres pour Enfants. (301), June, 100–170.

Mallan, Kerry. (1993). Laugh Lines: Exploring Humour in Children’s Literature. Literature Support Series. Newtown: Primary English Teaching Association.

Marimón Llorca, Carmen. (2017). Estrategias para Construir El Humor. Las Figuras Retóricas en Relatos Humorísticos de Niños de 8 y 12 Años. CLAC, 70, 61–80.

McGhee, Paul E. (1977). A Model of the Origins and Early Development of Incongruity-Based Humour. In Chapman and Foot (Eds.), It's a Funny Thing, Humour (pp. 27–36). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

McGillis, Roderick. (2009). Humour and the Body in Children’s Literature. In Matthew O. Grenby and Andrea Immel (Eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Children’s Literature, (pp. 258–271). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nikolajeva, Maria, and Scott, Carole. (2006). How Picturebooks Work. New York: Routledge.

Orozco López, María Teresa. (2020). Humor and Carnival in Children’s Literature. Sincronía, XXIV, 78, 453–467.

Pexman, Penny, Glenwright, Melanie, Krol, Andrea, and James, Tammy. (2005). An Acquired Taste: Children’s Perceptions of Humour and Teasing in Verbal Irony. Discourse Processes, 40(3), 259–288.

Rérat, Justine and Monnier, Christelle. (2010). “Un chat, ça trompe énormément”. Étude comparative des réceptions d’un album de jeunesse dans des classes de 1P/2P et 5P. II Congrés International de Didactiques, 1–7.

Rudd, David. (2009). Animal and Object Stories. In Matthew O. Grenby and Andrea Immel (Eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Children’s Literature, (pp. 242–257). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ruiz-Gurillo, Leonor. (2017). Humour Production in Children’s Narratives in Spanish. Caleidoscopio, 15(2), 222–231.

Serafini, Frank. (2015). Humour in Children’s Picturebooks. The Reading Teacher, 68(8), 1–10.

Sipe, Lawrence R. (1998). How Picturebooks Work: A Semiotically Framed Theory of Text-Picture Relationships. Children’s Literature in Education, 29(2), 97–108.

Sipe, Lawrence R., and Pantaleo, Sylvia (Eds.). (2008). Play, Parody and Self-Referentiality. New York: Routledge.

Stocchino, Julie. (2012). L’univers de Gilles Bachelet: le jeu avec les références communes. Mémoire de recherche, Université de Montpellier II. Inédita. Recuperado de [https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-00841006].

Van der Linden, Sophie. (2007). Lire l’album. Le Puy-en-Velay: L’Atelier du Poisson Soluble.

Van der Linden, Sophie. (2017). Gilles Bachelet, Made in France. Oblò, 1, 20–27.

Vandevooghel, Louise. (2014). L’intertextualité à travers les âges. Gilles Bachelet, un créateur d’albums intergénérationnels. Mémoire de Máster, deuxième année. UFR de Léttres Modernes. Lille 3-Charles de Gaulle. Inédita.

Varrà, Emilio. (2017). Il Controcanto Paródico Di Gilles Bachelet. Oblò, 1, 8–19.

Ville de Ploufragan officiel. (2019). Rencontre avec Gilles Bachelet, auteur jeunesse. (Accessed January 24th, 2021). From https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=540249466526356.

Vliet, Ann. (1986). Me Parece Que Aquí Algo No Está Bien: Incongruity as the Basis of Children’s Humour. Studies in American Humor, 2(5), 299–306.

Van Niekerk, Jani, and Van der Westhuizen, Betsie. (2004). Humour in Children’s Literature in the Tertiary and Intermediate Phases of Language Education. Literator, 25(3), 151–179.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Diana Muela Bermejo is a graduate in Spanish Philology (Extraordinary Prize) and PhD in Spanish Philology (with International Mention and Academy of Hispanism award) from the University of Zaragoza. She currently works as a PhD Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Education, where she teaches classes in Children’s and Youth Literature in Primary Education, among other subjects. She is a specialist in children’s and youth literature of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and has devoted special attention to the recovery of children’s heritage, to the analysis of children’s literary texts from a comparative perspective, and to children’s and youth theatre. This work is part of the research line of the ECOLIJ (Communicative and Literary Education in the Information Society, Children's and Young Adult Literature in the construction of identities) group of the Government of Aragon, of which the author is currently a researcher.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Muela Bermejo, D. Humour in Children’s and Young Adult Literature: The Work of Gilles Bachelet. Child Lit Educ 54, 73–96 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-021-09463-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-021-09463-8