Abstract

Sharing research data between researchers is becoming a requirement for open science in the field of clinical phonetics and speech and language pathology. An initiative entitled DELAD was started in 2015 to provide researchers a platform to discuss ongoing technical, legal and ethics issues related to sharing recordings of speech disorders, and to assist them in archiving their data for sharing with colleagues in the field. The ultimate goal of data sharing is to enhance research and teaching in the area of speech disorders. This paper first presents DELAD and its history and previous accomplishments. Then the recent work achieved by the DELAD steering group in providing information or recommendations in three areas are discussed: (1) speech annotation and automatic annotation mining, (2) consent and data storage, and (3) a role-play activity for learning data protection assessment. DELAD is an active community and researchers who share similar interests are welcome to join the (ad)venture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent years, advancements for open science have been pursued rigorously in many research fields. To increase reproducibility, evaluation, and even economic efficiency of published research, sharing data between scientists is becoming a requirement. Researchers of disordered speech are committed to the goals of open science, but face particular demands related to sharing sensitive data (i.e., data that should be protected against unwarranted disclosure). Organisations (e.g., TalkBank, see below) have pioneered in developing practices and processes for data sharing. At the European level, a complementary initiative was started under the name DELAD which stands for Database Enterprise for Language And speech Disorders. In the current paper, we first elaborate about DELAD and its history, noting what has been accomplished so far. We then discuss the use of techniques as well as software tools and file formats for speech annotation and automatic annotation mining. This is followed by a discussion on ethical guidelines related to participant recruitment, type of data, management of research data, and data access and secondary analysis, with suggestions on how to create research information sheets and consent forms. We then report on the use of an educational role-playing exercise for understanding data protection assessment. Our ultimate goal is to encourage and assist researchers in the field of clinical phonetics and speech and language therapy to enrich, document, and share their corpora of speech of individuals with communication disorders (CSD).

2 What is DELAD?

DELAD developed from a series of workshops starting in 2015 and continuing to the present. The primary goal of DELAD is to provide a platform for archiving and sharing disordered speech data from all language communities in order to enhance research and teaching, and to support the development of therapeutic practice in communication disorders (Lee et al., 2022). The spirit of this venture is captured by analogy with the Swedish word delad, which means ‘shared’.

The DELAD initiative originated with Professors Martin Ball and Nicole Müller and has been developed to its current form by the international membership of a series of open workshops (six to date) and the DELAD steering committee (http://delad.net). The original initiative was termed the DisorderedSPeechBank (Ball et al., 2016), thereby indicating a defining focus on disordered speech data, and at the same time referencing TalkBank, the language and communication disorder database organized by Professor Brian MacWhinney at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, USA (https://talkbank.org; see also MacWhinney et al., 2013). Ball et al. (2016) envisaged a digital archive of disordered speech samples that would include audio and video files, transcription, and annotation files relevant to phonetic and acoustic analysis, and imaging data from ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, electropalatography and other technologies relevant to the investigation of disordered speech data. Control data may also be contributed, but the focus remains on disordered speech. See van den Heuvel et al. (2018) and Lee et al. (2022) for further summaries of the DELAD initiative.

2.1 What has DELAD achieved?

Given the privacy concerns of contributors, in addition to the legislation of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, 2016) legislation that came into effect in 2018, the sharing of personal and potentially sensitive data requires careful consideration. DELAD sought advice from researchers, speech and language clinicians, clinical managers, and legal/ethical specialists in order to identify a database infrastructure that could balance security with different levels of accessibility as dictated by contributors and GDPR requirements. DELAD now coordinates with the CLARIN K-Centre for Atypical Communication Expertise (ACE; https://ace.ruhosting.nl) which provides secure, GDPR-compliant data storage and access for DELAD databases (van den Heuvel et al., 2020). Through ACE, DELAD links with The Language Archive (TLA) at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics (https://tla.mpi.nl) and TalkBank so that researchers can share their CSD databases at these resource centres.

The DELAD website (http://delad.net) functions as a portal for information on different aspects of the DELAD initiative. The website provides information on joining DELAD and attending workshops, an inventory of speech datasets that can be shared (https://delad.ruhosting.nl/wordpress/data-inventory/), publications and workshop reports, and guidelines for designing consent and storage documents and contact details (detailed in Sect. 4) to researchers who wish to contribute data to the initiative. There is also a use case example about dataset sharing via DELAD (https://delad.ruhosting.nl/wordpress/publications/; see also Lenardič, 2020) that researchers can explore. It demonstrates the access pathways for data that is registered with ACE and TalkBank with audio available by registration and permission from TLA. Data structure and consent recommendations follow CLARIN requirements that ensure data security and GDPR compliance. Another example of data sharing through the present initiative can be found in Nodari et al. (2021).

A valuable feature of the DELAD initiative is the opportunity for knowledge and skills development provided by workshops with European and international colleagues. DELAD workshops are open to all those who are interested in collecting and archiving CSD. Contributors include academic researchers, clinicians, legal experts, database experts, archivists, and signal analysts. Past workshops have enabled informed discussion and decision-making to support our progress, and opportunities for networking with colleagues and organisations such as CLARIN, TAPAS (Training Network on Automatic Processing of PAthological Speech, and ELRA (European Language Resource Association). Workshops to date have been productive and stimulating in terms of content and developing collegial networks.

3 Annotation tools and techniques for disordered speech

In this section, we highlight selected features of annotation tools, data formats and procedures that can be useful at various stages of designing, developing, processing, and analysing speech resources with a special focus on resources for disordered speech.

3.1 Requirements and examples

Most annotation tools used in phonetic research can be successfully used for annotating the audio and/or video recordings of both typical and disordered speech. The commonly available tools usually include functionalities enabling multilayer annotations based on synchronized inputs representing different components of spoken communication. The labelling schemes may involve both linguistic (e.g., phrases, words, syllables, individual sounds) and para/extralinguistic features (e.g., hesitation markers, physiological sounds produced by speakers or voice emotion correlates). Apart from permitting various annotation mining and speech analysis options, the tools also feature visual representation of the multilayer annotations that are time-aligned with the speech signal display; for example, in the form of oscillograms or spectrograms as in Praat (Boersma & Weenink, 1992–2021) or Annotation Pro (Klessa et al., 2013). In cases where a visual component is necessary at the stage of annotation, the ELAN software tool (Wittenburg et al., 2006) can be used because it supports the display of video files and multilayer annotation of video recordings (e.g., adding annotation layers including gesture or mimicry labels).

At some stage of the development of experimental procedures, it might be necessary to adjust certain elements so that they are better suited to reflect disordered speech. One level of adjustment is the use of an extended version of the phonetic alphabet such as ExtIPA (Extensions to the International Phonetic Alphabet; see Ball, 2021; Ball et al., 2018) which enable transcribers to mark additional information characteristics for atypical phenomena in speech along with the standard transcription labels (cf. e.g., Duckworth et al., 1990; Lorenc, 2016). Another kind of adjustment is to allow signalling uncertainty in the transcribed material. Uncertainty is frequently reported by annotators of spontaneous speech recordings and also those of disordered speech. The reasons for uncertainty include overlapping of neighbouring speech sounds (e.g., due to coarticulation), overlapping of speech and noise events, and the occurrence of any unexpected phenomena in the speech signal, all resulting in ambiguity of certain segment boundary positions (some of which are in fact continuous transitions between sounds and could be interpreted as transition areas instead of boundary points). Uncertainty markers may be included in the extended version of the phonetic alphabet or by means of using software tools supporting annotation of uncertainty. One such tool is SPPAS (Bigi, 2015), a freely available package that includes options to mark selected annotation boundaries as uncertain. The annotations can then be automatically searched for uncertainty markers in order to either enlist the “uncertain” boundary positions and to determine their appropriate location or, on the other hand, to confirm the status of certain boundary positions as inherently indeterminate (ambiguous), at least for a particular purpose (Bigi, 2021).

3.2 Discrete, continuous, and mixed rating scales in speech annotation and perception tests

Many features of spoken utterances can be annotated using labels assigned to predefined categories or classes. When recordings are annotated with the use of software tools, individual labels representing those categories or classes are attached to subsequent segments (or boundary-delimited intervals). An example of such category-based labelling would be the transcription labels denoting syllables, sounds, words, or whole phrases time-aligned with the speech sound signal. Other categorical (discrete) labels often used in multilayer annotations may involve synchronized labels that represent parts of speech or discourse turns. Discrete labels are also used to annotate gestural behaviour and facial expressions, for example, to mark gesture types, gesture phases or functions (e.g., Ferré, 2012; Jarmołowicz-Nowikow & Karpiński, 2011). However, when we consider the features of spontaneous or disordered speech, it often turns out that continuous dimensions or transitions are more suitable than distinct categories. They appear particularly useful to label some of the paralinguistic or extralinguistic features, for example, those related to voice quality, individual voice characteristics or speaker’s states and attitudes.

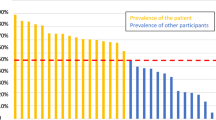

Figure 1 depicts examples of graphical representations of continuous and mixed rating scales available in the Annotation Pro software tool (Klessa et al., 2013). The left-most example shows a feature space for labelling emotions using two dimensions of activation and valence (see e.g., Smith & Ellsworth, 1985). The image in the middle represents a mixed rating scale: discrete (10 distinct categories for emotion perception labelling are represented in the pie chart) and continuous (the distance from the centre of the circle refers to the emotion intensity) (cf. Ekman, 1992; Plutchik, 1982). The right-most image represents the continuum of phonation types based on Ladefoged (1971) referring to the degree of openness. Technically, the graphical representation can take any form desired by the user. It is possible to use one of the built-in images such as those in Fig. 1 or to design and upload a custom-made image (in the form of a JPG or PNG file), tailored to the needs of a given study. The annotation procedure consists of clicking the picture and thus marking one or more points in the picture. The result is added as a segment label on the annotation layer, in the form of a pair of Cartesian coordinates for each of the points.

The availability of different rating scales may be profitable both at the stage of developing richly annotated corpora and perception studies (see also an emotion perception study using the FEELTRACE software tool by Cowie & Douglas-Cowie, 1996). It is important, however, that the results of annotation based on various rating scales are stored with the use of such file formats that the information coming from different sources can be combined within a common workspace. This way, the potential correlations and dependencies between them can be inspected and expressed using approaches based on both qualitative (e.g., visual inspection of multilayer annotations) and quantitative (e.g., statistical) measures (see also below).

3.3 Interoperability of annotation data formats

When considering the use of automatized procedures as an enhancement for the development and analysis of speech resources, it should be noted that many automatic tools are designed to deal with well-formed utterances. Furthermore, the level of background noise in the recordings should be minimized or controlled in a way that they do not interfere too much with the target speech signal. In the case of disordered speech data, not only are atypical events present in the speech signal itself (due to speech production issues) but often the samples are collected outside of recording studios, in fieldwork environments (at hospitals, schools, private or nursery homes) and thus include various types of background noise. It is thus vital to address such issues when dealing with disordered speech datasets, and consequently, to perform supplementary tuning of the automatic tools or additional preparation of the input data for the automatic tools (e.g., by additional annotation markers).

Another aspect of corpus preparation is the use of file formats that are readable by automatic tools. The annotation formats in ELAN, Annotation Pro and SPPAS are XML-based, while Praat has its own file format. An important common feature of the file formats is the time-stamp information. They can be converted to one another by means of either built-in functions or external converters (e.g., Annotation Pro enables quick data import and export between all of the above tools). The possibility of data conversion makes it possible to use different tools depending on the researcher’s needs. One can develop a corpus using one tool and analyse data with another one (cf. also Ide & Pustejovsky, 2010; Ide & Romary, 2007). An illustration of such a procedure could be the study of timing variability analysis for healthy speakers and speakers with Parkinson’s disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and cerebellar ataxia based on TYPALOC corpus (Bigi et al., 2015). The input for the timing analysis was the multilayer annotation in XRA format (native to the SPPAS tool), among others, including layers with automatically generated syllable-level segmentation and time-aligned transcription. The files were imported to the ANT file format (Annotation Pro native format) and explored using the Annotation Pro+TGA plugin (Klessa & Gibbon, 2014) that allows automatic calculation of syllable-based duration statistics as well as detection and visualization of speech acceleration and deceleration patterns (cf. also Gibbon, 2013). The results indicate that the speakers with PD speak relatively faster and at the same time exhibit stronger syllable time contrasts which entails significant deceleration within interpausal phrase units. On the other hand, the ALS group showed a lowered speaking rate with less deceleration. The results for the cerebellar ataxia group are intermediate between the PD and ALS groups, and do not differ clearly from the healthy group with regard to speaking rate variability. Timing variability analyses usually rely on time-stamps for segment (e.g., speech sound or syllable) boundary positions and annotation labels, all of which are included in the annotation files. Therefore, the above annotation mining results were obtained based on annotations only, without the need to access the original sound recordings.

4 Guidelines for consent and storage

Information about research data management is available on the websites of many universities as well as funded initiatives developed specifically for data archiving and sharing. The amount of information available varies from a succinct explanation to a detailed account supplemented with sample documents, such as sample information sheets and consent forms. The information is usually institution- or country-specific, yet mostly generic for application to various disciplines. In addition, the development of ethical consent and data archiving requirements is continuing. It would be very useful to have corresponding information that is specific for the field of clinical phonetics and linguistics, and speech and language pathology to help researchers better plan their collection, storage, and sharing of research data. Hence, a page of guidelines on consent and data storage was created and added to the DELAD website (https://delad.ruhosting.nl/wordpress/guidelines-consent-storage/).

The webpage includes a few pointers to other useful websites such as that of the UK Data Service (https://ukdataservice.ac.uk/), and the Finnish Social Science data archive (https://www.fsd.tuni.fi/en/services/data-management-guidelines/), as well as the National Coordination Point Research Data Management (https://www.lcrdm.nl/) of the Netherlands; a case scenario (described below) supported by a discussion of key ethics issues that researchers may have to consider if they plan to share pathological speech data of their projects via platforms such as the one facilitated by DELAD; and a set a sample information sheets and consent forms that are related to the fictional research project stated in the case scenario. The main aim of this webpage is to provide researchers a list of issues that they may have to consider at the stage of research project planning. Throughout the webpage, researchers are reminded to consult their local policies and regulations to determine whether any of the issues stated are relevant to their projects. Suggestions from peers and further discussions are welcomed to elaborate the example provided on this webpage.

Below is the case scenario that includes a number of key elements common to many speech and language research projects, with each of those elements elaborated in the succeeding subsections:

A researcher is planning to carry out a research project that investigates articulatory errors in adolescents and young adults with cerebral palsy using both auditory-perceptual and acoustic analyses. The data will also be compared to that of a group of age- and gender-matched typical speakers to examine whether there is any difference in speech characteristics between the two groups of speakers. Before speech data collection, the hearing and visual abilities of the participants will be screened to ensure that all have adequate abilities for taking part in the subsequent speech production tasks. In addition, the participants with cerebral palsy will undertake a language test to document their language ability. The acoustic analysis of speech will be carried out by the research assistants of the project, whereas a group of typical individuals will be recruited as the listeners of the auditory-perceptual analysis of speech. The researcher also plans to have the speech data archived after the completion of this project to allow possible further research using the same set of data (e.g., analysis of voice quality) by other researchers and for education purposes in the future.

4.1 Recruitment of human participants

The research participants in the case scenario include both children and adults as speakers, and another group of adults as listeners. For the speakers, half of those are typical and healthy individuals and the others are those with communication disorders. Informed consent is needed from each human participant (see e.g., Lange et al., 2013). Adults, except those with severe intellectual or language comprehension abilities, can give their own consent. For including children as research participants, both parents’ or caregivers’ consent and children’s assent are required for some countries, while parents’ or caregivers’ consent is sufficient in some places. However, the age threshold that a young person can give their own consent varies between countries. For example, it is 18 years of age in Ireland (Health Service Executive, 2022) but 16 years in the UK (see e.g., NHS Health Research Authority, n.d.). A set of information sheets and consent forms is usually required for each group involved and this is discussed in Sect. 4.5.

4.2 Type of data to be collected

The type of data to be collected in speech and language projects include the data that is related to speech and language production, the participants’ information, and the data from different tests for ensuring the participants fulfil the inclusion criteria. The speech and language production data may include audio recordings of the speakers’ speech, video recordings of how speech is produced, as well as other data obtained using instrumental examination techniques (e.g., endoscopy, videofluoroscopy, ultrasound, MRI). As discussed in Sect. 3, interpretation of these data usually involves data annotation. Depending on the measurements to be made, the data analysis can be based solely on the annotations which may not contain any identifying information of the speakers. The participants’ information may include age, gender, medical information (IQ score, neurological assessment results and diagnosis, medications) that are relevant to the communication disorder investigated in the project. The information will form the demographics of the experimental and control groups. In order to ensure the participants recruited are homogenous in terms of certain parameters, tests such as standardised assessments and/or screenings devised specifically for the projects, are administered to the participants as well. In the case scenario, the information includes the results of hearing and visual ability screens and language test scores. With the GDPR in mind, researchers should only collect the personal information that is necessary for answering the research questions.

4.3 Management of research data

It is useful to make a list of the types of information to be collected and the sources from which the information will be obtained, for example, collection of information from parents or caregivers, and clinic records or medical reports of the participants. In addition, researchers have to consider the method(s) for anonymizing or de-identifying the information. Not only the direct identifying information (or identifiers) need to be removed, but also indirect identifiers (e.g., date of birth) or description of participants’ characteristics, as in combination, they might produce a unique profile, in turn revealing who they are. Alternatively, such identifiers can be replaced by less specific ones, such as an age interval or a region of birth (see also below).

In some cases, multilayer speech and video signal annotations can be used standalone, without the need to access the underlying speech or video recordings. For example, the annotation files themselves are sufficient as a source of information for the purposes of certain lexical or grammatical analyses of language. Other examples are phonotactic studies, analyses of segmental duration or timing variability. However, for the investigation of many other kinds of features, the access to multimodal files is still necessary, along with rich annotations.

For the data related to speech and language production, researchers should think about the format in which the data will be stored, or the types of files that will be created during the project. For example, in this specific case scenario, the speech samples will be saved as audio files and/or video files (in electronic format). The acoustic analysis data and any files generated during the analysis process (e.g., files for annotating the speech signals; spreadsheets for summarizing the measurements or further calculations; data and result files of statistical tests) will probably be in electronic format as well. For auditory-perceptual analysis, the ratings may be in electronic format if they are collected using computer software, or in hard copy if paper response sheets are used. For each of these types of data, the researchers will have to think about where they will be kept during the lifetime of the project.

For researchers who plan to share their research data and relevant anonymized participant information for further research or education purposes, through platforms such as facilitated by DELAD, they should inform the participants of their plan of data sharing in the information sheet and ask for the participants’ consent. Similar to the option of pulling out from participation, researchers are advised to consider giving the participants a period (e.g., 2 weeks after participation) should they eventually decide to withdraw their consent regarding data sharing. This option should be stated clearly in the information sheet as well. In addition, a succinct description of what type or format of the research data and anonymized participant information will be shared and where these materials will be physically archived should be included in the information sheet. The statements about DELAD may take the following form: “DELAD stands for Database Enterprise for Language And speech Disorders (website: http://delad.net/) that aims to provide a channel for researchers to share corpora of speech of individuals with communication disorders with educators and researchers. DELAD has linked up with the Knowledge Centre for Atypical Communication Expertise (website: https://ace.ruhosting.nl/), a K-centre of CLARIN (Common Language Resources and Technology Infrastructure; website: https://www.clarin.eu/) for archiving and sharing the speech corpora through The Language Archive (website: https://archive.mpi.nl/tla/) and/or TalkBank (website: https://talkbank.org).”

Regarding anonymized participant information, researchers will have to decide on the types of information to be archived. For example, the researchers might have obtained the participants’ date of birth on the day of data collection to work out their age; but for archiving, one might decide to keep the record of participants’ age or age interval (e.g., 7;0–7;11) only. Similarly, for test results and scoring sheets, one might decide to archive only the final judgements (e.g., passed the hearing screen) or final scores (e.g., total scores of a language test). For the research data, there are some experimental or assessment tasks that may elicit certain personal information (e.g., asking the participants to talk about their voice problems, or a task to collect voice samples at connected speech level from the participants). It is possible that the personal information mentioned concerns the participants themselves or people whom they know. In such cases, appropriate methods should be used to anonymise the speech data. For example, removing the names mentioned or replacing that speech signal by a beep sound for audio files; and blurring of faces in video recordings. Depending on the speech data collected, restricted access by other researchers might be considered. As stated above, datasets shared via DELAD will be archived with TLA, hence, researchers are advised to check the TLA deposit manual (https://archive.mpi.nl/tla/deposit-manual-tla) for further information regarding the acceptable format of the speech data.

4.4 Data access level and secondary analysis

Researchers who plan to share their data will have to think about the level of access that is appropriate for the datasets. There are a few things to consider; for example, will the users have to register with the data archiving platform in order to access the data? Will the users need to sign a license or data use agreement before they can download the datasets? Will that platform keep a record on who accessed which data set? Again, researchers will have to make sure the information about data access level is stated in the consent form for the participants. CLARIN offers a range of licence options on its website https://www.clarin.eu/content/licenses-and-clarin-categories) and an online wizard to select the most appropriate licence from these (https://www.clarin.eu/content/clarin-license-category-calculator).

Consent from the participants, whether they are speakers or listeners, is needed for future secondary analysis. Researchers will have to think about who might access the data and how the data might be used or analysed again. When asking the participants to give consent for using their data in further research projects, researchers may consider including this as a separate opt-in or ask for permission to contact the participants again regarding secondary analysis in future research projects. For the latter, the researchers will have to keep a record on the date that the contact information was obtained from the participants.

4.5 Sample information sheets and consent forms

As explained above, the research participants in the case scenario include children and adults as the speakers, and another group of adults as the listeners. Hence, four sets of information sheets and consent forms are needed for the: (1) adult speakers, (2) child speakers, (3) parents or caregivers of the child speakers, and the (4) adult listeners. An information sheet usually includes (but is not limited to) the following information and they are demonstrated in the sample information sheets: the aim(s) of the study; the inclusion and/or exclusion criteria regarding participant recruitment; the tasks or activities in which the participants will engage; voluntary participation and the option of withdrawing their participation or their data from being included in the study; the types of data to be collected from each participant; how the data will be handled, and where and for how long the data will be stored; the process for anonymising or de-identifying the data; how the data will be used (e.g., results to be disseminated in research papers and conferences); the detail of the plan of sharing the data set with other researchers; and the plan of secondary analysis. The documents for children include the key information explained in simpler language, whereas those for the adults are written in plain language. Researchers may use these sample information sheets and consent forms as examples when devising their documents for their own research project.

5 Data Protection Impact Assessment for resources on speech disorders

As an additional instrument to help researchers share their data, DELAD developed a case scenario that is specific for CSD for a role-play exercise around Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA). A DPIA is an instrument to inventorise the data protection risks of a project and to minimise these. In the case of CSD, this typically concerns personal data. The role-play activity for learning the DPIA process was designed by Esther Hoorn of the University of Groningen in her capacity as member of the CLARIN Legal and Ethical Issues Committee (CLIC). The objective of the activity is to give students real-world experience conducting a multi-stakeholder (e.g., researcher, ethics know-how, IT expert) assessment. Every student takes on the role of a different stakeholder in the DPIA process and they have to apply knowledge and ideas they have acquired through their lectures or online training in doing the role-play. The activity assists the students in considering the viewpoints of the other participants in the process. The material that forms the basis of the role-play exercise can be accessed via this link: https://sites.google.com/rug.nl/privacy-in-research/role-playing-game.

At the fifth DELAD Workshop that took place online in January 2021, a role-play activity using a case scenario about a PhD research project on voice disorders in people with Parkinson’s disease was included for the participants. As a result of the very positive feedback from the workshop participants about this role-play activity, the DELAD steering group developed a case scenario that is specific for CSD. The group members recorded a video which addresses the basic elements of a DPIA for sharing sensitive patient research data. The goal of this role-play is to show students and researchers working with patient data which stakeholders and key issues to address in a DPIA, and stimulate them to work along similar lines for a DPIA for their own data if they intend to share the data with others.

The setting of the role play is as follows:

Alice, a researcher, has developed an algorithm for voice conversion. This technique can alter the speech signal in a way so that the speakers could not be recognised by the third party. This kind of pseudonymised speech data is potentially useful for research in many other disciplines or research design. The algorithm was developed based on speech samples collected from typical adult speakers of English, German, and Dutch. The next step is to test this algorithm on other languages, age groups and speakers with different types of speech disorders. There is a dataset that comprises speech samples of 60+ Polish-speaking children with speech difficulties associated with hearing impairment. The dataset is available under restricted access conditions. The repository sees it as its responsibility to contact the representatives of data providers for permission.

The video shows a meeting of stakeholders of the Polish dataset, based on a method for a DPIA. They discuss whether and under which conditions the dataset can be made available for the envisaged research purposes in the light of the GDPR. The educational material is provided as:

-

Trailer of the role play

-

Video of the role play

-

Role cards for the play

-

DPIA report created as a result of the role play (with role play introduction)

All materials can be found on the DELAD website on the page for “DPIA role play with video” (https://delad.ruhosting.nl/wordpress/dpia-role-play-with-video/). The development of this roleplay for CSD was reported in a CLARIN Impact Story, “Navigating the GDPR with Innovative Educational Materials” (see https://www.clarin.eu/impact-stories/navigating-gdpr-innovative-educational-materials).

6 Conclusions

DELAD has found a home in the CLARIN network, and the K-Centre for ACE, which provides secure, GDPR-compliant data storage and access for DELAD databases. In this paper, we discussed the ways to increase re-usability of data with specific corpus preparations and possible adjustments in annotations (e.g., labelling, using uncertainty markers and continuous dimensions instead of category based labelling). We reported our efforts to enhance knowledge on specific questions such as guidelines for consent and storage. Although the precise guidelines for consent and storage may vary in different countries, the information regarding recruitment, type of data, management of research data, and data access as well as secondary analysis assists researchers in planning data sharing in a more general fashion. The suggestions on how to create research information sheets and consent forms should be considered in light of possible local guidelines. We encourage students and researchers to simulate real-world experience on how ethical and legal aspects are considered in a research project using the DPIA role play materials developed by DELAD. The activity for data protection assessment and the use of various speech annotation practices expound the key issues that researchers have to consider when sharing and analysing CSD. Sharing these kinds of practices within the community of researchers studying disordered speech will promote enriching, documenting, and sharing their CSD. In summary, DELAD is an active community that provides a platform for interaction between researchers who have an interest in the investigations of disordered speech. Those who are interested to join our efforts can complete an online form on the DELAD website (https://delad.ruhosting.nl/wordpress/join-delad/). Information on future workshops and updates on ongoing development of best practices for sharing CSD will be available on the DELAD website.

Change history

06 November 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10579-023-09701-z

References

Ball, M. J. (2021). Transcribing disordered speech. In M. J. Ball (Ed.), Manual of clinical phonetics (pp. 163–174). Routledge.

Ball, M. J., Baqué, J., Beck, J., Beijer, L., Bernhardt, M., Bressmann, T., Hertrich, I., Howard, S., Klippi, A., Kristoffersen, K. E., Lee, A., Mildner, V., van den Heuvel, H., Müller, N., Lundeborg Hammarström, I., & Samuelsson, C. (2016, June). The DisorderedSPeechBank: A multilingual digital archive of disordered speech [Paper presentation]. The 16th Meeting of the International Clinical Phonetics and Linguistics Association, Halifax, Canada. https://delad.ruhosting.nl/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/DELAD_poster.pdf

Ball, M. J., Howard, S. J., & Miller, K. (2018). Revisions to the extIPA chart. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 48(2), 155–164.

Bigi, B. (2015). SPPAS-multi-lingual approaches to the automatic annotation of speech. The Phonetician, 111, 54–69.

Bigi, B. (2021). SPPAS annotation format: XRA Schema (version 1.5). HAL open science. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03468454/document

Bigi, B., Klessa, K., Georgeton, L., & Meunier, C. (2015). A syllable-based analysis of speech temporal organization: A comparison between speaking styles in dysarthric and healthy populations. In Proceedings of the International Speech Communication Association (INTERSPEECH 2015) (pp. 2977–2981). https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01455314/document

Boersma, P., & Weenink, D. (1992–2021). Praat: Doing phonetics by computer (Version 6.2) [Computer program]. https://www.praat.org

Cowie R., & Douglas-Cowie E. (1996). Automatic statistical analysis of the signal and prosodic signs of emotion in speech. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Spoken Language Processing (ICSLP’96) (Vol. 3, pp. 1989–1992). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSLP.1996.608027

Duckworth, M., Allen, G., Hardcastle, W., & Ball, M. (1990). Extensions to the international phonetic alphabet for the transcription of atypical speech. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 4(4), 273–280. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699209008985489

Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 6(3–4), 169–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699939208411068

Ferré, G. (2012). Functions of three open-palm hand gestures. Multimodal Communication, 1(1), 5–20. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00666025/document

GDPR. (2016). Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). Official Journal of the European Union, 59, 1–88. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1515793631105&uri=CELEX:32016R0679

Gibbon, D. (2013). TGA: A web tool for Time Group Analysis. In D. Hirst & B. Bigi (Eds.), Proceedings of Tools and Resources for the Analysis of Speech Prosody (TRASP) (pp. 66–69). http://wwwhomes.uni-bielefeld.de/gibbon/Dafydd_Gibbon_Publication_PDFs/2013_Gibbon_TGA_TRASP2013-DafyddGibbon-paper-04.pdf

Health Service Executive. (2022). National consent policy. https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/qid/other-quality-improvement-programmes/consent/hse-national-consent-policy.pdf

Ide, N., & Pustejovsky, J. (2010). What does interoperability mean, anyway? Toward an operational definition of interoperability for language technology. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Global Interoperability for Language Resources (ICGL 2010). https://www.cs.vassar.edu/~ide/papers/ICGL10.pdf

Ide, N., & Romary, L. (2007). Towards international standards for language resources. In L. Dybkjær, H. Hemsen, & W. Minker (Eds.), Evaluation of text and speech systems (pp. 263–284). Kluwer. https://hal.inria.fr/hal-00650597

Jarmołowicz-Nowikow, E., & Karpiński, M. (2011). Communicative intentions behind pointing gestures in task-oriented dialogues. In Proceedings of the 2nd Conference on Gesture and Speech in Interaction (GESPIN).

Klessa, K., & Gibbon, D. (2014). Annotation Pro + TGA: automation of speech timing analysis. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’14) (pp. 1499–1505). http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2014/pdf/553_Paper.pdf

Klessa K., Karpiński M., & Wagner A. (2013). Annotation Pro – A new software tool for annotation of linguistic and paralinguistic features. In D. Hirst & B. Bigi (Eds.), Proceedings of Tools and Resources for the Analysis of Speech Prosody (TRASP) (pp. 51–54). http://www2.lpl-aix.fr/~trasp/Proceedings/19897-trasp2013.pdf

Ladefoged, P. (1971). Preliminaries to linguistic phonetics. University of Chicago Press.

Lange, M. M., Rogers, W., & Dodds, S. (2013). Vulnerability in research ethics: A way forward. Bioethics, 27(6), 333–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12032

Lee, A., Bessell, N., van den Heuvel, H., Saalasti, S., Klessa, K., Müller, N., & Ball, M. J. (2022). The latest development of the DELAD project for sharing corpora of speech disorders. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 36(2–3), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699206.2021.1913514

Lenardič, J. (2020, June 11). Tour de CLARIN: Interview with Katarzyna Klessa and Anita Lorenc. CLARIN. https://www.clarin.eu/blog/tour-de-clarin-interview-katarzyna-klessa-and-anita-lorenc

Lorenc, A. (2016). Transkrypcja wymowy w normie i w przypadkach jej zaburzeń. Próba ujednolicenia i obiektywizacji [Transcription of pronunciation in speech norm and in cases of speech disorders. An approach to standardize and objectify]. In B. Kamińska & S. Milewski (Eds.), Logopedia artystyczna (pp. 107–143). Harmonia Universalis.

MacWhinney, B., Fromm, D., Holland, A., & Forbes, M. (2013). AphasiaBank: Data and methods. In N. Müller & M. J. Ball (Eds.), Research methods in clinical linguistics and phonetics: A practical guide (pp. 355–380). Wiley-Blackwell.

NHS Health Research Authority. (n.d.). Principles of consent: Children and young people (English, Wales and Northern Ireland). http://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/consent/principles-children-EngWalesNI.html

Nodari, R., Calamai, S., & van den Heuvel, H. (2021). Less is more when FAIR. The minimum level of description in pathological oral and written data. In M. Monachini & M. Eskevich (Eds.), CLARIN annual conference proceedings 2021 (pp. 166–171). https://office.clarin.eu/v/CE-2021-1923-CLARIN2021_ConferenceProceedings.pdf

Plutchik, R. (1982). A psychoevolutionary theory of emotions. Social Science Information, 21(4–5), 529–553.

Smith, C. A., & Ellsworth, P. C. (1985). Patterns of cognitive appraisal in emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(4), 813–838.

van den Heuvel, H., Ball, M. J., Bessell, N., Lee, A., Müller, N., & Saalasti, S. (2018, October). Update to the DELAD project [Paper presentation]. The 17th Meeting of the International Clinical Phonetics and Linguistics Association, St. Julian’s, Malta.

van den Heuvel, H., Oostdijk, N., Rowland, C., & Trilsbeek, P. (2020). The CLARIN Knowledge Centre for Atypical Communication Expertise. In Proceedings of the 12th international conference on language resources and evaluation (LREC 2020) (pp. 3312–3316). https://aclanthology.org/2020.lrec-1.405.pdf

Wittenburg, P., Brugman, H., Russel, A., Klassmann, A., & Sloetjes, H. (2006). ELAN: A professional framework for multimodality research. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’06) (pp. 1556–1559). http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2006/pdf/153_pdf.pdf

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professors Martin Ball and Nicole Müller who started DELAD and all participants of previous workshops.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium. The work reported in this paper was supported by funding from the Riksbankens Jubileumsfond [Bank of Sweden Tercentenary Foundation] and CLARIN ERIC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and K.K. prepared Fig. 1. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval by a research ethics committee is not applicable as the present manuscript does not involve any research experiment carried out on human or animal subjects.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: In Section 3.2, the second paragraph, the sentences describing the figure 1 has been corrected.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, A., Bessell, N., van den Heuvel, H. et al. The DELAD initiative for sharing language resources on speech disorders. Lang Resources & Evaluation (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10579-023-09655-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10579-023-09655-2