Abstract

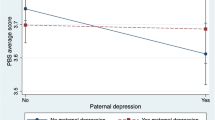

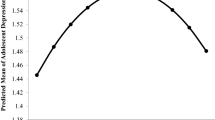

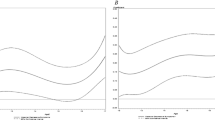

Longitudinal evidence demonstrating the association between parental absence and depressive symptoms in adolescence is limited. The present study aimed to explore this relationship in a Chinese national representative sample. This research was based on the China Family Panel Studies and included 1481 subjects. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the self-reported Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression questionnaire. A multiple logistic regression model with a generalized estimating equation was used to test the association between parental absence and adolescent depressive symptoms. In the baseline year, 2012, 29.03% and 43.75% of adolescents had maternal and paternal absence, respectively. The prevalence of depressive symptoms increased from 23.23% to 28.12% in subsequent years. After controlling for covariates, maternal absence was positively associated with depressive symptoms (odds ratio 1.69, 95% confidence interval 1.06–2.68). Maternal absence led to depression in adolescents. It may be beneficial for adolescents with depression to spend more time with their mothers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://opendata.pku.edu.cn

Code Availability

The code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (2018) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392:1789–1858. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7

Smith K (2014) Mental health: a world of depression. Nature 515:181. https://doi.org/10.1038/515180a

Zisook S, Lesser I, Stewart JW, Wisniewski SR, Balasubramani GK, Fava M et al (2007) Effect of age at onset on the course of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 164:1539–1546. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101757

Blazer DG, Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz MS (1994) The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry 151:979–986. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.151.7.979

World Health Organization. Depression [EB/OL]. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression.

Hesketh T, Ding QJ (2005) Anxiety and depression in adolescents in urban and rural China. Psychol Rep 96:435–444. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.96.2.435-444

Zhou M, Zhang G, Rozelle S, Kenny K et al (2018) Depressive symptoms of Chinese children: prevalence and correlated factors among subgroups. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020283

Antman FM (2011) International migration and gender discrimination among children left behind. Am Econ Rev 101:645–649. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.3.645

Jordan LP, Graham E (2012) Resilience and well-being among children of migrant parents in South-East Asia. Child Dev 83:1672–1688. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01810.x

Wang F, Lu J, Lin L, Zhou X (2019) Mental health and risk behaviors of children in rural China with different patterns of parental migration: a cross-sectional study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 13:39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-019-0298-8

Gibson BS, Gondoli DM, Johnson AC, Steeger CM et al (2011) Component analysis of verbal versus spatial working memory training in adolescents with ADHD: a randomized, controlled trial. Child Neuropsychol 17:546–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2010.551186

Zhao C, Wang F, Li L, Zhou X et al (2017) Long-term impacts of parental migration on Chinese children’s psychosocial well-being: mitigating and exacerbating factors. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 52:669–677. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1386-9

He B, Fan J, Liu N, Li H et al (2012) Depression risk of “left-behind children” in rural China. Psychiatry Res 200:306–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.04.001

Wang F, Lin L, Xu M, Li L et al (2019) Mental health among left-behind children in rural China in relation to parent-child communication. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16101855

Zhang X, Li M, Guo L, Zhu Y (2019) Mental health and its influencing factors among left-behind children in South China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 19:1725. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-8066-5

Tao XW, Guan HY, Zhao YR, Fan ZY (2014) Mental health among left-behind preschool-aged children: preliminary survey of its status and associated risk factors in rural China. J Int Med Res 42:120–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060513503922

Lu Y (2012) Household migration, social support, and psychosocial health: the perspective from migrant-sending areas. Soc Sci Med 74:135–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.020

Kharel M, Akira S, Kiriya J, Ong KIC et al (2021) Parental migration and psychological well-being of left-behind adolescents in Western Nepal. PLoS ONE 16:e0245873. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245873

Bufferd SJ, Dougherty LR, Carlson GA, Rose S et al (2012) Psychiatric disorders in preschoolers: continuity from ages 3 to 6. Am J Psychiatry 169:1157–1164. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12020268

Merikangas KR, Nakamura EF, Kessler RC (2009) Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 11:7–20. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.1/krmerikangas

Johnson D, Dupuis G, Piche J, Clayborne Z et al (2018) Adult mental health outcomes of adolescent depression: a systematic review. Depress Anxiety 35:700–716. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22777

Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN, Seeley JR, Rohde P (1994) Major depression in community adolescents: age at onset, episode duration, and time to recurrence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 33:809–818. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199407000-00006

Xie Y, Hu J (2014) An introduction to the China family panel studies (CFPS). Chin Sociol Rev 47:3–29. https://doi.org/10.2753/CSA2162-0555470101.2014.11082908

Xie Y, Lu P (2015) The sampling design of the China family panel studies (CFPS). Chin J Sociol 1:471–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057150x15614535

Radloff LS (1977) The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1:385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

Radloff LS (1991) The use of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale in adolescents and young adults. J Youth Adolesc 20:149–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01537606

Institute of Social Science Survey. China Family Panel Studies 2016 database introduction and data cleansing report. Available at: http://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/docs/20201201085335172101.pdf

Wen M, Su S, Li X, Lin D (2015) Positive youth development in rural China: the role of parental migration. Soc Sci Med 132:261–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.051

Peng X (2011) China’s demographic history and future challenges. Science 333:581–587. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1209396

Chen X, Wang L, Wang Z (2009) Shyness-sensitivity and social, school, and psychological adjustment in rural migrant and urban children in china. Child Dev 80:1499–1513. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01347.x

Zhou C, Lv Q, Yang N, Wang F (2021) Left-behind children, parent-child communication and psychological resilience: a structural equation modeling analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105123

Li M, Ren Y, Sun H (2020) Social anxiety status of left-behind children in rural areas of Hunan province and its relationship with loneliness. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 51:1016–1024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-020-01045-x

Lu J, Lin L, Roy B, Riley C et al (2020) The impacts of parent-child communication on left-behind children’s mental health and suicidal ideation: a cross sectional study in Anhui. Child Youth Serv Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104785

Liu Z, Li X, Ge X (2009) Left too early: the effects of age at separation from parents on Chinese rural children’s symptoms of anxiety and depression. Am J Public Health 99:2049–2054. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2008.150474

Mazzucato V, Cebotari V, Veale A, White A et al (2015) International parental migration and the psychological well-being of children in Ghana, Nigeria, and Angola. Soc Sci Med 132:215–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.058

Bhargava A, Tan X (2018) A longitudinal analysis of internal migration, divorce and well-being in China. J Biosoc Sci 50:706–722. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021932017000499

Adhikari R, Jampaklay A, Chamratrithirong A, Richter K et al (2014) The impact of parental migration on the mental health of children left behind. J Immigr Minor Health 16:781–789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-013-9809-5

Fellmeth G, Rose-Clarke K, Zhao C, Busert LK et al (2018) Health impacts of parental migration on left-behind children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 392:2567–2582. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32558-3

Zhao C, Egger HL, Stein CR, McGregor KA (2018) Separation and reunification: mental health of Chinese children affected by parental migration. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-0313

Pottinger AM (2005) Children’s experience of loss by parental migration in inner-city Jamaica. Am J Orthopsychiatry 75:485–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.75.4.485

Senaratne BC, Perera H, Fonseka P (2011) Mental health status and risk factors for mental health problems in left-behind children of women migrant workers in Sri Lanka. Ceylon Med J 56:153–158. https://doi.org/10.4038/cmj.v56i4.3893

Zhou M, Sun X, Huang L, Zhang G et al (2018) Parental migration and left-behind children’s depressive symptoms: estimation based on a nationally-representative panel dataset. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061069

Wen M, Lin D (2012) Child development in rural China: children left behind by their migrant parents and children of nonmigrant families. Child Dev 83:120–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01698.x

Zhou C, Sylvia S, Zhang L, Luo R et al (2015) China’s left-behind children: impact of parental migration on health, nutrition, and educational outcomes. Health Aff 34:1964–1671. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0150

Wang L, Mesman J (2015) Child development in the face of rural-to-urban migration in china: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci 10:813–831. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615600145

Attar-Schwartz S, Tan JP, Buchanan A, Flouri E et al (2009) Grandparenting and adolescent adjustment in two-parent biological, lone-parent, and step-families. J Fam Psychol 23:67–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014383

Government of China. Announcement on the care and education for rural school aged left-behind children by Ministry of Education and four other agencies. 2013. Available at: http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2013-01/10/content_2309058.htm.

Twisk JWR (2013) Applied longitudinal data analysis for epidemiology: a practical guide. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kessler RC, Walters EE (1998) Epidemiology of DSM-III-R major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the national comorbidity survey. Depress Anxiety 7:3–14

Yang HJ, Soong WT, Kuo PH, Chang HL et al (2004) Using the CES-D in a two-phase survey for depressive disorders among nonreferred adolescents in Taipei: a stratum-specific likelihood ratio analysis. J Affect Disord 82:419–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2004.04.008

Byrne BM, Stewart SM, Lee PWH (2004) Validating the beck depression inventory-II for Hong Kong community adolescents. Int J Test 4:199–216. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327574ijt0403_1

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank China Family Panel Studies Office and Institute Social Science Survey at Peking University. Thanks to Project 985 of Peking University for funding the implementation of the CFPS project.

Funding

This work was supported by the research project of Ningxia Medical University (No. XT2019009) and the key research and development project of Ningxia Autonomous Region (No. 2021BEG02030).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZY: validation, formal analysis, writing—original draft; YD: validation, formal analysis; NH: validation, writing—original draft; YZ: project administration, validation; JL: validation, supervision, writing and revision conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethics Approval

The CFPS is a nationally representative, biennial household survey that has been performed since 2010, organized by the Institute of Social Science Survey, Peking University. The Peking University Biomedical Ethics Review Committee provided ethical approval for the survey (Approval number: IRB00001052-14010).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, Z., Du, Y., Hu, N. et al. Association Between Parental Absence and Depressive Symptoms in Adolescence: Evidence From a National Household Longitudinal Survey. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 55, 405–414 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-022-01415-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-022-01415-7