Abstract

Purpose

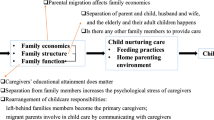

Prolonged separation from migrant parents raises concerns for the well-being of 60 million left behind children (LBC) in rural China. This study aimed to investigate the impact of current and previous parental migration on child psychosocial well-being, with a focus on emotional and behavioral outcomes, while considering factors in family care and support.

Methods

Children were recruited from schools in migrant-sending rural areas in Zhejiang and Guizhou provinces by random stratified sampling. A self-administered questionnaire measured children’s psychosocial well-being, demographics, household characteristics, and social support. Multiple linear regression models examined the effects of parental migration and other factors on psychosocial difficulties.

Results

Data from 1930 current, 907 previous, and 701 never LBC were included (mean age 12.4, SD 2.1). Adjusted models showed both previous and current parental migration was associated with significantly higher overall psychosocial difficulties, involving aspects of emotion, conduct, peer relationships, hyperactivity, and pro-social behaviors. Parental divorce and lack of available support demonstrated a strong association with greater total difficulties. While children in Guizhou had much worse psychosocial outcomes than those in Zhejiang, adjusted subgroup analysis showed similar magnitude of between-province disparities regardless of parental migration status. However, having divorced parents and lack of support were greater psychosocial risk factors for current and previous-LBC than for never LBC.

Conclusions

Parental migration has an independent, long-lasting adverse effect on children. Psychosocial well-being of LBC depends more on the relationship bonds between nuclear family members and the availability of support, rather than socioeconomic status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Increasing migrant flows in many parts of the world are leading to prolonged separation of family members on an unprecedented scale. The number of these so-called “left-behind children” (LBC) is high in many low- and middle-income countries [1, 2]. Historically migration has more often involved young people prior to having families. However, patterns have now changed in many parts of the world as the effects of globalization, ease of movement, and the economic incentives have encouraged and facilitated huge migrant flows. Much of this migration occurs from rural to urban areas within countries for work, often on a temporary basis. China is a typical case where massive rural–urban migration has resulted in 61 million children being left behind in rural areas, accounting for 38% of rural children and 22% of total child population in China [3].

For parents, the decision to migrate involves a trade-off: parents working away may contribute to increased family income and better education opportunities for children, yet lack of parental monitoring, supervision, and support may result in a range of psychosocial and developmental risks [4]. Child psychology and family study researchers have delineated frameworks of child psychopathology in relation to prolonged absence of parents or caregivers, especially within the ambit of attachment theory [5,6,7]. Factors that contribute to attachment relationships include the presence of the caregiver, duration and quality of care, and emotional investment [6]. During long periods of separation, older children may develop negative emotions and dysfunctional thoughts similar to young children’s reactions to physical separation [7].

Concerns about the impacts of being left behind by migrant parents have also led to a growing body of empirical research in child psychology. Parental migration is found to be associated with loneliness [8,9,10], low self-esteem [11], depressive and anxiety symptoms [11,12,13,14], risk behaviors [15], poor school performance and early dropout [15,16,17]. Studies have reported that migration type (father-only, mother-only, or both-parent migration) and care arrangements [18,19,20], as well as child age [21, 22] and sex [15, 23] were important correlates of LBC’s mental health outcomes. However, most of the literature on LBC’s psychological well-being does not provide in-depth exploration of household characteristics and dynamic family relationships. These factors, such as parental divorce and family and social support, may complicate the effects of prolonged separation from parents. Analyses on how the parent–child relationship is experienced within the constraints of physical separation should take into account the dynamism and complexity of the family ties [24]. Across migrant-sending communities in many countries, managing the impact of migration on the vulnerable left-behind family members has become a major challenge, from economic, social, family, and individual perspectives [25].

Separation and reunion in migrant families may also take various patterns [26]. In China, since the vast majority of migration flows are within the country, it is not uncommon that migrant parents return home after living apart from their child for an extended period. There has been very limited research into the effects on children after the return of parents [17, 21]. Changes in China’s labor market with declines in the manufacturing sector and the shift of companies to rural areas have meant that more parents are returning after prolonged periods away from home [27].

The overall aims of this study are to investigate (1) the impact of parental migration on the psychosocial well-being of children who are currently left behind, in comparison with those who were previously left behind, (2) how child well-being factors within the child’s family and social environments, such as care provision, psychosocial support, and socioeconomic status, may affect the impact of parental migration, and (3) whether the effects of key psychosocial risk factors are greater in left-behind children than never left-behind children.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from migrant-sending rural areas in Zhejiang and Guizhou Provinces, China. Three counties in western Zhejiang (Kaihua, Jiande, and Jiangshan) and two counties in southeast Guizhou Province (Guiding and Longli) were included in the study. Zhejiang is a wealthy coastal province, but its western mountainous area is relatively underdeveloped; Guizhou is one of the poorest provinces in China, although the two counties included in this study rank at medium level in GDP across the province.

Questionnaires were obtained from 3596 children. Nine children who did not complete the SDQ section, and eight children with one or both parents deceased were excluded. Another 41 (1.1%) children failed to report parental migration status. A total of 3538 participants were included in the analysis, comprising 1930 current-LBC, 907 previous-LBC, and 701 never-LBC.

Mean age of the sample was 12.4 (SD 2.1) with previous-LBC slightly older (mean 12.5, SD 2.1) than the other two groups. Overall, there were more girls (52.5%) than boys (47.5%) and this did not differ across the three groups. In our sample, 61.8% children were recruited in Guizhou and 31.2% in Zhejiang, and a higher proportion of children in Guizhou (65.6%) were ever left-behind.

Procedure

Officials at the local governments were interviewed to understand the socioeconomic contexts and identify communities with high levels of out-migration. For inclusion in the study, twenty migrant-sending townships were selected in Zhejiang, and ten were selected in Guizhou. In Zhejiang, to make the sample more comparable to Guizhou, two villages at lower economic development levels in each township were further chosen as an inclusion criterion. In both provinces, two random schools in each selected township were included in the study, and all students present in these schools at the time of survey, from Year 4 to Year 9 (aged 9–17), were selected; and then, in Zhejiang, only students from the selected poorer villages were included in the final sample.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committees of University College London and Zhejiang University. Participants were guaranteed the anonymity and confidentiality of their responses in the questionnaire. Before the survey, both the eligible student and one of their parents or custodial caregivers (usually a literate grandparents) were provided with an informed consent form enclosing a detailed description of this study. If consent was given on both forms, the child was asked to complete a self-administered questionnaire in their classroom, without the presence of any teachers or school administrators. Participants were told that there was no compulsion to complete the questionnaire, even after consent was obtained.

Measures

Child psychosocial well-being was measured with the self-report version of Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [28]. The SDQ comprises 25 items of psychosocial well-being in five dimensions, including emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and pro-social behaviors. Each item was scored from 0 to 2. Each dimension was measured by the summed score of its five items as a subscale. A total difficulties score, ranging from 0 to 40, was derived as the sum of four subscales (excluding pro-social subscale), with higher scores indicating greater difficulties. The SDQ has proven its reliability and validity across different cultures and settings, and has been validated in Chinese population [29].

Parental migration status was determined according to the two questions “has your father (and mother) taken a job away from your hometown and been absent for over six months?” The options were “yes, currently absent”, “yes, previously absent”, and “no, never”. If one or both parents were currently absent, the child was defined as a “current-LBC”; if not, and if one or both parents were previously absent, the child was defined as “previous-LBC”; and if neither parent was ever away, the child was “never-LBC”.

Household characteristics, including economic status, parents’ marriage status, primary caregiver, and siblings, were assessed. Economic status was measured by the number of household appliances, including air conditioner, refrigerator, washing machine, television, and computer. The variable was then coded as poor (zero to one item), fair (two to three items), and wealthy (four to five items). The primary caregiver of children was identified based on two consecutive questions, “Who are you currently living with?” and, “Among them, who takes care of you the most?” Caregivers were grouped into four categories: grandparents, father, mother, and others (including relatives, friends, siblings, and no caregiver).

Social support was measured by a scale of six items adapted from the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support [30]. We focused on the aspects that better apply to rural children in China. The questions asked were: whether or not there is someone who the child could turn to help (1) for difficulties in studying, (2) for personal problems, (3) if the child was teased or bullied, (4) if they were feeling sad or depressed, (5) for guidance in dealing with issues when things go wrong, (6) to share happiness with. Children who scored 6, i.e., answered “yes” in all six items, were categorized as high social support. Children who scored 3–5 were categorized as medium, and 0–2 as low social support.

School performance was measured by the question, “In general, what is your academic performance level in your class?” The options were “top, upper-middle, middle, lower-middle, low”, coded from 1 (low) to 5 (top). As in most of China, students are informed of their ranking in the class for major tests, so all children are able to answer this question without difficulty.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square test and analyses of variance were conducted to compare sample characteristics, across three groups of children with different parental migration status. Multiple linear regression models were applied to examine the associations between the psychosocial outcomes and the parental migration status. The initial model included child demographics (age, gender, and province). The model was further adjusted for household characteristics, including economic status, caregiver and sibling, and parents’ marriage status, and two other covariates, social support and school performance. For covariates that remained significant (i.e., p ≤ 0.05), their interactions with migration status were tested, within the adjusted model. Then, the adjusted cell means of total difficulties score were estimated, treating each level of the interaction term as balanced (equal group size), and compared pairwise.

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of children by their parental migration status.

Nearly, two-thirds of current-LBC were primarily cared by grandparents, whereas respective proportions for previous-LBC and never-LBC were 28 and 18%. Parents who had migrated were more likely to be divorced. Current-LBC’s parents were about three times, and previous-LBC’s parents two times more likely than never-LBC’s parents to be divorced. Approximately one-fifth of the children were only children, across the three groups. Fifty percent of never-LBC reported that they were from wealthier households, compared with 30% from the two left-behind groups. In fact, currently-LBC were significantly poorer than never-LBC in both Zhejiang and Guizhou provinces (data not shown). Current-LBC also had lower social support (p < 0.001) and school performance (p < 0.001) compared to never-LBC.

Table 1 also shows the observed differences in mean total difficulties and subscale scores from SDQ, between the three groups of children. Both current-LBC and previous-LBC had higher mean scores of total psychosocial difficulties, as well as higher mean subscale scores of emotional symptoms, peer relationship problems, and hyperactivity, as compared to never-LBC. No differences were identified between the previous-LBC and current-LBC in total or subscale scores according to post hoc tests.

Multiple regression results demonstrated that parental migration, both previous and current, was associated with significantly higher scores in psychosocial difficulties (Table 2). Compared to never-LBC, increases in total difficulties score in current-LBC remained significant (B = 0.57, p = 0.017), after adjusting for household characteristics, social support, and school performance. The strong impact of previous parental migration changed little from the baseline model (B = 0.81, p = 0.001) to the adjusted model (B = 0.75, p = 0.003). Boys appeared to be marginally more vulnerable but only in the baseline model (B = 0.67, p = 0.051). Children in Guizhou had markedly higher psychosocial difficulties than those in Zhejiang (B = 0.92, p < 0.001). Age, household wealth, primary caregiver, and presence of siblings did not affect the psychosocial outcome. Parental divorce showed a strong association with higher total difficulties after adjusting all covariates (B = 1.00, P < 0.001). Both social support and school performances showed negative associations with total difficulties score; greater effects were indicated for each level decrease in social support and school performance. In addition, another adjusted model (not shown), which only included current LBC, indicated that child age at migrant parents’ initial departure as a continuous variable was strongly linked with worse well-being (B = −0.11, p = 0.001).

Table 3 presents the regression results of SDQ subscale scores that showed significant between-group differences in Table 1. After adjusting for all covariates, both current and previous absence of parents were still linked to emotional symptoms, whereas previous-LBC, rather than current-LBC, seemed more disadvantaged in terms of peer relationship, as compared to never-LBC. The demographic variables showed distinct patterns of associations with different subscale outcomes. Girls were much more likely to have emotional difficulties, whereas boys were more susceptible to peer relationship problems. Older children tended to have less peer relationship problems, but were more hyperactive, compared to younger children. Between the two provinces, only hyperactivity score did not differ between children from the two provinces. Although household wealth was negatively associated with peer relationship difficulties, children from richer families are more likely to have hyperactivity problems.

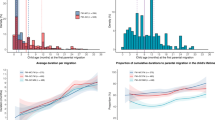

No significant interaction effects of parental migration and key covariates on psychosocial difficulties were found (data not shown). The magnitudes of the impact from parental migration on psychosocial difficulties were similar for Zhejiang and Guizhou (Fig. 1), despite the considerable child well-being gaps between the two provinces. However, the impacts of parents’ divorce and lower social support appeared to be greater in the two left-behind groups than the never left-behind group when comparing adjusted total difficulties scores between the divorced and undivorced and between low and high support groups, within each type of parental migration status (Table 4; Fig. 1).

Discussion

Based on a sample selected from two Chinese provinces with widely differing socioeconomic development levels, our findings indicate that parental migration is independently associated with poor psychosocial well-being in children, especially emotional symptoms, peer relationship problems, and hyperactivity. The questionnaire survey achieved a high response rate, and collected detailed information about current and previous experiences of being left behind, as well as a range of child well-being correlates that allowed us to explore the characteristics of the child’s family and social environments.

Importantly, our results suggest that previous experience of prolonged separation from migrant parents had similar negative impacts on child well-being to the current absence of parents, after accounting for other factors. Adverse experiences related to parental absence in early childhood, such as disruption of parent–child communication and attachment relationship, have long-term negative psychological impacts [7]. The return of migrant parents is unlikely to reverse the complex consequences of their prolonged absence in the child’s life. Their return might even create new challenges in the child’s life due to the change of primary caregiver [31, 32]. However, further investigations are needed to elaborate the risks faced specifically by previous-LBC.

While children in Guizhou fared much worse than those in Zhejiang, our results demonstrated consistent impacts of parental migration on children across the two provinces. Household wealth did not correlate with children’s overall psychosocial outcome. These results suggest that better socioeconomic situation does not mitigate against the adverse psychological experiences caused by parental migration. In the poor rural areas, non-material support and care for left-behind children is probably as important for their well-being as the economic resources from remittances. In fact, wealthier migrant parents especially those who have obtained urban citizenship are more likely to take their children to the cities [33]. In recent years, there has been a marked increase of migrant children living in urban China, whereas the number of LBC remained largely stable in rural areas [34]. According to our findings, LBC also live in poorer families than other rural children. In other words, many children at risk of economic deprivation are separated from parents, and become susceptible to additional risks of psychosocial disadvantages.

Strong negative influences of parents’ divorce suggest the importance of supportive family dynamics in children’s mental health [35]. Parents’ divorce weakens the nuclear family bonds and diminished availability of the family as a supportive structure for the child [36]. Meanwhile, the composition of left-behind families did not seem to be an important factor; even when parents are at home, many children still see grandparents as primary carers. It is the availability of support, from either family or social environments, that plays an essential role in child well-being.

A crucial finding of this study is that the impacts of parental divorce and social support may be greater on left-behind children than never left-behind children. As China’s crude divorce rate has doubled during the past decade [37], with migration as a possible contributor, the consequences of parental divorce in LBC are particularly concerning. In addition to the disrupted parent–child relationship due to migration, parental divorce may cause further damage to the family dynamics for providing adequate care, and lead to extra adverse effects on children’s well-being. Lack of family and social support may result in huge challenges for the psychosocial development of children who are already deprived of parental care. Hence, children who are at these additional risks, besides parental migration, are likely to be particularly vulnerable psychologically. Targeted socioemotional support for these children should be prioritized in the migrant-sending communities.

Poor school performance is also strongly associated with children’s total difficulties. In rural China, as in many societies, education is the key vehicle for social mobility and prosperity [38], particularly for rural children who are generally disadvantaged in educational and career opportunities. Consequently, educational achievement is usually a top concern of the child and the entire family, and poorer school performance may increase child’s psychological stress. Lack of parental guidance and supervision in study is likely to worsen such situation.

Our results also showed interesting demographic influences. It is noteworthy that associations of age, sex, and wealth level with psychosocial outcomes differed across multiple dimensions and some even in opposite directions. Future studies should explore the specific mechanisms of these correlations, and develop pertinent care strategies for children across sociodemographic groups.

This study has the following limitations. First, as a cross-sectional study, causal pathways cannot be delineated, for instance, between the migration status and child well-being, and therefore, the findings should be considered exploratory. Second, due to practical constraints in recruiting migrants and lack of literacy in some grandparents, we were unable to collect data from parents and caregivers; thus, all the data are from child self-report, without triangulation of responses from other family members. Third, educational levels of parents and caregivers, and specific indicators of quality of care and relationships, such as the frequency and quality of communication, were not assessed in this study.

Despite the limitations, our study strongly suggests that left-behind children have markedly higher psychosocial difficulties, independent of family circumstances, support, and school performance. In particular, our study points out the lasting negative impact of left-behind experiences, which are often neglected in academic studies, policies, and interventions. Our findings inform the research on LBC globally, by providing a better understanding of the care environment and family structure in the absence of migrant parents. Future studies should more detail on the cyclic pattern of migration, such as duration of separation and reunion and frequency of home visits, and adopt a longitudinal design to provide more in-depth evidence on the long-term impact of parental migration. Specific indicators of relationship dynamics and childcare quality in various family and caregiving contexts should also be further examined.

Other major factors that are associated with psychosocial well-being, especially social support and school performance, require further efforts from local communities to safeguard and promote LBC’s well-being. Current child well-being interventions in China are predominantly focused on economic or material support [39], whereas extreme events such as fatal injuries, rape, and suicide of unsupervised rural children have been frequently reported, including a number of tragedies in Guizhou [40]. Our results can help to inform future strategies and programs in addressing the psychological and developmental risks particularly faced by LBC. In fact, in our study sites, “Children’s Clubs” programs (or others with similar names) have been implemented by the local government and community leadership. In their local village, children can play and study together after school in these clubs, under the care and supervision of volunteers such as local retirees and schoolteachers, as well as university students from nearby cities. These programs offer supervision and support for the LBC using integrated resources at community level, and organize various activities that may benefit child development through social interactions. Future research should explore the effectiveness of similar practices to safeguard child well-being in migrant-sending communities.

References

Bryant J (2005) Children of international migrants in Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines: a review of evidence and policies. Innocenti Working Paper 2005-05. UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Florence

Nobles J (2013) Migration and father absence: shifting family structure in Mexico. Demography 50(4):1303–1314

All-China Women’s Federation (2013). National survey report on the situation of left-behind children and migrant children in China, Beijing

Ding G, Bao Y (2014) Editorial perspective: assessing developmental risk in cultural context: the case of ‘left behind’ children in rural China. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 55(4):411–412

Bowlby J (1969) Attachment and loss: vol 1. Attachment. Basic Books, New York

Cassidy J (2008) The nature of the child’s ties. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR (eds) Handbook of attachment: theory, research, and clinical applications, 2nd edn. Guilford, New York, pp 3–23

Kobak R, Madsen S (2008) Disruptions in attachment bonds: implications for theory, research, and clinical intervention. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR (eds) Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications, 2nd edn. Guilford, New York, pp 23–48

Liu LJ, Sun X, Zhang CL, Wang Y, Guo Q (2010) A survey in rural China of parent-absence through migrant working: the impact on their children’s self-concept and loneliness. BMC Public Health 10(1):32

Asis MM (2006) Living with migration: experiences of left-behind children in the Philippines. Asian Popul Stud 2(1):45–67

Smeekens C, Stroebe MS, Abakoumkin G (2012) The impact of migratory separation from parents on the health of adolescents in the Philippines. Soc Sci Med 75(12):2250–2257

Luo J, Wang LG, Gao WB (2012) The influence of the absence of fathers and the timing of separation on anxiety and self-esteem of adolescents: a cross-sectional survey. Child Care Health Dev 38(5):723–731

He B, Fan J, Liu N, Li H, Wang Y, Williams J, Wong K (2012) Depression risk of ‘left-behind children’in rural China. Psychiatry Res 200(2):306–312

Wang L, Feng Z, Yang G, Yang Y, Dai Q, Hu C, Liu K, Guang Y, Zhang R, Xia F, Zhao M (2015) The epidemiological characteristics of depressive symptoms in the left-behind children and adolescents of Chongqing in China. J Affect Disord 177:36–41

Zhao X, Chen J, Chen MC, Lv XL, Jiang YH, Sun YH (2014) Left-behind children in rural China experience higher levels of anxiety and poorer living conditions. Acta Paediatr 103(6):665–670

Gao Y, Li LP, Kim JH, Congdon N, Lau J, Griffiths S (2010) The impact of parental migration on health status and health behaviours among left behind adolescent school children in China. BMC Public Health 10(1):56

Dreby J (2007) Children and power in Mexican transnational families. J Marriage and Fam 69(4):1050–1064

Wu Q, Lu D, Kang M (2015) Social capital and the mental health of children in rural China with different experiences of parental migration. Soc Sci Med 132:270–277

Zhao KF, Su H, He L, Wu JL, Chen MC, Ye DQ (2009) Self-concept and mental health status of “stay-at-home” children in rural China. Acta Paediatr 98(9):1483–1486

Graham E, Jordan LP (2011) Migrant parents and the psychological well-being of left-behind children in Southeast Asia. J Marriage and Fam 73(4):763–787

Jia Z, Tian W (2010) Loneliness of left-behind children: a cross-sectional survey in a sample of rural China. Child Care Health Dev 36(6):812–817

Fan F, Su L, Gill MK, Birmaher B (2010) Emotional and behavioral problems of Chinese left-behind children: a preliminary study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 45(6):655–664

Liu Z, Li X, Ge X (2009) Left too early: the effects of age at separation from parents on Chinese rural children’s symptoms of anxiety and depression. Am J Public Health 99(11):2049–2054

Hu H, Lu S, Huang CC (2014) The psychological and behavioral outcomes of migrant and left-behind children in China. Child Youth Serv Rev 46:1–10

Carling J, Menjívar C, Schmalzbauer L (2012) Central themes in the study of transnational parenthood. J Ethnic and Migr Stud 38(2):191–217

Valtolina GG, Colombo C (2012) Psychological well-being, family relations, and developmental issues of children left behind. Psychol Rep 111(3):905–928

Schapiro NA, Kools SM, Weiss SJ, Brindis CD (2013) Separation and reunification: the experiences of adolescents living in transnational families. Current Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 43(3):48–68

Dollar D (2014) Sino Shift China’s rebalancing opens new opportunities for developing Asia. Financ Dev 51(2):10–13

Goodman R (1997) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38(5):581–586

Kou J, Du Y, Xia L (2007) Formulation of children strengths and difficulties questionnaire (the edition for students) for Shanghai norm. China J Health Psycholoy 15:35–38

Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK (1988) The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess 52(1):30–41

Pottinger AM (2005) Children’s experience of loss by parental migration in inner-city Jamaica. Am J Orthopsychiatry 75(4):485–496

Senaratne BCV, Perera H, Fonseka P (2011) Mental health status and risk factors for mental health problems in left-behind children of women migrant workers in Sri Lanka. Ceylon Med J 56(4):153–158

Smart A, Smart J (2001) Local citizenship: welfare reform urban/rural status, and exclusion in China. Environ Plan A 33(10):1853–1869

UNICEF (2014) What census data can tell us about children in China-Facts and Figures 2013. UNICEF China, Beijing

Strohschein L (2005) Parental divorce and child mental health trajectories. J Marriage Fam 67(5):1286–1300

Wallerstein JS, Kelly JB (2008) Surviving the breakup: how children and parents cope with divorce. Basic Books, New York

Davis DS (2014) Demographic challenges for a rising China. Daedalus 143(2):26–38

Bian Y (2002) Chinese social stratification and social mobility. Ann Rev Sociol, 91–116

UNICEF (2014) UNICEF annual report 2014 China. UNICEF China, Beijing

The Economist (2015) China’s left-behind: little match children (2015, Oct 17). The Economist

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to this study.

Financial support

This research was funded by a grant from the UK Economic and Social Research Council. No ES/L003619/1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, C., Wang, F., Li, L. et al. Long-term impacts of parental migration on Chinese children’s psychosocial well-being: mitigating and exacerbating factors. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 52, 669–677 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1386-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1386-9