Abstract

Meiosis is a process of fundamental importance for sexually reproducing eukaryotes. During meiosis, homologous chromosomes pair with each other and undergo homologous recombination, ultimately producing haploid sets of recombined chromosomes that will be inherited by the offspring. Compared with the extensive progress that has been made in understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying recombination, how homologous sequences pair with each other is still poorly understood. The diversity of the underlying mechanisms of pairing present in different organisms further increases the complexity of this problem. Involvement of meiosis-specific noncoding RNA in the pairing of homologous chromosomes has been found in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Although different organisms may have developed other or additional systems that are involved in chromosome pairing, the findings in S. pombe will provide new insights into understanding the roles of noncoding RNA in meiosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Noncoding RNA transcripts and nuclear bodies

Genome-wide analyses of transcripts have revealed that a significant portion of the RNA transcribed by RNA polymerase II is nonprotein-coding (noncoding) RNA. In the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, 371 species of noncoding RNA are predicted to be transcribed in vegetatively growing cells (Wilhelm et al 2008), but most of them are not well characterized.

RNA transcripts often form bodies inside the nucleus. Unlike protein-coding RNA, which is transported to the cytoplasm and engaged by ribosomes for translation to protein, noncoding RNA can stay in the nucleus and form nuclear RNA bodies. The most significant nuclear RNA body is the nucleolus, which is formed around the ribosomal RNA-coding genes. Several other examples of nuclear RNA bodies formed by long noncoding RNAs have been introduced in the literature (Clark and Mattrick 2011; Mao et al. 2011; Ip and Nakagawa 2012).

The best characterized long noncoding RNA in S. pombe is meiRNA, a polyadenylated noncoding RNA that forms a nuclear body in meiotic cells (Yamashita et al. 1998; Ding et al. 2012). Here, we describe the properties of the meiRNA body in light of similar RNA bodies in other species.

Roles for noncoding meiRNA in entry into meiosis

In S. pombe, the Mei2 protein is a key regulator of meiosis. It is essential for premeiotic DNA synthesis and entry into meiosis (Watanabe and Yamamoto 1994; Watanabe et al. 1997). Mei2 binds to meiRNA transcribed from the sme2 gene; meiRNA is essential for progression of meiosis (Watanabe and Yamamoto 1994). It was initially obtained as a multicopy suppressor of a mei2 mutant and was reported to be 508 nucleotides in length (Watanabe and Yamamoto 1994). However, the full length of meiRNA turned out to be 1,586 nucleotides (Ding et al. 2012; Yamashita et al. 2012). The 508 and the full-length 1,586 nucleotide meiRNAs are designated meiRNA-S and meiRNA-L, respectively (Fig. 1a). Mei2 binds to the meiRNA-S portion of meiRNA during entry into meiosis; meiRNA-L is necessary for homologous chromosome pairing. As described below, the different domains of meiRNA have different roles in meiosis entry, chromosomal retention, and homologous chromosome pairing (Fig. 1b).

Molecular dissection of meiRNA. a Schematic diagrams of the sme2 gene, the positions of DSR and poly-A sites, and transcripts of meiRNA-S, meiRNA-L, and three kinds of deletion mutants. The 0.5-kb meiRNA-S was the transcript originally annotated (Watanabe and Yamamoto 1994). A longer transcript of 1.5 kb was later characterized and named as meiRNA-L (Ding et al. 2012; Yamashita et al. 2012). b Summary table of the phenotype of meiRNA-L and deletion mutants in relation to meiosis progression; meiRNA, Mei2, and Mmi1 localization in the meiotic prophase nucleus; and robust pairing. Results for Δ1-574, Δ1058-1586, and Δ1425-1586 are adapted from a previous report (Ding et al. 2012)

Mmi1 is another protein that is known to bind meiRNA. Mmi1 is involved in the selective elimination of meiotic gene transcripts in vegetatively growing cells to prevent untimely entry into meiosis (Fig. 2a). In vegetatively growing S. pombe, transcripts from genes with meiosis-specific functions are quickly degraded by nuclear exosomes through several pathways (Harigaya et al. 2006; Sugiyama and Sugioka-Sugiyama 2011; Sugiyama et al. 2012, 2013), and one of the major pathways is the Mmi1-mediated pathway. Mmi1 is a RNA-binding protein which recognizes hexanucleotide the determinant of selective removal (DSR) motifs on meiosis-specific RNAs and induces their degradation (Harigaya et al. 2006; Yamashita et al. 2012). Mmi1-mediated degradation of meiosis-specific RNAs likely requires other proteins in addition to Mmi1. One of such factors is Red1, which is present only in mitotic cells and plays a critical role in the degradation of DSR-containing RNAs in vegetatively growing cells (Sugiyama and Sugioka-Sugiyama 2011). Thus, a role for Mmi1 is to recruit DSR-containing RNAs to the Red1-mediated degradation pathway in exosomes (Fig. 2a).

meiRNA has 13 core DSR motifs, which are distributed along its entire sequence but are more concentrated in the region between 500 and 1,000 nucleotides (Fig. 1a). Like other meiosis-specific gene products, meiRNA transcribed in vegetatively growing cells is completely degraded by the Mmi1-mediated degradation pathway; meiRNA-L can be detected in vegetatively growing cells in mmi1-deficient mutants (Yamashita et al. 2012). The meiRNA-S fragment originally identified (Watanabe and Yamamoto 1994) is probably a degradation product of meiRNA-L; the meiRNA-S fragment can be found in Mmi1-hypomorphic conditions (Yamashita et al. 2012).

In seeming contrast to the function of Mmi1 in the degradation of RNA, on entering meiosis, Mmi1 is sequestered from the RNA degradation pathway by its binding to meiRNA (Fig. 2b). meiRNA and Mmi1 form a nuclear RNA body and are sequestered away from exosomes (Harigaya et al. 2006). It is thought that meiRNA acts as a decoy for Mmi1 with the meiRNA DSR motifs acting to bind and sequester Mmi1 (Harigaya et al. 2006; Yamashita et al. 2012): meiRNA binds the Mmi1 protein and forms a RNA body in the meiotic prophase nucleus (Ding et al. 2012). Because inactivation of Mmi1 rescues the meiotic defects observed in sme2 deletion cells (Harigaya et al. 2006; Yamashita et al. 2012), a role for meiRNA in entry into meiosis is subject to sequestration of Mmi1 from the RNA degradation pathway. As a consequence, DSR-containing meiotic RNAs escape from degradation (Fig. 2b).

Although meiRNA-S was first identified as an essential noncoding RNA for entry into meiosis, it is interesting to point out that even Δ1-574 meiRNA-L, lacking this region, can promote normal progression of meiosis (Fig. 1b). Thus, we speculate that any fragment of meiRNA-L that contains a sufficient number of DSR can act as a decoy for Mmi1 and promote entry to meiosis.

Roles for noncoding meiRNA in meiotic homologous chromosome pairing

Observation of living cells demonstrated that the sme2 locus shows a significantly higher pairing frequency in the early stages of meiotic prophase and that this robust pairing requires transcription of meiRNA (Ding et al. 2012). As mentioned above, meiRNA was first annotated as a 508-nucleotide RNA (meiRNA-S) essential for the progression of meiosis. However, the DNA fragment containing meiRNA-S did not confer robust pairing. This raised the possibility that longer sme2 transcripts are necessary for robust pairing. We therefore reexamined transcripts of the sme2 gene and found a 1.5-kb RNA as the major transcript of the sme2 gene (designated meiRNA-L, as noted above) and concluded that meiRNA-L was required for robust pairing (Ding et al. 2012).

Mei2 colocalizes with meiRNA and forms a distinct body (Watanabe et al. 1997; Yamashita et al. 1998), which is located at the sme2 locus on chromosome II in the meiotic nucleus (Shimada et al. 2003). Deletion of a 5′ region of the sme2 gene (Δ1-574) resulted in a loss of the chromosomal localization of Mei2, but this Δ1-574 meiRNA-L still accumulated on the chromosome, and robust pairing of the sme2 gene locus was observed. These results indicate that the 5′ region of the sme2 gene locus is necessary for recruiting Mei2 protein to the locus, but that Mei2 recruitment is not necessary for robust pairing at the sme2 locus. Instead, the 3′ region of meiRNA-L is sufficient for robust pairing at the sme2 locus. These results suggest that the transcribed RNA accumulated at the sme2 locus may play an active role in recognition and pairing of homologous chromosomes.

A model has been previously proposed in the lily in which a group of meiosis-specific polyadenylated RNA transcripts initiate the pairing process; these RNA transcripts are collectively called “zygRNA” for zygotene transcripts (Hotta et al. 1985). zygRNA appear to encompass both protein-coding and noncoding RNA. zygRNA in the lily is homologous to zygRNA in mouse spermatocytes, suggesting a conserved mechanism across the phylogenic spectrum (Hotta et al. 1985). However, a role for zygRNA in pairing has not been directly demonstrated.

Retention of meiRNA-L on the chromosome

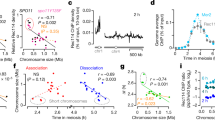

meiRNA transcripts accumulate at the sme2 gene locus (Ding et al. 2012). As discussed above, these meiRNA transcripts bind and sequester Mmi1 and also colocalize with Mei2 at the sme2 gene locus. meiRNA and its associated proteins, such as Mei2 and Mmi1, remain on the chromosome throughout meiotic prophase. Deletion of the polyadenylation sites of the sme2 gene, yielding longer read-through transcripts expressed from the sme2 gene, eliminated the meiRNA body at the sme2 locus and did not promote robust paring of the sme2 loci (Ding et al. 2012). Addition of an ADH1 terminator to the 3′ end of the polyadenylation site-deleted sme2 gene, yielding the Δ1425-1586 transcript shown in Fig. 1a, resulted in the recovery of the formation of a single meiRNA body together with Mmi1 (Fig. 3b) and recovery of robust paring (Fig. 3c). A shorter ADH1 terminator fragment (Δ1058-1586 in Fig. 1a) showed multiple small dots of meiRNA (Fig. 3a) with partial recovery of robust paring (Fig. 3c). This suggests that properly terminated meiRNA transcripts are necessary for their chromosomal retention and that chromosomal retention is necessary for the robust pairing of homologous chromosomes. Although mechanisms for retention of RNA transcripts at their respective genes are still largely unknown, these results suggest that chromosomal retention may be coupled with polyadenylation.

Localization of meiRNA and homologous pairing. a, b Time lapse imaging of meiRNA and GFP-Mmi1 in living meiotic cells of Δ1058-1586-T (a) or Δ1425-1586-T (b); the phenotype of these cells is summarized in Fig. 1b. The meiRNA transcript was visualized using a 4XU1A tag inserted at the 5′ end of the sme2 gene and a U1A–GFP fusion construct (Ding et al. 2012). Scale bar, 5 μm. In a, the 3′-end 1058-1586 DNA fragment was replaced with an ADH1 terminator and a marker gene. In b, the 3′-end 1425-1586 DNA fragment was replaced with an ADH1 terminator and a marker gene. c Pairing frequencies of the sme2 locus in the wild-type and 3′ deletion mutants are indicated. Results for Δ1058-1586 and Δ1425-1586 are adapted from a previous report (Ding et al. 2012)

Formation of a single meiRNA body in the meiotic nucleus is correlated with robust pairing of homologous chromosomes, but not with progression of meiosis (Fig. 1b). In the 3′-truncated mutants of sme2 (Δ1058-1586 and Δ1425-1586 with or without ADH1 terminator, “T”), progression of meiosis is normal, while meiRNA does not form a single dot except for Δ1425–1586-T (Fig. 1b). In a 5′-truncated mutant of sme2 (Δ1-574), Mmi1 but not Mei2 was found in the meiRNA body. Thus, Mei2 interacts with the 5′ portion of meiRNA-L, and Mmi1 is sequestered by meiRNA independently of Mei2 (Fig. 4a). Finally, the results presented here indicate that the meiRNA body is necessary for the robust pairing of homologous chromosomes at the sme2 locus.

A model for RNA-mediated homologous chromosome recognition. a Distinct functional domains of meiRNA. The meiRNA transcript can be divided into two distinct domains: the 5′ portion of meiRNA-L corresponding to meiRNA-S and the 3′-extended region specific to meiRNA-L. The Mei2 protein binds to meiRNA-S. The Mmi1 protein binds to DSR motifs. We speculate that as yet unknown proteins may bind to the 3′ end of meiRNA-L and play a role in retention of RNA on the chromosome. b Complexes containing RNA transcripts act as chromosome recognition sites along each of the chromosomes aligned by telomeres. c To find a homologous chromosome partner, recognition complexes (yellow, green, and orange bulbs) on homologous chromosome arms, as shown in a, are aligned by telomere-mediated chromosome movements. Telomeres and centromeres are indicated by blue- and red-filled small spheres. Panels b and c are reproduced from Ding et al. (2012)

RNA bodies mediate recognition of homologous loci

It has been proposed that interactions between homologous DNAs with double-strand break (DSB) are involved in homology searching in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Gerton and Hawley 2005). On the other hand, there are many examples in which homologous pairing occurs independently of DSB formation (Gerton and Hawley 2005; Zickler 2006). As a common phenomenon in many organisms, it is known that chromosomes are bundled at the telomere in meiotic prophase (reviewed in Scherthan 2001; Hiraoka and Dernburg 2009). In nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, special nontelomeric chromosomal regions play a role analogous to telomeres, acting as a pairing center (Villeneuve 1994; MacQueen et al. 2005); the pairing center is bound by one of the four zinc finger proteins HIM-8, ZIM-1, ZIM-2, and ZIM-3, which provide a mechanism for homologous recognition (Phillips et al. 2005; Phillips and Dernburg 2006). However, involvement of RNA in this mechanism is unknown.

In S. pombe, homologous pairing is promoted by clustering and movements of telomeres prior to DSB formation (Chikashige et al. 1994, 2006; Ding et al. 2004, 2010; reviewed in Chikashige et al. 2007; Hiraoka and Dernburg 2009). During this process, meiRNA-L directly or indirectly mediates robust pairing at the sme2 locus. This pairing is independent of DSB formation and, hence, independent of recombination (Ding et al. 2012). This strongly suggests that chromosomes can recognize their homologous partners without direct interaction between DNA sequences. Rather, homozygous transcription of the meiRNA-L sequence is essential for the robust pairing at the sme2 locus. These results suggest a model in which RNA transcripts accumulate at their respective gene loci and act as recognition sites in homology searching. RNA may be directly involved in the recognition of homologous loci through RNA–RNA or RNA–DNA interactions. It should be pointed out, however, that the recognition by RNA–DNA interaction is less likely as homozygous transcription of meiRNA-L is required for robust pairing. Alternatively, meiRNA-L may play a role in recruiting specific RNA-binding proteins essential for recognition. As discussed above, Mei2 forms a distinct dot at the sme2 locus, but Mei2 protein alone was not found to be necessary to confer robust pairing. In addition to Mei2, at least three other proteins, Mmi1, Spo5, and Dot2, also colocalize at the sme2 locus in meiotic prophase (Harigaya et al. 2006; Jin et al. 2005; Kasama et al. 2006). Spo5 localization, like Mmi1, is independent of Mei2 (Kasama et al. 2006). To date, components critical for robust pairing have not been identified among these proteins. It is possible that other unidentified critical factors may be contained in the meiRNA body.

Alternatively, specific components may not be necessary. RNA transcripts can form nuclear bodies at their respective gene loci autonomously (Mao et al. 2011; Shevtsov and Dundr 2011; Carmo-Fonseca and Rino 2011), and a linear array of transcription factories formed along the chromosome may act as a bar code for recognition of homologous chromosomes as proposed previously (Cook 1997; Xu and Cook 2008). Considering that telomere clustering precedes pairing of homologous chromosomes (Ding et al. 2004, 2010), such models provide a possible mechanism for how RNA bodies result in recognition and pairing of homologous chromosomes when chromosomes are prealigned by telomere clustering (Fig. 4b, c).

It should be emphasized that the transcription itself or chromatin structural changes associated with transcription are not driving forces for the recognition of homologous chromosomes. Instead, RNA bodies formed on the chromosome are important because robust pairing is not promoted when transcripts are not retained on the chromosome. A search for other chromosome loci which trigger the pairing of homologous chromosomes in meiosis is underway. Chromosomal loci from which noncoding (or protein-coding) RNA is transcribed in the early stages of meiosis may be candidates for such pairing sites in S. pombe. Arrays of RNA bodies along chromosomes likely act as chromosome identifiers for the recognition of homologous chromosomes. Further studies will provide more insight into the role of RNA nuclear bodies in the recognition of homologous loci during meiosis.

Abbreviations

- DSB:

-

Double-strand break

- DSR:

-

Determinant of selective removal

- meiRNA:

-

Noncoding RNA in meiotic cells

- zygRNA:

-

Zygotene transcript

References

Carmo-Fonseca M, Rino J (2011) RNA seeds nuclear bodies. Nat Cell Biol 13:110–112. doi:10.1038/ncb0211-110

Chikashige Y, Ding DQ, Funabiki H, Haraguchi T, Mashiko S, Yanagida M, Hiraoka Y (1994) Telomere-led premeiotic chromosome movement in fission yeast. Science 264:270–273. doi:10.1126/science.8146661

Chikashige Y, Tsutsumi C, Yamane M, Okamasa K, Haraguchi T, Hiraoka Y (2006) Meiotic proteins bqt1 and bqt2 tether telomeres to form the bouquet arrangement of chromosomes. Cell 125:59–69. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.048

Chikashige Y, Haraguchi T, Hiraoka Y (2007) Another way to move chromosomes. Chromosoma 116:497–505. doi:10.1007/s00412-007-0114-8

Clark MB, Mattrick JS (2011) Long noncoding RNAs in cell biology. Semin Cell Dev Biol 22(4):366–376. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.01.001

Cook PR (1997) The transcriptional basis of chromosome pairing. J Cell Sci 110(Pt9):1033–1040

Ding DQ, Yamamoto A, Haraguchi T, Hiraoka Y (2004) Dynamics of homologous chromosome pairing during meiotic prophase in fission yeast. Dev Cell 6:329–341. doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00059-0

Ding DQ, Haraguchi T, Hiraoka Y (2010) From meiosis to postmeiotic events: alignment and recognition of homologous chromosomes in meiosis. FEBS J 277:565–570. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07501.x

Ding DQ, Okamasa K, Yamane M, Tsutsumi C, Haraguchi T, Yamamoto M, Hiraoka Y (2012) Meiosis-specific noncoding RNA mediates robust pairing of homologous chromosomes in meiosis. Science 336:732–736. doi:10.1126/science.1219518

Gerton JL, Hawley RS (2005) Homologous chromosome interactions in meiosis: diversity amidst conservation. Nat Rev Genet 6:477–487. doi:10.1038/nrg1614

Harigaya Y, Tanaka H, Yamanaka S, Tanaka K, Watanabe Y, Tsutsumi C, Chikashige Y, Hiraoka Y, Yamashita A, Yamamoto M (2006) Selective elimination of messenger RNA prevents an incidence of untimely meiosis. Nature 442:45–50. doi:10.1038/nature04881

Hiraoka Y, Dernburg AF (2009) The SUN rises on meiotic chromosome dynamics. Dev Cell 17:598–605. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.014

Hotta Y, Tabata S, Stubbs L, Stern H (1985) Meiosis-specific transcripts of a DNA component replicated during chromosome pairing: homology across the phylogenetic spectrum. Cell 40:785–793. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(85)90338-1

Ip JY, Nakagawa S (2012) Long non-coding RNAs in nuclear bodies. Dev Growth Differ 54:44–54. doi:10.1111/j.1440-169X.2011.01303.x

Jin Y, Mancuso JJ, Uzawa S, Cronembold D, Cande WZ (2005) The fission yeast homolog of the human transcription factor EAP30 blocks meiotic spindle pole body amplification. Dev Cell 9:63–73. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2005.04.016

Kasama T, Shigehisa A, Hirata A, Saito TT, Tougan T, Okuzaki D, Nojima H (2006) Spo5/Mug12, a putative meiosis-specific RNA-binding protein, is essential for meiotic progression and forms Mei2 dot-like nuclear foci. Eukaryotic Cell 5:1301–1313. doi:10.1128/EC.00099-06

MacQueen AJ, Phillips CM, Bhalla N, Weiser P, Villeneuve AM, Dernburg AF (2005) Chromosome sites play dual roles to establish homologous synapsis during meiosis in C. elegans. Cell 123:1037–1050. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.034

Mao YS, Sunwoo H, Zhang B, Spector DL (2011) Direct visualization of the co-transcriptional assembly of a nuclear body by noncoding RNAs. Nat Cell Biol 13:95–101. doi:10.1038/ncb2140

Phillips CM, Dernburg AF (2006) A family of zinc-finger proteins is required for chromosome-specific pairing and synapsis during meiosis in C. elegans. Dev Cell 11:817–829. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.020

Phillips CM, Wong C, Bhalla N, Carlton PM, Weiser P, Meneely PM, Dernburg AF (2005) HIM-8 binds to the X chromosome pairing center and mediates chromosome-specific meiotic synapsis. Cell 12:1051–1063. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.035

Scherthan H (2001) A bouquet makes ends meet. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2:621–627. doi:10.1038/35085086

Shevtsov SP, Dundr M (2011) Nucleation of nuclear bodies by RNA. Nat Cell Biol 13:167–173. doi:10.1038/ncb2157

Shimada T, Yamashita A, Yamamoto M (2003) The fission yeast meiotic regulator Mei2p forms a dot structure in the horse-tail nucleus in association with the sme2 locus on chromosome II. Mol Biol Cell 14:2461–2469. doi:10.1091/mbc.E02-11-0738

Sugiyama T, Sugioka-Sugiyama R (2011) Red1 promotes the elimination of meiosis-specific mRNAs in vegetatively growing fission yeast. EMBO J 30:1027–1039. doi:10.1038/emboj.2011.32

Sugiyama T, Sugioka-Sugiyama R, Hada K, Niwa R (2012) Rhn1, a nuclear protein, is required for suppression of meiotic mRNAs in mitotically dividing fission yeast. PLoS One 7(8):e42962. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042962

Sugiyama T, Wanatabe N, Kitahara E, Tani T, Sugioka-Sugiyama R (2013) Red5 and three nuclear pore components are essential for efficient suppression of specific mRNAs during vegetative growth of fission yeast. Nucl Acids Res 41(13):6674–6686. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt363

Villeneuve AM (1994) A cis-acting locus that promotes crossing over between X chromosomes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 136:887–902

Watanabe Y, Yamamoto M (1994) S. pombe mei2+ encodes an RNA-binding protein essential for premeiotic DNA synthesis and meiosis I, which cooperates with a novel RNA species meiRNA. Cell 78:487–498. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(94)90426-X

Watanabe Y, Shinozaki-Yabana S, Chikashige Y, Hiraoka Y, Yamamoto M (1997) Phosphorylation of RNA-binding protein controls cell cycle switch from mitotic to meiotic in fission yeast. Nature 386:187–190. doi:10.1038/386187a0

Wilhelm BT, Marguerat S, Watt S, Schubert F, Wood V, Goodhead I, Penkett CJ, Rogers J, Bahler J (2008) Dynamic repertoire of a eukaryotic transcriptome surveyed at single-nucleotide resolution. Nature 453:1239–1243. doi:10.1038/nature07002

Xu M, Cook PR (2008) The role of specialized transcription factories in chromosome pairing. Biochim Biophys Acta 1783:2155–2160. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.07.013

Yamashita A, Watanabe Y, Nukina N, Yamamoto M (1998) RNA-assisted nuclear transport of the meiotic regulator Mei2p in fission yeast. Cell 95:115–123. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81787-0

Yamashita A, Shichino Y, Tanaka H, Hiriart E, Touat-Todeschini L, Vavasseur A, Ding DQ, Hiraoka Y, Verdel A, Yamamoto M (2012) Hexanucleotide motifs mediate recruitment of the RNA elimination machinery to silent meiotic genes. Open Biol J 2:120014

Zickler D (2006) From early homologue recognition to synaptonemal complex formation. Chromosoma 115:158–174. doi:10.1007/s00412-006-0048-6

Acknowledgments

We thank David Alexander for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the MEXT Japan to D.-Q. Ding, T. Haraguchi, and Y. Hiraoka.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Brian P. Chadwick, Kristin C. Scott, and Beth A. Sullivan

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, DQ., Haraguchi, T. & Hiraoka, Y. The role of chromosomal retention of noncoding RNA in meiosis. Chromosome Res 21, 665–672 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10577-013-9389-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10577-013-9389-1