Abstract

Mental health and wellbeing problems in middle childhood are increasing worldwide which needs more support than just clinical services. Early intervention has been explored in other settings, but not in extended education care settings such as outside school hours care (OSHC). A systematic literature review was undertaken to determine what interventions have been tested in extended education settings to address or promote emotional, behavioural, or social wellbeing in children, and to assess how effective they have been. A PRISMA guided search found seven peer reviewed articles from an initial pool of 458. Data from the articles were extracted and the mixed method appraisal tool (MMAT) was applied to assess methodological quality of the studies design, data collection, and analyses. The final selections were methodologically heterogeneous with an average MMAT quality rating of 71%. All but one of the interventions were delivered to children in small group settings and were a mix of activities. Studies that trained educators to deliver the interventions were limited and no data were collected for them. The two interventions that trained educators to deliver content to children were seen as promising. This review showed an overall paucity of research examining interventions delivered in extended education settings to improve children’s wellbeing. Given variations in extended education services and the absence of formal qualifications required for educators, further research is needed to understand what interventions may be effective and what role educators could play in such interventions or in supporting children’s wellbeing in extended education.

This review protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO. Registration ID: CRD42023485541 on 03/12/2023.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Outside school hours care (OSHC) services are the fastest growing childcare services in Australia (Cartmel, 2019; Social Research Centre, 2022), providing care to primary school-aged children before and after school, and during school holidays. OSHC is also known by other names internationally, such as school-aged care (SAC) (Department of Education Employment and Workplace Relations, 2011), School-Aged Educare (Klerfelt & Haglund, 2014), Extended Education (Bae, 2019), or outside school time (OST) (Malone, 2017). In some countries, including Australia these services are typically run by organisations external to the school, but occur on school grounds. Considering the wide naming variations, the international research community has broadly adopted the term ‘extended education’ to define the interdisciplinary field of research (Bae, 2019) and this term will be used hereafter. This term refers to settings that (a) include intentionally organised activities, learning, and/or developmental programs, (b) incorporate teaching, learning, and/or development that occurs between adult professionals and young people, (c) occurs outside of school time, such as before and after school, and on school holidays, (d) mostly occurs in a school setting, and is voluntary to attend (Bae & Kanefuji, 2018).

For example, USA-based extended education services are typically seen as places for enrichment with specialised offerings for children (e.g., technology, academic, or art clubs) (Minney et al., 2019) or free play opportunities that allow social-emotional skill development (Noam & Triggs, 2018). In Nordic and Central European countries such as Sweden, Iceland and Germany, after school care is integrated into formal education so that children attend all day schools that cater for learning in formal and informal settings (e.g. Fischer et al., 2014). These settings, researchers believe, contribute to children’s learning and wellbeing as well as to their formal education and potentially, to society as a whole (Klerfelt & Stecher, 2018).

Variations also exist in international social, political, historical and educational needs of extended education that determine how it is offered in each country (Bae, 2019). Researchers in this field highlight the importance of learning that does not occur in the formal educational space of school (Stecher, 2019) and where childhood development and social-emotional learning is valued (Bae, 2019; White et al., 2022). A growing body of evidence shows the social-emotional benefits to children who attend extended education (Durlak & Weissberg, 2007) and that building these skills contribute to long-term academic and life success (Noam & Triggs, 2018). It is therefore important that educators in extended education settings are equipped to support children’s mental health and wellbeing development.

Worldwide, millions of children attend extended education services, often spending more time with extended education educators than with a classroom teacher. In Australia, nearly half a million children (25% of the 5–11 year old population) attend extended education (Social Research Centre, 2022) while in the US 35% of all children aged 6–13 years attend these services (Administration for Children and Families (DHHS) Office of Child Care, 2022a, 2022b). Attendance rates in Europe are similar, with 35% of 6–11 year olds attending extended education services in 29 EU countries and up to 65% of children in some Nordic countries such as Denmark, Slovenia, and Sweden (OECD Family Database, 2022). Despite this, there has been little national or international research interest in the time children spend in extended education.

In Australia, extended education services (OSHC) promote play and leisure for the children in their care, and the pedagogical framework that guides OSHC—My Time, Our Place Framework for School-Age Care in Australia 2.0 (MTOP)—emphasises the importance of children’s development of agency, wellbeing, and social and emotional skills (Australian Government Department of Education (ADGE), 2023). This emphasis on wellbeing is seen internationally as well. For example, the US’ adoption of the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) model recognises the social and emotional climate in extended education as an important factor for children to grow up safe, healthy, engaged, challenged, and supported (ASCD & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). Some European countries have also enshrined social, emotional, and wellbeing development in policy, such as Scotland’s national approach—Getting it Right for Every Child—which underpins and supports all adults who work with children (including in extended education) to be able to recognise and respond to children’s wellbeing (The Scottish Government, 2019).

Despite the focus on wellbeing in frameworks that govern the implementation of extended education services internationally, little is known in the academic literature about how these educators support the development of children’s social and emotional skills in their day-to-day work, and what interventions have been implemented in extended education services to promote wellbeing or positive mental health. Further, researchers in the emerging field of extended education encourage interdisciplinary studies to better understand children’s outcomes in these settings (Bae, 2019; Stecher, 2019).

Mental Health in Middle Childhood

The World Health Organization (2022) defines mental health as a state of wellbeing that allows people to cope with stress, learn and work well, reach their capabilities, and contribute to their community. For children especially, a key component of mental health and wellbeing is social and emotional competence (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, 2020). One in seven Australian children aged 4 to 17 years live with a mental health disorder and mental illness is the largest cause of disability and health burden in this age group (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, 2020). This finding is also echoed in international literature, with a worldwide prevalence of mental health disorders in children of 13.4% (Polanczyk et al., 2015). The most common mental health diagnoses in this age group include attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, depression, and conduct disorders (Lawrence et al., 2015). While these data are the most recent prevalence statistics, international literature indicates higher rates of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress symptoms experienced by children during the COVID-19 pandemic (Marques de Miranda et al., 2020) and US paediatricians and mental health experts predict long-term impacts on children’s mental health, especially for those already experiencing difficulties (Rider et al., 2021). Considering mental health difficulties in this age group are high and are likely increasing, it is important to understand the impacts this may have.

Children who experience poor mental health also show problems in social, behavioural, and emotional skills, and poor wellbeing. For example, children who may be struggling with their mental health (whether diagnosed or undiagnosed) can show a lack of social awareness and reciprocity, difficulties managing their emotions (e.g., outbursts of anger, expressing fear in non-threatening situations) and a range of behaviours that are either confrontational (violent and aggressive) or avoidant (e.g., not engaging in exploratory play) depending on the mental health problem (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Such behaviours will potentially present and interfere with functioning in daily settings such as school and extended education, with educators required to identify and manage such behaviours as well as promote positive mental health amongst all children. It is therefore important for educators in extended education settings to have a good understanding of typical childhood development and mental health, to understand how mental health might impact daily behaviours, functioning and interpersonal relationships and to know how to support children.

Wellbeing in Care Settings

Despite the large number of children enrolled in extended education internationally and the high prevalence of social, emotional, and behavioural difficulties in this age group, educators responsible for these children are not required to hold qualifications or formal training in child development, wellbeing, or mental health in Australia. Other countries qualifications requirements vary. Further, there are a lack of formal training programs developed specifically for Australian extended education settings (Cartmel & Brannelly, 2016; Cartmel et al., 2020), specifically those that train educators in how to recognise and support children with mental health difficulties. Thus, there is a need for research to identify solutions to improve educator capacity to manage children’s wellbeing and promote positive mental health in extended education.

The objective of this systematic literature review (SLR) is to determine what strategies and interventions have been tested in extended education settings to address or promote emotional, behavioural, or social wellbeing in children, and to assess how effective those strategies or interventions have been. Given this is an international issue and similar problems are evident worldwide, this SLR was conducted on international literature.

Methods

A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; (Page et al., 2021) protocol was developed to guide the review and to maintain transparency. To address the objectives, several inclusion criteria were considered to ensure a relevant selection of studies were included. First, the studies must have been conducted in an extended education setting or with extended education staff to bring about change in extended education. Second, the studies must have introduced strategies or interventions designed to address or promote psychological constructs, including emotional, social, or behavioural wellbeing or development within a cohort of primary school-aged children (4–12 years). Studies were included if the tested strategies aimed to train or educate children in behavioural, social, or emotional wellbeing, or train educators in how to address or support the social, emotional, developmental, or behavioural wellbeing of children. Therefore, the population of interest was children and educators who work at extended education services. No restrictions were placed on gender, and studies from any country in the world were included if the article was accessible in English. Additionally, the studies must have examined the outcomes of the strategies, program, or intervention; specifically, the study must have included a measure of efficacy to show whether the program was effective. These outcomes could be educator-focused (e.g., educator levels of mental health and wellbeing literacy, self-efficacy and/or confidence), or child-/caregiver-focused (e.g., child or caregiver satisfaction with the intervention, changes in child wellbeing). This review included studies that measured qualitative or quantitative outcomes. Studies were excluded if they related only to primary school settings (without extended education context), those that focused on extended education itself as an intervention (i.e., the overall benefits to children attending extended education), and participants who were outside of the age range (i.e., under 4 years or over 12 years old).

Search Strategy

The search string and strategy was determined in consultation with a Research Librarian. An electronic search was conducted in December 2023 with the following databases: EbscoHost Megafile, Scopus, SAGE Journals, Taylor & Francis, Web of Science, and Wiley Online Library. In September 2023 Australian and international extended education researchers were consulted at an extended education conference for additional relevant academic research to extended education and for clarification of search terms. Reference lists were hand searched to ensure inclusion of relevant studies.

The search terms were selected to include the four key constructs: after school care and names it is known by (“Outside Hours School” OR “After School Care” OR “After School Recreation” OR “School Age Care” OR “Out of School Hours” OR “School-Age Educare” OR “Extended Education”), mental health (“wellbeing” OR “well-being” OR “well being” OR “mental health” OR emotion* OR socio-emotional OR social OR behavioural OR develop*), the addition of an intervention (assess* OR strategies OR treatment OR program OR support OR education OR intervention), and the relevant age group of children (child* OR “primary school” OR “elementary school” OR “middle childhood”). After an initial search returned more than 50,000 articles, the search was narrowed to title and abstracts as they were determined to show the relevant results.

Data Extraction

Two main reviewers firstly agreed on the clarity of terminology and the data to be collected before extraction. The reviewers assessed the relevancy of studies against the inclusion criteria independently at each phase of the literature search and agreed on results before moving to the next phase. A third reviewer was available to resolve any disagreements.

The following data were extracted from each of the included studies using an Excel data extraction template: title, author/s, publication year, country, study design, sample size, participant information, age range, participant gender, intervention name and description, delivery mode, location, target population, target skill/s, duration, frequency, who delivered the intervention and how, outcome measure, type of analysis, results of the study, limitations, and author notes (recommendations, comments, or concerns).

Due to the variation in study design and constructs targeted in each of the included studies, a meta-analysis was not deemed to be appropriate. Instead, a narrative synthesis was completed to provide a fusion of findings, explore relationships between the studies, assess robustness of the studies, and to group the findings by characteristics.

Quality Evaluation

The mixed-methods appraisal tool (MMAT; Hong et al., 2018) was used to critically evaluate the quality of each study due to the variations in quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods research designs of each. The MMAT was originally published in 2009 (Pluye et al., 2009) and has since been refined in 2011 (Pace et al., 2011) and in 2018 (Hong et al., 2018). Each version of the MMAT has undergone validity testing for interrater reliability, efficacy, and content validity, with the most recent showing excellent interrater agreement (d = 0.87–1.0) on the items (Hong et al., 2019).

The MMAT allows concurrent appraisal of the methodological quality of five research methods: qualitative, randomised control trial, non-randomised studies, quantitative, and mixed method studies. The first part is a screening checklist that asks, ‘are there clear research questions?’ and ‘do the collected data allow to address the research questions?’ The second part outlines five criteria assessing each of the five methodologies with responses of ‘Yes’, ‘No’, or ‘Can’t tell’.

As in the data extraction stage, two reviewers independently applied the MMAT criteria to each of the selected studies before discussing findings. A third reviewer was available to resolve any disagreements. The authors of the MMAT advise that sensitive analysis of the MMAT should take precedence over a simple tally; however, also recognise that reporting the results without a descriptive scoring system may be problematic (Hong et al., 2018). For this reason, an overall percentage score of each studies’ methodological quality will be offered along with a narrative analysis.

Results

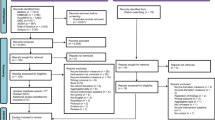

Results of the search and screening process are presented in Fig. 1. The initial search returned 395 records. After duplicate records were removed, 218 records underwent title and abstract screening, with 185 records excluded at this stage for not meeting the full inclusion criteria. Articles were sought for full-text retrieval for further screening, and out of 33 full-text articles, 7 were selected for the final sample. Articles were most commonly excluded when the study investigated the extended education service as an intervention and there were no interventions introduced with the included outcomes. Due to naming conventions within Australia and internationally, four articles were excluded that did not conduct research in an extended education environment, typically because of the search string “out of school hours”. The PRISMA protocol flow chart is shown in Fig. 1 and details exclusion reasons at each step.

The seven included studies that comprise this review indicate the dearth of academic interest in children’s mental health and wellbeing outcomes in extended education settings and how educators understand and support these. Academic interest in this topic began less than 15 years ago (Bazyk & Bazyk, 2009), and half of the included studies occurred only in the past 5 years (Fettig et al., 2018; Minney et al., 2019; Siddiqui et al., 2019). A total of 1798 participants took part in the seven studies, although 1231 of these were from the one study (Siddiqui et al., 2019). Of the total participants, only 32 were adults (educators and volunteers; Milton et al., 2023) of the remaining, all were children and 967 of them participated in the interventions (the remainder were in control groups). This shows there were very few data gathered about educators, even in the three studies where the educators assisted in delivered the intervention to the children. Table 1 details the author, year, intervention cohort, intervention description, and intervention details and delivery for each of the included studies.

The methods and outcomes of each of the studies is examined in more detail in Table 2. With respect to the skills targeted in each intervention, most aimed to improve social-emotional skills (Bazyk & Bazyk, 2009; Fettig et al., 2018; Gooding, 2010; Minney et al., 2019), while the remaining three studies targeted a mixture of emotional, social, wellbeing, individual and community building skills (e.g., identifying masked feelings, teamwork, self-esteem, connect communities, etc.) (Kumschick et al., 2014; Siddiqui et al., 2019). The target population in each study was always children, however, some studies specified groups. For example, Bazyk and Bazyk’s (2009) study only included low socioeconomic African American children, Fettig et al. (2018) only included children at risk of emotional and behavioural problems, and Siddiqui et al. (2019) only offered the intervention to year 5 students.

Of the seven studies reported in this review, one employed qualitative methodology (Bazyk & Bazyk, 2009), three implemented non-randomised control trials (Kumschick et al., 2014; Minney et al., 2019; Siddiqui et al., 2019), one randomised control trial (Gooding, 2010), and two were mixed method studies (Fettig et al., 2018). Analyses varied in every study as shown in Table 2.

Summary of Interventions

Only seven social and emotional or mental health interventions in extended education settings were found in the academic literature, highlighting the paucity of research. Of these, only three focused on creating extended education-specific interventions and delivered training to extended education educators themselves to support children’s social-emotional skills (Milton et al., 2023; Minney et al., 2019; Siddiqui et al., 2019). Reading stories with explicit SEL content was explored in two interventions which also focused on improving language and vocabulary through games, activities, and play (Fettig et al., 2018; Kumschick et al., 2014). While positive attainment of most of these skills was found, Fettig et al.’s (2018) participant population only included four children and Kumschick et al (2014) found no significant improvement in one SEL skill (recognition of masked feelings) and no between group differences when presented with a new book, indicating the measured improvements did not carry over to a new book.

Recognising a disparity in developmental outcomes for children in low socio-economic areas and a need for structured leisure activities outside of school time, Bazyk and Bazyk (2009), in the earliest example of introduced intervention, sought to improve low-income children’s social-emotional competencies through structured small group emotional and craft activities. While their content analysis of participant interviews showed themes indicating the groups were fun and children learned healthy ways to express feelings, there were no comparison groups or direct measurement of the stated skill improvements.

With a particular focus on disaffected youth and those who might be disadvantaged, Siddiqui et al (2019) evaluated the outcomes of the CU program, specifically focusing on cognitive and non-cognitive (i.e., SEL) skills building. Disadvantaged students showed greater attainment in non-cognitive skills of teamwork and social responsibility in this study. However, effect sizes for other non-cognitive and cognitive skills were small for all participants. Further, due to the variability of offerings for this intervention across multiple schools there was no further detail about which activities in particular showed greater skill attainment.

Gooding (2010) developed a CBT music therapy intervention delivered to small groups within extended education settings as well as schools and youth centres as part of a doctoral thesis. The aim was to improve children’s peer relation and self-management skills; however, while the children in this study showed improvements in these skills, so too did the control group, indicating the results may have been due to other factors such as child development more broadly.

The seven selected studies all trialled small group interventions designed to improve various social, emotional, and wellbeing skills of children already attending extended education settings. Four of the six interventions (Bazyk & Bazyk, 2009; Fettig et al., 2018; Gooding, 2010; Kumschick et al., 2014) in this review ran group sessions with the children that required a commitment of between 45 min and an hour and a half a week, for between 5 and 26 weeks. The children assigned to control in these studies participated in usual extended education activities. The intervention delivered by Siddiqui et al. (2019) is difficult to comment on due to the variations in the ways each school could offer the intervention. Minney et al (2019) and Milton et al. (2023) are the only interventions that trained the extended education educators themselves and offered all children in each of the extended education sites the opportunity to participate.

The researchers in the selected studies all highlighted extended education as an ideal environment to offer the designed interventions due to meeting inherent social, behavioural, and developmental needs. However, for most of these studies the extended education environment was not the focus of the intervention. Only Minney et al. (2019) and Milton et al. (2023) developed an extended education-specific intervention that was designed for adults to support all children who attend extended education.

Quality Appraisal

The methodological quality of each included study was critically appraised using the MMAT, with the results displayed in Table 3. All but one study (Siddiqui et al., 2019) adhered to a high-quality methodological approach for their methodology type. While the authors of the MMAT do not recommend simply providing an overall score as it can mask problematic aspects of the study (Hong et al., 2018), a percentage rating is graphically depicted below. Four of the studies were rated at 80% or higher and were either randomised or non-randomised control trials. Interestingly, the only qualitative study was rated the highest in terms of methodological quality. The methodological quality of the studies averaged a rating of 71%.

Discussion

This systematic literature review set out to examine the international literature to understand what, if any, interventions had been applied in extended education settings to improve children’s behavioural, social, and/or emotional wellbeing through either child or educator-focused training. A structured search and data collection following the PRISMA protocol found only seven international studies met the inclusion criteria. These seven studies provided a mixture of methodologies which consisted of varying designs and outcomes. This review highlights the lack of clarity in regard to which interventions are known to promote social, emotional, behavioural skills or mental health in extended education contexts. There was evidence to support programs designed specifically for extended education when services and educators are involved in intervention delivery. While the interventions varied significantly between studies, the cohort target, outcomes, and purpose of each intervention showed considerable homogeneity across studies in this review.

Strength of Evidence for Interventions

While the quality of these studies was generally rated highly as appraised by the MMAT (Hong et al., 2018), the overall strength of evidence was relatively weak, due to the lack of studies overall, and the lack of Clinical trials conducted. For the interventions that showed positive effects, only Level 2.c evidence (quasi-experimental prospectively controlled study designs) was provided for the CU program (Siddiqui et al., 2019), reading groups with feelings board game (Kumschick et al., 2014), and for the whole service small groups intervention delivered by educators (Minney et al., 2019). Level 3.e evidence (observational study without a control group design) was provided for occupational therapy groups (Bazyk & Bazyk, 2009), CP3 program (Milton et al., 2023), and the dialogic story reading intervention (Fettig et al., 2018). This systematic review has therefore indicated a gap in the literature for high-quality, evidence driven interventions and Clinical trials.

Based on the evidence to date, no interventions have been identified to specifically develop children’s behavioural wellbeing or mental health in extended education contexts. All interventions focused on SEL competencies and results of this review show that the educator delivered small group intervention which targeted self-management and social awareness skills was most effective (Minney et al., 2019). This study also demonstrated the highest level of evidence for this review (The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2014) and a high-quality MMAT rating (Hong et al., 2018). Table 4 provides comparisons of the methodological quality and level of evidence for each intervention, as well as how well the outcomes were achieved and ranks them in order of efficacy.

The only other intervention with positive outcomes, but lower strength of overall evidence was the dialogic reading intervention (Kumschick et al., 2014). CP3 (Milton et al., 2023), SFSR (Fettig et al., 2018), and CU (Siddiqui et al., 2019) provided limited overall evidence; however, it should be noted that CP3 was only in the evaluation phase of research and the outcomes have not yet been explicitly tested. The remaining two interventions were considered as providing limited evidence despite high-quality methodological designs as they either did not show positive effects in social competence or social skills (Gooding, 2010) or did not provide evidence of increased skills (Bazyk & Bazyk, 2009).

Educators

There appears to be an almost complete absence of research examining interventions delivered to or by educators with the results of this review showing all interventions delivered in extended education settings were designed to be delivered only to children. In all but three interventions (Minney et al., 2019; Siddiqui et al., 2019), educators did not deliver the interventions and did not receive support either during or after the research. For the studies that did include educators delivering the interventions, only Milton et al. (2023) collected some baseline details; however, none sought information regarding their ability or effectiveness in supporting children’s social, behavioural, or emotional wellbeing. In the limited research that exists, only two interventions Milton et al. (2023) and Minney et al. (2019) attempted to upskill educators in their ability to manage children’s social-emotional, behavioural, or mental health knowledge. Thus, future research would benefit from focusing on this specific area.

The recent MTOP update explicitly discusses the mental health of children and increases the provision for educators to provide for the wellbeing of children in their care (Department of Education for the Ministerial Council, 2022). ‘Outcome 3: Children and young people have a strong sense of wellbeing’ now highlights educators’ unique position to support children’s mental health and wellbeing through attuned care and by creating child safe cultures and environments appropriate to their development and needs (Department of Education for the Ministerial Council, 2022). It will be important that extended education services and educators can demonstrate adherence to these updates.

Extended Education as an Intervention

Although this review found only seven studies examining interventions implemented in extended education settings, there has been international interest in the social and emotional outcomes associated with extended education attendance in general. The consensus of this mostly US-based quantitative literature shows many positive SEL outcomes from attending extended education (e.g., Durlak et al., 2010); however, extended education takes many forms internationally. For example, a meta-analysis of services that offer activities after school in the US found that the 52 included extended education programs showed a significant positive effect on children’s feelings, behaviour, and attitudes to school (Durlak et al., 2010) As this analysis investigated studies of all after school activities, many of the included interventions were not conducted in a typical extended education setting (e.g., drug prevention program, Little League, etc.) or evaluated extended education as the intervention and therefore did not meet the inclusion criteria of our study, but provides positive support for wellbeing promotion in these settings. Highlighting the difficulties conducting research in this area, Durlak et al. (2010) discussed the lack of equivalence between services, making it difficult to make meaningful comparisons. Further, considering only one of the seven studies used qualitative methodology (Bazyk & Bazyk, 2009), this should be a focus in future research.

Limitations

This study was limited by the lack of peer reviewed literature examining introduced social-emotional and mental health support in extended education settings. Until recently, this has not been considered in the literature and highlights a gap in the research. Research in Australia has been particularly lacking; however, it is positive to see work is beginning in the area. Second, the heterogeneity of included interventions prevented meaningful overall data comparisons or conclusions. This again highlights the importance of research to provide aggregated data that will support effective mental health interventions in extended education. Third, only peer reviewed research was included in the search criteria and does not account for any informal interventions introduced in extended education or any unpublished research in progress. Finally, although extended education researchers in Australia were consulted for alternative terms for extended education or conceptions of mental health and wellbeing, there may be search terms that have been unintentionally overlooked.

Recommendations and Conclusion

This is the first systematic review to investigate interventions to improve social, emotional, and/or behavioural wellbeing in extended education settings. Children were the target cohort of all the seven interventions, with the studies highlighting various ways to increase social and emotional skills, but not behaviour skills or mental health directly. While training educators in the delivery of social and emotional content showed promise in teaching children self-management and social awareness skills, none of the studies examined educators’ capability and self-efficacy to deliver any such interventions in extended education. Given the dearth of studies identified, future research should focus on conducting high-quality trials of various interventions to improve SEL and mental health in extended education contexts. Future research should also consider educators’ knowledge of, capability, and confidence to support children’s mental health and wellbeing in these settings. Research should include qualitative data (such as interviews or open ended questions) to ensure educator and mental health expert input to developing strategic supports and interventions. There is an urgent need for more research into strategies and interventions to promote positive emotional and behavioural development and mental health within school-aged children via extended education contexts.

Data Availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available on the Harvard Dataverse website: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/6W79DK.

References

Administration for Children and Families (DHHS) Office of Child Care. (2022b). FY 2020 preliminary data table 9—Average monthly percentages of children in care by age group. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/data/fy-2020-preliminary-data-table-9

Administration for Children and Families (DHHS) Office of Child Care. (2022a). FY 2020 preliminary data table 1—Average monthly adjusted number of families and children served. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/data/fy-2020-preliminary-data-table-1

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

ASCD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Whole school, whole community, whole child: A collaborative approach to learning and health. ASCD.

Australian Government Department of Education (ADGE). (2023). My Time, Our Place - Framework for school age care in Australia V2.0.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2020). Australia’s children. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Bae, S. H. (2019). Concepts, models, and research of extended education. International Journal for Research on Extended Education, 6(2–2018), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.3224/ijree.v6i2.06

Bae, S. H., & Kanefuji, F. (2018). A comparison of the afterschool programs of Korea and Japan: From the institutional and ecological perspectives. International Journal for Research on Extended Education, 6(1–2018), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.3224/ijree.v6i1.04

Bazyk, S., & Bazyk, J. (2009). Meaning of occupation-based groups for low-income urban youths attending after-school care. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(1), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.63.1.69

Cartmel, J. (2019). School age care services in Australia. International Journal for Research on Extended Education, 7(1–2019), 114–120. https://doi.org/10.3224/ijree.v7i1.09

Cartmel, J., & Brannelly, K. (2016). A framework for developing the knowledge and competencies of the outside school hours services workforce. International Journal for Research on Extended Education, 4(2), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.3224/ijree.v4i2.25779

Cartmel, J., Brannelly, K., Phillips, A., & Hurst, B. (2020). Professional standards for after school hours care in Australia. Children and Youth Services Review. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105610

Department of Education Employment and Workplace Relations. (2011). My Time, Our Place—Framework for school age care in Australia (1st ed.). Australian Government. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2018-05/my_time_our_place_framework_for_school_age_care_in_australia_0.pdf

Durlak, J. A. & Weissberg, R. P. (2007). The impact of after-school programs that promote personal and social skills. Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., & Pachan, M. (2010). A meta-analysis of after-school programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45(3–4), 294–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-010-9300-6

Fettig, A., Cook, A. L., Morizio, L., Gould, K., & Brodsky, L. (2018). Using dialogic reading strategies to promote social-emotional skills for young students: An exploratory case study in an after-school program. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 16(4), 436–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X18804848

Fischer, N., Theis, D., & Züchner, I. (2014). Narrowing the gap? The role of all-day schools in reducing educational inequality in Germany. International Journal for Research on Extended Education, 2, 79–96.

Gooding, L. F. (2010). The effect of a music therapy-based social skills training program on social competence in children and adolescents with social skills deficits. Doctoral Thesis, The Florida State University, UMI Dissertation Publishing.

Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fabregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M. P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M. C., & Vedel, I. (2019). Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: a modified e-Delphi study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.03.008

Hong, Q., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M. P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., Rousseau, M. C., & Vedel, I. (2018). Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT): User guide. McGill University.

Klerfelt, A., & Haglund, B. (2014). Presentation of research on school-age educare in Sweden. International Journal for Research on Extended Education, 2, 45–62.

Klerfelt, A., & Stecher, L. (2018). Swedish school-age educare centres and German all-day schools—a bi-national comparison of two prototypes of extended education. International Journal for Research on Extended Education, 6(1), 49–65. https://doi.org/10.3224/ijree.v6i1.05

Kumschick, I. R., Beck, L., Eid, M., Witte, G., Klann-Delius, G., Heuser, I., Steinlein, R., & Menninghaus, W. (2014). READING and FEELING: The effects of a literature-based intervention designed to increase emotional competence in second and third graders. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01448

Lawrence, D., Johnson, S., Hafekost, J., Boterhoven De Haan, K., Sawyer, M., Ainley, J., & Zubrick, S. R. (2015). The mental health of children and adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing.

Malone, H. J. (2017). The growing out-of-school time field: Past, present, and future. Information Age Publishing Inc.

Marques de Miranda, D., da Silva Athanasio, B., Sena Oliveira, A. C., & Simoes-e-silva, A. C. (2020). How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101845

Milton, A. C., Mengesha, Z., Ballesteros, K., McClean, T., Hartog, S., Bray-Rudkin, L., Ngo, C., & Hickie, I. (2023). Supporting children's social connection and well-being in school-age care: Mixed methods evaluation of the Connect, Promote, and Protect Program. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting, 6, e44928. https://doi.org/10.2196/44928

Minney, D., Garcia, J., Altobelli, J., Perez-Brena, N., & Blunk, E. (2019). Social-emotional learning and evaluation in after-school care: A working model. Journal of Youth Development, 14(3), 130–145. https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2019.660

Noam, G. G., & Triggs, B. B. (2018). Expanded learning: A thought piece about terminology, typology, and transformation. International Journal for Research on Extended Education, 6(2), 164–174. https://doi.org/10.3224/ijree.v6i2.07

OECD Family Database. (2022). Out-of-school-hours services (Issue March).

Pace, R., Pluye, P., Bartlett, G., Macaulay, A. C., Salsberg, J., Jagosh, J., & Seller, R. (2011). Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. International Journal of Nursing Studies. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. The BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Pluye, P., Gagnon, M. P., Griffiths, F., & Johnson-Lafleur, J. (2009). A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in Mixed Studies Reviews. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(4), 529–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.009

Polanczyk, G. V., Salum, G. A., Sugaya, L. S., Caye, A., & Rohde, L. A. (2015). Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 56(3), 345–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12381

Rider, E. A., Ansari, E., Varrin, P. H., & Sparrow, J. (2021). Mental health and wellbeing of children and adolescents during the covid-19 pandemic. The BMJ, 374(n1730), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1730

Siddiqui, N., Gorard, S., & See, B. H. (2019). Can learning beyond the classroom impact on social responsibility and academic attainment? An evaluation of the Children’s University youth social action programme. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 61, 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2019.03.004

Social Research Centre. (2022). 2021 ECEC NWC National Report.

Stecher, L. (2019). Extended Education—Some considerations on a growing research field. International Journal for Research on Extended Education, 6(2–2018), 144–152. https://doi.org/10.3224/ijree.v6i2.05

The Joanna Briggs Institute. (2014). Supporting document for the Joanna Briggs Institute levels of evidence and grades of recommendation.

The Scottish Government. (2019). Out of school care in Scotland: Draft framework 2019.

White, A. M., Akiva, T., Colvin, S., & Li, J. (2022). Integrating social and emotional learning: Creating space for afterschool educator expertise. AERA Open, 8(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584221101546

World Health Organization. (2022). Mental health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response

Acknowledgements

I, Sarah Murray, as the lead author and manuscript guarantor, affirm the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the systematic review being reported. Further, no important details have been omitted, and any discrepancies from the review as planned have been explained.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This review was conducted as part of the first authors PhD project for which the University of Southern Queensland has awarded a Research Training Program stipend.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception, material preparation, data collection, data extraction, analysis, and drafting of the manuscript were performed by Sarah Murray. Study conception and design, critical revisions, and contributions to drafting were performed by Sonja March and Yosheen Pillay. Data extraction and review was performed by Emma-Leigh Senyard.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The data from this study did not include human participants in any way and so ethical approval was not needed.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Murray, S., March, S., Pillay, Y. et al. A Systematic Literature Review of Strategies Implemented in Extended Education Settings to Address Children’s Mental Health and Wellbeing. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-024-00494-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-024-00494-3