Abstract

Background

Social validity in the field of applied behaviour analysis is the measurement of the social significance of goals, the social appropriateness of procedures, and the social importance of the effects of a treatment. There is a paucity of rigorous research on social validity measurement as it relates to feeding treatment.

Objective

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review aiming to identify the gaps in and assess the current state of the science regarding comprehensive social validity measurement of paediatric feeding treatment.

Method

We conducted a systematic review following PRISMA guidelines using four ProQuest databases.

Results

The systematic review resulted in the identification of 26 eligible articles reporting findings related to social validity post-intensive treatment or describing new measurement systems that could be used to assess social validity more comprehensively. Collectively, caregivers rated behaviour-analytic treatments high in social validity and treatments were highly effective. Caregivers reported increased broader quality of life and lasting positive impacts, decreased stress, and lack of negative effects.

Conclusion

In the context of these results, we discuss behaviour-analytic feeding treatment within social validity’s comprehensive definition. We identify additional data-based research needs in this area and provide recommendations to spur new investigations. Social validity measurement requires refinement to further inform the standard of care. Paediatric feeding expertise and competency are crucial in navigating social validity considerations. Accurate dissemination is needed to increase earlier access to effective feeding treatment for families and specialised training for professionals to promote data-based and individualised decision-making in this vital area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In 1978, Montrose Wolf published a seminal article in the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis (JABA) introducing the concept and definition of social validity to behaviour analysts. In the article, Wolf emphasised social importance as “the heart” of applied behaviour analysis. The comprehensive definition of social validity included considerations for:

-

1.

Social significance of the goals (e.g., Are the goals important to society?),

-

2.

Social appropriateness of the procedures (e.g., Do the ends justify the means? Do consumers consider the treatment procedures acceptable? Are the procedures ethical, cost-effective, and practical?), and

-

3.

Social importance of the effects (e.g., Are consumers satisfied with all of the results, including any unpredicted outcomes? Was the intervention helpful? Did the intervention resolve the primary concerns?).

Kazdin (1977) categorised two primary methods of measuring social validity that included subjective evaluation and social (normative) comparisons. He emphasised the importance of evaluating the ease of treatment implementation, and identifying whether consumers (i.e., caregivers) continue to use the treatment or would recommend it to others (Kazdin, 2014). Additional considerations throughout the scientific literature include whether the treatment is predictive of good procedural integrity, reasonable for the consumer (i.e., child and their caregiver), minimally disruptive to family routines, or has relevant and significant social impacts (e.g., proximal, intermediate, distal effects; see Ferguson et al., 2019; Schwartz & Baer, 1991). Maintenance and sustainability may be two of the most critical social validity measures because the variables described, such as ease of implementation and level of disruption, will impact whether treatment effects will be long lasting (Kennedy, 1992).

Although the concept of social validity was defined 45 years ago and has since been assessed across numerous studies, Ferguson et al. (2019) found only 12% of authors reported assessing social validity across studies in the Journal of Applied Behaviour Analysis, with most of the focus on the procedures (85%) rather than other relevant areas of social validity (i.e., goals, effects). Fortunately, the reporting of social validity in behavioural journals is increasing (Huntington et al., 2023), but the same concerns regarding the limited scope of social validity measurement remain.

In paediatric feeding disorders treatment, Taylor and Taylor (2023) conducted a recent review of reporting processes and outcomes and similarly found only 29% of studies reported findings on social validity. A paediatric feeding disorder is exhibited by a disturbance in oral intake associated with medical, nutritional, feeding skill, and/or psychosocial dysfunction (Goday et al., 2019). Children with feeding disorders often engage in high levels of refusal behaviour at mealtimes, herein referred to as inappropriate mealtime behaviour, that can lead to devastating negative impacts without intervention (e.g., need for surgical intervention and placement of gastrostomy-tube feedings). Effective treatment for paediatric feeding disorders should involve a multidisciplinary approach (e.g., collaboration among specialty providers) with behavioural intervention being the most frequently documented and well-supported treatment (Sharp et al., 2017). One major component of effective behavioural intervention is to identify the responses that follow a child’s inappropriate mealtime behaviour, such that the child’s environment can then be arranged to increase the likelihood the child will engage in safe and efficient consumption instead of refusal behaviours.

Borrero et al. (2010) used descriptive analyses to identify the most common caregiver responses to child inappropriate mealtime behaviour (behaviour that interferes with acceptance and consumption, such as head turns or pushing food away). They found that caregivers most often ended meals by removing bites and drinks or provided attention in the form of coaxing and reprimands following inappropriate mealtime behaviour. Thus, it is not surprising that for most children with feeding disorders, inappropriate mealtime behaviour is identified to be maintained by social negative reinforcement, in the form of escape from bites and drinks (Saini et al., 2022), akin to the common finding that pica is maintained by automatic reinforcement (e.g., Hagopian et al., 2011; Piazza et al., 1996; Ruckle et al., 2022). Even if inappropriate mealtime behaviour is multiply-maintained, studies have demonstrated that differential reinforcement (e.g., providing a preferred item following consumption and not providing the preferred item following disruption) is often insufficient without escape extinction (i.e., continuing to present the food or drink despite inappropriate mealtime behaviour; Patel et al., 2002; Piazza et al., 2003; Reed et al., 2004). Although highly effective, escape extinction may temporarily produce undesirable side effects (e.g., bursts in challenging behaviour). However, concerns raised about extinction bursts in feeding do not always correspond to available data (Engler et al., 2023; Woods & Borrero, 2019).

Further, the discussion on behaviour-analytic assessment and treatment of paediatric feeding disorders (i.e., feeding) in the context of social validity has focused primarily on potential undesirable side effects of more commonly used interventions (e.g., escape extinction). Unfortunately, there has been less focus regarding considerations of goal importance, effectiveness and appropriateness of procedures, and the associated meaningful outcomes. Additionally, some of the research in this area has not included the specific target population or treatment cases, but involved simulated scenarios with graduate students or fictional vignettes (e.g., Vazquez et al., 2019). Given the health risk and impact on child development, improved social validity measurement may allow greater partnership with caregivers and real-time procedural modifications to improve effectiveness and adherence beyond narrow discharge satisfaction scales.

As differences in opinions may exist regarding treatments and which may be least intrusive or most effective, social validity becomes an increasingly relevant topic. Ultimately, practitioners should keep the child and the child’s caregivers and family at the forefront of the treatment-planning and decision-making process. Indeed, there are many elements that should contribute to treatment development. For example, the practitioner must possess the necessary training, resources, and experience and ensure they practice within their scope of competence. The practitioner should also ensure that they are connected to multidisciplinary teams (e.g., medical providers, registered dietitian, professional with expertise in paediatric swallow safety) to ensure the child’s safety, medical appropriateness, and to seek appropriate guidance on treatment options. The practitioner should ensure the physical space is amenable to the types of goals and treatments that might be necessary or appropriate. Of similar importance researchers should focus on methods for improving and refining social validity measurement to identify objective tools for assessing the appropriateness, acceptability, and significance of the goals, treatment, and procedures.

Thus, the purpose of the current paper was to conduct a systematic review of the literature on social validity measurement and the behaviour-analytic treatment of paediatric feeding disorders (PFD). In addition, we more intensively reviewed several recent studies on social validity measurement to provide readers with recommendations for goals, strategies, and resources to incorporate into future research and practice. Finally, we sought to synthesise the findings into a comprehensive framework using the original definition for social validity described by Wolf (1978).

Method

The authors conducted a systematic review of the literature according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA; Page et al., 2021) guidelines. We used four literature databases to conduct the search: PsycINFO, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science (ProQuest search engines), and used all combinations of the terms “pediatric/paediatric feeding,” with “social validity,” “acceptability,” or “satisfaction.” We restricted the search to peer-reviewed articles involving human subjects (search period up to October 2023). Eligibility criteria were that the article (a) reported on paediatric feeding disorders, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), or food selectivity and (b) reported on the social significance of goals, procedures, and/or effects of behavioural intervention with direct-observation treatment data. The first author takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The authors report no conflicts of interest or funding sources. The PRISMA flow chart is depicted in Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

The initial search returned 85 articles, 51 of which were duplicates. The first and second author screened the remaining 34 articles independently, resulting in the exclusion of 13 articles. Specifically, articles met exclusion criteria when they (a) reported on other eating disorders (e.g., pica); (b) focused on paediatric feeding assessment, caregiver training of behavioural feeding protocols, or non-behavioural intervention; (c) only used rating scales as dependent measures, (d) assessed curricula or parent-training programs instead of individualised behavioural intervention of a feeding disorder; or (e) focused on barriers to care and provision of services (e.g., via telehealth) instead of the delivery of behavioural intervention and results.

The 21 remaining journal articles were assessed for eligibility by the first and second author independently. Two of these articles were systematic reviews (Rubio et al., 2020a, b; Taylor et al., 2019a, b). Seven additional studies were sourced from the reference lists of those reviews and the reviews were excluded. Thus, 26 articles met inclusion criteria. The first author reviewed the 26 eligible journal articles and extracted the following from each treatment study: (a) service setting; (b) service intensity (i.e., frequency and duration of services); (c) number of cases reported (i.e., N); (d) social validity measures used; (e) timing of social validity assessment; and (f) the social validity results for each participant.

The second author conducted an interrater reliability check on the reference selection process by searching for the target studies in the references resulting from the original search in PsycINFO and PubMed (n = 18) and confirming correspondence. Agreements occurred when the first and second author identified or did not identify the same article using the specified keyword search. Disagreements occurred when one article was identified by the first or second author and not identified by the other author using the same keyword search. The second author summed the agreements (n = 18) and divided the sum of agreements by the sum of agreements and disagreements (n = 18) and converted the ratio to a percentage to obtain the interobserver agreement coefficient. The articles identified by the second author corresponded with the articles identified by the first author for 100% of the articles reviewed. The second author also conducted interrater reliability checks for the data extraction process by extracting the: (a) service setting; (b) service intensity (i.e., frequency and duration of services); (c) number of cases reported (i.e., N); (d) social validity measures used; (e) timing of social validity assessment; and (f) the social validity results for each participant of approximately 12% of the included data sets (n = 3) identified using random selection. Agreements occurred when the first and second author identified or did not identify the same data from the articles. Disagreements occurred when relevant data was identified by the first or second author and not identified by the other author. The data extracted by the second author corresponded with the data extracted by the first author for 100% of the 3 randomly selected data sets.

Results

Table 1 presents the studies identified. First, we will review treatment studies that reported survey or questionnaire tools to assess caregiver acceptability, satisfaction, and/or preference for various behavioural treatments. No direct, objective social validity measurement approaches were reported across 21 studies ranging in year of publication from 1996 to 2021. All studies reported social validity findings associated with intensive feeding treatment. Eleven studies (52%) were from medical school/hospital settings, one was either at home (one participant) or a university clinic (two participants), and the remaining nine were conducted in intensive home-based programmes. Researchers used well-established empirically supported treatments such as differential reinforcement and escape extinction (Kerwin, 1999; Volkert & Piazza, 2012). All but one study (Taylor et al., 2019a, b) included only caregivers as respondents, lacking the assessment of social validity from other key stakeholders (e.g., teachers, physicians, therapists) or the child who had received treatment.

Only three studies assessed variables related to social validity that examined caregiver wellbeing before treatment. More specific, researchers from these two studies compared levels of caregiver stress before and after treatment and found that caregiver stress was lower after their child received behavioural intervention of their feeding disorders (Greer et al., 2008; Taylor et al., 2019a, b). Similarly, Binnendyk and Lucyshyn (2009) found improved quality of life ratings from baseline to follow-up. Most studies (n = 15) assessed social validity only once directly after the behavioural intervention programme had ended. It was often unclear across studies whether social validity surveys (i.e., measurements of caregiver acceptability, satisfaction, preferences) were administered at discharge, after the child had completed the treatment evaluation, or after caregivers had undergone training. Two exceptions (Ahearn et al., 1996, 2001) examined caregiver preference between treatment components before the reversal phase during a treatment evaluation (i.e., after the researchers had attained stability in responding during the initial treatment phase). Additionally, one study (Borrero et al., 2013) allowed caregiver choice of treatment components at completion of the treatment evaluation but before caregiver training had occurred. Hansen and Andersen (2020) measured social validity halfway through the programme, and Binnendyk and Lucyshyn (2009) measured social validity at two different points during the programme. Two of the reviewed studies assessed social validity after the children had transitioned to follow-up services to assess for maintenance (i.e., 2 weeks or 1 month; Flanagan et al., 2021; Sharp et al., 2016). Only one study (Binnendyk & Lucyshyn, 2009) assessed long-term social validity beyond 1-mo post-intensive treatment, although a few of the studies included data or discussion of caregiver adherence to treatment protocols.

Most of the reviewed studies (n = 18; 86%) used Likert-type scales to assess caregiver acceptability and satisfaction, with only a subset of the studies (n = 3; 14%) including a measure of caregiver choice among treatment options (Ahearn et al., 1996, 2001; Borrero et al., 2013). All but one study (Taylor et al., 2019a, b; 7-point scale) used a 5-point Likert-type scale. Not all studies included references for the types of surveys or measures they used. Eleven studies (52%) provided specific citations for the various tools they included. Five studies provided a complete list of the questions that were included in caregiver-administered surveys, but did not provide information on item generation methods (i.e., how they developed the questions) or references. Nine studies (43%) referenced Hoch et al. (1994), who provided the full list of questions but did not report item generation methods. With the exception of Hoch et al. (1994) and Taylor et al., (2019a, b), the scales used were not developed specifically for paediatric feeding treatment (e.g., the Intervention Rating Profile [IRP] was developed for teachers and classroom interventions; Martens et al., 1985; Witt & Elliott, 1985).

The scales administered across the studies all lacked clear psychometrics or scoring conventions, although most studies reported overall average across items or participants. Studies reported overall total scores and not subscale scores on separate dimensions of social validity. Exceptions were Taylor et al., (2019a, b), caregiver stress, and quality of life studies. Only four studies reported scores on individual items from the questionnaires, and only five studies provided qualitative or open-ended comment details. Researchers often assessed satisfaction and acceptability of the intervention programme as a whole, but did not assess the social validity of the goals or broader effects. No studies compared different treatment approaches to determine whether some approaches have greater social validity than others, especially to compare procedures that might be considered less intrusive (e.g., differential reinforcement) to those considered more intrusive (e.g., escape extinction). The five studies reviewed in Rubio et al., (2020a, b) on potentially invasive procedures such as physical guidance were an exception. Except for caregiver stress studies and Binnendyk and Lucyshyn (2009), none of the reviewed studies used broader measures to assess the child, caregiver’s, or family’s quality of life. Two studies reported that not all participants returned written surveys, but that anecdotally, caregivers had reported high satisfaction and acceptability verbally and via email (Taylor & Haberlin, 2020; Taylor, 2020).

On average, all caregiver-provided ratings across studies were high and positive (above 4). None of the caregivers across studies rated the treatments negatively. In several studies, caregivers preferred a more invasive procedure (i.e., physical guidance) to a less intrusive treatment (i.e., nonremoval alone) and rated invasive procedures with high acceptability (see review by Rubio et al., 2020a, b).

In the following section, we provide a more in-depth review of recent studies that included direct and objective measures of social validity. Studies published in the last few years have focused on refining social validity measurement tools to evaluate more direct and objective outcomes, with a specific focus on refining social validity measurement and unique contributions to the literature. The years of publication of these four studies ranged exclusively from 2021 to 2023.

Anderson et al. (2021) introduced a novel approach to assessment development by asking caregivers, instead of practitioners, to help create survey content. Upon programme discharge, the researchers conducted a semi-structured interview with caregivers of seven children with tube dependency receiving in-home services. At admission, children ranged in age from 3 to 14 years (mean of 8.4 years) and had been dependent on tube feedings for a mean of 4.3 years (range, 1.5 to 6.3). Anderson et al. analysed the caregiver interview transcripts using thematic and textual analyses. Thematic analysis is a qualitative approach to identifying patterns or themes in the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). In comparison, textual analysis is a quantitative method to extract meaning across language samples (Landauer et al., 1998). This process led to surveys based on each method, that included items of importance to caregivers. One notable strength was that the researchers asked a separate, blind assessor not involved in feeding treatment to conduct the interviews, analyses, and scale development study. The researchers included examinations of reliability, by assessing agreement on theme generation between coders. Content validity was also evaluated via caregiver measures of understanding and relevance of the questionnaire items.

This process also identified novel content not yet covered in previous social validity surveys, such as benefits of behavioural feeding treatment beyond eating, spiritual/cultural beliefs, and the importance of the provider “believing” treatment would work. Identified themes from caregiver interviews included: oral eating as a milestone, satisfaction-expectation trade-off, benefits outweighing negatives, funding/availability of treatment, gradual progress, and communication with the clinician. Social validity ratings were high (out of 7, 6.6 for thematic and 5.1 for textual). Caregivers also rated the questions derived from both methods (thematic or textual analyses) as relevant and understandable (all above 90%). This study could have important contributions and implications for social validity because these new methods could be applied by others across a wide variety of other populations and areas of applied behaviour analysis outside of paediatric feeding.

Taylor and Taylor (2022a) was the first study, to our knowledge, to analyse social validity data comprehensively across participant characteristics, goals, treatment processes, components, and outcomes. The sample included 32 children with severe paediatric feeding disorders and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). The majority of participants were diagnosed with developmental disabilities and had previously failed treatments for their feeding difficulties. Participants ranged in age from 2 to 13 years (M = 6 years). Taylor and Taylor analysed the relationships between caregiver social validity ratings and a variety of variables such as direct meal observation data, presumed complexity/intrusiveness of the components, number of goals, time to effect, and variables related to caregiver implementation and support. The authors examined open-ended comments and individual questionnaire items with lower ratings. Interobserver agreement and procedural integrity data were examined for 41% of the sample for an average of 32% of sessions. In addition, 88% of the sample had treatment evaluations that demonstrated experimental control via single-case design. Treatment outcomes were positive for all participants in the sample, with clinically significant levels of increases in consumption, food variety, feeding skills, and age-appropriate eating. Results maintained to long-term follow-up of an average of 2 years (caregiver rating M = 4.24 out of 5).

Social validity ratings (out of 5) were high for satisfaction (M = 4.9, SD = 0.2) and acceptability (M = 4.8, SD = 0.3), and open-ended comments were positive. The authors conducted statistical analyses and overall, found no significant associations between any variables and social validity ratings due to ceiling effects (restricted range; low variability), with one exception of programme duration due to one child who met goals early (i.e., in 6 days).

Ultimately, these findings still underlay a significant positive tenet: evidence-based intensive paediatric feeding treatments were highly effective and efficient, and associated with high caregiver acceptability ratings. These findings were also not surprising as they matched previous research from structured and/or intensive clinical settings (Hoch et al., 1994; Hoch et al., 2001; Laud et al., 2009; Rubio et al., 2020a, b; Sharp et al., 2017; Taylor et al., 2017; Woods & Borrero, 2019).

To our knowledge, Taylor and Taylor (2022b) was the second report (following Taylor & Taylor, 2022a) to examine social validity in a data-based manner in paediatric feeding across time and components. The authors provided caregivers with the opportunity to rate a broad range of potential treatment procedures separately both before and after treatment. Questions covered all three of the major components of the definition of social validity (goals, effects, procedures) and asked caregivers to report on the balance between time to effectiveness and minimising potential undesirable side effects. Questions also included those related to culture and provided an opportunity for caregivers to leave open-ended comments.

Regarding the importance of the goal of feeding, caregivers unanimously rated this goal at the highest rating of 7 out of 7. These high ratings are not surprising, given the caregivers were seeking treatment for their child’s feeding difficulties. However, the ratings show that this particular goal was of great value and significance for the individuals receiving services. Caregivers also preferred treatment to be effective and quick, over minimising side effects, and this rating was higher post-treatment (M = 6.5) except for one parent who remained consistent at 4. Overall, social validity ratings were high (M = 6.8 post-treatment) for the following target categories of interventions (a) attention; (b) tangibles; and (c) escape. Social validity ratings increased by discharge for all interventions except for contingent access to electronics and noncontingent access to various tangible items. In these cases, caregivers provided the lowest ratings despite presumably being the least “intrusive” options. Ratings were high for presumed “intrusive” treatments for acceptance and swallowing (e.g., depositing bites using an infant gum brush), and for escape extinction procedures. More specific, the escape extinction procedures included nonremoval of the utensil (continuing to present the bite or drink to the child’s lips despite inappropriate mealtime behaviour) and re-presentation of expulsion (immediately replacing a bite or drink following the child’s spitting or allowing food/liquid to fall from the mouth).

The findings from Taylor and Taylor (2022b) were consistent with findings reviewed in Rubio et al. (2020a, b). Open-ended comments aligned with the quantitative data. No caregivers provided comments regarding culture. Caregivers provided more open-ended comments on the initial survey (pre-treatment) than subsequent surveys. Taylor (2022) employed these survey methods to assess social validity during development of medication administration procedures for two children during intensive paediatric feeding intervention.

Phipps et al. (2022a, b) developed direct-observation measures of child indices of happiness and unhappiness and recorded those indices during escape extinction treatment of inappropriate mealtime behaviour with and without mitigation procedures (positive reinforcement) for four children diagnosed with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). All children in Phipps et al. relied on gastrostomy-tube feedings to meet their nutritional and growth needs and had a history of not responding to less intensive approaches to feeding therapy. Children participated in five, 30- to 40-min meals per day, 5 days per week, to work toward their goals of becoming an age- or developmentally typical feeder. To validate the definitions for happiness and unhappiness, the authors compared child data for each dependent variable with blind ratings from other relevant disciplines (i.e., paediatric dental residents and speech language pathologists). Interobserver agreement for indices of happiness and unhappiness each averaged at 99%. Phipps et al. found that happiness remained the same or increased following treatment in most cases. Unhappiness decreased quickly (to zero in two to eight sessions), was brief (20–80 min), and caregiver treatment acceptability ratings were high. Extinction bursts occurred in only one of the four cases (25%), and inappropriate mealtime behaviour decreased rapidly across all children in the study.

Phipps et al. also compared extinction-based feeding treatment (i.e., nonremoval of the spoon) with and without noncontingent reinforcement (NCR; in the form of continuous interaction with toys and the feeder) in an alternating treatments design and observed potential mitigation of indices of unhappiness with added reinforcement, as well as more robust treatment outcomes (e.g., increases in acceptance) for some children. However, the addition of NCR did not reliably evoke indices of happiness for all children. Caregivers provided treatment acceptability ratings at three points in the study, after observing: at least one session of baseline, initial treatment with and without NCR, and the final treatment with and without NCR in which child acceptance was at 100%. Social validity ratings remained high despite temporary increases in negative emotional responding (e.g., crying) or inappropriate mealtime behaviour. When given the choice, caregivers opted not to continue NCR during treatment with solid foods and chose to include NCR during treatment with liquids. Caregivers reported that it was more practical, long-term, to only include NCR during shorter meals with liquids and that they did not want their child to need toys or excessive attention during all meals at home.

Discussion

In general, caregiver reports of and data for social validity across behaviour-analytic function-based treatment studies have demonstrated positive interpretations of treatment (i.e., high social validity ratings; Allison et al., 2012; Bui et al., 2013; Hoch et al., 1994; Hoch et al., 2001; Laud et al., 2009; Najdowski et al., 2010; Patel et al., 2022; Rubio et al., 2020a, b; Sharp et al., 2017; Taylor et al., 2017, 2020; Woods & Borrero, 2019). These studies are commendable, being in the minority of the literature base reporting social validity considerations. However, social validity measurement methods warrant refining, and previous studies have focused primarily on only one aspect of the definition of social validity (e.g., undesirable side effects of a procedure) or on caregiver satisfaction and acceptability of the treatment overall post-treatment.

Other limitations of previous studies that primarily used survey tools, rating scales, or questionnaires are that (a) the tools were often administered after treatment had already ended and with only a subset of key stakeholders (e.g., child’s primary parents); (b) the scales used were often originally designed for an alternative purpose, rather than to assess the social validity of interventions for paediatric feeding disorders; (c) scales mainly focused on behaviour reduction or the use of intrusive procedures instead of a more comprehensive analysis of social validity, such as types of goals, treatment effects, and broader outcomes; (d) many are subjective and lacking opportunities for participants to provide answers to open-ended questions; and (e) there are not always thorough descriptions for item generation methods or how the tools were developed. Finally, many studies that have only used scales or surveys have not gathered long-term follow-up measures to determine whether progress maintained over time and resulted in lasting meaningful changes for the child and family (Andersen et al., 2024).

Several of the more recent studies expanded social validity measurement into all three areas of Wolf’s definition and addressed important gaps in the literature. Below, we provide a more comprehensive overview and discussion of a subset of recent studies and advancements focused on measurement of social validity to highlight areas for future research and to provide recommendations for practice. We present this overview according to Wolf’s social validity definition, that includes an evaluation of goals, procedures, and treatment effects.

Feeding Treatment within the Comprehensive Definition of Social Validity

Social Significance of Goals

Taylor and Taylor (2022b) found that caregivers unanimously rated the importance of targeting feeding difficulties with effective treatment at the highest rating of 7 out of 7. In Taylor and Taylor (2022a), via open-ended comments, caregivers reported treatment was “life-changing” for the child’s long-term future and the family. It is not surprising that caregivers seeking effective treatment for their child’s feeding difficulties rate the goal of improved feeding with high importance; however, gathering such data is a step toward acknowledging how the goals of using applied behaviour analysis to target feeding difficulties are important to society. With the importance of the goal established, researchers can conduct a more thorough evaluation of what types of feeding goals are most socially significant. For example, it is likely important across cultures for children to have the ability to consume necessary medications orally, and to avoid or eliminate the need for gastrostomy-tube dependence. However, some caregivers may prefer to have their child continue to rely on gastrostomy-tube feedings for most of their intake or medications so that they can focus primarily on targeting the child’s independent feeding (i.e., child consuming small amounts on their own during mealtimes instead of being fed a full portion by their caregiver).

Ultimately, practitioners should work closely with caregivers and/or the child (when appropriate) to determine the most appropriate and individualised goals. Many factors contribute to the development of a child’s feeding goals, such as health and medical status, oral-motor skill deficits or physical limitations, and the family’s cultural or religious practices. For one child, it could be most important to eliminate supplemental feedings so the child can develop key skills to become an age-typical oral feeder. For another child, goals may be focused on reducing inappropriate mealtime behaviour to introduce greater diet variety and address nutritional deficiencies or refining of oral-motor skills (e.g., teaching chewing skills). The best way to determine whether the goals are socially significant is to include the family in the goal-setting process, to evaluate progress toward goal attainment throughout the admission, and then to identify the appropriate measures and procedures for monitoring and achieving progress.

Timing is also a crucial variable in terms of goal setting, and identifying when it is important to intervene on feeding difficulties. Authors providing direct services in family homes internationally described increased knowledge and experience of the scope of negative impacts on child and family lives prior to effective treatment (Taylor & Taylor, 2021, p. 20 Table 1). In many cases, it could be vital to intervene on feeding difficulties as early as possible (Van Houten et al., 1988). Several significant examples of negative impact that can result from prolonged exposure to feeding difficulties include problems with toileting, sleep, nutrition, growth, immune system, and dental hygiene. A survey of caregivers of children with feeding disorders revealed that even when their concerns were reported to medical professionals, reports did not always lead to effective treatment and that ultimately receiving effective treatment was a “stroke of luck” (Lamm et al., 2022). Consistent with prior research, in Taylor and Taylor (2022b), caregivers reported placing value on rapid effects. Further, Anderson et al., (2021) found that caregivers directly emphasised the importance of availability and funding of treatment.

“Picky” or selective eating is common for children during typical development (e.g., between 18 months to 3 years). These “phases” or challenges can be minor, transient, and resolve over time with practice and exposure (Babbitt et al., 1994). Children with feeding disorders, however, may not “grow out of” eating challenges independent of intervention. When these more pervasive feeding challenges first emerge, caregivers may initially struggle to ensure their child gets sufficient calories, nutrition, and hydration. Poor nutrition and inadequate calorie consumption can not only lead to growth challenges or health concerns but can impact brain development and place the child at risk for learning or behaviour difficulties (Nyaradi et al., 2013; Rosales et al., 2009). Primary care physicians (e.g., paediatricians) might recommend that caregivers wait to see if their child’s feeding difficulties diminish over time with regular practice, just as “picky” eating can resolve with typically developing children. Peterson et al. (2019) conducted a small randomised controlled trial to determine whether the feeding difficulties of three children with ASD would resolve independent of treatment. Unfortunately, after 6 months, none of the children took bites of targeted foods or changed their diets at home until they began behaviour-analytic treatment. It could be that a longer waiting period (e.g., 1–2 years) would have resulted in more change in the children’s diet independent of treatment, but some children may not have that much time to wait for effective treatment (e.g., impending tube placement, chronic dehydration). In addition, several other studies have shown that without treatment, feeding difficulties will likely stay the same or worsen over time (Dahl, 1987; Dahl & Kristiansson, 1987; Dahl & Sundelin, 1992).

During periods of critical development (e.g., ages 1 to 5), feeding disorders can also result in the child missing important practice. Without regular practice, the child may miss opportunities to develop appropriate feeding skills, which can then make eating and drinking more effortful or unsafe. For example, if a child has not been exposed to higher food textures due to refusal, the child may not develop appropriate chewing and mastication skills. It may then be important to build strength, stamina, and coordination with higher textured foods through repeated practice for the child to become a safe oral feeder.

If children miss important learning and practicing opportunities, these skills may become more challenging to teach as the child ages, especially with limited treatment settings and the child’s life complexity (e.g., school, extracurricular activities). If practitioners intervene at an earlier age, they could capitalise on a shorter history of refusal behaviour which could lead to a faster treatment effect. In addition, intervening at earlier ages could provide the child with more opportunity to hone important oral-motor skills. Finally, caregivers may expend great amounts of stress, time, money, and effort on ineffective treatments before identifying effective, evidence-based treatment. Caregivers of children with feeding disorders experience depression and anxiety, especially after years of challenging or stressful meals with their child, concern that their child is not eating enough to grow, daily management of supplemental diets and feedings, and frequent medical visits (Auslander et al., 2003; Garro et al., 2005). Over time, feeding problems may affect family functioning and quality of life; therefore, early intervention can be important for the whole family.

Social Appropriateness of Procedures

Anderson et al. (2021) determined, based on caregiver interviews, that often, benefits of effective treatment outweigh many possible, temporary negative outcomes for caregivers. Not only in Anderson et al., but across the social validity assessments accessed in recent studies, caregivers reported high social validity ratings across a wide range of procedures, including those that might be considered as, “intrusive,” which is consistent with prior research (Rubio et al., 2020a, b).

One strength of behaviour-analytic feeding treatment is that there is a wide array of specialised and empirically supported interventions that are effective at improving feeding behaviour. Therefore, caregivers have many options to choose from in terms of which treatment components may be most comfortable and appropriate for their child. Practitioners should explain the various treatment options that are warranted based on the child’s skills and behaviour, and based on the caregivers’ goals. Studies have identified effective treatments for reducing passive refusal (i.e., nonacceptance, not opening the mouth), inappropriate mealtime behaviour (e.g., head turns, pushing the feeder’s arm or the utensil away), expulsion (i.e., spitting or allowing food or liquid to run out of the mouth), or packing (i.e., holding food or liquid in the mouth for long durations). However, the same procedures that are warranted to address behaviours for reduction, may not be necessary or indicated to promote skill acquisition. For example, if the child engages in low levels of inappropriate mealtime behaviour, packing, and expulsion, and accepts quickly but does not use their tongue to lateralise or move bites of table-textured foods to the molars to chew before attempting to swallow, then the practitioner can explain which treatment components might be most appropriate to teach and reinforce appropriate tongue lateralisation skills (e.g., Phipps et al., 2022a, b).

Researchers have expressed caution against use of some behaviour-analytic treatments, such as escape extinction (e.g., Flanagan et al., 2021). Given that the results of basic and applied research have shown that extinction-based treatment can produce bursts (i.e., temporary increases in inappropriate mealtime behaviour) or other undesirable side effects (i.e., crying), researchers have presented concerns that children with feeding disorders could experience those same side effects during escape extinction. Woods and Borrero (2019) examined extinction bursts in behaviour-analytic treatment of paediatric feeding disorders and found that only 30% of the total examined cases demonstrated bursts. Further, bursts were brief and resolved quickly (i.e., average of 1.3 sessions, less than 10 min). Across all cases, children consumed food within the first two sessions of treatment and social validity ratings were high at 4.7 out of 5. Engler et al. (2023) extended these findings in a consecutive controlled case series study of 60 children, and also evaluated corresponding appropriate mealtime behaviour. Extinction bursts of inappropriate mealtime behaviour occurred in only 7% of datasets. Engler et al. also found that it took only three sessions of escape extinction before they observed increases in active acceptance to high, stable levels in 44% of the datasets and increases in mouth clean (i.e., swallowing or consumption) to high, stable levels in 70% of datasets. Brief bursts of negative vocalisations (e.g., crying) occurred in 70% of datasets, which is a finding that warrants further investigation in terms of whether certain strategies could help to mitigate emotional responding (e.g., application of reinforcement- or antecedent-based elements such as providing preferred items or activities and praise and interaction or making modifications more gradually).

Collectively, these data on prevalence of bursts or other extinction-induced side effects highlight that although there may be increases in challenging behaviour for a subset of children, those increases are temporary. In addition, no studies have demonstrated that temporary bursts or increases in emotional responding lead to any long-term adverse effects for the child and family. Despite temporary increases in emotional responding, caregivers may still rate the treatment as acceptable and as being in alignment with their goals of improving their child’s eating/drinking. This may especially be the case for children who have suffered from severe feeding difficulties and the negative consequences associated with that disorder for many years. That is, caregivers may discount the possibility of temporary undesirable side effects for the long-term health benefits and improved quality of life that is possible from a robust and highly effective treatment.

Many feeding studies have included antecedent strategies at the onset of treatment to reduce the aversive qualities of the mealtime and create a safe format for which to target eating and drinking. For example, antecedent strategies have included beginning treatment with smooth, uniform textures of food (e.g., pureed foods); smaller bolus sizes (e.g., 2-cc bolus of liquid in the cup); paced bite or drink presentations; non-self-feeder formats (i.e., therapists presenting bites or drinks to the child’s lips); and session time or volume caps (i.e., finishing the meal at a specified time such as 10 min or amount such as 5 bites). Often, these components are included in baseline, as elements of the total feeding procedure and not evaluated separately. Researchers should continue to evaluate the effects of these components and consider how to assess their social validity according to caregivers and child recipients. In other commonly used but non-evidenced-based feeding-intervention approaches, therapists may present food or snacks at regular textures or allow the child to lead the therapy progression and process (e.g., Peterson et al., 2016). Researchers should continue to compare these interventions and evaluate the importance of targeting food or liquid consumption in different ways (e.g., self- versus non-self-feeding; regular textures versus smooth textures; bolus comparisons), as well as the effects of child-led components, and determine their overall effectiveness and their social validity.

Studies have also demonstrated the effectiveness of more gradual intervention steps, such as demand fading that includes a stepwise task analysis for teaching individualised feeding steps sequentially (e.g., grasp spoon, lift to lips, open mouth, deposit spoon in mouth, pull bolus from spoon; Rubio et al., 2017). In addition, researchers have evaluated other antecedent-based strategies to target skill acquisition, including shaping (Phipps et al., 2022b), other stimulus or demand-fading strategies, such as empty spoon presentation practice (Kerwin et al., 1995), syringe-to-cup fading (Groff et al., 2014), or liquid-to-baby-food fading (Bachmeyer et al., 2013). To improve the acceptability of treatment, researchers have developed sound preference assessment methodology, child choice arrangements for use in treatment, and varied levels of escape extinction procedures such as exit criterion (the meal remains on the table despite inappropriate mealtime behaviour) or stationary spoon presentation where the spoon remains in position from a specified distance to the child’s lips despite inappropriate mealtime behaviour (e.g., Cooper et al., 1999; Crowley et al., 2020; Fernand et al., 2016; Kerwin et al., 1995; Taylor, 2018, 2020; Taylor et al., 2019a, b; Taylor & Taylor, 2024; Zeleny et al., 2019). Researchers and practitioners should contact the literature to identify ways in which they could tailor and individualise a child’s treatment procedures to match closely with the caregiver’s goals and the caregiver and child’s preferences.

Researchers have found behaviour-analytic feeding treatments to be robust to degradation. That is, researchers have found that treatment effects will persist even when the procedures are not implemented perfectly (Ulloa et al., 2019). More specific, Taylor and Taylor (2022a) identified high social validity ratings despite variations in caregiver implementation and across various protocol elements (e.g., number of meals fed, procedural integrity, procedural complexity). During early stages of treatment implementation and possibly elevated levels of inappropriate mealtime behaviour, the procedures may be more challenging or complex and difficult to implement. To maintain good procedural integrity, it may be essential for trained behaviour analysts to conduct the initial treatment evaluation.

Taylor and Taylor (2022a, b) also found that some procedures (e.g., physical guidance or prompting) were only necessary briefly and at the beginning of the intervention process, and caregivers did not require them in future meals. It could be a goal for treatment progressions that trained therapists use the more complex procedures initially (e.g., chin prompt with the feeder’s index finger gently resting under the child’s chin to aid the child in retaining liquid inside the mouth), but that these strategies are faded once the child’s behaviour and skills improve (e.g., child learns to retain liquid inside the mouth therefore, therapist removes chin prompt), without needing to teach caregivers the additional procedures. Thus, researchers should continue to investigate strategies for fading more complex components of feeding intervention to make the final package as simple as possible, and one that can integrate easily into the family’s routine.

During open-ended questions delivered during interviews, caregivers emphasised the importance of breaking feeding goals into smaller, more manageable starting points to allow the child to contact success quickly, and then to gradually and systematically increase feeding demands based on the child’s progress (Anderson et al., 2021). This is an important response from caregivers, given that there is now a growing body of literature in which researchers have examined strategies to individualise treatment progressions. For example, Phipps et al. (2022a, b) evaluated including noncontingent access to preferred items and continuous attention to mitigate bursts of inappropriate mealtime behaviour and indices of unhappiness. Some caregivers preferred to include noncontingent reinforcement, but only under specific conditions (i.e., short meals). Similarly, Taylor and Taylor (2022b) found that the acceptability of electronics (e.g., iPad) at mealtime was not as high as would be expected given that providing access to tangible items could mitigate undesirable side effects of treatment.

Beyond initial treatment to jump start a child’s goals for feeding, many children with feeding disorders will also require specific intervention to teach advanced skills to ensure they become safe and efficient oral feeders. Fortunately, behaviour-analytic researchers have developed tools for teaching various important advanced feeding skills. There is a growing body of literature evaluating strategies for teaching independent feeding or drinking, chewing skills (e.g., tongue lateralisation, mastication, which is a term to describe when the food is adequately chewed up before swallowing), and portion-based meal consumption (Taylor, 2024). With a behaviour-analytic technology, practitioners can individualise and tailor these treatments to address the child’s unique behaviour or skill deficits. Most treatments used to teach advanced feeding skills include reinforcement- and antecedent-based components but have not been a focus in the discussion of social validity relative to procedures that aim to reduce inappropriate mealtime behaviour. Thus, more social validity assessments are necessary for this group of procedures and treatments.

Maintenance may serve as another benefit for increasing the social validity of behaviour-analytic feeding treatments. In Taylor and Taylor (2022a), caregivers reported that children’s behaviour improvements were maintained for an average of 2.2 years following the initial study, and anecdotally reported less protocol use over time. Children may no longer need a structured treatment protocol for skills such as chewing or cup drinking once those skills are mastered. Maintenance may occur with food variety if repeated exposure (i.e., practice with a wider array of different foods over time) changes food/drink preferences or ‘liking,’ and thus, response effort (i.e., difficulty level for the child). This can also occur with gradual changes to volume of intake, texture variety, and after the child acquires more advanced feeding skills, such as correct utensil use. Additionally, meals occur multiple times per day, providing families with ample opportunities for practice. It is important to note that a positive treatment effect does not ensure caregivers will adhere to the protocol, especially if the protocol is time-consuming and resource intensive (Allen & Warzak, 2013), but acceptable modifications can be made based on caregiver feedback to prevent low adherence. Researchers could conduct periodic probe sessions without treatment or with less complex protocols or fade systematically to ensure mastery and long-term maintenance.

Given that many children with feeding difficulties are young and engage in dangerous and sometimes life-threatening behaviour (i.e., refusal to a degree that places the child at risk for failing to thrive and grow, severe dehydration, or invasive surgical procedures), it is often crucial for practitioners to place emphasis on caregiver acceptability of the treatment process. However, when possible, researchers should include measurements of child preference for various treatment options and consider how the treatment impacts the child in different ways. Measurement methods may require adaptation for the recipient’s developmental ability (e.g., communication, literacy). For example, Hanley and colleagues conducted a series of studies assessing social validity directly from treatment recipients that included a choice arrangement between treatment options (see Hanley, 2010). Hanley et al. found that child recipients demonstrated a preference for direct versus child-led teaching, contingent versus noncontingent reinforcement, and additional components (e.g., time out). The researchers discussed possible reasons for these findings (see discussion in Hanley, 2010). Other researchers have begun evaluating choice arrangements to identify which feeding treatment components children prefer (e.g., Crowley et al., 2020) and child assent during treatment targeting food selectvity (Gover et al., 2022), but more research is needed.

Social Importance of the Effects

Function-based behaviour-analytic feeding treatment is highly effective, and studies have shown that behaviour change can be rapid and substantial. In Anderson et al. (2021), caregivers emphasised a novel aspect not yet captured in earlier surveys: the importance of the practitioner “believing” the treatment would work. Caregivers have reported effective treatment provides much potential and hope given that they have “tried everything” (Taylor & Taylor, 2022a).

Taylor and Taylor (2022b) identified that caregiver’s preferred that the treatment have immediate effects over minimising the potential for undesirable side effects such as temporary increases in crying or refusal. These findings from social validity research in feeding are consistent with treatment for other challenging behaviour. For example, Owen et al. (2021) found that caregivers preferred escape extinction over other treatments that decreased problem behaviour but did not increase cooperative behaviour. Caregivers have rated punishment, presenting an aversive stimulus or removing a positive stimulus immediately following a response, as more acceptable for severe problem behaviour (Wei et al., 2021). Additionally, caregivers rated response cost, removing an individual’s access to a preferred item immediately following a response, as more acceptable than differential attention, praising appropriate behaviours and minimising reacting to inappropriate behaviours (Jones et al., 1998). Finally, Edelstein et al. (2023) found that caregiver decisions about treatment processes were most frequently based on speed of improvement and overall progress.

In open-ended responses, caregivers commented on efficiency of the behaviour-analytic treatment (e.g., “so many positive changes for 2 weeks…in such a short timeframe”) and the numerous other therapies across multiple years without contacting success (Taylor & Taylor, 2022a). The data on extinction bursts (Engler et al., 2023; Woods & Borrero, 2019) and child indices of unhappiness (Phipps et al., 2022a, b) during treatment demonstrate that undesirable responses do not occur for all children, are brief, and despite their occurrence, caregivers still provided high social validity ratings. Taylor and Taylor (2022b) also identified that caregiver preference increased by the child’s discharge after direct experience with the procedures.

Anderson et al. (2021) identified that caregivers found specific benefits of treatment beyond increased and improved eating. Collecting open-ended comments in social validity and follow-up surveys has revealed multiple novel areas for improvement and impact (e.g., benefits “flowed on” to younger sibling, improved the child’s other behaviour, their child was a “new guy”; Taylor & Taylor, 2022a). Anecdotally in clinical practice, the authors of the current study have gained knowledge of positive treatment effects by working in family homes and in the community, and conducting more frequent and direct follow-up services for longer periods (e.g., Taylor & Taylor, 2024). Caregivers have reported a wide variety of rippling positive side effects (Table 2). One common example is the ability to perform toothbrushing and oral hygiene routines without the child engaging in challenging behaviour. Caregivers have also reported many “firsts” for their child after feeding treatment such as staying at overnight camp, eating on a plane, or eating their first slice of birthday cake. Although the authors have not collected objective data on these events or confirmed that they were a direct result of feeding treatment, caregivers have reported correlation.

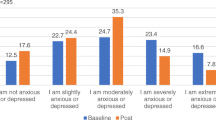

Successful treatment can also reduce caregiver stress (Andersen et al., 2024; Greer et al., 2008; Knight et al., 2019). Caregivers of children with feeding difficulties had elevated scores on worrying subscales of the Paediatric Quality of Life Scale (Simione et al., 2022). In addition, children with feeding disorders indicated statistically significant poorer quality of life than children who had a kidney transplant or liver failure (Simione et al., 2022). Caregivers in Taylor and Taylor (2022a) commented that treatment, “lifted a weight off our shoulders.” Researchers should consider obtaining measures of caregiver stress during their child’s feeding treatment process (pre-, post- and long-term follow-up; Andersen et al., 2024). Given that caregivers are responsible to carry out the treatment, it is also important to determine the effects on their behaviour, and emotional wellbeing. In clinical practice it is observed that caregivers’ anxiety lessens over time when they have fewer encounters with medical professionals and reduced fears regarding their child’s oral intake and growth.

More research is needed to better understand the child’s emotional wellbeing before, during, and after feeding treatment, as well as the effects of treatment on the child’s relationship with their caregiver. For example, Knight et al. (2019) found that the quality of attachment of 16 children to their caregivers was unchanged following behavioural feeding treatment. Although Phipps et al. (2022a, b) did not observe increases in indices of happiness during treatment for all children, these indices may increase later on, when the child begins to regularly consume new foods and drinks during mealtimes. For example, mealtimes may become associated with praise and positive interactions with the feeder (i.e., caregiver) while they may have previously been associated with repeated reprimands. Phipps et al. only measured indices of happiness during initial treatment, but we may learn more about a child’s happiness during meal-related activities after the child has met their goals to become an age- or developmentally typically feeder, or at least after they have begun regularly consuming food and liquid by mouth. Children may begin to experience the naturally appetitive properties of eating and drinking (e.g., increased social opportunities, increased preferences for food and liquid) or learn that eating is not painful, uncomfortable, or aversive. In fact, researchers have begun to evaluate child preference for food and liquid before and after treatment (e.g., Taylor, 2020; Taylor et al., 2019a, b; Zeleny et al., 2019) but more research, including long-term follow-up studies, is needed to better understand these possible treatment benefits.

The authors of the current study have observed improvements in other areas, such as increases in vocal verbal behaviour (i.e., appropriate language and communication), improvements in physical health (e.g., improved weight gain or blood work, reduced constipation), increased tolerance of novel routines or aversive procedures (e.g., tolerating physician visits, haircuts, or dental procedures), and reductions in behavioural rigidity (e.g., less change-resistant routines or problematic behaviour patterns). Caregivers in Knight et al. (2019) reported a positive impact on child emotional and behavioural functioning after feeding treatment.

There are no studies to our knowledge, that have directly assessed whether successful feeding treatment produces positive behavioural side effects (outside of mealtime), but based on caregiver report and anecdotal therapist observations, these events seem to be, at the very least, associated. It is unconfirmed why other behaviour improved. It could be that caregivers received helpful education on behaviour-analytic principles and began to apply those to target other behaviour. Alternatively, children may learn through repeated exposure, that non-preferred contexts or procedures involving the mouth are no longer aversive. In clinical practice, therapists implementing feeding interventions also engage with children on meal breaks and pair with reinforcers during and throughout the treatment experience. In those situations, it could be that behaviour-analytic therapists use naturalistic teaching strategies or apply healthy contingencies more generally (e.g., refrain from providing attention in the form of reprimands following instances of challenging behaviour) to promote widespread improvements in behaviour. In these cases, it is difficult to confirm whether the feeding intervention itself, caregiver and therapist behaviour, other extraneous variables (passage of time), or a combination of these events affect child behaviour. Researchers should continue to investigate these phenomena and collect data on other behaviour before, during, and after treatment.

Future Directions

It is vital that behaviour analysts extend data-based, individualised decision making to the area of social validity. Of equal importance is to keep caregivers and families at the forefront of the goal-setting, treatment-planning, and decision-making process, and to factor in child-specific needs, preferences, and goals. The studies outlined in this paper have started to address this aim, and we recommend the following considerations for future directions.

Comprehensive Measures

Practitioners should continue to place emphasis on all three elements of Wolf’s definition of social validity (i.e., goals, procedures, effects) at a minimum, rather than focusing primarily on the procedural elements (e.g., possible undesirable side effects of a given behaviour-analytic treatment). Although it is necessary to consider possible undesirable side effects, it should be equally important to consider other variables, such as goal importance and relevance to consumers, positive side effects, efficiency, procedural integrity, long-term outcomes, improvements in quality of life for the child and family, and maintenance. The social validity of the procedures used in feeding treatment should also extend to all behaviour-analytic treatment components and across interventions (e.g., differential tangible reinforcement, differential negative reinforcement, demand fading, shaping), and include comparisons to other commonly used treatments (e.g., escape extinction).

Taylor and Taylor (2022b) recommended also assessing the social validity of less commonly used, and possibly more complex procedures, such as treatments for teaching chewing skills, strategies that involve jaw or chin prompts, flipped spoon presentations, initial infant gum brush presentations, setting and adhering to appropriate exit criteria, and different types of noncontingent access to preferred or reinforcing items. Additionally, social validity should be examined in relation to case severity, history of previous treatments, and skill acquisition (rather than a focus solely on behaviour reduction). Larger programmes with greater patient volumes and more varied presentations or service intensity levels (and levels of caregiver support) could be in an optimal position to extend this research.

Comparative Measures

Social validity measurement is needed not only for behaviour-analytic treatments, but comparatively across other interventions (e.g., oral-motor exercises, food play, cognitive-behaviour therapy) conducted by other specialists providing feeding treatment, as well as with normative comparisons (e.g., outcomes with children who are typical eaters). More empirical assessment tools and data are necessary, especially considering the potential stress associated with and the impact of time and resources caregivers anecdotally report investing in treatments that do not meet their expectations. Researchers have discussed that escape extinction or other behaviour-analytic treatments can be intensive, difficult to implement, or associated with poor or limited social validity (e.g., Fernand et al., 2016). This could be true in some circumstances; however, it is crucial for practitioners to collect data on these events and make data-based decisions regarding which treatments may be most effective, warranted based on child severity, or preferred for children and their families. In some situations, it may not be warranted or possible to implement extinction-based treatment (e.g., without appropriate training and oversight).

Data are also needed on the social validity of behaviour-analytic treatments compared to the medical interventions that can result from feeding difficulties left untreated, such as nasogastric tube placement (e.g., children pulling tubes out requiring protective equipment, skin problems from facial tape), maintenance of gastrostomy tubes (e.g., infections, leaks), inserting suppositories, impacts and risks of hunger provocation approaches (e.g., weight loss, child tantrums due to denial of preferred foods/drinks), and medication refusal. Although lifesaving and required, caregivers have reported that with some medical interventions, there is intense prolonged refusal of the procedure (e.g., tube care, enemas, cooperation with medication), requiring physical holding from multiple people, and lack of success (e.g., Taylor, 2022). In Australia and New Zealand, the authors have also noted side effects due to barriers to receiving medical interventions such as prolonged nasogastric-tube use, waiting lists for gastrostomy tubes, as well as lack of needed tube placement in children with significant growth impairment (e.g., Taylor & Roglić, 2024). By default, medical interventions could be the only reliable alternative for children who do not have access to effective feeding treatment, yet the social validity of medical interventions could be lower than behaviour-analytic treatment.

Change-sensitive Measures

Social validity should be assessed across multiple points in time (e.g., before and during treatment, after caregiver training and caregiver-fed meals, short- and long-term follow-up), rather than once at the end of treatment. It is important for practitioners to assess caregiver preference for immediacy of treatment effects relative to avoidance of potential undesirable side effects before treatment begins. For example, researchers have demonstrated that some treatment alternatives may mitigate extinction-induced side effects (e.g., demand fading and making modifications more gradually), but those interventions could require additional time and resources before the child contacts success. Caregivers may place greater value in immediate effects with some increases in emotional responding opposed to extended evaluations with additional steps or treatment elements. In addition, more social validity data are needed comparing pre-treatment caregiver-fed meals to post-treatment caregiver-fed meals. Gathering pre-treatment levels of inappropriate mealtime behaviour will allow for a more accurate comparison to that which occurs during initial treatment exposure.

It is important to gather long-term follow-up data to assess maintenance, positive or negative side effects (or lack thereof), and procedural integrity (protocol need and use, drift). In addition, it is important for researchers to consider procedures that are necessary during initial treatment phases as well as the fading process and long-term planning that will be important for each family (e.g., approving use of electronics in the beginning of treatment but requesting to remove them long term). Researchers should continue to assess caregiver social validity but evaluate ratings after caregivers have learned how to implement the treatment and after they are consistently feeding meals with their child. Finally, researchers should continue to record and monitor child indices of happiness and unhappiness and other child emotional responding before, during, and after feeding treatment. It is equally important for researchers to measure the caregivers and family’s quality of life before, during, and after treatment.

Researchers could use social validity data to inform and individualise treatment progressions (Schwartz & Baer, 1991). Following treatment evaluations by trained professionals, Ahearn et al., (1996, 2001) and Borrero et al. (2013) had caregivers choose the intervention they preferred for training and home use. Using pre-admission surveys and interviews, Taylor and Taylor (2022b) evaluated this process and demonstrated significant clinical benefits. Before treatment, surveys provided a more formal and structured means for caregivers to respond and provide helpful information. This structure allowed caregivers to have an outline of potential procedures and take time to consider them without the provider present. Caregivers may feel more comfortable writing their feelings compared to verbalising them in the moment, and it may be helpful across cultural communication differences to solicit more input, similar to how informed consent should be obtained (e.g., thorough explanation, examples, opportunities to privately reflect, opportunities to ask questions and discuss). Collecting this information and collaborating before treatment was vital for the process in Taylor and Taylor (2022b). As one example, it was helpful for the practitioners in their efforts to plan goal progression, timing, and generalisation. In addition, behaviour analysts can collaborate with caregivers to include their input throughout treatment so they are able to continue making informed decisions.

Pre-treatment data on caregiver preference, choice, and feelings regarding treatment options may be used to adjust the starting point and overall speed of goal progression and amount of or dosage of a given treatment (e.g., how many steps or how long to persist with demand fading). Early assessment of caregiver preference may also provide more opportunities for caregiver and child choice, caregiver education, and permit the practitioner to more accurately identify the caregivers’ specific concerns that should be addressed first. Finally, ongoing caregiver assessment can allow the practitioner to evaluate various assessment or treatment options and enable practitioners and caregivers to make plans collaboratively.

By gathering objective caregiver data at multiple points during the treatment process, researchers can disseminate those data and provide future caregivers with more relevant or meaningful information. In addition, researchers can learn more about possible barriers to effective treatment to better address and target them in the future or better understand when to make referrals.

Validated Measures

Using the methodology in Anderson et al. (2021), further psychometrics and scale development is needed with larger more varied populations and stakeholders (e.g., recipients, other healthcare providers, teachers). More work is also needed in direct and observational measures (e.g., physiological measures) and quality of life indicators. In general, researchers should aim to identify objective tools for measuring social validity and to identify which treatment elements could reliably improve social validity (e.g., choice arrangements).

Collateral-effect Measures

Future researchers should consider empirically evaluating whether successful feeding intervention can promote or increase skills across other domains, improve health, and reduce other non-meal-related challenging behaviour. The authors of the current study reported observing reductions in challenging behaviour outside of mealtimes throughout their own clinical observations. Future researchers should investigate systematic methods for evaluating these types of concomitant changes in other behaviour (e.g., reduction of challenging behaviour during oral-hygiene routines, increased cooperation during non-preferred activities) during or following behaviour-analytic treatment of a feeding disorder. For example, researchers could conduct periodic scheduled observations of the child engaging in oral-hygiene routines, such as toothbrushing, to determine whether the child displays lower levels of negative vocalisations or increased cooperative behaviour. Along with those observations, researchers could ask caregivers to collect data at home when opportunities arise to perform oral hygiene routines. Finally, the researcher could arrange for pre- and post-visits with a dentist to determine whether there are improvements in dental health and oral hygiene, without direct intervention.

When possible, practitioners should collect pre- and post-measures on elements of the child’s physical health (e.g., bloodwork, nutrition analyses, bowel movement regularity and consistency) to better understand the health-related improvements that can occur due to improved diet. Through collaboration with medical providers and interdisciplinary team members, practitioners could gather these additional health-related data by encouraging regular medical check-ins with the child.

Culturally Sensitive Measures

Eating is significantly tied to culture. Professionals who assess and treat feeding difficulties should ensure they understand the relevant cultural variables that may affect caregiver decisions and goals regarding treatment. The authors of the current study have provided services in homes outside of the United States. In this process, the authors have observed eating differences from a wide variety and diversity of family backgrounds (e.g., Taylor & Taylor, 2022a). In these observations, the authors have determined that caregivers vary widely on their preferences for and definitions of home feeding practices concerning “forced-feeding.” Additionally, caregivers vary on their acceptability of feeding children as a non-self-feeder when they are of the age and ability to self-feed, desiring higher than typical body weights, drinking after meals rather than during, and general parenting styles, to name a few examples. As another example, caregivers in Taylor (2024) reported that in their culture, it was common to use chopsticks at an early age and that they did not consume snacks or singular foods often. Caregivers also conveyed high preference for escape extinction and faster and larger results (i.e., timely and greater goal achievement), and less preference for electronic incentives. Taylor and Taylor (2022b) attempted to gather cultural information via open-ended comments, but none were reported in the surveys despite their presence emerging during the treatment process.

Future researchers should aim to refine culturally sensitive feeding treatment practices to ensure goals and strategies are relevant, important, and acceptable to families of all different cultures. It could be that conducting more in-depth pre-treatment caregiver interviews regarding common cultural practices, expectations, and areas of importance could reveal an appropriate treatment progression and relevant child/caregiver goals for the practitioner.

Practical Implications