Abstract

Background

Excessive worry during adolescence can significantly impact mental health. Understanding adolescent concerns may help inform mental health early intervention strategies.

Objective

This study aimed to identify frequent concerns among Australian secondary school students, exploring individual and demographic differences. Whether adolescents’ most frequently reported concern was associated with mental health and wellbeing was also investigated.

Methods

A total of N = 4086 adolescents (Mage = 13.92) participated in an online survey, reporting their top concerns alongside demographic characteristics, mental health, and wellbeing. Data were analysed using both qualitative and quantitative approaches.

Results

Thematic analysis identified 11 different themes of adolescent concerns. A frequency analysis showed concerns relating to ‘School and Academics’ were most common (24.52% of all responses), consistent across females, males, school location (regional vs metropolitan areas), and socioeconomic background. Sexuality and gender diverse adolescents more frequently reported concerns about ‘Mental Health and Wellbeing’ and ‘Social Relationships’. Linear mixed models found ‘School and Academic’ concerns were associated with lower symptoms of depression (p < .001, d = 0.16) and anxiety (p < .001, d = 0.19) and higher wellbeing (p = .03, d = 0.07) compared to all other concerns.

Conclusion

‘School and Academic’ concerns were most common, however not associated with poorer mental health or wellbeing. Sexuality and gender diverse adolescents were more likely to report concerns regarding ‘Mental Health and Wellbeing’ and ‘Social Relationships’. Efforts aimed solely at reducing academic stress may not be the most effective approach to improving adolescent mental health. Longitudinal data into how concerns evolve over time could provide a nuanced understanding of their relationship with future mental health challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescence is a time of significant developmental change. During these years, young people go through biological maturation, social role transitions, and develop interpersonal, problem-solving, and other critical life skills (Sawyer et al., 2018; Wehmeyer & Shogren, 2017). Moreover, the development in cognitive ability leads adolescents to experience more complex and abstract concerns as their thought processes evolve (Arain et al., 2013). Some degree of worry is normal among adolescents who inevitably experience change and uncertainty as they navigate their way towards adulthood. In some cases, this worry can be protective, helping to identify possible threats (Guiterrez-Garcia & Contreras, 2013). However, excessive and prolonged worry can be maladaptive, leading to a myriad of adverse outcomes, including poorer physical health, increased substance use, poorer problem-solving skills, negative mood, poorer social and academic skills, and higher rates of insomnia and depression (Brosschot et al., 2006; Laugesen et al., 2003; Owczarek et al., 2020).

Previous research has investigated the idea of adolescent concerns in several different ways. For example, across a range of studies, young people have been asked about their ‘stressors’ (Núñez-Regueiro & Núñez-Regueiro, 2021), ‘worries’ (Hunter et al., 2022; Owczarek et al., 2020), ‘fears’ (Angelino et al., 1956), ‘problems’ (Collins & Harper, 1974), ‘hassles’ (Kanner et al., 1987), or ‘concerns’ (Huan et al., 2008). While these different descriptors have elicited varying responses, most studies have concentrated on daily experiences that cause adolescents some level of distress. Significantly, much of this literature has identified that daily stressors can be as predictive of mental health symptoms during adolescence as major life events such as parental divorce and childhood trauma (Low et al., 2012; Seiffge-Krenke, 2000). Daily stress may play an important role in mental health, via influencing individuals’ wellbeing and susceptibility to mental health disorders. According to Lazarus and Folkman’s Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (1984), stressors can range from minor daily inconveniences to larger stressful life events, and both can impact mental health based on the way an individual interprets or appraises this perceived threat to well-being, and the coping resources they have available to manage this threat. If this stress becomes excessive, it can serve as a significant precursor and mechanism underlying the development of mental ill health (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Newman et al., 2013; Rickels & Rynn, 2001). Given that almost half of all lifelong mental health conditions emerge before the age of 18 years (Solmi et al., 2022), together with the recent rise in the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and other mental health problems among adolescents (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2022; Brennan et al., 2021) it is important that adolescent daily concerns are well understood and their potential role in the development of mental illness investigated. Therefore, it is important to develop a contemporary and comprehensive understanding of the sources and impact of adolescent concerns.

Historically, research into the content of adolescent concerns has identified common themes including school, family, social relationships, health, and broader socio-political issues (Pintner & Lev, 1940; Silverman et al., 1995). Contemporary research has validated these themes as well replicated and robust, particularly those focused on school and academic competence (Nunez-Regueiro et al., 2021; Owczarek et al., 2020). A large Australian population-based survey of 20,207 adolescents aged 15–19 years found that 83.7% of respondents expressed some degree of concern about ‘school or study problems’ (Tiller et al., 2021). Recent survey results from an Australian-based organisation, ‘ReachOut’, also identified study stress as a major concern for young people, with half of those surveyed reporting that this stress also significantly impacts their mental health, wellbeing, and physical health (ReachOut, 2022). This consistent reporting of school and academic stress as a top concern is important given that persistent academic stress during adolescence is associated with negative impacts on students’ learning capacity, academic performance, employability, sleep quality and quantity, physical health, mental health, and substance use (Anda et al., 2000; Pascoe et al., 2020; Schmid, 2018). The effect of academic stress on mental health is a global phenomenon, with data showing an increased risk of depression among adolescents in China (Zhu et al., 2021), India (Jayanthi et al., 2015), and Norway (Moksnes et al., 2016). A recent systematic review reported an association between academic pressure and depression, anxiety, self-harm, suicidality, suicide attempts, and suicide (Steare et al., 2023). Despite this evidence, differing perspectives persist about whether academic stress in adolescents is inherently problematic. For example, some researchers suggest that academic stress is inevitable and a constructive part of the learning process, equipping students with the essential skills and resources to face the demands of adulthood (Banks & Smyth, 2015).

While adolescent concerns have been studied for many years, there are several limitations to the existing literature, including variation in research design, a focus on clinical samples or small sample sizes, and broad definitions of ‘concerns’. One of the key limitations to the most recent research about adolescent concerns is the introduction of bias through the use of predetermined domains assumed to be common concerns for adolescents, many of which focus on school and academic stress, relationships, and family concerns (Tiller et al., 2021). This limits adolescents to selecting themes that have been predetermined by researchers. Furthermore, given that in recent times the world has changed significantly with advances in technology, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, evolving social norms, environmental concerns, and economic challenges, a contemporary investigation into adolescent concerns is warranted. To address these limitations, the current study involved asking a large community sample of adolescents to share their top concerns in an open-ended, free text format. The question used the broad term ‘concerns’ rather than ‘worries’ to encompass a wide range of daily thoughts and experiences that might cause adolescents distress. This study was embedded in a larger prospective cohort study of adolescent mental health and wellbeing (the Future Proofing Study; Werner-Seidler et al., 2022).

The first aim of the current study was to develop a contemporary understanding of what issues were concerning adolescents most frequently, and to discern whether these concerns differed among subgroups including gender, sexuality, socioeconomic background, and school location (metropolitan or regional area). We hypothesised that females and marginalised groups, specifically gender and sexuality diverse adolescents, may report concerns about peer relationships more frequently than their male, cisgender, and heterosexual counterparts due to the greater emphasis that females place on social support (Milner et al., 2016) and the heightened levels of social isolation experienced among the gender and sexuality diverse community (Madireddy & Madireddy, 2020; Stargell et al., 2020). No other directional hypotheses were made.

The second aim was to explore whether the most frequent concern reported by adolescents was associated with higher symptoms of depression and anxiety and decreased wellbeing when compared to those who reported any other concerns. Based on previous research showing that common daily stressors were as predictive of mental health symptoms as larger stressful life events (Low et al., 2012; Pascoe et al., 2020; Schmid, 2018; Seiffge-Krenke, 2000; Steare et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2021), we hypothesised that the most frequently reported concern would be associated with higher symptoms of depression and anxiety and lower wellbeing scores, when compared to adolescents reporting all other concerns. The widespread prevalence of a specific concern poses an opportunity to understand whether this concern plays a role in adolescent mental health.

Method

Study Design

The current study is a cross-sectional secondary analysis of data collected as part of the Future Proofing Study (FPS), a five-year prospective cohort study of risk and protective factors associated with adolescent mental illness (Werner-Seidler et al., 2022). Ethics approvals for the FPS were obtained from the University New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (HC180836), the State Education Research Applications Process for the New South Wales Department of Education (SERAP2019201), and relevant Catholic Schools Dioceses across Australia. Full details of the study are outlined in Werner-Seidler et al. (2022).

Setting

All government, independent, and eligible Catholic secondary schools in New South Wales, as well as independent schools in capital cities from around Australia, were invited to participate in the FPS. Written informed consent was provided from a parent or guardian and the adolescent prior to study participation. Adolescents were free to withdraw at any time. Data for the current study were collected from students at 122 Australian secondary schools (a subset of the FPS cohort) and took place between August 2020 to March 2022.

Participants

All Year 8 students (aged 12–14 years) at participating schools who owned a smartphone with iOS or Android operating system and an active phone number were invited to take part in the FPS. A sub-sample of students enrolled in the FPS who provided an answer to the question of interest, were included in the current study.

Measures

Individual and Demographic Characteristics

Participants’ individual characteristics were assessed via self-report questionnaires and included age, gender identity (male, female, gender diverse), sexuality (heterosexual, sexuality diverse), Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander identity (yes, no), and language spoken most at home (English, others).

School Characteristics

Participants’ school characteristics were imputed from a publicly available database curated by the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA), and included school location (metropolitan areas, regional areas), school sector (government, non-government), and Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (ICSEA). The ICSEA is a scale of socio-educational advantage that is computed for each Australian school. Values typically range from 500 (representing schools with extremely disadvantaged student backgrounds) to 1300 (representing schools with extremely advantaged student backgrounds), with a population median of 1000. ICSEA scores were dichotomized into less advantaged schools (≤ 1000) and more advantaged schools (≥ 1001) for the subgroup analyses used in this paper.

Top Concerns

Students were asked to report on the top issues concerning them via an open-ended question: “What issues are concerning you at the moment? These could relate to you, your community, or the world. You can list up to three”. Students were provided with three text boxes wherein they could type their concerns in their own words and were not limited by how much or how little they could write.

Depression

The Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents (PHQ-A; Johnson et al., 2002) is an adolescent-appropriate adaptation of the PHQ-9, a nine-item depression severity screening tool based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria (range 0–27; higher score indicates greater depression). A score of ≥ 15, reflecting moderately severe symptoms, was used as the clinical threshold. The internal consistency of the PHQ-A in this study was high (Cronbach’s α = 0.88).

Anxiety

The Children’s Anxiety Scale Short-Form (CAS-8) is an eight-item measure of anxiety based on the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS; Spence, 1998). The CAS-8 incorporates questions assessing generalised anxiety and social anxiety with total scores ranging from 0 to 24 (higher score indicates greater anxiety). A score of ≥ 14 was used as the clinical threshold. The internal consistency of the CAS-8 in this study was high (α = 0.90).

Wellbeing

The Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS; Tennant et al., 2007) is a shortened 7-item version of the 14-item Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS). The SWEMWBS consists of seven statements about thoughts and feelings over the past two weeks. Ratings are made on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = None of the time, 2 = Rarely, 3 = Some of the time, 4 = Often, 5 = All of the time). Total scale scores are calculated by summing item scores and transforming the total score using a conversion table. Total scores can range from 7 to 35. A higher score indicates a higher level of mental wellbeing. The internal consistency of the SWEMWBS in this study was high (α = 0.88).

Procedure

Students with parental consent were invited to attend a session at their school which was facilitated by one or more members of the Future Proofing Study team. At this session, students were asked to provide their own consent, and if provided, they were then asked to complete the baseline questionnaire (including the Top Concerns question) via a secure online portal. Students completed questionnaires independently, with no input from their teachers or the study team. Full questionnaire details are available in Werner-Seidler et al. (2022). More than half (57%) of the baseline sessions were facilitated in person by the study team, while the rest were facilitated remotely via ZOOM due to the physical distancing restrictions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. These restrictions limited visitor access to schools, resulting in the study team facilitating the survey via Zoom, while the students were at school and supervised by their teachers. The sessions typically lasted between 60 and 90 minutes.

Thematic Analysis

The qualitative data provided by students about their top three concerns was analyzed using a thematic analysis. The process and approach outlined by Braun and Clark (2019) was used to code, analyze, and interpret the students’ free text responses. Analysis involved an inductive approach to developing a coding framework (Bengtsson, 2016; Erlingsson & Brysiewicz, 2017), which was appropriate given the exploratory nature of the research question. Analysis involved an iterative process of reading and coding responses to develop themes of concern. A member of the coding team (LB) examined the responses of a subset of 200 students, seeking to identify underlying meanings and patterns within the data. Initial codes were then developed by the coding team (AB, LB, KM, HF, AW-S, MH) and applied to the subset of 200 responses to develop a preliminary coding framework. These initial codes were then synthesized by AB and LB into potential themes which represented different layers of interaction between participants and their world. All students’ first reported concerns were then independently coded by AB and LB and any discrepancies were resolved through collaborative discussion with the wider coding team. Codes and themes were refined through an iterative process whereby themes were consolidated, code definitions were clarified, and coding challenges were addressed, including whether to apply double coding, or interpret meaning from responses. This process ensured each code had enough data to support it, was sufficiently distinct from each other, and accurately captured all student responses. All responses were then independently coded by AB and LB producing an inter-rater reliability of 96%.

Statistical Analysis

The full dataset, including the qualitative open-ended answers with the quantitative data, was imported into SPSS v28. To address the first aim, a descriptive analysis of frequencies was performed overall and by subgroups including: gender, sexuality, socioeconomic background, and school location (metropolitan or regional areas), to understand what issues were concerning adolescents most frequently, and to discern whether these concerns differed among subgroups. To ensure that every student’s concern was given equal weight, only the first reported concern of each student was used in this analysis, as not all students provided more than one answer. Chi-square analyses were used to compare frequencies of top concerns between the subgroups. A p-value of < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. Reported effect sizes are phi (φ) for categorical outcomes where 0.10 is small, 0.30 is medium and 0.50 is large (Cohen, 1988b; Wickens & Keppel, 2004).

To address the second aim, a linear mixed model analysis was performed to test whether the most frequently reported theme of concern was associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety, and wellbeing. Two fixed effects were entered into the model: gender (female, male, gender diverse) and ICSEA (socioeconomic background). Participants’ school ID was entered into the model as a random effect to account for the potential influence of school-specific factors. Cohens d effect sizes are reported (Cohen, 1988a).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Sample characteristics are provided in Table 1. A total of 4086 Year 8 students were included in this analysis (68.28% of the total eligible sample of 5984). The mean age was 13.92 years (SD = 0.52). Most adolescents were female (n = 2263, 55.38%) and a small proportion were gender diverse (n = 139, 3.40%). Participants were predominantly heterosexual (n = 2893, 70.80%) and 14.71% were sexuality diverse (n = 601). The majority (n = 3794, 92.85%) spoke English as their main language and 4.31% (n = 176) reported Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander identity. Most students attended school in metropolitan areas (n = 3167, 77.51%), and slightly more students attended government schools (n = 2095, 51.27%) compared to non-government schools (n = 1991, 48.73%). Most participants attended schools with an ICSEA value ≥ 1001 indicating relatively more advantaged socioeconomic backgrounds, (n = 2978, 72.88%), and 27.12% (n = 1108) of participants attended schools with an ICSEA value ≤ 1000 indicating relatively less advantaged socioeconomic backgrounds. The mean symptom score for depression was 8.18 (SD = 6.36), and anxiety was 9.20 (SD = 5.47), with 17.67% (n = 722) and 22.39% (n = 915) of adolescents scoring above the clinical threshold for depression and anxiety, respectively. The mean wellbeing score was 20.93 (SD = 4.51) indicating ‘medium’ levels of wellbeing (Ng Fat et al., 2017).

Thematic Analysis

See Table 2 for the final coding framework outlining themes, codes, and illustrative quotes.

The thematic analysis generated 11 distinct themes (which encapsulated between one to five different sub-codes), and included: ‘School and Academics’ (tests, exams and grades; school in general), ‘COVID-19’ (safety of self; safety of others; impact on community), ‘Social Relationships’ (peer engagement and bullying; romantic relationships; other non-family relationships), ‘Mental Health and Wellbeing’ (mental ill health; emotions and identity concerns; concentration and focus; body image; drugs and alcohol), ‘Family and Home Life’ (family relationships; companion animals), ‘Society and the Environment’ (politics and society; environment and climate change; safety and security; philosophical and existential), ‘Physical Health’ (health, disease and ailments; sleep disturbances), ‘Sport, Digital and Extracurricular’ (extracurricular activities and hobbies; social media and technology; work/life balance, time management and procrastination), ‘Work, Money and My Future’ (future career; money concerns; the future), ‘Discrimination’ (LGBTQIA+; discrimination and equality), and ‘Other’.

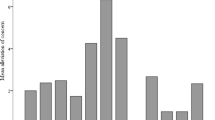

Most Frequently Reported Concerns

See Table 3 for a list of themes of concern with accompanying frequencies.

There were 9883 valid responses. A total of 4086 students reported one issue, 3296 students reported two issues, and 2501 students reported three issues. A frequency analysis was performed on students’ first responses (n = 4086) to determine the most frequently reported themes. The most frequently reported concerns were related to the themes ‘School and Academics’ (n = 1002, 24.52%), ‘COVID-19’ (n = 663, 16.23%), ‘Social Relationships’ (n = 547, 13.39%), ‘Mental Health and Wellbeing’ (n = 431, 10.55%) and ‘Family and Home Life’ (n = 415, 10.16%).

Most Frequently Reported Concerns of Male, Female and Gender Diverse Students

See Table 4 for a complete list of students’ top concerns by subgroups.

The most common theme reported by both males and females was ‘School and Academics’, accounting for 25.37% and 25.01% of all male and female responses respectively, with no difference between the groups (p = .80). For female students, the second most common theme was ‘Social Relationships’ (n = 355, 15.69% of all female responses), followed by ‘COVID-19’ (n = 321, 14.18% of all female responses). For male students, the second most common theme was ‘COVID-19’ (n = 331, 20.58% of all male responses), followed by ‘Society and the Environment’ (n = 185, 11.50% of all male responses). For gender diverse students, the most common theme was ‘Mental Health and Wellbeing’ (n = 35, 25.18% of all gender diverse responses), followed by ‘Social Relationships’ (n = 21, 15.11% of all gender diverse responses), then ‘School and Academics’ (n = 17, 12.23%), ‘Society and the Environment’ (n = 17, 12.23%) and ‘Family and Home Life’ (n = 17, 12.23%).

Most Frequently Reported Concerns of Sexuality Diverse Students

The most common theme reported by sexuality diverse students was ‘Mental Health and Wellbeing’ (n = 107, 17.80% of all responses from sexuality diverse participants). A chi square test showed that sexuality diverse students reported concerns relating to the theme ‘Mental Health and Wellbeing’ significantly more frequently than heterosexual students (X2 (1, N = 3494) = 40.73, p < .001, φ = 0.11). The second most common theme reported by sexuality diverse students was ‘Social Relationships’ (n = 98, 16.31%), followed by ‘School and Academics’ (n = 95, 15.81%). Concerns relating to the theme of ‘Discrimination’ were reported by almost 8% of sexuality diverse students, compared to fewer than 1% of heterosexual students.

Most Frequently Reported Concerns of Students from More and Less Advantaged Socioeconomic Backgrounds

The most frequently reported themes of concern did not differ between students who attended less compared to more advantaged schools. ‘School and Academics’ was most frequently reported across both groups (ICSEA ≤ 1000: n = 205, 18.50% vs. ICSEA ≥ 1001: n = 797, 26.76%), although students attending more advantaged schools reported concerns related to ‘School and Academics’ significantly more frequently than students attending less advantaged schools (X2 (1, N = 4086) = 29.78, p < .001, φ = 0.09). The second most frequently reported concern by students from both groups was ‘COVID-19’ (ICSEA ≤ 1000: n = 198, 17.87% vs. ICSEA ≥ 1001: n = 465, 15.61%), followed by ‘Social Relationships’ (ICSEA ≤ 1000: n = 180, 16.25% vs. ICSEA ≥ 1001: n = 367, 12.32%).

Most Frequently Reported Concerns of Students from Metropolitan and Regional Areas

The most frequently reported themes did not differ between students attending school in metropolitan and regional areas. ‘School and Academics’ was most frequently reported across both groups (metropolitan: n = 832, 26.27% vs. regional: n = 170, 18.50%), although students attending school in metropolitan areas reported concerns related to ‘School and Academics’ significantly more frequently than students attending schools in regional areas (X2 (1, N = 4086) = 23.25, p < .001, φ=-0.08). The second most frequently reported concern by both groups were ‘COVID-19’ (metropolitan: n = 507, 16.01% vs. regional: n = 156, 16.97%), followed by ‘Social Relationships’ (metropolitan: n = 397, 12.54% vs. regional: n = 150, 16.32%).

Association between most Frequently Reported Concern (‘School and Academics’) with Depression, Anxiety and Wellbeing

See Tables 5 and 6 for complete results of the linear mixed model analysis performed and comparison of means and standard deviations for depression, anxiety, and wellbeing scales.

There was evidence that concerns related to ‘School and Academics’ were associated with lower depression symptoms, t(4079.99) = 4.54, p < .001, and lower anxiety symptoms, t(4080.84) = 5.67, p < .001, when compared to all other themes of concern combined, controlling for fixed effects of gender and ICSEA and the random effect of participants’ school. There was also evidence that concerns related to ‘School and Academics’ were associated with greater levels of wellbeing, t(4077.47) = -2.17, p = .03, when compared to all other themes of concern combined. Small effect sizes were found for depression (d = 0.16), anxiety (d = 0.19), and wellbeing (d=-0.07).

An additional analysis was conducted to explore the possibility that the above-reported differences in the relationship between ‘School and Academics’ and mental health symptoms might have been influenced by participants who reported ‘Mental Health and Wellbeing’ as a significant concern. That is, including participants in the analysis who reported ‘Mental Health and Wellbeing” as their primary concern may have conflated the overall pattern of findings. Therefore, in the additional analysis we excluded any participant who reported a primary concern related to ‘Mental Health and Wellbeing’ and focused solely on those who reported other concerns as the comparator group. The pattern of results was largely unchanged, with evidence that concerns related to ‘School and Academics’ were associated with lower depression symptoms, t(3648.23) = 2.68, p = .007, and lower anxiety symptoms, t(3646.52) = 4.04, p < .001, when compared to all other themes of concern except ‘Mental Health and Wellbeing’. There was no evidence of an association between concerns related to ‘School and Academics’ and wellbeing, t(3641.20) = − .80, p = .423.

Discussion

The present study had two aims. The first was to identify the most common self-reported concerns of adolescents in their own words and to examine these concerns by subgroup. The most frequently reported theme of concern was ‘School and Academics’, cited by 24.52% of all students. This was followed by ‘COVID-19’ (16.23%), ‘Social Relationships’ (13.39%), ‘Mental Health and Wellbeing’ (10.55%) and ‘Family and Home Life’ (10.16%). ‘School and Academics’ was the most frequently reported theme of concern among females (25.01%) and males (25.37%), those from advantaged (26.76%) and less advantaged (18.50%) socioeconomic backgrounds, and those from metropolitan (26.27%) and regional areas (18.50%). Differences in the most frequently reported themes of concern were found among adolescents who identified as gender and sexuality diverse, who instead reported ‘Mental Health and Wellbeing’ most frequently, with 25.18% of gender diverse and 17.80% of sexuality diverse adolescents highlighting this as their primary concern. ‘Social Relationships’ followed, with 15.11% of gender diverse and 16.31% of sexuality diverse adolescents citing it as a prominent concern.

These findings align with previous reviews of the literature identifying school and academics as a primary concern among adolescents (Nunez-Regueiro et al., 2021; Owczarek et al., 2020). These findings could be partially explained by the fact that a substantial portion of an adolescent’s week is spent at school. In addition, the intentionally challenging nature of schoolwork also makes school and academics a likely source of concern for many students. A substantial proportion of school-related concerns reported by students in this study revolved around assessments, grades, exams, and schoolwork, prompting questions about the style of assessment that occurs within schools. Extensive academic stress has been demonstrated to have adverse consequences on adolescents, including poorer academic outcomes, sleep quality, physical and mental health, and increased substance use (Pascoe et al., 2020). Australian students report higher levels of anxiety about schoolwork when compared to other OECD countries (Schmid, 2018). Notably, Finnish students have consistently reported lower levels of academic related anxiety, scoring significantly lower than the OECD average (Schmid, 2018). The Finnish education model’s success in mitigating academic stress is underpinned by a shift away from excessive testing and towards a more holistic teaching model encompassing social and emotional learning (Ustun & Eryilmaz, 2018). A pivotal aspect of this transformation is attributed to the quality of teacher education, the higher social status attributed to the teaching profession, and the excellent working conditions for teachers (Ustun & Eryilmaz, 2018). The success of these changes in Finland highlights the importance of the teacher’s role in creating a conducive learning environment for students, with positive impacts on both mental health and academic outcomes (Oberle et al., 2018). Furthermore, in other studies, positive school climates and student-teacher relationships have been shown to be protective against the development of mental health problems (Oberle et al., 2018; Patalay & Fitzsimons, 2018) and show high associations with students’ academic outcomes (Zullig et al., 2014).

The second aim of this study was to investigate the association between adolescents’ most frequently reported theme of concern and symptoms of depression and anxiety, and wellbeing, compared to all other themes of concern. We found that adolescents who reported concerns related to ‘School and Academics’ were likely to have lower symptoms of depression and anxiety, and higher overall wellbeing scores when compared to students reporting concerns for all other themes combined. These findings did not align with our hypotheses; however, they do support previous research suggesting that school and academic stress may be a normative experience for adolescents and elicit a ‘healthy’ level of worry (Rudland et al., 2020). This healthy level of worry, referred to as ‘eustress’, is described as an optimal state of arousal that may serve as a protective factor for mental health by fostering increased motivation, engagement, and better performance (Rudland et al., 2020). It may also be that individuals with lower levels of depression and anxiety are more capable of focussing on school and academics and better able to cope with the stress it causes, while students experiencing poorer mental health may be ‘preoccupied’ with other concerns that evoke a higher level of distress, for example, difficult interpersonal relationships with peers or family. This is consistent with a recent study showing that concerns about peer relationships and about interpersonal interactions are more strongly associated with mental health symptoms than personal academic concerns (Kim, 2021). These findings suggest that intervention efforts aimed solely at reducing academic stress among adolescents may not be the most effective approach to improving adolescent mental health. Instead, early interventions may be better suited to target other areas that may be causing higher levels of distress.

Although school stress may be inevitable and possibly beneficial to some extent, it is important to acknowledge that it may have the potential to contribute to adverse consequences in some individuals. This study examines the concerns of Year 8 students, aged 13–14 years. It is possible that our findings may not be generalisable to all adolescent age groups given that academic stress is likely to intensify as students progress to the senior years of high school where greater emphasis is placed on academic outcomes. As the most frequently reported theme of concern by all students, school and academic concerns still warrant ongoing monitoring based on the well-established impact that excessive and prolonged academic stress can have on the mental wellbeing of adolescents (Anda et al., 2000; Pascoe et al., 2020; Schmid, 2018; Steare et al., 2023).

Top Concerns Among Gender and Sexuality Diverse Adolescents

As hypothesised, our results showed that the predominant themes of concern differed between some subgroups of adolescents, specifically as a function of gender and sexuality.

We found that females expressed concerns about ‘Mental Health and Wellbeing’ nearly two-fold more frequently than males (12.15% and 7.15%, respectively) which likely reflects the higher prevalence of depression and anxiety among adolescent females than males both in our sample (see Table 1) and in the general population (Brunton, 2018). Concerns about ‘Social Relationships’ were also more frequently reported by females than males which aligns with existing literature highlighting the greater emphasis adolescent females place on social relationships compared to their male counterparts (Milner et al., 2016). Notably, an absence of adequate social support has been identified as a key predictor of depression in females compared to males (Santini et al., 2015), highlighting the importance of recognising poor social relationships as a risk factor for poor mental health in adolescent females.

Further, ‘Mental Health and Wellbeing’ and ‘Social Relationships’ were the most frequently reported themes of concern among adolescents identifying as gender and sexuality diverse. This could be explained by the well-documented higher rates of bullying, victimisation, and violence experienced by these adolescents at school, which often result in social isolation, depression, psychological distress, and suicidal ideation (Madireddy & Madireddy, 2020; Silva et al., 2021; Stargell et al., 2020). These findings provide valuable insights into the type of support that may be required for gender and sexuality diverse students within the school context, suggesting that supporting positive social relationships and fostering more inclusive school environments are important components to improving their wellbeing. However, discrimination and isolation experienced by gender and sexuality diverse adolescents extends beyond the school environment. A holistic approach to improving the mental health of these marginalised groups relies on creating supportive environments both within and outside the school environment. Fostering inclusivity within family units and community organisations, such as sports and healthcare services, may promote social acceptance and improve the mental wellbeing of gender and sexuality diverse adolescents (Silva et al., 2021; Storr et al., 2022).

While ‘Mental Health and Wellbeing’ and ‘Social Relationships’ were the most prevalent themes of concern among adolescents identifying as gender and sexuality diverse, ‘School and Academics’ remained the third most prevalent theme, with only a marginal 2% difference between the top three themes. This suggests that concerns about ‘School and Academics’ remain a prevalent theme of worry for all students. Given our findings, and the well-established interrelationship between mental health, social relationships, and academic performance (Long et al., 2021; Sacerdote, 2011), it’s important to acknowledge the interconnected nature of these three factors and the influence they collectively yield on the mental health and wellbeing of all adolescents. Schools provide an opportunistic environment where simultaneous support for mental health, social relationships, and academic performance can be facilitated. However, to capitalize on this opportunity, collaboration between health and education systems, as well as with broader community and family units, is needed. The World Health Organization’s ‘Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2030’ calls on all countries to achieve more meaningful progress towards better mental health through more coordinated services from both the health and social sectors (World Health Organization, 2021). By reducing academic pressure and fostering positive social relationships, both within the school environment and in the wider community, an indirect route to improving the mental health and wellbeing of adolescents may be established.

Limitations

Several limitations to the study warrant mention. First, it was a requirement to own a smartphone with iOS or Android operating system to participate in the study. This may have resulted in the exclusion of those students who lack access to such devices. However, phone ownership levels among Australia teenagers is high (Rhodes, 2017), mitigating this risk at least in part. Second, data were collected within a school setting. This environment may naturally influence students’ responses as school-related concerns are likely to be top of mind for participants. Third, this study included participants from the broader Future Proofing Study who answered the question about their top concerns. This comprised 68.28% of the overall eligible sample (4086 of 5984). We are unable to ascertain why 31.72% of the sample did not answer this question, with possibilities including: (i) they did not reach this part of the question battery; (ii) they did not wish to answer this question and so skipped it; or (iii) they did not have any concerns to report. It is therefore possible that the final sample in this study was not representative of the broader sample, thereby introducing a level of selection bias. Fourth, despite providing free text boxes with unlimited word counts, many students responded with one-word answers which limited the depth of understanding we could draw from their responses. Employing a more nuanced and in-depth qualitative approach that encourages students to elaborate on the issues that most concern them could provide valuable insights into the specific aspects of school and academics that are concerning students. It would also be useful to understand the intensity of students’ concerns as this would help to determine the level of subjective distress each concern is causing. Finally, these surveys took place during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia (2020–2022) which likely influenced the themes of concerns reported.

Conclusion

This paper advances the literature by providing a contemporary picture of adolescents’ concerns using their own words rather than limiting them with predefined lists. This fosters a more authentic and unfiltered response. The results of this study align with existing literature and indicate that concerns related to ‘School and Academics’ remain one of the most prevalent areas of concern among adolescents. Importantly, our findings show that these concerns may not necessarily be indicative of poorer mental health and wellbeing. Efforts aimed solely at reducing academic stress may not be the most effective approach to improving adolescent mental health. Adolescents who identify as gender or sexuality diverse may benefit from more tailored and focussed support, addressing their individualised areas of concern, particularly around mental health and peer relationships. The longitudinal nature of the Future Proofing Study will facilitate ongoing insights into how adolescent concerns change over time, how concerns may differ between demographic groups, and what types of concerns may function as predictors for the onset of future mental health challenges.

Data Availability

Research data are not available to be shared.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. American Psychiatric Association. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

Angelino, H., Dollins, J., & Mech, E. V. (1956). Trends in the fears and worries of school children as related to socio-economic status and age. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 89(2), 263–276.

Arain, M., Haque, M., Johal, L., Mathur, P., Nel, W., Rais, A., Sandhu, R., & Sharma, S. (2013). Maturation of the adolescent brain. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 449–461. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S39776.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2022). National study of mental health and wellbeing.

Banks, J., & Smyth, E. (2015). Your whole life depends on it’: Academic stress and high stakes testing in Ireland. Journal of Youth Studies, 18(5), 598–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2014.992317.

Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. Nursing Plus Open, 2, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

Brennan, N., Beames, J. R., Kos, A., Reily, N., Connell, C., Hall, S., Yip, D., Hudson, J., O’Dea, B., Di Nicola, K., & Christite, R. (2021). Psychological distress in young people in Australia: Fifth biennial youth mental health report 2012–2020.

Brosschot, J. F., Gerin, W., & Thayer, J. F. (2006). The perseverative cognition hypothesis: A review of worry, prolonged stress-related physiological activation, and health. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 60(2), 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPSYCHORES.2005.06.074.

Brunton, C. (2018). Headspace national youth mental health survey 2018. https://headspace.org.au/assets/headspace-National-Youth-Mental-Health-Survey-2018.pdf.

Cohen, J. (1988a). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587.

Cohen, J. (1988b). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, (2nd edition). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc. Hillsdale, New Jersey, 13.

Collins, J. K., & Harper, J. F. (1974). Problems of adolescents in Sydney, Australia. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 125(1), 187–194.

De Anda, D., Baroni, S., Boskin, L., Buchwald, L., Morgan, J., Ow, J., Gold, J. S., & Weiss, R. (2000). Stress, stressors and coping among high school students. Children and Youth Services Review, 22(6), 441–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0190-7409(00)00096-7.

Erlingsson, C., & Brysiewicz, P. (2017). A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. African Journal of Emergency Medicine, 7(3), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.001.

Guiterrez-Garcia, A., & Contreras, M. C. (2013). Anxiety: An adaptive emotion. New Insights into Anxiety Disorders. InTech. https://doi.org/10.5772/53223.

Huan, V. S., See, Y. L., Ang, R. P., & Har, C. W. (2008). The impact of adolescent concerns on their academic stress. Educational Review, 60(2), 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131910801934045.

Hunter, S. C., Houghton, S., Kyron, M., Lawrence, D., Page, A. C., Chen, W., & Macqueen, L. (2022). Development of the Perth adolescent worry scale (PAWS). Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 50(4), 521–535.

Jayanthi, P., Thirunavukarasu, M., & Rajkumar, R. (2015). Academic stress and depression among adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Indian Pediatrics, 52, 217–219.

Johnson, J. G., Harris, E. S., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2002). The patient health questionnaire for adolescents: Validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30(3), 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00333-0.

Kanner, A. D., Feldman, S. S., Weinberger, D. A., & Ford, M. E. (1987). Uplifts, hassles, and adaptational outcomes in early adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 7(4), 371–394.

Kim, K. M. (2021). What makes adolescents psychologically distressed? Life events as risk factors for depression and suicide. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(3), 359–367.

Laugesen, N., Dugas, M. J., & Bukowski, W. M. (2003). Understanding adolescent worry: The application of a cognitive model. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1021721332181.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

Long, E., Zucca, C., & Sweeting, H. (2021). School Climate, peer relationships, and adolescent Mental Health: A Social Ecological Perspective. Youth & Society, 53(8), 1400–1415. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X20970232.

Low, N. C. P., Dugas, E., O’Loughlin, E., Rodriguez, D., Contreras, G., Chaiton, M., & O’Loughlin, J. (2012). Common stressful life events and difficulties are associated with mental health symptoms and substance use in young adolescents. Bmc Psychiatry, 12(1), 116. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-116.

Madireddy, S., & Madireddy, S. (2020). Strategies for schools to prevent psychosocial stress, stigma, and suicidality risks among LGBTQ + students. American Journal of Educational Research, 8(9), 659–667.

Milner, A., Krnjacki, L., & LaMontagne, A. D. (2016). Age and gender differences in the influence of social support on mental health: A longitudinal fixed-effects analysis using 13 annual waves of the HILDA cohort. Public Health, 140, 172–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2016.06.029.

Moksnes, U. K., Løhre, A., Lillefjell, M., Byrne, D. G., & Haugan, G. (2016). The Association between school stress, life satisfaction and depressive symptoms in adolescents: Life satisfaction as a potential mediator. Social Indicators Research, 125(1), 339–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0842-0.

Newman, M. G., Llera, S. J., Erickson, T. M., Przeworski, A., & Castonguay, L. G. (2013). Worry and generalized anxiety disorder: A review and theoretical synthesis of evidence on nature, aetiology, mechanisms, and treatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 275–297. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185544.

Ng Fat, L., Scholes, S., Boniface, S., Mindell, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2017). Evaluating and establishing national norms for mental wellbeing using the short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS): Findings from the Health Survey for England. Quality of Life Research, 26(5), 1129–1144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1454-8.

Nunez-Regueiro, F., Archambault, I., Bressoux, P., & Nurra, C. (2021). Measuring stressors among children and adolescents: A scoping review 1956–2020. Adolescent Research Review, 1–20.

Núñez-Regueiro, F., & Núñez-Regueiro, S. (2021). Identifying salient stressors of adolescence: A systematic review and content analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(12), 2533–2556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01492-2.

Oberle, E., Guhn, M., Gadermann, A. M., Thomson, K. C., & Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2018). Positive mental health and supportive school environments: A population-level longitudinal study of dispositional optimism and school relationships in early adolescence. Social Science \& Medicine, 214, 154–161.

Owczarek, M., McAnee, G., McAteer, D., & Shevlin, M. (2020). What do young people worry about? A systematic review of worry theme measures of teen and preteen individuals. Children Australia, 45(4), 285–295.

Pascoe, M. C., Hetrick, S. E., & Parker, A. G. (2020). The impact of stress on students in secondary school and higher education. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 104–112.

Patalay, P., & Fitzsimons, E. (2018). Development and predictors of mental ill-health and wellbeing from childhood to adolescence. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(12), 1311–1323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1604-0.

Pintner, R., & Lev, J. (1940). Worries of school children. The Pedagogical Seminary and Journal of Genetic Psychology, 56(1), 67–76.

ReachOut. (2022, October 9). Study stress impacting students’ mental health, sleep and relationships according to new research by ReachOut. https://about.au.reachout.com/blog/study-stress-impacting-students----mental-health--sleep-and-relationships-according-to-new-research-by-reachout.

Rhodes, A. (2017). Screen time and kids: What’s happening in our homes. Detailed report

Rickels, K., & Rynn, M. A. (2001). What is generalized anxiety disorder? The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62, 4–12.

Rudland, J. R., Golding, C., & Wilkinson, T. J. (2020). The stress paradox: How stress can be good for learning. Medical Education, 54(1), 40–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13830.

Sacerdote, B. (2011). Peer Effects in Education: How Might They Work, How Big Are They and How Much Do We Know Thus Far? (pp. 249–277). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53429-3.00004-1.

Santini, Z. I., Koyanagi, A., Tyrovolas, S., Mason, C., & Haro, J. M. (2015). The association between social relationships and depression: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 175, 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.049.

Sawyer, S. M., Azzopardi, P. S., Wickremarathne, D., & Patton, G. C. (2018). The age of adolescence. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 2(3), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1.

Schmid, M. (2018). PISA Australia in Focus Number 4: Anxiety. https://research.acer.edu.au/ozpisa/33.

Seiffge-Krenke, I. (2000). Causal links between stressful events, coping style, and adolescent symptomatology. Journal of Adolescence (Vol. 23, pp. 675–691). Elsevier Science. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2000.0352.

Silva, J. C. P., da, Cardoso, R. R., Cardoso, Â. M. R., & Gonçalves, R. S. (2021). Sexual diversity: A perspective on the impact of stigma and discrimination on adolescence. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 26(7), 2643–2652. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232021267.08332021.

Silverman, W. K., Greca, A. M., & Wasserstein, S. (1995). What do children worry about? Worries and their relation to anxiety. Child Development, 66(3), 671–686. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00897.x.

Solmi, M., Radua, J., Olivola, M., Croce, E., Soardo, L., Salazar de Pablo, G., Il Shin, J., Kirkbride, J. B., Jones, P., Kim, J. H., Kim, J. Y., Carvalho, A. F., Seeman, M. V., Correll, C. U., & Fusar-Poli, P. (2022). Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: Large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Molecular Psychiatry, 27(1), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7.

Spence, S. H. (1998). A measure of anxiety symptoms among children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(5), 545–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00034-5.

Stargell, N. A., Jones, S. J., Akers, W. P., & Parker, M. M. (2020). Training schoolteachers and administrators to support LGBTQ + students: A quantitative analysis of change in beliefs and behaviors. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 14(2), 118–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2020.1753624.

Steare, T., Gutiérrez Muñoz, C., Sullivan, A., & Lewis, G. (2023). The association between academic pressure and adolescent mental health problems: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 339, 302–317.

Storr, R., Jeanes, R., Rossi, T., & lisahunter. (2022). Are we there yet? (illusions of) inclusion in sport for LGBT + communities in Australia. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 57(1), 92–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/10126902211014037.

Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., Parkinson, J., Secker, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2007). The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-63.

Tiller, E., Greenland, N., Christie, R., Kos, A., Brennan, N., & Di Nicola, K. (2021). Mission Australia Youth Survey 2021. https://www.missionaustralia.com.au/publications/youth-survey/2087-mission-australia-youth-survey-report-2021/file.

Ustun, U., & Eryilmaz, A. (2018). Analysis of Finnish education system to question the reasons behind Finnish success in PISA. Studies in Educational Research and Development, 2(2), 93–114.

Wehmeyer, M. L., & Shogren, K. A. (2017). The development of self-determination during adolescence. Springer Netherlands.

Werner-Seidler, A., Maston, K., Calear, A. L., Batterham, P. J., Larsen, M. E., Torok, M., O’Dea, B., Huckvale, K., Beames, J. R., Brown, L., Fujimoto, H., Bartholomew, A., Bal, D., Schweizer, S., Skinner, S. R., Steinbeck, K., Ratcliffe, J., Oei, J. L., Venkatesh, S., & Christensen, H. (2022). ). The Future Proofing Study: Design, methods and baseline characteristics of a prospective cohort study of the mental health of Australian adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, e1954. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1954.

Wickens, T. D., & Keppel, G. (2004). Design and analysis: A researcher’s handbook. Pearson Prentice-Hall.

World Health Organisation (2021). Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2030.

Zhu, X., Haegele, J. A., Liu, H., & Yu, F. (2021). Academic stress, physical activity, sleep, and mental health among Chinese adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147257.

Zullig, K. J., Collins, R., Ghani, N., Patton, J. M., Huebner, S., E., & Ajamie, J. (2014). Psychometric support of the school climate measure in a large, diverse sample of adolescents: A replication and extension. The Journal of School Health, 84(2), 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12124.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the students and staff at the schools involved in the study as well as the Black Dog Institute volunteers who so generously gave up their time to assist with data collection. We would also like to thank the broader Future Proofing Study team at the Black Dog Institute who were involved in facilitating this study.

Funding

This study is part of the Future Proofing Study and has received funding from an NHMRC Project Grant awarded to HC (GNT1138405), an NHMRC Emerging Leader Fellowship awarded to AW-S (GNT1197074) and an NHMRC Fellowship (GNT 1155614) awarded to HC. Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and study design. Data collection was performed by AB, LB, KM and HF. Thematic analysis was undertaken by AB and LB with guidance from AW-S and MH and support from KM and HF. Data analysis and interpretation of results was undertaken by AB, KM and AW-S. The first draft of the manuscript was written by AB and all authors contributed to editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

This study is part of the Future Proofing Study and has ethical approval from the University New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (HC180836), the State Education Research Applications Process for the New South Wales Department of Education (SERAP2019201), and relevant Catholic Schools Dioceses across Australia.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Competing Interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Clinical Trial Registration

Full details of the trial are outlined in the ANZCTR registration (ACTRN12619000855123) protocol paper (Werner-Seidler, A. et al., 2020) and baseline cohort paper (Werner-Seidler et al., 2022).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bartholomew, A., Maston, K., Brown, L. et al. Self-Reported Concerns among Australian Secondary School Students: Associations with Mental Health and Wellbeing. Child Youth Care Forum (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-024-09804-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-024-09804-w