Abstract

Background

Postsecondary education can provide opportunities for students from traditionally hidden populations like those who have experienced foster care or homelessness. To assist these students, campus support programs (CSPs) provide a wide range of services and activities.

Objective

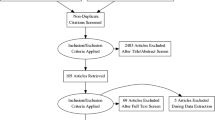

Evidence of the impact of CSPs is limited, and little is known about how students who were involved in CSPs fare at or after graduation. This study seeks to address these gaps in knowledge. Methods: This mixed-methods study surveyed 56 young people involved in a CSP for college students who have experienced foster care, relative care, or homelessness. Participants completed surveys at graduation, 6 months post-graduation, and one-year post-graduation.

Results

At graduation, over two-thirds of the students felt completely (20.4%) or fairly (46.3%) prepared for life after graduation. Most felt completely (37.0%) or fairly confident (25.9%) that they would get a job after graduation. Six months after graduation, 85.0% of the graduates were employed, with 82.2% working at least full-time. 45% of the graduates were enrolled in graduate school. These numbers were similar a year after graduation. Post-graduation, participants described areas of their lives that were going well, obstacles and hardships faced, changes they would like to see in their lives, and post-graduation needs. Across these areas themes were present in the areas of finances, work, relationships, and resilience.

Conclusions

Institutions of higher education and CSP should assist students with a history of foster care, relative care, and homelessness to ensure that after graduation, they have adequate money, employment, and support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Students who have experienced homelessness and non-traditional family care arrangements (e.g., foster care, relative care, and ward of the state status) are often hidden populations in postsecondary education settings and may experience lower rates of access to and success in college (U.S. Government Accountability Office [GAO], 2016). There is an abundance of recent research examining these students’ outcomes and experiences while in college (see Geiger & Beltran, 2017 for a review); however, very few studies have explored the impact of structured supports such as campus support programs (CSPs) and experiences after students graduate from college (Salazar & Schelbe, 2021). This study aims to better understand the experiences of students involved in a CSP after they graduate.

In public schools in the United States, over 1.3 million children are homeless (Blanco, 2022), and an estimated one in 10 youth aged 18 to 25 experience a form of homelessness over a 12-month period (Morton et al., 2018). Over 20,000 youth exit foster care at age 18 each year (US DHHS, 2021), and two-thirds will experience homelessness within 12–18 months after emancipating (Courtney et al., 2011). Experiences of instability, particularly homelessness during the transition to adulthood, can delay or prevent enrollment and matriculation into postsecondary education (Hernandez & Naccarato, 2010; Rosenberg & Kim, 2018).

Research has shown strong aspirations to attend postsecondary education among youth with a foster care background (e.g., McMillen et al., 2003; Smith, 2017) and youth who experience homelessness (Tierney et al., 2008). However, it is well-documented that youth often face obstacles to their education while in foster care, as do youth who experience homelessness (GAO, 2016). Both groups of youth have similar disruptions in their education due to frequent moves where they live (GAO, 2016). Additionally, with their life circumstances, these youth may be unable to engage in school and co-curricular activities. The chronic stress and childhood traumas associated with homelessness and entering foster care also contribute to educational outcomes.

To address the needs of youth in foster care and youth who experience homelessness, policies have been enacted to improve youths’ outcomes, including their educational outcomes. Seeking to help youth in care as they transition to adulthood, extended foster care provides youth housing and independent living services. Extended foster care can improve youth outcomes, including educational outcomes (Courtney & Hook, 2017; Okpych & Courtney, 2020). Educational training vouchers (ETVs) are another strategy that states use to support the educational outcomes of youth in foster care by providing funding to pursue postsecondary education. ETVs have been found to increase the enrollment and success in postsecondary educational programs of youth in foster care and those who have aged out of care (Geiger & Okpych, 2022; Hanson et al., 2023). A policy that states have used for youth in foster care and those who experience homelessness care is a tuition waiver program designed to reduce the financial burden of postsecondary education and promote access (Hernandez et al., 2017). Evidence shows tuition waivers contribute to student retention and graduation (Watt & Falkner, 2020).

Youth with a history of foster care or homelessness can be successful in postsecondary education. Studies have shown that these students’ resilience and self-reliance (Dumais & Spence, 2021; Miller et al., 2020; Morton, 2018; Samuels & Pryce, 2008), CSPs (Avant et al., 2021; Day et al., 2012; Geiger et al., 2017; Unrau et al., 2017), and social support (Day et al., 2012; Franco & Durdella, 2018; Jackson & Cameron, 2012; Katz & Geiger, 2020; Okpych & Gray, 2021; Skobba et al., 2018) can mitigate some of the challenges these student populations face while in college.

However, homeless students, students with a foster care background or non-traditional family care arrangements enroll in college at lower rates and often experience a number of barriers in accessing, persisting, and completing postsecondary education (e.g., Bender et al., 2015; Courtney et al., 2011; Zlotnick, 2009). Students who are homeless and students with a foster care background often experience high rates of absenteeism and school mobility, which may result in a loss of connections with peers and supportive adults (GAO, 2016). Further, students may experience mental health challenges (e.g., McMillen et al., 2005; Salazar, 2013), difficult family relationships (e.g., Avant et al., 2021; Kearney et al., 2019), and financial and housing hardships (Courtney et al., 2011; Day et al., 2021; Goldrick-Rab et al., 2017; Salazar, 2013; Skobba et al., 2022), which may lead to challenges in academic and social adjustment in college.

Campus support programs (CSPs) designed to support homeless students and students from non-traditional family backgrounds are emerging at higher education institutions across the United States. Given the overlap in needs experienced by these student populations, CSPs often serve both homeless students and students with a foster care background (Schelbe et al., 2019). CSPs typically offer various support services such as academic support, financial support, counseling, and housing assistance (Geiger et al., 2018; Randolph & Thompson, 2017) and have been shown to positively impact persistence in college (Okpych et al., 2020). Few studies, however, have examined the impact of CSPs (i.e., graduation rates) or their role in how students fare after graduation, likely due to programs lacking the capacity to collect and evaluate program components and outcomes (Schelbe et al., 2019). Several recent publications describe CSPs serving students who have experienced homelessness or foster care and provide qualitative accounts of their experiences as part of these programs (Cheatham et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2018). Cheatham and colleagues (2021) held focus groups with students and found that students in the REACH program at the University of Alabama benefited from tangible supports (e.g., food pantry), social and emotional support, and academic support (e.g., study groups).

Much of the literature focused on homeless students and students with a foster care background in college addresses college access and outcomes (e.g., enrollment, persistence, graduation) and student experiences during the transition to college and during college (e.g., barriers, supports). Studies have found that, in general, educational attainment can help improve coping skills during the transition to adulthood for those with a history of foster care (Häggman‑Laitila et al., 2019). However, little is known about student experiences after they graduate. One recent study examined factors associated with post-college success among 262 students with a foster care background and found that 67% of participants were working full-time, and 22% owned their home (Salazar & Schelbe, 2021). An examination of the factors associated with these post-college outcomes found that having students’ needs met as it relates to supportive relationships and community connections, life skills, and physical and mental health while in college were associated with positive post-college outcomes related to employment, financial stability, homeownership, job satisfaction, and mental health stability (Salazar & Schelbe, 2021). Another study comparing college students with a foster care background and those in the general population found similar outcomes in individual income and employment rates but significantly different outcomes in self-reported job security, household earnings, health, mental health, happiness, homeownership, and public assistance usage (Salazar, 2013).

Next to nothing is known about how students with a history of foster care or homelessness fare after graduation from college. This knowledge is needed, as graduation should not be considered the only outcome. Quality of life and life experiences after graduation must also be understood. Understanding how graduates who have a history of foster care or homelessness fare after they leave college has important implications for interventions before, during, and after college. With the knowledge of the challenges these graduates face, it is possible to intervene earlier to ensure that youth in foster care or with a history of homelessness can pursue postsecondary education and thrive after graduation. Additionally, there is much to be learned about the impact of CSPs on student outcomes after graduation and how students are faring in areas such as employment, economic stability, and social connections. This study aimed to fill gaps in the literature by addressing the following research question: 1) What are the experiences of college graduates who were involved in a campus-based support program six months and a year after graduation? Based on the existing literature, it was hypothesized that there would be evidence of graduates’ well-being and resilience as well as the presence of hardships.

Methods

This exploratory mixed methods study examined the experiences of graduates involved in the Unconquered Scholars Program, a CSP at Florida State University serving students who have experienced foster care, homelessness, relative care, or ward of the State status. Specifically, the study sought to understand graduates’ experiences in the year after leaving college.

Program Description

Established in 2012, the Unconquered Scholars Program at Florida State University is a CSP that provides various services promoting success to students who experienced foster care, homelessness, relative care, or ward of the State status. The Unconquered Scholars Program is a part of the Center for Academic Retention & Enhancement (CARE), which recruits, prepares, and supports first-generation students to succeed in college.

The Unconquered Scholars Program is a voluntary program provided at no cost to qualified students. Students in the program are called “Scholars.“

Scholars have access to programming specific to the Unconquered Scholars Program as well as at CARE and throughout the university. The Unconquered Scholars Program’s wide range of activities and services include: one-on-one advising; college life coaching; financial aid assistance and advocacy; computer lab and study suite; referrals to mental health counseling services; academic and skills workshops; volunteer opportunities; bi-weekly group meetings; and activities. Most Scholars also accessed services for first generation students, including summer bridge program, assemblies, academic advising, and tutoring services. The first Scholar graduated in 2015. As of 2021, there have been 292 Scholars. The six-year graduation rate for Scholars in the 2012 to 2016 cohorts is 84%, which is similar to the university’s six-year graduation rate.

Participants

The 97 Scholars who graduated between spring 2015 and fall 2020 were invited to participate in the study. The eligibility criteria for the study were to be part of the Unconquered Scholars Program and to graduate between spring 2015 and fall 2020. More than half (n = 54; 57.7%) of those eligible completed the survey at graduation. However, at the 6-month follow-up, only 20 Scholars (37.0%) participated. Only 22 Scholars (40.7%) participated in the one-year post-graduation survey. Twelve Scholars (22.2%) completed all three surveys.

Scholars who participated identified predominantly as Black/African American (53.7%; n = 29). Almost a fifth (20.4%; n = 11) identified as White/Caucasian, Non-Hispanic. A tenth of the Scholars (11.1%; n = 6) identified as having Latino/Hispanic ethnicity. Two Scholars identified as being multi-racial (3.7%; n = 2). Almost a fifth of Scholars (11.1%; n = 6) did not report any race or ethnicity. Two-thirds of the Scholars identified as female (n = 36; 66.7%), and nearly a quarter identified as male (n = 14; 25.9%). Four Scholars (7.4%) did not report their gender. The average age of Scholars at graduation was 21.9 (SD = 0.70).

To be qualified to be part of the Unconquered Scholars Program, students had to have experience in foster care, relative care, homelessness, or ward of the state status. Scholars selected the criteria that made them eligible. Thirty-two reported relative care (53.7%), 22 reported homelessness (40.7%), 10 reported ward of the state (18.5%), and 3 reported foster care (5.6%). Note, these numbers are more than 100% because Scholars selected more than one reason for being in the Unconquered Scholars Program. The demographics slightly changed in the six-month and one-year follow-up surveys (See Table 1).

Data Collection

The Unconquered Scholars Program staff recruited study participants by providing each Scholar with a link to an electronic survey at the end of their last semester in college. Follow-up emails were sent to invite and encourage them to complete the survey. Scholars were told that participation was voluntary and responses would be confidential. At the conclusion of the first survey, Scholars were asked to provide their emails to be contacted in six months and one year. Scholars received emails inviting them to participate in the follow-up surveys. In the third year of data collection, incentives to complete the surveys post-graduation were added to minimize attrition. Scholars were compensated $25 to complete the survey six months after graduation and $35 for the survey one year after graduation. The Florida State University Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. All study participants provided informed consent.

Data collection occurred from May 2016 through December 2021. Participants completed an online survey at graduation, six months after graduation, and one year after graduation. In addition to demographic information, each survey included questions focusing on Scholar’s lives and perceptions of their lives after graduation. Scholars were asked, “To what extent do you feel prepared for life after college? (1 = not at all; 2 = a little, 3 = somewhat; 4 = fairly; 5 = completely)” and “How confident are you that you will find a job you are suited for after graduation? (1 = not at all; 2 = a little, 3 = somewhat; 4 = fairly; 5 = completely).” The post-graduation surveys also included questions about their employment, enrollment in school, paying bills, and paying student loans. The following open-ended questions were asked during the follow-up surveys: What is going well in your life right now? What would you like to change in your life right now? What obstacles or hardships have you faced since graduating from college? What, if anything, do you need right now?

Analytic Strategy

Data included responses to Likert scale survey questions and open-ended questions, quantitative and qualitative data, respectively. Descriptive statistics were calculated for quantitative data, including demographic information about study participants (e.g., gender, race, ethnicity, and program eligibility), participants’ perceptions of preparation for life after graduation, ability to pay for expenses, ability to pay for student loans, employment status, enrollment status, and student loan repayment status at graduation, 6-months after graduation, and one year after graduation.

To analyze Scholars’ responses to open-ended questions, the first and fourth authors conducted a thematic analysis following the process outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006): (1) becoming familiar with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the report. The research team members independently read through participants’ responses to the open-ended questions and identified codes within the data. Then they met to discuss the codes and organized them into themes. Once themes were defined and named, the lead author selected exemplar quotes to integrate into the written description of each theme. The other research team member who had coded provided feedback. This approach allowed the identification of themes (patterns or meanings) within the data and the relationships among the themes. In the findings section, terms like “some” or “several” were used rather than direct counts, consistent with the recommendations of qualitative methodologists (e.g., Hannah & Lautsch, 2011; Sandelowski, 2001). Scholars’ words were used verbatim, including any punctuation and emphasis (e.g., written in all capital letters), to illustrate the themes from the data.

Results

At graduation, almost one out of five Scholars (20.4%; n = 11) indicated they felt completely prepared for life after graduation. More than two out of five (46.3%; n = 25) said they were fairly prepared. More than a quarter indicated they were somewhat (16.7%, n = 9) or a little prepared (13.0%, n = 7). Only two Scholars (3.7%) indicated they were not at all prepared for life after graduation. Over a third of the Scholars (37.0%; n = 20) said they were completely confident they would find a job. Over a quarter (25.9%; n = 14) reported feeling fairly confident, and more than a quarter (31.5%; n = 17) reported feeling somewhat confident. Only two Scholars said they were a little confident, and only one Scholar said they were not at all confident that they would find a job after graduation.

Post-graduation, all Scholars felt at least somewhat prepared for life after graduation. Most Scholars also felt at least somewhat able to pay their bills, although many did not report feeling confident in paying their student loans (see Table 2). Six months after graduation, most of the Scholars reported being employed (85%; n = 17), with most working full-time (70.6%; n = 12) or more than full-time (11.8%; n = 2). Approximately half of the Scholars were currently enrolled in school (45%; n = 9). One year after graduation, the numbers of Scholars working and enrolled in school were similar (see Table 3).

In responses to open-ended questions, Scholars described what life was like after graduation in terms of (1) what was going well, (2) what obstacles and hardships they encountered, and (3) what they needed and would like to change. The themes within these areas are described below. A year post-graduation, few Scholars shared anything in response to the prompt asking for anything else about their experience after graduation that they wished to share. However, those who did frequently mentioned feeling happy and pleased with their accomplishments. Some Scholars indicated that the first year after graduation had not been easy. One Scholar explained, “This year has been one heck of a journey, but I’ve learned a lot, a lot about myself and a lot about the world we live in. I must say each day I am growing, and that makes me happy.“ In many ways, this encapsulates Scholars’ descriptions of life after graduation. Throughout their responses, a consistent picture arose that Scholars were optimistic about parts of their lives going well, yet life after graduation was not without difficulties that could possibly be mitigated with assistance.

Areas Going Well

After graduation, Scholars described different parts of their life that were going well. Topics Scholars mentioned were related to work, school, stability, and relationships. Scholars often identified things going well across multiple domains. For example, one Scholar shared,

I am a full time student with a full time job. I am working to build my credit for the future. I have a new car and am building a relationship with my partner and juggling social, school, family, and personal growth. I have obtained in-state tuition and a assistantship for the upcoming semester which was my main goal so that I don’t continue to accrue debt.

Despite not being prompted to, besides positive experiences, Scholars also discussed challenges when asked about what was going well. A few Scholars discussed their resilience, sharing that while things were going well for them now, everything had not been easy since graduation.

Work and School

The most frequent response to what was going well after graduation was related to work or graduate school. Many Scholars indicated both work and school were going well. One Scholar shared, “I have a job at Wells Fargo that I work full time and I was accepted into graduate school.“ Another Scholar indicated, “My career, my educational experience, and my self-confidence has improved.“ One Scholar shared, “I am good at balancing being a full-time student and a full-time worker.“

Some Scholars highlighted specific accomplishments. For example, one mentioned being honored as the Employee of the Month. Another Scholar shared,

Right now, I have completed the first semester of my MSW program with high A’s. I signed a lease for my first ever apartment on my own in Tallahassee, and I have secured a part-time job as a personal trainer making $24 an hour while I work on my masters.

Scholars sometimes talked about elements of their job that they liked. For example, a Scholar emphasized their job was meaningful: “I really enjoy my job that I am working at. I feel that I was doing really fulfilling work.“ Several Scholars emphasized that they were earning enough money to provide for themselves and/or live on their own. One Scholar shared, “I am employed and able to provide for myself.“ Another Scholar shared, “I have a great job and I live by myself! Both things I’ve been praying for.“

Stability and Meeting Basic Needs

Some Scholars identified that what was going well was having stability and being able to meet their own basic needs. This often was connected to having a stable job. For example, one Scholar shared, “I have my own place to live alone, I can pay all of my bills, and I have a very stable job at a company that isn’t firing or furloughing.“ Stability was also connected to making ends meet. One Scholar explained, “I have a steady income and am able to afford all of my living expenses without stressing too much.“ Another Scholar explained, “I don’t really have to worry about shelter or food so that’s also nice.“ This emphasis on meeting basic needs arose across multiple Scholars’ responses.

Relationships

A couple of Scholars reported that their relationships with romantic partners, family, and friends were going well. One Scholar shared, “I’ve become serious with a great guy.“ Another Scholar explained: “I have a good support group around me and am getting along with my family.“ One Scholar who described that graduate school and working were going well also shared her relationships were going well,

I have reconnected with some of my really amazing girlfriends from college post-graduation, and we are all working on advancement in our education or careers. After graduation, I ended a toxic college relationship and took some time to myself to think about the developments I want in a long-term future partner. More recently, I started dating an emotionally intelligent, focused, and driven individual who is pursuing an MD-PhD in neuroscience. We are doing long-distance, but this works out perfectly for us since we both need space to pursue our educational goals.

Like this Scholar, another Scholar listed multiple aspects of life were going well and concluded with, “And I have a great social life with a bunch of friends.“

Resilience

While the question asked about what was going well, several Scholars spontaneously discussed difficulties they had encountered after graduation. These Scholars all stressed that they were doing better now and acknowledged their efforts and positive mindset in being where they currently were. One Scholar shared, “It’s going well as far as school. My financial situation and mental state could be stronger. I lost my primary caregiver who was my [grandma] and it’s been hard managing things on my own getting adjusted to a new place and losing someone so close to me.” One Scholar shared:

It’s going very well. Covid has brought a string of annoying situations but I have been able to navigate them all. The hurricane storm surge flooded my car but I was able to finance a certified preowned car. I got a small bonus and raise at my job this year. I had COVID but recovered easily and quickly.

Another Scholar shared:

To be completely honest with you, everything is going well right now. I sit and think about people who do not have half of the things I have, and I become grateful for what I do have. I think it’s easy to forget and so things are going well. I just finished my second semester in grad school. I have a job that is helping me pay my bills, I have food on the table, well sometimes when I feel like cooking. My car is not giving me any hassles, and my friends and family are safe. If you were to ask me at the beginning of the semester, I would say my life is hell. I went through a depression losing a very close friend of mine, I wasn’t eating, nor sleeping. I became afraid to go home because I knew had I went home I would cry my eyes out. But I put my pride to the side and went to seek help.

One Scholar who described being homeless in responses to later questions explained, “I would say that I have a roof over my head, food in the cabinets, a car, and I am employed if we are looking at the positives.” Within each of these Scholar’s responses is evidence of resilience and overcoming challenges.

Obstacles and Hardships

Scholars identified areas where they faced obstacles and hardships after graduation. The themes discussed by participants included money, adjusting and uncertainty, “adulting tasks,” relationships, career, and homelessness. Frequently, scholars described having obstacles or hardships across multiple domains and occurring simultaneously. One Scholar shared, “I have struggled relationship wise. I have struggled with budgeting. I have struggled with self-esteem.” There were some differences in how common the themes were during each follow-up period. Adjusting and uncertainty; “adulting tasks;” and career were frequently responses at 6-month follow-up. At the one-year follow-up, Scholars identified relationships and homelessness as problems they experienced post-graduation.

Money

Scholars indicated having problems after graduation with money. Frequently, Scholars stressed their problems with money were due to inadequate income and not having strong money management skills. One Scholar shared, “I have had trouble with money and money management.” Another Scholar shared, “Learning to maintain all of my finances on my own and have control over my debt.” One Scholar shared, “Balancing all of my bills and still saving a good amount.” Another Scholar shared, “Filing/paying taxes - there is still so much I don’t know. I have struggled a bit financially.” A few students mentioned hardships with paying student loans and debt.

Adjusting and Uncertainty

Adjusting to changes after graduation was a difficulty that Scholars discussed. This was the most common theme at the six-month follow-up. One Scholar shared that the challenge was “Just adjusting to the real world.” Another One Scholar explained, “Adjusting to life after college. Starting over with friendships, networking. Finding my niche.”

Some adjusting was connected to moving, employment, or graduate school. One Scholar shared, “Moving to a new state with very little money. Starting my first real job and getting acclimated to living in a new area, not knowing anyone, and experiencing home sickness for the first time.” Another Scholar shared, “Loosing someone close to me adjusting to being in a different state and away from family and friends.” One Scholar shared, “Adapting to graduate school curriculum and balancing a job.” Another Scholar described, “Trying to get situated in pharmacy school, figuring out to pay for rent and my bill’s and how I could get to school.”

Scholars expressed that there was the challenge of uncertainty and planning after they graduated. One Scholar shared, “I have been a little unsure of the next step.” Another Scholar shared that an obstacle was “… deciding to come back to school.” Other Scholars mentioned uncertainty within the process of applying to graduate school and making plans going forward.

Adulting Tasks

Scholars indicated having difficulty navigating life skills and adult responsibilities or “adulting tasks” as one Scholar described them. This Scholar shared,

I don’t think FSU taught me or prepared me for adulting tasks. My insurance through FSU has expired. I have been having a hard time figuring out how to find affordable health insurance and [I] currently do not have health insurance. I am also struggling to make my student loan payments.

Another Scholar shared that having problems with adult responsibilities negatively impacted them: “I lost my first job opportunity because of something wrong with my [university] transcripts. I’m doing much better though.” Another Scholar explained, “At first I felt overwhelm with having different type of responsibilities but i remember the tools and skill that I learn during my freshmen year in college.” Finding balance and managing adult responsibilities was a challenge, as one Scholar explained, “Balancing my time with work, school, and rest.”

Relationships

Many of the obstacles and hardships that Scholars experienced in the year after graduation were related to relationships. This was especially a prevalent theme at the one-year follow-up, where it was the most common theme. Some Scholars mentioned specifically not having friends close by. One Scholar shared, “…moving to a new state on my own and making friends was hard at first.” Another Scholar explained, “Not having my friends near me has been difficult and lonely.”

Scholars described challenges navigating relationships with family. One Scholar shared,

The hardest thing I have to face since graduating from college is learning how to protect myself from family members, who think because I graduated and found a good job that I must help them financially. It is a stressful and trying situation because you want to be helpful but certainly not naive.

Scholars also identified troubles with family members as negatively impacting their living situations and mental well-being.

One of the hardships identified related to relationships was the death of a loved one or losing a relationship. One Scholar shared about the death of their grandmother, who had been their primary caregiver. Another Scholar explained, “Losing my close friend going into a deep depression.” Another Scholar described their hardship as “Loosing a beloved relationship.”

Career

At the six-month follow-up, some Scholars discussed problems with finding a career or job and being satisfied with their work. One Scholar shared their challenge: “Feeling satisfied with a career and planning for a good future career in life.” Another Scholar explained that the challenge with a career was linked to the COVID-19 pandemic: “Actually finding a position where my degree matters. It’s kind of hard to find a hospitality job with not that much experience and also a pandemic. I lucked out with a job at the casino so it’s a start in the right direction.”

Homelessness

At the one-year follow-up, three Scholars specifically mentioned being homeless or “unsheltered.” Several other Scholars mentioned needing to move back in with family, which can also be conceptualized as housing instability and could be considered homelessness depending on the circumstances.

Also, only at the one-year follow-up, several Scholars described having difficulties with their living situations with family. One Scholar explained, “Moving back home was more of a psychological challenge for me, especially during COVID, since it brought on feelings of failure or not being where I thought I should be.” Another Scholar shared, “living back at home with my 4 siblings and parents.” Another Scholar explained the hardship was “Trying to move out of my moms house.”

Needs and Changes

Scholars were asked what they would change in their lives and what they needed. Their responses illustrate areas in their lives where there were wants, concerns, dissatisfaction, or potential for improvement. Money was the most common theme, as Scholars stressed they did not have enough and wanted to be able to save and pay off student loans. Scholars’ responses were also in the following categories: employment; living situations; well-being; and mentors, support, and relationships. Some Scholars explicitly stated they had no current needs, although they previously mentioned things they wished would change. Scholars sometimes discussed changes they desired or things that they needed across multiple domains, as one Scholar listed multiple needs: “More money, Students loans to be paid off, Physical fitness.”

Money

Scholars indicated that they would like to change their financial circumstances and that they needed more money. Scholars shared they did not earn enough money. One Scholar explained, “I would like to change living pay check to pay check.” One Scholar shared, “Currently I would like to change my financial situation and having to work two jobs.” Another Scholar responded, “My credit score and financial stability.” Another Scholar shared, “Make more money and have less bills.” Another Scholar shared, “… I would like to have a larger savings account. It would also be nice not to have student loans from undergrad hanging over my head.” One Scholar explained, “My financial status. It is difficult paying for an apartment and other bills when I am not working.” One Scholar shared as a goal, to “get my rent to be 1/3 of my pay instead of 1/2. I want to do this by getting a pay raise and rising in the company.”

One Scholar described their need as having “More money to pursue my education and student loan forgiveness.” Another Scholar explained they needed “Better financial stability and scholarships and funding for school.” A couple of Scholars mentioned the issue of paying for graduate school and student loans. One Scholar shared, “It would be nice to have scholarship for the Masters and not having to pay loans, but other than that I am good.” Another Scholar explained their need for more money was to pay for student loans and health insurance: “Health insurance and a higher paying job so I can afford health insurance and my student loan payments.”

Several Scholars specifically mentioned wanting more savings. One Scholar shared, “Have more savings. My apartment and bills are probably making up 70% of my total spending.” One Scholar shared, “Savings. I can’t seem to have enough money left over each month to make much of a positive impact.” Another Scholar shared, “Students loans to be paid off.” A few Scholars indirectly indicated that they needed money through sharing that they needed a car or wanted to live by themselves.

Some Scholars described needing help with financial literacy skills, such as learning about credit, homeownership, budgeting, and loans. One Scholar mentioned needing “financial literacy.” Another Scholar shared wanting assistance to buy a house. One Scholar explained they needed “life skills on student loans, saving for a home, etc.”

Employment

Some Scholars indicated they wanted to find another job that paid better or was a better fit for them. One Scholar stated, “I will like to get a better paying job but the schedule that I have right now is perfect for school. I wish I could find another job with the same schedule and higher pay.” Another Scholar shared, “I would like a more stable job with better income and to move to a better area.” One Scholar explained, “I need to find a job that is related to my field.” Another Scholar said they wanted a full-time job so they could stop doing freelance work. One Scholar shared wanting to leave a “toxic situation” at work. Several Scholars simply indicated they needed a job.

Living Situation

Changing living situations was a theme among Scholar’s responses. One Scholar shared, “My living situation. I wish I was financially able to live on my own.” Another Scholar elaborated on why they wanted to change their living situation:

My living conditions would be the biggest thing. It’s kind of hard being in a three bedroom house with 8 people. There’s no sense of privacy but at the same time it’s not something so bad that I can’t put up with it. It could be worse.

Another Scholar indicated that they wanted to move: “I would like to change my living arrangements and city of residence. I want to move to another city/state.”

Well-Being

Scholars discussed wanting to improve their well-being in the areas of their health, mental health, and personal growth. This was the theme most prevalent at the one-year follow-up. One Scholar said they wanted to lose weight. Another Scholar explained, “Overall health and fitness.” Another Scholar shared, “I would like to change my eating style. I became healthy about a year and a half ago, but stopped going to the gym and eating right for some time now. I’m in the process of working on it.”

Scholars also indicated wanting to focus on their mental well-being. One Scholar shared, “I would like to be able to breath a little and take a break, but I can’t afford to.” One Scholar shared, “working 40 hours a week while going to grad school is tough If I can get a week break for my mental state that would be nice.” Another Scholar shared wanting to address their mental health: “My depression and outlook on things. I am just really unhappy with my employment and the toxic situation is spilling over into my personal life.” One Scholar explained, “I would like to become more focused on mindfulness and my physical health.” Another Scholar shared “my negative mind set.” One Scholar who described wanting “patience and endurance.” A couple of Scholars indicated that they wanted more confidence.

One Scholar was specific about how to improve their well-being: “I would like to manage my time a little better so I can get more exercise each day and sleep earlier at night.” Another Scholar shared, “Also, because of the second job, lack of sleep, and stress, I would like to change how I am seeing the world and dealing with it. My moods have become unhinged.”

Mentors, Support, and Relationships

Scholars identified wanting mentors, better support, and improved relationships. Scholars stressed needing people to assist with making decisions in career and graduate school. One Scholar explained, “Right now I need career guidance and to find an entry-level job to give me experience that I can take into the workforce after I graduate with my MSW.” Another Scholar wanted “help…how to excel in my career.” One Scholar shared a need for “Mentorship in a field that interests me so that I can find a career that just right for me.” Another Scholar identified needing a “Mentor in my profession/ outside my profession.” One Scholar broadly described their need for guidance, like a mentor could provide: “Someone to help me center my focus and figure out the next step.” One Scholar shared their need was “Learning how to manage my life being a full-time student and having a full-time job.”

Several Scholars mentioned wanting more support, specifically around navigating life skills. This was best captured by a Scholar who explained,

Right now, I’m okay. Probably, I need help understanding filling out important adult stuff like getting my insurance and things of that nature. I’ve been putting it off is it’s a little intimidating, especially if you don’t have the support system to help out.

Scholars were clear that having people in their lives that supported them was something they needed.

Having relationships was something that Scholars discussed wanting to change. A Scholar who had moved out-of-state after graduation shared, “A larger friend base in [city]. Needing to make time to build a better support base here.” One Scholar shared wanting to change “My habit of isolating myself and being more social. Another Scholar explained, “Better my relationships and social skills.” One Scholar identified a specific relationship they wanted to change, “Right now, I would like my relationship with my mother to improve since graduation; it been a little tense.”

No Current Needs

While all Scholars identified things that they would change, several Scholars stressed that they did not have any current needs. One Scholar shared, “I don’t need anything at the moment. I am working for things that I want right now.” Another Scholar said, “Right now i feel like everything is going really well.” Another Scholar responded, “Honestly, I think I’m good right now.” One Scholar shared, “I would say I have everything I need to live a good life right now.”

Discussion

This study addresses a significant gap in the knowledge about how students with a history of foster care or homelessness who were involved in a CSP fare after graduation. At graduation, most Scholars expressed confidence in feeling prepared for life after graduation. Six months and one year post-graduation, this confidence continued. There is evidence of their successes and resilience, and there are indications of concerning challenges after graduation. While many Scholars were working and/or attending graduate school, there were also those who were experiencing homelessness. Even for some of those who were working full-time, many were living “paycheck to paycheck” and unable to save. While Scholars identified relationships as an area of their lives going well, they also considered relationships a hardship and an area where they had unmet needs. Scholars described the support they had post-graduation and desired more, specifically in the context of mentoring and helping navigate adulthood. Iterations of the issues of employment, graduate school, money, and support were across all of what Scholars shared were going well, obstacles and hardships, and any changes or needs they identified having.

After graduation, most Scholars were employed, largely in full-time positions. And most Scholars felt confident in their ability to pay their bills and meet basic needs. Despite their confidence and employment, some Scholars disclosed they faced financial difficulties. Previous research has found youth who aged out of care have lower rates of employment (Courtney & Dworsky, 2006; Hook & Courtney, 2011) and lower earnings than their peers (Naccarato et al., 2010; Okpych & Courtney, 2014) found that completing a four-year degree makes the rates of employment of those with a history of foster care and their peers the same and reduces a persistent gap in earnings. They hypothesized that income disparities continue due to housing instability, mental health problems, education instability, and early parenting. Previous research has found that youth in foster care who experience homelessness are more likely to encounter problems with employment and higher education (Rosenberg & Kim, 2018). Housing has also been consistently identified as a challenge by students with foster care experience attending college (e.g., Dworsky et al., 2013; Salazar et al., 2016; Hernandez & Naccarato, 2010). It is hypothesized that instability in housing—a basic need—disrupts other life activities (e.g., going to school and working; Rosenberg & Kim, 2018). The current or history of housing instability of some Scholars likely impacted their employment or graduate school.

Approximately half of the Scholars were enrolled in graduate school after graduation. In some regards, this is not completely surprising considering the current trend of an increase in students pursuing advanced degrees, including greater increases for racially minoritized groups (Zhou & Gao, 2021). Nevertheless, it may be somewhat unexpected as parents’ education impacts graduate school enrollment (Mullen et al., 2003), and Scholars are first generation students. Additionally, research has found college graduates lower socio-economic levels are less likely to attend graduate school (Posselt & Grodsky, 2017). There is dearth of research on young adults with a history of foster care or homelessness and their decisions to attend graduate school and their graduate school experiences (Sensiper & Barragán, 2017). However, as research has documented additional challenges faced by graduate students who are first generation (Roksa et al., 2018), from lower socio-economic levels (Ostrove et al., 2011), or from racially minoritized groups (Brunsma et al., 2017; Twale et al., 2016) and many students with a history of foster care or homelessness have these identities, it is likely that students with a history of foster care or homelessness face additional challenges while in graduate school. This is consistent with what is seen with the Scholars.

Money was a challenge for Scholars post-graduation. They described earning inadequate incomes and being overburdened with expenses, including student loan payments. Student loans continue to be a burden for many young adults after college; however, Scholars’ student loan debt is especially concerning given that Florida has a tuition waiver and scholarships available to students with a history of foster care or homelessness. Tuition waiver programs are designed to reduce the financial burden of postsecondary education and promote access (Hernandez et al., 2017), yet waivers do not provide for living expenses. As such, students may still rely on student loans and income from employment to be able to attend college.

Scholars discussed difficulties with saving money, filing taxes, making financial decisions, and understanding investing. Independent living skills programs for youth in foster care in the U.S. typically include programming regarding money management and financial literacy, yet many young adults with foster care experience continue to experience challenges in obtaining economic stability and mobility (Katz & Courtney, 2015; Thompson et al., 2018). This is likely in part due to the lack of safety net, generational wealth, and social capital for many young adults with foster care backgrounds (Okpych & Courtney, 2014). A recent study exploring factors associated with post-college success showed that satisfaction with one’s financial situation after college was associated with having budgeting and money management skills as well as social support (Salazar & Schelbe, 2021).

Scholars identified strong, supportive relationships with peers, family, and caring adults, which served as a promoter of success, which is also consistent with previous research showing the importance of social support (e.g., Franco & Durdella, 2018; Häggman-Laitila et al., 2019; Katz & Geiger, 2020), CSPs (e.g., Avant et al., 2021; Unrau et al., 2017), and supportive adults while enrolled in college and after college (Salazar & Schelbe, 2021). Scholars’ value of support and relationships was evident. A concern Scholars consistently mentioned was feeling isolated and lacking adequate support. They stressed that in the first year after graduation, they needed a stronger support system and wanted relationships. Specifically, Scholars desired mentors and others they could rely on for social and tangible support.

Considering the statistics about college enrollment and graduation rates of students with a history of foster care or homelessness (e.g., Bender, et al., 2015; Courtney et al., 2011; Zlotnick, 2009), Scholars graduating is testimony to their ability to overcome hardships. Their resilience was evident in the year after graduation as well. Some of the Scholars reflected on their ability to overcome challenges, like the student who shared being able to navigate “a string of annoying situations” faced after graduation. Several studies point to youths’ resilience and self-reliance as instrumental in their ability to navigate life’s obstacles and complete postsecondary education (e.g., Dumais & Spence, 2021; Miller et al., 2020; Morton, 2018, Samuels & Pryce, 2008). This resilience allowed them to persist despite loss, disappointment, and setbacks.

While substantial evidence of Scholar’s resilience existed, there was also evidence that they were facing some significant challenges, including uncertainty and instability, and experiencing considerable stress. This is consistent with previous research that has found that students with a history of foster care or homelessness experience difficulties in college (e.g., Day et al., 2021; Salazar et al., 2016; Skobba et al., 2022). Many of the challenges identified by Scholars were consistent with past studies that showed challenges with financial stability, housing, and relationships that seem to persist from adolescence into adulthood (e.g., Courtney et al., 2011; Dworsky et al., 2013; Hook & Courtney, 2011) but manifested themselves in different ways due to the changes in responsibility, experience, and circumstances. Young adults are going through a significant phase of development that is focused on establishing independence and identity and self-development. Many young adults have had little guidance or positive role modeling as it relates to “adulting” behaviors that involve financial and social stability, seeking and obtaining resources and support, and are often experiencing work and responsibility for the first time beyond college.

For some Scholars, uncertainty and instability were present at graduation. The first survey was administered in the final semester, mere weeks before graduation, yet some Scholars had no plans. Uncertainty was also present in not knowing something (e.g., applying to graduate school, budgeting, “adulting tasks”). Several Scholars described feeling as though they were “starting over” and having to re-adjust their lives to accommodate working versus being a student; managing income and expenses outside of educational expenses and sources of funding; and establishing and managing relationships within different contexts. These adjustments often take time and require additional support and guidance, which many youth with a history of foster care or homelessness may not have (e.g., Courtney et al., 2011). However, Scholars in the study also shared needs that are similar to their same-aged peers that have not experienced foster care or homelessness, such as higher wages, improved health insurance, and affordable housing.

Scholars explained having instability mainly as it relates to employment and living situations. Within their first year after college, some Scholars had moved more than once or wanted to move. Others experienced instability in their jobs and graduate school. A year after graduation, Scholars were often looking for another job already and those who continued their education were planning their transition after graduating from graduate school. Post-graduation, many Scholars indicated still having to plan and figure out what life would be like after graduation. While some of this instability is normative among young adults, it is also possible that young adults with experience with foster care or homelessness may have difficulty establishing stability given their experiences of instability before and during college.

It should be noted that the COVID-19 global pandemic brought uncertainty and instability to all, and Scholars likely felt this more acutely when the university closed campus and transitioned to everything being virtual. Scholars did not necessarily have other housing options and family to rely upon when the university closed the residence halls. Resources and supports that Scholars had relied upon (e.g., suite, computer labs, food pantry) were unavailable during the early part of the pandemic when campus was closed. While CSP staff and the university worked with Scholars to meet their needs, the changes likely were stressful. Another source of stress during the campus closure was the isolation that Scholars felt, perhaps more acutely, as many did not have family to live with during the shelter-in-place orders.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. The most important limitation to note is the high attrition rate. This likely occurred due to study participants being members of groups which are recognized as hard to reach, and data were collected during a major life transition as they graduated from college. Even after the protocol was changed to add incentives for completing the surveys at the six-month and one-year points after graduation, only 37.0% of Scholars completed a second survey, and only 22.2% completed all three surveys. There is no way to know if the Scholars who did not complete the follow-up surveys share the experiences of the Scholars who completed the surveys. It is possible that those who did not complete the surveys were better off than those who did. However, even if all of the Scholars who did not participate in the follow-up surveys were thriving without any concerns, there were still Scholars who completed the surveys who experienced hardships post-graduation.

Due to the sample size and attrition rates, no analysis of subgroups of Scholars were conducted. Thus, it is unknown if there were differences among Scholars by gender, race/ethnicity, or the reasons they were qualified to be a Scholar. As previous research with young people with a history of foster care has found great heterogeneity and differences by subgroups, it is plausible that within group differences existed. Understanding these differences is important and should be prioritized in future research.

As data were not collected from graduates who were not involved in the Unconquered Scholars Program, it is not possible to conclude how Scholars fare as compared to their peers not in the CSP or without experience with foster care, homelessness, relative care, or ward of the State status. Due to the sample size, it was also impossible to make comparisons among groups of Scholars (e.g., different genders, races, eligibility for involvement).

The findings from this study must be considered in context. They are specific to the Unconquered Scholars Program at Florida State University and not generalizable to all CSPs. Also, the Unconquered Scholars Program services changed during data collection. For example, after the study began, the Unconquered Scholars Program started providing financial literacy workshops, and Spring 2020 programming changed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. All university and CSP functioning became virtual for about a year. The sample contained students who graduated in Spring 2020, Summer 2020, and Fall 2020; thus, some students had their last one to three semesters only having virtual options. Additionally, these students and the graduates of 2019 had their first year after graduation during a global pandemic. The stress, uncertainty, and chaos of the pandemic likely impacted Scholars’ experiences after graduation.

Study Implications

Understanding the experiences of graduates who have a history of foster care or homelessness after they leave college has important implications for before, during, and after college. With the knowledge of the challenges these graduates face, it is possible to intervene those with a history of foster care or homelessness are able to pursue postsecondary education and thrive after graduation. Based on the Scholars’ suggestions and the areas where they encountered hardships, there are three areas that should be prioritized by institutions of higher education, social service agencies, and policymakers to help Scholars after graduation with (1) money, (2) employment and graduate school, and (3) support. Efforts should be made to ensure that Scholars have enough money after graduation. Much of this is about earning enough and managing their money. It is also about taking on student loan debt, access to scholarships for graduate school, and credit scores. While students with a history of foster care or homelessness may receive tuition waivers and other financial support, they still may amass significant student loan debt to provide living expenses. Education for these students about student loans is essential, especially considering that many are first generation students and may not have family members giving guidance. CSP may help provide the needed information.

In terms of employment, students need access to livable-wage jobs that align with their skills and interests. To get these jobs, they would benefit from career planning and assistance with their job searches. Understanding potential career paths, including confirming that their education aligns with their career goals is important. Support should be provided in the form of emotional support and informational support. Scholars need people who provide encouragement and can share information, help problem-solve, and teach skills. It would be beneficial for students to know their eligibility for benefits and assistance, such as coverage under the Affordable Care Act or tax credits for which they qualify. While Scholars are in college, CSP can assist with this. Students also need assistance applying to graduate school and navigating graduate school once enrolled. A CSP explicitly designed for those planning to attend graduate school and graduate students could address these issues (Sensiper & Barragán, 2017).

Efforts to help students with a history of foster care or homelessness may primarily come from CSPs; however, colleges and universities have responsibilities that extend beyond the CSP. There are a number of campus units that could collaborate with CSPs to provide additional resources and support to students, such as student affairs, financial aid, and academic support services while students are enrolled to prepare for life after graduation (Geiger et al., 2016). Further, community and state agencies could also work alongside CSPs and campus units to provide information about resources and services. Alumni associations and other programs that bridge student experiences on and off campus can assist with engaging graduates and building their social networks.

The various systems (e.g., child welfare, social services) students continue to engage with should examine policies and programs to ensure accessibility and usefulness for students who experience foster care or homelessness. This can be done by assessing students’ social and financial needs and considering stipends, programming, and/or housing options. Administrators within these systems (e.g., child welfare, secondary education, postsecondary education, health, and mental health care systems) should prioritize collaborative efforts to support student needs before, during, and after college. Professionals working within these systems should have the knowledge and confidence to provide services when available and to make referrals and connections for students before and as needs arise. This requires the systems to share information and offer training and resources to staff and students about what is available.

Considering policy, state legislatures should consider policies that promote and support postsecondary education for those with a history of foster care or homelessness. For example, tuition waivers and reduced fees for state universities and colleges for these students can help alleviate financial burdens while in college and reduce student loan expenses post-graduation (Hernandez et al., 2017). Financial stipends, scholarships, and priority housing for students with a history of foster care or homelessness, who may have less family support than their peers, are other option that are promising in promoting success for students (Hernandez & Naccarato, 2010). Students also need information about various financial, social, academic, and housing opportunities. This information could be presented on an institution’s website, offered through the CSP or an academic coach, and should be accessible to students and their supports (e.g., counselors, teachers, foster parents, community agency staff) as well as institutional unit staff (e.g., financial aid, admissions, recruitment, faculty, administration).

Professionals working with youth in foster care or who are experiencing homelessness should inform the youth as well as their caregivers that support will be available and direct them to where the information can be found. Based on the growing evidence of how youth in foster care benefit from extended foster care (Courtney & Hook, 2017; Okpych & Courtney, 2020) and ETVs (Geiger & Okpych, 2022; Hanson et al., 2023) and both youth in foster care or with a history of homelessness have improved educational outcomes with tuition waivers (Hernandez et al., 2017; Watt & Falkner, 2020), these initiatives should continue to be funded so that youth enroll in and graduate from postsecondary education.

Additional research is needed about CSPs and postsecondary students who experienced foster care or homelessness. This study is one of the first to consider how students with a history of foster care or homelessness fare after they graduate. Study participants offered their own experiences about life after graduation. Future research should focus on short- and long-term outcomes after graduation in various domains of adjustment (e.g., employment, social, financial, health, and well-being). Researchers should examine potential differences among college majors and career choice. More research is needed to understand the debt accrued by students with a history of foster care or homelessness. It is important to determine the effectiveness of CSP and identify best practices. Research should also consider ways that each system (e.g., child welfare, education) can play a role in better preparing students for life post-graduation. Additionally, studies should examine the value of supportive adults in promoting the well-being of postsecondary students and graduates. This study found that a number of students involved with this CSP were returning to graduate school. More research is needed about the graduate school experiences of students with a history of foster care or homelessness as it relates to their motivation to enroll, graduation outcomes, and experiences while enrolled in graduate programs.

Conclusion

Postsecondary education can be transformative and create opportunities for many, particularly those from underrepresented groups in higher education. This has driven the prioritizing postsecondary education of students with a history of foster care or homelessness. It is important to understand theses students’ experiences both during their time in college and after graduation. To enroll, attend, and graduate from college, Scholars involved in the Unconquered Scholars Program displayed ample evidence of their successes and resilience, overcoming obstacles and hardships. As Scholars prepared to graduate, most had post-graduation plans and expressed confidence in how they would fare after college. Life post-graduation contained multiple areas where life was going well, including work and school, meeting their needs, and relationships. Nevertheless, it was not without challenges for Scholars, and Scholars identified their needs for improvements related to money, employment, living situations, well-being, and mentoring, support, and relationships. Addressing these needs and better preparing students can help to increase their success and well-being after graduation.

References

Avant, D. W., Miller-Ott, A. E., & Houston, D. M. (2021). I needed to aim higher:” former foster youths’ pathways to college success. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(4), 1043–1058.

Bender, K., Yang, J., Ferguson, K., & Thompson, S. (2015). Experiences and needs of homeless youth with a history of foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 55, 222–231.

Blanco, M. (2022). States build support for students who are homeless.National Association of State Boards of Education, 29(1). https://www.nasbe.org/states-build-support-for-students-who-are-homeless/

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Brunsma, D. L., Embrick, D. G., & Shin, J. H. (2017). Graduate students of color: Race, racism, and mentoring in the white waters of academia. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 3(1), 1–13.

Cheatham, L. P., Luo, Y., Hubbard, S., Jackson, M. S., Hassenbein, W., & Bertram, J. (2021). Cultivating safe and stable spaces: Reflections on a campus-based support program for foster care alumni and youth experiencing homelessness. Children and Youth Services Review, 130, 106247.

Courtney, M. E., & Dworsky, A. (2006). Early outcomes for young adults transitioning from out-of‐home care in the USA. Child & Family Social Work, 11(3), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2006.00433.x.

Courtney, M., Dworsky, A., Brown, A., Cary, C., Love, K., & Vorhies, V. (2011). Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at age 26 Chicago, IL: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

Courtney, M. E., & Hook, J. L. (2017). The potential educational benefits of extending foster care to young adults: Findings from a natural experiment. Children and Youth Services Review, 72, 124–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.09.030.

Day, A. G., Smith, R. J., & Tajima, E. A. (2021). Stopping out and its impact on college graduation among a sample of foster care alumni: A joint scale-change accelerated failure time analysis. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 12(1), 11–39.

Day, A., Riebschleger, J., Dworsky, A., Damashek, A., & Fogarty, K. (2012). Maximizing educational opportunities for youth aging out of foster care by engaging youth voices in a partnership for social change. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(5), 1007–1014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.02.001.

Dworsky, A., Napolitano, L., & Courtney, M. (2013). Homelessness during the transition from foster care to adulthood. American Journal of Public Health, 103(S2), S318–S323. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301455.

Dumais, S. A., & Spence, N. J. (2021). There’s just a certain armor that you have to put on”: Navigating college as a youth with foster care experience. Child Welfare, 99(2), 135–256.

Franco, J., & Durdella, N. (2018). The influence of social and family backgrounds on college transition experiences of foster youth. New Directions for Community Colleges, 2018(181), 69–80.

Geiger, J. M., & Beltran, S. J. (2017). Readiness, access, preparation, and support for foster care alumni in higher education: A review of the literature. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 11(4–5), 487–515.

Geiger, J. M., Cheung, J. R., Hanrahan, J. E., Lietz, C. A., & Carpenter, B. M. (2017). Increasing competency, self-confidence, and connectedness among foster care alumni entering a 4-year university: Findings from an early-start program. Journal of Social Service Research, 43(5), 566–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2017.1342307.

Geiger, J. M., & Okpych, N. J. (2022). Connected after care: Youth characteristics, policy, and programs associated with postsecondary education and employment for youth with foster care histories. Child Maltreatment, 27(4), 658–670. https://doi.org/10.1177/10775595211034763.

Geiger, J. M., Piel, M. H., Day, A., & Schelbe, L. (2018). A descriptive analysis of programs serving foster care alumni in higher education: Challenges and opportunities. Children and Youth Services Review, 85, 287–294.

Geiger, J. M., Hanrahan, J. E., Cheung, J. R., & Lietz, C. (2016). Developing an on-campus recruitment and retention program for foster care alumni. Children and Youth Services Review, 61, 271–280.

Goldrick-Rab, S., Richardson, J., & Hernandez, A. (2017). Hungry and homeless in college: Results from a national study of basic needs insecurity in higher education. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/83028/HungryAndHomelessInCollege.pdf

Häggman-Laitila, A., Salokekkilä, P., & Karki, S. (2019). Young people’s preparedness for adult life and coping after foster care: A systematic review of perceptions and experiences in the transition period. Child & Youth Care Forum, 48(5), 633–661.

Hannah, D. R., & Lautsch, B. A. (2011). Counting in qualitative research: Why to conduct it, when to avoid it, and when to closet it. Journal of Management Inquiry, 20(1), 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492610375988.

Hanson, D. A., Pergamit, M., Tucker, L. P., Thomas, K. A., & Gedo, S. (2023). Do education and training vouchers make a difference for youth in foster care? Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-022-00896-8.

Hernandez, L., Day, A., & Henson, M. (2017). Increasing college access and retention rates of youth in foster care: An analysis of the impact of 22 state tuition waiver programs. Journal of Policy Practice, 16(4), 397–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/15588742.2017.1311819.

Hernandez, L., & Naccarato, T. (2010). Scholarships and supports available to foster care alumni: A study of 12 programs across the US. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(5), 758–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.01.014.

Hook, J. L., & Courtney, M. E. (2011). Employment outcomes of former foster youth as young adults: The importance of human, personal, and social capital. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(10), 1855–1865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.05.004.

Huang, H., Fernandez, S., Rhoden, M. A., & Joseph, R. (2018). Serving former foster youth and homeless students in college. Journal of Social Service Research, 44(2), 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2018.1441096.

Jackson, S., & Cameron, C. (2012). Leaving care: Looking ahead and aiming higher. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(6), 1107–1114.

Katz, C. C., & Courtney, M. E. (2015). Evaluating the self-expressed unmet needs of emancipated foster youth over time. Children and Youth Services Review, 57, 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.07.016.

McMillen, C., Auslander, W., Elze, D., White, T., & Thompson, R. (2003). Educational experiences and aspirations of older youth in foster care.Child Welfare,475–495.

McMillen, J. C., Zima, B. T., Scott, L. D., Auslander, W. F., Munson, M. R., Ollie, M. T., & Spitznagel, E. L. (2005). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older youths in the foster care system. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 44(1), 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000145806.24274.d2.

Miller, R., Blakeslee, J., & Ison, C. (2020). Exploring college student identity among young people with foster care histories and mental health challenges. Children and Youth Services Review, 114, 104992.

Morton, B. M. (2018). The grip of trauma: How trauma disrupts the academic aspirations of foster youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 75, 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.04.021.

Morton, M. H., Dworsky, A., Matjasko, J. L., Curry, S. R., Schlueter, D., Chávez, R., & Farrell, A. F. (2018). Prevalence and correlates of youth homelessness in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(1), 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.10.006.

Mullen, A. L., Goyette, K. A., & Soares, J. A. (2003). Who goes to graduate school? Social and academic correlates of educational continuation after college. Sociology of Education, 143–169. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090274.

Naccarato, T., Brophy, M., & Courtney, M. E. (2010). Employment outcomes of foster youth: The results from the Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of Foster Youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(4), 551–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.11.009.

Posselt, J. R., & Grodsky, E. (2017). Graduate education and social stratification. Annual Review of\ Sociology, 43, 353. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-081715-074324.

Okpych, N. J., & Courtney, M. E. (2014). Does education pay for youth formerly in foster care? Comparison of employment outcomes with a national sample. Children and Youth Services Review, 43, 18–28.

Okpych, N. J., & Courtney, M. E. (2020). The relationship between extended foster care and college outcomes for foster care alumni. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 14(2), 254–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2019.1608888.

Okpych, N. J., & Gray, L. A. (2021). Ties that bond and bridge: Exploring social capital among college students with foster care histories using a novel social network instrument (FC-Connects). Innovative Higher Education, 46(6), 683–705.

Ostrove, J. M., Stewart, A. J., & Curtin, N. L. (2011). Social class and belonging: Implications for graduate students’ career aspirations. The Journal of Higher Education, 82(6), 748–774. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2011.11777226.

Katz, C. C., & Geiger, J. M. (2020). We need that person that doesn’t give up on us. Child Welfare, 97(6), 145–164.

Kearney, K. S., Naifeh, Z., Hammer, T., & Cain, A. (2019). Family” ties for foster alumni in college: An open systems consideration. The Review of Higher Education, 42(2), 793–824.

Randolph, K. A., & Thompson, H. (2017). A systematic review of interventions to improve post-secondary educational outcomes among foster care alumni. Children and Youth Services Review, 79, 602–611.

Roksa, J., & Kinsley, P. (2018). The role of family support in facilitating academic success of low-income students. Research in Higher Education, 60(4), 415–436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-018-9517-z.

Rosenberg, R., & Kim, Y. (2018). Aging out of foster care: Homelessness, post-secondary education, and employment. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 12(1), 99–115.

Salazar, A. M. (2013). The value of a college degree for foster care alumni: Comparisons with general population samples. Social Work, 58(2), 139–150.

Salazar, A. M., & Schelbe, L. (2021). Factors associated with post-college success for foster care alumni college graduates. Children and Youth Services Review, 126, 106031.

Salazar, A. M., Jones, K. R., Emerson, J. C., & Mucha, L. (2016). Postsecondary strengths, challenges, and supports experienced by foster care alumni college graduates. Journal of College Student Development, 57(3), 263–279. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2016.0029.

Samuels, G. M., & Pryce, J. M. (2008). What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger”: Survivalist self-reliance as resilience and risk among young adults aging out of foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 30(10), 1198–1210.

Sandelowski, M. (2001). Real qualitative researchers do not count: The use of numbers in qualitative research. Research in nursing & health, 24(3), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.1025.

Schelbe, L., Day, A., Geiger, J. M., & Piel, M. H. (2019). The state of evaluations of campus-based support programs serving foster care alumni in higher education. Child Welfare, 97(2), 23–40.

Sensiper, S., & Barragán, C. A. (2017). The Guardian Professions Program: Developing an advanced degree mentoring program for California’s foster care alumni. Children and Youth Services Review, 82, 329–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.09.032.

Skobba, K., Moorman, D., & Meyers, D. (2022). The cost of early independence: Unmet Material needs among College Students with Homelessness or Foster Care Histories. Journal of Adolescent Research, 37(5), 691–713.

Skobba, K., Meyers, D., & Tiller, L. (2018). Getting by and getting ahead: Social capital and transition to college among homeless and foster youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 94, 198–206.

Smith, J. M. (2017). I’m not gonna be another statistic”: The imagined futures of former foster youth. American Journal of Cultural Sociology, 5(1), 154–180. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41290-016-0018-2.

Thompson, H. M., Wojciak, A. S., & Cooley, M. E. (2018). The experience with independent living services for youth in care and those formerly in care. Children and Youth Services Review, 84, 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.11.012.

Tierney, W. G., Gupton, J. T., & Hallett, R. E. (2008). Transitions to adulthood for homeless adolescents: Education and public policy. Center for Higher Education Policy Analysis, University of Southern California. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED503645.pdf

Twale, D. J., Weidman, J. C., & Bethea, K. (2016). Conceptualizing socialization of graduate students of color: Revisiting the Weidman-Twale-Stein framework. Western Journal of Black Studies, 40(2), 80–94.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau (2021). The AFCARS report. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cb/afcarsreport28.pdf

U.S. Government Accountability Office (2016). Higher education: Actions needed to improve access to federal financial assistance for homeless and foster youth. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-16-343

Unrau, Y. A., Dawson, A., Hamilton, R. D., & Bennett, J. L. (2017). Perceived value of a campus-based college support program by students who aged out of foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 78, 64–73.