Abstract

Background

Children with Special Education Needs and Learning Difficulties are at risk of being excluded, or bullied because of their impairments. Within the bullying literature, two variables have been shown to be key in terms of its predictions: student–teacher relationship and students’ social status among peers.

Objective

The aim of this research was to assess the association between the student–teacher relationship and students’ social status in the peer group and bullying dimensions in children with SEN, LD, and typical development.

Method

A total of 320 children—55 with LD, 46 with SEN, and 219 in the control group – participated in the study, with a mean age of 11.04 (SD = 1.42), and 59.7% of whom were male. The model tested showed a good fit: χ2 (40) = 102.395, p < .001, CFI = .940, RMSEA = .070 [90% CI = .054, .088].

Results

Main findings show that children with SEN and LD had more difficulties in social participation and might be at higher risk of being bullied, compared with their classmates.

Conclusions

This study offers evidence on bullying in children with SEN and LD and its association with both relationship with teacher and students’ social status. For teachers, results highlight peculiarities and possible problems of school inclusion of children with SEN and LD. For educational researchers, findings add knowledge on literature focused on bullying in children with difficulties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since the 1970s, school inclusion of children with disabilities has received increased interest, both from educational professionals and researchers (for a review, see Guralnick, 2010). Models for inclusive contexts have been developed in many countries, the benefits of which have largely been demonstrated, both for children with disabilities and those without (Odom et al., 2011). Italy was the first country in the world to abolish special schools for children with disabilities and to include them in mainstream education contexts (Cornoldi et al., 1998). Despite the great efforts for inclusion made by education systems in many countries (Odom & Diamond, 1998), children with developmental delays may show vulnerability in terms of difficulties with social competence (Guralnick, 2010) and are at risk of social exclusion (Rose et al., 2011). Moreover, children with disabilities in inclusive educational contexts may be involved in bullying episodes, experiencing significantly higher rates of victimization than their peers without disabilities (Rose & Gage, 2017; Rose et al., 2011) because they have less social power (Malecki et al., 2020) and fewer social and communication skills necessary to avoid victimization (Guralnick, 2010; Rose & Gage, 2017), and because they are perceived as deviant from the norm group (Rose & Gage, 2017). Research has explored the elevated risk of bullying victimization in children with autism (Jackson et al., 2019), attention deficit disorder, and/or hyperactivity disorder (Fite et al., 2014; Prino et al., 2016), as well as in those affected by intellectual disabilities (Lorger et al., 2015). However, research on bullying among children with Special Education Needs (SENs) and Learning Difficulties (LDs) appears to be scarce at the present time.

Definitions of SENs and LDs

The definition of children with SENs varies widely between countries, as do the policies for their assessment (Barow & Östlund, 2020). In the Italian school system, “students with SENs” are defined as those who, temporarily or permanently, have some difficulties because of socio-economic, linguistic, or cultural reasons, or because of specific developmental disorders; the term represents a wide classification, including children with behavioral and emotional difficulties, such as Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (cf. Ministero dell’Istruzione dell’Università e della Ricerca [MIUR]). Of SENs, LDs, that is, reading, writing, and math deficits, are among the most frequently diagnosed specific developmental disorders (Cainelli & Bisiacchi, 2019; MIUR). All students with SENs and LDs are included in the mainstream Italian school system, in which curricular teachers provide them with pedagogical support in order to improve both their behavioral and academic performance.

School Adjustment in Children with SEN and LD

Research has shown that children with SEN and LD have difficulties in social skills (Freire et al., 2019; Wiener & Schneider, 2002). Compared to their classmates, children with SEN tend to have lower levels of prosocial behaviors (Dasioti & Kolaitis, 2018), are less accepted (Broomhead, 2019) and have fewer or no friends (Banks et al., 2018; Pinto et al., 2019). Also, students with LD present lower friendship quality, higher levels of conflict, more problems with relationship repair, and less stable relationships than their peers (Wiener & Schneider, 2002).

In addition, children with SEN present problems in terms of closeness and conflict with teachers (Freire et al., 2019) and children with LD have higher levels of dependency (Pasta et al., 2013) and greater dissatisfaction in their relationships with teachers (Murray & Greenberg, 2001) than their classmates. Children with LD tend to perceive significantly high levels of school danger (Murray & Greenberg, 2001) and in both in children with SEN and LD, the presence of internalizing and externalizing problems, such as emotional symptoms and hyperactivity, seems to be correlated with bullying victimization (Boyes et al., 2020; Dasioti & Kolaitis, 2018).

Bullying

Empirical research on bullying is relatively recent: the earliest studies on this topic emerged in the late 1970s in Scandinavia, with the pioneering work of Olweus (1978). Since then, bullying has received attention both from the media and academia (for a review, see Hymel & Swearer, 2015). Bullying is defined as an interpersonal aggressive behavior characterized by intentionality, repetition, and an imbalance of power between subjects; the literature distinguishes between direct bullying, with open attacks carried out by physical contact or by words, and indirect bullying, which is less visible and includes social isolation and exclusion (Olweus, 1991).

The prevalence of bullying varies greatly across studies, with 10% to 33% of students reporting victimization by peers and 5% to 13% admitting to bullying others (Hymel & Swearer, 2015). School bullying episodes affect both mental health and academic outcomes, since severe victims of school bullying show higher levels of depression, emotional symptoms, and hyperactivity/inattention (Marengo et al., 2018); lower levels of school liking (Stefanek et al., 2017); and lower achievement scores (Konishi et al., 2010) than their not-involved classmates. As research into bullying highlights the interaction of individual vulnerabilities, context effects, and experiences, a social-ecological model can be useful for understanding this phenomenon as a systemic problem, impacting the contexts in which such behaviors occur (Hymel & Swearer, 2015).

Protective Factors Against Bullying: The Role of Peers and Teachers

Relationships with peers and teachers are widely recognized as protective factors against bullying (e.g., Iotti et al., 2020; Longobardi et al., 2019a, 2019b; Marengo et al., 2018; Saracho & Spodek, 2007). Building relationships with peers is at the core of children’s development, providing them with social competences required to master social challenges (Guralnick, 2010).

Bullying can be considered a group process that involves not only a bully and a victim but also the entire group of peers (Salmivalli et al., 1996). This group of peers has a fundamental role in promoting or hindering bullying episodes in childhood (Saracho & Spodek, 2007) and social status among peers is a protective factor against school bullying (Iotti et al., 2020; Longobardi et al., 2019a, b). There is also a large body of literature indicating an association between relationships with teachers and behavioral outcomes in students (e.g., Sointu et al., 2017). A conflictual student–teacher relationship represents a risk factor for active bullying behaviors (Longobardi et al., 2018) or victimization (Marengo et al., 2018) and could lead to disruption and coercion escalations in students (Jalón Díaz-Aguado & Arias, 2013). By contrast, a warm and close student–teacher relationship is a protective factor against bullying (Iotti et al., 2020). This relationship, especially in the first years of school, has been pointed to as key to the future adaptation and development of students (Pianta et al., 1995; Wanders et al., 2020). However, because of their impairment, students with SEN and LD may have difficulties with social participation (Banks et al., 2018; Freire et al., 2019; Wiener & Schneider, 2002) and their relationships with teachers (Freire et al., 2019; Murray & Greenberg, 2001), being at higher risk of victimization and exclusion (Boyes et al., 2020; Dasioti & Kolaitis, 2018).

Purpose of this Study

Challenging aspects of school participation and inclusion of children with SEN and LD (Broomhead, 2019; Freire et al., 2019; Pinto et al., 2019) might expose these students as at risk of bullying. To the best of our knowledge, research on bullying in children with SEN and LD and its association with both the relationship with the teacher and students’ social status in the peer group are scarce. Studies on school inclusion of students with SEN and LD are mainly focused on single variables, such as their relationships with teachers (Freire et al., 2019; Pasta et al., 2013) or peers (Boyes et al., 2020; Pinto et al., 2019).

Therefore, the aim of the current research is to assess the relationship between these two variables (i.e., the student–teacher relationship and peer status) and bullying, testing the following:

-

– if there is a direct relationship between bullying dimensions (i.e., victimization and perpetration) and the quality of the relationship between students and teachers (closeness, conflict, and negative expectations) and students’ social status in the peer group (social preference and social impact);

-

– if there is a direct relationship between bullying dimensions and the presence of SEN and LD in the students, mediated by the quality of the relationship between students and teachers and students’ social status in the peer group, as shown in Fig. 1.

Method

Participants

The sample was composed of 320 students (59.7% males) recruited from seven primary and secondary schools in Northwest Italy. The schools were selected through convenience sampling, with the school directors, teachers, families and children being asked about their availability to participate in the research before the data collection.

The average age of the students was 11.04 (SD = 1.42, Min. = 8, Max. = 14). Of them, 68.4% were students with typical development (n = 219), 17.2% were students with LD (n = 55), and 14.4% were students with SEN (n = 46). The average age of the students with typical development was 10.75 (SD = 1.40, Min. = 8, Max. = 14), and it was 11.68 (SD = 1.25, Min. = 9, Max. = 14) for students with LD and 11.66 (SD = 1.28, Min. = 10, Max. = 14) for students with SEN. There were statistically significance differences in the mean ages of students (F (2, 311) = 15.34, p < 0.001; ƞ2 = 0.08). Specifically, the mean ages of students with SEN and students with LD were higher than the mean age of students with typical development (p < 0.001, in both cases). There was no statistically significance difference between the mean ages of students with LD and students with SEN. The percentage of males for the students with typical development was 58.5%, and it was 56.4% for students with LD and 69.6% for students with SEN. There were no statistically significance differences in gender distribution (χ (2) = 2.26, Cramer’s V = 0.08; p = 0.323) among the three groups of students.

In addition, the data of 40 teachers with a mean age of 46.06 (SD = 7.59, Min. = 30, Max. = 65) and 95.9% of whom were females were analyzed. The average of the years of teaching experience was 19.78 (SD = 9.57, Min. = 2, Max. = 42), and the average of the hours spent teaching the class per week was 10.55 (SD = 5.31, Min. = 2, Max. = 22).

Measures

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

Participants (teachers and students) were asked to report on their socio-demographic information: current age, gender, and school grade. Also, the teachers were asked to report their years of teaching experience and hours spent teaching the class per week.

Presence of SEN and LD in Students

In the Italian school context, “students with SEN” are defined as those who, temporary or permanently, have some difficulties because of socio-economic, linguistic, or cultural reasons, or because of specific developmental disorders. SEN represents a large classification that includes also children with behavioral and emotional difficulties (e.g., ADHD; and specific developmental disorders (cf. MIUR [Ministero dell’Istruzione dell’Università e della Ricerca]). Within the group of students with specific developmental disorders, the sub-category of students with LD exists (cf. MIUR [Ministero dell’Istruzione dell’Università e della Ricerca]). All students with SEN are included in mainstream schools. Neither of the groups of students with SEN and LD present cognitive impairment that affects general intelligence; for this reason, they are not considered to need a special education teacher. For students with SEN and LD, curricular teachers provide pedagogical help in order to close the gap between their and the other students’ behavioral and academic performance. While, in general, students with SEN do not have a medical diagnosis, students with LD need an official label by the local sanitary authority in order to be eligible for additional educational resources at school.

Please note that formal diagnoses of LD take place outside of the school curriculum and are based on national guidelines and protocols. The diagnoses are made by certified psychologists and psychiatrists, not by school teachers themselves. However, teachers usually work closely together with internal supervisors and school psychologists, who inform them about students’ diagnosed disabilities. In most cases, these diagnostic labels are registered in the school’s administration system and form the basis of Individual Education Plans. Hence, even though teachers obviously do not diagnose the children themselves, they are well informed about these diagnoses and, as such, can relatively reliably report on the prevalence of LD and SEN in their classes.

Thus, for our study, class teachers were asked to list all children in their classes who had SEN and who were officially labeled by the local sanitary authority as having LD. Teachers were asked to report on the presence of SEN and LD in each student. Three items were used: (1) “Does the student have special education needs?” (yes or no), (2) “If yes, which type of SEN (SEN, LD, etc.)?” and (3) “Does the student have a medical diagnosis?”.

Student Perception of Affective Relationship with Teacher Scale (SPARTS; Koomen & Jellesma, 2015).

The SPARTS consists of 25 items with a Likert-type response scale (1 = no, that is not true to 5 = yes, that is true). It measures the perception of conflict, closeness, and negative expectations with regard to a specific teacher in children aged 9 to 14 years old. The closeness subscale (8 items) reflects the degree of openness, warmth, and security that the students perceive in the relationship; the conflict subscale (10 items) refers to the degree to which a student perceives teacher-student interactions as negative, discordant, and unpredictable; and the negative expectations subscale (7 items) reflects a lack of confidence experienced by students in relationships with their teachers. When compiling the SPARTS in our study, the students were asked to refer to their “prevalent teacher” (i.e., the teacher with whom they spent the most hours per week, which, in the Italian education system, is the Italian language or science teacher). Prior investigators have provided evidence for the reliability and construct validity of the SPARTS dimensions (Jellesma et al., 2015; Longobardi et al., 2019a, b). The score for each subscale was generated by summing the scores for the items that made up that scale. For this study, the reliabilities (McDonald’s ω) for these subscales were adequate: 0.86 for closeness, 0.77 for conflict, and 0.58 for negative expectations.

Adolescent Peer Relations Instrument (APRI; Parada, 2000).

The APRI consists of 36 items with a Likert-type response scale (1 = never to 6 = every day). It measures three types of behaviors used to bully others (physical, verbal, and social) and three ways of being targeted (physical, verbal, and social). The higher the score, the greater the frequency of bullying or of being bullied. Prior investigators have demonstrated that the APRI is an instrument with solid psychometric proprieties (reliability and validity) for measuring bullying and victimization among preadolescents and adolescents (e.g., Balan et al., 2020). The score for each subscale was generated by summing the scores for the items that made up that scale. For this study, the reliabilities (McDonald’s ω) of each of the three ways of being targeted were adequate: 0.85 for verbal victimization, 0.85 for physical victimization, and 0.81 for social victimization. And, the reliabilities (McDonald’s ω) of each of the three types of behaviors used to bully others were adequate: 0.84 for verbal perpetration, 0.75 for physical perpetration, and 0.71 for social perpetration.

Peer Nomination Technique (Italian Version)

This is a peer nomination questionnaire inspired by Moreno’s sociogram techniques (1934) and Coie et al. (1982) sociometric strategy for assessing peer statuses in the classroom. It consists of six questions in which children have to nominate three of their peers. The questions are the following: (i) “Who would you want as a table partner?” (ii) “Who would you want as a schoolwork partner?” (iii) “Who would you want as a field trip buddy?” (iv) “Who would you NOT want as a table partner?” (v) “Who would you NOT want as a schoolwork partner?” and (vi) “Who would you NOT want as a field trip buddy?” For each child, the sum of the positive nominations received from all peers represented their liking (L) score, and the sum of the negative nominations received represented their disliking (D) score. The L and D scores were standardized within each class (Lz and Dz) and used to compute a social preference (SP) score (Lz − Dz) and a social impact (SI) score (Lz + Dz) for each child.

Procedures

The school principals gave permission for their teachers to participate in the study, and consent was obtained from each teacher who participated. Prior to data collection, phase 1 included obtaining parental consent to participate and describing the nature and objective of the study in compliance with the ethical code of the Italian Association for Psychology (AIP), which was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Turin (Italy). The forms stated that data confidentiality would be assured and that participation in the study was voluntary. Adherence to the legal requirements of the study country was followed and 'informed consent' has been appropriately obtained. No potential conflict of interest existed for either author in the form of grants, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in, or any close relationship with, an organization whose interests, financial or otherwise, may be affected by the publication of the paper.

Data Analysis

First, descriptive statistics were calculated for the participants’ characteristics (means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables). Then, to examine whether there were significant differences in sociodemographic characteristics between three children’s groups (SEN, LD, and typical development), a Chi-squared test was performed on the gender distribution, while a one-way ANOVA test was used for the children’s age. When the one-away ANOVA test was used, the equality of variance was checked by Levene’s test. As the three groups analyzed had equal variance, no corrections to the one-way ANOVA test were required.

Second, descriptive statistics (means, deviation standard, and range) were computed on the main study variables (SPARTS, APRI, and students’ social status). The calculation of skewness and kurtosis values was carried out to check the normality of the data. As Table 1 shows, all the values for univariate skewness and kurtosis for all the variables analyzed in the groups of children with SENs and LDs fell within the conventional criteria for normality (−3 to 3 for skewness and −10 to 10 for kurtosis; Kline, 2015); they were thus considered to have a normal distribution and therefore no data transformation was performed. However, in children with typical development and for the whole sample, the values for univariate skewness and kurtosis for physical and social victimization and verbal and physical perpetration did not meet these conventional criteria for normality. Consequently, these variables were transformed using the square root transformation, since this is one of the best transformations for dealing with asymmetric distributions (Rodríguez-Ayán & Ruiz, 2008).

Third, separate multivariate analyses of covariance (MANCOVA) on dimensions of SPARTS, APRI and students’ socials status were performed in order to examine the effect of the presence of SEN, LD, and typical development in students. In these multivariate analyses, the student’s age was added as a covariate to control the influence that this variable may have on the analyzed variables, since the one-way ANOVA showed statistically significant differences between students with SEN and LD and students with typical development in terms of age. The Pillai’s trace criterion (the most robust criterion) was used (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007) to examine significant difference in multivariate analysis and an effect size was estimated using partial eta squared (η2). Subsequently, if the overall F test showed mean differences among children’s groups, a post hoc univariate ANCOVA test was used to determine which means were statistically different from others.

Fourth, Pearson correlation coefficient test were carried out to examine the relationships between the research variables. All these analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0 for windows.

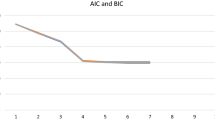

Lastly, a structural equation model was hypothesized, tested, and evaluated using Mplus 7.4. The model included a sequence in which the presence of SEN/LD in the children affected students’ relations with teachers and students’ statuses and bullying victimization and perpetration, and also included the effect of students’ relationships with teachers and students’ statuses in terms of bullying. In order to include the three groups in the model (SEN, LD, and typical development), two dummy variables were created: SEN, where students with special education needs = 1 and the rest of the participants = 0; and TD, where students with typical development = 1 and the rest of the participants = 0. Therefore, students with LD were used as the reference group. Also, it included the students’ ages as a covariate to control the influence that this variable may have on the analyzed variables (see Fig. 1). The estimation method was maximum likelihood with robust corrections (MLR) for the estimates to accommodate the nonnormality nature of the data (e.g., Finney & DiStefano, 2013; Satorra & Bentler, 1994). Full information maximum likelihood was used to deal with missing data, a procedure adequate for data missing completely at random and missing at random; this is the most recommended method for structural models (Finney & Di Stefano, 2013).

The goodness of fit for each model was assessed with several fit indexes (Kline, 2015; Tanaka, 1993): (1) The χ2 statistic, which is a test of the difference between the observed covariance matrix and the one predicted by the specified model; (2) the comparative fit index (CFI), which assumes a non-central chi-square distribution with cut-off criteria of 0.90 or more (ideally over 0.95; Hu & Bentler, 1999) indicating adequate fit; and (3) the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and its 90% confidence interval. Values higher than 0.90 for the CFI or lower than 0.08 in the RMSEA are considered a reasonable fit (Kline, 2015), and values of 0.95 for the CFI and of 0.06 for the RMSEA are considered excellent (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Results

The descriptive statistics for the variables studied are presented in Table 1.

Differences Between the Groups of Children Regarding the Analyzed Variables

Separated MANCOVA tests were performed to determine if, controlling for the ages of the students, the presence of SEN, LD, or typical development in students affects the main study variables. Previous to running the MANCOVA tests, the assumption of homogeneity of covariance was examined using Box’s M test (SPARTS 32.87, F = 2.67, p = 0.001; APRI 211.18, F = 4.79, p < 0.001; Student’s social status 21.31, F = 3.49, p = 0.002), and, consequently, Pillai’s trace was used instead of Wilk’s lambda to evaluate the multivariate statistical significance of the main effects in each case.

Regarding the student–teacher relationship, measured in terms of the conflict, closeness, and negative expectations dimensions (SPARTS), the multivariate results showed that age was statistically significant as a covariate [Pillai’s trace = 0.04, F(3, 308) = 4.00, p = 0.008, η2 = 0.04], but not effect was found for the presence of SEN in students [Pillai’s trace = 0.01, F(6, 618) = 0.26, p = 0.956, η2 = 0.002]. Table 2 presents the results of the univariate ANCOVAs of the main effects in terms of the scores for the different dependent variables in the groups of children.

Concerning the violence victimization and perpetration dimensions (APRI), the multivariate results showed that age was statistically significant as a covariate: Pillai’s trace = 0.06, F(6, 304) = 3.04, p = 0.007, η2 = 0.06. A main effect was found for the presence of SEN in students: Pillai’s trace = 0.08, F(12, 610) = 2.22, p = 0.010, η2 = 0.04. Subsequent univariate ANCOVAs revealed statistically significant differences for the presence of SEN in the students related to the following: verbal violence victimization [F(2, 309) = 5.38, p = 0.005, η2 = 0.03], physical violence victimization [F(2, 309) = 5.85, p = 0.003, η2 = 0.04], social violence victimization [F(2, 309) = 7.29, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.05], and physical violence perpetration [F(2, 309) = 5.49, p = 0.005, η2 = 0.03] (see Table 2). Post hoc comparisons revealed that students with SEN showed statistically significantly higher values in terms of all types of violence victimization than students with typical development (Verbal: p = 0.008, Physical: p = 0.007, and Social: p = 0.001) and students with LD (Verbal: p = 0.010, Physical: p = 0.005, and Social: p = 0.002). There was no statistically significant difference between students with LD and those with typical development regarding these variables. In addition, post hoc comparisons revealed that students with SEN showed statistically significantly higher values in terms of physical violence perpetration than students with typical development (p = 0.008) and students with LD (p = 0.009). Again, there was no statistically significant difference between students with LD and those with typical development concerning this variable.

With regard to students’ social status measured as the effect of social preference and social impact, the multivariate results also showed that age was marginally statistically significant as a covariate [Pillai’s trace = 0.02, F(2, 309) = 2.80, p = 0.062, η2 = 0.02]. Moreover, a main effect was found for the presence of SEN in students [Pillai’s trace = 0.12, F(4, 620)] = 10.13, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.06]. Subsequent univariate ANCOVAs revealed statistically significant differences for the presence of SEN in the students related to social preference [F(2, 310) = 20.02, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.11], but not for social impact [F(2, 310) = 1.23, p = 0.295, η2 = 0.01] (see Table 2). Post hoc comparisons revealed that students with typical development showed statistically significantly higher values in terms of social preference than students with SEN (p < 0.001) and students with LD (p = 0.015). In addition, students with LD showed statistically significantly higher values regarding social preference than students with SEN (p = 0.011).

Intercorrelations Between the Variables Under Study

Table 2 shows the correlations between all the variables. As can be seen from Table 2, most of the variables showed statistically significant relationships among them. The conflict and negative expectations dimensions of SPARTS showed positive relationships with all types of violence (victimization and perpetration) and the student’s age, indicating that a higher level in terms of the student’s perception of his/her relationship with the teacher as conflictive and the student’s negative expectations regarding his/her relationship with the teacher were associated with higher levels of all types of violence (victimization and perpetration) and with being older. However, the closeness dimension showed a negative and statistically significant association with the perpetration of types of violence and with the student’s age, indicating that a higher level of the student’s perception of his/her relationship with the teacher in terms of closeness was related to lower levels of all types of violence perpetration and with being younger. Also, the closeness dimension showed a positive relationship with social preference, indicating that a higher level of the student’s perception of his/her relationship with the teacher in terms of closeness was related to higher levels of social preference. In addition, all types of violence (victimization and perpetration) were negatively related to social preference, indicating that higher levels of violence were associated with lower levels of social preference, except regarding social perpetration. In addition, only verbal and physical violence perpetration showed a positive association with social impact and the student’s age, indicating that higher levels of verbal and physical violence perpetration were linked to social impact and to being older. (Table 3)

Predicting Bullying: A Structural Equation Model

The model showed a good fit: χ2 (40) = 102.398, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.940, RMSEA = 0.070 [90% CI = 0.054, 0.088]. In addition, the explained variance of victimization in this model was 31.1%, while for perpetration it was 27.5%. Figure 2 shows the structural model parameters’ standardized estimations.

As can be seen in Fig. 2, the presence of SENs in students had a positive direct effect on bullying victimization, whereas typical development had a negative one. As the reference group was LD students, these relationships mean that levels of bullying victimization were higher for LD students when compared to typical development students, while SEN students showed higher levels of bullying victimization when compared to LD students. In addition, a positive direct effect of typical development in students was found on social preference compared to students with LDs, and a negative effect for SEN students. That is, students with LDs showed lower levels of social preference when compared to typical development students but higher social preference when compared to SEN students. In turn, social preference had a positive direct effect on bullying victimization.

The student’s age had a positive direct effect on bullying perpetration, social preference, and the conflictive and negative expectations dimensions of the student’s perception of his/her relationship with the teacher, and it had a negative direct effect on the closeness dimension. In turn, social preference and the dimensions of the student’s perception of his/her relationship with the teacher (conflict, closeness, and negative expectations) had a positive effect on bullying victimization. Finally, there was a positive and direct effect of social impact and the student’s perception of his/her relationship with the teacher with reference to the conflict dimension on bullying perpetration.

Discussion

The purpose of the study was to assess the quality of the relationships with teachers from students’ viewpoints and their social status in the peer group in relation with bullying dimensions (victimization and perpetration). First, we explored the role of student–teacher relationship in the whole group class (i.e. in students with typical development, SEN and LD); second, we analyzed the association between peer status and bullying in the whole group class; finally, we compared the association of these variables in three groups of students: children with typical development, SEN and LD.

Student–Teacher Relationship

The findings from the bivariate correlations found relationships among most of the analyzed variables.

Conflict with Teacher, Negative Expectation and Bullying

In the whole group class, the student’s perception of the relationship with the teacher as conflictual, and negative expectations about this relationship, were positively related to all the ways of being targeted (verbal, physical, and social), the three types of behaviors used to bully others (physical, verbal, and social), and the student’s age. These findings might indicate that the student’s perception of a conflictual relationship with the teacher, and negative expectations in terms of this relationship, are associated with high levels of victimization and perpetration, and the student's age. That is, students with perceived conflictual and negative relationships with their teachers may also be those who tend to be more involved in bullying episodes. In addition, the possibility of taking part in bullying episodes, as a bully or victim, seems to be higher when students are older.

These findings confirm a large body of literature indicating the association between relationships with teachers and behavioral outcomes in students (e.g., Sointu et al., 2017). A conflictual student–teacher relationship represents a risk factor for active bullying behaviors (Longobardi et al., 2018) or victimization (Marengo et al., 2018) and could lead to disruption and coercion escalations in students (Jalón Díaz-Aguado & Arias, 2013). Moreover, taking into account age, the direction of the relationship between teacher acceptance and students’ perceptions of teacher support is age-specific (Košir & Tement, 2014): as they get older, students develop less positive relationships with teachers (McGrath & Van Bergen, 2015). Our results seem to confirm that early adolescence could represent a critical moment for students, especially for those at risk regarding social and emotional factors (McGrath & Van Bergen, 2015), taking also into account that older children experience a decline in physical victimization, and a shift toward verbal forms of victimization (Marengo et al., 2019), which is less visible for teachers.

Closeness with Teacher and Bullying

In the whole group class, the closeness dimension was negatively related to the three types of behavior used to bully others (physical, verbal, and social) and to the student’s age. These results indicate that a higher level of student perception of a close relationship with a teacher may be associated with lower levels of all types of violence perpetration, and with being younger. That is, students with perceived warm and close relationships with their teachers may also be those less likely to bully others. In addition, the possibility of taking part in bullying episodes as a bully seems to be lower when students are younger. Our results highlight the positive impact of the student–teacher relationship on children’s behavior (Espelage & Swearer, 2003) and the protective role of this relationship against bullying (Jungert et al., 2016). In addition, the results confirm the developmental trajectory of bullying behaviors, being less frequent in younger children and increasing with age (Cook et al., 2010; Ladd et al., 2017).

Closeness with Teacher and Social Preference Among Peers

Also, in the whole group class the closeness dimension was positively linked to social preference, indicating that a higher level of student’s perception of a close relationship with teacher was associated with higher levels of social preference. That is, students sharing warm and positive relationships with teachers might be more accepted by their groups of peers. This result confirms the important role of a warm and close student–teacher relationship in the first years of school for students’ future adaptation and development (Pianta et al., 1995; Wanders et al., 2020).

Student’s Age, Relationship with Teacher and Bullying Behaviors

The student’s age was found to have a direct effect on the three dimensions of the student’s perception of the relationship with the teacher (i.e., conflict, closeness, and negative expectations) in the whole group class. Specifically, older students showed higher levels of conflict and negative expectations, and lower levels of closeness in their relationship with teachers. In turn, the three dimensions of the student–teacher relationship positively predicted bullying victimization, and the student’s perception of a conflictual relationship with the teacher and the student’s social impact within the peer group predicted bullying perpetration. That is, a positive relationship with teachers is protective against bullying victimization, consistent with previous literature (Iotti et al., 2020). In turn, difficulties in the relationships with teachers and peers might expose students to higher risk of exibit bullying behaviors (Pianta et al., 1995; Wanders et al., 2020). Taking into account the age-specificity in the relationship between teachers’ support and students’ perceptions, that tend to decrease with age (Košir & Tement, 2014; McGrath & Van Bergen, 2015), these results confirm the influence of early positive relationships with teachers on the long-lasting school well-being of students (Pianta et al., 1995; Wanders et al., 2020).

Peer Status, Bullying and Age

Considering the whole group class, the results show that student age predicted peer status, with older students showing higher levels of social preference among peers. In addition, a link seems to exist between bullying victimization and perpetration and social status among peers. Specifically, we have found the following results.

The three pathways of being targeted (verbal, physical, and social) and the types of behaviors used to bully others (physical, verbal, and social) were negatively related to social preference, except in the case of social perpetration. This finding may indicate that higher levels of violence in students, both in victimization and perpetration, are associated with lower levels of social preference among peers. That is, students who suffer from or act out bullying are less preferred by their peers. Only verbal and physical violence perpetration showed a positive association with social impact and the student’s age. That is, older students who exhibit higher levels of verbal and physical violence perpetration might have a higher social status among peers. The student’s age had a positive direct effect on bullying perpetration. This finding seems to indicate that older students may exhibit higher levels of bullying behaviors.

Considering these results together, findings are in line with previous research, showing that in older students reported rates of bullying are higher, and bullying behaviors are related with an increase in social status (Van der Ploeg et al., 2020). In turn, younger students report higher rates of victimization (Scheithaue et al., 2006) and tend to sanction bullying behaviors with a decrease in peer status. Bullying behaviors are characterized by a developmental trajectory (Cook et al., 2010) and increase over the years from childhood, with a peak during early adolescence (Hymel & Swearer, 2015; Menesini & Salmivali, 2017). In addition, research has shown that, starting from middle childhood, bullying and victimization start to be group processes (Monks et al., 2021) and are driven by status goals (Salmivalli, 2010). Older students might turn to bullying more than younger students because this could lead to an improvement in their social status.

Children with SEN, LD, and Typical Development

Finally, we compared the results of the associations between bullying variables, student–teacher relationship, peer status, and the presence of SEN, LD, or typical development in children.

Bullying in Children with SEN, LD and Typical Development

The results showed significant differences between students with SEN, LD, and typical development in terms of the three types of behaviors used to bully others (physical, verbal, and social) and physical violence perpetration. Specifically, students with SEN showed higher values for all types of violence victimization, and in the perpetration of physical violence, than students with typical development and students with LD. It is interesting to note that no difference was found between students who have LD and those with typical development regarding these variables when studied in the analysis of variance context. When modeled using the structural equation model, the presence of LDs in students had a direct effect on bullying victimization, indicating that students who had LDs were bullied more than students with typical development but less than SEN students.

These findings are in line with previous research, showing that children with SEN tend to report more bullying victimization and perpetration than their peers (Dasioti & Kolaitis, 2018; Rose & Gage, 2017; Rose et al., 2011). As suggested by other reseach (Fink et al., 2015), we could hypothesize that probably the presence of behavioral and emotional problems might predicts bullying behaviors in children with SEN. Literature has shown that children with SEN tend to report high levels of behavioral problems (Dasioti & Kolaitis, 2018), and this could make their impairments more visible than the difficulties of children with LD. Moreover, in the Italian school context, SEN is a large classification that also includes children with behavioral and emotional difficulties (e.g., ADHD; cf. MIUR [Ministero dell’Istruzione dell’Università e della Ricerca]). Thus, the different results in terms of bullying variables (victimization and perpetration) registered in children with SEN and LD, and in children with typical development, could be explained by the presence of behavioral and emotional problems in the children with SEN in our sample. As confirmed by previous studies, bullying seems to be part of a continuum of interpersonal relationships that exist within the peer group, and there could be an association between social skills problems and bullying (Maunder & Crafter, 2018).

Social Preference in Children with SEN, LD and Typical Development

Results showed significant differences between students with SEN, students with LD, and those with typical development in terms of social preference scores. Specifically, students with typical development showed higher values regarding social preference than students with LD, and this finding was supported also by the results of the structural equation mode. Also, students with LD showed higher social preference than students with SEN. This result confirms the large body of literature showing that children with disabilities or difficulties at school score lower in terms of levels of popularity and are at risk of social exclusion (Rose et al., 2011). In particular, Pinto et al. (2019) found that children with SEN have more problems in peer relationships, score lower in terms of peer acceptance, have fewer reciprocated friendships, and experience less integration into peer groups.

When comparing social preference with regard to SENs and LDs, students with LDs showed higher values in terms of social preference than did students with SENs. To the best of our knowledge, previous studies comparing the social status of students with SENs and LDs at school do not exist, and this finding adds to the previous literature focusing on school inclusion and the adjustment of children with disabilities. Research has documented the social skill difficulties in both children with SENs and with LDs and their consequent problems in peer relationships. When compared with their typical development classmates, children with SENs have lower levels of peer acceptance and are generally less integrated into peer groups (Pinto et al., 2019), scoring lower in social participation. In particular, students with SENs showing emotional and behavioral difficulties are more likely to have fewer friends and to experience negative peer relationships (Banks et al., 2018). In sum, our results may be explained by SEN students’ problems with peer acceptance and integration into peer groups, which may lead to lower social preference when compared to children with LDs.

Student–Teacher Relationship and Bullying in Children with Sen, Ld and Typical Development

Finally, no differences among student groups (SEN, LD and typical development) were found concerning the three dimensions of relationships with teachers and two ways of being targeted (verbal, and social). This finding is encouraging and seems to indicate that the existing association between bullying victimization and the relationship with the teacher (Marengo et al., 2018), measured in terms of the conflict, closeness, and negative expectations dimensions, might be independent from the SEN or LD status. With regard to the structural equation model, neither there was an effect of belonging to the group of student with SEN, LD, or typical development concerning the three dimensions of the student’s perception of the relationship with the teacher (conflict, closeness, and negative expectations), probably because relationships between students and teachers is not influenced by the presence of SEN or LD in children.

Study Limitations

Some limitations of the present work should be discussed. The data were obtained through convenience sampling, and through students’ self-reports, which may incorporate the effect of social desirability, and there is also a risk of self-selection. Therefore, it is not possible to generalize the findings to people located in cities or from different cultural backgrounds. A more representative sample from different areas of Italy would have allowed for the better generalization of the results. Thus, the use of other samples in future research would be recommended. Thereby, it would test the generalizability of our findings in the future. In addition, the data are cross-sectional, and, therefore, it is not possible to draw inferences about cause-and-effect relationships. Moreover, several studies have pointed to some biases that can stem from the use of mediation within a cross-sectional framework (Cole & Maxwell, 2003; Maxwell et al., 2011). Thus, future researchers could use a longitudinal design to test the causal relationships among variables, which might help us understand how the connections between them unfold over time.

Another limitation of this study is related to the McDonald’s omega value of the negative expectations (ω = 0.58) dimension of the SPARTS. Consequently, the findings must be verified in other samples in which the quality of their measurement is improved. Finally, some variables that could also affect bully behaviors, such as children’s temperament, were not assessed, and therefore its influence could not be studied. Future research on this regard would also be welcomed.

Conclusion

This work represents the first study investigating the relationships between the presence of SEN and LD in students, the quality of the relationship with the teacher from the student’s viewpoint, the social status of the student, and bullying dimensions (victimization and perpetration). This study provides insight into the patterns of relationships among the study variables. This is the first time the interrelations of such a group of variables have been studied, and we have tried to do it in the simplest and most sophisticated way, always based on theory. Although bullying has received international attention, there is still a dearth of research on this topic for specific samples. We need to address violence across multiple perpetrators and multiple systems. Further research is needed to provide an in-depth understanding of the role of behavioral and emotional problems in the development of bullying behaviors of children with SEN and LD.

The findings of this study could be important for teachers and educational researchers in different ways. For teachers, the results could highlight peculiarities of children with SEN and LD and could represent an opportunity for them to meditate on, and eventually re-think, the pedagogical resources educators provide, in order to enhance these children’s social inclusion and prevent bullying episodes at school. Our results point to higher levels of bullying victimization for LD and SEN students, especially for the latter. As this victimization has been predicted both by teacher attitudes and group dynamics, specifically regarding social preference, teachers’ actions could reduce bullying victimization of LD and SEN students in two ways: through their own behavior toward students, by reducing conflict and negative expectations, and through the improvement of SEN and LD students’ social skills and peer relationships. For educational researchers, findings add knowledge on the association between bullying student–teacher relationship and peer status in children with SEN and LD. In light of the results that have emerged, it would be interesting to focus any future research on other trajectories of bullying in children with SEN and LD, in order to better understand the specificities of their adjustment in a mainstream education context.

Data Availability

Data will be available on request at University of Turin.

References

Balan, R., Dobrean, A., Balazsi, R., Parada, R. H., & Predescu, E. (2020). The Adolescent Peer Relations Instrument Bully/Target: Measurement Invariance Across Gender, Age, and Clinical Status. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Advance online publication. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520922350

Banks, J., McCoy, S., & Frawley, D. (2018). One of the gang? peer relations among students with special educational needs in irish mainstream primary schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 33(3), 396–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2017.1327397

Barow, T., & Östlund, D. (2020). Stuck in failure: Comparing special education needs assessment policies and practices in Sweden and Germany. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2020.1729521

Boyes, M. E., Leitão, S., Claessen, M., Badcock, N. A., & Nayton, M. (2020). Correlates of externalising and internalising problems in children with dyslexia: An analysis of data from clinical casefiles. Australian Psychologist, 55(1), 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12409

Broomhead, K. E. (2019). Acceptance or rejection? the social experiences of children with special educational needs and disabilities within a mainstream primary school. Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2018.1535610

Cainelli, E., & Bisiacchi, P. S. (2019). Diagnosis and treatment of developmental dyslexia and specific learning disabilities: Primum non nocere. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 40(7), 558–562. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000702

Carman, S. N., & Chapparo, C. J. (2012). Children who experience difficulties with learning: Mother and child perceptions of social competence. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 59(5), 339–346.

Coie, J. D., Dodge, K. A., & Coppotelli, H. A. (1982). Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18, 557–569. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.18.4.557

Cole, D. A., & Maxwell, S. E. (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(4), 558–577.

Cook, C. R., Williams, K. R., Guerra, N. G., Kim, T. E., & Sadek, S. (2010). Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic investigation. School Psychology Quarterly, 25(2), 65. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020149

Cornoldi, C., Terreni, A., Scruggs, T. E., & Mastropieri, M. A. (1998). Teacher attitudes in Italy after twenty years of inclusion. Remedial and Special Education, 19(6), 350–356.

Dasioti, Α, & Kolaitis, G. (2018). Βullying and the mental health of schoolchildren with special educational needs in primary education. Psychiatriki, 29(2), 149–159. https://doi.org/10.22365/jpsych.2018.292.149

Espelage, D. L., & Swearer, S. M. (2003). Research on school bullying and victimization: What have we learned and where do we go from here?. School Psychology Review, 32(3), 365–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2003.12086206

Fink, E., Deighton, J., Humphrey, N., & Wolpert, M. (2015). Assessing the bullying and victimisation experiences of children with special educational needs in mainstream schools: Development and validation of the Bullying Behaviour and Experience Scale. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 36, 611–619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2014.10.048

Finney, S. J., & Di Stefano, C. (2013). Non normal and categorical data in structural equation modelling. In G.R. Hancock & R.O. Mueller (Eds.). A second course in structural equation modelling (2nd ed., pp. 439–492). Charlotte, NC: Information Age

Fite, P. J., Evan, S. C., Cooley, J. L., & Rubens, S. L. (2014). Further evaluation of association between attention-deficit/hyperactivity and oppositional defiant disorder symptoms and bullying- victimization in adolescence. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 45(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-013-0376-8

Freire, S., Pipa, J., Aguiar, C., Vaz da Silva, F., & Moreira, S. (2019). Student–teacher closeness and conflict in students with and without special educational needs. British Educational Research Journal. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3588

Guralnick, M. J. (2010). Early intervention approaches to enhance the peer-related social competence of young children with developmental delays: A historical perspective. Infants and Young Children, 23(2), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/IYC.0b013e3181d22e14

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hymel, S., & Swearer, S. M. (2015). Four decades of research on school bullying: An introduction. American Psychologist, 70(4), 293. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038928

Iotti, N. O., Thornberg, R., Longobardi, C., & Jungert, T. (2020). Early adolescents’ emotional and behavioral difficulties, Student-Teacher relationships, and motivation to defend in bullying incidents. Child and Youth Care Forum, 49, 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-019-09519-3

Jackson, D. B., Vaughn, M. G., & Kremer, K. P. (2019). Bully victimization and child and adolescent health: New evidence from the 2016 NSCH. Annals of Epidemiology, 29, 60–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.09.004

Jalón Díaz-Aguado, M. J., & Arias, R. M. (2013). Peer bullying and disruption-coercion escalations in student-teacher relationship. Psicothema, 25(2), 206–213. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2012.312

Jellesma, F. C., Zee, M., & Koomen, H. M. (2015). Children’s perceptions of the relationship with the teacher: Associations with appraisals and internalizing problems in middle childhood. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 36, 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.09.002

Jungert, T., Piroddi, B., & Thornberg, R. (2016). Early adolescents’ motivations to defend victims in school bullying and their perceptions of student–teacher relationships: A self-determination theory approach. Journal of Adolescence, 53, 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.09.001

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practices of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press.

Konishi, C., Hymel, S., Zumbo, B. D., & Li, Z. (2010). Do school bullying and student-teacher relationships matter for academic achievement? A multilevel analysis. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 25(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573509357550

Koomen, H. M., & Jellesma, F. C. (2015). Can closeness, conflict, and dependency be used to characterize students’ perceptions of the affective relationship with their teacher? Testing a new child measure in middle childhood. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85, 479–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12094

Košir, K., & Tement, S. (2014). Teacher–student relationship and academic achievement: A cross-lagged longitudinal study on three different age groups. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 29(3), 409–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-013-0205-2

Kretschmer, T. (2016). What explains correlates of peer victimization? A systematic review of mediating factors. Adolescent Research Review, 1(4), 341–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-016-0035-y

Ladd, G. W., Ettekal, I., & Kochenderfer-Ladd, B. (2017). Peer victimization trajectories from kindergarten through high school: Differential pathways for children’s school engagement and achievement? Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(6), 826–841. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000177

Longobardi, C., Badenes-Ribera, L., Gastaldi, F. G. M., & Prino, L. E. (2019a). The student–teacher relationship quality in children with selective mutism. Psychology in the Schools, 56(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22175

Longobardi, C., Borello, L., Thornberg, R., & Settanni, M. (2020). Empathy and defending behaviours in school bullying: The mediating role of motivation to defend victims. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(2), 473–486. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12289

Longobardi, C., Iotti, N. O., Jungert, T., & Settanni, M. (2018). Student-teacher relationships and bullying: The role of student social status. Journal of Adolescence, 63, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.12.001

Longobardi, C., Settanni, M., Prino, L. E., Fabris, M. A., & Marengo, D. (2019b). Students’ psychological adjustment in normative school transitions from kindergarten to high school: Investigating the role of teacher-student relationship quality. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1238. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01238

Lorger, T., Schmidt, M., & Vukman, K. B. (2015). The social aacceptance of secondary school students with learning disabilities. CEPS Journal, 5(2), 177–194.

Malecki, C. K., Demaray, M. K., Smith, T. J., & Emmons, J. (2020). Disability, poverty, and other risk factors associated with involvement in bullying behaviors. Journal of School Psychology, 78, 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2020.01.002

Marengo, D., Jungert, T., Iotti, N. O., Settanni, M., Thornberg, R., & Longobardi, C. (2018). Conflictual student–teacher relationship, emotional and behavioral problems, prosocial behavior, and their associations with bullies, victims, and bullies/victims. Educational Psychology, 38(9), 1201–1217. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1481199

Marengo, D., Settanni, M., Prino, L. E., Parada, R. H., & Longobardi, C. (2019). Exploring the dimensional structure of bullying victimization among primary and lower-secondary school students: Is one factor enough, or do we need more? Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 770. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00770

Matthews, T., Danese, A., Wertz, J., Ambler, A., Kelly, M., Diver, A., & Arseneault, L. (2015). Social isolation and mental health at primary and secondary school entry: A longitudinal cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(3), 225–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.12.008

Maunder, R. E., & Crafter, S. (2018). School bullying from a sociocultural perspective. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 38, 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.10.010

Maxwell, S. E., Cole, D. A., & Mitchell, M. A. (2011). Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation: Partial and complete mediation under an autoregressive model. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 46(5), 816–841. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2011.606716

McGrath, K. F., & Van Bergen, P. (2015). Who, when, why and to what end? Students at risk of negative student–teacher relationships and their outcomes. Educational Research Review, 14, 1–17.

Menesini, E., & Salmivalli, C. (2017). Bullying in schools: The state of knowledge and effective interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 22(sup1), 240–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2017.1279740

MIUR: Direzione generale per lo studente, l'integrazione e la partecipazione. Strumenti d’intervento per alunni con bisogni educativi speciali e organizzazione territoriale per l’inclusione scolastica (2012). Available at: https://www.miur.gov.it/documents/20182/0/direttiva+ministeriale+27+dicembre+2012.pdf/e1ee3673-cf97-441c-b14d-7ae5f386c78c?version=1.1&t=1496144766837

Monks, C. P., Smith, P. K., & Kucaba, K. (2021). Peer victimisation in early childhood; observations of participant roles and sex differences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 415. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020415

Moreno, J. L. (1934). Who shall survive? Nervous and Mental Disease Publishing Company.

Murray, C., & Greenberg, M. T. (2001). Relationships with teachers and bonds with school: Social emotional adjustment correlates for children with and without disabilities. Psychology in the Schools, 38(1), 25–41.

MIUR: Ufficio Statistica e Studi. Gli alunni con Disturbi Specifici dell’Apprendimento (DSA) nell’a.s. 2016/2017. 2018. Available at: https://www.miur.gov.it/documents/20182/991467/FOCUS_alunni1con1DSA_a.s.12016_2017_def.pdf/9af5872b-4404-4d56- 8ac1–8ffdbee61ef4?version51.0

Odom, S. L., Buysse, V., & Soukakou, E. (2011). Inclusion for young children with disabilities: A quarter century of research perspectives. Journal of Early Intervention, 33(4), 344–356. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815111430094

Odom, S. L., & Diamond, K. E. (1998). Inclusion of young children with special needs in early childhood education: The research base. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 13(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-2006(99)80023-4

Olweus, D. (1978). Aggression in the schools: Bullies and whipping boys. Hemisphere.

Olweus, D. (1991). Victimization among school children. In Advances in psychology (Vol. 76, pp. 45–102). North-Holland.

Parada, R. (2000). Adolescent Peer Relations Instrument: A theoretical and empirical basis for the measurement of participant roles in bullying and victimisation of adolescence: An interim test manual and a research monograph: A test manual. Publication Unit, Self-concept Enhancement and Learning Facilitation (SELF) Research Centre, University of Western Sydney.

Pasta, T., Mendola, M., Longobardi, C., Prino, L. E., & Gastaldi, F. G. M. (2013). Attributional style of children with and without specific learning disability. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 11(3), 649–664. https://doi.org/10.14204/ejrep.31.13064

Pianta, R. C., Steinberg, M. S., & Rollins, K. B. (1995). The first two years of school: Teacher-child relationships and deflections in children’s classroom adjustment. Development and Psychopathology, 7(2), 295–312.

Pinto, C., Baines, E., & Bakopoulou, I. (2019). The peer relations of pupils with special educational needs in mainstream primary schools: The importance of meaningful contact and interaction with peers. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(4), 818–837. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12262

Prino, L. E., Pasta, T., Gastaldi, F. G. M., & Longobardi, C. (2016). The effect of autism spectrum disorders, down syndrome, specific learning disorders and hyperactivity and attention deficitson the student-teacher relationship. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 14(1), 89–106. https://doi.org/10.14204/ejrep.38.15043

Rodríguez-Ayán, M. N., & Ruiz, M. A. (2008). Atenuación de la asimetría y de la curtosis de las puntuaciones observadas mediante transformaciones de variables: Incidencia sobre la estructura factorial [Attenuation of the skewness and kurtosis of the scores observed through variable transformations: Incidence on the factorial structure]. Psicológica, 29, 205–227.

Rosanas, E., Ribas-Fitó, N., Batlle-Vila, S., Persavento, C., Alvarez-Pedrerol, M., Sunyer, J., & Forns, J. (2017). Sluggish cognitive tempo: Sociodemographic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics in a population of Catalan school children. Journal of Attention Disorders, 21(8), 632–641.

Rose, C. A., & Espelage, D. L. (2012). Risk and protective factors associated with the bullying involvement of students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Behavioral Disorders, 37(3), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/019874291203700302

Rose, C. A., & Gage, N. A. (2017). Exploring the involvement of bullying among students with disabilities over time. Exceptional Children, 83, 298–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402916667587

Rose, C. A., Monda-Amaya, L. E., & Espelage, D. L. (2011). Bullying perpetration and victimization in special education: A review of the literature. Remedial and Special Education, 32(2), 114–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932510361247

Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(2), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007

Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Björkqvist, K., Österman, K., & Kaukiainen, A. (1996). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group aggressive behavior. Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression, 22(1), 1–15.

Saracho, O., & Spodek, B. (Eds.). (2007). Contemporary perspectives on socialization and social development in early childhood education. IAP.

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P.M. (1994). Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In A. von Eye & C.C. Clogg (Eds.), Latent variables analysis: Applications for developmental research (pp. 399–419). Sage

Scheithauer, H., Hayer, T., Petermann, F., & Jugert, G. (2006). Physical, verbal, and relational forms of bullying among German students: Age trends, gender differences, and correlates. Aggressive Behavior, 32(3), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20128

Sointu, E. T., Savolainen, H., Lappalainen, K., & Lambert, M. C. (2017). Longitudinal associations of student–teacher relationships and behavioural and emotional strengths on academic achievement. Educational Psychology, 37(4), 457–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2016.1165796

Stefanek, E., Strohmeier, D., & Yanagida, T. (2017). Depression in groups of bullies and victims: Evidence for the differential importance of peer status, reciprocal friends, school liking, academic self-efficacy, school motivation and academic achievement. International Journal of Developmental Sciences, 11(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.3233/DEV-160214

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education.

Tanaka, J. S. (1993). Multifaceted conceptions of fit in structural equation models. In K. A. Bollen (Ed.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 10–39). Sage.

Turunen, T., Kiuru, N., Poskiparta, E., Niemi, P., & Nurmi, J. E. (2019). Word reading skills and externalizing and internalizing problems from Grade 1 to Grade 2—Developmental trajectories and bullying involvement in Grade 3. Scientific Studies of Reading, 23(2), 161–177.

Van der Ploeg, R., Steglich, C., & Veenstra, R. (2020). The way bullying works: How new ties facilitate the mutual reinforcement of status and bullying in elementary schools. Social Networks, 60, 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2018.12.006

Waasdorp, T. E., Monopoli, W. J., Horowitz-Johnson, Z., & Leff, S. S. (2019). Peer sympathy for bullied youth: Individual and classroom considerations. School Psychology Review, 48(3), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR-2017-0153.V48-3

Wanders, F. H., Van der Veen, I., Dijkstra, A. B., & Maslowski, R. (2020). The influence of teacher-student and student-student relationships on societal involvement in Dutch primary and secondary schools. Theory & Research in Social Education, 48(1), 101–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2019.1651682

Wiener, J. (2004). Do peer relationships foster behavioral adjustment in children with learning disabilities? Learning Disability Quarterly, 27(1), 21–30.

Wiener, J., & Schneider, B. H. (2002). A multisource exploration of the friendship patterns of children with and without learning disabilities. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30(2), 127–141. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014701215315

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Torino within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Berchiatti, M., Ferrer, A., Galiana, L. et al. Bullying in Students with Special Education Needs and Learning Difficulties: The Role of the Student–Teacher Relationship Quality and Students’ Social Status in the Peer Group. Child Youth Care Forum 51, 515–537 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-021-09640-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-021-09640-2