Abstract

Ni(II)-containing layered double hydroxides (LDHs) were synthesized with various methods with the intention of placing the Ni(II) ions in different positions in/on the LDH. Ni(II) was introduced as a lattice-modifier into CaAl-, CaFe- and MgAl-LDHs or in the interlayer space in form of a complex anion or as the divalent component of NiAl-LDH or as surface dopant. The materials were structurally characterized by various instrumental methods; however, the final proof of lattice modification was proven by the Suzuki–Miyaura and the Heck coupling reactions. Each as-prepared catalyst was active and selective towards the coupling products with or without various additives. They could be recycled except the surface-doped material, in which intense leaching of the Ni(II) content was observed on reuse.

Graphical Abstract

Ni(II)-containing LDHs are active and recyclable catalysts in the Suzuki and Heck coupling reactions—this is the final proof that the Ni(II) ions are constituents of the lattice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Layered double hydroxide (LDH) has several advantageous features facilitating wide range of applications possibilities. These are the large variety of salts, which can be applied for their preparation, the relative ease of their synthesis, the numerous methods available for this, the anion-exchange property—among the negatively charged layers having two metal ions most frequently, interlayer anions maintain charge neutrality [1]—, thus the possibility of post-synthetic modification [2,3,4,5].

Modification can be extended from ion exchange to that of the layers as well. On one hand, the crystal structure may be altered by introducing e.g., the modifier metal ion into the layer, typically during the synthesis of the LDH. On the other hand, the modifier metal ion may be deposited on the outer surface. The success of this latter modification can be checked easier than the previous one, instrumental methods may not be able to provide with the final proof.

In the experimental work leading to this contribution, Ni(II) ions were intended to place Ni(II) ions into four different positions of LDHs. They are surface doping, the interlayer space in form of anionic complexes, the layer as the divalent metallic component producing layered double hydroxide and the layer as part of its crystal structure, but only a minor third metal ion component producing layered triple hydroxides (LTHs). LTHs are not unprecedented, but they are significantly scarcer than LDHs.

The obtained materials were characterized by instrumental methods as well as two types of C–C coupling reactions, the Heck [6] and Suzuki–Miyaura [7] reactions investigating the recycling abilities of the solid substances. It was expected that this property is going to give, together with the instrumental methods, unambiguous information about the position of the Ni(II) ions.

Ni-containing materials offer potential and affordable option for substituting palladium-containing catalysts in homo- and heterocoupling reactions, e.g. in the Heck [8,9,10] as well as the Suzuki–Miyaura reaction [11,12,13].

In the last two decades, in order to reach the efficiency of palladium-containing materials, the investigations focused at the increase of the activity, selectivity and recycling ability of nickel-containing catalysts through varying synthesis parameters and/or the method of immobilization [14,15,16,17,18,19]. Full conversions were reported several times, and the immobilization efforts usually were successful. Nevertheless, outstanding selectivity and suppressed leaching could not been observed at the same time [20, 21].

Immobilization of homogeneous catalyst is a widely used approach, because heterogenized catalyst has the benefit of easy separation from the reaction mixture [22,23,24]. Furthermore, heterogeneous catalysts can usually be applied in flow reactions, which is a fundamental expectation for industrial applications [25]. In most cases, the active components are immobilized over inactive support with the only aim of achieving recyclability [26, 27]. However, simple adsorption-deposition is usually not adequate under more demanding conditions; leaching is very often a problem in liquid-phase reactions even at ambient temperature.

LDHs are layered compounds having (most often) di- and trivalent cations and hydroxide anions as constituents of the layers. The layers are basic in character and positively charged. This charge is compensated by partially or fully hydrated anionic species of varying complexities. Although many representatives can be found in nature, for use, they are usually synthesized. During the synthesis and/or post-treatment, their structures and thus their properties can be tailored to needs with relative ease.

In the experimental work leading to this contribution, various LDHs were modified with Ni(II) ions in different ways like adsorption-deposition onto the outer surface, insertion into the layers as new constituents or intercalating them in the form of anionic complexes. The modified materials were tested in the Heck and Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reactions. The results obtained are communicated in the followings.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials and Methods of Synthesis

Nitrate salts containing maximum amount of crystal water (NiCl2·6H2O, Ni(NO3)2·H2O), Ca(OH)2, Mg(NO3)2·6H2O, Al(NO3)3·9H2O and NaOH were applied as precursors. All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. N2 atmosphere was used during all manipulations to avoid carbonate intercalation from airborne CO2 (it would prevent any interlayer modification).

All the reagents, auxiliary materials and solvents used in the Heck and Suzuki–Miyaura reactions (4-bromoanisole, styrene, phenylboronic acid, bromobenzene, pyridine, piperidine, KOAc, K2CO3, Na2CO3, tetrabutylammonium chloride, ethanol, toluene) were the products of Sigma-Aldrich Co., and were used as received.

The syntheses of CaAl-LDH and Ni(II)-containing LDHs were performed by the co-precipitation method [2]. It is the dropwise addition of an aqueous solution of the precursor salts (100 cm3) containing bivalent: Ca(II)/Ni(II)/Mg(II) (c(Me(II)) = 0.3 M); and trivalent: Al(III)/Fe(III) (c(Me(III) = 0.15 M)) nitrates to a solution of sodium hydroxide kept at 35 °C. Synthetic parameters like pH, temperature and the concentration of Ni(II) ions, when they were modifiers, were varied systematically. Details using the synthesis of Ni(II)Ca(II)Fe(III)-LDH as the example are seen in SFigs. 1–4 of the Supplementary Material (notations for the figures, schemes and tables in the Supplementary Material file starts with ‘S’). After the addition of the components, the suspension was stirred for 24 h, filtered, washed with distilled water and dried at 65 °C. The Ni(II)-cysteinate complex intercalated system was prepared the way described in one of our previous paper [28]. Here, for the sake of completeness, we repeat the recipe briefly: 2.5·10−4 mols of L-cysteine were used for the intercalation in anionic form. Intercalation occurred at pH = 7.1 from slightly basic aqueous ethanolic solution. The Ni(II) ions were introduced in aqueous solution to the intercalated system. During the synthesis, the nominal ratio of amino acid and Ni(II) ions was 1:4, which became 2:1 in the final product.

A CaAl-LDH sample was doped with Ni(II) ions as follows. First, 0.5 g of LDH was added to 0.075 g of nickel(II) oxide. They were milled together in a Retsch MM 400 mixer mill without solvent (dry milling). Milling was continued after adding 0.75 cm3 distilled water (wet milling) to the grinding jar (ball/sample ratio of 100, ν = 1.6 Hz, milling time 1 h).

2.2 Characterization of the Catalysts

X-ray diffraction patterns of powdered samples were recorded at room temperature in air using by a Miniflex II diffractometer (Rigaku, Japan) using CuKα radiation (λ = 0.15418 nm) at 40 kV and 30 mA. The development of the Ni(II)Ca(II)Al(III)-, Ni(II)Mg(II)Al(III)- and Ni(II)Al(III)-LDH samples are displayed in SFigs. 5–7.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were taken on an S-4700 scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi, Japan) with accelerating voltage of 10–18 kV. Few droplets of the sample suspended in ethanol were placed on a carbon-coated alumina grid followed by evaporation at ambient conditions. Hexagonal platelet-like morphologies could be observed for Ni(II)Ca(II)Fe(III)-, Ni(II)Ca(II)Al(III)-, Ni(II)Mg(II)Al(III)- and Ni(II)Al(III)-LDH samples in SFig. 8.

IR spectra were measured in the diffuse reflectance mode. The instrument was a BIO-RAD Digilab Division FTS-65A/896 FT-IR spectrophotometer with 4 cm−1 resolution. The 4000–600 cm−1 wavenumber range was recorded, but the most relevant 1850–600 cm−1 range is displayed (SFig. 9) and discussed. 256 scans were collected for each spectrum.

The amounts of metal ions before and after the reactions were measured by ICP–AES on a Thermo Jarell Ash ICAP 61E instrument. Before measurements, few milligrams of the samples measured by analytical accuracy were digested in 1 cm3 cc. HNO3; then, they were diluted with distilled water to 50 cm3 and filtered.

2.3 Testing the Catalytic Activity

The catalytic activities of the Ni(II)-containing substances were studied in the Heck (SScheme 1) and Suzuki–Miyaura (SScheme 2) cross coupling reactions, in the liquid phase. In order to find the optimal conditions, the reaction time (1–120 h), the amount of the catalyst (5–60 mg), the applied bases (none, pyridine, piperidine, KOAc, K2CO3, Na2CO3 Al2O3) and the solvent or solvent mixtures (dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), dimethylformamide (DMF), toluene, ethanol, 50/50% or 85/15% water-toluene solvent mixtures) were altered (STables 1–4 for the Heck and STables 5–8 for the Suzuki–Miyaura reactions). The optimum conditions for the Heck reaction were as follows. The amounts of the variously prepared Ni(II)-containing materials were often different: 5 mg for the NiO-doped and the NiAl-LDH, 15 mg for the NiCaFe-LDH, 30 mg for the Ni-cysteinate–CaAl-LDH intercalated system, the NiCaAl-LDH and the NiMgAl-LDH. The other parameters were the same for each run: 5 cm3 of water-toluene 50/50% mixture, 251 µl of 4-bromoanisole (2.0 × 10−3 mol), 275 µl of styrene (2.4 × 10−3 mol), 275 mg of KOAc (2.8 × 10−3 mol) or none, 120 h reaction time at 323 K in a batch reactor.

For the Suzuki–Miyaura reaction, the optimum reaction conditions were as follows. The amounts of the variously prepared Ni(II)-containing materials were often different: 5 mg for the surface-anchored NiO and the NiAl-LDH, 15 mg for the NiCaFe-LDH, 25 mg for the intercalated system, the NiCaAl-LDH and the NiMgAl-LDH. The other parameters were the same for each run: 3.5 cm3 of water-toluene 85/15% mixture, 105 µl of bromobenzene (1.0 × 10−3 mol), 146 mg of phenylboronic acid (1.2 × 10−3 mol), 246 µl of piperidine (2.5 × 10−3 mol) or none, 120 h reaction time at 323 K.

In a run for both reaction types 278 mg (1.0 × 10− 3 mol) and 222 mg (8.0 × 10− 4 mol) tetrabutylammonium chloride phase-transfer catalyst was used in the Heck and the Suzuki–Miyaura reactions, respectively. The reaction times were 8 h for both reaction types.

The catalysts were regenerated after use in the Suzuki–Miyaura reaction by applying calcination at 450 °C for 5 h, then rehydrating the samples in distilled water at room temperature for 2 h.

The reaction mixtures were analyzed quantitatively by a Hewlett–Packard 5890 Series II gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with flame ionization detector, using an Agilent HP-1 column and the internal standard technique. The temperature was increased in stages from 50 to 300 °C. The products were identified via using authentic samples.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Characterization of the LDHs

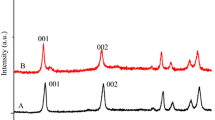

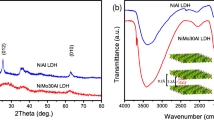

The resulting materials have X-ray diffractograms typical of LDHs [3] (Fig. 1). The observed shift in baseline may be linked to the fluorescence of nickel centers. X-ray diffractometry is suitable to verify the success of intercalation. Intercalation does not destroy the layered structure, only the interlayer distance alters. The shift in the position of the first reflection lower than that in the pristine LDH is a sure sign of intercalation. If it moves towards lower angles, the interlayer distance grows. Indeed, the 001 reflection of CaAl-LDH (Fig. 1, trace D) shifted from 10.5° to 10.2° in the Ni-cysteinate–CaAl-LDH sample (Fig. 1, trace E). The XRD pattern of the NiO-doped CaAl-LDH sample (Fig. 1, trace F) indicates that the layered structure remained intact, and the NiO species were incorporated as non-crystalline components.

The IR spectrum of the Ni-cysteinate-containing CaAl-LDH sample verified the presence of organic material in the sample. A comparison of spectra A and B in SFig. 9 reveals that all the new peaks in spectrum B belongs to cysteinate [4]. For instance, the peaks at 1630 and 1460 cm−1 are the shifted carboxylate vibrations.

The samples prepared were analyzed for their cation content, and their molar ratios were calculated. Data listed in Table 1 indicate that each sample contained Ni(II), and the experimentally obtained molar ratios were close to the nominal ones. The TOF (turnover frequency) values were calculated based on the results of ICP–AES measurements (see later).

3.2 Investigating the Catalytic Activities

Maximum conversions for the Suzuki–Miyaura and Heck reactions, are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. The rates of both reaction types were significantly enhanced by using water-toluene solvent mixture, similarly to the reports of Zhao et al. [5, 29]. The observation may be due to the increased activity of the LDH in a somewhat polar medium. It should be mentioned that the delaminating solvents could also be successfully applied; however, they make recycling more difficult by disrupting the LDH structure [30]. Let us note that the applied solvent mixture is more benign to the environment than DMF or DMSO, which are the usually applied solvents in these reactions.

It is to be noted that the basic character of the LDH was enough for both reaction types to proceed with acceptable conversions. However, addition of an auxiliary base increased the conversions considerably. In this respect, KOAc [31, 32] and piperidine were found to be the optimum choices for the Heck and the Suzuki–Miyaura reactions, respectively.

The use of phase-transfer catalyst dramatically attenuated the reaction time in both reaction types reaching similar conversions. The addition of the quaternary ammonium salt decreased the time needed for the departure of the products from the LDH surfaces, i.e. accumulation of the products over the catalysts did not occur [33,34,35].

The solubility of the products may also play a role in the base-aided step. During the Suzuki–Miyaura reaction, the base takes part in the reaction at early stages (before and in the transmetallation step), therefore, it is bonded in a reactant-like structure being soluble in both polar and apolar solvents. Thus, both organic and inorganic bases are applicable. However, in the Heck reaction, the base enters the reaction cycle after for the regeneration of the catalyst, therefore, only bases soluble in polar solvents can support the reaction efficiently [36, 37].

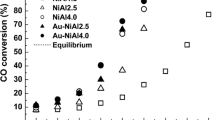

In the multicomponent LDHs, the Ni(II) centers promoted the coupling reactions with adequate efficiency. Although the NiAl-LDH displayed comparable activities to those of the other samples, the addition of an auxiliary base and phase-transfer catalyst did not enhance the conversions. The sample having the Ni(II) ions intercalated, i.e. in difficult to access positions, was moderately active. However, the NiO-doped sample exhibited outstanding activities, comparable to those of the iron-containing catalyst. It is to be noted that in the iron-containing multicomponent LDH the Fe(III) ions also have catalytic activity in the coupling reactions [38, 39].

In judging catalytic efficiency, the recycling abilities are crucial. Conversion values in repeated runs are collected in Tables 4 and 5.

The results revealed that all samples except the NiO-doped one kept their activities during recycling. This means that in these samples, the Ni(II) ions are integral parts of the catalysts, either fixed in the layer lattice as one of its constituents (NiCaAl-, NiMgAl-, NiCaFe- and NiAl-LDHs) or firmly immobilized in the interlayer space of the LDH (Ni(II)-cysteinate–CaAl-LDH). The seemingly most efficient NiO-doped sample suffered dramatic activity losses in the repeated runs due to leaching out the Ni(II) content, verified by ICP–AES measurements as well.

The X-ray diffractograms revealed that the LDH structure is kept in all the systems after the reaction, and leaching of the Ni(II) ions was a problem only with the NiO-doped sample. The reflections in the diffractogram of, e.g., the NiAl-LDH widened and the crystallinity of the LDH decreased indicating that its structure was distorted by the reaction. In the multicomponent systems, no leaching of the Ni(II) ions was observed either proving that the Ni(II) ions were incorporated in the lattice.

Between the repeated runs, the catalysts were only rinsed with the solvent; however, a full-scale regeneration was also performed, and the reconstructed LDHs, except the NiO-doped one, performed similarly or somewhat even better in the Suzuki–Miyaura reaction than the freshly-made samples.

The catalytically active recyclable materials exhibited high selectivities towards the coupling products in both reaction types. In this respect, the intercalated system displayed the highest selectivities, over 90% in both reaction types. It seems that the hindered active centres were necessary to reach these very high yields.

4 Conclusions

The co-precipitation method proved to be suitable for anchoring the Ni(II) as the constituent of the layer lattice of CaFe-, CaAl- and MgAl-LDHs. The Ni(II) content and the LDH structure were verified by ICP–AES measurements and X-ray diffractometry, respectively. The final proof of lattice anchoring was obtained through coupling reactions, in which no Ni(II) ion leaching was observed, and the recycling ability was found to be excellent. Although the as-prepared LDH sample surface-doped by Ni(II) ions had excellent activity, during recycling, it decreased dramatically due to serious Ni(II) leaching. The NiAl-LDH sample was less active than the lattice-anchored ones, but its performance remained steady in the repeated runs, and it also kept its layered structure.

References

Evans GD, Slade RCT (2006) Structural aspects of layered double hydroxides. Struct Bond 119:1–87

Khan AI, O’Hare D (2002) Intercalation chemistry of layered double hydroxides: recent developments and applications. J Mater Chem 12:3191–3198

Tóth V, Sipiczki M, Pallagi A et al (2014) Synthesis and properties of CaAl-layered double hydroxides of hydrocalumite-type. Chem Pap 68:633–637

Chen Q, Shi S, Liu X et al (2009) Studies on the oxidation reaction of l-cysteine in a confined matrix of layered double hydroxides. Chem Eng J 153:175–182

Zhao F, Shirai M, Arai M (2000) Palladium-catalyzed homogeneous and heterogeneous Heck reactions in NMP and water-mixed solvents using organic, inorganic and mixed bases. J Mol Catal A 154:39–44

Heck RF, Nolley JP (1972) Palladium-catalyzed vinylic hydrogen substitution reactions with aryl, benzyl, and styryl halides. J Org Chem 37:2320–2322

Miyaura N, Suzuki A (1979) Stereoselective synthesis of arylated (E)-alkenes by the reaction of alk-1-enylboranes with aryl halides in the presence of palladium catalyst. J Chem Soc Chem Commun 19:866–867

McGuinness DS, Cavell KJ (1996) Zerovalent palladium and nickel complexes of heterocyclic carbenes: oxidative addition of organic halides, carbon–carbon coupling processes and the Heck reaction. Organometallics 18:1596–1605

Alberico D, Scott ME, Lautens M (2007) Aryl–Aryl bond formation by transition-metal-catalyzed direct arylation. Chem Rev 107:174–238

Ohtaka A, Sansano JM, Najera C et al (2015) Palladium and bimetallic palladium–nickel nanoparticles supported on multiwalled carbon nanotubes: application to carbon–carbon bond-forming reactions in water. ChemCatChem 7:1841–1847

Weires NA, Baker EL, Garg NK (2016) Nickel-catalysed Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of amides. Nat Chem 8:75–79

Malapit CA, Bour JR, Brigham CE et al (2018) Base-free nickel-catalysed decarbonylative Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of acid fluorides. Nature 563:100–104

Payard P-A, Perego LA, Ciofini I et al (2018) Taming nickel-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura coupling: a mechanistic focus on boron-to-nickel transmetalation. ACS Catal 8:4812–4823

Phan NTS, van der Sluys M, Jones CW (2006) On the nature of the active species in palladium catalyzed Mizoroki–Heck and Suzuki–Miyaura couplings—homogeneous or heterogeneous catalysis, a critical review. Adv Synth Catal 348:609–679

Yin L, Liebscher J (2007) Carbon–carbon coupling reactions catalyzed by heterogeneous palladium catalysts. Chem Rev 107:133–173

Astruc D (2007) Palladium nanoparticles as efficient green homogeneous and heterogeneous carbon–carbon coupling precatalysts: a unifying view. Inorg Chem 46:1884–1894

Bhanage BM, Arai M (2001) Catalyst product separation techniques in Heck reaction. Catal Rev Sci Eng 43:315–344

Trzeciak AM, Ziolkowski JJ (2007) Monomolecular, nanosized and heterogenized palladium catalysts for the Heck reaction. Coord Chem Rev 251:1281–1293

Makhubela BCE, Jardine A, Smith GS (2011) Pd nanosized particles supported on chitosan and 6-deoxy-6-amino chitosan as recyclable catalysts for Suzuki–Miyaura and Heck cross-coupling reactions. Appl Catal A 393:231–241

Horniakova J, Raja T, Kubota Y et al (2004) Pyridine-derived palladium complexes immobilized on ordered mesoporous silica as catalysts for Heck-type reactions. J Mol Catal A 217:73–80

Hajjami M, Cheraghi M (2016) Synthesis of Pd-complex supported on MCM-41 and its catalytic activity for the C–C coupling reactions. Catal Lett 146:1099–1106

Wight A, Davis M (2002) Design and preparation of organic-inorganic hybrid catalysts. Chem Rev 102:3589–3614

Astruc D, Lu F, Aranzaes JR (2005) Nanoparticles as recyclable catalysts: the frontier between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis. Angew Chem Int Ed 44:7852–7872

Ye R, Zhao J, Yuan B et al (2017) New insights into aldol reactions of methyl isocyanoacetate catalyzed by heterogenized homogeneous catalysts. Nano Lett 17:584–589

Noël T, Buchwald SL (2011) Cross-coupling in flow. Chem Soc Rev 40:5010–5029

Iglesia E, Reyes SC, Madon RJ et al (1993) Selectivity control and catalyst design in the Fischer-Tropsch synthesis: sites, pellets and reactors. Adv Catal 39:221–302

Xin HL, Alayoglu S, Tao R et al (2014) Revealing the atomic restructuring of Pt–Co nanoparticles. Nano Lett 14:3203–3207

Varga G, Timár Z, Muráth S et al (2017) Ni-amino acid–CaAl-layered double hydroxide composites—construction, characterization and catalytic properties in oxidative transformations. Top Catal 60:1429–1438

Zhao F, Shirai M, Ikushima Y et al (2002) The leaching and re-deposition of metal species from and onto conventional supported palladium catalysts in the Heck reaction of iodobenzene and methyl acrylate in N-methylpyrrolidone. J Mol Catal A 180:211–219

da Conceiçã Silva A, Dias Senra J, Ferreira de Souza AL et al (2013) A ternary catalytic system for the room temperature Suzuki-Miyaura reaction in water. Sci World J. Article ID 456789: 1–8

Barnard CFJ (2008) Palladium-catalyzed carbonylation—a reaction come of age. Organometallics 27:5402–5422

Goossen LJ, Rodríguez N, Melzer B et al (2007) Biaryl synthesis via Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative coupling of aromatic carboxylates with aryl halides. J Am Chem Soc 129:4824–4833

Jung JY, Taher A, Hossain S et al (2010) Highly active heterogeneous palladium catalyst for the Suzuki reaction of heteroaryl chlorides. Bull Korean Chem Soc 31:3010–3012

Proch S, Mei Y, Rivera Villanueva JM et al (2008) Suzuki- and Heck-type cross-coupling with palladium nanoparticles immobilized on spherical polyelectrolyte brushes. Adv Synth Catal 350:493–500

Nemygin NA, Nikoshvili LZH, Matveeva VG et al (2016) Pd-nanoparticles confined within hollow polymeric framework as effective catalysts for the synthesis of fine chemicals. Top Catal 59:1185–1195

Miyaura N, Suzuki A (1995) Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of organoboron compounds. Chem Rev 95:2457–2483

Cabri W, Candiani I (1995) Recent developments and new perspectives in the Heck reaction. Acc Chem Res 28:2–7

Zhu N, Zhao J, Bao H (2017) Iron catalyzed methylation and ethylation of vinyl arenes. Chem Sci 8:2081–2085

Sho N, Hikaru T, Masaharu N (2017) Iron-catalyzed methylation of arylboron compounds with iodomethane. Chem Lett 46:711–714

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Szeged (SZTE). This work was supported by the Hungarian Government and the European Union through grant GINOP-2.3.2-15-2016-00013. The financial help from the Ministry of Human Capacities of Hungary via grant 20391-3/2018/FEKUSTRAT is highly appreciated. One of us, G. Varga thanks for the postdoctoral fellowship under the grant PD 12818.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

10562_2019_2742_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplementary material 1 Supporting Information contains information about the optimization of the LDH synthesis through an example as well as the optimization steps of the two coupling reactions. (DOCX 1081 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Varga, G., Karádi, K., Kukovecz, Á. et al. Placing Ni(II) Ions in Various Positions In/On Layered Double Hydroxides: Synthesis, Characterization and Testing in C–C Coupling Reactions. Catal Lett 149, 2899–2905 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10562-019-02742-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10562-019-02742-6