Abstract

Involuntary youth transport (IYT) is a controversial practice used to admit adolescents into residential care. Critics point out that IYT is in need of regulation and is best used as a last resort. This article examines the risks and benefits of IYT, especially the longterm effects on the client, in order to ensure that all facets of a client’s treatment are trauma-informed and guided by research-based practices and ethical principles. Practices that re-traumatize youth need to be replaced with informed practices that facilitate positive outcomes. This article utilizes an ethical decision-making framework developed for behavioral health professionals to assess and improve the ethical use of IYT. Based on this ethical framework, a more effective and collaborative model is presented that results in less restrictive approaches, greater levels of willingness by the adolescent to enter treatment, and trauma-informed management of difficult emotional or physical behaviors. This model also guides professionals and caregivers on how to proceed when IYT services are deemed necessary. The article presents past research and addresses ethical guidelines and best practices for IYT. Steps for practitioners and future directions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Behavioral health treatment for youth in therapeutic settings should be guided by research-based, ethical practices. While some youth may require involuntary treatment, these practices should be trauma-informed with minimal use of procedures that may induce re-traumatization. Such approaches are especially important for youth in residential care where rates of complex trauma are high. Briggs et al.’s (2012) analyses of data from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network found that 92% of youth in residential care reported a history of multiple traumatic events. Trauma-informed residential care involves: (a) recognizing that a history of trauma is common in youth, (b) acknowledging the effects of trauma are widespread, affecting not only the lives of the youth but also family members and others involved in their care, and (c) incorporating this knowledge into policies, procedures, and practices that reduce re-traumatization (SAMHSA, 2019).

According to Mercer (2017), potentially harmful psychological treatments that inflict physical or emotional harm or cause lasting psychological damage must be identified and avoided. Safeguarding human rights and promoting self-determination are also important issues for youth in residential care, especially when treatment is involuntary. These principles are also fundamental to social work practices that prioritize a person’s right to self determination (NASW, 2017). When taken together, youth residential care should be evidence-based, trauma informed, protect the rights and freedoms of youth, and promote self-determination.

Protecting the human rights of children and adolescents is a growing concern in residential care. The American Bar Association (2007) and the U.S. Government Accountability Office (2008) have both called for greater oversight and policy to protect youth in involuntary residential care, highlighting concerns of abuse related to involuntary treatment practices. These concerns have recently become more pronounced as public figures and others have come forward in national news and social media campaigns. These individuals have cited personal instances of abuse related to involuntary treatment practices in residential care (Kennedy, 2020). In most countries, youth can be legally transported involuntarily (e.g., against their consent) into a treatment program when certain conditions exist under the authority of their legal caregivers (Jost, 2006). Australia (McMillan et al., 2019), Canada (Clark et al, 2019; Hamilton et al., 2020), India (Kelly, 2016), Finland (Askola et al., 2018), and the United Kingdom (Zigmond, 2017) are examples of countries that have established governmental guidelines and principles regarding the use of involuntary transport for individuals experiencing behavioral health issues. In the U.S., however, there is no existing federal legislation for IYT. This leaves the responsibility of oversight to the individual states, which unfortunately is often overlooked (Kerwin et al., 2015). For this reason, critics of the practice have pointed out that this industry “operates on the fringes of existing law” (Robbins, 2014, p. 563).

Defining Involuntary Youth Transport

Involuntary youth transport (IYT) is a controversial practice used to involuntarily admit adolescents into residential care. Before defining youth transport, it is important to examine two widely divergent examples of this practice. The two actual scenarios presented provide evidence of this variance.

Scenario #1

Our daughter was depressed, talking about suicide and became quickly oppositional when we attempted to talk with her. She would angrily leave the house and not come home for days at a time. She vehemently denied substance use and had recently passed a drug test administered by the courts following her school finding heroin in her locker. She insisted she wasn’t using it and that a friend had asked her to hold it for him.

Due to her suicidal ideation, leaving home with no contact, and our fear for her safety, we decided to hire a transport team to pick her up and take her to treatment. Three weeks later, we were finally able to unlock her phone and discovered she had gotten involved with an older man in his 20s. She had been using heroin and he was passing her around for sex with his friends for drugs. Three days before the transport, she had plans to leave the state with him. Authorities also discovered that he was associated with suspected sex trafficking and was already being watched by authorities (Parents of a 16 year daughter).

Scenario #2

I will never be able to forget the night my room was invaded by two “goons.” Before I could resist or understand what was occurring, my hands were pinned behind my back. With my mother sobbing off in the corner of the room, my father announced that these two men were going to take me to a place where I could get the help I needed and then left the room. These men told me that if I did what they said, the trip would be much easier for all of us. When I asked questions about where we were going, I was informed I would be told when we got there. It really felt like I was being kidnapped. While never outwardly stated, it felt as if I could be raped at any time these two men wanted.

Since that time, I can’t fall asleep in a bedroom if the lights or a bright night light are not left on. I have never been able to forgive my parents for what they put me through during that evening (16 year old girl sharing her transport experience).

IYT typically occurs when a third-party service is hired by the caregivers to physically escort an adolescent into residential care (Becker, 2010; Bettmann et al., 2013; Tucker et al., 2015). The process usually consists of two transport staff for one adolescent client. IYT staff are often trained in a variety of de-escalation and therapeutic techniques to manage client behaviors through non-violent crisis intervention (Safe and Sound Youth Transportation, 2020). Staff may also be trained in CPR and First Aid. IYT procedures are varied, ranging from verbal elicitation to implied threat and overt physical force (e.g., therapeutic holds, physical restraints, and in some cases mechanical restraints) (Tucker et al., 2015).

The exact prevalence of IYT is unknown, with recent estimates suggesting the use of youth transport services vary from 0% to as high as 83% across out-of-home behavioral healthcare programs (mean and median scores were 53%) (Gass, 2018). Assessment and implementation of IYT is also unclear, with Persi et al. (2016) and Bolt (2016) suggesting IYT may be most effective in the following conditions: (a) the youth is in the precontemplation stage of change, (b) unsafe parent–child dynamics exist in this relationship, (c) parents lack the abilities to carry out the transport, and (d) when there are concerns for the physical safety of the child. Systemic factors may also drive the IYT referral process. For example, private for-profit residential care facilities may be inclined to encourage IYT in order to maintain their census.

The actual use of IYT is a hotly debated topic. Chatfield et al. (2021) suggested “forcible transport” may be a more appropriate description than IYT, stating, “the practice relies on the implicit or explicit use of force and because the voluntary or involuntary nature of such practices may be less salient for young people who have no legal right to refuse treatment” (p. 134). However, Chatfield et al.’s (2021) research failed to find any association between forcible transport and youths’ perceived quality of experience in residential care. IYT has also been criticized as a form of social control or “strong-arm rehabilitation” that can elicit traumatic responses (Mooney & Leighton, 2019; Rosen, 2021). Robbins (2014) and Szalavitz (2006) described such practices as being fraught with contention and coercion which pose a greater risk of harm than benefit to adolescents.

Other professionals emphasize that when properly implemented, coercive admission practices, including IYT, may be a safe resource for youth needing treatment and these practices do not negatively impact treatment outcomes (Hamilton et al., 2020; Hardy, 2011; Tucker et al., 2018). When ascertaining the risks and benefits of coercive treatment, Hardy (2011) reasoned that adolescent treatment coercion “can provide access to a safe treatment environment for reflection and recovery of mental competency, free from negative outside pressure and potential substance abuse” (p. 92). Persi et al. (2016) found that IYT was a safe and beneficial option for youth, particularly for youth “in crisis with severe risk, serious problems, and lower capacity to engage voluntarily” (Persi et al., 2016, p. 70).

Prior Research

Empirical research regarding IYT has only recently emerged in residential care, primarily in the context of wilderness therapy programs. Tucker et al. (2015) examined 165 adolescents in a single wilderness therapy program, with 50.9% entering via IYT. Their research found that transported adolescents presented higher levels of dysfunction at admission in terms of socially related behavioral problems. No differences were reported in terms of readiness to change at admission or treatment outcomes. These findings suggested IYT did not affect treatment outcomes given that transported adolescents experienced positive change equivalent to non-transported adolescents (Tucker et al., 2015).

In Tucker et al.’s (2018) study, which further examined transport in relation to treatment outcomes in 645 adolescents across four wilderness program sites, 64.5% entered via IYT. In contrast to the previous study, this research found similar overall dysfunction levels among adolescents at admission irrespective of IYT. However, this research replicated the previous study’s findings in terms of adolescents experiencing similar positive treatment outcomes regardless of IYT. While cautioning the importance of utilizing a quality transport service, these findings suggest that IYT may support treatment, by providing youth an opportunity to experience similar positive outcomes to those who are not transported (Tucker et al., 2018).

Harper et al. (2021) used exploratory data from the NATSAP Research Database to suggest caution in generalizing the research findings in the studies examining the quantitative findings regarding IYT. Criticisms levied by these authors present the need for more definitive procedures to produce valid and generalizable outcomes on what is occurring in IYT experiences.

Hardy’s (2021) examined the elements of perceived coercion, voice (i.e., the opportunity to express opinion and belief that opinion was valued), and negative pressures (i.e., the use of implicit or overt force) in relation to IYT in a cross-sectional analysis of 105 adolescents entering a single wilderness therapy program. Initial analyses are showing statistically significant correlations between youths’ perceived coercion and the use of IYT, with negative pressures and voice showing an indirect effect on this relationship. In essence, youth who entered treatment via IYT reported higher perceived coercion and negative pressures than their counterparts. However, when youth entered via IYT reporting a level of high voice during the process, they also reported reduced perceived coercion. This same finding existed for negative pressures, but with fewer reports of negative pressures being associated with reduced perceived feelings of coercion. While more research is needed, these findings support the reasoning that whether or not IYT is perceived as a negative experience depends not only on physical and emotional safety, but also on other contextual factors, such as voice and negative pressures (2021). This reasoning is also consistent with previous findings in the adult and adolescent psychiatric literature on involuntary admissions and perceived coercion (Hoge et al., 2001; Nyttingnes et al., 2018; O’Donoghue et al., 2014; Opsal et al., 2016; Winick, 2008).

However these quantitative findings may not tell the full story. Client voice is concerningly absent from quantitative studies; therefore qualitative methodologies are needed to fully understand the process of IYT from the youth’s perspective. According to a recent publication by Dobud (2021), the process of being transported involuntarily was highly traumatizing to adolescent clients, even leading to a diagnosis of PTSD in one case example. Dobud’s research focused on the stories of nine youth who experienced transports that occurred without the youth’s knowledge in the middle of the night when they were sleeping. This type of transport seems to go beyond perceived coercion and lends itself more to the definition of kidnapping posited by Robbins (2014). Given the potential re-traumatization of these practices, it is essential to consider the ethics of involuntary treatment in general.

Ethical Considerations for Involuntary Treatment

Paternalism is the traditional, ethical justification for involuntary treatment methods, such as IYT, in behavioral healthcare (O’Brien & Golding, 2003; Seo et al., 2013). According to paternalism, the decision for involuntary treatment is made out of benevolence or for a person’s own good when they are considered, “incompetent to make decisions for themselves or to lack autonomy” (O’Brien & Golding, 2003, p. 170). Paternalism is reasoned to occur more frequently for adolescents beleaguered by behavioral health problems as they are often dependent on their caregivers (Ellila et al., 2008; Hamilton et al., 2020). O’Brien and Golding (2003) also point out that paternalism is used as a default justification with minimal assessment into whether it is needed.

Paternalism should never replace clinical assessment to accurately determine if involuntary treatment is needed, especially given research that showed that involuntary treatment can negatively affect future help-seeking behavior and subsequent trust in mental health professionals (Jones et al., 2021). Clinicians should proceed with caution, and if involuntary treatment is necessary, Jones et al. believe clients must be given ample opportunities to process their involuntary treatment with professionals, in order to avoid these negative effects. Jones et al. also advocate for trauma-informed and patient-centered care in involuntary treatment settings, so as not to re-traumatize clients.

In the context of IYT, Persi et al. (2016) believe this practice may be beneficial for highly acute youth, but also emphasize a key caveat: “decisions to use involuntary referrals are subject to the influence of practice habits and service pressures beyond needs for immediate safety, problem severity, and incapacity. Such non-clinical influences may lead to excessive and inappropriate use” (p. 72). According to Mercer (2017), these non-clinical influences may also come from parents and other professionals involved in a youth’s life.

Considering these factors, along with the limited research on IYT and inconsistent legislation, the appropriate use of IYT rests heavily on professional ethics. In this vein, Cratsley and Radden (2019) labeled the use of coercive measures like IYT, “to be the defining issue of mental health ethics” (p. 26). Likewise, Pelto-Piri et al. (2016) and Ellila et al. (2008), have called for the development of ethical guidelines for involuntary treatment practices that provide a foundation for selecting the most appropriate course of action based on the relative context of the person's life and the resulting effect of choices to society as well as the person. These guidelines may also offer a strong foundation for policy and research.

Developing Ethical Guidelines for IYT

Developing ethical guidelines for the use of IYT is an essential step toward preventing harm and safeguarding the rights of the children and adolescents entering residential care via IYT. While no formal ethical guidelines for IYT currently exist, behavioral health professionals are ethically obligated to challenge the implicit support for involuntary treatment (Maylea, 2017). Professional organizations such as the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) provide ethical guidelines for clinical practice. According to the NASW Code of Ethics (2017), “Social workers respect and promote the right of clients to self-determination and assist clients in their efforts to identify and clarify their goals.” (p. 2). Social work ethical standards do not explicitly discuss IYT, however they do endorse the need for involuntary treatment in situations where clients’ actions or potential actions pose a serious, foreseeable, and imminent risk to themselves or others.” (NASW, 2017).

Consistent with these principles, O’Brien and Golding (2003) provided a framework around the principle of least coercion, especially when paternalism is the primary justification for IYT. This framework includes three steps, including determining:

-

1.

If the [person] is incompetent to make the decision.

-

2.

If the harm prevented and benefit provided outweighs the harm caused by the coercion.

-

3.

The least coercive intervention that will promote good or prevent harm is used (O’Brien & Golding, 2003, p. 172).

Method

The purpose of this article was to present a working model for examining the following questions:

-

(1)

How can youth be motivated to seek treatment in an ethical manner?

-

(2)

If treatment is refused, when is IYT ethically warranted?

-

(3)

If IYT is warranted, how can it be ethically implemented?

In order to answer these questions, Gass et al.’s (2020) five-step ethical framework for behavioral healthcare programs was applied to the context of IYT.

Five-Step Ethical Framework

This framework involves a five-step process for examining the ethics of professional practice and guiding practitioners facing ethical dilemmas (Gass et al., 2020). Origins of this framework emanate from the development of the ethical code of the adventure therapy professional subgroup of the Association for Experiential Education in 1992, with support from the American Psychological Association (APA) and the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy (AAMFT) (Gass, 1993). This ethical decision-making framework has continued to evolve over the past 30 years, using the intersecting perspectives of three sources of ethical theory common in behavioral health: principle ethics, virtue ethics, and feminist ethics (Hill et al., 1998; Jordan & Meara, 1990; Kitchener, 1984). In this framework, ethical dilemmas are resolved by progressing through the designated steps until a proposed action is determined to be ethical or not. If a decision cannot be made at a certain step, the practitioner proceeds to the next step until a decision can be made. This is not just a binary choice as conditions can be adapted to make the ethical decision more appropriate.

-

Step 1: Intuition—based on your professional experience, what makes ordinary moral sense?

-

Step 2: Option listing—list the potential strengths and weaknesses, outcomes, and potential ramifications of each option.

-

Step 3: Ethical codes of conduct—examine ethical behaviors in the field through established ethical codes of conduct.

-

Step 4: Ethical principles—use well-established ethical principles that seek to protect the interests and welfare of all people involved.

-

Step 5: Ethical theories—examine situation through ethical theories of balancing [i.e., that brings the least avoidable harm to all parties involved or produces the greatest happiness for the greatest number of individuals (Mill, 1975)] and universalizability [i.e., apply the same ethical actions across similar situations (Kant, 1964)].

In determining an ethical decision about IYT, the loss of client autonomy alone is enough to necessitate moving directly from Step 1 to Step 2. In Step 2, professionals brainstorm possibilities, values, strengths, and weaknesses of IYT, as part of an overall clinical risk assessment. These arguments have been highlighted in the literature, but it is important to review them while moving through the ethical decision-making process. Potential benefits of IYT include: reducing safety risks during transport and increasing access to needed treatment for acute youth (Persi et al., 2016). Conversely, potential consequences of IYT include: the violation of human rights and self determination (American Bar Association, 2007; Persi et al., 2016), overuse of IYT for non-acute youth (Persi et al., 2016), and re-traumatization (Mooney & Leighton, 2019; Rosen, 2021).

Given the implications of potential benefits as well as risk of harm, the decision-making process advances to Step 3. The third step examines potential actions through currently established ethical guidelines. While the NASW, along with other professional associations, such as the American Psychological Association (APA), Association of Experiential Education (AEE)’s Therapeutic Adventure Professional Group (TAPG) and the AEE/OBH accreditation program, have developed ethical guidelines, none of these organizations’ guidelines specifically address IYT (AEE, 2018; Gass et al., 2020). As a result, the decision-making process advances to the fourth step of ethical principles.

Ethical principles are “enduring beliefs about specific modes of conduct or end-states of existence that, when acted upon, protect the interests and welfare of all of the people involved” (Zygmond & Boorhem, 1989, p. 271). There are several sources of ethical principles that can be found in government and professional guidelines, the AEE/OBH accreditation standards, and research that can be applied to IYT. As identified by Clark et al. (2019); Kitchner (1984); and Priest and Gass (2020), these ethical principles can be summarized into five categories:

-

(1)

Autonomy—the right to freedom of action and choice as long as the client's behavior does not pose a serious risk to self or others.

-

(2)

Nonmaleficence—above all else, no harm is done to people.

-

(3)

Beneficence—do “the greatest good” to contribute to the health and welfare of others.

-

(4)

Fidelity—be faithful, keep promises, and be loyal and respectful of people’s rights.

-

(5)

Justice—individuals are treated equally and fairly.

In this vein, IYT may be considered an ethical option when these principles are satisfied in the IYT decision-making process. Importantly, these principles should be individualized for each client’s situation. For example, developing sensitivity, knowledge, and empathy for each youth’s background, including diagnoses, history of trauma, and culture can add contextual insight into ethical decision-making (Hoop et al., 2008).

Since the ethical dilemma is resolved in Step 4, the process does not progress to Step 5. If Step 5 was needed, the above principles would be examined through the ethical theories of balancing (Mill, 1975) and universalizability (Kant, 1964). In other words, when clinicians are unable to determine if IYT is ethical at the individual level, the final step involves justifying it at a systems level. This necessitates including others who are involved with the youth and the assurance that ethical actions will be applied consistently across all situations.

Once the ethical decision-making framework (Gass et al., 2020) has been applied, the following principles emerge as ethical guidelines for the use of IYT:

-

1.

Consent to treatment.

-

2.

Potential of harming self or others.

-

3.

Ability to make rational decisions.

-

4.

Ability of the treatment program to prevent potential harm to youth.

-

5.

Transfer only to programs demonstrating a research-based record of success for youth with their particular needs.

-

6.

Utilize programs offering the least restrictive intervention that will promote the most benefit or prevent most harm, including re-traumatization.

-

7.

Use of IYT procedures maximizing autonomy, respect, and dignity for youth throughout the entire treatment process.

Ideally, these principles are evaluated openly and transparently with consultation from other qualified professionals in order to minimize subjectivity. However, the presence of ethical guidelines alone does not help practitioners and families move forward. For this reason, a model for applying these ethical guidelines is needed in order to match procedures with the youth’s level of willingness to enter treatment throughout the IYT process. This approach involves promoting autonomy and choice, strong client-staff alliance, and trauma-informed practices.

A Model for Applying Ethical Guidelines for IYT

These practice steps for IYT can be applied sequentially by practitioners and caregivers in determining its appropriateness on a case-by-case basis, and as delineated below.

- Step 1:

-

Prior to evaluating the need for IYT, caregivers and mental health professionals need to first determine if: (a) the youth exhibits behavioral health symptoms, including a mental health or substance use disorder, severe enough to warrant treatment; (b) the referred program demonstrates an evidence-based record for youth’s particular behavioral health needs (Principle 1).

- Step 2:

-

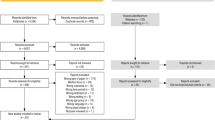

After completing Step 1, caregivers and mental health professionals would then need to determine if the youth is at imminent or severe risk of harm to self or others (Principle 2), is unwilling to consent to treatment (Principle 3), and lacks the capacity to give consent (Principle 4). As illustrated in Table 1, youth who are completely willing or reluctantly willing may be appropriate for a caregiver accompanied or supported transport option.

- Step 3:

-

After completing Step 2, Caregivers and mental health professionals would need to weigh the harm prevented versus the potential harm caused from an IYT (Principle 5) in order to balance the consequences of no treatment versus involuntary treatment via IYT. Caregivers in consultation with a licensed mental health practitioner can qualitatively contrast the consequences of each option in determining the appropriateness of an IYT. On the side of no treatment provided, the following potential consequences need to be considered:

-

(1)

Family dynamics,

-

(2)

Youth’s autonomy,

-

(3)

Harm to the youth and others, and

-

(4)

Youth’s history with transport and treatment.

For example, the risks to the youth may range from psychological distress, to incarceration, to death. The risks to others can include some combination of harm, violence, theft, and shame. By allowing the youth to avoid involuntary treatment or IYT, their independence may be maintained, but this may occur at the cost of family functioning and social, academic or employment opportunities, if problems continue and go unresolved.

Once on the side of conducting IYT, caregivers and mental health professionals need to weigh the ranges of consequences for risks to the youth and others, resurgence of past trauma, optimization of dignity, and value of treatment. For example, forcing a client into treatment may result in varying degrees of anger, self-harm, and loss of autonomy (Saya et al., 2019). This may lead to future feelings of trust, betrayal, and the desire to run away. Past trauma might resurface and unresolved trauma could possibly reinjure the youth. The dignity of the youth could be compromised by silencing their voice or disrespecting their choices. And finally, the value of the treatment program must be considered for its data-based record of past success with this kind of youth and its preparation or accreditation with the appropriate training and resources.

-

(1)

- Step 4:

-

Closely associated with the previous step, mental health professionals and caregivers need to determine that IYT is the least restrictive option that stands to promote the most benefit and reduce harm to the youth (principle 6). This can include contrasting the different forms of transport delineated in Table 1, but may also involve weighing other potential involuntary admission options, (e.g., seeking a court order).

- Step 5:

-

Once the decision for IYT has been made, it is essential to ensure that the procedures used maximize autonomy, respect, and dignity for the youth throughout the entire process (principle 7). In consultation with a mental health professional, caregivers evaluate their youth’s level of willingness along with the associated risk and transport options in Table 1. Assessment should also include a history of committing self-harm, flight/running away, aggressive/violent behavior, and unresolved pre-existing trauma.

A reported history of the first three concerns would shift the “state of willingness” to the right on Table 1. A reported history of trauma emphasizes the importance of exhausting transport options on the left of Table 1 along with incorporating trauma-informed care throughout the process. In this process staff include: licensed behavioral health clinicians, interventionists, mediators, or transporters. When a caregiver accompanies a youth, they may need to be supported by the transport staff. These staff represent a more restrictive form of IYT, yet the focus should remain on ensuring the least restrictive procedures to provide emotional and physical safety. Table 1 emphasizes the desire to complete the transport process using approaches and techniques that center on client autonomy, strong client-staff alliance, strategic and structural family systems work, and other factors that limit trauma.

Prioritizing Assessment of Client Willingness

As delineated in Table 1, the level of transport considered most ethical is the approach matching the youth's level of willingness, clinical assessment for behavioral and trauma, and risk. It is important to note that these identified states of willingness, risk levels, and transport options are intended to be flexible and dynamic to the needs of the youth. Autonomy and structure are also important factors when giving choices and hearing their concerns. An integrated approach with a dual focus on autonomy enhancement and utilizing the least restrictive procedures is recommended (Hardy, 2021).

IYT can facilitate autonomy enhancement by minimizing controlling pressures while promoting choice and an opportunity to voice concerns when choice is restricted (Ryan & Deci, 2017). A least restrictive intervention not only involves implementing procedures according to a youth’s state of willingness, but also exhausting the less restrictive techniques first, such as verbal encouragement, providing reasoning, and genuine support before utilizing a more restrictive approach (e.g., Hoge et al., 2001; O’Brien & Golding, 2003).

The following offers a narrative description for various states of client willingness and associated transport option:

-

(1)

Completely willing/caregiver accompanied Adolescents in this state on the continuum tend to agree with their caregiver in the process of attending the treatment program. Youth are both aware and cooperative with their decision about treatment, with little to no indications of hesitancy. As such, these youth are considered low risk for emotional outburst or acting out. Caregivers are the primary source of support in the transport process, though less restrictive IYT options may also be appropriate. In all transport options, the treatment program is clearly stated and an understanding by youth in terms of length of stay and process throughout the transport. In many cases, IYT staff play a nominal role in the majority of these transports.

-

(2)

Reluctant but willing/caregiver supported Adolescents in the reluctant state may or may not be aware of the consideration for a treatment program, but are skeptical of the idea and may not perceive they have a need for treatment. If aware, they may agree with the process, but require encouragement and incentive to remain willing. If unaware, they may agree with the general idea of a treatment program, but not show their understanding of the specific details of the program or the possibility of IYT. These adolescents are considered in the low-to-moderate risk for emotional outbursts or acting out. These factors often depend upon their degree of hesitancy, previous history of verbal and physical reactance, and current psychological issues. Caregivers may be a source of support during transport but often require some amount of external support from a mental health professional, trained interventionist, or IYT service. In a few cases, IYT staff play a prominent role in the majority of transport processes.

-

(3)

Resistant and unwilling/staff supported Adolescents in this state may or may not be aware of the consideration for a treatment program. They may express some form of verbal reactance toward the idea, a potential lack of motivation, and a perceived need for treatment. They may have made direct or indirect threats when a decision for treatment is made. Youth may be described as unwilling to participate in treatment and are in a moderate-to-high risk range for emotional outburst or acting out. This often depends on the severity of threats, previous history of verbal and physical reactance, and current diagnosed psychological issues. Caregivers may be involved in some aspects of the transport, but external support from a trained interventionist or IYT service is considered the primary source of support throughout the entire transport process. Caregiver involvement is generally limited to the initial time of intervention and at the time of arrival to the treatment program. In most cases, IYT staff play a significant role in the majority of transport processes.

-

(4)

Completely unwilling/secured transport Adolescents in this state explicitly disagree with the decision for treatment to the point. They may exhibit strong emotional and physical reactance (e.g., anger, acting out behavior) and actively refuse efforts by caregivers and other treatment professionals to discuss the possibility of a treatment program. They are generally not aware a decision for treatment or transport has been made. If aware, they may be at risk of running away or requiring emergency support services prior to being available for transport (e.g., admission into inpatient or temporary holding in a juvenile facility depending on the nature of their behavior). These adolescents are often emotionally and physically reactant toward treatment, at-risk to themselves or others, and at the highest range of oppositional behavior. Caregivers may be involved in some of the initial transport procedures, but only under the guidance of trained IYT staff who are capable of providing the necessary external support. Attempts are made to explain the transport options and decision for treatment, though the depth of disclosure and understanding may vary according to the youth’s ability to process this information. In all cases, IYT staff play a significant role in the majority of transport processes.

The primary focus of all four transport options is to equip professionals in providing youth with the safest, least restrictive, therapeutic experience for treatment.

Should a staff supported (level 3) or secured IYT (level 4) be deemed as the least restrictive approach, it should be noted that the use of procedures relying on threat, deceit, or brute force are contraindicated. Robbins (2014) and Mooney and Leighton (2019) identify a specific deceptive approach to IYT where youth are woken up in the middle of the night without forewarning and “strong-armed” or “kidnapped” into treatment. No evidence supporting the clinical benefit of this approach exists and its use contradicts key elements of ethical practice for IYT. While physical restraint techniques may be appropriate to maintain the safety of a physically combative or self-harming youth, the use of physical force remains unethical to the therapeutic process and thus cannot be considered a therapeutic technique. Rather, the use of any physical intervention is a safety technique that should only be utilized by trained staff who have exhausted all nonphysical crisis de-escalation techniques.

In summary, Fig. 1 represents the intersection of ethical decision making and the presentation of stepwise procedures when considering IYT. These procedures are focused on accessing client willingness, voice, and IYT being used as a last resort and least restrictive option. And when selected, IYT centers around maximizing youth autonomy, respect, and dignity.

Implications for Practice

With the ethical guidelines for IYT outlined above, it is important to discuss concrete implications for practice. Strong efforts must be made by IYT providers to include the youth, as well as their caregivers, in evaluating the use of an IYT and potential supportive or substitute procedures (e.g., family intervention, caregiver supported transport) (Persi et al., 2016). In this way, the provider can address parental and youth concerns about the transport process, as well as assess familial financial resources, in case outside support is required. At a minimum, this evaluation process should involve the practice steps presented in the Model for Applying Ethical Guidelines for IYT.

IYT providers (and other professionals such as therapists, educational consultants, etc.) should actively pursue assent by the adolescent to initiate the treatment process, even after determining that IYT is appropriate. Transport and program admission should focus on individualized client-centered, trauma-informed care. Although there are times when adolescent judgment may be diminished by impaired states (e.g., abuse of addictive substances) or other behavioral healthcare issues, staff should offer choice, provide reasoning, and opportunities to voice concerns and questions whenever possible (e.g., Ryan et al., 2015). Client autonomy should be a central focus of transport as well as treatment and needs to be relinquished to clients as soon as possible (Ryan & Deci, 2017). For example, IYT and program admission procedures should be flexible and actively seek to appropriately reduce restrictions (e.g., respectful screening procedures). Autonomy should be promoted throughout the transport process even if youth exhibit unwilling behavior.

As with all behavioral health interventions, vigilance concerning risk management and harm prevention needs to be central to all IYT procedures. Research and established risk management procedures in related fields have demonstrated their practices as safe and lower risk in comparison to other fields without research and established protocols (e.g., Javorski & Gass, 2012). For IYT to be considered a viable therapeutic technique in behavioral healthcare, transport services need to advance similar policies and practices, as well as research, to establish best practices and accountability among transport companies (e.g., Gass et al., 2020). Deceptive practices, such as waking up a youth in the night or early morning with no forewarning and physically escorting them into treatment with minimal information fundamentally contradicts the proposed ethical guidelines (Mooney & Leighton, 2019). Practices that may cause more harm than benefit to youth should be replaced by practices that not only create effective transport outcomes, but also promote client well-being and self-determination (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

To aid in the implementation of these guidelines, the field of transport services should consider a similar paradigm that was followed by the Outdoor Behavioral Healthcare (OBH) community (Gass, et al., 2020). After suffering several traumatic professional events in the 1990s, the field underwent a deep self-examination process to create the progressive field it currently experiences today. OBH organizations reflected upon and answered four critical questions concerning: (1) the examination and tracking of appropriate physical and psychological risk management, (2) the establishment of an ethical research agenda, (3) the implementation of an accreditation program, and (4) an organizational membership that resulted in the sharing of professional knowledge, and greater return on investment (Gass et al., 2020).

Future Directions

This article addresses ethical issues surrounding IYT. More scholarly investigation is required to ensure the establishment of best practices. Further research is needed on the direct impact of IYT on clients and family systems, particularly qualitative research that provides opportunities to document client voice. Research is also needed to provide empirical support for different transport options in relation to the different risks and trauma histories among youth. Best practices, accountability, and oversight that are grounded in ethical guidelines, will help to promote ongoing review of the IYT process and the development of trauma informed interventions. This focus of these efforts should be aimed at protecting and serving clients.

Work in this domain is already underway through an IYT joint task force between the Association of Mediation and Transport Services (AMATS), National Association of Therapeutic Schools and Programs (NATSAP), and the Outdoor Behavioral Healthcare Council (OBHC). Given that almost 500,000 children in the United States live in foster care placements (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2018), it is recommended to include other related professional groups (e.g., child welfare professionals, residential addiction treatment providers, other children’s residential centers) in this effort. All of these professional groups utilize involuntary treatment and serve “mandated” clients. Treatment satisfaction is often lower for involuntary clients (Martin et al., 2003), which may negatively impact treatment outcomes. For this reason, minimizing coercion through trauma-informed approaches that elevate collaboration, client voice and choice are essential.

Summary

The use of IYT in adolescent behavioral health remains a critical issue which merits ongoing investigation. If IYT is indicated, transport professionals should focus on client safety, reducing the likelihood of client re traumatization, and employing trauma-informed services. The use of IYT requires serious attention to its ethical structure in the treatment process and the use of practices that have been proven to be effective. The likelihood of IYT becoming an intentional and ethically implemented intervention that aids in the overall treatment process remains to be seen, and the responsibility falls on the shoulders of the adolescent mental health profession.

References

American Bar Association. (2007). ABA policy requiring licensure, regulation and monitoring of privately operated residential treatment facilities for at-risk children and youth. Family Court Review, 45, 414–420.

Askola, R., Nikkonen, M., Paavilainen, E., Soininen, P., Putkonen, H., & Louheranta, O. (2018). Forensic psychiatric patients’ perspectives on their care: A narrative view. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 54, 64–73.

Association of Experiential Education. (2018). Ethical guidelines for the therapeutic adventure professional. Retrieved on June 8, 2020, from https://www.aee.org/tapg-best-p-ethics

Becker, S. P. (2010). Wilderness therapy: Ethical considerations for mental health professionals. Child and Youth Care Forum, 39, 47–61.

Bettmann, J. E., Russell, K. C., & Parry, K. J. (2013). How substance abuse recovery skills, readiness to change and symptom reduction impact change processes in wilderness therapy participants. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(8), 1039–1050. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9665-2

Bolt, K. L. (2016). Descending from the summit: Aftercare planning for adolescents in wilderness therapy. Contemporary Family Therapy, 38(1), 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-016-9375-9

Briggs, E., Greeson, J., Layne, C., Fairbank, J., Knoverek, A., & Pynoos, R. (2012). Trauma exposure, psychosocial functioning, and treatment needs of youth in residential care: Preliminary findings from the NCTSN core data set. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 5(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361521.2012.646413

Chatfield, M. M., Diehl, D. C., Johns, T. L., Smith, S., & Galindo-Gonzalez, S. (2021). Quality of experience in residential care programmes: Retrospective perspectives of former youth participants. Child & Family Social Work, 26(1), 132–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12796

Clark, B. A., Preto, N., Everett, B., Young, J. M., & Virani, A. (2019). An ethical perspective on the use of secure care for youth with severe substance use. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne, 191(7), E195–E196. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.71504

Cratsley, K., & Radden, J. (2019). Public mental health ethics: An overview. In Developments in Neuroethics and Bioethics (Vol. 2, pp. 11–44). Academic Press.

Dobud, W. W. (2021). Experiences of secure transport in outdoor behavioral healthcare: A narrative inquiry. Qualitative Social Work. https://doi.org/10.1177/14733250211020088

Ellila, H. T., Sourander, A., Välimäki, M., Warne, T., & Kaivosoja, M. (2008). The involuntary treatment of adolescent psychiatric inpatients—A nation-wide survey from Finland. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 407–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.08.003

Gass, M. A. (1993). Adventure therapy: Therapeutic applications of adventure programming. Kendall Hunt.

Gass, M. A. (2018). 2018 outdoor behavioral healthcare annual marketing survey. Outdoor Behavioral Healthcare Research Center.

Gass, M., Gillis, H. L., & Russell, K. C. (2020). Adventure therapy. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327027HC1503_6

Hamilton, A. L., Jarvis, D. G., & Watts, B. (2020). Secure care: A question of capacity, autonomy, and the best interests of the child. Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de l'Association Medicale Canadienne, 192(5), E121–E122. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.73252

Hardy, C. J. (2011). Adolescent treatment coercion. Journal of Therapeutic Schools & Programs, 5, 88–95.

Hardy, C. J. (2021). Direct and indirect effects of negative pressures and voice on perceived coercion and reactance among transported adolescents [Manuscript in preparation]. College of Social Work, University of Utah.

Harper, N. J., Magnuson, D., & Dobud, W. W. (2021). A closer look at involuntary treatment and the use of transport service in outdoor behavioral healthcare (wilderness therapy). Child & Youth Services, 42(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2021.1938526

Hill, M., Glaser, K., & Harden, J. (1998). A feminist model for ethical decision making. Women in Therapy, 21(3), 101–121.

Hoge, S. K., Lidz, C., Gardner, W., Mulvey, E. P., Eisenberg, M., Monahan, J., & Roth, L. H. (2001). Executive summary. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 11, 281–293.

Hoop, J. G., DiPasquale, T., Hernandez, J. M., & Roberts, L. W. (2008). Ethics and culture in mental health care. Ethics & Behavior, 18(4), 353–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508420701713048

Javorski, S., & Gass, M. A. (2012). Accident rates/trends in Outdoor Behavioral Healthcare Industry Council (OBHIC) programs. Journal of Therapeutic Schools and Programs, 6(1), 112–128.

Jones, N., Gius, B. K., Shields, M., Collings, S., Rosen, C., & Munson, M. (2021). Investigating the impact of involuntary psychiatric hospitalization on youth and young adult trust and help-seeking in pathways to care. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02048-2

Jordan, A. E., & Meara, N. K. (1990). Ethics and the professional practices of psychologists: The role of virtues and principles. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 21(2), 7–14.

Jost, T. S. (2006). Appendix B: Constraints on sharing mental health and substance-use treatment information imposed by federal and state medical records privacy laws. In Institute of Medicine (US) committee on crossing the quality chasm: Adaptation to mental health and addictive disorders. Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions: Quality chasm series. National Academies Press (US). Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK19829/

Kant, I. (1964). Groundwork of the metaphysic of morals. Harper & Row.

Kelly, B. D. (2016). Mental health, mental illness, and human rights in India and elsewhere: What are we aiming for? Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 58(2), 168-S174. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.196822

Kennedy, D. (2020, September 30). Inside the ‘abusive’ troubled-teen industry that Paris Hilton exposed. New York Post. https://nypost.com/article/provo-canyon-school-abuse/

Kerwin, M. E., Kirby, K. C., Speziali, D., Duggan, M., Mellitz, C., Versek, B., & McNamara, A. (2015). What can parents do? A review of state laws regarding decision making for adolescent drug abuse and mental health treatment. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 24(3), 166–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/1067828X.2013.777380

Kitchener, K. S. (1984). Intuition, critical evaluation, and ethical principles: The foundation for ethical decisions in counseling psychology. The Counseling Psychologist, 12(3), 43–55.

Martin, J. S., Petr, C. G., & Kapp, S. A. (2003). Consumer satisfaction with children’s mental health services. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 20(3), 211–226.

Maylea, C. H. (2017). A rejection of involuntary treatment in mental health social work. Ethics and Social Welfare, 11(4), 336–352.

McMillan, J., Lawn, S., & Delany-Crowe, T. (2019). Trust and community treatment orders. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 349. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00349

Mercer, J. (2017). Evidence of potentially harmful psychological treatments for children and adolescents. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 34(2), 107–125.

Mill, J. S. (1975). On liberty. Penguin Classics.

Mooney, H., & Leighton, P. (2019). Troubled affluent youth’s experiences in a therapeutic boarding school: The elite arm of the youth control complex and its implications for youth justice. Critical Criminology, 27(4), 611–626.

National Association of Social Workers (NASW). (2017). NASW Code of Ethics (Guide to the Everyday Professional Conduct of Social Workers). Washington, DC: NASW.

Nyttingnes, O., Ruud, T., Norvoll, R., Rugkåsa, J., & Hanssen-Bauer, K. (2018). A cross-sectional study of experienced coercion in adolescent mental health inpatients. BMC Health Services Research, 18, 389. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3208-5

O’Brien, A., & Golding, C. (2003). Coercion in mental healthcare: The principle of least coercive care. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 10(2), 167–173. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2850.2003.00571

O’Donoghue, B., Roche, E., Shannon, S., Lyne, J., Madigan, K., & Feeney, L. (2014). Perceived coercion in voluntary hospital admission. Psychiatric Research, 215, 120–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.10.016

Opsal, A., Kristensen, O., Vederhus, J., & Clausen, T. (2016). Perceived coercion to enter treatment among involuntarily and voluntarily admitted patients with substance use disorders. BMC Health Services Research, 16, 656–666.

Pelto-Piri, V., Kjellin, L., Lindvall, C., & Engström, I. (2016). Justifications for coercive care in child and adolescent psychiatry, a content analysis of medical documentation in Sweden. BMC Health Services Research, 16(1), 1–8.

Persi, J., Bird, B. M., & DeRoche, C. (2016). A comparison of voluntary and involuntary child and adolescent inpatient psychiatry admissions. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 33(1), 69–83.

Priest, S., & Gass, M. A. (2020). Effective leadership in adventure programming. Human Kinetics.

Robbins, I. (2014). Kidnapping incorporated: The unregulated youth-transportation industry and the potential for abuse. American Criminal Law Review, 51(3), 563–600.

Rosen, K. (2021). Broken: The failed promise of America’s behavioral treatment programs. Little.

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press.

Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2015). Autonomy and autonomy disturbances in self-development and psychopathology: Research on motivation, attachment, and clinical process. In D. Chicchetti, & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Theory and method (Vol. 1, pp. 795–849). Wiley.

Safe and Sound Youth Transportation, Inc. (2020). Staff training. Retrieved from https://www.safeandsoundtransportation.com/stafftraining.html

Saya, A., Brugnoli, C., Piazzi, G., Liberato, D., Di Ciaccia, G., Niolu, C., & Siracusano, A. (2019). Criteria, procedures, and future prospects of involuntary treatment in psychiatry around the world: A narrative review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 271. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.0027

Seo, M. K., Kim, S. H., & Rhee, M. (2013). The impact of coercion on treatment outcome: One-year follow-up survey. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 45, 279–298. https://doi.org/10.2190/PM.45.3.g

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Szalavitz, M. (2006). Help at any cost. Penguin Group.

Tucker, A., Bettmann, J., Norton, C. L., & Comart, C. (2015). The role of transport use in adolescent wilderness treatment: Its relationship to readiness to change and outcome. Child and Youth Care Forum, 44, 671–686. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-015-9301-6

Tucker, A., Combs, K. M., Bettman, J., Chang, T., Graham, S., Hoag, M., & Tatum, C. (2018). Longitudinal outcomes for youth transported to wilderness therapy programs. Research on Social Work Practice, 29(4), 438–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731516647486

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children, Youth and Families. (2018). The AFCARS report. Retrieved from www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2008). Residential programs: Selected cases of death, abuse, and deceptive marketing. Retrieved from http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d08713t.pdf

Winick, B. J. (2008). A therapeutic jurisprudence approach to dealing with coercion in the mental health system. Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law, 15, 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218710801979084

Zigmond, T. (2017). Mental health law across the UK. BJPsych Bulletin, 41(6), 305–307. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.117.056622

Zygmond, M. J., & Boorhem, H. (1989). Ethical decision making in family therapy. Family Process, 28, 269–280.

Funding

There was no funding provided to any of the authors for this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The lead author and the third author are both research scientists with the Outdoor Behavioral Healthcare Center and work closely with the Outdoor Behavioral Healthcare Council (OBHC) and the National Association of Therapeutic Schools and Programs (NATSAP). They co-chair the OBHC/NATSAP Transport Task Force. The second author is the former owner of a youth transport company. None of the authors were financially compensated for their work.

Ethical Approval

This is a theoretical paper, and there were no human or animal subjects involved in research; therefore, IRB approval was not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gass, M., Hardy, C., Norton, C. et al. Involuntary Youth Transport (IYT) to Treatment Programs: Best Practices, Research, Ethics, and Future Directions. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 39, 291–302 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-021-00801-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-021-00801-9