Abstract

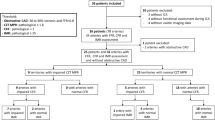

Women with angina and no obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) have worse cardiovascular prognosis than asymptomatic women. Limitation in myocardial perfusion caused by coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) is one of the proposed mechanisms contributing to the adverse prognosis. The aim of this study was to assess myocardial perfusion in symptomatic women with no obstructive CAD suspected for CMD compared with asymptomatic sex-matched controls using static CT perfusion (CTP). We performed a semi-quantitative assessment of the left ventricular myocardial perfusion and myocardial perfusion reserve (MPR), using static CTP with adenosine provocation, in 105 female patients with angina and no obstructive CAD (< 50% stenosis) and 33 sex-matched controls without a history of angina or ischemic heart disease. Patients were on average 4 years older (p = 0.04) and had a higher burden of cardiovascular risk factors. While global perfusion during rest was comparable between the groups (age-adjusted p = 0.12), global perfusion during hyperemia was significantly reduced in patients compared with controls (163 ± 23 HU vs. 171 ± 25 HU; age-adjusted p = 0.023). The ability to increase myocardial perfusion during adenosine-induced vasodilation was significantly diminished in patients (MPR 148% vs. 158%; age-adjusted p < 0.001). This remained unchanged after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors (p = 0.008). Women with angina and no obstructive CAD have reduced hyperemic myocardial perfusion and MPR compared with sex-matched controls. Impaired myocardial perfusion may be related to the presence of CMD in some of these women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Attenuation density

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CAC:

-

Coronary artery calcium

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- CCTA:

-

Coronary computed tomography angiography

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- CMD:

-

Coronary microvascular dysfunction

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CTP:

-

CT perfusion

- DFB:

-

Daria Frestad Bechsgaard

- HU:

-

Hounsfield units

- IHD:

-

Ischemic heart disease

- JJL:

-

Jesper James Linde

- MPR:

-

Myocardial perfusion reserve

- LAD:

-

Left anterior descending coronary artery

- LV:

-

Left ventricle

- LCX:

-

Left circumflex coronary artery

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- RCA:

-

Right coronary artery

- TPR:

-

Transmural perfusion ratio

References

Patel MR, Peterson ED, Dai D et al (2010) Low diagnostic yield of elective coronary angiography. N Engl J Med 362:886–895. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0907272

Bairey Merz CN, Shaw LJ, Reis SE et al (2006) Insights from the NHLBI-Sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Study: part II: gender differences in presentation, diagnosis, and outcome with regard to gender-based pathophysiology of atherosclerosis and macrovascular and microvascular cor. J Am Coll Cardiol 47:S21–S29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.084

Sharaf B, Wood T, Shaw L et al (2013) Adverse outcomes among women presenting with signs and symptoms of ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease: findings from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) angiographic core lab. Am Heart J 166:134–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2013.04.002

Jespersen L, Abildstrom SZ, Hvelplund A et al (2014) Burden of hospital admission and repeat angiography in angina pectoris patients with and without coronary artery disease: a registry-based cohort study. PLoS ONE 9:e93170. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0093170

Gulati M, Shaw LJ, Bairey Merz CN (2012) Myocardial ischemia in women: lessons from the NHLBI WISE study. Clin Cardiol 35:141–148. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.21966

Chen C, Wei J, AlBadri A et al (2017) Coronary microvascular dysfunction - epidemiology, pathogenesis, prognosis, diagnosis, risk factors and therapy. Circ J 81:3–11. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-16-1002

Brainin P, Frestad D, Prescott E (2018) The prognostic value of coronary endothelial and microvascular dysfunction in subjects with normal or non-obstructive coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 254:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.10.052

Michelsen MM, Mygind ND, Frestad D, Prescott E (2017) Women with stable angina pectoris and no obstructive coronary artery disease: closer to a diagnosis. Eur Cardiol Rev 12:14–19. https://doi.org/10.15420/ecr.2016:33:2

Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A et al (2019) 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz425

Bechsgaard DF, Gustafsson I, Linde JJ et al (2019) Myocardial perfusion assessed with cardiac computed tomography in women without coronary heart disease. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 39:65–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpf.12542

Mygind ND, Michelsen MM, Pena A et al (2016) Coronary microvascular function and cardiovascular risk factors in women with angina pectoris and no obstructive coronary artery disease: the iPOWER study. J Am Heart Assoc 5:e003064. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.115.003064

Aguib Y, Al Suwaidi J (2015) The copenhagen city heart study (Østerbroundersøgelsen). Glob Cardiol Sci Pract 2015:33. https://doi.org/10.5339/gcsp.2015.33

Michelsen MM, Mygind ND, Pena A et al (2017) Transthoracic Doppler echocardiography compared with positron emission tomography for assessment of coronary microvascular dysfunction: the iPOWER study. Int J Cardiol 228:435–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.11.004

Tobias Kühl J, Linde JJ, Fuchs A et al (2012) Patterns of myocardial perfusion in humans evaluated with contrast-enhanced 320 multidetector computed tomography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 28:1739–1747. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-011-9986-z

Bischoff B, Bamberg F, Marcus R et al (2013) Optimal timing for first-pass stress CT myocardial perfusion imaging. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 29:435–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-012-0080-y

Kim M, Lee JM, Yoon JH et al (2014) Adaptive iterative dose reduction algorithm in CT: effect on image quality compared with filtered back projection in body phantoms of different sizes. Korean J Radiol 15:195–204. https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2014.15.2.195

Trattner S, Halliburton S, Thompson CM et al (2018) Cardiac-specific conversion factors to estimate radiation effective dose from dose-length product in computed tomography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 11:64–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.06.006

Wu F-Z, Wu M-T (2015) 2014 SCCT guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of coronary CT angiography: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 9:e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcct.2015.01.003

Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V et al (2002) Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart. A statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 18:539–542

Danad I, Uusitalo V, Kero T et al (2014) Quantitative assessment of myocardial perfusion in the detection of significant coronary artery disease: cutoff values and diagnostic accuracy of quantitative [(15)O]H2O PET imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol 64:1464–1475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.069

Chareonthaitawee P, Kaufmann PA, Rimoldi O, Camici PG (2001) Heterogeneity of resting and hyperemic myocardial blood flow in healthy humans. Cardiovasc Res 50:151–161

Czernin J, Müller P, Chan S et al (1993) Influence of age and hemodynamics on myocardial blood flow and flow reserve. Circulation 88:62–69. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.88.1.62

Kaufmann PA, Namdar M, Matthew F et al (2005) Novel doppler assessment of intracoronary volumetric flow reserve: validation against PET in patients with or without flow-dependent vasodilation. J Nucl Med 46:1272–1277

Geltman EM, Henes CG, Senneff MJ et al (1990) Increased myocardial perfusion at rest and diminished perfusion reserve in patients with angina and angiographically normal coronary arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol 16:586–595

Scholtens AM, Tio RA, Willemsen A et al (2011) Myocardial perfusion reserve compared with peripheral perfusion reserve: a [13 N]ammonia PET study. J Nucl Cardiol 18:238–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12350-011-9339-2

Graf S, Khorsand A, Gwechenberger M et al (2007) Typical chest pain and normal coronary angiogram: cardiac risk factor analysis versus PET for detection of microvascular disease. J Nucl Med 48:175–181

Kaufmann PA, Camici PG (2005) Myocardial blood flow measurement by PET: technical aspects and clinical applications. J Nucl Med 46:75–88

Panting JR, Gatehouse PD, Yang G-Z et al (2002) Abnormal subendocardial perfusion in cardiac syndrome X detected by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. N Engl J Med 346:1948–1953. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa012369

Thomson LEJ, Wei J, Agarwal M et al (2015) Cardiac magnetic resonance myocardial perfusion reserve index is reduced in women with coronary microvascular dysfunction: a national heart, lung, and blood institute-sponsored study from the women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 8:e002481. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.114.002481

Shufelt CL, Thomson LEJ, Goykhman P et al (2013) Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging myocardial perfusion reserve index assessment in women with microvascular coronary dysfunction and reference controls. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 3:153–160. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2013.08.02

Reis SE, Holubkov R, Lee JS et al (1999) Coronary flow velocity response to adenosine characterizes coronary microvascular function in women with chest pain and no obstructive coronary disease. Results from the pilot phase of the Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 33:1469–1475

Chauhan A, Mullins PA, Taylor G et al (1997) Both endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent function is impaired in patients with angina pectoris and normal coronary angiograms. Eur Heart J 18:60–68

Linde JJ, Kühl JT, Hove JD et al (2015) Transmural myocardial perfusion gradients in relation to coronary artery stenoses severity assessed by cardiac multidetector computed tomography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 31:171–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-014-0530-9

Algranati D, Kassab GS, Lanir Y (2011) Why is the subendocardium more vulnerable to ischemia? A new paradigm. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300:H1090–H1100. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00473.2010

Driessen RS, Stuijfzand WJ, Raijmakers PG et al (2018) Effect of plaque burden and morphology on myocardial blood flow and fractional flow reserve. J Am Coll Cardiol 71:499–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.054

Imai S, Kondo T, Stone GW et al (2019) Abnormal fractional flow reserve in nonobstructive coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 12:e006961. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.118.006961

Marini C, Seitun S, Zawaideh C et al (2017) Comparison of coronary flow reserve estimated by dynamic radionuclide SPECT and multi-detector x-ray CT. J Nucl Cardiol 24:1712–1721. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12350-016-0492-5

De Bruyne B, Hersbach F, Pijls NHJ et al (2001) Abnormal epicardial coronary resistance in patients with diffuse atherosclerosis but “normal” coronary angiography. Circulation 104:2401–2406. https://doi.org/10.1161/hc4501.099316

Kühl JT, George RT, Mehra VC et al (2016) Endocardial-epicardial distribution of myocardial perfusion reserve assessed by multidetector computed tomography in symptomatic patients without significant coronary artery disease: insights from the CORE320 multicentre study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 17:779–787. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jev206

Sara JD, Widmer RJ, Matsuzawa Y et al (2015) Prevalence of coronary microvascular dysfunction among patients with chest pain and nonobstructive coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 8:1445–1453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2015.06.017

Murthy VL, Naya M, Taqueti VR et al (2014) Effects of sex on coronary microvascular dysfunction and cardiac outcomes. Circulation 129:2518–2527. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008507

Rossi A, Merkus D, Klotz E et al (2014) Stress myocardial perfusion: imaging with multidetector CT. Radiology 270:25–46. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.13112739

Case JA, deKemp RA, Slomka PJ et al (2017) Status of cardiovascular PET radiation exposure and strategies for reduction: an information statement from the cardiovascular PET task force. J Nucl Cardiol 24:1427–1439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12350-017-0897-9

Al Jaroudi W, Iskandrian AE (2009) Regadenoson: a new myocardial stress agent. J Am Coll Cardiol 54:1123–1130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.089

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Danish Heart, Arvid Nilssons Foundation and Hvidovre Hospital Research Council. The Authors would like to thank the Copenhagen City Heart study, Departments of Cardiology and Radiology, Hvidovre University Hospital, and Department of Cardiology, Bispebjerg University Hospital, for their collaboration on this project. We thank chief radiologist Dennis Møller and radiologists Tina Berland Larsen, Anja Nielsen, Linn Haraldseid, and the nursing head of the outpatient department of Cardiology Sussie Foghmar for their assistance in data acquisition. Lastly, we want to express our deepest gratitude to the women participating in the iPOWER study for their time and willingness to contribute to the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declared that they no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bechsgaard, D.F., Gustafsson, I., Michelsen, M.M. et al. Evaluation of computed tomography myocardial perfusion in women with angina and no obstructive coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 36, 367–382 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-019-01723-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-019-01723-5