Abstract

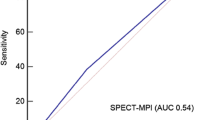

Computed tomography derived fractional flow reserve (FFRCT) and computed tomography stress myocardial perfusion imaging (CTP) are techniques to assess haemodynamic significance of coronary stenosis. To compare the diagnostic performance of FFRCT and static rest/stress CTP in detecting fractional flow reserve (FFR) defined haemodynamically-significant stenosis (FFR ≤ 0.8). Fifty-one patients (96 vessels) with suspected coronary artery disease from a single institution planned for elective invasive-angiography prospectively underwent research indicated 320-detector-CT-coronary-angiography (CTA) and adenosine-stress CTP and invasive FFR. Analyses were performed in separate core-laboratories for FFRCT and CTP blinded to FFR results. Myocardial perfusion was assessed visually and semi-quantitatively by transmural perfusion ratio (TPR). Invasive FFR ≤ 0.8 was present in 33% of vessels and 49% of patients. FFRCT, visual CTP and TPR analysis was feasible in 96%, 92% and 92% of patients respectively. Overall per-vessel sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic accuracy for FFRCT were 81%, 85%, 84%, for visual CTP were 50%, 89%, 75% and for TPR were 69%, 48%, 56% respectively. Receiver-operating-characteristics curve analysis demonstrated larger per vessel area-under-curve (AUC) for FFRCT (0.89) compared with visual CTP (0.70; p < 0.001), TPR (0.58; p < 0.001) and CTA (0.70; p = 0.0007); AUC for CTA + FFRCT (0.91) was higher than CTA + visual CTP (0.77, p = 0.008) and CTA + TPR (0.74, p < 0.001). Per-patient AUC for FFRCT (0.90) was higher than visual CTP (0.69; p = 0.0016), TPR (0.56; p < 0.0001) and CTA (0.68; p = 0.001). Based on this selected cohort of patients FFRCT is superior to visually and semi-quantitatively assessed static rest/stress CTP in detecting haemodynamically-significant coronary stenosis as determined on invasive FFR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ischemia assessment remains the cornerstone management of stable coronary artery disease (CAD), as its presence and burden predicts benefit from revascularization [1, 2]. While CT coronary angiography (CTA) in its current form cannot reliably predict lesion specific ischemia, novel techniques such as CT stress myocardial perfusion imaging (CTP) and non-invasive CT-derived fractional flow reserve have been demonstrated to accurately predict lesion specific ischemia as determined by invasive fractional flow reserve (FFR) [3, 4]. These techniques differ widely in physiological principles, acquisition requirements, image processing and result interpretation.

Ischemia detection in CTP requires two scans which are performed during rest and vasodilator stress. When significant ischemia is present, the lack of blood flow during vasodilator stress results in lower contrast attenuation in the distal subtended myocardium, which can be determined using static or dynamic acquisition. In static CTP, perfusion defects are typically detected visually or semi-quantitatively using the transmural perfusion ratio (TPR). In dynamic CTP, perfusion can be quantified using mathematical algorithms [5].

FFRCT is defined as the ratio of the CT-derived distal coronary and aortic pressure [6]. Pressure can be derived by computational fluid modeling applied on standard CT angiogram datasets with no need of additional medication, contrast or radiation. The fluid modeling is performed centrally using a supercomputer in a remote location with the test result available within 4–24 h.

The techniques of CTP and FFRCT are used in selected centres in the United States. The aim of this paper is to compare the diagnostic performance of static CTP and FFRCT to detect lesion specific ischemia, using the established outcome-based reference standard of invasive FFR [7].

Methods

Symptomatic patients with no known CAD who were at intermediate or high risk and were scheduled for clinically mandated invasive coronary angiography were prospectively screened and enrolled from a single institution. Patients were excluded for age < 40 years, advanced atrioventricular block, atrial fibrillation, recent myocardial infarction, severe left main disease, renal insufficiency (estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 ml min/1.73 m2), bronchospastic lung disease requiring long term steroid therapy and contraindications to iodinated contrast or adenosine. All enrolled patients underwent research indicated 320-detector CTA, stress static CTP and invasive FFR, which was undertaken in at least 1 major epicardial vessel with > 2 mm diameter, with a visually assessed stenosis between 10 and 90% during invasive angiography. The study was approved by the institutional human research ethics committee and all participants provided written informed consent.

CT imaging protocol

Cardiac CT assessment was performed using a 320-row detector CT scanner (Aquilion One Vision; Canon Medical Systems Corp, Otawara, Japan). The scan protocol consists of a calcium score scan, a rest CTA followed by a stress CTP 20 min later [8]. Patients were requested to refrain from caffeine 8 h prior to the scan. Prior to the rest CTA, patients received sublingual nitoglycerin (400 mcg) and beta-blockers were administered to achieve a pre-CTA scan heart rate of 60 beats per minute. Intravenous adenosine (140 mcg/kg/min) was administered for 3 min prior to stress CTP scan acquisition. Scan parameters were: detector collimation 320 × 0.5 mm; tube current 300–500 mA (depending on body mass index); tube voltage 120 kV if BMI ≥ 25 (100 kV if BMI < 25); temporal resolution of 135 ms and 75 mls of contrast were used in both rest CTA and stress CTP. Prospective ECG gated CT scans were performed at rest and during vasodilator stress targeting 70–99% of the R–R interval. In event of heart rates > 70 bpm during stress CTP, a wider window of acquisition between 30 and 99% was performed. CTA and CTP were triggered in the arterial phase at the predicted peak of contrast bolus for myocardial enhancement [9].

CTA analysis

The rest CTA analysis was performed in a core CTA laboratory (The Heart Centre, Rigshospitalet, Denmark) by two interpreters (JL, MS) who were blinded to which vessels were interrogated with invasive FFR, and the results of FFR and ICA. All coronary segments ≥ 2 mm were visually analysed and scored for degree of luminal stenosis on a dedicated workstation (Vitrea Fx, 6.4, Vital Images, USA) in accordance to the 18 segment coronary model [10]. A vessel was considered significantly stenotic if there was ≥ 1 segment which was non-evaluable or with a ≥ 50% luminal narrowing.

CTP analysis

Assessment of stress CTP was performed using both rest and stress images in a core laboratory (The Heart Centre, Rigshospitalet, Denmark) by two experienced interpreters (JL 8 years, MS 5 years) who were blinded to which vessels were interrogated with invasive FFR, and the results of FFR and ICA with disagreement resolved by consensus.

The images were reconstructed at 3% phase intervals to facilitate CTP interpretation using FC03 reconstruction kernel [8]. The phase with the least cardiac motion was selected, and images were interpreted using a narrow window width and level setting (W300/L150), and an averaged multiplanar reconstruction slice thickness of 3 to 5 mm.

First each of the 17 myocardial segments, according to the American Heart Association myocardial segment model [11], was matched to a major epicardial vessel, and visually assessed on rest and stress static CTP for the absence or presence of a reversible perfusion defect. A vessel was considered significant if a reversible perfusion defect was present in ≥ 1 of its matched myocardial segments. When artifacts were present in > 50% of the vessel-subtended myocardial segments, the vessel was deemed uninterpretable. Reader confidence was recorded for interpretation. Reader confidence of each vessel territory was scored on a scale of 1 to 5, 1 = very uncertain, 2 = uncertain, 3 = fair, 4 = good, 5 = excellent.

For the quantitative assessment, the transmural perfusion ratio was scored for each myocardial segment using custom analysis software (Vitrea Fx 6.4, Vital Images) using the same phase of images chosen for visual analysis. An automated border detection algorithm was applied to define the subendocardial and subepicardial borders after manual adjustments to the left ventricular axis and myocardial contouring. The myocardium is divided into three myocardial layers—the subendocardium, mid myocardium and subepicardial layers, and the attenuation density in each layer was calculated. Transmural perfusion ratio is calculated as the ratio of the segment specific subendocardial attenuation density to the mean attenuation density of the entire subepicardial layer of any given short axis slice. The segment with the lowest transmural perfusion ratio value was chosen to represent perfusion for each major vessel.

FFRCT analysis

The CTA dataset was sent for FFRCT analysis at HeartFlow Inc., Redwood City, USA. FFRCT analysis was completed using the most recent generation of FFRCT analysis software. First, a CT-derived luminal model of the coronary tree is constructed, second, physiological assumptions are applied to predict coronary inlet and outlet flow, pressure and microvascular resistance during maximal hyperemia [6]. Finally a numerical solution provided by a parallel supercomputer onto a three dimensional CT-derived mesh model is used to compute coronary pressures hence FFRCT along the coronary tree. A luminal model of FFRCT in the entire coronary tree is generated. The FFRCT value for each vessel is taken as that occurring at the corresponding position of the pressure wire sensor recorded during invasive FFR measurement. A vessel with FFRCT ≤ 0.8 was considered significant.

Invasive coronary angiography and FFR

Invasive FFR was performed in the distal coronary artery as per standard practice after administration of intracoronary nitroglycerin (100mcg). It was performed in at least 1 vessel segment with diameter ≥ 2 mm with visual stenosis between 10 and 90%. Decisions regarding which vessel was interrogated with invasive FFR was at the discretion of the interventionist, who were blinded to the CT findings. The FFR value was recorded during steady state after administration of intravenous adenosine at 140 mcg/kg/min. Pullback of the pressure sensor back into the tip of the guiding catheter was performed, and only vessels with recording of a signal drift in FFR of < 0.05 were included. An FFR value of ≤ 0.8 was chosen to define hemodynamically significant stenosis.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was per vessel diagnostic performance as assessed by the area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC) of FFRCT, visually assessed CTP and TPR using invasive FFR ≤ 0.8 as reference standard to define hemodynamically significant stenosis. Secondary endpoints included (1) per vessel and per patient diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV), (2) combined per vessel CTA + visual CTP, CTA + TPR and CTA + FFRCT as assessed by AUC and (3) per patient diagnostic performance as assessed by AUC. Primary and secondary analyses was performed on all interpretable vessels for each technique, after excluding uninterpretable vessels.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD if normally distributed whereas categorical variables are expressed as percentage. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare the median FFR values. The correlation between FFRCT and invasive FFR values was determined with a Pearson Correlation coefficient. The AUC comparisons were performed on per vessel and per patient level according to the method described by DeLong et al. [12], treating FFRCT and TPR as continuous variables and visual CTP as dichotomous variable. Patient identity was included as a cluster variable to account for multiple arteries taken from individuals. The optimal TPR threshold (0.94) for detecting FFR defined hemodynamically significant stenosis was determined using the Youden Index [13]. The incremental diagnostic value of adding FFRCT, CTP or TPR to CTA was assessed by AUC using a binary logistic regression model. Inter-observer variability was assessed for FFRCT, TPR, CTP treated as dichotomized variables using kappa statistics on 15 randomly selected patients including 30 vessel territories. Additional Bland Altman plot analysis was performed for FFRCT and TPR to evaluate inter-observer reproducibility. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 24. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

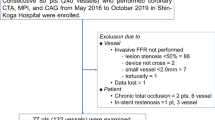

Patient enrollment flow chart is illustrated in Fig. 1. Among the 56 patients who underwent CTA, CTP and invasive FFR, 5 patients were excluded due to truncated image [1], interatrial RCA (n = 1), interval revascularization (n = 1), and pressure wire position not recorded (n = 2). Of the remaining 51 patients (including 96 FFR-interrogated vessels) deemed eligible for analysis, mean age was 61.9 ± 9.8 years and 76.5% were male. Patient and vessel characteristics and CT scan parameters are summarized in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

FFR ≤ 0.8 was present 25 patients (49%) including 32 vessels (33%). Among the patients and vessels eligible for analysis, FFRCT was interpretable in 49 patients (96%) including 91 vessels (91%). FFRCT analysis could not be performed in 2 patients secondary to poor CT image quality. In the first case, there was excessive blooming artefact secondary to vessel calcification and in the second case, there was vessel motion artefact. CTP was interpretable in 47 patients (92%) including 88 vessels (92%). The presence of significant motion artefacts precluded analysis in 4 patients. Mean reader confidence score was 4.2 ± 0.9. The number and percentage of vessels interpreted with reader confidence scores of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 were 0 (0%), 4 (4.5%), 16 (18.2%), 26 (29.5%), 42 (47.7%) respectively.

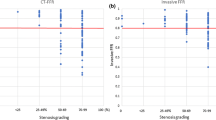

The distribution of FFRCT and FFR is displayed in Supplementary Figure. The box plot of visual CTP, TPR and FFRCT versus invasive FFR is displayed in Fig. 2. The per-patient and vessel diagnostic performance of coronary CTA, CTP, TPR, FFRCT is summarized in Table 4. The per vessel CTA + visual CTP, CTA + TPR and CTA + FFRCT is illustrated in Fig. 3. An example is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Box plot correlation with FFR. a The median FFR in vessels with FFRCT ≤ 0.8 was significantly lower than in vessels with FFRCT > 0.8 (p < 0.0001). b Similarly, the median FFR in vessels with visually assessed perfusion defect on CTP was significantly lower than in vessels with normal perfusion (p < 0.0001). c The median FFR in vessels with significant TPR was not significantly lower than in vessels with normal TPR (p = 0.08)

Per vessel and patient diagnostic performance. a Per vessel AUC for FFRCT was significantly higher than visual CTP (p < 0.0001), TPR (p < 0.0001) and CTA (p = 0.0007). b Per patient AUC for FFRCT was significantly higher than CTP (p = 0.0016), TPR (p < 0.001) and CTA (p = 0.0011). c CTA + FFRCT had the highest AUC which was significantly higher than CTA alone (p = 0.0001), CTA + visual CTP (p = 0.0082) and CTA + TPR (p = 0.0009). The AUC for CTA + visual CTP was significantly higher than CTA alone (p = 0.02). The AUC for CTA + TPR was not significantly different from CTA alone (p = 0.26)

Case example. A 70 year old man with class II angina was identified to have severe mid LAD stenosis on CTA and invasive angiography with invasive FFR of 0.65. FFR was not performed in the remaining arteries which had no significant stenosis. The FFRCT in LAD was 0.77. Perfusion defects were identified visually in the axial images of the myocardium corresponding to the mid anterior and septal segments. The TPR was significant in the basal and distal anterior septum (0.90)

Per vessel diagnostic performance

The primary endpoint of per-vessel AUC for FFRCT was 0.89, which was significantly higher than visual CTP (0.70), TPR (0.58) and CTA (0.70) (Fig. 3).

FFRCT had the highest per vessel sensitivity of 80.6% and specificity 85.0%. FFRCT reduced the number of false positive vessels by 63% when compared with CTA. While CTP had high per vessel specificity of 89.3%, the sensitivity was 50.0%. TPR had low sensitivity 68.8% and specificity 48.2%.

The AUC of CTA + FFRCT was 0.91, which was significantly higher than CTA alone (0.70), CTA + visual CTP (0.77) and CTA + TPR (0.74). The AUC for CTA + visual CTP was significantly higher than CTA alone. The AUC for CTA + TPR was not significantly different from CTA alone.

In vessels with CTA > 50%, the AUC for FFRCT was 0.82, which was significantly higher than CTP (0.64, p = 0.025) and TPR (0.51, p = 0.0018). The sensitivity and specificity in this cohort was 79.2% and 72.7% for FFRCT. The corresponding numbers for CTP and TPR were 56.0%, 71.4% and 60.0%, 52.4% respectively.

The median per vessel calcium score was 81. In vessels with a calcium score < 81, the diagnostic accuracy of FFRCT was 80.0%. The corresponding values for CTP and TPR was 80.5% and 51.2%. In vessels with a calcium score > 81, the diagnostic accuracy of FFRCT was 89.4%, which was higher than CTP (64.1%) and TPR (48.7%).

Per patient diagnostic performance

Per patient AUC for FFRCT was 0.90 which was significantly higher than CTP 0.69, TPR 0.56 and CTA 0.68. Per patient accuracy of FFRCT was 83.7% with a sensitivity of 83.3%, specificity 84.0%. Both CTP and TPR had a lower overall accuracy 68.1% and 53.2%, sensitivity 60.0% and 68.0% and lower specificity 77.3% and 40.9% respectively.

Of the 36 patients with at least one significant CTA stenosis, FFRCT was negative in 14 patients (11/14 were truly negative on FFR, 3/14 were falsely negative—mean FFR was 0.75, range 0.68–0.80). The CTP was normal in 15 patients (7/15 were truly negative, 8/15 were falsely negative—mean FFR 0.72, range 0.53–0.80), and TPR was normal in 14 patients (6/14 were truly negative, 8/14 were falsely negative—mean FFR 0.74, range 0.65–0.80).

Reproducibility

In 15 randomly selected patients, including 30 vessels, per vessel intra-observer variability of FFRCT, visual CTP and TPR was modest (k = 0.49, p < 0.01, k = 0.44, p = 0.02 and k = 0.68, p < 0.001 respectively). Bland Altman analysis of FFRCT demonstrated a non-significant mean inter-observer difference of 0.01 (p = 0.12) with standard deviation of 0.039 and 95% limits of agreement of − 0.065 to 0.088. Bland–Altman analysis for TPR demonstrated a mean inter-observer difference of − 0.017 (p = 0.18, 95% limits of agreement: − 0.14 to 0.10).

Discussion

This study compared the diagnostic performance of static CTP and FFRCT to detect hemodynamically significant stenosis. Both techniques are increasingly used in clinical practice. In this cohort FFRCT is superior to both visual CTP and TPR in diagnostic performance on both per vessel and patient basis. While both visual CTP and FFRCT improved the diagnostic performance of CTA when combined, the improvement was higher when combined with FFRCT compared with CTP. There was no improvement in diagnostic performance of CTA when combined with TPR. Performance of CTP in addition to CTA required use of adenosine, and additional radiation (5.7 mSv on average) and contrast (75 mls).

A recent metanalysis reported the per vessel sensitivity and specificity of static CTP was between 72–82% and 83–88% respectively [14]. However the studies used have not devised a core-laboratory for CTP assessment. Based on this current core-laboratory adjudicated study, the per vessel sensitivity is lower than previously reported at 50%, while the specificity of 89% is within reported range.

A number of studies have compared the diagnostic performance of static and dynamic CTP with point of care CT-FFR using invasive FFR as reference standard [15,16,17]. Yang et al. demonstrated the AUC of point of care CT-FFR and static CTP acquired using second generation dual source CT were comparably high (0.89 for both) [16]. The sensitivity of static CTP was 79%, specificity was 91%. Coenen et al. in a cohort of 74 patients scanned using second and third generation dual source CT demonstrated comparable AUC of dynamic stress CTP and point of care CT-FFR (AUC = 0.78 for both techniques) [15]. Using an indexed myocardial blood flow threshold, the sensitivity of CTP was 73%, specificity was 68%. Lastly Ihdayhid et al. reported static visual CTP acquired using 320 detector CT had a per vessel sensitivity of 54%. Visual CTP had lower AUC when compared with onsite CT-FFR (0.89 vs. 0.72 p = 0.02) [17]. These results indicate that the diagnostic performance of CTP may potentially vary depending on the scanner used; and whether static or dynamic perfusion assessment is used.

The lower than predicted sensitivity for invasive FFR < 0.8 has been widely reported in stress perfusion techniques [18]. Bettencourt et al. reported per vessel and per patient sensitivity of 55% and 68% respectively in CTP [4]. According to data from meta-analysis and prospective multi-modality comparative trials the per vessel sensitivity of single photon emission computed tomography myocardial perfusion imaging (SPECT MPI) for FFR ≤ 0.8, was found to be between 36 and 57% [18,19,20,21] Similarly in the recent Dan-NICAD cohort, magnetic resonance perfusion imaging was found to have a per sensitivity of 41% [21].

This suggests inherent methodological differences in perfusion assessment and FFRCT. CTP assesses for the presence of myocardial ischemia which may result from the presence of a significant epicardial stenosis, microvascular dysfunction or both—which may be better accounted by coronary flow reserve (CFR). FFRCT, similar to invasive FFR, assesses lesion specific ischemia which results from the presence of a significant epicardial stenosis alone. The use of invasive FFR as the reference standard may hence favour the diagnostic performance of FFRCT. Discrepancies between FFR and CFR or myocardial flow as assessed by PET have been described [22, 23]. Accordingly in subjects with an abnormal FFR yet preserved CFR, stress CTP may be normal, despite the presence of a FFR significant stenosis.

There are a number of strengths in this study. First core lab analysis for both CTP and FFRCT was performed blinded to invasive FFR. Notably in similar comparison studies, core lab adjudicated CTP assessment has not been used. Second the study is investigator initiated without support from industry or CT vendor, hence reducing potential bias. Third, static CTP has been assessed using both visual and semi-quantitative methods. Lastly the FFRCT location was matched exactly with the pressure sensor location at time of invasive FFR measurement. The values for FFRCT and invasive FFR changes along the length of coronary artery [24], and meticulous matching assists in discerning true correlation.

There are limitations in this study. (1) This study included limited number of patients enrolled from a single institution. (2) The study cohort included patients referred for clinically mandated elective ICA, and the invasive FFR and CTA/CTP had been performed for research purpose alone. Notably invasive FFR was not performed in all vessels, but at discretion of the interventionist. For this reason, the results may not be generalised to lower risk cohorts with suspected CAD referred for clinically mandated coronary CTA. (3) Our results compared static CTP acquired using 320 detector single source CT with FFRCT. These results cannot be conferred to other CTP techniques including dynamic perfusion, dual energy CTP, or CTP performed using other scanner technology including dual source CT. (4) The study only included patients with suspected disease and excluded patients with stenting. Diagnostic performance in these patients, in whom CTP may confer a potential advantage is unknown [25]. (5) Beta blockers and sublingual GTN were administered prior to rest CTA, as had been previously described. These may influence the accuracy of the stress CTP.

Conclusion

Based on the results of this core lab adjudicated single institution cohort with 320-detector CTA, CTP and invasive FFR, FFRCT demonstrated superior diagnostic performance when compared with visual and semi-quantitatively assessed static CTP for detection of hemodynamically significant stenosis as assessed on invasive FFR on both per vessel and patient basis. While both visual CTP and FFRCT improved the diagnostic performance of CTA when combined, the improvement was higher when combined with FFRCT compared with visual CTP. Semiquantitative TPR perfusion assessment did not improve the diagnostic performance of CTA. Future prospective multicenter core laboratory adjudicated trials may assist in validating these results.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CTA:

-

Computed tomography coronary angiography

- FFRCT :

-

Non-invasive CT-derived fractional flow reserve

- ICA:

-

Invasive coronary angiography

- FFR:

-

Fractional flow reserve

- CFD:

-

Computational fluid dynamics

- ROC:

-

Receiver-operating characteristics curve

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

References

De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, Kalesan B et al (2012) Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI versus medical therapy in stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med 367:991–1001

Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Shaw LJ et al (1998) Incremental prognostic value of myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography for the prediction of cardiac death: differential stratification for risk of cardiac death and myocardial infarction. Circulation 97:535–543

Norgaard BL, Leipsic J, Gaur S et al (2014) Diagnostic performance of non-invasive fractional flow reserve derived from coronary CT angiography in suspected coronary artery disease: the NXT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 63:1145–1155

Bettencourt N, Chiribiri A, Schuster A et al (2013) Direct comparison of cardiac magnetic resonance and multidetector computed tomography stress-rest perfusion imaging for detection of coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 61:1099–1107

Mehra VC, Valdiviezo C, Arbab-Zadeh A et al (2011) A stepwise approach to the visual interpretation of CT-based myocardial perfusion. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 5:357–369

Taylor CA, Fonte TA, Min JK (2013) Computational fluid dynamics applied to cardiac computed tomography for noninvasive quantification of fractional flow reserve: scientific basis. J Am Coll Cardiol 61:2233–2241

De Bruyne B, Fearon WF, Pijls NH et al (2014) Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI for stable coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 371:1208–1217

Ko BS, Cameron JD, Leung M et al (2012) Combined CT coronary angiography and stress myocardial perfusion imaging for hemodynamically significant stenoses in patients with suspected coronary artery disease: a comparison with fractional flow reserve. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 5:1097–1111

George RT, Arbab-Zadeh A, Miller JM et al (2009) Adenosine stress 64- and 256-row detector computed tomography angiography and perfusion imaging: a pilot study evaluating the transmural extent of perfusion abnormalities to predict atherosclerosis causing myocardial ischemia. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2:174–182

Abbara S, Arbab-Zadeh A, Callister TQ et al (2009) SCCT guidelines for performance of coronary computed tomographic angiography: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 3:190–204

Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V et al (2002) Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart. A statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 18:539–542

DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL (1988) Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 44:837–845

Youden WJ (1950) Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 3:32–35

Takx RA, Blomberg BA, El Aidi H et al (2015) Diagnostic accuracy of stress myocardial perfusion imaging compared to invasive coronary angiography with fractional flow reserve meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 8:e002666

Coenen A, Rossi A, Lubbers MM et al (2017) Integrating CT myocardial perfusion and CT-FFR in the work-up of coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 10:760–770

Yang DH, Kim YH, Roh JH et al (2017) Diagnostic performance of on-site CT-derived fractional flow reserve versus CT perfusion. Eur Heart J Cardiovas Imaging 18:432–440

Ihdayhid AR, Sakaguchi T, Linde JJ et al (2018) Performance of computed tomography-derived fractional flow reserve using reduced-order modelling and static computed tomography stress myocardial perfusion imaging for detection of haemodynamically significant coronary stenosis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 19:1234–1243

Danad I, Raijmakers PG, Driessen RS et al (2017) Comparison of coronary CT angiography, SPECT, PET, and hybrid imaging for diagnosis of ischemic heart disease determined by fractional flow reserve. JAMA Cardiol 2:1100–1107

Danad I, Szymonifka J, Twisk JW et al (2016) Diagnostic performance of cardiac imaging methods to diagnose ischaemia-causing coronary artery disease when directly compared with fractional flow reserve as a reference standard: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 38:991–998

Sand NPR, Veien KT, Nielsen SS et al (2018) Prospective comparison of FFR derived from coronary CT angiography with SPECT perfusion imaging in stable coronary artery disease: the ReASSESS study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 11:1640–1650

Nissen L, Winther S, Westra J et al (2018) Diagnosing coronary artery disease after a positive coronary computed tomography angiography: the Dan-NICAD open label, parallel, head to head, randomized controlled diagnostic accuracy trial of cardiovascular magnetic resonance and myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 19:369–377

Echavarria-Pinto M, Escaned J, Macias E et al (2013) Disturbed coronary hemodynamics in vessels with intermediate stenoses evaluated with fractional flow reserve: a combined analysis of epicardial and microcirculatory involvement in ischemic heart disease. Circulation 128:2557–2566

Driessen RS, Stuijfzand WJ, Raijmakers PG et al (2018) Effect of plaque burden and morphology on myocardial blood flow and fractional flow reserve. J Am Coll Cardiol 71:499–509

Rodes-Cabau J, Gutierrez M, Courtis J et al (2011) Importance of diffuse atherosclerosis in the functional evaluation of coronary stenosis in the proximal-mid segment of a coronary artery by myocardial fractional flow reserve measurements. Am J Cardiol 108:483–490

Rief M, Zimmermann E, Stenzel F et al (2013) Computed tomography angiography and myocardial computed tomography perfusion in patients with coronary stents: prospective intraindividual comparison with conventional coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 62:1476–1485

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Associate Professor Brian Ko has been an invited speaker at symposiums sponsored by Canon Medical, St Jude, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Medtronic and Lilly. Associate Professor Sujith Seneviratne, Dr Jesper Linde, Dr Abdul-Rahman Ihdayhid and Dr Mathias Sorgaard have been invited speakers at Canon Medical sponsored meeting. Associate Professor Bjarne L. Norgaard has received institutional unrestricted research grants from Siemens and Heartflow. Dr Klaus F Kofoed has received institutional unrestricted research grants form Canon Medical and has been an invited speaker at symposiums sponsored by Canon Medical. The remaining authors have no relevant disclosures. This is otherwise an investigator initiated trial. There is no input to the study from any CT vendor or software company. HeartFlow acted as the core-lab for FFRCT assessment, but had no input in the study design, data analysis, interpretation of results or manuscript preparation.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ko, B.S., Linde, J.J., Ihdayhid, AR. et al. Non-invasive CT-derived fractional flow reserve and static rest and stress CT myocardial perfusion imaging for detection of haemodynamically significant coronary stenosis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 35, 2103–2112 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-019-01658-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-019-01658-x