Abstract

This study provides comprehensive evidence on the link between boardroom diversity and reduction of carbon emissions. Analyzing data from a sample of 344 UK-listed non-financial and unregulated firms over the period from 2005 to 2021, our findings indicate that task-oriented (i.e., tenure) and structural (i.e., insider/outsider) board diversity are important for reducing corporate carbon emissions while relational diversity does not appear to be useful. Furthermore, the study explores the role of external carbon governance, such as the Paris Agreement, on firms with weaker internal governance structures. The findings reveal that external governance plays a critical role in curbing emissions when internal governance is not effective. Overall, our research offers valuable insights for management and regulatory bodies on the interplay between various governance mechanisms internal and external to a firm. This knowledge could guide them in determining the right mix and degree of diversity in the boardroom to achieve environmental goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The steep rise in global temperatures in recent decades correlates with a surge in carbon emissions, a major contributing factor to climate change. Since pre-industrial times, there has been a significant increase in global average temperatures, exceeding 1 °C. This highlights an urgent need for countries to establish and meet carbon reduction targets to achieve net-zero emissions. Notably, there is a link between a nation’s carbon emissions and its standard of living, with the top emitters being China, the United States, and the European Union (Ritchie et al., 2020). In response to the climate change impacts, world leaders convened at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP21) in Paris on December 12, 2015, and agreed on a legally binding international treaty to set long-term goals for mitigating climate change.Footnote 1

Against this backdrop, research has increasingly focused on understanding the determinants and impacts of carbon emissions at the firm level.Footnote 2 This study adds to the body of literature that focuses on the determinants of carbon emissions for several reasons. Since carbon emissions are largely the result of using fossil fuels, firms reliant on these energy sources face multiple risks such as fossil-fuel energy prices and commodity price risk, higher technology risk, carbon pricing risk, and other regulatory interventions (Bolton & Kacperczyk, 2021) which may affect firm performance (Aswani et al., 2023; Kabir et al., 2021; Monasterolo & De Angelis, 2020; Zhang & Zhao, 2022). The understanding that carbon emissions have material implications for a company’s financial performance is widely accepted, establishing a key area of research. However, the pressing issue of climate change demands that attention now turns towards developing and applying effective strategies to reduce these emissions.Footnote 3 Firms are increasingly being held accountable to achieve carbon neutrality, necessitating the identification and implementation of strategies that will lead to net-zero emissions. This involves commitment to reducing absolute carbon emissions level and their intensity. Our study, employing an integrated agency and resource-dependence perspective (Hillman & Dalziel, 2003), aims to investigate whether and which board-level diversity are influential in mitigating corporate carbon emissions.

The examination of the association between board composition and the carbon emissions of a firm is scarceFootnote 4 (Haque, 2017). Addressing this gap, the current study makes significant empirical contributions and policy implications. First, it critiques existing literature that simplistically equates the presence of a single board characteristic, like the percentage of women, with board diversity. This study argues that such an approach does not capture the true essence of board heterogeneity. Instead, it adopts a more nuanced understanding, using the Blau index and the coefficient of variation as metrics to measure the board diversity, focusing on the varied attributes of directors. By doing so, it aims to provide a more accurate assessment of the impact of board diversity on carbon emissions. We draw upon relevant theoretical frameworks: integrated agency theory and resource-dependence theory (Hillman & Dalziel, 2003). As the main corporate governance mechanism (Hoang et al., 2018), board of directors’ monitoring (fiduciary) role of the board improves internal control or governance system, thereby reducing internal and external agency costs (Michelon et al., 2015). Additionally, the diversity of the board is seen as a valuable resource (Hoang et al., 2018; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978) because it contributes to the board’s capital—both human and relational—which aids in its advisory capacity including providing advice and counsel, maintaining legitimacy, facilitating communications, and offering tangible resources, thus, increasing the board effectiveness (Hillman & Dalziel, 2003). By integrating agency theory with resource-dependence theory, the study advocates for board compositions that leverage diverse-board capital to positively influence both monitoring and advisory functions of the board. The proposition is that a well-diversified board will effectively reduce corporate carbon emissions.

Secondly, the study delineates which measures of board diversity are most effective in reducing carbon emissions. This we show by examining the multiple diversity measures in the same equation to understand how different forms of diversity influence firm behavior on carbon emissions. This comprehensive approach also addresses potential endogeneity issues seen in previous studies, which may have selectively used measures that support their hypotheses—a practice known as cherry-picking. Such selective analysis can lead to results that are not robust or convincing and could provide inconsistencies in the literature. By examining a more complete set of board diversity measures, the current study provides more reliable results, offering guidance for policymakers and management on which forms of board diversity are most beneficial in the context of carbon emissions reduction.

Thirdly, for a better understanding of boardroom diversity, in line with Adams et al. (2015), we segment board diversity in the form of relational, task-oriented, and structural diversity. Relational diversity of directors relates to personal characteristics such as age, gender, and nationality which contribute mainly to building interpersonal relationships. Task-oriented diversity of directors relates to job-related characteristics such as education and tenure that distinguish directors’ functional capabilities. Structural diversity of directors such as insider/outsidership relates to the role of directors in the group structure. This detailed breakdown allows for a more targeted understanding of board diversity’s various aspects. Consequently, it empowers policymakers and management to prioritize the specific type of diversity that aligns with their strategic goals.

Moreover, we provide evidence regarding how different attributes of internal corporate governance (board diversity measures) interact with external corporate governance (Paris Agreement), building upon the study by Weir et al. (2002) who suggested the possibility of substitutionary nature of the bundle of governance mechanisms. The current study extends this understanding by examining whether various governance mechanisms complement or substitute each other in the context of reducing carbon emissions. In doing so, we disentangle a complex array of governance mechanisms (Oh et al., 2018) that operate both within and beyond the firm’s internal environment. This analysis can provide deeper insights into how internal governance structures can be effectively aligned with external environmental commitments, or vice-versa, to optimize carbon reduction efforts.

The study covers an extensive dataset spanning 17 years, from 2005 to 2021, and includes 344 firms listed in the London Stock Exchange. Empirically, we use a Pooled Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression model to investigate the link between various types of boardroom diversity and corporate carbon emissions, while controlling for firm-specific characteristics. Additionally, it incorporates industry, year, and industry-year fixed effects to control for both time-specific trends and industry-related factors that could vary over time or be consistent throughout.Footnote 5 The findings reveal a mixed relationship between boardroom diversity and carbon emissions among sampled firms. Specifically, we find that task-oriented and structural board diversities are necessary to reduce the corporate carbon emissions in general while relational board diversity may not be effective. Our main results are persistent through various tests for endogeneity and robustness, including Instrumental Variable-Two Stages Least Squares (IV-2SLS), the Heckman selection model, and through adjustments in the model specification, variable measures, and sample inclusion/exclusion. Further, we test the role of external carbon governance when internal governance is not strong. In a Difference-in-Difference (DID) analysis, the study uncovers that companies with less diverse boards prior to the Paris Agreement have made significant strides in reducing carbon emissions following the Agreement. This effect is notably marked in non-relational (task-oriented and structural) diversity measures, suggesting that these aspects of boardroom diversity may act as substitutes for external governance influences in affecting carbon emissions.

In the remainder of the paper, Sect. ‘Theoretical framework and hypotheses development’ discusses the theoretical framework and hypotheses development. Then we report our data sources and study design in Sect. ‘Data and study model.’ Sect. ‘Results’ presents the study results. Finally, Sect. ‘Discussion and conclusion’ present a comprehensive discussion including practical implications, limitations, and future research.

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

Theoretical Framework

This study puts forward that both agency theory and resource-dependence theory are crucial and complementary theoretical frameworks when examining the relationship between boardroom diversity and corporate social responsibility (CSR). Agency theory emphasizes the importance of incentives in enhancing board effectiveness but does not fully address the diversity of board members’ abilities in monitoring activities. Conversely, resource-dependence theory highlights the value of board capital—such as skills and knowledge—without adequately considering how incentives influence the provision of resources and behavior within firms (Hillman & Dalziel, 2003). Following the works of Dodd et al. (2022) and Haque (2017), our study draws on both these theoretical perspectives. Hillman and Dalziel (2003) have integrated these theories, arguing that board capital impacts not only the monitoring capabilities of the board but also its ability to provide valuable resources. The current study adopts this integrated approach to offer a more comprehensive analysis of how boardroom diversity influences a firm’s CSR initiatives.

Pfeffer and Salancik (1978)’s resource-dependence theory suggests that boards serve to link the firm with external entities, helping to manage environmental dependencies. Directors contribute by providing four benefits to the organization: (i) information in the form of advice and counsel; (ii) creation of communication channels between the firm and its external environment; (iii) commitments of support from important organizations in the external environment; and (iv) legitimacy. Directors’ diverse identities and backgrounds bring essential human and social capital to the firm, enriching it with a variety of skills, expertise, and connections (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978). This diversity in human and social capital facilitates the firm’s access to resources, networks, advice, and legitimacy (Haque, 2017; Mallin & Michelon, 2011). Consequently, board composition significantly affects board effectiveness. A diversified board structure plays a crucial role in advising management on strategy design and implementation, known as the resource provision function (Hillman et al., 2008).

The study proposes that resource-dependence theory illuminates the connection between a board’s heterogeneous abilities and its monitoring role. A board composed of diverse members can be viewed as the ultimate outsider, as it benefits from increased independence and brings varied backgrounds and non-traditional characteristics to the table (Carter et al., 2003). Such diversity helps to mitigate issues like cohort mentality and ‘groupthink’ (Li & Wahid, 2018), promoting a more independent and critical approach to decision making. Moreover, diverse boards are better equipped in their monitoring function due to the effective distribution of tasks (Kyere & Ausloos, 2021) and a better understanding and execution of appropriate courses of action (Hillman & Dalziel, 2003). This diversity strengthens the board’s assertiveness in upholding internal controls and governance systems, thereby reducing both internal and external agency costs (Michelon et al., 2015). An integrated approach that combines agency and resource-dependence theories suggests that the elements of board capital, which are instrumental for providing resources, simultaneously enhance the board’s monitoring capabilities (Hillman & Dalziel, 2003). This perspective underscores the dual benefit of board diversity, serving both as a resource and as a means to improve fiduciary oversight.

Hypothesis Development

Below we review relevant literature on boardroom diversity and corporate carbon emissions to formulate three hypotheses that will be tested.

Relational Board Diversity and Carbon Emissions

Prior studies show a mixed association between relational board diversity and firm performance, including the CSR, which seems to be both positive (Beji et al., 2021; Janahi et al., 2022) and insignificant or even negative (Arnaboldi et al., 2020; Katmon et al., 2019). When it comes to research specifically examining carbon emissions, there is a dearth of studies, which have a particular focus on the gender diversity (Kyaw et al., 2022; Nuber & Velte, 2021). For instance, Kyaw et al. (2022) demonstrated that boards with gender diversity in U.S. firms tend to reduce environmental emissions by 9% more than their industry counterparts. Nuber and Velte (2021) found that a higher presence of female directors on European STOXX600 non-financial firms’ boards relates with lower carbon intensity. Research on the impact of national diversity on carbon emissions also yields inconclusive results. Elleuch Lahyani (2022) and Mardini and Elleuch Lahyani (2022) found that nationality diversity positively associates with carbon disclosure in French non-financial firms. On the contrary, Valls Martínez et al. (2022) found that national cultural diversity on the boards of MSCI listed European firms leads to higher carbon emissions. Authors argue that directors different from the country headquarter might be less interested than local ones in protecting the environment, potentially leading to interpersonal conflicts within the board. However, these studies often measure diversity solely based on the proportion of women or nationality on boards, which does not fully explore the effects of board diversity per se. There is clearly room for further research to explore these dynamics more deeply and to understand the direct effects of different types of diversity on carbon emissions.

Given the existing literature and the theoretical framework that suggests varied perspectives from directors of diverse ages, genders, and nationalities can enhance board capital, which is beneficial for reducing corporate carbon emissions, the first hypothesis is proposed as follows:

H1

Relational board diversity is negatively associated with carbon emissions.

Task-Oriented Board Diversity and Carbon Emissions

Existing studies investigating the relationship between task-oriented board diversity measures and firm financial performance generally indicate positive results (Arnaboldi et al., 2020; Harjoto et al., 2018; Ji et al., 2021). The relationship also seems to be consistent with CSR performance (Ben Selma et al., 2022; Katmon et al., 2019). However, there are instances where the relationship between educational and functional backgrounds and CSR is reported to be negative or insignificant (Aladwey et al., 2022; Khan et al., 2019). When it comes to the specific relationship between task-oriented board diversity and carbon emissions, fewer studies are found. Al-Qahtani and Elgharbawy (2020) who investigated the sample of FTSE350 UK firms associated with CDP and found that the diversity of financial expertise of directors negatively influences the GHG disclosure while board tenure has no significant effect. Aliani (2023) studying the best 100 citizen companies in the Russel 1000 index found that directors’ functional background (skills diversity) is positively and significantly related to emission score, indicating an improvement in carbon performance. The limitations noted in these studies include a narrow focus on specific time periods and samples, which may not provide a comprehensive understanding of the relationship. Moreover, there is a lack of clarity on whether task-oriented diversity consistently relates to specific carbon emissions metrics, as previous research primarily concentrated on carbon disclosure and overall emission scores, rather than actual emission levels and intensities. This gap suggests a need for further investigation into how task-oriented board diversity impacts these more detailed aspects of a firm’s carbon footprint.

Considering the previous research and our theoretical framework, which posit that diverse perspectives from directors with varied educational backgrounds and tenure enhance board capital and thereby aid in reducing corporate carbon emissions, we articulate our second hypothesis as follows:

H2

Task-oriented board diversity is negatively associated with carbon emissions.

Structural Board Diversity and Carbon Emissions

Studies generally show a positive relationship of structural board diversity measures on CSR performance (Beji et al., 2021; de Villiers et al., 2011; Fernandes et al., 2019). Haque (2017) and Liao et al. (2015) specifically examined the association between board independence and carbon emissions of UK firms, finding a positive association between board independence and both GHG emission reduction initiatives or GHG disclosure of firms. In this line, Elleuch Lahyani (2022) looked into the French listed non-financial firms that responded to CDP questionnaires and found that firms with more independence boards tend to disclose more carbon emissions information. Homroy and Slechten (2019) also assessed the sample of the FTSE350 UK firms and found that non-executive directors can reduce GHG emissions through two channels of resource provision, i.e., previous experience and network connections. On the other hand, a study by Narsa Goud (2022) involving Indian listed non-financial firms indicated that board independence might lead to an increase in carbon emission of firms. We note that there is a lack of clarity on whether structural diversity per se, as measured by structural heterogeneity, consistently relates to specific carbon emissions metrics, as previous research primarily concentrated on the proportion of independent and non-executive directors.

In light of the previous research and the theoretical foundation that posits diverse perspectives from directors with various roles within the group structure enhance board capital, which in turn should be conducive to reducing corporate carbon emissions, the third hypothesis is formulated as follows:

H3

Structural board diversity is negatively associated with carbon emissions.

Data and Study Model

Sample

The study utilizes a comprehensive unbalanced panel data set that spans 17 years, from 2005 to 2021,Footnote 6 focusing on UK-incorporated firms listed on the London Stock Exchange. The inclusion criteria for the firms in the study are based on the availability of carbon emissions data, which is sourced from the Refinitiv ASSET4 database available via Refinitiv Eikon. Boardroom diversity information is obtained from BroadEx, while financial data is drawn from S&P Capital IQ. The study’s sample was refined by matching data from these different databases, and by excluding firms from the financial and utilities sectors, as these industries are often subject to different regulatory and operational dynamics that could skew the results. Observations missing baseline variable data were also omitted. After these exclusions, the final sample for analysis includes 2657 firm-year observations across 344 different firms.

Main Variables

In this study, the primary variable of interest is corporate carbon emissions, specifically the greenhouse gases (GHG) emitted by firms annually. GHG emissions include a variety of gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), and sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), all of which contribute to global warming by absorbing and emitting radiant energy. To measure these emissions, the study adopts the standard metric of ‘carbon dioxide-equivalents’ (CO2e), which accounts for CO2 emissions and the warming impacts of other GHGs combined (Ritchie et al., 2020). Prior studies generally used the natural logarithm of total CO2 equivalents emissions in tons (Haque, 2017; Muttakin et al., 2022; Valls Martínez et al., 2022) as a measure for carbon performance. However, since absolute emissions tend to correlate strongly with the size and performance of a firm, using emission intensity is a better way to measure a firm’s carbon footprint (Aswani et al., 2023). Thus, we also use carbon emissions intensity, as the total CO2 equivalents emissions in tons divided by total sales revenue in million (USD), as our second measure of carbon performance.Footnote 7 To mitigate data noise resulting from scaling absolute emissions by an output measure, the natural logarithm of emissions intensity is used (Benlemlih & Yavaş, 2023; Downar et al., 2021; Hossain et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2023). We do not use direct and indirect emissions and intensities as our measures due to their strong correlation with total emissions.Footnote 8

For the independent variable of boardroom diversity, the study employs three different measures: relational board diversity, task-oriented board diversity, and structural board diversity in alignment with the framework set forth by with Adams et al. (2015) and as utilized in prior studies (Cumming & Leung, 2021; Harjoto et al., 2018; Ullah et al., 2020). In line with above-referenced literature, we use directors’ gender, age, and nationality in terms of relational boardroom diversity; directors’ tenure and education in terms of task-oriented boardroom diversity; and directors’ outsidership (non-executive directors) in terms of structural boardroom diversity.Footnote 9 To quantify these forms of diversity, the study uses the Blau Index for gender, nationality, and insider/outsidership diversity. The Blau Index is calculated as [1—∑ (Pi2)], where P is the proportion of each member in each of the i number of categories. The range of the index is dependent on the number of categories, where the lower limit is 0 and upper limit is (i – 1)/i (Miller & Del Carmen Triana, 2009). Therefore, Blau index for two categories can range from 0 when there is perfect homogeneity (e.g., either male or female directors on a board) to 0.50 when there is perfect heterogeneity or diversified group (e.g., equal representation of both male and female directors on a board). This way, Blau index transforms the categorical variable into continuous variable. The Blau Index is an appropriate measure for this study for two main reasons. First, it effectively measures categorical heterogeneity, which is relevant since gender, nationality, and outsidership are categorical variables in the study. The conversion of categorical variables into continuous variables enhances the comprehension of diversity across a spectrum. Second, employing the Blau index aligns with our assertion that heterogeneous groups contribute valuable resources and diverse perspectives to boards, thereby enriching board capital, which may not be attained if a board is homogeneous.Footnote 10 Therefore, we are inclined to employing diversity proxies that emphasize heterogeneity, and the Blau Index stands as a common measure utilized in board diversity literature (Ben Selma et al., 2022; Harjoto et al., 2018; Miller & Del Carmen Triana, 2009; van den Oever & Beerens, 2021).

Additionally, for the continuous attributes of board diversity, such as directors’ age, tenure, and education, the study applies the coefficient of variation as a measure of diversity, as the Blau Index is unsuitable for continuous data. The coefficient of variation is calculated as the ratio of standard deviation of each measure to the mean of each (Aggarwal et al., 2019; Arnaboldi et al., 2020; Janahi et al., 2022). A higher value indicates greater variability relative to the mean, while lower value suggests more consistency. Indeed, the coefficient of variation’s advantage lies in its emphasis on the relative variation of a variable rather than its absolute magnitude. Given that the diversity measures can have varying ranges, the study standardizes each index or value to ensure they all have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. The standardized measures are then utilized in the regression analysis to determine their relationship with the dependent variable of interest. This standardization process facilitates comparison and integration within the regression models.

To account for firm-specific characteristics that might drive the carbon performance, we include a set of control variables such as firm size, firm age, leverage, profitability, sales growth, price volatility, and cashflow. We control firm size as larger firms are likely to have positive association with performance in terms of emissions per unit of output, largely due to economies of scale benefits. We control firm leverage because high-leveraged firms might have constraint in lowering the carbon emissions (Alam et al., 2022). The capability of growth and profitable firms to invest in carbon reduction measures is also accounted for. Firms’ price volatility and cash availability are associated with carbon prices and emissions (Alam et al., 2022; Ibrahim & Kalaitzoglou, 2016); thus, we control these variables. Finally, corporate governance aspects such as board size and institutional ownership are controlled for. A larger board may indicate greater diversity and a stronger orientation towards CSR (Beji et al., 2021), while institutional ownership is linked to carbon performance due to the risks associated with carbon (Bolton & Kacperczyk, 2021). All variables are defined in Table 1.

Empirical Model

To empirically examine the proposed hypotheses (H1, H2, and H3) that investigate the link between boardroom diversity and carbon emissions, the study employs the Pooled Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression method to test the model shown in Eq. (1):

In the specified model, carbon emissions, as measured by the natural logarithms of absolute total CO2 equivalent emissions and total CO2 equivalent emissions divided by total revenues, of a firm i in the year t is a function of various forms of boardroom diversity. These include relational diversity (gender, age and nationality), task-related diversity (education and tenure), and structural diversity (insider/outsider directors). We include a set of control variables that potentially affect the carbon emissions and boardroom diversity of firms. To address potential endogeneity issues, as often done in CSR-FP research, all independent variables are lagged by one year (Shahgholian, 2019). The model also includes multiple fixed effects, denoted by the symbol δ, to account for unobserved heterogeneity. Yearly fixed effects adjust for time trends, while industry (GICS two-digits) fixed effects control for emissions differences attributable to industry characteristics. Further, industry-year fixed effects are employed to capture regulatory and economic changes that affect industries differently over time; thus, simultaneously controlling for industry-specific and temporal influences on board diversity and carbon performance. Finally, to correct for any correlation of residuals within firms and across industries, the model applies double-clustering of standard errors at both the firm and industry levels.Footnote 11

Results

Descriptive Statistics

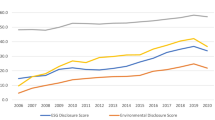

Table 2 summarizes the variables used in the study. The emissions are presented in both absolute and relative (scaled by sales revenue) terms and in log levels. Absolute and relative measures have a mean (standard deviation) of 10.675 (2.656) and 3.31 (1.749), respectively. The minimum value of lntotalintensity is −4.609, this does not mean that the emissions value of a firm is negative, but it indicates that carbon emissions value is 0.00996 times its revenue (i.e., e−4.609 = 0.00996). For board diversity measures, the Blau Index is used to quantify gender, nationality, and executive/non-executive directors’ diversity. This index can range from 0 (indicating no diversity) to 0.5 (indicating a balanced diversity),Footnote 12 with the data showing average Blau indices of 0.302 for gender and 0.264 for nationality, suggesting relatively low diversity in these areas. Executive/non-executive directors’ diversity is higher, with an average Blau Index of 0.404. Additionally, the mean diversity within boards in terms of age, education, and tenure, measured by the coefficient of variation, is presented. The data indicates that age diversity is less heterogeneous (mean of 0.12) compared to education (mean of 0.551) and tenure (mean of 0.2), suggesting a narrower range of ages but a wider variety of educational backgrounds and tenure among board members.

Table 3 reports correlation coefficients between the variables used. It shows a strong positive correlation of 0.7703 between the two dependent variables: total CO2 emissions and total emissions intensity (emissions scaled by sales revenue). This high correlation indicates that firms with higher absolute emissions also tend to have higher emissions relative to their revenue. The correlation coefficients suggest that age, education, and executive/non-executive directors’ diversity are significantly negative with the absolute carbon emissions while gender, education, and non-executive directors’ diversity are significantly negative with the relative carbon emissions. Educational diversity has significantly negative correlation with both carbon emissions measures while tenure is insignificant. These initial correlations provide an indication that board diversity is linked to carbon emissions, but they also suggest that the nature of the relationship may vary depending on the type of diversity.

The variables used in the study exhibit correlation coefficients lower than 0.65. This level suggests that multicollinearity, a statistical phenomenon where predictor variables in a regression model are highly correlated, may not be a serious concern. We also tested the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to ensure the absence of any multicollinearity issue. The VIFs for the variables in this study are all below 2.66, which is well within the acceptable range, providing further confirmation that multicollinearity is not a problem.

Regression Results

Table 4 presents baseline regression results, including different forms of boardroom diversity measures. The first six models examine three distinct forms of boardroom diversity separately, while the final two models, as our main models, consider comprehensive diversity, incorporating all forms of boardroom diversity measures.Footnote 13 The results in both separate and main models reveal that tenure and executive/non-executives directors’ diversity are significant and negatively associated with carbon emissions. Further these measures show a consistent relation across different models and both measures of carbon emissions. In contrast, age and nationality diversity are generally positively related to emissions intensity measure. The overall interpretation of these results suggests that task-related and structural forms of boardroom diversity tend to have a negative impact on carbon emissions, meaning that greater diversity in these areas is associated with lower emissions. In contrast, relational diversity attributes do not appear to have a beneficial effect on carbon emissions. This indicates that while some types of boardroom diversity contribute to lowering emissions, others may not be as effective or may even be associated with higher emissions.

Endogeneity

Our baseline results could be affected by endogeneity issues. First, the endogeneity may come from endogenous nature of our board diversity measures that might be correlated with error terms. Second, these measures may be determined endogenously by firm-related characteristics, thus, prevailing a self-selection issue. Third, omitted variables bias may question the validity of baseline results. We employ several endogeneity tests to deal with these issues. Using IV-2SLS model, we aimed at isolating the exogenous variation of boardroom diversity that impacts carbon emissions. A proper instrument should directly affect board diversity measures but not the firm-level carbon emissions. We use two instruments, cohort firms’ board diversity level and further lagged values of each diversity measure. We use other firms’ 2-digit zip code assignment to find a focal firm’s cohort group and their board diversity. The rationale is that the firm’s board diversity is influenced by a time-invariant component that is associated with its geographical location. Empirically, Jiraporn et al. (2014) shows evidence that a firm’s CSR policy is significantly influenced by the CSR policies of firms in the same location. Similar instruments are also used in prior studies (Talavera et al., 2018; Tanthanongsakkun et al., 2023). Moreover, the lagged value as the instrument is used in several studies (Alam et al., 2022; Cui et al., 2018; Nekhili et al., 2018) because it is likely to be exogenous to the contemporaneous boardroom diversity measure (Wintoki et al., 2012). Past levels of board diversity are used to predict current levels under the assumption that firms with a history of higher diversity will continue to maintain it to uphold their legitimacy and avoid reputational damage, as per legitimacy theory. On the other hand, these instruments are less likely to influence the dependent variable directly but through the independent variable.

In Table 5, Models 1–6 provide first-stage regression results supporting the validity of the chosen instrumental variables: cohort firms’ board diversity and further lagged values of board diversity measures. These instruments are generally found to be significantly and positively associated with various forms of board diversity measures, suggesting that they are relevant instruments. Models 7–8 further reinforce the strength of the instruments, as indicated by the ‘Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic’ being above the commonly accepted threshold of 10. In the presence of heteroskedasticity, the traditional Cragg-Donald-based F-statistic is not valid, so we also report Kleibergen-Paap Walk rk F-statistic. These tests suggest that the instruments are not weak, meaning they provide a reliable source of exogenous variation for the endogenous predictors. The second-stage regression results from Models 7–8 are consistent with the baseline results, implying that the instrumental variable approach does not alter the main findings of the study.

The study addresses the self-selection issue, which arises if certain types of firms are more likely to choose board diversity. For example, larger firms or those under greater social scrutiny, as well as more profitable firms, might be more inclined to diversify their boards (Arnaboldi et al., 2020). To deal with this, we employ a Heckman selection two-step model where the first step involves predicting the likelihood of a firm having above sample median board diversity. For this, first we create selection variable board diversity which is the indicator variable indicating one if a firm has above sample median board diversity in at least one of the six boardroom diversity measures, and zero otherwise. We use baseline variables and industry and year fixed effects for the selection equation. Further, a dummy variable, ‘policy for diversity and opportunity’ is included to satisfy exclusion restriction requirement. This variable is based on the expectation that firms with such policies are more likely to exhibit higher levels of diversity across the firm, including the boardroom. The first-stage results in Table 6 provide evidence to support our assumption that boardroom diversity is significantly related to the policy for diversity and opportunity. Then, we used the predicted lambda (inverse Mills ratio) in the second-stage Heckman model; however, the insignificant lambda indicates that the self-selection bias may not be a serious problem in the study. Nevertheless, our results are similar to the main results even after using the sample correction model.

Our data may have an issue of omitted variables bias. To address this, prior research has often utilized firm fixed effects, which control for unobserved time-invariant characteristics of firms. However, we note that our board diversity variables exhibit limited variation over time. Consequently, employing firm fixed effects could potentially bias their results due to this low within-firm variation (Homroy & Slechten, 2019). To account for omitted variables, we further include several variables that might affect our dependent variable in baseline models. First, we include crises dummies for financial crisis and Covid-19 years in which carbon emissions emitted by firms should be reduced due to less economic or industrial activities. Second, we include UK carbon reporting regulationFootnote 14 and Paris Agreement dummies. Table 7 presents regression results after accounting for these omitted variables. The presence of these controls in the regression models helps to affirm the robustness of the study’s main findings, indicating that the relationship between board diversity and carbon emissions remains even when considering major economic disruptions and regulatory changes.

Robustness Tests

In this sub-section, we perform further tests for the robustness of our main results. First, we account for the issue of a cross-sectional dependence across firms in panel data due to possible correlations of unobserved factors across firms. We use Fama–MacBeth approach for correcting a cross-sectional correlation. This method requires two-step procedure in which first we run cross-sectional regressions for each year to capture the time-specific effects and avoid the issue of cross-sectional dependence. We then obtain coefficients by averaging across yearly estimates. The results presented in Table 8 show a result consistent to our main results.

Second, we employ alternative measures of carbon performance where we use the carbon emissions scaled by total assets and total CO2e emissions reported to Carbon Disclosure Project.Footnote 15 The total assets as a scale considers the total book value of assets owned by firms that has an economic value. This standardization is consistent with prior studies (Kabir et al., 2021; Zhang & Zhao, 2022). Further, we consider the CO2e emissions reported by firms to CDP. CDP data are increasingly used in ESG research (Qian & Schaltegger, 2017). CDP, using a questionnaire, collects carbon data in a standardized and comprehensive way from firms. Additionally, for boardroom diversity measures, we use indicator variables (Janahi et al., 2022). The indicator variables denote one if a firm’s board diversity is above the mean of the sample for a given year, and zero otherwise. Table 9 reports results using alternative measures of carbon emissions and boardroom diversity in Panel A and B, respectively. The use of these alternative measures further affirms the potential relationship between boardroom diversity and carbon performance in line with our main models.

Third, we employ alternative sample using exclusion strategies. We exclude period after the UK mandatory carbon reporting regulation and limit our study period from 2005 to 2013 Sept.Footnote 16 This exclusion limits our sample to less stringent carbon regulation years which is likely to rule out the possibility that nationwide carbon scrutiny is driving our results. Furthermore, since firms participating in emissions trading scheme (ETS) have more incentives to reduce their carbon emissions compared to non-participating firms, we re-run baseline models after excluding ETS firms. This helps to ensure that the results are not confounded by the effects of participation in this market-based approach to pollution control. In both exclusion cases, we find our untabulated results consistent with main results indicating the likely effect of boardroom diversity on carbon emissions. Moreover, instead of solely focusing on educational diversity, the study also considers the professional backgrounds of board members. This is quantified using the Blau index which considers two categories: the proportion of directors with and without relevant industry experience and financial expertise. Then we replace the educational diversity using the Blau index calculated for the professional diversity. These tests are unreported for brevity but available upon request. By showing that the results hold across various specifications and checks, the study provides stronger evidence for the relationship between boardroom diversity and carbon emissions.

External Governance

The Paris Agreement set the goals to substantially reduce global greenhouse gas emissions to limit the global temperature increase in this century to 2 °C while pursuing efforts to limit the increase even further to 1.5 °C. A consensus was adopted by 196 countries in December 2015 at the 21st Conference of Parties (COP21) to review countries’ commitment every five years and support developing countries to mitigate climate change, strengthen resilience, and enhance abilities to adapt to climate impacts. This has introduced new regulatory costs for businesses, especially in sectors that are energy and carbon-intensive, due to measures like carbon taxes. Overall, the Paris Agreement largely affected the personal, social, and market behavior and practices, steering them towards contributing to its climate objectives (Jakučionytė-Skodienė & Liobikienė, 2022; Monasterolo & De Angelis, 2020).

The Paris Agreement as an omitted variable accounted in our earlier analysis and as reported in Table 8 indicate a significantly negative association with corporate carbon emissions. In additional analysis, we consider the Paris Agreement as an external governance mechanism in reducing carbon emissions, and an examination into the dynamic between internal and external governance mechanisms is undertaken. If the Paris Agreement were to serve as an alternative to internal governance practices, a notable decline in emissions is anticipated, particularly from firms with less diverse boards. Weir et al. (2002) discussed the possibility of substitutionary nature of the bundle of governance mechanisms. To delve deeper into this empirical question, we use the Difference-in-Differences design as in Eq. (2) below:

where Post is the indicator referring to the fiscal year ending after December 2015, which is when the Paris Agreement was implemented.Footnote 17 Similarly, we identify the artificially treated firms based on their level of boardroom diversity, comparing their diversity levels to the industry average before the Paris Agreement. Then we create Treat_xx for firm-year observations that have below industry average values in diversity measures. The rationale is that firms with less diverse boards, which presumably have lower board capital, emit more carbon due to their limited ability to evaluate and implement carbon reduction strategies—a perspective supported by the integrated agency and resource-dependence theory. Thus, we expect such less diverse-board firms to benefit from the external governance. Table 10 provides evidence that less diverse boards in terms of education and executive/non-executive directors’ diversity tend to emit more carbon emissions in general, consistent with our main results that task-oriented and structural board diversity is significantly associated with corporate carbon emissions. A significant and negative Post value underscores the Paris Agreement’s effectiveness in reducing emissions. Our main interest of the study is the interaction terms between Treat_xx and Post that capture the effect of external governance when the internal governance is weak. The significant and negative coefficients in Treat_education*Post, Treat_tenure*Post, and Treat_NED*Post indicate that external governance is effective for firms that lag in task-oriented and structural board diversity relative to their industry peers. However, the role of external governance with respect to relational board diversity is inconsistent which further re-enforces the controversial effect of relational board diversity in reducing corporate carbon emissions.

The results align with expectations that environmental regulations or initiatives, like the Paris Agreement, are most impactful in enhancing environmental performance or mitigating climate risks, especially where there is a lack of firm-level sustainability efforts. Boards with limited task-related and structural diversity, as opposed to relational diversity, are found to be less inclined towards sustainable practices, as indicated by our baseline results. Consequently, external governance measures, such as initiatives aimed at carbon reduction, are crucial for improving corporate carbon performance in firms where task-oriented and structural board diversity is not strong, due to their ability to substitute for internal governance deficiencies.

Discussion and Conclusion

Recent shifts in corporate control mechanisms and the impact these changes bring on the role of boards is unclear (Huson et al., 2001; John & Senbet, 1998). In the current paper, drawing upon agency theory and resource-dependence theory, we posit that the monitoring and resource provision roles of board capital lead to board effectiveness (Hillman & Dalziel, 2003). Conceptually, it is plausible that board diversity increases board effectiveness as the more diverse boards tend to be more creative, innovative, and may consider a wide range of alternatives when they go through the decision-making process (Arnaboldi et al., 2020). Additionally, board diversity is thought to strengthen board independence, which in turn can reduce information asymmetry and better align stakeholder interests (Elleuch Lahyani, 2022; Katmon et al., 2019). While much of the current research has concentrated on gender diversity, there is a call for examining the impact of other diversity aspects like nationality, culture, and education (Hillman, 2015). Furthermore, the consideration of multiple diversity forms not only allows us to disentangle the type of board diversity that are most influential concerning corporate carbon emissions but also addresses the endogeneity that plagued earlier research, which may have selectively chosen certain measures of diversity that supported their findings, as a cherry-picking study. An analysis of UK-listed firms spanning from 2005 to 2021 showed mixed findings regarding the relationship between boardroom diversity measures and carbon emissions. In particular, task-oriented and structural diversity within the board were found to be essential, while relational diversity seemed ineffective in contributing to the reduction of corporate carbon emissions.

Our finding that the task-oriented and structural board diversity may matter is consistent with board diversity and FP literature in general (Aladwey et al., 2022; Ben Selma et al., 2022; Ji et al., 2021; Long et al., 2005). The findings underscore the significance of boardroom diversity, particularly non-relational types, in affecting firm outcomes through the board’s monitoring and advisory roles, which seems to be equally relevant on carbon emissions as the outcome. In particular, current study suggests that diversity in tenure and among executive/non-executive directors can prevent director entrenchment, which is critical for the board’s effectiveness. This benefit is largely attributed to the board’s fiduciary, or monitoring, function. (Li & Wahid, 2018; Long et al., 2005; Mura, 2007). Moreover, the representation of diverse tenure and insider–outsider members on the board can mitigate the ‘groupthink’ or group cohesiveness by promoting divergent views and ideas, thereby enhancing creativity and innovation to problem solving—key elements of the board’s advisory function (Cumming & Leung, 2021). The findings reinforce the reasoning behind UK corporate governance codes that aimed at improving the diversity of skills, experience, independence, and knowledge needed on a successful board.Footnote 18

The study also indicates that relational diversity, such as differences in age and nationality among board members, does not appear to aid in reducing carbon emissions and, in fact, may have a positive association with higher emissions. This suggests that the personal differences among directors may not effectively contribute to the board’s monitoring and resource provision roles in the context of managing corporate carbon emissions. Specifically, age diversity could be linked to increased emissions because boards with a wide age range may experience interpersonal conflicts regarding risk, prudence, and wealth perspectives, which can impede the board’s effectiveness (Talavera et al., 2018). Further, the age diversity measure is less heterogenous or more time-persistent in our data, potentially limiting the ability to fully leverage the advantages of diverse age representation on the board. Nationality diversity’s positive impact on carbon emissions might stem from the increased conflict and communication challenges it introduces. One plausible explanation is that foreign directors might not prioritize the firm’s carbon performance as highly as local directors, possibly because they are not directly engaged with the local environment where the firm operates, affecting their involvement in and commitment to local environmental issues (Valls Martínez et al., 2022). The study’s findings on gender diversity diverge from previous research, which generally suggests a positive link between board gender diversity and lower carbon emissions (Kyaw et al., 2022; Liao et al., 2015). The discrepancy might arise from the fact that past studies have not specifically analyzed the impact of gender diversity itself; instead, they have measured the proportion of women on boards, which does not accurately represent gender heterogeneity but rather emphasizes gender homogeneity. The results suggest that relational diversity in the boardroom, which encompasses interpersonal differences among directors, may lead to conflicts that could hinder efforts to reduce carbon emissions. Our results are robust to endogeneity tests such as IV-2SLS, Heckman selection model, accounting for omitted variables, alternative specification such as Fama–MacBeth regression, alternative measures of both dependent and independent variables, and alternative samples.

In an additional analysis, we investigate the role of the external governance on the association between boardroom diversity and carbon emissions. We posit that boards with weaker internal governance (boardroom diversity) may be benefited by external governance which we examine using the Paris Agreement as the exogenous shock to reduce carbon emissions. Our results show that the Paris Agreement is likely to reduce the corporate carbon emissions in firms with less diverse boards, especially in terms of task-oriented and structural diversity. This implies that such boardroom diversity is more useful when external governance is not in place, or alternatively, external governance can compensate for a lack of it. This finding adds to the understanding of the interplay between various corporate governance mechanisms, as discussed in existing literature (Oh et al., 2018; Weir et al., 2002). Particularly, it elaborates on the concept put forth by Weir et al. (2002) which suggests that internal and external governance mechanisms may not function in isolation but could potentially act as substitutes for one another. The current study illuminates this notion by demonstrating a potential substitutive effect between internal governance (boardroom diversity) and external initiatives (such as the Paris Agreement) in the context of mitigating carbon emissions.

Managerial and Policy Implications

Our results may guide management and policymakers in identifying and improving more relevant or effective board diversity forms when multiple diversity both internal and external to firms come into play.

The management implication from the study suggests that firms should strive to structure their boards in a manner that balances task and structure-related board characteristics. As structural diversity is more a regulatory requirement in many jurisdictions, management is advised to identify a range of task-related characteristics, extending beyond those examined in the current study, such as industry experience and functional background, which have the potential to enhance corporate behavior. Similarly, firms should assess the existing pool of candidates and actively identify or nurture suitable candidates to improve such diversity within their boards. Equally crucial is fostering an organizational culture that facilitates both the exploitation and exploration of knowledge among directors to fully leverage the benefits of diversity. Firms should implement strategies such as increasing the frequency of board or committee meetings and promoting informal networking activities to facilitate the sharing and exchange of ideas among directors. In light of the growing policy focus on Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI), the negative or insignificant relational diversity measures do not mean that these are detrimental to overall firm performance. Instead, it suggests the need for alternative course of actions to realize the benefits. Miller and Del Carmen Triana (2009) and Cumming and Leung (2021) point out the reputational and innovation benefits of relational diversity. Thus, firms should acknowledge and channel diversity, such as gender and nationality, towards areas where they can positively influence firm performance. Moreover, management may also consider job-related skills when appointing directors with relational characteristics.

Our findings offer valuable guidance to policymakers and regulators suggesting them to evaluate the effectiveness of diversity quotas and implement optimal diversity policies. We endorse the current UK corporate governance code which emphasizes the board outsidership which remains relevant even in the context of corporate carbon emissions reduction. However, the balanced representation of outsiders may prove to be the optimal strategy for improving carbon performance. Likewise, our study adds to the debate on staggered boards acknowledging the logic that such boards help to reduce the group cohesiveness and entrenchment by altering the mix of board member term limits which is one of the crucial ways in enhancing board effectiveness (Li & Wahid, 2018). Accordingly, we recommend that policymakers prioritize task and structure-related board characteristics and their diversity when establishing boardroom diversity codes. For instance, highlighting factors such as education level, industry experience, functional background, and independence, among other forms of task and structure-related diversity, could be beneficial. Moreover, the significant impact of external governance on firm-level carbon emissions underscores the importance for policymakers to formulate relevant institutional policies on CSR and closely monitor their implementation. However, it might be beneficial if policymakers also take into consideration internal corporate governance and establish thresholds to identify entities that may require such regulatory pressures.

Limitations and Future Research

The study acknowledges several limitations. First, our boardroom diversity measures are based on the logic of group heterogeneity; thus, readers should be cautious in comparing and interpreting our results vis-a-vis studies that considered a single aspect of board composition. Second, board heterogeneity measure, the Blau Index, only takes into account two categories for proportions; for instance, nationality diversity is split just between domestic and foreign directors. Future research could enrich this by including a broader range of nationalities if data permits. Third, the study’s scope is confined to 344 firms on the London Stock Exchange, limited by the carbon emissions data availability from Thomson Reuters ASSET4. Future studies could expand this to include other listed and unlisted firms, should they have access to alternative carbon emissions data sources. Fourth, while this study does consider the impact of external governance on the association between boardroom diversity and carbon emissions, further research could delve into specific monitoring and advisory functions to enhance the understanding of this relationship. Further, future researchers may find it worthwhile to explore the interaction effects of various boardroom diversity measures themselves. Lastly, our sample is drawn from a shareholder-oriented context, which may limit the external validity of our results, particularly outside of Anglo-Saxon contexts. Future studies focusing on a cross-country analyses may yield a deeper insight into the relationship between boardroom diversity and corporate carbon emissions.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Notes

The Paris Agreement set the goals to substantially reduce global greenhouse gas emissions to limit the global temperature increase in this century to 2 °C while pursuing efforts to limit the increase even further to 1.5 °C. A consensus was made to review countries’ commitment every five years and support developing countries to mitigate climate change, strengthen resilience, and enhance abilities to adapt to climate impacts. See, https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/paris-agreement.

Prior studies investigated the board-level characteristics such as independence, women on boards, skilled boards, ESG-based pay (Haque, 2017; Kreuzer & Priberny, 2022; Kyaw et al., 2022), CEO characteristics such as CEO risk-aversion and gender (Homroy, 2023; Hossain et al., 2023), firm-level economic policy uncertainty (Benlemlih & Yavaş, 2023) carbon disclosure level (Qian & Schaltegger, 2017), firm characteristics such as size, market capitalization, profitability, cash holdings, institutional ownership (Alam et al., 2022; Azar et al., 2021; Prado-Lorenzo et al., 2009) as determinants of corporate carbon performance.

We study carbon emissions which is a specific indicator of corporate environmental performance or CSR. This strand of CSR literature is non-trivial, but it is difficult to gauge which aspect of CSR is financially material or value-relevant. Since the capital market is concerned about value-relevant information or material CSR performance, we cannot isolate the truly material aspect of CSR if we use the overall CSR as our variable of interest. Carbon emissions as shown by prior studies such as Bolton and Kacperczyk (2021) involve carbon-related regulator and physical risks that require firms to pay the carbon premium required by shareholders. Thus, our study focuses on such financially material aspects of CSR on which both shareholders and stakeholders have high concerns.

In the existing literature, the role of board diversity is linked with financial performance (Ali et al., 2021; Harjoto et al., 2018; Janahi et al., 2022) or non-financial (or CSR) performance (Beji et al., 2021; de Villiers et al., 2011; Dodd et al., 2022). The latter strand of literature considers the overall CSR performance in general. On the other hand, Hillman (2015) raises important empirical questions regarding the impact of different types of diversity on boardroom decisions and behaviors. These include inquiries about whether various forms of diversity can act as substitutes for each other and whether gender diversity, for instance, offers more benefits compared to other types. Despite the importance of these questions, there is an indication that they have not been comprehensively addressed by previous research, leaving a gap in understanding the full effects of boardroom diversity on corporate governance and performance.

Since our board-level data are less varied over the years, firm fixed effect specification is not relevant to our data but the inclusion of industry-year fixed effects may account for economy wide changes across industries/sectors. For example, carbon and energy-related initiatives are increasingly and frequently being adopted in some sectors more than others to improve carbon and energy use disclosure and performance.

Panel data enables us to incorporate variation in diversity and emissions data across both entities and time periods. As a result, we can account for factors that might impact these variations over time. Additionally, incorporating year effects in panel data helps to separate the time trend affecting board diversity and carbon emissions. Notably, leveraging such data allowed us to utilize lagged independent variables and capture the evolving impact of board diversity on carbon emissions.

The UK carbon reporting regulations require to use the robust and accepted methods for calculating emissions. GHG emissions per revenue amount is the widely use intensity metric, also recommended by GHG Reporting Protocol or Defra Reporting Guidelines.

We thank the reviewer for noticing this case in our early data which persists with updated data.

We found that board independence is highly correlated with directors’ outsidership, we choose to use the latter as the measure of structural diversity. The recent trend in the UK boards also shows a greater emphasis on non-executive directors’ representation that might have empirical implications (Young, 2000).

If a board is homogenous there is a dominant view or ‘group think’ which may reduce board effectiveness. So, the use of percentage or proportion of measures such as female or foreign directors does not reflect the underlying diversity definition, but rather one aspect of board composition. Further, our theoretical framework assumes the importance of directors’ heterogeneity for board effectiveness due to increased board capital in heterogeneous boards.

We also single cluster the standard errors at the firm, industry, and year level and find similar results in general.

The UK CG code 2010 requires FTSE350 (below the FTSE350) firms to have at least half (two) of the board comprised of non-executive directors determined by the board to be independent. The minimum value of zero for NED diversity does not mean that the board has no non-executive directors, but it is the case of fully non-executive directors on the board. Our manual data check further confirms it as sampled firms on average have about 70% non-executive directors which range between 14 and 100%. We thank the reviewer for further encouraging us to check and interpret data.

We thank the reviewer for suggesting us to use the model including comprehensive measures as the main model to interpret and draw conclusions. We use the comprehensive models in the subsequent tests of the study.

The Companies Act 2006 (Strategic Report and Directors Report) Regulations 2013 required all UK-quoted companies to report their annual greenhouse gas emissions in their Directors Report. The part 7 of the Regulations 2013 includes the disclosures concerning greenhouse gas emissions for quoted UK companies by which companies must state ‘tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent’ with at least one ratio expressed in relation to a quantifiable factor associated with the company’s activities. See, the full Regulations 2013 The Companies Act 2006 (Strategic Report and Directors’ Report) Regulations 2013 (legislation.gov.uk).

We use carbon emissions reported to CDP from 2013 to 2021 due to the CDP data availability at Refinitiv Eikon as of Sept. 2023.

This exclusion further rules out the influence of other regulatory pressures such as the EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive 2014, the Paris Agreement 2015, and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2016.

We consider the full sample period in the difference-in-differences model due to a small number of observations. This is due to the discontinuity of many firms (Treat_xx) in the post-period and the growing inclusion of newer firms in the post-period, as evident in the database. However, results are similar if we limit the study period to either a four or six-year window, but the latter specification will include only 234 observations; thus, we opt for a full sample period.

UK Corporate Governance Code 2010 for the first-time stresses on the board diversity. The Code, in its principle of board effectiveness, focuses that ‘the board and its committees should have the appropriate balance of skills, experience, independence, and knowledge of the company to enable them to discharge their respective duties and responsibilities effectively,’ See https://www.thegovernor.org.uk/freedownloads/corporategovernance/UK%20Corporate%20Governance%20Code%20June%202010.pdf.

References

Adams, R. B., de Haan, J., Terjesen, S., & van Ees, H. (2015). Board diversity: Moving the field forward. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 23(2), 77–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12106

Aggarwal, R., Jindal, V., & Seth, R. (2019). Board diversity and firm performance: The role of business group affiliation. International Business Review, 28(6), 101600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2019.101600

Aladwey, L., Elgharbawy, A., & Ganna, M. A. (2022). Attributes of corporate boards and assurance of corporate social responsibility reporting: Evidence from the UK. Corporate Governance: THe International Journal of Business in Society, 22(4), 748–780. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-02-2021-0066

Alam, M. S., Safiullah, M., & Islam, M. S. (2022). Cash-rich firms and carbon emissions. International Review of Financial Analysis, 81, 102106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2022.102106

Ali, F., Wang, M., Jebran, K., & Ali, S. T. (2021). Board diversity and firm efficiency: evidence from China. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 21(4), 587–607. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-10-2019-0312.

Aliani, K. (2023). Does board diversity improve carbon emissions score of best citizen companies? Journal of Cleaner Production, 405, 136854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136854

Al-Qahtani, M., & Elgharbawy, A. (2020). The effect of board diversity on disclosure and management of greenhouse gas information: Evidence from the United Kingdom. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 33(6), 1557–1579. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-08-2019-0247

Arnaboldi, F., Casu, B., Kalotychou, E., & Sarkisyan, A. (2020). The performance effects of board heterogeneity: What works for EU banks? The European Journal of Finance, 26(10), 897–924. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351847X.2018.1479719

Aswani, J., Raghunandan, A., & Rajgopal, S. (2023). Are carbon emissions associated with stock returns?*. Review of Finance. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfad013

Azar, J., Duro, M., Kadach, I., & Ormazabal, G. (2021). The Big Three and corporate carbon emissions around the world. Journal of Financial Economics, 142(2), 674–696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.05.007.

Beji, R., Yousfi, O., Loukil, N., & Omri, A. (2021). Board diversity and corporate social responsibility: Empirical evidence from France. Journal of Business Ethics, 173(1), 133–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04522-4

Ben Selma, M., Yan, W., & Hafsi, T. (2022). Board demographic diversity, institutional context and corporate philanthropic giving. Journal of Management and Governance, 26(1), 99–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-020-09535-9

Benlemlih, M., & Yavaş, Ç. V. (2023). Economic policy uncertainty and climate change: Evidence from CO2 emission. Journal of Business Ethics, 1–27.

Bolton, P., & Kacperczyk, M. (2021). Do investors care about carbon risk? Journal of Financial Economics, 142(2), 517–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.05.008

Carter, D. A., Simkins, B. J., & Simpson, W. G. (2003). Corporate governance, board diversity, and firm value. Financial Review, 38(1), 33–53.

Cui, J., Jo, H., & Na, H. (2018). Does corporate social responsibility affect information asymmetry? Journal of Business Ethics, 148, 549–572.

Cumming, D., & Leung, T. Y. (2021). Board diversity and corporate innovation: Regional demographics and industry context. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 29(3), 277–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12365

de Villiers, C., Naiker, V., & van Staden, C. J. (2011). The effect of board characteristics on firm environmental performance. Journal of Management, 37(6), 1636–1663. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311411506

Dodd, O., Frijns, B., & Garel, A. (2022). Cultural diversity among directors and corporate social responsibility. International Review of Financial Analysis, 83, 102337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2022.102337

Downar, B., Ernstberger, J., Reichelstein, S., Schwenen, S., & Zaklan, A. (2021). The impact of carbon disclosure mandates on emissions and financial operating performance. Review of Accounting Studies, 26(3), 1137–1175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-021-09611-x

Elleuch Lahyani, F. (2022). Corporate board diversity and carbon disclosure: Evidence from France. Accounting Research Journal, 35(6), 721–736. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARJ-12-2021-0350

Fernandes, S. M., Bornia, A. C., & Nakamura, L. R. (2019). The influence of boards of directors on environmental disclosure. Management Decision, 57(9), 2358–2382. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-11-2017-1084

Haque, F. (2017). The effects of board characteristics and sustainable compensation policy on carbon performance of UK firms. The British Accounting Review, 49(3), 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2017.01.001

Harjoto, M. A., Laksmana, I., & Yang, Y.-W. (2018). Board diversity and corporate investment oversight. Journal of Business Research, 90, 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.04.033

Hillman, A. J. (2015). Board diversity: Beginning to unpeel the onion. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 23(2), 104–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12090

Hillman, A. J., & Dalziel, T. (2003). Boards of directors and firm performance: Integrating agency and resource dependence perspectives [Article]. Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 383–396. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2003.10196729

Hillman, A. J., Nicholson, G., & Shropshire, C. (2008). Directors’ multiple identities, identification, and board monitoring and resource provision. Organization Science, 19(3), 441–456. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0355

Hoang, T. C., Abeysekera, I., & Ma, S. (2018). Board diversity and corporate social disclosure: Evidence from Vietnam. Journal of Business Ethics, 151(3), 833–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3260-1

Homroy, S., & Slechten, A. (2019). Do board expertise and networked boards affect environmental performance? Journal of Business Ethics, 158(1), 269–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3769-y

Homroy, S. (2023). GHG emissions and firm performance: The role of CEO gender socialization. Journal of Banking & Finance, 148, 106721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2022.106721.

Hossain, A., Saadi, S., & Amin, A. S. (2023). Does CEO risk-aversion affect carbon emission? Journal of Business Ethics, 182(4), 1171–1198.

Huson, M. R., Parrino, R., & Starks, L. T. (2001). Internal monitoring mechanisms and CEO turnover: A long-term perspective. The Journal of Finance, 56(6), 2265–2297. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00405

Ibrahim, B. M., & Kalaitzoglou, I. A. (2016). Why do carbon prices and price volatility change? Journal of Banking & Finance, 63, 76–94.

Jakučionytė-Skodienė, M., & Liobikienė, G. (2022). The changes in climate change concern, responsibility assumption and impact on climate-friendly behaviour in EU from the Paris Agreement Until 2019. Environmental Management, 69(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-021-01574-8

Janahi, M., Millo, Y., & Voulgaris, G. (2022). Age diversity and the monitoring role of corporate boards: Evidence from banks. Human Relations, 0(0), 00187267221108729. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267221108729

Ji, J., Peng, H., Sun, H., & Xu, H. (2021). Board tenure diversity, culture and firm risk: Cross-country evidence. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 70, 101276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2020.101276

Jiraporn, P., Jiraporn, N., Boeprasert, A., & Chang, K. (2014). Does corporate social responsibility (CSR) improve credit ratings? Evidence from Geographic identification. Financial Management, 43(3), 505–531. https://doi.org/10.1111/fima.12044

John, K., & Senbet, L. W. (1998). Corporate governance and board effectiveness. Journal of Banking & Finance, 22(4), 371–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4266(98)00005-3

Kabir, M. N., Rahman, S., Rahman, M. A., & Anwar, M. (2021). Carbon emissions and default risk: International evidence from firm-level data. Economic Modelling, 103, 105617.

Katmon, N., Mohamad, Z. Z., Norwani, N. M., & Farooque, O. A. (2019). Comprehensive board diversity and quality of corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from an emerging market. Journal of Business Ethics, 157(2), 447–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3672-6

Khan, I., Khan, I., & Senturk, I. (2019). Board diversity and quality of CSR disclosure: Evidence from Pakistan. Corporate Governance: THe International Journal of Business in Society, 19(6), 1187–1203. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-12-2018-0371

Kreuzer, C., & Priberny, C. (2022). To green or not to green: The influence of board characteristics on carbon emissions. Finance Research Letters, 49, 103077.

Kyaw, K., Treepongkaruna, S., & Jiraporn, P. (2022). Board gender diversity and environmental emissions. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(7), 2871–2881. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3052

Kyere, M., & Ausloos, M. (2021). Corporate governance and firms financial performance in the United Kingdom. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 26(2), 1871–1885. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.1883

Li, N., & Wahid, A. S. (2018). Director tenure diversity and board monitoring effectiveness. Contemporary Accounting Research, 35(3), 1363–1394. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12332

Liao, L., Luo, L., & Tang, Q. (2015). Gender diversity, board independence, environmental committee and greenhouse gas disclosure. The British Accounting Review, 47(4), 409–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2014.01.002

Long, T., Dulewicz, V., & Gay, K. (2005). The role of the non-executive director: Findings of an empirical investigation into the differences between listed and unlisted UK boards. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 13(5), 667–679. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2005.00458.x

Mallin, C. A., & Michelon, G. (2011). Board reputation attributes and corporate social performance: An empirical investigation of the US Best Corporate Citizens. Accounting and Business Research, 41(2), 119–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2011.550740

Mardini, G. H., & Elleuch Lahyani, F. (2022). Impact of foreign directors on carbon emissions performance and disclosure: Empirical evidence from France. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 13(1), 221–246. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-09-2020-0323

Michelon, G., Bozzolan, S., & Beretta, S. (2015). Board monitoring and internal control system disclosure in different regulatory environments. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 16(1), 138–164. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAAR-03-2012-0018

Miller, T., & Del Carmen Triana, M. (2009). Demographic diversity in the boardroom: Mediators of the board diversity–firm performance relationship. Journal of Management Studies, 46(5), 755–786. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00839.x

Monasterolo, I., & De Angelis, L. (2020). Blind to carbon risk? An analysis of stock market reaction to the Paris Agreement. Ecological Economics, 170, 106571.

Mura, R. (2007). Firm performance: Do non-executive directors have minds of their own? Evidence from UK panel data. Financial Management, 36(3), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-053X.2007.tb00082.x

Muttakin, M. B., Rana, T., & Mihret, D. G. (2022). Democracy, national culture and greenhouse gas emissions: An international study. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(7), 2978–2991.

Narsa Goud, N. (2022). Corporate governance: Does it matter management of carbon emission performance? An empirical analyses of Indian companies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 379, 134485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134485

Nekhili, M., Chakroun, H., & Chtioui, T. (2018). Women’s leadership and firm performance: Family versus nonfamily firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 153, 291–316.

Nuber, C., & Velte, P. (2021). Board gender diversity and carbon emissions: European evidence on curvilinear relationships and critical mass [https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2727]. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(4), 1958–1992. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2727

van den Oever, K., & Beerens, B. (2021). Does task-related conflict mediate the board gender diversity–organizational performance relationship? European Management Journal, 39(4), 445–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2020.09.008

Oh, W.-Y., Chang, Y. K., & Kim, T.-Y. (2018). Complementary or substitutive effects? Corporate governance mechanisms and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Management, 44(7), 2716–2739. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316653804