Abstract

This paper examines the impact of three culturally endorsed leadership prototypes on bank lending corruption. We bring together studies that approach the corruption of bank lending officers from the perspective of a principal-agent problem and studies from the leadership literature, suggesting leadership as an alternative to contractual solutions to agency problems. We hypothesize, based on these views, that culturally endorsed leadership styles that improve (worsen) the leader-subordinate relationships have a negative (positive) effect on bank lending corruption. Using a sample of around 3,500 firms from 36 countries, we find that the prosocial leadership prototype and the nonautonomous leadership prototype do not matter, whereas the self-serving leadership prototype has a positive and statistically significant effect on bank lending corruption. These findings are robust to the inclusion of various control variables in the regressions, and alternative estimation approaches, including ones that account for endogeneity concerns. Furthermore, we find that the power of bank regulators and the age of the credit information sharing mechanism play a moderating role in the relationship between the self-serving leadership prototype and bank lending corruption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The relationship between the efficient allocation of bank financing and economic growth has been well documented in the literature (Hasan et al., 2009; Levine, 2005). However, it should not be taken as a given under all conditions. For example, bank lending can be subject to corrupted practices, which undermine the primary function of efficient credit allocation (Barth et al., 2009; Beck et al, 2006). This, in turn, has adverse consequences for firm growth (Beck et al., 2005). Furthermore, bank officials who accept bribes pose an important agency problem within the bank, as they are more likely to sacrifice the bank’s interests for personal gains (Jiang et al., 2018). For example, the unethical behaviour of bank lending officers may have adverse effects on customer satisfaction, subsequently leading to lower bank value, enhanced reputational risk, and eroded trust in banking institutions. At the same time, the literature suggests that corruption in lending is associated with poor loan quality, worse earnings performance, and banks that are more likely to get into trouble during a financial crisis (Jiang et al., 2018).

Despite the important implications of bank lending corruption, the investigation of its driving factors has been overlooked in the literature (Zheng et al., 2013) and only a handful of studies exist that can be broadly classified into two groups. The first focuses on the role of regulations, dissemination of information and market factors in driving bank corruption. These studies examine the effect of bank regulatory policies (Beck et al., 2006), information sharing (Barth et al., 2009), media ownership and competition (Houston et al., 2011), and timely loan loss recognition (Akins et al., 2017). The second group of studies pays attention to sociological factors, like national culture (El Ghoul et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2013) and country-level religiosity (Niu et al., 2022).

In the present study, we examine the impact of the culturally endorsed participative leadership prototypes on bank lending corruption. As in past studies, we approach the corruption of bank lending officers from the perspective of a principal-agent problem (Akins et al., 2017; El Ghoul et al., 2016). Building on the idea that leadership is an alternative to contractual solutions to agency problems, we put forward the hypothesis that in cases where the leadership style improves the leader-subordinate relationships and subsequently job satisfaction, the bank credit officers (agents) will be less inclined to accept a monetary reward (i.e. bribe payment) that could put at risk these favourable working conditions and interpersonal relationship with their leader (principal).

In the empirical part of our work, we adopt the conceptual framework of Kong and Volkema (2016) and focus on three leadership prototypes, namely self-serving, prosocial and nonautonomous. Based on the underlying idea discussed above, we expect the first leadership prototype to be positively related and the other two to be negatively related to bank lending corruption. Using a sample of up to 3,553 firms from 36 countries, we find evidence that confirms our expectations for the self-serving leadership protype. However, the prosocial and the nonautonomous leadership prototypes do not have a statistically significant effect on bank lending corruption.

These findings have important managerial implications. Understanding the factors that lead to unethical behavior in organizations is critical, since small changes in these behaviors may result in substantial benefits or costs to organizations (Marquardt et al., 2021). For instance, the literature suggests that because of a slippery slope there is a propensity to accept others’ unethical behavior when ethical erosion occurs gradually over time, and ethical misconduct often goes from one small occurrence to actions with far more serious consequences, (Gino & Bazerman, 2009; Welsh et al., 2015). Our findings show that the culturally endorsed self-serving style of leadership matters for bank lending corruption, and therefore organizations should act appropriately.

We contribute to the literature in various ways. First, we extend the literature on the driving factors of bank lending corruption discussed earlier. Among these studies, the ones most closely related to our work are the ones on national culture by Zheng et al. (2013) and El Ghoul et al. (2016). The culturally endorsed leadership prototypes that we consider reflect the beliefs, observations, and values about effective leaders shared by members of a society (House et al, 2004). In turn, consistent with the institutional theory, such leadership ideals translate into actual leadership actions that are consistent with societal expectations. Hence, while related to national culture, the culturally endorsed leadership styles are at the same time quite distinct, reflecting the extent to which societies endorse a particular leadership style (e.g. charismatic/value-based, team-oriented, participative, etc.). Furthermore, the literature suggests that culture does not have a direct impact on organizational outcomes, and it rather influences them indirectly through the leadership styles (Euwema et al., 2007; House et al., 2014; Stephan & Pathak, 2016).Footnote 1,Footnote 2

Second, we contribute to the cross-country literature on the culturally driven leadership styles. To the best of our knowledge, there exist only two studies that relate to the present work, examining the impact of culturally driven leadership prototypes on corruption (Gutmann & Lucas, 2018; Kong & Volkema, 2016).Footnote 3 Both studies are at the country-level, with the first focusing solely on public sector corruption. However, many scholars highlight that public and private sector corruption are not the same (Gutmann & Lucas, 2018; Park, 2012; Sartor & Beamish, 2020).Footnote 4 Gutmann and Lucas (2018) extend the study of Kong and Volkema (2016) to account for private sector corruption. However, not only their data on corruption are at the country-level, but they also aim to capture aggregate private corruption across business, NGOs, religious bodies, and the media. Therefore, their indicator of private corruption is rather general and, most importantly, it does not include information about bank lending corruption. Furthermore, they draw their data from the Global Corruption Barometer by Transparency International. This is a public opinion survey expressing the perceptions of individuals about corrupt practices in the private sector rather than the ones of firms that had first-hand experience with bank lending corruption.

Third, we contribute to the business ethics literature that examines issues related to leadership and corruption (e.g., Aguiler & Vadera, 2008; Bishara & Schipani, 2009; Huang & Snell, 2003; Lythreatis et al., 2019; Sartor & Beamish, 2020; Wei et al., 2020). With the exception of the studies of Kong and Volkema (2016) and Gutmann and Lucas (2018) that were discussed above, other studies that bring these concepts together are either conceptual in nature (Aguiler & Vadera, 2008; Bishara & Schipani, 2009), or they focus mostly on political leadership and corruption in the public sector (Afridi et al., 2017), or they rely on small-scale surveys for specific countries (Bashir & Hassan, 2020; Collins et al., 2009). Hence, there exists no study on the impact of culturally driven leadership styles on bank lending corruption, even more so with the use of firm-level data. Our study aims to close this gap in the literature.

The rest of the manuscript is as follows. The next section provides a background discussion and outlines our hypotheses. Then we discuss the variables and sample used in our study, followed by the presentation of our findings. The final section concludes the study.

Background Discussion and Hypotheses Development

Bank Lending Corruption as a Principal-Agent Problem and the Role of Leadership

The principal-agent theory appears to have a central role in labour economics, and more specifically in organizational transactions and arrangements between the employee and the employer (Jirjahn, 2006; Miller, 2005; Ross, 1973). Therefore, it is not surprising that it has been used to explain corporate misconduct (Greve et al., 2010; Krawiec, 2005; Zhou et al., 2020), including the corruption of bank lending officers (Akins et al., 2017; El Ghoul et al., 2016). As discussed in Krawiec (2005), the underlying idea in these studies is that organizational misconduct is the result of actions of employees (agents) who disregard the preferences of shareholders and their representatives – i.e. the board of directors and senior management (principals).

As is well known, agency theory has its roots in economic utilitarianism, which asserts that rational individuals will favour alternatives that enhance their own utility (Ross, 1973). In the case of bank lending for example, the agent (lending officer) weighs the benefits from engaging in lending corruption against the costs of being caught and punished by the bank or external parties.

In more detail, because of imperfect information and the use of soft information in the lending process, the loan officer has an opportunity to abuse his discretion over the final terms of the loan in exchange for monetary and/or non-monetary benefits from the applicant, either immediately or in the future (Barth et al., 2009; El Ghoul et al., 2016).Footnote 5

Thus, the most obvious benefit for the loan officer (agent) is the extra income that he will earn by accepting a bribe from the bank customer. However, non-economic factors are also important for employees, and therefore their incentives for misconduct depend not only on financial awards but on additional parameters, like career concerns (Zhou et al., 2020). Should a bank officer engage in misconduct and get caught, he faces a career-related penalty from the principal e.g., the cost of a demotion or an expulsion. Apparently, the weight assigned to such career-related concerns depends on the work environment and job satisfaction of each agent.Footnote 6 In more detail, the benefits that workers derive from a good working environment and job satisfaction can be seen either as an addition to the utility derived from monetary compensation or as reduction in the disutility of work. Therefore, as discussed in Huiras et al. (2000), the more valuable the job to the worker, the less likely the worker is to jeopardize it by engaging in workplace misconduct.

Incentives, monitoring, and cooperation can and do play an important role in the contractual forms that govern transactions with the firms (Miller, 2005), and the leadership style can be instrumental in this regard. Nonetheless, the role of leadership style is an issue that has been neglected in past studies on bank lending corruption. This is surprising, since leadership has been proposed as an alternative to contractual solutions to agency problems (Wallis & Dollery, 1997). In contrast to agency theory which focuses on extrinsic motivation, and more specifically on economic incentives as the main mechanism of control over the agent, the behavioural scholars recognize intrinsic incentives (Cuevas-Rodriguez et al., 2012; Davis et al., 1997). They suggest that the leadership style can influence subordinate behaviour by increasing job satisfaction (An et al., 2020; Asghar & Oino, 2018; Cetin, 2012; Lok & Crawford, 2004) as well as commitment and identification with the organization (Mayer & Schoorman, 1992).

Wallis and Dollery (1997) refer to earlier theoretical work of Casson (1991) and point out that the transformation of principal-agent relationships into leader–follower relationships may mitigate many of the agency problems highlighted by economists. Furthermore, as they discuss, the utility functions of follower will include both material and emotional components. Therefore, should a follower face a material incentive to break the group norm, this person will still comply with it, if the disutility of guild exceeds the utility associated with such material incentives.

Along the same lines, Rotemberg and Saloner (1993) and Jost (2013) discuss the role of leadership style in providing incentives to subordinates. Jost (2013) for example, characterizes as disappointing the fact that most economic theories focus on a contractual relationship between a leader (principal) and his follower (agent) based on monetary incentives, and in so doing they ignore the role of leadership in influencing the agent’s behaviour. Jost (2013) then goes on to propose an economic analysis of leadership styles in a game-theoretic framework, wherein the principal uses his leadership style to influence the agent’s incentives. Cuevas-Rodriguez et al. (2012) also refer to criticisms, pointing out that traditional agency theory analysis by economists does not acknowledge the social context in which the principal–agent contract resides and call for a wider approach that considers behavioural and organizational science of economic exchange between principals and agents.

Hypotheses Development

In our analysis, we initially consider the following six culturally endorsed global leadership dimensions that were identified in the GLOBE project (House & Javidan, 2004): (i) the Charismatic/value-based leadership style, which reflects the “ability to inspire, to motivate, and to expect high performance outcomes from others based on firmly held core values,” (ii) the Team-oriented leadership style, which emphasizes effective team building and implementation of a common purpose or goal among team members,” (iii) the Participative leadership style, which reflects the “degree to which managers involve others in making and implementing decisions,” (iv) the Humane-oriented leadership style, which reflects “supportive and considerate leadership but also includes compassion and generosity,” (v) the Autonomous leadership style, which refers to “independent and individualistic leadership attributes,” (vi) the Self-protective leadership style, which reflects the dimensions of: self-centered, status conscious, conflict inducer, face saver, and procedural.Footnote 7

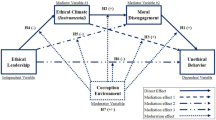

Following Kong and Volkema (2016) and Gutmann and Lucas (2018), we group these six leadership styles of GLOBE into three broad leadership prototypes. The first is the self-serving leadership, that encompasses the self-protective and nonparticipative styles of GLOBE. The second is the prosocial leadership, that focuses on increasing collective welfare and fairness, and encompasses the charismatic/value based, team-oriented, and humane-oriented styles of GLOBE. The third is individualistic leadership prototype, that reflects the autonomous leadership style of GLOBE (Kong & Volkema, 2016).

As discussed in Kong and Volkema (2016) this conceptual grouping of the six leadership styles into the three broad leadership prototypes is based on the underlying social value orientations associated with the leadership prototypes.Footnote 8,Footnote 9 These social value orientations, that reflect the magnitude of the concern people have for others, or else the self-regarding versus other regarding preferences (Bogaert et al., 2008), are predictive of social behavior like altruistic behavior (Van Lange et al., 2007), negotiation behavior (De Dreu & Van Lange, 1995), and cooperative behavior (Balliet et al., 2009; Bogaert et al., 2008), and consequently they have implications for leadership type preferences and leader–follower effects (De Cremer, 2000; Van Dijk & De Cremer, 2006).

In what follows, the underling idea that we put forward is that in cases where the leadership style improves the leader-subordinate relationships and subsequently job satisfaction, the bank credit officers (agents) will be less inclined to forgo these working and interpersonal relationship conditions in exchange for an additional monetary reward that could come in the form of bribe payments. After all, the literature suggests that leadership style and job satisfaction are positively related to the intention to stay with the employer. By engaging in corrupt practices, bank credit officers could put that at risk, should they be discovered.

Our hypothesis is based on earlier work, which points out that nonfinancial recognition serves as the biggest driver of employer experience, as well as that employees with an overall positive experience are eight times more likely to stay and four times more committed than those with a negative experience (Chodyniecka et al., 2022). It also builds upon earlier studies concluding that, contrary to popular theorizing, the pay level is only marginally related to overall job satisfaction, possibly because pay is not as important as other facets such as work satisfaction (Judge & Church, 2000). All in all, our reasoning is consistent with evidence that career stakes and job satisfaction reduce employee deviance and worker misconduct (Huiras et al., 2000; Judge et al., 2010).

Therefore, we expect the self-serving leadership to be positively associated to bank lending corruption. This is because self-serving leaders focus on increasing personal benefits at the expense of collective welfare (Kong & Volkema, 2016), and their autocratic and self-protective decisions and actions are seen as destructive leadership that violates the legitimate interests of the subordinates in the organization (Van de Vliert & Einarsen, 2008).

Also, as mentioned earlier, one of the components of the self-serving leadership prototype is the self-protective leadership style which is characterized by self-centeredness, elitism, status consciousness, narcissism, and a tendency to induce conflict with others (House, 2004). This is close to what Brodbeck et al. (2002) call oppressive leader, whom they describe as: non-participative, micro manager, autocratic, elitist, vindictive, cynical, and hostile. This leader is disliked by followers, partly because of a negative impact on their emotional well-being and partly because the leader is the ultimate representation of low participation (Brodbeck et al., 2002).

Furthermore, many studies suggest that participative leadership results in higher levels of subordinates’ commitment and satisfaction and lower levels of turnover intentions (Allen et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2010; Kim, 2002; Miao et al., 2013; Steyrer et al., 2008; Usman et al., 2021). Stated differently, nonparticipative leadership, which is one of the components of self-serving leadership, leads to lower levels of employees’ organizational commitment and job satisfaction, and enhances deviant behaviors (Mulki et al., 2006).

Finally, Judge et al. (2006) show that narcissistic behavior is also negatively related to leadership ratings by subordinates. All these characteristics contrast with desirable leadership behavior and alienate employees because of reciprocity norms, loosening their ties to the organization (Steyrer et al., 2008), which in turn has implications for the lending officers’ work-related utility function (i.e., the weigh assigned to career stakes versus the monetary benefits) and subsequently for their decision as to whether to engage in corrupt lending or not. Consequently, we formulate our first hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 1: The culturally endorsed self-serving leadership prototype is positively related to bank lending corruption.

Turning to prosocial leadership, we expect it to be negatively associated to bank lending corruption. The literature suggests that all the components of the prosocial leadership prototype (i.e. charismatic/valued-based, team-oriented and humane-oriented leadership) are positively related to the organizational commitment of subordinates (Steyrer et al., 2008). In other words, when subordinates perceive that leaders care about their well-being, then they are inclined to reciprocate by higher levels of organizational commitment.

Others also mention that there exists a positive correlation between charismatic leadership and followers’ performance and satisfaction (Shamir et al., 1993, 1998) as well as between human-oriented leadership and job satisfaction (De Vries et al., 1998). In turn, as mentioned earlier, job satisfaction has implications for workplace misconduct and deviant or counterproductive behaviour (Andreoli & Lefkowitz, 2009; Hollinger, 1986; Huiras et al., 2000; Mangione & Quinn, 1975). Furthermore, the literature suggests that a leader’s charisma can induce individuals to undertake personally costly but socially beneficial actions (Antonakis et al., 2022).

Thus, as in Gutmann and Lucas (2018) we hypothesize that prosocial individuals assign a positive value to outcomes of others and are therefore less likely to tolerate socially harmful actions like corruption. The underlying idea in the context of the present study is that the utility derived from such working conditions outweighs the monetary compensation from corrupt actions, making it less likely for the bank officer to jeopardize it by engaging in corrupt lending. Thus, we formulate our second hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 2: The culturally endorsed prosocial leadership prototype is negatively related to bank lending corruption.

Finally, we expect the individualistic/autonomous (nonautonomous) leadership prototype to be positively (negatively) associated with bank officers’ corrupt practices. There are various reasons for this. For example, the literature suggests that independent, individualistic, unique, and autonomous leader behaviors are inconsistent with the promotion of collective interests (Gelfand et al., 2004). Additionally, autonomous leaders are characterized by a high degree of social distance from subordinates, a tendency to be aloof, and to work alone (House, 2004).

Therefore, it is not surprising that the higher the value attached to humane orientation by organizations the less likely it is for autonomous leadership to be rated as outstanding by the members of that organization (Kabasakal & Bodur, 2004). Furthermore, subordinates who think their leader works for his or her own individual goals report that they are dissatisfied with the leader’s supervision, they feel their leader makes them less willing to work hard and remain in the job, and they are overall dissatisfied with the job (Tjosvold et al., 1983).

Consequently, as in the case of self-serving leadership, we expect that autonomous (nonautonomous) leadership makes it more (less) likely for bank lending officers to engage in corrupt practices to compensate for the forgone utility derived from a good working environment or because their career concerns are not very high. The third hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 3: The culturally endorsed nonautonomous leadership prototype is negatively related to bank lending corruption.

Variables and Sample

Dependent Variable: Bank Lending Corruption

To measure bank lending corruption, consistent with the studies mentioned earlier, we rely on firm-level information from the World Bank’s World Business Environment Survey (WBES). This survey constitutes a large effort by the World Bank Group and partner institutions that was administrated on a roughly parallel basis in around 80 countries. The survey included various questions aiming to provide the basis for comparisons of investment climate, business environment conditions, and constraints affecting enterprises. It was conducted between 1998 and the middle of 2000, through personal interviews of managers from various industries (e.g., manufacturing, service/commerce, agriculture, constructure, other industries). It included at least 100 firms from each country, which resulted in responses from 10,032 firms, mostly SMEs (Batra et al., 2003).Footnote 10

To quantify the level of bank lending corruption, we use the answer to the following question/request of the WBES questionnaire: Please judge on a four point scale how problematic are these different financing issues for the operation and growth of your business: Corruption of bank officials.Footnote 11 Bank lending corruption takes the value of 1 if the answer of the responded is “no obstacle”, the value of 2 if the answer is “minor obstacle”, the value of 3 if the answer is “moderate obstacle”, and the value of 4 if the answer is “major obstacle”. Therefore, higher values are associated with higher perceived bank lending corruption by the managers of the enterprises that were borrowers or perspective borrowers.

Earlier studies discuss that the WBES has several advantages for research on corruption in bank lending. First, Beck et al. (2006) argue that there are good reasons to believe that these self-reported data are not biasing the results in favor of their findings. As they explain, if a firm facing the same obstacles responds to questions differently in different institutional and cultural environments, then, to the extent that this represents pure measurement error, it would bias the results against finding a significant relationship between bank supervision and firm financing obstacles.Footnote 12 We believe that a similar argument can be made in our case concerning the culturally driven leadership styles.

Second, additional work done or cited in Beck et al. (2006), Barth et al. (2009), and Houston et al. (2011) shows that firms’ responses to the survey on financing obstacles are capturing more than idiosyncratic differences in how firms rank obstacles, since they are closely associated with measurable outcomes (see e.g., Hellman et al., 2000; Fan et al., 2009; Beck et al., 2007).

Third, Zheng et al. (2013) and El Ghoul et al. (2016) highlight that: (i) the WBES contains a large proportion of small and medium enterprises, which alleviates the sample bias problems encountered in many cross-country studies on access to finance, and (ii) the WBES provides information on various firm characteristics allowing one to control for firm heterogeneity.

Finally, asking borrowing firms, as opposed to banks, about their perception of lending corruption results in less bias in the responses (Akins et al., 2017).

Independent Variable: Culturally Endorsed Leadership Prototypes

In addition to identifying the six global CLTs, House et al. (2004) also provide country-specific scores which reflect a country’s expectations from the leaders in the society and can be used in empirical research. Examples of other studies that use the leadership styles of GLOBE in their empirical analysis, albeit in different contexts (e.g., Government fiscal transparency, innovative entrepreneurship, corporate social responsibility, etc.), are the ones of Waldman et al. (2006), Van Hemmen et al. (2015), Rossberger and Krause (2015), Mensah and Qi (2016), Stephan and Pathak (2016).

As discussed earlier, we adopt the framework of Kong and Volkema (2016), who propose the grouping of the six dimensions of GLOBE into three leadership prototypes.Footnote 13 In addition to their conceptual discussion, Kong and Volkema (2016) provide further support to their reasoning with the use of factor analysis. In unreported estimations, we confirm their results. In more detail, using factor analysis with varimax rotation (a common data-driven technique in composite indicator construction, see Greco et al., 2019), we extract three factors that are similar to the ones in Kong and Volkema (2016). The first factor regards cultural endorsement of charismatic/value-based (rotated factor loading score of 0.99), team-oriented (0.74) and humane-oriented (0.49) leadership. The second factor regards cultural endorsement of self-protective (0.99) and participative (− 0.68) leadership, whilst the third regards cultural endorsement of autonomous (− 0.92) leadership. To follow the notation used in Kong and Volkema (2016) we name the first two factors prosocial leadership prototype and self-serving leadership prototype, respectively. To avoid changing the sign of the third factor, we name this nonautonomous leadership prototype.

Control Variables

In this section, we present various firm and country-specific variables that we use in the baseline specification. Additional variables used in subsequent analysis are also discussed when we introduce them in the specifications, with further information about all the variables being available in the Online Appendix (Section I).

Earlier studies suggest that the bargaining power of corrupted loan officers in negotiations for bank lending might be associated with the ownership structure of the borrowing firms (Barth et al., 2009; Beck et al., 2006; El Ghoul et al., 2016). Therefore, we include two dummy variables that identify a firm’s ownership type. Government is a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if government owns any percentage of the firm and the value of 0 otherwise. We use a similar variable for foreign ownership. Apparently, the omitted group is private firms without any government or foreign ownership.

The literature also provides some evidence that firms that export are less like to perceive bank corruption as a major obstacle to their business (Barth et al., 2009; Beck et al., 2006; Zheng et al., 2013). One potential explanation is that they have greater access to external financing and therefore more bargaining power during lending negotiations (Barth et al., 2009). Therefore, we use a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the firm exports, and the value of 0 otherwise.

Additionally, as discussed in El Ghoul et al. (2016), corrupt loan officers are more likely to have the upper hand in the case of firms with more competitors. While some research shows that the number of competitors does not matter (Beck et al., 2005; Houston et al., 2011), others show a positive and statistically significant association between the number of competitors and bank corruption in some of their specifications (El Ghoul et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2013). Consistent with these studies we include in the regressions the number of competitors identified by the firm manager, using the answer to the following WBES question “Regarding your firm’s major product line, how many competitors do you face in your market?”.

In all our regressions, we also control for size (e.g. Barth et al., 2009; Beck et al., 2005). As mentioned in El Ghoul et al. (2016), small firm size may result in higher perceived level of bank corruption because of greater information opaqueness and limited bargaining power. We make use of the WBES’s classification of firms into large, medium, and small, and we introduce two dummy variables denoting large-sized firms (large firms = 1, Other firms = 0), and medium-sized firms (medium firms = 1, other firms = 0). The small firms form the omitted category.Footnote 14

Finally, consistent with earlier studies, we capture potential differences across industrial sectors with the use of dummy variables (Barth et al., 2009). Therefore, we include industry dummies for Service, Agriculture, Construction, Other firms, with Manufacturing being the omitted category.

We also control for key macroeconomic conditions using GDP growth, and the 5-years standard deviation of inflation, as Beck et al. (2005) mention that firms in faster growing countries, and with a more stable monetary environment may face lower obstacles. In further analysis we enhance our specification to include an array of additional firm-level and country-level control variables.

Finally, to mitigate concerns – to the extent this is possible – about other omitted variables, all our regressions include regional dummy variables for the following geographical regions, based on the World Bank classification: Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, North America, South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, East Asia and the Pacific (omitted category).Footnote 15 These dummies account for conditions that are common between neighboring countries and within geographical regions and have not been adequately captured by other control variables used in our specifications.

Sample

As mentioned already, the two main sources of information are the WBES and the GLOBE project. Data for the macroeconomic conditions are from the World Development Indicators of the World Bank.

To test our hypothesis, we start with the full sample of 10,032 firm observations included in WBES. Initially, we exclude 1,957 firms with no information about bank officials’ corruption, leaving us with 8,075 firms from 81 countries.Footnote 16 Then, we omit another 4,522 firms from countries with no information about the leadership indicator, as well as observations with missing values about the firm-level and country-level variables used in the baseline specification. In what is apparently reduced further when we include additional control variables in the regressions, merging the information from all the sources results in a working sample of 3,553 firms from 36 countries that we use in the baseline estimations.Footnote 17

Tables 1 and 2 present descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients for both the variables used in the main results as well as in subsequent analysis. About 10.53% of the firms in our baseline sample report bank corruption as a major obstacle, 9.37% respond that bank corruption is a moderate obstacle, 18.44% rate corruption as a minor obstacle, while 61.67% respond that the corruption of bank officials is not an obstacle to firm growth.Footnote 18

Empirical Results

Baseline Regressions

Following earlier studies, because of the ordered nature of the dependent variable, we estimate an ordered probit model. In all the cases, the errors are clustered at the country-level. Column 1 of Table 3 shows the baseline results while controlling for the firm-specific characteristics and macroeconomic conditions outlined before. In contrast to the prosocial and nonautonomous leadership prototypes that do not appear to matter, the results show that the coefficient of the culturally endorsed self-serving leadership prototype is positive and statistically significant.

Therefore, bank lending corruption appears to be a higher obstacle for the operation and growth of firms from countries with higher values of culturally endorsed self-serving leadership. Attributes like secretive, self-centered, intragroup competitor, asocial leader that are part of self-serving leadership, as well as lack of attributes like bossy, elitist, micromanager, nonegalitarian that are part of a nonparticipative style, are associated with higher bank lending corruption.

In column 2 we control for several firm-specific characteristics. First, we include a dummy variable that indicates whether (or not) the firm provides its shareholders with financial statements that have been reviewed by an external auditor. Better firm financial disclosures should improve the quality of the disseminated information and the information asymmetry gap between banks and firms, subsequently leading to lower corruption (Barth et al., 2009).

Second, following Beck et al. (2006) and Barth et al. (2009), we perform a test for the respondents’ pessimism and idiosyncratic firm responses, by including in the regression an additional control variable, based on the firm’s response to the following question/request: ‘Please judge on a four-point scale how problematic are the following factors for the operation and growth of the business: financing”. As in the case of the bank lending corruption, the answer to this question takes values from 1 (no obstacle) to 4 (major obstacle). Beck et al. (2006) mention that to the extent that a particular firm is simply blaming others for its problems, this should be reflected in both its response to this general obstacle question as well as in its response about bank loan officers’ corruption. Therefore, the inclusion of this variable in the regressions lowers the likelihood that idiosyncratic firm responses are biasing the results, and it strengthens the interpretation of an independent relationship between our leadership indicators and the degree to which the corruption of bank officials in an obstacle to obtaining financing.

Third, we use a variable that captures the perceptions of the firm about the corruption of public officials. In more detail, we consider the answer to the following question/request: “Please judge on a four point scale how problematic are the following factors for the operation and growth of your business: corruption”.Footnote 19,Footnote 20 Our approach is consistent with that of Zheng et al. (2013), who also use this variable in further analysis. The rationale is the same as with the inclusion of the general financing obstacle; however, we consider this to be a stronger test due to conceptual relationship with our dependent variable, and the potential spillover effects of general corruption to bank lending corruption. As discussed in Houston et al. (2011), controlling for overall corruption in the economy strengthens the interpretation of an independent relationship between the key variable of interest (in our case leadership prototypes) and corruption in bank lending.Footnote 21

It is possible that a multinational firm that deals with banks around the world will perceive bank lending corruption and be influenced by it in a different way. For example, such firms may have more bargaining power vis-à-vis corrupted bank credit officers in their home country in case that they can finance their operations from banks in other countries where they do business. Hence, we include a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 in the case of firms that have holdings or operations in other countries, and the value of 0 otherwise.

In a similar vein, both the leadership stye and corruption in bank lending may differ between foreign and domestic banks. While we do not have information as for the specific banks that the responding firm is doing business with, WBES includes information about the percentage of the firm’s financing over the last year coming from foreign banks. Therefore, we include this as an additional control variable in the regression.

In all the cases above, we continue to find that the culturally endorsed self-serving leadership prototype is positively associated with bank lending corruption, whereas the other two main variables of interest are insignificant, leading to the conclusion that inclusion of these control variables in the regression does not alter our main results.

Controlling for Additional Country-Specific Characteristics

In this section we account for additional country-specific characteristics. As shown in Columns 1 to 5 of Table 4, our main findings are robust to the inclusion of all these variables in the analysis. All these regressions include the control variables of the baseline specification (Column 1, Table 3), which are not shown to conserve space.Footnote 22

In Column 1 (Table 4), we control for characteristics of the banking sector. First, given the findings of Barth et al. (2009), we control for bank concentration using the percentage of assets held by the five largest banks in the country. Second, as in Barth et al. (2009), we control for bank ownership at the industry level using the percentage of assets held by foreign-owned and government-owned banks, with the rationale in our choice being that different types of ownership may influence the incentives and the ability of the bank lending officers to engage in corrupted practices. Additionally, as mentioned earlier, the leadership style of foreign banks may be different from the one of domestic banks. Fourth, we control for overall banking sector development using the credit by banks to the private sector as a share of GDP (Barth et al., 2009; Beck et al., 2005).

In Column 2 (Table 4), following Beck et al. (2006), we control for the bank regulatory environment with the use of two indicators. The first is the supervisory power index that reveals the extent to which the supervisory authorities have the authority to take specific actions to prevent and correct problems. The second is the private monitoring index that reveals the extent to which market participants have the incentives and the ability to monitor banks, with higher values indicating more private monitoring.

In Column 3 (Table 4), we account for other sociological factors, namely the national culture of collectivism (El Ghoul et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2013) and religiosity (Niu et al., 2022). Following Zheng et al. (2013) we construct an indicator for the national culture of collectivism that is equal to 100 minus Hofstede’s individualism index. We proxy for nonreligiosity with the share of nonreligious people in each country.

In Column 4 (Table 4), we account for creditor rights, and institutions and political stability (see e.g., Houston et al., 2011). In more detail, we include an overall indicator from the international country risk guide (ICRG) that reflects the degree of political stability and institutional development, taking into account various aspects like control of corruption in the political system, strength and impartiality of the legal system, democratic accountability, bureaucratic quality, etc. The idea is that these aspects of the institutional environment may provide additional mechanisms to impose restrictions on bank lending corruption. Additionally, following Barth et al. (2009), we include the creditor rights index of Djankov et al. (2007). This index ranges from 0 to 4 with higher (lower) figures denoting stronger (weaker) creditor rights.

In Column 5 (Table 4), we account for the dissemination of information. Following Akins et al. (2017) we estimate the ratio of loan loss reserves to the next year’s nonperforming loans that serves as an indicator of timely loan loss recognition.Footnote 23 Furthermore, to account for the maturity of credit information sharing in the market (Barth et al., 2009; Houston et al., 2011; Zheng et al., 2013), we include the years since the establishment of either a public registry or a private bureau.

Finally, as in Houston et al. (2011) we account for the role of the media. We control for concentration in the ownership of the media, using the aggregate market share of the three largest daily newspapers and the aggregate market share of the three largest television stations. Additionally, we use factor analysis to create an overall indicator of state ownership of the media, by taking the first principal component of the following three variables: (i) market share of state-owned newspapers out of the aggregate market share of the five largest daily newspapers (by circulation), (ii) market share of state-owned television stations out of the aggregate market share of the five largest television stations (by viewership), (iii) a dummy equal to one if the top radio station is state owned, and zero otherwise. All the media-related data are from Djankov et al. (2003).

Economic Significance

As in past studies, the magnitude of the coefficient of the variable of interest that is statistically significant (e.g., self-serving leadership prototype) varies across our specifications.Footnote 24 Despite having correct signs and statistical significance, the coefficients of the ordered probit model cannot be interpreted in a similar way to the linear models regarding their economic significance.

Following earlier studies (Barth et al., 2009; Niu et al., 2022; Zheng et al., 2013), in Panel B of Tables 3 and 4 we present the economic magnitude of the impact of the self-serving leadership prototype—that is statistically significant- on the probability that corruption in bank lending is perceived as an obstacle to firm growth. We compute the change in the probability that a firm will report corruption in bank lending to be no obstacle, a minor obstacle, a moderate obstacle or a major obstacle due to a change in the variable of interest for an average firm.

For example, the estimates in Column 1 of Table 3 suggest that a one-standard-deviation increase in the score of the self-serving leadership prototype would lead to a 5.4 percentage point increase in the probability that a firm rates bank corruption as a major obstacle and a 13.3 percentage point decrease in the probability that a firm rates bank corruption as no obstacle to firm growth. The effects are quite substantial given that about 11% of the firms in the baseline sample report that corruption in lending is a major obstacle to their growth and about 62% of the firms say that bank corruption is not an obstacle for growth.

As mentioned earlier, the coefficients of the model vary across the specifications, and so do the computed marginal effects. However, even in the case of the specification in Column 2 of Table 3 where we have the lowest values for the marginal effects, the magnitude of the economic impact is quite large. In this case a one-standard-deviation increase in the score of the self-serving leadership prototype would lead to a 2.4 percentage point increase in the probability that a firm rates bank corruption as a major obstacle and a 7.1 percentage point decrease in the probability that a firm rates bank corruption as no obstacle to firm growth.

Using Alternative Estimation Approaches

In this section we resort on different estimations from a methodological point of view. Given the distribution of the responses about corruption, we follow earlier studies (Akins et al., 2017; Barth et al., 2009; Beck et al., 2006; Zheng et al., 2013) and provide further analysis while dividing the responses into two groups. In more detail, we merge the respondents that answered that corruption is either a major obstacle or a moderate obstacle or a minor obstacle into a single group. Hence, this group, to which we assign the value of 1, includes 38.33% of the respondents that responded that corruption poses an obstacle of any magnitude. We assign the value of 0 to the remaining respondents that answered that corruption is not an obstacle. As discussed in Beck et al. (2006) this allows us to use a comparatively balanced distribution of responses, reduce the possible influence of outliers, and use instrumental variable procedures.

First, we present the results of a Probit model with this binary dependent variable in Column 1 of Table 5. Our main findings hold. Our proxy for the self-serving leadership style continues to enter the Probit regression with a positive and statistically significant coefficient, while the other two leadership styles remain insignificant.

Second, we attempt to tackle potential endogeneity issues. In general, past studies discuss two main concerns related to endogeneity.Footnote 25 The first is reverse causality. However, as discussed in these studies, it seems unlikely that an individual firm’s views about corruption in lending will influence country-level attributes (Barth et al., 2009; Beck et al., 2006; Houston et al., 2011). This is even less of a concern in our case. Being culturally driven, the leadership prototypes that we consider should change very slowly over time, similarly to the case with national culture (Hofstede et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2013). Hence, we do not believe that the perceptions of individual firms about the corrupt lending activities in each bank will collectively influence the culturally endorsed leadership prototype at the country level.

The second concern emergers from omitted variables. To tackle this issue, we have already presented various specifications controlling for numerous firm-specific and country-specific aspects suggested in past studies.

At this stage, we re-estimate the specification of Column 1 (Table 5) with the use of IV Probit (e.g., Akins et al., 2017; Beck et al., 2006). Given that we have three main independent variables we select four instruments that we expect to correlate with the first stage dependent variables, but not with the second stage error term. These instruments are: (i) the agricultural intensity in the pre-industrial era, estimated as in Lonati (2020), (ii) the predicted genetic diversity by Ashraf and Galor (2013), (iii) the physical climate, proxied by the percentage of land in tropics and subtropics, (iv) the historical prevalence of infectious diseases/pathogens in a particular country, by Murray and Schaller (2010). The rationale for the selection of these instruments is given in the Online Appendix (section IV). We do not claim that these variables are the only or best instruments. However, they are theoretically justified and at the same time they pass the tests for their use as instruments.Footnote 26

The instrumented self-serving leadership prototype enters the regression with a positive and statistically significant coefficient. The other two leadership prototypes continue to be insignificant. While the instrumentation does not change our main findings, it increases the magnitude of the coefficients of interest. However, it is worth noting that the sample in the case of the IV Probit in Column 2 is reduced by around 4% compared to the estimates in Column 1, due to data availability for the four instruments. To ensure that the change in the coefficients is not due to this change in the sample, in unreported estimations we re-estimate the Probit regression of Column 1 while restricting the sample to the observations used in Column 2. We continue finding that the coefficients of the IV Probit regression are higher in magnitude.Footnote 27 However, this is a common finding in the finance literature (Barth et al., 2009; Jiang, 2017), including earlier studies on bank lending corruption.Footnote 28

As a final robustness test, we estimate an ordered probit regression with endogenous covariates. We use the same instruments as in the case of the IV probit; however, we now model all four possible outcomes as for the perceived magnitude of bank lending corruption. The estimates in column 3 of Table 5 show that our findings hold.

Interaction Effects

As mentioned earlier, it is expected that the lending officer weighs the benefits from engaging in lending corruption against the costs of being caught and punished by the bank or external parties.

Therefore, external monitoring may play a moderating role in the relationship between self-serving leadership style and bank corruption.

Zhou et al. (2020) for example, mention that insider misconduct is an equilibrium outcome determined by the interplay among employees, firms and regulators. Employees have private information on their types and behavior, which are unknown to the firm. This gives employees incentives for misconduct, i.e., to behave differently from what is promised. Nonetheless, the misconduct may expose the firm and its directors to penalties which puts more monitoring pressure on them.Footnote 29 In turn, to the extent the directors and firms can be held accountable, they may enhance monitoring and impose larger penalties to lending officers that engage in corrupt practices. This changes the incentives and utility function of the bank lending officers, and it may have a moderating effect on the relationship between leadership style and lending corruption.Footnote 30

Enhanced transparency also reduces the incentives for corruption and produces more “sunshine” on banking practices (Houston et al., 2011). As discussed earlier, the literature suggests that there are various mechanisms that can enhance transparency, like for example media ownership and competition (Houston et al., 2011), bank regulations that relate to corporate disclosures (Beck et al., 2006), and information sharing via credit bureaus/registries (Barth et al., 2009). For example, media firms have strong incentives to reach a larger audience by reporting interesting news (Houston et al., 2011). The firm’s monitoring by the media substantially increases its reputational cost and legal liability.Footnote 31 In turn, the higher the reputation cost and legal liability for the firm, the higher the expected career penalty for the bank employees. Thus, from the perspective of bank credit officers, media monitoring increases the probability of being detected and punished, and consequently deters potential corruption activities (Houston et al., 2011). However, as discussed in Houston et al. (2011), the monitoring incentives of the media might be lower in countries with a concentrated and state-controlled media sector because the marginal returns of monitoring are lower while the marginal costs are higher due to political pressure and capture.

Along the same lines, regulatory and supervisory policies that encourage the private monitoring of banks, like for example enhanced corporate disclosures and regulations that make bank directors and officials legally liable for the accuracy of information disclosed to the public, can also change the incentives of both bank lending officers and bank leaders, and hence play a moderating role in the relationship between leadership style and bank lending corruption.

Finally, Miller (2005) discusses that one of the primary reasons for which the principal delegates authority to an agent is that the latter has an advantage in terms of expertise or information, going on to argue that this informational advantage, or information asymmetry, poses a problem for the principal, raising concerns as for whether the agent acts in the principal’s best interests. For example, as mentioned earlier, in the case of bank lending the use of soft information and imperfect information provide an opportunity to the lending officer to exercise discretion and, at the same time, also limit the ability of the principal to monitor the lending process. As shown in Barth et al. (2009) information sharing via credit bureaus/registries can reduce bank lending corruption. One possible explanation is that they alter the incentives and utility of bank lending officers, as in the presence of information about the credit quality of borrowers it becomes easier for leaders to monitor the decisions of agents and impose penalties in the case of misconduct.

To explore these issues, we resort to the use of interaction terms as in Beck et al. (2006), Houston et al. (2011), Akins et al. (2017), Niu et al. (2022). Therefore, we interact the self-serving leadership style with each one of the following variables: (i) Supervisory power, (ii) Regulations that enhance the private monitoring of banks, (iii) Maturity of credit information sharing, (iv) Media state ownership, (v) Press concentration, (vi) TV concentration. We include these interaction terms one-by-one in the baseline specification (column 1, Table 3), while holding other things constant. We do not report all the estimates to conserve space, as most of the interactions turn out to be insignificant. In Table 6 we present the estimates for the two interactions that are statistically significant.

First, we find that the interaction term of self-serving leadership style with supervisory power is negative and statistically significant (at the 10% level). Therefore, in countries with higher supervisory power, the magnitude of the effect of self-serving leadership style on bank lending corruption becomes lower. While this appears to be contradictory to the findings of Beck et al. (2006), it is consistent with studies suggesting that regulatory monitoring and enforcement actions enhance managerial discipline in banks and correct weaknesses that bank management can control (Curry et al., 1999; Palvia, 2011).

Second, the interaction of self-serving leadership prototype with the maturity of credit information sharing is negative and statistically significant. Therefore, the more years that a country has either a public registry or private bureau, the lower is the effect of self-serving leadership style on bank lending corruption. This result is partially consistent with the findings of Barth et al. (2009), as it confirms that the age of the credit information sharing mechanisms may enhance the dissemination of information in the market and mitigate the extent of bank lending corruption.

Conclusions

Corruption has received a lot of attention in the business ethics literature. While early studies focus on public sector corruption, more recent ones investigate corporate corruption. Still there is limited research on bank corruption, as well as on leadership styles and corruption. The present study aims to close this gap.

Using a cross-country sample from around 35 countries and the responses of over 3,500 firms, we provide evidence that a culturally driven self-serving leadership style has a positive and statistically significant association with bank lending corruption. In contrast, we find no evidence to suggest that the culturally endorsed prosocial and nonautonomous leadership prototypes impact bank lending corruption. The results hold when we control for various firm- and country-level characteristics, also remaining robust to the use of alternative estimation approaches and the use of instruments to address endogeneity concerns. We also examine whether and how various country-specific characteristics moderate the relationship between the self-serving leadership style and bank lending corruption. In most cases we find that these characteristics do not play a moderating role, the only exceptions being supervisory power and the age of the credit information sharing mechanism.

One of the implications for practice is that a self-serving leadership style possibly results in inferior working behavior of loan offices, with adverse implications for bank corruption. Thus, bank leaders may try to adopt leadership styles that are consistent with a participative and nonself-centered style, like providing subordinates with more autonomy and responsibility in making decisions, being open to their opinions and suggestions, and showing respect and concern when interacting with them. As our measure of corruption is related to the perceptions of the bank customers, this will have further implications not only for the efficient allocation of credit, but for customer satisfaction and loyalty as well.

Our paper is not free of limitations. First, while having certain advantages and being used in all past studies, the measure of bank lending corruption in the WBES database captures the perceptions of the borrowing (or perspective borrowing) firm. There is no doubt that having information as for the exact kind and cost of bank lending corruption for the firms could enhance our understanding. This could, for example, include indicators like the premium charged as additional interest rate, the amount of bribes paid to bank lending officers as percentage of the loan, etc. Finding such data is a very difficult task; however, we hope that future research will improve upon this.

Second, consistent with earlier studies in the field, we assumed that bank lending corruption originates at the level of the credit officer. Should more detailed data become available, it would be interesting to examine whether high ranked bank officers abuse their power being directly involved in bank lending corruption. Having acknowledged this drawback, we believe that this is not a major concern in our setting. Most of the firms in our sample are small and medium enterprises that may not have direct access to the top bank officials. This provides some assurance while approaching bank lending corruption as a phenomenon associated with the actions of lending officers, a view that is consistent with the one in all previous studies in the field.

Finally, if one could identify specific multinational banks that engage in corrupted practices, it would be interesting to examine whether such actions are influenced by the culturally endorsed leadership style in the host country or the one in the country of origin. Unfortunately, such data are not currently available, and we hope that future research will improve upon that.

Notes

Stephan and Pathak (2016) argue that national culture is an extremely broad and general concept, thus culturally endorsed leadership styles may be the channel through which the more general, distal, cultural values influence enterprises. Furthermore, House et al. (2014) provide evidence that cultural values do not directly predict leadership behavior. In contrast, they drive the cultural expectations that in turn drive CEOs’ leadership behavior and effectiveness, due to the desire of the leaders to achieve fit. Finally, Euwema et al. (2007) find that there is no direct relationship between the national culture dimensions of power distance and individualism and the group organizational citizenship behavior (GOCB); however, directive (supportive) leadership has a negative (positive) relationship with GOCB.

Supplementary estimations in the Online Appendix provide support to these views. When we ignore the leadership prototypes, we find that the culture of collectivism has a positive and statistically significant impact on bank lending corruption, which is consistent with Zheng et al. (2013) and El Ghoul et al. (2016). However, the inclusion of the leadership styles in the regressions weakens the effect of collectivism on bank lending corruption.

Other studies on culturally driven leadership styles focus primarily on entrepreneurship and innovativeness, examining issues like innovative entrepreneurship (Van Hemmen et al., 2015), national innovativeness (Rossberger and Krause, 2015) and the likelihood that an individual will become entrepreneur (Stephan and Pathak, 2016) or social entrepreneur (Muralidharan and Pathak, 2019).

In spite of the important insights from prior research on government corruption, business ethicists argue in favor of broadening the corruption-based research and they challenge scholars to incorporate private sector corruption in their work (Sartor and Beamish, 2020). However, to date, private sector corruption remains under-researched in the literature (Sotola and Pillay, 2020).

Levin and Satarov (2000) refer to the case of bank lending in Russia where borrowers had envelopes or even briefcases filled with cash in order to gain access to bank finance. In addition to approving a loan or offering better terms, the loan officers may have incentives to hide a deteriorating borrower’s condition because of personal relationship with the borrower or a future employment from the borrowing firm (Akins et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2013).

For example, many studies show that job satisfaction is an important determinant of employee turnover intention Arnold and Feldman, 1982; Lambert et al., 2001; Weaver et al., 2007). More importantly, the literature suggests that while pay satisfaction affects turnover intent, job satisfaction may be a more crucial variable in terms of employees' turnover (Singh and Loncar, 2010). While the present study does not deal with turnover intention, these findings show that employees that are not satisfied with their job would have no problem to leave their current employer, and hence they should have fewer career concerns and the cost of a demotion or an expulsion.

Section II of the Online Appendix provides detailed information about the construction and meaning of the culturally endorsed leadership styles of the GLOBE project.

Kong and Volkema (2016) confirm empirically the grouping of the six leadership styles into the three prototypes with the use of factor analysis. Later in this study, we too confirm this finding.

Van de Vliert and Einarsen (2008) provide further support to this grouping, by outlying similarities and differences across the leadership styles, in terms of their degree of subordinate orientation and leader direction. Stephan and Pathak (2016) propose a slightly different grouping. They group together self-protective, autonomous, nonparticipative, which as they argue broadly reflects inward, self-focused leadership. Subsequently, charismatic, team-oriented, humane-oriented form another group that reflects outward-focused leadership. Finally, the literature suggests that leadership styles falling within these prototypes/grouping have further similarities. For example, both charismatic and human-oriented leadership are primarily communicative (De Vries et al., 2010). Overall, the grouping of Kong and Volkema (2016) is also consistent with the idea that prosocials exhibit greater cooperation than individualists and competitors (De Dreu and Van Lange, 1995).

SMEs represent approximately 80% in the sample with an almost equal proportion of small enterprises (50 or fewer employees) and medium enterprises (51–500 employees). The remaining 20% (approximately) are large firms (501 or more employees).

This is question 29 in section “VI. Financial Sector and corporate governance” of the WBES questionnaire used in this particular version of the survey. In its general form the question/request concerning the financing issues is as follows: Please judge on a four-point scale how problematic are these different financing issues for the operation and growth of your business (Please do not select more than 4 as “major obstacles” (4)): [X]. In addition to the corruption of bank officials, the list of [X] includes another 10 potential problems like, “Access to specialized export finance,” “Access to lease finance for equipment,” “Banks lack money to lend,” etc. In each case, respondents could answer no obstacle (1), minor obstacle (2), moderate obstacle (3), and major obstacle (4).

In addition to the fact that the conceptual framework of Kong and Volkema (2016) fits our purpose, there is one more reason that led our decision to follow their work and use factor analysis. Some of the original GLOBE leadership styles are moderately to highly correlated. For example, the correlation between Charismatic/Value based leadership style and Team oriented leadership style is 0.7555, and the one between the Participative and Self-protective leadership styles is − 0.7080. Other dimensions have slightly lower, but moderate, correlations. Hence, introducing all 6 individual dimensions in the analysis could raise concerns about multicollinearity. At the same time, introducing them one-by-one in the regressions could raise concerns about omitted variables.

The classification of the firms in these three size-related groups is readily available in the WBES dataset. Small firms are enterprises with 50 or fewer employees, medium enterprises have between 51–500 employees, and large firms have over 500 employees. Unfortunately, the dataset does not include information on the exact number of employees of each enterprise, and hence it is not possible to use another grouping. In a robustness test, we use the natural logarithm of the value of sales in USD. The main results remain the same.

The World Bank regional classification identifies one more group, with countries coming from Middle East & North Africa. However, there are no observations from this region in our sample. The distribution of the firms in the sample across the regions is as follows: Europe & Central Asia = 52%, Latin America & Caribbean = 18%, East Asia & Pacific = 14%, Sub-Saharan Africa = 9%, South Asia = 5%, and North America = 2%.

It should be noted at this point that this question was included only in one past version of the WBES and was discontinued thereafter. As mentioned earlier, the survey for this version of the WBES was carried out from the end of 1998 to the middle- 2000, and therefore our analysis is restricted to this period. Our approach is consistent with existing studies on bank corruption, all of them using the same dataset from the WBES. Additionally, in our case this is not a major concern as the period coincides with the survey of the GLOBE project which as mentioned earlier was conducted over the period 1994–1997. Moreover, this makes the information about leadership being lagged by construction in the regressions, and hence alleviates potential concerns about reverse causality.

Our sample is comparable to the one used in past studies both in terms of firms’ and countries’ coverage. Beck et al. (2006) use a sample of 2,510 firms from 37 countries; Barth et al. (2009) use 4,214 firms from 56 countries; Houston et al. (2011) use 5,331 firms from 59 countries; Zheng et al. (2013) use 3,835 firms from 38 countries; El Ghoul et al. (2016) use 3,834 firms from 38 countries.

This distribution is comparable to the one of previous studies. For example, the corresponding figures in Beck et al. (2006) are: 7.7% (major obstacle), 7.8% (moderate obstacle), 19.5% (minor obstacle), and 65% (no obstacle).

Both in the case of “Financing” and “Corruption” this is question 38 in section “VIII. Summary sections” of the WBES questionnaire used in this particular version of the survey. In its general form this question/request is as follows: Please judge on a four-point scale how problematic are the following factors for the operation and growth of your business. (Please do not select more than 3 obstacles as “major” (4)) and please circle the single most important obstacle): [X]. In addition to “financing” and “corruption,” the list of [X] includes additional potential problems like: “Infrastructure,” “Taxes and Regulations,” “Policy instability/uncertainty,” etc. In each case, respondents could answer no obstacle (1), minor obstacle (2), moderate obstacle (3), and major obstacle (4).

The general corruption indicator refers to corruption of government officials. For example, in their discussion of the WBES survey that we use, Batra et al. (2003) provide statistics by region for the following indicators of corruption “Irregular additional payments made to government officials “to get things done,” “Advance knowledge of amount of additional payment,” “Service delivered as agreed if additional payment made,” “If payment made to one official, another govt official will request payment for same service,” and “If government official acts against rules, can go to superior and get correct treatment without recourse to unofficial payment”. In relation to this, the questionnaire also includes the following question in relation to irregular “additional payments”. Do firms like yours typically need to make extra, unofficial payments to public officials for any of the following? (i) to get connected to public services, (ii) to get licenses and permits, (iii) to deal with taxes and tax collection, (iv) to gain government contracts, (v) when dealing with customs/imports, and (vi) when dealing with courts.

Although, as we mention in the text and the previous footnote, the general corruption indicator captures the corruption of the government officials, one may worry about the discriminant validity of the two indicators. We believe that the inclusion of this general corruption indicator in the regressions could only understate the significance of the bank lending corruption indicator. To the extent that there was some kind of double counting the inclusion of the general corruption indicator could drive out the significance of the bank lending indicator. This is not the case with our results. Furthermore, the correlation between the two indicators is 0.319, confirming that they capture different aspects of corruption.

To conserve space, we refrain from discussing the findings for the control variables in the main text. We provide a brief discussion in Section III of the Online Appendix.

Akins et al. (2017) estimate this ratio using data for individual banks from BankScope over the period 1995–2006. Subsequently, they aggregate this to the country level by averaging the percentage for all observations across banks in each country. We follow the same approach; however, due to lack of access to BankFocus (formerly known as BankScope) we take the data for individual banks from the Standard and Poor’s Capital IQ Pro database.

For example, in the case of Beck et al. (2006), when controlling for alternative country characteristics, the coefficient of “supervisory power” ranges from 0.093 to 0.187 while the one of “private monitoring” ranges from − 0.275 to − 0.422. In Barth et al., (2009 the coefficient of the “public credit registry” ranges from 0.045 to 0.15, the one of “private bureau” takes vales from − 0.188 to − 0.411, the one of “entry barrier” ranges from 0.038 to 0.214, and so on. In Houston et al. (2011) the coefficient of “Press top 3 concentration” is between 0.104 and 0.212, while the one of “State-owned radio” ranges from 0.023 to 0.152. Similarly, in the case of Zheng et al. (2013) the coefficient of “collectivism” ranges from 0.016 to 0.035 depending on the control variables included in the specification.

It should be noted here that one may also have concerns about selection-based endogeneity (Zheng et al., 2013). This selection bias may be considered a sub-form of the omitted-variable bias issue, which manifests in two main forms: sample-selection and self-selection biases (Clougherty et al., 2016). The World Bank takes several steps to ensure the representation of firms in the Survey with the use of stratified random sampling. This should lessen concerns about sample-selection. However, it is possible that there is some self-selection bias as firms may choose to opt out from taking part in the survey. This is an issue that is common to all past studies on bank lending corruption, and while acknowledging it is not possible to address it (Zheng et al., 2013).

The Wald test of exogeneity is the only readily available diagnostic reported by STATA in the case of IV Probit. The Chi-square (p-value = 0.084) indicates that there is evidence for rejecting the null hypothesis that leadership prototypes and bank lending corruption are exogenous. This result provides support for using the instrumental variables approach that we follow. As it concerns other diagnostics, in “ivprobit” the reduced form for the endogenous explanatory variable is linear, thus we report the same diagnostics as in the linear probability case from a 2SLS. These are as follows: Hansen’s J statistic: 0.293 (p = 0.589); Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistic: 6.736 (p = 0.0345); Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic: 112.733; F test of excluded instruments: 4.53 (Prosocial leadership prototype), 4.27 (Self-serving leadership prototype), 7.27 (Nonautonomous leadership prototype).

The coefficients of Probit regression in the case of the restricted sample are 0.068 (prosocial leadership), 0.419 (self-serving), and − 0.076 (nonautonomous). As before, the self-serving leadership style is the only one that is statistically significant.

After reviewing 255 papers that rely on the IV approach for identifying causal effects published in the “Big Three” finance journals, Jiang (2017) reveals that the IV estimates are larger than their corresponding uninstrumented estimates in about 80% of the studies. Turning to the bank lending studies for example, in the case of Barth et al. (2009), the coefficient of bank concentration in terms of assets (deposits) is 0.839 (0.947) in the case of the Probit regression and 2.425 (2.461) in the case of the IV Probit regression. Similarly, Houston et al. (2011) report coefficients of 0.136 (press state ownership) and 0.135 (press top 3 concentration) in the case of the Probit regression, which increase to 0.335 and 0.320 in the corresponding IV Probit regression. In Akins (2017), the coefficient of the variable of interest equals − 0.182 in the Probit regression and − 0.233 in the IV Probit regression.

The cost of US fines and settlements incurred by banks in the period 2009-2016 is estimated at $321 billion (Grasshoff et al., 2017). Therefore, misconduct-related fines can have important implications for banks. For example, Skinner (2016) mentions that they directly impede banks' ability to fortify their balance sheets against economic shocks. Furthermore, the incidents of misconduct can introduce frictions and raise the cost of financial intermediation, which in turn, reduces the flow of productive financial services (Chaly et al., 2017). From a regulatory perspective, these sorts of external effects that spill over to other market participants provide a strong rationale for official sector intervention related to employee misconduct (Chaly et al., 2017).

In discussion on the need of regulatory involvement to address employee misconduct in the case of banking, Chaly et al. (2017) outline how potentially different management styles, organizational culture, leadership and “tone from above” – e.g. cases where employees feel empowered to raise their hand and believe that their efforts will result in meaningful responses versus cases where employees do not speak freely when they have concerns, result in senior managers or the board of directors not finding out about improper conduct until it is uncovered by the authorities. This suggests a critical role for supervisors who may assess behaviors in an ongoing manner and help to identify potential employee misconduct risks.

Kim et al. (2022) show that media coverage provides an important channel through which investor awareness of corporate wrongdoings can be enhanced, which in turn leads investors to penalize firms more severely.

References

Afridi, F., Iversen, V., & Sharan, M. R. (2017). Women political leaders, corruption, and learning: Evidence from a large public program in India. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 66, 1–30.

Aguiler, R. V., & Vadera, A. K. (2008). The dark side of authority: Antecedents, mechanisms, and outcomes of organizational corruption. Journal of Business Ethics, 77, 431–449.

Akins, B., Dou, Y., & Ng, J. (2017). Corruption in bank lending: The role of timely loan loss recognition. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 63, 454–478.