Abstract

Drawing on the cognitive dissonance theory and the behavioral consistency theory, this study examines whether hypocrisy, proxied by the ethical dissonance between corporate philanthropy and environmental misconducts, triggers auditors to issue modified audit opinions (MAOs), and further investigates the moderating effect of hypocrisy on the relation between financial reporting quality (proxied by discretionary accruals) and MAOs. Using a sample of 20,852 firm-year observations from the Chinese stock market over 2005–2019, our findings reveal that the likelihood of receiving MAOs is significantly higher for hypocritical firms than for their counterparts, suggesting that hypocrisy provides negative soft information about top managers' myopia, immorality and lack of integrity, elicits the perceived distrust from auditors, motivates auditors to have a higher extent of professional skepticism, and eventually triggers MAOs. Moreover, hypocrisy reinforces the negative (positive) relation between financial reporting quality (discretionary accruals) and MAOs. Furthermore, above findings are robust to a variety of sensitivity tests using alternative proxies for modified audit opinions and hypocrisy, as well as different sample compositions, and further our conclusions are still valid after using the propensity score matching approach and two-stage treatment effect regression procedures to control for the endogeneity issue. Lastly, the effect of hypocrisy on MAOs is more pronounced for remedial (ex post) hypocrisy than for preventive (ex ante) hypocrisy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

Notes

“Focal firms” refer to the subject firms that arouse the negative emotions from auditors and other stakeholders.

Zijin Mining Group, a famous firm that has been listed on both the Hong Kong Stock Exchange and the Shanghai Stock Exchange, made substantial donations during the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, but it was found to be a severe environmental destroyer. Nevertheless, Zijin Mining Group did not receive modified audit opinions in 2008. Fushun Special Steel Co., Ltd. (600399) carried out corporate philanthropy in 2016 and 2017, but was administratively punished due to atmospheric pollution. Auditors issued an unqualified opinion with explanatory notes and a disclaimer of opinion in 2016 and 2017, respectively. In 2017, Hubei Yihua Chemical industry Co., Ltd (000422) donated 430 thousand RMB (59 thousand dollars). However, due to “illegally discharge and recidivism” in previous years, the company was administratively punished for several times, and thus received an unqualified opinion with explanatory notes in 2017 (http://hb.sina.com.cn/news/j/2016-12-18/detail-ifxytqax6461811.shtml).

Hypocrisy means the divergence between statements and observed behaviors or the inconsistencies between different CSR dimensions (Scheidler et al., 2019; Wagner et al., 2009), but “window-dressing” means that CSR is carried out for appearance (rather than for promoting structural change; Lin, 2010). In terms of the motivations, window-dressing aims to repair the legitimacy urgently (Cai et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2008; Jo and Na, 2012), overshadow wrongdoings (Du, 2015b), and distract the attention from the truths or underlying problems (Connors et al., 2017; Koehn and Ueng, 2010). As a comparison, hypocrisy can be also used as an important conduit for maintaining the societal legitimacy (Brunsson, 2007), but it is often employed for the conformity to social pressure (Antonetti et al., 2020) and to manage conflicting stakeholder demands (Cho et al., 2015; Nickell and Roberts, 2014). To sum up, window-dressing is related to crisis management tactic (Du, 2015b; Wu et al., 2021), but hypocrisy is more likely to be related to a firm’s routine behaviors rather than occasional activities. Given that the auditor's primary task is to discover and disclose the potential flaws in financial statements (DeAngelo, 1981), routine and on-going hypocrisy are more likely to be related to client integrity.

During the devastating earthquake of Wenchuan in 2008, 368 Chinese firms bestowed the donation of RMB 1.6 billion (about $ 0.24 billion) within 3 days (May 12–14, 2008; http://money.163.com/special/00252MT8/earthquake. html) after the earthquake. In the massive flooding of Henan province in 2021, Alibaba, Tencent and many enterprises quickly responded to the unexpected disaster and donated 100 million RMB (about $ 14.9 million) for the flood, respectively (https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20210721A052JO00). The bandwagon effect of corporate philanthropy exists during sudden and extreme disasters, so firms refer to rivals to adjust their philanthropic decisions.

By 2020, only 3% of Chinese listed firms launch charitable foundations (https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1741279823513251029&wfr=spider&for=pc), which provides strategic support for long-term and routine donations.

For Hypothesis 1 (H1), we discuss two types of associations between hypocrisy and audit opinions. For Hypothesis 2 (H2), we focus on the second type of association.

Untabulated results (available on request) show that hypocrisy is significantly positively related to the likelihood of financial restatements, the probability of tiny profit [ROA lies in (0, 0.01)], the likelihood of meeting and beating earnings forecasts—the difference between actual EPS and the analysts' mean annual earnings forecast lies in (0, 0.01).

These situations include: (1) individuals display stable behavioral pattern across various comparable situations; (2) managerial personality affects their personal and corporate decisions consistently; (3) firms’ policies and decisions might be a manifestation of managerial traits and preferences; and (4) the extent to which an individual exhibits a behavior in one situation is predictable from that of another situation (Cain & McKeon, 2016; Cronqvist et al., 2012; Hjelström et al., 2020; Wang & Cao, 2022).

Internal control can be used as a supportive analogy to interpret the relation between hypocrisy and modified audit opinions. Internal control is essential to financial report quality and directly affects audit opinions. On the one hand, previous literature finds that firms with weak internal control are related to lower accruals quality (Ashbaugh-Skaife et al., 2008; Chan et al., 2008; Doyle et al., 2007). On the other hand, poor internal control can degrade auditors’ trust on financial statements (regardless of the level of financial reporting quality). Jiang et al. (2010) and Goh et al. (2013) validate that internal control weaknesses increases the likelihood that auditors issue modified audit opinions or going concern opinions. Analogically, hypocrisy has similar influential channels on audit opinions.

We also constructHY2 (HY3) to cover 95% of the time interval from the time of environmental misconducts to the time of environmental penalties. Due to environmental misconducts, 60.49% of firms are punished in the same year (year t), and 28.40% of firms are punished due to environmental misconducts in the next year (year t + 1). In addition, accumulated 95% of firm-years receive environmental penalties within 3 years after environmental misconducts.

The potential channels are reported as below: (1) Auditors spend substantial time in communicating with client employees in field audits. Managers, financial staffs and employees of client firms as insiders know more about internal information about environmental misconducts that have happened in year t but may be penalized in the subsequent years. (2) Contingencies in a firm's financial statements about environmental penalties can convey relevant information (about contingent liabilities and estimated liabilities) of year t + 1 to auditors. (3) Other channels through which auditors can get the information about future environmental punishments.

The punishments on environmental misconducts of year t may be made in year t + 1. On November 2, 2015, the Environmental Protection Bureau of Beijing Shunyi conducted the supervisory detection on Advanced Technology & Materials Co., Ltd., and found that the overall nickel discharge exceeded the emission standard. After offering the "Notice of administrative punishment in advance" and undergoing corporate self-justification, the Environmental Protection Bureau of Beijing Shunyi issued the administrative punishment decision to the firm on February 29, 2016.

Compared with earnings management, financial reporting quality is a broader concept, which is also affected by information transparency, financial restatement and financial irregularities. A branch of prior literature employs the signed discretionary accruals to measure earnings management (Bédard et al., 2004; Dhaliwal et al., 2010; Xie et al., 2003), but most studies use the absolute value of the magnitude of discretionary accruals as an inverse proxy for financial report quality (Ham et al., 2017; Krishnan et al., 2011; Labelle et al., 2010). Given the reversing effect of accruals, the absolute measure captures the effect of past as well as current earnings management (Lennox et al., 2016).

The hypocritical subsample and the good-deed subsample represent the worst (hypocritical) and the best (pure) incentives for corporate philanthropy, respectively, and thus the differences in audit opinions between the hypocritical firms and those to the good-deed firms are easier to be observed. Nevertheless, we re-test H1 and H2 using alternative sample constructions: (1) the hypocritical subsample and the clean subsample; (2) the hypocritical subsample and the evil subsample. The results remain qualitatively similar to those in main tests.

Among firms with MAOs, compared with the non-HY subsample, the HY subsample has larger firm size, higher debt-to-asset ratio, lower current ratio, lower ratio of other receivables, more analyst following, higher ratio of institutional ownership, higher proportion of blockholder ownership and better regional economic development level. The time gap between corporate philanthropy and environmental punishments has a mean value of − 0.041 (year), and the average time gap from the time point when environmental violations occur to the time point when environmental violations are punished for the HY subsample among firms with MAOs is 171 days (0.30 year), suggesting that administrative punishments are later about 171 days (0.30 year) than environmental misconducts. When the number of days is converted to the number of year, it may be greater than or less than the actual interval years. If an environmental violation occurred on November 25, 2015 and environmental penalties were imposed on February 25, 2016, then the number of the lagged days is 92 days, which can be converted as the number of the lagged year as 0.252 (92/365) and is less than the actual number of the lagged year (1 year = 2016–2015). (2) If an environmental violation occurred on January 25, 2015 and environmental penalties were imposed on February 25, 2016, then the number of the lagged days is 396, which can be converted as the number of the lagged year as 1.085 (396/365) and is greater than the actual number of the lagged year (1 year = 2016–2015).

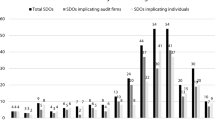

The potential reasons lie in that: (1) The information about environmental misconducts began to be disclosed in 2005, so hypocrisy may be underestimated in the first two years of our research sample period (i.e., 2005 and 2006). (2) For 2019, a relatively lower number of hypocritical firms may be caused by the insufficient time interval from the time point when environmental violations occur to the time point when environmental violations are punished (penalty announcement)—environmental punishments may be not disclosed (when we hand-collect the data).

H1 states that hypocrisy can increase the auditor’s likelihood of issuing a going concern opinion under the context of a risk of going concern in the firm. In response, we further examine whether hypocrisy induces a higher probability of going concern opinions when an actual risk of going concern exists in a given firm. Referring to Guan et al. (2016), financial conditions are proxied by Altman’s Z-score, measured as "0.517 − 0.460 × (total liabilities/total assets) + 9.320 × (net profits/average total assets) + 0.388 × (working capital/total assets) + 1.158 × (retained earnings/total assets)". If Z-score is greater (less) than 0.9 (0.5), then a firm is classified as being financial healthy (distressed). Untabulated results show that HY has a significantly positive (insignificant) coefficient for financial distressed (healthy) firms, suggesting that hypocrisy exerts a more prominent effect on firms that has fallen into a risky environment.

Firms headquartered in provinces with more national nature reserves (RES) are less likely to be hypocritical for two reasons. (1) The national nature reserves need to be approved by the Ministry of Environmental Protection in China, so the authority department has mandatory requirements that the cities should have relatively high responsibility in environmental protections, the local government and people attach the importance to environmental responsibilities, and firms commit to environmental protection and avoid environmental misconducts to obtain the legitimacy from the community and the public (Suchman, 1995). (2) To maintain the qualification of the national nature reserves, environmental regulations in regions with more national nature reserves are persistent. Thus, regions with more national nature reserves have sufficient incentives to mitigate corporate opportunistic behaviors in environmental conservation (i.e., to cover up the negative impact of environmental misconducts by corporate philanthropy).

Due to the fuzzy impact of the year when the CEPL comes into effect, we delete observations in the year of 2015.

In our research sample, 8825 firm-year observations (42.32%) belong to SSE, covering 1287 unique firms. As a comparison, 12,027 firm-year observations (57.68%) belong to SZSE, covering 1,926 unique firms. Above results suggest that firm-year observations from Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges are roughly balanced. Untabulated results show that H1 and H2 are empirically supported for both the SSE subsample and the SZSE subsample.

Also, we construct CONSEC_4 (CONSEC_5)—equaling 1 if a firm carries out philanthropic giving for four (five) consecutive years or more around environmental misconducts and 0 if a firm only carries out philanthropic giving in the year of environmental misconducts. Untabulated results show similar findings.

There is no mandatory requirement or regulation on corporate philanthropy in China. In some cases, the regulation may be caused by illegal activities in corporate philanthropy. For example, Youngor Group (600177.SH) received Regulatory Work Letter from SSE due to 1.36 billion RMB donation plan on May 18, 2022 (the donation was strong opposed by minority shareholders). Thus, SSE decided to investigate the directors, supervisors and senior managers of Youngor Group (https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1733307569777597473&wfr=spider&for=pc). Thus, Chinese firms can independently make the decisions about philanthropic giving as long as shareholders, directors, and management come to an agreement with that. As such, it is difficult to discern the real motivation of corporate philanthropy.

For example, specific contract-level data is needed to construct hypocrisy on the basis of corporate philanthropy and employee welfare, the obligation to suppliers and consumers (see Darendeli et al., 2022).

As a result, it should be very cautious for researchers to generalize our findings to other contexts. Especially, it is better to seek for an exogenous shock in which researchers can apply the difference-in-difference (DID) approach to identify the causal relation between hypocrisy and corporate behaviors.

References

Aharony, J., Lee, C. W. J., & Wong, T. J. (2000). Financial packaging of IPO firms in China. Journal of Accounting Research, 38(1), 103–126.

Allen, F., Qian, J., & Qian, M. (2005). Law, finance, and economic growth in China. Journal of Financial Economics, 77(1), 57–116.

Ambec, S., & Lanoie, P. (2008). Does it pay to be green? A systematic overview. Academy of Management Perspectives, 22(4), 45–62.

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). (1984). Statement on auditing standards no. 47: Audit risk and materiality. AICPA.

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). (2000). Panel on audit effectiveness oversight report and recommendations. AICPA.

Amiram, D., Bozanic, Z., Cox, J. D., Dupont, Q., Karpoff, J. M., & Sloan, R. (2018). Financial reporting fraud and other forms of misconduct: A multidisciplinary review of the literature. Review of Accounting Studies, 23(2), 732–783.

Antonetti, P., Bowen, F., Manika, D., & Higgins, C. (2020). Hypocrisy in corporate and individual social responsibility: Causes, consequences and implications. Journal of Business Research, 114, 325–326.

Aobdia, D., Lin, C. J., & Petacchi, R. (2015). Capital market consequences of audit partner quality. The Accounting Review, 90(6), 2143–2176.

Ashbaugh-Skaife, H., Collins, D. W., Kinney, W. R., Jr., & LaFond, R. (2008). The effect of SOX internal control deficiencies and their remediation on accrual quality. The Accounting Review, 83(1), 217–250.

Atkinson, L., & Galaskiewicz, J. (1988). Stock ownership and company contributions to charity. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33(1), 82–100.

Australian Accounting Research Foundation (AARF). (1990). Statement of accounting concepts no. 2: Objective of general purpose financial information. AARF.

Babu, N., De Roeck, K., & Raineri, N. (2020). Hypocritical organizations: Implications for employee social responsibility. Journal of Business Research, 114, 376–384.

Bae, J., & Cameron, G. T. (2006). Conditioning effect of prior reputation on perception of corporate giving. Public Relations Review, 32(2), 144–150.

Ball, R., & Shivakumar, L. (2006). The role of accruals in asymmetrically timely gain and loss recognition. Journal of Accounting Research, 44(2), 207–242.

Bartov, E., Gul, F. A., & Tsui, J. S. L. (2000). Discretionary-accruals models and audit qualifications. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 30(3), 421–452.

Bédard, J., Chtourou, S. M., & Courteau, L. (2004). The effect of audit committee expertise, independence, and activity on aggressive earnings management. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 23(2), 13–35.

Bellucci, M., Acuti, D., Simoni, L., & Manetti, G. (2021). Hypocrisy and legitimacy in the aftermath of a scandal: An experimental study of stakeholder perceptions of nonfinancial disclosure. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 34(9), 151–163.

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., Gomez-Mejia, L. R., & Larraza-Kintana, M. (2010). Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: Do family-controlled firms pollute less? Administrative Science Quarterly, 55(1), 82–113.

Brunsson, N. (2007). The consequences of decision making. Oxford University Press.

Cai, Y., Jo, H., & Pan, C. (2012). Doing well while doing bad? CSR in controversial industry sectors. Journal of Business Ethics, 108(4), 467–480.

Cain, M. D., & McKeon, S. B. (2016). CEO personal risk-taking and corporate policies. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 51(1), 139–164.

Campbell, L., Gulas, C. S., & Gruca, T. S. (1999). Corporate giving behavior and decision-maker social consciousness. Journal of Business Ethics, 19(4), 375–383.

Carlos, W. C., & Lewis, B. W. (2018). Strategic silence: Withholding certification status as a hypocrisy avoidance tactic. Administrative Science Quarterly, 63(1), 130–169.

Carpenter, T. D., & Reimers, J. L. (2005). Unethical and fraudulent financial reporting: Applying the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 60(2), 115–129.

Carter, C., & Spence, C. (2014). Being a successful professional: An exploration of who makes partner in the Big 4. Contemporary Accounting Research, 31(4), 949–981.

Chan, K. C., Farrell, B., & Lee, P. (2008). Earnings management of firms reporting material internal control weaknesses 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 27(2), 161–179.

Chaney, P. K., Jeter, D. C., & Shivakumar, L. (2004). Self-selection of auditors and audit pricing in private firms. The Accounting Review, 79(1), 51–72.

Chen, C. J. P., Chen, S., & Su, X. (2001). Profitability regulation, earnings management, and modified audit opinions: Evidence from China. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 20(2), 9–30.

Chen, F., Peng, S., Xue, S., Yang, Z., & Ye, F. (2016). Do audit clients successfully engage in opinion shopping? Partner-level evidence. Journal of Accounting Research, 54(1), 79–112.

Chen, J. C., Patten, D. M., & Roberts, R. W. (2008). Corporate charitable contributions: A corporate social performance or legitimacy strategy? Journal of Business Ethics, 82(1), 131–144.

Chen, S., & Kenbata, B. (2011). The impact of underwriter reputation on initial returns and long-run performance of Chinese IPOs. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 21(5), 760–791.

Chen, S., Sun, S. Y., & Wu, D. (2010). Client importance, institutional improvements, and audit quality in China: An office and individual auditor level analysis. The Accounting Review, 85(1), 127–158.

Chen, Z., Hang, H., Pavelin, S., & Porter, L. (2020). Corporate social (ir)responsibility and corporate hypocrisy: Warmth, motive and the protective value of corporate social responsibility. Business Ethics Quarterly, 30(4), 486–524.

Chih, H. L., Shen, C. H., & Kang, F. C. (2008). Corporate social responsibility, investor protection, and earnings management: Some international evidence. Journal of Business Ethics, 79, 179–198.

China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC). (2021). Order of China securities regulatory commission no. 182: The administrative measures for information disclosure of listed companies. CSRC.

Cho, C. H., Laine, M., Roberts, R. W., & Rodrigue, M. (2015). Organized hypocrisy, organizational façades, and sustainability reporting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 40, 78–94.

Choi, J. H., Kim, J. B., Qiu, A. A., & Zang, Y. (2012). Geographic proximity between auditor and client: How does it impact audit quality? Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 31(2), 43–72.

CICPA (Chinese Institute of Certified Public Accountants). (2010). Auditing standards for certified public accountants of China no. 1153: Communications between predecessor and successor auditors. CICPA.

CICPA. (2013). Interpretation of “auditing standards for certified public accountants of China no. 1101: The general objectives of certified public accountants and the basic requirements of audit work” No. 1: Professional Skepticism. CICPA.

CICPA. (2022). Application note of “auditing standards for certified public accountants of China no 1101: The general objectives of certified public accountants and the basic requirements of audit work.” CICPA.

Cohen, J. R., Dalton, D. W., & Harp, N. L. (2017). Neutral and presumptive doubt perspectives of professional skepticism and auditor job outcomes. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 62, 1–20.

Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). (2013). Internal control: Integrated framework. AICPA.

Connors, S., Anderson-MacDonald, S., & Thomson, M. (2017). Overcoming the ‘window dressing’ effect: Mitigating the negative effects of inherent skepticism towards corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 145(3), 599–621.

Cronqvist, H., Makhija, A. K., & Yonker, S. E. (2012). Behavioral consistency in corporate finance: CEO personal and corporate leverage. Journal of Financial Economics, 103(1), 20–40.

Dao, M., Raghunandan, K., & Rama, D. V. (2012). Shareholder voting on auditor selection, audit fees, and audit quality. The Accounting Review, 87(1), 149–171.

Darendeli, A., Fiechter, P., Hitz, J. M., & Lehmannd, N. (2022). The role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) information in supply-chain contracting: Evidence from the expansion of CSR rating coverage. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 74(2–3), 101525.

Dasgupta, S., Hong, J. H., Laplante, B., & Mamingi, N. (2006). Disclosure of environmental violations and stock market in the Republic of Korea. Ecological Economics, 58(4), 759–777.

Davis, K. (1973). The case for and against business assumption of social responsibilities. Academy of Management Journal, 16(2), 312–322.

DeAngelo, L. E. (1981). Auditor size and audit quality. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 3(3), 183–199.

DeFond, M., Wong, T. J., & Li, S. (2000). The impact of improved auditor independence on audit market concentration in China. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 28(3), 269–305.

DeFond, M. L., & Zhang, J. (2014). A review of archival auditing research. Journal of Accounting and Economics., 58(2–3), 275–326.

DesJardine, M. R., & Durand, R. (2020). Disentangling the effects of hedge fund activism on firm financial and social performance. Strategic Management Journal, 41(6), 1054–1082.

Dhaliwal, D. S., Li, O. Z., Tsang, A., & Yang, Y. G. (2011). Voluntary nonfinancial disclosure and the cost of equity capital: The initiation of corporate social responsibility reporting. The Accounting Review, 86(1), 59–100.

Dhaliwal, D., Naiker, V., & Navissi, F. (2010). The association between accruals quality and the characteristics of accounting experts and mix of expertise on audit committees. Contemporary Accounting Research, 27(3), 787–827.

Doyle, J. T., Ge, W., & McVay, S. (2007). Accruals quality and internal control over financial reporting. The Accounting Review, 82(5), 1141–1170.

Driver, M. (2006). Beyond the stalemate of economics versus ethics: Corporate social responsibility and the discourse of the organizational self. Journal of Business Ethics, 66, 337–356.

Du, X. (2015a). How the market values greenwashing? Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(3), 547–574.

Du, X. (2015b). Is corporate philanthropy used as environmental misconduct dressing? Evidence from Chinese family-owned firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 129(2), 341–361.

Du, X. (2021). On informal institutions and accounting behavior. Springer.

Du, X., Jian, W., Du, Y., Feng, W., & Zeng, Q. (2014). Religion, the nature of ultimate owner, and corporate philanthropic giving: Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics, 123(2), 235–256.

Du, X., Jian, W., Zeng, Q., & Chang, Y. (2018). Do auditors applaud corporate environmental performance? Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics, 151, 1049–1080.

Du, X., Weng, J., Zeng, Q., Chang, Y., & Pei, H. (2017). Do lenders applaud corporate environmental performance? Evidence from Chinese private-owned firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 143, 179–207.

Effron, D. A., O’Connor, K., Leroy, H., & Lucas, B. J. (2018). From inconsistency to hypocrisy: When does “saying one thing but doing another” invite condemnation? Research in Organizational Behavior, 38, 61–75.

Endrikat, J. (2016). Market reactions to corporate environmental performance related events: A meta-analytic consolidation of the empirical evidence. Journal of Business Ethics, 138, 535–548.

Etzion, D. (2007). Research on organizations and the natural environment, 1992-present: A review. Journal of Management, 33(4), 637–664.

Fan, J. P., Wong, T. J., & Zhang, T. (2007). Politically connected CEOs, corporate governance, and Post-IPO performance of China’s newly partially privatized firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 84(2), 330–357.

Fassin, Y., & Buelens, M. (2011). The hypocrisy-sincerity continuum in corporate communication and decision making: A model of corporate social responsibility and business ethics practices. Management Decision, 49(4), 586–600.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). (1978). Statements of financial accounting concepts no. 1. objectives of financial reporting by business enterprises. FASB.

Flammer, C. (2013). Corporate social responsibility and shareholder reaction: The environmental awareness of investors. Academy of Management Journal, 56(3), 758–781.

Francis, J. R., & Krishnan, J. (1999). Accounting accruals and auditor reporting conservatism. Contemporary Accounting Research, 16(1), 135–165.

Fu, L., Boehe, D. M., Orlitzky, M., & Swanson, D. L. (2016). Inconsistency in Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Risk. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2016, No. 1, p. 13291).

Gaver, J., & Paterson, J. (2007). The influence of large clients on office-level auditor oversight: Evidence from the property-casualty insurance industry. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 43(2–3), 299–320.

Goh, B. W., Krishnan, J., & Li, D. (2013). Auditor reporting 404: The association between the internal control and going concern audit opinions. Contemporary Accounting Research, 30(3), 970–995.

Guan, Y., Su, L. N., Wu, D., & Yang, Z. (2016). Do school ties between auditors and client executives influence audit outcomes? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 61(2), 506–525.

Ham, C., Lang, M., Seybert, N., & Wang, S. (2017). CFO Narcissism and financial reporting quality. Journal of Accounting Research, 55(5), 1089–1135.

Hamilton, D. L., & Sherman, S. J. (1996). Perceiving persons and groups. Psychological Review, 103(2), 336–355.

Hamilton, E. L. (2016). Evaluating the intentionality of identified misstatements: How perspective can help auditors in distinguishing errors from fraud. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 35(4), 57–78.

Handelman, J. M., & Arnold, S. J. (1999). The role of marketing actions with a social dimension: Appeals to the institutional environment. Journal of Marketing, 63(3), 33–48.

Harmon-Jones, E. (2000). Cognitive dissonance and experienced negative affect: Evidence that dissonance increases experienced negative affect even in the absence of aversive consequences. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(12), 1490–1501.

Harmon-Jones, E., & Mills, J. (2019). An introduction to cognitive dissonance theory and an overview of current perspectives on the theory. In E. Harmon-Jones (Ed.), Cognitive dissonance: Reexamining a pivotal theory in psychology (pp.3–24). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000135-001.

Healy, P. M., & Wahlen, J. M. (1999). A review of the earnings management literature and its implications for standard setting. Accounting Horizons, 13(4), 365–383.

Heckman, J. J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–161.

Helm, S., & Tolsdorf, J. (2013). How does corporate reputation affect customer loyalty in a corporate crisis? Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 21(3), 144–152.

Hirst, D. E. (1994). Auditor sensitivity to earnings management. Contemporary Accounting Research, 11(1), 405–422.

Hjelström, T., Kallunki, J. P., Nilsson, H., & Tylaite, M. (2020). Executives’ personal tax behavior and corporate tax avoidance consistency. European Accounting Review, 29(3), 493–520.

Janney, J. J., & Gove, S. (2011). Reputation and corporate social responsibility aberrations, trends, and hypocrisy: Reactions to firm choices in the stock option backdating scandal. Journal of Management Studies, 48(7), 1562–1585.

Jenkins, J. G., Deis, D. R., Bedard, J. C., & Curtis, M. B. (2008). Accounting firm culture and governance: A research synthesis. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 20(1), 45–74.

Jiang, W., Rupley, K. H., & Wu, J. (2010). Internal control deficiencies and the issuance of going concern opinions. Research in Accounting Regulation, 22(1), 40–46.

Jo, H., & Na, H. (2012). Does CSR reduce firm risk? Evidence from controversial industry sectors. Journal of Business Ethics, 110(4), 441–456.

Johl, S., Jubb, C. A., & Houghton, K. A. (2007). Earnings management and the audit opinion: Evidence from Malaysia. Managerial Auditing Journal, 22(7), 688–715.

Johnstone, K. M., Sutton, M. H., & Warfield, T. D. (2001). Antecedents and consequences of independence risk: Framework for analysis. Accounting Horizons, 15(1), 1–18.

Jonas, E., & Frey, D. (2003). Information search and presentation in advisor-client interactions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 91(2), 154–168.

Jones, J. J. (1991). Earnings management during import relief investigations. Journal of Accounting Research, 29(2), 193–228.

Jung, S., Bhaduri, G., & Ha-Brookshire, J. E. (2020). What to say and what to do: The determinants of corporate hypocrisy and its negative consequences for the customer-brand relationship. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 30(3), 481–491.

Karpoff, J. M., Lott, J. R., Jr., & Wehrly, E. W. (2005). The reputational penalties for environmental violations: Empirical evidence. The Journal of Law and Economics, 48(2), 653–675.

Kassinis, G., & Vafeas, N. (2002). Corporate boards and outside stakeholders as determinants of environmental litigation. Strategic Management Journal, 23(5), 399–415.

Kerler, W. A., III., & Killough, L. N. (2009). The effects of satisfaction with a client’s management during a prior audit engagement, trust, and moral reasoning on auditors’ perceived risk of management fraud. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(2), 109–136.

Kim, J. B., & Yi, C. H. (2006). Ownership structure, business group affiliation, listing status, and earnings management: Evidence from Korea. Contemporary Accounting Research, 23(2), 427–464.

Kim, S., Choi, M. S., & Atkinson, L. (2017). Congruence effects of corporate associations and crisis issue on crisis communication strategies. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 45(7), 1085–1098.

Kim, S., & Choi, S. M. (2018). Congruence effects in post-crisis CSR communication: The mediating role of attribution of corporate motives. Journal of Business Ethics, 153, 447–463.

Kim, Y., Park, M. S., & Wier, B. (2012). Is earnings quality associated with corporate social responsibility? The Accounting Review, 87(3), 761–796.

Koehn, D., & Ueng, J. (2010). Is philanthropy used by corporate wrongdoer to buy good will? Journal of Management and Governance, 14, 1–16.

Konar, S., & Cohen, M. A. (2001). Does the market value environmental performance? Review of Economics and Statistics, 83(2), 281–289.

Kong, D., Liu, S., & Dai, Y. (2014). Environmental policy, company environment protection, and stock market performance: Evidence from China. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 21(2), 100–112.

Krishnan, J., Wen, Y., & Zhao, W. (2011). Legal expertise on corporate audit committees and financial reporting quality. The Accounting Review, 86(6), 2099–2130.

Labelle, R., Gargouri, R. M., & Francoeur, C. (2010). Ethics, diversity management, and financial reporting quality. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(2), 335–353.

Lawrence, A., Minutti-Meza, M., & Zhang, P. (2011). Can big 4 versus non-big 4 differences in audit-quality proxies be attributed to client characteristics? The Accounting Review, 86(1), 259–286.

Lennox, C. S., Francis, J. R., & Wang, Z. (2012). Selection models in accounting research. The Accounting Review, 87(2), 589–616.

Lennox, C., Wang, C., & Wu, X. (2020). Opening up the “Black box” of audit firms: The effects of audit partner ownership on audit adjustments. Journal of Accounting Research, 58(5), 1299–1341.

Lennox, C., Wu, X., & Zhang, T. (2016). The effect of audit adjustments on earnings quality: Evidence from China. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 61(2), 545–562.

Lenz, I., Wetzel, H. A., & Hammerschmidt, M. (2017). Can doing good lead to doing poorly? Firm value implications of CSR in the face of CSI. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45, 677–697.

Li, C. (2009). Does client importance affect auditor independence at the office level? Empirical evidence from going-concern opinions. Contemporary Accounting Research, 26(1), 201–230.

Li, D., He, J., & Jiang, J. (2019). Big egos can cause natural disasters: How CEO overconfidence leads to environmental misconducts. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2019, No. 1, p. 13261).

Li, K., & Prabhala, N. (2007). Self-selection models in corporate finance. In B. E. Eckso (Ed.), Handbook of corporate finance: Empirical corporate finance (pp. 37–46). Elsevier Science B.V.

Li, W., & Zhang, R. (2010). Corporate social responsibility, ownership structure, and political interference: Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics, 96(4), 631–645.

Lin, L. W. (2010). Corporate social responsibility in China: Window dressing or structural change. Berkeley Journal of International Law, 28(1), 64–100.

Liu, C. (2018). Are women greener? Corporate gender diversity and environmental violations. Journal of Corporate Finance, 52, 118–142.

Loughran, T., & Ritter, J. R. (1995). The new issues puzzle. Journal of Finance, 50(1), 23–51.

Maddala, G. S. (1983). Limited-dependent and qualitative variables in econometrics. Cambridge University Press.

Marhfor, A., Bouslah, K. B. H., & M’Zali, B. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and executive compensation: The negative externality perspective. Journal of Finance and Risk Perspectives, 9(1), 15–31.

Marín, L., Cuestas, P. J., & Román, S. (2016). Determinants of consumer attributions of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 138(2), 247–260.

Marquis, C., Glynn, M. A., & Davis, G. F. (2007). Community isomorphism and corporate social action. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 925–945.

McGrath, A. (2017). Dealing with dissonance: A review of cognitive dissonance reduction. Social Personality Psychology Compass, 11(12), e12362.

Meng, X. H., Zeng, S. X., Xie, X. M., & Qi, G. Y. (2016). The impact of product market competition on corporate environmental responsibility. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 33, 267–291.

Minor, D. (2016). Executive Compensation and Misconduct: Evironmental Harm. Harvard Business School.

Mitchell, M. L., & Stafford, E. (2001). Managerial decisions and long-term stock price performance. The Journal of Business, 73(3), 287–329.

Muller, A., & Kräussl, R. (2011). Doing good deeds in times of need: A strategic perspective on corporate disaster donations. Strategic Management Journal, 32(9), 911–929.

Murphy, C. J. (2002). The profitable correlation between environmental and financial performance: A review of the research. Light Green Advisors, Inc. Retrieved from http://www.lightgreen.com/files/pc.pdf

Murphy, L., & Hogan, R. (2016). Financial reporting of non-financial information: The role of the auditor. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance, 28(1), 42–49.

Myers, J. N., Myers, L. A., & Omer, T. C. (2003). Exploring the term of the auditor-client relationship and the quality of earnings: A case for mandatory auditor rotation? The Accounting Review, 78(3), 779–799.

Nakamura, M., Takahashi, T., & Vertinsky, I. (2001). Why Japanese firms choose to certify: A study of managerial responses to environmental issues. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 42(1), 23–52.

Nelson, M. W. (2009). A model and literature review of professional skepticism in auditing. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 28(2), 1–34.

Nelson, M., & Tan, H. T. (2005). Judgment and decision making research in auditing: A task, person, and interpersonal interaction perspective. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory., 24(s1), 41–71.

Nickell, E. B., & Roberts, R. W. (2014). Organizational legitimacy, conflict, and hypocrisy: An alternative view of the role of internal auditing. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 25(3), 217–221.

Palazzo, G., & Scherer, A. G. (2006). Corporate legitimacy as deliberation: A communicative framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 66, 71–88.

Patten, D. M. (2008). Does the market value corporate philanthropy? Evidence from the response to the 2004 tsunami relief effort. Journal of Business Ethics, 81(3), 599–607.

Petersen, M. A. (2009). Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. Review of Financial Studies, 22(1), 435–480.

Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). (2012). Maintaining and applying professional skepticism in audits staff audit practice alert no. 10. PCAOB.

Public Oversight Board (POB). (2000). The panel on audit effectiveness: Report and recommendations. POB.

Quadackers, L., Groot, T., & Wright, A. (2014). Auditors’ professional skepticism: Neutrality versus presumptive doubt. Contemporary Accounting Research, 31(3), 639–657.

Reichelt, K. J., & Wang, D. (2010). National and office-specific measures of auditor industry expertise and effects on audit quality. Journal of Accounting Research, 48(3), 64–686.

Reynolds, J. K., & Francis, J. (2000). Does size matter? The influence of large clients on office-level auditor reporting decisions. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 30(3), 375–400.

Roxas, B., & Coetzer, A. (2012). Institutional environment, managerial attitudes and environmental sustainability orientation of small firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 111, 461–476.

Russo, J. E., Medvec, V. H., & Meloy, M. G. (1996). The distortion of information during decisions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 66(1), 102–110.

Russo, M. V., & Fouts, P. A. (1997). A resource-based perspective on corporate environmental performance and profitability. Academy of Management Journal, 40(3), 534–559.

Saiia, D. H., Carroll, A. B., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2003). Philanthropy as strategy when corporate charity “begins at home.” Business and Society, 42(2), 169–201.

Sajko, M., Boone, C., & Buyl, T. (2021). CEO greed, corporate social responsibility, and organizational resilience to systemic shocks. Journal of Management, 47(4), 957–992.

Sánchez, C. M. (2000). Motives for corporate philanthropy in El Salvador: Altruism and political legitimacy. Journal of Business Ethics, 27(4), 363–375.

Scheidler, S., Edinger-Schons, L. M., Spanjol, J., & Wieseke, J. (2019). Scrooge posing as Mother Teresa: How hypocritical social responsibility strategies hurt employees and firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 157(2), 339–358.

Seifert, B., Morris, S. A., & Bartkus, B. R. (2003). Comparing big givers and small givers: Financial correlates of corporate philanthropy. Journal of Business Ethics, 45(3), 195–211.

Shim, K., Chung, M., & Kim, Y. (2017). Does ethical orientation matter? Determinants of public reaction to CSR communication. Public Relations Review, 43(4), 817–828.

Shklar, J. N. (1984). Ordinary Vices. Belknap.

Sohn, Y. J., & Lariscy, R. W. (2015). A “buffer” or “boomerang”? The role of corporate reputation in bad times. Communication Research, 42(2), 237–259.

Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610.

Telle, K. (2006). ‘It pays to be green’: A premature conclusion? Environmental and Resource Economics, 35(3), 195–220.

Wagner, T., Lutz, R. J., & Weitz, B. A. (2009). Corporate hypocrisy: Overcoming the threat of inconsistent corporate social responsibility perceptions. Journal of Marketing, 73(6), 77–91.

Walls, J. L., & Berrone, P. (2017). The power of one to make a difference: How informal and formal CEO power affect environmental sustainability. Journal of Business Ethics, 145, 293–308.

Wang, J., & Cao, J. (2022). Inter-firm executive mobility and corporate social responsibility: Evidence from China. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 904450.

Wang, Q., Wong, T. J., & Xia, L. (2008). State ownership, the institutional environment, and auditor choice: Evidence from China. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 46(1), 112–134.

Westermann, K. D., Cohen, J., & Trompeter, G. (2019). PCAOB inspections: Public accounting firms on “Trial.” Contemporary Accounting Research, 36(2), 694–731.

Wood, D. J. (1991). Corporate social performance revisited. Academy of Management Review, 16(4), 691–718.

Wu, B., Jin, C., Monfort, A., & Hua, D. (2021). Generous charity to preserve green image? Exploring linkage between strategic donations and environmental misconduct. Journal of Business Research, 131, 839–850.

Xie, B., Davidson, W., & DaDalt, P. (2003). Earnings management and corporate governance: The role of the board and the audit committee. Journal of Corporate Finance, 9(3), 295–316.

Xin, C., Hao, X., & Cheng, L. (2022). Do environmental administrative penalties affect audit fees? Results from multiple econometric models. Sustainability, 14(7), 4268.

Yoon, Y., Gürhan-Canli, Z., & Schwarz, N. (2006). The effect of corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities on companies with bad reputations. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(4), 377–390.

Zadek, S. (1998). Balancing performance, ethics, and accountability. Journal of Business Ethics, 17, 1421–1442.

Zhang, H., Tao, L., Yang, B., & Bian, W. (2023). The relationship between public participation in environmental governance and corporations’ environmental violations. Finance Research Letters, 53, 103676.

Zhang, L., Ren, S., Chen, X., Li, D., & Yin, D. (2020). CEO hubris and firm pollution: State and market contingencies in a transitional economy. Journal of Business Ethics, 161, 459–478.

Zhang, R., Rezaee, Z., & Zhu, J. (2010a). Corporate philanthropic disaster response and ownership type: Evidence from Chinese firms’ response to the Sichuan earthquake. Journal of Business Ethics, 91(1), 51–63.

Zhang, R., Zhu, J., Yue, H., & Zhu, C. (2010b). Corporate philanthropic giving, advertising intensity, and industry competition level. Journal of Business Ethics, 94(1), 39–52.

Zhang, Z., Gong, M. Zhang, S., & Jia, M. (2022). Buffering or aggravating effect? Examining the effects of prior corporate social responsibility on corporate social irresponsibility. Journal of Business Ethics.

Zou, H., Zeng, S., Qi, G., & Shuai, P. (2017). Do environmental violations affect corporate loan financing? Evidence from China. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal, 23(7), 1775–1795.

Zou, H. L., Zeng, S. X., Zhang, X. L., Lin, H., & Shi, J. J. (2015). The intra-industry effect of corporate environmental violation: An exploratory study. Journal of Cleaner Production, 107, 428–437.

Zyglidopoulos, S. C., Georgiadis, A. P., Carroll, C. E., & Siegel, D. S. (2012). Does media attention drive corporate social responsibility? Journal of Business Research, 65(11), 1622–1627.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate constructive comments and valuable suggestions from Prof. Steven Dellaportas (the Section Editor), four anonymous reviewers, Rui Yu, Ying Zhang, Qiao Lin, Liang Xiao, Yuhui Xie, Xinshu Zhang, Jing Hong, Ruining Li, and participants of our presentations at Xiamen University and Xiamen National Accounting Institute. Prof. Xingqiang Du acknowledges financial support from the National Social Science Foundation of China ( 20&ZD111).

Funding

We acknowledge the financial support from the National Social Science Foundation of China (Approval Numbers: 22VRC130).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, X., Zhang, Y., Lai, S. et al. How Do Auditors Value Hypocrisy? Evidence from China. J Bus Ethics 191, 501–533 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05465-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05465-2