Abstract

Employing theoretical resources from Transactional Analysis (TA) and drawing from interviews with managers dealing with social or environmental issues in their role, we explain how CSR activity provides a context for dramas in which actors may ignore, or discount aspects of self, others, and the contexts of their work as they maintain and reproduce the roles of Rescuers, Persecutors and Victims. In doing so, we add to knowledge about CSR by providing an explanation for how the contradictions of CSR are avoided in practice even when actors may be aware of them. Specifically, we theorise how CSR work can produce dramatic stories where adversity is apparently overcome, whilst little is actually achieved at the social level. We also add to the range of psychoanalytic tools used to account for organisational behaviours, emphasising how TA can explain the relational dynamics of CSR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Beyond initial normative claims and later critical reflections about Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) (Banerjee 2008; Devinney 2009; Driver 2006; Fleming et al. 2013; Prieto-Carrón et al. 2006), there remains scope for empirical work that considers the lived experience of those in what Tams and Marshall (2011) call ‘responsible careers’. Although previous accounts suggest that some managers may understand the tensions within CSR, and on occasion attempt to transform organisations for the better (Carrington et al. 2018; Wright et al. 2012), such research has not fully addressed why most who undertake CSR work do not take such actions, or indeed why CSR projects may fail to produce significant results despite the apparent good intent of individuals. We therefore aim to understand how those in responsible careers sustain an experience of doing good, whilst avoiding the contradictions of their work, especially where outcomes are limited. Recognising that CSR involves interactions between multiple actors (policymakers, corporations, partner NGOs and beneficiaries), our approach is to turn to Transactional Analysis (TA)—a psychoanalytic theory that specifically deals with dysfunction in relationships—to examine the underlying relational dynamics of CSR work. TA allows us to recognise how individuals can reproduce a particular position in the world through interactions with others that are ripe with drama, whilst ignoring information that might allow for alternative possibilities.

Specifically, we aim to understand: (1) the relational dynamics of CSR activity, and; (2) how these relational dynamics explain contradictions between the positive intent of CSR and observations that it is frequently ineffective at addressing the issues it claims to be about. To do this, we consider three illustrative stories drawn from forty-seven in-depth interviews with managers dealing with environmental and social issues in Romania.

Our interpretation reveals two characteristics of Romanian CSR. Firstly, in their stories, participants make distinctions between vulnerable groups in need of help, those who persecute them, and the rescuers who help them, yet these roles seem to switch round as dramatic stories unfold. Secondly, these personal narratives seem to require a lot of ‘not knowing’. Participants’ stories suggest that ignoring the significance of information, possibilities for significant change, and their full ability to react to stimuli and available options, perpetuates the limited success of CSR projects, whilst creating the conditions necessary for people to remain invested in their roles.

We begin by considering the contradictions in CSR, highlighting the value of studies of actual CSR activity and the people who enact it. We then explain the usefulness of psychoanalysis in management studies, and how TA provides an enabling theory to understand CSR work. We then apply TA to practitioners’ narratives to theorise the relational dynamics of CSR activity and associated discounting. Finally, we discuss the implications for CSR theory and practice.

Contradictions in CSR Theory and Practice

Early CSR research focused on abstract organisational benefits. For example, Brown and Dacin (1997) suggested that CSR improves consumer evaluations of companies, Mohr et al. (2001) observed that purchase decisions are influenced by CSR and Salmones et al. (2005) concluded that CSR indirectly builds customer loyalty.

However, following this initial enthusiasm for organisational benefits, and a related bias towards the business case for CSR (Prieto-Carrón et al. 2006), concerns started to emerge. For example, Banerjee (2008) argues that CSR discourse represents narrow business interests that serve to sustain the power of corporations, Devinney (2009) points out that CSR activities have little accountability or transparency, and Fleming et al. (2013) confirm a growing suspicion of CSR as merely an excuse for ‘business as usual’. Even the business case for CSR is questioned by Margolis et al. (2009) who found no evidence for supernormal company returns. We are left with a view of CSR where although some may still believe that ‘what is good for society is good for business’, there is an established critique of the overall project (Banerjee 2008).

Fleming and Jones (2012) argue that as the negative impact of corporations on society and environment is systemic, CSR is unable to address such phenomena through small-scale, piecemeal and promotional initiatives. Instead, CSR merely tries to persuade that corporate and societal goals can be ‘aligned’, serving as a smokescreen that increases profitability through reputation, yet is unable to deliver broad societal outcomes (Fleming and Jones 2012). CSR is presented as an ‘enlightened’ activity especially for those involved in such work as ‘it provides a medium for people to express their values […] and remain employed in the firm with minimum emotional dissonance’ (Fleming and Jones 2012, p. 77). They further see CSR as ‘parasitical’ of the very problems caused by businesses, resulting in ‘green marketing’, ‘organic products’ and the ‘fair trade movement’. CSR is therefore a double exploitation. After exploiting the environment and communities, businesses now exploit the situation they’ve created by positioning themselves as a solution.

Whilst there has been no shortage of debate about the CSR project, there is less empirical work on how it actually gets done (Costas and Kärreman 2013). As critical positions have been developed, however, we do see specific studies that highlight cynical, or ineffective CSR projects. For example, Akpan (2008) reports on how Nigerian communities are impacted by petroleum industries. Noting Aristotle’s view that: ‘a benefactor loves the beneficiary of his kindness more than the beneficiary loves him’, Akpan explains how the business advantages of helping communities seem greater than the value to beneficiaries, further noting that such citizenship activities position companies as supporting local populations by apparently addressing failures in the local government, whilst obscuring the corporation’s destruction of local environments and livelihoods. Specifically, Akpan (2008) explains how benefactors’ perspectives were often the opposite of beneficiaries. For example, a corporation claimed to invest in communities, but beneficiaries’ experience was that it produced distrust and corruption. The jostling for relationships with oil companies, states agencies, and political actors also illustrates the dramatic nature of CSR relationships, despite reports of the absence of significant long-term societal improvements.

Yu (2009) provides a similar case of Reebok’s footwear suppliers in China, again noting how beneficiaries are presented as passive recipients of help, whilst businesses are presented as the ‘only’ entities that can improve their situation. Yu argues that CSR fails to empower workers to produce meaningful change for themselves. Specifically, Reebok rejected worker unions in favor of their own (ineffective) worker panels, so that they could maintain control of the discourse and so promote business interests.

Gilberthorpe and Banks (2012) consider another troubling example in Papua New Guinea’s extractive industries sector. Here CSR aims to legitimise business after environmental disasters and breaches of indigenous rights. Despite considerable CSR efforts, Gilberthorpe and Banks (2012) observed little socio-economic development at the grassroots. Instead, they describe an uneasy relationship between development and CSR that involves organisational ‘blinkeredness’ to local change, where businesses are unable to see the full consequences of their actions. Specifically, the authors note how compensation schemes (a levy paid to local communities for extraction of minerals from their land) negatively impacted community coherence, resulting in the breakdown of established intra-tribal bonds. This further highlights the relational aspect of CSR that involves actors with a different perspectives and intents.

Brei and Böhm (2014) further highlight the contradictions of CSR by analyzing Volvic’s apparently successful—in terms of sales—‘1L = 10L for Africa’ campaign. Following criticism over negative environmental impacts, the bottled water industry created cause-related marketing campaigns based on providing clear water for African villages, who are again portrayed as passive, and in need of help from Western corporations. Bottled water was transformed into a consumer activist commodity to boost sales in the West, whilst doing little to actually address water poverty. Hence the ‘poor’ and their social problems become a business opportunity. The corporate response to criticism from environmentalists was to recast themselves as rescuers of constructed victims. Brei and Böhm (2014) argue that such arrangements are ‘dangerous’, as organisations profit from ongoing exploitation of a global social problem, whilst deflecting critique, and so maintaining the status quo rather than addressing societal needs.

As a final example of ‘failed CSR’, we may consider Jamali et al.’s (2017) study of football manufacturing in India. They note that despite the high visibility of CSR aimed at eliminating child labor, conditions on the ground remained fundamentally unchanged. CSR was ‘decoupled’ from the organisation so that it could develop without impacting commercial practices. Yet again, organisations that perceive that they are being persecuted for unethical practices, respond by switching things round so that they become a solution, creating both selective victims and other persecutors in the process. In Jamali et al.’s (2017) research, CSR initiatives insisted that suppliers don’t use child labor, but the corporation continued to force down supplier prices, the very mechanism that makes child labor necessary. The focus on child labor also ignored other damaging work-related issues whilst claiming CSR success. Jamali et al. (2017) conclude that CSR is a symbolic façade; all appearance and little content.

Together, these studies suggest how actors may be positioned in CSR activity as passive recipient-victims, CSR rescuers, and some third party (often government or local officials) as the ‘real’ persecutors. They further show how problems don’t actually get solved, and yet how CSR seems to create considerable drama. We may want to conclude that CSR is cynical, yet it is hard to imagine that all those involved in responsibility work are so. Like the abstract scales and surveys of early CSR theorisation with its managerial bias, critical meso-level cases don’t fully account for the psychology of those that enact CSR. This leads us to consider studies that specifically deal with the experiences of responsibility workers.

The People Involved in CSR Activity

Amongst limited micro-level studies, Hemingway and Maclagan (2004) recognised that for CSR to happen, there must be managers willing to develop and support such activity. This requires both alignment with their personal values and opportunities to use to their discretion. For example, Van Aaken et al. (2013) highlight CSR work as a way to accumulate social and cultural capital, recognising the non-economic motivations of managers that drive CSR efforts. Alternatively, Siltaoja et al. (2015) recognise that employees must also enact corporate claims to do good, drawing from Foucault to argue that CSR involves governmentality, where employees internalise CSR discourse and are so denied a critical engagement with CSR that might allow ‘authentic’ individual ethics may emerge.

Wright et al. (2012) have also researched the experiences of managers, highlighting that grand discourses such as climate change result in tensions, conflicts and denials, as businesses try to maintain legitimacy and present themselves as good corporate citizens. Yet such macro issues are themselves shaped by how managers see themselves in their responses to them, with those managers who accept the discourse of climate change becoming ‘outsiders within the company’. Wright et al. (2012) observe specific identity positions such a ‘green change agent’ emerging following an ‘epiphany’, or major life change that resulted in managers reconsidering their purpose. They argue that CSR provides a legitimate context for the enactment and expression of such identities.

Most recently, Carrington et al. (2018) also observe that individual activism can lead to positive organisational change as an exception to acknowledged instrumental approaches to CSR. The authors recognise a discourse that highlights the need for internal organisational change yet note that little attention is given to how managers may transform CSR practices. In their work, micro-level practices that may follow a ‘moral shock’ can ‘bubble up to change the field level’. This highlights the significance of individual action in producing change, and contrasts with organisational level analysis that present businesses as a coherent single entity.

Research at the micro-level has therefore focused on the corporate managers who develop strategy, or employees who work within the resulting policies. However, Tams and Marshall (2011) also identify a broader growth in ‘responsible careers’, those jobs where people specifically aim to improve social and environmental conditions, recognising that these roles are understudied relative to corporate workers. Tams and Marshall (2011) further note that such individuals may exhibit ‘biographical reflexivity’ that includes questions about the nature of career success, past experiences at work, the purpose of work, and of commercial and social structures. In this context, micro-level analysis has been used by Ghadiri et al. (2015) to show that CSR practitioners may also use subtle ways to both distance and align themselves with positive and critical aspects of CSR to manage a ‘hybrid’ identity that allows them to undertake work.

In considering individual motivations and desires, much micro-level research draws from sociological frames and issues of identity to reclaim the value of the CSR project through the heroic actions of a few enlightened workers who seek to resolve the tensions that emerge in CSR. Yet these remain exceptions to the more common complicity of those undertaking responsibility work. Aguinis and Glavas (2012) suggest that more research is still needed on the psychological underpinnings of CSR. This directs us towards psychoanalytic approaches to further understand the psychology of CSR, especially given the various suggestions of denial that are highlighted in micro-level research.

Psychoanalysis, Management Research and CSR

The relatively limited use of psychoanalytic approaches to explain the contradictory nature of CSR work is perhaps surprising given the regular calls for a re-appreciation of psychoanalysis in management studies (Fotaki et al. 2012; Molesworth et al. 2018; Molesworth and Grigore 2019). In particular, Arnaud and Vidaillet (2018) argue for the value of psychoanalytic approaches in explaining the apparently irrational, or contradictory behaviours evident in organisations.

Nevertheless, psychoanalytic theory has been used to account for CSR. For example, at an organisational level, Driver (2006) rejects defining CSR in terms of either instrumental or critical perspectives, and instead turns to Lacan’s psychoanalysis to consider how corporations contain multiple identities that inevitably reflect society. When corporations avoid social or environmental responsibilities, it is because they create internal fantasies of both their independence from the world, and their need to maximise profits, that deny identities that relate to wider social responsibilities. For Driver (2006), the task is therefore to reveal such corporate fantasies by considering the degree to which CSR practice is informed by ‘egoic’, or simple fantasy, versus the recognition and acceptance of multiple perspectives in a ‘post-egoic’ sense of corporate self that can recognise the contractions in CSR in ways that are more open to their resolution.

Driver (2017) also uses Lacan to consider the identity work of social entrepreneurs, noting that they blur beatific and horrific fantasies (overcoming and obstacle) to maintain and negotiate both doing good and making money, and so become defined by struggle. Such individuals cling to discourses such as marketisation, or entrepreneurship despite evidence that they fail, because such a belief allows for ongoing heroic attempts to make things work. Social entrepreneurs come to imagine others as in need of their help, and themselves as only able to help through commercial approaches (Driver 2017). By recognising the perpetuation of a comforting fantasy, psychoanalytic frames therefore enable interpretations that do not require a resolution of contradictions between social responsibility and commercial imperatives, and don’t insist that those involved must be cynical. Instead, denial results in ineffective attempts to solve problems, whilst satisfying individual needs to experience oneself as ‘good’. Such critique is not inconsistent with Papi-Thornton’s (2016) interpretation of social entrepreneurs who narrowly define their purpose by focusing on business models rather than systems thinking that may better address the issues they claim to want to solve. These ‘heroprenuers’ seem unable to grasp complete information about their activity, even as they strive to solve social problems.

Cederström and Marinetto (2013) likewise consider identity-preserving denial in CSR through Žižek’s elaboration of the ‘liberal communist’ who fails to observe the antagonistic relationship between capitalism and the social good. And Bradshaw and Zwick (2016) further draw on Žižek and Freud to highlight the nature of ‘not seeing’ and ‘pretending not to know’ that is required in a fantasy of corporate success in saving the environment, despite growing evidence to the contrary. They extend their analysis to suggest that a Freudian death drive may result in managers deriving pleasure from seeing environmental destruction, then replacing the need for urgent action with comforting, partial solutions such as CSR.

Psychoanalysis can help us understand CSR as an apparently paradoxical practice, suggesting that we may not need to label CSR workers as cynical, or hypocritical to maintain critiques about the function of CSR in society. We now consider Transactional Analysis (TA) as an approach that has yet to be used to theorise CSR, but that specifically lends itself to studies of complex relational dynamics that construct Rescuer, Persecutor and Victim positions, denying available information in the process.

TA was developed by Eric Berne in the 1960s in response to the limitations he experienced in counselling work when using Freud’s original approaches. Unlike other psychoanalytic traditions, TA places an emphasis on current relational dynamics as an indication of an individual’s biographical development of personality. In doing so, TA also theorises the positions individuals tend to adopt in interactions with others, including the information available to them that is ignored in order to maintain such positions. TA accounts for differences between interpersonal exchanges based on evaluations of available information and subsequent options to act, and what we (more) often see as unproductive relational exchanges that instead satisfy internal psychological structures. TA therefore provides a metaphorical discourse (cf. O’Shaughnessy’s explanation of psychoanalysis 2015) for exploring the complex relational exchanges that produce the contested outcomes of CSR, whilst seemingly maintaining fantasies of heroes, villains and victims.

Transactional Analysis and Drama Triangle

In TA, underlying relational dynamics reveal themselves through dysfunctional exchanges that Berne (1964) calls Games. In Games, interpersonal exchanges expose how individuals produce what Berne refers to as ‘inauthentic’ interactions based on ideas about the self and others that formed early in life. Stewart and Joines (2012, p. 374) define an authentic feeling as an ‘uncensored feeling which the individual in childhood learned to cover’ in response to those around them. Games therefore produce a re-experience of childhood responses to others as a way of solving problems in present stressful situations (Stewart and Joines 2012).

Although Berne identified over 50 Games, his student, Stephen Karpman (1968) noted that these may be analysed according to a Drama Triangle of three basic roles: Persecutor, Rescuer and Victim. Indeed, it is the switches between these roles that constitute Games as the present fails to conform to re-experiences and individuals seek to reconfirm their preferred role, and that of others (Mrotek 2001). Capital letters distinguish TA roles from society’s actual victims, persecutors and rescuers that are not denied by the metaphor. Berne (1964) and later Karpman (1968) therefore note differences between actual helplessness and how others might be imagined as helpless in order to maintain a superior position towards them.

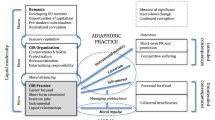

Individuals tend to be unaware that such roles are imagined in themselves or others, and actively suppress information that might reveal their Games to them. In TA then, an unconscious filtering of information creates and maintains a Drama that unfolds to an outcome that confirms beliefs about the self and others. Drama happens because individuals seek an ongoing reconfirmation of a life position as a ‘script’, i.e., a Rescuer keeps finding ways of Rescuing, ensuring responses from others that produce acceptable existential recognition of an existing belief system. Karpman therefore highlights the ultimately stable structure of TA relational dynamics (see Fig. 1).

Early patterns of interaction influence scripted patterns of current relationships. Victimhood results from internalised patterns of childhood interactions that were characterised by helplessness and powerless behaviour (Mrotek 2001). The Victim then seeks confirmation of an inability to autonomously solve problems (Stewart and Joines 2012). Persecution draws from internalised patterns of childhood interactions with parents based on demands, threats, and rule enforcement that result in blaming others for problems (Mrotek 2001; Stewart and Joines 2012). Rescue also draws from early parental interactions that recognise problems in others (rather than oneself), often by professing superior knowledge (Mrotek 2001) and offering help only to feel better about oneself (Stewart and Joines 2012). Each position denies full processing of current information and related responsibilities that are free from the scripts produced early in life. Although Berne notes that early patterns of experience (authority, playfulness, and helpfulness) may sometimes be useful in adult life, he observed that failures to solve current problems are usually caused by mis-deploying such scripts.

TA also explains how information that would deny Drama comes to be ignored through ‘discounting’. Discounting is a continuous process, rather than a singular repression of information, determining what is noticed and ignored in one’s own thoughts and actions, those of others, or the context. In this way, discounts can be spotted as they happen in the selective attention individuals give to social exchanges. Discounting means misrecognising information as relating to the relational dynamics of a Drama Triangle to maintain fantasies of Persecutor, Rescuer and Victim positions, rather than addressing the concerns at hand in the most effective way.

Broadly, Victims discount their own abilities, and even themselves as worthy of attention; Persecutors discount others’ values, dignity and rights, and; Rescuers discount others’ ability to think for themselves and be independent (McKimm and Forrest 2010). In particular, Steiner (1990**) distinguishes between positive, authentic helping experiences from the destructive or pathological ones, which he calls ‘Rescue Games’. According to Steiner (1990, p. 146), people who play Rescuer actually ‘believe that people who need help can’t really be helped and that they can’t help themselves either’.

A key development in TA is how we understand discounts, and Mellor and Schiff (1975) review the types (stimuli, problems and options) and possible modes (existence, significance, change possibilities, and personal abilities) of discounting in a matrix (see Fig. 2).

Each box may be applied to any area of discounting (self, others or context) with the highest level of discount starting in the top left corner. Diagonal arrows illustrate that one discount will entail the other. In addition, a discount on any diagonal also results in a discount in all the boxes below and to the right of that diagonal (if we don’t recognise a problem, we also can’t see its significance, that it is significant to us, that there is a need to solve it, how it might be solved, or our ability to do so).

Discounting avoids dealing with internal anxieties or conflicts that are activated by current events, and so avoids taking responsibility for one’s actions (Stewart and Joines 2012). Dramas are the manifestation of this process and are repeated to confirm a life-position (Mrotek 2001), disconfirming aspects of current reality (Berne 1964; Harris 1968; Karpman 1968; Steiner 1974). Discounts are therefore not abstract ‘not knowings’, but specific and situated denials, manifest through interactions with others and used to maintain a fantasy of the world, others, and the self-scripted early in life. Such denials by managers will also be reflected in the way in which meso or macro-level practices are assembled. So, although Carrington et al. (2018) argue that micro-level acts of individual managers have the potential to generate organisational transformation, according to TA, dramatic micro-level interactions and related discounting may also be mirrored onto the organisation or even a nation, resulting in an inability to change, consistent with Driver’s (2006) view of organisational fantasy.

Although TA was developed for use in therapy, in its 60-year history its application has been extended to analysis of systems (Harris 1968). TA has been applied to organisations to understand how internal interactions shape different cultures (Bennett 1996, p. 199), marketplace relationships to understand the Games people play with brands (Molesworth et al. 2018), nation states to explore how conflicts are perpetuated by underlying national life scripts passed on from one generation to another (Campos 2014, 2015), and political economies to help imagine alternative social orders that could lead to more responsibility and dignity (Mihailovic and Mihailovic 2004). Through these extensions, theorists have further established how relational exchanges both draw from cultural resources and reproduce the narrative stories that circulate and sustain the social level, e.g., the myths of helplessness and the status of the hero. Hence when a group is cast as Victim, individuals in that group may reproduce it, or challenge it, in line with their own Script. Importantly, in TA we can recognise such psychological work in dramatic stories people tell of dealing with others.

Methods

Our approach recognises the need to theorise CSR through the experiences of practitioners (Carrington et al. 2018; Pedersen 2010; Wright et al. 2012) and is based on an extended engagement with CSR practice in Romania. We aim to understand: (1) the relational dynamics of CSR activity, and; (2) how these relational dynamics explain contradictions between the positive intent of CSR and observations that it is frequently ineffective at addressing the issues it claims to be about.

Whereas both Wright et al. (2012) and Carrington et al. (2018) focus on managers selected for their resistive or activist activities, in contrast, we interpreted everyday CSR work. Wright et al. (2012) and Carrington et al. (2018) also focus on managers in developed countries who may have greater resources from which to draw their activist subject positions than those in developing countries such as Romania. Many critical studies have drawn from work in developing countries (Akpan 2008; Brei and Böhm 2014; Gilberthorpe and Banks 2012; Yu 2009) and our context is closer to these.

Borţun (2015), for example, defines Romanian CSR as little more than a PR strategy that allows corporations to deflect public concerns, whilst neglecting meaningful engagement with stakeholders. In this context, multinational companies lead CSR with small local CSR teams (often as part of marketing, communications, or PR) working with local NGOs who gain few funds from public donations, and so rely on these corporate partnerships. In early 2016, when data generation was completed, there were 45,000 NGOs in Romania and an increase in their financial sustainability due to corporate donors (USAID 2019). Hence NGO workers undertake much of the CSR work in Romania, with or for CSR departments.

When recruiting those in responsible careers, we therefore spoke to more NGO workers than CSR managers. Position titles include founding director, director, president, coordinator, executive, CSR manager or specialist. Participants were recruited through CSR networks and events in Romania and from personal networking. Thirteen participants were working for companies, and thirty-four for non-profit organisations. Sectors included finance, cosmetics, FMCG, technology, or consulting, and non-for-profit organisations that supported health, disadvantaged groups, and the environment. We conducted forty-seven interviews in participants’ offices or in coffee shops, between 2013 and 2016, each lasting between 40 and 140 min.

Interviews allowed us to ‘mobilize interpretive repertoires’ (Gill and Larson 2014, p. 528), providing rich descriptions of participants’ recollections of CSR-related projects, and their relationships with partners, government administrators, and beneficiaries. Participants were asked open questions about their current activities, who they work with, and the outcomes of their work. We encouraged participants to tell stories that were important to them (Driver 2017), prompting them with questions such as, ‘Tell me about your organization and your work’, ‘Tell me who you work with’, ‘Tell me more about CSR projects and their outcomes’.

All interviews were conducted in Romanian, were recorded with participants’ permission, then transcribed and translated into English to allow the non-Romanian speaking members of the research team to review the data. Notes that captured additional non-verbal cues such as raised voices, laughter, expressions of emotions, and hesitations accompanied transcripts.

Data Interpretation

We started by exploring business–NGO relationships in CSR. Then, recognising that stories frequently took dramatic turns, we focussed our attention on the drama. This is similar to Jamali et al. (2017) who re-purposed their analysis when they observed unexpected discrepancies in data. Initially, analysis was iterative, going back and forth between the dataset and individual accounts (Charmaz 2005; Costas and Kärreman 2013; Tams and Marshall 2011) to identify themes and consider alternative conceptualisations. This pointed to the dramatic structure of CSR work, where participants told us about those they helped and how they helped them, but also how beneficiaries were persecuted or neglected, including the naming of those seen as responsible for societal problems, especially politicians and government agents.

We then explored enabling theories that could account for such dynamics, and TA presented itself as able to provide a plausible explanation, i.e., we use TA to interpret and theorise, rather than as a therapeutic tool. The Drama Triangle focuses attention on how actors articulate different positions in CSR work. The Discounting Matrix then points us to the mechanisms that account for what participants don’t seem to acknowledge (Mellor and Schiff 1975; Stewart and Joines 2012). In line with previous psychoanalytic approaches to organisation studies (Driver 2017), our interpretations do not intend to offer proof, suggest causation, or allow comparison (for example between different job roles, or industries), but rather present an explanatory metaphor that results in both insight into, and reflection on, the contradictory nature of CSR work.

Drama may be identified by listening to accounts of experiences, as people tend to fall back on dramatic stories that reveal their self-confirming scripts (Stewart and Joines 2012). The stories we heard therefore reveal how CSR workers understand their role and that of others, and work to maintain them. For example participants may state: ‘They were helpless’/‘I needed help’ as expressions of Victimhood, ‘They caused the problem’/‘I had to put them right’ as statements of Persecution, or ‘They needed my help’/‘I helped them’ as accounts of Rescue. Here, we also recognise that accounts of the words and actions of others represent the understanding of our subjects as they construct these positions and we present them as such, rather than as accurate descriptions of what others actually said or did.

Discounting can be inferred from how individuals construct and express their accounts. Stewart and Joines (2012) provide guidance on how to identify discounts through expressions like ‘I cannot’, ‘It’s not possible’, ‘This is how it is’, ‘I had to’, or non-verbal cues, most obviously ‘gallows laughter’ at events that would not usually be seen as funny, and we observed these in the data. We also followed Mellor and Schiff’s (1975) approach by considering what participants make absent in unfinished sentences, and/or confusing, contradictory, incongruent, or hesitant statements. Stewart and Joines (2012) also highlight behaviours that indicate discounting: ‘doing nothing’ (instead of taking problem-solving action); ‘over-adaptation’ (compliance with what they believe others want); ‘agitation’ (engaging in purposeless, repetitive activity), and; ‘violence’ (discharging energy destructively).

We looked for these cues in accounts, cross-checking transcripts with recordings and notes to identify any mismatch between words and tone, or between the content of what is said and inappropriate laughter. We further noted contradictions within participants’ accounts. Illustrative data on Drama Triangle positions is shown in Table 1, and switches in positions and discounting are shown in Table 2.

We recognise that readers may find our reporting potentially judgemental (for example, where we suggest a Persecutor or a Victim position). We qualify this by confirming that our impression of participants was of professionals who were keen to improve Romanian society. We therefore encourage the reader to focus on the metaphors deployed to account for CSR practice, and not on the individual participants who gave generously of their time and spoke openly of their life and work. We therefore also ensure anonymity by removing references to names, job titles, companies or beneficiaries, and by avoiding direct quotes where issues are especially sensitive. Where we quote participants, we disguise identities, including by changing genders, consistent with the way Yalom (1980) presents stories through symbolically equivalent substitutes.

A Transactional Analysis of Romanian CSR

We now present three illustrative accounts that cover enduring social issues in the country: disadvantaged groups, health and the environment. The stories have been selected to illustrate how CSR work does not address its stated social goals, despite the intentions of participants. In each story, we identify Drama Triangles involving Victims, Rescuers and Persecutors (irrespective of actual victims, their persecutors and those that help them), highlighting how these internal constructions discount information about the context, others or the self. In showing how CSR unfolds as Drama, we reveal participants’ knowledge of both instrumental and critical positions towards CSR, without the need to accept or reject either. Unlike much critical work that considers large-scale projects (Gilberthorpe and Banks 2012; Jamali et al. 2017), our stories deal with the ‘everyday’ undertakings that represent CSR activity in Romania. In these accounts, we also found little evidence of the transformations seen by Carrington et al. (2018) or Wright et al. (2012). We don’t reject their observations, but rather suggest that alongside these exceptional cases, people undertaking CSR work do more discounting than actual transformation.

Helping Economically Disadvantaged Groups

Alan is an experienced NGO director who works with disadvantaged social and ethnic groups. This is an enduring problem in Romania and one that the government has failed to solve (Stănescu and Dumitru 2017). Alan explains that disadvantaged groups are persecuted by both government and businesses who are generally ‘unwilling’ to support them. Nevertheless, he is proud of his ability to secure corporate funding and many stories he tells revolve around this. Alan presents his NGO as a solution to Romanian problems because of his ability to extract funds from corporations, discounting their role and that of government, and frequently discounting the beneficiaries who are presented as largely passive. He tells us what happened when the CEO of their biggest corporate donor changed:

Paul [the new CEO; name changed] comes and looks at the finances and says: ‘Why do we give so much money to this NGO? Let’s cut the funding’. All NGOs in Europe began to tremble…But before they cut funding, they said that they’d come to Romania. All the pressure was transferred onto us. We said, let’s take them to Scurtesti [name changed] where they can see a monastery, we can show them the beneficiaries. Paul might cry a little bit in there…But there was nothing from Paul, nothing moved him.

Alan presents a Rescuer to Persecutor switch in the corporation to prompt a Drama that affects NGOs that rely on donations. NGOs in turn become Victims, risking Alan’s Rescuer role if corporations cut funds. Alan response is to try to influence Paul to restore funding, Rescuing the NGO. His narrative is similar to Driver’s (2017) analysis of social entrepreneur struggling against adversity, drawing on internal resources to re-achieve their Rescuer position, but we can also note the specific discounts necessary to achieve this role. Alan’s frustration at the CEO’s decision to cut funds and his determination to restore funding are discounts at T3 level, the existence of other options to feel and act differently. This also discounts the changeability of stimuli, i.e., that there may be other ways to fund the NGO (T3). In turn, this discounts the significance of problems, for example, the corporation may have good reason to cut funds, such as financial difficulty, or may have decided there are better ways to undertake CSR, or indeed better NGOs to work with (T3, see Fig. 2). Alan’s Script requires action to restore Paul’s funding, switching to Persecutor to achieve this as manipulation of Paul is a discount of his dignity, and so a positioning of him as Victim. Alan continues:

The next day, we took Paul to [a different beneficiary’s] home, a family with young children….We told the story of the family: how their father was working in the UK to make money, and their mum only earns 2-300 lei per month [£40-60]. While we were telling the story, the boy who understood what was said and who was missing his dad, was about to cry. We all saw tears in his eyes - all of us - it was a very solemn and serious moment. We all felt ashamed, bowing our heads.

There is compassion and expressions of shame, as instrumental issues of funding and CSR activity give way to the moral emotions of the situation. This seems to reveal real victims and the potential to help, yet almost as soon as Alan recognises it, he changes the topic, discounting the significance of stimuli (T2) and so also that there is a problem, i.e., the shame experienced. Alan tells us that Paul offers his own money to help:

Paul comes to me and says: ‘How can I give £3,000 from my own money to build a park in this community?’[…] I was in such a state, and I was thinking at the time: ‘Old man, just leave the millions to flow to us, and I’ll make the park from other funds’.

Alan’s focus returns to the corporate donation to the NGO. He rejects Paul’s personal offer (another discount of significance of stimuli, T2), in favour of frustration at the thought that corporate funds may stop, which signals discounts of others’ feelings and actions, i.e., discounting Paul’s spontaneous moral response to the problems he saw, and to the immediate benefits to the family and community this could bring. Alan denies Paul an opportunity to personally and immediately help. As we listen to the story unravel, Drama roles change rapidly:

Instead, I got Paul to sign the [corporate funds] contract and he gave us the money…Every time I tell the story, I get goose bumps! And I’ve been telling it for more than five years. This is the story that helped me raise millions [of lei]. I made history with Paul. If people spend any time with me, I will tell THIS story, because this is what audiences want to hear.

The focus isn’t on supporting disadvantaged groups, and in the end the situation is where it started, with funding restored. Once this dramatic loop is closed, Alan returns to a Rescuer position, gaining external recognition and the pride of CSR funding success, i.e., seemingly solving a different problem than helping poor communities. Indeed, Alan states that it is the drama of achieving success in funding that people want to hear about (not the actual benefits to the community). Beneficiaries are presented as passive and powerless. For Alan, their agency is discounted as their role is reduced to helping secure funding.

Alan explains how little is done to support disadvantaged groups. Then in a later story he tells us of another funding crisis, this time because but the marketing department of the same corporation refused Alan’s request for funds because they spent the budget on advertising. He tells the story with ‘gallows laughter’, about how he had to ‘step over colleagues in the NGO and in the company’ (another switch to Persecution). He then explains how he emailed Paul photos of children playing, to ensure that Paul approved the donation. Alan switches from Rescuer to Victim, then to Persecutor, and back to Rescuer in a typical pattern of a Drama Triangle. CSR gets done without significant progress, but in Alan’s story with actors playing their parts in maintaining a Drama of overcoming inconsistent corporate sponsorship. The precarious nature of funding, the need for an NGO intermediary, and the limited success through this approach remain, and Alan seems unable to extract himself from this relational dynamic by considering other options (for funding, helping disadvantaged groups, or changing Romanian society).

Providing Medical Aid

Tony is a CSR manager for the Romanian office of a global fashion brand. He has been involved with various projects related to health. Healthcare in Romania is underfunded and access to treatment is precarious. According to Murgu et al. (2017), 73% of Romanians have a negative view of healthcare in the country, and so there is considerable opportunity for CSR projects in this area. Tony tells us about the various hospitals that have received equipment via the corporation’s CSR projects, first explaining why CSR is so important to him:

[CSR] is an idealistic job. Beyond just earning a living, or making a career in this job, you have a strong social involvement and can determine change around you. These are the main motivations of someone in CSR. They are not just a professional like others in marketing, they can influence change.

Tony adopts a Rescuer position through his CSR work, stating the importance of positive change in Romania and so expressing his internal fantasy, or Script (note the ‘idealism’ here). Yet he can’t seem to access such information as his stories unfold:

I have also broken partnerships…because I considered they weren’t…they didn’t bring added value for us…they were just a waste of time and budget. For example, since early 2000s when we launched the campaign against cancer, we worked a lot with [named NGO]. They had this campaign […], my colleagues from back then had made a partnership with them and started raising money in their accounts. After a while, I realized that we had no control over that money, we had no reports, and although we were saying to everyone that [we are] doing this campaign, people asked us: ‘what are you doing exactly?’…because they didn’t feel anything…

As Stewart and Joines (2012) note, hesitations, pauses, and contradictions point to discounts, and we see how Tony struggles to articulate corporate value for money as a reason for dropping a project, despite knowledge of its value to society and his own previous position. It’s literally hard for him to explain the corporate priorities for CSR. Tony switches back and forth between highlighting beneficiaries, then customers as a priority, but ultimately noting the instrumental needs of the organisation as most significant. Later, he gives another example about how he stopped funding for an NGO: ‘I refused to route money their way or fund any project, because there was no reporting, I felt like it was a black hole that sucked in money without an actual return’.

Here, Tony discounts his ability to react differently (to work with the NGO on reporting), the solvability of problems (finding ways to develop effective communication about the projects) and significance of options (the contradiction that cutting funds diminishes support for health in Romania), and instead he maintains an instrumental position to CSR activity despite initial claims to want to change society. These are discounts at T4 level that sustain a Drama Triangle as Tony moves between Rescuer of beneficiaries, then Persecutor of various NGO partners that are dropped. He states:

I always try to explain that the money we donate isn’t ours - although in a fiscal conception [we are] donating - but a part of it is collected directly from the customer through the CSR dedicated products. And if I were to borrow some money from people, so to speak, they’ll say: ‘Ok, I want to support this cause and I want you to show me what you did afterwards’ [….] I have to account for this money to the customer, not because we have an internal CSR reporting procedure…although we have that too...

In Tony’s accounts, pauses and contradictions fragment his narrative. The money comes from customers, but then he immediately notes that it is actually a corporate donation, as though a direct consumer donation to a cause creates some risk to CSR (a discount of viability of the option of direct donation, T5). He also highlights that CSR is only produced through ‘dedicated products’, revealing the limited and instrumental nature of CSR, then immediately moving away from that aspect of his work. There is also a contradiction over what reporting is for. Instrumentality is recognised, then ignored.

Rescuing through CSR also fails to account for the numbers helped. For example, Tony highlights the gulf between the number of Romanians needing a medical test (8 million) and the number of tests done (60,000). This demands Rescue by the corporation, yet their support amounts to only 2500 additional tests before the money for the project runs out.

So…60,000 for several million people, around 8 million is the last report, so we’re talking a very, very small number. That was the moment that we decided to base our communication on the statistics the Institute offered us and start a free [test] program together with the [named NGO]. […] everyone was enthusiastic by the fact that we finally succeeded to have a direct campaign. In a month, we had 5,000 people signed up on the site who fit the conditions….We had 2,500 [tests] available and 5,000 registrations...you couldn’t have told them at the time: ‘Ok, you don’t get one because you registered on Wednesday instead of Tuesday’… it was very difficult to take a decision about the rest, we ran out of money…

Even though Tony first recognises the existence of problems and the significance of stimuli, he then discounts the significance of problems (how much testing is actually required) and so the existence of options (to fund more tests) and changeability of stimuli (to change Romanian healthcare systems) in favour of achieving organisational CSR goals. These are discounts at T3 level. Rescuing stops when there is no more money to offer tests, revealing that CSR can’t solve the problem. Like Alan, at the end of this account Tony seems to have a moment of reflection on the significance of the campaign, but then blocks this out, highlighting the dynamic nature of discounting by immediately ignoring the stimulus of the scale of the project (T2).

In another story, Tony illustrates how Drama can result in CSR departments switching between Rescuer and Persecutor, then ending up as a Victim, before realigning donation decisions to re-achieve a Rescuer position. Again, although the Drama seems to tell of the precarious nature of CSR success, it also serves to confirm each actor’s positioning in a Drama Triangle. The project is to provide equipment to hospitals in a Romanian city. Medical staff are narrated as Victims of Persecuting government officials who refuse appropriate funding and instead pursue their own interests. Hence hospitals need corporations to Rescue them. Patients remain absent from this account, and so are discounted here in line with how the corporation reports their CSR activity (as providing hospitals with equipment). The story again turns to corporate promotional activity. This corporate requirement causes the initial drama, yet it is then actively disregarded in the narrative:

We agreed to donate medical equipment for the city…All we’ve asked of the council was to let us have an event in the city, to give us a specific location…and on Friday [before the weekend event], they told us they’re moving us somewhere else… Imagine that! It was a big frustration because they didn’t understand that we were doing something for their town; we weren’t doing it for the company…at one point I was thinking of telling them…‘We’re no longer making the donation if we don’t get our location’.

The potential risk to promotional activity results in Rescuer switch to Victim, with city hall becoming Persecutors. The immediate response is then to imagine withdrawal of donation, switching from Victim to Persecutor. Despite initial claims about changing society (which again are put aside), Tony maintains an instrumental position to CSR activity, discounting the ability to react differently (to accept the location rather than experience frustration), solvability of problems (to work with the new location) and significance of options (that the loss of the preferred location doesn’t actually undermine the CSR work); discounts at the T4 level. Tony discounts the difference that the donation can make in the community, and indeed the commercial purpose of the project, preferring to narrate that he was ‘doing this for the town’, at the same time as demanding a venue for promotional activity. This position ensures Victimhood that confirms a view of local officials that is negative, and illustrates how discounting works as a dynamic process of ignoring information in favour of a scripted position. Tony knows that the purpose of the CSR project is promotional, and even states it, then ignores his own admission to maintain a story of Rescue.

The venue was changed to a less visible one, and Tony declares the project a failure, confirming that politicians are the real source of Romania’s problems. Yet he then tells us of other successes that re-confirm the value of his CSR activity. Tony is attempting to solve a different problem (corporate reputation) other than the one claimed (medical aid). He ignores the limited impact of campaigns despite knowledge of the extent of the problem and also stops funding when the CSR results are unclear or too low.

Protecting the Environment

Sarah is a programme co-ordinator of an established Romanian NGO. She works on various environmental projects, including with communities in ecologically sensitive areas of Romania that the government often leaves under the control of NGOs and social enterprises (Manolache et al. 2017). Sarah explains the importance of NGOs in Romania and emphasises a Rescuer role, explicitly expressed in terms of the satisfaction that the NGO worker gets:

There are ten to fifteen NGOs in Romania who are publicly known. And they’re led by passionate people who don’t stay for the money; who think of other things, not just the money at the end of the month…They get the satisfaction of doing something helpful for everyone. And they really do. The public machine is down in Romania. Without NGOs, we don’t achieve anything at all!

She explains that Romania has significant natural resources, but little environmental protection from the state, and describes her struggles as an NGO worker. For Sarah, the environment needs to be protected so that Romanians (the passive Victims that she speaks for) can continue to enjoy it. Corporations involved in logging, mineral extraction, and agriculture are presented as Persecutors, along with the government that persistently fails to legislate to protect the environment.

The Romanian authorities […] have other objectives than what is written in their job descriptions…it’s very difficult to work with them […] They have another agenda…The [ministry that the NGO mainly deals with], it’s a front for the scams run in Romania regarding environmental protection […] There are all kinds of shady things getting authorized by this ministry […] That’s why I work here! We try to solve these issues.

For Sarah, NGOs must step in because the government not only fails to act, but is corrupt, and so causes the problems. Yet her need to present the NGOs as Rescuer also results in her positioning of corporations as Persecutors, despite the fact that her NGO routinely benefits from corporate donations. Sarah gives an example, explaining that during a project to support people living in a protected area in Romania, she had a disagreement with a potential corporate partner. She is approached by a representative of a bank who wants to provide gifts to those in a remote, environmentally sensitive area:

A woman from [the CSR department of a bank] wrote to us saying she wants to send some gift donations to [the beneficiaries of the NGO as a CSR campaign]. And we said: ‘Oh, how nice, very beautiful!’…And she said: ‘How much would it cost?’ […] And we gave her some figures and told her: ‘First of all, there must be someone responsible from our end on this, there’s a month’s worth of activity […], then there are costs for transportation, etc’… We then met, and the lady who had approached me, rolled her eyes: ‘Oh my, you pay someone!? [in the NGO to implement the campaign] In that case we can do these things ourselves!’ And I said: ‘So why don’t you do it yourself, madam in charge? You think we work bare feet, on an empty stomach and we can fly too?’ [This is a translation of a Romanian expression that means that you can’t work for free; salary and expenses need to be covered]. [The NGO Director] told her: ‘You’re asking us about salaries? Aren’t you ashamed of yourself? You…working at a bank accused of fraud [referring to a recent scandal]’.

In Sarah’s account, the bank presents itself to her as a potential Rescuer, but apparently switches to Persecuting a potential NGO partner for refusing to cover the implementation costs of the proposed CSR campaign, so ensuring the bank avoids the full costs of the campaign. This results in the Drama. Although in the story, the representative from the bank is described as discounting the needs of the NGO, Sarah then describes an immediately switch to Persecuting the bank, in turn discounting their position. The result is that the donation doesn’t proceed.

The drama unfolds without consideration of the beneficiaries themselves who are made absent. In turn, Sarah switches to Persecution, attacking the reputation of the bank (which is the reason for their CSR in the first place). Sarah discounts the bank’s ability to solve the problem (maybe their funds are limited) and viability of options (they could compromise or work on a different project). These are discounts at T5 (see Fig. 2). She also discounts own ability to act on options (T6), preferring scripted indignation and Persecution over understanding and negotiation. Again, the outcome is that the problems faced by the community are not solved.

In a later interview, Sarah explains her desire to help develop a nature reserve in a major city, describing the lack of access to nature afforded to the people of the city and the detrimental effect this has on their lives, positioning them as passive Victims in a selective way, and in this case also discounting other problems (unemployment, limited social care structures, crime, etc., all of which are reported locally, including the city council’s apparent inability to solve them). However, she then tells us about her failure to get local council support, starting with a statement about the instrumental nature of such projects, and this time with a switch to Rescue the politician involved:

We said: ‘Mr. Mayor, we have an extraordinary project, if you support this project you can win the election for president!’. But these politicians don’t understand the value of such a project. They only look at a project if it comes with an envelope containing a 200,000 Euro bribe, and you give it to him like in the mafia movies. And he takes it and says: ‘It’s agreed’.

Sarah states a wish to help the mayor, then immediately defines local politicians as corrupt, confirming her positioning of herself as a Victim of Persecuting politicians. This discounts their dignity, their ability to help solve the problem (politicians only act on bribes) and viability of other options (is a bribe really the only way to make things happen?). Again this is the T5 level. Sarah makes it clear that there is no actual bribe in this case, but also describes how organisations can’t achieve results without paying bribes. Sarah further expressed the helplessness, seen in the Rescuer to Victim switch with failure attributed to public officials:

When I go to the city hall, they say: ‘What a wonderful project!…But it’s nothing to do with us, go to the other office because we can’t make this decision’…They throw you from office to office, ‘No, go to the other one’, ‘Well, he just told me that you…’ ‘No, the law says otherwise’…, and we’ve been struggling like this for some time.

The repetition of struggle suggests a TA Drama. Sarah persistently fails to gain support but is able to confirm the Persecutory nature of officials and her own Victim status as she tells the story, both of which lead to her re-stating the pressing need for her NGO do its work, i.e., a return to a Rescue script.

In a follow-up interview in 2016, Sarah has started a new NGO to progress the nature reserve project, and tells us of further visits to public officials, the complex bureaucracy involved and her ongoing struggles, yet she has still to make significant progress. The NGO Rescues because of the persecution of government. Corporations donate, but they too must be presented as Persecutors, unless they directly support the NGO. Yet there is little progress in protecting the environment.

Although we did hear stories of limited success, participants overwhelmingly tell of an overall failure to solve Romania’s social problems. Their focus, however, remains on funding and accountability as the ‘problem to be solved’.

Drama and Discounting in Romanian CSR

TA does not reduce responsibility work to a single process of establishing an individual as a Rescuer but reveals that Rescue must be repeatedly reproduced when challenged by contradictions of CSR. It allows us to plot relational Games and their related scripts, including ‘grasping victory from the jaws of defeat’ (Alan’s repeated story), but also failed Rescue (Sarah’s and Tony’s stories). All involve discounts within a stable Drama Triangle, where the focus is CSR work itself (rather than beneficiaries, or public policy). Discounting prevents participants from exploring alternative options in their work, their partnerships with others, or in how Romania is governed.

Dramas represent the sense making of participants as they highlight what is important to them in their experience of working in CSR. As Hawker (2000) explains, positioning others as Victims that (only) you can Rescue always means entering a Drama Triangle. Romanian CSR work involves selectively constructing passive, and often voiceless Victims from various parts of society that are underdeveloped (in our stories economic disadvantage, health, and the environment). In turn, both officials and those corporations that are not involved in a Rescue, are presented as Persecutors (Fig. 3).

Despite a lack of achievement and/or instrumental results, our participants continue to believe in what they do, even as they are unable to see a Victim’s ability to help themselves, or to be better helped by others, to see their own Persecutions and Victimhood, and/or to see the reality of the limitations of the political system in Romania. We capture the potential discounts in CSR in Fig. 4, drawing from the work of Mellor and Schiff (1975).

At the T1 level, a manager would discount that there is even an issue in Romanian society, negating any need for CSR (or any other programme of development). The acknowledgement of environmental and social issues is accepted though. Indeed, acknowledging stimuli is necessary for issues to be consciously brought into stories about CSR. Discounting at the T2 level would mean failing to recognise an issue as a problem (‘there is always unemployment, the environment always changes’, etc.). Again, our stories suggest that CSR workers may recognise that the problems in society are significant and that businesses are responsible in some way. Yet the result is the construction of CSR programmes that protect capitalism even as NGOs are critical of corporations, or as Devinney (2009) suggests, create a myth of the good corporation as a Rescuer and in the case of Romania only in collaboration with NGOs.

Through such responsibility work, the reality of Romanian social and economic structures is not confronted, and so societal problems are solved at the wrong level. As Mihailovic and Mihailovic (2004) note, the discounting of problems caused by a political economy denies more responsible social structures. For example, the inability of a government to effectively regulate corporate activity is turned into Persecution of the government, so that ‘good’ corporations can save the vulnerable from politicians through CSR. More fundamental problems with capitalist structures may therefore still be discounted, and manifest as a desire to legitimise business rather than confront the role of businesses in Romanian social problems. Problems with the political economy are discounted at the T1/T2 level (unregulated capitalism is a problem, it directly impacts on the issues NGOs and CSR campaign try to deal with, and its role is significant). The result is that our participants recast problems in terms of NGO funding and CSR results, rather than in the substantive changes that are claimed to be the purpose of such activity, or broader changes in social structures.

At the T3 level, the significance of problems is again often acknowledged, but then discounted (i.e., the scale of the health problem justifies a CSR campaign, but the campaign itself makes very little difference), as are options to change. For example, there may be a claim that: ‘Although there are problems caused by business in society, these can’t be avoided’. We further see this in the ability of NGO work to both position corporations as Persecutors, then work with them as the only option for funding. At the T4 level, those involved might recognise options for addressing problems, but discount their significance, claiming: ‘Even if things were done differently, it won’t make any difference’. Here, it’s not just the significance of options that is discounted, but also that problems can be addressed. At the T5 level, the CSR worker might recognise that it is possible to do things differently but discount the ability for businesses or government to change: ‘You can’t change the ways society operates now, they’ve been like this for too long’. The tendency with discounts is to dismiss the possibility that officials, managers, or even beneficiaries might think or act differently.

Finally, at T6, the effectiveness of the responsible worker in implementing options is discounted: ‘We’ve been trying to change things for a long time, but we just haven’t been able to’, and we see this in the repeating failing of some of the reported projects. Overall, the tendency is to solve problems in ways that maintain the positions of a Drama Triangle, and to ignore information that might challenge this. Hence, we observe a lot of effort going into CSR projects, without significantly addressing the issues presented. CSR work doesn’t need to be cynical; it is just directed towards maintaining stable, but inauthentic relational dynamics, discounting anything that might challenge these.

It is possible, as Stewart and Joines (2012) note, that discounts are derived from misinformation, or ignorance, yet our experienced participants are knowledgeable about both the organisations they work for and with, and the issues in Romanian society they are claiming to address. They also understand how CSR works, yet also seem to accept an absence of change even as they seem to struggle for it. This suggests that many in responsible careers may not be prepared to invest themselves fully in change, to accept their discounts, and to actually do something about them. This represents an unconscious retreat from taking responsibility. CSR allows participants to avoid thinking about the alternatives that are available (see Devinney 2009), whilst securing their Rescue script. Dramas ensure that these scripts can be maintained.

The Broader Significance of TA in CSR

We can transfer this reading of CSR to previous case studies and CSR more generally. For example, in Brei and Böhm’s (2014) study of Volvic, a corporation is presented as Rescuer ‘helping’ the poor in Africa through CRM, but discounting the actual causes of water poverty, and so solving the problem on the wrong level. As Brei and Bohm point out, direct donation would be a better way of addressing water poverty. Yet the authors don’t doubt the charitable feelings of the consumer or the companies, and neither do we doubt the good intentions of our participants. Discounting means we don’t have to believe that those working on CSR are cynical, only that they are unable to acknowledge the change possibilities in front of them, as it would mean confronting aspects of society that they themselves feel unable to deal with, and so also their own limitations in accepting responsibility. Jamali et al. (2017) also question whether CSR in developing countries actually improves the conditions of beneficiaries, noting institutionalised power-relations that legitimise CSR whilst ignoring other voices. This can again be explained by discounting. CSR practitioners are unable to recognise or act on the information in front of them as they maintain a Rescue position within their corporate culture. Indeed, Berne (1964) explains discounting as a form of powerlessness derived from being stuck in a script that doesn’t allow individuals to see options for themselves, or others. Powerlessness is most obvious in a Victim role, and CSR may be an especially attractive career for those who unconsciously seek to fail in helping the society, no matter how hard they try.

We may further reflect on research that considers the individuals that work to produce organisational change. In theorising abdication, Carrington et al. (2018) present something close to discounting where managers deny their own responsibilities or ability to affect change and project this onto others. ‘Unconscious abdication’ is reported as experienced with little moral dissonance. They further note the need for ‘intricate cognitive gymnastics’ in conscious abdication. In both cases, information is disregarded because paying attention to it may change behaviour that an individual is committed to, with discounts by unconscious abdicators happening at a higher level. They also note those occurrences where activists do attempt to change organisations. A key mechanism for this is ‘moral shock’, not inconsistent with Wright et al.’s (2012) managerial epiphanies. Such exceptional occurrences result in a breakdown of discounting and may be rare and temporary (they were sought out through participant recruitment in both these studies). Alan seems to experience moral shock when confronted with a crying child. This creates a capacity to recognise information that was previously discounted; yet Alan then works to deny such information. The actors in CSR drama are not ignorant, or immoral but rather are unable to escape a script.

Wright et al. (2012) also provide a narrative of identity continuity: that people write their own life-script given their experiences. TA does not deny this, but recognises that early interactions determine the sorts of scripts people may write for themselves and which must subsequently be narrated within a specific social context (see Molesworth and Grigore 2019). Wright et al.’s (2012) description of comic, tragic and romantic, and heroic and epic experiences, with the depiction of transformation, epiphany, and adversity—the full range of positions and outcomes required in a TA Drama—may be seen as a mechanism by which the social world and change are constructed, but TA reverses this to say that social realities are the resources through which individuals achieve repeated internal Drama. Hence, both internal and external change relies on the degree to which discounts are acknowledged and challenged. For example, some of the Wright et al.’s (2012) interviewees frame initiatives around conventional business thinking, discounting higher-level change possibilities, whilst others express discounts by saying ‘you kind of switch off, you look at the horrors of it all, you kind of need to get over that’. To create a coherent sense of heroic self requires discounting that accommodates conflict and incongruity. We might easily imagine the internal CSR departments of developed countries (where NGOs are not the focus of CSR project) becoming embroiled with similar Dramas to the ones that we describe and we could further relate this to the work of Papi-Thornton (2016) on the problem of the ‘heropreneur’ who doesn’t actually set out to change society, but reproduces themselves as the hero they feel they ought to be through existing organisational structures and approaches, discounting high-level change possibilities whilst seeming to recognise social problems.

Much of our analysis is also consistent with Driver’s (2006) presentation of corporate fantasy, with Cederström and Marinetto’s (2013) evaluation of the liberal communist, and with Bradshaw and Zwick’s (2016) recognition of a determination to maintain the Capitalist Realist possibility of CSR Rescue. Indeed, we note the possibility that the broadest role of capitalist structures in causing social and environmental harm remains a high-level discount for those working in CSR, and that instead CSR involves presenting ‘good’ corporations as what Yalom (1980) calls a ‘Universal Rescuer’—the imagined ultimate solution to all the problems individuals are unable to accept and take responsibility for.

Stepping Outside of the Drama

Berne’s (1964) view is that individuals can be helped to recognise their discounts and so identify how scripts prevent new options. For TA practitioners, recognising discounts is therefore empowering. TA reveals the cyclical nature of Drama as an attractive psychological position, and the discounts that sustain it such that ‘authentic’ ways of solving problems may be reclaimed.

Although studies like Carrington et al. (2018) and Wright et al. (2012) demonstrate how change may be enacted once discounts are successfully identified and challenged after some significant event, conditions in Romania are different from those in developed Western countries. Jobs are more precarious and so the opportunities for transformations observed in these studies may also be less common. We might not, therefore, assume that individual change possibilities are universal, or common. And even in these previous studies, high level discounting may be evident, specifically the possibility of political change. We therefore would not be content that spontaneous, ad-hoc and individualised epiphanies are reliable ways of producing system change. Rather, deliberate action may be taken to make managers aware of the discounts required to sustain their identity, and indeed the role of Drama in recreating preferred positions such as Rescuer. TA explains identity work as dramatic because scripts demand a repetition, i.e., a Rescuer will carry on Rescuing until they are prepared to step outside this subject position.

Mellor and Schiff (1975) offer specific advice for getting out of Drama Triangles. First is to help individuals to identify the transactions and behaviours that result from discounting by focusing on external manifestations, as we have done here. Secondly, individuals must be helped to identify the areas, types, and modes of discounting. The CSR Discount Matrix aims to do this. However, Mellor and Schiff (1975) note that the individual then needs to reflect on their investment in discounting, recognising what they don’t see in a situation and so what motivates discounting. This is a task for specific NGO and corporate responsibility workers. Finally, the individual then needs to redirect energy to new behaviour and gain psychological reward for doing so.

For people working in responsible careers, this requires awareness of their own role in the Dramas that lead only to publicity and CSR reporting, and instead of recognising both the damage corporations do to society, and those outside the organisation who are most able to address these problems; a process that is consistent with Driver’s (2006) call for a post-egoic sense of corporate identity that avoids maintaining Drama Triangle positions, or switches, and reflects on the actual, substantive problems in society and the complex role of NGOs and governments in addressing them. This means articulating what is happening in the present, and how problems can be solved by any actor. It may mean rejecting CSR as an approach to solving societal issues altogether.

Conclusion

CSR in Romania is embroiled in relational dynamics that reproduce drama, whilst failing to solve societal problems at the right level. This allows those in responsible careers to repeatedly confirm their own Rescuer position (and that of Victims and Persecutors) without the necessary reflection of other change possibilities. CSR is therefore overly concerned with its own practice, and less so the concerns of citizens, or even beneficiaries. Drama is about CSR workers, not about the transformation of society itself.

Consistent with other psychoanalytically based approaches, TA allows us to recognise processes within CSR that are comforting in terms of their ability to confirm individual scripts, and re-legitimatise corporate capitalism, whilst masking denial of the consequences of corporate actions and individual inactions. Such arrangements maintain the status of the corporation as able to create a better world and ensuring that much of the reality of corporate activity may be discounted. Further, we can use TA to identify the specific discounts that sustain such a discourse. This is important because such knowledge may aid the reflexivity of those involved, inviting them to consider other possibilities.

Romania has specific social, economic and political structures. Yet, the approach to analysing dramas is transferable to other contexts. We have also focused on just one actor—the Rescuer—noting how they construct others. Further research on discounting in CSR might usefully add the perspectives of other stakeholders. And finally, the application of TA to CSR may also be further developed, especially to explore how discounts may be brought into awareness and so addressed.

References

Akpan, W. (2008). Corporate citizenship in the Nigerian petroleum industry: A beneficiary perspective. Development Southern Africa, 25(5), 497–511.

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4), 932–968.

Arnaud, G., & Vidaillet, B. (2018). Clinical and critical: The Lacanian contribution to management and organization studies. Organization, 25(1), 69–97.

Banerjee, S. B. (2008). Corporate social responsibility: The good, the bad and the ugly. Critical Sociology, 34(1), 51–79.

Bennett, R. (1996). Relationship formation and governance in consumer markets: Transactional analysis versus the behaviourist approach. Journal of Marketing Management, 12(5), 416–436.

Berne, E. (1964). Games people play: The psychology of human relationships. London: Penguin.