Abstract

There is a rich tradition of inquiry in consumer research into how collective consumption manifests in various forms and contexts. While this literature has shown how group cohesion prescribes ethical and moral positions, our study explores how ethicality can arise from consumers and their relations in a more emergent fashion. To do so, we present a Levinasian perspective on consumer ethics through a focus on Restaurant Day, a global food carnival that is organized by consumers themselves. Our ethnographic findings highlight a non-individualistic way of approaching ethical subjectivity that translates into acts of catering to the needs of other people and the subversion of extant legislation by foregrounding personal responsibility. These findings show that while consumer gatherings provide participants a license to temporarily subvert existing roles, they also allow the possibility of ethical autonomy when the mundane rules of city life are renegotiated. These sensibilities also create ‘ethical surplus’, which is an affective excess of togetherness. In the Levinasian register, Restaurant Day thus acts as an inarticulable ‘remainder’—a trace of the possibility of being able to live otherwise alongside one another in city contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

If the set-up creates a kind of feeling of trust and people want to be worthy of trust, then Restaurant Day is a thing where a new kind of agency comes into being and shows that it can be created, space can be made, responsibility is assumed, as long as space and freedom are made available (Kirsti).

The opening quote is from one of the spokespeople of Restaurant Day (hereafter RD), a consumer-driven food festival that began in Helsinki, Finland, but has since grown into a global event taking place for one day four times a year.Footnote 1 During the RD events, participating amateur restaurateurs create menus, prepare food, and open one-day pop-up restaurants to serve food in repurposed city spaces. Entire cities become energized as people take to the streets to participate in various ways. The events unfold as grass-roots mobilizations of citizens and manifest in street-level face-to-face interactions that are driven by a shared sense of a carnivalesque mood and collective creativity (Hietanen et al. 2016; Weijo et al. 2018).

What is remarkable about RD is that while it began as a protest against strict restaurant regulations in Finland, it has caused little civil unrest and has even led to various regulative changes in Finnish public policy. Simultaneously, it has grown into an event where anyone can participate on their own terms. These characteristics make RD an interesting context for studying consumer ethics and ethical responsibility that arise emergently in consumer gatherings to then reverberate through broader society. While culturally oriented consumer research has already shed light on how communities of consumption negotiate a sense of moral high ground (e.g., Luedicke et al. 2009; Muñiz and Schau 2005) and how consumers’ behavior changes in concordance with how ethicality is prescribed by community norms (e.g., Kates 2002; Moraes et al. 2012), our focus is more on how ethicality emerges relationally among strangers during ephemeral collective events.

To sensitize our analysis, we read alongside Emmanuel Levinas’s ethical philosophy, where ethics is constituted as personal responsibility towards the Other and enacted in the practices of putting other people’s needs before your own. While Levinasian theorizing has increasingly found its way into business ethics (e.g., Soares 2008; Staricco 2016), his particular ethics has rarely been applied to consumption (Joy et al. 2010). It nevertheless provides ways with which to imagine how immanent ethics can come about as an ethicality of being itself without a fully formed subjectivity ‘in control’ of a person’s ethical dispositions (e.g., Boothroyd 2011; Lechte 2018; Morgan 2011). In this view, experience is not individualized into ‘whole’ and coherent subjects, but rather presents a fractured sense of subjectivity that is in relation to an unknowable otherness which insists on being recognized (Brown 2002; Hand 2009; Roberts 2001) when, for example, sharing a place with strangers.

We interpret social relations in RD as having ethical qualities that emanate from the personal responsibility that people take on for strangers-cum-fellow-participants during RD events. We see glimpses of the way in which marketized social orders become temporarily overturned in how participants selflessly cater to people they are not acquainted with. This sociality goes on to emergently guide their sense of justice in the situational subversion of extant legislation according to what they feel is right and wrong in encounters with other people. These findings reflect a Levinasian conceptualization of ethics and foreground how ethics can emerge from non-calculative personal responsibility rather than enforced rules and regulations (also Rhodes 2012; Rhodes and Westwood 2016; Roberts 2001; Morgan 2011). We argue that this gives some RD participants an affective ‘revelation’ of something outside commonplace social orders and enables them to meet with strangers in ways that extend beyond traditional norm-governed social logics generally ordered by the market-based sensibilities of contemporary society (Herzog 2015).

Our analysis enables us to interpret how the collective RD festivities bring about a particular affective atmosphere of city life, a ‘remainder’ or a ‘trace’ (déchet) of a possibility to live otherwise in ways that might better follow Levinas’s notions of ethical relations. Finally, we discuss the concept of ethical surplus that has been articulated by Arvidsson (2005, 2009, 2011) to consist of the social relations that emerge in collectives of consumption. For Arvidsson, these forms of sociality are what commercial interests attempt to tap into for furthering their business interests. We elaborate on Zwick’s (2013) criticism of Arvidsson’s naturalization of the ethicality of community sociality by questioning the promise of such forms of ethical relations.

To arrive at these findings, we first outline existing understandings of collective forms of consumption and discuss the Levinasian ethics of the Other. We then present the methodological choices guiding our ethnographic fieldwork, and detail our findings that enable us to theorize how grass-roots ethics can emerge from within collective forms of consumption.

Theoretical Background

Collective Forms of Consumption

The study of marketplace cultures associated with various forms of collective consumption has been one of the mainstays of culturally oriented consumer research. This body of work has provided numerous conceptualizations such as brand communities (e.g., McAlexander et al. 2002; Muñiz and O’Guinn 2001), subcultures of consumption (e.g., Kates 2002; Schouten and McAlexander 1995), and brand publics (Arvidsson and Caliandro 2015), that generally vary in terms of the extent of their collective dedication to market symbols, levels of consumer resistance, and the cohesion and the temporality of the collective. Attention has also been paid to highly ephemeral consumer gatherings that have the propensity to suspend conventional social orders in outbursts of carnivalesque sociality, only to then swiftly disperse and reconvene again at a later time (e.g., Bradford and Sherry 2015; Hietanen et al. 2016; Kozinets 2002).

In these ephemeral collectives, sociality tends to momentarily materialize around a temporary subversion of rules, and thus what seems to take place is a renegotiation of social norms in typically carnivalesque settings (Salazar-Sutil 2008), as is the case with events such as ‘Burning Man’ (Kozinets 2002). Such gatherings also manifest in more mundane settings, as the recent study on ‘tailgating’ suggests (Bradford and Sherry 2015), where city space “is temporarily remade into a living place of intimate, playful, humane, personal, and informal modes of organized solidarity” (p. 147) through a “public performance of domesticity” (p. 135). While group cohesion has already been noted to come into being in RD due to a unifying ‘moral outrage’ (Weijo et al. 2018) or a temporarily binding affective ‘mood’ (Hietanen et al. 2016), these tendencies themselves have not been developed theoretically in terms of their ethicality.

The collective negotiation of morals within and between different kinds of communities has also received direct interest (Kates 2002; Luedicke et al. 2009; Moraes et al. 2012). Studies focusing on the moral dimensions of communities have shown how morality can structure social relations (Muñiz and O’Guinn 2001; Weinberger and Wallendorf 2011) and how community members negotiate a sense of moral high ground (Luedicke et al. 2009; Muñiz and Schau 2005). It has also been shown that consumer movements can be mobilized to resist practices that contradict participants’ values related to ethicality and sustainability (Gollnhofer et al. 2019), and that community participants’ behaviors can change to conform to social norms that drive ‘ethical consumption’ (Moraes et al. 2012). Taken in its entirety, the literature generally focuses on moral dispositions that community membership imparts on its participants. What has gathered most interest has thus been inter-group competition and individual status pursuits within collectives, highlighting how social hierarchies can be negotiated and manipulated through consumption acts (Kates 2002; Schau et al. 2009).

It follows that the onto-epistemological tradition of interpretive consumer research has been strongly guided by methodological individualism and the idea of a meaning-making subject of consumption that is largely goal-driven and agentic in a purposeful fashion (Askegaard and Linnet 2011; Thompson et al. 2013). Thus, little interest has been paid to a more general understanding of how ethicality could facilitate collective consumption phenomena as an affective backdrop. Recently, the ‘classical phenomenologist’ position of interpretive consumer research that foregrounds the individual narrative unfolding of meaning in consumer relationships has been challenged by a ‘relational turn’ in consumer research (e.g., Hill et al. 2014). However, conventional approaches of interpretive consumer research can also be reconceptualized from alternative perspectives within the phenomenological tradition itself, and thus we turn to what has been called Emmanuel Levinas’s neo-phenomenology of ethical relations.

Levinas and the Ethics of the Other

Emmanuel Levinas (1906–1995) was a French Jewish philosopher and a former student of the renowned phenomenologist of ‘being’, Martin Heidegger (1889–1976). While he was initially a proponent of Heideggerian phenomenology, his philosophical project turned against Heidegger as a result of his experiences of persecution and imprisonment during the Second World War. Levinas’s ethical philosophy (1979/1961, 1985/1984, 1987/1947, 1988/1947, 1994/1982, 1996a/1962, 1996b/1968, 1996c/1951, 1997/1963, 2007/1987, 2016/1981) constitutes a deeply personal and conceptually sensuous construction of ethical being that is focused on our encounters with the unknown and a reimagining of ethics that is based on an emergent personal responsibility toward the Other. The Levinasian Other, however, is not an identifiable entity or a person, but rather an immanent sense of the world where an abstract ‘otherness’ always conditions our fleeting experience of being (also Hand 2009; Lechte 2018). Thus, Levinas engages with the unknown in a manner that reaches beyond what the mind’s eye can see—the ethical imperative of facing an indeterminate and overwhelming ‘infinity’.

The Other, Inescapable Guilt and the Possibility of an Ethical Revelation

Ethics, for Levinas, is constituted by the act(s) of putting the needs of the Other(s) before your own and leaving your self-centered existence to do so without the pretense of reciprocity (also Aasland 2009; Morgan 2011; Rhodes and Westwood 2016; Soares 2008). His ethical phenomenology follows a poststructural lineage due to the excessive and nontotalizable nature of the relation that one has with the Other, and equally due to the idea of subjectivity that is constantly overwhelmed by this unknowability of otherness (Brown 2002; Herzog 2015).

For Levinas, the Other is what interrupts one’s being-in-the-world. The recognition of the Other denotes an overwhelming presence that a subject cannot fully internalize nor comprehend (also Morgan 2011; Soares 2008). When coming into contact with the Other, ‘she’ imposes a need on the subject and demands space to cohabit the world. This recognition of the unknowable Other and its strenuous plea of cohabitation is the source of Levinasian ethical agency (Morgan 2011) as it makes the subject personally responsible for the Other (also Soares 2008). Simultaneously, encounters with the Other open up avenues to potential selves and alternative modes of being, as the subject opens up to the infinite possibilities of being defined by others. Importantly, however, opening oneself to the other is an act of

Vulnerability, exposure to outrage, to wounding, passivity more passive than all patience, passivity of the accusative form, trauma of accusation suffered by a hostage to the point of persecution, implicating the identity of the hostage who substitutes himself for the others: all this is the self, a defecting or defeat of the ego’s identity (Levinas 2016, p. 15).

Encountering the Other is thus not to be confused with an ecstatic liberation, but rather an emotionally violent interruption of a more egotistic being, since in the moment of awaking to the presence of otherness the subject is forced to open up itself for the Other and to feel and take part in the Other’s wounds and pain.

For Levinas, what thus needs to take place in order to found an ethical sensibility in being is an ethical ‘revelation’ that anticipates the Other. This marks an affective discovery or a realization of ‘shame’ in front of suffering in the world (Morgan 2011), guilt for being there and for having survived all possible injustices of society, and for having the Other as a universal oppressed look at you and demand recognition. For Levinas, any ethicality needs this revelation so as to be able to open up and suffer ‘for’ the Other. The ethical revelation takes place when one can no longer ignore the injustice that one sees, and thus one’s desire impels one to act in new ways. The bracketed world of the subject now opens up to the infinite alterity of the Other and is overwhelmed by its depths.

What pushes us to the sensation of revelation is desire as the affective flow of living itself (Boothroyd 2011; Lechte 2018; Yar 2001). Desire here is a primordial unconscious force that has nothing to do with a conscious subject which emerges only far ‘later’ in experience that rationalizes the “creative pulsion” (Levinas 1979, p. 128). Thus, desire is not based on conscious ‘intentionality’ or a need to be fulfilled (also Lechte 2018), but is rather a ‘condition’ which is deepened by every relation it brings about. Thus, for Levinas, the ethical impetus is a desiring thrust, not an act of (an already rationalized and totalized) conscious mind. It also denotes the willingness to leave one’s own solitude and show ‘hospitality’ towards the Other in a way that is not seeking self-interested reciprocation (Lechte 2018; Rhodes and Westwood 2016).

There is thus an inherent tension in Levinasian theorizing that is ‘carried’ by a subjectivity that is constantly in the making. It is not the fully conscious ‘I’ of modernity’s contractual individualism, but rather something that hangs in the tension of desperately reaching for an identity while being simultaneously faced with the overwhelming ‘revelation’ of its finitude in the face of an all-encompassing otherness: the sublime of infinity (Lash 1996). Thus, ethics becomes the ‘first philosophy’, as to be ‘human’ already assumes an ethical disposition towards the world, towards the “unknown, and unknowable, which is the infinite and timeless otherness of the Other” (Bevan and Corvellec 2007, p. 208).

Orders of Relation, Intersubjectivity, and Justice

To understand how his eponymous ethic comes into being, Levinas outlines a number of key concepts that include the there is, the I, the face of the Other, the third, and justice. Existence—the there is—always constitutes an active and anonymous presence, which is to say that the backdrop for existing is an unspecific but always actively present sense of being. Against this anonymous and impersonal background, the I, is a rupture—the emergence of a subject that is put into contact with its own existence. Here, when the subject convinces itself of being “fully at home in the world” (Morgan 2011, p. 38), it grasps the world as an internalized totality that is systematic, categorized, and an organized whole. For Levinas, this is a totalizing place where a solitary individual desperately seeks to rationalize itself and consumes the world by and for itself (also Rhodes 2012; Yar 2001). In this modality of being, social relations constitute trade that is driven by enlightened self-interest (Roberts 2001), and ethics are constituted by the rules that regulate this pursuit. For Levinas, however, this mode of existing consists of a contemporary way of life that is as unethical as it is an illusion (also Rhodes and Westwood 2016). The coherent self that abides by structures and rules fails to give grounds to ethics because it makes the person only legally responsible in the face of norms, and thus eludes a deeper ethical revelation of personal responsibility to the Other (Herzog 2015; Muhr 2008; Roberts 2001).

A ‘concrete’ manifestation of the abstract notion of the Other is the face. For Levinas, the face is not a corporeal entity or countenance, but rather the epiphany of the Other that one encounters which constantly overflows “the plastic image it leaves me” (Levinas 1979, p. 51). The face

escapes representation; it is the very collapse of phenomenality. Not because it is too brutal to appear, but because in a sense too weak, non-phenomenon because less than a phenomenon. The disclosing of a face is nudity, non-form, abandon of self, aging, dying, more naked than nudity. It is poverty, skin with wrinkles, which are a trace of itself (Levinas 2016, p. 88).

The face is thus simultaneously both naked and destitute, something that could be totalized for reasons of personal gain, but in its vulnerability it marks an excess that cannot readily be made into a fully distinct and totalizable idea. For Levinas, this makes the ethical relationship to the face to be neither that of a master nor a servant, but of equality in mutually actualizing indeterminability. The responsibility that one has for the Other is acted out in face-to-face encounters with the Other, which makes ethics an event: a becoming, rather than a matter of a structure (also Morgan 2011).

In addition to the Other, there are always ‘other others’, which Levinas calls the third, that is all the others for whom we are also responsible, “the proximity of a human plurality” (Levinas 1987, p. 106) that the infinity of the Other necessarily implies. The idea of the third brings ethics into a broader social context than that of the one-to-one relationship with the Other. Encountering the Other thus always involves a presence of the third, as it implicitly reminds us of the other others for whom we have an ethical responsibility (Aasland 2009; Boothroyd 2011; Muhr 2008).

Stemming from the subject’s relationship to all otherness, it is forced into dividing its attention between its own needs and the infinite neediness of all others. How a subject relates to the needs of all others and attends to them constitutes justice for Levinas (also Aasland 2009; Muhr 2008), and it manifests as an interminable tension between infinite responsibility and its limits (Rhodes and Westwood 2016; Staricco 2016). In doing so, justice is grounded in ethical responsibility towards all others and therefore it emerges from a personal responsibility rather than rules or established societal norms. However, one is simultaneously forced to judge to whom this responsibility is extended, since one is incapable of attending to the needs of all others. Thus, a subject’s conception of justice calls on it to establish paradoxical limits to its responsibility (Introna 2009), but also questions them in the face of others and their needs (Muhr 2008). To do justice is thus not a ‘skill’ with an outcome, but a perpetual practice of anxiety and contradiction (Rhodes 2012). In contrast, justice without personal responsibility generates moral distance and enables people to be ethically indifferent towards each other by simply following rules and norms that allow an escape to structures that subvert one’s personal involvement. Especially in the context of city life, this makes us all unintentionally guilty of irreconcilable negligence, as the “rights and protection enjoyed in a liberal society are both the result and the essence of our half-guilt” (Herzog 2015, p. 35).

To sum up, while the notion of the subject as an agentic (and cognitively intentional) conductor of phenomenological reasoning largely continues to take precedence in the conventional Husserlian tradition (Bergo 2011) as well as in the individualistic tradition of consumer research, Levinas’s neo-phenomenology finds recourse in a more abstract form of theorizing where the ‘solidity’ of the subject is thoroughly fragmented. For him, a subjectivity undergoing an ethical revelation comes to share a deep intersubjective burden that is always implicitly there as an otherness we cannot quite grasp or articulate: a perpetual sense of guilt that we could have done more for the others. It is not a stable subject that is found in intersubjectivity by Levinas, but precisely the breakdown of its very possibility in the face of the infinity of the Other.

Thus, the Levinasian perspective casts doubt on rule-based ethics that easily turn into the management of appearances where people are only concerned with being seen as ethical (Herzog 2015; Muhr 2008). Instead, it foregrounds a never-ending and indefinite personal responsibility that should manifest in uncalculated acts of goodness. To analyze how this kind of ethicality manifests in RD, we mobilize key Levinasian concepts to guide our empirical inquiry. We focus on elaborating on participants’ understandings of their own subjectivity during RD events (the I), how they relate to others in the emergently unfolding events (the Other), and how they are disposed to encounter strangers during them (the face). Beyond these immediate one-to-one relations, we analyze ethicality in the broader social context of RD to understand participants’ relations to each other (the third) and how this relationality leads to an emergent sense of justice that manifests in RD. Finally, while it has been suggested that Levinasian thought should not be ‘used’ in any empirical fashion (Fred Alford 2014), we subscribe to an ‘empirical’ reading of Levinas (Morgan 2011). We therefore attempt to work alongside his thought in a way that is inspired by how he confronts his ideas with particular cases in the Talmudic Readings, and how he suggests that general ideas need to be confronted with particular situations in order to avoid turning them into totalizing ideologies (also Herzog 2015).

Restaurant Day Background

Restaurant Day is the world’s largest pop-up food carnival and takes place four times a year (https://www.restaurantday.org). During RD events, anyone is welcome to open up a restaurant or a café for a day. To do so, people repurpose their homes and workplaces or public spaces (such as parks and street corners) for their restaurants, temporarily reappropriating both public and privately owned city spaces in ways that redefine them as open and publicly ‘alive’ and inviting for the day.

Initially RD was spurred by the disenchantment that a group of Helsinki residents felt towards what they saw as Finland’s restrictive restaurant regulations. An oft-cited kindle for the initial event was founding member Antti Tuomola’s attempts to open up a restaurant which were thwarted at every turn by the wheels of bureaucratic regulation. The first RD events were branded as civil disobedience since people were opening pop-up restaurants and bars illicitly en masse in disregard of the legislative hoops. However, due to significant media coverage and changes in Finnish food consumption habits that RD satiates, it rapidly gained popularity, first in Finland and then abroad (also Weijo et al. 2018). Simultaneously, the overtones of protest were superseded by a carnivalesque mood of self-expression that turned common retailing practices towards the creation of urban sociality (Hietanen et al. 2016).

Since its inception in 2011, the growing success of RD has also had an impact on how the events are emergently organized. While in the first events the names and locations of restaurants were gathered via e-mail and circulated freely in the Internet, currently this happens through an RD Facebook page and a dedicated app through which people can register their own restaurants and search for others. While the inaugural event involved around 40 restaurants in 13 different cities in Finland, the biggest RD event to date (in May 2014) saw the participation of over 2700 restaurants in 35 countries. In total, approximately 24,800 one day restaurants have taken part in RD events and served food to an estimated 2.8 million people in 74 countries (RD Facebook page, September 2018). Despite the size and scope of RD, it does not have a large central organizing body, but rather a number of volunteers who act as moderators and public spokespeople for each event. Similarly, the central contact points of RD, such as the Facebook page and the app, have all come into being solely through volunteer work. Thus, it is important to note that RD does not present us with something that can be delimited as a distinct consumer ‘community’ or ‘subculture’. It is rather a temporary unfolding of mutual excitations of virtual strangers whose commonality is little more than shared affectivity and embodied presence in a cityscape (also Salazar-Sutil 2008).

From its foundational Finnish perspective and as a consequence of its ascendant popularity, RD has also had a striking impact on restaurant legislation and public policy. As Hietanen et al. (2016) have already noted, RD has led to changes in Finnish food regulations with the result that pop-ups no longer have to report their activities to food safety authorities. Some of the founding members of RD have also assumed positions in public authorities that promote food culture in Helsinki.

Methodology

Our ethnographic fieldwork during RD events followed the hermeneutic tradition of consumer research (e.g., Arnold and Fischer 1994; Thompson 1997), which is involved in producing rich and diverse interpretations of how meaning is produced and negotiated in cultural contexts. While ethnographic approaches have tended to focus on observable social behaviors in a more descriptive fashion (e.g., Jarzabkowski et al. 2014; Linstead 1993), our approach follows Arnould and Wallendorf’s (1994) ‘market-oriented ethnography’ that was, from its outset, more inclined towards immersion (rather than distant observation) that could bring about “revelatory incidents” (p. 485) and thus allow for stronger subjective interpretations that go beyond simply cataloguing activities or taking the narratives of participants as accurate descriptions of behavior and experience. As an open-ended contextual approach, ethnographic interpretation will always remain incomplete and thus rather seeks to account for diversity of meanings. Through a systematic engagement with data, there is nevertheless a focus on the participatory ‘creation’ of convincing experiential academic texts (Arnould and Wallendorf 1994; Denzin 2001; Jarzabkowski et al. 2014). Thus, we were interested in ethnographic participation that was open to immersion and affective experience (Linstead 1993; Sherry and Schouten 2002).

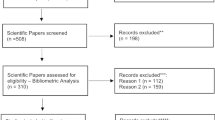

In a practical sense, this study of RD was part of a multi-year ethnographic project that involved a large group of scholars including professors, post-doctoral researchers, doctoral students, and students working on their Master’s theses. We participated in 7 RD events and our fieldwork involved navigating the city streets, active participation in various pop-up restaurants, and spontaneous conversations in situ with various participants. We also recorded hours of video footage and took numerous photographs in order to lose less of the immanent effervescence of being present and actively partaking in the production and the excitement of the events (Hietanen et al. 2014). The video material, shot by various members of the broader research effort, comprised hours of interviews and also diverse situational footage highlighting the researchers’ journeys from location to location in various seasonal settings, whether in piling snow or under the summer blaze.

In addition to taking part in RD events, we conducted 28 ethnographic interviews (Arnould and Wallendorf 1994) with participant customers and restaurateurs, founding members of RD, and public actors such as journalists and local authorities. These interviews were guided by the long interview approach (McCracken 1988) and gauged different dimensions of the event including participants’ practices, motivations, and plans, but also their hopes and feelings. The diversity of perspectives was further enriched by the fact that many of the interviewees had participated in multiple roles.

To further sensitize our data set and reduce the risk of “blitzkrieg ethnography” (Sherry 1987, p. 371), we also conducted netnography (e.g., Kozinets 2002; Weijo et al. 2014) of various blogs and social media sites that were closely linked to RD phenomena, which amounted to an analysis of hundreds of online entries. In addition, we actively followed media coverage of the events in the popular press. The diverse data produced by the research team were pooled together,Footnote 2 which allowed for an ongoing comparing and contrasting of views among the research team members.

As our theoretical interest focused on how ethical relations manifest socially in a carnivalesque setting, the verbal accounts of the ethnographic interviews and netnographic discussions were first coded based on interpretations of relational meanings. This guided us to code the data iteratively by focusing first on the singular notions of how participants negotiated their subjectivity in the events (corresponding to the Levinasian notion of ‘the I’), and then to gradually expand the analytical framework to more abstract relations (‘the Other’, ‘the face’) and sociality in a broader sense (‘the third’ and ‘justice’). Thereafter, our analysis cycled between the different perspectives that the coded data provided, reflecting on them and comparing them to our own experiences and the visual data, while comparing and contrasting them to theory in order to arrive at our findings and to develop the consequent theorization. This generally followed an abductive logic (Kennedy and Thornberg 2018) and enabled us to bridge our interpretive work with theorizing how the atmosphere of the city space changes during the events to bring about the possibility of alternative ethical relationalities.

It must be noted, however, that following Levinas’s theorizing we are challenged with going beyond individual meanings and thus need to interpret contexts that exceed the represented (also Askegaard and Linnet 2011). Applying Levinas’s notions requires us to resist following representational logics alone, and thus we have placed a great interest on interpreting the fragmented nature of subjectivity and how the ‘I’ of the individual is constantly ‘overwhelmed’ (Brown 2002; Knudsen and Stage 2015), always at best desperately grasping the excesses the world is constantly throwing our way during the events. Our interpretations based on the coded data follow similar logics, where we do not so much attempt to interpret singular meaning from interview moments, but rather more abstract revelations (also Thompson et al. 1998) of ethicality in the RD events that may be grounded in their collective and carnivalesque nature. Thus, what we are attempting to assess are some potential manifestations of Levinas’s ethics in collective practice, however elusive and ephemeral they may be.

Findings

A driving force for participating in RD is a desire to creatively engage in new social situations and events, but there is also a marked awakening of the need to take personal responsibility for one’s actions. This is not necessarily in the face of ‘persons’, but rather the event itself as it comes into being in a spontaneous fashion. It is about stepping outside of the anonymous indifference of urban life in order to promote humane face-to-face interaction (also Herzog 2015). While the outburst of desire to engage in collective action can be seen to intertwine with the carnivalesque nature of the event (see Hietanen et al. 2016), this theorizing fails to acknowledge that even in events where common rules and habits of social behavior are inverted, this can only come into being and ‘hang together’ if there are certain ethical inclinations that come together in acts of participation. To understand how this ethicality comes into being, we present three Levinasian themes that arose from participating in multiple events over the course of a number of years. We interpret an emergent consumer ethics during RD that can be characterized by relations involving: (1) I, the participant, (2) the Other and the face, and (3) the third and justice.

I, the Participant

People participate in RD in various ways. They temporarily assume different roles for the duration of an event, be it restaurateur or customer, and the enactment of these roles brings about new social relations that make the events come alive. To do so, participants negotiate temporary subjectivities in accordance with the momentary difference the event makes in understandings of sociality and the use of city space. This also affects how they experience and approach their ethical sensibilities, since ethicality can revolve around straightforward rule-following or a deeper sense of personal responsibility (Loacker and Muhr 2009).

With the growing success of RD, commercial interests have also seeped into the events in increasing fashion. As already noted by Hietanen et al. (2016), it seems clear that some participants follow conventional commercial logics of personal monetary gain to define their way of participating in RD. Thus, unsurprisingly, we also encountered restaurateurs who partook in RD events to make money, such as a pair of friends running a curbside hotdog stand who openly told us that they were there selling their goods to make some extra cash. Yet, commercial practices also assume more subtle forms. In this light, consider what one restaurateur opined to us:

Well we wanted to pretend that we could be chefs someday, I don’t think we will but, I mean, it’s fun and at least previously we made a nice little profit out of it. I mean not millions but we’re saving up our profits now for a trip to, I think it is going to be parachuting in Lisbon. The three of us can go there with the money we’re making here and like eat well, have a good time for a weekend or so. So, it’s a little bit our goal, keeps the guys interested too (restaurateurs of an Asian fusion restaurant).

While the group of friends saw RD as an opportunity to experiment with the role of chefs, they simultaneously adopted the broader market logic to define RD, wherein the chef holds a specific position in relation to what now becomes constructed as ‘customers’. In doing so, they extended the commercial logic they see and embody in their ordinary life to the context of RD. This could be seen to largely preclude the participants from finding alternative ways of participating in the event and allows participants to readily follow market-based social rules internalized subjectively. This is not surprising as RD is hardly revolutionary, yet it seems hard to imagine RD as business-as-usual either. We felt that new forms of approaching others in common solidarity remain a desiring impetus for the event.

While commercial logics have been adopted in RD to a visible extent, many participants still attend RD to try out new ways of being with others. This takes the forms of being a restaurateur for a day or a customer seeking once-in-a-lifetime culinary experiences as part of the RD crowd. In doing so, participants ‘open’ their personal selves to the possibilities of being influenced by other people that are unfamiliar to them, albeit likely to share a similar affective thrust. This forces the participants into novel relations with those whom they have never met before, thus exposing them to the ills and rewards of being defined by the Other. One RD restaurateur told us the following regarding what sparked their interest in participating, and what setting up their restaurant was like at different events:

I think it’s because you can toy with the idea of having a restaurant [before and during the events] and at least I want my own restaurant, have always wanted. It just sounds good. And the fact that you have your friends around who think in the same way [is great] and [it’s] a good hobby. And the fact that you rarely get feedback so fast and that the feedback is positive is quite amazing. You cook some food, somebody tastes it and says it is good. That can potentially happen at home but the fact that a stranger comes and tells your food is good is pretty great.[…] But it’s always stressing, does the meat cook fast enough and things like that, and of course if it is going to be any good is the thing that you are stressing about. And of course, will anybody show up. That’s always been a riddle. And what the weather is like when we have been outside [setting up and serving food] has been kind of a risk. Especially when we were there in February when it was -20 [Celsius], we were thinking whether anybody would really show up. I mean anybody (restaurateur of an American BBQ restaurant).

Despite the anxiety concerning whether the food would be good and whether people would find the restaurant, encounters with other participants seem to have had a profound impact on this restaurateur since he later opened a professional restaurant with the same friends with whom he had run his RD restaurant. In a similar manner, many restaurateurs told to us that they wanted to partake in RD in order to try something different and to be a part of an energetic feeling resonating in the city. It facilitated a way of getting together with other people and offering them new experiences of social caring and togetherness. Simultaneously, it gave the restaurateurs the opportunity to envision new ways of being, such as opening one’s home to strangers or trying out what it is like to be a restaurateur, even if only for a single day. However, for many, participation as a restaurateur was not a premeditated endeavor but rather a “whim” and a “spontaneous thing” as one group of participants running a restaurant that sold French soups told us.

This openness to encountering the unexpected was also shared by participating customers. Many of them seemed to have a loose plan to visit certain restaurants, but simultaneously they commonly shared an inclination to either wander around or visit popular restaurant clusters in order to see what was happening. One customer-cum-food-scene-activist encapsulated this idea by saying that while he does do some planning, the fun part of RD is the “element of surprise” and that you can “walk across a street corner to find something that looks like a bazaar”. Likewise, our own field visits included pre-planned restaurant visits, but they were also punctuated by the epiphany of finding something unexpected such as a dance studio serving cake. This abundance of possibilities was also highlighted by one of the RD spokespersons:

For example, we have had a Somalian family that has invited people to their home to eat their traditional foods. Islandic restaurants have been involved, fried grasshoppers, frog legs […] basically everything that you can’t normally get from anywhere.

These possibilities were strongly contrasted to the impersonal landscape of chain restaurants in the context of mundane city life. For instance, one participant noted the following concerning what RD stands for her:

In my mind, it’s civil activity that tries to increase communality. We have a large population of people living in the cities who know nothing of their neighbors, they don’t know who lives along the same staircase. So yes, if someone sets up a Restaurant Day restaurant in the courtyard of such a housing complex, then gosh, that at least teaches people to know each other. That’s quite something.

We also experienced similar epiphanies ourselves, seeing our own hometown and neighborhood momentarily in a strikingly different light. This contrast became all the more pronounced after the events when streets and parks emptied and returned to their everyday normalcy, and those serving us food returned to being anonymous passers-by on the streets of Helsinki.

Expecting the unexpected was an ethos seemingly shared by many participants, whether their momentary role was as a restaurateur or a customer. On a broader scale, this willingness to look beyond established practices and expectations could be seen as one reason for the success of RD (see Hietanen et al. 2016). However, this leap requires that the participants relinquish a self-centered mode of a ‘customer proper’ or service recipient in order to recognize other people and interact with them with mutual curiosity.

The Other and the Face

As much as RD is about experiencing culinary delights, it is also about meeting other people and negotiating new ways of sharing city space. While some of these opportunities are appropriated by those seeking to benefit from the events or just enjoy the gastronomic experiences, our fieldwork suggests that many participants make significant efforts to put the needs of the Other before their own when participating in RD, and that they are strongly affected by the personal responsibility that arises from face-to-face interactions. This shows how RD participants engage with otherness in order to imbue social practice with ethicality.

The freedom to participate on one’s own terms energizes RD as a city-wide phenomenon, as it is not bound to closed communities or readily definable groups of people with predictably similar tastes or backgrounds. It enables previously unfamiliar people to gather together en masse, which foregrounds the abstract Other that participants need to recognize and relate to. Many participants embrace the freedom of this temporary inversion of social space and respond accordingly to the ‘unknown’ with curiosity, thus giving restaurateurs the opportunity to showcase the products of their imagination. As one participant noted:

Like last time last Autumn I was on my way here to Kallio on my bike and suddenly the front of Kiasma [Museum of Modern Art] was all lit up by candles. I was like what’s going on here, well what they had was a pop-up tea joint, and of course we needed to stop to have some. It is all so sudden and surprising, that people are willing to surprise you in such ways. It’s quite wonderful really! (Young woman at a tobacconist turned into a cafe).

This epiphany of finding the unexpected and stopping to appreciate it is exhilarating for many participants. It becomes part of the thrill of being there in the moment, and temporarily dissolves taken-for-granted social boundaries, as one is never sure what lies around the next street corner. However, these discoveries are hardly utility-driven since participants are knowledgeable that restaurants are not typically professionally managed and tend to run out of stock during the events. Thus, participating customers appeared open-minded, forgiving, and willing to make an effort when searching for and visiting RD restaurants—in effect coming into contact with the Other and giving it space for expression.

This sense of otherness also extends to the restaurateurs who make the epiphanies of other participants possible. In preparing for the events, many restaurateurs cook a sizeable number of portions, and some of them are capable of serving several hundred meals in a single day. Some restaurateurs spend several days or even weeks preparing the meals and spend hundreds of Euros in order to open up their restaurant for a single day. Despite the amount of effort, restaurateurs can only have a vague idea of who their customers might be. While many pointed out that their friends were coming over to support their makeshift pop-up restaurant, this would have hardly enabled them to sell all their meals (or break even). Rather, they relied on the RD Facebook page and mobile app to draw in interested people whom they have never met before. In return, the restaurateurs derived joy from seeing strangers’ queue up to taste their food. As one restaurateur said to us during a discussion at their restaurant:

Well, it’s nice to see the people queuing here in front of my apartment last time. So […] And we love Japanese food and we want share it with the people. So that’s it (restaurateurs of a Japanese restaurant).

Especially for those who were running pop-up restaurants without an explicit profit motive, there seemed to be a willingness to show hospitality and cater to the unknown crowds that might or might not find their restaurant, essentially showing how they were putting the needs of the Other before their own self-interest. Thus, both restaurateurs and participating customers seem to embrace otherness in their own way. For customers, it translates into the effort they exert finding new and interesting pop-up locations and their purveyors, while simultaneously recognizing that many of the restaurateurs are amateurs who are not used to catering to the masses. The restaurateurs, in turn, embrace otherness, hoping that their skills, creativity, and whatever means of food preparation they have at their disposal will allow them to serve as many customers as possible without delimiting who can attend.

While the preceding interpretations connect to the abstract notion of the Other in different forms, street-level, face-to-face encounters momentarily concretize this otherness. At different RD locations, people generally seemed to be considerate of each other and even long queues were filled with friendly chatter. In contrast to normal city life, many participants seemed to appreciate the opportunity that “people can gather together and you can talk to complete strangers” (young participant at a Lapland inspired restaurant). While people would generally be apprehensive of strangers approaching them in mundane city life, the atmosphere of RD seemed to invert inhibitions, and thus even typically inconvenient situations such as queuing became full of welcoming encounters.

Many people also told us that food safety was not really a concern for them since they were less afraid to eat at someone’s home than at a restaurant. This friendly atmosphere has also affected public opinion because while RD was initially portrayed as civil disobedience and concerns were raised regarding food safety, many public authorities, such as the City of Helsinki, have come to endorse RD. Kirsti, one of the founding members explained to us why she thinks the events unfold in such an orderly manner:

This is a way of us showing that if you give people the sense of freedom, many may think that anarchy immediately ensues, but it rather seems that people are really willing to be responsible about it. If you’re a restaurateur in RD, it’s unlikely you’d come there to cause harm to others. Of course, a part of this is openness and transparency, and the participants who have registered their interest online do also leave their contact details. It’s about meeting people face-to-face.

With the absence of a street-level organizing body, it appears that a mutual appreciation for other people in face-to-face interactions results in RD unfolding with little civil unrest, despite thousands of participants being drawn to each event. A local police officer also attested to this, saying that “it [RD] hasn’t really caused us any excess work”. Overall, the participants seemed highly aware of their personal responsibility towards other people and the notion of the event itself.

The Third and Justice

Beyond the immediate other person that one encounters during RD events, there is the broader community of people who participate. They can be understood as the ‘other others’ or the Levinasinan concept of ‘the third’. This takes the personal responsibility towards the Other to a broader social level (Aasland 2009) and also leads to the emergence of a sense of ‘justice’ that forces participants to divide their resources and attention between their own needs and wants and those of all others (also Rhodes 2012; Staricco 2016). We interpret various dimensions of this emergent sense of justice in RD and how it is used to subvert extant legislation during the events.

While commercial interests such as spin-off pop-ups from professional restaurants have manifestly reappropriated RD in the wake of its increasing popularity, the overall spirit of the event still seems to continue robustly promoting inclusion and non-competition. Restaurateurs generally did not see others as competitors and some noted that they would like to visit other restaurants if they had the time to do so. While the logic of exchange is present in the idea of offering culinary treats for purchase, a competitive spirit of contemporary commodity capitalism was nevertheless suspended to foreground togetherness, a sort of possibility of finding ephemeral unity among strangers. One restaurateur told us the following while serving us pumpkin soup from his stall:

There is no competition, I think it’s the more the merrier and makes for a sort of farmer’s market feeling. Such a marketplace and this kind of making thing happen together and a bit of a friendly competitive spirit and banter is good though (restaurateur of a vegan soup restaurant).

Neither did participating customers see restaurants as competing with each other commercially, as the collective responsibility for the entire social event seemed to claim precedence. This ethos was facilitated by non-calculative practices, as many restaurants ran out of stock during the events and the increasing number of pop-up restaurants eased congestion and queues. We also experienced this ourselves as some of the locations we intended to visit had sold out before we arrived and others had long queues.

While the participating restaurants were not really seen as competing with each other, people seemed to draw a demarcation line with regard to what kind of restaurants should be supported. To push back against commercial reappropriation, many participants clearly expressed their disinclination to visit restaurants that extended their commercial business to RD. However, they were still lenient towards the participation of professional restaurants if they used a concept different from their commercial activities and abided by the spirit of the event. For instance, the chefs of Chez Dominique (a two Michelin star restaurant in Helsinki) participated in RD with their own pop-up restaurant, but their endeavor drew no explicit connection with the professional restaurant they ran as a day job and that was generally deemed to be acceptable. This reluctance to support commercial activities seemed to be a safeguard that many participants upheld in order to protect the original idea of RD; one participant concisely expressed this sentiment as “ordinary people catering for ordinary people”.

Participants also appeared to draw a similar line of demarcation in regard to pricing, as explicit profit-making was openly condemned. Many restaurants priced their food to cover costs incurred from making the food and buying equipment for the event, or in some cases to make a small profit. Some restaurants embraced more altruistic exchange practices by donating their proceeds to charity, and some had done away with the conventional notion of ‘payment’ altogether by accepting used toys or a public poetry recitation for a serving. One restaurateur concretized this idea in the following way during one of the RD events:

We had a pretty good mission that we sort of wrote. Good feeling to ourselves and the customers, and then somehow quality ingredients, and lastly kind of came the idea that we could break even (restaurateurs of a French soup restaurant).

We generally came to feel that various playful pricing practices (as noted above) and a sense of fairness among participants were forms of inclusion in RD. The RD Facebook page was also used for this negotiation since pricing was continuously discussed and high-priced and obviously profit-seeking restaurants were openly condemned. Those deemed to be altruistic restaurateurs were vocally lauded, such as one group who had distributed free food vouchers and bus tickets to homeless people so that they could come and eat for free.

With the suspension of many typical roles and rules that structure city life, RD constitutes a distinct sphere of activity where existing legislation is temporarily subverted for what the participants perceive to be just going about ‘living’ in Helsinki City spaces. This emergent justice grows from within the participating mass of people and also spills over beyond RD events. In a pragmatic sense, the most prominent example of this is the impact that RD has had on Finnish restaurant legislation by mobilizing a movement that has led to lasting regulative changes. However, this is not the only instance where RD participants disregard legislation in favor of their own rules. For instance, during one of our field visits we encountered a restaurant selling tacos made with insects where the restaurateurs simultaneously educated customers on EU legislation that banned selling such food in restaurants. The long line outside the taco stand revealed that regular citizens did not really see this as a threat to their safety and rather welcomed it as an opportunity to explore something new; EU laws have in fact since changed to allow the selling of insect-based foods.Footnote 3

While the aforementioned instances depict how RD has either led to or anticipated broader regulative changes, some practices still remain illegal. One such practice is the serving of alcohol during RD events as Finnish alcohol legislation prohibits alcohol sales without thorough training and licensing. Despite being an illicit practice, alcoholic beverages were nevertheless openly served by a number of pop-ups during the first RD event and unlicensed alcohol continued to be offered during latter events with varying degrees of discreetness. Participants generally welcomed this as another practice of inverting the rules and saw it as a way to promote the more moderate alcohol culture typically associated with Southern Europe, in which intoxication is not the explicit focus. One customer told to us the following when we conversed on the topic during one event:

I think it should be offered freely, one should not stare the letter of the law so precisely. This kind of social selling of alcohol is exactly what can help to create a more moderate culture of consumption. Like if you have a wine or a beer with food, you shouldn’t necessarily think of it as boozing (young participant at a Lapland inspired restaurant).

While serving alcohol is indeed an illegal activity during RD, the participants seem to uphold a different register of justice that permits the consumption of alcohol in combination with food, but shuns drinking with the purpose of becoming intoxicated. What these practices highlight is that RD constitutes a distinct sphere of ethical activity, where participants apply their own rules to define collectively what is acceptable and what is not. In RD, participants thus seemed to generally lean towards their own understanding of justice as a basis for an ethical sensibility rather than the exact letter of the law. Thus, what we see in these instances is how RD participants extend their generosity to other participants, how the limits of this generosity are negotiated, and how participants question existing rules and regulations when facing others.

Discussion

Personal Responsibility in Restaurant Day

We suggest that what our interpretations of RD show are glimpses, if only fleeting and ephemeral, of Levinasian ethics of the Other. RD is a rupture within social relations that are typically guided by more reciprocal calculations and market-based relations that circumscribe novel social possibilities by foregrounding exchange and rule-following (see Aasland 2009; Herzog 2015). This emergent ethicality manifests in the way many RD participants open themselves up to otherness during the events (connecting with the Levinasian notion of ‘the I’), how they make an effort to meet new people and experience something novel (‘the Other’, ‘the face’), and how this leads to a sense of what is right and wrong towards others (‘the third’ and ‘justice’). Thus, what we find is a momentary ethic without the illusion of universality that is grounded on the personal responsibility towards the Other that many participants seem to seize and act upon. These emergent qualities of ethicality in RD also set our findings apart from existing studies that have largely focused on morals that community membership impart on its participants (e.g., Luedicke et al. 2009; Muñiz and O’Guinn 2001; Weinberger and Wallendorf 2011).

Due to the ephemeral nature of RD events, participants follow different logics in negotiating their temporary subjectivities and their social relations. Some appropriate commercial logics and see RD as just another commercial marketplace where goods and services are traded. In this mode, the subject rationalizes the event and one’s role in it, thus trading ethical sensibilities for calculated utility. However, many participants attend in a more spontaneous fashion and find ways to open up to the wonders of otherness—a ‘revelation’ of the Other that they desire to engage with (Boothroyd 2011; Lechte 2018; Yar 2001). While this opens up opportunities for the participants to encounter new people and find new subjectivities (also Loacker and Muhr 2009), it simultaneously introduces a burden of responsibility felt towards the Other (also Aasland 2009; Boothroyd 2011).

While those following commercial logics seal themselves off from otherness in the Levinasian sense, many participants come into contact with the Other in different ways. This translates into the work they put into finding, participating in, and appreciating the offerings of the one-day restaurateurs. In turn, many participant-restaurateurs make substantial investments in their restaurants in order to participate in the RD events and selflessly cater for people whom they can only hope might show up. These investments show how RD participants frequently put hospitality and welcoming the mutual participation of the Other before their own needs, which can be interpreted as momentarily instantiating the Levinasian ethical act. From this perspective, a significant part of RD is constituted of individual acts of ‘goodness’ that together transform it into an event grounded in ethical sociality. This ethicality becomes concretized in face-to-face interactions between people that manifest as encounters with the Other rather than following structures (also Morgan 2011). It is facilitated by the events as spontaneous gatherings of people where the willingness to embrace the closeness of strangers takes precedence over conventional norms and rules. In so doing, participants become highly aware of their personal responsibility because they cannot hide behind external rules or codes (see Muhr 2008; Roberts 2001) when interacting with others.

Our findings further highlight how RD participants were inclined to apply their own sense of justice to negotiate and define what is acceptable and what is not. Many participants thus seemed to lean towards their own understanding of what is just towards others rather than the law as a basis for an ethical sensibility. While ordinary city life facilitates anonymity and ethical indifference (Herzog 2015; Muhr 2008), RD brings people together and allows them to question what is just in the face of the others in the context of the event. Thus, while RD has transformed from a protest to an event in which everyone can participate, it still provides space for the participants to question what justice is, not in terms of predefined rules, but in terms of the affective unfolding of the event itself.

While everyone is free to participate within the sphere of RD, the majority of patrons seem to reject commercial appropriation and attempts to profiteer. This can be understood as a way of defining the limits of their generosity and constitutes a key dimension of Levinasian justice (Rhodes 2012; Staricco 2016). To counter commercial appropriation activities, participants use their financial means to discourage behaviors that diverge from the spirit of the event. Participants then deal ‘economic justice’ (Burggraeve 1995) by dividing their financial means among the restaurants, which discourages activities aimed at commercial appropriation. These limits are also collectively discussed on different social media platforms where participants negotiate what is right and wrong in the context of RD.

Based on this, what we discover is the possibility of Levinasian ethics manifesting in events of collective consumption that subvert the status quo. In mundane social encounters, especially with strangers, people are overwhelmingly inclined to follow rules and social norms rather than voluntarily adopt personal responsibility (Herzog 2015; Roberts 2001), particularly when it comes to anything like relations based on business practices (Bevan and Corvellec 2007; Jones 2003). This leads to doubt concerning whether Levinasian ethics is really possible in any sense (e.g., Introna 2009). However, we feel that a consumer gathering such as RD can offer us glimpses of possible Levinasian ethical relations that create openings for alternative modes of living. Within this fleeting domain of sociality, a tentative glance towards the Other can be raised, and an ethical awakening can thus become possible.

The ‘trace’ of RD in the City

RD marks an awakening of personal responsibility through its temporary subversion of contemporary city life. Within the city, people normally live anonymously through the enactment of a general order of laws, rules, and norms and often without the historical bonds or traditions that would bring them closer relationally (Herzog 2015). As an event, RD provides a temporary reminder of the possibility of being otherwise, as it brings strangers-cum-participants into face-to-face contact with each other. For Levinas, this possibility is the ‘trace’ (déchet), an affective ‘remainder’ or excess that marks all social activity (also Bergo 2011; Yar 2001). This is the “other extremity to all utility” as the elusive reminder of the Other “occupies the field of the déchet” (Lechte 2018, p. 108). It cannot be straightforwardly represented, for it is something hidden but unbearable, an affective background inscription, or an “order that orders me to the other [and which] does not show itself to me, save through the trace of its reclusion” (Levinas 2016, p. 140). One might venture to say that the trace of RD is the very thing missing in city life, the possibility of life being otherwise: a ‘secret’ securely hidden in plain sight that allows for the possibility of being in a ‘society otherwise’ (also Boothroyd 2011; Introna 2009).

Our analysis shows how this possibility of being otherwise is actualized in RD through new and unexpected experiences, opportunities to break bread with strangers, the potential to assume personal responsibility of one’s actions, and the chance to negotiate what is just among participants. These possibilities implicitly remind the participants that a different kind of sociality is possible. Simultaneously, they provide a contrast and a point of comparison to the otherwise impersonal nature of city life, as participants come to tacitly recognize the difference between what is and what could be. Thus, it might be that RD speaks to our desires and hidden guilt for living indifferently by, in its own way, showing us that other sensibilities are not entirely out of reach, even if they can only appear in a carnivalesque inversion of norms (also Hietanen et al. 2016). While Levinas maintains that in contemporary city life the social is manifested in indifference and self-centeredness and can thus never bring about forms of ethical responsibility (Herzog 2015), the trace of RD may nevertheless offer a glimpse of how ethical subjectivity is ‘called into existence’ (see Boothroyd 2011).

A Levinasian perspective opens up for theorizing collective ethicality that does not manifest normatively in pronouncedly hierarchical forms within a group, nor as adversarial tensions between groups (cf. Kates 2002; Luedicke et al. 2009). Instead, what we have attempted to show is that RD can be seen as a rupture in the status quo of city life, and its ephemeral trace is the possibility of a city otherwise. In the ways that people come together during RD, it also invokes the potential of justice, where in every social moment there is also a thirdness that relates to all other potential participants and the city itself (Boothroyd 2009; Herzog 2015). The immanent sensibility of justice then, even if only short-lived, opens the trace of a utopian city and all the social relations within. While any long-term effects of RD are debatable, it is nevertheless a grand-scale example of the kind of event to which our desires are attuned. However, as with all carnivalesque inversions of social order, this example remains a fleeting one, as its institutionalization would in turn make it a totalizing one. Still, as a contrast to ordinary life, RD provides a lasting trace of what could be.

Developing ‘ethical surplus’ Further

The infrequent investigations of ‘consumer ethics’ have tended to be constructed on the basis of a taken-for-granted normativity of social relations guided by the societal logics of commodity capitalism (cf. Vitell 2003; also Bradshaw and Zwick 2016). It is also evident that, on the surface level, RD produces a platform for commercial exchange between participants (Hietanen et al. 2016). However, if we take a closer look, allow ourselves to be grasped by the spirit of the moment, acknowledge the scents in the air, and thus see the city in a different light, an affective excess beyond exchange logic is produced. It is manifested in how the participants break bread with strangers to produce new ways of being collectively together in the moment. We see in this effervescence a Levinasian approach to ethical surplus, a collective revelation in the face of the abstract Other, even as the concept has been founded and developed rather differently by the sociologist Adam Arvidsson (see 2005, 2009, 2011).

Arvidsson (2005) theorizes that ethical surplus is a shared affective sense of collectivity that companies try to tap into and commercialize when interacting with consumer communities. However, a Levinasian view of surplus would instead suggest that it is the very intangibility and indeterminability of responsibility in the face of otherness that is at the core of his emergent ethics. Thus, this surplus for Levinas would be what cannot be commercialized, as any such act would immediately render the surplus into a totality that can be approached and manipulated under the logic of utility and gain (also Zwick and Bradshaw 2016). This surplus, and along with it the trace of how city life could be otherwise, is what entices people to partake in RD in an open and indeterminate fashion.

While Arvidsson’s general notion that communities revolve around particular brands in “affectively significant relations” (Arvidsson 2011, p. 270) bears resemblance to our approach, his notion of the ‘ethicality’ of these socially productive interactions remains largely goal-directed and normative. It arises from the Aristotelian tradition of a moral duty to the polis, but he also invokes Levinas by stating that his approach “comes fairly close to what […] Lévinas […] understood by ethics” (Arvidsson 2011, p. 268). Nevertheless, his logic of ‘ethics’ consistently stays in the realm of community building, and what for Levinas would also entail social relations of strictly totalizing tendencies (see Herzog 2015). As Zwick (2013) has already argued, Arvidsson tends to equate ethicality with sociality as, for him, “it is around social organization, or better around ethics” (Arvidsson 2009, p. 18) that value in consumption is to be conceptualized. This allows Arvidsson to postulate ‘community’ as a principle of ethicality that is inseparable from social orders that manifest under the logics of commodity capitalism and corporate environments. Thus, Arvidsson does not seem to be concerned with the “cynical appropriation of social productivity and collective creativity” (Zwick 2013, p. 396) by commercial interests, and rather continues to promote an empowered ethos of social cohesion that would bring about ‘productive’ outcomes in a society where social relations are increasingly seen only through the lenses of servitized market contexts (Zwick 2013; also Hietanen et al. 2018).

For us, a Levinasian view would seem to suggest otherwise in its precondition of deep humility, guilt, and a personal encounter with the overwhelming infinitude of the Other. One should also note the totalizing tendencies of hegemonic communities as they are often “Self-consciously created communities [that] are almost bound to be based on an us vs. them mentality” (Fred Alford 2014, p. 258), and active in producing homogenized groupthink against ‘enemies’ in order to “neutralize otherness” (Muhr 2008, p. 186; also Luedicke et al. 2009). Arvidsson (2009, 2011) goes on to note that consumers create forms of affective belonging that managers can co-opt for value production and also go on to co-creatively produce with them. While interactions involving brands may indeed provide a ‘sense of affinity’, in this account ethicality can also readily coincide with social competition verging on mob mentality (Zwick 2013; also Luedicke et al. 2009). From our alternative Levinasian perspective, an ‘ethical surplus’ that is so closely linked with goal-directed production of ‘value’ cannot claim to be ethical in the first place.

While our Levinasian approach to collectivity that opens up the potential for social interactions irreducibly beyond conventional market-based logics may depart from Arvidsson, we nevertheless wish to argue for an ‘ethical surplus’ that works precisely because it offers an affective potential for sociality beyond the market. While managers may indeed wish to harness this abstract alterity (Zwick and Bradshaw 2016), it is, as we have attempted to show in the case of RD, precisely what cannot be totalized by bringing it back into the fold of the market. What RD offers is not revolution or total rupture, but rather a momentary ‘revelation’ of an affective ‘remainder’: a trace of a possibility, if only a possibility, for being otherwise in city life in terms of an ethical responsibility for an unknowable Other. We hope our Levinasian reading and approach can bring about further imaginings of collective ethicality as an emergent becoming.

Notes

References

Aasland, D. G. (2009). Ethics and economy: After Lévinas. London: MayFlyBooks.

Arnold, S. J., & Fischer, E. (1994). Hermeneutics and consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(1), 55–70.

Arnould, E. J., & Wallendorf, M. (1994). Market-oriented ethnography: Interpretation building and marketing strategy formulation. Journal of Marketing Research, 31(4), 484–504.

Arvidsson, A. (2005). Brands: A critical perspective. Journal of Consumer Culture, 5(2), 235–258.

Arvidsson, A. (2009). The ethical economy: Towards a post-capitalist theory of value. Capital and Class, 33(1), 13–29.

Arvidsson, A. (2011). Ethics and value in customer co-production. Marketing Theory, 11(3), 261–278.

Arvidsson, A., & Caliandro, A. (2015). Brand public. Journal of Consumer Research, 42(5), 727–748.

Askegaard, S., & Linnet, J. T. (2011). Towards an epistemology of Consumer Culture Theory: Phenomenology and the context of context. Marketing Theory, 11(4), 381–404.

Bergo, B. (2011). The face in Levinas: Toward a phenomenology of substitution. Angelaki, 16(1), 17–39.

Bevan, D., & Corvellec, H. (2007). The impossibility of corporate ethics: For a Lévinasian approach to managerial ethics. Business Ethics: A European Review, 16(3), 208–219.

Boothroyd, D. (2011). Off the record: Levinas, Derrida and the secret of responsibility. Theory, Culture and Society, 28(7–8), 41–59.

Bradford, T. W., & Sherry, J. F., Jr. (2015). Domesticating public space through ritual: Tailgating as vestaval. Journal of Consumer Research, 42(1), 130–151.

Bradshaw, A., & Zwick, D. (2016). The field of business sustainability and the death drive: A radical intervention. Journal of Business Ethics, 136(2), 267–279.

Brown, J. W. (2002). What ethics demands of intersubjectivity: Levinas and Deleuze on Husserl. International Studies in Philosophy, 34(1), 23–37.

Burggraeve, R. (1995). The ethical meaning of money in the thought of Emmanuel Lévinas. Ethical Perspectives, 2(2), 85–90.

Denzin, N. K. (2001). The seventh moment: Qualitative inquiry and the practices of a more radical consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(2), 324–330.

Fred Alford, C. (2014). Bauman and Levinas: Levinas cannot be used. Journal for Cultural Research, 18(3), 249–262.

Gollnhofer, J. F., Weijo, H. A., & Schouten, J. W. (2019). Consumer movements and value regimes: Fighting food waste in Germany by building alternative object pathways. Journal of Consumer Research, 3, 11. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucz004 (Epub ahead of print 7 February 2019)

Hand, S. (2009). Emmanuel Lévinas. London: Routledge.

Herzog, A. (2015). Levinas on the social: Guilt and the city. Theory, Culture and Society, 32(4), 27–43.

Hietanen, J., Rokka, J., & Schouten, J. W. (2014). Commentary on Schembri and Boyle (2013): From representation towards expression in videographic consumer research. Journal of Business Research, 67(9), 2019–2022.

Hietanen, J., Mattila, P., Schouten, J. W., Sihvonen, A., & Toyoki, S. (2016). Reimagining society through retail practice. Journal of Retailing, 92(4), 411–425.

Hietanen, J., Andéhn, M., & Bradshaw, A. (2018). Against the implicit politics of service-dominant logic. Marketing Theory, 18(1), 101–119.

Hill, T., Canniford, R., & Mol, J. (2014). Non-representational marketing theory. Marketing Theory, 14(4), 377–394.

Introna, L. D. (2009). Ethics and the speaking of things. Theory, Culture and Society, 26(4), 25–46.

Jarzabkowski, P., Bednarek, R., & Lê, J. K. (2014). Producing persuasive findings: Demystifying ethnographic textwork in strategy and organization research. Strategic Organization, 12(4), 274–287.

Jones, C. (2003). As if business ethics were possible, within Such Limits... Organization, 10(2), 223–248.

Joy, A., Sherry, J. F., Jr., Troilo, G., & Deschenes, J. (2010). Re-thinking the relationship between self and other: Lévinas and narratives of beautifying the body. Journal of Consumer Culture, 10(3), 333–361.

Kates, S. M. (2002). The protean quality of subcultural consumption: An ethnographic account of gay consumers. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(3), 383–399.

Kennedy, B. L., & Thornberg, R. (2018). Deduction, induction and abduction. In U. Flick (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative data collection (pp. 49–64). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Knudsen, B. T., & Stage, C. (2015). Affective methodologies: Developing cultural research strategies for the study of affect. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kozinets, R. V. (2002). Can consumers escape the market? Emancipatory illuminations from Burning Man. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(1), 20–38.

Lash, S. (1996). Postmodern ethics: The missing ground. Theory, Culture and Society, 13(2), 91–104.

Lechte, J. (2018). Heterology, transcendence and the sacred: On Bataille and Levinas. Theory, Culture and Society, 35(4–5), 93–113.

Levinas, E. (1979/1961). Totality and infinity: An essay on exteriority. London: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Levinas, E. (1985/1984). Ethics and infinity: Conversations with Philippe Nemo. Pittsburg, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Levinas, E. (1987/1947). Time and the Other. Pittsburg, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Levinas, E. (1988/1947). Existence and existents. Dorchester: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Levinas, E. (1994/1982). Beyond the verse: Talmudic readings and lectures. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Levinas, E. (1996c/1951). Is ontology fundamental? In A. T. Peperzak, S. Critchley & R. Bernasconi (Eds.), Emmanuel Lévinas: Basic philosophical writings (pp. 1–10). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Levinas, E. (1997/1963). Difficult freedom: Essays in Judaism. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Levinas, E. (2007/1987). Sociality and money. Business Ethics: A European Review, 16(3), 203–207.

Levinas, E. (2016/1981). Otherwise than being or beyond essence. Pittsburg, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Levinas, E. (1996a/1962). Transcendence and height. In A. T. Peperzak, S. Critchley & R. Bernasconi (Eds.), Emmanuel Lévinas: Basic philosophical writings (pp. 11–32). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Levinas, E. (1996b/1968). Substitution. In A. T. Peperzak, S. Critchley & R. Bernasconi (Eds.), Emmanuel Lévinas: Basic philosophical writings (pp. 79–95). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Linstead, S. (1993). From postmodern anthropology to deconstructive ethnography. Human Relations, 46(1), 97–120.

Loacker, B., & Muhr, S. L. (2009). How can I become a responsible subject? Towards a practice-based ethics of responsiveness. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(2), 265–277.