Abstract

Entrepreneurship is increasingly considered to be integral to development; however, social and cultural norms impact on the extent to which women in developing countries engage with, and accrue the benefits of, entrepreneurial activity. Using data collected from 49 members of a rural social enterprise in North India, we examine the relationships between social entrepreneurship, empowerment and social change. Innovative business processes that facilitated women’s economic activity and at the same time complied with local social and cultural norms that constrain their agency contributed to changing the social order itself. We frame emancipatory social entrepreneurship as processes that (1) empower women and (2) contribute to changing the social order in which women are embedded.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Increasing female involvement in entrepreneurial activity has been associated with the improved status of women, enhanced family and community well-being and broader societal gains (Ardrey et al. 2006; Jamali 2009; Mayoux 1995; Servon 1997; Servon and Doshna 2000; Scott et al. 2012). However, social and cultural norms that prescribe women’s roles limit their access to education and restrict their networks which are known to impact on the extent to which women do paid work (Sen 1993a; Subramaniam 2011). We elaborate a model of emancipatory social entrepreneurship (ESE) based on processes that enable women to increase their agency, and at the same time open up opportunities for changing the social order in which they are embedded. We present evidence from a social enterprise established to enable women to earn income and enhance their social standing.

Conventional entrepreneurship has been linked to the discovery of opportunities, innovation and the creation of new business ventures and is implicitly associated with the pursuit of commercial objectives separate from, and perhaps in conflict with, ethical behaviour (Clarke and Holt 2010; Sen 1993b). In contrast, the emergence of social entrepreneurship, with its focus on “the innovative use of resources to explore and exploit opportunities that meet a social need in a sustainable manner” (Sud et al. 2009, p. 203), presents a more ethical variant of entrepreneurial activity, with an explicit social change agenda (Branzei 2012). Social entrepreneurship offers solutions to a range of social problems (Nicholls 2006) and is acknowledged to be an effective mechanism for generating economic, social and environmental value (Acs et al. 2013; Austin et al. 2006; Murphy and Coombes 2009). Social entrepreneurship has also been associated with wider social change processes (Acs et al. 2013; Alvord et al.2004; Mair et al. 2012a, b; Mair and Martí 2009; Steyaert and Hjorth 2006); however, we know little about how social entrepreneurship leads to social change.

The relationship between social entrepreneurship and social change is of particular interest in our study. While social entrepreneurship is explicitly oriented towards creating social and environmental value, the impact in terms of changing the social order in which actors are embedded is rarely articulated a priori. This raises intriguing questions about how local practices of social entrepreneurship might be related to broader level social change. More specifically, our study sought to address the following question: ‘What is the relationship between women’s membership of a social enterprise, their empowerment and social change’? We bring together theoretical frameworks from entrepreneuring (e.g. Rindova et al. 2009; Steyaert 2007) and empowerment (Kabeer 1999; Mosedale 2005; Sen 1999) to examine this relationship. We investigated the case of Mahaul, a social enterprise in Gujurat. Mahaul was formed by women with the support of a nongovernmental organization (NGO), and its operating principles are based on the development of a financially sustainable business model, income generation, and women’s empowerment. The case study was purposefully selected to explore the research question in depth (Patton 2002), as the venture espoused commitment to improving the lives of women and therefore presented an opportunity to examine the practices of a social enterprise that claims a female empowerment agenda. Using evidence from Mahaul, we seek to augment current understanding of social entrepreneurship and social change.

Our study contributes to our understanding of ethics and social entrepreneurship in three ways. The advancement of social change is central to definitions of social entrepreneurship, yet we know little about how impacts at individual level translate into social change. Increasing women’s income does not automatically lead to their empowerment (Leach and Sitaram 2002; Mansuri and Rao 2004; Murthy et al. 2008; Narayan 2002) and may even decrease empowerment (Kantor 2005). By investigating how involvement in a social enterprise empowers women to influence both, how they use their time and how family income is spent, we show how individual agency contributes to social change. Second, our analysis of the lives of women joins the small body of research that has investigated how membership of a collectively owned social enterprise politically empowers women (Datta and Gailey 2012; Mair et al. 2012b) through their participation in organizational governance and collective action (Murthy et al. 2008; Rowlands 1995; Subramaniam 2011). Third, the design of the operating processes and structures of Mahaul is embedded in local cultural values in that handicraft production is seen as a female occupation that does not impact on male employment and is, therefore, in line with gendered ideas about work (Amin 1997). However, at the same time, innovative production methods and opportunities for involvement in representation activities in the social enterprise offer women a path for incrementally increasing economic, cultural and political empowerment and in so doing increase the power they have over their actions.

Entrepreneuring

The concept of entrepreneuring is grounded in the diverse practices and outcomes associated with entrepreneurial efforts (Steyaert 2007; Johannisson 2011). It is a processual perspective that extends entrepreneurship beyond the creation of wealth to include action that brings “about new economic, social, institutional and cultural environments” (Rindova et al. 2009, p. 477). The emphasis thus shifts from considering entrepreneurship as an economic activity that may have social change outcomes to a process that is oriented towards “social change with a variety of outcomes” (Calás et al. 2009, p. 553). Consider now the links between entrepreneuring, emancipation and social entrepreneurship (Rindova et al. 2009).

Entrepreneuring orientates the focus of entrepreneurial activity towards the pursuit of freedom and autonomy relative to an existing position (Rindova et al. 2009). Similarly, the grand narrative of emancipation is also concerned with hopeful aspirations for autonomy (Branzei 2012) by breaking free from the power of another and, by breaking free from the existing social order, is inherently linked with disrupting the status quo. Thus, the purposes of entrepreneuring and emancipation are aligned in seeking to advance change. The discovery of how change is achieved rests on elucidating the micro-processes of emancipation from the narratives of actors’ participation with, and experiences of, local projects (Alvesson and Willmott 1992) and in so doing acknowledges their embeddedness in local structures (Mair et al. 2012b). Emancipatory entrepreneuring is framed in terms of three processes: seeking autonomy, authoring and making declarations. Seeking autonomy involves breaking free from authority and breaking up the constraints in an actor’s environment to create new possibilities. These processes involve discovering and amplifying fissures in otherwise stable social and economic relationships that impose constraints on certain types of activities that the actor, or others, may value (Rindova et al. 2009). Social change is thus grounded in the removal of constraints that prevent or hinder progress (Rindova et al. 2009). For example, work integration social enterprises (WISEs) aim to help individuals excluded from labour markets to break free from unemployment (Defourny and Nyssens 2006). WISEs deliver education and training services to enable those without paid work to overcome, and break up, the knowledge and skills barriers that prevent them from securing employment. Coaching and mentoring are also sometimes provided to guide new behaviour patterns required for regular employment. However, organizational processes designed to break free and break up do not disclose the individual strategies adopted by actors in their efforts to break free from the barriers that constrain them.

Having broken free from existing authority structures, entrepreneuring next involves authoring new relations. Authoring describes the (re)organizing processes of resource exchange in the context of existing structures, and is thus not an outright rejection of existing arrangements but rather the design of new arrangements that support intentions to change (Rindova et al. 2009). Authoring is an important component of successful change programmes (Maitlis and Lawrence 2007), and the dialectic of accommodating existing constraints and mobilizing resources from strongholds of power to forge new arrangements situates authoring in the micro-processes that interrelate structure and agency (Giddens 1984). At the same time, authoring emphasizes the organizing processes that propel change (Goss et al. 2011). For example, social enterprises in the financial sector—e.g. community development finance institutions (CDFIs) and credit unions—provide financial services and support to clients excluded from access to mainstream financial services; indeed, some CDFIs make it a condition for business lending that a client has been unable to obtain a commercial bank loan (Kneiding and Tracey 2009). CDFIs comply with the structural arrangements of financial regulations and, at the same time, author new ways of lending and supporting individuals and enterprises to develop and create wealth in deprived communities (Benjamin et al. 2004). To understand how actors author new relations, we need empirical data about the strategies that they pursue in designing new arrangements to support change.

Finally, making declarations involves unambiguous discursive and rhetorical acts about the actor’s intentions to create change (Rindova et al. 2009); declarations position the entrepreneuring project in “webs of meaning within which stakeholders interpret the value of products and activities” (op cit p. 484). Declaring is communicated to stakeholders in stories, narratives and symbolic actions that are oriented towards influencing interpretations and effecting change. The content of stories might explicitly expose contradictions between the existing and intended positions in an effort to generate stakeholder support for social change. For example, publications that document the emergence of international social enterprises, such as Grameen Bank (Yunus 2003, 2008) and the Big Issue (Bird 2002), are replete with narratives of individual change that declare the personal impact of social entrepreneurship. These high-profile stories raise awareness of how social entrepreneurship has helped individuals to overcome barriers to inclusion and serve as both examples and exemplars of change. Yet at the level of the mundane, we know little about the micro-level actions that actors take to create change for themselves and others in the future.

In summary, the concept of entrepreneuring is characterized by the constructs of breaking free and breaking up, authoring and declaring. Few studies to date have adopted entrepreneuring to study social entrepreneurship (for exceptions see Barros (2010) and Mair et al. (2012b)). Our research, therefore, extends a small and important body of work that examines processual aspects of social entrepreneurship (Mair and Martí 2009). In our empirical analysis, we find that entrepreneuring and social entrepreneurship fit well together but that two further constructs are also integral to social change. Through our case study analysis, we suggest that these two additional constructs, empowering women and changing social norms, when combined with the constructs identified in the existing literature on entrepreneuring, produce a framework for emancipatory social entrepreneurship (ESE).

Inequality

The empowerment of women is “one of the central issues in the process of development” (Sen 1999, p. 202), and the unequal treatment of women in developing countries continues to be an ethical and development dilemma (World Bank 2011). The decision to work is not a woman’s own, as her actions are influenced by men and linked to family and cultural well-being. Attitudes of family members and communities towards women doing paid work, and economic and social circumstances that resist change in these attitudes are known to constrain women’s independence and autonomy (Basu 1992; Sen 1993b; Subramaniam 2011). Evidence that development strategies based on encouraging women to participate in economic activity are impeded by such social and cultural barriers has been reported from Africa (Scott et al. 2012), Bangladesh (Mair et al. 2012b) and Pakistan (Roomi and Parrott 2008).

In South Asia, for example, norms of female seclusion and gender segregation regulate social interaction (Leach and Sitaram 2002; Murthy et al. 2008; Roomi and Parrott 2008; Subramaniam 2011). These norms determine with whom women socialize; interactions tend to be restricted to members of their immediate family (Kantor 2005), and the lack of opportunity to interact with other people restricts women’s networks (Jones et al. 2012; Subramaniam 2011). In patriarchal societies, male relatives are dominant; norms also prescribe women’s roles and responsibilities, and gender violence is not uncommon, especially in poor rural areas (Jejeebhoy 1998). From an early age, girls are expected to perform household duties, and after marriage they are responsible for housekeeping and raising children (Kantor 2005). If women engage in other activities, this is achieved by lengthening their day with little reduction in time spent on domestic duties (Silver 1993). Social and familial controls further restrict women’s capacity to make decisions independently (Shabbir and Di Gregorio 1996), and family controls on their mobility preclude them from being away from the home for activities other than those related to the household (Kantor 2005). To some extent, business processes that enable women to participate in home-based entrepreneurial ventures overcome these barriers. Thus, in contrast to developed countries where home-based working offers poor returns (Thompson et al. 2009), home working offers a solution to restrictions on women’s mobility, family responsibilities and a route out of poverty. In Muslim countries, women are considered the repository of family honour, and their chastity and good reputation are valued and guarded (Shaheed 1990). Female economic activity is thus controversial, as it might be perceived as dishonouring the family (Epstein 1993). Constraints associated with patriarchal family and kinship systems shape gender relations and restrict women’s mobility and participation in public life at the same time as conferring protection; by resisting or challenging these norms women risk losing this protection (Kabeer 2011). Finally, there is the problem of incentives. Despite the contribution of income to the household, patriarchal family and social structures limit women’s access to the proceeds of their own labour (Jiggins 1989). Gendered patterns of control over income mean that money belongs to the man irrespective of who earned it (Kantor 2005; Leach and Sitaram 2002). Women therefore have few direct incentives to do paid work unless they can adjust the length and structure of their working day and can keep the proceeds from their efforts.

The social and cultural norms outlined mean that historically Indian women have accepted silence and repression (Subramaniam 2011), and not pursued alternative ways of living their lives. The reality for women in rural communities in developing countries is that, unless destitute, obligations to family are prioritized above economic agency. Yet women’s well-being is strongly influenced by the “ability to earn an independent income, to find employment outside the home, to have ownership rights and to have literacy and be educated participants in decisions within and outside the family” (Sen 1999, p. 191). Since opportunities to escape from poverty are limited by women’s lack of resources, poor social networks, few marketable skills and limited life spheres (Jones et al. 2012); the type of work they can do is likely to be linked to existing social and cultural arrangements e.g. the rural tradition of employment in agriculture, and culturally preserved skills e.g. making handicrafts. Any attempts to bring about change in the status quo thus “cannot but draw on the agency of women themselves in bringing about such a change” (Sen 1999, p. 190).

Empowerment

Empowerment is concerned with removing unjust inequalities in the capacity of an actor to make choices, and any attempt to increase empowerment will involve disrupting the existing status quo and moving from a position of being unable to exercise choice to a position of doing so. To be empowered thus presumes that an actor must at some time have been disempowered (Mosedale 2005; Rowlands 1995) and participation in forms of associational life outside the family and kinship networks provide a vantage point from which to evaluate such unequal relationships (Kabeer 2011; Mair et al. 2012b). Female empowerment consists of several dimensions (Mayoux 2000): economic empowerment from access to income, which in turn may confer greater influence on decisions as to how income is spent; increased confidence and physical well-being resulting from decisions to spend money on themselves and their children; social empowerment resulting from increasing their status in the community; and political empowerment from increased participation in public life. In our study, we adopt the definition of empowerment as the processes through which women who “have been denied the ability to make strategic choices acquire such ability” (Kabeer 1999, p. 437). Female empowerment involves exposing the ways in which the power of existing gender relations shapes women’s choices and opportunities, and challenges them to formulate alternatives (Mosedale 2005; Wieringa 1994). Thus, the process of women’s empowerment enables women to individually exercise more power to shape their lives, refine and extend what is possible for them to do (Mosedale 2005), and hope for a different future (Branzei 2012). When these processes undermine the prevailing economic and social practices in the lived realities of women, they provide insight into how norms change (Murthy et al. 2008).

There is no agreed method for measuring empowerment (Mosedale 2005; Rowlands 1995; Quinn and Davies 1999); however, Kabeer (1999) proposes that exercising choice involves resources, agency and achievements. In life the rules and norms that govern the distribution and exchange of resources will give “certain actors authority over others in determining the principles of resource distribution and exchange” (Kabeer 1999, p. 437). Grass roots movements and Self Help Groups (SHGs) in India have been instrumental in empowering women by increasing their human and social capital (Batliwala 1993; Rose 1992; Subramaniam 2011). The early focus on collective mobilization of women (Subramaniam 2011), access to microfinance (Goetz and Gupta 1996; Kabeer 2001; Leach and Sitaram 2002; Mayoux 2002) and self-employment (Jumani 1993; Leach and Sitaram 2002; Rose 1992) has been succeeded more recently by rising interest in the potential of social entrepreneurship to empower women through sustainable community-based business models (Handy et al. 2011; Jones et al. 2012; Mansuri and Rao 2004). Innovative models that enable women to generate income, acquire new skills and expand their networks in ways that comply with existing norms are thus likely to have empowerment potential.

How resources are translated into the realization of choice introduces agency into empowerment (Kabeer 1999). Agency concerns the freedom to define one’s choices and goals and act upon them, even in the face of opposition from others (Kabeer1999). Exercising agency includes actions that are positive—e.g. decision-making and negotiation—as well as negative—e.g. deception, manipulation, subversion and resistance (Subramaniam 2011). The most frequently used concept to determine the presence of agency is that of control, usually operationalized in terms of having a say in relation to resources. Thus, increased agency might be interpreted from women’s narratives that refer to overcoming family resistance to their intentions and increased influence in family decisions about how resources are used.

Finally, the outcome of the combination of resources and agency is manifest in achievements (Kabeer 1999). However, the subtlety of changes in power relations and influence means that measuring empowerment is difficult (Rowlands 1995). The processes of gaining power and control are complex to achieve and measure; empowerment cannot be conferred, it can only be reflected upon after it has been secured. In addition, increasing women’s income and their empowerment do not always proceed together (Murthy et al. 2008; Narayan 2002; Rowlands 1995), in that income may increase without any change in status or relationships. Direct evidence of empowerment rests on the extent to which resources and agency have altered prevailing inequalities (Kabeer 1999). Typical indicators of empowerment include accounts of women’s financial autonomy, enhanced influence on family decisions and role sharing (Rowlands 1995; Kabeer 1999), especially where these were previously denied. Collectively, these achievements signal changes in individual and community expectations about women’s agency.

Our investigation into social entrepreneurship and social change is guided by three empirical questions. In the account of entrepreneuring as emancipation, the notion of constraints is broad and unspecified (Goss et al. 2011), yet understanding constraints is important, as it may give better insights into the processes through which change is created (Rindova et al. 2009). We therefore seek to identify the barriers to paid work faced by women and the strategies which they employ to overcome them. Second, social entrepreneurship has been propelled to the forefront of debates concerning social exclusion and disadvantage (Mair et al. 2012b; Steyaert and Hjorth 2006). We seek to identify how social enterprise business models and processes are designed to help women overcome the barriers that constrain their freedom. Finally, participation in entrepreneurial ventures has been associated with considerations of societal and cultural change (Steyaert and Hjorth 2006). To examine this aspect of social entrepreneurship, we investigate how women’s individual actions impact on, and change, established norms.

Methodology

The business model of Mahaul is based on selling traditional, rural handicrafts made by women to local, regional and international markets. Our primary and secondary data reveals how the adoption of innovative work processes enabled women to overcome social and cultural barriers that prevented them from doing paid work. Through membership of Mahaul, the women were economically, personally, socially and politically empowered. In turn, their empowerment led to four changes, in men’s attitudes towards women and paid work; the underlying power relations with the family unit, as women increased their influence in how household income was spent; attitudes towards gender discrimination, as women sought to ensure that their daughters would complete primary education and learn a marketable skill; and men’s roles in the family unit, as they supported the women’s work.

Our decision to employ a qualitative methodology was influenced by three factors. First, details about the daily lives of women in impoverished rural communities in developing countries are few; their world is typically hidden from view and we know little about the strategies they adopt to survive (Murthy et al. 2008). Second, investigating the lives of women in patriarchal cultures raises issues concerning power differences, access to informants and perceived social desirability of responses that can be better managed through depth interviews with informants than quantitative research techniques. Finally, high levels of female illiteracy in India directed us towards oral collection of data. We use the single case study method (Yin 1994) together with naturalistic inquiry (Lincoln and Guba 1995). We adopted an interpretive research strategy (Patton 2002) to understand the social and cultural frames of reference of our informants, the nature of their day-to-day realities and the rationales they employed in their narratives.

Information was gathered in two stages. Stage one consisted of four field visits to the region by the first author to understand the context and build relationships, longitudinal field attachment by the second author and interviews with 4 community development employees, 5 field workers and 8 members of Mahaul. The interviews with community development employees and field workers were conducted at the NGO centre and gathered information about the origins, structure, processes and outputs of Mahaul. The interviews with members were conducted at the Mahaul workshop, and the women were asked to talk about why and how they had joined Mahaul, how they managed their work and how the money they earned was used. The stage one interviews were content analysed and an interview protocol developed to gather information from a larger sample of members. The protocol was translated into Gujurati by a native speaker and used to interview 49 members of Mahaul (12.5 % of members in 2012). Informants were interviewed in their homes, and their narratives were recorded in extensive field notes. This strategy was adopted to help them be at ease, avoid rehearsed responses and minimize the formality of interactions. In addition, 42 documents relating to Mahaul that together constitute 631 pages of text were collated and analysed.

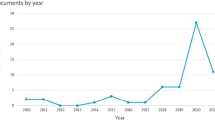

The data analysis used an interpretive approach (Strauss and Corbin 1998). To begin, close reading of the data was carried out to create a narrative of the events relating to the creation of Mahaul; for the first ten years, the venture was managed informally and no accurate records from this period exist, and thus informant accounts and secondary data were vital for creating the historical account. Data about sales and membership (Table 1) were pieced together from content analysis of the documents and interviews with community development employees and fieldworkers.

Next, the data from the interviews with Mahaul members were analysed, and key phrases associated with barriers and organizing processes at Mahaul were noted and extracted from the data. The extracts were manually coded and organized into first- and second-order codes that emerged naturally from the data. It was in the second stage of analysis that the dynamic and evolving process of creating Mahaul became clear and led to the decision to use the concept of entrepreneuring to frame the analysis. However, it also became apparent that entrepreneuring only partially explained the processes we had observed, and our data suggested two additional categories of activity. The data were then interrogated to unpack the linkages between the women’s actions and broader level social changes.

Research Context

India is the world’s largest democracy, and there are wide variations in wealth in the population of more than 1 billion. It is estimated that 42.5 % of Indians live below the poverty line and survive on less than $1.25 a day (World Bank 2005). After the introduction of the 1991 Structural Adjustment Programme, “the alleviation of poverty has been a major objective of planned development in India” (Nayyar 1996, p. 171). Strategies to create employment rely on two principal methods: supporting industries that require large numbers of employees, such as services, and encouraging industries that employ labour intensive technologies and products. In rural areas, government employment projects have included large public works programmes, e.g. infrastructure building and water conservation, and employment assurance schemes. The Integrated Rural Development Programme was designed to accelerate income generation and improve production and productivity in agriculture and non-agricultural industries. Despite these government interventions, the scale of demand for measures to alleviate poverty is vast and, as the Indian business model is to prioritise their social mission to help the country and its citizens above building shareholder value (Cappelli et al. 2010), it is not uncommon for corporations to support NGOs and invest in community development projects.

Our case study is located in the Okhamandal region of Saurashtra. The region is poor: more than 70 % of the rural population is dependent on agriculture; average per capita income is USD $1.59 (Government of Gujarat 2006); 56 % of the population is rural; and 73 % of employment is in agriculture. The region is drought prone with average annual rainfall of 8–10 inches, and households rely on the monsoon rain for their livelihood. Unemployment is high (61 % of men and 79 % of women are unemployed), and poverty is greatest in rural areas; the rural poor constitutes 64 % of the state’s poor (Hirway and Mahadevia 2004). In addition, high levels of gender discrimination constrain women’s access to education, girls are less likely than boys to complete primary school and there is resistance to sending girls to school.

In 1980, an NGO was established by a corporation to encourage and support social and environmental development in the Rabari, Satvara, Ahir and Darbar tribal communities near its production base. The NGO employs the methodology of participatory rural appraisal (PRA) (Chambers 1994) in community development work. PRA is a practical set of tools and methods that have been designed to enable communities to express, enhance, share and analyse their knowledge of life and local conditions and then use this knowledge to find ways to take action to solve local problems (Chambers 1994). PRA-trained fieldworkers collect information by working closely with communities and in doing so ensure that local knowledge is the foundation of future development. Commencing with creating an inventory of local knowledge, fieldworkers and communities work collaboratively to generate solutions that are actionable in the local context. The process ensures that information and solutions are owned and shared by local people and has been used in many countries to deal with issues such as natural resource management, agriculture, health, nutrition, food security and programmes for the poor (Chambers 1994).

The idea for Mahaul can be traced back to 1996 when community development employees at the NGO were actively seeking ways to help women find opportunities to earn money and raise their income above the poverty line. The business model is based on selling traditional handicraft products made by women in the rural villages. Girls traditionally embroider clothing and soft furnishings as a contribution to the family they marry into, and the patterns and motifs are distinctive, ornate and characteristic of the region. The emancipatory philosophy underlying Mahaul is grounded in empowerment through income generation, skills development and increasing women’s networks. The women’s own involvement in the creation of the social enterprise is explained thus:

So you go out in the communities and you are talking to your various groups and communities and when they come back and say ‘You know this is all we know, we’ve been doing this all our lives, can this help?’ So those kind of discussions, it comes from the community … We thought maybe if we could help these women put all their skills together and make a product which is relevant and which is saleable, marketable, we could help supplement the income of these women and thereby reduce the stress on them in terms of being able to have a decent livelihood in the area. (Community development employee)

Social Entrepreneuring

In this section, we employ the information from the second-stage interviews with 49 women to examine social entrepreneuring. Our informants are women from 20 different SHGs in the region, the age range extends from 30 to 45 and the average family unit has six children. Table 2 presents illustrative quotes for the constructs we elaborate.

Constraining Women’s Choices

Our interview data suggest that four barriers constrain women’s capacity to exercise choice (see Table 2). First, the women of the region have limited social networks and few opportunities to interact with people outside their family. After marriage, social norms confine them to the home and they rarely interact with other women. In the interviews, 38.7 % of women reported that their family was against them joining Mahaul, because they would have to go outside of the home. Of the 22.4 % of women whose families were not against them joining, 10.4 % referred to another person in the family already being a member. Second, although the women in the rural villages learn sewing and handicraft skills from an early age, their skills are difficult to commercialize as the quality of handicrafts was not high enough for sale on the open market. 38.7 % talked about how, after their sewing skills were assessed, they had needed training to meet the quality level requirements. Third, the level of female literacy is low, rarely beyond primary education, and their interaction with markets is generally limited to purchasing food. As a result, they found it difficult to make connections between their skills and potential markets. Finally, the separation of genders is deeply ingrained in the culture, especially in the rural communities where travel away from the home, unaccompanied or without family permission, is rare, and limits women’s access to education, training and information about different ways of living their lives. Together, these norms limit women’s agency in terms of mobility, opportunities to generate income and their personal development.

After joining Mahaul, when we go outside the town at that time my villagers used to do gossiping and also arguments occur for time management. To overcome this problem I showed the benefit of joining Mahaul through which my skill increased. (Interview 19).

Overcoming Constraints

The history of Mahaul is closely linked with the development of SHGs in the region. The SHGs were established in 1998 to provide access to microfinance and literacy and numeracy classes for women. The SHGs also arrange for women to visit other communities to learn about SHGs, and foster networks between women and linkages with formal institutions. The members of the SHG pay an annual membership fee of 25 Rupees. In exchange, they receive technical training to learn sewing and business skills and vocational training in leadership and gender. In the interviews, 51 % of women found out about Mahaul from their SHG and 49 % heard about it from women who were members of other SHGs.

Through their active engagement with men and women in the local villages, the community development employees and field workers were aware of the traditional handicrafts of the region; however, it was via the collaborative PRA processes that the women from the villages came forward with suggestions about how the products they made for their own domestic use might appeal to others. In keeping with PRA philosophy, the pace of development is set by the community and it took several years, and the support of the NGO and the SHGs, for the idea for Mahaul to be developed. Membership has increased to 400 women, although the extent of individual participation varies over time. For those women whose families were against them joining Mahaul, breaking free involved acts of resistance to cultural norms that constrained their ability to do paid work.

Initially they were not agreeing for my joining Mahaul. As initially they were not allowing me to go to Mahaul I used to speak lie to my husband and go to do this work. But as I started getting this work at home then they allowed me to do this work at home. (Interview 1).

Gaining Control

Authoring describes the design of new arrangements that are oriented towards change, yet are situated in the context of existing structures (Rindova et al. 2009). The interview analysis identified three activities through which the women sought to achieve change: training, work processes and governance structures. All women in the region who save with the SHGs are eligible to join Mahaul. However, as the handicrafts are destined for commercial markets, quality control is important. The sewing work is graded A (highest) to C (entry level). For sewing graded either B or C, training is organized and delivered by more experienced members, one-to-one, in the woman’s home. 61 % of the women had received training to improve their sewing skills. Participation in other learning opportunities included leadership training (46 %), capacity building (36 %), accounts and banking (28 %) and gender awareness (22 %). A few, 12 % of the sample, had attended formal training at a fashion college in a regional centre; this had required family approval to be away from the home, and participation was thus limited to younger women and those considered by the community to be ‘progressive’.

To comply with norms, Mahaul innovated flexible business processes so that members could complete the sewing work in the home. The work is brought to them in a ‘milk round’; a process of distributing work kits to homes, which is managed in association with SHGs. The preparation of the work kits, e.g. designing and patch cutting, fabric, thread, beads and mirrors, is carried out by ‘progressive’ women at the Mahaul workshop. The work kits are distributed to the women in the villages by the head of the SHG and a date agreed for completing and collecting the finished handicrafts. The average length of the route is 20 km, and the longest route is 40 km from the workshop. The finished work is collected and quality checked, and records of the work are maintained by the women and the head of the SHG. Payments are made monthly by Mahaul into the account of the SHG and then distributed in cash by the head of the SHG to the individual women. The ability to complete the sewing work in the security of their own home and fit it around household responsibilities was discussed as an important benefit by 22.4 % of the women. Other benefits mentioned were opportunities to contribute to family income (20.4 %), becoming more skilled at sewing (18.4 %), and opportunity to learn from other women (12.2 %).

In 2008, the assets and business were formalized into the Mahaul Trust. The Trust is organized on a democratic governance model that has been designed to give women responsibility for policy development and implementation. The Trust is a membership organization in which every member pays an annual subscription fee of 25 Rupees, and in exchange they receive sewing work and the right to participate in governance decisions concerning the management of the Trust. In the interview, 30 % reported that they attended all the meetings, 42 % attended regularly and 26 % attended rarely or not at all. Participation in public life is gaining in strength, and 20 % of women held a leadership position in their SHG and 6 % were board members of Mahaul. In the longer term, the plan is to convert the Trust to a cooperative, so that the women will be eligible to receive a share of the profits as well as income from sewing.

The training, home-based work processes and governance of Mahaul provide members with opportunities to improve their technical skills, learn about business, and participate in democratic processes without overtly challenging the social and cultural norms of the communities in which they live. The business model thus seeks to comply with existing conventions and social structures yet at the same time creating, with subtlety, avenues for social change. Indeed, the women expressed support for preserving some traditions at the same time as changing others.

I can contribute to the development of the children and my daughter gets a good education and learns new work. I can protect our customs and culture. (Interview 5).

Anchoring New Freedoms

Making declarations positions entrepreneuring in stories, narratives and symbolic actions to influence stakeholders and effect change (Rindova et al. 2009). In our empirical data, we identified three processes through which the women sought to secure, and help others to acquire, the freedoms they had gained. Since 2008, the Trust has invested in building a distinctive brand identity for Mahaul based on the empowerment of women through its business model. The brand has also helped the women’s families understand more about the work that the women do.

After I joined Mahaul the family members inform me that this is good work and I do such nice work in time so that the name of the family and the SHG is not spoiled. (Interview 4).

The Trust aims to professionalize the venture, by monitoring and controlling product quality and implementing management processes and strategic planning. The impact of the new management plan has been to reduce reliance on sales to the corporation associated with the NGO by developing new markets, expanding distribution to 6 outlets (2 shops and 4 retail concessions in India), exporting to China and selling on-line. The Trust has also collected the stories from some of the women, and these are disseminated through the website and NGO publications. The stories relate the impact of joining Mahaul on their lives e.g. attending training courses, sending children to school and improving their home. The purpose of the stories is to raise awareness of female empowerment by linking Mahaul products with direct benefits to the women and their families.

“My status has been increased in my house and in society. I am handling the responsibilities properly. After taking training, I had bought an embroidery machine, I can teach other women to be as self-dependent as I am. (Interview 38).

Emancipatory Social Entrepreneurship

Previous research has considered philosophical explanations of entrepreneuring (Steyaert 2007), the constituent processes of autonomy, authoring and declaring (Rindova et al. 2009), power (Goss et al. 2011), and contradictions between discourse and practice (Barros 2010). We now employ empowerment to explain ESE.

Empowering Women

Our empirical data found that membership of Mahaul empowers women in four ways. The average monthly earnings vary from less than 1,000 Rupees (20 %), between 1,000 and 2,000 Rupees (38 %), to 3,000 and 5,500 Rupees (32 %). Prior to joining Mahaul, 69.4 % of our sample had stayed at home and not done paid work, and of the remainder 16.2 % had earned money from sewing and handicrafts. Six women referred to doing other employment e.g. farming, labouring and tutoring. Our informants explained that the main reasons for joining Mahaul were to improve the family income (53 %) and earn a livelihood (14.2 %), to improve their sewing skills (4 %) and to save money with the SHG (2 %). The women’s narratives mentioned increases in confidence (65 %), freedom (42.8 %), pride and contentment (18.6 %) and independence (12.2 %). They also talked about gaining more respect from their community (14.2 %), being a role model for other women (12.2 %) and attending SHG and Mahaul meetings (Table 3).

My family feels that after joining Mahaul we are earning good income, my family’s financial condition is also better now and we have a good reputation in society also. Now people say that these ladies are successful. (Interview 43).

Evidence of empowerment and increased agency is revealed in their accounts of joining Mahaul. Some of our informants told us how their aspirations to join Mahaul had been ridiculed by their families and that they had had to argue, persuade and convince their families to let them do paid work. The threat of domestic violence, not uncommon in India (Ahmed-Ghosh 2004), meant that in not being compliant and by asserting their views, they put themselves at risk. The women’s stories about fitting their sewing work around their household duties and of how the money they earn is spent also reveals increased agency in determining how they organize their time and greater influence in family decision-making. 22.4 % specifically talked about being more able to manage their time and be more efficient in their household tasks.

My family thinks that after joining Mahaul ladies can learn many things, stand on her own feet, will gain experience and get a better life. Ladies can dream of a better future. My family members are proud of me – they have belief in me. Women have to change according to time and situation. (Interview 45).

Finally, the combination of resources and agency for members of Mahaul led to increases in household income and improvements in the quality of education of children and access to education for girls. In summary, the women could earn income, protect their own interests, build networks and gain independence through income generation. In this way, their membership empowered them to overcome the constraints that rendered them economically inactive and powerless in the family.

I am living a good life as I do not want to depend on anybody and want to live my life by doing hard work. I came to know how to face problems of life and my self-confidence increased. Now I can live my life by my own way so I am happy. (Interview 27).

Social Change

At the same time as increasing women’s agency, the prospects of longer term social change were created by securing women’s economic activity and widening their freedom of action. As women are likely to be given greater respect within their communities for conforming to its norms and to be penalized if they do not, behaviour that challenges norms incurs risk. Ahmed (2004) found that domestic violence against women who participated in empowering activities away from the home was perpetrated by men and encouraged by other family members. Our data link women’s empowerment to social change through four changes in family attitudes towards women and paid work; underlying power relations within the family unit; attitudes towards gender discrimination; and the role of men in the family unit. Extracts from our empirical data are presented in Table 3.

Changing Attitudes Towards Women and Paid Work

The narratives of how members had joined Mahaul revealed that many had overcome family resistance in order to do so. Their stories included accounts of arguing, criticism and domestic violence. For some women, initial family resistance had subsequently become active support of their activities—this was explained as resulting from the contribution of their earnings to family income.

Previously my husband was against the work but now he is cooperating. As my work and income started increasing then the protest of my family gets decreased. (Interview 13).

Changing Underlying Power Relations Within the Family Unit

The money earned by the women is distributed by the SHG, and 61 % of the sample told us that they decided how their earnings were spent, 16 % shared the decision with their husband and 12 % with their family. Their accounts refer to using money to pay for their children’s education (53 %), household expenses (28.5 %), to buy things for themselves (20.4 %), extra tuition for their children (14.2 %) and saving (14.2 %). In addition, 8 women had purchased equipment that would enable them to earn extra money e.g. sewing machines and kits to sell beauty treatments to other women. Our informants also told us how they used their earnings to build more solid housing (replacing mud and straw structure with fired bricks) and to buy gold jewellery. The increased influence of women in decisions concerning how the money they earn is spent reveals their increased power within the family and recasting their role from powerless to a contributor to family decisions.

I and my husband have to pay loan of our house. So by doing the work of Mahaul I used to help my husband in paying instalments of the loan. I started getting sewing work of Mahaul as I knew a few women in the SHG. Now we have started renovating work of my husband’s shop. My husband is saying you are my real better half as you are helping me in all my work. (Interview 38).

Changing Attitudes Towards Gender Discrimination

The low school attendance of girls in India has been attributed to parental attitudes that do not value the education of girls. In some parts of north India, more than 60 % of girls do not complete five years of primary education (UNICEF 2011). However, in their narratives, our informants talked about how they wanted a better future for their daughters, and their commitment to ensuring they completed primary school. Their earnings from Mahaul had increased their power within the family and their capacity to create a better future for their daughters.

In society a good impact of Mahaul has been created. It will be easier for my daughters to do things that I was not able to do. (Interview 26).

I will give advice to my daughter that to earn money by doing hard work do not depend on anybody as man and women are equal in society. (Interview 35).

Changing Role of Men in the Family Unit

The interviews with members also disclosed changing attitudes and behaviours of men in a traditional and patriarchal culture. In our sample, 26.5 % reported that their husbands would look after the children so that they could work or attend meetings, 18.2 % would help with house work and 6.1 % would help them complete the handicraft work.

I used to do work of Mahaul with my household work. I expect my husband that he do household work like he go pick up the children from school and go to market to buy vegetables. When I do Mahaul work at that time my mother in law do the household work. (Interview 1).

Critical Reflection

Our analysis of the relationship between social entrepreneurship and social change and the mediating role of empowerment has presented a generally positive account. However, a major criticism of enterprise approaches to development is that encouraging entrepreneurship is perceived to be part of the political ideology of capitalism and not in the interests of “developing countries, the poor or the marginalised” (Blowfield and Frynas 2005, p. 510). In the rush to create markets for the poor, the cultural differences and resource constraints faced by those living in developing countries are set aside in the global hegemony of capitalism. However, market-based approaches for women in resource-poor communities have been noted to generate positive impacts (Calás et al. 2009), and the Mahaul case study elaborates how ESE reshapes entrepreneurship to empower women in impoverished communities. Through collective structures, Mahaul has been able to secure economies of scale in purchasing and professional management practices e.g. quality control and on-line retailing, which lead to increased sales for products year on year. This has created income generation opportunities for 400 women in the region.

A second criticism relates to the social harm that might result from the empowerment of women in patriarchal cultures in which they are valued for their compliance with traditional norms and rules and in return in times of trouble the family and community will support them (Rajgor 2008). By increasing their economic, human and social capital, women are empowered to break free from existing social structures and constraints. Where their new freedoms are productive, the economic benefits might be seen as ‘fair exchange’ for the changing social structures. However, empowering on women risks alienating male relatives and undermining their masculine identity (Chant and Gutmann 2000) and role as the head of household (Leach and Sitaram 2002). If the women are unsuccessful, then there is a risk that their strong ties might have been traded for a broader network of weak ties that may not be robust enough to support them in difficult times. In our study, the community-based structure of Mahaul provided a network of support for members as they incrementally increased their economic, personal, cultural and political power which in turn enabled them to hope for a better future for themselves and their families, especially their daughters.

Finally, in addition to the role of the SHGs, Mahaul has been supported by an NGO established by a corporation, and there is always a risk that the development trajectory of the social enterprise may have been shaped by the agendas of the NGO and the corporation (Rein and Stott 2009). The nature of relationships between different categories of organizations has been investigated in a rich stream of research concerning cross-sector partnerships (see for example Le Ber and Branzei (2010a, b)). Of specific concern here are strategies adopted to bridge different aims, logics and agendas to create and capture social value and foster social change. Certainly, the corporation has an interest in helping the communities in which it is located to prosper; however, the adoption of PRA methods and open and voluntary membership of Mahaul goes some way to ensuring that the interests of the community are prominent in the goal structure of Mahaul.

Conclusion

Academic and policy interest in the economic lives of women in developing countries has been stimulated by evidence of the positive impacts of enterprising activity on poverty alleviation and the reserve of unused talents of women, especially for those living in rural areas. Centuries of gender inequality have been perpetuated by social and cultural norms that restrict women’s access to education, mobility, networks and freedoms. In countries with equal opportunities legislation, laws have had some impact on empowering and changing societal attitudes towards women. These advances are not universal, and NGOs have been active in helping women find ways to support themselves and their families. We have shown how social entrepreneurship also makes a contribution to empowering women and advancing social change.

We elaborated the concept of emancipatory entrepreneuring in the domain of social entrepreneurship, and from our analysis of a social enterprise, we developed a framework of ESE. The empowerment process focused on community participation in creating a social enterprise with an economic and empowerment agenda. Although oriented towards empowering individual women, over time the outcomes have been translated into changing attitudes towards women’s roles and status more generally. Our examination of the micro-processes of increasing women’s agency in a region of deep poverty uncovered the barriers to economic activity that impoverished rural women face and linked income generation to economic, social and political empowerment. Although the empirical data are limited to informants associated with one social enterprise, our contribution rests on access to a hard to reach group of people and the insights into the creation of small increments in changing the social order in which women are embedded.

Two suggestions for further research emerge directly from our study. We directed our attention towards examining the impacts of women’s membership of a social enterprise. This was a purposive choice and was determined by our interest in how women overcome the constraints of their embeddedness. However, the gendered nature of household duties combined with income generation might create a double burden for women. The consideration of men in the empowerment of women is emerging as an important theme in the scholarly literature (Scott et al. 2012). A follow-up study to investigate men’s attitudes towards women’s empowerment would be a valuable addition to knowledge about social change. Second, to investigate the relationships between membership of a social enterprise, empowerment and social change, we gathered narrative data from informants. This research strategy was appropriate for uncovering the barriers that women face, the challenges they overcame and how they exercise choice. This research strategy lends itself to wider research application to examine the impact of social entrepreneurship on women’s resources, agency and achievements in other regions and contexts to discover other models that advance women’s empowerment and social change.

We conclude by acknowledging that empowerment is not a purely female construct. Although gender inequality has tended to focus on women, breaking free from the power of another applies also to men. Our frame of ESE is based on data from a social enterprise committed to improving the lives of women, and research that investigated the empowerment of men, e.g. social enterprises that work with trafficked men, assist male refugees to claim asylum and the rehabilitation of male offenders, would make an important contribution to widening our knowledge of the relationship between social entrepreneurship, ethics and social change.

References

Acs, Z. J., Boardman, M. C., & McNeely, C. I. (2013). The social value of productive entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 40(3), 785–796.

Ahmed, S. (2004). Sustaining peace, re-building livelihoods: The Gujarat harmony project. Gender & Development, 12(3), 94–102.

Ahmed-Ghosh, H. G. (2004). Chattels of society. Domestic violence in India. Violence Against Women, 10(1), 94–114.

Alvesson, M., & Willmott, H. (1992). On the idea of emancipation in management and organization studies. Academy of Management Review, 17(3), 432–464.

Alvord, S. H., Brown, L. D., & Letts, C. (2004). Social entrepreneurship and societal transformation. Journal of Applied Behavioural Sciences, 40(3), 260–282.

Amin, S. (1997). The poverty-purdah trap in rural Bangladesh: Implications for women’s roles in the family. Development and Change, 28(2), 213–233.

Ardrey, W. J., Pecotich, A., & Shultz, C. J. (2006). Entrepreneurial women as catalysts for socioeconomic development in transitioning Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. Consumption, Markets and Culture, 9(4), 277–300.

Austin, J., Stevenson, H., & Wei-Skillern, J. (2006). Social and commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different or both? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(1), 1–22.

Barros, M. (2010). Emancipatory management: The contradiction between practice and discourse. Journal of Management Inquiry, 19(2), 166–184.

Basu, A. M. (1992). Culture, status of women and demographic behaviour. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Batliwala, S. (1993). Empowerment of women in south Asia: Concepts and practices. New Delhi: Asian-South Pacific Bureau of Adult education and Freedom from Hunger Campaign.

Benjamin, L., Sass Rubin, J., & Zielenbach, S. (2004). Community development financial institutions: Current issues and future prospects. Journal of Urban Studies, 26(2), 177–195.

Bird, J. (2002). Some luck. London: Hamish Hamilton.

Blowfield, M., & Frynas, J. G. (2005). Setting new agendas: Critical perspectives on corporate social responsibility in the developing world. International Affairs, 81(3), 499–513.

Branzei, O. (2012). Social change agency under adversity: How relational processes (re)produce hope in hopeless settings. In K. Golden-Biddle & J. Dutton (Eds.), Using a positive lens to explore social change in organizations: Building a theoretical and research foundation (pp. 21–47). London: Routledge.

Calás, M., Smircich, L., & Bourne, K. (2009). Extending the boundaries: Reframing ‘entrepreneurship as social change’ through feminist perspectives. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 552–569.

Cappelli, P., Singh, H., Singh, J., & Useem, M. (2010). The India way: Lessons for the U.S. Academy of Management Perspectives, 24(2), 6–24.

Chambers, R. (1994). Participatory rural appraisal (PRA): Challenges, potentials and paradigm. World Development, 22(10), 1437–1454.

Chant, S., & Gutmann, M. (2000). Mainstreaming men into gender and development. Oxford: Oxfam.

Clarke, J., & Holt, R. (2010). Reflective judgement: Understanding entrepreneurship as ethical practice. Journal of Business Ethics, 94(3), 317–331.

Datta, P. B., & Gailey, R. (2012). Empowering women through social entrepreneurship: Case study of a women’s cooperative. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(3), 569–587.

Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. (2006). Defining social enterprise. In M. Nyssens (Ed.), Social enterprise (pp. 3–26). London: Routledge.

Epstein, T. S. (1993). Female petty entrepreneurs and their multiple roles. In S. Allen & C. Truman (Eds.), Women in business: Perspectives on women entrepreneurs (pp. 14–27). London: Routledge Press.

Giddens, A. (1984). The social constitution of society. Cambridge: Polity.

Goetz, A. M., & Gupta, R. S. (1996). Who takes the credit? Gender, power and control over loan use in rural credit programs in Bangladesh. World Development, 24(1), 45–63.

Goss, D., Jones, R., Betta, M., & Latham, J. (2011). Power as practice: A micro-sociological analysis of the dynamics of emancipatory entrepreneurship. Organization Studies, 32(2), 211–229.

Government of Gujarat. (2006). Socioeconomic review, Gujarat state, 2005–2006. Ahmedabad: Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Government of Gujarat.

Handy, F., Cnaan, R. A., Bhat, G., & Meijs, L. (2011). Jasmine growers of coastal Karnataka: Grassroots sustainable community-based enterprise in India. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 23(5–6), 405–417.

Hirway, I., & Mahadevia, D. (2004). Gujarat human development report. Ahmedabad: Mahatma Gandhi Labour Institute.

Jamali, D. (2009). Constraints and opportunities facing women entrepreneurs in developing countries. Gender in Management, 24(4), 232–251.

Jejeebhoy, J. (1998). Wife-beating in rural India: A husband’s right? Economic and Political Weekly, 33, 855–856.

Jiggins, J. (1989). How poor women earn income in Sub-Saharan Africa and what works for them. World Development, 17(7), 953–963.

Johannisson, B. (2011). Towards a practice theory of entrepreneuring. Small Business Economics, 36(2), 135–150.

Jones, E., Smith, S., & Wills, C. (2012). Women producers and the benefits of collective forms of enterprise. Gender & Development, 20(1), 13–32.

Jumani, U. (1993). Dealing with poverty: Self-employment for poor rural women. New Delhi: Sage.

Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, agency and achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change, 30(3), 435–464.

Kabeer, N. (2001). Conflicts over credit: Re-evaluating the empowerment potential of loans to women in rural Bangladesh. World Development, 29(1), 63–84.

Kabeer, N. (2011). Between affiliation and autonomy: Navigating pathways of women’s empowerment and gender justice in rural Bangladesh. Development and Change, 42(2), 499–528.

Kantor, P. (2005). Determinants of women’s microenterprise success in Ahmedabad, India: Empowerment and economics. Feminist Economics, 11(3), 63–83.

Kneiding, C., & Tracey, P. (2009). Towards a performance measurement framework for community development finance institutions in the UK. Journal of Business Ethics, 86(3), 327–345.

Le Ber, M., & Branzei, O. (2010a). Value frame fusion in cross sector interactions. Journal of Business Ethics, 94(1), 163–195.

Le Ber, M., & Branzei, O. (2010b). (Re)forming strategic cross-sector partnerships. Relational processes of social innovation. Business and Society, 49(1), 140–172.

Leach, F., & Sitaram, S. (2002). Microfinance and women’s empowerment: A lesson from India. Development in Practice, 12(5), 575–588.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1995). Naturalistic inquiry. London: Sage.

Mair, J., Battilana, J., & Cardenas, J. (2012a). Organizing for society: A typology of social entrepreneuring models. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(3), 353–373.

Mair, J., & Martí, I. (2009). Entrepreneurship in and around institutional voids: A case study from Bangladesh’. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(5), 419–435.

Mair, J., Martí, I., & Ventresca, M. (2012b). Building inclusive markets in rural Bangladesh: How intermediaries work institutional voids. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4), 819–850.

Maitlis, S., & Lawrence, T. B. (2007). Triggers and enablers of sensegiving in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 57–84.

Mansuri, G., & Rao, V. (2004). Community-based and community-driven development: A critical review. The World Bank Research Observer, 19, 1–39.

Mayoux, L. (1995). Alternative vision or Utopian fantasy: Cooperation, empowerment and women’s cooperative development in India. Journal of International Development, 7(2), 211–228.

Mayoux, L. (2000). Micro-finance and the empowerment of women. A review of the key issues. Social finance working paper (23), Geneva: International Labour Organization.

Mayoux, L. (2002). Microfinance and women’s empowerment: Rethinking ‘best practice’. Development Bulletin, 57, 76–80.

Mosedale, S. (2005). Assessing women’s empowerment: Towards a conceptual framework. Journal of International Development, 17(2), 243–257.

Murphy, P. J., & Coombes, S. M. (2009). A model of social entrepreneurial discovery. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(3), 325–336.

Murthy, R. K., Sagayam, J., Rengalakshmi, & Nair, S. (2008). Gender, efficiency, poverty reduction and empowerment: Reflections from an agriculture and credit programme in Tamil Nadu, India. Gender & Development, 16(1), 101–116.

Narayan, D. (Ed.). (2002). Empowerment and poverty reduction: A source book. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Nayyar, R. (1996). New initiatives for poverty alleviation in rural India. In C. H. Hanumantha Rao & H. Linneman (Eds.), Economic reforms and poverty alleviation in India (pp. 171–198). New Delhi: Sage.

Nicholls, A. (2006). Social entrepreneurship: New models of sustainable social change. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Patton, M. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Quinn, J. J., & Davies, P. W. F. (Eds.). (1999). Ethics and empowerment. London: Macmillan.

Rajgor, G. M. (2008). Women’s perceptions of land ownership: A case study from Kutch District, Gujurat, India. Gender & Development, 16(1), 41–54.

Rein, M., & Stott, L. (2009). Working together: Critical perspectives on six cross-sector partnerships in Southern Africa. Journal of Business Ethics, 90, 79–89.

Rindova, V., Barry, D., & Ketchen, D. J. (2009). Entrepreneuring as emancipation. Academy of Management Review, 34(30), 477–491.

Roomi, M. A., & Parrott, G. (2008). Barriers to development and progression of women entrepreneurs in Pakistan. Journal of Entrepreneurship, 17(1), 59–72.

Rose, K. (1992). Where women are leaders: The SEWA movement in India. London and New Jersey: Zed Books.

Rowlands, J. (1995). Empowerment examined. Development in Practice, 5(2), 101–107.

Scott, L., Dolan, C., Johnstone-Louis, M., Sugden, K., & Wu, M. (2012). Enterprise and inequality: A study of Avon in South Africa. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(3), 543–568.

Sen, A. (1993a). The economics of life and death. Scientific American, 268, 40–47.

Sen, A. (1993b). Does business ethics make economic sense? Business Ethics Quarterly, 3(1), 45–54.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Servon, L. J. (1997). Microenterprise programs in U. S. inner cities: Economic development or social welfare. Economic Development Quarterly, 11(2), 166–180.

Servon, L. J., & Doshna, J. P. (2000). Microenterprise and the economic development toolkit: A small part of the big picture. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 5(3), 183–208.

Shabbir, A., & Di Gregorio, S. (1996). An examination of the relationship between women’s personal goals and structural factors influencing their decision to start a business: The case of Pakistan. Journal of Business Venturing, 11(6), 507–529.

Shaheed, F. (1990). Pakistan’s women: An analytical description. Lahore: SANJH.

Silver, H. (1993). Homework and domestic work. Sociological Forum, 8(2), 181–204.

Steyaert, C. (2007). ‘Entrepreneuring’ as a conceptual attractor? A review of process theories in 20 years of entrepreneurship studies. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 19(6), 453–477.

Steyaert, C., & Hjorth, D. (Eds.). (2006). Entrepreneurship as social change. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. London: Sage.

Subramaniam, M. (2011). Grass roots and poor women’s empowerment in rural India. International Sociology, 27(1), 72–95.

Sud, M., VanSandt, C. V., & Baugous, A. M. (2009). Social entrepreneurship: The role of institutions. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(1), 201–216.

Thompson, P., Jones-Evans, D., & Kwong, C. (2009). Women and home-based entrepreneurship: Evidence from the United Kingdom. International Small Business Journal, 27(2), 227–237.

UNICEF. (2011). What’s going on? Girls’ education in India. Retrieved February 7, 2014, from www.un.org.

Wieringa, S. (1994). Women’s interests and empowerment: Gender planning reconsidered. Development and Change, 25(4), 829–849.

World Bank. (2005). New global poverty estimates: What it means for India. Retrieved February 7, 2014, from www.worldbank.org.

World Bank. (2011). World development report 2012: Gender equality and development. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Yin, R. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Yunus, M. (2003). Banker to the poor. The story of the Grameen bank. London: Aurum.

Yunus, M. (2008). A World without poverty: Social banking and the future of capitalism. New York, USA: Public Affairs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Haugh, H.M., Talwar, A. Linking Social Entrepreneurship and Social Change: The Mediating Role of Empowerment. J Bus Ethics 133, 643–658 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2449-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2449-4