Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the estrogen receptor coactivator amplified in breast cancer 1 (AIB1) as a prognostic marker, as well as a predictive marker for response to adjuvant tamoxifen and/or aromatase inhibitors, in early estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer.

Method

AIB1 was analyzed with immunohistochemistry in tissue microarrays of the Danish subcohort (N = 1396) of the International Breast Cancer Study Group’s trial BIG 1-98 (randomization between adjuvant tamoxifen versus letrozole versus the sequence of the two drugs).

Results

Forty-six percent of the tumors had a high AIB1 expression. In line with previous studies, AIB1 correlated to a more aggressive tumor-phenotype (HER2 amplification and a high malignancy grade). High AIB1 also correlated to higher estrogen receptor expression (80–100 vs. 1–79%), and ductal histological type. High AIB1 expression was associated with a poor disease-free survival (univariable: hazard ratio 1.35, 95% confidence interval 1.12–1.63. Multivariable: hazard ratio 1.29, 95% confidence interval 1.06–1.58) and overall survival (univariable: hazard ratio 1.34, 95% confidence interval 1.07–1.68. Multivariable: hazard ratio 1.25, 95% confidence interval 0.99–1.60). HER2 did not seem to modify the prognostic effect of AIB1. No difference in treatment effect between tamoxifen and letrozole in relation to AIB1 was found.

Conclusions

In a subset of the large international randomized trial BIG 1-98, we confirm AIB1 to be a strong prognostic factor in early breast cancer. Hence, although tumor AIB1 expression does not seem to be useful for the choice of tamoxifen versus an aromatase inhibitor in postmenopausal endocrine-responsive breast cancer, AIB1 is an interesting target for new anti-cancer therapies and further investigations of this biomarker is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One of the biggest challenges in today’s breast cancer care is to adjust adjuvant treatment, according to both tumor and patient characteristics, for optimal treatment aimed at improved prognosis. Although both tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors have been shown to improve survival in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer, the disease will recur in many patients despite adjuvant treatment (7–9% breast cancer recurrences five years after randomization in BIG-98 [1]). Moreover, in the metastatic setting most tumors eventually develop resistance to the given treatment. Hence, further studies of potential prognostic and predictive biomarkers are essential in order to optimize and individualize breast cancer treatment.

An interesting biomarker in relation to endocrine treatment is AIB1 (amplified in breast cancer 1). AIB1 belongs to the p160 steroid receptor coactivator family and interacts with the estrogen receptor in a ligand-dependent manner to enhance transcription [2, 3]. However, it has also been shown to interact with other transcription factors and signaling pathways inducing hormone-independent proliferation [4,5,6]. In human breast cancer, AIB1 correlates with factors indicating a more aggressive phenotype (HER2 amplification, DNA non-diploidy, a high tumor grade, a high S-phase fraction, and high Ki67) [5, 7,8,9,10]. Several studies have also indicated AIB1 to be associated with endocrine treatment effect [5, 7, 8, 11,12,13], although results have not been unanimous. We have previously shown AIB1 to be both a prognostic marker and a predictive marker for adjuvant tamoxifen in a randomized trial of premenopausal women receiving adjuvant tamoxifen for 2 years versus control, and in independent cohorts [9, 10, 14]. These data were extended also to postmenopausal patients in an independent randomized trial of adjuvant tamoxifen versus control [15]. Women with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer expressing high levels of AIB1 have a worse prognosis, but respond well to tamoxifen. The prognosis of women with low tumor expression of AIB1, on the other hand, is not further improved by tamoxifen, although early on they have a better prognosis. However, previous studies of AIB1 in relation to aromatase inhibitors are very sparse, and its predictive value for treatment with aromatase inhibitors has not been evaluated in any larger clinical trial. If patients with low tumor expression of AIB1 would still benefit from aromatase inhibitors, AIB1 might be a predictive marker for the choice between tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors, which is something we lack in the clinic today.

We use the Danish subcohort of the large randomized Breast International Group (BIG) 1-98 trial of adjuvant tamoxifen versus letrozole (as monotherapy or sequentially) with the aim to investigate AIB1 as a prognostic and predictive biomarker in relation to adjuvant endocrine treatment in estrogen receptor-positive postmenopausal breast cancer.

Patients and methods

BIG 1-98

The design of the BIG 1-98 trial, as well as the Danish cohort, has been described in detail before [16,17,18]. Briefly, this is a randomized, phase 3, double-blinded trial of postmenopausal, estrogen receptor-positive, early breast cancer. Patients were randomized to either monotherapy with tamoxifen or letrozole for 5 years, or to sequential therapy with 2 years of tamoxifen or letrozole followed by an additional 3 years with the other drug (letrozole/tamoxifen). The trial enrolled 1396 Danish patients from 1998 to 2003 included in the intention-to-treat population. Primary tumor samples were available for 1323 of patients and tissue microarrays were constructed for 1281 of these [18,19,20]. In 1997, the Danish Medicines Agency and the Danish National Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics approved the double-blinded BIG 1-98 trial, and the Ethical Committee of the Capital Region approved the current biomarker study before its activation (KF 02-178/97, KF 12-142/04, RH-2015-166; I-suite 04070). The BIG 1-98 trial is registered on the clinical trial site of the USA National Cancer Institute’s website (http:www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct/show/NCT00004205). The remark criteria were considered for presentation of data below [21].

Central assessment of the estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2

The International Breast Cancer Study Group’s Central Pathology Laboratory carried out a central review on whole tissue sections for estrogen and progesterone receptors by immunohistochemistry, and for HER2 by immunohistochemistry and fluorescent in situ hybridization as previously described [1, 22]. Tumors expressing estrogen or progesterone receptors in ≥1% of tumor cells were considered hormone receptor positive, and those with a HER2-to-Centromere-17 ratio ≥2 considered HER2-amplified. The pathology central review was carried out without knowledge of other characteristics, treatment assignment, or outcomes.

Immunohistochemistry for AIB1

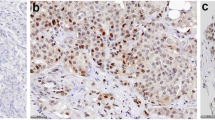

Tissue microarrays were constructed from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tumor blocks by a tissue microarray builder using 2-mm tissue cores [18]. Each tumor was represented by two cores. Immunohistochemistry for AIB1 was performed in an Autostainer-Plus, Dako. As a primary antibody for AIB1 detection, a mouse-monoclonal IgG antibody was used at 1:100 dilution (Cat no #611105 BD Bioscience, CA, USA), as previously described [7, 10]. This antibody has been used in several previous clinical trials [3, 7, 8], and its specificity has been confirmed by both Western blot and Northern blot, and in situ hybridization [3, 8]. Immunohistochemical staining (nuclear) was examined by two independent viewers blinded for clinical/tumor characteristics (Sara Alkner and Kristina Lövgren). Each sample was semi-quantitatively scored from 0 to 3 for percentage of stained nuclei and staining intensity. Proportion score 0 represented no stained nuclei, 1:1–10%, 2:11–50%, and 3:51–100%. Staining intensity 0 represented negative staining, 1 weak, 2 moderate, and 3 intense staining. Proportion and intensity scores were added to a total score ranging from 0 to 6. As in several previous publications from our group, a total score of ≥5 was used to define high AIB1 [7, 9, 10, 14]. Cases classified differently (high vs. low AIB1) between viewers (8%) were reexamined to reach consensus. In case of discrepant staining between the two cores from the same patient, the highest score was used.

Statistical analysis

All clinical data were collected and monitored by the International Breast Cancer Study Group and subsequently transferred to the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group, where the statistical analyses were conducted. Follow-up time was quantified in terms of a Kaplan–Meier estimate of potential follow-up. The primary end-point was disease-free survival, defined as the time from randomization to the first of the following events: recurrence at local, regional, or distant sites; a new invasive cancer in the contralateral breast; any second (non-breast) malignancy; or death without a prior cancer event. Secondary end-point was overall survival, defined as the time from randomization to death, irrespective of cause of death. Time-to-event outcomes were analyzed according to intention to treat. Follow-up was censored at last disease assessment, and in cross-over arms for predictive analysis at 2 years: time of scheduled cross-over.

Baseline characteristics were compared using two-sided Fisher’s exact tests or Wilcoxon rank sum test (age and tumor size). AIB1 expression (low/high) was compared via a stratified log-rank test of disease-free and overall survival, with randomization option (two-arm or four-arm) and treatment arm as a stratification factor, and Kaplan–Meier plots were generated. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals stratified by randomization option; multivariable models were adjusted for age at surgery, tumor size, tumor type and grade, estrogen receptor status, HER2 status, and nodal status. Assumptions of proportional hazard were tested using Schoenfeld residuals and by including a time-dependent component. The interactions of treatment by subpopulation of AIB1 were tested by Cox proportional hazards models including treatment groups, an indicator of the subpopulation, and the interaction term, and likewise for interaction of HER2 and the estrogen receptor by subpopulation of AIB1. Level of statistical significance was set to 5%. Statistical analyses were performed with the SAS v9.4 program package.

Results

AIB1 expression and correlation to other tumor markers

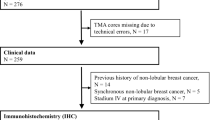

Tissue microarray cores from the primary tumor were available from 1281 (92%) of the 1396 Danish participants in the BIG 1-98 trial. Of these, 1244 (97%) were assessable for AIB1. All had estrogen receptor-positive (≥1%) tumors as confirmed by the central assessment. Estimated median potential follow-up was 9.0 years for all patients with full follow-up, and in cross-over arms 7.9 years. There were 440 disease-free survival events and 310 overall survival events. Patient flow and tumor characteristics are described in Fig. 1 and Table 1, respectively. Excluded patients had a higher frequency of small, node-negative tumors and had an earlier year of surgery. A high AIB1 expression was found in 46% of tumors, similar to results from previous studies [9, 10].

High AIB1 expression was associated with a higher tumor grade, HER2 amplification, high estrogen receptor expression (80–100% vs. 1–79%), a high Ki-67, and ductal histological type (Table 2).

AIB1 as a prognostic factor for disease-free and overall survival

High AIB1 expression was significantly associated with a worse disease-free and overall survival (Table 3; Fig. 2), although for overall survival, significance did not remain in the multivariable analysis. Kaplan–Meier estimates 10 years after randomization showed a disease-free survival of 64% (95% confidence interval 59–68%) for patients with a low AIB1 versus 56% (95% confidence interval 51–61%) for high AIB1. The corresponding numbers for overall survival were 74% (95% confidence interval 69–77%) versus 68% (95% confidence interval 64–73%). An exploratory analysis with a further subdivision of AIB1 into AIB1 score 6 versus score 5 versus score <5 indicated the prognostic effect of AIB1 to be strongest in patients with the highest AIB1 tumor expression (hazard ratio AIB1 score 5: disease-free survival 1.30, overall survival 1.25. Hazard ratio AIB1 score 6: disease-free survival 1.47, overall survival 1.54. AIB1 score <5 as reference. Disease-free survival P = 0.005, overall survival P = 0.02). All analyses were repeated including only HER2-normal and HER2-unknown cases with similar results (data not shown). No difference in association between AIB1 and disease-free/overall survival was seen in relation to HER2 status (disease-free survival P = 0.51, overall survival P = 0.60).

AIB1 as a predictive marker for treatment with tamoxifen versus letrozole

Patients with HER2-amplified tumors were excluded, since these patients would not currently be treated with endocrine therapy alone. Hazard ratios for the treatment effect of letrozole versus tamoxifen were as follows—for disease-free survival: AIB1 low 0.85 (95% confidence interval 0.61–1.18) and AIB1 high 1.08 (95% confidence interval 0.76–1.54), and for overall survival: AIB1 low 0.91 (95% confidence interval 0.60–1.37) and AIB1 high 0.91 (95% confidence interval 0.60–1.41). No treatment effect heterogeneity was found between the AIB1-high and AIB1-low populations (Table 4; Fig. 3). Hence, these data indicate a similar benefit of letrozole versus tamoxifen regardless of AIB1 status.

Discussion

We have investigated the estrogen receptor coactivator AIB1 as a prognostic and predictive factor in relation to endocrine treatment in the Danish cohort of BIG 1-98 (tamoxifen vs. letrozole). We found 46% of tumors to express high levels of AIB1, which is similar to previous publications [9, 10]. In line with earlier studies, AIB1 correlated to a more aggressive tumor phenotype (HER2 amplification and a high malignancy grade) [5, 7, 8, 23, 24]. In relation to estrogen and progesterone receptor status, results from previous studies have varied. Some show a high AIB1 to be associated with hormone receptor-positive disease [8, 25], while others report an association with estrogen and progesterone receptor negativity [5, 23, 26], or no correlation to receptor status at all [2, 7, 24]. Differences may possibly be explained by different study designs, cut-offs, and study populations. In this cohort, a high AIB1 was associated with a higher estrogen receptor expression.

AIB1 has been reported to be a negative prognostic factor, both in estrogen receptor-positive and estrogen receptor-negative breast cancers [9,10,11, 14, 24, 26,27,28,29]. As a result of studies that show an inferior prognosis for AIB1-high tumors in endocrine-treated estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cohorts [5, 7, 8], AIB1 has previously been suggested to be of importance for endocrine treatment resistance. However, our earlier investigations of a randomized premenopausal estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer trial (2 years adjuvant tamoxifen vs. control) clearly indicate that although AIB1-high tumors had an inferior prognosis early on, these patients responded very well to tamoxifen [10]. AIB1-low tumors had a better prognosis early on, but this was not further improved by tamoxifen. Importantly, these results have been confirmed in a randomized tamoxifen trial including postmenopausal estrogen receptor-positive disease [15]. Hence, we hypothesize that the association between a high AIB1 expression and poor prognosis is related to its prognostic significance, which cannot be entirely eradicated by adjuvant endocrine treatment. The strong prognostic effect of AIB1 makes it a very interesting target for new anti-cancer therapies. Although steroid receptor coactivators are large unstructured proteins making production of drugs against them challenging, there are ongoing efforts to pharmacologically target them [30, 31].

Today there are no markers that predict which population of postmenopausal estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer patients that are likely to have superior benefit from tamoxifen versus aromatase inhibitors. Due to AIB1’s predictive effect in relation to tamoxifen, we postulated that AIB1 status might be a useful marker. Previous trials regarding AIB1’s relation to aromatase inhibitors are very sparse, include small cohorts, and show conflicting results [12, 13]. The data presented here are, to our knowledge, the first time AIB1 is investigated in relation to aromatase inhibitors in a large randomized clinical trial. However, we found no evidence of differences in treatment effect between tamoxifen and letrozole in relation to AIB1 status. Hence, our study indicates that tumor expression of AIB1 cannot be applied as a predictive marker for selection of tamoxifen versus letrozole as adjuvant therapy in postmenopausal endocrine-responsive breast cancer.

A relationship between AIB1 and HER2 has previously been suggested, with a worse prognosis with co-expression of AIB1 and HER2 [5, 8, 32]. We found a correlation between a high AIB1 and HER2 amplification. However, in line with our previous studies, no significant interaction between AIB1 and HER2 in relation to prognosis was detected [9, 14]. As in all earlier studies though, AIB1-high, HER2-amplified tumors represented only a small subgroup of the cohort.

Although we had the advantage of using a large international controlled randomized trial, this study still has some potential limitations. Most importantly, the BIG 1-98 trial did not include a control group of patients not receiving endocrine therapy. Access to such a group would probably have clarified the prognostic and predictive value of AIB1 even more, especially in relation to letrozole. In addition, after an interim analysis showed a superior effect for letrozole, patients randomized to tamoxifen were allowed a treatment switch, reducing the possibility to detect differences in treatment effect [17]. Furthermore, although a large patient cohort is included, as in all studies, numbers are strongly reduced in subgroup analyses, such as investigations of AIB1-high/HER2-amplified tumors. Finally, although we used a cut-off to define a high AIB1, which has been used in several previous studies, AIB1 is still an explorative biomarker and an optimal cut-off is yet to be definitely determined.

In conclusion, in a subset of the BIG 1-98 study population, we confirm tumor expression of AIB1 to be a strong negative prognostic factor. As the association with a high AIB1 and poor prognosis has now been repeatedly shown in different patient cohorts, AIB1 is an interesting target for anti-cancer therapies. However, no difference in treatment effect between tamoxifen and letrozole in relation to AIB1 was found. Hence, AIB1 cannot be of assistance for the choice of type of endocrine treatment in postmenopausal endocrine-responsive disease.

References

Viale G, Regan MM, Maiorano E, Mastropasqua MG, Dell’Orto P, Rasmussen BB, Raffoul J, Neven P, Orosz Z, Braye S, Ohlschlegel C, Thurlimann B, Gelber RD, Castiglione-Gertsch M, Price KN, Goldhirsch A, Gusterson BA, Coates AS (2007) Prognostic and predictive value of centrally reviewed expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors in a randomized trial comparing letrozole and tamoxifen adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal early breast cancer: BIG 1-98. J Clin Oncol 25(25):3846–3852. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9453

Anzick SL, Kononen J, Walker RL, Azorsa DO, Tanner MM, Guan XY, Sauter G, Kallioniemi OP, Trent JM, Meltzer PS (1997) AIB1, a steroid receptor coactivator amplified in breast and ovarian cancer. Science 277(5328):965–968

List HJ, Reiter R, Singh B, Wellstein A, Riegel AT (2001) Expression of the nuclear coactivator AIB1 in normal and malignant breast tissue. Breast Cancer Res Treat 68(1):21–28

Torres-Arzayus MI, Font de Mora J, Yuan J, Vazquez F, Bronson R, Rue M, Sellers WR, Brown M (2004) High tumor incidence and activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway in transgenic mice define AIB1 as an oncogene. Cancer Cell 6(3):263–274

Osborne CK, Bardou V, Hopp TA, Chamness GC, Hilsenbeck SG, Fuqua SA, Wong J, Allred DC, Clark GM, Schiff R (2003) Role of the estrogen receptor coactivator AIB1 (SRC-3) and HER-2/neu in tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 95(5):353–361

Shou J, Massarweh S, Osborne CK, Wakeling AE, Ali S, Weiss H, Schiff R (2004) Mechanisms of tamoxifen resistance: increased estrogen receptor-HER2/neu cross-talk in ER/HER2-positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 96(12):926–935

Dihge L, Bendahl PO, Grabau D, Isola J, Lovgren K, Ryden L, Ferno M (2008) Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and the estrogen receptor modulator amplified in breast cancer (AIB1) for predicting clinical outcome after adjuvant tamoxifen in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 109(2):255–262

Kirkegaard T, McGlynn LM, Campbell FM, Muller S, Tovey SM, Dunne B, Nielsen KV, Cooke TG, Bartlett JM (2007) Amplified in breast cancer 1 in human epidermal growth factor receptor - positive tumors of tamoxifen-treated breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 13(5):1405–1411

Alkner S, Bendahl P, Grabau D, Malmstrom P, Ferno M, Ryden L, South Swedish Breast Cancer Group (2013) The role of AIB1 and PAX2 in primary breast cancer: validation of AIB1 as a negative prognostic factor. Ann Oncol 24(5):1244–1252. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds613

Alkner S, Bendahl PO, Grabau D, Lovgren K, Stal O, Ryden L, Ferno M, Swedish South-East Swedish, Breast Cancer G (2010) AIB1 is a predictive factor for tamoxifen response in premenopausal women. Ann Oncol 21(2):238–244. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdp293

Myers E, Hill AD, Kelly G, McDermott EW, O’Higgins NJ, Buggy Y, Young LS (2005) Associations and interactions between Ets-1 and Ets-2 and coregulatory proteins, SRC-1, AIB1, and NCoR in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 11(6):2111–2122

Yamashita H, Takahashi S, Ito Y, Yamashita T, Ando Y, Toyama T, Sugiura H, Yoshimoto N, Kobayashi S, Fujii Y, Iwase H (2009) Predictors of response to exemestane as primary endocrine therapy in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Cancer Sci 100(11):2028–2033. doi:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01274.x

O’Hara J, Vareslija D, McBryan J, Bane FT, Tibbitts PS, Byrne C, Conroy RM, Hao Y, Gaora PO, Hill A, McIlroy M, Young L (2012) AIB1:ERalpha transcriptional activity is selectively enhanced in AI-resistant breast cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3300

Alkner S, Bendahl PO, Ehinger A, Lovgren K, Ryden L, Ferno M (2016) Prior adjuvant tamoxifen treatment in breast cancer is linked to increased AIB1 and HER2 expression in metachronous contralateral breast cancer. PLoS ONE 11(3):e0150977. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150977

Weiner M, Skoog L, Fornander T, Nordenskjold B, Sgroi DC, Stal O (2013) Oestrogen receptor co-activator AIB1 is a marker of tamoxifen benefit in postmenopausal breast cancer. Ann Oncol 24(8):1994–1999. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdt159

Group BIGC, Mouridsen H, Giobbie-Hurder A, Goldhirsch A, Thurlimann B, Paridaens R, Smith I, Mauriac L, Forbes J, Price KN, Regan MM, Gelber RD, Coates AS (2009) Letrozole therapy alone or in sequence with tamoxifen in women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med 361(8):766–776. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810818

Giobbie-Hurder A, Price KN, Gelber RD, International Breast Cancer Study Group, Group BIGC (2009) Design, conduct, and analyses of Breast International Group (BIG) 1-98: a randomized, double-blind, phase-III study comparing letrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant endocrine therapy for postmenopausal women with receptor-positive, early breast cancer. Clin Trials 6(3):272–287. doi:10.1177/1740774509105380

Ejlertsen B, Aldridge J, Nielsen KV, Regan MM, Henriksen KL, Lykkesfeldt AE, Muller S, Gelber RD, Price KN, Rasmussen BB, Viale G, Mouridsen H, Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group, Group BIGC, International Breast Cancer Study Group (2012) Prognostic and predictive role of ESR1 status for postmenopausal patients with endocrine-responsive early breast cancer in the Danish cohort of the BIG 1-98 trial. Ann Oncol 23(5):1138–1144. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdr438

Larsen MS, Bjerre K, Giobbie-Hurder A, Laenkholm AV, Henriksen KL, Ejlertsen B, Lykkesfeldt AE, Rasmussen BB (2012) Prognostic value of Bcl-2 in two independent populations of estrogen receptor positive breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant endocrine therapy. Acta Oncol 51(6):781–789. doi:10.3109/0284186X.2011.653009

Henriksen KL, Rasmussen BB, Lykkesfeldt AE, Moller S, Ejlertsen B, Mouridsen HT (2007) Semi-quantitative scoring of potentially predictive markers for endocrine treatment of breast cancer: a comparison between whole sections and tissue microarrays. J Clin Pathol 60(4):397–404. doi:10.1136/jcp.2005.034447

McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM, Statistics Subcommittee of the NCIEWGoCD (2005) Reporting recommendations for tumour MARKer prognostic studies (REMARK). Br J Cancer 93(4):387–391. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602678

Rasmussen BB, Regan MM, Lykkesfeldt AE, Dell’Orto P, Del Curto B, Henriksen KL, Mastropasqua MG, Price KN, Mery E, Lacroix-Triki M, Braye S, Altermatt HJ, Gelber RD, Castiglione-Gertsch M, Goldhirsch A, Gusterson BA, Thurlimann B, Coates AS, Viale G, Collaborative BIG, International Breast Cancer Study Group (2008) Adjuvant letrozole versus tamoxifen according to centrally-assessed ERBB2 status for postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive early breast cancer: supplementary results from the BIG 1-98 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 9(1):23–28. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70386-8

Bouras T, Southey MC, Venter DJ (2001) Overexpression of the steroid receptor coactivator AIB1 in breast cancer correlates with the absence of estrogen and progesterone receptors and positivity for p53 and HER2/neu. Can Res 61(3):903–907

Bertelsen L, Bernstein L, Olsen JH, Mellemkjaer L, Haile RW, Lynch C, Malone K, Anton-Culver H, Christensen J, Langholz B, Thomas DC, Begg CB, Capanu M, Ejlertsen B, Stovall M, Boice JDJ, Shore RE, The Women´s Environment, Cancer and Radiation Epidemilogy Study Collaborative Group, Bernstein JL (2008) Effect of systemic adjuvant treatment on risk for contralateral breast cancer in the women´s environment, cancer and radiation epidemiology study. J Natl Cancer Inst 100(1):32–40

Iwase H, Omoto Y, Toyama T, Yamashita H, Hara Y, Sugiura H, Zhang Z (2003) Clinical significance of AIB1 expression in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 80(3):339–345

Spears M, Oesterreich S, Migliaccio I, Guiterrez C, Hilsenbeck S, Quintayo MA, Pedraza J, Munro AF, Thomas JS, Kerr GR, Jack WJ, Kunkler IH, Cameron DA, Chetty U, Bartlett JM (2012) The p160 ER co-regulators predict outcome in ER negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 131(2):463–472. doi:10.1007/s10549-011-1426-1

Harigopal M, Heymann J, Ghosh S, Anagnostou V, Camp RL, Rimm DL (2009) Estrogen receptor co-activator (AIB1) protein expression by automated quantitative analysis (AQUA) in a breast cancer tissue microarray and association with patient outcome. Breast Cancer Res Treat 115(1):77–85. doi:10.1007/s10549-008-0063-9

Zhao C, Yasui K, Lee CJ, Kurioka H, Hosokawa Y, Oka T, Inazawa J (2003) Elevated expression levels of NCOA3, TOP1, and TFAP2C in breast tumors as predictors of poor prognosis. Cancer 98(1):18–23. doi:10.1002/cncr.11482

Yamashita H, Nishio M, Toyama T, Sugiura H, Kondo N, Kobayashi S, Fujii Y, Iwase H (2008) Low phosphorylation of estrogen receptor alpha (ERalpha) serine 118 and high phosphorylation of ERalpha serine 167 improve survival in ER-positive breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 15(3):755–763. doi:10.1677/ERC-08-0078

Wang Y, Lonard DM, Yu Y, Chow DC, Palzkill TG, O’Malley BW (2011) Small molecule inhibition of the steroid receptor coactivators, SRC-3 and SRC-1. Mol Endocrinol 25(12):2041–2053. doi:10.1210/me.2011-1222

Song X, Chen J, Zhao M, Zhang C, Yu Y, Lonard DM, Chow DC, Palzkill T, Xu J, O’Malley BW, Wang J (2016) Development of potent small-molecule inhibitors to drug the undruggable steroid receptor coactivator-3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113(18):4970–4975. doi:10.1073/pnas.1604274113

Hurtado A, Holmes KA, Geistlinger TR, Hutcheson IR, Nicholson RI, Brown M, Jiang J, Howat WJ, Ali S, Carroll JS (2008) Regulation of ERBB2 by oestrogen receptor-PAX2 determines response to tamoxifen. Nature 456(7222):663–666. doi:10.1038/nature07483

Acknowledgements

We thank the International Breast Cancer Study Group for providing data on the Danish patients enrolled in the BIG 1-98 trial. We also thank the patients, nurses, data managers, and physicians who contributed to the BIG 1-98 clinical trial; and the Danish Cancer Cooperative Group for collaboration on this project. Finally, we thank Kristina Lövgren for immunohistochemical staining and scoring of AIB1, and Simon Hayes for proofreading.

Funding

This study was funded by the Swedish Breast Cancer Association (BRO) (2014); Skane County Council’s Research and Development Foundation (REGSKANE-434091); the Skane University Hospital foundation (2014-94413); the Swedish Cancer Society (15 0760); and the Anna and Edwin Bergers Foundation (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

In 1997, the Danish Medicines Agency and the Danish National Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics approved the double-blinded BIG 1-98 trial, and the Ethical Committee of the Capital Region approved the current biomarker study before its activation (KF 02-178/97, KF 12-142/04, RH-2015-166; I-suite 04070). All parts of this manuscript comply with the current Danish and Swedish laws. All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Alkner, S., Jensen, MB., Rasmussen, B.B. et al. Prognostic and predictive importance of the estrogen receptor coactivator AIB1 in a randomized trial comparing adjuvant letrozole and tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal breast cancer: the Danish cohort of BIG 1-98. Breast Cancer Res Treat 166, 481–490 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4416-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-017-4416-0