Abstract

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a debilitating psychiatric condition characterized by emotional dysregulation, unstable sense of self, and impulsive, potentially self-harming behavior. In order to provide new neurophysiological insights on BPD, we complemented resting-state EEG frequency spectrum analysis with EEG microstates (MS) analysis to capture the spatiotemporal dynamics of large-scale neural networks. High-density EEG was recorded at rest in 16 BPD patients and 16 age-matched neurotypical controls. The relative power spectrum and broadband MS spatiotemporal parameters were compared between groups and their inter-correlations were examined. Compared to controls, BPD patients showed similar global spectral power, but exploratory univariate analyses on single channels indicated reduced relative alpha power and enhanced relative delta power at parietal electrodes. In terms of EEG MS, BPD patients displayed similar MS topographies as controls, indicating comparable neural generators. However, the MS temporal dynamics were significantly altered in BPD patients, who demonstrated opposite prevalence of MS C (lower than controls) and MS E (higher than controls). Interestingly, MS C prevalence correlated positively with global alpha power and negatively with global delta power, while MS E did not correlate with any measures of spectral power. Taken together, these observations suggest that BPD patients exhibit a state of cortical hyperactivation, represented by decreased posterior alpha power, together with an elevated presence of MS E, consistent with symptoms of elevated arousal and/or vigilance. This is the first study to investigate resting-state MS patterns in BPD, with findings of elevated MS E and the suggestion of reduced posterior alpha power indicating a disorder-specific neurophysiological signature previously unreported in a psychiatric population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a mental disorder with a prevalence of around 1.6% in the general population (Kulacaoglu and Kose 2018). It is characterized by marked psychological dysregulation in several domains, including affect, sense of self, interpersonal relationships, as well as enhanced hostility, impulsivity and risk taking (Gunderson et al. 2018; Kulacaoglu and Kose 2018; Lieb et al. 2004). BPD patients often present with several comorbidities, and the disorder represents a severe personal and societal burden. One of the ways to gain a better understanding of its underlying pathophysiology is to identify brain biomarkers of the disorder. The characterization of specific neurophysiological patterns associated with BPD could potentially assist the diagnosis and guide therapeutic intervention. While numerous fMRI studies have focused on brain activation differences during domain-sensitive tasks (Krause-Utz et al. 2014 for review), recent studies have started to examine brain activity during rest, by analyzing spontaneous neural activity and functional connectivity (Visintin et al. 2016 for review). In this context, fMRI signals have a relatively low temporal resolution of several seconds, and spontaneous brain networks can be better explored on sub-second temporal scales with EEG (Varela et al. 2001 for review). Recent EEG studies in BPD have reported increased prevalence of intermittent delta and theta oscillatory activities which are supportive of medical care consisting of anticonvulsive treatment (Tebartz van Elst et al., 2016). On the contrary, frontal alpha asymmetry, a functional biomarker of emotion and motivation processing (Smith et al. 2017), was not significantly different in BPD compared to controls, but the scores of alexithymia were negatively associated with right-frontal alpha activity (Flasbeck et al. 2017). There is some debate concerning brain arousal in BPD patients, where its dysregulation has been associated with higher levels of emotional instability (Hegerl and Hensch 2014). While lowered-EEG vigilance was initially reported (Hegerl et al. 2008), more recent evidence based on a computer-based scoring algorithm (VIGALL2.0, Sander et al. 2015) suggests elevated resting-state EEG vigilance in BPD patients (Kramer et al. 2019).

In addition to spectral power measures, the spatio-temporal dynamics of large-scale neural networks can be captured using EEG microstate analysis (Michel and Koenig 2018; Pascual-Marqui et al. 1995; Van de Ville et al. 2010). Frequently applied to spontaneous (i.e. resting-state) EEG, this analysis models the sequential occurrence of transient topographical patterns of electrical activity that are referred as “microstates” (MS). While historical analyses described 4 canonical MS topographies dominating resting-state activity (A, B, C, D, Britz et al. 2010; Michel and Koenig 2018), recent work has identified up to 7 main MS patterns within resting EEG (A, B, C, D, E, F, G, Brechet et al. 2019; Custo et al. 2017; Damborska et al. 2019b). A growing body of research indicates significant MS alterations in a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia and depression (Khanna et al. 2015 for review). Our own group recently reported on abnormalities in EEG MS dynamics in adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), finding a positive association between microstate D duration and sleep disturbance (Ferat et al. 2021). In the current study, we applied resting-state MS analysis for the first time in patients with BPD, in the hope of providing new neurophysiological insights of this disorder and/or identifying potential targets for future treatments. Our objective was to examine both the EEG spectral power and microstate dynamics in parallel, in order to evaluate their respective contribution in characterizing the electrophysiological signature(s) of BPD. Using high-density EEG recordings (comprising 256 EEG-channels), we tested for statistical differences in spectral power and traditional MS measures between BPD patients (n = 16) and age-matched healthy controls (CTL, n = 16). Consequently, we examined the correlations between the most salient metrics derived from group-analyses with both approaches, as they may provide complementary information on the clinical aspects of the disorder.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Clinical Assessment

The present study analyzed a subgroup of participants enrolled in a larger neuroimaging study (Berchio et al. 2017; Murray et al. 2022). Sixteen BPD patients (15 female, mean age: 25.1 ± 5.6) diagnosed with BPD were recruited in a specialized unit of the Department of Psychiatry of the University Hospitals of Geneva. The majority of women in our sample reflects the worldwide overrepresentation of women diagnosed with BPD in specialized units (Sansone and Sansone 2011; Skodol and Bender 2003). A group of 16 age-matched healthy controls (10 female, mean age: 29.6 ± 13.5) were recruited in parallel through announcements in the population. There was no significant difference in gender between the two experimental groups (Table 1). Each participant filled their informed consent prior to the study, which was approved by the Research Ethic Committee of the Republic and Canton of Geneva (CER 13–081).

BPD diagnosis was assessed by the French version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders BPD part (BPD severity index: M: 7.4, SD = 1.84). Depression was evaluated using the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS, Montgomery and Åsberg 1979). In addition, participants completed several self-report questionnaires: the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI, Spielberger 2010), the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI, Spielberger et al. 1983), the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ, Jermann et al. 2006), the Affective Lability Scale (ALS, Harvey et al. 1989), the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS, Treynor et al. 2004), the Impulsive Behavior Scale (UPPS, Whiteside et al. 2005), and the Adult Self-Report Scale for ADHD (ASRS, Kessler et al. 2005). We computed sub-scores where relevant: adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies with the CERQ, rumination and reflection with the RRS, and 4 subscales of the UPPS. The groups differed in: anger and anxiety scores, cognitive non adaptative regulation, affective lability, rumination (except for reflection), impulsive behavior (except sensation seeking), inattention and impulsivity as assessed using ASRS (Table 1). Affective disorders, schizophrenia, and other comorbid conditions in BPD and CTL were assessed using the French version of the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS) (Preisig et al. 1999). In BPD patients, current comorbidities included: eating disorders (n = 1), post-traumatic stress disorder (n = 6), anxiety disorder (n = 3), attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder (n = 2), and substance abuse (n = 5). Comorbidity information was missing for 3 patients. One patient was receiving psychotropic medication (quetiapine). Healthy control subjects had no history of psychiatric illness as assessed with the DIGS, and had no taken medication or substance by their own report.

EEG Acquisition

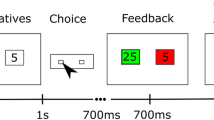

EEG data were acquired with a 256-channel Electrical Geodesic Inc. system (Eugene, OR), with a sampling rate of 1000 Hz, and Cz as reference electrode. Electrode impedances were kept below 30 kOhms. Three minutes of resting-state with eyes closed were acquired at the beginning of an experimental procedure on face and gaze processing (Berchio et al. 2017).

EEG Analysis

Pre-processing

Data were processed in MATLAB version 2021a with EEGLAB version 14 (The MathWorks, Inc.) (Delorme and Makeig 2004). Offline EEG data was firstly down-sampled to 250 Hz. Then, the following sequence of steps were performed in order to remove artifactual (i.e. non-cerebral) sources of electrical activity that may contaminate EEG recordings (Bailey et al. 2022). Firstly, EEG data was band-pass filtered at 1–80 Hz. Next, the Zapline method was used to remove the top 6 components around the 50 Hz main line frequency (de Cheveigne 2020). Then, we removed bad channels using EEGLAB’s PREP plugin (Bigdely-Shamlo et al. 2015) with default settings and spherically interpolated the rejected channels. After which, Infomax ICA was performed using the runica() function. We then rejected specific ICA components related to (i) eye blinks/movements using the EyeCatch algorithm default settings (Bigdely-Shamlo et al. 2013), and (ii) muscle artifacts flagged by ICLabel at > 50% probability (Pion-Tonachini et al. 2019). We then automatically removed additional low-frequency artifacts using wavelet ICA at threshold = 10 and wavelet level = 10 (Castellanos and Makarov 2006). Finally, remaining EEG artifacts were removed epoch-wise with a z-score based method using the FASTER plug-in (Nolan et al. 2010), rejecting 1-second epochs deviating by more than two standard deviations. Cleaned EEG data were visually inspected before and after automatic processing to verify the quality of deartifacting performed. All subjects’ clean EEG data exceeded 120 s. After deartifacting, the data were bandpass filtered between 1 and 30 Hz and re-referenced to a common average reference.

Power Spectrum Analysis

Absolute power spectral density was computed for frequencies ranging from 1 to 30 Hz using the Welch method, with a 2 s window effective size and no overlap. To obtain a relative metric usable for between-subject comparisons, all values were divided by the sum of the full spectrum (1–30 Hz). For further analysis, the obtained values were then added up within each studied frequency band: delta (2–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), and beta (13–30 Hz).

Microstate Analysis

Estimation of Microstate Maps

The pipeline for estimating the MS topographies has been described elsewhere (Ferat et al. 2021). MS topographies were estimated separately for the BPD and control groups using Thomas Koenig’s Microstate toolbox v1 for EEGLAB. For each subject’s resting-state recording, 2000 global field power peaks were randomly selected and subjected to modified k-means clustering (polarity-independent) with 100 repetitions. MS maps (i.e., cluster centroids) were estimated for cluster numbers from k = 4 to k = 7, first at the subject level and then optimally reordered between subjects by minimizing the average spatial correlation across maps. Finally, the respective MS maps were averaged across all subjects within each group to obtain the aggregate map for each cluster. Based on the mean spatial correlation of each subject’s map with the group’s aggregate, we found that k = 5 provided the highest map reliability across subjects.

Backfitting

Thomas Koenig’s Microstate toolbox v1 for EEGLAB was used to backfit on the whole data the k = 5 global dominant topographies back to the original EEGs. The time points were assigned to cluster labels, or MS topographies, based on their highest absolute spatial correlation. Time points with a spatial correlation below the correlation threshold of r = 0.5 were labeled as non-assigned. To ensure temporal continuity, a smoothing window of seven samples (56.0 ms) was applied, and label sequences that did not reach a duration of 3 samples (24.0 ms) were split into two parts and relabeled based on the highest spatial correlation with their neighboring segment. Non-assigned time points being removed, none of the participants had z ≥ 3 for unlabeled time points and they were all included in further analysis. A label sequence was derived for each individual recording, and three spatiotemporal metrics were computed: occurrence (counts/second), mean duration (milliseconds), and time coverage (%), representing the number of times a microstate class recurred per second, the mean temporal duration without interruption, and the proportion of time during which a label was present in the recording, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

EEG Spectral Power

Statistical analysis of EEG spectral power was carried out at the electrode level in the four frequency bands (as defined above: delta, theta, alpha, beta) using the Neurophysiological Biomarker Toolbox version 1 (NBT, http://www.nbtwiki.net/) in Matlab version 2021a (MathWorks Inc.). In absence of pre-established hypothesis, the two-sided test was used. P-values were estimated by simulated random sampling with 5000 replications. For univariate analyses at the single-channel level, no correction was applied for multiple comparisons, such that results remained exploratory in nature.

Microstate Measures

Group comparisons were conducted on the three MS spatiotemporal metrics using unpaired permutation test for equality of means (Ferat et al. 2021). In absence of pre-established hypothesis, the two-sided test was used. P-values were estimated by simulated random sampling with 5000 replications. Statistical results were corrected for multiple comparisons using False Discovery Rate (FDR), as proposed by Benjamini-Hochberg (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). The significance threshold for all comparisons was set to alpha = 0.05. Cohen’s d (d) was used to report effect sizes as standardized difference of means.

Correlation Analyses

We additionally conducted exploratory Spearman correlation analyses (Spearman’s Rho) between spectral power and MS spatiotemporal metrics on the pooled BPD and control datasets in order to evaluate if these two categories of EEG features may target similar or distinct aspects of the disorder (Gordillo et al. 2023).

Furthermore, we explored the potential correlations of the affective lability score (ALS) with MS C and E measures from the pooled BPD and control group data (Spearman’s Rho). We selected the ALS as it is a specific hallmark of emotional dysregulation in BPD (Koenigsberg et al. 2002) validated in the French language and commonly used for case control clinical studies (Marwaha et al. 2018).

Results

Spectral Power Analysis

The EEG relative power spectrum is displayed in Fig. 1, showing reduced amplitude in the 8–12 Hz alpha frequency band and elevated amplitude in the 2–4 Hz delta frequency band in BPD compared to CTL.

Here, no significant differences were detected between groups in global relative power (i.e. average of all channels) in any frequency bands. As shown in Fig. 2, univariate analyses on the single-channel level (p < 0.05 uncorrected) revealed significantly increased delta power (cluster maximum at O2 electrode: d = 0.93, p < 0.05 uncorrected) and decreased alpha power (cluster minimum at POz electrode: d = − 0.82, p < 0.05 uncorrected) in the posterior-midline region in BPD as compared to CTL (Fig. 2).

MS Topographies

As shown in Fig. 3A, BPD and CTL groups both exhibited the 5 canonical MS topographies A, B, C, D, E (Michel and Koenig 2018), i.e., group maps with a right-left diagonal orientation (A), a left-right diagonal orientation (B), an antero-posterior orientation (C), a fronto-central maximum (D), and a parieto-central maximum (E). Spatial correlation analysis showed minor differences of MS maps between groups (minimum absolute correlation ≥ 0.86) (Fig. 3B). As the results from a k-means clustering on concatenated BPD and CTL data did not produce different MS topographies, we used the vector average between group maps for back-fitting and individual estimation of MS dynamics.

MS Segmentation

Figure 4 shows the plots of the three MS spatiotemporal measures across groups. In the BPD compared to CTL group, MS C showed reduced occurrence (d = − 0.89, p = 0.010 FDR corrected), time coverage (d = − 0.91, p = 0.017 FDR corrected) and mean duration (d = − 0.90, p = 0.013 FDR corrected). An opposite effect was observed for MS E, which showed increased occurrence (d = 1.08, p = 0.003 FDR corrected) and time coverage (d = 1.02, p = 0.007 FDR corrected) in BPD compared to CTL.

Exploratory Correlations Between Microstate Parameters and Spectral Power

Here we explored the potential relationship between spectral power and the MS temporal measures that differed between the BPD and CTL groups (cf. Sect. MS segmentation). Pooling all participants, an exploratory correlation analysis (Spearman’s Rho) was performed between global relative alpha or delta power and MS C occurrence, time coverage, and mean duration, as well as MS E occurrence and time coverage. We found that global relative alpha power was positively correlated with MS C occurrence (Rho = 0.610, p < 0.001), time coverage (Rho = 0.770, p < 0.001), and mean duration (Rho = 0.804, p < 0.001). Global relative delta power was negatively correlated with MS C occurrence (Rho = − 0.546, p < 0.001), time coverage (Rho = − 0.699, p < 0.001), and mean duration (Rho = − 0.739, p < 0.001). Interestingly, no significant correlations were found for MS E measures. Figure 5 illustrates the correlations between MS C and E time coverage and global relative alpha and delta power.

Exploratory Correlations Between Microstate Parameters and Clinical Score of Affective Lability

Pooling all participants, the exploratory correlation analysis (Spearman’s Rho) was performed between the ALS and the MS temporal measures that differed between the BPD and CTL groups (cf. Sect. MS segmentation). The ALS was negatively correlated with MS C occurrence (Rho = − 0.551, p < 0.01), time coverage (Rho = − 0.625, p < 0.001), and mean duration (Rho = − 0.606, p < 0.001). It was positively correlated with MS E occurrence (Rho = 0.528, p < 0.01) and time coverage (Rho = 0.469, p < 0.05). These correlations are illustrated in Fig. 6.

Discussion

In the present study we examined two neurophysiological aspects of the resting-state EEG in BPD. Firstly, although the global relative spectral power of BPD does not differ from neurotypical subjects, exploratory univariate analyses on single channels indicated greater relative delta and lower relative alpha power in posterior regions. Secondly, we demonstrate that BPD patients share spatially equivalent MS topographies compared to neurotypical subjects—implying similar anatomical generators of EEG activity—but that their temporal dynamics are significantly altered. Compared to controls, BPD patients showed significantly reduced prevalence of MS C (for time coverage, occurrence and mean duration), together with increased prevalence of MS E (for time coverage and occurrence). Interestingly, exploratory correlation analyses revealed that increased prevalence of MS C correlated positively with global relative alpha and negatively with global relative delta power, while MS E alterations were uncoupled to changes in narrow-band spectral power.

Power Spectrum

The global spectral power was not significantly different between the two groups in any frequency bands, indicating that global EEG power does not carry a representative hallmark of BPD. Furthermore, we did not detect alpha power asymmetry in the frontal regions, which has been suggested to be related to both motivation and emotion constructs and discussed as a potential marker of pathophysiology in BPD (Flasbeck et al. 2017). These negative findings could be the result of the limited sample size of our cohort, and therefore are to be interpreted with caution. In contrast, when running exploratory analyses on single EEG channels, we observed a reduction of posterior-midline alpha power in BPD as compared to controls. Although interpretation is limited by the risk of false positive results (i.e. absence of correction for multiple comparisons), the reduced parietal alpha power in BPD patients may suggest a state of increased cortical excitability (Mathewson et al. 2011; Romei et al. 2008), which has previously been associated with behavioral hyperarousal and/or anxiety (Barry et al. 2007; Dadashi et al. 2015). Modulation of excitability within the parietal or visual cortex is largely determined by posterior alpha activity, which mainly originates from thalamo-cortical inputs (Lorincz et al. 2008). Since the alpha band is a dominant frequency band in the generation of the MS C topography (Ferat et al. 2022), this could explain the positive relationship between MS C parameters and alpha relative power (Krylova et al. 2021; Milz et al. 2016). Conversely, the results in the delta band showed enhanced posterior-midline power in BPD. Being inversely correlated with alpha power (Newson and Thiagarajan 2019), the delta power increase also correlated negatively with MS C parameters. Overall, the lack of statistical power does not allow a firm conclusion to be made on the spectral power results, and further studies including a larger sample size will be necessary to confirm these exploratory observations.

Microstate C

In a previous study using EEG source localization (Custo et al. 2017), MS C has been reported to be generated by the precuneus, the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), and the left angular gyrus, all areas implicated in the default-mode network (DMN). Elsewhere, MS C presence has been associated with increases in interoceptive and self-focused thoughts (Brechet et al. 2019) and decreases in mental arithmetic tasks (Kim et al. 2021; Seitzman et al. 2017), which are also related to the activity of the “task-negative” DMN (Brechet et al. 2019; Custo et al. 2017; Michel and Koenig 2018). Hence, the reduced MS C prevalence in BPD patients suggests a reduction of task-negative brain states associated with self-processing, compatible with decreased alpha power (Chavan et al. 2013) and increased behavioral alertness (Kramer et al. 2019). Regarding other psychiatric conditions, contribution of MS C has been reported significantly reduced in eyes-closed resting EEG of adolescent ADHD (Luo et al. 2022), and unchanged in eyes-opened resting EEG of adult ADHD (Ferat et al. 2021), as compared to age-matched controls. Mirroring our findings in patients with BPD, a reduction of MS C occurrence has also been observed in a group of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) who did not achieve remission after 8 weeks of SSRI treatment, compared to patients that achieved remission (Lei et al. 2022). Furthermore, the reduced presence of MS C was associated with poor therapeutic outcomes after treatment (Lei et al. 2022). Elsewhere, reduced MS C was also observed in mood and anxiety disorder, although this did not reach statistical significance (Al Zoubi et al. 2019).

Microstate E

The 4 canonical classes A, B, C, D were recently complemented by the identification of 2 to 3 additional topographies, among them MS E (sometimes referred to as MS F) characterized by a topography with a posterior maximum. The anatomical generators of MS E have been related to the dorsal anterior cingulate, superior/middle frontal gyri, and insula (Brechet et al. 2019; Custo et al. 2017; Damborska et al. 2019b), which are part of the cingulo-opercular or “salience” network (CON). Damborska and colleagues (Damborska et al. 2019b) have reported on a positive correlation of MS E occurrence with intake of antidepressants, antipsychotics and mood stabilizers. They discussed a putative link between MS E and the “task-positive” CON, which plays a central role in sustaining alertness/perceptual readiness (Coste and Kleinschmidt 2016; Sadaghiani and D’Esposito 2015), and whose disrupted connectivity was observed in depression (Wu et al. 2016). A complementary view relates the CON with the integration of autonomic processes, by which it is engaged in assessing the salience of internal and external stimuli (Seeley 2019; Seeley et al. 2007). Increased prevalence of MS E in BPD patients is thus compatible with both a higher sustained alertness and an exacerbated response of the CON in relation with salience processing (Sadaghiani and D’Esposito 2015). Moreover, the CON partly overlaps with the fronto-limbic emotion regulation network, whose impairment might mediate emotional dysregulation in BPD (Krause-Utz et al. 2014; O’Neill and Frodl 2012). Recent findings from our own group have identified a positive link between BOLD signal variability in the fronto-limbic network and the severity of emotional dysregulation in BPD (Kebets et al. 2021), that could explain the association between the observed abnormalities in MS E and emotional instability in BPD. In contradistinction to our results in BPD patients, reduced presence of MS E has been found in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Terpou et al. 2022) as well as in MDD, where it also negatively correlated with depression inventory scores (Qin et al. 2022). Hence increased prevalence of MS E may correspond to a unique neuromarker of BPD, that is independent from microstate signatures of patients with PTSD or MDD.

Association of MS C and E with Emotional Instability

We further explored the potential associations between EEG microstate abnormalities and the ALS, a widely employed index of emotional dysregulation severity in BPD. To overcome the issue of small sample size in our BPD group, we opted for pooling the two groups for these analyses. The interpretation of the results is complicated by the possibility that the data derive from separate distributions (Simpson’s paradox, Simpson 1951). However, if one assumes the pooled data come from the same sampling distribution (i.e. patients are on the same continuum as controls), then these correlations underline a potentially significant relationship between emotional dysregulation and microstate measures. MS C and MS E showed opposite behavior in their relationship with ALS, consistent with their abnormality in BPD. MS C, significantly reduced in BPD, was negatively correlated with ALS, while MS E, significantly increased in BPD, was positively correlated with ALS. These observations suggest the relevance of the MS C and E measures as potential neuromarkers of emotional instability in BPD. Further investigations are needed to establish a possible mediating link between these spatiotemporal indices of brain activity and emotional impairment in BPD.

What EEG Resting-State Analyses Tell Us About BPD Neurophysiology

The results based on microstates are more statistically significant and conclusive than those based on spectral power, suggesting a greater sensitivity of EEG spatiotemporal measures in BPD. The finding of significant exploratory correlations between one microstate class (i.e. MS C) and alpha power on the one hand, and delta on the other, indicates that both of these measures may be associated with an overlapping aspect of the disorder. However, as this was not the case for microstate E, the latter could represent a valuable, additional neuromarker of the disorder, referring more particularly to emotional instability. The reduced posterior-midline alpha power in BPD patients compared to neurotypical subjects suggests increased cortical hyperexcitability in this disorder. This finding is in line with recent EEG evidence that BPD patients at rest demonstrate higher stages of vigilance compared to controls (Kramer et al. 2019). This could potentially be also linked to elevated noradrenergic activity in the locus coeruleus reported in BPD (Kramer et al. 2019), in turn responsible for various effects associated with stress, including elevated arousal and deficiencies in attentional and cognitive functions (Berridge and Spencer 2017). Further analyses on larger samples of patients would be necessary to confirm the link between microstate E and clinical scores, in particular emotional lability.

Limitations

The present study has some limitations. First, the sample size of each group is quite small, limiting statistical power. Second, the patient sample was almost all female, which could potentially be a source of bias. Even if in epidemiological studies the gender ratio between male and female is near to 1, usually in clinical settings and thus in research coming from these facilities more than 75% of people diagnosed with BPD are women (Sansone and Sansone 2011; Skodol and Bender 2003). The reasons for this significant overrepresentation of women are still unknown; there may be biological, psychosocial, cultural and psychological factors that predispose women with BPD to more often seek psychological/psychiatric help. Our own data simply reflect this worldwide overrepresentation of women in specialized units. Although comprising more male subjects, the gender of our age-matched control group did not differ significantly from the patient group.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, the current study is the first to analyze the resting-state dynamics of EEG microstates in patients with BPD, where we observed a reduced prevalence of MS C and an increased prevalence of MS E. These findings, together with the exploratory observations of reduced (enhanced) power in the alpha (delta) bands, are compatible with a signature of cortical hyperactivation in BPD patients, associated with a state of elevated cortical arousal and/or behavioral vigilance. Although the present findings need replication in larger samples, the application of MS analysis appears to offer more specific neuromarker(s) of BPD pathophysiology and diagnosis, when compared to classical analyses using spectral power. This approach could also hold promise for developing future neuromarker-based treatments (e.g. EEG neurofeedback).

6. References

Al Zoubi O, Mayeli A, Tsuchiyagaito A, Misaki M, Zotev V, Refai H et al (2019) EEG microstates temporal dynamics differentiate individuals with mood and anxiety disorders from healthy subjects. Front Hum Neurosci 13:56. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2019.00056

Bailey NW, Biabani M, Hill AT, Miljevic A, Rogasch NC, McQueen B, Murphy OW, Fitzgerald PB (2022) Introducing RELAX (the reduction of electroencephalographic artifacts): A fully automated pre-processing pipeline for cleaning EEG data - Part 1: algorithm and application to oscillations. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.08.483548

Barry RJ, Clarke AR, Johnstone SJ, Magee CA, Rushby JA (2007) EEG differences between eyes-closed and eyes-open resting conditions. Clin Neurophysiol 118:2765–2773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2007.07.028

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol 57:289–300

Berchio C, Piguet C, Gentsch K, Kung AL, Rihs TA, Hasler R et al (2017) Face and gaze perception in borderline personality disorder: an electrical neuroimaging study. Psychiatr Res Neuroimaging 269:62–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2017.08.011

Berridge CW, Spencer RC (2017) Noradrenergic control of arousal and stress. In: Fink G (ed) Stress: neuroendocrinology and neurobiology. Elsevier Academic Press, pp 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-802175-0.00004-8

Bigdely-Shamlo N, Kreutz-Delgado K, Kothe C, Makeig S (2013) EyeCatch: data-mining over half a million EEG independent components to construct a fully-automated eye-component detector. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2013:5845–5848. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC.2013.6610881

Bigdely-Shamlo N, Mullen T, Kothe C, Su KM, Robbins KA (2015) The PREP pipeline: standardized preprocessing for large-scale EEG analysis. Front Neuroinform 9:16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fninf.2015.00016

Brechet L, Brunet D, Birot G, Gruetter R, Michel CM, Jorge J (2019) Capturing the spatiotemporal dynamics of self-generated, task-initiated thoughts with EEG and fMRI. NeuroImage 194:82–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.03.029

Britz J, Van De Ville D, Michel CM (2010) BOLD correlates of EEG topography reveal rapid resting-state network dynamics. NeuroImage 52:1162–1170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.052

Castellanos NP, Makarov VA (2006) Recovering EEG brain signals: artifact suppression with wavelet enhanced independent component analysis. J Neurosci Methods 158:300–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.05.033

Chavan CF, Manuel AL, Mouthon M, Spierer L (2013) Spontaneous pre-stimulus fluctuations in the activity of right fronto-parietal areas influence inhibitory control performance. Front Hum Neurosci 7:238. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00238

Coste CP, Kleinschmidt A (2016) Cingulo-opercular network activity maintains alertness. NeuroImage 128:264–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.01.026

Custo A, Van De Ville D, Wells WM, Tomescu MI, Brunet D, Michel CM (2017) Electroencephalographic resting-state networks: source localization of Microstates. Brain Connect 7:671–682. https://doi.org/10.1089/brain.2016.0476

Dadashi M, Birashk B, Taremian F, Asgarnejad AA, Momtazi S (2015) Effects of increase in amplitude of occipital alpha & theta brain waves on global functioning level of patients with GAD. Basic Clin Neurosci 6:14–20

Damborska A, Tomescu MI, Honzirkova E, Bartecek R, Horinkova J, Fedorova S, Ondrus S, Michel CM (2019b) EEG resting-state large-scale brain network dynamics are related to depressive symptoms. Front Psychiatr 10:548. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00548

de Cheveigne A (2020) ZapLine: a simple and effective method to remove power line artifacts. NeuroImage 207:116356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116356

Delorme A, Makeig S (2004) EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J Neurosci Methods 134:9–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.10.009

Ferat V, Arns M, Deiber MP, Hasler R, Perroud N, Michel CM, Ros T (2021) EEG microstates as novel functional biomarkers for adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatr Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2021.11.006

Ferat V, Seeber M, Michel CM, Ros T (2022) Beyond broadband: towards a spectral decomposition of electroencephalography microstates. Hum Brain Mapp 43:3047–3061. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.25834

Flasbeck V, Popkirov S, Brune M (2017) Frontal EEG asymmetry in borderline personality disorder is associated with alexithymia. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul 4:20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-017-0071-7

Gordillo D, da Cruz JR, Chkonia E, Lin WH, Favrod O, Brand A et al (2023) The EEG multiverse of schizophrenia. Cereb Cortex 33:3816–3826. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhac309

Gunderson JG, Herpertz SC, Skodol AE, Torgersen S, Zanarini MC (2018) Borderline personality disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers 4:18029. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2018.29

Harvey PD, Greenberg BR, Serper MR (1989) The affective lability scales: development, reliability, and validity. J Clin Psychol 45:786–793.

Hegerl U, Hensch T (2014) The vigilance regulation model of affective disorders and ADHD. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 44:45–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.10.008

Hegerl U, Stein M, Mulert C, Mergl R, Olbrich S, Dichgans E, Rujescu D, Pogarell O (2008) EEG-vigilance differences between patients with borderline personality disorder, patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and healthy controls. Eur Arch Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 258:137–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-007-0765-8

Jermann F, Van der Linden M, d’Acremont M, Zermatten A (2006) Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire (CERQ). Eur J Psychol Assess 22:126–131. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.22.2.126

Kebets V, Favre P, Houenou J, Polosan M, Perroud N, Aubry JM, Van De Ville D, Piguet C (2021) Fronto-limbic neural variability as a transdiagnostic correlate of emotion dysregulation. Transl Psychiatr 11:545. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01666-3

Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, Demler O, Faraone S, Hiripi E et al (2005) The World Health Organization adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med 35:245–256

Khanna A, Pascual-Leone A, Michel CM, Farzan F (2015) Microstates in resting-state EEG: current status and future directions. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 49:105–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.12.010

Kim K, Duc NT, Choi M, Lee B (2021) EEG microstate features according to performance on a mental arithmetic task. Sci Rep 11:343. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-79423-7

Koenigsberg HW, Harvey PD, Mitropoulou V, Schmeidler J, New AS, Goodman M et al (2002) Characterizing affective instability in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatr 159:784–788. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.784

Kramer L, Sander C, Bertsch K, Gescher DM, Cackowski S, Hegerl U, Herpertz SC (2019) EEG-vigilance regulation in Borderline personality disorder. Int J Psychophysiol 139:10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2019.02.007

Krause-Utz A, Winter D, Niedtfeld I, Schmahl C (2014) The latest neuroimaging findings in borderline personality disorder. Curr Psychiatr Rep 16:438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-014-0438-z

Krylova M, Alizadeh S, Izyurov I, Teckentrup V, Chang C, van der Meer J et al (2021) Evidence for modulation of EEG microstate sequence by vigilance level. NeuroImage 224:117393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117393

Kulacaoglu F, Kose S (2018) Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD): in the midst of vulnerability, chaos, and awe. Brain Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8110201

Lei L, Liu Z, Zhang Y, Guo M, Liu P, Hu X et al (2022) EEG microstates as markers of major depressive disorder and predictors of response to SSRIs therapy. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatr. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2022.110514

Lieb K, Zanarini MC, Schmahl C, Linehan MM, Bohus M (2004) Borderline personality disorder. The Lancet 364:453–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(04)16770-6

Lorincz ML, Crunelli V, Hughes SW (2008) Cellular dynamics of cholinergically induced alpha (8–13 hz) rhythms in sensory thalamic nuclei in vitro. J Neurosci 28:660–671. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4468-07.2008

Luo N, Luo X, Zheng S, Yao D, Zhao M, Cui Y et al (2022) Aberrant brain dynamics and spectral power in children with ADHD and its subtypes. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatr. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-02068-6

Marwaha S, Price C, Scott J, Weich S, Cairns A, Dale J, Winsper C, Broome MR (2018) Affective instability in those with and without mental disorders: a case control study. J Affect Disord 241:492–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.046

Mathewson KE, Lleras A, Beck DM, Fabiani M, Ro T, Gratton G (2011) Pulsed out of awareness: EEG alpha oscillations represent a pulsed-inhibition of ongoing cortical processing. Front Psychol 2:99. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00099

Michel CM, Koenig T (2018) EEG microstates as a tool for studying the temporal dynamics of whole-brain neuronal networks: a review. NeuroImage 180:577–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.11.062

Milz P, Faber PL, Lehmann D, Koenig T, Kochi K, Pascual-Marqui RD (2016) The functional significance of EEG microstates–associations with modalities of thinking. NeuroImage 125:643–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.08.023

Montgomery SA, Åsberg M (1979) A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatr 134:382–389. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.134.4.382

Murray RJ, Gentsch K, Pham E, Celen Z, Castro J, Perroud N et al (2022) Identifying disease-specific neural reactivity to psychosocial stress in borderline personality disorder. Biol Psychiatr Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 7:1137–1148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2021.11.015

Newson JJ, Thiagarajan TC (2019) EEG frequency bands in psychiatric disorders: a review of resting state studies. Front Hum Neurosci 12:521

Nolan H, Whelan R, Reilly RB (2010) FASTER: fully automated statistical thresholding for EEG artifact rejection. J Neurosci Methods 192:152–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.07.015

O’Neill A, Frodl T (2012) Brain structure and function in borderline personality disorder. Brain Struct Funct 217:767–782. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-012-0379-4

Pascual-Marqui RD, Michel CM, Lehmann D (1995) Segmentation of brain electrical activity into microstates: model estimation and validation. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 42:658–665. https://doi.org/10.1109/10.391164

Pion-Tonachini L, Kreutz-Delgado K, Makeig S (2019) ICLabel: an automated electroencephalographic independent component classifier, dataset, and website. NeuroImage 198:181–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.05.026

Preisig M, Fenton BT, Matthey ML, Berney A, Ferrero F (1999) Diagnostic interview for genetic studies (DIGS): inter-rater and test-retest reliability of the french version. Eur Arch Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 249:174–179

Qin X, Xiong J, Cui R, Zou G, Long C, Lei X (2022) EEG microstate temporal dynamics predict depressive symptoms in college students. Brain Topogr 35:481–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10548-022-00905-0

Romei V, Brodbeck V, Michel C, Amedi A, Pascual-Leone A, Thut G (2008) Spontaneous fluctuations in posterior alpha-band EEG activity reflect variability in excitability of human visual areas. Cereb Cortex 18:2010–2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhm229

Sadaghiani S, D’Esposito M (2015) Functional characterization of the cingulo-opercular network in the maintenance of tonic alertness. Cereb Cortex 25:2763–2773. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhu072

Sander C, Hensch T, Wittekind DA, Bottger D, Hegerl U (2015) Assessment of wakefulness and brain arousal regulation in psychiatric research. Neuropsychobiology 72:195–205. https://doi.org/10.1159/000439384

Sansone RA, Sansone LA (2011) Gender patterns in borderline personality disorder. Innov Clin Neurosci 8:16–20

Seeley WW (2019) The salience network: a neural system for perceiving and responding to homeostatic demands. J Neurosci 39:9878–9882. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1138-17.2019

Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, Keller J, Glover GH, Kenna H, Reiss AL, Greicius MD (2007) Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J Neurosci 27:2349–2356. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5587-06.2007

Seitzman BA, Abell M, Bartley SC, Erickson MA, Bolbecker AR, Hetrick WP (2017) Cognitive manipulation of brain electric microstates. NeuroImage 146:533–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.10.002

Simpson EH (1951) The interpretation of interaction in contingency tables. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol 13:238–241

Skodol AE, Bender DS (2003) Why are women diagnosed borderline more than men? Psychiatr Q 74:349–360. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1026087410516

Smith EE, Reznik SJ, Stewart JL, Allen JJ (2017) Assessing and conceptualizing frontal EEG asymmetry: an updated primer on recording, processing, analyzing, and interpreting frontal alpha asymmetry. Int J Psychophysiol 111:98–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2016.11.005

Spielberger CD (2010) State-trait anger expression inventory. The corsini encyclopedia of psychology. Wiley, Hoboken, pp 1–1. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0942

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA (1983) Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, CA

Terpou BA, Shaw SB, Theberge J, Ferat V, Michel CM, McKinnon MC, Lanius RA, Ros T (2022) Spectral decomposition of EEG microstates in post-traumatic stress disorder. Neuroimage Clin 35:103135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2022.103135

Treynor W, Gonzalez RD, Nolen-Hoeksema S (2004) Rumination reconsidered: a psychometric analysis. Cogn Ther Res 27:247–259

Van de Ville D, Britz J, Michel CM (2010) EEG microstate sequences in healthy humans at rest reveal scale-free dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:18179–18184. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1007841107

van Tebartz L, Fleck M, Bartels S, Altenmuller DM, Riedel A, Bubl E et al (2016) Increased prevalence of intermittent rhythmic delta or theta activity (IRDA/IRTA) in the electroencephalograms (EEGs) of patients with borderline personality disorder. Front Behav Neurosci 10:12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00012

Varela F, Lachaux JP, Rodriguez E, Martinerie J (2001) The brainweb: phase synchronization and large-scale integration. Nat Rev Neurosci 2:229–239. https://doi.org/10.1038/35067550

Visintin E, De Panfilis C, Amore M, Balestrieri M, Wolf RC, Sambataro F (2016) Mapping the brain correlates of borderline personality disorder: a functional neuroimaging meta-analysis of resting state studies. J Affect Disord 204:262–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.07.025

Whiteside SP, Lynam DR, Miller JD, Reynolds SK (2005) Validation of the UPPS impulsive behaviour scale: a four-factor model of impulsivity. Eur J Pers 19:559–574. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.556

Wu X, Lin P, Yang J, Song H, Yang R, Yang J (2016) Dysfunction of the cingulo-opercular network in first-episode medication-naive patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 200:275–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.04.046

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Geneva. The study was supported by the Swiss National Center of Competence in Research (“Synapsy: the Synaptic Basis of Mental Diseases,” Grant No. 51NF40-185897) and the Swiss National Foundation (Grant No. 32003B_156914) and by the Boninchi Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MPB—Conception and design: CP—Acquisition of Data: CB—Analysis and Interpretation of Data: MPD, TR—Drafting the article: MPD, TR, CP—Revising it for intellectual content: CB, CM, NP—Final approval of the completed article: MPD, CP, CB, CM, NP, TR.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethical committee (CER 13–081).

Informed consent

was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Thomas Koenig.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Deiber, MP., Piguet, C., Berchio, C. et al. Resting-State EEG Microstates and Power Spectrum in Borderline Personality Disorder: A High-Density EEG Study. Brain Topogr 37, 397–409 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10548-023-01005-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10548-023-01005-3