Abstract

Nearly all freshwaters and coastal zones of the US are degraded from inputs of excess reactive nitrogen (Nr), sources of which are runoff, atmospheric N deposition, and imported food and feed. Some major adverse effects include harmful algal blooms, hypoxia of fresh and coastal waters, ocean acidification, long-term harm to human health, and increased emissions of greenhouse gases. Nitrogen fluxes to coastal areas and emissions of nitrous oxide from waters have increased in response to N inputs. Denitrification and sedimentation of organic N to sediments are important processes that divert N from downstream transport. Aquatic ecosystems are particularly important denitrification hotspots. Carbon storage in sediments is enhanced by Nr, but whether carbon is permanently buried is unknown. The effect of climate change on N transport and processing in fresh and coastal waters will be felt most strongly through changes to the hydrologic cycle, whereas N loading is mostly climate-independent. Alterations in precipitation amount and dynamics will alter runoff, thereby influencing both rates of Nr inputs to aquatic ecosystems and groundwater and the water residence times that affect Nr removal within aquatic systems. Both infrastructure and climate change alter the landscape connectivity and hydrologic residence time that are essential to denitrification. While Nr inputs to and removal rates from aquatic systems are influenced by climate and management, reduction of N inputs from their source will be the most effective means to prevent or to minimize environmental and economic impacts of excess Nr to the nation’s water resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Climate change effects on US water resources are already evident, caused by alterations in precipitation patterns, intensity, and type, occurrence of drought, increased evaporation, warming temperatures, changes in soil moisture and runoff, and changes in ocean circulation (Karl and Melillo 2009). At the same time, the nation’s waters are biologically and chemically responsive to the influx of reactive nitrogen (Nr) that now pervades most freshwater and coastal ecosystems (Smith et al. 2003; Howarth et al. 2011b). The input of Nr to the conterminous US has been increasing over time; recent estimates suggest the total terrestrial Nr inputs in 2002 to the US were 28.5 Tg N year−1 (US EPA 2011). Of that, some proportion runs off, leaches, or is deposited on US water resources, which we define as streams, rivers, lakes, reservoirs, wetlands, groundwaters, estuaries and coastal waters. The amount of N removed from terrestrial systems ascribed to leaching and runoff is highly uncertain and reflects different modeling and accounting assumptions (US EPA 2011). The USGS SPARROW model estimated inputs to river systems in 2002 to be 4.8 Tg N year−1 (Alexander et al. 2008; US EPA 2011). North American riverine export to the coastal zone, inlands and drylands was estimated at approximately 7.0 Tg N year−1 by Boyer et al. (2006). Other estimates reported by Boyer et al. (2006) for North America ranged from approximately 4.8 to slightly less than 7.0 Tg N year−1.

Aquatic ecosystems are disproportionally important relative to their area for processing anthropogenic inputs of N (Galloway et al. 2003; Seitzinger et al. 2006; US EPA 2011). At the same time, aquatic biota is highly responsive to Nr additions, with responses ranging from increased fish production to loss of aquatic biodiversity. Excess Nr in the nation’s water can have negative effects on human health and promote harmful algal blooms (HABs). In the assessment below, we address the processes by which Nr and climate change together influence aquatic N cycling, and the implications, in turn, for water quality, greenhouse gas emissions, ecosystems and human health. Nitrogen inputs are the most important determinant of N concentrations and transport in aquatic ecosystems, but N cycling determines how much N is processed, buried, returned to the atmosphere, or transported downstream. Moreover, N cycling processes are strongly affected by climate (and climate change) and the extensive hydrologic manipulation of US water resources that have been ongoing since European settlement (Doyle et al. 2008; Howarth et al. 2011a, b).

Reactive N

Although few if any aquatic ecosystems in the US are intentionally fertilized, the unintentional loss of N from fertilized fields, human and livestock waste, and industrial activities have added large amounts of Nr. More than half of the shallow wells in agricultural and urban regions have Nr concentrations elevated over background values, and trends in groundwater N loading are linked to N fertilizer use (Dubrovsky et al. 2010). The loading of N from watersheds and atmospheric deposition has more than doubled the flux of N to estuaries and coastal oceans since the Industrial and Agricultural Revolutions (Boyer and Howarth 2008; Howarth et al. 2011a). Two-thirds of US estuaries are degraded from N pollution (Bricker et al. 2007; US EPA 2011). The potential of aquatic ecosystems to effectively assimilate, retain and denitrify Nr in ecosystems has been substantially reduced by large net losses of those aquatic habitats with the highest capacity to remove Nr through denitrification, including wetlands, small lakes and streams, and floodplains (Jordan et al. 2011).

Climate change

Climate change places an additional stress on the nation’s already highly managed water resources by altering precipitation, temperature, and runoff patterns. Climate was identified as a major cause of increased river discharge in the period 1971–2003 compared with 1948–1970 across much of the country (Wang and Hejazi 2011). Climate change effects vary regionally; there has been increased discharge in the Midwest and decreased discharge in the High Plains. Reduced discharge in arid regions of the western US are attributed to both climate and land use change (Wang and Hejazi 2011). Increased climate variability will be a significant component of climate change (IPCC 2007), resulting in an increase in storm intensity and also changes in the seasonality of runoff (Karl and Melillo 2009).

Each of these shifts in the hydrologic cycle will alter the interaction between inputs, retention, losses, and effects of Nr. In addition to altering flow regimes, lake levels, and depth of groundwater, there are many mechanisms by which climate change will alter how N is processed in aquatic ecosystems. The concurrent impositions of climate change and the increasing load of Nr to freshwater and estuarine ecosystems will most likely have unprecedented additive or synergistic effects on water quality, human health, inland and coastal fisheries, and greenhouse gas emissions (Online Supplementary Table).

Processing and transport of reactive N in aquatic ecosystems

Reactive N primarily enters aquatic ecosystems as ammonium (NH4 +), NO3 −, or dissolved organic N (DON), which can be incorporated into biomass or transformed in the dissolved phase to additional nitrogenous compounds. Ammonium may be transformed by nitrifying microorganisms under oxic conditions (with some exceptions) to NO3 −, nitrous oxide (N2O), or nitric oxide (NO), a precursor to tropospheric ozone formation. Denitrification takes place under anoxic conditions where NO3 − is transformed to N2O or di-nitrogen (N2), the inert gas that comprises 78 % of the atmosphere (Fig. 1). Dissolved organic nitrogen may be mineralized to NH4 +, or transported long distances downstream. The relative balance of these pathways determines the fate of reactive N entering the nation’s waters and, at the simplest level, is controlled by relatively few important environmental drivers. These include water residence time, Nr supply, available labile organic C, temperature, redox conditions and additional limiting nutrients. Shifts in climate concomitant with an increasing supply of Nr interact to affect these processes with important implications for potable water supplies, aquatic emissions of greenhouse gases [e.g., N2O, carbon dioxide (CO2), and methane (CH4)], losses of aquatic biodiversity, eutrophication of inland and coastal waters, and changes in the potential for C sequestration.

Conceptual model of N input, cycling and removal of Nr to inland waters under a preindustrial conditions and b with anthropogenic N loading from inorganic fertilizer, manure, atmospheric deposition, and sewage. The movement of Nr into and out of freshwaters is regulated by climate, hydrologic regulation, and residence time, which is designated by bowties. The middle section of this diagram is modified from Bernot and Dodds (2005)

Loading and transport of Nr to aquatic ecosystems

While alteration of the hydrologic cycle affects how N is delivered to and processed by aquatic ecosystems, the primary driver of watershed N export is the amount of Nr applied to the watershed (Howarth et al. 1996, 2011b; Hong et al. 2011). There is substantial variation in retention and ecosystem responses related to climate, topography, terrestrial ecosystem demand, and the efficacy of point source treatment, but as N inputs to catchments increase, hydrologic N exports also rise (Howarth et al. 2006, 2011b; Schaefer et al. 2009; Sobota et al. 2009). The amount of Nr exported from inland waters to coastal and marine ecosystems is determined by the balance between the inputs and the amount of N retained or denitrified in transit (Fig. 1). On average, 25 % of the human-controlled N inputs to the landscape flow downriver to coastal marine ecosystems (Howarth et al. 1996, 2006, 2011b).

Reactive N enters surface water ecosystems primarily via surface runoff, shallow subsurface flow paths, groundwater exchange, and direct atmospheric N deposition. Inorganic fertilizer and animal manure are the dominant anthropogenic sources of N in many large US river basins (Puckett 1995; Howarth et al. 2011b; Hong et al. 2011). Although Nr removal from individual fields can vary widely, approximately 50 % of the N used in agriculture is unintentionally lost to the environment, with a significant fraction flowing to freshwaters (Schaefer et al. 2009; Sutton et al. 2011; Howarth et al. 2011b; Houlton et al. 2012). In addition atmospheric N deposition contributes to most US watersheds, and is the dominant Nr source to all mountain ecosystems (Hong et al. 2011; Baron et al. 2011). The majority of the N supplied to cities, suburbs and consolidated animal feeding operations as food is converted to human and animal wastes, a large proportion of which ultimately leaches or is intentionally released from septic, sewage, lagoon and landfill systems (Galloway et al. 2007; Bernhardt et al. 2008; Dubrovsky et al. 2010). The relative importance of the major N inputs (fertilizer, atmospheric N deposition, human or animal wastes, biological N fixation) varies widely over time and regionally with land use (Hong et al. 2011).

Where the loading of N approximates background levels of approximately 1.0–4.0 kg N ha−1 year−1, flushing of terrestrial N and concurrent NO3 − concentrations are usually low (Elser et al. 2009; Baron et al. 2011). As is the case for agricultural landscapes, net N loading is also the most important determinant of net N export in non-agricultural watersheds, while climate exerts important secondary controls (Fig. 1; Smith et al. 2003; Howarth et al. 2006, 2011b). This results in the strong relationship between watershed N loading and river N concentrations across major river basins that differ in their population density and land use (Boyer and Howarth 2008; Howarth et al. 2011b). Furthermore, this relationship is also observed across high elevation undisturbed lakes that vary only in the rates of atmospheric N deposition (Elser et al. 2009; Baron et al. 2011).

Hydrologic alteration in managed ecosystems

The large increases in N loading to aquatic ecosystems over the last century have been matched by ambitious efforts to regulate and manage water movement and storage within the US (Doyle et al. 2008). Furthermore, regulation and management inadvertently alter the processes that regulate microbial and plant N-cycling in these environments.

Efforts to manage US water resources have been far-reaching and diverse. Two effects of water management have been to increase the speed with which stormwaters are routed off land and into surface waters, and to deplete base flows through enhanced water extraction and reduced groundwater recharge. In regions intensively altered for agriculture or human settlement, extensive networks of tile drains, canals or stormwater pipes have been constructed to route rain and snowmelt rapidly to receiving streams, simultaneously reducing the proportion of precipitation that infiltrates into soils and groundwater and increasing peak flows in surface channels (Dubrovsky et al. 2010). At least half of all freshwater and coastal wetlands in the US have been drained or filled for agriculture, development or waste storage (Mitsch and Gosselink 2007). Many larger streams have been channelized or dammed, reducing river residence times and isolating river floodplains while vastly increasing water and sediment storage in reservoirs. Inter-basin transfers have rerouted rivers towards cities and farms, while irrigation water withdrawals from surface and groundwaters move an ever larger proportion of water into evaporative losses rather than downstream transport.

This highly intentional water management has had a number of unintended consequences for N cycling by altering aquatic ecosystem geomorphology, hydrologic connectivity, and water residence time and flow rates. When there is less hydrologic exchange there is reduced potential for denitrification, the microbial process by which Nr is returned to the atmosphere. The converse is also true, whereby the longer residence times of waters retained by dams enhance denitrification, primary production, and the burial of organic N in sediments. Higher peak flows in managed ecosystems enhance bank erosion and channel incision in receiving streams, reducing the extent of surface and subsurface exchange between streams and their floodplains. At the same time transported sediments can clog streambeds and reduce hydrologic exchange between surface waters and stream sediments and shallow groundwater.

Although sediment loading to river networks has increased dramatically, reservoirs trap sediments and substantially reduce their export to many coastal ecosystems. The result is a net loss of coastal wetlands in the deltas of regulated rivers (Syvitski et al. 2005). In addition, increases in impervious cover from roads, roofs, and other paved surfaces have dramatically increased overland flow directly from catchment surfaces into river networks. Peak flows were found to be from 30 % to more than 100 % greater in urbanized catchments compared to less urbanized and non-urbanized catchments of the Southeast US (Rose and Peters 2001).

Even without increases in N applications to watersheds, hydrologic alterations that route rainfall efficiently into receiving streams lead to predictable increases in storm-borne delivery of N to surface water ecosystems (e.g., Shields et al. 2008; Davidson et al. 2010). Collectively, enhanced N loading and highly engineered stormwater routing vastly increase loading of N. For much of the nation, the increased storm severity predicted by many climate change models is likely to further exacerbate this trend.

The effects of climate change on aquatic N dynamics: hydrologic effects

Climate directly affects the rate of delivery of watershed N to waters. Greater N is transmitted to rivers in wetter regions than in drier regions, and more N is transported in years with high discharge compared with years of lower discharge (Caraco and Cole 1999; Dumont et al. 2005; Seitzinger et al. 2006; Howarth et al. 2011b). Some parts of the US will experience increased drought with climate change. Drought, defined as a transient deficiency in water supply, can be caused by reduced precipitation, transfers of water out of a region, or an increase in the ratio of evapotranspiration to precipitation. By drying river beds and shrinking flows, drought can disconnect streams and rivers from their floodplains or active benthic sediments. This reduces opportunities for denitrification and allows reactive N to be transported downstream. Excess nutrient buildup occurs in waters and algal blooms by reducing flow rates and water levels (Palmer et al. 2009). The occurrence of drought has increased in the Southeast and Western US over the past 50 years, while there has been a decrease in drought in the Midwest and Great Plains (Karl and Melillo 2009). These trends are expected to continue (Milly et al. 2005).

The frequency of heavy precipitation events has increased in recent decades, with little change in the occurrence of light or moderate precipitation events (Karl and Melillo 2009). The greatest increases in heavy precipitation have occurred in the Northeast and Midwest, but the frequency of intense rain and snow storms has also increased in the Southeast, Great Plains, and West (Karl and Melillo 2009). The increasing potential for flooding from intense storms or increased precipitation with climate change will increase the transport of N to the nation’s waters (Online Supplementary Table). Intense storms decrease the residence time in unsaturated soil zones leading to faster N loading to surface and groundwaters. Flooding caused by intense precipitation may overcome urban or agricultural wastewater treatment facilities, causing rapid release of N and other waste materials downstream (Kirshen et al. 2007). In dry regions such as the Southwest and in heavily developed areas with impervious surfaces, N loading is likely to occur in pulses corresponding to storms or rapid snowmelt (Shields et al. 2008; Schaefer et al. 2009).

Changes in precipitation timing will alter the delivery of N to aquatic systems. More than 70 % of N delivered to the Gulf of Mexico is derived from agricultural sources in the Mississippi River Basin, where increased winter and spring precipitation on cultivated fields may enhance the amount of N that runs off or is leached into groundwater and ultimately downriver (Smith et al. 1997; Alexander et al. 2008; Karl and Melillo 2009; Brown et al. 2011). The extensive use of tile drains in this region will increase N removal by reducing residence time of high N waters in soils where plants and microorganisms can assimilate or denitrify reactive N (Dubrovsky et al. 2010). Winter, spring, and summer precipitation has decreased in the Southeast, while summer, fall, and winter precipitation has decreased in the Northwest (Karl and Melillo 2009). Research is needed to determine the nature of the N transport response to altered seasonality in different regions of the country.

The relative importance of groundwater on stream N concentrations may change with changing hydrologic dynamics, although there has been minimal research to date on the impacts of climate change for groundwaters (Karl and Melillo 2009; Online Supplementary Table). Reduced summer and fall surface flows may increase the groundwater contribution to freshwaters. Groundwaters are already significant sources of N to streams and strongly influence the amount and timing of N delivery to downstream waters (Wiley et al. 2010). In agricultural regions where precipitation has increased, increased groundwater recharge has been accompanied by high NO3 − concentrations (McMahon and Böhlke 2006; Gurdak et al. 2007; Wiley et al. 2010). With residence times of tens to hundreds of years, groundwaters enriched with N can strongly influence stream, estuarine, and well water quality for decades. Because of this, downstream and groundwater quality responses to management or climate change may lag behind their upstream applications and influences.

The effects of climate change on aquatic N dynamics: temperature effects

Increasing air temperatures directly warm lotic and lentic ecosystems in ways that affect physical, chemical and biological structure and function (Kling et al. 2003; Stuart et al. 2011). Shorter ice-covered periods for lakes and rivers, earlier onset and increased intensity and duration of stratification, higher maximum, minimum, and mean annual temperatures, lower dissolved oxygen levels, and decreasing or fluctuating lake levels have already been observed (Magnuson 2000; Kling et al. 2003; Karl and Melillo 2009). These changes have the potential to affect aquatic N cycling (Online Supplementary Table). A longer ice-free season will result in enhanced summer stratification wherein both hypolimnion and epilimnion will have extended periods of warmer temperatures. Persistent warm epilimnion temperatures will be accompanied by reduced nutrient availability due to prolonged separation from the benthos, a key source of dissolved nutrients.

Within the water column, there is evidence for strong temperature dependence of both heterotrophic and autotrophic microbial NO3 − utilization (Reay et al. 1999). Several studies report N currently accumulating as NO3 − in the water column of cold, oligotrophic environments (Finlay et al. 2007; Sterner et al. 2007; Baron et al. 2009). Isotopic evidence suggests some of the NO3 − was microbially-converted, or mineralized, from atmospherically-deposited NH4 + (Campbell et al. 2002; Finlay et al. 2007). Multiple mechanisms that include temperature and organic C have been proposed to explain why water column NO3 − is going unused, and this is an area of active research (Taylor and Townsend 2010).

Intensified stratification will increase the extent of hypoxia and anoxia in the hypolimnion of lake ecosystems. Rates of denitrification may increase in the sediments and hypoxic water column of stratified lakes, reducing the amount of N exported to coastal zones (Online Supplementary Table). However, it is equally reasonable to think that increased stratification will decrease denitrification by limiting the amount of contact NO3 − rich water has with denitrifying sediments in hypolimnia. Although it is difficult to infer how microbial communities will respond to gradual temperature increases based on short-term studies, a recent synthesis of empirical and modeling results suggests denitrification could increase as much as twofold with a 3 °C increase (Veraart et al. 2011).

Temperature may alter stoichiometric ratios of nutrients available to biota. Biomass C:N of a wide range of organisms, including many plankton, is generally thought to increase with increasing temperature (Woods et al. 2003). Biomass C:N ratio is inversely proportional to the amount of N retained in biomass (Elser and Urabe 1999). Thus, increasing C:N of planktonic biomass should decrease N demand of planktonic organisms and increase the amount of N that is recycled to the dissolved pool. In the absence of adaptation to changing thermal regimes this will further raise the amount of Nr in these ecosystems.

There is a need for further research into the mechanisms by which changing temperatures will alter aquatic stoichiometry and microbial processes, but the indications are that microbial N transformation pathways and planktonic N-demand will be altered as temperature warms.

The effects of climate change on aquatic N dynamics: denitrification and burial

Aquatic ecosystems are critically important denitrification hotspots, with per-unit-area denitrification rates approximately ten-fold (on-average) the per-unit-area rates in soils (Seitzinger et al. 2006). Denitrification, an important process by which Nr is removed from ecosystems and returned to the atmosphere, requires low oxygen levels, NO3 −, labile organic C, and sufficient residence time for N-rich water to interact with microbes (Fig. 1; Seitzinger et al. 2006; Mulholland et al. 2008). These conditions occur in saturated soils and sediments of lakes, reservoirs, small streams, floodplains and wetlands. One estimate using spatially-distributed global models suggests 20 % of global denitrification occurs in freshwaters (e.g., groundwaters, lakes, and rivers), compared with 1 % in estuaries, 14 % in ocean oxygen minimum zones, 44 % in the continental shelf, and 20 % in terrestrial soils (Seitzinger et al. 2006). Aquatic systems and associated deltas and floodplains are also important sites for sediment burial of particulate N.

Using methods described below and in Table 1 we estimate that US aquatic systems retain or remove 8.39 Tg N year−1 (Table 1). We also estimate that US aquatic systems release 0.6 Tg N2O–N year−1 to the atmosphere, an N2O amount significantly higher than other estimates that do not quantify by aquatic ecosystem type (US EPA 2011) and of the same order as N2O production from all other US sources. Hence, to the extent that aquatic N loading and climate changes affect N2O production, denitrification and N burial rates, these perturbations are also likely to strongly influence GHG production, downstream N transport fate, and the integrity of freshwater and coastal ecosystems.

Wetlands

Both natural and constructed wetlands have great capacity for N storage in soils and biomass and removal via denitrification (Seitzinger 1988). Total Nr removal by wetlands in the contiguous US has been recently estimated at 5.8 Tg N year−1 (Table 1; Jordan et al. 2011). This is greater than any other aquatic ecosystem type in this analysis (Fig. 2a), and more than half the rate of annual inorganic N fertilizer application in the US (approximately 11Tg N year−1; US EPA 2011; Sobota et al., in press). Although N storage and removal increase in response to N loading, and evidence for N saturation of wetlands is scant (Jordan et al. 2011), it is not clear how N and climate will interact to influence wetland N storage. Wetland soils will have reduced capacity to store and remove N if they dry in response to increased evapotranspiration or decreased precipitation. Conversely, increased frequency and severity of pulsed heavy rains could either decrease wetland N removal efficiency by decreasing N and water residence time, or increase wetland N retention by inundating a greater area, thereby promoting the formation of anaerobic sites where denitrification can occur. Interactions among climate, N loading, and wetlands are not well constrained, but, given the efficiency with which wetlands can remove N, this is an area of critical future research.

a Nr removal (through either burial or denitrification) in US freshwater systems. Values are in percent and illustrate importance of wetlands in Nr removal; b N2O production in US freshwaters, in percent. Wetlands produce the most total N2O, followed in importance of emissions by streams and rivers, reservoirs, lakes, and wastewater treatment facilities

Lakes and reservoirs

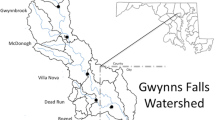

Using the Nitrogen Retention in Reservoirs and Lakes (NiRReLa) model (Harrison et al. 2009), we estimate that 2.59 Tg N year−1 is removed by US lakes and reservoirs (Table 1). This rate of N removal is equivalent to roughly half the annual rate of inorganic N fertilizer application in the US (US EPA 2011; Sobota et al., in press). Locally, the capacity for N removal by lakes and reservoirs often matches N inputs to aquatic systems (Harrison et al. 2009). Reservoirs trap and remove N, accounting for over two-thirds (68 %) of total N removed by all lentic waters in the US despite occupying only 10 % of the US lentic surface area. The dominance of reservoirs with respect to N retention is due to their greater N uptake velocities, watershed source areas and greater average N loading rates compared to lakes (Harrison et al. 2009; Table 1). Small reservoirs (surface area <50 km2) are disproportionately important, accounting for 84 % of the N removed in reservoir systems. Small lakes (surface area <50 km2) also retain more N than large (surface area >50 km2) lakes (1.1 and 0.59 Tg N year−1 for small and large lakes, respectively; Table 1). This is due to a combination of factors, including the greater numbers of small lakes than large ones (Downing et al. 2008). Rates of lake and reservoir N removal are greater in the agricultural and urbanized eastern US than the West, although there are hotspots for lentic N retention in western regions with intensive agriculture (Fig. 3).

Total N retention in lentic systems in the conterminous US (kg N km−2 year−1). Figure produced with methods from Harrison et al. (2009)

Together, these insights suggest that lentic systems constitute important sites for N retention and removal at local, regional, and national scales, that small reservoirs and small lakes are particularly important sites for N retention, and that lentic N retention is particularly important in agricultural and urban regions (Fig. 2a). Hence, it is important to understand how small reservoirs in agricultural areas respond to the dual stresses of increased N loading and climate change. Up to a point, increased N loading stimulates N retention across a broad range of aquatic ecosystem types, including lakes and reservoirs (Seitzinger et al. 2006). The threshold, however, beyond which denitrifying microbes can no longer keep up with N loading in lakes and reservoirs is not well defined, and even the existence of such a threshold is debated (e.g., Jordan et al. 2011). Climate effects on N transformations and interactions between climate and increased N loading are even less well-understood, but almost certain to be important.

Streams and rivers

We scaled a recent global estimate of lotic N retention (Beaulieu et al. 2011) to the US using lotic surface areas from Butman and Raymond (2011). US streams and rivers denitrify approximately 0.73 Tg N year−1. Although substantially less than the amount stored or removed by lakes, this amount of N removal is significant relative to N inputs (roughly 7 % of inorganic fertilizer application in the US), and important both spatially and temporally (Fig. 2a; Dumont et al. 2005; Alexander et al. 2000; Peterson et al. 2001).

The amount of denitrification occurring in streams and rivers is spatially variable, depending on contact time of water with sediments, stream temperature, the supply of biogenic nutrients, and respiration rates (Boyer et al. 2006; Alexander et al. 2009). The NO3 − removal efficiency of streams varies seasonally, and is reduced during months with high discharge while enhanced during months with low discharge (Alexander et al. 2009). This creates a direct connection of NO3 − removal efficiency with climate change, with reduced denitrification potential during high flows caused by extreme precipitation and flooding events, and enhanced denitrification potential during periods of low discharge. A study of more than 300 stream-reach measurements and experiments concludes the percentage of stream NO3 − load delivered to watershed outlets is strongly affected by the cumulative removal of NO3 − in headwaters, emphasizing the importance of connectivity of N-rich water with microbe-rich sediments (Alexander et al. 2009). Denitrification generally increases with increasing NO3 − inputs, but the denitrification efficiency may decline when the microbial capacity for NO3 − uptake becomes saturated (Mulholland et al. 2008; Wollheim et al. 2008). Denitrification also occurs in higher order streams during transport (Alexander et al. 2008, 2009).

Groundwater

Groundwater denitrification rates vary depending on redox state, the availability of electron donors, and aquifer residence time. Some studies show that although groundwater denitrification rates are low, NO3 − removal can be nearly complete because of long residence times (Puckett and Cowdery 2002). Irrigation may reduce the residence time for NO3 − in groundwater, diminishing denitrification potential (Böhlke et al. 2007). Riparian buffers provide additional opportunities for denitrification, but their effectiveness varies depending on hydrogeologic controls (Puckett 2004). Site-specific denitrification estimates for groundwater have not been scaled up, so national estimates are lacking.

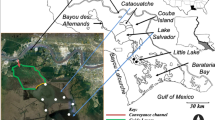

Estuaries and continental shelves

In estuaries and continental shelves, similar to other aquatic environments, there is only a thin layer of aerobic sediments where denitrification occurs. There is thus a high degree of connectivity between the N load in the form of NO3 − and denitrifying microbes (Seitzinger et al. 2006). Denitrification is enhanced in the suboxic waters of estuaries (Seitzinger et al. 2006; Codispoti 2010). In addition, the percentage of N denitrified is strongly tied to residence time (Harrison et al. 2009), which in estuaries is affected by geomorphology, river discharge, and tidal flushing (Nixon et al. 1996). The delivery of Nr to estuarine and coastal ecosystems, which is already high, will respond to an altered upstream hydrologic cycle from climate change.

N stimulation of greenhouse gas production

Because greater N loading increases N2O production in all aquatic systems, and because of the potency of N2O in both planetary warming and stratospheric ozone depletion, a better quantification of sources and processes is needed (Verhoeven et al. 2006; Beaulieu et al. 2011; McCrackin and Elser 2011; Pinder et al. 2012). Although N2O emissions are estimated to be ≤1 % of the N denitrified in aquatic systems, this amount is important with respect to global N2O budgets (Beaulieu et al. 2011). The N-loading of inland waters is also likely to stimulate production of other greenhouse gases such as CH4 and CO2 where N is a limiting nutrient.

N2O emissions

N2O fluxes from all rivers, coastal ecosystems and the open ocean are estimated at 5.5 Tg N year−1, or 31 % of total annual global N2O emissions, including both natural and anthropogenic sources (Bange et al. 2010; Kroeze et al. 2010; Syakila and Kroeze 2011). Globally, combined N2O emissions from rivers and estuaries roughly doubled between 1970 and 2000 (Kroeze et al. 2010).

The 2011 US EPA US greenhouse gas inventory suggests 0.05–0.09 Tg N2O-N, roughly 9 % of the total anthropogenic emissions, is produced annually from US aquatic systems, but does not partition between lakes reservoirs, groundwaters, streams or wetlands (US EPA 2011). Summing N2O estimates for individual aquatic system types, we estimate a cumulative annual aquatic N2O production rate of 0.58 Tg N2O N year−1 (Table 1). This is more than tenfold greater than the US EPA (2011) estimate, suggesting that aquatic N2O production is roughly equivalent to all terrestrially-based N2O sources in the US. Although the values are poorly constrained, our initial calculations suggest a critical role for aquatic systems, especially wetlands, in the US N2O budget (Fig. 2b). The discrepancy between the EPA values and our calculations also suggest much more research is needed. Reducing N inputs to surface waters may be an effective way to lower aquatic N2O production and subsequent emissions.

Wetlands and groundwaters

Based on reported wetland N retention rates and N2O production efficiencies, we estimate that 0.37 Tg N2O N year−1 is produced by wetlands (Table 1). As with denitrification, N2O production is several-fold greater than from any other aquatic system type, and accounts for 64 % of freshwater N2O production (Fig. 2b). Better understanding of wetland N2O production will be critical as climate and N loadings change. The proportional yield of N2O from nitrification can increase under low oxygen conditions in wetlands, while the proportional yield of N2O from denitrification can increase under conditions of high oxygen or low bioavailable C. It is often hard to determine which process dominates N2O production, and thus to predict how N2O emissions may change under future climate scenarios. For groundwaters the rate of N2O emissions is highly responsive to both N loading and hydrologic transport.

Streams, rivers, and lakes

Small headwater streams are active sites for N2O production, particularly where inorganic N concentrations are elevated by anthropogenic N loading. Globally, N2O release to the atmosphere from streams and river networks was estimated as equivalent to 8 % of the human-caused N2O emission rate, a value three times larger than IPCC estimates (Beaulieu et al. 2011). The US contribution from streams and rivers is estimated at 0.048 Tg N year−1 (Table 1) by multiplying the global estimate by the fraction of lotic surface area for the US. Streams and rivers provide 8 % of US freshwater N2O (Fig. 2b). A conservative appraisal of N2O production from lakes based on inputs solely from atmospheric N deposition suggests an additional 0.04–2.0 Tg N year−1 (McCrackin and Elser 2011). When N loading to lakes (excluding reservoirs) included all N sources, values for N2O production from lakes rose to 0.043 Tg N year−1, or 8 % of freshwater N2O production (Table 1; Fig. 2b).

Estuaries, continental shelves, oceans

Contributions from North American estuaries to current global N2O emissions are estimated at 0.03 Tg N year−1 (Kroeze et al. 2005). Estuarine N2O production reflects direct increases in both nitrification and denitrification as more N is processed through estuaries and continental shelf systems with increasing Nr inputs (Seitzinger and Kroeze 1998). Emissions of N2O also increase with greater area and intensification of eutrophication and hypoxia—conditions that favor denitrification as well as the efficiency of N2O production during nitrification (Codispoti 2010). The rise of estuarine hypoxia is closely tied to increased delivery of N (NRC 2000; Díaz and Rosenberg 2011). The potential increases in N2O emissions associated with the expansion of estuarine hypoxia is not well quantified but represents an example of indirect linkages between N-cycle alterations and climate forcing.

As with other aquatic ecosystems, estuarine N2O fluxes are spatially heterogeneous—a fact that introduces sizeable uncertainties in estimates of mean fluxes (see Bange et al. 1996). Globally, continental shelves account for an estimated N2O input of 0.6 Tg N year−1 to the atmosphere (Seitzinger and Kroeze 1998). Upwelling-dominated shelf systems such as those along the US west coast represent strong sources of N2O to the atmosphere (Nevison et al. 2004b). Nitrogen budgets of continental shelves that were historically dominated by oceanic inputs are now heavily influenced by human activities, particularly in the North Atlantic and the Western Pacific (Howarth 1998; Kim et al. 2011). For continental shelves in the North Atlantic, budget estimates of estuarine export and atmospheric deposition of Nr suggest one-third of N2O fluxes come from anthropogenic sources (Seitzinger et al. 2000). For the ocean as a whole, Duce et al. (2008) estimated that by the year 2000 anthropogenic atmospheric N deposition had increased N2O emissions by 1.6 Tg N year−1 (32 % of total ocean net flux), with emissions expected to increase to 1.9 Tg N year−1 by 2030. While preliminary, given the vast size of the ocean, these estimates highlight the dramatic influence of continental N exports on changes in global ocean N2O fluxes and the marine N cycle in general.

In addition to increased output of marine N2O due to anthropogenic N-loading and climate changes to the continental hydrologic cycle, climate change can also modulate marine N2O fluxes through changes in ocean oxygen inventory. Modeling studies, many reviewed in Keeling et al. (2010), converge on common forecasts of sizeable declines in the oxygen inventory of the ocean in response to greenhouse gas forcing over century and millennial time-scales. Projections of oxygen declines reflect the combined effects of reduced oxygen solubility from ocean warming and reduced ventilation from stratification and circulation changes (Schmittner et al. 2008; Frölicher et al. 2009; Shaffer et al. 2009). Oxygen reductions due to changes in organic C flux via shifts in organic matter C:N stoichiometry (Oschlies et al. 2008) and settling (Hofmann and Schellnhuber 2009) in response to ocean acidification have also been observed. Recently the sensitivity of oceanic hypoxia volume to climate variability through increases in export production and vertical displacement of oxygen minimum zones into regions of higher respiration potential has been noted (Deutsch et al. 2011). Because oceanic contributions to the oxygen budgets of continental shelves and estuaries can be substantial (Grantham et al. 2004; Brown and Power 2011), climate-dependent changes in ocean oxygen inventories can potentially accentuate eutrophication impacts and increase N2O flux from coastal systems (Naqvi et al. 2010). The air-sea flux of N2O is dependent on both concentration gradients and physical forcing such as wind (Nevison et al. 2004a) and storm-induced ventilation (Walker et al. 2010). Projections of physically-driven changes in N2O flux are not available, but projected scenarios of strengthened upwelling wind forcing (Bakun et al. 2010), as well as increases in the intensity and/or frequency of storm events (Bender et al. 2010) suggest the potential for further exacerbation of marine N2O fluxes will result from climate change.

Engineered systems

Constructed treatment wetlands and wastewater treatment plants that receive high N loads produce more N2O than natural ecosystems and contribute a substantial fraction of the total N2O produced from managed water resources (Kampschreur et al. 2009; Townsend-Small et al. 2011). Existing wastewater treatment plants in the US emit approximately 0.06–0.1 Tg N year−1 as N2O, or 14 % of US freshwater N2O production (Table 1; Fig. 2b; US EPA 2011), and the Nr in effluents from both treatment wetlands and facilities can stimulate further N2O production in receiving rivers (Beaulieu et al. 2010).

Most US wastewater treatment plants are not designed to remove nutrients. Removal efficiencies could be improved to reduce N effluent loads by 40–60 % by enhancing the engineered capabilities for denitrification (US EPA 2011). Wastewater treatment systems currently dentrify ~2.0 Tg N year−1 from treated waters (US EPA 2011).

Water reclamation projects that cleanse municipal water for re-use for irrigation or surface and groundwater replacement are used in arid parts of the US, such as southern California, and may become more common as water scarcity increases (Gleick 2003). One study found that the rates of N2O production at water reclamation plants may be several orders of magnitude greater than N2O emissions from agricultural activities or traditional waste treatment facilities (Townsend-Small et al. 2011). As climate change increases water scarcity across the country and the use of technologies to cleanse and re-use water increases, increased N2O emissions from water reclamation facilities may result in a positive feedback that exacerbates climate warming.

Reservoirs

The N2O emissions from reservoirs have been poorly investigated, but the potential is high since many reservoirs are eutrophic with high N loads from surrounding watersheds (Liu et al. 2011). If scaled up from measurements from two China reservoirs using the sum of small and large reservoirs of 248,000 km2 (Harrison et al. 2009), US reservoir N2O fluxes are estimated at 0.02–0.05 Tg N year−1. This value is similar to the 0.037 Tg N year−1 (6 % of US freshwater N2O production, Fig. 2b) calculated by us using the approach of McCrackin and Elser (2011) for estimating N2O production and the N loading rates provided by Harrison et al. (2009). Liu et al. (2011) found that deep waters of reservoirs used for hydroelectric generation were supersaturated with N2O year-round, as was water directly downstream, suggesting that deep waters released for hydropower are additional sources of N2O produced by reservoirs.

N stimulation of CH4 emissions

Increased N delivery to wetland ecosystems is likely to elevate emissions of CH4 produced by methanogenic microbes during the anaerobic decomposition of plant material (Liu and Greaver 2010). Natural wetlands and rice paddies are an important part of the global CH4 cycle, contributing 230 Tg CH4 year−1 and 110–120 CH4 Tg year−1, respectively (Fletcher 2004). Most experimental additions of N to both natural wetlands (e.g., Aerts and de Caluwe 1999) and rice paddies (e.g., Zheng et al. 2006) increased CH4 emissions, although a few experiments found no effect (Keller et al. 2005). In a meta-analysis of over 300 field studies, N additions between 30 and 400 kg N ha−1 year−1 caused an average of 95 % increase in CH4 emissions, with emissions increasing by 0.008 kg CH4–C ha−1 year−1 per kg N ha−1 year−1 (Liu and Greaver 2010). Several explanatory mechanisms have been proposed: N stimulation of primary production, increasing the organic matter pool available for decomposition and shifting benthic redox states; stimulating rates of decomposition by relieving N limitation to the decomposer biomass (Schmidt et al. 2004); and NH4 + inhibition of CH4 oxidation (Bodelier and Laanbroek 2004).

Lake ecosystems are also strong sources of CH4, currently emitting 8–48 Tg C year−1 from lakes and estimated at 3–10 times greater from reservoirs (Tranvik et al. 2009). Together, lakes and reservoirs contribute approximately 103 Tg year−1 of CH4 to the atmosphere, a CO2 equivalent of roughly 25 % the estimated terrestrial CO2 sink (Bastviken et al. 2011). With climate change, increased lake primary production due to a combination of nutrient load and warmer waters will increase the prevalence of bottom water anoxia, causing a concurrent increase in CH4 production and evasion (Tranvik et al. 2009).

N stimulation of the C cycle

Heterotrophic metabolism and decomposition can increase in response to N enrichment in streams but responses are varied. Increases in heterotrophic metabolism are observed when detrital C:N is high (Benstead et al. 2009) but not in N saturated systems with low C:N (Simon et al. 2010). Because temperature often increases heterotrophic activity and decomposition, interactive effects on temperature and N on C cycling interactions may be strongest in N-limited ecosystems with high C:N detritus.

Given that N often stimulates primary production in freshwaters, N loading has the potential to increase C burial in lake and reservoir sediments. Few studies have examined the specific effect of N on C burial, but eutrophication, particularly caused by agriculture, generally enhances rates of aquatic C sequestration (Kastowski et al. 2011). The estimated C mass accumulation rate for European lakes in agricultural areas ranged 22–80 g C m−2 year−1, compared with ~3 g C m−2 year−1 in areas without surrounding croplands (Kastowski et al. 2011). Downing et al. (2008) reported rates of C burial up to 6987 g C m−1 year−1 in the Midwestern US. There can be up to tenfold greater C burial in response to nutrient enrichment in reservoirs (Vanni et al. 2010). The C mass accumulation rates for European lakes reconstructed from sediment cores were 100 % greater in recent sediments than the long-term mean accumulation rate, and Kastowski et al. (2011) suggest this is due to increased primary productivity and eutrophication in agricultural and densely populated areas.

Decreased runoff and increased consumptive water use in temperate regions with climate change may shrink lake and reservoir size and increase primary production and increased organic C burial (Downing et al. 2008; Tranvik et al. 2009). Given the large C sink in freshwater lakes and wetlands the influence of N on organic C burial deserves more attention (Cole et al. 2007).

Organic-rich sediments are capable of storing N as well as C. Streams, lakes and reservoirs have the light penetration, algal and macrophyte primary production, and interaction between water and benthic sediments that promote biologically-driven nutrient uptake, sedimentation and ultimately burial (Boyer et al. 2006; Mulholland et al. 2008; Harrison et al. 2009; Brown et al. 2011). While Tranvik et al. (2009) proposed a global value of 600 Tg C, there is great uncertainty in the estimate of how much N is buried as organic matter in lake and reservoir systems. We estimated N burial using a range of sediment C:N of 8–24 based on trophic state and land use (Kaushal and Binford 1999, Duc et al. 2010). If global annual C sequestration rates for lakes is 22 Tg C year−1 (Kastowski et al. 2011), 25–75 Tg N could be sequestered in all lake sediments, accumulating at a rate of 0.9–2.8 Tg N year−1 (Kastowski et al. 2011).

N and C sequestered in lake sediments are not necessarily permanently buried. Gudasz et al. (2010) found a strong positive relation between temperature and organic C mineralization. They conclude future organic C burial in boreal lakes could decrease 4–27 % under IPCC scenarios of warming due to enhanced temperature-dependent microbial activities (Gudasz et al. 2010). This suggests denitrification rates, which are similarly stimulated by warmer temperatures and greater availability of NO3 −, may reduce the quantity of N buried in lakes with climate change.

Consequences of N—climate interactions on ecosystem services

The interactions of anthropogenic N loading and climate change, will have implications for a number of ecosystem services, including economic costs (e.g., changes to fish harvests, property values, water treatment, and health care), adverse effects on human and wildlife health, and those changed by ocean acidification. Freshwater diversity, which has been altered by a combination of habitat loss, homogenization of flow regimes, and eutrophication, will also be diminished by excess N and changes to thermal properties (Hobbs et al. 2010; Porter et al. 2012).

Economic impacts

The combined effect of N loading and climate change on the economic value of water resources and related products has yet to be evaluated, and even the separate economic effects of N loading or climate change are difficult to determine. Economic assessments related to N loading have been conducted for coastal fish harvests, recreational uses of inland and coastal waters, lakefront property values, and water treatment and human health costs (Compton et al. 2011). Similar to increased productivity on agricultural lands when N is added, N loading to coastal waters increases fish and invertebrate harvests initially. Beyond the initial stimulation of productivity additional N availability has either no effect or a negative effect (Breitburg et al. 2009). A positive economic outcome of increased fish landings may be offset by some negative economic effect on recreational activities caused by eutrophication, increased turbidity, and hypoxia and loss of habitat for specific organisms (Breitburg et al. 2009). Hypoxia-related fish mortality may increase, but this is highly uncertain because multiple climate drivers stimulate hypoxia responses (Díaz and Rosenberg 2011). The economic effects of hypoxia are difficult to quantify, even when there are mass mortality events. Freshwater eutrophication also reduces waterfront lake property values and recreational use across all waters (Dodds et al. 2009).

As eutrophication increases with warmer water temperatures, there will be costs associated with upgrades of municipal drinking water treatment facilities, the purchase of bottled water, and the health costs of NO3 − in drinking water leading to toxicity and disease (Compton et al. 2011). Substantial costs will be incurred upgrading wastewater and drinking water facilities to accommodate sea level rise and flood risks. Kirshen et al. (2007) note the interdependencies of urban infrastructure, flood control, water supply, drainage, and wastewater management. More than $200 billion in wastewater management infrastructure needs have been identified for addressing nutrient control from traditional and storm water sources (US EPA 2011).

The US will increasingly rely on groundwater for drinking water under future climate change scenarios (Karl and Melillo 2009), creating a strong potential for increased costs for treating exposure to NO3 −-stimulated disease. Nearly two million Americans use groundwater in areas with modeled NO3 − concentrations >5 mg L−1 (Nolan and Hitt 2006). Nitrate in drinking water contributes to the formation of N-nitroso compounds which are associated with cancer, diabetes, and adverse reproductive outcomes (Ward et al. 2005; Peel et al. 2012). The NO3 − maximum contaminant level of 10 mg N L−1 is exceeded in 22 % of domestic wells in agricultural areas (Dubrovsky et al. 2010). Model results suggest groundwater supplies from below 50 m may exhibit future contamination as NO3 − in shallow groundwater migrates downward (Nolan and Hitt 2006; Exner et al. 2010; Howden et al. 2010).

Human and wildlife health

Increasingly, N enrichment is correlated in waters with pathogen abundance and human and wildlife diseases (Johnson et al. 2010). Climate warming opens the possibility for more vector-transmitted diseases to migrate to higher latitudes, where N loading may enhance their success (Johnson et al. 2010). The interaction of N and disease can heighten several disease pathways, including direct disease transmission, vector-borne infections, complex life cycle parasites, and non-infectious diseases (Johnson et al. 2010). Malaria and West Nile, which show increased breeding success in high NO3 − waters, have been identified as two diseases that may respond to the combined effects of Nr and warming, although their incidence can be tempered by mosquito control efforts (Gage et al. 2008; Johnson et al. 2010).

Harmful algae are directly connected to nutrient enrichment and warm waters. HABs are increasing in outbreak extent, causing a range of diseases from direct dermatitis, such as swimmers itch, to severe food poisoning, cancer, and paralysis (Heisler et al. 2008; Johnson et al. 2010; Peel et al. 2012). Hoagland et al. (2002) reported more than 60,000 incidents of human exposure to algal toxins annually in the US, resulting in about 6,500 deaths. HABs are also responsible for massive fish kills and marine mammal kills (Morris 1999).

Ocean acidification

Acidification causes direct harm to calcifying shellfish and crustaceans (Howarth et al. 2011a). Changes in climate and the N cycle will intensify ocean acidification, and there are feedbacks from acidification to N-cycling (Doney et al. 2009). Impacts on the N-cycle include pH-dependent reductions in nitrification rates and enhancement of open ocean N-fixation (Levitan et al. 2007; Beman et al. 2011). Eutrophication increases the vulnerability of coastal ecosystems to ocean acidification through interactions between low oxygen levels and inorganic C increases (Howarth et al. 2011a). As a consequence, C chemistry changes from ocean acidification are disproportionately large in hypoxic water bodies. Already, coastal upwelling shelves and estuaries subject to eutrophication exhibit partial pressure CO2 levels in excess of values that are not anticipated to be reached by the mean surface ocean until the next century (Feely et al. 2009).

Guidance for nitrogen management under climate change

Water resources in the US are faced with the simultaneous and interactive forcing from two large stresses: climate change and excess Nr. While responses will vary over space and through time, climatic events and warming will almost certainly alter the rates of denitrification and N transport, largely in response to flushing and temperature. Climate change will alter landscape and in-stream hydrologic connectivity and residence time in response to both flooding and drought, and warmer waters may increase the rates of Nr cycling by biota but may also intensify the limitation of other nutrients due to increased stratification of waters. Thus there is no reason to assume that climate change will compensate for the negative effects of current and anticipated aquatic Nr loading.

The most direct opportunity to mitigate detrimental Nr effects on aquatic ecosystems is by reducing Nr inputs. Section 303 of the Clean Water Act requires states to adopt water quality standards and criteria that meet state-identified uses for each water body (US EPA 2011). National nutrient criteria guidance has been published based on eco-regional directions (US EPA 2000a, b, 2007; 2011), however, relatively few states have adopted numeric criteria to date. Once criteria have been adopted they can identify impaired waters, where management goals like the total maximum daily load (TMDL) or the critical load (CL) can be established.

Nitrogen emissions from fossil fuel combustion, transportation and agricultural sources contribute significant Nr to waters via atmospheric deposition. Existing National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) do not yet adequately protect ecosystems from Nr deposition in many parts of the country (US EPA 2008; Greaver et al. 2012). Because atmospheric deposition loads of Nr are related to ambient NO x air quantities, existing air quality regulations could possibly be used to reduce N deposition for water resource protection (Greaver et al. 2012). However, the NAAQS apply only to NO x emissions, while emissions of NH3 are mostly unregulated, and NH3 emissions acts in combination with NOX to cause nutrient enrichment.

Whereas the TMDL represents the maximum amount of a pollutant allowed by law to enter a waterbody via surface or ground water, the CL, used to evaluate the ecosystem effects of airborne pollutants, has not yet been formally adopted for management in the US. It is widely used in Europe and Canada (Burns et al. 2008; Greaver et al. 2012). The CL is defined as the quantitative estimate of an exposure to one or more pollutants below which significant harmful effects on specified sensitive elements of the environment do not occur according to present knowledge (Nilsson and Grennfelt 1988). Critical loads have been proposed for water quality thresholds overcome by atmospheric deposition (Baron et al. 2011; Pardo et al. 2011).

Reduction of Nr inputs at their source will have the longest lasting effects on Nr in aquatic systems, but there are additional opportunities to further mitigate Nr stress. Maintaining and restoring extensive riparian buffers may increase Nr storage and denitrification. Retrofitting engineered landscapes so that polluted waters from metropolitan regions and agricultural fields are not piped directly into rivers may allow longer residence times and more efficient removal of Nr in watersheds. However, much research is needed on effective restoration practices. There is limited evidence that large investments in river and wetland restoration over the last decade have been successful at reducing N concentrations (Bernhardt et al. 2008). Groundwater and river Nr pollution can be substantially reduced by capturing a larger proportion of human and livestock waste. Investments in tertiary treatment of human sewage and expanded municipal sanitary infrastructure to capture and treat the sewage of the one quarter of American households currently relying on septic systems would substantially improve water quality in areas where most Americans live, but care must be taken to minimize the N2O loss to the atmosphere that accompanies such treatment (Bernhardt et al. 2008; Kampschruer et al. 2009; Townsend-Small et al. 2011). Tighter regulations on consolidated animal feeding operations that require greater livestock waste containment and treatment could reduce point source N loading in agricultural regions (Schlesinger 2009).

Options for retaining and removing Nr once it enters running or stationary waters rely upon reducing flow and increasing biological sequestration or denitrification (Craig et al. 2008). The large-scale construction of major reservoirs throughout the US has enhanced retention and denitrification of N in sediments, but as new reservoir construction slows and older reservoirs fill with sediment this capacity is likely to be reduced (Doyle et al. 2008; Harrison et al. 2009). Denitrification and retention of material in river floodplains, backwaters and wetlands may also be achieved by increasing the connectivity between long residence time habitats (Mitsch et al. 2001).

Increasing water use efficiency in agriculture, industry, and municipal supply will build some resilience into US water resources that may prove beneficial to freshwater and coastal ecosystems. Preventative actions to upgrade urban infrastructure and relocate Nr sources from floodplains are estimated to be cost-effective adaptation options for protecting water quality from flooding and sea level increases.

Strategies to reduce the combined impact of N loading and climate change on US water resources will take many years to be effective. Slow-moving groundwater NO3 − may require decades for benefits from proper Nr management practices to be realized under current and future climates. Ecosystem restoration is not yet a mature discipline, and research suggests many restoration practices, such as attempting to reduce N removal from agricultural lands with riparian buffers or stream restoration, are ineffective (Puckett 2004; Craig et al. 2008). While there are locations and approaches that might increase the success of restoration efforts, they are no substitute for the direct reduction of N from its sources.

Research needs

Research and monitoring are needed to increase our understanding of the sources and fate of Nr in US waters, how to mitigate the potential adverse effects of climate change, and how to reduce the transport of Nr from terrestrial to aquatic systems. These are itemized below.

-

(1)

The uncertainties of estimates of N storage and removal in different aquatic ecosystems, including groundwater, highlight the need for a better N mass balance for the US.

-

(2)

For all aquatic ecosystems a better understanding of the effects of climate change on Nr transport and transformations is needed. This includes continued monitoring, evaluation of existing relationships, and modeling of Nr-climate change dynamics. Effects include responses of Nr transport and transformation to increased climate variability, altered seasonality, and a shift in mean conditions, in addition to an increase in extreme hydrologic (floods, droughts) and thermal events.

-

(3)

A greater understanding of the interactions of N with other element cycles (e.g., C, phosphorus, silica) in aquatic systems is needed. The influence of Nr on C storage in sediments, and the residence time of C and N stored in sediments, should be quantified in order to evaluate their importance to the global C cycle. Along with the need for better evaluation of nutrient stoichiometry, there is a gap in our understanding of DON in aquatic ecosystems.

-

(4)

Are there critical physiological, ecological, or human health thresholds associated with the interactions of climate with Nr? Are thresholds temperature-, flow-, or concentration-dependent? Can this information be used to identify management strategies that may be protective of ecosystems and societal water resources? Are existing standards, including TMDLs, CLs, and water quality health standards, sufficient for ecological and human health protection?

-

(5)

Research and monitoring are needed to understand farm management effects on downstream water quality. How effective are Best Management Practices? Where are they, or other management practices, taking place and how effective are they in retaining nutrients? Research into the effectiveness of stream, river, wetland, and riparian restoration techniques under climate change will be important for determining whether or not restoration is useful for climate change adaptation.

-

(6)

Assessments of the social and economic risks associated with climate change and water resources will be needed to evaluate whether and how to intervene in order to minimize the environmental and health consequences of excess Nr in US waters.

References

Aerts R, De Caluwe H (1999) Nitrogen deposition effects on carbon dioxide and methane emissions from temperate peatland soils. Oikos 84:44–54

Alexander RB, Smith RA, Schwarz G (2000) Effect of stream channel size on the delivery of nitrogen to the Gulf of Mexico. Nature 403:758–761

Alexander RB, Smith RA, Schwarz GE, Boyer EW, Nolan JV, Brakebill JW (2008) Differences in phosphorus and nitrogen delivery to the Gulf of Mexico from the Mississippi River Basin. Environ Sci Technol 42:822–830

Alexander RB, Böhlke JK, Boyer EW et al (2009) Dynamic modeling of nitrogen losses in river networks unravels the coupled effects of hydrological and biogeochemical processes. Biogeochemistry 93:91–116

Bakun AD, Field D, Redondo-Rodriguez A, Weeks SJ (2010) Greenhouse gas, upwelling-favorable winds, and the future of coastal ocean upwelling ecosystems. Glob Change Biol 16:1213–1228

Bange HW, Rapsomanikis S, Andreae MO (1996) Nitrous oxide in coastal waters. Glob Biogeochem Cycle 10:197

Bange HW, Freing A, Kock A, Loscher C (2010) Marine pathways to nitrous oxide. In: Smith K (ed) Nitrous oxide and climate change. Earthscan, New York, pp 36–54

Baron JS, Schmidt TM, Hartman MD (2009) Climate-induced changes in high elevation stream nitrate dynamics. Glob Change Biol 15:1777–1789

Baron JS, Driscoll CT, Stoddard JL, Richer EE (2011) Empirical critical loads of atmospheric nitrogen deposition for nutrient enrichment and acidification of sensitive US lakes. BioScience 61:602–613

Bastviken D, Tranvik LJ, Downing JA, Crill PM, Enrich-Prast A (2011) Freshwater methane emissions offset the continental carbon sink. Science 331:50

Beaulieu JJ, Shuster WD, Rebholz JA (2010) Nitrous oxide emissions from a large, impounded river: the Ohio River. Environ Sci Technol 44:7527–7533

Beaulieu JJ, Tank JL, Hamilton SK et al (2011) Nitrous oxide emission from denitrification in stream and river networks. Proc Nat Acad Sci 108:214–219

Beman JM, Chow C-E, King AL et al (2011) Global declines in oceanic nitrification rates as a consequence of ocean acidification. Proc Nat Acad Sci 108:208–213

Bender MA, Knutson TR, Tuleya RE, Sirutis JJ, Vecchi GA, Garner ST, Held IM (2010) Modeled impacts of anthropogenic warming on the frequency of intense Atlantic hurricanes. Science 327:454–458

Benstead JP, Rosemond AD, Cross WF et al (2009) Nutrient enrichment alters storage and fluxes of detritus in a headwater stream ecosystem. Ecology 90:2556–2566

Bernhardt ES, Band LA, Walsh C, Berke P (2008) Understanding, managing and minimizing urban impacts of surface water nitrogen loading. Annu Rev Conserv Environ 1134:61–96

Bernot MJ, Dodds WK (2005) Nitrogen retention, removal, and saturation in lotic ecosystems. Ecosystems 8:442–453

Bodelier PLE, Laanbroek HJ (2004) Nitrogen as a regulatory factor of methane oxidation in soils and sediments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 47:265–277

Böhlke JK, Verstraeten IM, Kraemer TF (2007) Effects of surface-water irrigation on the sources, fluxes, and residence times of water, nitrate, and uranium in an alluvial aquifer. Appl Geochem 22:152–174

Boyer EW, Howarth RW (2008) Nitrogen fluxes from rivers to the coastal oceans. In: Capone DG, Bronk DA, Mulholland MR, Carpenter EJ (eds) Nitrogen in the Marine Environment, 2nd edn. Elsevier, Boston, pp 1565–1587

Boyer EW, Alexander RB, Parton WJ et al (2006) Modeling denitrification in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems at regional scales. Ecol Appl 16:2123–2142

Breitburg DL, Hondorp DW, Davias LA, Diaz RJ (2009) Hypoxia, nitrogen, and fisheries: integrating effects across local and global landscapes. Annu Rev Mar Sci 1:329–349

Bricker S, Longstaff B, Dennison W, Jones A, Boicourt K, Wicks C, Woerner J (2007) Effects of nutrient enrichment in the nation’s estuaries: a decade of change. NOAA Coastal Ocean Program Decision Analysis Series No. 26. National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, Silver Spring, MD

Brown CA, Power JH (2011) Historic and recent patterns of dissolved oxygen in the Yaquina Estuary (Oregon, USA): importance of anthropogenic activities and oceanic conditions. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 92:446–455

Brown JB, Sprague LA, Dupree JA (2011) Nutrient sources and transport in the Missouri River Basin, with emphasis on the effects of irrigation and reservoirs. J Am Water Resour Assoc 47:1034–1060

Burns DA, Blett T, Haeuber R, Pardo LH (2008) Critical loads as a policy tool for protecting ecosystems from the effects of air pollutants. Front Ecol Environ 6:156–159

Butman D, Raymond PA (2011) Significant efflux of carbon dioxide from streams and rivers in the United States. Nat Geosci 4:839–842

Campbell DH, Kendall C, Chang CCY, Silva SR, Tonnessen KA (2002) Pathways for nitrate release from an alpine watershed: determination using δ 15N and δ 18O. Water Resour Res 38:1052–1062

Caraco NF, Cole JJ (1999) Human impact on nitrate export: an analysis using major world rivers. Ambio 28:167–170

Codispoti LA (2010) Oceans. Interesting times for marine N2O. Science 327:1339–1340

Cole JJ, Prairie YT, Caraco NF et al (2007) Plumbing the global carbon cycle: integrating inland waters into the terrestrial carbon budget. Ecosystems 10:171–184

Compton JE, Harrison JA, Dennis RL et al (2011) Ecosystem services altered by human changes in the nitrogen cycle: a new perspective for US decision making. Ecol Lett 14:804–815

Craig LS, Palmer MA, Richardson DC et al (2008) Stream restoration strategies for reducing river nitrogen loads. Front Ecol Environ 6:529–538

Davidson EA, Savage KE, Bettez ND, Marino R, Howarth RW (2010) Nitrogen in runoff from residential roads in a coastal area. Water Air Soil Pollut 210:3–13

Deutsch C, Brix H, Ito T, Frenzel H, Thompson L (2011) Climate-forced variability of ocean hypoxia. Science 333:336–339

Díaz RJ, Rosenberg R (2011) Introduction to Environmental and Economic Consequences of Hypoxia. Int J Water Resour Dev 27:71–82

Dodds WK, Bouska WW, Eitzmann JL, Pilger TJ, Pitts KL, Riley AJ, Schloesser JT (2009) Eutrophication of U.S. freshwaters: analysis of potential economic damages. Environ Sci Technol 43:12–19

Doney SC, Fabry VJ, Feely RA, Kleypas JA (2009) Ocean acidification: the other CO2 problem. Annu Rev Mar Sci 1:169–191

Downing JA, Cole JJ, Middelburg JJ et al (2008) Sediment organic carbon burial in agriculturally eutrophic impoundments over the last century. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 22:GB1018. doi:10.1029/2006GB002854

Doyle MW, Stanley EH, Havlick DG et al (2008) Environmental science—aging infrastructure and ecosystem restoration. Science 319:286–287

Dubrovsky NM, Burow KR, Clark GM et al (2010) The quality of our Nation’s waters—nutrients in the Nation’s streams and groundwater, 1992–2004: U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1350

Duc NT, Crill P, Bastviken D (2010) Implications of temperature and sediment characteristics on methane formation and oxidation in lake sediments. Biogeochemistry 100:185–196

Duce RA, LaRoche J, Altieri K, Arrigo KR, Baker AR, Capone DG, Cornell S (2008) Impacts of atmospheric anthropogenic nitrogen on the open ocean. Science 320:893–897

Dumont E, Harrison JA, Kroeze C, Bakker EJ, Seitzinger S (2005) Global distribution and sources of dissolved inorganic nitrogen export to the coastal zone: results from a spatially explicit, global model. Global Biogeochem Cycles 19:GB4S02. doi:10.1029/2005GB002488

Elser JJ, Urabe J (1999) The stoichiometry of consumer-driven nutrient recycling: theory, observations, and consequences. Ecology 80:745–751

Elser JJ, Andersen T, Baron JS, Bergström A-K, Jansson M, Kyle M, Nydick KR (2009) Shifts in lake N:P stoichiometry and nutrient limitation driven by atmospheric nitrogen deposition. Science 326:835–837

Exner ME, Perea-Estrada H, Spalding RF (2010) Long-term response of groundwater nitrate concentrations to management regulations in Nebraska’s central Platte valley. Sci World J 10:286–297

Feely RA, Doney SC, Cooley SR (2009) Ocean acidification: present conditions and future changes in a high-CO2 world. Oceanography 22:36–47

Finlay JC, Sterner RW, Kumar S (2007) Isotopic evidence for in-lake production of accumulating nitrate in Lake Superior. Ecol Appl 17:2323–2332

Fletcher SE (2004) CH4 sources estimated from atmospheric observations of CH4 and its 13C/12C isotopic ratios: 1. Inverse modeling of source processes. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 18:1–17

Frölicher TL, Joos F, Plattner G-K, Steinacher M, Doney SC (2009) Natural variability and anthropogenic trends in oceanic oxygen in a coupled carbon cycle climate model ensemble. Globl Biogeochem Cycles 23:GB1003. doi:10.1029/2008GB003316

Gage KL, Burkot TR, Eisen RJ, Hayes EB (2008) Climate and vector-borne diseases. Am J Prev Med 35:436–450

Galloway JN, Aber JD, Erisman JW, Seitzinger SP, Howarth RH, Cowling EB, Cosby BJ (2003) The nitrogen cascade. BioScience 53:341–356

Galloway JN, Burke M, Bradford GE et al (2007) International trade in meat: the tip of the pork chop. Ambio 36:622–629

Gleick PH (2003) Water use. Annu Rev Environ Resour 28:275–314

Grantham B, Chan F, Nielsen KJ et al (2004) Upwelling-driven nearshore hypoxia signals ecosystem and oceanographic changes in the northeast Pacific. Nature 429:749–754

Greaver TL, Sullivan T, Herrick JD et al (2012) Ecological effects from nitrogen and sulfur air pollution in the United States: what do we know? Front Ecol Environ. doi:http://10.1890/110049

Gudasz C, Bastviken D, Steger K, Premke K, Sobek S, Tranvik L (2010) Temperature-controlled organic carbon mineralization in lake sediments. Nature 466:478–481

Gurdak JJ, Hanson RT, McMahon PB, Bruce BW, McCray JE, Thyne GD, Reedy RC (2007) Climate variability controls on unsaturated water and chemical movement, High Plains Aquifer, USA. Vadose Zone J 6:533–547

Harrison JA, Maranger RJ, Alexander RB et al (2009) The regional and global significance of nitrogen removal in lakes and reservoirs. Biogeochemistry 93:143–157

Heisler J, Glibert PM, Burkholder JM et al (2008) Eutrophication and harmful algal blooms: a scientific consensus. Harmful Algae 8:3–13

Hoagland P, Anderson DM, Kaoru Y, White AW (2002) The economic effects of harmful algal blooms in the United States: estimates, assessment issues, and information needs. Estuaries 25:819–837

Hobbs WO, Telford RJ, Birks HJB et al (2010) Quantifying recent ecological changes in remote lakes of North America and Greenland using sediment diatom assemblages. PloS one 5:e10026. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010026

Hofmann M, Schellnhuber H (2009) Oceanic acidification affects marine carbon pump and triggers extended marine oxygen holes. Proc Nat Acad Sci 106:3017–3022

Hong B, Swaney D, Howarth RW (2011) A toolbox for calculating net anthropogenic nitrogen inputs (NANI). Environ Model Softw 26:623–633

Houlton BZ, Boyer E, Finzi A, Galloway J, Leach A, Liptzin D, Melillo J, Rosenstock TS, Sobota D, Townsend AR (2012) Intentional versus unintentional nitrogen use in the United States: trends, efficiency and implications. Biogeochemistry. doi:10.1007/s10533-012-9801-5

Howarth RW (1998) An assessment of human influences on inputs of nitrogen to the estuaries and continental shelves of the North Atlantic Ocean. Nutr Cycling Agroecosyst 52:213–223

Howarth RW, Billen G, Swaney D et al (1996) Riverine inputs of nitrogen to the North Atlantic Ocean: fluxes and human influences. Biogeochemistry 35:75–139

Howarth RW, Boyer EW, Marino R, Swaney D, Jaworski N, Goodale C (2006) The influence of climate on average nitrogen export from large watersheds in the northeastern United States. Biogeochemistry 79:163–186

Howarth RW, Chan F, Conley DJ, Garnier J, Doney SC, Marino R, Billen G (2011a) Coupled biogeochemical cycles: eutrophication and hypoxia in temperate estuaries and coastal marine ecosystems. Front Ecol Environ 9:18–26

Howarth RW, Swaney D, Billen G et al (2011b) Nitrogen fluxes from the landscape are controlled by net anthropogenic nitrogen inputs and by climate. Front Ecol Environ 110715073159005. doi:10.1890/100178

Howden NJK, Burt TP, Worrall F, Whelan MJ, Bieroza M (2010) Nitrate concentrations and fluxes in the River Thames over 140 years (1868–2008): are increases irreversible? Hydrol Proc 24:2657–2662

IPCC (2007) Climate Change 2007: the physical science basis. In: Solomon S, Qin D, Manning M, Chen Z, Marquis M, Avery KB, Tignor M, Miller HL (eds) Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2007. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 1–996

Johnson PTJ, Townsend AR, Cleveland CC et al (2010) Linking environmental nutrient enrichment and disease emergence in humans and wildlife. Ecol Appl 20:16–29

Jordan SJ, Stoffer J, Nestlerode JA (2011) Wetlands as sinks for reactive nitrogen at continental and global scales: a meta-analysis. Ecosystems 4:144–155

Kampschreur MJ, Temmink H, Kleerebezem R, Jetten MSM, van Loosdrecht MCM (2009) Nitrous oxide emission during wastewater treatment. Water Res 43:4093–4103

Karl TR, Melillo JM (2009) Global climate change impacts in the United States. US Global Change Research Program. Cambridge University Press, New York

Kastowski M, Hinderer M, Vecsei A (2011) Long-term carbon burial in European lakes: analysis and estimate. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 25:GB3019

Kaushal SS, Binford MW (1999) Relationship between C:N ratios of lake sediments, organic matter sources, and historical deforestation in Lake Pleasant, Massachusetts, USA. J Paleolimnol 22:439–442

Keeling R, Kortzinger A, Gruber N (2010) Ocean deoxygenation in a warming world. Annu Rev Mar Sci 2:199–229

Keller M, Varner R, Dias JD, Silva H, Crill P, de Oliveira RC, Asner GP (2005) Soil–atmosphere exchange of nitrous oxide, nitric oxide, methane, and carbon dioxide in logged and undisturbed forest in the Tapajos National Forest, Brazil. Earth Interact 9:1–28

Kim T-W, Lee K, Najjar RG, Jeong H-D, Jeong HJ (2011) Increasing N abundance in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean due to atmospheric nitrogen deposition. Science 334:505–509

Kirshen P, Ruth M, Anderson W (2007) Interdependencies of urban climate change impacts and adaptation strategies: a case study of Metropolitan Boston USA. Clim Change 86:105–122

Kling GW, Hayhoe K, Johnson L et al. (2003) Confronting climate change in the Great Lakes Region. Union of Concerned Scientists, Ecological Society of America; Cambridge, MA, Washington, D.C

Kroeze C, Dumont E, Seitzinger SP (2005) New estimates of global emissions of N2O from rivers and estuaries. Environ Sci 2:159–165

Kroeze C, Dumont E, Seitzinger S (2010) Future trends in emissions of N2O from rivers and estuaries. J Integr Environ. Sci 7:71–78