Abstract

We investigate the impact of cross-border acquisition activity on the domestic productivity of Chinese multinationals. Chinese MNEs have engaged in cross-border acquisitions in an attempt to explore for new capabilities, technologies and management practices so as to enhance productivity and compete in increasingly competitive domestic markets. Empirical scholarship, however, has yet to establish that cross-border acquisition activity by emerging-market multinationals generally contributes to domestic-productivity upgrading, as learning from foreign-acquisition targets, transferring and assimilating this learning, and ultimately upgrading the productivity of home operations represents a challenging and complicated process. We accordingly apply and advance the literature on reverse-knowledge transfers and capability upgrading by first considering the relevance of cross-border acquisition activities on domestic productivity in an emerging-market context, and by second extending the literature’s understanding of the target-firm characteristics which abet domestic-productivity upgrading. Employing firm-level panel data based on 329 Chinese multinationals over the 2000–2010 period, we find outward cross-border acquisition activities generate increased domestic productivity. In addition, we find domestic-productivity upgrading to be larger when acquiring high-tech (versus low-tech) targets and that this effect is further enhanced when acquiring related (versus unrelated) targets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

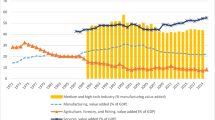

During the past two decades, China has liberalized its economic policies and taken a more outward-looking approach; as a result, Chinese multinational enterprises (MNEs) have rapidly internationalized and actively engaged in outward foreign direct investment (Hoskisson, Eden, Lau, & Wright, 2000; Narula & Dunning, 2000; Li, Li, Lyles, & Liu, 2016). Scholars have pointed out that one important rationale behind China’s rapid internationalization is the need to learn from international experiences and develop global competitiveness (Hitt, Li, & Worthington, 2005, Hitt, Li, & Xu, 2016; Luo & Tung, 2007, Luo & Tung, 2018; Ramamurti, 2008; Li et al., 2016; Jiang, Jiao, Lin, & Xia, 2019; Chen et al., 2019). In fact, the Chinese central government established the ‘Go Global’ policy in 1999 to spur mainland firms to invest in overseas operations (Buckley, Clegg, Cross, Liu, Voss, & Zheng, 2007). Specifically, government controls over outward foreign direct investment (FDI) were loosened and preferential treatments such as direct grants, tax benefits, low- or no-interest loans and access to foreign exchange were provided to Chinese MNEs investing abroad (Gu & Reed, 2013). The ultimate aim of these policies was to encourage Chinese multinationals to learn from these international experiences and acquire the advanced technologies, knowledge and management skills that translate into enhanced domestic productivities (Hitt et al., 2005, Hitt et al., 2016). Lenovo potentially represents the paragon of such efforts according to McKinsey (2017), as it has demonstrated a deep commitment to substantially better its domestic-operating procedures in fully taking advantage of its cross-border acquisitions (e.g., IBM’s PC business, the US software company Stoneware, and Germany’s Medion).

Hitt et al. (2016) observe a shifting focus in the MNE literature from multinationals that exploit parent ownership advantages to a global business landscape where multinationals explore for new capabilities in host countries. Within this shifting research focus, a number of observers (e.g., Uhlenbruck, Meyer, & Hitt, 2003; Hitt et al., 2005; Mathews, 2006; Luo & Tung, 2007, Luo & Tung, 2018; Kumar, Singh, Purkayastha, Popli, & Gaur, 2020) have considered the cross-border investment activities undertaken by Chinese and other emerging-market multinationals to be largely driven by the need to engage in exploratory learning so as to upgrade domestic productivities and capabilities in order to effectively compete against both foreign and domestic rivals in increasingly-contested home markets. Indeed, Li et al. (2016) find evidence that Chinese provinces with higher levels of outward FDI are generally characterized by greater provincial-level productivity. Moreover, cross-border acquisitions have arguably become the preferred vehicle for outward FDI undertaken by emerging-market MNEs (Sauvant, Maschek, & McAllister, 2009). Acquisitions can be an efficient instrument for enhancing firm competitiveness as they present learning opportunities where reverse-knowledge transfers can occur that achieve efficiencies (Greenberg, Lane, & Bahde, 2005; Maucher, 1998; Kumar et al., 2020; Scalera, Mukherjee, & Piscitello, 2020). In this vein, Bertrand and Capron (2015) find that French firms engaging in outward cross-border acquisitions learn from such experiences and consequently upgrade domestic productivity. Closer to our empirical context, Luo and Tung (2007) and Mathews (2006) report that the cross-border acquisition activities by Chinese multinationals have been aimed at exploration where reverse-knowledge transfers drive the transactions.

Despite the importance of this issue, Hitt et al. (2005) delineate a gap in the extant literature – “there is relatively little research on learning behaviors by local emerging market firms” (p. 354) – that persists. Specifically, it is widely understood that cross-border acquisitions are undertaken by emerging-market MNEs with the ambition to obtain strategic assets that enable effectively competing against established MNEs in both domestic and global markets (e.g., Luo & Tung, 2018), yet whether such internationalization is generally successful is less well known. As Kumar et al. (2020: 173) make clear, cross-border acquisitions “facilitate rapid resource augmentation for the acquiring firms … yet it is also a risky entry mode that … has inherently uncertain performance effects”. Li et al. (2016) begin to fill this gap apart from their empirical analysis residing at the provincial-level: where they consider the impact of Chinese outward FDI on productivity growth in home provinces. The Bertrand and Capron (2015) study is certainly fundamental in that it establishes that cross-border acquisition activity leads to the upgrading of firm-level domestic productivities in the French context. That said, Bertrand and Capron (2015: 654) call for additional scholarship when stating that “our results should be further tested by replicating this study in different institutional and economic contexts”. Indeed, the transfer and assimilation of knowledge – essential for a successful learning experience – may not consistently manifest for Chinese multinationals due to the disadvantages of these firms in terms of advanced knowledge and management practices (e.g., Heckman, 2005; Bloom & Van Reenen, 2010; McKinsey, 2017; Kumar et al., 2020) and due to the complexities involved with cross-border business activities (e.g., Hitt, Harrison, & Ireland, 2001). Establishing strong causal inferences between cross-border acquisition activity and domestic-productivity upgrading at the firm level in the emerging-market context represents then a micro-foundational empirical challenge that has not been fixed in the literature to the best of our knowledge.

With the above literature gap as a backdrop, our principal research question involves examining whether Chinese multinationals engaging in higher levels of cross-border acquisition activity are generally able to learn from these experiences in a manner that yields domestic-productivity upgrading in home operations. While the impact on domestic productivity of the cross-border acquisition activities undertaken by Chinese multinationals represents the core of our investigation, we also consider some of the target-firm conditions that elucidate how Chinese multinationals use cross-border acquisitions to upgrade their domestic capabilities and productivities. Specifically, we follow up upon Bertrand and Capron’s (2015) observations that learning opportunities and the institutional context are material for the study of knowledge transfer. In line with the relevance of learning opportunities, we examine whether the cross-border acquisitions of high-tech target firms yield greater domestic-productivity upgrading as compared to the cross-border acquisitions of low-tech target firms. And in line with the relevance of the institutional environment for knowledge transfer, we examine whether the relatedness of target firms (i.e., related versus unrelated acquisitions) enhances the domestic-productivity upgrading from high-tech acquisitions.

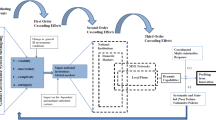

In order to conceptually ground our contribution regarding cross-border acquisition activities and the consequent domestic-productivity upgrading that allows Chinese multinationals to effectively compete in increasingly contentious markets, our theoretical priors draw from the expanding literature on explorative learning, capability upgrading and reverse-knowledge transfers in multinationals (Hitt et al., 2005, Hitt et al., 2016; Mathews, 2006; Luo & Tung, 2007, Luo & Tung, 2018; Bertrand & Capron, 2015; Li et al., 2016). Building on these conceptual foundations, we examine whether Chinese multinationals successfully learn from cross-border acquisition experiences by upgrading the productivity of their home operations in the years subsequent to acquisition activities. We contend that Chinese multinationals are able to assimilate the learning from foreign acquisitions so as to ultimately upgrade their domestic productivities. Cross-border acquisitions consequently represent vehicles for Chinese multinationals to externally obtain and assimilate technologies, managerial practices, and knowledge-based resources which could not otherwise be developed internally (Barkema & Vermeulen, 1998; Hitt et al., 2005; Li, 2010; Kumar et al., 2020). In addition to these conceptual foundations, we also extend the seminal Bertrand and Capron (2015) study by first following their observation that domestic-productivity gains should be larger when the relevant knowledge gaps and learning opportunities are greater. We expand upon this intuitive observation regarding the material importance of the present learning opportunities by generating an additional theoretical prior regarding the extent of domestic-productivity upgrading when target firms are based in high-tech versus low-tech sector contexts. Furthermore, we expand upon Bertrand and Capron’s (2015) complementary observation that a conducive institutional environment is also required for successful knowledge transfer by considering how related acquisitions of high-tech targets can be superior to unrelated acquisitions of high-tech targets in achieving domestic-productivity upgrading.

We compile a firm-level panel data set consisting of 329 Chinese multinationals over the 2000–2010 period to empirically test our three hypotheses. Specifically, we consider the impact of cross-border acquisition activity on the total factor productivity (TFP) of the domestic operations for our sampled Chinese MNEs. While cross-border acquisition activity represents the explanatory variable of principal interest, we are able to control for alternative investment activities which might also impact domestic TFP; i.e., domestic-acquisition activity, international-alliance activity, domestic-alliance activity, and innovative-patent activity. We also include a number of additional control constructs in our regression estimations, and it is worth highlighting that we follow the prescriptions of Bertrand and Capron (2015) to control for target-firm characteristics. Our estimations also fully take advantage of the panel nature of the data by including firm-specific and year-specific fixed effects, thus we strictly employ between-variation when estimating the parameters of our regression models (Wooldridge, 2002).

Overall, this study makes three main contributions. Our first – and principal – contribution involves establishing that Chinese multinationals engaging in higher levels of cross-border acquisition activity experience increased domestic-productivity upgrading. Thus, Chinese MNEs generally appear to be able to identify and codify the superior technologies and managerial practices in foreign targets, transfer that knowledge to the home country, and assimilate that knowledge in such a manner so as to enhance the productivity of domestic operations. While the relationship between firm-level cross-border acquisition activity and domestic-productivity upgrading has been established in the developed-market context (i.e., Bertrand & Capron, 2015), the literature on reverse-knowledge transfers and capability upgrading has yet to yield empirical support for this relationship in the emerging-market context. We are also able to contextualize this principal contribution via two additional theoretical and empirical contributions by building upon and extending the seminal Bertrand and Capron (2015) study. First, we establish that this upgrading in home productivity stems from acquiring high-tech targets and not low-tech targets. Second, we establish that this upgrading in home productivity from acquiring high-tech targets will be further enhanced when target firms are related to the acquiring firm.

Background literature

The acquisition process consists of many interdependent sub-activities each of which is complex in itself nevertheless in combination (Hitt et al., 2001). Cross-border acquisition activity that generates domestic-productivity upgrading involves, moreover, a number of additional challenges and complications; i.e. overcoming liabilities of foreignness, emergingness and origin (Kumar et al., 2020); selecting host-country targets that involve the requisite complementarities and learning opportunities (Hitt et al., 2001; Bertrand & Capron, 2015); identifying and codifying the unique target-firm technologies and practices (Kogut & Zander, 1993); and transferring and applying such knowledge to home-country operations in a manner that enhances domestic productivity (Martin & Salomon, 2003). Therefore, it is not a priori evident that Chinese multinationals will be generally able to successfully learn from outward cross-border acquisition activities in such a way that it ultimately leads to enhanced domestic productivity.

Hitt et al. (2005) point out the necessary presence of three conditions for the reverse-knowledge transfer process to be ultimately successful. Specifically, (1) the learning firms must be incentivized to learn and upgrade; (2) the learning firms must have sufficient absorptive capacity; and (3) the learning firms must engage in integration practices that are conducive to such absorption and learning. In reviewing the relevant background literature on reverse-knowledge transfer and capability upgrading in the emerging-market context, we consider whether these three conditions are applicable for Chinese multinationals engaging in cross-border acquisition activities. Taking such an approach to the literature review helps establish the plausibility of our theoretical conjectures regarding the manifestation of domestic-productivity upgrading subsequent to outward cross-border acquisition activities.

First, it has been well recognized that Chinese multinationals face substantial incentives to acquire new technologies and knowledge that can be converted into effective capabilities (e.g., Hitt et al., 2005). China has become an increasingly attractive location for developed-market MNEs to expand their market territory. In particular, many global MNEs have entered China over the last few decades to set up production facilities, form alliances with Chinese firms, and compete in local markets. Yet the competitive advantages of global MNEs in terms of product quality, production technology and managerial expertise threaten the survival of indigenous Chinese firms due to their weak firm-specific advantages (Uhlenbruck et al., 2003; Rugman, 2010; Kumar et al., 2020). Morck et al. (2008) highlight how rising capacity and intensifying price competition – brought on by these foreign entries – have led to lower profit margins for Chinese firms. Furthermore, rapid changes in technology and the market landscape yield little time for emerging-market firms to develop organically or internationalize incrementally. Chinese MNEs must develop firm-specific advantages rapidly if they desire to be competitive in their domestic market nevertheless global markets (Uhlenbruck et al., 2003; Mathews, 2006; Kumar et al., 2020). In this vein, Aghion et al. (2004) clarify how entries by highly-efficient multinationals can enhance the incentive for local firms to engage in capability-building investments. Consequently, Chinese MNEs have been pushed to quickly internationalize and seek foreign practices and technologies in order to develop capabilities due to the competitive pressures brought on by developed-market MNEs having entered the Chinese market over the last two decades (e.g., Sauvant et al., 2009).

Second, engaging in cross-border acquisition activity certainly exposes firms to new technologies and managerial practices; yet, Chinese multinationals must have sufficient knowledge and abilities to absorb new sets of technologies and practices (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). A number of recent studies (e.g., Görg & Strobl, 2005; Blake, Deng, & Falvey, 2009; Poole, 2013) have found support for the ability of emerging-market firms to ‘broadly’ learn from different experiences via spillover effects; thus, it has become well accepted that emerging-market firms have substantially raised their absorptive-capacity levels over the last two decades. More specifically, Hoskisson et al. (2004) argue that Chinese MNEs – as well as firms based in the other BRICs nations – stand out amongst the emerging-market MNEs as the firms best able to learn from foreign experiences. As observed by Hitt et al. (2005), the relative stability of the Chinese environment supports firm-specific investments with respect to learning the skills and capabilities that sustain long-term competitiveness. Scholars generally credit the large amounts of inward FDI experienced by China over the last few decades as providing indigenous firms with the necessary prior knowledge to develop sufficient absorptive capacity (Penner-Hahn & Shaver, 2005; Song & Shin, 2008). The substantial amount of inward FDI experienced by China has led then to a considerable accumulation of financial, operational and technological assets on the part of indigenous firms. Consequently, Chinese firms are now seemingly characterized by the technological and managerial skills which indicate a ‘general’ ability to absorb and assimilate the unique learning opportunities present in foreign acquisitions (Young, Huang, & McDermott, 1996).

Third, the appropriate integration between the emerging-market multinational and the foreign target represents a critical factor in ensuring that learning and upgrading take place subsequent to cross-border acquisition activities. Indeed, the challenges involved with integrating firms are largely credited with being responsible for the vast majority of acquisition failures (e.g., Hitt et al., 2001). If Chinese multinationals generally employed integration practices that led to alienated target firms where key employees departed in large numbers, then it would be difficult to use these acquisitions as learning vehicles – after all, one certainly can’t learn from departed employees. Chinese MNEs do, however, tend to engage in smooth integrations with target firms, as they exhibit practices that are different than those practiced by developed-market acquirers (Kumar, 2009; McKinsey, 2017). Unlike developed-market multinationals, Chinese acquirers tend to depart from the conventional practice to exert control by extensively employing their own managers as expatriates when resource commitments increase (Hennart, 1989) and when more risky entry modes are undertaken (Hill et al., 1990). Instead, Chinese – and other emerging-market multinationals – tend to preserve the top-management teams and organizational structures of target firms in the post-transaction environment (Luo & Tung, 2007; Kumar, 2009; McKinsey, 2017). This retaining of target-firm managers is a virtual prerequisite if multinationals desire to substantially learn from target firms (Hambrick & Cannella, 1993).

Given the presence of these necessary conditions – sufficient learning incentive, adequate absorptive capacity, and appropriate integration practices – outlined by Hitt et al. (2005), the reverse-knowledge transfer process may sizably manifest in the context of China. It is accordingly plausible that the cross-border acquisitions undertaken by Chinese multinationals represent an instrument that has contributed to increased domestic productivity and overall economic growth in this emerging market. As an aside, such dynamics are not exclusive to China, as the rise of Indian multinationals has also been driven by the need to engage in cross-border investments that seek technologies and knowledge (Taylor & Nölke, 2010; Kumar et al., 2020).

While TFP analysis is a superior means to empirically capture a multinational’s domestic productivity, we should also testify to how productivity analysis represents an effective barometer of successful learning and capability upgrading. Balasubramanian (2011), for instance, holds that TFP represents the most natural measure of learning from organizational experiences since experiences are ultimately aimed at improving the firm’s ability to turn inputs into outputs. Yet beyond this support, the TFP approach to capturing successful learning and upgrading from various investment experiences follows the specific approaches employed by Bertrand and Capron (2015) and Li et al. (2016). Indeed, Bertrand and Capron (2015) employ domestic productivity as a barometer of learning from cross-border experiences in their study of French cross-border acquisition activity. Furthermore, the Li et al. (2016) study of outward FDI by Chinese multinationals also uses provincial-level TFP to capture the direct and indirect learning effects from investing abroad and searching for advanced technologies and knowledge.

The TFP approach to capturing learning and capability upgrading is also similar to the general measurement approach employed in the spillovers literature: where that literature holds that FDI involves a transfer of technology and ideas to a host nation (e.g., Liu, Siler, Wang, & Wei, 2000; Wei & Liu, 2006). Spillovers are based on the idea that multinationals possess intangible assets such as technological know-how, management skills, export relationships, and brand awareness that purely domestic firms do not (Dunning, 1981). Moreover, MNEs are unable to fully prevent such advantages from spilling over to domestic firms; what McCann and Mudambi (2005) refer to as unintentional knowledge outflows. Moreover, empirical work generally captures these knowledge spillovers via the productivity changes experienced by outsider firms, though a few studies consider worker wages as an alternative barometer of upgrading (e.g., Clougherty, Gugler, Sørgard, & Szücs, 2014). Thus, the TFP approach to capturing learning and capability upgrading from cross-border experiences is well established in the empirical literature as it conforms to the approach employed in studies of learning from cross-border experiences (e.g., Bertrand & Capron, 2015; Li et al., 2016) and to the approach employed in the spillovers literature where FDI generates successful knowledge transfer to indigenous firms (e.g., Liu et al., 2000; Wei & Liu, 2006). Within this need to accumulate foreign experiences in order to upgrade domestic capabilities and productivities, we now turn to generating our theoretical priors by outlining the specific mechanisms that initiate domestic-productivity upgrading.

Hypothesis development

Multinationals generally specialize in the creation and internal transfer of knowledge (Kogut & Zander, 1993). Firm-specific advantages are developed and diffused within an MNE’s network to take advantage of the complex interdependencies between actors in different locations (Dunning, 1958; Hymer, 1976). Thus, knowledge and capabilities within MNEs are transferred and disseminated from the center of excellence – i.e., the organizational unit that embodies a set of capabilities recognized by the firm as an important value-creation source – to other parts of the MNE (Frost, Birkinshaw, & Ensign, 2002). This ability to create and transfer knowledge is perceived as a key competitive advantage of multinationals (Andersson, Forsgren, & Holm, 2001). Although the initial costs of Chinese cross-border acquisition activity may be relatively high, these multinationals can expand their knowledge base and improve overall competitiveness via these experiences (Vermeulen & Barkema, 2001; Mathews, 2006; Luo & Tung, 2007, Luo & Tung, 2018). Therefore, learning and knowledge transfer are likely to manifest in the domestic operations of these Chinese multinationals as a result of cross-border acquisition experiences.

Beyond the inherent learning nature of multinationals, it bears repeating that successfully engaging in cross-border acquisition activity that ultimately leads to domestic-productivity upgrading involves a number of inter-related tasks (Hitt et al., 2001, Hitt et al., 2005). First, the multinational must be able to overcome the liability of foreignness and select target firms in the host country with superior technologies and practices that present learning opportunities (Bertrand & Capron, 2015), but also involve the necessary complementarities with the multinational’s home operations (Hitt et al., 2001). Second, the multinational must be able to identify and codify the unique technologies and practices characteristic of the target firm (Kogut & Zander, 1993). Third, the multinational should be able to transfer and apply such knowledge to domestic operations in an efficient manner that yields commercial gains and enhanced domestic productivity (Martin & Salomon, 2003). Operationalizing these inter-related tasks allows for what could be referred to as a bottom-up learning mechanism – an ‘explorative learning’ where knowledge transfer occurs from the foreign-market target to the emerging-market multinational’s home operations (Hitt et al., 2005, Hitt et al., 2016). It should be noted that this bottom-up learning mechanism is not unique to cross-border acquisition activities, as Hitt et al. (2005) similarly focus on international alliances as a strategic-investment vehicle that leads to the advancement of emerging-market multinationals.

While the above testifies to a general mechanism via which bottom-up learning manifests via cross-border acquisition activities, we should also highlight the most direct mechanism via which emerging-market multinationals might gain advanced knowledge, practices and technologies from foreign targets. Specifically, cross-border acquisition activities entail ownership rights and the ability to place key executives in the acquired firms. When placing a handful of experienced managers in the acquired foreign firms, these managers manifest the authority and the ability as ultimate owners to transfer technologies and practices back to the parent’s domestic operations (Kumar, 2009; McKinsey, 2017). While such transfers will be more blueprint-like in nature (a top-down versus bottom-up approach to capability upgrading and learning), the combination of ownership and executive authority represents a powerful and effective means to execute the transfer of technologies and best practices to the domestic operations of Chinese multinationals. In fact, ‘The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States’ (CFIUS) has recently blocked a number of attempts by Chinese multinationals to acquire U.S. companies with sophisticated technologies so as to prevent the transfer of such technologies back to the Chinese parent (Baltz, 2017). Accordingly, ownership rights represent an essential mechanism in facilitating reverse-knowledge transfer in cross-border acquisition activities, as ownership yields the authority to command the transfer of strategic assets and technologies, which in turn enhances the productivity of the parent’s domestic operations.

These three mechanisms represent the conceptual foundations for generating our core theoretical hypothesis regarding the increased productivity of domestic operations subsequent to cross-border acquisition activities. First, multinationals involve an inherent learning nature where the transfer of knowledge between units is intrinsic to the MNE’s function (Kogut & Zander, 1993; Martin & Salomon, 2003). Second, given the presence of the necessary inter-related tasks and conditions, the potential exists for Chinese multinationals to successfully learn from cross-border acquisition activities via a bottom-up learning mechanism. Third, the ownership rights involved with cross-border acquisition activity yield a direct top-down mechanism for reverse-knowledge transfer as ownership provides the authority to command transfers of technologies and strategic assets to the parent firm’s domestic operations.Footnote 1 Via these three mechanisms, Chinese multinationals will be generally able to obtain, accumulate and leverage the technologies, know-how and best practices present in foreign-target firms in a manner that achieves domestic-productivity upgrading. Accordingly, our core theoretical contention can be set out as follows:

Hypothesis 1

Chinese multinationals engaging in higher levels of cross-border acquisition activity will experience greater domestic-productivity upgrading in subsequent years.

While considering the impact of cross-border acquisition activity on domestic-productivity upgrading in the Chinese context represents our core contribution, there exist some related questions of both theoretical and empirical interest that will help contextualize our core contribution. The seminal study by Bertrand and Capron (2015) makes two salient points with respect to the conditions that support the presence of substantial domestic-productivity benefits from engaging in cross-border acquisitions. First, the learning opportunities present in foreign targets are material when considering the degree to which multinationals can gain from cross-border acquisition activities; namely, domestic-productivity gains should be larger when the learning opportunities are greater. Second, the institutional environment must be conducive to knowledge transfer and redeployment; namely, fully taking advantage of these learning opportunities requires the presence of an appropriate organizational context for cross-border acquisitions where successful knowledge transfer from the foreign target to the home acquirer is secured and promoted. We accordingly expand upon Bertrand and Capron’s (2015) observations by generating two additional theoretical priors regarding the characteristics of target firms and the extent of domestic-productivity upgrading. In particular, we consider whether domestic-productivity upgrading is larger when acquiring high-tech targets as compared to low-tech targets, and whether domestic-productivity upgrading is larger when high-tech targets are also characterized by business overlap (i.e., relatedness) with the multinational.

High-tech versus low-tech targets

The technological nature of acquired firms represents a clear foreign-target characteristic that conceivably impacts the learning opportunities present for emerging-market MNEs engaging in cross-border acquisition activities. Indeed, Bertrand and Capron (2015) observe that greater learning opportunities lead to larger domestic-productivity upgrading effects. Most obviously, high-tech firms tend to engage in greater research and development (R&D) spending as compared to low-tech firms; moreover, R&D is widely acknowledged as positively contributing to firm productivity (e.g., Griliches, 1979, Griliches, 1986; Mairesse & Sassenou, 1991; Hall & Mairesse, 1995; Hall, Mairesse, & Mohnen, 2010). Accordingly, high-tech target firms will tend to be relatively-productive firms with advanced technologies that present substantial learning opportunities for Chinese multinationals. Beyond the fact that cross-border acquisitions of high-tech targets provide direct access to enhanced learning opportunities via pre-existing investments in R&D and productivity, three additional mechanisms indicate that Chinese multinationals engaging in cross-border acquisitions of high-tech firms will be able to realize substantial domestic-productivity effects as compared to cross-border acquisitions of low-tech firms.

First, high-tech firms engage in higher levels of basic research as compared to low-tech firms; and it is basic research which generally leads to the complex and radical innovations that generate competitive advantages and larger learning opportunities (Nelson, 1959). Indeed, the propensity to conduct basic research increases for high-tech firms; e.g., firms residing in the pharmaceuticals, chemicals, computers, and electrical equipment sectors (Link, 1981). Furthermore, basic research leads to innovations that are often costly to develop, hard to imitate, and difficult to appropriate; by contrast, innovations by low-tech firms (which often reside in the manufacturing and traditional service sectors) tend to be more infrequent and incremental in nature (Andries, Bruylant, Czarnitzki, Hoskens, Thorwarth, & Wastyn, 2009). In this vein, Porter (1990) identifies that national competitive advantage derives from factors that are advanced, specialized, and tied to specific industries or industry groups. Since high-tech firms rely heavily on basic research – which often involves complexity, large R&D investments, and innovations of a radical nature – high-tech targets will generally manifest substantial learning opportunities for emerging-market multinationals. As such, high-tech target firms and their sizable investments in basic research augment for Chinese multinationals the potential for reverse-knowledge transfer and capability upgrading via cross-border acquisition activities.

Second, high-tech firms tend to generate conditions favoring the appropriation of knowledge, while the knowledge and technologies embedded in low-tech firms is generally more easily imitated by rival firms. Early research (e.g., Nelson, 1959; Arrow, 1962) stressed that knowledge, once produced, has the characteristic of a public good, as it can readily spillover from the innovating firm to rival firms. Such spillovers allow free riding on the efforts of innovating firms and reduce the innovator’s ability to fully appropriate the economic returns from these activities. Yet importantly, Trajtenberg et al. (1992) point out that basic research (which high-tech firms engage in more so than low-tech firms) tends to be riskier in nature and characterized by longer lead times; however, the riskier nature and longer duration of basic research involves a corresponding higher ability to appropriate knowledge. Therefore, high-tech firms are likely to appropriate a larger fraction of the benefits from their investments in basic research, while low-tech firms are likely to appropriate a lower fraction of the benefits from their investments in more-applied research. It is for this reason that scholars (e.g., Griliches & Mairesse, 1984; Nadiri, 1993) often observe larger innovation returns in high-tech sectors than in low-tech sectors. In our context, this suggests that cross-border acquisition activities aimed at high-tech targets will not only involve greater learning opportunities as compared to low-tech targets, but also involve higher ratios of appropriability. Put succinctly, Chinese multinationals engaging in cross-border acquisitions will not only have access to the greater pools of knowledge embedded in high-tech targets, but will also be able to appropriate a higher percentage of this knowledge when compared with acquiring low-tech targets. The higher appropriability ratio that is relevant when acquiring high-tech targets suggests then that acquiring such targets will further enhance the reverse-knowledge transfer process and further upgrade the productivity of home operations.

Third, high-tech firms are not only characterized by the advanced nature of their core technologies, but also by advanced knowledge and practices throughout the various functions of the firm (Milgrom & Roberts, 1990). Chinese multinationals acquiring high-tech firms are presented then with a broad spectrum of learning opportunities across the target’s functional areas. Indeed, high-tech firms are characterized by substantial product innovation in their area of core competence, yet a high level of knowledge spillover from core to non-core activities is likely to exist in such firms (Parikh, 2001). High-tech firms with substantial product innovations generally have a large stock of advanced knowledge; thus, they are likely to be characterized by innovative activities in other areas: e.g., process innovation, supply-chain logistics, and R&D in related fields (Brynjolfsson & Hitt, 2000). It is then in high-tech sectors where complementarities and synergies between R&D, innovation, higher skills and organizational modifications are likely to occur; which in turn, yields a substantial joint-impact on the technologies, managerial practices and advanced knowledge embedded in these firms (Black & Lynch, 2001; Bresnahan, Brynjolfsson, & Hitt, 2002; Mohnen & Hall, 2013). This larger knowledge pool which is characteristic of high-tech target firms will substantially impact the reverse-knowledge transfer and capability-upgrading process, as Chinese multinationals engaging in cross-border acquisitions of such targets will be able to substantially enhance the cross-functional productivity of their home operations.

Summarizing the above mechanisms, Chinese multinationals engaging in cross-border acquisition activities that target high-tech firms are likely to experience greater degrees of domestic-productivity upgrading as compared to acquisition activities targeting low-tech firms. Most obviously, acquiring high-tech targets provides direct access to the substantial R&D and innovation efforts previously made by these firms situated in dynamic sectors. Yet beyond such evident learning opportunities, high-tech target firms are also characterized by sizable investments in basic research, a higher degree of knowledge appropriability, and a larger stock of advanced knowledge across the functional areas. In light of these factors, the domestic-productivity upgrading experienced by Chinese multinationals is likely to largely stem from acquisitions involving high-tech targets as opposed to acquisitions of low-tech targets – a theoretical a priori that can be set out as follows:

Hypothesis 2

Chinese multinationals experience greater domestic-productivity upgrading when engaging in cross-border acquisitions of high-tech target firms as compared to when engaging in cross-border acquisitions of low-tech target firms.

Related versus unrelated targets

The degree to which the target firm is related to the acquiring firm represents a clear foreign-target characteristic that reflects the organizational context present for reverse-knowledge transfers by emerging-market MNEs. Indeed, Bertrand and Capron (2015) observe that the institutional environment must be conducive to knowledge transfer if multinationals engaging in cross-border acquisition activities are to fully take advantage of foreign learning opportunities. To achieve ‘explorative learning’ and ‘reverse-knowledge transfers’ (Hitt et al., 2005, Hitt et al., 2016), emerging-market multinationals may require a certain degree of relatedness in foreign target firms, as this relatedness can ease and abet the integration, absorption and transfer processes for knowledge. We highlight three mechanisms here that indicate that target-firm relatedness enhances the conditions for knowledge transfer and thereby plays a complementary role in reaping the learning opportunities present with high-tech targets.

First, a general observation within the organizational learning perspective is that successful upgrading requires sufficient absorptive capacity on the part of learning firms (e.g., Hitt et al., 2005). Yet, Cohen and Levinthal (1990) narrow the relevant focus when pointing out that a firm’s absorptive capacity depends mainly on its level of knowledge in a specific field. Accordingly, emerging-market MNEs acquiring foreign targets with substantial business overlap (i.e., relatedness) will be more likely to have the business-area specific knowledge which enables the necessary absorptive capacity for domestic-productivity upgrading. As Prahalad and Bettis (1986) highlight, related acquisition activity involves a common conceptualization – or dominant logic – of what the business actually involves. Moreover, it is fair to point out that the related nature of cross-border acquisition activity may be particularly salient for emerging-market multinationals. Unlike developed-market multinationals, emerging-market MNEs are not always characterized by the experiences and managerial capabilities (e.g., Heckman, 2005; Bloom & Van Reenen, 2010; McKinsey, 2017) which would allow absorbing and exploiting acquired knowledge from all types of foreign firms; e.g., both related and unrelated targets. Cross-border acquisition activities of a related nature will then be characterized by access to new knowledge and technologies that is at least relatively-similar to the emerging-market multinational’s pre-existing knowledge and experiences. Accordingly, emerging-market MNEs will have a greater ability to absorb and integrate the superior knowledge embedded in related targets as compared to the superior knowledge embedded in unrelated targets.

Second, related acquisition activity has generally been deemed to mitigate the downside risks involved with integrating a target firm (e.g., Lubatkin & Lane, 1996). In this vein, Hitt et al. (2001) note that relatedness can reduce the costs involved with learning a target firm’s business which suggests that relatedness leads to reduced integration costs – a fundamental driver of non-synergistic acquisition activity. Moreover, this tighter fit between related firms can ensure a more conducive organizational context in which to transfer and redeploy knowledge. If the emerging-market MNE is unable to sufficiently integrate with foreign targets, then transferring and adapting newly acquired knowledge becomes difficult. Indeed, Duysters and Hagedoorn (2000) observe that the transfer process for exploiting new knowledge is substantially impeded by the insufficient integration which can result from unrelated activities. For example, emerging-market MNEs that share business areas with target firms will be more likely to have had similar experiences and solved analogous problems which in turn enables smoother post-acquisition integration, more seamless knowledge transfer, and the creation of synergies in domestic operations. Relatedly, Kogut and Zander (1992) observe that unrelated technologies often require the learner to substantially alter R&D management; and this, in turn, has been found to negatively affect firm productivity (Ahuja & Katila, 2001). Accordingly, emerging-market multinationals will have a greater ability to transfer and integrate the superior knowledge embedded in related targets as compared to the superior knowledge embedded in unrelated targets.

Third, the relatedness of foreign targets may play a particularly important role in enabling learning and domestic-productivity upgrading as a result of cross-border acquisition activity involving high-tech target firms. Existing research on high-tech acquisitions has identified the relatedness of technological knowledge as an important predictor of post-acquisition performance (Ahuja & Katila, 2001; Cloodt, Hagedoorn, & Van Kranenburg, 2006; Cassiman, Colombo, Garrone, Veugelers, 2005; Hagedoorn & Duysters, 2002). High-tech knowledge can be systematically complex and hard to factor, thus it is important that multinationals engaging in high-tech acquisition activities have sufficient prior knowledge in the target’s specific field in order to transfer, absorb and integrate the acquired knowledge. Accordingly, the more similar the two firms’ technological knowledge, the more quickly the target’s high-tech knowledge can be assimilated into the emerging-market multinational. Indeed, the common skills and similar cognitive structures that are present in related acquisition activities can enable technical communication and learning (Cohen & Levinthal, 1989; Lane & Lubatkin, 1998). Accordingly, emerging-market multinationals will have a greater ability to absorb, transfer and integrate the knowledge embedded in high-tech targets when these targets are based in industries that overlap with that of the multinational.

Summarizing the above, Chinese multinationals engaging in cross-border acquisition activities that target high-tech firms are likely to experience greater degrees of domestic-productivity upgrading when these acquisition activities also involve substantial business overlap between the multinational and the foreign targets. The relatedness of these cross-border acquisition activities increases the absorptive capacity of the multinational and enhances the ability to transfer and redeploy knowledge; furthermore, these learning-conducive properties will be particularly beneficial in the context of high-tech acquisitions. In essence, related acquisition activity creates the proper organizational context that allows for knowledge transfer. Accordingly, the domestic productivity upgrading experienced by Chinese multinationals acquiring high-tech target firms is likely to be further enhanced when that cross-border acquisition activity is also related in nature – a theoretical a priori that can be set out as follows:

Hypothesis 3

Chinese multinationals engaging in cross-border acquisitions of high-tech target firms experience greatest domestic-productivity upgrading when the high-tech targets are based in businesses that are related to the multinational’s pre-existing businesses.

Research methodology

Data collection and sample

Data for this study were compiled and matched from five different sources: Thomson SDC Platinum database (for data on acquisitions, alliances, and foreign-target characteristics), Compustat Global database (for data on domestic capital and materials), China RESSET database (for data on domestic sales, domestic employees, and state ownership), China Data Online (for data on provincial growth rates and industry growth rates), and the Chinese Patent Database (for data on firm patent filing). We first manually matched the SDC and RESSET databases in order to identify Chinese publicly-listed firms which have engaged in cross-border acquisition activities (i.e., Chinese multinationals). Second, we manually matched Compustat Global with the SDC data in order to capture additional accounting-based information for these Chinese multinationals. Third, we matched these multinationals with their experiences from engaging in additional investment activities – i.e., international alliances, domestic alliances and domestic acquisitions – as covered in the SDC database. Fourth, we matched our sampled Chinese multinationals with data from China Data Online on the GDP growth in the multinational’s home province and industry-level revenue growth in the multinational’s primary industry. Fifth, we matched our sampled Chinese multinationals with their yearly count of innovative patent filings from the Chinese Patent Database. Lastly, we merged the above five matched databases into a final dataset.

The final dataset is panel in nature and composed of 329 publicly-listed Chinese multinationals with annual data over the 2000–2010 period. Due to missing variables, 1549 observations represents our largest employable dataset for estimations, though this drops to 1491 observations for a fully nested model. Our focus is on the level of cross-border acquisition activity taken by our sampled MNEs and how these activity levels ultimately impact domestic-productivity upgrading. To test theoretical priors, we assembled a dataset composed of variable constructs based on the firm-year unit of analysis. While annual measures for our sampled Chinese multinationals represents the unit of observation, we can provide some perspective regarding the nature of the individual cross-border acquisitions that constitute the measured cross-border acquisition activities. Specifically, Chinese multinationals engaged in a total of 578 cross-border acquisitions over the 2000–2010 period. This time period represents the years subsequent to the Chinese government’s establishment of the ‘Go Global’ policy in 1999. Importantly, this policy spurred overseas investments (Buckley et al., 2007) with the ultimate aim of encouraging Chinese multinationals to learn from these international experiences by acquiring advanced technologies, knowledge and management skills that would translate into enhanced domestic productivities (Hitt et al., 2005, Hitt et al., 2016); thus, it represents a logical period to examine domestic-productivity effects.

Dependent variable

Our dependent variable of interest is the total factor productivity of the domestic operations of our sampled Chinese multinationals. Labor productivity represents the traditional measure of firm-level productivity; e.g., the Bertrand and Capron (2015) study that considers the impact of cross-border acquisition activity on domestic productivity employs this measure. We should note, however, that TFP analysis represents a substantial improvement as compared to employing a single-factor productivity approach like with labor productivity, as TFP analysis does not omit essential production inputs like capital and materials (Hayes, Wheelwright, & Clark, 1988). Balasubramanian (2011) similarly notes that TFP represents the best means to capture a firm’s ability to turn inputs into outputs.

We follow the Siegel and Simons (2010) methodological approach in operationalizing TFP as our dependent construct. This approach first involves the Chinese multinational’s domestic sales as the nominal dependent variable (hereafter Domestic-Sales). Yet to empirically capture TFP – the residual in the multinationals total output which cannot be explained by the accumulation of traditional inputs – and interpret the coefficient estimates for the explanatory variables as contributing to domestic TFP, the traditional inputs must be controlled for on the right-hand-side of the regression equation. In keeping then with Siegel and Simons (2010), we include three necessary explanatory constructs that allow investigating firm-level domestic TFP. These variables include Domestic-Labor (the Chinese firm’s domestic employee count), Domestic-Capital (the Chinese firm’s domestic capital), and Domestic-Materials (the Chinese firm’s domestic materials). This approach essentially yields an annual measure of domestic TFP as the dependent construct and allows discerning via the inclusion of additional right-hand-side variables what contributes to year-on-year variation in total factor productivity.

Main explanatory variable

The construct of primary interest for our empirical analysis is Cross-Border-Acquisition-Activity; that is, the number of yearly cross-border acquisitions undertaken by Chinese multinationals. Therefore, we examined the acquisition announcement dates for each Chinese cross-border acquisition reported in the Thomson SDC Platinum database and aggregated the acquisitions in the same year into an annual count of cross-border acquisition activities. It is worth underscoring that this variable manifests substantial variation for each multinational over our sampled period, as MNEs do not generally engage in consistent levels of cross-border acquisition activity from year to year (e.g., Bertrand & Betschinger, 2012). While this variable construct suffices to test our first theoretical hypothesis, we needed to break down this variable to test the two additional theoretical contentions.

In order to test the second hypothesis and examine whether the multinational’s productivity gains stem from acquisitions of high-tech foreign targets or acquisitions of low-tech foreign targets, we split the sum of the Chinese multinational’s yearly number of cross-border acquisitions into two explanatory variables based on Thomson SDC’s target firm high-tech industry specification: i.e., we calculate the sum of cross-border acquisitions of high-tech target firms, and the sum of cross-border acquisitions of low-tech target firms in an analogous manner so as to replace the cross-border-acquisition-activity variable in the regression equation.Footnote 2

In order to test the third hypothesis and examine whether the multinational’s productivity gains from acquisitions of foreign targets that are both high-tech and related are greater than the productivity gains from acquisitions of foreign targets that are high-tech but unrelated, we split the sum of the Chinese multinational’s yearly number of cross-border acquisitions into four explanatory variables based on Thomson SDC’s data on the high-tech nature of target firms used above, and Thomson’s data on lines of business covered by the target and acquiring firms.Footnote 3 Specifically, we calculate the sum of cross-border acquisitions where the target is both high-tech and related to the Chinese multinational; the sum of cross-border acquisitions where the target is high-tech but unrelated to the Chinese multinational; the sum of cross-border acquisitions where the target is low-tech but related to the Chinese multinational; and the sum of cross-border acquisitions where the target is both low-tech but unrelated to the Chinese multinational. These four analogously built variables then replace the cross-border-acquisition-activity variable in the regression equation testing our third prior.

Control variables

In order to make stronger causal inferences with respect to the impact of cross-border acquisition activity on domestic-productivity upgrading, it is advisable to control for other investment vehicles via which Chinese multinationals may be able to enhance their domestic productivities. We accordingly control for international-alliance, domestic-acquisition and domestic-alliance activities, as these represent alternative investment vehicles which may also lead to domestic-productivity upgrading. Thus in the same fashion that we compiled the Cross-Border-Acquisition-Activity variable, we also constructed a set of core control variables: International-Alliance-Activity, which denotes the number of yearly international alliances by our sampled Chinese multinationals; Domestic-Acquisition-Activity, which denotes the number of yearly domestic acquisitions by our sampled Chinese multinationals; and Domestic-Alliance-Activity, which denotes the number of yearly domestic alliances by our sampled Chinese multinationals. Controlling for domestic-acquisition activities follows the prescription of Bertrand and Capron (2015) to capture these activities which would seemingly manifest substantial scale economies. While we control for these alternative investment activities (international alliances, domestic acquisitions and domestic alliances), it also advisable to control for whether or not the Chinese multinational is best characterized as a state owned enterprise; thus, SOE denotes if the government is the controlling owner of the Chinese firm. Specifically, the dummy variable takes the value “1” when the government holds a majority stake of 50% or more in the Chinese multinational and takes the value “0” otherwise.

We are also able to follow the advice of Bertrand and Capron (2015) to control for some of the average characteristics of the foreign-target firms acquired by our sampled Chinese multinationals. Specifically, we first follow those who observe that the book-to-value ratio per share can proxy for firm quality (e.g., Guo, Clougherty, & Duso, 2016); hence, we take the target book to value ratio per share for the foreign-target firms in order to capture target-quality tendencies for these Chinese multinationals (hereafter referred to as Targets-Book-Ratio). Second, Lindenberg and Ross (1981) and Villalonga (2004) observe that the market-to-book ratio impounds whether financial markets consider firms to be characterized by high levels of intangible resources or capabilities; hence, we take the market-to-book ratio of the foreign-target firms in order to capture target-intangibles tendencies for these Chinese multinationals (hereafter referred to as Targets-Market-Book). Third, we take the log of the target’s total assets in millions of US$ in order to capture target-size tendencies for these Chinese multinationals (hereafter referred to as Targets-Total-Assets).

In addition to the primary variable of empirical concern (Cross-Border-Acquisition-Activity) and the core control variables noted above, we have added a few additional control constructs. First, a number of scholars have observed that regional characteristics might influence the productivity of multinationals based in that region (e.g., Fleisher & Chen, 1997; Zhou, Li, & Tse, 2002; Bertrand & Capron, 2015); thus, we control for the GDP growth rate in the home province of the sampled Chinese multinational (hereafter referred to as Provincial-Growth-Rate). Second, the characteristics of the industry in which a multinational is primarily based may also impact firm-level productivity (Dekle, 2002; Bertrand & Capron, 2015); thus, we control for the rate of growth in revenue for the Chinese multinationals primary industry (hereafter referred to as Industry-Growth-Rate). Third, Chinese multinationals will obviously undertake direct investments – i.e., R&D expenditures – aimed at enhancing domestic productivity. Bloom and Van Reenen (2002) observe that firm-level measures of R&D expenditure are often not reported in a consistent manner and this was also the case for our sampled Chinese multinationals. We are, however, able to follow Bloom and Van Reenen’s (2002) observation that patent counts have “been a popular choice to proxy innovation” (p. 97); thus, we control for the annual count of innovative patents filed by the Chinese multinational (hereafter referred to as Innovative-Patents).Footnote 4 Table 1 provides descriptions for all of the above variable constructs; and Table 2 provides descriptive statistics and pairwise correlations for these variables.

Estimation method

As previously noted, we employ TFP analysis in order to capture whether domestic-productivity upgrading takes place subsequent to cross-border acquisition activities. TFP represents the residual in an output equation after controlling for production inputs (i.e., labor, capital, and materials); thus, controlling for these factors provides a means to more comprehensively assess a firm’s productivity (Javorcik, 2004; Siegel & Simons, 2010; Wang, Deng, Kafouros, & Chen, 2012). Employing TFP analysis also improves upon the pre-existing literature on domestic-productivity upgrading and cross-border acquisition activity which relied upon labor-productivity analysis (e.g., Bertrand & Capron, 2015) – a single-factor productivity approach that is more sensitive to omitting essential production inputs (Hayes et al., 1988). Specifically, we follow the methodological approach of Siegel and Simons (2010) as they regress the log of sales (the dependent construct) on the logs of labor, capital and materials (explanatory constructs) in order to factor the production inputs that contribute to firm-level productivity. Such an approach allows interpreting the coefficient estimates for any additional right-hand-side constructs as capturing the impact of these variables on firm-level TFP. As exhibited by Bloom and Van Reenen’s (2007) application of this methodological approach, the key behind this methodological approach is that the effects of production inputs (i.e., labor, capital and materials) are controlled for on the right-hand-side of the equation and not controlled for within the left-hand-side variable construct.

In our empirical context for a TFP estimation, we employ the log of domestic sales as the dependent variable, while the logs of domestic labor, domestic capital and domestic materials capture the impact of the production inputs on a Chinese multinational’s domestic productivity. As an aside, considering domestic-productivity upgrading – as opposed to the upgrading of the whole firm – provides a clear context to gather whether these firms are able to learn from their cross-border experiences. The logging of the sales, labor, capital and materials variables is also beneficial due to these measures involving large values and possibly containing outliers. Consequently, logging these variables helps to (1) mitigate any problems with regard to outliers; and (2) establish normality and homoscedasticity in the error terms so as to secure efficiency in the estimations. Yet most importantly, the Siegel and Simons (2010) methodological approach allows interpreting the coefficient estimate for our primary explanatory construct, Cross-Border-Acquisition-Activity, as capturing the effect of cross-border acquisition activities on the Chinese firm’s domestic productivity changes – changes in domestic sales that are not otherwise explained by the changes in production inputs (i.e., labor, capital, and materials).

With the above in mind, the following represents our baseline regression model,

where i indexes the 329 Chinese multinationals, t indexes time (year) and k allows for convenient expressions. Furthermore, ηi represents the unobserved firm-specific effect, φt captures the year dummies, and εit is the idiosyncratic disturbance term.

The four variables capturing the different investment vehicles – cross-border-acquisition-activity and the three control investment activities of domestic-acquisition-activity, international-alliance-activity and domestic-alliance-activity – all consider the investment experiences over the t-2 to t-4 period. For example, a focal firm’s domestic productivity in 2010 is potentially influenced by learning experiences from 2008, 2007 and 2006. We sum the lagged number of activities in order to capture the collective potential to learn from these past experiences. We take such an approach because learning takes time, thus experiences will not lead to contemporaneous productivity gains. In support of this approach, Ahuja and Katila (2001) consider the impact of an acquisition to be impounded over a number of years rather than entirely in any 1 year. Furthermore, the initial lag (the t-1 period) is not considered to provide any learning potential due to the well-recognized reality that major investments involve a transition period for restructuring and integration which inhibits immediate gains and synergies (e.g., Chari, Ouimet, & Tesar, 2010; Jennings, Schulz, Patient, Gravel, & Yuan, 2005; Teece, 1981).Footnote 5 The target-firm characteristics (targets-book-ratio, targets-market-book, and targets-total-assets) are created in analogous manner as they represent an average of these respective characteristics over the relevant t-2 to t-4 period. And for symmetry in variable operationalization, the SOE construct also reflects whether the focal Chinese multinational was dominantly a state-owned-enterprise over the same period.

The provincial-growth-rate and industry-growth-rate variable constructs are beyond the sway of an individual Chinese MNE and thus more-macro in nature. As such, these controls can be considered exogenous in nature and are accordingly captured in the contemporaneous period. Furthermore, our measure of the innovative patenting activity undertaken by our sampled Chinese multinationals is the sum of the contemporaneous (t) and lagged (t-1) periods, as Bloom and Van Reenen (2002) provide evidence that patenting involves a substantial positive effect on TFP growth within a two-year period. As an aside, we rescale the coefficient estimate for innovative-patents by 1/100,000 in order to yield sensible parameters in a context where the impact of one innovative patent on domestic productivity is economically small.

Finally, our regression model is dynamic in nature as it controls for two lags of the dependent variable. The lagged dependent constructs are necessary as they resolve any serial correlation issues in the data. Yet not only does the inclusion of the lagged dependent variables address the presence of autoregressive dynamics, it also ensures a well-specified regression model as a multinational’s domestic sales are clearly not created anew in each annual observation (Finkel, 1995; Wooldridge, 2002). In addition to these estimation issues, Bertrand and Capron (2015) urge scholars to control for firm size to be able to focus on learning and capability upgrading – and not scale economies – as the primary mechanism behind domestic-productivity upgrading. Hitt et al. (2005) also point out that larger and more mature emerging-market firms will be able to learn more from their cross-border experiences; thus, the inclusion of lagged dependent variables controls for the pre-existing domestic size and maturity of the sampled Chinese multinationals.

The inclusion of lagged dependent variables does, however, raise additional econometric issues. In particular, estimating Eq. 1 via an OLS fixed-effects procedure in a dynamic panel-data environment might result in inconsistent coefficient estimates under the presence of serial correlation in the error term. Specifically, the lagged dependent variables in such an estimation are likely to manifest endogeneity which may in turn bias the other coefficient estimates in the regression equation (Wooldridge, 2002). To address this issue, we employ a linear dynamic panel-data estimation technique (System GMM estimation with robust errors) in order to instrument for the potentially endogenous lagged-dependent variable and yield more-asymptotically consistent estimators as compared to the fixed-effects estimation. The GMM-estimation technique is designed for datasets with many panels and few periods, as GMM initially first differences the model to exclude the fixed effects and then instruments for the differenced lagged dependent variables. This first-step estimation is referred to as Difference GMM; however, we engage in a second step by employing System GMM’s two-step estimation technique to obtain parameter estimates based on the initial weight matrix by computing a new weight matrix based on those first-step estimates. Indeed, Arellano and Bover (1995) describe how adding an equation in levels and re-estimating the parameters based on that weight matrix in the second step can leverage additional moment conditions that increase efficiency and reduced finite sample bias as compared to a one-step Difference GMM estimation. Moreover, the System GMM estimator yields more-consistent and more-asymptotically efficient estimators as compared to the fixed-effects technique. Due to the clear need to properly address the endogeneity in the lagged dependent constructs and for reasons of brevity, all of our reported regression estimations employ the System GMM procedure.Footnote 6

One last issue worth noting is that of sample selection and the related self-selection issue (Clougherty, Duso, & Muck, 2016). This study may involve sample-selection bias as our data are only composed of Chinese multinationals which have actually conducted cross-border acquisition activities over our sampled period. This data-sample choice may, however, help mitigate the selection issue as the focal research question involves tracing the productivity upgrading of those Chinese firms which have conducted cross-border acquisition activities. Since all of the firms in this study manifest some outward cross-border acquisition experience (i.e., they are multinationals), this means that the sample is composed of multinationals that have already overcome the liability of foreignness. If the sample was composed of both Chinese firms that did not go abroad and those that did go abroad, then an even more-obvious selection issue would arise as only the “best” – or “most-connected” – firms would actually go abroad while the “worst” – or “less-connected” – firms would actually not go abroad (Hoskisson, Wright, Filatotchev, & Peng, 2013). Such an approach could lead to spurious causal inferences when comparing the best Chinese firms (where domestic productivities are likely to increase) with the worst Chinese firms (where domestic productivities are less likely to increase). The Bertrand and Capron (2015) study takes such an approach, though we should underscore that their study engages in an effort to model that selection process and correct for such biases via a Heckman procedure. Our empirical approach is instead one that considers whether higher levels of cross-border acquisition activity lead to higher levels of domestic-productivity upgrading for those Chinese multinationals engaging in cross-border acquisitions. We should also point out that fully employing the panel nature of our data by including fixed effects would be challenging if both Chinese domestic and multinational firms were sampled, as the domestic firms would not experience variability in the cross-border-acquisition-activity measure over time.

Empirical results

Table 3 reports the empirical results for four regressions that are estimated with the standard System GMM procedure. The first regression (model 1) simply reports a base model where all of the control variables are included but the main explanatory constructs are repressed. The second regression (model 2) estimates Eq. 1 and tests for the first hypothesis. The third regression (model 3) reports the estimation that tests the second hypothesis where cross-border-acquisition-activity is replaced by two constructs capturing acquisitions of high-tech and low-tech target firms. The fourth regression (model 4) reports the estimation that tests the third hypothesis where cross-border-acquisition-activity is replaced by four constructs capturing acquisitions of related/high-tech target firms, unrelated/high-tech target firms, related/low-tech target firms, and unrelated/low-tech target firms.

The regression model appears to be well-specified, as the unreported fixed-effects estimation of Eq. 1 yields a relatively high R-square of 0.66. Furthermore, the System GMM estimation method appears to be appropriate in the sense that the necessary diagnostic conditions are manifest. First, the Arellano-Bond tests for autocorrelation reported in Table 3 indicate that we cannot reject the null hypothesis of no serial correlation in the first-differenced error terms; i.e., there is no second-order autocorrelation. Second, the Sargan tests for over-identifying restrictions reported in Table 3 indicate that there is no over-identification problem in the GMM estimations as there is no substantial correlation between the instruments and the error term. While not reported for brevity, Hansen tests for over-identifying restrictions also yield evidence that the instruments are orthogonal to the error term.

Hypothesis 1 proposed that Chinese multinationals engaging in higher levels of cross-border acquisition activity experience greater domestic-productivity upgrading in subsequent years. We found that the cross-border-acquisition-activity variable consistently manifests a positive and significant impact on a Chinese multinational’s domestic productivity as measured by TFP (see model 2 in Table 3). In terms of economic significance, model 2 indicates that each additional cross-border acquisition yields a 4.47% increase in domestic sales that is not attributable to any expansion in the essential factors of production: capital, materials and labor. Hence, hypothesis 1 is supported as Chinese multinationals appear to upgrade their domestic productivity as a result of cross-border acquisition experiences. As an aside, it is worth comparing these results with that of Bertrand and Capron (2015) where they – while employing a different methodology – find French multinationals to upgrade domestic productivity by 12.5% on average due to cross-border acquisition activity. This tentatively indicates that Chinese multinationals are less adept at generally learning from cross-border acquisition activities as compared to developed-market multinationals.

Hypothesis 2 proposed that Chinese multinationals experience greater domestic-productivity upgrading when engaging in cross-border acquisitions of high-tech targets as compared to cross-border acquisitions of low-tech targets. We found that acquiring high-tech target firms manifested a positive and significant impact on a Chinese multinational’s domestic productivity, while acquiring low-tech targets manifested a positive but insignificant impact on a Chinese multinational’s domestic productivity (see model 3 in Table 3). Thus, it is only the acquisition of high-tech targets that generates domestic-productivity upgrading. In terms of economic significance, each additional cross-border acquisition of a high-tech target yields a 12.8% increase in domestic sales that is not attributable to any expansion in the essential factors of production. Hence, hypothesis 2 is supported in that domestic-productivity upgrading appears to stem from the acquisition of high-tech targets and not from the acquisition of low-tech targets.

Hypothesis 3 proposed that Chinese multinationals engaging in cross-border acquisitions of high-tech targets experience greater domestic-productivity upgrading when the high-tech targets are also related to the multinational’s pre-existing businesses as compared to when the high-tech targets are unrelated to the multinational’s pre-existing businesses. We found that acquiring related/high-tech targets manifests a positive and significant impact on a Chinese multinational’s domestic productivity, and that this effect is larger than acquiring unrelated/high-tech targets (see model 4 in Table 3). Thus, cross-border acquisitions of high-tech targets generate domestic-productivity upgrading regardless of the related nature of the transaction; however, related/high-tech acquisitions dominate unrelated/high-tech acquisitions. In terms of economic significance, each additional related/high-tech acquisition yields a 19.9% increase in domestic sales that is not attributable to any expansion in the essential factors of production, while each additional unrelated/high-tech acquisition yields an equivalent increase of 6.79% in domestic sales. Hence, hypothesis 3 is supported in that the most robust domestic-productivity upgrading appears to stem from the acquisitions of related/high-tech targets.

Since our core results above are all properly interpreted with respect to any expansion in the essential factors of production, it is important to consider the results for the fundamental production-input variables: domestic capital, labor and materials. In line with common wisdom, we find domestic-capital expenditures to positively and significantly impact a Chinese firm’s domestic output – i.e., domestic sales – in all four estimations. Furthermore, we find domestic-materials expenditures to positively impact a Chinese multinational’s domestic output in all four estimations, though this is not statistically significant throughout. Interestingly, we counter-intuitively find a non-significant negative relationship between firm-level employees and domestic output. One explanation for this finding is the fact that domestic-labor is highly correlated with the other input measures (domestic-capital and domestic-materials), as firm-level inputs will clearly tend to co-vary. Another explanation for this finding is the fact that many Chinese multinationals exhibit overstaffing; i.e., they have more personnel than actually required. This stylized fact is certainly in line with the restructuring of the Chinese economy, the burdens this places on labor, and the political sensitivity to firms optimizing their workforce (Deng & Gustafsson, 2013). Therefore, it appears that the number of employees may not be an essential input factor for firm-level productivity in the Chinese context.

With regard to the results for our control variables, the international-alliance-activity variable merits healthy discussion since Hitt et al. (2005) focused on alliances as an investment vehicle that would lead to the upgrading and advancement of emerging-market multinationals. We see that this variable manifests significance in three estimations (models 1–3 in Table 3), thus indicating that international alliance activities tend to generate domestic-productivity increases in subsequent years. The evidence here suggests then that international alliances generally represent effective learning vehicles for Chinese multinationals interested in upgrading domestic productivity.

The domestic-acquisition-activity and domestic-alliance-activity variables also represent important control variables that merit particular discussion. First, the domestic-alliance-activity variable yields an insignificant coefficient estimate in all four regression models. One explanation for this lack of significance may be that alliances often act as a means to ultimately acquire a partnering firm; thus, the benefits of this type of transaction will not immediately manifest (Tong, Reuer, & Peng, 2008; Shi & Prescott, 2011). Second, domestic-acquisition experiences yield a negative and significant coefficient estimate with respect to domestic productivity in all four regression models. Accordingly, these results suggest that not only is learning not present via domestic-acquisition experiences, but domestic acquisitions are potentially destructive in terms of the acquirer’s domestic-productivity outcomes. One explanation for this finding may be that many Chinese domestic acquisitions were conducted under the command of central and local governments to integrate unprofitable domestic firms, maintain employment, and restructure domestic industries due to on-going economic and industry reforms (Pearson, 2005). In light of the origins and aims of these domestic acquisitions, the fact that domestic acquisitions generally harm domestic productivity does conform to reason. Furthermore, this result suggests that scale economies – which should be most-readily reaped via domestic acquisitions – are not pertinent to this empirical context. Bertrand and Capron (2015) urged empirical scholarship to factor scale economies in order to concentrate on learning and capability upgrading as the primary mechanism for domestic-productivity upgrading.