Abstract

We face increasing demand for greater access to effective routine mental health services, including telehealth. However, treatment outcomes in routine clinical practice are only about half the size of those reported in controlled trials. Progress feedback, defined as the ongoing monitoring of patients’ treatment response with standardized measures, is an evidence-based practice that continues to be under-utilized in routine care. The aim of the current review is to provide a summary of the current evidence base for the use of progress feedback, its mechanisms of action and considerations for successful implementation. We reviewed ten available meta-analyses, which report small to medium overall effect sizes. The results suggest that adding feedback to a wide range of psychological and psychiatric interventions (ranging from primary care to hospitalization and crisis care) tends to enhance the effectiveness of these interventions. The strongest evidence is for patients with common mental health problems compared to those with very severe disorders. Effect sizes for not-on-track cases, a subgroup of cases that are not progressing well, are found to be somewhat stronger, especially when clinical support tools are added to the feedback. Systematic reviews and recent studies suggest potential mechanisms of action for progress feedback include focusing the clinician’s attention, altering clinician expectations, providing new information, and enhancing patient-centered communication. Promising approaches to strengthen progress feedback interventions include advanced systems with signaling technology, clinical problem-solving tools, and a broader spectrum of outcome and progress measures. An overview of methodological and implementation challenges is provided, as well as suggestions for addressing these issues in future studies. We conclude that while feedback has modest effects, it is a small and affordable intervention that can potentially improve outcomes in psychological interventions. Further research into mechanisms of action and effective implementation strategies is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

We face a global crisis in routine mental health care. Across the world, markers of behavioral and emotional distress have risen sharply (Kuehn, 2020). This has resulted in the need for greater access to care, which can be at least partially facilitated with virtual means (Douglas et al., 2020; Shore et al., 2020). There is also a need for more effective care in everyday settings. While psychological interventions are generally effective in reducing symptoms and improving functioning in patients (Barkham & Lambert, 2021; Lambert, 2013), effectiveness varies substantially based on where care is delivered. In randomized clinical trials (RCTs), an average of 67% of patients are reliably improved by the end of treatment (Hansen et al., 2002). In a direct comparison between efficacy trials and routine practice data, results showed patient outcomes for the latter to be at an approximate 12% disadvantage compared with patient outcomes in trials (Barkham et al., 2008).

Progress feedback is considered to be one of the most promising methods to improve outcomes in routine care (Barkham et al., 2023a, b; Bickman, 2008; Kazdin, 2008; Wampold, 2015) and has been endorsed for use in routine care by professional organizations, insurance companies, and governments (Boswell et al., 2023). While the principle of providing progress feedback has increasingly been viewed as part of good practice, the reality remains that adoption and implementation by practitioners is low. The aim of the current review is to provide a summary of the existing evidence base for the use of progress feedback, including theorized mechanisms of action and implementation strategies.

What is Progress Feedback?

Progress feedback refers to the ongoing monitoring of patients’ treatment response with standardized measures and routinely feeding this information back to the clinician and/or patient, who can subsequently decide whether alterations in the treatment are indicated. It has been implemented in a wide variety of mental healthcare settings worldwide, ranging from college counseling centers to community mental health care and crisis inpatient settings (De Jong et al., 2018; Lambert et al., 2001; Probst et al., 2013). Progress feedback has also been used with youth populations (Bergman et al., 2018; Bickman et al., 2011, 2016; Connors et al., 2023; Jensen-Doss et al., 2020; Van Sonsbeek et al., 2021) and been applied to problems like common mental health disorders, personality disorders, substance dependence, eating disorders, and psychotic disorders (Crits-Christoph et al., 2012; Davidsen et al., 2017; De Jong et al., 2018; Probst et al., 2013; Schiepek et al., 2016; van Oenen et al., 2016; Bovendeerd et al., 2022). The practice of progress feedback has been described using various labels, such as measurement-based care (Scott & Lewis, 2015), patient-reported outcome measurement (Kendrick et al., 2016), routine outcome monitoring (Wampold, 2015), and outcome feedback (Delgadillo et al., 2017). In this review we adopt progress feedback as the generic term to encompass all variants.

In more advanced progress feedback systems, a patient’s progress is compared to a trajectory derived using data from previous patients. This enables the calculation of expected treatment response curves that visually represent the boundaries within which typical symptom fluctuations are observed over time (Finch et al., 2001). A warning signal or alert is provided when a patient’s current symptoms are significantly more severe than expected, which is referred to as a case that is “not on track” (NOT; Harmon et al., 2007). NOT cases are at risk of poor treatment outcomes, such as enduring symptoms after treatment or deterioration (Lutz et al., 2006). Some systems supplement NOT signaling technologies with clinical support tools (CSTs; e.g., additional questionnaires, instructions, manuals, videos) designed to assist clinicians in identifying and addressing problems that may be interfering with treatment progress (Harmon et al., 2007; Lutz et al., 2019). Although most feedback systems are now premised on the use of session-by-session measures, the systems are heterogeneous in terms of the measures adopted, the algorithms used to identify NOT cases, and the decision-rules to deal with poor progress in therapy.

Evidence Base

Current Evidence Base

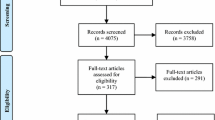

Since its introduction in 2001 (Lambert et al., 2001) more than sixty studies on the effectiveness of progress feedback in psychotherapy have been conducted and eleven meta-analyses of studies applying feedback in mental health care have been published, with divergent findings and conclusions (Bergman et al., 2018; De Jong et al., 2021; Kendrick et al., 2016; Knaup et al., 2009; Lambert et al., 2003, 2018; Østergård et al., 2020; Pejtersen et al., 2020; Rognstad et al., 2023; Shimokawa et al., 2010; Tam & Ronan, 2017; see Table 1). Table 1 shows that overall effect sizes of progress feedback found in meta-analyses range between negligible and medium effect sizes. Effect sizes tend to be stronger in NOT cases (d = 0.17 to d = 0.53; see Table 1), and when CSTs are added for NOT cases (d = 0.35 to 0.49; De Jong et al., 2021; Lambert et al., 2018).

The most comprehensive meta-analysis, summarizing the results of 58 studies, suggests that the overall effect of feedback on symptom reduction is small but robust (fail-safe N = 3695), both for the full samples (d = 0.15) and NOT cases (d = 0.17; De Jong et al., 2021). In addition, feedback significantly reduces the odds of treatment dropout (OR = 1.19). This meta-analysis also demonstrated that the effect of progress feedback is larger for studies conducted in the US, compared to those conducted in other countries, possibly because of differences in care systems and training programs (De Jong et al., 2021). Different types of feedback systems seem to work best for different type of populations, with simpler systems working better for milder populations and more advanced systems working better for more severe populations (De Jong et al., 2021; Østergård et al., 2020).

Most meta-analyses have been limited in their ability to test for moderators and mediators of the effectiveness of progress feedback, largely because few studies report the same variables, or do not report on potential moderators and mediators at all. Systematic reviews have aimed to fill that gap by synthesizing evidence from different studies, even if they do not measure exactly the same constructs (Carlier et al., 2012; Davidson et al., 2015; Gondek et al., 2016; Krägeloh et al., 2015). All these reviews concluded that progress feedback has great potential to improve clinical outcomes, but that its effects may depend on feedback and treatment setting characteristics. Krägeloh and colleagues (2015) created a typology of the complexity of different progress feedback systems, concluding that more advanced systems that apply expected treatment response curves and CSTs tend to produce better outcomes than simpler models. Davidson and colleagues (2015) state that feedback seems mainly effective in the treatment of mild to moderate psychological problems, or at least that in very severe populations the usefulness of progress feedback might be limited. This conclusion is supported by later studies that found no effects and sometimes even potentially detrimental effects of feedback in very severe populations, such as inpatient personality disorder treatment and severe mood disorders (De Jong et al., 2018; Errázuriz & Zilcha-Mano, 2018).

Limitations of the Evidence Base

Akey problem in the feedback literature is that the methodological quality of studies is often relatively poor (Kendrick et al., 2016). To some extent, applying a less methodologically rigid research design is understandable given that feedback studies are often pragmatic trials that study the effects of progress feedback as implemented into routine practice. However, several improvements in study design are warranted. In particular, in the majority of studies, outcome assessments are not conducted independent of the therapy process, and the measure on which feedback is provided is often also the primary outcome measure (Østergård et al., 2020). This problem raises the possibility that the effects of feedback could be partly explained by social desirability bias or demand characteristics of the situation where a patient is primed to closely attend to a specific outcome measure repeatedly. Furthermore, many feedback trials are likely to be statistically underpowered, since the meta-analytic evidence indicates that we should expect small effect sizes, thus requiring larger sample sizes than those observed in most trials (Barkham, 2023; Barkham & Lambert, 2021). In addition, many trials suffer from fidelity issues. When clinicians do not utilize feedback as intended (De Jong et al., 2012), it may substantially reduce the effect size of the intervention compared to treatment as usual.

Moreover, in the majority of studies, there is limited control over the extent to which the feedback provided is actually utilized by the therapist and the consistency with which it is applied (Delgadillo et al., 2022). Feedback systems are frequently offered as packages with many different features, and we do not know much about which features are essential for feedback to be effective. Most studies assessed progress feedback and compared it to no feedback; only some studies have compared the effectiveness of different features of feedback systems (Harmon et al., 2007; Slade et al., 2008). Progress feedback intervention features may include aspects related to the measures (e.g., frequency, type), how interpreted data are visualized and provided to the clinician, the inclusion of comparative benchmarking, and decision support tools. Systems vary in ‘ease of use’ characteristics, such as administration methods for patient-reported measures (e.g., paper-and-pencil or digital, pre-determined and/or tailored), monitoring fidelity for implementation support, and aggregating data for management purposes.

Reporting of key implementation metrics (e.g., measure completion, feedback viewing) is needed to inform benchmarking for quality of implementation (Bickman et al., 2016; Douglas et al., 2023b; Lewis et al., 2019). Future studies should also focus on a broader spectrum of outcome and progress measures (Boswell, 2020). Research on progress feedback should consistently report on dropout and treatment duration, and consider alternative outcomes that may be more relevant to patients’ lived experience, such as quality of life and work/school functioning (Metz et al., 2019; Wolpert et al., 2017). There is also a need for more research on progress feedback in specialized populations, such as child and adolescent psychotherapy (Bergman et al., 2018; Connors et al., 2023; Douglas et al., 2023b; Jensen-Doss et al., 2020) and settings, such as telehealth (Van Tiem et al., 2022).

Emerging Understanding of Potential Mechanisms of Action

Theoretical models of progress feedback suggest it may impact outcomes by focusing the attention of the clinician on discrepancies between their own case conceptualization and what is reported on measures (Riemer & Bickman, 2011; Sapyta et al., 2005). This could serve to change clinician expectations about patient progress and provide new information useful to treatment planning. It has also been suggested that patients’ understanding of their problems, engagement in treatment, and therapeutic alliance may be improved through assessment and feedback (Finn & Tonsager, 1997). Only a few studies have attempted to investigate the potential mechanisms of action of progress feedback. This section provides hypotheses as to how progress feedback might work.

Feedback Focuses Attention of the Clinician

One hypothesis is that feedback might be effective because it draws the attention of the clinician to cases that are not progressing well and are at risk of poor outcomes, thereby enabling them to identify and resolve problems more quickly. Clinicians seem relatively poor at being able to recognize cases that are at risk of poor outcomes (Hannan et al., 2005; Hatfield et al., 2010) and may be unaware that some patients are not benefitting from therapy or are worsening. Recent research by Janse and colleagues (2023) supports the notion that frequent feedback may benefit clinicians with a high level of self-efficacy by correcting their biases towards overestimating their own effectiveness. A feedback system could help clinicians overcome this over-optimistic bias by providing a warning signal, which then draws the attention of the clinician and focuses their attention and efforts on supporting patients who are not progressing well. This hypothesis suggests that the “signal” is the active element that is associated with the effects of feedback, by focusing attention and priming problem-solving efforts.

One RCT investigated this hypothesis in a context where the only difference between intervention and control groups was that clinicians assigned to the feedback condition had access to risk signaling technology, which led to improved outcomes relative to the control group for NOT cases (Delgadillo et al., 2018). However, clinicians using the feedback also had been trained in how to resolve obstacles to clinical improvement in consultation with supervisors, so the “signal effect” hypothesis is only partially supported. Other recent studies have not found beneficial effects of feedback signaling alone and suggest that it can be demoralizing in the absence of specific instructions on how to resolve clinical problems (Errázuriz & Zilcha-Mano, 2018). Hence, it is plausible that supplementing signaling technology with clinical instructions and training is essential to maximize the effects of progress feedback.

Feedback Changes Clinicians’ Expectations

Another potential mechanism is that clinicians’ expectations are altered through the feedback, given their overly optimistic outcome expectations. In a quintessential study, Hannan et al. (2005) asked clinicians to identity the patients in their caseload who would be likely to deteriorate. Clinicians identified 3 out of 550 patients (0.01%) as likely to deteriorate, much lower than the known base rate for their practice. Actual outcomes indicated that 40 patients (7%) had deteriorated by the end of therapy. Thus, clinicians grossly overestimated their patients’ outcomes.

De Jong and colleagues (2024) tracked clinicians’ outcome expectations over time as part of an RCT in which one control group and two feedback groups were compared. In each condition, clinicians rated the odds that their client would improve reliably by the end of therapy at session one, five, and ten. In the control condition, clinicians overestimated the odds of treatment success at each time point, compared to actual outcomes. In the first feedback group, in which clinicians received progress feedback without warning signals, clinicians had similar expectations as in the control group, but because outcomes had improved due to the feedback, their expectations were closer to actual outcomes. In the second feedback group, in which feedback with warning signals and CSTs were provided, outcomes improved, but expectations had decreased as well by session ten. Thus, feedback that uses warning signals and CSTs might work in part because clinicians’ overoptimistic outcome expectations are altered, perhaps making them more alert to intervene when patients do not progress well. However, more research is needed on the topic to draw more definite conclusions.

Feedback Provides New Information

Feedback may also simply provide clinicians with new information that they would not otherwise have gathered. Douglas et al. (2015) found that when feedback is provided, topics that are rated by patients as important were discussed sooner in the course of therapy compared with when no feedback was provided. Moreover, studies applying CSTs that assess the therapy process (e.g., working alliance, motivation) have also found larger effects than obtained in studies using feedback systems not applying CSTs (Shimokawa et al., 2010). In general, there seems to be a tendency for feedback systems to yield larger effect sizes when they assess multiple aspects of the therapy process.

An interesting new study makes a strong case for the inclusion of treatment process measures in progress feedback (Camacho et al., 2021). At each daily session, patients completed measures of symptoms and wellbeing, and also answered questions about how they were applying skills (e.g., cognitive reappraisal) they were learning during a 10-day cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) group treatment. There was a predictive relationship between self-reported application of CBT skills and patient outcomes. Greater confidence in and use of CBT skills learned in treatment were associated with greater wellbeing and lower symptoms. The inclusion of treatment process measures, such as application of therapy skills, in progress feedback would allow clinicians early in treatment to target where there is low use or lack of confidence in skills and thus bolster the likelihood of a positive treatment response. This is consistent with recommendations to use progress feedback to guide adaptation and tailor care (Georgiadis et al., 2020), especially in terms of reactive flexibility, where the clinician adjusts treatment as it progresses to be responsive to emerging factors.

Feedback Enhances Patient-Clinician Communication

In a systematic review on feedback effects in somatic and mental health care, Carlier and colleagues (2012) found that progress feedback improved patient-provider communication both in the short and longer term. A qualitative study of patients and clinicians’ views of clinical feedback systems found that such systems supported collaboration, enabled open conversation, and enhanced interpersonal processes (Moltu et al., 2018). Patients generally find feedback informative (Delgadillo et al., 2017; Lutz et al., 2015) and qualitative studies of feedback utilization reported that completing the questionnaires helped patients focus on what they want to talk about in the session with the clinician, as well as helped them learn which coping skills are more or less effective in managing their symptoms and problems (Delgadillo et al., 2017; Unsworth et al., 2012).

The use of progress feedback to inform patient-clinician communication is complex, partially because it involves at least two actors and the interaction between them. Clinicians may vary in their skill at integrating feedback information with other ongoing processes in treatment and ability to make it meaningful for patients. Thus, the use of feedback in clinical communication is likely both a mechanism of action for how feedback works but also will influence (and be influenced by) the quality of implementation. A systematic review and meta-analysis of qualitative studies of both clinician and patient perspectives on feedback highlighted the use of feedback data to facilitate communication (Låver et al., 2023). The authors suggest that patient-reported data go beyond objective measures of functioning by supporting exploration, reflection, and shifts in care. Two qualitative studies focused on patient preferences related to valuing progress feedback in treatment (Holliday et al., 2021; Solstad et al., 2021). Both studies emphasized the need for clinicians to routinely share some information about progress feedback in a meaningful way, yet also to tailor how that information is shared to the needs and preferences of the patient. A list of eight recommendations for communicating with patients about progress feedback is summarized in Table 2. The use of progress feedback should be considered a clinical skill, which needs to be both taught and practiced to reach its full potential.

There is even greater complexity for patient-clinician communication when considering youth psychotherapy, which typically involves multiple actors in the treatment process. With youth and caregiver respondents, the clinician must exercise clinical skill and ethical practice around confidentiality in weighing how to utilize each distinct perspective in treatment (Connors et al., 2023; Douglas et al., 2023b; Jensen-Doss et al., 2020). It has been established that youths and caregivers provide uniquely valuable information about treatment targets and outcomes (De Los Reyes et al., 2023). Such discrepancies in feedback data may represent opportunities for the clinician to engage youths and their caregivers in conversations about their different perspectives. Case examples indicate that this type of clinician-facilitated communication using feedback data contributes to shared understanding, collaborative decision-making, and empowered voice for young people (Connors et al., 2023; Douglas et al., 2023b; Jensen-Doss et al., 2020). Objectively, there may also be differences in how respondent measures predict treatment outcomes. For example, two RCTs conducted by Bickman and colleagues found that the impact of feedback on youth mental health outcomes differed by reporter, with clinician-report of youth symptoms showing greater improvement in both studies (Bickman et al., 2011, 2016) and youth-reported symptoms improving faster in only the former study.

The potential for progress feedback to enhance communication is especially relevant in today’s world with the recent global pandemic and the rapid rise in telehealth services. Telehealth is here to stay, and the addition of progress feedback as a transtheoretical and transdiagnostic intervention may enhance systematic ongoing monitoring, treatment engagement, and therapeutic alliance in the context of the virtual encounter (Douglas et al., 2020). In addition to strategies summarized in Table 2, recommendations for using progress feedback in telehealth include technological accessibility issues (e.g., digital means for sending and completing measures, ability to show screens) and measurement considerations (e.g., individualized items, risk monitoring, and therapeutic alliance) (Douglas et al., 2020; Van Tiem et al., 2022).

Feedback Enhances the Therapeutic Alliance

There is emerging evidence that the therapeutic alliance (TA) is influenced by progress feedback. Brattland and colleagues (2019) found that in the first two months of treatment, the TA increased more when progress feedback was used in treatment, compared to when no progress was provided. In addition, an increase in TA was associated with better treatment outcomes, suggesting that TA moderated the effect of progress feedback on treatment outcomes (Brattland et al., 2019). The influence of feedback to direct attention and communication between a clinician and patient (and caregivers) is likely to improve collaborative and patient-centered care (Carlier et al., 2012), and treatment engagement (e.g., fewer drop-outs from care, De Jong et al., 2021), which aligns with Bordin’s (1979, 1994) tripartite definition of TA as agreement on therapeutic goals, the tasks to achieve those goals, and the bond between the clinician and patient (and/or caregivers). There is also emerging evidence for the addition of measures of treatment process (e.g., TA) as part of a multidimensional approach to progress feedback (Connors et al., 2021; Jensen-Doss et al., 2020). Whether a standard part of the measurement package (e.g., Bickman et al., 2011, 2016) or queued up as part of additional clinical decision support based on symptom trajectory (e.g., De Jong et al., 2021), the inclusion of such measures can improve clinicians’ ability to recognize TA ruptures and shifts in engagement to directly address them in treatment (Chen et al., 2018).

Implementation Issues and Strategies

Despite robust findings of progress feedback’s effects on treatment outcomes, the implementation of progress feedback in routine clinical practice is often low (Jensen-Doss et al., 2018; Patterson et al., 2006). Although routine outcome measurement is mandatory in many countries, measuring outcomes does not necessarily mean that this information is being used to inform treatment. Several studies have shown that even in RCTs, up to half the clinicians do not use the progress feedback to inform treatment decisions (De Jong et al., 2012; Simon et al., 2012). In their 2011 RCT, Bickman and colleagues found that one-third of clinicians never even viewed a progress feedback report. Based on a content analysis of clinicians’ written notes about using feedback in sessions, Casline and colleagues (2023) found they incorporated feedback data into about one-fifth of sessions. When data were used, they were used inconsistently and typically for short-term purposes (e.g., current symptoms) rather than long-term decision-making. Recent findings by Van Sonsbeek et al. (2023) suggest that implementing progress feedback in large mental health care organizations presents challenges related to clinician characteristics and a lack of adequate guidance, which leads to limited impact on client outcomes. Deisenhofer and colleagues (2024) provide a substantial review of the barriers to implementing the broad class of precision methods in personalizing the psychological therapies that includes feedback and the possible ways of resolving them.

Good integration into everyday clinical practice seems to be a crucial factor in the effectiveness of progress feedback on improving outcomes, which strongly increases with better implementation (Bickman et al., 2016; Brattland et al., 2018). McLeod and colleagues (2022) propose a framework for progress feedback approaches that focuses on meaningful use to improve care while also allowing for flexibility in how feedback is implemented based on characteristics and goals of the practice setting. Barber and Resnick (2022) introduced the Collect, Share, Act model as a valuable approach for integrating and utilizing progress feedback in clinical sessions. Douglas and colleagues (Douglas et al., 2023b; Jensen-Doss et al., 2020; Youn et al., 2023) expand on this approach to encompass the organizational setting and larger health care system. They propose a simple strategy of identifying the value that feedback can bring to promote use at each level, from use of one point-in-time in a session to aggregating data across sessions, patients, clinicians, and ultimately within and across services and organizations.

Overall, there is a small but growing literature on barriers and facilitators that influence the adoption and sustained use of progress feedback systems (De Jong & De Goede, 2015; Douglas et al., 2016, 2023a; Jensen-Doss et al., 2020; Lewis et al., 2019). Implementation is complex and requires attention at multiple levels including the individual patient, clinician, organization, and system level. Recent qualitative and quantitative studies of clinician and patient perspectives suggest four themes that impact implementation of feedback systems in mental health settings: practical considerations, attitudinal concerns, interventional issues (e.g., selection of measures), and context (e.g., organizational-level variables; Boyce et al., 2014; Douglas et al., 2023a; Lewis et al., 2019; Town et al., 2017).

Practical concerns relate to perceived difficulties with administering outcome measures and integrating the feedback into typical clinic workflow, such as the time burden, unclear roles or guidelines, technological difficulties, and the need for training and support. Barriers at individual patient- and clinician-levels are often related to practical concerns about infrastructure and leadership support, in addition to negative attitudes about the usefulness and acceptability of incorporating measures as part of routine practice (Gleacher et al., 2016; Rye et al., 2019; Walter et al., 1998). For example, therapists and patients have expressed concerns about undermining the therapeutic relationship, the measures being too simplistic to reflect the typical complexity of individual cases, and how data may be used to evaluate the therapist’s performance. There is also a need for more research to better understand how progress feedback systems can be better designed to fit diverse populations and settings. In addition to determining cultural equivalence in different patient populations, recent research suggests that clinicians’ cultural identity and perceptions of fit may influence access to progress feedback (Boswell et al., 2023). Shifts in how progress feedback is structured and implemented may improve feasibility and acceptance in diverse settings.

The selection of measures is particularly important. Some research indicates patients’ preferences for measures that assess positive aspects of treatment progress such as quality of life and wellbeing (Crawford et al., 2011; Kilbourne et al., 2010; Lyon et al., 2016). In several qualitative studies of clinicians’ attitudes toward feedback systems, the perceived relevance (or lack thereof) of the data to ongoing clinical care has been reported (Wolpert et al., 2016). For example, in a case example (Douglas et al., 2023a, b clinician reported that one of her youth patients found the symptom measure helpful but wished that there could also be questions relevant to an emerging gender dysphoria. Individualized measures may be useful to tailoring feedback for specific populations, such as goal attainment scales for older adults (Clair et al., 2022; Giovanetti et al., 2021) and goal-based outcome measures and problem rating scales for youth patients (Edbrooke-Childs et al., 2015; Weisz et al., 2011). More positive attitudes toward feedback systems were linked to more frequent use of feedback (De Jong et al., 2012; Jensen-Doss et al., 2018; Rye et al., 2019). These findings suggest that it is important to address concerns form clinicians and patients regarding the implementation of measures.

Organizational-level factors that should be considered when implementing progress feedback include adequate attention to resources for (continuous) training (Edbrooke-Childs et al., 2016), matching the feedback information flow to organizational infrastructure and priorities (Douglas et al., 2016; Jensen-Doss et al., 2020), and being mindful of potential misuse of feedback data as part of performance evaluation (De Jong, 2016). Feedback systems may also be useful in supporting existing organizational quality processes, such as clinical supervision (Fullerton et al., 2018) and quality improvement initiatives (Devine et al., 2013), where aggregated data can help identify areas of improvement for both clinicians and organizations. Progress feedback can help to identify cases for ongoing clinician reflection and learning as an important part of deliberate practice, a method aimed at improving the therapeutic skills of clinicians (Chow et al., 2015). Douglas and colleagues (2023a) suggest that assessing organizational management and clinical leadership perspectives is key to informing better implementation of progress feedback. A qualitative analysis of clinician, supervisor, and leader interviews from nine mental health organizations across three countries resulted in a framework for describing barriers and facilitators related to people, processes, structures, and contexts. These are both internal to organizations and external, representing health care system and national policy influences on implementation, such as national mandates or reimbursement strategies (e.g., Roe et al., 2021). While such a systemic approach to progress feedback implementation is quite complex, ultimately it is necessary to help us not only understand but also influence behavior change and organizational learning for better feedback practice.

Conclusion

Having gained considerable momentum in the last decade, research has yielded compelling evidence of the potential for progress feedback to improve treatment outcomes in routine care for patients with common mental health problems, although it may be contra-indicated for patients with severe mental disorders or personality disorders. But it is not a panacea and the evidence base has limitations. However, potential mechanisms of action may include focusing the attention of the clinician, ‘rightsizing’ clinician expectations for improvement, providing new and relevant clinical information, and enhancing patient-centered communication. Promising approaches to strengthen progress feedback interventions include more advanced systems with signaling technology, clinical problem-solving tools, a broader spectrum of outcome and progress measures, together with the recognition that feedback-informed treatment is both a pan-theoretical psychotherapeutic method and a clinical skill that may improve with training, implementation support, and deliberate practice.

References

Barber, J., & Resnick, S. G. (2022). Collect, share, Act: A transtheoretical clinical model for doing measurement-based care in mental health treatment. Psychological Services, 20(Suppl 2), 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000629.

Barkham, M. (2023). Smaller effects matter in the psychological therapies: 25 years on from Wampold et al. (1997). Psychotherapy Research, 33(4), 530–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2022.2141589.

Barkham, M., & Lambert, M. J. (2021). The efficacy and effectiveness of psychological therapies. In M. Barkham, W. Lutz, & L. G. Castonguay (Eds.), Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change: 50th anniversary edition (pp. 135–189). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Barkham, M., Stiles, W. B., Connell, J., Twigg, E., Leach, C., Lucock, M., Mellor-Clark, J., Bower, P., King, M., Shapiro, D. A., Hardy, G. E., Greenberg, L., & Angus, L. (2008). Effects of psychological therapies in randomized trials and practice-based studies. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 47(4), 397–415. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466508X311713.

Barkham, M., De Jong, K., Delgadillo, J., & Lutz, W. (2023b). Routine outcome monitoring. In C. E. Hill & J. C. Norcross (Eds.), Psychotherapy skills and methods that work. Oxford Academic. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197611012.003.0015.

Barkham, M., De Jong, K., Delgadillo, J., & Lutz, W. (2023a). Routine outcome monitoring (ROM) and feedback: Research review and recommendations. Psychotherapy Research, 33(7), 841–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2023.2181114.

Bergman, H., Kornør, H., Nikolakopoulou, A., Hanssen-Bauer, K., Soares‐Weiser, K., Tollefsen, T. K., & Bjørndal, A. (2018). Client feedback in psychological therapy for children and adolescents with mental health problems. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 8(8), CD011729. https://doi.org/.

Bickman, L. (2008). A measurement feedback system (MFS) is necessary to improve mental health outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(10), 1114–1119. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181825af8.

Bickman, L., Kelley, S. D., Breda, C., de Andrade, A. R., & Riemer, M. (2011). Effects of routine feedback to clinicians on mental health outcomes of youths: Results of a randomized trial. Psychiatric Services, 62(12), 1423–1429. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.002052011.

Bickman, L., Douglas, S., De Andrade, A. R. V., Tomlinson, M., Gleacher, A., Olin, S., & Hoagwood, K. (2016). Implementing a measurement feedback system: A tale of two sites. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(3), 410–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-015-0647-8.

Bordin, E. (1994). Theory and research on the working alliance: New directions. In A. Horvath, & L. Greenberg (Eds.), The working alliance: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 13–37). Wiley.

Bordin, E. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytical concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy Theory Research and Practice, 16(3), 252–260. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0085885.

Boswell, J. F. (2020). Monitoring processes and outcomes in routine clinical practice: A promising approach to plugging the holes of the practice-based evidence colander. Psychotherapy Research, 30(7), 829–842. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1686192.

Boswell, J. F., Hepner, K. A., Lysell, K., Rothrock, N. E., Bott, N., Childs, A. W., Douglas, S., Owings-Fonner, N., Wright, C. V., Stephens, K. A., Bard, D. E., Aajmain, S., & Bobbitt, B. L. (2023). The need for a measurement-based care professional practice guideline. Psychotherapy, 60(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000439.

Bovendeerd, B., De Jong, K., De Groot, E., Moerbeek, M., & De Keijser, J. (2022). Enhancing the effect of psychotherapy through systematic client feedback in outpatient mental healthcare: A cluster randomized trial. Psychotherapy Research, 32(6), 710–722. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2021.2015637.

Boyce, M. B., Browne, J. P., & Greenhalgh, J. (2014). The experiences of professionals with using information from patient-reported outcome measures to improve the quality of healthcare: A systematic review of qualitative research. BMJ Quality & Safety, 23(6), 508–518. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002524.

Brattland, H., Koksvik, J. M., Burkeland, O., Gråwe, R. W., Klöckner, C., Linaker, O. M., Ryum, T., Wampold, B., Lara-Cabrera, M. L., & Iversen, V. C. (2018). The effects of routine outcome monitoring (ROM) on therapy outcomes in the course of an implementation process: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(5), 641–652. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000286.

Brattland, H., Koksvik, J. M., Burkeland, O., Klöckner, C. A., Lara-Cabrera, M. L., Miller, S. D., Wampold, B., Ryum, T., & Iversen, V. C. (2019). Does the working alliance mediate the effect of routine outcome monitoring (ROM) and alliance feedback on psychotherapy outcomes? A secondary analysis from a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 66(2), 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000320.

Camacho, K. S., Page, A. C., & Hooke, G. R. (2021). An exploration of the relationships between patient application of CBT skills and therapeutic outcomes during a two-week CBT treatment. Psychotherapy Research, 31(6), 778–788. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2020.1845414.

Carlier, I. V. E., Meuldijk, D., Van Vliet, I. M., Van Fenema, E., Van der Wee, N. J. A., & Zitman, F. G. (2012). Routine outcome monitoring and feedback on physical or mental health status: Evidence and theory. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 18(1), 104–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01543.x.

Casline, E., Woodard, G., Patel, Z. S., Phillips, D. A., Ehrenreich-May, J., Ginsburg, G. S., & Jensen-Doss, A. (2023). Characterizing measurement-based care implementation using therapist report. Evidence-based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 8(4), 549–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2022.2124555.

Chen, R., Atzil-Slonim, D., Bar-Kalifa, E., Hasson-Ohayon, I., & Refaeli, E. (2018). Therapists’ recognition of alliance ruptures as a moderator of change in alliance and symptoms. Psychotherapy Research, 28(4), 560–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2016.1227104.

Chow, D. L., Miller, S. D., Seidel, J. A., Kane, R. T., Thornton, J. A., & Andrews, W. P. (2015). The role of deliberate practice in the development of highly effective psychotherapists. Psychotherapy, 52(3), 337–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000015.

Clair, C. A., Sandberg, S. F., Scholle, S. H., Willits, J., Jennings, L. A., & Giovannetti, E. R. (2022). Patient and provider perspectives on using goal attainment scaling in care planning for older adults with complex needs. Journal of patient-reported Outcomes, 6(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-022-00445-y.

Connors, E. H., Douglas, S., Jensen-Doss, A., Landes, S. J., Lewis, C. C., McLeod, B. D., & Lyon, A. R. (2021). What gets measured gets done: How mental health agencies can leverage measurement-based care for better patient care, clinician supports, and organizational goals. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 48, 250–265.

Connors, E. H., Childs, A. W., Douglas, S., & Jensen-Doss, A. (2023). Data-informed communication: How measurement-based care can optimize child psychotherapy [Manuscript submitted for publication]. Yale University School of Medicine.

Crawford, M. J., Robotham, D., Thana, L., Patterson, S., Weaver, T., Barber, R., Wykes, T., & Rose, D. (2011). Selecting outcome measures in mental health: The views of service users. Journal of Mental Health, 20(4), 336–346. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2011.577114.

Crits-Christoph, P., Ring-Kurtz, S., Hamilton, J. L., Lambert, M. J., Gallop, R., McClure, B., Kulaga, A., & Rotrosen, J. (2012). A preliminary study of the effects of individual patient-level feedback in outpatient substance abuse treatment programs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 42(3), 301–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2011.09.003.

Davidsen, A. H., Poulsen, S., Lindschou, J., Winkel, P., Tróndarson, M. F., Waaddegaard, M., & Lau, M. (2017). Feedback in group psychotherapy for eating disorders: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(5), 484–494. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000173.

Davidson, K., Perry, A., & Bell, L. (2015). Would continuous feedback of patient’s clinical outcomes to practitioners improve NHS psychological therapy services? Critical analysis and assessment of quality of existing studies. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 88(1), 21–37.

Deisenhofer, A. K., Barkham, M., Beierl, E. T., Schwartz, B., Aafjes-van Doorn, K., Beevers, C. G., Berwian, I. M., Blackwell, S. E., Bockting, C. L., Brakemeier, E. L., Brown, G., Buckman, J. E. J., Castonguay, L. G., Cusack, C. E., Dalgleish, T., De Jong, K., Delgadillo, J., DeRubeis, R. J., Driessen, E., Ehrenreich-May, J., … Cohen, Z. D. (2024). Implementing precision methods in personalizing psychological therapies: Barriers and possible ways forward. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 172, 104443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2023.104443

De Jong, K. (2016). Deriving implementation strategies for outcome monitoring feedback from theory, research and practice. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(3), 292–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-014-0589-6.

De Jong, K., & De Goede, M. (2015). Why do some therapists not deal with outcome monitoring feedback? A feasibility study on the effect of regulatory focus and person-organization fit on attitude and outcome. Psychotherapy Research, 25(6), 661–668. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2015.1076198.

De Jong, K., van Sluis, P., Nugter, M. A., Heiser, W. J., & Spinhoven, P. (2012). Understanding the differential impact of outcome monitoring: Therapist variables that moderate feedback effects in a randomized clinical trial. Psychotherapy Research, 22(4), 464–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2012.673023.

De Jong, K., Segaar, J., Ingenhoven, T., van Busschbach, J., & Timman, R. (2018). Adverse effects of outcome monitoring feedback in patients with personality disorders: A randomized controlled trial in day treatment and inpatient settings. Journal of Personality Disorders, 32(3), 393–413. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2017_31_297.

De Jong, K., Conijn, J. M., Gallagher, R. A. V., Reshetnikova, A. S., Heij, M., & Lutz, M. C. (2021). Using progress feedback to improve outcomes and reduce drop-out, treatment duration, and deterioration: A multilevel meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 85, 102002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102002.

De Jong, K., Symmonds-Buckley, M., Delgadillo, J., & Nugter, M. A. (2024). Therapist expectations as a mechanism of progress feedback during psychological treatment: Testing a theoretical model (in preparation).

De Los Reyes, A., Epkins, C. C., Asmundson, G. J. G., Augenstein, T. M., Becker, K. D., Becker, S. P., Bonadio, F. T., Borelli, J. L., Boyd, R. C., Bradshaw, C. P., Burns, G. L., Casale, G., Causadias, J. M., Cha, C. B., Chorpita, B. F., Cohen, J. R., Comer, J. S., Crowell, S. E., Dirks, M. A., Drabick, D. A. G., & Youngstrom, E. A. (2023). Editorial Statement about JCCAP’s 2023 special issue on informant discrepancies in Youth Mental Health assessments: Observations, guidelines, and future directions grounded in 60 years of Research. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology American Psychological Association Division, 53(1), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2022.2158842. 52.

Delgadillo, J., Overend, K., Lucock, M., Groom, M., Kirby, N., McMillan, D., Gilbody, S., Lutz, W., Rubel, J. A., & De Jong, K. (2017). Improving the efficiency of psychological treatment using outcome feedback technology. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 99, 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2017.09.011.

Delgadillo, J., De Jong, K., Lucock, M., Lutz, W., Rubel, J., Gilbody, S., Ali, S., Aguirre, E., Appleton, M., Nevin, J., O’Hayon, H., Patel, U., Sainty, A., Spencer, P., & McMillan, D. (2018). Feedback-informed treatment versus usual psychological treatment for depression and anxiety: A multisite, open-label, cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(7), 564–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30162-7.

Delgadillo, J., Deisenhofer, A., Probst, T., Shimokawa, K., Lambert, M. J., & Kleinstauber, M. (2022). Progress feedback narrows the gap between more and less effective therapists: A therapist effects meta-analysis of clinical trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 90(7), 559–567. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000747.

Devine, E. B., Alfonso-Cristancho, R., Devlin, A., Edwards, T. C., Farrokhi, E. T., Kessler, L., Lavallee, D. C., Patrick, D. L., Sullivan, S. D., Tarczy-Hornoch, P., Yanez, N. D., & Flum, D. R. (2013). A model for incorporating patient and stakeholder voices in a learning health care network: Washington State’s comparative Effectiveness Research Translation Network. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 66(8 Suppl), S122–S129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.04.007.

Douglas, S., Jonghyuk, B., de Andrade, A. R. V., Tomlinson, M. M., Hargraves, R. P., & Bickman, L. (2015). Feedback mechanisms of change: How problem alerts reported by youth clients and their caregivers impact clinician-reported session content. Psychotherapy Research, 25(6), 678–693. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2015.1059966.

Douglas, S., Button, S., & Casey, S. E. (2016). Implementing for sustainability: Promoting use of a measurement feedback system for innovation and quality improvement. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(3), 286–291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-014-0607-8.

Douglas, S., Jensen-Doss, A., Ordorica, C., & Comer, J. S. (2020). Strategies to enhance communication with telemental health measurement-based care (tMBC). Practice Innovations, 5(2), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/pri0000119.

Douglas, S., Bovendeerd, B., van Sonsbeek, M., Manns, M., Milling, X. P., Tyler, K., Bala, N., Satterthwaite, T., Hovland, R. T., Amble, I., Atzil-Slonim, D., Barkham, M., de Jong, K., Kendrick, T., Nordberg, S. S., Lutz, W., Rubel, J. A., Skjulsvik, T., & Moltu, C. (2023a). A Clinical Leadership Lens on Implementing Progress Feedback in Three Countries: Development of a Multidimensional Qualitative Coding Scheme. Administration and policy in mental health, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-023-01314-6. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-023-01314-6.

Douglas, S., Woodard, G., Zahora, J., Love, T., & Jensen-Doss, A. (2023b). Using visuals as props to generate questions and guide conversation: Lessons learned from implementing progress feedback in youth community mental health settings. In J. Rubel, & W. Lutz (Eds.), Advances in the Science and Practice of Feedback-informed psychological therapy. Springer Nature. [Manuscript submitted for publication].

Edbrooke-Childs, J., Jacob, J., Law, D., Deighton, J., & Wolpert, M. (2015). Interpreting standardized and idiographic outcome measures in CAMHS: What does change mean and how does it relate to functioning and experience? Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 20(3), 142–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12107.

Edbrooke-Childs, J., Wolpert, M., & Deighton, J. (2016). Using patient reported outcome measures to improve service effectiveness (UPROMISE): Training clinicians to use outcome measures in child mental health. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Service Research, 43, 302–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-014-0600-2.

Errázuriz, P., & Zilcha-Mano, S. (2018). In psychotherapy with severe patients discouraging news may be worse than no news: The impact of providing feedback to therapists on psychotherapy outcome, session attendance, and the alliance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(2), 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000277.

Finch, A. J. E., Lambert, M. J., & Schaalje, B. G. (2001). Psychotherapy quality control: The statistical generation of expected recovery curves for integration into an early warning system. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 8, 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.286.

Finn, S. E., & Tonsager, M. E. (1997). Information-gathering and therapeutic models of assessment: Complementary paradigms. Psychological Assessment, 9(4), 374–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.9.4.374.

Fullerton, M., Edbrooke-Childs, J., Law, D., Martin, K., Whelan, I., & Wolpert, M. (2018). Using patient-reported outcome measures to improve service effectiveness for supervisors: A mixed-methods evaluation of supervisors’ attitudes and self-efficacy after training to use outcome measures in child mental health. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 23(1), 34–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12206.

Georgiadis, C., Peris, T. S., & Comer, J. S. (2020). Implementing strategic flexibility in the delivery of youth mental health care: A tailoring framework for thoughtful clinical practice. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 5(3), 215–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2020.1796550.

Gleacher, A. A., Olin, S. S., Nadeem, E., Pollock, M., Ringle, V., Bickman, L., Douglas, S., & Hoagwood, K. (2016). Implementing a measurement feedback system in community mental health clinics: A case study of multilevel barriers and facilitators. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(3), 426–440.

Gondek, D., Edbrooke-Childs, J., Fink, E., Deighton, J., & Wolpert, M. (2016). Feedback from outcome measures and treatment effectiveness, treatment efficiency, and collaborative practice: A systematic review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(3), 325–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-015-0710-5.

Hannan, C., Lambert, M. J., Harmon, C., Nielsen, S. L., Smart, D. W., Shimokawa, K., & Sutton, S. W. (2005). A lab test and algorithms for identifying clients at risk for treatment failure. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20108.

Hansen, N. B., Lambert, M. J., & Forman, E. M. (2002). The psychotherapy dose-response effect and its implications for treatment delivery services. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy: Science and Practice, 9(3), 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.9.3.329.

Harmon, C. S., Lambert, M. J., Smart, D. M., Hawkins, E., Nielsen, S. L., Slade, K., & Lutz, W. (2007). Enhancing outcome for potential treatment failures: Therapist-client feedback and clinical support tools. Psychotherapy Research, 17(4), 379–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300600702331.

Hatfield, D., McCullough, L., Frantz, S. H., & Krieger, K. (2010). Do we know when our clients get worse? An investigation of therapists’ ability to detect negative client change. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 17(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.656.

Holliday, S. B., Hepner, K. A., Farmer, C. M., Mahmud, A., Kimerling, R., Smith, B. N., & Rosen, C. (2021). Discussing measurement-based care with patients: An analysis of clinician-patient dyads. Psychotherapy Research, 31(2), 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2020.1776413.

Janse, P. D., Veerkamp, C., de Jong, K., van Dijk, M. K., Hutschemaekers, G. J. M., & Verbraak, M. J. P. M. (2023). Exploring therapist characteristics as potential moderators of the effects of client feedback on treatment outcome. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 30(3), 690–701. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2828.

Jensen-Doss, A., Haimes, E. M. B., Smith, A. M., Lyon, A. R., Lewis, C. C., Stanick, C. F., & Hawley, K. M. (2018). Monitoring treatment progress and providing feedback is viewed favorably but rarely used in practice. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45, 48–61.

Jensen-Doss, A., Douglas, S., Phillips, D. A., Gencdur, O., Zalman, A., & Gomez, N. E. (2020). Measurement-based care as a practice improvement tool: Clinical and organizational applications in youth mental health. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 5(3), 233–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2020.1784062.

Kazdin, A. E. (2008). Evidence-based treatment and practice: New opportunities to bridge clinical research and practice, enhance the knowledge base, and improve patient care. American Psychologist, 63(3), 146–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.3.146.

Kendrick, T., El-Gohary, M., Stuart, B., Gilbody, S., Churchill, R., Aiken, L., Bhattacharya, A., Gimson, A., Brütt, A. L., De Jong, K., & Moore, M. (2016). Routine use of patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) for improving treatment of common mental health disorders in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7(7), CD011119. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011119.pub2.

Kilbourne, A. M., Keyser, D., & Pincus, H. A. (2010). Challenges and opportunities in measuring the quality of mental health care. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie, 55(9), 549–557. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371005500903.

Knaup, C., Koesters, M., Schoefer, D., Becker, T., & Puschner, B. (2009). Effect of feedback of treatment outcome in specialist mental healthcare: Meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 195(1), 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.053967.

Krägeloh, C. U., Czuba, K. J., Billington, D. R., Kersten, P., & Siegert, R. J. (2015). Using feedback from patient-reported outcome measures in mental health services: A scoping study and typology. Psychiatric Services, 66(3), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400141.

Kuehn, B. M. (2020). Pandemic’s mental health toll grows. Journal of the American Medical Association, 324(12), 1130. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.17280.

Lambert, M. J. (2013). The efficacy and effectiveness of psychotherapy. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (6th ed., pp. 169–218). Wiley.

Lambert, M. J., Whipple, J. L., Smart, D. W., Vermeersch, D. A., Nielsen, S. L., & Hawkins, E. J. (2001). The effects of providing therapists with feedback on patient progress during psychotherapy: Are outcomes enhanced? Psychotherapy Research, 11(1), 49–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/713663852.

Lambert, M. J., Whipple, J. L., Hawkins, E. J., Vermeersch, D. A., Nielsen, S. L., & Smart, D. W. (2003). Is it time for clinicians to routinely track patient outcome? A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice, 10(3), 288–301.

Lambert, M. J., Whipple, J. L., & Kleinstäuber, M. (2018). Collecting and delivering progress feedback: A meta-analysis of routine outcome monitoring. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 520–537. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000167.

Låver, J., McAleavey, A., Valaker, I., Castonguay, L. G., & Moltu, C. (2023). Therapists’ and patients’ experiences of using patients’ self-reported data in ongoing psychotherapy processes-A systematic review and meta-analysis of qualitative studies. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2023.2222896. Advance online publication.

Lewis, C. C., Boyd, M., Puspitasari, A., Navarro, E., Howard, J., Kassab, H., Hoffman, M., Scott, K., Lyon, A., Douglas, S., Simon, G., & Kroenke, K. (2019). Implementing measurement-based care in behavioral health: A review. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(3), 324–335. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3329.

Lutz, W., Lambert, M. J., Harmon, S., Tschitsaz, A., Schurch, E., & Stulz, N. (2006). The probability of treatment success, failure and duration- what can be learned from empirical data to support decision making in clinical practice? Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 13(4), 223–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.496.

Lutz, W., Rubel, J., Schiefele, A. K., Zimmermann, D., Böhnke, J. R., & Wittmann, W. W. (2015). Feedback and therapist effects in the context of treatment outcome and treatment length. Psychotherapy Research, 25(6), 647–660. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2015.1053553.

Lutz, W., Rubel, J. A., Schwartz, B., Schilling, V., & Deisenhofer, A. K. (2019). Towards integrating personalized feedback research into clinical practice: Development of the Trier Treatment Navigator (TTN). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 120, 103438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.103438.

Lyon, A. R., Lewis, C. C., Boyd, M. R., Hendrix, E., & Liu, F. (2016). Capabilities and characteristics of digital measurement feedback systems: Results from a comprehensive eeview. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(3), 441–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0719-4.

McLeod, B. D., Jensen-Doss, A., Lyon, A. R., Douglas, S., & Beidas, R. S. (2022). To Utility and Beyond! Specifying and advancing the utility of measurement-based care for Youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology American Psychological Association Division 53, 51(4), 375–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2022.2042698.

Metz, M. J., Veerbeek, M. A., Twisk, J. W. R., van der Feltz-Cornelis, C. M., de Beurs, E., & Beekman, A. T. F. (2019). Shared decision-making in mental health care using routine outcome monitoring: Results of a cluster randomised-controlled trial. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54(2), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1589-8.

Moltu, C., Veseth, M., Stefansen, J., Nøtnes, J. C., Skjølberg, Å., Binder, P. E., Castonguay, L. G., & Nordberg, S. S. (2018). This is what I need a clinical feedback system to do for me: A qualitative inquiry into therapists’ and patients’ perspectives. Psychotherapy Research, 28(2), 250–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2016.1189619.

Østergård, O. K., Randa, H., & Hougaard, E. (2020). The effect of using the partners for Change Outcome Management System as feedback tool in psychotherapy-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 30(2), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2018.1517949.

Patterson, P., Matthey, S., & Baker, M. (2006). Using mental health outcome measures in everyday clinical practice. Australasian Psychiatry, 14(2), 133–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1665.2006.02266.x.

Pejtersen, J. H., Viinholt, B. C. A., & Hansen, H. (2020). Feedback-informed treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the partners for change outcome management system. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 67(6), 723–735. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000420.

Probst, T., Lambert, M. J., Loew, T. H., Dahlbender, R. W., Göllner, R., & Tritt, K. (2013). Feedback on patient progress and clinical support tools for therapists: Improved outcome for patients at risk of treatment failure in psychosomatic in-patient therapy under the conditions of routine practice. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 75(3), 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.07.003.

Riemer, M., & Bickman, L. (2011). Using program theory to link social psychology and program evaluation. In M. M. Mark, S. I. Donaldson, & B. Campbell (Eds.), Social psychology and evaluation (pp. 102–139). The Guilford.

Roe, D., Mazor, Y., & Gelkopf, M. (2021). Patient-reported outcome measurements (PROMs) and provider assessment in mental health: A systematic review of the context of implementation. International Journal for Quality in Health care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 34(Suppl 1), ii28–ii39. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzz084.

Rognstad, K., Wentzel-Larsen, T., Neumer, S., & Kjøbli, J. (2023). A systematic review and meta-analysis of measurement feedback s ystems in treatment for common mental health disorders. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 50(2), 269–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-022-01236-9.

Rye, M., Rognmo, K., Aarons, G. A., & Skre, I. (2019). Attitudes towards the Use of Routine Outcome Monitoring of Psychological therapies among Mental Health providers: The EBPAS-ROM. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 46(6), 833–846. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-00968-5.

Sapyta, J., Riemer, M., & Bickman, L. (2005). Feedback to clinicians: Theory, research, and practice. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(2), 145–153. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20107.

Schiepek, G. K., Stöger-Schmidinger, B., Aichhorn, W., Schöller, H., & Aas, B. (2016). Systemic case formulation, individualized process monitoring, and state dynamics in a case of dissociative identity disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1545. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01545.

Scott, K., & Lewis, C. C. (2015). Using measurement-based care to enhance any treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22(1), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.01.010.

Shimokawa, K., Lambert, M. J., & Smart, D. W. (2010). Enhancing treatment outcome of patients at risk of treatment failure: Meta-analytic and mega-analytic review of a psychotherapy quality assurance system. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(3), 298–311. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019247.

Shore, J. H., Schneck, C. D., & Mishkind, M. C. (2020). Telepsychiatry and the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic-current and future outcomes of the rapid virtualization of psychiatric care. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(12), 1211–1212. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1643.

Simon, W., Lambert, M. J., Harris, M. W., Busath, G., & Vazquez, A. (2012). Providing patient progress information and clinical support tools to therapists: Effects on patients at risk of treatment failure. Psychotherapy Research, 22(6), 638–647. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2012.698918.

Slade, K., Lambert, M. J., Harmon, S., Smart, D. W., & Bailey, R. (2008). Improving psychotherapy outcome: The use of immediate electronic feedback and revised clinical support tools. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 15(5), 287–303. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.594.

Solstad, S. M., Kleiven, G. S., Castonguay, L. G., & Moltu, C. (2021). Clinical dilemmas of routine outcome monitoring and clinical feedback: A qualitative study of patient experiences. Psychotherapy Research, 31(2), 200–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2020.1788741.

Tam, H. E., & Ronan, K. (2017). The application of a feedback-informed approach in psychological service with youth: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 55, 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.005.

Town, R., Midgley, N., Ellis, L., Tempest, R., & Wolpert, M. (2017). A qualitative investigation of staff’s practical, personal and philosophical barriers to the implementation of a web-based platform in a child mental health setting. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 17(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12129.

Unsworth, G., Cowie, H., & Green, A. (2012). Therapists’ and clients’ perceptions of routine outcome measurement in the NHS: A qualitative study. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 12(1), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2011.565125.

van Oenen, F. J., Schipper, S., Van, R., Schoevers, R., Visch, I., Peen, J., & Dekker, J. (2016). Feedback-informed treatment in emergency psychiatry; a randomised controlled trial. Bmc Psychiatry, 16(1), 110. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0811-z.

van Sonsbeek, M. A. M. S., Hutschemaekers, G. J. M., Veerman, J. W., Vermulst, A., Kleinjan, M., & Tiemens, B. G. (2021). Challenges in investigating the effective components of feedback from routine outcome monitoring (ROM) in youth mental health care. Child & Youth Care Forum, 50(2), 307–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-020-09574-1.

van Sonsbeek, M. A. M. S., Hutschemaekers, G. J. M., Veerman, J. W., Vermulst, A., & Tiemens, B. G. (2023). The results of clinician-focused implementation strategies on uptake and outcomes of Measurement-Based Care (MBC) in general mental health care. BMC Health Service Research 23, 326 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09343-5.

Van Tiem, J., Wirtz, E., Suiter, N., Heeren, A., Fuhrmeister, L., Fortney, J., Reisinger, H., & Turvey, C. (2022). The implementation of measurement-based care in the context of Telemedicine: Qualitative study. JMIR Mental Health, 9(11), e41601. https://doi.org/10.2196/41601.

Walter, G., Cleary, M., & Rey, J. M. (1998). Attitudes of mental health personnel towards rating outcome. Journal of Quality in Clinical Practice, 18(2), 109–115.

Wampold, B. E. (2015). Routine outcome monitoring: Coming of age—with the usual developmental challenges. Psychotherapy, 52(4), 458–462. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000037.

Weisz, J. R., Chorpita, B. F., Frye, A., Ng, M. Y., Lau, N., Bearman, S. K., Ugueto, A. M., Langer, D. A., Hoagwood, K. E., & Research Network on Youth Mental Health. (2011). Youth top problems: Using idiographic, consumer-guided assessment to identify treatment needs and to track change during psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(3), 369–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023307.

Wolpert, M., Curtis-Tyler, K., & Edbrooke-Childs, J. (2016). A qualitative exploration of patient and clinician views on patient reported outcome measures in child mental health and diabetes services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(3), 309–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-014-0586-9.

Wolpert, M., Vostanis, P., Martin, K., Munk, S., Norman, R., Fonagy, P., & Feltham, A. (2017). High integrity mental health services for children: Focusing on the person, not the problem. Bmj, 357, j1500. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j1500.

Youn, S. J., Boswell, J. F., Douglas, S., Harris, B. A., Aajmain, S., Arnold, K. T., Creed, T. A., Gutner, C. A., Orengo-Aguayo, R., Oswald, J. M., & Stirman, S. W. (2023). Implementation science and practice-oriented research: Convergence and complementarity. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-023-01296-5Advance online publication.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on discussions between feedback researchers during the International Network for Psychotherapy Innovations and Research into Effectiveness (INSPIRE) meetings held at Leiden University in 2017 and 2018. The authors would like to thank INSPIRE (affiliate) members Ingunn Amble, Dana Atzil-Slonim, Eran Bar-Kalifa, Björn Bennemann, Luis Costa Da Silva, Ann-Kathrin Deisenhofer, Edwin de Beurs, Chris Evans, Paulo Machado, Ole Østergård, David Saxon, Bea Tiemens, Tommy Skjulsvik, and Sabine van Thiel, who participated in these discussions and/or provided feedback on a draft of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kim de Jong organized and chaired the discussion meetings during which the manuscript was conceptualized. Kim de Jong drafted a first version of the manuscript, to which Susan Douglas, Michael Barkham, Miranda Wolpert, and Jaime Delgadillo contributed. Benjamin Aas, Bram Bovendeerd, Ingrid Carlier, Angelo Compare, Julian Edbrooke-Childs, Pauline Janse, Wolfgang Lutz, Christian Moltu, Samuel Nordberg, Stig Poulsen, Julian Rubel, Günter Schiepek, Viola Schilling, and Maartje van Sonsbeek participated in the discussion meetings and contributed to subsequent versions of the manuscript. All authors agree with the content of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Bram Bovendeerd, Ingrid Carlier, Angelo Compare, Kim de Jong, Jaime Delgadillo, Julian Edbrooke-Childs, Pauline Janse, Wolfgang Lutz, Stig Poulsen, Julian Rubel, Günter Schiepek, Viola Schilling, Maartje van Sonsbeek and Miranda Wolpert have nothing to disclose. Benjamin Aas receives a consulting fee from CCSYS in Germany, the software provider for a feedback system. Michael Barkham was a co-developer of the CORE Outcome Measure (1995-98) which has been used in feedback research. He is a CORE System Trustee but receives no financial benefit from the use of the measure. Vanderbilt University and Susan Douglas receive compensation related to the Peabody Treatment Progress Battery; and Susan Douglas has a financial relationship with MIRAH, and both are Measurement -Based Care (MBC) tools. The author declares a potential conflict of interest. There is a management plan in place at Vanderbilt University to monitor that this potential conflict does not jeopardize the objectivity of Dr. Douglas’ research. Christian Moltu and Sam Nordberg own intellectual property in the Norse feedback system. CORE, Mirah, the Peabody Treatment Progress Battery (PTPB), and Norse Feedback are not mentioned in the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Jong, K., Douglas, S., Wolpert, M. et al. Using Progress Feedback to Enhance Treatment Outcomes: A Narrative Review. Adm Policy Ment Health (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-024-01381-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-024-01381-3