Abstract

We determined whether effects of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage on trajectories of aggression were moderated or mediated by neighborhood social organization and examined sex differences in neighborhood effects for rural adolescents. We used five waves of survey data collected over 2.5 years linked with neighborhood data from interviews with parents and the US Census. The sample (N = 5,118) was 50.1% female, 52.0% white and 38.3% African–American; average age at baseline was 13.1 years. Multilevel growth curve models for both girls and boys showed no significant interactions between neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and indicators of social organization. Neither sample showed evidence of mediated effects. In main effects models, neighborhood disadvantage was associated with the average aggression trajectory for girls. For boys, the effects of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and social disorganization appeared to be confounded with each other. Neighborhood disadvantage is detrimental for rural girls regardless of the level of social organization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Neighborhood characteristics such as socioeconomic disadvantage and social disorganization adversely impact many types of adolescent health risk behaviors, including sexual activity (Upchurch et al. 1999), school dropout (Crowder and South 2003), substance use (Chuang et al. 2005) and aggression (Ingoldsby and Shaw 2002; Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2000). To understand how the neighborhood context influences youth in rural areas, we examined the impact of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and neighborhood social organization on trajectories of aggression perpetrated by girls and boys ages 11–18 living in predominantly rural areas in the southeastern United States (US). We investigated whether the detrimental effect of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage was buffered by social organization, whether the effect of disadvantage was mediated by social organization, or whether the two dimensions of the neighborhood environment had independent, additive effects on the development of aggression during adolescence.

The Importance of the Neighborhood Context

Social contexts that influence child and adolescent development include families, peer groups, schools and neighborhoods. The proximal contexts of families and peers are embedded in, and interact with, the neighborhood environment (Bronfenbrenner 1979, 1986), but neighborhoods also may have independent effects on their residents. Neighborhoods represent both physical and social environments: they offer basic infrastructure and resources for education and growth, and they provide important social support systems, bonding opportunities and socialization structures for adolescents. The physical and social resources can impact residents directly or indirectly through family processes, peer groups or school structures. Although the functions of family, peer and school environments have received much attention, fewer studies have examined neighborhood effects on adolescent development, particularly in rural areas. In this study, we operationalize the neighborhood physical environment in terms of the infrastructure and resources that are available to support healthy development, using a measure of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage based on block group data from the US Census. To capture dimensions of the neighborhood social environment that may impact aggression during adolescence, we include two measures of social organization: social bonds between adults and neighborhood social control processes based on interviews with adult residents in the neighborhood. The theories that guided our selection of neighborhood indicators are explicated in the section that follows.

Theories of Neighborhood Effects

Theories of social exclusion (Kramer 2000) and models of institutional resources (Jencks and Mayer 1990) emphasize the neighborhood socioeconomic context as an important determinant of child and adolescent development. As described by Wilcox (2003) and Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn (2000), neighborhood resources such as schools, recreation facilities and libraries provide opportunities for supervision and social control, as well as for healthy learning and development. Socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods are characterized by low levels of educational attainment, high unemployment rates and high poverty levels (Wagle 2002; Wilson 1987). Neighborhoods represent more than mere aggregations of individuals with these characteristics, however. Disadvantaged areas provide limited resources for healthy development due to restricted exposure to cultural and intellectual capital (Lynch and Kaplan 2000) and exclude residents from the social institutions that promote conventional behavior (Kramer 2000). For example, in a disadvantaged area characterized by high levels of unemployment, a lack of job opportunities may be an impetus for the development of underground or informal economic activity to replace formal employment structures. Such activity may be associated with health risks related to violence or incarceration, particularly for young residents. Due to its concentrated nature, neighborhood disadvantage thus may impact all residents, regardless of the level of disadvantage (or advantage) experienced by individual families (Wilcox 2003). Many studies have shown that neighborhood disadvantage increases youth violence and aggression in both urban (Farrington 1998; Loeber and Hay 1997; Sampson et al. 2005) and rural (Stewart et al. 2002) communities.

Social organization involves the ability of a neighborhood to mobilize residents to solve problems and regulate behavior (Bursik 1988). Collective socialization models (Jencks and Mayer 1990; Sampson et al. 2002; Wilcox 2003) and social control theories (Kramer 2000) delineate the means by which social organization may affect adolescent risk behaviors. Collective socialization models posit that problematic behaviors of both adults and youth can be discouraged through informal social control processes enacted by the adults in a neighborhood (Wilcox 2003). Such social controls include casual surveillance and active enforcement of acceptable norms of behavior (Bursik 1988), which typically are implemented by family members, neighbors and other community residents (Kramer 2000). Furthermore, these models specify that social bonds between members of a neighborhood can enhance the social control processes that deter deviance (Osgood and Chambers 2000; Sampson et al. 2002). In this study, we include both social bonds between adults and effective social control processes as indicators of neighborhood social organization; each has the potential to discourage youth aggression and violence (Pratt and Cullen 2005; Ross and Jang 2000; Sampson et al. 1997).

Relationships Between Neighborhood Disadvantage and Social Organization

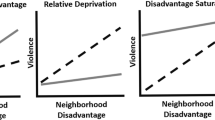

Although theories of neighborhood effects describe direct pathways of influence on the development of young residents, neighborhood disadvantage and social organization also may operate together. Sampson et al. (1997), for example, posited that neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage impacts community violence through a negative association with social organization processes that deter antisocial behaviors. Using data from neighborhoods in Chicago, they found that the effects of neighborhood disadvantage on violence were substantially reduced when indicators of social organization were included in their statistical models. This suggests a mediation, or indirect effects, model of neighborhood effects, which has been supported in other studies as well (Elliott et al. 1996; Simons et al. 2004). In contrast, some researchers have suggested a moderation model such that the influence of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage on adolescent development varies depending on the social processes in the neighborhood (Duncan and Aber 1997; Duncan et al. 1997; Ginther et al. 2000; Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2000).

Only a few studies have included explicit assessment of the interaction between neighborhood social organization and socioeconomic disadvantage. Although the main effects of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and social organization on crime and juvenile arrest rates appear to be similar in rural and urban settings (Lee et al. 2003; Osgood and Chambers 2000), studies of neighborhood-level moderation suggest profound differences in the effects of interactions between socioeconomic disadvantage and social organization in rural and urban settings. Two studies examining moderation effects in urban neighborhoods found that social organization exacerbated, rather than buffered, the impact of socioeconomic disadvantage. Caughy et al. (2003) found that strong social bonds among adults in disadvantaged areas increased internalizing behaviors among young children, whereas in socioeconomically advantaged areas, social organization was protective. Similarly, Warner and Rountree (1997) found that the effect of neighborhood poverty on violent crime in urban areas with high levels of residential stability and social organization was amplified when compared to poverty’s effect in areas with lower levels of social organization.

In contrast, some authors speculate that rural communities, particularly small farming towns and residentially-stable communities, may develop high degrees of social organization that can be called upon to counteract periods of individual- or community-level economic hardship (Barnett and Mencken 2002). Indeed, studies conducted in rural areas or with samples that have included nonmetropolitan areas have shown that social organization can buffer the effect of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage. Barnett and Mencken (2002) found that rates of socioeconomic disadvantage were weakly associated with rates of violent and property crime in counties that had high levels of social organization resulting from residential stability, but more strongly associated in the disorganized and unstable areas. In a multilevel analysis, Brody et al. (2001) showed that adolescents’ affiliation with deviant peers was reduced in poor neighborhoods with high levels of social control when compared to poor neighborhoods without active social control processes. With few similar studies in the existing literature on youth development, an important contribution of our study is the explication of the patterns of neighborhood influence on youth aggression in rural communities.

Aggression Trajectories as Outcomes

Most studies of neighborhood effects on youth development have been cross-sectional or examined only short-term impacts on behavior (Shulruf et al. 2007). Longitudinal studies can describe patterns of change (or trajectories) and illuminate factors that influence typical developmental trajectories over the course of adolescence. In this study, we used multilevel growth curve models to examine neighborhood effects on the development of aggression from ages 11 to 18 in a sample of rural adolescents. These models allowed us to examine the influence of the neighborhood characteristics—including direct, indirect and interaction effects—on the initial levels of aggression at the starting point of the trajectory, the rates of change in the behavior over time, and for curvilinear trajectories, the peak ages of aggression, or the point at which desistance from aggression begins.

Several studies have shown that the average trajectories of aggression (Aber et al. 2003; Farrell et al. 2005) and violence (Sampson et al. 2005) during adolescence are curvilinear, with aggression increasing during early adolescence and then decreasing into young adulthood. Youth in urban areas typically have higher rates of involvement in physical aggression and violence than their rural peers (Farrell et al. 2005), but trajectory studies reveal curvilinear patterns of physical aggression and violence for both urban and rural youth (Farrell et al. 2005). In general, problematic developmental trajectories display high initial levels of and late peak ages of involvement in, or delayed desistance from, antisocial behaviors such as aggression (Moffitt 1993; Nagin 1999; Nagin and Tremblay 2001).

Although no studies have examined whether social organization buffers the effects of neighborhood disadvantage on trajectories of aggression, Sampson et al. (2005) found significant main effects for both neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and social organization on average trajectories of violence in late adolescence and early adulthood. Other researchers have found that high levels of disadvantage (Howell and Hawkins 1998) and low levels of social organization (Chung et al. 2002) predict membership in trajectory groups displaying high initial levels and late peak ages of aggression and violence. All of these studies were conducted with urban samples. Our study examines the influence of rural neighborhoods’ socioeconomic status and levels of social organization on trajectories of aggression utilizing a developmental perspective.

Sex Differences in Development and Neighborhood Effects

Due to developmental differences during adolescence, we examined neighborhood influences on the aggression trajectories separately for girls and boys. Although trajectory studies reveal curvilinear patterns of physical aggression and violence for both boys and girls (Farrell et al. 2005; Sampson et al. 2005), boys typically have higher rates of involvement in physical aggression and violence than girls (Blitstein et al. 2005; Farrell et al. 2000; Fergusson and Horwood 2002; Loeber and Hay 1997). Girls exhibit a later age of onset than boys for most physically aggressive behaviors (Connor 2002; Fergusson and Horwood 2002; Loeber and Hay 1997), and sex differences in aggression become more extreme throughout puberty, as boys typically continue involvement in aggression after girls have begun the process of desistance (Fergusson and Horwood 2002; Loeber and Hay 1997).

In addition to differences in aggression during adolescence, the impact of the neighborhood environment—particularly the socioeconomic context—on behavior also may vary for girls and boys (see Ingoldsby and Shaw 2002; Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2000, for reviews). Although no studies have explicitly examined sex differences in neighborhood influences on aggression, studies of other health risk behaviors and adolescent academic achievement suggest that the neighborhood socioeconomic context may be more important for boys’ development than girls’ (Beyers et al. 2003; Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2003; Ramirez-Valles et al. 2002). Most studies of neighborhood effects have not included rural adolescents, so it is unclear whether the effects of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and social disorganization will differ for the boys and girls in our rural sample.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

We examine whether detrimental effects of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage on adolescent aggression are buffered by social organization, whether the effects of neighborhood disadvantage are mediated by social organization, or whether the two dimensions of the neighborhood context have independent effects on adolescent aggression. Based on the results from other rural studies of neighborhood effects (Barnett and Mencken 2002; Brody et al. 2001), we expect neighborhood social organization to buffer the negative effects of living in a socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhood on the development of aggression from ages 11 to 18. We hypothesize that this effect will be reflected in lower initial levels of aggression and earlier peak ages of involvement for both girls and boys in disadvantaged neighborhoods that had high levels of social organization. In the case of mediated effects, we expect the influence of neighborhood disadvantage on the trajectories to be substantially reduced in models including indicators of social organization (Baron and Kenny 1986; Frazier et al. 2004). Finally, in the event of independent effects of disadvantage and social organization, we expect higher initial levels and later peak ages in disadvantaged neighborhoods and lower initial levels and earlier peak ages in socially organized neighborhoods. The only sex difference anticipated is a stronger influence of neighborhood disadvantage on the boys’ aggression trajectories when compared to the girls’ in main effects models.

Methods

Study Design

The data for this study come from the Context of Adolescent Substance Use Study, which was designed to investigate contextual influences on adolescent substance use and aggression, with a focus on peer networks, family characteristics and neighborhood factors (Ennett et al. 2006). The present analysis includes data on aggression from surveys conducted with adolescents from all public schools in three counties in North Carolina, data about neighborhood social organization from telephone interviews conducted with a randomly sampled cohort of parents, and data on neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage from the US Census. The Public Health Institutional Review Board at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill approved the study protocols.

The surveys were conducted with adolescents in their schools every 6 months between spring 2002 and spring 2004, beginning when the students were in sixth, seventh or eighth grade (in 13 different schools) and ending when they were in eighth, ninth or tenth grade (in 19 different schools). At each wave, all adolescents in the public schools were eligible for participation (approximately 6,100 students) except those who could not complete the questionnaire in English (approximately 15 students) and those who were exclusively in special education programs (approximately 300 students). Parents were notified about the study and had the opportunity to refuse consent for their child’s participation at the beginning of each academic year and whenever a new student became eligible for the study. Trained research assistants administered questionnaires on at least two different occasions at each school to allow those students who had been absent on the primary day of data collection to participate in the study. To maintain confidentiality, teachers remained at their desks while the students completed their questionnaires, and the students placed their questionnaires in envelopes before returning them to the data collectors. The average response rate across the five waves of data collection was 81.1%.

A random sample of parents was selected to complete a telephone interview that corresponded with the first wave of the student survey. A parent was eligible if their child had completed a Wave 1 questionnaire, they had only one child in the school-based study and they could complete the interview in English (N = 2,062). Trained interviewers first attempted to reach each adolescent’s mother or an adult female living with the adolescent, and if no mother figure could be identified, the father or an adult male living with the adolescent completed the interview. Interviews lasted approximately 25 min, and all participating parents received $10. During the spring and summer of 2002, 1,663 parents (80.7%) completed the Wave 1 interviews.

Neighborhoods were defined by US Census block group boundaries, because studies have found that US census block groups effectively delineate social and structural determinants of health and health behavior (Cook et al. 1997; Krieger et al. 2002). To obtain the block group geocodes, student and parent addresses collected during Wave 1 were sent to a commercial geocoding firm. (The parent addresses were geocoded to permit the linkage of parent-report data on neighborhood social organization with the students’ data.) The returned geocodes varied in precision from exact street matches to 5-digit ZIP centroid matches. Addresses that were not exact street matches were cleaned and checked using the US Postal Service website (U.S. Postal Service 2005) and a general address mapping website (MapQuest 2005), and additional attempts were made to geocode them using ArcGIS software (ESRI 2005) and the US Census American FactFinder website (U.S. Census Bureau 2005). The geocoding success rate was 99.6% for the student addresses and 100% for the parent addresses. Following the recommendations of Krieger et al. (2001), we conducted a study to test the accuracy of the commercial and ArcGIS geocoding results for a random sample of exact street matches, stratified by county. Results indicated that 90.4% of the addresses checked for accuracy matched the recommended gold standard (i.e., matches returned by the US Census American FactFinder website).

Analysis Sample

The analysis sample (N = 5,118) includes those adolescents who completed a Wave 1 questionnaire, except for those who were younger than 11 or older than 16.5 at Wave 1 (n = 26), those who did not give their birth date or sex on any of the questionnaires (n = 8), those without a neighborhood block group geocode (n = 35), and those who were the only respondent from their neighborhood (n = 33). The age restriction was imposed to limit the number of students who were out of the typical age range for their grade, and we limited the analyses to neighborhoods containing more than one student to increase the stability of the estimates.

Overall response rates for the analysis sample ranged from 86.6% at Wave 2 to 79.5% at Wave 5. Of the students in the sample, 56.0% participated in the study at all five waves, 15.6% participated in four waves, 15.1% in three waves, 5.3% in two waves only and 8.0% only at Wave 1. Girls and those students who were white, from two-parent households or who had parents with more than a high school education completed more waves of data collection than their peers. Procedures for imputing missing survey data are described below.

At Wave 1, the majority of students (95.6%) were between the ages of 11 and 14 (M = 13.1 years). Half (50.1%) of the students were females, 52.0% were white, 38.3% were black or African–American, 3.8% were Hispanic or Latino, and 5.9% were another race or ethnicity. Most students (80.0%) indicated that they lived with two parents (biological or step-parents), and 73.0% reported that at least one parent had attended college, community college or technical school. At Wave 1, approximately half of the students had perpetrated aggression (45.6% of girls and 51.8% of boys). Over the course of the study, less than 10% of the students moved to a different neighborhood.

The neighborhoods in the sample included all of the 113 block groups in the three-county area. A small group of neighborhoods (1.2%) were located in counties outside the target area, resulting in a total sample of 128 neighborhoods. There were between 2 and 63 students and between 2 and 39 parents in each neighborhood. According to the US Census (2002), the neighborhoods ranged in size from 461 to 3,581 people (M = 1,566, SD = 620). The neighborhoods were located in counties classified as nonmetropolitan areas with access to an interstate highway (Ricketts et al. 1999). The counties also had greater proportions of African–Americans (M = 28%) than the general US population (12%), and the median household income (M = $36,600) and median housing value (M = $89,400) were lower than the national medians ($42,000 and $111,800, respectively; U.S. Census Bureau 2002). In relation to other rural areas in the US, the proportions of African–Americans were substantially higher than those seen in rural areas outside of the South Atlantic states (6%), and the median household income was lower than that of other rural areas outside of the Southern region ($43,000; U.S. Census Bureau 2002).

Measures

Aggression

Aggression was measured at all five waves. The aggression scale assessed how many times in the past 3 months the respondent had been in a fight in which someone was hit, hit or slapped another kid, threatened to hurt a teacher, and threatened someone with a weapon (Farrell et al. 2000). The response options for each item were none (0), 1–2 times (1), 3–5 times (2), 6–9 times (3), or 10 or more times (4). The responses were summed to form a continuous total score (range: 0–16 for all waves), such that higher scores indicated higher levels of aggression. To adjust for skewness, the total aggression scores were log-transformed after adding a constant. Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .68 at Wave 1 to .86 at Wave 5. Aggression varied from a low at Wave 1 (M = 1.05, SD = 1.68 for girls; M = 1.49, SD = 2.31 for boys) to a high at Wave 3 (M = 1.18, SD = 2.08 for girls; M = 1.81, SD = 3.18 for boys). The aggression scale was correlated with variables associated with aggression, such as depression (r = .23 for girls; r = .24 for boys), family conflict (r = .19 for girls; r = .17 for boys), a belief in conventional values (r = −.32 for girls; r = −.38 for boys) and religious engagement (r = −.14 for girls; r = −.13 for boys), supporting validity of the aggression scale.

Neighborhood Variables

The neighborhood data came from two sources: the 2000 US Census (U.S. Census Bureau 2002) and parents’ perceptions of the neighborhoods (gathered during the Wave 1 telephone interviews). All neighborhood-level covariates were grand-mean centered, so that the intercept and slope terms represent the averages across neighborhoods (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002; Singer 1998). Because we used sex-stratified data in the analyses, the grand means were calculated separately for girls and boys. Correlation coefficients between the neighborhood variables and aggression are shown in Table 1.

Neighborhood Socioeconomic Disadvantage

Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage was calculated using US Census data, and it encompassed three dimensions based on the work of Deane and Shin (2002) and Krieger et al. (2002): education (percentage of people aged 25 and older with less than a high school education), employment (percentage of people aged 16 or older in the labor force who were unemployed and the percentage of people aged 16 or older who held working-class or blue-collar jobs) and economic resources (percentage of people living below the federally-defined poverty threshold, percentage of households without access to a car, and percentage of renter-occupied housing units). Cronbach’s alpha for the six items was .88 for the study sample. A mean socioeconomic disadvantage score was calculated for each neighborhood (M = 25.34, SD = 8.52; with grand-mean centered values of M = −0.02, SD = 8.71 for girls; M = 0.03, SD = 8.54 for boys), and each student was assigned their neighborhood average, with higher scores indicating higher levels of socioeconomic disadvantage.

Neighborhood Social Organization

Neighborhood social organization was represented by two variables: neighborhood social bonding and social control. To construct the measures, each student in the sample was linked with the parent-report data on social organization for their neighborhood block group. To minimize possible biases associated with the demographic composition of the neighborhoods, we calculated the values for the parent reports of neighborhood social organization using a latent variable approach (Raudenbush 2003). We conducted principle components analyses of the items on each scale, extracted factor scores for each parent respondent, and used the factor scores in a mixed model that accounted for each respondent’s demographic characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, level of education, homeowner status and logged length of residence in the home) to determine the average level of the two components of social organization in each neighborhood (Raudenbush 2003; Sampson and Raudenbush 2004).

Neighborhood Social Bonding

Parents responded to four items based on the work of Parker et al. (2001) to indicate how often in the past 3 months they had socialized with one or more neighbors, asked one of their neighbors for help, talked to a neighbor about personal problems, or gone out for a social evening with a neighbor. Responses included never, once or twice, two or three times, or four or more times and were scored from 1 to 4. Cronbach’s alpha at the individual level was .75 at Wave 1 (M = 1.97, SD = 0.76; with grand-mean centered values of M = 0.00, SD = 0.06 for both girls and boys). High scores indicate greater social bonding among adults in the neighborhood.

Neighborhood Social Control

Parents responded to six items about the degree of social control in their neighborhood (Sampson et al. 1997). They indicated how likely it is that neighbors would step in and do something if teens were damaging property, teens were showing disrespect to an adult, a fight broke out in front of someone’s house, teens were hanging out and smoking cigarettes, teens were hanging out and drinking alcohol, and teens were hanging out and smoking marijuana. Responses ranged from 1 (very unlikely) to 4 (very likely). Cronbach’s alpha at the individual level for these six items was .91 at Wave 1 (M = 3.51, SD = 0.71; with grand-mean centered values of M = 0.00, SD = 0.21 for girls; M = 0.00, SD = 0.22 for boys). High scores indicate effective social control processes in the neighborhood.

Control Variables

The control variables included race/ethnicity, parent education, family structure, the number of times the student moved across the five waves of data collection, the type of address geocoded and the precision of the geocode. We determined values for the demographic control variables based on all available data across the five waves of surveys. The child’s self-reported race or ethnicity was based on the modal response across all waves, and it was represented by three mutually-exclusive dummy variables (black or African–American, Hispanic or Latino, or other race/ethnicity) with white as the reference category. Parent education was measured by three mutually-exclusive dummy variables representing the highest level of education attained by either parent (some 2- or 4-year college or technical school, graduated from 2- or 4-year college, and graduate or professional school after college) with a high school diploma or less as the reference group. Family structure was a dichotomous variable indicating residence in a single-parent household at any time during the study (1) compared to continuous residence in a two-parent household (0). A dichotomous variable represented the type of address geocoded (P.O. Box = 1; street address = 0). The degree of precision of the geocode match ranged from a 5-digit ZIP Code centroid match (0) to a street-level match (2). The analyses also controlled for the number of times the student moved to a different neighborhood during the five-wave study, with higher numbers representing more moves.

We modeled aggression as a function of chronological age, which was calculated based on the modal birth date (using the modal month, modal day and modal year) for all available waves of data. It was centered by subtracting 11 (the youngest age in the sample at Wave 1) so that the intercepts could be easily interpreted.

Analysis Strategy

Missing values (both within and between waves) were replaced using multiple imputation procedures (Rubin 1987). We used SAS PROC MI (SAS Institute 2003) to impute ten sets of missing values using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo specification (Yuan 2000) with a missingness equation specified to impute the dependent and independent variables at all five waves, using information from variables highly correlated with the outcomes from all five waves, variables containing special information about the sample and other variables thought to be associated with missingness (Allison 2000; Horton and Lipsitz 2001). We confirmed that the variables used in the imputation were not collinear using eigenanalysis (Belsley et al. 1980) and by examining variance inflation factors (Neter et al. 1990). We bounded the imputed values to the valid ranges of the data, and we allowed all imputed dichotomous variables to range between 0 and 1 rather than rounding the values (Allison 2005).

We used multilevel growth curves to model the aggression trajectories between ages 11 and 18. The data were stratified by sex and parallel analyses were conducted for each stratum. All analyses were conducted using PROC MIXED in SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute 2003) using a restricted maximum likelihood estimation process and the Kenward-Roger adjustment of the standard errors and degrees of freedom for more conservative tests of the fixed effects (Kenward and Roger 1997). The analysis results were combined across the ten imputed datasets using SAS PROC MIANALYZE (Horton and Lipsitz 2001), which accounts for the uncertainty of the imputation process when calculating summary test statistics, parameter estimates and standard errors. Because the MIANALYZE procedure does not include the covariance parameters from mixed models, we combined the covariance parameters from the ten imputed datasets using the formulas provided by Rubin and Schafer (1997). All models had relative efficiencies greater than .95, which suggests that ten imputations was sufficient to achieve stable estimates (Horton and Lipsitz 2001).

Model Specification

The basic multilevel growth curve model can be specified as:

The level-1 model (1) denotes change over time within individuals. In this study, Y tij represents the observed aggression score at age t for child i in neighborhood j, and it is a function of a quadratic curve plus random error (e tij ). Thus, π 0ij is the total aggression score of child ij at age 11, π 1ij is the linear slope for child ij , and π 2ij is the quadratic slope for child ij .

The level-2 models (2) denote differences between individuals within neighborhoods, and they are used to predict the parameters from the level-1 model. For this study, β p0j is the intercept for neighborhood j in modeling the child effect π pij , where X qij is one of the Q p individual-level control variables characteristic of child i in neighborhood j. β pqj represents the effect of X qij on the pth growth parameter, and r pij is the random effect for each child. Based on preliminary analyses (not shown), we allowed the demographic control variables (race/ethnicity, parent education and family structure) to predict the intercept and the linear slope, but not the quadratic slope, from the level-1 model. The geocoding control variables (type of address geocoded, precision of the geocode match and the number of times the student moved during the study) only predicted the level-1 intercept. All effects of the level-2 control variables were fixed (not random).

The level-3 models (3) denote differences between neighborhoods, and they are used to predict the parameters from the level-2 models. Each β pqj is predicted by the neighborhood-level characteristics, where γ pq0 is the intercept in the neighborhood-level model for β pqj , W sj is a neighborhood characteristic used as a predictor for the neighborhood effect on β pqj , γ pqs is the level-3 coefficient that represents the direction and strength of the association between neighborhood characteristic W sj and β pqj , and u pqj is a random effect for each neighborhood. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage, two variables representing neighborhood social organization, and the interaction between socioeconomic disadvantage and each of the social organization variables were specified as predictors of the intercept and linear and quadratic slopes from the level-2 model, which resulted in fixed effects for the main effect of each neighborhood term on the intercept and for the interactions between each neighborhood term and age and age-squared.

The analyses used sex-stratified data, and the random effects in the models for girls and boys differed slightly. At the individual level (level-2), the random effects indicate variability of individual trajectories. At the neighborhood level, the random effects indicate the level of variability across the different neighborhoods in the sample. We included three random effects in the models for girls (individual intercept, individual linear slope and neighborhood intercept), and we allowed the level-2 random effects to correlate. The neighborhood random effect in the boys’ data was at or near zero, so we included two random effects in the final models for boys (individual intercept and individual linear slope only), which were allowed to correlate.

Bivariate Relationships

For descriptive purposes, we calculated bivariate correlation coefficients between time-varying values of aggression and the Wave 1 neighborhood variables combined across the ten imputed datasets. We confirmed the bivariate relationships using a series of growth curve models testing the unadjusted effects of each neighborhood variable on the aggression trajectories.

Unconditional Models

Before testing the hypotheses using conditional models, we used unconditional models to describe the average aggression trajectories for girls and boys between ages 11 and 18. To be consistent with prior research on adolescent aggression, we modeled aggression as a function of chronological age, including a quadratic term, using sex-stratified data. Because we specified quadratic models, we obtained the peak age of involvement in aggression from the first derivative using a ratio of the regression coefficients (−B age/2B age-squared), using a Taylor series approximation (the delta method) to obtain the standard error of the estimated peak age (Sen and Singer 1993).

Conditional Models

Before testing the moderation hypotheses, we described the main effects of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage, social bonding and social control on the girls’ and boys’ aggression trajectories. The conditional models included one neighborhood predictor, interactions of the neighborhood variable with age and age-squared (to indicate effects on the linear and quadratic slopes, respectively), and the individual-level control variables as predictors of aggression. These models were simplified by performing a test of significance at the .05 level for each of the product terms involving a neighborhood variable with age or age-squared; interaction terms that were not significant were removed from the models.

Conditional models also were used to determine whether neighborhood social organization moderated the relationship between neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and aggression trajectories. All moderation terms were entered into the model simultaneously, and the variables were evaluated in blocks assessing main effects of the neighborhood predictors on the trajectory intercepts, moderation effects on the intercepts, main effects on the linear and quadratic slopes, moderation effects on the linear slopes, and moderation effects on the quadratic slopes. Using multivariate F-tests to limit the overall Type 1 error level to .05, the conditional models were simplified using backwards elimination to remove any blocks that were not statistically significant so that the remaining terms could be easily interpreted. Additional models to assess an alternative mediation model were unnecessary, as the conditions for mediation (significant effects of disadvantage and social organization on the trajectories and a reduction of the effect of disadvantage on the trajectories when accounting for social organization; Baron and Kenny 1986; Frazier et al. 2004) could be ascertained using the main effects and combined models described above.

Results

As shown in Table 1, each of the neighborhood characteristics was significantly associated with aggression in the direction expected in bivariate models. For both girls and boys, neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage was positively associated with aggression, and neighborhood social bonds and social control were negatively associated with aggression, although the correlation coefficients were quite small. These results were replicated in the series of growth curve models testing the unadjusted effects of each neighborhood variable on the aggression trajectories (data not shown). The correlation coefficients also showed that neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage was negatively associated with neighborhood social bonds and social control.

The sex-stratified unconditional models are presented in Table 2, and the average aggression trajectories are depicted in Fig. 1, with the predicted values presented on the original scale of the aggression measure rather than on the logarithmic scale. A score of 1 (as seen at the peak of the boys’ trajectory) would correspond to one to two acts of aggression being perpetrated in the past 3 months. The trajectories were curvilinear for both girls and boys, with initial increases in aggression followed by declines after age 14.6 for girls and after age 15.2 for boys. For girls, the proportion of the variance in aggression that occurred between neighborhoods (the intraclass correlation) was 7.6%; the proportion of the variance in aggression that occurred between individuals was 51.0%. For boys, 100% of the variance in aggression occurred between individuals, as the unconditional models for boys did not include a random neighborhood effect (as noted above).

Individual neighborhood main effects models, controlling for demographic and geocoding characteristics, are presented in Table 3. All of the final reduced models were main effects models, with no significant interactions between any of the neighborhood variables and age-squared or age, indicating that there were no significant effects of the neighborhood variables on the slopes of the aggression trajectories. Thus, any significant neighborhood terms indicate an effect on the initial levels of aggression that was maintained at all ages included in the trajectory. For girls, we found that neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage was associated with higher levels of aggression at all ages, with the shapes of the aggression trajectories being the same across different levels of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage. That is, the trajectories were parallel, and at all ages girls in more disadvantaged areas perpetrated more aggression than girls in less disadvantaged areas. For boys, when examined independently, neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage was significantly (p = .05) and neighborhood social bonding was marginally (p = .09) associated with higher levels of aggression at all ages.

The results of the analyses testing for moderation are presented in Table 4. As in the individual neighborhood models, there were no significant interactions between any of the neighborhood moderation or main effect terms with age-squared or age, so any significant neighborhood terms indicate an effect on the initial levels of aggression that was maintained at all ages in the trajectory. As shown in the moderation models, none of the interactions between neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and the two indicators of neighborhood social organization were statistically significant for either girls or boys. Thus, there was no support for the hypothesis that social organization buffers the effects of neighborhood disadvantage on the aggression trajectories. As in the individual main effects models, the combined main effects models indicate that neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage was positively associated with initial levels of aggression for girls when controlling for levels of neighborhood social organization and the girls’ demographic characteristics. Figure 2 presents the average aggression trajectories for girls at three levels of neighborhood disadvantage: the most disadvantaged neighborhoods, the average level of neighborhood SES, and the least disadvantaged neighborhoods. In this figure, a score of 1 (as seen in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods at the peak of the trajectory) corresponds to one to two acts of aggression being perpetrated in the past 3 months. Neither of the indicators of neighborhood social organization were significant predictors of the girls’ aggression trajectories, and none of the neighborhood risk factors were associated with aggression trajectories for boys in the combined main effects models. There was no evidence of mediation for either girls or boys, as the possible mediators (social bonds between adults and social control) were not associated with the aggression trajectories in the combined main effects models. Additionally, the effect of neighborhood disadvantage on the girls’ trajectories was not reduced once social organization was accounted for in the models. That neither disadvantage nor social bonding was associated with the boys’ aggression trajectories in the combined models suggests that their effects may have been confounded by the presence of the other neighborhood variables.

To confirm the statistical significance of the sex differences from the combined models, we conducted a final analysis using unstratified data to test for interactions of sex with the three neighborhood predictors. These models, which included a random neighborhood intercept, showed a significant interaction between sex and neighborhood disadvantage [t(954) = −2.70, p = .007 (one-tailed)], indicating a significant reduction in the coefficient for disadvantage for boys as compared to girls. Neither of the interactions of sex with social bonds [t(3,620) = −0.42, p = .67 (one-tailed)] or with social control [t(1,313) = −0.72, p = .47 (one-tailed)] were statistically significant.

Discussion

This study used multilevel growth curve models to document sex differences in the influence of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and social organization on the trajectories of aggression of rural adolescents. Similar to the trajectory patterns documented for adolescents in urban areas (Aber et al. 2003; Farrell and Sullivan 2004; Farrell et al. 2005; Sampson et al. 2005), the unconditional models showed that perpetration of aggression followed curvilinear trajectories from ages 11 to 18 for both girls and boys, with the highest levels of aggression between ages 13 and 15.

There was no support for the hypothesis that social organization buffers the negative effects of socioeconomic disadvantage on the aggression trajectories for either girls or boys. We did find a significant positive relationship between neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and initial levels of aggression perpetrated by girls, and the effect of disadvantage on aggression perpetrated by girls persisted at all ages examined in our study. We did not find evidence that neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage was associated with trajectories defined by late peak ages of involvement in aggression; instead, the aggression trajectories of girls in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods showed declines in aggression at the same age as their peers in high socioeconomic status neighborhoods. Other longitudinal studies have found that the neighborhood socioeconomic environment affects the age of onset of violence, with early onset more likely in disadvantaged neighborhoods (Loeber and Hay 1997; Molnar et al. 2005). It may be that traditional gender roles help to inhibit perpetration of aggression by most rural adolescent girls, but that disadvantaged neighborhoods create an environment in which aggression by girls is more acceptable (Oberwittler 2007).

In contrast to the results for girls, and contrary to findings from other studies (Aneshensel and Sucoff 1996; Bellair et al. 2003; Beyers et al. 2003; Ingoldsby and Shaw 2002), we did not find a consistent relationship between neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and aggression perpetrated by boys. Once the models accounted for levels of social organization in the neighborhood, the significant positive relationship between neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and initial levels of aggression perpetrated by boys disappeared. Although our findings contrast with studies conducted in urban areas of the US, the results are similar to those of a German study of rural adolescents (Oberwittler 2007). In rural communities in the southeastern US, aggressive behavior by boys may be more widely accepted in a variety of neighborhoods. Further studies to replicate these findings in rural communities would be informative.

Because the indicators of social organization were not significant predictors of the boys’ aggression trajectories when neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage was included in the models, it is likely that the effects of neighborhood socioeconomic status and social organization on boys’ behavior were confounded. It is not clear, however, why this confounding would exist for boys but not for girls, since the bivariate correlations between the neighborhood variables were similar, although quite small, for both groups. Research with early adolescents generally suggests that correlations between variables such as neighborhood socioeconomic status and antisocial behaviors, such as aggression and other externalizing behaviors, generally fall between .10 and .25 (Ingoldsby and Shaw 2002), which are larger than the correlations observed in our sample. This suggests that other factors such as neighborhood norms about deviance (Sampson et al. 2005), school and peer characteristics, or family factors may be more important determinants of the behavior of the rural boys in our sample.

In addition to confounding of neighborhood effects, the weak relationship between social organization and aggression in our study relative to others could be due to differences between urban and rural neighborhoods or our measures of social organization. With respect to the first possibility, longitudinal studies using urban samples have shown that low neighborhood social organization increases the likelihood that adolescents will exhibit an aggression trajectory that shows early onset and increases in aggression over time (Farrington 1998; Howell and Hawkins 1998). It is possible that neighborhood social processes are not as strongly related to adolescents’ outcomes in predominantly rural environments because the residents are more geographically distant from one another.

With regard to our measures, we used aggregated data from parent reports of neighborhood social organization to assess social control and social bonds between adults. Although there are strengths to using parent reports, as described below, perhaps adolescents’ perceptions of neighborhood social control or social bonds are more relevant predictors of developmental outcomes such as aggression than parents’ reports of the same social phenomena (Byrnes et al. 2007). Adult and adolescent residents of the same neighborhood may conceptualize the relevant boundaries and characteristics of the area differently as well (Nicotera 2007), which could result in a disconnect between youth behavior and parental reports of neighborhood social processes. It also may be that other measures of social organization, such as a composite measure of collective efficacy (typically measured in terms of both social control processes and social cohesion or trust among residents; Sampson et al. 1997), would be more strongly related to aggression. In some cases, strong social networks may include deviant neighbors, which could decrease the social control function of social bonds (Pattillo 1998). Thus, more effective measures of neighborhood social bonds also may need to include information on the composition of social networks in addition to the presence and strength of bonds with neighbors.

Methodological strengths of the study include the large and demographically diverse adolescent sample, high response rates for the in-school surveys and parent interviews; a high geocoding match rate; and imputation of missing data to minimize attrition effects. In addition, we used both US Census data and self-report data from a random sample of parents to describe the neighborhood context to avoid same-source bias (Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn 2000; Raudenbush and Sampson 1999). The neighborhood self-report measures were adjusted for biases associated with the demographic characteristics of the parent respondents (Raudenbush 2003; Raudenbush and Sampson 1999) to limit the influence of compositional factors on the estimation of the neighborhood effects (Oakes 2004), and the reliability of the neighborhood measures also was very high. We also controlled for several factors that may have influenced the neighborhood effect estimates, such as the number of times each student moved to a different neighborhood during the study period. It is possible that the effects of the neighborhood variables on the aggression trajectories were influenced by other, unmeasured, family-level factors related to the selection of neighborhoods in which to live, however.

Despite the methodological strengths of our study, the generalizability of the results may be limited to similar rural contexts, particularly areas with large African–American populations or with lower median incomes than the national level, such as the rural southern states. Levels of aggression, however, were similar to those documented in other studies with adolescents of similar ages (Yoon et al. 2004), and the trajectory patterns resembled those from other studies with rural samples (Farrell et al. 2005). An additional limitation of this study is the inability to account for effects of bordering areas on the behavior of the adolescent residents within a specific neighborhood (Mowbray et al. 2007). Furthermore, adolescents are more mobile than younger children, and the concept of a “neighborhood” as limited by block group boundaries may be less relevant for older youth (Nicotera 2007).

In sum, our study suggests that girls growing up in disadvantaged rural neighborhoods engage in aggressive behaviors earlier and more consistently throughout adolescence than their peers who grow up in more socioeconomically advantaged neighborhoods. For boys, the socioeconomic context of these nonmetropolitan neighborhoods had a limited impact on aggression once social organization was taken into account. For both boys and girls, neighborhood social organization did not play a significant role in promoting aggressive behaviors. Future research should investigate the other unique aspects of rural neighborhoods and communities that impact healthy adolescent development.

References

Aber, J. L., Brown, J. L., & Jones, S. M. (2003). Developmental trajectories toward violence in middle childhood: Course, demographic differences, and response to school-based intervention. Developmental Psychology, 39(2), 324–348.

Allison, P. D. (2000). Multiple imputation for missing data: A cautionary tale. Sociological Methods and Research, 28, 301–309.

Allison, P. D. (2005). Imputation of categorical variables with PROC MI. Paper presented at the 30th Annual SAS Users Group International Conference (SUGI 30), Philadelphia, PA.

Aneshensel, C. S., & Sucoff, C. A. (1996). The neighborhood context of adolescent mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 37(4), 293–310.

Barnett, C., & Mencken, F. C. (2002). Social disorganization theory and the contextual nature of crime in nonmetropolitan counties. Rural Sociology, 67(3), 372–393.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Bellair, P. E., Roscigno, V. J., & McNulty, T. L. (2003). Linking local labor market opportunity to violent adolescent delinquency. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 40(1), 6–33.

Belsley, D. A., Kuh, E., & Welsch, R. E. (1980). Regression diagnostics. New York: Wiley.

Beyers, J. M., Bates, J. E., Pettit, G. S., & Dodge, K. A. (2003). Neighborhood structure, parenting processes, and the development of youths’ externalizing behaviors: A multilevel analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31(1/2), 35–53.

Blitstein, J. L., Murray, D. M., Lytle, L. A., Birnbaum, A. S., & Perry, C. L. (2005). Predictors of violent behavior in an early adolescent cohort: Similarities and differences across genders. Health Education and Behavior, 32(2), 175–194.

Brody, G. H., Ge, X., Conger, R. D., Gibbons, F. X., Murry, V. M., Gerrard, M., et al. (2001). The influence of neighborhood disadvantage, collective socialization and parenting on African American children’s affiliation with deviant peers. Child Development, 72(4), 1231–1246.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22(6), 723–742.

Bursik, R. J., Jr. (1988). Social disorganization and theories of crime and delinquency: Problems and prospects. Criminology, 26(4), 519–551.

Byrnes, H. F., Chen, M.-J., & Miller, B. A. (2007). The relative importance of mothers’ and youths’ neighborhood perceptions for youth alcohol use and delinquency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 649–659.

Caughy, M. O., O’Campo, P. J., & Muntaner, C. (2003). When being alone might be better: Neighborhood poverty, social capital and child mental health. Social Science and Medicine, 57, 227–237.

Chuang, Y., Ennett, S. T., Bauman, K. E., & Foshee, V. A. (2005). Neighborhood influences on adolescent cigarette and alcohol use: Mediating effects through parent and peer behaviors. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46, 187–204.

Chung, I., Hill, K. G., Hawkins, J. D., Gilchrist, L. D., & Nagin, D. S. (2002). Childhood predictors of offense trajectories. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 39(1), 60–90.

Connor, D. F. (2002). Aggression and antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: Research and treatment. New York: The Guilford Press.

Cook, T. D., Shagle, S. C., & Degirmencioglu, S. M. (1997). Capturing social process for testing mediational models of neighborhood effects. In J. Brooks-Gunn, G. J. Duncan, & J. L. Aber (Eds.), Neighborhood poverty: Policy implications in studying neighborhoods (Vol. 2, pp. 94–119). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Crowder, K., & South, S. J. (2003). Neighborhood distress and school dropout: The variable significance of community context. Social Science Research, 32, 659–698.

Deane, G., & Shin, H. (2002). Comparability of the 2000 and 1990 census occupation codes (technical report). Albany, NY: Lewis Mumford Center for Comparative Urban and Regional Research, SUNY at Albany.

Duncan, G. J., & Aber, J. L. (1997). Neighborhood models and measures. In J. Brooks-Gunn, G. J. Duncan, & J. L. Aber (Eds.), Neighborhood poverty: Context and consequences for children (Vol. 1, pp. 62–78). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Duncan, G. J., Connell, J. P., & Klebanov, P. K. (1997). Conceptual and methodological issues in estimating causal effects of neighborhoods and family conditions on individual development. In J. Brooks-Gunn, G. J. Duncan, & J. L. Aber (Eds.), Neighborhood poverty: Context and consequences for children (Vol. 1, pp. 219–250). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Elliott, D. S., Wilson, W. J., Huizinga, D., Sampson, R. J., Elliott, A., & Rankin, B. (1996). The effects of neighborhood disadvantage on adolescent development. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 33(4), 389–426.

Ennett, S. T., Bauman, K. E., Hussong, A. M., Faris, R., Foshee, V. A., DuRant, R. H., et al. (2006). The peer context of adolescent substance use: Findings from social network analysis. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16(2), 159–186.

ESRI. (2005). ArcMap 9.0 [CD-ROM]. Redlands, CA: Environmental Systems Research Institute.

Farrell, A. D., Kung, E. M., White, K. S., & Valois, R. F. (2000). The structure of self-reported aggression, drug use, and delinquent behaviors during early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29, 282–292.

Farrell, A. D., & Sullivan, T. N. (2004). Impact of witnessing violence on growth curves for problem behaviors among early adolescents in urban and rural settings. Journal of Community Psychology, 32(5), 505–525.

Farrell, A. D., Sullivan, T. N., Esposito, L. E., Meyer, A. L., & Valois, R. F. (2005). A latent growth curve analysis of the structure of aggression, drug use, and delinquent behaviors and their interrelations over time in urban and rural adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 15(2), 179–204.

Farrington, D. P. (1998). Predictors, causes, and correlates of male youth violence. In M. Tonry & M. H. Moore (Eds.), Youth violence (pp. 421–476). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Fergusson, D. M., & Horwood, L. J. (2002). Male and female offending trajectories. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 159–177.

Frazier, P. A., Tix, A. P., & Barron, K. E. (2004). Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(1), 115–134.

Ginther, D., Havman, R., & Wolfe, B. (2000). Neighborhood attributes as determinants of children’s outcomes: How robust are the relationships? The Journal of Human Resources, 35(4), 603–642.

Horton, N. J., & Lipsitz, S. R. (2001). Multiple imputation in practice: Comparison of software packages for regression models with missing variables. The American Statistician, 55(3), 244–254.

Howell, J. C., & Hawkins, J. D. (1998). Prevention of youth violence. In M. Tonry & M. Moore (Eds.), Youth violence (pp. 263–316). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ingoldsby, E. M., & Shaw, D. S. (2002). Neighborhood contextual factors and early-starting antisocial pathways. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 5(1), 21–55.

Jencks, C., & Mayer, S. E. (1990). The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighborhood. In L. E. Lynn Jr. & M. C. H. McGeary (Eds.), Inner city poverty in the US (pp. 111–185). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Kenward, M. G., & Roger, J. H. (1997). Small sample inferences for fixed effects from restricted maximum likelihood. Biometrics, 53(3), 983–997.

Kramer, R. (2000). Poverty, inequality, and youth violence. Annals, AAPSS, 567, 123–139.

Krieger, N., Chen, J. T., Waterman, P. D., Soobader, M., Subramanian, S. V., & Carson, R. (2002). Geocoding and monitoring of US socioeconomic inequalities in mortality and cancer incidence: Does the choice of area-based measure and geographic level matter? American Journal of Epidemiology, 156(5), 471–482.

Krieger, N., Waterman, P., Lemieux, K., Zierler, S., & Hogan, J. W. (2001). On the wrong side of the tracts? Evaluating the accuracy of geocoding in public health research. American Journal of Public Health, 91(7), 1114–1116.

Lee, M. R., Maume, M. O., & Ousey, G. C. (2003). Social isolation and lethal violence across the metro/nonmetro divide: The effects of socioeconomic disadvantage and poverty concentration on homicide. Rural Sociology, 68(1), 107–131.

Leventhal, T., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2000). The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 309–337.

Leventhal, T., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2003). Moving to opportunity: An experimental study of neighborhood effects on mental health. American Journal of Public Health, 93(9), 1576–1582.

Loeber, R., & Hay, D. (1997). Key issues in the development of aggression and violence from childhood to early adulthood. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 371–410.

Lynch, J. W., & Kaplan, G. A. (2000). Socioeconomic position. In L. F. Berkman & I. Kawachi (Eds.), Social epidemiology (pp. 13–35). New York: Oxford University Press.

MapQuest. (2005). Retrieved July 12 2005, from http://www.mapquest.com/.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100(4), 674–701.

Molnar, B. E., Browne, A., Cerdá, M., & Buka, S. L. (2005). Violent behavior by girls reporting violent victimization. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 159, 731–739.

Mowbray, C. T., Woolley, M. E., Grogan-Kaylor, A., Gant, L. M., Gilster, M. E., & Williams Shanks, T. R. (2007). Neighborhood research from a spatially oriented strengths perspective. Journal of Community Psychology, 35(5), 667–680.

Nagin, D. S. (1999). Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychological Methods, 4(2), 139–157.

Nagin, D. S., & Tremblay, R. E. (2001). Analyzing developmental trajectories of distinct but related behaviors: A group-based method. Psychological Methods, 6(1), 18–34.

Neter, J., Wasserman, W., & Kutner, M. H. (1990). Applied linear statistical models: Regression, analysis of variance, and experimental designs (3rd ed.). Burr Ridge, IL: Irwin.

Nicotera, N. (2007). Measuring neighborhood: A conundrum for human services researchers and practitioners. American Journal of Community Psychology, 40, 26–51.

Oakes, J. M. (2004). The (mis)estimation of neighborhood effects: Causal inference for a practicable social epidemiology. Social Science and Medicine, 58, 1929–1952.

Oberwittler, D. (2007). The effects of neighbourhood poverty on adolescent problem behaviours: A multi-level analysis differentiated by gender and ethnicity. Housing Studies, 22(5), 781–803.

Osgood, D. W., & Chambers, J. (2000). Social disorganization outside the metropolis: An analysis of rural youth violence. Criminology, 38, 81–115.

Parker, E. A., Lichtenstein, R. L., Schulz, A. J., Israel, B. A., Schork, M. A., Steinman, K. J., et al. (2001). Disentangling measures of individual perceptions of community social dynamics: Results of a community survey. Health Education & Behavior, 28(4), 462–486.

Pattillo, M. E. (1998). Sweet mothers and gangbangers: Managing crime in a black middle-class neighborhood. Social Forces, 76(3), 747–774.

Pratt, T. C., & Cullen, F. T. (2005). Assessing macro-level predictors and theories of crime: A meta-analysis. Crime and Justice, 32, 373–450.

Ramirez-Valles, J., Zimmerman, M. A., & Juarez, L. (2002). Gender differences of neighborhood and social control processes: A study of the timing of first intercourse among low-achieving, urban, African American youth. Youth & Society, 33(3), 418–441.

Raudenbush, S. W. (2003). The quantitative assessment of neighborhood social environments. In I. Kawachi & L. F. Berkman (Eds.), Neighborhoods and health (pp. 112–131). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Sampson, R. J. (1999). Ecometrics: Toward a science of assessing ecological settings, with application to the systematic social observation of neighborhoods. Sociological Methodology, 29, 1–41.

Ricketts, T. C., III, Johnson-Webb, K. D., & Randolph, R. K. (1999). Populations and places in rural America. In T. C. Ricketts, III (Ed.), Rural health in the United States (pp. 7–24). New York: Oxford University Press.

Ross, C. E., & Jang, S. J. (2000). Neighborhood disorder, fear, and mistrust: The buffering role of social ties with neighbors. American Journal of Community Psychology, 28(4), 401–420.

Rubin, D. B. (1987). Multiple imputation for non-response in surveys. New York: Wiley.

Rubin, D. B., & Schafer, J. L. (1997). The MIANALYZE procedure. Retrieved November 12 2004, from http://support.sas.com/rnd/app/papers/mianalyzev802.pdf.

Sampson, R. J., Morenoff, J. D., & Gannon-Rowley, T. (2002). Assessing “neighborhood effects”: Social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology, 28, 443–478.

Sampson, R. J., Morenoff, J. D., & Raudenbush, S. W. (2005). Social anatomy of racial and ethnic disparities in violence. American Journal of Public Health, 95(2), 224–232.

Sampson, R. J., & Raudenbush, S. W. (2004). Seeing disorder: Neighborhood stigma and the social construction of “broken windows”. Social Psychology Quarterly, 67(4), 319–342.

Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277(5328), 918–924.

SAS Institute. (2003). Statistical Analysis Software (SAS), Version 9.1. Cary, NC: SAS.

Sen, P. K., & Singer, J. D. (1993). Large sample methods in statistics: An introduction with applications. New York: Chapman & Hall.

Shulruf, B., Morton, S., Goodyear-Smith, F., O’Loughlin, C., & Dixon, R. (2007). Designing multidisciplinary longitudinal studies of human development: Analyzing past research to inform methodology. Evaluation and the Health Professions, 30(3), 207–228.

Simons, L. G., Simons, R. L., Conger, R. D., & Brody, G. H. (2004). Collective socialization and child conduct problems: A multilevel analysis with an African American sample. Youth & Society, 35(3), 267–292.

Singer, J. D. (1998). Using SAS PROC MIXED to fit multilevel models, hierarchical models, and individual growth models. Journal of Education and Behavioral Statistics, 24(4), 323–355.

Stewart, E. A., Simons, R. L., & Conger, R. D. (2002). Assessing neighborhood and social psychological influences on childhood violence in an African–American sample. Criminology, 40(4), 801–830.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2002). Census 2000 Summary File 3-United States [Electronic data files].

U.S. Census Bureau. (2005). American factfinder advanced geography search. Retrieved October 20 2005, from http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/AGSGeoAddressServlet?lang=en&_programYear=50&_treeId=420.

U.S. Postal Service. (2005). ZIP code lookup. Retrieved July 12 2005, from http://zip4.usps.com/zip4/welcome.jsp.

Upchurch, D. M., Aneshensel, C. S., Sucoff, C. A., & Levy-Storms, L. (1999). Neighborhood and family contexts of adolescent sexual activity. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(Nov), 920–933.

Wagle, U. (2002). Rethinking poverty: Definition and measurement. International Social Science Journal, 54(171), 155–165.

Warner, B. D., & Rountree, P. W. (1997). Local social ties in a community and crime model: Questioning the systemic nature of informal social control. Social Problems, 44(4), 520–537.

Wilcox, P. (2003). An ecological approach to understanding youth smoking trajectories: Problems and prospects. Addiction, 98(Suppl 1), 57–77.

Wilson, W. J. (1987). The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Yoon, J. S., Barton, E., & Taiariol, J. (2004). Relational aggression in middle school: Educational implications of developmental research. Journal of Early Adolescence, 24(3), 303–318.

Yuan, Y. C. (2000). Multiple imputation for missing data: Concepts and new development. Paper presented at the 25th Annual SAS Users Group International Conference (SUGI 25), Indianapolis, IN.

Acknowledgments

The Context of Adolescent Substance Use study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA16669) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (R49 CCV423114). We would like to thank Thad Benefield, John Hipp, and Bob Faris for their programming assistance, and Karl Bauman and Daniel Bauer for reviewing early drafts of this manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Karriker-Jaffe, K.J., Foshee, V.A., Ennett, S.T. et al. Sex Differences in the Effects of Neighborhood Socioeconomic Disadvantage and Social Organization on Rural Adolescents’ Aggression Trajectories. Am J Community Psychol 43, 189–203 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-009-9236-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-009-9236-x