Abstract

In this paper we investigate the connection between forms of sustainability and masculinity through a study of everyday life in a Danish alternative slaughterhouse. In contrast to the predominant form of slaughterhouses today in Western contexts, the ‘alternative’ slaughterhouse is characterized as non-industrial in scale and articulating some form of a sustainability orientation. Acknowledging the variability of the term, we firstly explore how ‘sustainability’ is understood and practiced in this place. We then illuminate the situated manifestations of masculinities, which appear predominantly- though not exclusively- hegemonic in nature. We next reflect on how the situated and particular sustainability of this site come to bear on a workplace long characterized as a masculinized site of, e.g., violence and repression, showing how the sustainability of the alternative slaughterhouse has potential to nourish alternative masculinities. We finally call for more attention at this nexus of sustainability and masculinities studies, to examine how the broad sustainability turn in food systems needs to be further examined in relation to what masculinities it perpetuates, as well as how a focus on masculinities may enhance our understanding of varying forms of sustainability, especially their potential for ecologically and socially just food systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As Lise entered the lunchroom of the slaughterhouse looking for a place to sit, one of the workers loudly uttered “Why don’t you come sit on my lap?”. The room erupted in laughter as she found and took a seat. This situation, on the first day of ethnographic data collection, became a marker for what we would discover in a workplace shaped in large part by a masculine register. The masculine nature of industrial animal production and processing has been illuminated in scholarship, if to a limited extent. Building upon work by Ackroyd and Crowdy (1990) about how English ‘slaughtermen’ cultivated a distinctive occupational culture based on ‘aggressive realism’, where bloodied clothing was worn as a source of masculine pride, McLoughlin (2018) explored how an unemotional exterior on the part of male workers belied a deeply conflicted interior. Her research in an Irish industrial slaughterhouse described the fraught attempts to repress and erase the emotional experiences of both workers and cattle, as an outcome and entrenchment of hegemonic masculine ideals that underpin such work. Blanchette’s (2019) detailed ethnography of industrial pork production in the USA disclosed the marking of emotional attachment to pigs as “implicitly feminine”, while detachment was cast as “implicitly masculine”. Also in the USA, Gavit (2016) detailed multi-faceted traumatic stress experienced by male slaughterhouse workers and charted a possible path toward healing, necessarily accompanied by a fundamental rethinking of the industry at large. Yet despite such research, and despite the scholarship exploring gender and meat preparation/consumption (e.g. Lapina and Leer 2016; Leer 2016; 2019; Neuman et al. 2015), masculinities remains a broadly ‘overlooked theme’ in sustainability, environmental, and specifically food systems research (Sachs 2023; also see MacGregor 2017).

Much of the academic inquiry into ‘the slaughterhouse’ as an empirical site has taken place at the industrial scale. Yet smaller scale slaughtering was the norm up to the late 19th century, at which point we can observe an industrial turn as exemplified by the notorious Union Stockyard in Chicago, USA (Fitzgerald 2010).Footnote 1 Still, some smaller scale slaughtering has persisted and a new if modest wave is rising, notably in regions with highly industrialized animal production and processing systems, namely Europe and the USA. This may be understood as a reaction to several interconnected longer-term trends including rural disinvestment alongside decreasing rural populations, and increasing unemployment for those left behind. Here, rural residents seek alternative forms of employment, activities that may converge well with growing contemporary public interest in local, sustainable food systems (Hoffman 2012; Franks and Peden 2021). Demands by climate-change conscious actors to reduce meat consumption may also iterate in perhaps surprising ways with food producers including slaughterers. Thus some of today’s ‘alternative’ slaughterhouses can embody new characteristics, the implications of which remain understudied due not least to the general inaccessibility of these sites but also their emergent nature.

With this contribution, we examine the connections between forms of sustainability and masculinities in the contemporary ‘alternative slaughterhouse’. By ‘alternative’, we refer to slaughterhouses that are both non-industrial,Footnote 2 and that embrace some measure of a sustainability orientation. What exactly constitutes sustainability is ever an empirical question, and one we explore. We note that some industrial slaughterhouses are also enacting ‘sustainability’, not least in the global sustainability leader Denmark (Yale University 2022). In these slaughterhouses, sustainability as energy and resource efficiency reigns supreme (see e.g. Danish Crown 2022). Yet other ways of making sustainable, e.g. practices of care toward human social sustainability (e.g. worker wellbeing) and even non-human and interspecies wellbeing, are arguably less in reach at larger scales. But overall, we are less concerned with how sustainable the slaughterhouse is in the sense of measuring and authorizing, and rather within the context of a self-identified sustainability, we seek to illuminate how the term is understood and embodied in the everyday. Moreover, we are concerned by the typically problematic masculinized nature of the slaughterhouse, which leads us to wonder: how might the characteristics of the ‘alternative’ slaughterhouse serve to mediate the tendency of slaughterhouses toward hegemonic masculinities?

Through ethnographic encounters in an alternative slaughterhouse in the country of Denmark and theorizing on the gender and masculinities/environment nexus, this research will illuminate how a ‘sustainability’ orientation including smaller scale come to bear on this workplace. We will consider: what do both sustainability and masculinity look like in this place? How do they interact? Lastly, we reflect on the possible trajectories of masculinities in the broader sustainability transition of food systems. We believe the answers matter for at least two overlapping reasons: i) it matters what particular ideas and practices of sustainability do in the world, in the sense of having impacts even beyond some ecological improvement. For example, how do varying understandings and practices of this broad term come to bear on human social contexts such as the workplace – in this case in terms of (re)shaping gendered behaviors and expressions? And ii), if we anticipate a persistence of meat consumption in the future, how could conditions of the slaughterhouse be improved for both non-human animals as for human workers, as for the socio-ecologies in which they exist? In other words, what lessons can we glean at this nexus of sustainability and masculinity, and what practices must we nourish?

In the following, we share our conceptual tools, describing the slaughterhouse as a site of empirical research, and our understandings of and approaches to masculinities as well as sustainability. After a description of our methods and methodology, we unpack our findings in relation to the research questions, and finally discuss and present concluding remarks.

Slaughterhouse as a site

The work of slaughtering animals for food production has been transformed several times during the past few hundred years. In Denmark as many other countries, slaughtering had long occurred in diverse places, from backyards to city/village centers alongside the furriers and shoemakers who subsequently made use of the skins (Copenhagen Association of Slaughterers 2009). In especially Western countries, Fitzgerald (2010) describes the evolution of the slaughterhouse via three major periods, the first of which was the public slaughterhouse reforms of the 18th century. This marked the start of a consolidation trend and relocation beyond town walls while subjecting slaughtering to greater State oversight to improve hygiene as well as regulate what was increasingly deemed as morally dangerous work (MacLachlan 2008; Fitzgerald 2010). The next period, industrialization of the late 19th century, was characterized by private ownership and further consolidation alongside greater scales of production (as volume and speed), mechanization, and the increasing power of capitalists relative to the working class; according to Fitzgerald (2010), the latter became especially pronounced in the post-WWII period and continues today. Finally, the late 20th century saw industrialized, increasingly consolidated facilities (i.e. fewer and larger slaughterhouses) being relocated to small rural communities where labor unions and protections from the many externalities of industrial meat production are often weaker.Footnote 3 Fitzgerald argues that each period marked a movement further away from the public gaze, an intentional invisibilizing that leads critical scholars like Pachirat (2011, p. 4) to liken the site to “more self-evidently political analogues—the prison, the hospital, the nursing home, the psychiatric ward, the refugee camp, the detention center, the interrogation room, the execution chamber, the extermination camp—the modern industrialized slaughterhouse is a ‘zone of confinement’, a ‘segregated and isolated territory’, in the words of sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, ‘invisible’ and ‘on the whole inaccessible to ordinary members of society’.”

The first larger public slaughterhouses opened in Denmark, a country with a long tradition for food production, in the 1880s. The country has since followed the same arc of consolidation, industrialization, and spatial relocation. Like its broader livestock production systems, Danish slaughterhouses today are globally renowned for their efficiency, as well as “extraordinarily high level of consumer protection, food safety and animal welfare” (Danish Food Agency 2015). Denmark hosts the world’s largest pork exporter, Danish Crown, whose newest abattoir was hailed in 2016 as “the most modern abattoir in the world” (Danish Crown 2016). This site’s “amazing productivity” is celebrated on their website by noting that the old slaughterhouse spent 118 years to slaughter 47 million pigs, whilst the new abattoir has “reached the same milestone (…) in just 11 years” (Danish Crown 2016).

Despite the efficiency achievements of industrial scale slaughtering, some non-industrial slaughterhouses have persisted and some are rising anew. This is especially due to the niche market for ‘return slaughterings’, which entails a farm-to-slaughter back to farm relation (as compared to farm to slaughterhouse to supermarket as typifies the industrial process), and/or locally produced specialty meat products provided directly to local residents. Today, authorities calculate 86 sites of slaughtering in the country, of which 21 are ‘large’ and 65 are ‘small’.Footnote 4 It is worth noting that the official designation of ‘small’ entails a maximum processing capacity of 35,000 ‘animal units’ per year.Footnote 5 ‘Small’ slaughterhouses in Denmark today constitute just 20 percent of total slaughtering annually (Danish Veterinary and Food Administration 2023).Footnote 6 Such trends are not unique to Denmark. In the UK for instance, 99 percent of all pigs slaughtered in the country is conducted by just ten abattoirs (Franks and Peden 2021). Small slaughterhouses differ from industrialized slaughterhouses in several key ways. Workers are more likely to be ‘skilled’,Footnote 7 the customers more likely to be local, and the animals slaughtered are raised in non-industrial production systems. Moreover, because of the direct communication and interaction with the local community, small-scale slaughterhouses may serve intentionally or not to reverse the invisibilizing of this site over past decades.

While it remains hard to see the slaughterhouse today, they are nonetheless (or following such intentional invisibilizing?) a rich site for academic inquiry. In addition to the limited scholarship applying a gender lens at the start, much of the small but growing body of such ‘slaughterhouse scholarship’ has put workers in focus, within the larger body of scholarship casting a critical gaze at industrialized animal production systems (Pachirat 2011; Weis 2013; Silbergeld 2016). Rarely a publicly celebrated form of employment (Ackroyd and Crowdy 1990; Press 2021), attention tends toward the human physical and psychological effects of this work over time (e.g. Slade and Alleyne 2021), although the ways such impacts are bound up in the particular intra-species encounters of the slaughterhouse have also captured scholarly attention (Baker 2013; Winders and Abrell 2021). For instance, de la Cadena and Martínez-Medina (2021) lament the industrial slaughterhouse as a site of alienation, a place where death is simply ‘eventless’ and the pace of killing for market efficiency demands “detached impersonal relations” amongst species. Animal geographies and related scholarship have also attended carefully to the experiences of the porcine, bovine, and avian beings under such systems (e.g. Holloway and Bear 2017; Blanchette 2019; Stoddard and Hovorka 2019; McLoughlin et al. 2024).

In a review of the social history of ‘the slaughterhouse’, Fitzgerald (2010, p. 58) points out that, “Conceptually, an examination of the slaughterhouse as an institution has a lot to offer: it is a location from which one can view economic and geographic changes in the production of food, cultural attitudes toward killing, social changes in small communities, and the changing sensibilities and relations between humans and non-human animals.” Blanchette (2019) further illustrates the uniqueness of broader animal agribusiness as a site, through its characterization as “scandalous (…), a special domain, an exceptional deviation” in imagined norms of, in his case, American capitalism and society. This research is inspired by such conceptualizations of the slaughterhouse as a site within broader primarily capitalist animal agribusiness. With the access we were quite exceptionally granted, we keep this in mind whilst focusing in on the nature and nexus of forms of sustainability and masculinity.

Gender, masculinities, and sustainability

Ecofeminist-inspired scholars have long pointed out that hegemonic masculinities are at the center of today’s complex socio-ecological challenges (Pulé et al. 2021; also see Connell 2017; Di Chiro 2017; MacGregor and Seymore 2017). Following Raewyn Connell, we understand hegemonic masculinities as “the patterns of values and practices” that legitimize certain men’s prevailing societal position “while subordinating other forms of masculinities and all femininities” (nicely paraphrased in MacGregor and Seymore 2017, p. 11). Whilst masculinities are rightly understood in the plural to accommodate the diversity of socio-cultural manifestations (Connell 2017), the designation of ‘hegemonic’ invokes some common characteristics, not least the presence of hierarchy and domination,Footnote 8 that become recognizable by their association with norms and privilege (Hultman 2017). The effects of such dominance and privileges clearly extend beyond the human social realm. They have negatively impacted the rest of nature to such an extent that some suggest the current state of affairs would be more accurately labeled the (M)anthropocene (Raworth 2014), or even White (M)Anthropocene (Di Chiro 2017).

As ‘patterns of practices’, hegemonic masculinities in a given context will not necessarily appear simply, as “domination based on force” (Connell and Messerschmidt 2005, p. 846). As animal geographer and anthropologist Eimear McLoughlin (2018) detailed in an Irish slaughterhouse, hegemonic masculinity also manifests in, for example, the denial, diminishing, or repression of emotions, of “both workers as well as the emotional experience of cattle” (also see Keough 2010). McLoughlin attends to what she calls the ‘institutionalized masculinity’ of the slaughterhouse, and the ‘masculine ideal’ of the worker, characterized by suppression of feeling alongside a ‘physical prowess’. By paying attention to emotions (she conducts an ‘emotionography’), McLoughlin notices occasional ‘ruptures of emotion’ that effectively destabilize the masculine ideal. This unveiling invokes Connell and Messerschmidt’s (2005) advancement in understanding hegemonic masculinities as always ‘in the making’, rather than fixed and assured. With this they point out that transformation is an ever-present potentiality.

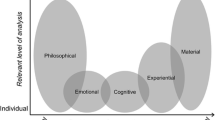

The critical first step however has been to mark masculinities (MacGregor 2017), reminding us that until recently, men and masculinities have largely remained out of sight within environmental and even gender fields (MacGregor 2017) Still, insights from especially the 1990s at the nexus of ecofeminist (e.g. Gaard 1997) and masculinity studies (e.g. Connell 1990) formed a foundation upon which new frameworks are now emerging. One typology in particular advances understanding of various manifestations of masculinity in relation to and within environmental politics, illuminating particular relations amongst masculinity types and other humans and the rest of nature (Hultman 2017; Hultman and Pulé 2018). To distinguish and conceptualise varying masculinities within environmental politics, Hultman (2017) and Hultman and Pulé (2018) developed a tripart typology that firstly theorizes ‘industrial/ breadwinner’ masculinities. ‘Industrial / breadwinner’ refers to those who control and/or manage the means of production and support services, often “Wealthy, white, Global Northern cis-males, who are the prime beneficiaries of traditional masculinist constructs [yet] also the most pressured to live within strict masculinist constructs. They are isolated and sensually cauterised at terrible cost to their emotional literacy and relational proximity to Earth, others, and self, even as they are socio-economically and politically advantaged” (Pulé et al. (2021, p. 23). The privileges of hegemonic masculinity thus tend to mask the terrible price that bearers also pay.

‘Ecomodern masculinities’, the second figuration, entails a greenwashed masculinity that valorizes sustainability, yet through a neoliberal lens. “While distinct from industrial/breadwinner masculinities in a willingness to seek compromise, ecomodern masculinities have emerged paradoxically: aligning with courage, global responsibility and determination, increased care for the glocal commons but also remaining adherent to market forces” (Hultman and Pulé 2019, p. 48). Within this masculinity, care and compassion also remain subordinate to techno-rationality, toughness, and economic growth (Hultman 2013). The authors make evident that the sustainability attempts enacted through this masculinity type remain woefully inadequate. And both types retain hegemonic elements, from overt exploitation to sheer hubris, and both continue to position humans outside of, and above, the rest of nature.

Contrasting the extractivist orientation of industrial/breadwinner masculinities and the insufficiencies of ecomodern masculinities, it is through their third type of ‘ecological masculinities’ that an “exit politics” emerges, marking a move from “masculine hegemonisation to ecologisation” (Hultman and Pulé 2018, p. 231). An aspirational figuration, ‘ecological masculinities’ aims “to (re)awaken ways of being, thinking, and doing masculinities that are intimately engaged with Earth, place and people at the same time; to deepen relational connections (both amongst humans and between our species and the other-than-human world), and to support us all to experience the feelings of loss associated with the anthropogenic changes that are upon us, so that we can together respond to the monumental social and environmental challenges at hand with increasing and widening circles of care” (Pulé and Sykes 2022).Footnote 9 ‘Ecological masculinities’ is thus conceptualized as a relational category based on care for the glocal commons. Such relationality implies not only openness, but moreover a vulnerability, a precariousness, that is essential to the development of environmental ethic (Requena-Pelegri 2021).

This ‘arche-typology’ developed over several years by Hultman and Hultman and Pulé has helped advance more specific notions of masculinity in specific contexts. Daggett (2018) for instance explores the drivers and consequences of performances of hegemonic ‘industrial’ masculinities by middle- and working-class Trump supporters, articulating the rise of a ‘petromasculinity’ that emerges at the nexus of rising gender and climate troubles. Constituted by ‘climate refusal’ and aggressive fossil fuel consumption alongside overt authoritarian and misogynistic sentiments, this ‘hyper-masculinity’ protects fossil capitalism at any cost. Darwish (2021) meanwhile explores the intersections of Nordic White extremism and a deep yet myopic environmentalism, articulating a cautionary tale for ecological masculinities and calling for rigid boundaries against any caring for nature that simultaneously drives racist and misogynistic rhetoric and practices. We draw from the growing constellation of masculinities, and in particular the archetypes put forth by Hultman and Pulé (2018), as we analyze the situated masculinities in the ‘alternative’ slaughterhouse. Building upon gender scholars like Connell who have established that institutions are gendered, which connects well with an understanding of the slaughterhouse as an institution (e.g. Fitzgerald 2010), we try to grasp whether and how the typical hegemonic characteristics of the slaughterhouse, are mediated by the site’s sustainability orientation.

Finally, a word on our approach to sustainability. Following the critical sustainability studies literature (e.g. Rose and Cachelin 2018), we recognize the term’s deeply ambiguous nature and thus susceptibility toward co-option and misuse. As Leary (2019) described, sustainability too conveniently combines “literal vagueness with moral certainty”. Inspired by these perspectives, we recognize the need to ground sustainability by exploring how exactly it is understood and pursued in this place. It is for this reason that we may use the term in the plural or refer to forms of sustainability. We acknowledge the ‘three pillars of sustainability’, entailing some kind of (human) social sustainability, economic sustainability, and environmental sustainability (Purvis et al. 2019). Whilst these can be helpful to articulate and relate situated understandings and practices of this buzzword, we also pause to note that they have long neglected interspecies relations. Perhaps these relations could be accommodated within an environmental/ ecological sustainability, but this is arguably the broadest pillar of them all, subject to all kinds of stretching (among other ‘plastic words’, see Jørgensen 2015) and strategic interpretations that omit the critical importance of interspecies relationships. We are provoked to propose an added pillar of ‘interspecies sustainability’ as a critical component akin or even superseding the current anthropocentric notion of social sustainability, and more specific than environmental sustainability. Yet overall and as noted above, we are less concerned with how sustainable the slaughterhouse is in the sense of measuring and authorizing. Rather, we seek to unfold how their ideas and practices infuse, and perhaps diffuse beyond, a site typically characterized by hegemonic expressions of masculinity.

Methodology, methods, and site

Slaughterhouses are notoriously impenetrable. To obtain access to a site, requests were emailed to seven of the aforementioned 65 small slaughterhouses in Denmark, selected according to distance from Copenhagen. The slaughterhouse featured here was the only to reply positively. The remaining replied negatively (1) or not at all (5), a disinterest likely related to fear of critique and negative publicity. The slaughterhouse we investigated is very small, with a processing average of just around 1,150 animal ‘units’ (see footnote above) per year. Importantly, whilst our characterization of ‘alternative’ above encompassed both ‘non industrial’ and a ‘sustainability’ orientation, we note here and in the next results section that the slaughterhouse featured in our research does not publicly label itself as ‘sustainable’. However, in the very initial stages of encounter and as details for Lise’s visits were being organized, the importance of sustainability to the owner in terms of how her slaughterhouse functioned came forth in such a way as to make this site compelling for our research interests.

This study used ethnographic methods to investigate perceptions and practices of sustainability and gendered behaviours. Methods for data collection consisted of semi-structured though relatively informal interviewing plus participant observation, firstly within an alternative slaughterhouse in Denmark and later during a public talk and panel debate, and supplemented by several email and phone conversations with the slaughterhouse owner. Lise conducted the participant observation including ‘walk-alongs’ in the slaughterhouse over five working days in early 2023. This slaughterhouse employed nine employees and operated at a slaughtering capacity of 15–20 animals per week. These employees are full or part time employed and are residents of the area, as opposed to seasonal/contractual employment of sometimes non-residents as typifies much slaughterhouse labor. Lise talked with the slaughterhouse owner, staff (five male ‘skilled’ slaughterers, two female meat packers and one male cleaning assistant) and followed the various everyday activities. This included receiving the animals, the process of killing and carving, further food processing (namely sausage-making), packing, office work, customer visits and coffee and lunch breaks. The participation entailed dialogue with the staff while they worked as well as engagement in meat-packing and sausage preparation. Dialogue circled around a list of semi-structured questions developed by both authors. Main themes included their perceptions of and experiences with sustainability, their work histories, their perceptions of slaughtering, their relations with the animals and their experience of being a man/woman in the setting.

A parallel co-developed data collection instrument specified key themes for observation, in particular manifestations of gendered behaviors including hegemonic masculine norms. Daily field notes served as the empirical basis for analysis. Inspired by anthropological methods of deepening results through testing and discussing preliminary findings with the field as well as other audiences (see e.g. Kottak 2015), we arranged a public talk and panel debate that focused on the possibilities for sustainable meat production in Denmark. It featured a presentation of preliminary findings by Lise, followed by a panel discussion with another academic, a green think tank representative, and the slaughterhouse owner. Rebecca attended to take notes and pose questions of relevance to this article particularly to the slaughterhouse owner. The public talk and panel debate was also a way to present and discuss (preliminary) findings with a representative from the slaughterhouse, supporting that their voices would be heard. Analysis unfolded through several joint discussions on observational and discussion notes for collective interpretation, coding of field notes, and eventual writing. The analysis was characterized by an iterative process relating the empirical material to theoretical concepts and scientific literature on sustainability, masculinities, and slaughterhouses.

In carrying out the data collection and subsequent analysis, we were inspired by a feminist qualitative methodology in the sense of being animated by a concern for and attentiveness to accountability and positionality. As academic scholars/activists who are very concerned about the socio-ecological crises of our time, we entered a site about which we already had strong opinions, at least in terms of its role within broader contemporary food systems. A feminist methodology foremost challenges claims to universality and neutrality produced through what Haraway (1988, p. 581) calls the ‘god-trick’: “the gaze that mythically inscribes all the marked bodies, that makes the unmarked category claim the power to see and not be seen, to represent while escaping representation”. Feminist qualitative research thus pays attention to the various positions from which knowledge is constructed and their embeddedness in power relations. This invokes what Haraway (1988) calls ‘situated knowledge’, recognizing how research is influenced by one’s own ‘standpoint’ (Harding 1986) or ‘location’ (Haraway 1988) – for example, of how research process and outcomes are shaped by how the researcher is perceived by those they encounter, and by their particular disciplinary perspectives, beliefs, and worldviews.

Although warmly received, it was clear to Lise (conducting the majority of fieldwork) that she was looked upon by the slaughterhouse employees as a strange species from the academic world. It is a perpetual challenge to maintain openness whilst engaging as a critical scholar who bears normative positions. However, Scheper-Hughes (1995, p. 409) reminds us that holding a normative position is not in opposition to conducting good ethnography, but rather a necessity if ethnography “is to be worth anything at all”. By respecting rather than repressing these normative facets and actively mobilizing them as a way to deepen conversations, we strove for honesty and integrity in our research process. For example, whilst conducting the fieldwork Lise was honest about the fact that she rarely eats meat and is critical about the meat industry. Rather than being a conversation stopper, Lise experienced that it urged the employees to engage in deeper discussions where they defended as well as reflected on their views. Finally, we also acknowledge the limitations of our research given the limited data collection duration, in a single site. We stress that the importance of our study is to be found in its explorative character of a yet understudied field rather than its representativeness. In the discussion and conclusion, we suggest where more research is needed.

Findings

We begin by describing the situated understandings, practices, and also dilemmas of sustainability in this place. These emerged in particular through interrelated aspects of food culture and scale. This empirical foundation provides a basis to think with as we reflect upon various expressions of masculinities that forms the following section, and the mediating function that this particular ‘sustainability’ orientation may entail.

Sustainability in the ‘alternative’ slaughterhouse? A focus on food culture and scale

As described above, a major theme of discussion during Lise’s daily encounters at the slaughterhouse revolved around the workers’ general perceptions and practices of ‘sustainability’. There is always a risk that respondents tell a researcher that which they think is desired, particularly when the atmosphere is cordial as characterized these encounters, and/or when the power dynamics at play between e.g. ‘blue’ and ‘white’ collar workers compel alignment. Yet from the start, as evidenced in the joking and general ease Lise experienced, we perceive the dynamics were more of curiosity than compulsion. Further, while the workforce expressed varying relations with the topic of sustainability, everyone agreed that it matters and easily associated it with aspects of their work, lending authenticity to their statements.

Most workers articulated a grounded understanding of sustainability, i.e. closely related with food, at times as habits/ culture and in relation to systems of production. One key and popular diagnosis of a ‘major sustainability problem’ was modern society’s eating and cooking habits. Multiple workers referred to the trend of increasing ‘food waste’ alongside fewer recipes that accommodate more animal parts, a realm now left to the purview of mainly elderly customers. “Before”, the workers described, customers buying a whole or half an animal used more of the animal: soup was cooked on the bones, it was normal to eat intestines, and fat was prized for its flavor. As one of the slaughterer / meat carvers expressed: “I enjoy when old women come in here, they have plans for using all the meat and I get ideas for new dishes when I speak to them”. These workers estimated that around just half of the animals was consumed, the rest ending ‘in the bin’. Indeed, bins for animal remains dominated the small space and the slaughterers’ attention, as they moved frequently between cutting board and disposal.

Further, some lamented the fact that their craft is restricted by contemporary food culture, a system shaped by ‘fast-paced’ and ‘convenience-oriented’ lifestyles. “Today everyone just wants lots of minced meat, because they find it easy and fast to cook with, and most people don’t have time to cook,” said the slaughterhouse owner, adding, “I think it is a shame, there are so many good dishes that are never used, and my opinion is that they don’t take longer to cook.” It could be a disservice to the generational skills and knowledge related to preparing organs etc., to simply chalk them up as concern for 'sustainability', though it is fascinating to note that specific historical relations with food, waste, etc. can come to align with contemporary concerns (even as not all are easily reconcilable, see the point about wasted skins below). Such traditional customs with potential for revival, e.g. as reinterpreted within a sustainability agenda, may get a stronger foothold as compared to new initiatives- especially those perceived as being imposed from above. As a result of the frustrations of the prevailing wasteful food culture, the small slaughterhouse had launched the campaign: “Finish your food”. With an aim to expand customer diets and palates, the slaughterhouse initiated a new service of cutting out the meat with the customer. During this process they disclosed new possibilities for body part use including by offering their own recipes.

Another aspect of food culture that came to the fore of sustainability discussions was the new on-site practice of incorporating plant-based ingredients to processed meat products – in particular, sausage. The sausage-maker apprentice was experimenting with sausages containing up to 20 percent cooked vegetables, an unusual undertaking driven by this skilled young worker. The biggest challenge he faced was limited facilities to cook the vegetables. Expensive cooking equipment was also required to upscale this product line. A substantial contract was under negotiation during Lise’s visit entailing a standing meat order to a nearby boarding school with over 1000 students. The school was intrigued by the sausage experimentation and requested sausages with the highest plant-based input possible—‘without compromising taste’. The school leadership aspired to a climate-friendly profile and was undertaking several strategies to reduce students’ meat consumption. The slaughterhouse owner saw the collaboration as an opportunity to develop the slaughterhouse in a more sustainable direction, and a big order like this made it financially possible to invest in the necessary cooking equipment, as well as making it worth the effort to obtain organic certification, which the boarding school also requested.

Scale is also at the heart of potential for multiple forms of sustainability in slaughtering and meat processing, and here we turn to aspects of size, facilities, and general processing capacity. Small slaughterhouses typically slaughter just 15–20 animals a week (compare this to the hundreds or more per day at typical industrial sites). Yet slower processing allows a sense of craft to take shape and through this emerges particular sustainability manifestations. In fact, for all workers as well as the owner, the quality of the meat and the handicraft were of most concern, with these aspects dominating discussion in general and in relation to ‘sustainability’. The owner of the slaughterhouse described how it was a value for her, and for her customers, that the slaughterings were ‘well-made’ rather than rushed: “We go for quality. I don’t care how long time it takes for my workers to do a slaughtering, as long as they finish the task of the day and do it well. Most of my workers are old, so they can’t work fast anyway, and it is impossible to get hold of a young skilled slaughterer. (…) If the meat is a quality product, it is so full of taste that you need much less, and that is also sustainability”. Staff further articulated the particular temporality of a ‘good’ meat product, noting an important aspect of the small slaughterhouse is that they offer on-the-hook ageing. This means that the cow after the slaughtering process is hung in a cooler room for two weeks for the meat to dehydrate and age and thereby develop taste. Yet, this delimits how many animals can be slaughtered (due to space constraints). This articulation of environmental sustainability as a more ‘moderate’ meat production and consumption intertwines with a social sustainability in the sense of decent work, not least for substantially older workers, alongside a value-based connection with their customers.

At the small and perhaps ‘alternative’ slaughterhouse, meat is primarily returned / sold on to the often small-scale area farmers. As noted, industrial slaughterhouses in contrast prioritize servicing industrial farms and sell meat on to supermarket chains. Small slaughterhouse products cost more than at the supermarket. This is justified because they are “of better quality and locally produced”, according to the slaughterhouse staff and apparently affirmed by their customers. Higher prices however do not necessarily establish an economic sustainability of this small business. And as indicated above, this slaughterhouse also aspires to be a site of ‘skilled’ labor—as compared to the many ‘unskilled’ workers of the industrial slaughterhouse, i.e. persons who are quickly trained to do the work of a specific section of the production line. Here, as explained by staff and owner, skill implies a longer and even lifetime of training (the ‘craft’) as well as broader capacity to engage throughout the site. Whilst slaughterers at this site do tend to specialize in specific tasks (either sausage making or killing + carving), they can perform all tasks skillfully if needed- with higher salaries to match. Yet for now at least this slaughterhouse was depicted as economically sound, thanks in large part to their price bracket. The owner described: “I don’t lack orders, quite the contrary. I have to say no to a lot of customers, because we don’t have space in the cooler room for more animals. My biggest worry is the instability of labor. All my slaughterers are old, three out of five are above 70, and I don’t know what to do when they are not here anymore. It is really difficult to get skilled slaughterers.”

Through the focus on slowness and craft of the killing, a concern for animal welfare also came to the fore. For the slaughterhouse workers, animal wellbeing seemed to be part and parcel of a general idea of sustainability. Care for animals is understood here as embodied in the slowness of the site, although such articulations do take shape within a broader interest in the quality and taste of meat for eventual sale (also see MacKay 2023). Much of this also has to do with the facilities at such small slaughterhouses, which can accommodate ‘unstandardized’ animals such as those with large horns and heavy fur that are commonly used for nature preservation (for instance, the Scottish Highland breed, or Skotsk Højlandskvæg). Indeed, many of those slaughtered in the small slaughterhouse serve a dual purpose: before becoming meat for human consumption, they roamed freely in protected areas and their grazing patterns have enabled biodiversity conservation (see e.g. DN 2020). The owner of the slaughterhouse emphasized that ‘supporting’ outdoor production systems (many animals also come from small ‘free range’ farms), and in particular ‘nature preserving’ animals like the Highlands, was central to why her slaughterhouse is more sustainable than industrial slaughterhouses. With this, she positions her slaughterhouse as the supportive final link, enabling free ranging animals and their farmers to live up to a fuller potential, within a more caring and sustainable meat production commodity chain. It is also notable that Danish legislation prohibits the ‘natural’ death of such animals in conservation areas such as due to winter starvation (DN 2020), thus such a final link is a key enabler for such biodiversity / nature management.

The owner exhibited confidence and enthusiasm with regard to developing her business toward greater sustainability. Her business acumen and local entrepreneurial identity was mobilized in recognizing sustainability as a ‘hot topic’ in Danish society. Her sustainability interest converged with an expressed longstanding concern for animal welfare, and the belief that small-scale slaughterhouses are better equipped to deliver such welfare. The sustainability / welfare convergence for her stemmed from her sense that animals that had served the extra purpose of nature protection had also had a good life. She further described that good quality meat comes from animals living good lives, and with good quality meat, people should be able to make do with less.

However, sustainability tradeoffs also emerged, as related to aspects of scale even beyond those noted in the introduction (e.g. resource efficiencies as claimed by industrial sites). Despite their accommodation of unstandardized yet ‘multipurpose’ animals, this slaughterhouse lacked facilities to fulfill further sustainability potentials, not least of skin and organ processing. Many industrial slaughterhouses contain both facilities and trade agreements (often international) that ensure treatment, trade, and eventual use of skins and guts. But here, both parts go to waste. An arrangement with a German company to collect skins for processing elsewhere was severed under the Covid-19 pandemic and could not be re-established. The owner of the slaughterhouse expressed her frustration: “I wish I could treat the skins, I don’t like the thought of so many good skins going to waste. I tried doing the salting of the skins by myself, but it is so hard work and takes so long, so I gave up. I wish the skins were worth more, but as it is now I pay money to get rid of them.” Our interest as noted previously was not to authorize or not this slaughterhouse as ‘sustainable’. With the capaciousness of the term in mind, we were rather interested in their sustainability claims, practices, and dilemmas and moreover, how all of this comes to bear on manifestations of masculinities- the topic to which we turn now.

Masculinities in the ‘alternative slaughterhouse’?

Grasping the masculinities present in this site was achieved much more through observation of activities and an attentiveness to the nature and dynamics of conversations on topics of e.g. sustainability and slaughtering, than by overt questions on the topic. Occasionally, Lise also posed direct, open-ended descriptive questionsFootnote 10 about how it is to be a man or a woman in this site in order to dig deeper. We note here the importance of distinguishing between the empirical and analytical level (Hastrup 2010), and how our analytical focus on exploring masculinities was translated into descriptive open-ended questions to avoid influencing the employees’ answers. As an overview to what follows, we firstly affirm the general characterization of the site as featuring elements of hegemonic masculinity. Yet, we also fold in observed incidences of other, not-so-hegemonic behaviors by men in this space. We also explore the ambiguous character of the female slaughterhouse owner, an unusual attribute in the contemporary slaughterhouse at large. These findings are then reflected upon in terms of their analogous moderation in the everyday through entanglements with sustainability claims and practices.

Hegemonic masculinity appeared in the everyday at this slaughterhouse, most overtly through several manifestations we will describe below, namely: the act of killing, physically strenuous work, suppression of emotions, sexist and sexualized comments and behaviours, and emphasis on mastery and skill. Lise’s field notes (translated to English) document a typical Monday: slaughter day.

“Every Monday was slaughter day. The farmers had transported their animals to the slaughterhouse stable the day before in order for the animals to have time to find calmness in the new setting. The two male slaughterers started their workweek with a coffee at 7:00. Afterwards, they directed the first cow into the kill space using whistling, soft speech and small slaps. One of the slaughterers took his rifle and shot the cow in the forehead. It thumped to the floor, and the second slaughterer took his knife and cut the cow’s throat. An electric wire with a hook dragged the dead cow into the next room and the body was placed on a table cart with her feet pointing upwards. Next, the two slaughterers cut the skin off. Then the body was hung on a hook and all the intestines were removed, after which the body was cut in two and hung in the cooler room. About 15 more animals went through the hands of the two slaughterers that Monday and according to the slaughterers, every Monday.”

Despite the inherent violence of the context, expressions of caring for the animals’ wellbeing of even an affective variety came forth. During one of the killings, the bullet did not hit precisely enough, and the cow suffered for a few extra seconds. The insufficient act was promptly commented upon: “raise your performance, mate, she shouldn’t suffer”. Concern (and care) for the animals was also expressed via comparisons between the treatment of animals in industrial farms and small-scale farms: “I feel so sorry for the animals that are pumped with antibiotics in industrial farms, they can hardly make it to the slaughterhouse without catching pneumonia”.

The slaughterhouse is physically demanding: the temperature is frigid and although a system of movable hooks spared them from excessive lifting, the slaughterers still have to perform hard labor of cleaving the bodies of large animals with an axe, pulling off skins and carrying these and other unused body parts over to the bin. The slaughterers expressed desire for physically strenuous work. One explained that he preferred slaughtering cows over the smaller animals, as he enjoyed using the axe, and that in his experience the slaughterers chose to bear the big pieces of meat on their shoulders despite the hook system because “it makes us feel manly”. This was especially the case for younger apprentices. Such comments probably entailed some playful self-mockery, perhaps for Lise’s sake and/or as a result of her gaze, and moreover highlight the ambiguity and complexity of identities: needing to be manly at the same time as needing to poke fun at this compulsion.

The slaughterers chatted as they worked, including with Lise during the hours she passed with them in observation. One described: “We talk and we joke—that’s what makes it nice to go to work and the days feel shorter.” At one point in which Lise felt the atmosphere would accommodate a more intimate question, she inquired as to how they felt about their work of killing. One answered: “I used to go hunting since I was a little boy, so that’s why it’s not so bad. I think it’s harder to look at, because then you start thinking. When you do it, you just act and you don’t think.” Another added, “After the first time I killed a pig, I had a nightmare all night long. I dreamt that the pigs hunted me. Now I’m fine with it. I couldn’t be a slaughterer, if I couldn’t kill, so I pulled myself together and got over it.” Such sentiments are hardly uncommon in the slaughterhouse; these resonate closely with e.g. the ‘getting on with it’ rhetoric described by McLoughlin (2018, p. 333), where Irish slaughterhouse workers were “reproducing a norm of unemotional work, even though they are constantly negotiating their experiences and emotions.”

While joking and informality can serve to lighten the heaviest of atmospheres, the effect was not quite that for Lise, embroiled in this ethnographic encounter where some joking was overtly sexist, as intimated in our opening lines. “Why don’t you come sit on my lap?” was not an isolated occurrence. “I had two sex diseases by the age of 13 and you haven’t even lost your virginity yet” (uttered by a male more senior worker to the male apprentice), and, “Is your shoulder injury due to excessive masturbation?” (uttered by a male worker to a female worker) are examples of the at least sexualized if not sexist remarks that filled the air and shaped the atmosphere of the place. Sexualized jokes are typically the purview of men, displaying a hegemonic masculinity often to the discomfort of women (as other genders and also some men). While it is unlikely that such jokes were intended to harm (the workers were friendly throughout), and even as they may serve the important purpose of (re)constituting social connections and sense of collectivity, they can still do violence. But to know who is harmed and how would require more prolonged access than we were granted. The female owner of the slaughterhouse meanwhile came to describe to Lise the occasional sexism she endures from male customers, from “shall we sort things out with a roll in the hay?” to a customer sending “dickpics”, as well as a former male employee stalking her and showing himself naked to her in unexpected moments. Such masculine violence in this site emerged not only through the sexism described in the preceding, but also in moments of joviality; one of the slaughterers cut a smiley face in a bull’s testicle and performed a puppet theater to entertain the others.

Masculine dominance was also expressed in the slaughterhouse through the focus on craft as skill and mastery. A subtle power distinction was quickly apparent between the five all-male ‘trained’ slaughterhouse employees, and the three ‘unskilled’ workers responsible for packing (both female) and cleaning (one male). This was evident in skilled workers’ dominance in tone setting and defining what was relevant to talk about (for example their skills). Indeed, stories about winning national and international competitions in sausage-making were shared often during coffee breaks, invoking a fierce competition and pride. Such stories invoke recent analyses of masculinity and food preparation in the public gaze (e.g. contemporary Nordic/European cooking shows dominated by male celebrity chefs) that Leer describes as ‘homosocial heterotopias’, i.e. spaces largely impenetrable to women or at least, carefully distanced from ‘the feminine’ (Leer 2019; 2016). Leer (2018, p. 13) further describes how cooking by male chefs has come to express “authority and connoisseurship”, whereas “cooking in shows hosted by women is portrayed as a way to embrace ‘traditional feminine values’ of nurturing and home management”. Two of the older slaughterers had in the past won several gold, silver, and bronze medals in sausage-making and as such commanded respect from both customers and colleagues. “Until recently, the local slaughterer was a person you looked up to. He was an important figure in the local community”, the owner of the slaughterhouse explained. She added “sometimes it’s a problem, because which recipe to choose? If I choose to base a sausage or liver paste on one gold medalist’s recipe, the other gold medalist will be disappointed. There is a battle going on here and a lot of pride.” Such intersections of celebrated food preparation and hegemonic masculinity may help the slaughterhouse overcome the owner’s fears of future staff shortages, as noted earlier – but also bears implications for the reproduction of problematic hierarchies.

Alongside the numerous overt expressions of hegemonic masculinity described above, a somewhat more ambiguous figuration emerged through the position and characteristics of the female slaughterhouse owner: a rarity in the Danish slaughterhouse universe. Embodying both traditional feminine and masculine values in a workplace highly dominated by traditional (hegemonic) masculinities, the female owner was called and referred to as mummy (lillemor) and similarly referred to her predominately male employees as “my boys”. Several times a day she did rounds in the slaughterhouse, all the while joking, smiling, telling about the latest gossip or simply delivering information from customers about how to cut the meat. When she had time, she made coffee and prepared lunch for everyone with homemade products. She seemed comfortable with showing emotion, openly describing moments of anger, sadness, and joy, as for example when she told Lise that she had wept with pride all the way through a video made of the work in the slaughterhouse and the owner’s experience of engaging in the research project.Footnote 11 She was affectionate, often greeting people with hugs and other forms of physical touch. It was clear that she managed to create a warm and caring family atmosphere in this physically cold and bloody place.

At the same time, the female owner appeared to identify closely with traditional masculine values. She contributed on par with the male workers with sexist comments and jokes, and remarked that she preferred working with men as “they were less complicated and held less grudges than women”. She mentioned how she had more male than female friends, though the female friends she did have were “much like men”. This doubleness of running the slaughterhouse in both feminine and masculine ways reminds firstly that gender is seldom unambiguous, but coexists in a variety of ways. Despite her widespread association of masculinity to men and femininity to women, “All of us possess varying shades of masculinities that are imposed upon us and impact our lives” (Pulé et al. (2021, p. 21). Yet, the multiple and overlapping articulations of traditional feminine and hegemonic masculinity embodied in this person also stem from the power position she occupies as owner, perhaps enabling her overt femininity here as well as the doubleness itself, that may be less tolerated in those with less institutional power. So, what does the owner’s femininity (and masculinity) do in this site? Are these performances serving to open cracks for non-hegemonic ways of being masculine, or are they rather reifying hegemony? With this key question, we turn to a discussion of how forms of sustainability and masculinity converge in this site.

Sustainability as a mediating factor of hegemonic masculinity?

By observing an ‘alternative’ slaughterhouse, we aimed to gain insight into how a sustainability orientation including smaller scale may mediate what is largely a site of hegemonic masculinity. We have described both what sustainability means and looks like in this place and illuminated the site’s multiple faces of masculinity. Here, we bring these together to reflect upon how forms of sustainability come to bear on this workplace. Thus we ask, does the ‘alternative slaughterhouse’ mediate hegemonic masculinities?

The simple answer is: perhaps. Masculinities in this site often – though not exclusively- appeared hegemonic in nature. Sexist and sexualized remarks, indications of suppression of emotion vis a vis the violence of routinized killing, etc. were blatant. Yet there was space for non-hegemonic masculinities as well that to our gaze at least, came forth through their relationship to situated ideas of sustainability. For example, the assertion that good quality meat was a result of caring for the animal and the slow, skilled process of slaughter and processing.Footnote 12 ‘Slow craft’ is linked to “the work of reflection and imagination” (Sennett 2008, p. 294), which seems essential for more caring engagements even in the slaughterhouse, as well as for advancing sustainability beyond resource efficiency. Further, that a small piece of such quality meat can and should replace large quantities of poorer quality meat.Footnote 13 The sustainability orientation as expressed here thus has potential to facilitate less and fewer violent masculine behaviours.

The female slaughterhouse owner appeared to have a special influence on openings for alternative masculinities. Working through the authority and power vested in her as owner, she seemed to be driving the emergence of a sustainability praxis in her workplace in both discursive and material ways. This converges and, importantly, is iteratively strengthened by her practices of traditional femininity (‘mothering’, ‘my boys’, etc.) which strongly shaped the emotional register of the place. Whilst she at times also articulated suggestions of hegemonic masculinity, such as uttering sexist remarks or sexualized jokes on par with those of the male workers, overall, she seemed to cultivate an atmosphere of care and attentiveness that entails and advances particular forms of sustainability and which allows for alternative, non-hegemonic masculinities to emerge. This also suggests the need to be attentive to the conditions under which caring masculinities have the possibilities to rise. Of course, her expressions of both traditional femininity (perhaps ‘complicity femininity’, see Connell 1987) and e.g. sexist jokes could be part and parcel of an uncritical contribution to patriarchal structures. Yet as we can elicit from our empirics including in relation to the observed behaviors and expressions of the ‘men as men’, a caring female authority combined with a sustainability agenda, seems to be fertile ground for alternative masculinities to take root.

But with Hultman and Pulé’s (2018) typology of masculinities in mind, the question is begged: what kind of alternatives? Or more to the point, how alternative are they, really? Here it is helpful firstly to widen the scope and attend to the broader context of Denmark, where sustainability discourse has a relatively long history and strong influence on the general public as compared to other Western countries. Denmark’s broad consensus on the need for a green transition and historical leadership in global environmental debates means that doing ‘sustainability’ is less risky, and even ‘rationale’ (recall the sustainability claims of even the industrial slaughterhouse). But sustainability is a malleable term, and competing sustainable practices and pathways are divisive including in Denmark from past to present (Christensen and Lund 1998). Relatedly, some forms of sustainability at closer glance are not so far removed from hegemonic masculine ideals.

This is where Hultman and Pulé (2018) ‘eco-modern masculinities’ comes forth. This not-so alternative masculine figuration entails some expression of concern for the more than human world, but in ways that fail to challenge an underlying ontology of humans as masters over all else (what they describe as effective ‘greenwashing’), and moreover belies a deeper embodiment of care that would likely call into question the sheer existence of such routinized killing- perhaps the most visceral embodiment of the violence of a hegemonic masculinity. In this ‘alternative’ slaughterhouse in question, the neoliberal logics of eco-modernity / eco-modern man were not overt during the duration of Lise’s visit. Yet the overarching persistence of human mastery and associated hegemonic masculine characteristic of domination were unmissable, even as existing alongside efforts at doing better from environmental sustainability and welfare perspectives. Consider the contradictions that emerge around the emphasis of the ‘craft’ of slaughtering, where animal suffering should be minimized as human enjoyment is maximized (with ‘craft’ too serving to reaffirm hierarchies between workers). While ‘ecomodern masculinity’ as currently conceptualized may not be a perfect fit for this site, the work of Hultman and Pulé remind us to attend to the range of attributes characterizing human/more than human relations including through the lens of masculinities.

What Hultman and Pulé call their most substantial alternative: ‘ecological masculinities’, entails the cultivation and praxis of profound caring relations with other humans and the more than human world, from other animals to ecological systems. The ‘slaughterhouse’ as a particularly gendered institution and site (of any type and scale) could arguably preclude the development of such relations. A persistent question is whether fewer and more care-full killings serve to legitimate the persistence of routinized killing, with a broader context in which “animals are [still] conceptualized not as individuals but as products ready to become meat” (Gillespie 2011, p. 120)- with negative implications for the full attainment of ecological masculinities. One might further ask whether killing ever be non-violent, as ‘care-full’ may suggest.Footnote 14 Critical animal studies scholar Kathryn Gillespie (2011) argues that slaughter is inherently violent and can never be ‘humane’, or kind and caring. What we believe is that killing can be undertaken in non-hegemonic ways, as may be embodied for instance in those committed to an ‘ecological masculinity’. Importantly, this may be achievable through making death and killing as events imbued with meaning, as opposed to the ‘eventless death’ that tends to characterize contemporary slaughterhouses.

In ‘His Name Was Lucio’, de la Cadena and Martínez-Medina (2021) lament the alienation from death present in slaughterhouses of any size, and they explore alternative forms of animal death to provide human food that are marked by ritual, recognition, and intimacy.Footnote 15 Such praxis of interspecies relations is still found in some indigenous communities the world over. Haraway writes that “multispecies co-flourishing requires simultaneous, contradictory truths if we take seriously not the command that grounds human exceptionalism, “Thou shalt not kill,” but rather the command that makes us face nurturing and killing as an inescapable part of mortal companion species entanglements, namely, “Thou shalt not make killable.” (Haraway 2008, p. 80). Taking a cue from Haraway, the problem is not killing; species are intertwined in ongoing and historical relations of eating and being eaten that are at times instrumental. It is the distancing between species, under an ontology of human exceptionalism where hegemonic masculinities thrive, and as embodied in routinized slaughter, that constitutes destructive territory.

Perhaps the alternative slaughterhouse does not constitute an ‘interspecies sustainability’. But if scale entails a spectrum, then the possibilities for animal wellbeing up to and at the moment of death are greater in the ‘alternative’ than industrial slaughterhouse. Here, things are slowed down, noticing becomes possible. Empirically this appeared through, for example, the anger that erupted at poorly done killing, and how slaughterers accompany the animal from stable to customer rather than performing a single task at a conveyor belt station. But although this alternative slaughterhouse is more sustainable on some important parameters as compared to industrial scale slaughterhouses, e.g. it supports small-scale animal husbandry enmeshed in nature conservation and takes social sustainability seriously, it still exists within a broader context of normalized livestock production, i.e. within a system of ‘making killable’. Whether the praxis of the alternative slaughterhouse represents a desirable pathway for just and sustainable futures, is an important question for ethicists, decolonial / ecofeminist scholar-activists, and thriving democratic societies – including those doing the actual work of food production—to continue to debate.

Hultman and Pulé (2018) ask us to see ‘ecological masculinities’ as a journey, a process, and eventually an ‘exit politics’ from hegemony. Perhaps some of the human workers are on this journey. Perhaps, their growing attention to particular sustainabilities will further facilitate a transformation of their masculinity away from the strictures and harms of hegemony. This would not be unthinkable also when seen within the Danish context where attention to gender equity is relatively widespread and men’s contributions to carework is relatively advanced (e.g. Preisler 2022). From acts of support amongst co-workers to attention to the suffering of those sent to slaughter, the opportunity for caring and intimate relations was distinct here to what we could expect of industrial sites, and we believe this stems at least in part to this site as an ‘alternative’, specifically in relation to scale and following at least some of their ideas and practices of ‘sustainability’. Such openings exist in different settings in a variety of expressions. From farmers who name and hang photos of their cows in their homes (Despret 2016) to the millions of humans who grieve deeply for their lost animal companion (Butler 2004, p. 26), such acts of memory are ways of saying thank you to animals and making them ‘count as lives’ (Despret 2016). Practices like these have the potential to transform meat production into a more ethical and sustainable form of respectful multispecies co-living. We remain curious about and inspired by the openings against hegemonic masculinities that certain forms of sustainability may facilitate.

What lessons can we glean, that may be brought to bear on food systems more broadly as we move toward a ‘green transition’ of agriculture in Denmark (e.g. State of Green 2021)? We believe that structural as well as imaginative aspects of food production matter tremendously. In the alternative slaughterhouse, imaginations of sustainability and moreover of what sorts of food systems one desires are able to grow. It is important to acknowledge the ‘sustainability’ tradeoffs of industrial vs. ‘alternative’, such as aspects of scale that can boost resource efficiencies and reduce waste. For some, this constitutes a compelling argument in favor of advancing the industrial model (e.g. WRI 2021). Yet other forms of sustainability, e.g. those encompassing substantial human social (e.g. worker wellbeing) as well as interspecies and non-human wellbeing, appear to be precluded from the industrial model. We must continue to question what counts as ‘sustainable’ (Blatz 1992; Sanjuán 2023), asking what is lost under such narrow notions of sustainability, and how such narrow notions infuse other aspects of the social world, such as the sustainability (read: durability) of hegemonic masculinities.

Concluding remarks

In this paper, we set out to investigate the connections between forms of sustainability and masculinity through a study of everyday life in a Danish alternative slaughterhouse. We have presented how sustainability was understood and undertaken in this slaughterhouse through initiatives to reduce food waste, through promoting the notion that good quality meat (related to specific forms of animal life and death) can reduce overall meat consumption and through supporting small-scale husbandry that contributes to nature conservation. We have shown how such alternative slaughterhouses entail ‘sustainability’ tradeoffs; despite their sustainability practices, they are less able to make use of slaughter byproducts than large-scale industrial slaughterhouses with their embeddedness in globalized economies of scale. Regarding masculinities, we have presented how hegemonic masculinities were present and alive in e.g. expressions of sexist jokes but moreover as embedded in the very fact and acts of routinized killing. However, other, gentler masculinities also came forth through acts of care amongst the workers and towards the animals.

Were these just cracks? Can small streams converge into floods of transformation?Footnote 16 The alternative slaughterhouse may constitute a site where richer sustainability forms can come into being. We argue that sustainability and masculinity are intertwined in the sense that the sustainability orientation of the alternative slaughterhouse has the potential to nourish alternative masculinities, and alternative masculinities have the potential to broaden our understanding and practice of particular sustainabilities. Gentler masculinities have better possibilities to grow here than in the industrial slaughterhouse, through slowness and attention towards the animals and other humans, thereby potentially enhancing care, recognition, and interrelatedness rather than fostering domination, alienation, and exploitation. Certainly, the questions of whether and how sustainability is a mediating factor of hegemonic masculinity might as well be questions of whether and how non-hegemonic masculinities give rise to sustainability, not least in a country as Denmark with it relatively large consensus on the need for and actions toward sustainability as well as gender equality. Whilst we focus on the effects of ‘sustainability’ on masculinities, we no less value the potentials of non-hegemonic masculinities in promoting particular forms of sustainability.

Sustainability in meat production is not just a question of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. It is also a question of enacting care in non-hierarchical multi-species relations. Breaking down patterns of hegemonic masculinities and nourishing the growth of alternative caring masculinities is key. The alternative slaughterhouse is a window for understanding the potential for such a transformation. The slow skillful work of a slaughterer in the alternative slaughterhouse has the potential to develop into ways that are less eventless (de la Cadena and Martínez-Medina 2021) and more thankful (Despret 2016).

Our study points to a need for further research of this fertile territory for alternative, perhaps ecological masculinities to grow, drawing from the conceptual groundwork of ecofeminist and masculinities scholars (e.g. Connell 1990; 2017; MacGregor and Seymore 2017; Hultman and Pulé 2018; Pulé et al. 2021; and more). We hope for further exploration of the links between particular sustainabilities and masculinities. Despite our optimistic conclusions, the figuration of ‘ecomodern man’ presents troubling implications for ‘sustainability’ pathways. Care for environment does not necessarily translate into social, gender, and ecological justice. We also call for more observation studies in slaughterhouses and across different settings, in particular new interrogations into the rise of alternative slaughterhouses and their potentials, including to better grasp and advance the sustainability / masculinities nexus. Participatory action research and similar approaches in particular could provide learning and impact for all involved, as a means to mitigate prescriptive solutions and explore potentials for collaborative transformations. While crucial in any context, such approaches are especially important in sites where e.g. slaughterhouse workers struggle under conditions of more extreme oppressions and domination.

We conclude by calling for more attention to what types of sustainability are unfolding under so-called ‘green transitions’ in many countries including Denmark, and their iterative relations with hegemonic, but perhaps alternative, masculinities. As we and other have made evident, a sustainability orientation in general cannot be assumed to lead to non-hegemonic, caring and ecological masculine expressions. Continued attention to this nexus is critical to crafting socio-ecologically just futures that embody social, ecological, and interspecies sustainabilities.

Notes

Also see Upton Sinclair’s classic muckraking novel The Jungle, published in 1906, which helped to reveal the terrible conditions of food production in the Chicago stockyards at the time.

What constitutes non-industrial is a question of, at minimum, relative aspects of size and speed- or what we consider scale; also see Blanchette 2018.

While this move does largely apply in our case country of Denmark, it is not uniform in all countries; Sweden for instance is an exception, where larger slaughterhouses are situated close to cities (Bååth 2018).

The Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries of Denmark defines this categorisation. Large slaughterhouses are defined as those slaughtering at least 35.000 animal-units per year. Animal-units are calculated based on the type and weight of the animal, for example one bovine above 150 kilos counts as 4 units, bovines below 150 kilos counts as two and sheep counts as 0,5 (Retsinformation 2023).

‘Animal units’ are the official measure of slaughterhouse processing, whereby a pig is the baseline of a single (1) unit; cows can constitute four units, whereas chickens for instance constitute just 0.067. Pigs are likely the baseline given their prominence in Danish animal production.

As an example, in 2022 the small slaughterhouses in Denmark slaughtered 6.500.528 ‘animal units’, whereas the big slaughterhouses slaughtered 26.718.805 animal units (Danish Veterinary and Food Administration 2023).

The situated meaning of skill is described in the empirical section below, but in brief implies relatively more training toward ‘craftsmanship’ and the ability to perform a greater range of tasks, whereas in industrial sites, workers are often initiated through short courses, to focus on fewer tasks. We also recognize the problematic nature of the skilled/unskilled distinction that has be used to legitimate low pay, see e.g. Auguste (2019).

Following a Gramscian concept of cultural hegemony.

Theoretically, this way of categorizing masculinity may feel too rigid; this archetype could arguably be better understood as a fluid gender practice containing elements of all gender performances (i.e. feminine, masculine and other gender practices). In explicating their archetype, the authors recognize and work with the ontological reality of many ‘men qua men’ and the often entrenched resistance to associations with femininity, and moreover, the urgent need for viable alternatives.

The descriptive open-ended questions are inspired by Kvale (1994) and Spradley (1979). By ‘descriptive’ we mean questions that urge the respondent to share detailed everyday life experiences. By ‘open-ended’ we mean questions that do not lead the person in a certain direction but encourage them to share their perspectives in a non-judgmental way.

The video was made by Raketfilm.

This point links to a growing body of research exploring the connections between meat consumption and masculinity, with a focus on evolving aspects of quantity / quality as well as men’s role in and sites of food preparation, in addition to Leer’s works cited earlier (e.g. (2019) also see e.g. Bååth (2018) for a helpful review and Neuman et. al (2015).

In this essay the authors in fact typify even a small though modern slaughterhouse as characterized by eventless death, and compare this to the even slower, much smaller scale killing of animals done by one man as a service to his local community. This way of killing took a full day for a single bull. This calls into question the perhaps ‘inter-species sustainability’ of even the ‘alternative’ slaughterhouse as we have typified it in this article. In other words, in the essay the authors challenge the phenomenon of the slaughterhouse as a site at all, no matter its scale and sustainability orientation.

To mimic the elegant watery metaphors employed in Hultman and Pule’s (2018) description of the potential steps toward masculine ecologicalization.

References

Ackroyd, S., and P.A. Crowdy. 1990. Can culture be changed? Working with raw material: The case of the English slaughterhouse workers. Personnel Review 19 (5): 3–14.

Auguste, B. 2019. Low Wage, Not Low Skill: Why Devaluing Our Workers Matters. Forbes Magazine. https://www.forbes.com/sites/byronauguste/2019/02/07/low-wage-not-low-skill-why-devaluing-our-workers-matters/. Accessed 6 June 2023.

Bååth, J. 2018. Production in a State of Abundance. Valuation and Practice in the Swedish Meat Supply Chain. Uppsala: Department of Sociology, Uppsala University.

Baker, K. 2013. Home and Heart, Hand and Eye: Unseen Links between Pigmen and Pigs in Industrial Farming. In Why We Eat, How We Eat, ed. E.J. Abbots and A. Lavis, 53–74. New York: Routledge.

Blanchette, A. 2018. Industrial Meat Production. Annual Review of Anthropology 47: 185–199.

Blanchette, A. 2019. Making Monotony: Bedsores and Other Signs of an Overworked Hog. In How Nature Works, ed. S. Besky and A. Blanchette, 59–78. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Blatz, C.V. 1992. The very idea of sustainability. Agriculture and Human Values 9: 12–28.

Bocci, P. 2018. Tangles of care: Killing Goats to Save Tortoises on the Galapagos Islands. Cultural Anthropology 32 (3): 424–449.

Butler, J. 2004. Precarious life: The powers of mourning and violence. London: Verso.

Christensen, P., and H. Lund. 1998. Conflicting views of sustainability: The case of wind power and nature conservation in Denmark. Environmental Policy and Governance 8 (1): 1–6.

Connell, R. 1987. Gender and Power. Redwood City: Stanford University Press.

Connell, R. 1990. A whole new world: Remaking masculinity in the context of the environmental movement. Gender and Society 4 (4): 452–478.

Connell, R. 2017. Foreword: Masculinities in the Sociocene. In Men and Nature: Hegemonic Masculinities and Environmental Change, ed. S. MacGregor and N. Seymour, 5–8. Munich: RCC Perspectives.

Connell, R., and J.W. Messerschmidt. 2005. Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept. Gender and Society 19 (6): 829–859.

Copenhagen Association of Slaughterers. 2009. Slagterlaugets ældste historie. https://www.slagterlauget.dk/klenodierne/slagterlaugets-aeldste-historie. Accessed 5 June 2023.

Daggett, C. 2018. Petro-masculinity: Fossil Fuels and Authoritarian Desire. Journal of International Studies 47 (1): 25–44.

Danish Crown. 2016. Amazing milestone to be reached by Horsens Abattoir. https://www.danishcrown.com/da-dk/kontakt/presse/nyheder/Amazing-Milestone-to-be-Reached-by-Horsens-Abattoir/ Accessed 7 May 2023.