Abstract

Corporate actors in capitalist food systems continue to consolidate ownership of the means of production in ever fewer hands, posing a critical barrier to food sovereignty and to an agroecological transition. Further, corporate influence on the state is often direct and blatant, but there are also more insidious governance barriers– hegemonic structures of power and ‘common sense’ theories of value that exclude smallholders and local communities from participation in decision-making processes. This is especially pertinent in land use planning and in building processing facilities, usually referred to as ‘value chain infrastructure’, or what I call the ‘intrinsic infrastructure of agroecology’. Using a case study approach, I evaluate the successes and failures of two campaigns for agrarian reform in the Australian state of Victoria, concluding that civil society must act collectively to gain the thick legitimacy needed to work with the state to enact enabling policies for an agroecological transition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

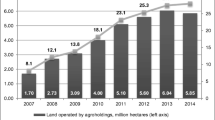

Corporate capture of all aspects of the food system is escalating, speeding the decline of small- and medium-scale farms, and the erosion of rural communities globally (McMichael 2009, 2013; Muir 2014; Berti 2020), a consequence of capitalism underpinned by the rise of neoliberalism. The Australian government today claims to support agriculture through de-regulation and a focus on competitiveness and export markets (Richards et al. 2016; Iles 2020), yet, despite this pro-competitive rhetoric, for many farmers options for processing and selling their produce are limited. In the years 2016–2017, this paradigm has resulted in just 14 per cent of the nation’s farms enjoying 59 per cent of market value (ABARES 2021: 4). In the corporate food regime, industrial livestock are bred to maximise productivity and profitability, resulting in uniformity of animal carcasses suited to the standardisation required by high-volume slaughter facilities such as those processing up to 2,500 pigs per day (DVP 2023). Smallholders’ access to the shrinking number of abattoirs (slaughterhouses) is rapidly diminishing, and the demand for carcass uniformity is another barrier to those rearing slow-growing heritage breed livestock on pasture, whose smaller carcasses are frequently damaged by the highly mechanised processing equipment. The concentrated processing sector also brings heightened food security and food safety risks (Wallace et al. 2021), as witnessed when many abattoirs were forced to close during COVID outbreaks. In the state of Victoria, abattoirs were throttled to 80 per cent capacity during repeated restrictions, leaving some small-scale livestock farmers with no access to processing for months at a time, as larger producers were given priority.

Since 2021, global meatpacking giant JBS has significantly increased its share of Australia’s meat industry, purchasing Rivalea, a vertically-integrated operation of intensive pig farms, abattoirs and smallgoods companies in southeastern Australia, and Huon Aquaculture, Australia’s second biggest salmon producer. The Rivalea acquisition gave JBS control of more than a third of pig kills in Australia, leading to a government inquiry, which concluded ‘that JBS, due to its downstream businesses, may have a greater incentive (than the current majority owner, Rivalea), to frustrate or foreclose access to third party service kills’ (ACCC 2021). Yet, subsequently the ACCC approved the acquisition. Just months later, JBS decreased smallholders’ access to the abattoir from five to three days per week. In addition to inhibiting smallholder access to slaughter across the globe, JBS has a substantial legacy of social and ecological destruction at direct odds with the values of smallholders still reliant on their services. Not only have the Brazilian owners been found guilty of high-level corruption (Sect. 2020), there have been allegations of slave-labour practices, illegal deforestation, food safety breaches, and animal welfare violations (Global Witness 2022).

JBS’ increasing control of slaughterhouses globally exemplifies the loss of what Stahlbrand (2018) calls the ‘infrastructure of the middle’– abattoirs, grain mills, dairy processing, and territorial markets– a foregone consequence of capitalism. Stahlbrand’s work builds on the concept of an ‘agriculture of the middle’ (Kirschenmann et al. 2008: 3), described as mid-sized farms that ‘operate in the space between the vertically-integrated commodity markets and direct markets’, and on the ‘missing middle’, by which Morley et al. (2008: 2) assert a need for a ‘mechanism by which small producers can collectively access a middleman facility that enables them to trade with large customers’. The need for a middleman is ‘common sense’ in the Gramscian sense, the largely unconscious and uncritical ways of understanding the world in certain places and times (Gramsci 1971). Scholars of ‘the middle’ rarely contest the hegemony of neoliberal capitalist commodity markets in their analysis, but instead propose ‘capitalocentric’ (Gibson-Graham 2006) solutions for small- and medium-scale farmers to continue to operate by aggregating their efforts in order to access middlemen to process and distribute their produce within commodity markets.

Common sense advocacy for such middle infrastructure serves a neoliberal discourse of policymakers and public health experts that solutions are found in the market. Such a lens fails to centre smallholders’ knowledge, territories, and sovereignty (Giraldo & McCune 2019) to build solutions collectively for the infrastructure that is intrinsic to agroecological production, with aims to re-embed food systems in local economies (Wezel et al. 2009). Historically, and still today in many parts of the Majority World (a.k.a. the Global South), the notion of a ‘supply chain’ makes little sense as smallholders grow, harvest, process, and distribute their produce in local ‘nested markets’ (van der Ploeg et al. 2012), or ‘the complex of supportive interconnections shared by peasants and communities’ known as the ‘peasant food web’ (ETC 2013). As the process of re-peasantisation counters the longer process of de-peasantisation globally, smallholders are (re)turning to direct sales and social solidarity economies, and in doing so, recognising the need to (re)gain control of the means of production (van der Ploeg 2008). In these models, instead of a middle, there is a web of smallholders embedded in local communities– feeding them food, not commodities - and mending the metabolic rift by doing so (Wittman 2009). Van der Ploeg et al. (2022: 20) point to the transformative nature of this work, writing:

We think that the movements that currently actively try to change parts of the socio-technical world by introducing novel ways to produce, distribute and consume and thus pushing back the immediate control and impact of capital should be understood as engaged in what Gramsci (1971) called the struggle for hegemony (see also Holt Giménez and Shattuck 2011 and Borras 2020).

Agroecology asserts the importance of economic diversification through farmer-owned or controlled intrinsic infrastructure, not to access capitalist markets, but to enable convivial food production to feed local communities (Gliessman 2007; Rosset and Altieri 2017; Wezel et al. 2009; van der Ploeg et al. 2022), fundamentally advocating for autonomous food webs rather than merely swapping out a link in the chain.

My understanding of these issues goes beyond debates in the literature, because my husband and I are small-scale heritage-breed livestock farmers, and the abattoir purchased by JBS in 2022 is the one our farm has used for more than a decade. We are part of a ‘new peasantry’ in Australia (Jonas and Gressier, Forthcoming) engaged in building agroecology as a life and livelihood on our community-supported agriculture (CSA) farm on unceded Dja Dja Wurrung Country. We share rent-free land in relations of reciprocity with a market garden run by Ngarrindjeri and Narungga man Josh, and settler Rex, in an emergent silvi-agriculture system, establishing what we all intend to be a beaconFootnote 1 for the principles, practices and politics of agroecology. A scientifically and experientially justified practice of agriculture that is sensitive to the ecosystems in which it is situated, and that fosters the democratic participation of farmers in the food system, agroecology has recently emerged in Australia as a more radical wing of sustainable farming that looks to the global movement of peasants and Indigenous Peoples in developing a politics and praxis of undoing and redoing ways of thinking and living anchored in decolonial epistemologies and ontologies (Mignolo and Walsh 2018, 120; Meek 2014; Micarelli 2021).

On our farm, pasture-raised pigs are fed surplus produce from other food and agriculture systems in Victoria (e.g. spent brewers’ grain and whey), creating a net ecological benefit by diverting many tonnes of organic material from landfill, as we rejected industrial grain feedstock early on to extricate ourselves from commodity supply chains. Ten years ago, we built a butcher’s shop, ‘intrinsic infrastructure of agroecology’, or what van der Ploeg (2008) also calls ‘patrimony’ for the farm that strengthens our autonomy, resilience and capacity for social reproduction, and I became the resident meatsmith. The facility is shared with several other ‘agroecology-oriented farmers’ (González & López-GarcíaL-Gar 2021) at cost, and we are now in the process of building a collective micro-abattoir on the farm. Surplus nutrient from butchering– and in future, slaughter– is processed in Audrey, a rotating drum composting vessel built by my bricoleur husband, and then recycled paddock to paddock as rich fertiliser for the market garden vegetables.

I call the infrastructure of processing and distribution ‘intrinsic’ because at the heart of agroecology is collective autonomy, which requires self-determination, participation, economic diversification and a reduction in external inputs. These aspects of agroecology, along with synergy, co-creation of knowledge, soil and animal health, connectivity and more (Gliessman 2007) form the metabolism of agroecology-oriented farming (Wittman 2009). The infrastructure that assists with the transformations of animal lives into meat for human nourishment, of produce into products, is an essential characteristic of farming livestock for food, critical to the system of feeding people within a nested market. Building physical infrastructure supports the return of knowledge and skills back into rural communities, reducing exposure to the risks inherent in participating as the least powerful actors in the commodity supply chain, and retaining full value– economic, but also ecological, social, cultural– aligned with community values. It also serves to mend the metabolic rift by returning fertility to the soils from where it came (Wittman 2009).

While values are generally considered intrinsic to the people who hold them, formed largely through cultural norms and discourses, ‘value’ is understood as extrinsic and assigned, based on an object’s properties or price (Kallio 2020). The common sense formation of value extrinsic to values is therefore easily distorted by capitalism’s bias for exchange rather than use value, and as a consequence, reductive financial values are prioritised at the expense of others. In her ethnographic study with food collectives in Finland, Kallio (2020: 1105) found instead that the ‘formation of value is a dynamic, relational and continuous process’ and in fact ‘value is intrinsic to and emerging from action.’ Following Micarelli (2021: 5), who asserts that ‘value then, is not disjointed from values’, in this paper I argue that to build and operate the infrastructure needed by agroecology-oriented farmers, we must conceive of and relate to it intrinsically within the metabolism of the farm, aligning value realisation with our values of reciprocity and custodianship.

This paper challenges the ‘capitalocentric’ (Gibson-Graham (2006) framing of ‘value’, ‘middle’, and ‘alternative’, because ‘unsettling the hegemony of capitalism involves opening up conceptual, discursive, affective, and political spaces for enlarging our economic and political imaginary’ (Butler and Athanasiou 2013: 40). My field of study encompasses smallholders, some aligned with agroecology and food sovereignty, and some more conventional small-scale farmers aligned with regenerative agriculture. While the new peasantry’s agroecology-oriented farming efforts are detailed elsewhere (Jonas & Gressier, Forthcoming; Jonas and Trethewey 2023), here I examine their political efforts, from the ‘everyday politics’ (Kerkvliet 2009) of peasants and communities to the ‘advocacy politics’ of the Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance (AFSA). My intention is to address the lack of empirical research identified by López-García and Carrascosa-García (2023). The findings strongly support the oft-cited importance of forming democratic associations to collectivise advocacy towards transformative rural development efforts (Rosset and Altieri 2017; Chappell 2018; Wright 2021; Wagenaar and Prainsack 2021; López-García & Carrascosa-García 2023). Moving away from Alternative Food Network framing to the autonomous food webs of agroecology ‘as farming and framing’ (Rosset and Altieri 2017; Mier et al. 2018) is an intervention intended to move these debates forward towards emancipatory agroecologies (Giraldo & Rosset 2022).

My positionality in this paper as an agrarian-scholar-activist is reliant on what anthropologist Scott (1998: 221) calls mêtis– a knowledge co-produced with land and local experience that is ‘a mode of reasoning most appropriate to complex material and social tasks where the uncertainties are so daunting that we must trust our (experienced) intuition and feel our way’– in dialogue with institutional and social-movement-gleaned knowledge, to practice, amplify and ‘massify’ (Mier et al. 2018) agroecology one day at a time (Pimbert 2018). Since 2014, I have been part of the Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance (AFSA), a farmer-led anti-capitalist and anti-colonialist civil society organisation working for the radical transformation of our food and agriculture systems. I also played a key civil society role in the case studies considered in the pages that follow. According to Hale (2001: 14), I am a ‘militant’ rather than a detached observer, ‘a committed participant and learner in the process of research.’

Scott (1998: 7) captures well the conundrum of civil society’s relations with the state, asserting that ‘is the vexed institution that is the ground of both our freedoms and our unfreedoms.’ To wit, while the Australian federal government fails to protect Australian society from corporate capture of the ‘infrastructure of the middle’, some state and local governments are responding to community initiatives to build territorial infrastructure in service of autonomous food webs, through policy reform, funding and coordination. And yet, where governments get involved in community-led development projects, they often fail to deliver the needed transformations. Taking as given that the state has an important role to play in protecting the public interest, including in the provision of essential services, I explore government-civil society social relations that can impel or impede the development of the intrinsic infrastructure of agroecology. In particular, I point to the importance of forming democratic associations that develop ‘thick legitimacy’ (Montenegro & Iles 2016) with the state as key to successful relations, and expose the tyranny of expertise as a key barrier (Pimbert 2018; Rosset and Altieri 2017; Giraldo 2019; Giraldo & Rosset 2022).

Having established the need for an intrinsic infrastructure of agroecology, I present a genealogy of smallholders working alternately in collectivised or atomised ways, which illustrates empirically the ways that advocacy politics by democratic associations can succeed, and how the everyday politics of smallholders can be an internal impediment or a tactic to influence. First, I briefly sketch our farm’s development of infrastructure intrinsic to agroecology and attempts to collectivise local farmers. The next example details the collective efforts of the democratically constituted national organisation representing small-scale farmers and allies, the Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance (AFSA), in holding the state accountable for democratic consultation with smallholders, marking a change from a long practice of consultation solely with large-scale agribusiness peak bodies, which led to positive outcomes for the agroecological transition. The next example analyses my local community’s experience of working with local government to build a ‘hub for premium produce’ through an Artisanal Agriculture Pilot Project, in which farmers participated individually rather than as members of a democratic association, and were unable to prevail against the hegemony of expertise to achieve transformative actions. Using Mier et al. (2018) framework of eight key drivers to take agroecology to scale, I analyse the efforts reviewed in the case studies to show why one succeeded and the other failed, and apply this growing understanding to the ongoing example, which is the extended struggle of the smallholders who have formed a meat collective out of years of shared use of our existing butcher’s shop to build a micro-abattoir here on our farm. This struggle is so current I have each day had to choose between fighting the administrative battles or writing about them in this paper. While I cannot yet report on the success of this example, I will share the tactics we are using to try to build the final piece of intrinsic infrastructure on our farm.

From anonymous to alternative to autonomous: the intrinsic infrastructure of agroecology

In response to the erosion of local food economies under the corporate food regime globally, there has been a steady growth in alternatives to its commodity processing and distribution infrastructure. These alternatives are typically grouped under the labels of ‘alternative food networks (AFNs)’ (Whatmore et al. 2003; Rossi 2017; Blumberg et al. 2020; Edwards 2023), or ‘alternative agri-food networks’ (AAFNs) (Goodman 2003; Andrée et al. 2010). According to Rosol (2020: 53), ‘AFNs can be conceptualized as alternative economic networks that seek to transform production-consumption relations by providing a spatial, economic, environmental, and social alternative to conventional food chains.’ AFNs can refer to: short food supply chains (SFSC) (Renting et al. 2003; Watts et al. 2005), civic food networks (CFN) (Renting et al. 2012; Smith 2023), and values-based food chains (VBFC) (Stahlbrand 2018). There are early and sustained critiques of what ‘alternative’ both denotes and connotes, some contesting the alterity of AFNs and making visible the ways in which they are variously capitalist, alternative capitalist, or noncapitalist (Watts et al. 2005; Gibson-Graham 2006; Andrée et al. 2010; Wilson 2013; Rosol 2020; Edwards 2023). However, Blumberg et al. (2020: 14) argue that ‘theories of alterity have fallen short on providing the tools to understand how actually existing AFNs succeed or struggle within a capitalist economy.’ AFNs are frequently put forward as notable examples of diverse economies (Rosol 2020), yet much of the AFN literature describes incremental rather than transformational assemblages designed to supply commodity markets.

There are distinct analytical approaches to understanding the material and socio-ecological functions of AFNs across the disciplines of sociology, economics, anthropology, political economy, and political ecology, the former typically market-facing and the latter more often rooted in land and territories. At the market-facing end of the spectrum, Reckinger’s (2022) review of the AFN literature found that the logic varies between territory, market and social mobilisation. SFSCs, she argues, follow a market logic that focuses on shortened chains with ‘territorial flexibility’ and relative blindness to civic associations, public institutions, and governance arrangements. On the other hand, while she shows that CFNs follow a logic of social mobilisation and shared governance, critical agrarian scholars González de Molina and López-García (2021) argue that the focus on alterity driven from the consumption end of the supply chain limits the transformative potential they assert is present in peasant-led ‘agroecology territories’. In an attempt to socialise and reterritorialise AFNs, Reckinger (2022) proposes the term Values-based Territorial Food Networks (VTFNs), which emphasise values, place-based initiatives, and networks of cooperation that steer their governance. However, like most AFN literature, Reckinger fails to critique the capital-centric neoliberal approaches of many AFN developments (Watts et al. 2005; Wilson 2013; Rossi et al. 2019). AFNs frequently emphasise transparency, trust, and moral and ethical values embedded in products, but Gonález de Molina and López-García (2021) critique common links with ‘quality labels’, which mostly benefit large, non-local actors.

What is striking across most AFN literature is the almost complete absence of discussion of agroecology or peasants as protagonists, or the potential of AFNs to ‘change capital from below by subverting social relations’ (Giraldo 2019: xi). Yet in the global movement of peasants, there have long been calls for and work towards a renaissance of local, community-controlled processing infrastructure (van der Ploeg 2008; McMichael 2009; Rosset and Altieri 2017), as diminishing smallholder access has created an urgent need for alternatives to commodity infrastructure (CSM 2016). Indeed, level four of Gliessman’s (2007) ‘Five Levels of Transition Towards Sustainable Food Systems’ emphasises the relational rather than transactional structure of reformulated AFNs that connect eaters with farmers directly. Mier et al. (2018: 653) identify that AFNs are not a requisite feature of widespread adoption of agroecology, citing Zero Budget Natural Farming (ZBNF) in India and CaC in Nicaragua, however, they ‘suggest that transformative potential is enhanced when movements use markets as spheres of sociopolitical action.’

Focusing more frequently on developments and resistance in the Majority World (aka the Global South), critical agrarian studies scholars point out that autonomous local food systems (Shattuck et al. 2015) were never entirely lost, and are sites of emancipatory potential (Giraldo & Rosset 2022) rather than simply ‘alternatives’. Van der Ploeg et al. (2012: 139) refer to these as ‘nested markets’, a term used widely by the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and social movements. The anonymous markets of the corporate food regime are starkly contrasted to the collective autonomy of nested markets, which build social wealth and associated resilience (Wilson 2013; Giraldo & Rosset 2022; van der Ploeg et al. 2022; Pimbert 2023; van der Ploeg et al. 2012). Reframing AFNs as ‘autonomous food spaces’ to emphasise the importance of the distinction from anonymous markets, Wilson (2013: 728) notes that:

a critique of capitalism or an anti-capitalist stance does not mean that autonomous food spaces have rid themselves of the vestiges of capitalism, but rather that they have a commitment to dis-engage from these systems and ways of being to imagine and create new social and economic realities.

The closing of cycles and market autonomy are ways to revalorise peasant food and cultural knowledge and its adaptability to changing circumstances (González & López-García 2021), leading to better sustainability outcomes as peasants and Indigenous Peoples are well established as the best custodians of biodiversity (cf. FAO 2019; IPBES 2019). Introducing ‘Agroecology-based Local Agri-food Systems’ (ALAS), González and López-García (2021) write that these agroecology territories should reflect the metabolism of nature to succeed. They argue (1062) that ‘the denser one’s network of interrelationships and internal circuits, the more sustainable it will be, and the less energy and materials external to the system it will require’.

There are echoes of Wittman’s (2009: 806) assertion that the food sovereignty movement has the potential to ‘rework the metabolic rift’, ‘mending the socio-ecological metabolism between society and nature’ and supporting rural livelihoods. Similarly, anthropologist Giovanna Micarelli (2021), who works with Indigenous Peoples in the Amazon, asserts that ‘it is necessary to set aside the onto-epistemological framework that sees society as separated from nature, body from mind, subject from object, and the individual from the collectivity’. Instead of understanding commons as resources or as social processes, a relational ontology that values commons as ‘life made in common’ reconfigures value and senses of self in transformative ways that support our capacity to meet our mutual obligations with land and each other. Micarelli elucidates the possibilities offered by indigenous relationality to expand and deepen conceptions of food sovereignty and decolonial praxis, opening up the possibilities to understand the socio-ecological processes underway within the new peasantry developing a custodial ethic (Jonas & Gressier, Forthcoming).

Other weaknesses in the AFN literature include the often individualised analysis and lack of empirical research into the organisational dynamics that prohibit or promote the growth of ‘agroecology-oriented farmers’ groups’ (AOFGs). Agroecology is an unflinchingly radical project, ‘not a label or an adjective for describing certain products or ways of producing; rather it is an approach featured as ‘the ecology of the entire (agri-) food system’ (Francis et al. 2003; Mason et al. 2020)’ (López-García and Carrascosa-García 2023: 1001). According to López-García and Carrascosa-García (2023), AOFGs are critical for the development of ALAS and highlight the importance of a food sovereignty orientation to go beyond what is sometimes a merely technical approach of ‘agroecological farmers’. Citing Mier et al. (2018: 645), who famously show that ‘social organization is the culture medium upon which agroecology grows,’ the authors insist that there is ‘a pressing need to further study the way in which organic and agroecology-oriented farmers are organizing themselves in order to address local logistics and marketing challenges, especially in the Global North’ (1000).

This paper responds to the call to analyse the ways that smallholders are organising themselves, both living and bearing witness to a ‘life made in common’ approach to the development of the intrinsic infrastructure of agroecology that foregrounds the relations rather than transactions between atomised farmers, produce, or eaters. It demonstrates the importance of forming collectives, associations that develop ‘schools of democracy’ (Wagenaar and Prainsack 2021), which can act in solidarity to monitor powerful elites. Van der Ploeg et al. (2022: 20) further underscore Gramsci’s assertion of the power of the people when they are collectivised:

According to Gramsci the clues are to be found in the social movements themselves, in their struggles and in the ‘formation of a collective will’. ‘Through these movements and only through them can a hitherto subaltern class turn itself into a potentially hegemonic one […]. Only in this way can it […] become the engine of transformation’ (Hobsbawn 2011, 331). Peasant markets are building blocks of counter-hegemony, demonstrating in vivo the transformative capacities of current social movements. This is why it is so important to empirically study ‘the emergence of a permanent and [loosely] organized movement– [that is] distant from a rapid “explosion”– down to its smallest capillary and molecular elements (as Gramsci calls them)’ (331).

While hegemonies of expertise that undermine the autonomy and participation of peasants and local communities are cultivated by state and private elite actors, civil society is influenced by prevailing norms and discourses that uphold hegemonic ideologies, through the adoption of dominant language, values, and ‘common senses’ (Gramsci 1971), which further entrench existing power dynamics. By uncritically accepting and reproducing these norms, civil society unintentionally perpetuates hegemonic structures. The potential for complicity is greatest when civil society fails to critically analyse its own actions, relationships, and impact on power dynamics. By recognizing these challenges and striving for inclusivity and autonomy, while exposing institutional policies, structures, and actors, civil society can play a more transformative role in challenging hegemony.

The case studies below were chosen to show the very material impact the state has on the capacity of smallholders to operate viable, agroecology-oriented farms, and to collectively develop the intrinsic infrastructure of agroecology. The cases empirically demonstrate the importance of participatory democracy in the agri-food system inclusive of farmers and social movements, concluding that ‘this is the least co-optable way to understand the concept of food sovereignty, which radically challenges the corporate food regime’ (González & López-García 2021: 1070). They show that by building the collective strength of AOFGs and the development of thick legitimacy with the state, the enabling policies to support an agroecological transition are achievable.

Emancipatory alternatives

Dja Dja Wurrung Country: an emerging autonomous food web for agroecology

Hepburn Shire is a vibrant rural community on unceded Dja Dja Wurrung Country in what is now called the central highlands of Victoria, Australia. The Land (djandak) is mother to remaining scar trees, rock wells, seed grinding grooves, oven mounds, and shell middens (Stewart 2009), in addition to Djaara (the people of Dja Dja Wurrung Country) and other First Peoples and settler populations. The broader community is increasingly demanding the return of Dja Dja Wurrung place names to Country, such as the recent change from the racist-settler-named Jim Crow Creek to Larni Barramal Yaluk, which means ‘Home of the Emu Creek’. SquattersFootnote 2 grazing sheep and cattle between the late 1830s and the gold-rush population boom of the 1850s perpetrated the Blood Hole and Campaspe Plains massacres. Decades of gold mining left the region so damaged that Djaara call it ‘upside down country’. A hundred years later, the peasant food traditions of the region’s Swiss Italian settlers provided the basis of increasing dining options for tourists travelling to Hepburn for the mineral waters. As hospitality grew, so did the need for farmers able to supply the tourist market.

The fertile red volcanic soils underpin the region’s long history of potato growing, but over the past two decades that sector has been in steady decline, as the region’s major processor, global food giant McCain Foods, has steadily dropped local farmers in favour of cheap imports. The decline in contract potato growing, as well as dairy due to the consolidation of that industry, has been inverse to the steady growth in small-scale farming—pastured pigs, poultry, and cattle, organic and heritage-variety vegetables, cut flowers, and an artisanal wine sector. The shift has seen a major break from the entrenched system of commodity markets, as most new smallholders sell directly to eaters in the local community and into Melbourne, a city of five million people just 100 km away.

Pastured pig farmers are visible and vocal leaders of the local small-scale agriculture movement, with eight establishing on less than 40 hectares each in the past decade. My position in this piece is with them, raising Large Black pigs and Speckleline and Dairy Short Horn cattle here on djandak since 2011 with my husband Stuart. When we arrived, we did not know of the global food sovereignty and agroecology movements, but fresh from a decade as an urban vegetarian concerned about the treatment of animals in industrial livestock production, I wanted to contribute to the then emerging small-scale farming movement and show that it was possible to grow pigs on pasture while making an honest livelihood. The custodial ethic for animals that we brought with us has steadily deepened in parallel with our knowledge to include careful attention to the microbial life of soils, and biodiversity of productive and non-productive plants and animals.

The regional centre of the shire is Daylesford, a town of 2,741 people according to the 2021 census. Daylesford hosted a pig abattoir for several decades just three kilometres east of town, which closed in the face of competition and consolidation of processing facilities in 2001. The closest abattoirs now are Diamond Valley (the largest pig abattoir in Australia, owned by JBS since 2022), an hour away on the edge of Melbourne, and Hardwicks (a large red meat facility bought from the Hardwick family by multinational Kilcoy in 2021), 40 min east of Daylesford. While there are two high street butchers in Daylesford, neither provide contract butchery for small-scale producers who sell directly, leading us to decide in 2013 to crowdfund and build a butcher’s shop and commercial kitchen from refrigerated shipping containers on the farm. With a lived appreciation of the intrinsic nature of processing infrastructure, we have operated as an informal food hub for the local livestock farmers for a decade. Contract butchery is offered at cost or as a labour barter, as our degrowth politics acknowledge the sufficiency of our farming income and reject the system that would accumulate a surplus from processing with and for others. I am the head butcher on the farm, while Stuart is chief farmer, and djandak is the boss– we ask the Land’s priorities first at each Monday morning beacon meeting.

We have long been concerned about the loss of regional abattoirs and not entirely satisfied with the animal welfare compromises made to transport our pigs and cattle up to an hour away to industrial facilities, especially as Diamond Valley uses CO2 stunning, an aversive gas which causes suffering for up to 20 s before animals are rendered unconscious. In 2017, with an informal group of other small-scale livestock farmers, we started investigating options to build a small-scale abattoir in the region. We received support from Southern Cross University’s Farm Co-operatives and Collaborations Pilot Program, which funded ‘expert advice’ from Deloitte on how best to structure the governance of our proposed meat collective. In truth, the research offered no further insights than our group had garnered around the benefits and challenges of cooperatives and companies limited by guarantee. With the help of a small scholarship granted by the Victorian state government, Stuart and I then went on a research tour of eight small-scale abattoirs in the United States in July 2017. Facing difficulties in mobilising the other busy smallholders to do the work needed to identify a viable site and secure funding for construction, a farm to run, and a schedule full of food sovereignty advocacy, progress on the regional abattoir project stalled, though our research continued.

Case study: pigs only build houses in fairy tales

While the abattoir research was underway, between 2015 and 2018 AFSA was involved in an onerous process for substantive legal reform of land use planning for pastured pigs and poultry in Victoria. The catalyst for a campaign (the crisis) was a threat to Happy Valley Free Range, a small-scale pastured pig farm in the Yarra Ranges, a peri-urban shire just outside of Melbourne (Jonas 2017). A complaint from a neighbour triggered a process to investigate the farm’s legal status, as the shire is in a Green Wedge Zone, with prohibitions on ‘intensive livestock production’. Historically, the definition for intensive livestock had only been applied to Confined Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), not to pastured systems generally considered to be extensive (animals grazing on pasture). However, on examination of the Victorian Planning Provisions (VPPs), the case was made that the pastured pig farm fit the definition of ‘intensive’ because pastured pig farms ‘import most food from outside the enclosures’. While the classification of ‘intensive’ was counter-intuitive to most people, it set a new precedent that required pastured pig and poultry farmers to obtain a permit to farm like their actually-intensive industrial piggery counterparts. In the case of Happy Valley, no permit could be issued due to the zoning, and the farmer was forced to sell.

AFSA national committee members saw the case of Happy Valley in the media, and we went to meet with the farmer and determine how we might help. The committee consists of a mix of farmers and allies, reflecting the organisation’s membership, and after our visit, we unanimously agreed to help Happy Valley and advocate for reform to protect other smallholders from what we deemed regulatory overreach. By this time in our own farming life, we had already encountered several legislative barriers around food safety when we built the butcher’s shop, including punitive behaviour from the meat safety regulator, and I had been writing a blog series entitled ‘The Regulation Diaries’ recounting these experiences. This tactic, along with lobbying the minister in my role with AFSA, had accomplished a review of the regulator that delivered 25 recommendations for improvement. The committee agreed that an instalment to the Regulation Diaries about the need for planning reforms was a good start, and we planned a campaign that outlined how we would use the Fourth and Fifth Estates (traditional and social media) to influence government.

AFSA took the struggle to the court of public opinion, launching a campaign to hold the government accountable and expose the undue influence wielded by peak industrial agriculture bodies such as Australia Pork Limited (APL). A formal petition was circulated around farmers’ markets with the help of our external allies in the Victorian Farmers’ Market Association (VFMA) and delivered to the Parliament demanding that small-scale pastured pig and poultry farms be identified as low-risk extensive grazing systems and distinguished from their intensive shed-raised counterparts. A social media campaign showed contrasting images with captions saying ‘this is intensive’ and ‘this is not intensive’ (see Fig. 1), a ‘mobilising discourse’. In our shire, our Council passed a motion of support for AFSA’s position that pastured pigs and poultry should be treated as extensive in the planning scheme (See Fig. 1).

The Minister for Agriculture responded, and Ag Vic (the state agriculture department) subsequently engaged with AFSA in extensive consultation, to the point that we collaborated closely on the development in 2018 of what are called the Low-Density Mobile Outdoor (LDMO) guidelines for pigs and poultry. The LDMO guidelines significantly reduced the bureaucratic burden on small-scale pig and poultry developments, in acknowledgement of the much lower risk small-scale pasture-based systems pose to environment and amenity. While in the midst of a highly public campaign in Victoria (ABC 2017; Hunt 2017; CERES 2018; Weekly Times 2018), AFSA also made submissions to a similar planning review in the neighbouring state of New South Wales, where outcomes were ultimately even better, as small-scale pastured pig and poultry farms (with less than 20 sows or 1000 poultry) are now legally exempt from permit requirements.

Case study: we don’t need another website

As a result of AFSA’s close work with Ag Vic on the planning reforms, then Minister for Agriculture Jaala Pulford announced AUD$2 million in grants for ‘artisanal agriculture’Footnote 3, quietly congratulating AFSA for putting small-scale producers on the government’s agenda (personal communication, 2018). The increasing visibility of the artisanal ag sector– especially in Hepburn Shire, where we farm– led to a process commencing in 2018 for a ‘Hub for Premium Produce’ in partnership with the state government, the major funder. Many of the farmers involved in the earlier discussions regarding a cooperative regional abattoir were consulted by the shire, including me both in my role as a local farmer and as the president of AFSA. During consultation, farmers repeatedly called for funding and support to build local processing infrastructure as a key priority (abattoirs, boning rooms, commercial kitchens, grain mills, and dairy processing were all raised). In response, government officials in the meetings frequently responded as to whether an online hub would be more achievable. Ultimately, it was reported that the six key barriers to artisanal ag were (Hepburn Shire Council 2023: 9):

-

Inappropriate business services.

-

Limited access to shared markets (distribution channels).

-

Limited access to shared infrastructure (processing plant and other equipment).

-

Scale-inappropriate food regulations.

-

Limited access to grants and finance to scale up.

-

Competing land use pressures, cost of land including planning regulations are a barrier to entry.

With producers advocating a physical food hub with processing facilities, and government advocating an online hub, a compromise was made to fund a dedicated staff member to run a pilot Artisan Agriculture project guided by a Project Advisory Group (PAG) made up of local farmers and state and local public servants. Some of us requested that farmers participate in developing the position description, however, we were ignored. Critically, unlike in the engagement with the state government over the planning reforms, ‘we’ were not speaking as AFSA, a national representative body for smallholders, but rather as a random selection of local atomised farmers. Some of the other farmers involved in the PAG were not AFSA members, and not all openly aligned with the more radical politics of the organisation. The project received funding of AUD$570,000 over three years from the state government and AUD$90,000 in cash and in-kind support from council, and commenced in February 2020. At the end of the three-year project:

-

no new infrastructure was built;

-

no regulatory reforms were achieved;

-

18 producers received up to AUD$2000 in small grants; and.

-

the community was no better collectivised.

Instead, the council built a website, and named it the Central Highlands Growers Collective without consulting the farmer members of the PAG. As Wagenaar and Prainsack (2021: 13) point out, ‘policy makers are often attracted to the proximate effect instead of the distant cause.’ Cavaye (2004: 13) further observes that ‘in some cases, government agency contact may hinder community empowerment and development. There is substantial evidence of community groups being coopted or community capability being suppressed by government (Piven and Cloward, 1979; Moynihan, 1969; McCloskey, 1996)’.

Over three years, various PAG farmer members attempted to influence the project to deliver transformative outcomes. There were two particular interventions intended to call the government to account– one individual and one collective. Unlike in the state planning campaign, both were internal interventions rather than public: my resignation letter at the end of the first year of the project (March 2021); and a letter of concern signed by eight of the nine PAG producer members in October 2021. In my resignation letter, I reminded the council officers and councillors that farmers have been asking for infrastructure, a need identified by the FAO for at least a decade (Kay 2016). I further recommended a process to improve the transparency and processes for governance, including participatory budgeting for the remaining budget.

In October 2021, although I was no longer a member, we convened all of the other farmer members of the PAG at our farm to discuss concerns about a fresh push from council officers for an online hub instead of a physical food hub. The farmers collectively drafted a letter expressing those concerns and outlining a clear proposal for a food hub. Among other observations, the letter noted:

While we believe an online marketplace will be of value to producers, it will not resolve the underlying barriers outlined in ‘Problem 1’ around processing (Barrier 2.1.3) and distribution (Barrier 2.1.2). Nor does it provide solutions to Problems 2 or 3 regarding scale-inappropriate regulations, access to grants, or competing land use pressures and planning restrictions.

The PAG offered concrete proposals regarding site selection, and it scoped the needs of the project to determine capital costs and a viable business model, along with the development of a robust governance model. It acknowledged the importance of relevant planning provisions, distribution logistics, and the need for an ‘online presence for the hub that is not an expensive showpiece, but rather a well-functioning website reflecting the genuine efforts and collaborations extant and emerging in our region.’ According to an officer working within the Artisan Ag project in council, the PAG’s intervention (personal communication, 2023):

was pretty much dismissed… It wasn’t really read… there was no discussion about it, it was just like, ‘oh, look what they’ve done!’ it went to [a manager] and it was just like, ‘people causing trouble’.

The group was still interacting with council as individual PAG members rather than as members of a democratic association like AFSA. Some members of the PAG ‘link politics with unbecoming, nefarious, and other negative actions’ (Kerkvliet 2009: 228), and so remained reluctant to speak as a collective, though they had been prepared to sign the letter of concern as individuals.

In February and March 2022, with less than a year left of the project funding, two workshops were convened, facilitated by food system activators Open Food Network (OFN). The OFN summary report released in April 2022 states:

The objective of these workshops was to define a vision for the Hepburn Food Hub, and to determine and gather consensus on necessary infrastructure, possible locations and some clear actionable next steps to drive this project and idea forward.

A decision to form a steering committee for a Hepburn Food Hub came of the Artisan Ag workshop with OFN, which recommended that Council ‘enable the community to lead and deliver this project’. Most members of the PAG and several people from the broader community came together to apply for a new state government grant opportunity that was announced to support the establishment and development of physical food hubs across Victoria. The steering committee collaboratively drafted terms of reference, and asked for a commitment of a small amount of seed funding ($60,000) from the remaining funds of the Artisan Ag project and for a letter of support from Council. The result was no seed funding and a letter which claimed the group had ‘formed separately’ to the Artisan Ag project. The Hepburn Food Hub proposal did not receive funding from the new state government initiative.

The final Artisanal Agriculture pilot project ‘Unlocking the Gate’ report was published without fanfare by Council in May 2023. It claims:

The pilot Artisan Agriculture Project has been successful in delivering a more capable, connected and collaborative artisan agriculture sector across the Central Highlands region of Victoria.

After acknowledging OFN’s recommendation for the community to lead and build a physical food hub, the document reports that ‘a consultant was appointed to develop a roadmap for a business plan to develop a physical food hub’. It then reports that ‘To move the food hub concept forward, further work and government funding is required beyond the Artisan Agriculture Project’. In February 2023, a report was published on the council website entitled the ‘Artisan Agriculture Physical Food Hub Business Plan Roadmap’ written by consultants who had not been involved in the three-year project, and who did not work with the PAG to draft the roadmap. The report states:

Our brief was to craft a road map and pathway that brings together the knowledge, skills and information required to create a thriving and sustainable artisan physical food hub.

This document has been designed to guide a founding group to consolidate their current thinking, workshop key questions, and pull the results into a road map that will support them to take an idea through to being investment ready and implementing their operational plan.

In late 2022, a static website linking to farms’ and farmers’ market websites was launched, the ‘Central Highland Growers Collective’, purported to connect eaters to farmers to buy produce, share knowledge, facilitate equipment and tool sharing, and connect farmers with jobseekers looking for seasonal employment. In late 2023, due to lack of funding, the website was handed over to the Ballarat Chamber of Commerce without further consultation with local growers, and the name changed to Central Highlands Growers and Producers Hub. At the close of the project, $70,000 of unspent funding was handed back to the state government.

Following Mier et al. (2018) theory of the eight key drivers for taking agroecology to scale, I present a table that summarises the successes and failures of the 2018 Victorian planning reform campaign and the Artisan Ag pilot project in Hepburn Shire case studies.

Planning reforms 2016–18 | Artisan Ag 2020–23 | |

|---|---|---|

Crisis | Pastured pig farm loses at VCAT, pressure on others to follow industrial permit process | Absent– came out of government-led process |

Social organisation, process | Led by AFSA– ‘advocacy politics’ solid campaign strategy | Absent– ‘everyday politics’ of atomised farmers No strategy until too late in the project |

Effective agroecological practices | Soil health Animal health Synergy Recycling Co-creation of knowledge Participation Land and natural resource governance Biodiversity | Mix of regen ag & agroecology, ill defined, no consensus (or attempt to build it) In particular, lack of social movement of agroecology |

Mobilising discourse | ‘This is intensive, this is not intensive’ | Absent– even ‘artisan ag’ was contested by those aligned with agroecology |

Constructivist pedagogy | Built knowledge together to propose guidelines | Absent, top down approach, paying ‘expert’ consultants |

External allies | Regrarians (nutrient calculations) Ag Vic (over time) Council (motion to support) VFMA, OFN, etc. | Absent until OFN participation, but lack of social organisation & constructivist pedagogy doomed it by then |

Favourable markets | Farmers’ markets, CSA | CSA for some, others farmers’ markets, and some wholesaling |

Favourable policies | Achieved | Several present but not adhered to by Council (e.g. transparency, community engagement) |

How to mobilise the state for the intrinsic infrastructure of agroecology

The failure of the Artisanal Agriculture pilot project in Hepburn Shire to produce tangible solutions to clearly identified barriers is not unique. In fact, it is so common in my and other smallholders’ lives that it has led me to a PhD that is worrying deeply at ‘the problem of the state’ in achieving an agroeocological transition. Today, while the enabling policies for agroecology are slowly being developed, such as for scaled land use planning and food safety legislation, local and state government authorities across Australia already have enabling policy environments for community engagement and public transparency, and where democratic associations exert their civic rights, reforms can occur. The best means of developing these civic skills is through democratic associations such as AFSA (Wright 2021; Wagenaar and Prainsack 2021). However, the predominant neoliberal subjectivity of Australian farmers (Iles 2020; Jonas & Gressier, Forthcoming) often leads to an ‘everyday politics’ (Kerkvliet 2009) that makes it difficult to collectivise.

We need to move from Levitas’ (2013: 153) ‘ontological mode’ of utopian thinking, wherein we are concerned with the institutional arrangements that privilege or suppress certain capabilities. Instead, we must move to the ‘architectural mode’ and design alternative institutional and social arrangements to bring about human flourishing, which underscores the need for a truly Ecological Society: ‘a rich associational civil society, problem-driven practical deliberation, and the creation of intermediary structures that mediate between state agencies and associational civic life’ (Wagenaar and Prainsack 2021: 146). Wagenaar and Prainsack (2021: 146) assert the utopian role of civil society, collectivised, should be one wherein:

-

1.

Associations are incubators for creative solutions;

-

2.

They teach citizens the skills that are needed to solve problems together;

-

3.

One of the skills central to associations is deliberation;

-

4.

Schools of democracy are established where citizens learn about the values that sustain democracy, and about collective problems, and the information and knowledge needed to understand and solve them– associations are a form of developmental democracy; and.

-

5.

The monitoring of powerful elites is routine.

In addition to the contrasting levels of social organisation between the case studies, the other critical difference in civil society’s tactics is public debate. In the Victorian planning reforms campaign, AFSA worked collectively to monitor powerful elites, and then used its collective voice in mobilising discourse in the Fourth and Fifth Estates to call the state to account. It did not take long to move from a publicly adversarial campaign to working closely with Ag Vic to achieve reforms that enable the agroecological transition. Years of this work with the Victorian Government has built a ‘thick legitimacy’ (Montenegro & Iles 2016) that now sees AFSA consulted and invited to participate in a multitude of government processes of concern to its members, including recent discussions on how the government can enable a flourishing of micro-abattoirs.

In the case of the Artisan Ag project, members of the PAG were (a) not politically collectivised, and (b) kept the critiques internal to the process rather than publicising Council’s repeated failures to adhere to its own public transparency, community engagement, and governance policies. I believe this was a category mistake by civil society actors, including myself. There is not space in this paper to fully analyse why the mistake was made, especially as my gaze is hardly distanced from the everyday politics amongst the farmers and public servants in a small rural community. However, I would hazard comment that it relates to the conundrum of ‘good manners’ in a small community, and fear of retribution from council officers in other interdependencies between farmers and Council’s regulation of the planning scheme, in particular. Ultimately, keeping complaints internal and without strong social organisation failed to hold the state to account, resulting in poor community outcomes and a great waste of public funds. A task for our local community is to help more actors see that ‘society, any society, needs to devise ways to allocate resources. Those ways and the process of determining them are political’ (Kerkvliet 2009: 228). To quote human geographer of environmental justice and rural well-being Jesse Ribot (2014: 698) at length:

If we, as analysts or activists, insist on requiring that all interventions enable democracy, and we insist this demand be enforced, we may help force the hand of practice… I do not want to act or be in a world that does not try. Democracy is an ongoing struggle. It is not a state to be arrived at. It will come and go in degrees. Trying is the struggle that produces emancipatory moments—however ephemeral they may be. The fleeting joy and creativity of freedom seem worth it.

The struggles will not be won behind closed doors, which is where oligarchies are formed. Only by placing the battles in the public eye, inviting civil society to participate in the debates about how to build the intrinsic infrastructure of agroecology, and equipping them with the civic tools for the debates will we be able to build an agroecological state. Iles (2020: 6) reflects AFSA’s experience in its decade of advocacy, saying, ‘Without overstating their potential, movements may generate enough energy, embodied knowledge, and political power to put real pressure on entrenched regimes to start unwinding.’

Conclusion

The loss of access to abattoirs is accelerating in Australia, and every farmer who contacts AFSA concerned about their livelihoods underscores the intrinsic nature of this critical infrastructure to the lives and deaths of the human and more-than-human members of their agro-ecosystems. The new peasantry are working to mend the metabolic rift with agroecology from the practical to the political, and for livestock farmers, abattoirs are essential to transforming animal lives into nourishing food while maintaining fertility within the ecological footprint of their farms. Smallholders don’t need capital, we need patrimony to ensure resilience and socio-ecological reproduction in relation with the lands in our care. And the development of these projects necessarily involves the state, with its role in land use planning and protections and the assurance of safe food outcomes, and it may or may not involve state funding, but if it does, AOFGs have work to do to ensure community projects are community controlled.

A key outcome of this insider-activist research is a project by AFSA to complement current work to update the Peoples’ Food Plan, our founding document, which includes peoples’, communities’, and collectives’ actions, as well as the peoples’ recommendations for action by educational institutions and all levels of government. Recommendations for government work from the granular level of specific pieces of legislation to amend, such as those developed in the 2018 Victorian planning reform campaign, to statements of principle, such as asserting the 13 principles for agroecology (Gliessman 2007; HLPE 2019). In addition to reference to the enabling policy frameworks that already exist (e.g. public transparency, community engagement, and governance policies enshrined in local government acts), AFSA plans in 2024 to design guides for local democratic associations to participate collectively in local decision-making processes that affect them directly and that help build a better world. In addition to making enabling policies more visible to local communities, AFSA will also provide guidance on public campaigns to monitor the state.

An outcome closer to home is the way this research has informed our progress towards an on-farm micro-abattoir. We are in an administrative battle with owners of lifestyle properties in the Farming Zone– weekenders worried about their property values– over whether we will be able to build and operate a facility that will have capacity to slaughter up to 30 pigs or six cattle once a week. Based on what we know now that we did not know in 2017, we are leveraging the crisis of concentrated ownership of infrastructure to work with the state government to achieve favourable policies for our project, and all those we hope will come after ours. We work with the government as collective actors (Wright 2021) through AFSA, demonstrating effective agroecological practices including the ways the development builds soil and animal health through recycling and synergy, while ensuring connectivity and fairness, building economic diversification, and relying on co-creation of knowledge. We have allies in Ag Vic, the Council and the Fourth Estate, not to mention in the broader public, because our ‘favourable markets’ (Mieret al. 2018) consist of the solidarity economy of community-supported agriculture (CSA), and because we practice radical transparency at every step of the way.

It is time for movements in the neoliberal settler colonial states such as Australia to shift our epistemologies away from the concept of a ‘middle infrastructure’ posited as a value chain simply in need of a transfer of ownership, to the ways an intrinsic infrastructure feeds, mends, and stabilises the metabolism of agroecology. To do this takes a participatory democratic approach, a rejection of the idea (Kerkvliet 2009: 240):

that politics is something far removed from our own lives, something only politicians and political activists do– people who are distant from and usually unknown to us. It obscures the political significance and ramifications of things we, individually and collectively, regularly do that affects who gets what, when, and how.

Neoliberalism will take all of us to overturn– people on the ground doing everyday politics, and collectivising through democratic associations doing advocacy politics to influence the state to achieve favourable policies for the agroecological transition.

My comrade scholar-activist Chappell (2018: 4) cited the late Brazilian sociologist Herbert “Betinho” de Souza in his groundbreaking analysis of how the city of Belo Horizonte ‘began to end hunger’ through strategic activities at every level from farmers and hunger activists to targeted enabling policy and subsidies, in which Betinho asserted, ‘I’m not some stupid optimist […] I’m an active optimist.’ I have carried this statement with me for years as a mantra for us all to be active in our own optimism, knowing that our actions must be informed and collective to be effective. As we say in la Vía Campesina, an empowered and collectivised peasantry can ‘feed our peoples and build the movement to change the world!’

Notes

We prefer agroecology ‘beacon’ to ‘lighthouse’, because, unlike in Spanish, where ‘faro’ is used for both, in English they have quite different meanings. Lighthouses were developed to keep trade moving through the night in the endless pursuit of profit, and are lonely places that tell travellers to stay away. Beacons, on the other hand, are lit by communities to show the way, which better reflects the growing movement of agroecology beacons around the world, where smallholders are radically transforming the food system from the ground up.

Many of the earliest settler-invaders to graze livestock in Australia illegally occupied Crown land (Crown land is illegally occupied Aboriginal Land held by the state). Successive colonial authorities recognized those called ‘squatters’ as legal owners of the land they grazed, and many went on to become wealthy pastoralists with vast landholdings, collectively referred to as the ‘squattocracy’, a play on ‘aristocracy’. (Squattocracy, State Library of NSW. 12 Feb 2016).

AFSA contests the label of ‘artisanal ag’ as it is typically used to signify a luxury or niche market segment, and our movement aims for agroecology to be normal and just, not niche, but we have had limited success convincing governments to use the language of agroecology. A notable exception is the Mornington Peninsula Food Economy and Agroecology Strategy, which AFSA was involved in developing and invited to provide the keynote presentation at its launch.

References

ABARES. 2021. Snapshot of australian agriculture 2021. Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences.

ABC. 2017. AFSA President Tammi Jonas Rejects Changes, ABC Country Hour, https://afsa.org.au/president-tammi-jonas-rejects-changes-proposed-new-planning-provisions-victorian-government-abcs-country-hour/ [accessed 25/6/23].

ACCC. 2021. Statement of Issues: JBS– proposed acquisition of Rivalea, 16 September 2021.

Andrée, P., J. Dibden, V. Higgins, & C. Cocklin. 2010. Competitive Productivism and Australia’s Emerging ‘Alternative’ Agri-food Networks: producing for farmers’ markets in Victoria and beyond. Australian Geographer 41(3): 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2010.498038.

BBC. 2017. Brazil meat-packing giant JBS to pay record $3.2bn corruption fine, 31 May 2017. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-40109232 [accessed 25/6/23].

Berti, G. 2020. Sustainable agri-food economies: re-territorialising farming practices, markets, supply chains, and policies. Agriculture (Switzerland) 10(3): 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10030064.

Blumberg, R., H. Leitner, and K.V. Cadieux. 2020. For food space: theorizing alternative food networks beyond alterity. Journal of Political Ecology 27(1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.2458/v27i1.23026.

Butler, J., and A. Athanasiou. 2013. Dispossession: the performative in the political. Wiley.

Cavaye, J.M. 2004. Governance and Community Engagement – The Australian Experience, in Participatory Governance: Planning, Conflict Mediation and Public Decision Making in Civil Society. W.R. Lovan; M. Murray and R. Shaffer (Eds) pp. 85–102 Ashgate Publishing UK.

CERES. 2018. Big win for small farmers, https://www.ceresfairfood.org.au/chris-newsletter/regen-farming/big-win-for-small-farmers-dream-job-at-ceres-farm/ [accessed 25/6/23].

Chappell, M.J. 2018. Beginning to End Hunger: Food and the environment in Belo Horizonte, Brazil and beyond. University of California Press.

Civil Society Mechanism (CSM). 2016. Connecting Smallholders to Markets: An Analytical Guide, https://www.csm4cfs.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/English-CONNECTING-SMALLHOLDERS-TO-MARKETS.pdf [accessed 25/6/23].

De González, M., and D. Lopez-Garcia. 2021. Principles for designing agroecology-based local (territorial) agri-food systems: a critical revision. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 45(7): 1050–1082. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2021.1913690.

de Montenegro, M., and A. Iles. 2016. Toward thick legitimacy: creating a web of legitimacy for agroecology. Elementa 4: 000115.

Diamond Valley Pork (DVP). 2023. About Us. https://www.diamondvalleypork.com.au/About-Us [accessed 16/11/23].

Edwards, F. 2023. Food Resistance movements: journeying through alternative food networks. London: Palgrave.

ETC Group. 2013. Poster: Who will feed us? The industrial food chain or the peasant food webs? http://www.etcgroup.org/content/poster-who-will-feed-usindustrial-food-chain-or-peasant-food-webs. [accessed 23/12/23].

FAO. 2019. The State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture. In Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, eds. J. Bélanger and D. Pilling. http://www.fao.org/3/CA3129EN/CA3129EN.pdf.

Gibson-Graham, J.K. 2006. A Postcapitalist Politics. Minnesota University Press.

Gliessman, S.R. 2007. Agroecology: the ecology of sustainable food systems. New York, USA: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis.

Global Witness. 2022. ‘Banks and financiers back beef giant JBS to the tune of almost $1bn despite links to widespread deforestation, land grabbing and slave labour in the Amazon, with tainted beef and leather entering British and European markets’, 23 June 2022, https://www.globalwitness.org/en/press-releases/banks-and-financiers-back-beef-giant-jbs-tune-almost-1bn-despite-links-widespread-deforestation-land-grabbing-and-slave-labour-amazon-tainted-beef-and-leather-entering-british-and-european-markets/ [accessed 25/6/23].

Giraldo, O.F., and N. McCune. 2019. Can the state take agroecology to scale? Public policy experiences in agroecological territorialization from Latin America. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2019.1585402.

Giraldo, O.F., and P.M. Rosset. 2022. Emancipatory agroecologies: social and political principles. The Journal of Peasant Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2022.2120808.

Goodman, D. 2003. The quality “turn” and alternative food practices: reflections and agenda. Journal of Rural Studies 19: 1–7.

Gramsci, A. 1971. Selections from the Prison Notebooks, ed. and trans. Hoare Q, Smith Nowell. London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Hale, C. 2001. What is activist research? Social Science Research Council 2: 1–2.

Hepburn Shire Council. 2023. Artisan Agriculture Project: Unlocking the Gate, https://www.hepburn.vic.gov.au/files/assets/public/businesses/documents/artisan-agriculture-unlocking-the-gate-report.pdf [accessed 25/6/23].

HLPE. 2019. Agroecological and other innovative approaches for sustainable agriculture and food systems that enhance food security and nutrition. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security, Rome.

Holt Giménez, E. and A. Shattuck. 2011. Food Crises, Food Regimes and Food Movements: Rumblings of Reform or Tides of Transformation? The Journal of Peasant Studies 38(1): 109–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2010.538578.

Hunt, P. 2017. ‘Reforms will cut red tape for smaller free-range pig and chicken farmers’, Opinion, Weekly Times. https://www.weeklytimesnow.com.au/news/opinion/reforms-will-cut-red-tape-for-smaller-freerange-pig-and-chicken-farmers/news-story/0b60ec6cdff8210b6fee5b64f044ba3c [accessed 25/6/23].

Iles, A. 2020. Can Australia transition to an agroecological future? Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2020.1780537.

IPBES. 2019. Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. United Nations. https://ipbes.net/global-assessment.

Jonas, T. 2017. Planning for Industrial Intensive Animal Agriculture: The Regulation Diaries (7), Tammi Jonas: Food Ethics, http://www.tammijonas.com/2017/10/14/planning-for-industrial-intensive-animal-agriculture-the-regulation-diaries-7/, [accessed 25/6/23].

Jonas, T., and C. Gressier. Forthcoming. Australia’s New Peasantry: towards a politics and practice of Custodianship on Agroecological farms. The Journal of Peasant Studies

Jonas, T., and B. Trethewey. 2023. Agroecology for Structural One Health. Development. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41301-023-00385-0.

Kallio, G. 2020. A carrot isn’t a carrot isn’t a carrot: tracing value in alternative practices of food exchange. Agriculture and Human Values 37: 1095–1109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-020-10113-w.

Kay, S. 2016. Connecting smallholders to markets. Civil Society Mechanism.

Kerkvliet, B.J.T. 2009. Everyday politics in peasant societies (and ours). The Journal of Peasant Studies 36(1): 227–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150902820487.

Kirschenmann, F.L., G.W. Stevenson, F. Buttel, T.A. Lyson, and M. Duffy. 2008. Why worry about the agriculture of the middle? In Food and the mid-level farm: renewing an agriculture of the Middle, eds. T.A. Lyson, G.W. Stevenson, and R. Welsh. 3–22. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Levitas, R. 2013. Utopia as method: The imaginary reconstitution of society. Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills.

López-García, D., and M. Carrascosa-García. 2023. Agroecology-oriented farmers’ groups. A missing level in the construction of agroecology-based local agri-food systems? Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 47(7): 996–1022. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2023.2217095.

McMichael, P. 2013. Food regimes and Agrarian questions. Practical Action Publishing. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1hj553s.

McMichael, P. 2009. A food regime genealogy. The Journal of Peasant Studies 36(1): 139–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150902820354.

Meek, D. 2014. Agroecology and Radical Grassroots Movements’ Evolving Moral Economies. Environment and Society 5(1): 47–65. https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2014.050104. Accessed 30 Sep 2023.

Micarelli, G. 2021. Feeding “the commons”: Rethinking food rights through indigenous ontologies. Food, Culture & Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2021.1884402.

Mier, Y., M. Terán Giménez Cacho, O.F. Giraldo, M. Aldasoro, H. Morales, B.G. Ferguson, P. Rosset, A. Khadse, and C. Campos. 2018. Bringing agroecology to scale: key drivers and emblematic cases. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 42: 637–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2018.1443313.

Mignolo W.D., and C.E. Walsh. 2018. On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis. Durham: Duke University Press.

Morley, A.S., S.L. Morgan, and Morgan, K.J. 2008. Food hubs: The ‘missing middle’ of the local food infrastructure? Cardiff: Centre for Business Relationships, Accountability, Sustainability and Society (BRASS), Cardiff University.

Muir, C. 2014. The broken Promise of Agricultural Progress: an environmental history. Abingdon: Routledge.

Pimbert, M.P. 2018. Democratizing Knowledge and Ways of Knowing for Food Sovereignty, Agroecology and Biocultural Diversity. In Food Sovereignty, Agroecology and Biocultural Diversity: Constructing and Contesting Knowledge, ed Michel P. Pimbert, 259–324. London: Routledge.

Pimbert, M. 2023. Agroecology, food sovereignty and the absolute need for economic democracy, Colin Tudge’s Great Re-Think. https://www.colintudge.com/agroecology-food-sovereignty-and-the-absolute-need-for-economic-democracy/. Accessed 18 Nov 2023.

Reckinger, R. 2022. Values-based territorial food networks: qualifying sustainable and ethical transitions of alternative food networks. Regions & Cohesion 12(3): 78–109. https://doi.org/10.3167/reco.2022.120305.

Renting, H., T.K. Marsden, and J. Banks. 2003. Understanding Alternative Food Networks: Exploring the Role of Short Food Supply Chains in Rural Development. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2003, 35, 393–411.

Renting, H., M. Schermer, and A. Rossi. 2012. Building food democracy: Exploring civic food networks and newly emerging forms of food citizenship. The International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food. Paris, France, 19(3): 289–307. https://doi.org/10.48416/ijsaf.v19i3.206.

Ribot, J. 2014. Cause and response: Vulnerability and climate in the anthropocene. The Journal of Peasant Studies 41:5 667–705. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.894911.

Richards, C., U. Kjærnes, and J. Vik. 2016. Food Security in Welfare Capitalism: Comparing Social Entitlements to Food in Australia and Norway. Journal of Rural Studies 43: 61–70. DOI: 0.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.11.010.

Rosol, M. 2020. On the significance of alternative economic practices: Reconceptualizing alterity in alternative food networks. Economic Geography 96:1 52–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2019.1701430.

Rosset, Peter, and Miguel Altieri. 2017. Agroecology: Science and Politics. Practical Action Publishing.

Rossi, A. 2017. Beyond Food Provisioning: The Transformative Potential of Grassroots Innovation around Food. Agriculture 2017, 7, 6.

Rossi, A., S. Bui, and T. Marsden. 2019. Redefining power relations in agrifood systems, Journal of Rural Studies, Vol. 68, 2019, Pp. 147–158, ISSN 0743– 0167, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.01.002.

Scott, J.C. 1998. Seeing like a state: how certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Durham: Yale University Press.

Shattuck, A., C.M. Schiavoni and Z. VanGelder. 2015. Translating the politics of food sovereignty: Digging into contradictions. Uncovering New Dimensions, Globalizations 12(4): 421–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2015.1041243.

Smith, K. 2023. Scaling up civic food utopias in Australia: The challenges of justice and representation. Sociologia Ruralis 63: 140–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12368.

Stahlbrand, L. 2018. Can values-based food chains advance local and sustainable food systems? Evidence from Case Studies of University Press. Procurement in Canada and the UK. The International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food. Paris, France, 24(1): 77–95. https://doi.org/10.48416/ijsaf.v24i1.117.

Stewart, A. 2009. Windows onto other worlds: the role of imagination in outdoor education. Paper presented at Outdoor education research and theory: critical reflections, new directions. The Fourth International outdoor Education Research Conference, La Trobe University, Beechworth. Victoria, Australia, Accessed 15–18 April 2009.

US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). 2020. SEC Charges Brazilian Meat Producers With FCPA Violations, 14 Oct 2020, https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2020-254 [accessed 25/6/23].

van der Ploeg, J.D. 2008. The New peasantries. Struggles for autonomy and sustainability in an era of Empire and Globalisation. London: Earthscan.

van der Ploeg, J.D., Jingzhong, Y. and S. Schneider. 2012. Rural development through the construction of new, nested, markets: Comparative perspectives from China, Brazil and the European Union. Journal of Peasant Studies 39(1): 133–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2011.652619.

van der Ploeg, J.D., J. Ye, and S. Schneider. 2022. Reading markets politically: on the transformativity and relevance of peasant markets. The Journal of Peasant Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2021.2020258.

Wagenaar, H., and B. Prainsack. 2021. The pandemic within: Policy making for a Better World. Policy Press: Bristol University.

Wallace, R., A. Liebman, D. Weisberger, T. Jonas, L. Bergmann, R. Kock, and R.G. Wallace. 2021. Industrial Agricultural Environments. In Routledge Handbook of Biosecurity and Invasive Species, 194–214, edited by K. Barker and R.A. Francis, Abingdon: Routledge.

Watts, D.C.H., Ilbery, B., and Maye, D. 2005. Making reconnections in agro-food geography: Alternative systems of food provision. Progress in Human Geography 29(1): 22–40. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132505ph526oa.

Weekly Times. 2018. Livestock Planning Reforms: For piggeries, it’s a curly one.

Wezel, A., S. Bellon, T. Doré, C. Francis, D. Vallod, and C. David. 2009. Agroecology as a science, a movement and a practice. A review. Agronomy for sustainable development 29: 503–515.

Whatmore, S., P. Stassart, H. Renting. 2003. What’s alternative about alternative food networks? Environment and Planning A 35: 389–391.

Wilson, A.D. 2013. Beyond alternative: exploring the potential for autonomous food spaces. Antipode 45(3): 719–737.

Wittman, H. 2009. Reworking the metabolic rift: La Vía Campesina, agrarian citizenship, and food sovereignty. The Journal of Peasant Studies 36(4): 805–826. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150903353991.

Wright, E.O. 2021. How to Be an Anti-capitalist in the 21st Century. Verso: London.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note