Abstract

Many are calling for transformative food systems changes to promote population and planetary health. Yet there is a lack of research that considers whether current food policy frameworks and regulatory approaches are suited to tackle whole of food systems challenges. One such challenge is responding to the rise of ultra-processed foods (UPF) in human diets, and the related harms to population and planetary health. This paper presents a narrative review and synthesis of academic articles and international reports to critically examine whether current food policy frameworks and regulatory approaches are sufficiently equipped to drive the transformative food systems changes needed to halt the rise of UPFs, reduce consumption and minimise harm. We draw on systems science approaches to conceptualise the UPF problem as an emergent property of complex adaptive food systems shaped by capitalist values and logics. Our findings reveal that current food policy frameworks often adjust or reform isolated aspects of food systems (e.g., prices, labels, food composition), but under-emphasise the deeper paradigms, goals and structures that underlie the rise of UPFs as a systems phenomenon, and its socio-ecological implications. We propose that a ‘leverage points’ framework illuminates where to intervene in food systems to generate multi-level changes, while the theory of ecological regulation highlights how to respond to complex multi-factorial problems, like the rise of UPFs, in diverse ways that respect planetary boundaries. More research is needed to better understand the transformative potential of ecological regulation to advance food systems transformation and attenuate whole of food systems challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Today’s food systems are contributing to multiple, intersecting health and ecological crises (Development Initiatives 2021; Swinburn et al. 2019). Malnutrition in all its forms – including childhood stunting and wasting, micronutrient deficiencies, overweight and obesity, and diet-related noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) – affects billions of people, and unhealthy diets are the leading contributor to the global burden of disease (FAO et al. 2021; Murray et al. 2020; Willett et al. 2019). Global food system practices are driving biodiversity losses and greenhouse gas emissions (Benton et al. 2021; Leite et al. 2022; Tubiello et al. 2021), contributing to climate change and threatening population nutrition and food security (HLPE 2020; Myers et al. 2017). Recognising these challenges, many authoritative international bodies, including the World Health Organization (WHO), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and independent expert groups, are calling for food systems transformations to promote health and sustainability (FAO 2018; HLPE 2017; Swinburn et al. 2019; WHO and FAO 2018; Willett et al. 2019).

Governments play a vital role in the response to food systems challenges, including through developing policy, legislation and various forms of regulation to facilitate good governance and effective interventions (HLPE 2020; Willett et al. 2019). While food and nutrition policy frameworks (from hereon ‘food policy frameworks’) exist to inform policy actions (Diaz-Bonilla et al. 2020), there is a lack of research that considers whether these frameworks are equipped to drive the system-wide changes needed to address today’s food systems challenges (Lee et al. 2020). There is also insufficient scrutiny of current regulatory approaches to see if they are up to the task of food systems transformation, or preference incremental modifications and reforms that may generate some change but do not disrupt the status quo (Lawrence et al. 2015). Given the role of today’s food systems in current health and ecological crises, some propose that food policy and regulation must focus on truly transforming the orientation of food systems as a whole, rather than making incremental or reformative adjustments to minor system parameters (Lawrence et al. 2015; Parker et al. 2018; Slater et al. 2022; Webb et al. 2020).

The rise of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) in human diets is an illustrative example of a major current food systems challenge, requiring a “unified and impactful” policy response (Popkin et al. 2021, p. 462). The term ‘UPF’ is derived from the NOVA food classification system introduced in 2009 (Monteiro 2009), defined as “formulations of ingredients, mostly of exclusive industrial use, that result from a series of industrial processes (hence ‘ultra-processed’)” (Monteiro et al. 2019b). UPFs include many different food products: for example, carbonated soft drinks; confectionery; mass-produced packaged bread, pastries, biscuits and cakes; sweetened breakfast cereals; ready-to-eat shelf-stable or frozen meals; chicken and fish ‘nuggets’ and ‘sticks’; packaged ‘instant’ noodles, soups and desserts; and margarines and other spreads (Monteiro et al. 2019a). They typically contain little, if any, whole foods, and are manufactured using ingredients rarely found in kitchens, including cosmetic additives like flavourings, colourings and thickeners designed to enhance the product’s sensory properties (Monteiro et al. 2018). UPFs now dominate the food supply of high-income countries, such as the USA, Canada, the UK and Australia, and are rising rapidly in many highly-populated middle-income countries in all regions (Baker et al. 2020; Monteiro et al. 2019a; Popkin and Ng 2022).

The rise of UPFs in human diets raises serious concern for global health, given dietary exposure to UPFs associates with poor diet quality and multiple adverse health outcomes, including obesity, type-2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, depression, all-cause mortality and potentially cancer (Askari et al. 2020; Chen et al. 2020; Elizabeth et al. 2020; Lane et al. 2021; Meneguelli et al. 2020). These outcomes can be explained not only by the unbalanced nutrient profile of UPFs and the dietary displacement of minimally processed foods, but also by the novel physical and chemical properties that result from industrial processing. Proposed mechanisms include, for example, higher glycaemic load and reduced gut-brain satiety signalling linked with food matrix degradation, inflammation resulting from food additives and gut microflora dysbiosis, and endocrine disruption from chemical plasticisers used in packaging (Baker et al. 2020; Fardet and Rock 2019; Kliemann et al. 2022; Zinöcker and Lindseth 2018). Commercial supply chains provisioning UPFs also generate significant environmental harms (da Silva et al. 2021; Fardet and Rock 2020; Hadjikakou and Baker 2019; Seferidi et al. 2020). Among high-income countries, these include an estimated 36–45% of diet-related biodiversity loss, up to one-quarter of total diet-related water-use, and up to one-third of diet-related greenhouse gas emissions, land use and food waste (Anastasiou et al. 2022; Hadjikakou 2017). Such impacts are especially remarkable considering that UPFs are unsuitable for healthy diets and superfluous to human need.

The rise of UPFs in human diets reflects major transformations in food systems, which have accelerated in recent decades, although with wide variations between regions, countries and contexts (Baker et al. 2020). Agricultural industrialisation has enabled the production of cheap commodity ingredients for global supply chains, rapid urbanisation and income growth in middle-income countries has created new markets of aspirational consumers, and the globalisation of transnational food corporations – including their supply chains, marketing practices and corporate political activities – have acted as vectors for the spread of UPFs between and within countries (Baker et al. 2020; HLPE 2017; Monteiro and Cannon 2012; Moodie et al. 2021; Swinburn et al. 2019). The complex, global-scale and multi-layered nature of such ‘ultra-processed food systems’, calls for food policy frameworks and regulatory approaches that can drive the whole of food systems changes needed to halt the rise of UPFs, reduce consumption and minimise harm. At the same time, there is no single, uniform ‘global food system’, but a diversity of food systems types across regional, national and local levels, cultures and contexts, suggesting the need for adaptive and responsive policy action (Fanzo and Davis 2021).

Systems science approaches are useful in understanding the interrelated drivers of complex systems problems (Carey et al. 2015; Meadows and Wright 2009). The systems science concept of ‘leverage points’ can help identify the places to intervene in a system based on the potential impact for systems transformation (Abson et al. 2017; Fischer and Riechers 2019; Meadows 1999). Expert reports have called for innovative approaches and holistic models, such as diversified agroecological systems, to guide transitions across food systems that provide alternatives to the dominant practices, rules, institutions, structures and paradigms of industrial agriculture, and contribute to food systems transformation (HLPE 2019; IPES-Food 2016). While current food policy frameworks present various policy options related to different aspects of food systems, it is unclear whether they are up to the task of generating whole of food systems change. Some have suggested that a current influential food policy framework, the NOURISHING framework, could be expanded to include more policy actions in key areas related to food systems, such as environmental sustainability, governance mechanisms, and comprehensive food and nutrition monitoring and surveillance systems (Lee et al. 2020). However, few studies have turned to the systems science literature to consider whether current food policy frameworks are sufficiently equipped to generate truly transformative food systems change.

From a regulatory standpoint, the dominant ‘instrumental’ approach to regulation tends to use isolated regulatory tools to respond to one specific harm or risk at a time, rather than coordinated strategies to tackle cumulative harms to human and planetary health (Parker and Haines 2018). Noting the limitations of current regulatory approaches, Parker and Haines (2018) have proposed an ecological approach to regulation to address challenges that cut across many regulatory domains. Ecological regulation emphasises the need for a diverse range of interacting regulatory strategies that work together, like a natural ecosystem, to respond to multi-dimensional and interconnected problems in ways that respect planetary boundaries. While some have examined the regulatory studies literature to determine what forms of regulation may work best for public health problems (Magnusson and Reeve 2014; Voon et al. 2014), there is limited research that directly considers the regulatory approaches best suited to addressing the many factors that drive the rise of UPFs in human diets (Parker et al. 2018; Parker and Johnson 2019).

This review aims to critically examine whether current food policy frameworks and regulatory approaches are equipped to drive the transformative food systems changes needed to halt the rise, reduce consumption and minimise the harms of UPFs. This review has three objectives: first, to characterise the nature of the UPF problem by reviewing the literature that considers the rise of UPFs as a food systems phenomena; second, to review existing food policy frameworks and ascertain whether the recommended policy actions can adequately address the whole of food systems determinants of the UPF problem; and third, to examine the potential combination of systems science concepts and regulatory approaches to best inform future responses to the UPF problem.

Methods

Given the complexity of the topic and the need to draw from diverse literature sources and disciplines, we adopted a narrative review and synthesis method (Grant and Booth 2009; Green et al. 2006). This involved three steps: first, a semi-systematic search for academic and grey literature; second, analysis of included literature; and third, synthesis of the results.

Search process

In consultation with an academic librarian, we developed search strings based on the main concepts in the objectives of the review: ultra-processed foods and food systems, food policy frameworks, and systems science concepts and regulatory approaches (Table 1). We used the EBSCOHost research platform to search six selected academic databases from relevant fields (Academic Search Complete, Health Policy Reference Center, Legal Source, MEDLINE Complete, Political Science Complete, SocINDEX with Full Text). We also searched the websites of global public health nutrition bodies, such as the WHO, the FAO, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food), to obtain relevant documents. To supplement the structured searches, we hand-searched the reference lists of key articles to locate other relevant sources and conducted additional searches to consider emerging lines of enquiry.

Documents were included if published in English between 2000 and 2021 in a peer-reviewed journal or by an international organisation mandated to address nutrition, and outlined a food policy framework or regulatory approach relevant to public health nutrition at the global or national level. We limited the dates of search results to between 2000 and 2021 as initial preliminary searches revealed that most relevant publications were published from 2000 onwards. Given the broad scope of this review, we excluded documents that focused narrowly on interventions targeting specific settings, like schools, hospitals, workplaces, or individual behaviour change. To develop a feasible and relevant inclusion criteria, our search process excluded various other documents, such as sources in languages other than English, broader books on food policy or food systems, or reports from civil society organisations, social movements or global corporate organisations. This limits the scope of the analysis and conclusions presented in the review to the range of documents considered.

For the purposes of the second objective of the review, we limited our analysis to food policy frameworks that identify policy actions to address public health nutrition issues relevant to food systems and the UPF problem. Food policy frameworks were included if they presented clear policy options related to multiple policy areas at the national level, applicable to different countries and contexts. We excluded country-specific food policy frameworks, such as the FOOD-PRICE framework in the USA (Gerald J. and Dorothy R. Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University 2019), or frameworks focused on a particular policy area or issue, like the WHO framework for implementing the recommendations on the marketing of foods and non-alcoholic beverages to children (2012). We also excluded reports that contained high-level policy guidance and broad recommendations on food systems approaches, or decision-making tools to assist policymakers to implement policy actions under policy frameworks (Fanzo et al. 2020; Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition 2021).

Analysis and synthesis

Full documents were obtained from the relevant academic databases and stored electronically. Each document was reviewed by the lead author to identify and code themes relevant to the aim and three objectives of this review. We conducted an iterative process of constant comparative analysis to organise the qualitative data, uncover nuances in the literature and code sub-themes as the themes evolved. This involved developing, integrating and adding to the coded themes and sub-themes over a number of iterations of coding the documents (Corbin and Strauss 2008). Given the large number of sources included and the complexity of the topic, we did not use multiple-coders nor assess coder reliability. The results were synthesised to present a textual account of the findings that emerged from the literature and interpreted to report on key points for discussion.

Results

The included literature spans multiple disciplines and fields, including public health, food policy, systems science and regulatory studies. In the results section below, we present a synthesis of the main findings, organised by the three objectives of the review.

The whole of food systems determinants of the global rise of UPFs

In this section, which addresses the first objective of the review, we outline a whole of food systems approach to the global rise of UPFs and the nature of the policy and regulatory challenge. We consider the components and drivers of the UPF problem to understand the policy issues and determine possible places for regulation to intervene in food systems, in order to generate transformative change.

Food systems are complex adaptive systems

The broad term ‘food systems’ encapsulates the variety of food systems that exist in different regions and contexts worldwide (Fanzo and Davis 2021). The High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE) identifies three core components of food systems: ‘food supply chains’, which consist of the various actors and activities that take food from its production to consumption and disposal of waste; ‘food environments’, referring to the broader context in which people interact with the food system and make food choices; and ‘consumer behaviour’, which reflects people’s decisions about the foods they acquire, prepare and eat (HLPE 2017). The HLPE also describes a range of drivers of food systems: for example, political and economic drivers, like globalisation and trade; or demographic drivers, such as population growth and urbanisation (HLPE 2017). Combined, the components and drivers of food systems make up the ‘whole of food systems determinants’ (discussed below) of human diets, that influence nutrition and health outcomes, and impact the economy, society and the environment (FAO 2018; HLPE 2017; Ingram 2011; WHO and FAO 2018).

The components and drivers of food systems do not operate in isolation, but intersect to produce the system’s behaviours, properties and outcomes (IPES-Food, 2015). In this respect, food systems are ‘complex adaptive systems’ that are dynamic, non-linear and contain interdependent elements (Ericksen 2008; Guptill and Peine 2021; Hammond and Dubé 2012; Hill 2011; Leeuwis et al. 2021). Complex adaptive systems have common features, such as feedback loops that deliver information about the outcome of an action back to the source, and time delays in the availability of information about the state of the system relative to the rate of change. They also display ‘emergent properties’, phenomena that form in the system as a result of dynamic interactions within the system, and not just the sum of its separate parts. Such emergence may be desired or undesired, intentional or unintentional, depending on the perspectives and interests of different food systems stakeholders. Others have described various food systems phenomena as emergent, including obesity (Hammond 2009; Nobles et al. 2021; Swinburn et al. 2019), NCDs (Knai et al. 2018), dietary inequities (Sawyer et al. 2021), and broader phenomena like malnutrition, environmental harms, food insecurity and poverty (Leeuwis et al. 2021).

Food systems, are also ‘adaptive’ in that a change in one part of the system can affect other parts of the system (Hammond 2009; Hill 2011; Swinburn et al. 2019). This creates challenges for policymakers and regulators because a particular policy or regulatory measure may have broader effects that counteract the regulator’s intention, even if the outcome may be desirable from the perspective of other actors in the system, such as commercial actors (Hammond and Dubé 2012; Nobles et al. 2021). For example, policies to regulate artificial trans-fats in some countries have in part precipitated the rise of palm oils, another cheap and versatile UPF ingredient that can harm human and planetary health (Freudenberg 2021). Similarly, policy actions that seek to reduce added sugar consumption may lead to the increased use of non-nutritive sweeteners in UPFs, a substitution that on its own does little to shift the quality of the food supply or promote healthy dietary patterns (Russell et al. 2022). Food systems also intersect with other systems; for example, food standards to protect public health and safety relate to both the food system and the health system (Fanzo and Davis 2021; FAO 2018). This can mean that policy actions in other systems may have ripple effects on food systems. For example, a policy to promote more biofuel in the energy system will also impact food systems due to the need for crops, seen in the strong demand for agricultural inputs to produce biofuel that in part contributed to the global food price crisis of 2007–2008 (FAO 2009, 2018).

The global rise of UPFs as a systems phenomenon

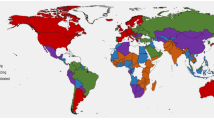

We build on the literature presented above to conceptualise the global rise of UPFs in human diets as an emergent property of today’s unhealthy and unsustainable food systems. While the complexity and diversity of food systems cannot be fully captured by general categories, experts have developed various food systems ‘typologies’ to illustrate shared characteristics at the country level, highlight patterns in outcomes and guide policy action (Fanzo et al. 2020; HLPE 2017; Nugent et al. 2015). For example, one typology demonstrates that different types of food systems associate with different levels of UPF consumption, and indicates that UPFs are most abundant in ‘industrial food systems’ in urbanised countries, yet the rate of the rise in UPF consumption is most rapid in countries that have transitioning and rural food systems (Nugent et al. 2015). There are also other terms used to differentiate food systems from dominant capitalist-industrial models, such as ‘alternative food system’ approaches, movements and practices that arise from concepts of social justice and equality and draw on local and indigenous forms of knowledge (Baker et al. 2021).

Changes in national economies and population demographics are linked to various factors that drive UPF consumption (Béné et al. 2020; Ingram 2011; Popkin 2001, 2006). As economies grow, associated rises in per capita income tend to lead to increased expenditure on food, particularly ultra-processed relative to minimally processed foods, and also on items that facilitate UPF consumption, like microwaves and refrigerators (Baker et al. 2020; HLPE 2017). Urbanisation also influences UPF consumption, as it increases access to major supermarket chains and exposure to mass media channels promoting UPF products (Baker and Friel 2016). Lifestyle and employment changes in urbanised societies, such as the shift to dual-worker households, also enable UPF manufacturers and retailers to capitalise on the convenience of UPFs that ease the time and skills demands of sourcing food and preparing meals (Béné et al. 2020). These factors can also displace freshly prepared meals and traditional foods in the diet and undermine food cultures (Juul and Hemmingsson 2015; Monteiro et al. 2011; Moubarac et al. 2014; PAHO 2015).

The global integration of food supply chains further supports the expansion of UPF markets (Baker et al. 2020; Popkin 2001, 2006; Qaim 2017). Dominant industrial productivist agricultural policies and practices facilitate increased and efficient production on a large-scale for maximum profit (Gordon et al. 2022; Parker and Johnson 2019). For example, food production policies such as agricultural subsidies and export measures can incentivise the mass, often surplus, production of commodity ingredients used in UPF manufacturing, like maize, soy and wheat, at low cost (IPES-Food, 2016; Schiavo et al. 2021; Swinburn et al. 2019). These commodity crops comprise the basic inputs for the production of industrial ingredients, such as high fructose corn syrup or soy protein isolate, predominantly used to manufacture an array of UPF products (Béné et al. 2020; Lock et al. 2009). Global food distribution networks are ideally suited to facilitate the transport of non-perishable food products, such as UPFs, over vast distances (Monteiro et al. 2013, 2019a; Moodie et al. 2021). Food retailers, particularly transnational grocery chains and regional supermarket oligopolies, also influence UPF sales and consumption, in part due to marketing techniques such as price discounts, promotions and product placement in prominent locations, like the end of the aisle or near the checkout, that suit shelf-stable and branded UPF items (Baker et al. 2020; Hawkes 2008; Machado et al. 2017).

Political and economic forces also drive the rise of UPFs. Trade and investment liberalisation has supported the global expansion of transnational UPF corporations into new markets, mainly through the acquisition of domestic competitors and the establishment of new production facilities and distribution networks (Baker et al. 2014, 2020; Hawkes 2005). Large transnational UPF corporations hold substantial material power in the form of assets and monetary resources, which can be used to support corporate political activities to delay or defeat proposed regulations that compromise their commercial interests (Baker et al. 2018; Clapp and Scrinis 2017; Moodie et al. 2013; Swinburn and Wood 2013; Wood et al. 2021). This includes, for example, lobbying politicians, establishing front groups, making political donations, self-regulation to avert government intervention, and public relations campaigns that present the UPF industry as ‘part of the solution’ (IPES-Food 2017; Lacy-Nichols and Williams 2021; Lauber et al. 2020; Mialon et al. 2020a; Mialon et al. 2020b).

The rise of UPFs is also linked to the rising power of financial actors within food systems, and an increasingly liberal global financial regime that features a rapid increase in marketised securities and greater monetary exchange freedoms (Clapp 2019; Hawkes 2010). This ‘financialisation’ provides UPF corporations with greater access to capital for ongoing expansion, helps to offset risks associated with sourcing large volumes of commodity ingredients on volatile global markets, and encourages more aggressive modes of profit-seeking to generate shareholder returns (Baker et al. 2020; Clapp 2019). The rising power of transnational corporations in a globalised economy can also feed the UPF problem, when governments provide tax or regulatory concessions to corporations in response to the implied or real threat of relocating jobs and investment (Baker et al. 2014). Similarly, trade liberalisation under rules governing international trade, investment and property rights can limit the capacity or desire of governments to regulate UPF corporations due to fear of a costly trade dispute or formal sanctions, sometimes called ‘regulatory chill’ (Friel et al. 2020; Hawkes 2010; Reeve and Gostin 2019).

Current nutrition policies and regulations reflect the material and ideological systems that permeate broader society. Global industrialised food systems are shaped by prevailing neo-liberal capitalist systems that organise political and economic activity in pursuit of capital accumulation and prioritise economic growth, market competition and individual responsibility (Baker et al. 2021; Lencucha and Thow 2019; Rose 2021; Schram and Goldman 2020). This dominant ideology supports voluntary industry self-regulation, such as food industry pledges on responsible marketing to children, and influences political preferences for market-oriented and multi-stakeholder hybrid governance approaches, including public-private partnerships (Cullerton et al. 2016; Lawrence et al. 2019; Russell et al. 2020; Shill et al. 2012). The presence of the UPF industry in food policy and governance often leads to an emphasis on nutrient-based responses, like reformulation, that diverts attention from the commercial determinants of unhealthy diets, such as UPF availability and intensive marketing (Clapp and Scrinis 2017; Ngqangashe et al. 2021a). Instead, many national nutrition policy actions focus on providing information to influence individual lifestyle-behaviour change, like nutrition labelling and education campaigns (Capacci et al. 2012; I et al. 2020; Lee et al. 2020; Mason-D’Croz et al. 2019; Mazzocchi 2017; Mozaffarian et al. 2018; WHO 2018a).

In the last decade, more countries, particularly in Latin America, have taken steps to regulate unhealthy foods. This includes legislated front-of-pack (FOP) warning labels, restrictions on food marketing to children, and constraints on foods for sale or promoted in schools (Corvalán et al. 2013; Popkin et al. 2021; Reyes et al. 2019). There has also been an increase in national taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB), introduced in over 50 countries (Sacks et al. 2021; Thow et al. 2022). Far fewer countries have enacted comprehensive and coordinated regulations to tackle unhealthy diets (Popkin et al. 2021; Swinburn et al. 2019). A notable example is Chile’s Law of Food Labelling and Advertising, which combines mandatory FOP warning labels for packaged foods and drinks that exceed threshold nutrient amounts, restrictions on marketing these products to children, plus a ban on their sale or promotion in schools (Popkin et al. 2021; Taillie et al. 2021). However, such regulatory measures generally identify unhealthy foods based on nutrient profiling systems. Although UPFs are generally high in added sugars, sodium and unhealthy fats and usually contain relatively low levels of other nutrients, the UPF definition is not based on a food’s nutrient profile but instead focuses on the use of industrial ingredients and processes (Machado et al. 2022; Monteiro et al. 2019a; PAHO 2019; Soil Association 2020). Aside from the recognition of the UPF concept in the national dietary guidelines of several countries (Koios et al. 2022; Monteiro et al. 2019a; PAHO 2019), the UPF category is yet to attract direct or comprehensive policy attention at the country level.

A nutrient-centric approach to nutrition science influences the design of evidence synthesis methods and informs nutrition policy reference standards, such as dietary guidelines (Ridgway et al. 2019; Scrinis 2013). This reductionist approach underlies how synthesised evidence is translated into nutrition policy actions, like food labelling, and also how food standards agencies interpret their primary objective to protect public health and safety using a risk analysis framework that assesses risk primarily in terms of acute food safety concerns, rather than chronic public health nutrition outcomes or environmental sustainability (Independent Panel for the Review of Food Labelling Law and Policy 2011; Lawrence et al. 2019). The emphasis on nutrients in policy design arguably generates unintended emergent challenges for public health. It can incentivise UPF reformulation to achieve commercially desirable outcomes; for example, to attract higher ‘healthiness’ ratings under nutrient-centric schemes, meet the criteria for nutrient content claims, or fall under nutrient thresholds that trigger the application of mandatory warning labels or advertising restrictions (Sambra et al. 2020). Reductionist policy actions to ‘correct’ unhealthy foods may give UPFs a ‘health halo’ that operates to displace minimally processed foods from the diet (Dickie et al. 2018, 2020). It can also devalue traditional understandings of healthy and sustainable diets implicit in cultural practices and dietary patterns (Monteiro et al. 2015). In addition, there is a broader opportunity cost for more comprehensive and holistic policies that seek to transform entire food systems to promote human and planetary health (Russell et al. 2022).

Can existing food policy frameworks adequately respond to the rise of UPFs as a systems phenomenon?

The prior section presented the UPF problem as an emergent food systems phenomenon with multiple determinants, and anchored to neo-liberal capitalist values and logics. From a policy perspective, the nature and scope of the UPF problem suggests that transformative action to tackle the rise of UPFs will entail a wide range of interventions at many different places in food systems.

Various food policy frameworks have been developed to classify and inform nutrition policy actions (Diaz-Bonilla et al. 2020). This section, which addresses the second objective of the review, will examine three influential food policy frameworks focused on the promotion of healthy diets and relevant to the UPF problem: the NOURISHING framework, the Healthy Food Environment Policy Index (Food-EPI) and the WHO Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013–2020 (WHO Action Plan). These frameworks have been widely cited in nutrition policy analyses worldwide (Allen et al. 2018; Bakhtiari et al. 2020; Guariguata et al. 2021; I et al. 2020; Laar et al. 2020; Lee et al. 2020; Mason-D’Croz et al. 2019; Nieto et al. 2019; Vanderlee et al. 2019; Vandevijvere et al. 2019b; Yamaguchi et al. 2021). While each framework is presented and used as a distinct policy tool, they are interrelated documents and broadly consistent in content. In this section, we provide a summary of the frameworks (Table 2) and consider whether they adequately address the whole of food systems determinants of unhealthy diets in today’s food systems, illustrated by the UPF problem.

Our review of these frameworks identified some key themes. First, such frameworks tend to propose that a ‘menu’ or ‘package’ of listed policy actions is the foundation for a policy response to unhealthy diets. This approach is useful to delineate tangible policy areas and actions, however it risks discounting the intangible and dynamic qualities of food systems. By their nature, complex adaptive systems cannot be fully understood as the sum of their parts because they feature interdependent components and adaptive responses (Holmes et al. 2012). A list of policy options may also under-emphasise the importance of interactions among policy actions. For example, while NOURISHING recommends multiple actions across policy domains, it does not specifically contemplate the ways that policy actions may interact to generate synergistic effects (Hawkes et al. 2013). Another example is the concept of cost-effective ‘best buy’ interventions in the WHO Action Plan (Allen et al. 2018; WHO 2017). While it is strategic to unite health impact and economic benefits, this approach may not be sufficiently sensitive to the broader impacts of a particular intervention on population nutrition and health outcomes, or society and the environment.

Second, while these food policy frameworks offer substantial guidance on policy actions to change isolated parts of food systems, they do not fully consider the deeper drivers that shape how the system works. Food policy frameworks tend to adopt the current reductionist approach to nutrition science and focus on exposures to risk nutrients, like added sugars, sodium and unhealthy fats. For instance, listed policy actions related to food composition generally focus on nutrient targets or reformulation strategies (Hawkes et al. 2013; Swinburn et al. 2013; WHO 2017). The emphasis on examining the presence or absence of amounts of nutrients in foods can detract from the burdens that reformulated UPFs still place on human health and the planet (Askari et al. 2020; Chen et al. 2020; Elizabeth et al. 2020; Hall et al. 2019; Meneguelli et al. 2020).

Third, these frameworks often recommend separate regulatory tools to address specific issues, a narrow conceptualisation that may limit the potential for regulation to tackle systems problems (Lawrence et al. 2015). For example, taxes are often described as a way to incentivise the purchase of healthy foods or reduce consumption of a risk nutrient, such as SSB taxes to reduce sugar consumption (Fischer and Riechers 2019; Meadows 1999). Based on these policy objectives, a SSB tax may be considered a policy ‘success’ if more products are reformulated to contain less sugar, even if excess UPF production and consumption continues (Ng et al. 2021; Pell et al. 2021; Russell et al. 2021). Given the scope and objectives of current food policy frameworks, single policy actions to address specific issues can contribute to beneficial public health outcomes. However, a focus on reductionist approaches to food policy issues may obscure the range of other options available to tackle the underpinning socio-ecological determinants.

In contrast, a broader perspective creates new possibilities for more holistically conceptualised policy actions to promote whole of food systems transformation; for example, using fiscal measures to redistribute profits from UPF corporations and fund social and health services, or more innovative options like taxes on advertising (Parker et al. 2018). Similarly, food policy frameworks often propose food labelling policies to help consumers make healthier choices (Hawkes et al. 2013; Swinburn et al. 2013). Yet in practice, labelling schemes often reflect dominant market-based and nutrient-centric approaches that can operate to benefit UPF corporations, by misrepresenting the healthiness of UPF products and potentially misleading consumers. For example, evidence suggests that the UPF industry is ‘gaming’ the nutrient profile algorithm used in Australia’s voluntary Health Star Rating FOP labelling tool to generate higher ratings (Dickie et al. 2018, 2020). If considered as a mechanism for food systems transformation, new food labelling measures could synergise with other regulatory strategies to shift power away from UPF corporations and towards other systems actors and more sustainable alternatives (Parker et al. 2020).

While current food policy frameworks do contain some policy options and objectives that consider food systems, such as recommendations for multi-sectoral ‘health-in-all-policies’ and ‘whole-of-government’ approaches, these considerations are presented as aspects of the policy framework (Hawkes et al. 2013; Swinburn et al. 2013; WHO 2013). Yet many of the policy actions focus on diet-related interventions or changes to food environments to achieve human health outcomes, rather than broader strategies to address the social, commercial, political and environmental dimensions of today’s food systems problems. Some scholars have proposed that the NOURISHING ‘food systems’ domain could be expanded to better encompass the health and sustainability dimensions of food systems, and in particular to feature interventions on environmental sustainability, multi-sector and inclusive governance structures and coordination mechanisms, and foundational tools for population-level monitoring and surveillance systems to inform policy action (Lee et al. 2020).

The potential of systems science concepts and regulatory approaches to inform responses to the UPF problem

In this section, which addresses the third objective of the review, we consider the systems science literature to better understand the places to intervene in a complex adaptive system to fundamentally change it. We also look to the field of regulatory studies to examine whether current approaches to regulation are equipped for food systems transformation, and investigate the potential for ecological regulation to reorient food systems to health and sustainability and inform responses to the UPF problem.

Leverage points and levels to intervene in complex adaptive systems

Systems science approaches seek to identify the drivers of complex systems problems and the places to intervene for maximum transformative impact (Bolton et al. 2022; Carey et al. 2015; Meadows and Wright 2009). They use ‘systems thinking’ to examine the interactions across a system that create its properties and outcomes (Clifford Astbury et al. 2021; Knai et al. 2018; Meadows and Wright 2009). Systems science approaches have been applied to analyse various public health problems, such as obesity prevention (Johnston et al. 2014), the social determinants of health (Carey and Crammond 2015), and food insecurity (Jiren et al. 2021).

An influential example of a systems science approach is Meadows’ ‘leverage points’ framework (1999) that sets out 12 places to intervene in a system, in order of the potential impact on systems change (Fig. 1). It proposes that interventions to modify the system’s ‘parameters’ – the isolated, existing parts of the system – have a low potential impact on systems change. Adjustments to parameters are sometimes described as ‘shallow’ interventions as they tackle issues one-by-one and rarely lead to radical systemic shifts (Abson et al. 2017; Fischer and Riechers 2019). In contrast, interventions to change the system’s paradigms and goals – the ‘mindset’ and objectives that underlie the system – have a high potential impact on systems change. They are referred to as ‘deeper’ interventions because they can fundamentally alter the system’s core beliefs and business-as-usual objectives (Meadows and Wright 2009; Nobles et al. 2021).

One prominent adaptation of Meadows’ framework is Malhi et al’s Intervention Level Framework (ILF) (2009), first developed in the context of food systems and later applied to other public health phenomena (Carey and Crammond 2015; Durham et al. 2018; Johnston et al. 2014; McIsaac et al. 2019). The ILF simplifies Meadows’ 12 leverage points into five levels of intervention for systems transformation (Fig. 1). The lowest level comprises the ‘structural elements’ of the system, a similar concept to parameters. The ILF then lists ‘feedback and delays’, and ‘system structure’ as levels that have more impact. It describes the goals and ultimately the paradigms of the system as the levels of interventions likely to have the most transformative impact (Johnston et al. 2014; Malhi et al. 2009). In Tables 3, we summarise the levels of intervention and build on prior studies to present examples of possible policy actions related to the UPF problem.

Leverage points frameworks present a hierarchy of places to intervene in ascending order of the potential impact on systems transformation, which corresponds to how ‘difficult’ it is to intervene at that level (Meadows 1999). This hierarchy of interventions relative to impact and difficulty usefully emphasises that “tinkering at the margins” of the system is insufficient to fix systemic problems (Meadows and Wright 2009, p. 112). However, leverage points analyses also demonstrate that multiple, complementary actions at different levels can interact to increase their collective impact (Jiren et al. 2021; Leventon et al. 2021; Nobles et al. 2021). For example, a study on transformative approaches to gender equality in Ethiopia found that gender-aware policy reforms (a relatively ‘deep’ leverage point), prompted tangible rule changes to permit women to save money or take out a loan (relatively ‘shallow’ leverage points) (Manlosa et al. 2019). In turn, this legitimised formal opportunities for women to engage in work and public life, creating the enabling conditions for a shift in social norms and attitudes around gender (a deep leverage point). Some have theorised that interventions can be joined into multi-level ‘chains of leverage’ that create momentum for change and sometimes spark the conditions for a new paradigm to flourish (Fischer and Riechers 2019).

Current regulatory approaches to food systems problems

Law and regulation can be important policy tools to help achieve public health nutrition goals at the population level, such as reducing unhealthy food consumption (Gostin 2004, 2007; Liberman 2014; MacKay 2011; Magnusson 2008a, b; Reeve and Gostin 2015; Voon et al. 2014). In this section, we look to the regulatory studies literature to analyse how three different approaches to regulation inform the choice of regulatory tools used to intervene in food systems: instrumental, responsive and ecological (Parker and Haines 2018). We highlight the transformative potential of an ecological approach to regulation to address the UPF problem.

‘Regulation’ includes legal mechanisms (such as food standards and labelling laws) but can also be used more broadly to refer to any mechanism that influences behaviour – including formal but not non-legally binding rules or ‘soft law’ (such as industry and technical standards, codes of conduct and transnational laws that lack legal enforceability), informal social norms (such as norms for eating healthy invoked by expert and civil society campaigns against ‘junk food’), market forces (such as retail price or investor expectations) and other contextual factors (such as a food environment that requires shelf-stable foods capable of travel through shipping and long supply chains) (Black 2001; Parker and Braithwaite 2012). In this respect, regulation can incorporate a range of potential tools for intervention, not just formal legal regulatory measures.

Formal legal regulation often takes an ‘instrumental’ approach to regulate the harms generated by business activities – often called market failures or ‘externalities’ – one at a time (Haines and Parker 2017; Parker and Haines 2018). An instrumental conception of regulation is premised on neo-liberal capitalist assumptions about the fundamental benefits of a competitive market, and prefers regulation that places as little burden on businesses as possible. Therefore, instrumental regulatory tools are designed narrowly to address specific harms or risks, such as excess sodium intake or single nutrient deficiencies. In some instances, this can be useful to resolve identified and often acute harms, such as to respond to toxicity issues and contribute to a safer food supply. However, instrumental regulation alone cannot address the multi-faceted and dynamic harms that arise from complex adaptive systems, like socio-cultural or environmental harms (Parker et al. 2020; Parker and Johnson 2019). It often creates a fragmented regulatory landscape that is not attuned to considerations of social and ecological wellbeing (Black 2001; Parker and Johnson 2019).

Instrumental regulation tends to benefit larger corporations who have the power to lobby to influence regulations to suit their interests, and the resources to demonstrate regulatory compliance (even if only on the surface) or fight alleged non-compliance in legal proceedings (Haines and Parker 2017). In contrast, instrumental rules create barriers to entry for smaller companies that cannot easily meet the regulatory constraints placed on their business practices (Parker and Haines 2018; Parker and Johnson 2019). An instrumental solution to one policy problem can also be counter-productive for other problems. For example, food safety requirements may indirectly incentivise the production and consumption of airtight sealed and packaged shelf-stable UPFs for catering in institutional settings.

An alternative approach, responsive regulation, proposes that governments should be ‘responsive’ to the conduct of the actors they seek to regulate, and take more coercive measures only if ‘softer’ methods to encourage voluntary compliance fail (Ayres and Braithwaite 1992). Responsive regulation approaches recognise that regulation can take many forms, and that different actors – state, markets and civil society – ‘regulate’ one another (Black 2002; Braithwaite and Drahos 2000; Eberlein et al. 2014; Scott 2001; Steurer 2013). Yet in practice, regulatory spaces are often influenced by economic and political interests, and tend to amplify the loudest voices in political and public spheres, such as transnational UPF corporations, and sideline others, like workers, animals and environments (Parker and Haines 2018). The dominant economic logic inscribed in regulations can limit the scope for regulatory actors to be responsive to non-economic, ecological values and issues (Besselink and Yesilkagit 2021). Some have noted that responsive regulation can be limited in the absence of policy goals to achieve public health outcomes and sanctions to inform and enforce effective self-regulation (Magnusson and Reeve 2014; Ngqangashe et al. 2021b; Reeve 2011). Additionally, while responsive regulatory approaches recognise the need for multiple regulatory measures to meet policy objectives, they under-emphasise the cumulative effect of different regulations to address complex system problems, and may not look at the synergies and trade-offs across entire food systems (Ingram 2011). Responsive regulatory theories also inadequately attend to the social and environmental boundaries for safe, fair and sustainable human activities, including the regulatory system itself (Parker and Haines 2018).

Ecological regulation: an approach to whole of food systems problems

Parker and Haines’ theory of ecological regulation (2018) challenges policymakers to reorient the regulatory toolkit to support socio-ecological goals and attend to the social, economic, political and environmental dimensions of complex systems challenges. Inspired by natural ecosystems, ecological regulation seeks to design a ‘regulatory ecosystem’ of legal and governance tools across multiple substantive regulatory domains, to facilitate a sustainable solution to diverse problems (Johnson 2021; Parker and Haines 2018; Parker and Johnson 2019). It also emphasises that regulations must be embedded in local and planetary ecosystems to ensure that human and business activities operate within ecological limits (Parker et al. 2020). Ecological regulation recognises that regulatory measures interact to generate a cumulative impact greater than the impact of any one action alone. It equips regulators to consider policy actions holistically to identify the synergies and trade-offs within and across systems.

An ecological approach to regulation includes a broad base of actors, issues and interests – not just dominant corporate voices, but also the voices of marginalised groups, other living species and natural ecologies. In this respect, ecological regulation itself encompasses multiple regulatory strategies that reflect diverse values and worldviews to support a sustainable system, rather than many discrete regulatory regimes that share capitalistic beliefs, values and practices and assume the benefits of competitive markets (Haines and Parker 2017). Ecological regulation recognises that corporate actors ‘regulate’ the food system using various measures; for example, formalised co-regulatory measures like industry standards of practice, corporate marketing practices that regulate individual behaviour, or lobbying in the political sphere (Parker and Haines 2018; Parker and Johnson 2019). Ecological regulation is also attuned to the ways that corporate actors develop adaptive responses to regulatory interventions to maintain the status quo and favour their commercial interests, or adopt strategies to nudge the market in another direction as markets change (Parker and Haines 2018).

Parker and Johnson (2019) have proposed that ecological regulation can be applied to facilitate a deeper analysis of the regulations needed for food systems transformation. Subsequent studies have considered the application of ecological regulation to food systems problems. For example, a study on the potential of ecological regulation to respond to the problem of intensive meat production and consumption suggested that regulatory tools may include eliminating government subsidies that benefit intensive and unsustainable meat production, strict regulation of health, safety and labor conditions in meat production facilities, and innovative options like a universal basic income or taxes on advertising to challenge the neo-liberal values and logics that perpetuate the problems of intensive meat (Parker et al. 2018). Another study on ecological regulation proposes that food labelling schemes can contribute to sustainable food systems if connected to a range of regulatory measures that generate the conditions for creating a system that produces good consumer choices, such as recognising citizens’ rights to social support and restricting unfair and unsafe labour practices (Parker et al. 2020).

Ecological regulation embraces “diversity and plurality” in policy actions and regulatory strategies (and equally in food production and consumption practices) because, like in natural ecosystems, these characteristics contribute to adaptability and resilience in food systems and food policies (Parker et al. 2020, p. 925). This emphasis on diversity, a key component of sustainable ecologies, is particularly salient in the context of food systems transformation. Expert reports have explored the need to dismantle the dominance of uniformity and monocultures in industrial agriculture and restore diversity as the imperative of agroecological systems (HLPE 2019; IPES-Food 2016). An ecological approach to regulation is important to help facilitate this paradigmatic transition as it invites regulators to pay attention to how regulatory regimes themselves may reinforce existing power structures or valorise single ‘monocultural’ solutions that stifle local initiatives and undermine different approaches better suited to tackle context-specific problems (Parker et al. 2018).

Connecting ecological regulation to leverage points frameworks

The literature suggests that ecological regulation and leverage points frameworks are conceptually compatible approaches that have the potential to inform holistic interventions in today’s food systems to promote health and sustainability. Ecological regulation and leverage points frameworks share a common emphasis on the need for nuanced and multi-level approaches to transform complex adaptive systems, such as today’s food systems, and tackle multi-faceted systems phenomena, like the rise of UPFs. They also attend to the multiple yet interrelated health, social, commercial, political and ecological dimensions of modern food system challenges.

Ecological regulation and leverage points frameworks have some differences. For example, leverage points frameworks, such as the ILF, include all kinds of interventions (e.g., programs, policy, informal social agreements) (Meadows 1999), and do not specify the nature or form of the regulatory tools used to shift the system in a particular direction. Also, the hierarchical depiction of the levels for intervention based on impact and difficulty may discount the importance of diversity in regulatory strategies, and undermine the potential significance and practical challenges of certain interventions to change the system’s structural elements. For example, a policy action to eliminate the agricultural subsidies for grains such as corn, wheat and rice, monocrops that form the basis of most UPF products, would amount to an intervention at the ‘shallow’ level of structural elements, classified in the ILF as low impact and relatively ‘easy’, despite the deep potential impact and political intractability of redirecting the substantial subsidies that benefit large monocultural agricultural corporations (Swinburn et al. 2019). However, both approaches encourage the strategic use of many different yet synergistic interventions that interact to catalyse systems change. This is reflected in the concepts of a ‘regulatory ecosystem’, central to ecological regulation, and the empirical findings and theoretical work on multi-level chains of leverage, described in leverage points analyses.

We propose that while leverage points frameworks illuminate the spectrum of places to intervene in a system, an ecological approach to regulation highlights the need for a diversity of regulatory tools that interact to transform it (Parker et al. 2017). Leverage points frameworks, such as the ILF, seek to understand how a complex system works, and direct attention to the multiple levels for interventions. In this respect, the ILF provides useful guiding principles for holistic and strategic policy design that considers where to intervene to transform a system (Meadows 1999). It offers a general framework that can help policymakers to identify and coordinate interventions across multiple leverage points to respond to complex public health problems in a way that moves the system in a new direction. Consistent with this, ecological regulation elaborates on how to use regulatory tools to intervene for socio-ecological outcomes, a reorientation that is fundamental to tackle the UPF problem and the associated harms to human health and the environment. We provide a general summary of this combined approach in Table 4. From a regulatory perspective, the theory of ecological regulation adds nuance as it specifically examines how regulatory strategies could operate to advance systems transformation. The normative element of ecological regulation also highlights the need for regulatory strategies to be responsive to ecological values and perspectives. In other words, what is needed is not just regulatory interventions, but regulatory interventions designed to respect the ecological boundaries around food systems and contribute to socio-ecological goals.

Discussion

This review aimed to critically examine whether current food policy frameworks and regulatory approaches are equipped to respond to today’s food systems problems, illustrated by the global rise of UPFs in human diets. Our findings address three key objectives and offer insights on the transformative potential of policy and regulation to drive food systems changes that tackle the UPF problem.

First, the rise of UPFs is not just a dietary harm, but an emergent property of today’s commercialised and commodified food systems. Current industrial food systems operate in a neo-liberal capitalist paradigm that values economic productivity and perpetuates a culture of consumption, with little respect for human and planetary health (Freudenberg 2021; Parker and Johnson 2019). Dominant market-oriented and nutrient-centric ideologies permeate food environments, food and nutrition policies, and the corporate political activities of UPF corporations, reinforcing the status quo in today’s food systems and driving current systems phenomena, like the rise of UPFs (Leeuwis et al. 2021; Lencucha and Thow 2019; Nestle 2022).

The prevailing neo-liberalist capitalist paradigm results in a market-based approach to regulation that responsibilises individuals to make healthier choices, entrusts the UPF industry to take a leading role in food policy processes and regulatory governance, and limits the transformative potential of regulatory interventions. This demands the application of a holistic regulatory theory to extend the conceptual parameters of what it means to regulate to promote healthy and sustainable food systems. It also underscores the need for a range of regulatory responses that generate other changes and exert a cascading influence on the entire system and related systems, rather than make multiple, minor indentations in delineated food policy domains.

Second, current food policy frameworks are not sufficiently equipped to address the whole of food systems determinants of the UPF problem. Our findings suggest that these frameworks under-emphasise key systems characteristics. In particular, these frameworks predominantly consider the structural elements of food systems, such as prices, labels or food composition, rather than tackling the deeper levels that shape food systems. They do not directly confront the neo-liberal capitalist or nutrient-centric ideologies that anchor today’s industrial food systems to business-as-usual goals and structures, industrial food production practices and financial flows that are ecologically unsustainable.

Current food policy frameworks pay insufficient attention to the possibilities for ‘deeper’ interventions at the levels of the system’s paradigms, goals and systems structures, and how such measures may complement and catalyse other changes across the system as a whole. They tend to present lists of separate policy options classified into distinct policy domains, a format that does not reflect the multiple dimensions or dynamic interactions that characterise today’s food systems problems, such as the rise of UPFs (Parker and Johnson 2018). From a systems standpoint, isolated policy actions to adjust or nudge the structural elements of food systems are not commensurate to the systems nature of the UPF industrial complex or up to the task of entire systems transformation (Lawrence et al. 2015).

While current food policy frameworks do consider food systems, they present food systems as one part of the framework rather than the foundation for it. A stand-alone ‘food systems’ policy domain or a specific policy option that recommends food systems approaches may detract from the need for all food policy actions to contribute to a whole of food systems response that has a unified and transformative impact. This raises a key question: is it enough to extend a food systems domain situated in an existing food policy framework, if that framework itself is not oriented to the socio-ecological dimensions of food systems? Given that the limitations of current frameworks relate to a weak line of systems thinking and insufficient elevation of the socio-ecological dimensions of food systems regulation, there is potential to draw on ecological approaches to regulation and systems frameworks to examine how to use regulation more effectively to intervene for whole of food systems change.

Third, the systems science concept of leverage points and an ecological theory of regulation have the potential to illuminate where and how to intervene in current food systems to advance transformative change and attenuate the rise of UPFs. Leverage points frameworks, in particular the ILF, provide a general structure that helps to organise the range of places to intervene in food systems to spark transformation (Johnston et al. 2014; Malhi et al. 2009). Ecological regulation then turns attention to the regulatory toolkit available to tackle multi-dimensional systems problems, such as the UPF problem (Parker and Haines 2018). It also shifts the focus of regulation from economics as the basis for action to ecosystems, and starts from the premise that regulation itself must respect the socio-ecological boundaries that need to remain intact for healthy and sustainable food systems – and all human activities more broadly – to flourish (Parker and Johnson 2019). This holistic approach to regulation reflects and supports the broader landscape of international movements, community initiatives and expert reports that are already challenging the dominant market-based orientation and industrial scale of food systems, and calling for joined-up policy changes to collectively move towards a fundamentally different paradigm of diversified agroecological food systems (IPES-Food 2016; Leeuwis et al. 2021).

We propose that a united conceptual lens incorporating the multi-level structure of leverage points frameworks and an ecological approach to regulation offers the principles and the tools to contribute to transformative food systems change. A combined approach has the potential to facilitate the design of a diverse set of synergistic regulatory strategies that interact with one another – and with various elements of food systems themselves – to catalyse systems transformation.

Strengths and limitations

This review draws on systems science concepts and regulatory approaches to highlight the possibilities for policy and regulation in food systems transformation. Given the complexity of today’s food systems problems, this multi-disciplinary perspective is useful to understand where and how to intervene in these systems for transformative impact. This review has some limitations. Due to the broad nature and scope of this topic, our search strategy focused on academic articles and official technical or policy reports, limited to English sources and often global in scope. This may have omitted other relevant literature, such as reports from civil society organisations or corporations, which could have affected the narrative and synthesis presented. However, the search process used collected a broad range of documents across different disciplines, relevant to the review’s three objectives. It also identified key articles from the fields of systems science and regulatory studies that did not necessarily mention UPFs or food systems but contained relevant insights on systems change or regulatory approaches.

This review presents the rise of UPFs as an illustrative example of a current global food systems problem that demands a policy response and regulatory strategies to attenuate the harms to human and planetary health. A limitation of this orientation is the lack of discussion of more healthful and sustainable food systems that exist on local or regional levels, or ‘alternative’ food systems movements. The review also mainly focuses on the role of governments to use law and regulation in food systems transformation, particularly to address the ‘harms’ of UPFs, as distinct from using regulation to promote ‘goods’ such as healthy diets. This is not intended to suggest that governments alone have the capacity to transform food systems. As this review highlights, there are many actors that regulate food systems, and our emphasis on national interventions does not detract from the important roles of the private sector, which includes a diversity of corporate actors that are not part of the UPF industry, civil society and public interest groups. Finally, we acknowledge that the narrative review and synthesis method necessarily involves some degree of author subjectivity to interpret and synthesise complex concepts from multiple disciplines. Therefore, the results and discussion of this review are inherently subject to author bias and subjective socio-cultural interpretations. To minimise these biases, we have integrated semi-systematic search processes and described the concepts, theories and frameworks considered before presenting a critical synthesis that contributes to the literature.

Conclusion

This article has examined whether current food policy frameworks and regulatory approaches are equipped to respond to the rise of UPFs in human diets and generate food systems transformation. Despite recent calls to action in the international policy sphere, the whole of food systems determinants of the UPF problem are not holistically considered under current food policy frameworks. While these frameworks adjust certain important parts of today’s food systems, they do not adequately address the deeper drivers that underlie and permeate food systems from their foundation. This limits the capacity of current frameworks to tackle today’s food systems problems, such as the UPF problem, which present substantial threats to human and planetary health.

To divert the current course and reroute in the direction of health and sustainability, a whole of food systems approach that addresses the many, interacting determinants of the UPF problem is required. This calls for an ecosystem of integrated and synergistic interventions that work at multiple points across a variety of sectors (e.g., health, agriculture, trade, environment, consumer protection) to support healthy and sustainable food systems. While a variety of coordinated and multi-level interventions are needed, rather than any one intervention in isolation, some policy examples include democratic and participatory governance structures to facilitate public health dialogues and decisions inclusive of multiple stakeholders and citizens, actions that seek to redistribute power across the food supply chain, and specific measures that adopt and apply agroecological concepts, principles and practices for population and planetary health.

Our review finds that system science concepts and an ecological approach to regulation can inform holistic policy design and regulatory tools to help drive food systems transformation, attenuate the UPF problem and reduce related harms. Leverage points frameworks, such as the ILF, provide useful organising principles to guide policy action on the places to intervene in complex adaptive food systems. To extend this line of systems thinking into regulatory policy and practice, ecological regulation emphasises how to regulate for sustainable solutions to multi-dimensional problems, like the rise of UPFs. Given the magnitude of current socio-ecological crises, there is substantial scope for future research that develops our understanding of how to use ecological regulation to respond to the UPF problem and promote global food systems transformation. A unified conceptual lens that combines a leverage points analysis and an ecological regulatory approach has the transformative potential to highlight where and how to intervene to create holistic systems changes that collectively support a healthier and more sustainable future for global food systems.

Abbreviations

- FAO:

-

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- HLPE:

-

High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition

- ILF:

-

Intervention Level Framework

- NCDs:

-

Non-communicable diseases

- SSB:

-

Sugar-sweetened beverages

- UPFs:

-

Ultra-processed foods

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Abson, D., J. Fischer, J. Leventon, J. Newig, T. Schomerus, U. Vilsmaier, and H. Wehrden, et al. 2017. Leverage points for sustainability transformation. AMBIO - A Journal of the Human Environment 46 (1): 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y.

Allen, L. N., J. Pullar, K. K. Wickramasinghe, J. Williams, N. Roberts, B. Mikkelsen, and C. Varghese, et al. 2018. Evaluation of research on interventions aligned to WHO ‘best Buys’ for NCDs in low-income and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review from 1990 to 2015. BMJ Global Health 3 (1): e000535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000535.

Anastasiou, K., P. Baker, M. Hadjikakou, G. Hendrie, and M. Lawrence. 2022. A conceptual framework for understanding the environmental impacts of ultra-processed foods and implications for sustainable food systems. Journal of Cleaner Production 368: 133155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133155.

Anderson, M. D. 2008. Rights-based food systems and the goals of food systems reform. Agriculture and Human Values 25 (4): 593–608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-008-9151-z.

Askari, M., J. Heshmati, H. Shahinfar, N. Tripathi, and E. Daneshzad. 2020. Ultra-processed food and the risk of overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. International Journal of Obesity 44 (10): 2080–2091. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-020-00650-z.

Ayres, I., and J. Braithwaite. 1992. Responsive regulation: transcending the deregulation debate. New York: Oxford University Press.

Baker, P., and S. Friel. 2016. Food systems transformations, ultra-processed food markets and the nutrition transition in Asia. Globalization and Health 12 (1): 80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-016-0223-3.

Baker, P., C. Hawkes, K. Wingrove, A.R. Demaio, J. Parkhurst, A.M. Thow, and H. Walls. 2018. What drives political commitment for nutrition? A review and framework synthesis to inform the United Nations Decade of Action on Nutrition. BMJ Global Health. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000485.

Baker, P., A. Kay, and H. Walls. 2014. Trade and investment liberalization and Asia’s noncommunicable disease epidemic: a synthesis of data and existing literature. Globalization and Health 10 (1): 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-014-0066-8.

Baker, P., J. Lacy-Nichols, O. Williams, and R. Labonté. 2021. The political economy of healthy and sustainable food systems: an introduction to a special issue. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 10: 734–744. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2021.156.

Baker, P., P. Machado, T. Santos, K. Sievert, K. Backholer, M. Hadjikakou, and C. Russell, et al. 2020. Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obesity Reviews 21 (12): e13126. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13126.

Bakhtiari, A., A. Takian, R. Majdzadeh, and A. A. Haghdoost. 2020. Assessment and prioritization of the WHO “best buys” and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases in Iran. Bmc Public Health 20 (1): 333. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8446-x.

Béné, C., J. Fanzo, S. D. Prager, H. A. Achicanoy, B. R. Mapes, P. Alvarez Toro, and C. Bonilla Cedrez. 2020. Global drivers of food system (un)sustainability: a multi-country correlation analysis. PloS One 15 (4): e0231071. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231071.

Benton, T. G., T. Bieg, H. Harwatt, R. Pudasaini, and L. Wellesley. 2021. Food system impacts on biodiversity loss: three levers for food system transformation in support of nature. London: Chatham House.

Besselink, T., and K. Yesilkagit. 2021. Market regulation between economic and ecological values: Regulatory authorities and dilemmas of responsiveness. Public Policy and Administration 36 (3): 304–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076719827630.

Black, J. 2002. Critical reflections on regulation. Australian Journal of Legal Philosophy 27: 1–35.

Black, J. 2001. Decentring regulation: understanding the role of regulation and self-regulation in a ‘post-regulatory’ world. Current Legal Problems 54 (1): 103–146. https://doi.org/10.1093/clp/54.1.103.

Bolton, K. A., J. Whelan, P. Fraser, C. Bell, S. Allender, and A. D. Brown. 2022. The Public Health 12 framework: interpreting the ‘Meadows 12 places to act in a system’ for use in public health. Archives of Public Health 80 (1): 72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-022-00835-0.

Braithwaite, J., and P. Drahos. 2000. Global business regulation. Cambridge, UK: CUP.

Brandon, I., P. Baker, and M. Lawrence. 2020. Have we compromised too much? A critical analysis of nutrition policy in Australia 2007–2018. Public Health Nutrition 24 (4): 755–765. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020003389.

Capacci, S., M. Mazzocchi, B. Shankar, J. Brambila Macias, W. Verbeke, F. J. Pérez-Cueto, and A. Kozioł-Kozakowska, et al. 2012. Policies to promote healthy eating in Europe: a structured review of policies and their effectiveness. Nutrition Reviews 70 (3): 188–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00442.

Carey, G., and B. Crammond. 2015. Systems change for the social determinants of health. Bmc Public Health 15: 662–671. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1979-8.

Carey, G., E. Malbon, N. Carey, A. Joyce, B. Crammond, and A. Carey. 2015. Systems science and systems thinking for public health: a systematic review of the field. British Medical Journal Open 5 (12): e009002. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009002.

Chen, X., Z. Zhang, H. Yang, P. Qiu, H. Wang, F. Wang, and Q. Zhao, et al. 2020. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health outcomes: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Nutrition Journal 19 (1): 86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-020-00604-1.

Clapp, J. 2019. The rise of financial investment and common ownership in global agrifood firms. Review of International Political Economy 26 (4): 604–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1597755.

Clapp, J., and G. Scrinis. 2017. Big food, nutritionism, and corporate power. Globalizations 14 (4): 578–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2016.1239806.

Clifford Astbury, C., E. McGill, M. Egan, and T. L. Penney. 2021. Systems thinking and complexity science methods and the policy process in non-communicable disease prevention: a systematic scoping review protocol. British Medical Journal Open 11 (9): e049878. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049878.

Corbin, J., and A. Strauss. 2008. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Corvalán, C., M. Reyes, M. L. Garmendia, and R. Uauy. 2013. Structural responses to the obesity and non-communicable diseases epidemic: the chilean law of food labeling and advertising. Obesity Reviews 14 (Suppl 2): 79–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12099.

Cullerton, K., T. Donnet, A. Lee, and D. Gallegos. 2016. Playing the policy game: a review of the barriers to and enablers of nutrition policy change. Public Health Nutrition 19 (14): 2643–2653. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980016000677.

da Silva, J. T., J. M. F. Garzillo, F. Rauber, A. Kluczkovski, X. S. Rivera, G. L. da Cruz, and A. Frankowska, et al. 2021. Greenhouse gas emissions, water footprint, and ecological footprint of food purchases according to their degree of processing in brazilian metropolitan areas: a time-series study from 1987 to 2018. The Lancet Planetary Health 5 (11): e775–e785. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00254-0.

Development Initiatives. 2021. Global nutrition report 2021: the state of global nutrition. Bristol, UK: Development Initiatives.

Diaz-Bonilla, E., F. Paz, and P. Biermayr-Jenzano. 2020. Nutrition policies and interventions for overweight and obesity: a review of conceptual frameworks and classifications. In Nutrition policies and interventions for overweight and obesity: a review of conceptual frameworks and classifications, LAC Working Paper 6. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Dickie, S., J.L. Woods, P. Baker, L. Elizabeth, and M.A. Lawrence. 2020. Evaluating nutrient-based indices against food- and diet-based indices to assess the health potential of foods: how does the Australian Health Star Rating System perform after five years? Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12051463.

Dickie, S., J.L. Woods, and M. Lawrence. 2018. Analysing the use of the Australian Health Star Rating system by level of food processing. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0760-7.

Durham, J., L. Schubert, L. Vaughan, and C. Willis. 2018. Using systems thinking and the intervention Level Framework to analyse public health planning for complex problems: Otitis media in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. PloS One 13: e0194275. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194275.

Eberlein, B., K. W. Abbott, J. Black, E. Meidinger, and S. Wood. 2014. Transnational business governance interactions: conceptualization and framework for analysis. Regulation & Governance 8 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12030.

Elizabeth, L., P. Machado, M. Zinöcker, P. Baker, and M. Lawrence. 2020. Ultra-processed foods and health outcomes: A narrative review. Nutrients 12 (7): 1955. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12071955.