Abstract

How do crisis conditions affect longstanding societal narratives about hunger? This paper examines how hunger was framed in public discourse during an early period in the COVID-19 crisis to mobilize attention and make moral claims on others to alleviate it. It does so through a discourse analysis of 1023 U.S.-based English-language posts dedicated to hunger on Twitter during four months of the COVID-19 pandemic. This analysis finds that Twitter users chiefly adopted hunger as a political tool to make moral claims on the state rather than individuals, civil society organizations, or corporations; however, hunger was deployed to defend widely diverse political agendas ranging from progressive support for SNAP entitlements to conservative claims reinforcing anti-lockdown and racist “America First” sentiments. Theoretically, the paper contributes to understanding how culture and morality operate in times of crisis. It demonstrates how culture can be deployed in crisis to reinforce longstanding ideological commitments at the same time that it organizes political imaginations in new ways. The result, in this case, is that longstanding cultural narratives about hunger were used to defend dissimilar, and in some ways contradictory, political ends. Practically, the paper demonstrates how moralized calls to alleviate hunger are vulnerable to political manipulation and used to further conflicting political goals, yet may also offer opportunities to leverage support for bolstered state investments in food assistance during times of crisis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit the United States in March of 2020, it became clear that it would pose formidable social and economic challenges alongside its public health threats. One area in which those impacts manifested most clearly was around food insecurity. The pandemic shut down U.S. schools and businesses and triggered job losses in ways that risked plunging millions into poverty and skyrocketing food insecurity along with it. Indeed, early statistics indicated that food insecurity rates were rising markedly (Bauer 2020; Bitler et al. 2020). For instance, early research from the Census Household Pulse Survey reported that food insecurity rates doubled overall and tripled among households with children in the first four months of the pandemic (Schanzenbach and Pitts 2020). Similarly, over five million more people applied for and received SNAP benefits (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program – formerly known as food stamps) in the first seven months of the pandemic than in the year prior (USDA 2021). Emergency food assistance providers like food banks and pantries were likewise reporting demand beyond capacity, with need rising as high as 50% (Feeding America 2020).

Food insecurity statistics such as these acted as a striking touchstone in early public discourse for the pandemic’s damaging social and economic impacts. Subsequent research on food insecurity from this period has since shown that these disastrous outcomes were mostly concentrated in the early pandemic period (Schanzenbach and Pitts 2020) and were otherwise averted due to adjustments in federal food and social assistance programs, with a few notable exceptions: marked rises in food insecurity throughout 2020 were experienced by those in the American South, as well as among households with children, Black households, and households with a member who was unemployed or unable to work due to the pandemic (Coleman-Jensen et al. 2021; Morales et al. 2021).

The above nuances were not known early in the pandemic. Instead, Americans received regular messages about magnitudes of hunger exceeding anything the nation had experienced since the Great Depression alongside heart-wrenching images and stories documenting their manifestation in daily life. News stories told of children going hungry after losing access to school meal programs. Photos of unpicked crops going rotten in fields were juxtaposed with those of cars lined up for miles waiting to receive food bank provisions. Headlines in The New York Times read that, “A shadow of hunger looms over the United States” and that, “Instead of Coronavirus, the hunger will kill us.” Among the pandemic’s many devastating impacts, hunger loomed large in the public eye, especially in its early days.

But how did the crisis conditions of the early pandemic shape how people talked about hunger on social media? And how were various state, civil society, individual, and corporate actors implicated in online conversations about feeding hungry families? Food insecurity scholarship to date has pointed to the many ways that the existing structure of U.S. food assistance has failed to ensure that vulnerable Americans have adequate access to food and left over 35 million people hungry before the pandemic (Carney 2015; Dickinson 2019; Riches 2018). This literature has also shown that while Americans have historically cared deeply about hunger,Footnote 1 their caring has not led to effective solutions, particularly ones that reflect state-level investments in poverty alleviation and a right to adequate food (Anderson 2013, 2020; Dickinson 2019; Fisher 2017; Jarosz 2015; Poppendieck 2013).

At the same time, the early pandemic period presented several historically distinct conditions that suggest that public attention on hunger during that period could diverge from previous understandings in ways that could motivate more substantive transformations in poverty alleviation and food provisioning. First, the magnitude of food insecurity experienced early in the pandemic appeared to outweigh that seen in decades. Heightened need may amplify the perceived necessity of meaningful change and catalyze new opportunities for enacting it. Second, the proximity of the average American to hunger was thrown into sharp view early on when panic buying coupled with supply chain disruptions led to shortages of many household food staples such as flour, eggs, and yeast. While this “specter of hunger” was ultimately borne out only among those most marginalized (Dickinson 2020), multitudes of Americans who had otherwise been comfortably food secure were confronted with the precarity of that status in ways that may add urgency to their reactions to hunger. Third, the pandemic cast renewed light on people’s relationships with others, asking them to reflect on their collective responsibilities and reconsider their obligations to their communities and society’s most vulnerable. As Luft has put it, we were “called on to broaden our universe of moral obligation” (2020, p. 2).

To be sure, a complete assessment of the impacts of the pandemic period will take years to emerge. This paper has a more modest goal – to begin to understand the public appetite for change amid the crisis conditions wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic and examine how and where people chiefly saw that change occurring. This paper asks, how did crisis conditions produced from the COVID-19 pandemic shape societal narratives about hunger? And, how did people position various state, civil society, individual, and corporate actors within calls to action to address hunger? I examine these questions within the realm of public discourse on social media, and particularly on Twitter. Drawing from framing theory (Snow and Benford 1988), I investigate the frames that Twitter users deployed around hunger to mobilize attention and make moral claims on the various actors identified above. I address this through a discourse analysis of 1023 US-based English-language posts dedicated to hunger on Twitter between October 2020 and January 2021– a period notably marked by particular unease and disruption in the United States due to its situation within the contested 2020 presidential election.

As an online social network microblogging platform, Twitter offers users the ability to consume varied forms of media and share short messages, links, and images either publicly or privately within a predetermined community. The form encourages a fast and frequent communication style compared to long-form blogging. Users can send tweets to all those within their community, known as their “followers,” but can also direct tweets to a specific account even if that account does not follow them. As such, Twitter offers users the ability to engage directly with others, including influential public figures such as celebrities, journalists, and politicians, in “dialogic” rather than unilineal ways (Barnes 2017). Social media activity rose sharply across several platforms during the early pandemic period as people flocked to share and consume media and participate in global conversations about COVID and other social issues (Washington Post 2020). Twitter itself saw its sharpest rise in daily users during the pandemic since it started reporting daily use in 2016 (Twitter 2021).

This work builds on a growing body of research that sees online behavior as a legitimate and telling form of social behavior. While the demographics of Twitter users differ from the general population in important ways – as a whole, they are younger, more highly educated, and more likely to identify as Democrats – Twitter has been shown to offer valuable insights into public opinion, especially around political positions, social movements, and collective action (e.g., Flores 2017; Scarborough 2018; Tovares and Gordon 2020). I consider people’s engagements on Twitter as part of what Perrin calls the “democratic imagination,” or people’s landscape of “what [they] can imagine doing: what is possible, important, right, and feasible” (2006, p. 2). Perrin draws on Swidler (1986; 2001) to call attention to the cultural “tools” that people possess and deploy while discussing politics and argues that those discussions are a critical aspect of social citizenship (see also Huddart Kennedy et al. 2018). Attention to these cultural tools is especially pertinent during the pandemic because this period represents what Swidler (1986; 2001) calls “unsettled times.” Swidler argued that in periods of social transformation, upheaval, and crisis, people commonly practice unfamiliar habits and learn new ways to act such that it becomes easier to see culture’s role in informing them (1986, p. 278 − 81). As an especially “unsettled” period, the COVID-19 pandemic therefore offers an opportunity to examine how crisis conditions shape people’s strategies of action in ways that are particularly visible or analyzable.

In the following sections, I begin by locating this study within the history of food insecurity policy and sentiment within the United States and the recent expansion of digital media as a venue for communication, politics, and activism around food. Next, I describe the data I collected and the methodology I used to mine, clean, and analyze posts on Twitter. In presenting my findings, I show how hunger was widely used to make moral claims on the state and state representatives during this crisis period. However, I also demonstrate how hunger was deployed to defend vastly diverse political agendas, and with it, lines of action through these calls. In my discussion, I consider the implications of these findings for food justice organizing around food insecurity as well as scholarly understandings about how culture and morality operate in “unsettled times.”

Background: Hunger in America

How can hunger exist within a nation as prosperous as the United States? The “specter of hunger” (Dickinson 2020) that marked the early pandemic was alarming, in part, because it drew attention to the ineffectiveness of capitalist food and economic distribution systems within wealthy nations like the United States, which undoubtedly produce enough food to feed their populations. However, the tragedy of hunger itself and the paradox of “want amid plenty” (Poppendieck 2013, p.189) are not new. Rather, hunger has been an enduring feature of American food and economic systems, even in times of prosperity (Dickinson 2019; Levenstein 1993, p. 144–159). In their detailed ethnographic investigation into food and labor policy in the U.S., Dickinson (2019) outlines how today’s food assistance infrastructure works less to alleviate food insecurity than to buttress low-wage work and encourage civil society organizations to take responsibility for poverty. Dickinson points to the expansion of U.S. food assistance since the 1980s and ties it to crucial transformations in the labor market and the welfare state. These transformations, especially welfare reforms instituted across the mid-1980 and 1990 s, have exacerbated income inequalities because they restrict access to cash assistance and tie social assistance– including food assistance– to work status (Collins and Mayer 2010; Maskovsky and Goode 2001). Currently, U.S. food assistance is structured as a two-tiered system whereby those who are food insecure can access federal programs such as SNAP, but usually only if they hold employment. These supports are supplemented by emergency food providers (e.g., food banks and pantries) operating through public-private partnerships in the charitable food sector. Dickinson argues that the growing food safety net has become an essential infrastructure supporting these welfare reforms, acting as “technocratic fixes to the problems of economic insecurity, based in policies designed to push people into the labor market rather than to protect them when the market fails” (2019, p. 16).

What Dickinson (2019) and other food insecurity scholars (e.g., Chilton and Rose 2009; Jarosz 2015; Fisher 2017; Poppendieck 2013; Power 1999; Riches 2018) make clear is that the existing structure of food assistance in the U.S. and elsewhere in the Global North has done little to change the structural conditions underlying food insecurity – namely, those that contribute to maintaining poverty such as stagnating wages, un- and underemployment, housing instability, and legacies of racism and colonialism. Instead, through the expansion of emergency food providers, governments in the Global North have transferred responsibility for hunger onto the civil society sector and disconnected food assistance from poverty alleviation. In doing so, they also center food provisioning within transnational corporate interests rather than the needs of citizens. As Fischer states, “the anti-hunger industrial complex, in which food charity remains a significant element, is the product of deep-rooted financial, political, and organizational connections between anti-hunger groups, USDA, and corporate America” such that the existence and growth of this system are “now integrally linked to the nation’s economy and political system” (2017, p. 262).

Indeed, many changes to food assistance in the United States since the 1960s have come alongside keen attention to public concern around hunger and have mobilized that concern to build support for those changes in complex and contradictory ways. Hungry people – especially hungry families and children – have long captivated public attention and eaten at people’s consciences in ways that few social issues have (Kotz 1969; Levenstein 1993, p. 144–159). Hunger draws attention to income inequality and food distribution failures in visceral, shocking ways that quickly arouse sympathy and mobilize action, albeit in selective ways that draw on problematic moral economies of deservingness (see Dickinson 2019 and Carney 2015). As Poppendieck argues, hunger has an enormous capacity to mobilize action from both public and private actors across the political spectrum because, on the one hand, addressing it appears as a “universal good” or “old-fashioned moral absolute” within an otherwise shifting sea of social and political values, and on the other hand, because it is perceived as solvable amid America’s clear abundance (2013, p. 564). Hunger has enormous emotional valence because it is at once relatable and imaginable but also visceral and shocking.

The galvanizing power of hunger helps explain both contemporary concerns about hunger during the pandemic and the explosion of food assistance efforts across the U.S. over the past fifty years. As Poppendieck writes, food assistance efforts “provide a sort of moral relief from the discomfort that ensues when we are confronted with images of hunger in our midst, or when we are reminded of the excesses of consumption that characterize our culture” (2013, p. 564). Importantly, Poppendieck argues that hunger’s emotional and moral salience make it vulnerable to temporary, token solutions such as food charity. Dickinson (2019) likewise contends that by contracting out responsibility for hungry citizens to food charities, states bypass pressure for more substantive political change because the face of social support is a volunteer rather than a bureaucrat (see also Maskovsky and Goode 2001; Fischer 2017). In short, this research reveals that while the specter of hungry families looms large on people’s consciences, it is quite easily mollified by piecemeal, shallow responses operating within the charitable food sector.

An important alternative to this existing food assistance framework is a rights-based approach to food insecurity (Anderson 2013; Chilton and Rose 2009). Rights-based approaches involve acknowledging that access to healthy food is a human right protected by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. While the United States supports political and civil rights under the Declaration, it is one of only four countries that have not ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), under which the right to adequate food is inscribed. Advocates of a rights-based approach to adequate food and nutrition argue that acknowledging this right can lead to significant transformations in U.S. food assistance including: explicit acknowledgement of the state’s obligation to ensuring its citizens are fed; a stable, coherent infrastructure that guarantees healthy food entitlements to all citizens regardless of eligibility; a system of accountability to identify and redress governments’ failures to protect and fulfill the right to adequate food, and corporations’ efforts to undermine it; and acknowledgement and support for eliminating the structural conditions producing food insecurity (Anderson 2020; Bellows 2020; Riches 2020). Shifting the national conversation towards a right to food is challenging– in part due to a lack of public urgency around hunger due to its depoliticization, as discussed above – but is feasible if enough political pressure is exerted to ratify and commit to ICESCR.

This backdrop of food insecurity in America provides ample cause for skepticism about the transformative potential of public interest in hunger overall. However, some specific circumstances surrounding the pandemic suggest that a global public health crisis may reconfigure dominant societal narratives about hunger, namely, the apparent gravity of the issue, its closeness to the average American, and its reconfiguration of cultural narratives about collective responsibility and people’s moral obligations to one another (Luft 2020). Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic represents what Swidler (1986; 2001) has called “unsettled times,” a period where new ideological frameworks are circulating in public life, offering people “strategies of action” that they may not have previously considered. Swidler’s framework is helpful to apply to this case because it considers culture not as a unified whole that pushes action in a consistent direction but instead as a “toolkit” or “repertoire” of symbols, stories, rituals, and worldviews that people draw from to construct lines of action within different circumstances (2001, p. 24–25). Notably, Swidler argued that periods of social transformation, upheaval, and crisis – those such as the COVID-19 pandemic – offer new “tools” or “repertoires” to people (1986, p. 278 − 81); these tools are also more visible in people’s deliberative statements in “unsettled times” because culture is less integrated with people’s values (1986, p. 284).

These distinct conditions suggest that the pandemic context may produce cultural shifts that transform the way people think and talk about hunger, and these shifts may be identifiable via people’s deliberative statements on social media. In turn, digital media platforms such as Twitter offer distinct avenues for lay citizens to engage with food justice issues and political activism. The remainder of this section will introduce literature on food, digital media, and activism to situate hunger rhetoric within these growing digital platforms and consider the possibilities they present for understanding hunger-focused calls to action during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Digital media and food activism

Digital media has played a rapidly growing and transformative role in many areas of the foodscape, including food activism (e.g., Al Zidjaly et al. 2020; Guthman and Brown 2016; Rousseau 2012). Digital media platforms, especially Twitter and Facebook, represent growing transnational spaces for activists to communicate their messages and organize collective action (Schneider et al. 2018). For example, Mann (2018) has shown how food security advocates in Australia have used Twitter to impact policy on the right to food. While Australia has ratified ICESCR, the treaty’s aims have not always been well reflected in the country’s national policies. The Right to Food Coalition studied by Mann was attempting to shift the national policy conversation from one of food charity to adequate food and nutrition as a human right. By analyzing networks of associations between Twitter users, hashtags, and media objects such as URLs, Mann demonstrates how activists employed Twitter to raise awareness about household food insecurity and attempt to lobby politicians to lead policy changes that ensure more equitable food access.

Collective forms of food politics such as those enacted by the food insecurity activists in Mann’s study are often framed in contrast to lay citizens’ engagements in food politics chiefly centered around consumer-citizenship (e.g., Huddart Kennedy et al. 2018). Over the past few decades, consumer interest in food politics has been dominated by “vote with your fork” efforts whereby individuals aim to voice their political opinions and enact change through their consumption choices. Weighing the merits and limitations of consumer-focused approaches to food system change is a delicate balance; however, most scholars agree that the consumer subjectivities produced through these approaches – that are enacted in both purchasing practices (Johnston and Szabo 2011) and engagements on digital media (Guthman and Brown 2016) – reproduce problematic neoliberal goals and approaches to social change centered in individual market decisions (Guthman 2008; Johnston 2008; Roff 2007). Researchers also weigh the democratic potential of online political engagements more generally by drawing attention, on the one hand, to their potential to disrupt traditional gatekeeping within media (e.g., Castells 2015), and on the other, to their function as illusionary performances of ‘slacktivism’ or ‘clicktivism’ (e.g., Morozov 2009).

Beyond consumption, digital media platforms can operate as spaces for a wider breadth of political participation around food issues, including engagements in democratic discourse as well as assertions and contestations of proper citizenship (Al Zidjaly et al. 2020; Schneider et al. 2018; Sutton et al. 2013). For example, Al Zidjaly, Al Moqbali, and Hinai (2020) demonstrate how the hashtag #Chips_Oman was used on Twitter to indirectly defend a national identity under threat and later negotiate internal national moral orders after an offensive video of the popular Omani snack went viral in the United Arab Emirates. Al Zidjaly and colleagues’ research illustrates that digital media platforms can be sites where political actions not only occur but are discussed and contested through discourses of civic engagement.

Taking lay citizens’ discussions on Twitter seriously means acknowledging their embeddedness in hegemonic ideological structures while also recognizing their legitimacy for democratic citizenship. I draw on Perrin’s (2006) concept of the democratic imagination to do so. Perrin argues that discussions of politics and political engagement represent an important part of democratic citizenship because they allow citizens to “think about the social world they are addressing. [They] provide the fodder for creativity, leading people to envision modes of citizenship that apply new tools to political problems” (2006, p. 51). Drawing from Swidler (1986; 2001), Perrin urges scholars to consider the cultural “tools” that make up those discussions to understand how citizens frame democratic possibilities. Perrin’s concept has proven helpful for thinking through the possibilities and limitations of consumer-based approaches to food politics (Huddart Kennedy et al. 2018). I apply the democratic imagination here to understand how people frame the possibilities for hunger alleviation and who they consider responsible for leading those efforts during a period of crisis.

Data and methodology

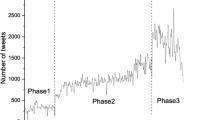

I examine public opinion on hunger by analyzing 1023 U.S.-based English-language posts dedicated to hunger on Twitter from October 2020 to January 2021. This period began seven months after much of the country instigated lockdown measures in March of 2020, and an initial government stimulus package was passed in April of 2020. Vaccines had begun to receive approval part way through this period, in December 2020, and had only begun to be distributed among select groups by the end of January 2021. Notably, this is an especially “unsettled” moment within the U.S. pandemic period and a particularly critical one for hunger politics in the country due to the presential election held in November of 2020. This period includes the immediate runup to the November election, its contestation afterward due to unfounded claims of voter fraud by Donald Trump, the runoff election in Georgia, debates around a COVID relief bill, and the inauguration of Joe Biden. The unsettled nature of this context likely had an amplifying effect on discourse through the heightened tensions and stakes involved in the election; conversation around political priorities, policies, and actions were particularly acute.

In collecting data, I mined (i.e., searched and retrieved) tweets twice monthly over the four months using the statistical software R Studio. R Studio has several coding packages and Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) available to support this process, including rtweet, tidyverse, and dplyr used for this data. These packages are commonly used to allow two different programs (in this case, R Studio and Twitter) to share information, retrieve tweet data, and ready it for analysis. I mined tweets containing either “hunger” or “hungry” in addition to “covid,” “quarantine,” or “corona.” I also searched explicitly for tweets containing the terms “family,” “kids,” or “children” because I was interested in how families and children were framed within this discourse, given that they tend to feature prominently and hold particular weight within hunger discourse more generally. I initially included the term “food insecurity” in my search keywords but abandoned it after the results showed that this was a term chiefly used by people working in food assistance and academia rather than lay citizens, who were instead using hunger terminology. Each mining instance retrieved data going back approximately one week or to a delineated maximum of 400 tweets. Through twice-monthly mines, data were therefore collected for about two weeks’ worth of tweets each month, or slightly less for weeks that reached the 400-tweet maximum. I downloaded mined data into CSV files and cleaned them immediately. Data were cleaned by removing non-English language tweets, duplicate tweets, and tweets obviously produced by bots (e.g., those with the word “bot” in the title or nonsensically accumulating statements). For this paper, I limited data to tweets either tagged in the United States or explicitly referencing U.S. geographic areas, institutions, or political topics.

Framing theory guides the analysis in this paper (Benford and Snow 2000; Entman 1993; Snow and Benford 1988). Here, frames are considered the narrative or discursive elements of culture. Frames assign meaning to an aspect of culture and make it salient or tangible within social life. At the same time, the salience of frames also depends on their situation within social life and are elevated or constrained within varied social conditions. Frames co-exist alongside other cultural objects and are actively produced and manipulated by individuals in their day-to-day lives. Within the context of social movements, frames commonly diagnose a social problem, suggest solutions or prognoses for resolving it, assign moral judgment to those involved, and/or work to mobilize actors towards a particular end (Entman 1993; Snow and Benford 1988).

The frames identified in this paper emerged inductively as I cleaned and mined the data over time. After each data mining instance, I wrote memos where I kept track of broad themes I saw emerging and refined them as I returned to the data each time. Once all the data were collected, I conducted a round of focused coding on the entire dataset to solidify the key frames. Original tweets were regularly pulled up throughout the analysis to better understand and contextualize their content within their conversations with others or links that they shared. Not all original tweets could be retrieved in cases where the tweet had since been deleted or the account had been shut down or made private. I maintain these tweets within the dataset, however, as they are representative of the discourse during the specified period. In recognition of privacy issues inherent in internet data (Markham 2012), I make efforts to anonymize and “fabricate” the data. Usernames have been removed and tweets edited slightly (i.e., by adjusting their punctuation, abbreviations, or tense) so that they cannot be searched.

Findings: the insufficiency, unfairness, and misdirection of state attention to hunger

Significantly, analyzing Twitter posts during the designated period reveals that hunger was used to make moral claims on the state and state representatives over and above any other actor. A striking 75% of all tweets (758 total) were focused on the role of governments or government representatives in addressing hunger. This is compared to those focused on individual, civil society, or market efforts such as food charities and the role that individuals or organizations play in supporting them, which only accounted for 22% of tweets (235). An additional 3% of all tweets (31) were simply informative, stating food insecurity statistics alone without implicating any actors in its cause or resolution.

In tweets focused on the state, I find that hunger acted as a moralized rallying cry to define failures in governance and motivate calls to action during crisis. Importantly, however, hunger was deployed to defend diverse political agendas. I identify three dominant frames through which hunger operates within this discourse: (1) insufficiency, (2) unfairness, and (3) misdirection. Each of these frames identify hunger – especially child hunger – as an urgent area of moral concern. All also implicate the state in addressing hunger by either identifying how existing government policies, priorities, or actions fail hungry families or by advocating for more significant government investments or attention towards food assistance. However, each frame reflects distinct socio-political assumptions about why hunger exists and how it should be resolved. As will become apparent in the findings below, tweets in the first two frames were widely directed at Republican representatives; however, some were also applied to Democrats. In contrast, the third frame most commonly, but not exclusively, critiqued Democratic representatives or actions.

Additionally, tweets within this sample included regular engagements with other users in ways that indicate direct participation in public dialogue with others. Narrowing in on tweets dedicated to the state specifically, 54% of tweets demonstrated direct communication with state officials or representatives through @ mentions. Another 33% included engagements with other users, celebrities, media, or journalists, while 3% utilized more indirect engagements such as hashtags or subtweets to locate their tweet within broader online political conversations. Together, 90% of tweets focused on the state therefore attempted to directly engage with other users or situate their tweet within public conversations about the topic.

The insufficiency of government entitlements to hungry families

Hunger was commonly drawn on to highlight the inadequacy of government entitlements (such as SNAP) supporting the poor during the pandemic and encourage governments or government representatives to do more to bolster that support. This frame represents approximately one-third of all tweets (319). Tweets by the two users below exemplify common sentiments in this frame, respectively highlighting the inadequacy of existing government support for the poor or calling for bolstered support.

@senatemajldr A covid relief bill has been sitting on Mitch McConnell’s desk since May and he refuses to bring it to the Senate for a vote. Yet this motherf–er is talking about “bigger than politics.” Americans are losing their businesses and their homes. Their children are going hungry. (November 2020)

Food insecurity has doubled for adults and tripled for families with children because of the pandemic. The need is absolutely monumental, and it’s going to get worse unless the federal government steps in. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/staggering-need-covid-19-has-led-to-rising-levels-in-food-insecurity-across-the-u-s/ (October 2020)

As a whole, tweets in this frame included the most specific prognostic statements – i.e., those that proposed strategies for resolving problems related to food insecurity rather than simply identifying hunger as a problem (Snow and Benford 1988). Many Twitter users, for example, demanded that government representatives increase state funding for SNAP provisions. Multiple users over this period shared a call to action from a United Way campaign, offering variations of this tweet: “Since COVID-19, there has been a spike in families experiencing food insecurity. Congress: don’t let 14 million children go hungry. Increase monthly #SNAP benefits by 15% now. #BoostSNAPNow.”

Many Twitter users also advocated for the election of particular candidates who would presumably build food and poverty alleviation infrastructure, as with the user below:

Georgia: hunger is on the ballot January 5. Mitch McConnell refuses to release money for COVID relief. He’d rather see mothers and children hungry. YOU have the power to change this. Electing @ReverendWarnock and @ossoff will give us all a Congress that will fight hunger. #GAsen. (November 2020)

Tweets within this frame were also most likely to identify the pandemic’s role in exacerbating existing racial and economic inequalities in food access and health. As with the following:

@urbaninstitute says that 20% of all households (& 24% of those with kids) are facing #hunger. It’s even worse (28–30%) for Black & Latinx families. These numbers are staggering. Elected leaders MUST act. @CleFoodBank @OhioFoodbanks @GovMikeDeWine @ElectMattDolan https://www.urban.org/research/publication/food-insecurity-edged-back-after-covid-19-relief-expired# (November 2020)

Hunger was sometimes amassed with other social issues such as unemployment, housing insecurity, border control, health insurance, or rising COVID case rates, as with the tweet here: “@VoteMarsha @realDonaldTrump When are you going to work for us in your state? Uninsured children and adults. COVID-19 rates up. Hospitalizations up. Unemployment. Evictions. Kids hungry” (November 2020). Through tweets such as the two above, users signal awareness of the broader systemic roots of hunger within poverty and legacies of racism and colonialism, albeit loosely. This form of recognition was most often coupled with a vague provocation for leaders to “act” rather than advocating for specific solutions at the level of poverty alleviation or racial justice; however, such provocations were not altogether absent, as with the following user, who drew connections between food and housing insecurity: “@marcorubio @SenRickScott Please pass an appropriate COVID relief package now. Renters and landlords are suffering. Children are suffering. All Americans are suffering. Food & housing insecurity are not partisan issues #rentreliefnow” (October 2020).

Overall, the insufficiency frame demonstrated fewer partisan leanings than other frames as invoked explicitly by the above user’s statement about food and housing insecurity as “non-partisan issues.” To be sure, Republican leaders were central in many assertions of insufficiency, and electing Democratic leaders was regularly equivalated with reducing hunger; however, users deploying this frame could simultaneously show support for Republican leaders while advocating for bolstered support for vulnerable families, as with the following tweet:

@realDonaldTrump You did get cheated Mr. President, but we, the people that believe in you, need the relief bill! Please vote yes - my kids are hungry, and we are going to get thrown out! I survived Covid like you. You did a great thing with warp speed now please do the same with the 908b relief bill. Help us! (December 2020)

In sum, the insufficiency frame highlights how citizens in this sample deployed hunger to draw attention to the inadequacy of state support for hungry children and families during the pandemic and advocate for bolstered investments in food provisioning and poverty alleviation. This frame facilitated diagnostic statements that signaled awareness of the systemic roots of hunger but were less common at the prognostic level, within calls to action themselves. As almost all of the above tweets illustrate, children figured centrally in these moralized calls, adding urgency to their positions due to children’s presumed vulnerability, innocence, with it, deservingness (Fischer 2017, p. 26).

The unfairness of pandemic inequities

Approximately another one-third of all tweets (335) in this sample were centered around the frame of unfairness. Hunger was drawn on in this frame to express concern over rising economic inequality resulting from the pandemic as well as the unfairness of political actions or structures in place during this period that perpetuated it. The unfairness frame was used to express outrage at flagrant displays of privilege by state officials and elites or to critique state expenditures or priorities on seemingly frivolous policy items, arguing that those priorities were morally disgraceful ‘while children are left hungry.’ This frame’s focus on unfairness lends itself well to ad hominem critiques, so many tweets in this frame included personal attacks.

Donald Trump’s lavish meals and golfing activities were regular points of critique within this frame, as with this user who tweeted:

@anon I cried tonight while watching the news. So many people in food lines, kids going hungry, evictions looming, covid killing record numbers. All because of Trump and the GOP. And Trump was golfing today at Mara Lago. He doesn’t care. (December 2020)

Another common point of critical comparison was around Republican representatives’ pro-life stances or support for pro-life bills and initiatives. Below, one user responded to congressman Ralph Norman’s tweet announcing that he introduced a House Resolution recognizing January 22, 2021, as National Sanctity of Life Day. In this tweet, the user expressed frustration that the congressman’s energies were focused on a pro-life day of recognition rather than tackling hunger and other social problems:

@RepRalphNorman Pathetic! Over 400,000 Americans have died of COVID-19. American children are going to bed hungry. Families are becoming homeless. And this is what you’re proud of?? (Woman facepalming emoji) (Face with rolling eyes emoji) (Unamused face emoji). (January 2021)

Multiple users similarly commented on the hypocrisy of pro-life stances when advocated alongside support for policies that fail to care for children once they are born. Here, one user responded to a tweet by South Dakota’s Governor Kristi Noem stating that she introduced a bill banning abortions in her state:

Have you begun adopting these unwanted kids? Or created legislation to raise, house and feed these children? Yes, they are God’s, but we have a separation of church and state in this country. With unemployment, kids going hungry, and Covid, one would think you’d be busy! (January 2021)

Nancy Pelosi, the Democratic Speaker of the House of Representatives, also faced common criticism for her role in focusing Congressional attention towards particular aims (such as impeaching Donald Trump) at the expense of others (i.e., passing a stimulus bill), as exemplified by the following two tweets:

I get it, accountability. Ya know what I also get? Kids are still hungry. People are still being shot. Addicts still can’t get treatment. Covid is still spreading and killing. People still don’t have jobs. People are still losing their homes. Start passing some sh-t @SpeakerPelosi #waytooearly. (January 2021)

@SpeakerPelosi Maybe we should focus on the stimulus. COVID actions, small businesses, hungry families & children, drug addiction, homelessness, mental health issues, elder care...is that enough to take your focus off someone who is already gone? (January 2021)

Other common topics of critique were the concentrations of state funds and attention on recounting the presidential election and confirming Judge Amy Coney Barrett:

Covid is ravishing the country. People are losing their homes. Kids are going hungry. And what does our leader do? He spends all his time & money on ridiculous recounts and lawsuits, selfish bastard. And the GOP, oh the f–ing GOP.... they’re ten times worse. It’s sickening. (November 2020)

Irresponsible and cowardly Republicans have let Trump block Covid relief. Help is needed for the one in three families with kids experiencing food insecurity. Their only goal is to confirm Judge Barrett to kill your healthcare. They don’t care about you. They’re redundant. Vote them out. (November 2020)

While disparate in their topics, what unites tweets in this frame is their similar tendency to point to unacceptable government priorities that users argued should not come before hunger on representatives’ agendas. As with the insufficiency frame, tweets in the unfairness frame centered hungry children in their calls and placed hunger alongside other social problems that users felt the state should prioritize. Tweets in this frame, however, rarely go beyond these lists to make prognostic assertions about what proper attention hunger alleviation should look like.

The misdirection of state responses to the pandemic

The last frame characterizing this discourse is misdirection. Within the misdirection frame, Twitter users drew on rising hunger during the pandemic to highlight the adverse social and economic effects of lockdowns and reinforce broader conservative anti-lockdown sentiments. Twitter users deployed this frame to argue that public health restrictions on businesses and social activities were perpetuating, exacerbating, or ignoring the more pressing issue of hunger (in the vein that ‘the cure should not be worse than the disease’). State spending and guidelines related to public health measures preventing the spread of disease were therefore presented as misdirected, and proponents targeted their claims to advocate instead for bolstering resources or attention on alleviating hunger. This frame is significantly smaller than the other two frames but is still substantial, making up about 10% of all tweets (80). The three tweets below are reflective of sentiments in this frame:

@JoeBiden @SpeakerPelosi The American ppl are not just dying of covid they’re dying because no money is coming in. Kids hungry, jobs not calling, so what’s the next step killing themselves because they can’t take it anymore? We must take action (Nov 2020)

@GovMikeDeWine Ages 0–70 have a 99 percent survival rate. The survival rate is nearly 95% over 70. Kids need school and sports. Businesses can’t survive. Abuse, hunger, depression...the list goes on and on. The risk of shutting down far outweighs the risk of Covid. If you are at risk or afraid, stay home. (November 2020)

@teachersassociation @JoeBiden @KamalaHarris @teachcardona @GovernorVA A teacher is more likely to die in a car accident than of Covid once they’re vaccinated. Yet that’s too much of a risk for them? Yet again, unions are pushing 100% of the risk (of dropping out of school, hunger, depression, no escape from a difficult home) onto children. (January 2021)

Importantly, COVID deniability is a spectrum, and some Twitter users deploying the misdirection frame did not explicitly deny the severity of COVID-19’s health impact but instead simply wanted more attention paid to the social effects of lockdowns, especially those related to school closures. This is exemplified by the user below who responded to two Governors’ proposal for a two-week lockdown in November:

@OregonGovBrown @GovMLG Your answers here un-employ people. Yes, having Covid is bad, but unemployed & hungry & uneducated as kids drop out of crappy zoom school is far worse. The cost of closed schools and shut businesses is exponentially higher than Covid’s spread. But you can’t see that. Fail. (November 2020)

Some tweets in this frame also reflected racial tensions and reproduced racist sentiments reflective of “America First” policies – those grounded in nationalist notions that ‘we should take care of our own’ before ‘Others.’ Notably, these sentiments were directed internationally rather than domestically. They were raised mainly in reference to international aid funding embedded in the COVID relief bill, as is exemplified by the user below who posted a screenshot of hunger statistics in Missouri while tweeting at Governor Mike Parson saying:

@GovParsonMO Awesome. Our country is collapsing, and you pass the buck. Over one in seven children are suffering from hunger (these stats are pre-COVID) & you brag about sending food to Brazil… Clown. (November 2020)

Likewise, another user tweeted the following at eight journalists and media accounts alongside an article from The Hill critiquing the COVID relief bill: “‘Hungry children’ my ass. $86 million for assistance to Cambodia, $135 million to Burma, $130 million to Nepal, $453 million to Ukraine, $700 million to Sudan” (December 2020).

Tweets in this vein, such as the two above, draw on hunger to critique international aid funding within the COVID stimulus package and imply that while the package is framed as feeding hungry U.S. children, it is actually directed at funding overseas projects. Not all frames in this vein were used to reject the stimulus bill entirely, however. The user below, for example, critiqued international aid while expressing outrage at the reduced direct payments encompassed in the bill: “with all that money going to foreign countries, they have the gall to toss us this pitiful amount of funds! WTH! The money will be immediately injected back into the economy and that helps everyone! Demons!” The user then tweeted the following in response to another user normalizing foreign aid:

I understand, but children are hungry and homeless here as well. Also, a lot of countries had supplemental incomes during COVID whereas we had ONE. If I knew that that money went to the masses instead of padding pockets, I’d feel differently. Children always number one. (December 2020)

Discussion and conclusions

How have crisis conditions produced from the COVID-19 pandemic shaped societal narratives about hunger? Evidence from Twitter reinforces that hunger has been a subject of urgent moral concern during the pandemic and that the state has figured prominently in Twitter users’ calls to action to address hunger. Strikingly, the state was by far the dominant means by which Twitter users conceived of social change around hunger during this period of the pandemic crisis. The centrality of governments and government representatives in users’ frames is remarkable in that it suggests that people saw the state as central to hunger alleviation, particularly during a period of social crisis and political uncertainty. This is striking given broader neoliberal cultural and institutional shifts occurring across the Global North since the 1980s that locate social change predominately within the civil society sector and individual consumer citizens (Dickinson 2019; Guthman 2008; Johnston 2008; Riches 2018). At the same time, public reliance on state investments to alleviate hunger is not equivalent to advocations that those investments address structural inequalities at the heart of food insecurity, nor to recognitions of the right to adequate food (Anderson 2013; Chilton and Rose 2009). In fact, food insecurity scholars emphasize that the public’s “collective sense of what social change is possible” is limited when they rely on government nutrition programs to address hunger, since these programs generally do little to address the stagnating wages, un- and underemployment, housing instability, and legacies of racism and colonialism that undergird food insecurity (Fischer 2017, p. 4; see also Dickinson 2019; Poppendieck 2013; Power 1999). Some tweets in this sample acknowledge these connections, but they are a minority. Likewise, calling on the state to step up its commitment to food assistance without explicitly recognizing adequate food as a human right protected by ICESCR risks reinforcing a fragile, piece-meal commitment to food insecurity with little accountability (Anderson 2020; Bellows 2020; Riches 2020). Indeed, not a single tweet in this sample referenced the right to food nor framed food as a human right.

Evidence presented in this paper also underscores the variability with which hunger is deployed to justify contradictory political ends, even in a global health crisis. This paper identifies three frames through which hunger operates in this discourse. The first frame highlights the inadequacy of existing government commitments to support hungry families during the pandemic and encourages governments or government representatives to do more to bolster that support. The second frame expresses concern over rising economic inequality, and with it, hunger occurring over the pandemic and the unfairness of political actions, government policies, or social structures that perpetuate them. Hunger is used in the third frame to draw attention to the adverse social and economic effects of lockdowns and argue that state-directed lockdown measures aimed at preventing the spread of disease are misdirected.

The implications of these findings can be considered in theoretical and practical terms. Theoretically, they contribute to understanding how culture and morality operate in “unsettled times” (Swidler 1986). Swidler argued that culture more obviously influences action in “unsettled times” by opening up possibilities for constructing new “strategies of action.” Determining precisely how the pandemic shaped public understandings of hunger is difficult without a comparative analysis of the pandemic and pre-pandemic periods; however, pairing the paper’s findings alongside existing literature offers opportunities for informed speculation. Doing so provides only partial support for Swidler’s argument. On the one hand, elements of each frame bear notable similarities to pre-pandemic hunger narratives. For instance, aspects of the unfairness frame resemble the public discourse around hunger described by Poppendieck (2013) during the Great Depression. Whether this similarity represents the endurance of this frame or its particularity to crisis conditions is difficult to disentangle, however, because the Great Depression was also a crisis. Still, the inadequacy and misdirection frames also echo more longstanding discursive frames, at least in a generalized sense: the first by progressives to bolster investments in the welfare state, and the second by conservatives to mitigate the state’s regulatory impact on public life. These similarities – especially those in the latter two frames – suggest that crisis conditions appear to reinforce, rather than shift, people’s longstanding ideological commitments. However, I suggest that these ideological commitments are reinforced by reconfiguring existing cultural tools (i.e., hunger alleviation) in new ways.

What I suggest may be particular in these frames, and may be rooted in the pandemic crisis, is the salience of hunger as a social problem and the centrality of state spending to alleviate it. As Poppendieck (2013) argues, hunger has an exceptional capacity to mobilize action due to its emotional valence and seemingly concrete (if misguided) ability to be solved. This paper’s findings suggest that these meanings may be especially relevant during times of crisis. Within the crisis conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic, hungry families acted as a visceral rallying point around which to advocate for more significant public investments in poverty alleviation. Notably, these calls came from people across the political spectrum, including conservative groups who are not generally known for supporting state spending towards this end. New strategies for action therefore emerged in the ways that different groups deployed hunger to advocate for their respective political goals. In this case, the result was that longstanding cultural narratives about hunger were used toward very different, and in some cases, contradictory political ends.

Perrin (2006) argues, these cultural tools make up an important aspect of democratic citizenship. Therefore, it is useful to consider the findings’ implications for whether the COVID-19 crisis has created conditions that provoke a shared democratic imagination in ways that could lead to substantive changes in food and poverty alleviation. Does active engagement with hunger discourse necessarily lead to a shared political vision for change? While this paper’s findings may suggest the potential for a situationally-specific common ground around government investments in food and poverty alleviation efforts, overall, it reinforces the variability in public support for hunger provisioning and its vulnerability to political manipulation. On the one hand, the salience of hunger during this period suggests that the pandemic may have shaken the public out of a sense of moral ease or comfort with existing food insecurity efforts and revealed them as ineffectual. Heightened awareness of hunger during the pandemic may have created opportunities to leverage temporary support for hunger investments during a time of crisis within a facet of society that is otherwise usually more unsympathetic to them. This holds the potential to lead to support for more intensive government investments in poverty alleviation, such as through direct cash assistance, which would be a significant shift considering the rollbacks to that assistance that have been occurring over the past 30 years. There is some support for this possibility given the reasonably strong support for President Biden’s 2021 COVID relief and infrastructure bills that included substantial direct payments to households and significant improvements to the state social safety net, and investments in food assistance. On the other hand, the misdirection frame shows how hunger can be used to further goals that are unrelated and even at odds with food justice efforts and be deployed by drawing on longstanding racist and nationalist sentiments of deservingness. These findings largely support the existing hunger literature offering skepticism of the impact of public awareness around hunger on political change, even during times of crisis (Dickinson 2019; Jarosz 2015; Poppendieck 2013).

Future studies could productively investigate these possibilities by systematically considering the relationship between public opinion and state policies around hunger longitudinally. Tracking long-term shifts in hunger discourse on Twitter or other media and comparing them to policy shifts (such as in Flores’ 2017 study) would help further establish the relationships between policy and public opinion in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis. In addition, questions remain about the extent to which these findings are a product of the specific context of Twitter, and generational differences in understanding food insecurity along with it. As noted, Twitter users do not mirror the general population, and the perspectives presented in this paper likely reflect those of younger generations overall than is typical of the general population. It would be useful to compare this paper’s findings with survey data from this period to better understand its generalizability beyond Twitter. More specifically, there is reason to believe that this paper’s findings may partly reflect generational shifts in the framing of food insecurity over time. Faith-based organizations have played an important role in food charity historically, where volunteer-based pantries and soup kitchens served as a significant touchstone for public support for civil society responses to food insecurity. It is important for future research to understand how dominant framings of food insecurity may shift as participation in faith-based organizations (and faith-based food charities along with them) wanes among younger generations. Do younger generations turn more easily to the state than private individuals or food charities because they believe in the power of governments in supporting vulnerable Americans, or because they do not hold the same faith-based frame for understanding community support and well-being? These are important questions for future research.

Notes

In 2006, USDA replaced the term “hunger” with “very low food insecurity” and now distinguishes between food insecurity as the social and economic conditions that reflect insufficient material resources to access adequate food, and hunger as the individual, physiological condition arising from a food insecure status (USDA 2022). It is important to note that such a shift also reflects the purpose of depoliticizing “hunger” (see Berg 2008). I use the term hunger chiefly in this paper to draw attention to its politicization, as part of a broader phenomenon of “hunger politics” discussed in detail in the paper, and because that is how it is largely framed by lay persons within the online discourse itself.

References

Al Zidjaly, N., E. Al Moqbali, and A. Al Hinai. 2020. Food, activism, and Chips Oman on Twitter. In Identity and Ideology in Digital Food Discourse: Social Media Interactions Across Cultural Contexts, eds. A. Tovares, and C. Gordon, 197–224. London, UK: Bloomsbury.

Anderson, M. 2013. Beyond food security to realizing food rights in the US. Journal of Rural Studies 29: 113–122.

Anderson, M. 2020. Make federal food assistance rights-based. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 35 (4): 439–441.

Barnes, C. 2017. Mediating good food and moments of possibility with Jamie Oliver: Problematising celebrity chefs as talking labels. Geoforum 84: 169–178.

Bauer, L. 2020. Hungry at Thanksgiving: A fall 2020 update on food insecurity in the U.S. Brookings, Washington, D.C., Up-Front Blog, November 23. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/11/23/hungry-at-thanksgiving-a-fall-2020-update-on-food-insecurity-in-the-u-s/. Accessed 8 January 2022.

Bellows, A. 2020. A systems-based human rights approach to a national food plan in the USA. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 35 (4): 442–444.

Benford, R., and D. Snow. 2000. Framing processes and social movement: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology 26: 611–639.

Berg, J. 2008. All you can eat: How hungry is America? New York, NY: Seven Stories Press.

Bitler, M., H. Hoynes, and D. Whitmore Schanzenbach. 2020. The social safety net in the wake of Covid-19. Nber Working Paper Series, Working Paper 27796, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w27796/w27796.pdf Accessed 8 January 2022.

Carney, M. A. 2015. The unending hunger: Tracing women and food insecurity across borders. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Castells, M. 2015. Networks of outrage and hope: Social movements in the internet age. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Chilton, M., and D. Rose. 2009. A rights-based approach to food insecurity in the United States. American Journal of Public Health 99 (7): 1203–1211.

Coleman-Jensen, A., M. P. Rabbitt, C. A. Gregory, and A. Singh. 2021. Household food security in the United States in 2020. USDA-ERS Economic Research Report 298. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/102076/err-298.pdf?v=5696.9. Accessed 8 January 2022.

Collins, J., and V. Mayer. 2010. Both hands tied: Welfare reform and the race to the bottom in the low-wage labor market. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Dickinson, M. 2019. Feeding the crisis: Care and abandonment in America’s food safety net. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Dickinson, M. 2020. Food frights: COVID-19 and the specter of hunger. Agriculture and Human Values 37: 589–590.

Entman, R. 1993. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication 43 (4): 51–58.

Feeding America. 2020. The food bank response to COVID, by the numbers. https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-blog/food-bank-response-covid-numbers. Accessed 22 August 2021.

Fisher, A. 2017. Big hunger: The unholy alliance between corporate America and anti-hunger groups. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

Flores, R. 2017. Do anti-immigrant laws shape public sentiment? A study of Arizona’s SB 1070 using Twitter data. American Journal of Sociology 123 (2): 333–384.

Guthman, J. 2008. Neoliberalism and the making of food politics in California. Geoforum 39 (3): 1171–1183.

Guthman, J., and S. Brown. 2016. I will never eat another strawberry again: the biopolitics of consumer-citizenship in the fight against methyl iodide in California. Agriculture and Human Values 33 (3): 575–585.

Huddart Kennedy, E., J. Parkins, and J. Johnston. 2018. Food activists, consumer strategies, and the democratic imagination: Insights from eat-local movements. Journal of Consumer Culture 18 (1): 149–168.

Jarosz, L. 2015. Contesting hunger discourses. In The international handbook of political ecology, ed. R. L. Bryant, 305–317. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Johnston, J. 2008. The citizen-consumer hybrid: Ideological tensions and the case of Whole Foods Market. Theory and Society 37 (3): 229–270.

Johnston, J., and M. Szabo. 2011. Reflexivity and the Whole Foods Market consumer: The lived experience of shopping for change. Agriculture and Human Values 28 (3): 303–319.

Kotz, N. 1969. Let them eat promises; the politics of hunger in America. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Levenstein, H. 1993. Paradox of plenty: A social history of eating in modern America. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Luft, A. 2020. Theorizing moral cognition: Culture in action, situations, and relationships. Socius 6: 1–15.

Mann, A. 2018. Hashtag activism and the right to food in Australia. In Digital food activism, eds. T. Schneider, K. Eli, C. Dolan, and S. Ulijaszek, 168–184. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge.

Markham, A. 2012. Fabrication and ethical practice. Qualitative inquiry in ambiguous internet contexts. Information Communication & Society 15 (3): 334–353.

Maskovsky, J., and J. Goode. 2001. Introduction. In New poverty studies: The ethnography of power, politics, and impoverished people in the United States, eds. J. Goode, and J. Maskovsky, 1–36. New York, NY: NYU Press.

Morales, D., S. Xiaodan, A. Morales, and T. Fox Beltran. 2021. Racial/ethnic disparities in household food insecurity during the covid-19 pandemic: a nationally representative study. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 8 (5): 1300–1314.

Morozov, E. 2009. Iran: Downside to the “Twitter revolution. Dissent 56 (4): 10–14. ” ).

Perrin, A. 2006. Citizen speak: The democratic imagination in American life. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Poppendieck, J. 2013. Want amid plenty: From hunger to inequality. In Food and culture: A reader, eds. C. Counihan, and P. Van Esterik, 563–571. New York, NY: Routledge.

Power, E. 1999. Combining social justice and sustainability for food security. In For hunger-proof cities: Sustainable urban food systems, ed. Mustafa Koc, 30–37. Ottawa, ON: International Development Research Centre.

Riches, G. 2018. Food bank nations: Poverty, corporate charity and the right to food. London, UK: Routledge.

Riches, G. 2020. The right to food, why US ratification matters. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 35 (4): 449–452.

Roff, R. J. 2007. Shopping for change? Neoliberalizing activism and the limits to eating non-GMO. Agriculture and Human Values 24 (4): 511–522.

Rousseau, S. 2012. Food and social media: You are what you tweet. Lanham, MD: Rowman Altamira.

Scarborough, W. J. 2018. Feminist Twitter and gender attitudes: Opportunities and limitations to using Twitter in the study of public opinion. Socius 4: 1–16.

Schanzenbach, D., and A. Pitts. 2020. How much has food insecurity risen? Evidence from the census household pulse survey. Northwestern Institute for Policy Research. https://www.ipr.northwestern.edu/documents/reports/ipr-rapid-research-reports-pulse-hh-data-10-june-2020.pdf Accessed 22 August 2021.

Schneider, T., K. Eli, C. Dolan, and S. Ulijaszek, eds. 2018. Digital food activism. New York, NY: Routledge.

Snow, D., and R. Benford. 1988. Ideology, frame resonance, and participant mobilization. International Social Movement Research 1 (1): 197–217.

Sutton, D., N. Naguib, L. Vournelis, and M. Dickinson. 2013. Food and contemporary protest movements. Food Culture & Society 16 (3): 345–366.

Swidler, A. 1986. Culture in action: Symbols and strategies. American Sociological Review 51: 273–286.

Swidler, A. 2001. Talk of love: How culture matters. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Tovares, A., and C. Gordon, eds. 2020. Identity and ideology in digital food discourse: Social media interactions across cultural contexts. New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

Twitter. 2021. Q1 2021 letter to shareholders. https://s22.q4cdn.com/826641620/files/doc_financials/2021/q1/Q1’21-Shareholder-Letter.pdf Accessed 1 August 2021.

USDA. 2021. SNAP data tables. https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap Accessed 22 August 2021.

USDA. 2022. Definitions of food security. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security.aspx#CNSTAT Accessed 19 May 2022.

Washington Post. 2020. Twitter sees record number of users during pandemic, but advertising sales slow. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/twitter-sees-record-number-of-users-during-pandemic-but-advertising-sales-slow/2020/04/30/747ef0fe-8ad8-11ea-9dfd-990f9dcc71fc_story.html Accessed 25 August 2021.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Anelyse Weiler and Sarah Elton for their valuable feedback on multiple drafts of this manuscript, as well as to Yousaf Shah for his technical support through the data mining process. I would also like to thank Dwayne Smith who provided a complimentary social media data mining workshop to members of the Sociologists for Women in Society, and which provided the impetus and foundational know-how for the data mining project. Versions of this paper were also presented at the American Sociology Association Annual Meeting as well as the Joint Annual Meetings of the Association for the Study of Food and Society and the Agriculture, Food, and Human Values Society, and benefitted from the feedback received at those venues. I would also like to thank Matthew R. Sanderson and the three anonymous reviewers for pushing the paper’s analytical direction forward and helping see it to completion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oleschuk, M. Who should feed hungry families during crisis? Moral claims about hunger on Twitter during the COVID-19 pandemic. Agric Hum Values 39, 1437–1449 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-022-10333-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-022-10333-2