Abstract

Rwanda is often depicted as a success story by policy makers when it comes to issues of gender. In this paper, we show how the problem of gendered inequality in agriculture nevertheless is both marginalized and instrumentalized in Rwanda’s agriculture policy. Our in-depth analysis of 12 national policies is informed by Bacchi’s What’s the problem represented to be? approach. It attests that gendered inequality is largely left unproblematized as well as reduced to a problem of women’s low agricultural productivity. The policy focuses on framing the symptoms and effects of gendered inequality and turns gender mainstreaming into an instrument for national economic growth. We argue that by insufficiently addressing the socio-political underlying causes of gendered inequality, Rwanda’s agriculture policy risks reproducing and exacerbating inequalities by reinforcing dominant gender relations and constructing women farmers as problematic and men as normative farmers. We call for the policy to approach gendered inequality in alternative ways. Drawing on perspectives in feminist political ecology, we discuss how such alternatives could allow policy to more profoundly challenge underlying structural constraints such as unequal gender relations of power, gender norms, and gender divisions of work. This would shift policy’s problematizing lens from economic growth to social justice, and from women’s shortcomings and disadvantages in agriculture to the practices and relations that perpetuate inequality. In the long term, this could lead to transformed gender norms and power relations, and a more just and equal future beyond what the dominant agricultural development discourse currently permits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gendered inequality has been considered a crucial issue in agricultural and development governance ever since the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing 1995. It is often addressed through the governance strategy of gender mainstreaming.Footnote 1 In agricultural institutions, gender mainstreaming has largely implied integrating more women farmers into existing agricultural projects and programs that are framed within gender-biased neoliberal ideas of efficiency, competition, and market-led development (Arora-Jonsson and Leder 2021; Gengenbach et al. 2018). Accordingly, debates are ongoing about the problems of and solutions to gendered inequalities in agriculture (Arora-Jonsson and Leder 2021; McDougall et al. 2021), and in development more generally (Chant and Sweetman 2012; Parpart 2014; Cornwall and Edwards 2010; Moser 1989).

Indeed, discussions about the meanings and problems of gendered inequalities, and the strategies by which to eradicate them, occur in contested processes of interpretation and knowledge creation, where some forms of knowledge gain prominence over others. Such discursive struggles determine what assumptions about gender and inequality emerge as “true,” relevant, and legitimate for policy action. In this paper, we show and argue that discourse and its effects on how problems and people are constructed in policy are important to study and understand, as has been argued elsewhere (e.g. Davila 2020; Gottschlich and Bellina 2017; Schneider 2015).

Feminists continue to reveal and challenge the biases and effects of prevailing conceptualizations of gender in dominant approaches to development (Gerard 2019; Harcourt 2016; Jackson and Pearson 2005) and agriculture (Ossome and Naidu 2021; Razavi 2009; Sachs 2019). In the current neoliberal development paradigm, critics argue that development theory and practice should (re-)connect with feminist theories of care, justice, and emancipation to achieve substantive and sustainable social change (Cornwall and Rivas 2015; Nyambura 2015; Wallace 2020). In contemporary African agricultural restructuring and transition, known as the New Green Revolution for Africa (GR4A), scholars highlight and challenge the gendered, unequal outcomes of interventions for, among others, agricultural mechanization (Daum et al. 2021; Kansanga et al. 2019), new and improved seeds and varieties (Addison and Schnurr 2016; Bergman Lodin 2012), new breeds (Wangui 2008), irrigated agriculture (Nation 2010), inorganic fertilizer and pesticide use (Christie et al. 2015; Luna 2020), market integration (Quisumbing et al. 2015; Tavenner and Crane 2018) and commercialization (Gengenbach 2020). Recent studies of national agriculture policy in Africa consider its limitations with regard to advancing equality. They indicate that gender mainstreaming is limited within and across governance levels (Ampaire et al. 2020; Drucza et al. 2020; Tsige et al. 2020) and that structural inequalities are insufficiently addressed upon implementation (Ampaire et al. 2020), which turns gendered inequality into an apolitical and technical problem (Acosta et al. 2019). The analyses highlight important weaknesses in interpretation and implementation of gender mainstreaming in agriculture policy and practice. However, the discourses in national African agriculture policy that underpin and legitimize how problems of gendered inequalities are formulated and addressed have hitherto not been extensively examined.

We contribute such an examination by drawing on Bacchi’s (2009) What’s the problem represented to be? (WPR) approach to analyze if and how gendered inequality is problematized in Rwanda’s agriculture policy documents. According to Bacchi (2009), problems are not given, but constructed through problematization and often created in such a way that a manageable solution can be found. We thus study how the policies construct the problems they seek to address (Allan et al. 2010), which means analyzing what discourses and assumptions they rely upon to appear legitimate for intervention. Moreover, problem formulations shape, or limit, what course of action and behavior the policy’s target population can pursue. For this, we use the concept of gendering effects (Bacchi 2017) to analyze how women and men farmers are constructed in different and potentially unequalizing ways through the problem formulations. Finally, the WPR approach also serves to challenge existing problem formulations and to reflect on how they could be understood and formulated differently.

We have chosen Rwanda as our case of analysis, which is internationally known for its achievements in gender-equal parliamentary representation, health, and education (WEF 2019). These achievements have influenced women’s autonomy and respect in the family and community to some extent (Burnet 2011), yet research shows that the picture needs to be nuanced (Ansoms and Holvoet 2008; Berry 2015; Debusscher and Ansoms 2013). Similarly, Rwanda is widely celebrated as a model example of GR4A implementation (Nyenyezi Bisoka and Ansoms 2020a). The country pushes a policy agenda of agrarian and structural transition based on economic growth, and it aims to reach high-income country status by 2050 (GoR 2020). Agriculture is Rwanda’s largest sector in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) and employment (WB 2019). Increased agricultural productivity and efficiency through modernization and professionalization of farming and farmers is represented as key to rural poverty reduction and national economic growth.Footnote 2 These points combined make Rwanda’s agriculture policy an interesting and relevant case in which to analyze how the Government of Rwanda (GoR) problematizes gendered inequality in agriculture.

In this paper, we explore how the problematization of gendered inequality in Rwanda’s agriculture is underpinned and legitimized by specific discourses about gender, agriculture, and development, and how this constructs women and men farmers in specific ways. By questioning the policy’s claims to facts and knowledge, we also open up for alternative ways of problematizing. Our analysis is guided by four research questions, adapted from Bacchi and Goodwin (2016):

-

1.

How is gendered inequality problematized in Rwanda’s agriculture policy?

-

2.

What dominant discourses and assumptions underpin the problematization?

-

3.

How are women and men farmers constructed through the problematization?

-

4.

How can gendered inequality be problematized differently?

Following an overview of the scientific knowledge on gender relations in Rwanda’s agriculture, we introduce the study’s methodological approach. Next, we present our analysis of how gendered inequality is problematized in the agriculture policy, including its underlying discourses, assumptions, and gendering effects. We then draw on perspectives within feminist political ecology (FPE) to discuss alternative, more gender transformative ways for the agriculture policy to construct the problem of gendered inequality.

Gender and agriculture in Rwanda

Rwanda’s development strategy aims to continue and intensify socio-economic development and the agriculture sector forms a cornerstone of this process (GoR 2020). Agriculture is described as a crucial engine for past and future economic growth, poverty reduction, and food security. At the same time, the GoR claims agriculture to remain insufficiently productive and highlights its underutilized economic potential. Arguments are therefore made for a sector-wide transformation of smallholder and subsistence based farming to a market-driven and modernized agriculture sector (GoR 2020). To further legitimize this agricultural transformation, the GoR draws on a narrative that claims agricultural yields to be insufficient in relation to land availability and the growth and density of the population. The GoR also assumes correlations between agricultural productivity and farmers’ increased incomes, and between increased incomes and poverty reduction, food security, and economic growth. Increased agricultural productivityFootnote 3 is thereby represented as a key to successful development. In the strategy for agricultural development, the GoR proposes gender mainstreaming as a way to address and prevent gendered inequalities (GoR 2018; 2019).

Interventions for increased agricultural productivity in Rwanda have allegedly improved the lives of many Rwandans (Meador and O’Brien 2019; NISR 2012). Yet, the picture is contested (Ansoms et al. 2017; Okito 2019). Mounting evidence in the scientific literature indicates that many agricultural interventions exacerbate patterns of differential access to and control of resources, which increases the vulnerability of already marginalized populations (see e.g. Ansoms 2008; Ansoms and Cioffo 2016; Cioffo et al. 2016; Clay and Zimmerer 2020; Huggins 2017; Nyenyezi Bisoka et al. 2020; Wise 2020). Some outcomes of the interventions are distinctly gendered. Examples include male capture, i.e. men’s appropriation of crops with increased economic value (Clay 2017; Ingabire et al. 2018), women’s unequal participation in rural labor markets (Bigler et al. 2017; Illien et al. 2021) and farming cooperatives (Treidl 2018), and negative effects on women farmers’ wellbeing and workload (Ansoms and Holvoet 2008; Bigler et al. 2019; Clay 2017; Debusscher and Ansoms 2013). Such outcomes are often explained by, among others, unequal gender norms, gendered division of work, and institutional and structural constraints.

The reviewed literature challenges the narrative of a successful on-going agricultural transformation in Rwanda, and confirms gendered and unequal outcomes of its policy implementation. While the studies bring insights to the limits and gendered nature of Rwanda’s model for agricultural transformation, they mainly analyze the gendered effects of policy upon implementation. Women and men’s characteristics and relations are thereby assumed as pre-givens that are not questioned. Less attention is paid to how policy, in its very formulation, construct and condition the characteristics, actions, and roles that become possible for women and men farmers to adopt. Studies with such constitutive approach to policy, as this one, bring insights about the discursive effects of policy, thus contributing important complementary knowledge to existing scholarship. A few studies, however, recently brought this approach to Rwanda’s agricultural context. Ansoms and Cioffo (2016) study how dominant discourses on agriculture and citizenship construct rural citizens in particular ways in Rwanda’s state-led reorganization of rural space and production. Nyenyezi Bisoka and Ansoms (2020a) analyze how Rwandan farmers resist the productivist agricultural norm in the GR4A and renegotiate their agency as well as the norm itself. These studies show how dominant agricultural discourses construct, and are reconstructed by, farming and farmers. They shed light on the relevance of analyzing and challenging the discourses that policy (re)produce, and of assessing their effects on people. Our analysis builds on these insights to understand the distinctly gendered discursive effects of Rwanda’s agriculture policy.

Methodology

Our study starts with an understanding of meaning as constructed in and through language. The meaning of things and phenomena evolves through discourses, defined as socially produced systems of knowledge, which limit and enable what is possible to think, speak, or write (McHoul and Grace 1993, cited in Bacchi and Goodwin 2016, p. 35). Moreover, meaning making takes place in processes of discursive struggles that are characterized by unequal relations of power. This causes some forms of knowledge to acquire precedence over others, thereby emerging as more legitimate, or more “true.” However, what is considered as true and legitimate knowledge is never fixed or stable, since discourses change across time and space (Weedon 1996). Therefore, the meaning of objects (things) and subjects (people) are constantly made and remade, or constituted, in and through meaning making processes, or discursive practices (Allan et al. 2010; Bacchi and Goodwin 2016).

Policy as gendering practice

With this constitutive approach, we understand policy to discursively produce and construct the problems, subjects, and objects they seek to address (Allan et al. 2010). Such discursive production occurs in ways that may produce and reproduce gender disparities. We thus understand policy as a gendering practice where the social categories “woman” and “man” are constructed through language and meaning making in policy in specific ways and in a relation of inequality (Bacchi 2017). What women and men can think, do, be, and become – their subject positions – is shaped in and by the meaning and knowledge produced by policy. This refers to the gendering effects of policy. The analytical focus thereby becomes how policy produces things or people, instead of the effects of policy on them. Attention is given to how the categories of women and men are done (constructed) through specific discursive practices in policy texts (Bacchi 2017, p. 21). This approach to analyzing policy enables an examination of how phenomena, such as gendered inequality, become constructed as particular problems with effects on the different subject positions made (un)available to women and men. Because discourse is dynamic, such examination also opens up the possibility to understand and construct policy problems differently, based on alternative discourses and with other gendering effects (Bacchi 2012; Bacchi and Goodwin 2016). The task of this paper is to analyze the discursive practices that legitimize particular problem formulations of gendered inequality in Rwanda’s agriculture policy, to consider its gendering effects, and to reflect on alternative ways of problematizing gendered inequality. Next, we describe how this analysis was conducted.

Analytical framework and procedure

Our analysis follows the prompt by the What’s the problem represented to be? (WPR) approach to “work backwards” in policy documents, to “examine the ‘unexamined ways of thinking’ on which [the problematizations] rely, to put in question their underlying premises, and to insist on questioning their implications” (Bacchi and Goodwin 2016, p. 16). Our analytical goal is thus to challenge what may appear as “truths,” to make the politics in the policy visible, and to open up for alternative problem formulations foregrounded by a feminist vision of just and equal outcomes (ibid.).

The analysis consisted of an iterative process of individual and joint in-depth reading and re-reading of policy documents. Key analytical means encompassed memo writing, categorization, and grouping by hand and in NVivo, and discussions among the authors. In the initial phase, we explored the documents in terms of relevant themes, concepts, and ideas in relation to the first three research questions. A word count of terms directly or indirectly relating to gendered inequalities indicated the extent to which it was addressed in each of the documents. Through discussions and analytic memo writing, we identified and explored different problematizations related to gender and considered what knowledges and assumptions they were based on. We also discussed the large parts of the documents where gendered inequality was not considered, and paid particular attention to potential gender biases within those silences.

In the second phase, the identified themes and concepts were further analyzed and, by hand and in NVivo, grouped together under broader categories of problematizations. Some new material was identified and included for in-depth reading during this phase, which allowed for emergent ideas and insights to be tested, juxtaposed, confirmed, or revised.Footnote 4 In this phase, we also identified forms of knowledge and their underlying assumptions and sketched out how these were connected to problematizations of gendered inequality.

The WPR framework suggests that the discourses and assumptions that legitimize a particular problematization are identified and traced to understand their origins, pathways into policy, and their rationale in the specific policy context. For this reason, we also reviewed a broader set of national and international reports, strategies, and agreements by public authorities, donors, and organizations that were cited in, or otherwise related to, the analyzed documents. This helped us to follow discourses beyond the boundaries of Rwanda’s agriculture sector, which helped understanding Rwanda’s policy in the broader context of regional, continental, and global agricultural development.

In the final phase, we revisited and discussed analytic memos, thematic grouping, and categorizations. This led us to delineate how specific discourses and assumptions about gender, agriculture, and development operated in and across the documents to form one main problematization of gendered inequality. Following this, we also discussed how women and men farmers were constructed in specific ways through this problematization, and what implications such constructions could have for existing gender norms, relations, and structures in Rwanda’s agriculture.

Our reflection on alternative problematizations of gendered inequality was based on insights from the first three research questions and by revisiting feminist scholarship on agricultural development policy and practice, notably within the field of feminist political ecology (FPE). We engaged with relational and performative conceptualizations of gender and power in agrarian and otherwise socio-ecological contexts. This led to ideas and suggestions guided by gender transformative approaches (GTA) to agricultural development where an alternative policy increasingly and strategically would problematize the underlying causes of gendered inequality in agriculture, with the aim to achieve gender equality.

Analyzed material

The policy documents included for analysis encompassed national-level policies, strategies, implementation plans, and reports related to Rwanda’s agriculture. A selection of sub-sector documents was also included, such as strategies and plans for rice cultivation and irrigated agriculture. In addition to the requirement for online accessibility, the material was selected to cover a wide and representative range of the agriculture policy framework. In total, 12 documents were analyzed, comprising approximately 1330 pages. In addition, relevant strategy documents, reports, and policy briefs from national and international agricultural and development organizations, funders, and donors were reviewed, as were national policies of overarching character, agreements, and declarations related to agriculture at regional and continental level. A list of the analyzed and reviewed documents is provided in Annex 1.

Problematization of gendered inequality in Rwanda’s agriculture policy

Window dressing gendered inequality

Our first key insight points to a limited attention to gendered inequality as a problem in Rwanda’s agriculture policy. A word count shows that the term “gender” occurs between zero and 47 times in each of the 12 documents, excluding the Gender and Youth Mainstreaming Strategy (GYMS), which mentions “gender” 574 times. The 4th Strategic Plan for Agricultural Transformation (PSTA4) scores 47, but in all other documents, “gender” occurs fewer than five times. Similar patterns are observed regarding the terms “women” and “men,” although “women” occurs five to eight times more often than do “men.” Moreover, content related to gender is mostly confined to chapters towards the end of documents or to subsequent sections of chapters, often referred to as a “cross-cutting issue.” For example, in the National Agriculture Policy (NAP), gender, or rather women along with youth, receive attention in a sub-subsection under the last policy pillar named “Inclusive markets and off-farm opportunities” (p. 33 of 38). Similarly, the PSTA4 includes “gender and family” as a cross-cutting issue together with other themes such as “capacity development,” “nutrition-responsive agriculture,” “environment and climate change,” and “regional integration” (p. 70 of 97).

The overall peripheral placement of gender concerns is also reflected in numbers and tables, as finance for gender equality efforts seem under-prioritized. For instance, the PSTA4 dedicates 1.9% of its total 7-year budget (2018–2024) to gender mainstreaming activities. Cross-document comparison shows that the 7-year budget of the GYMS (2019–2025) is 36% of the size of the budget for the Agricultural Mechanization Strategy (AMS). Similarly, the GYMS budget is 17% of the size of the budget for the strategy for information and communications technology in agriculture (ICT4RAg), and 5% of that of the strategy for the Crop Intensification Program (CIP).

Because of the policy’s generally limited attention to and acknowledgement of gendered inequality as a problem, the GYMS emerges as the main space to tackle it. This overall isolation of gender considerations together with the fact that the issues of “gender” and “youth” are consistently considered in tandem, further presents gendered inequality as a side-lined problem among others and constructs the target populations (women and youth) as homogenous groups in need of particular intervention. For example, the GYMS includes mainstreaming strategies for both women and youth, and The National Agricultural Export Development Board’s strategic plan to increase agri-export revenues (NAEB) considers the two as thematic considerations along with “knowledge management,” “human capital development,” and “environmental sustainability” (p. 62 of 127). Our analysis suggests that this under-prioritization and marginalization compartmentalizes the problem of gendered inequality in agriculture and disintegrates it from the overarching agriculture policy framework. Gendered inequality is constructed as an add-on problem to key action areas such as farmers’ market integration, agricultural productivity, technology adoption, and innovation. We find that this reflects a limited and superficial understanding of how gender is integral to shaping the conditions and outcomes of these action areas, and in agrarian transitions in general. Notions of gender as a system of power relations that form specific norms and practices in agriculture (Nightingale 2011) remain silent.

Yet, we find this superficial understanding contradictive in light of an economic argument presented for taking gendered inequality seriously. The argument is elaborated in the GYMS and based on the “gender agricultural productivity gap:” the persistence of differences in agricultural productivity between farms managed by women and men. Because of its alleged hampering effect on economic growth, this gender gap becomes relevant within contexts dominated by the mainstream agricultural development discourse, such as Rwanda. Closing the gender productivity gap in Rwanda, the GYMS presents, could lead to a direct GDP increase of USD 418.6 million (or approx. 5% in 2013/2014Footnote 5) and lift 2.1 million Rwandans out of poverty (almost 33% of the country’s poor in 2013/2014) (UN Women et al. 2017). We will later question that the GoR concentrates its efforts for remedying gendered inequality in agriculture on closing this gap. However, in light of the GoR’s overall economic growth-driven approach to agricultural development, we interpret the contradiction between the policy’s limited recognition and integration of issues of gender, and the alleged economic benefit of closing the gender productivity gap, as window dressing concerns for gendered inequality. We would expect more and in-depth attention to gendered inequality throughout the documents to correspondingly reflect the benefits assumed from closing the gap.

Constructing women farmers as problematic

Our second key finding relates to the policy’s construction of women farmers as problematic – and men as normative farmers. This can be traced to the association of gendered inequality with low agricultural productivity as a limit to economic growth. Foregrounded by a vision of capitalist, neoliberal agricultural modernization, the parts of the policy related to gender are centered on women farmers and their purported low agricultural productivity. The vision and aims of the GYMS reflect this:

“The Vision is that there is increased and sustainable productivity in the agriculture sector for healthy and wealthy women, men and youth. The aim is for women and youth to have increased knowledge and access to services, to participate equally in all parts of the value chain, and to work in collaboration with men to improve their agricultural productivity and economic empowerment.“

- GYMS, p. 38.

The policy thus seeks to change, and thereby sees as a problem, women farmers’ low productivity by addressing their access to, decision-making, and participation in various agricultural resources and activities. In so doing, our analysis suggests that the policy problematizes the effects of gendered inequality rather than its causes, such as underlying structural inequalities and unequal power relations. Embedded in Rwanda’s vision of modernization and in line with the GR4A model, the agriculture policy draws on a gender-biased discourse of mainstream agricultural development to establish women’s low agricultural productivity as a legitimate problem for intervention. Specifically, we find that legitimacy is derived from reliance on knowledge and assumptions about women farmers as different from men with less desired agricultural practices, and from overgeneralizing evidence on the gender agricultural productivity gap in Rwanda.

Hierarchical divisions of gender and agriculture

First, we find that the policy constructs women and men as two different groups of farmers, each with fixed, homogenous characteristics. This is reflected in the frequent references to women as a proxy for “gender” and as a uniform group with specific needs, in statements such as “women in agriculture are more vulnerable to climate change and land degradation” (PSTA4, p. 25), and in proposals to develop “women-friendly tools in farming operations” (AMS, p. 45). It is also visible in statements claiming that “Compared to men, women have limited access to formal finance and are more likely to be financially excluded” (PSTA4, pp. 24–25). By comparison, men are likewise homogenously represented, but with contrasting features such as having access to formal finance, or as not vulnerable to climate change. In addition to the statements’ essentializing effects on what both women and men can be and do, assuming gender as static, binary, and comparative constructs a hierarchical division between the two categories. Given the national desire to maximize agricultural productivity, women’s agricultural practices and outputs are generally valued lower than men’s. The valuation of men’s farming over women’s is mainly established by a hierarchical division between subsistence farming (farming for household consumption) and market-based (modernized) agriculture, and the association of women with the first and men with the latter. Subsistence farmers, allegedly the “majority of Rwandan farmers”Footnote 6 (NAP, p. 26) and mostly women, are said to “…face a complex set of challenges that suppress yields below potential, such as limited access to finance, insurance, technology, skills, irrigation, mechanization, seeds, fertilizers, and other key inputs” (PSTA4, p. 23). Women – along with youth – are also explicitly problematized for their unsatisfying integration into the agriculture sector:

The agriculture sector currently fails to maximise (sic) the contribution of, and benefits to, women and youth.

- PSTA4, p. 25.

The association of women/subsistence farming and men/market-based agriculture is made in value-laden statements such as “…women are still overwhelmingly engaged in producing lower-value subsistence crops while men tend towards cash crops” (GYMS, p. 18) and “…most of women (sic) involved in agriculture are in subsistence farming, as they have limited access to the market and decision-making power in their family” (NAEB, p. 63). While cash crops remain unspecified, subsistence crops, the alleged domain of women, are discouraged by the policies because of their low economic value. Women farmers are instead targeted to integrate into modernized market-based farming, for example through interventions for increased resource access and improved technical capacities and business skills. This will also increase women’s economic empowerment, the policy implicitly assumes, which is anticipated to have positive effects on food security, poverty reduction, and economic growth.

Because of the assumed correlation between market-based agriculture, poverty reduction, and economic growth, possibly via women’s economic empowerment, subsistence farming is constructed as economically unviable and a historical artefact in depictions of modern capitalist Rwandan agriculture. The division between desired market-based and undesired subsistence farming is underpinned by neoliberal idea(l)s of commercialization, competition, and economic growth in line with the GR4A. We find that the one-sided preference for modernized agriculture obscures perspectives that insist on a more nuanced picture and argue for the interdependency and co-existence of subsistence and market-based capitalist farming in Rwanda’s agrarian transition (Clay 2018; Illien et al. 2021).

We suggest that the hierarchical divisions described legitimize women’s agricultural productivity as the main problem for gendered inequality. We consider this a simplistic and inadequate problematization, since the policy only symbolically recognizes underlying issues of unequal gender roles and responsibilities that shape farming practices. Most gender related proposals argue for the improvement and change of women’s way of farming, while significantly fewer consider the underlying gender norms and responsibilities. The policy thus problematizes women’s farming practices rather than the drivers for women and men’s different farming. In our view, this represents a government ambition to integrate women in market-based farming via gender mainstreaming tools to increase their contribution to economic growth. Gendered divisions of work, especially women’s responsibilities for care and household work, as a driver for women’s predominance in subsistence farming is only occasionally considered. For example, a seemingly ambitious target is set by the GYMS to achieve gender-equal division of rural household work by 2026, and men are proposed to engage in the work for gender equality.Footnote 7 However, proposals to address this issue are insufficiently, if at all, brought into action plans, results frameworks, and budgets. Although it may be symbolically important at implementation and subsequent policy levels, we suggest that unequal divisions of work are merely recognized in the national policy, and with little ambition to challenge status quo or take action for change. The few proposals that challenge gender roles and responsibilities tend to suggest technological quick fixes aimed at reducing women’s reproductive work but only to enable increased productive farm work and more or higher quality household work and care:

“Foster labour-saving (sic) technologies, especially to reduce women’s workload and allow them to allocate more time to other productive activities and child feeding and care.”

- NAP, p. 24.

“The low levels of mechanization… restrict the engagement and performance of household tasks, more so by women.”

- AMS, p. 16.

This serves to show that the policy reinforces, or even exacerbates, dominant gender norms, specifically those regarding women as responsible for reproductive work. Contradictory to the vision of agricultural modernization and women’s integration into market-based agriculture, this approach rather keeps women associated to subsistence farming and leaves them burdened not only with additional productive responsibilities, but with continued and intensified expectations on reproductive work. Without profound challenge of deep-seated unequal gender norms, relations, and responsibilities between women and men, this integrationist approach risks reproducing and aggravating inequalities, and rendering gender mainstreaming into an instrument for economic growth rather than gender equal practices and outcomes.

Overgeneralizing the gender agricultural productivity gap

The view of women’s lower productivity as a problem is also legitimized through the policy’s reproduction of a dominant discourse of the gender agricultural productivity gap. When framing gender and youth issues in agriculture, the GYMS draws substantially on a technical analysis showing that Rwandan farms managed by women were overall 11.7% less productive than farms managed by men (UN Women et al. 2017). The findings of the analysis are explicitly preliminary, yet it forms the core of the policy’s gender analysis, and of the construction of women’s agricultural productivity as a key problem:

“By analysing the gender gap in agricultural productivity, we can identify underlying system constraints to inform agricultural policy, strategies and programmes… (sic).”

- GYMS, p. 14.

The emphasis on closing the productivity gap between women and men thereby forms the rationale for considering gender as an issue in agriculture, which further consolidates the view of productivity as a key aspect of gender issues.

Moreover, our analysis suggests that the GYMS overgeneralizes the evidence for the gender productivity gap in Rwanda. The evidence considers productivity at farm level, yet the policy ends up assuming this to be valid also at an individual level:

“The difference between the agricultural productivity… of female and male farmers is referred to as the gender agricultural productivity gap (sic).”

- GYMS, p. 14.

Although the GYMS initially refers to productivity of women and men-managed farms, we observe a shift throughout the strategy to a point where all women farmers’ productivity is targeted and problematized. It occurs through sweeping claims and proposals about women farmers with no specification about their position in the household, farm, or community. For example, it is claimed that “…a host of limitations constrain women’s ability to increase productivity.” (p. 18), and that “women… [are] to work in collaboration with men to increase their agricultural productivity” (p.38). We assert that this overgeneralization lacks support by evidence and that it incorrectly individualizes and feminizes the issue of gendered productivity differences. Generalizing evidence from farm to individual level and pointing to women’s productivity as the problem constructs the heterogeneous category of women farmers as a monolith legitimate for targeted intervention. The tapering attention to all individual women farmers also puts responsibility on women themselves to close the gender productivity gap. Thus, the remedy of women’s generally disadvantaged positions is put in their own hands.

The equally diverse social category of men is likewise constructed as a homogenous group, and their agricultural productivity is generalized to the individual level. In contrast to women, however, they are discursively produced as normative model farmers to which women ought to aspire. Since gendered inequality is problematized in terms of productivity, men emerge as unproblematic actors in relation to issues of gender, and thereby not in need of interventions such as gender mainstreaming. Reverse to constructing women as responsible, the representation of men as not part of the problem exempts them from liability to counteract unequalizing practices and structures. This further reduces the problem of gendered inequality in agriculture to an issue about women, which obscures the diverse and complex effects that gendered norms and power relations have also on men farmers, particularly those who are poor and marginalized. Importantly, the role of men in reproducing as well as changing practices and patterns of differentiation is obfuscated.

The policy’s reliance on and overgeneralization of the gender agricultural productivity gap constructs women’s farming as a problem, and gender mainstreaming as an instrument to agricultural and economic growth. Underlying factors for a farm-level gender productivity gap are circumvented or insufficiently addressed, such as gendered divisions of work, social protection, land tenure structures, and gender biased agricultural markets. We thus contend that the discursive practice of overgeneralization discussed here suppresses, or smothers (Davids and van Eerdewijk 2016), perspectives that view unequal power relations, norms, and structures as the problems that lead to such outcomes as the gender agricultural productivity gap.

Limited acknowledgment of underlying causes

Similar to the limited problematization of gendered division of work, attention to gender norms, structural inequalities, and power relations is scant. When considered, it appears as marginal and symbolic in relation to the dominant problematization of women’s productivity. The GYMS recognizes it through statements such as: “The patriarchal system that predominates rural life in Rwanda limits women’s access to and control over productive assets” (p. xvii). The PSTA4 states that “Women and men farmers in dual households are generally characterised (sic) by unequal power relations, leaving women with very limited decision-making powers” (p. 25). Similar expressions surface in the NAP and two of the other reviewed documents.Footnote 8

Despite this occasional recognition of underlying causes to gendered inequality, the documents nevertheless end up targeting their subsequent effects, in particular women’s overrepresentation in subsistence farming and gendered differences in productivity levels. Consideration of unequal power relations barely makes it from the GYMS to the wider policy framework, as indicated by a single reference to the issue in the NAP and PSTA4 respectively. As such, gender norms and structural inequalities as important problems in agriculture is diminished in favor of proposals for women’s increased productivity. The following quote is illustrative, as it begins by recognizing unequal power relations as an explanation for productivity differences but ends up targeting, thus problematizing, women’s technical skills and access to inputs.

“…unequal power relations leave women with limited decision-making powers. This affects their control over agricultural assets, inputs, produce, and capacity building opportunities, resulting in lower average productivity. Women empowerment (sic) is linked to many positive spill-over effects on the overall economy: household members’ health, food security and nutritional status, and reduction of gender-based violence and discrimination. Women economic empowerment (sic) will be fostered through provision of technical skills and promoting access to inputs.”

- NAP, p. 25.

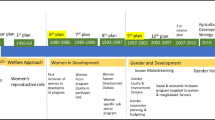

The policy’s problematizing lens remains firmly directed to women farmers’ practices and shortcomings, despite an apparent recognition of some of the processes and mechanisms by which inequality emerges. The recognition may hold some symbolic relevance for policy formulation and implementation at subsequent governance levels, since authoritative documents are part of the discursive and political struggles over what knowledges count as “true” and legitimate. However, the national agriculture policy analyzed here consistently and unequivocally compromises the problem of gendered inequality to technical, measurable propositions to fix women in order to achieve goals of national development and economic growth. We suggest that this way of constructing and legitimizing the problem is one that is politically manageable, and thus particularly suitable, within the GoR’s overall neoliberal and growth-oriented vision for development. Again, this undermines prospects to transform structures and relations of inequality and excludes men as part of both problems and solutions. Before turning to a reflection on alternative ways to problematize gendered inequalities, we synthesize our main insights made so far in Table 1.

Alternative problematizations of gendered inequality

We have hitherto questioned the discursive practices in Rwanda’s agriculture policy that problematize the symptoms and effects of gendered inequality rather than the causes. As indicated, however, the policy does occasionally address the underlying gender norms, power relations, and constraining structures, yet in problematic ways and marginal to the dominant approach. We now discuss how this symbolic recognition can be leveraged to enact a more emancipatory policy approach to gendered inequality in agriculture. For this, we draw on perspectives of gender and power within feminist political ecology (FPE) and emphasize the need to prioritize long-term strategic problems along with short-term practical ones. We also discuss how gender transformative approaches (GTA) to agricultural development may provide concrete policy guidance.

Gender as emergent through power relations

One alternative to Rwanda’s current policy approach is to engage with conceptualizations of gender as relational and performative, such as in contemporary feminist political ecology (FPE). Work with an FPE approach focuses on the relations of power that reproduce unequal socio-ecological conditions and outcomes (Elmhirst 2011; Nightingale 2011). Contrary to an essentialist notion of gender as binary and static, gender is seen as socially performed and constructed through actions and relations, including discursive practices in policy (Elmhirst 2018; Nightingale 2011). Such practices and relations are imbued with power, which is seen as a productive force embedded in the interactions that shape conditions and outcomes in particular ways. In the context of Rwanda’s agriculture, this helps to see how the interactions between agricultural actors, from farmers to policy makers to policy itself, are characterized by power imbalances that both shape and are shaped by ideas and assumptions about what the social categories of women and men can be and do. Such gendered power relations in turn influence the norms and structures that determine what people are expected to do in agriculture depending on their socially ascribed gender, how they are perceived of and treated by others, and how they perceive themselves and behave in relation to others (Gottschlich et al. 2017; Leder et al. 2019; Nightingale 2011). The view of gender as a dynamic process, rather than a fixed state, is useful because it can redirect policy’s problematizing lens towards the unequal power relations that lead to the gendered outcomes addressed in the policy, such as resource access, skills and education, market participation, and agricultural productivity. This implies that gendered inequality is to be seen as an integral problem to agriculture, and thereby to be explicitly considered throughout all areas and interventions across the policy documents. Moreover, a performative approach to gender and power facilitates policy to move from a growth-oriented, women-centered rationale for gender mainstreaming to one based on goals of justice and gender equality for the marginalized and disadvantaged farmers who live and work through Rwanda’s agrarian transition.

Practical and strategic policy problems

The issues of gender targeted by the current policy are, in one important sense, indeed practical challenges for the many farmers in Rwanda who experience the effects of structural inequalities, gender norms, and unequal power relations in highly material and everyday ways. In this context, how may a more solid problematization of the underlying structures and power dynamics through an FPE lens manifest in agriculture policy? How may Rwanda’s current policy framework look different with this approach?

We suggest that an agriculture policy with the alternative approach to gender outlined here couples the short-term practical interventions against gendered agricultural outcomes—the dominant focus in the current policy—with an increased emphasis on long-term strategic, emancipatory approaches for justice and social change (Moser 1989; Wallace 2020). The recognition of structural constraints and unequal power relations that currently surface in the policy may be seen as a crevice of opportunity upon which a reframed policy agenda may draw. The difference, as we see it, would lie in a drastic increase and prioritization of the long-term strategic interventions aimed at transforming the gender norms, power relations, and structures that perpetuate unequal outcomes. This would first imply a different problem analysis, including a rearticulation of gendered inequality as not a problem of women’s low agricultural productivity as a barrier to development and growth, but one of unequal gender norms, structures, power relations, and gender divisions of work. It would also imply significantly increased budget allocations for interventions framed within this problem analysis, as well as their improved and detailed frameworks for action, results, monitoring, evaluation, and learning, including qualitative indicators of change. Moreover, it could involve substantially increased resources and high priority given to knowledge expertise of gendered inequality and its causes throughout policy formulation and implementation processes.

Gender transformative approaches to strategic problems

Recent trends in agricultural research and development for gender equality can give concrete guidance to the policy’s shift to prioritize strategic problems and solutions. Over the past decade, an increased awareness of the significance of power relations and gender norms among agricultural development actors has led to an emergence of various gender transformative approaches (GTA) to policy and programming (Kantor et al. 2015; McDougall et al. 2021). GTA constitutes a broad response to the limits of how gender tends to be addressed in dominant agricultural discourse, including the instrumentalization of gender equality and the essentialist responsibilization of women for development and economic growth. Specifically, it “…represents a shift toward engaging with the underlying constraining social structures and intersectional power dynamics that perpetuate gender inequalities across scales” (McDougall et al. 2021, p. 388). A gender transformative policy can be characterized as “fostering examination of gender dynamics and norms and intentionally strengthening, creating, or shifting structures, practices, relations, and dynamics toward equality” (IGWG 2017, cited in McDougall et al. 2021, p. 368). Rwanda’s agriculture policy occasionally recognizes the need for critical examination of norms and power relations for equality, mostly in the gender and youth mainstreaming strategy (GYMS). However, we suggest a transformative approach to elevate from mere marginal and symbolic recognition to permeate every action area across all policy documents, including problem formulation, budgets, action plans, and results frameworks. The GYMS refer to Gender Action Learning Systems (GALS) as a possible tool to address unequal divisions of both productive and reproductive work and women’s unpaid workloads.Footnote 9 Such and similar tools and methodologies (see e.g. Cole et al. 2020) have potential to change deep-seated unequal gender relations, norms, attitudes, and behaviors (Kantor et al. 2015; McDougall et al. 2021; Njuki et al. 2016). We encourage the agriculture policy to integrate, scale up, and prioritize gender transformative interventions, accompanied by an approach to gender as performed through power-imbued practices and relations in line with an FPE perspective. Such shift could, among other things, increase policy’s emphasis on the need to consider issues of reproductive work along with productive in agrarian transformations (Debusscher and Ansoms 2013; Ossome and Naidu 2021). Before turning to the discussion and concluding remarks, we synthesize our reflections on alternative problematizations in Table 2.

Discussion and concluding remarks

In this paper, we have shown how Rwanda’s agriculture policy problematizes gendered inequality in a simplified and instrumentalist way, which appears as window dressing. Through hierarchical divisions of gender and agriculture and by overgeneralizing the evidence for a gender agricultural productivity gap in Rwanda, the policy constructs women’s agricultural productivity as the main problem and rationale for considering gender issues. This, we argue, renders gendered inequality a politically manageable (and measurable) problem that fits within the dominant discourse of mainstream, growth-driven agricultural development aligned with the GR4A paradigm. The policy discursively reproduces and exacerbates unequal gender norms and relations by constructing women farmers as problematic and men as normative farmers and by reinforcing gendered divisions of work. We thus contend that the policy mainly diminishes possibilities to realize gender equal outcomes in Rwanda’s agriculture. To disrupt the anticipated reproduction of inequalities, we suggest the policy to shift perspective to seeing gender equality as an end in itself. This implies redirecting the problematizing lens from the effects of inequality to its underlying causes. Putting issues of unequal power relations, gender norms, and responsibilities as integral drivers of every policy action area holds promise for sustained change towards gender equality and social justice. Such an alternative approach, suggested here to be underpinned by notions of gender as performed in power relations and practices in line with feminist political ecology (FPE), could enable the policy to prioritize strategic interventions that challenge deep-seated unequal relations and structural barriers to gender equality within agriculture. This could in turn lead to more equal agricultural outcomes. To concretize, we finally reflect on the prospects of applying gender transformative approaches (GTA) to such prioritized strategic long-term policy interventions.

Our analysis supports previous insights on African agriculture policy’s limited integration of issues about gendered inequality (Ampaire et al. 2020; Drucza et al. 2020) and insufficient attention to underlying structural inequalities (Ampaire et al. 2020). We confirm earlier assertions that policy aimed at women’s increased participation and integration into market-based agriculture in Rwanda may further entrench inequalities unless equivalent efforts are made to reduce and redistribute women’s unpaid reproductive work (Debusscher and Ansoms 2013; Illien et al. 2021) and to change gender norms and unequal power relations (McDougall et al. 2021). At the same time, our analysis contradicts recent claims that all development policies in Rwanda are gender mainstreamed and that persisting inequalities in agriculture is a matter of poor implementation, farmers’ inadequate adoption, and of a failure by policy to “trickle down” to farmers (Bigler et al. 2017; 2019). Instead, we argue that the policy’s window dressing and instrumental approach is bound to leave structural inequalities and power relations intact and unchallenged (Ampaire et al. 2020; Debusscher and Ansoms 2013). In this perspective, the gendered and uneven agricultural outcomes observed in research and problematized by policy are unsurprising.

Nevertheless, mainstream development interventions may indeed benefit both women and men (e.g. Bergman Lodin 2012; Quisumbing et al. 2015). As agricultural interventions in Rwanda are “plural, dynamic, and contested social-environmental process[es] situated within broader currents of agrarian change” (Clay 2018, p. 352), their outcomes are heterogeneous and in hybrid interaction with other processes of change. This highlights a continuous need to complement discursive policy analyses with empirical studies on how farmers approach, relate to, and partake in policy interventions on gendered terms, and what gendering effects and outcomes interventions have on lived realities. Treidl (2018) and Illien et al. (2021) are among recent examples of this in the Rwandan context.

In the context of African agricultural development, our assertion that Rwanda’s agriculture policy marginalizes and instrumentalizes gendered inequality aligns with the neoliberal, productivist ideas of the GR4A model that dominates the continent. Widely celebrated as a model example of GR4A implementation (Nyenyezi Bisoka and Ansoms 2020a), Rwanda’s approach to gender in agriculture is comfortably embedded in, and supported by, this mainstream paradigm. In relation to this, we highlight a need for research to “study up” agriculture policy in Africa beyond the national level. Critical interrogations of the gendered aspects of Africa’s contemporary agricultural transformation are emerging (e.g. Gengenbach et al. 2018; Nyambura 2015). However, deeper insights are needed about how knowledge-making processes are governed within and between African and transnational agricultural development institutions. Specifically, such analyses need to focus on how these processes shape, and are shaped by, specific ideas of gender and the intersecting social categories such as class, ethnicity, and age. This constitutes one aspect in understanding the origins and power-imbued trajectories of agrarian transitions, their implications for national policy processes, and their subsequent effects on people.

In terms of development more broadly, we concur with longstanding feminist critiques of the mainstream approach to gender equality as “smart economics” or “smart justice” to deflect problematizations of systemic gendered inequalities (Chant and Sweetman 2012; Davids and van Eerdewijk 2016; Gerard 2019; Parpart 2014). To paraphrase Cornwall and Edwards (2010, p. 8): “Policies that view women as instrumental to other objectives cannot promote women’s empowerment, because they fail to address the structures by which gender inequality is perpetuated over time.” To this end, we join those who advocate that short-term practical solutions to unequal agricultural outcomes must be coupled with a priority on strategic, transformative approaches for social justice (Cornwall and Rivas 2015; Moser 1989; Wallace 2020), for instance through engagement with GTAs (McDougall et al. 2021).

Our study brings a feminist analysis of agriculture policy to the debate of the gendering nature of agrarian transitions. Specifically, it provides a hitherto rare approach to studying the gendering effects of policy in the African agrarian context. We have questioned some of the taken for granted “truths” about gender in Rwanda’s agriculture policy to open up for alternative problematizations. Our study shows that knowledge in policy is not unequivocally fixed and clear-cut, but constructed, ambiguous, and dynamic. In particular, it shows that established meanings, ideas, and “facts” about gender and agriculture are legitimized through discursive practices, and that other types of knowledge can change the frame for social and political maneuver. Moreover, the particular problems, things, and people that policy targets are also dynamic and changeable, as they are also constructed and reconstructed through discursive practices. Such insights indicate the relevance of studying how discourses on humans, society, and nature operate through language to mobilize and (re)produce certain problems, subjects, and outcomes while suppressing others (Davila 2020; Gottschlich and Bellina 2017; Schneider 2015).

We concur that “Agrarian transformation is necessarily a feminist project and…linking agrarian transformation and feminism is the unavoidable challenge facing agrarian development policies” (Nyambura 2015, p. 311). Such feminist links will inevitably be manifold and vary across contexts and time. In this paper, we have explored how gendered inequality in Rwanda’s contemporary agriculture policy might be differently problematized through a view of gender as performed through power relations and practices with potentially uneven effects on distribution and control over benefits. Viewing socio-political environmental processes, such as agrarian transitions, in this way shifts the focus from those disproportionally affected by gendered inequality to the practices and relations that induce and perpetuate them. Possibly a winding process of struggle and deliberation in contemporary development contexts, such alternative perspectives would center social justice and transformation of gender norms and relations as cornerstones in political efforts for agricultural transformation.

Notes

Gender mainstreaming refers to strategies to purposefully integrate concerns and objectives for gender equality into policy practices (Davids and van Eerdewijk 2016). The original aim is to transform organizational processes and practices by eliminating existing gender biases (Benschop and Verloo 2006).

See Nyenyezi Bisoka and Ansoms (2020b) for an account of the process whereby Rwanda has embraced a productivist agricultural agenda.

Defined as the economic value of agricultural produce per unit of cultivated land (GoR 2019, p. 14).

The material included for analysis during this phase was: National Agriculture Policy (NAP) 2018; NAEB Strategic Plan: Increasing Agri-export revenues (NAEB) 2019; Rice Development Strategy (RDS) 2011, see Annex 1.

Yet, Illien et al. (2021), among others, show how strict subsistence farmers in Rwanda are rare and diminishing, and that subsistence farming is increasingly commodified and integrated along with capitalist agriculture.

Gender and Agriculture (GMO) 2017; National Strategy for Climate Change and Low Carbon Development 2011, see Annex 1.

Specifically, GALS refers to “a community-led empowerment methodology for individual life and livelihood planning, collective action and gender advocacy for change, and institutional awareness raising and changing of power relationships with service providers, private-sector stakeholders and government bodies” (Farnworth et al. 2013, p. 55).

Abbreviations

- AMS:

-

Agriculture Mechanization Strategy

- FPE:

-

Feminist Political Ecology

- GALS:

-

Gender Action Learning Systems

- GDP:

-

Gross Domestic Product

- GoR:

-

Government of Rwanda

- GR4A:

-

Green Revolution for Africa

- GTA:

-

Gender Transformative Approaches

- GYMS:

-

Gender and Youth Mainstreaming Strategy

- NAP:

-

National Agriculture Policy

- NAEB:

-

National Agricultural Export Development Board

- PSTA4:

-

4Th Strategic Plan for Agricultural Transformation

- WPR:

-

What’s the problem represented to be?

- USD:

-

United States Dollar

References

Acosta, M., S. van Bommel, M. van Wessel, E.L. Ampaire, L. Jassogne, and P.H. Feindt. 2019. Discursive translations of gender mainstreaming norms: The case of agricultural and climate change policies in Uganda. Women’s Studies International Forum 74: 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2019.02.010.

Addison, L., and M. Schnurr. 2016. Growing burdens? Disease-resistant genetically modified bananas and the potential gendered implications for labor in Uganda. Agriculture and Human Values 33 (4): 967–978. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9655-2.

Allan, E.J., S. Iverson, and R. Ropers-Huilman. 2010. Reconstructing policy in higher education: Feminist poststructural perspectives. New York: Routledge.

Ampaire, E.L., M. Acosta, S. Huyer, R. Kigonya, P. Muchunguzi, R. Muna, and L. Jassogne. 2020. Gender in climate change, agriculture, and natural resource policies: Insights from East Africa. Climatic Change 158 (1): 43–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02447-0.

Ansoms, A. 2008. Striving for growth, bypassing the poor? A critical review of Rwanda’s rural sector policies. The Journal of Modern African Studies 46 (1): 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X07003059.

Ansoms, A., and G.D. Cioffo. 2016. The exemplary citizen on the exemplary hill: The production of political subjects in contemporary rural Rwanda. Development and Change 47 (6): 1247–1268. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12271.

Ansoms, A., and N. Holvoet. 2008. Women and land arrangements in Rwanda: A gender based analysis of access to natural resources. In Women’s land rights and privatization in Eastern Africa, ed. B. Englert and E. Daley, 138–157. Currey: Woodbridge.

Ansoms, A., E. Marijnen, G. Cioffo, and J. Murison. 2017. Statistics versus livelihoods: Questioning Rwanda’s pathway out of poverty. Review of African Political Economy 44 (151): 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2016.1214119.

Arora-Jonsson, S., and S. Leder. 2021. Gender mainstreaming in agricultural and forestry institutions. In Routledge handbook of gender and agriculture, ed. C. Sachs, L. Jensen, P. Castellanos, and K. Sexsmith, 15–31. New York: Routledge.

Bacchi, C. 2009. Analysing policy: Wwhat’s the problem represented to be? Frenchs Forest: Pearson Australia.

Bacchi, C. 2012. Why study problematizations? Making politics visible. Open Journal of Political Science 2 (1): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojps.2012.21001.

Bacchi, C. 2017. Policies as gendering practices: Re-viewing categorical distinctions. Journal of Women, Politics and Policy 38 (1): 20–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2016.1198207.

Bacchi, C., and S. Goodwin. 2016. Poststructural policy analysis: A guide to practice. New York: Palgrave Pivot.

Benschop, Y., and M. Verloo. 2006. Sisyphus’ sisters: Can gender mainstreaming escape the genderedness of organizations? Journal of Gender Studies 15 (1): 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589230500486884.

Bergman Lodin, J. 2012. Intrahousehold bargaining and distributional outcomes regarding NERICA upland rice proceeds in Hoima district, Uganda. Gender, Technology and Development 16 (3): 253–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971852412459425.

Berry, M.E. 2015. When “bright futures” fade: Paradoxes of women’s empowerment in Rwanda. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 41 (1): 1–27.

Bigler, C., M. Amacker, C. Ingabire, and E.A. Birachi. 2017. Rwanda’s gendered agricultural transformation: A mixed-method study on the rural labour market, wage gap and care penalty. Women’s Studies International Forum 64: 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2017.08.004.

Bigler, C., M. Amacker, C. Ingabire, and E.A. Birachi. 2019. A view of the transformation of Rwanda’s highland through the lens of gender: A mixed-method study about unequal dependents on a mountain system and their well-being. Journal of Rural Studies 69: 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.05.001.

Burnet, J.E. 2011. Women have found respect: Gender quotas, symbolic representation, and female empowerment in Rwanda. Politics and Gender 7 (3): 303–334. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X11000250.

Chant, S., and C. Sweetman. 2012. Fixing women or fixing the world? ‘Smart economics’, efficiency approaches, and gender equality in development. Gender and Development 20 (3): 517–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2012.731812.

Christie, M.E., E. van Houweling, and L. Zseleczky. 2015. Mapping gendered pest management knowledge, practices, and pesticide exposure pathways in Ghana and Mali. Agriculture and Human Values 32 (4): 761–775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9590-2.

Cioffo, G.D., A. Ansoms, and J. Murison. 2016. Modernising agriculture through a ‘new’ Green Revolution: The limits of the Crop Intensification Programme in Rwanda. Review of African Political Economy 43 (148): 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2016.1181053.

Clay, N. 2017. Agro-environmental transitions in African mountains: Shifting socio-spatial practices amid state-led commercialization in Rwanda. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 107 (2): 360–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2016.1254019.

Clay, N. 2018. Seeking justice in Green Revolutions: Synergies and trade-offs between large-scale and smallholder agricultural intensification in Rwanda. Geoforum 97: 352–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.021.

Clay, N., and K.S. Zimmerer. 2020. Who is resilient in Africa’s Green Revolution? Sustainable intensification and Climate Smart Agriculture in Rwanda. Land Use Policy 97: 104558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104558.

Cole, S.M., A.M. Kaminski, C. McDougall, A.S. Kefi, P.A. Marinda, M. Maliko, and J. Mtonga. 2020. Gender accommodative versus transformative approaches: A comparative assessment within a post-harvest fish loss reduction intervention. Gender, Technology and Development 24 (1): 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718524.2020.1729480.

Cornwall, A., and J. Edwards. 2010. Introduction: Negotiating empowerment. IDS Bulletin 41 (2): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2010.00117.x.

Cornwall, A., and A.-M. Rivas. 2015. From ‘gender equality and ‘women’s empowerment’ to global justice: Reclaiming a transformative agenda for gender and development. Third World Quarterly 36 (2): 396–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1013341.

Daum, T., F. Capezzone, and R. Birner. 2021. Using smartphone app collected data to explore the link between mechanization and intra-household allocation of time in Zambia. Agriculture and Human Values 38 (2): 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-020-10160-3.

Davids, T., and A. van Eerdewijk. 2016. The smothering of feminist knowledge: Gender mainstreaming articulated through neoliberal governmentalities. In The politics of feminist knowledge transfer: Gender training and gender expertise, ed. M. Bustelo, L. Ferguson, and M. Forest, 80–96. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Davila, F. 2020. Human ecology and food discourses in a smallholder agricultural system in Leyte, The Philippines. Agriculture and Human Values 37 (3): 719–741. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-019-10007-6.

Debusscher, P., and A. Ansoms. 2013. Gender equality policies in Rwanda: Public relations or real transformations? Development and Change 44 (5): 1111–1134. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12052.

Drucza, K., C. Maria del Rodriguez, and B. Bekele Birhanu. 2020. The gendering of Ethiopia’s agricultural policies: A critical feminist analysis. Women’s Studies International Forum 83: 102420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2020.102420.

Elmhirst, R. 2011. Introducing new feminist political ecologies. Geoforum 42 (2): 129–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.01.006.

Elmhirst, R. 2018. Feminist political ecologies – Situated perspectives, emerging engagements. Ecologia Politica 54: 1–10.

Farnworth, C., M. Fones Sundell, A. Nzioki, V. Shivutse, and M. Davis. 2013. Transforming gender relations in agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa. Stockholm: SIANI.

Gengenbach, H. 2020. From cradle to chain? Gendered struggles for cassava commercialisation in Mozambique. Canadian Journal of Development Studies 41 (2): 224–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2019.1570088.

Gengenbach, H., R.A. Schurman, T.J. Bassett, W.A. Munro, and W.G. Moseley. 2018. Limits of the New Green Revolution for Africa: Reconceptualising gendered agricultural value chains. The Geographical Journal 184 (2): 208–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12233.

Gerard, K. 2019. Rationalizing ‘gender-wash’: Empowerment, efficiency, and knowledge construction. Review of International Political Economy 26 (5): 1022–1042. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1625423.

GoR. 2018. National Agriculture Policy. Government of Rwanda, Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources.

GoR. 2019. Gender and Youth Mainstreaming Strategy. Government of Rwanda, Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources.

GoR. 2020. Vision 2050. Government of Rwanda, Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning.

Gottschlich, D., and L. Bellina. 2017. Environmental justice and care: Critical emancipatory contributions to sustainability discourse. Agriculture and Human Values 34 (4): 941–953. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-016-9761-9.

Gottschlich, D., T. Mölders, and M. Padmanbhan. 2017. Introduction to the symposium on feminist perspectives on human–nature relations. Agriculture and Human Values 34 (4): 933–940. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-016-9762-8.

Harcourt, W. 2016. The Palgrave handbook of gender and development: Critical engagements in feminist theory and practice. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Huggins, C. 2017. Agricultural reform in Rwanda: Authoritarianism, markets, and zones of governance. London: Zed Books.

IGWG. 2017. The gender integration continuum. Interagency Gender Working Group. https://www.igwg.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Gender-Continuum-PowerPoint_final.pdf. Accessed 9 December 2021.

Illien, P., H. Pérez Niño, and S. Bieri. 2021. Agrarian class relations in Rwanda: A labour-centred perspective. The Journal of Peasant Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2021.1923008.

Ingabire, C., P.M. Mshenga, M. Amacker, J.K. Langat, C. Bigler, and E.A. Birachi. 2018. Agricultural transformation in Rwanda: Can gendered market participation explain the persistence of subsistence farming? Gender and Women’s Studies 2 (1): 4.

Jackson, C., and R. Pearson. 2005. Feminist visions of development: Gender analysis and policy. New York: Routledge.

Kansanga, M.M., R. Antabe, Y. Sano, S. Mason-Renton, and I. Luginaah. 2019. A feminist political ecology of agricultural mechanization and evolving gendered on-farm labor dynamics in northern Ghana. Gender, Technology and Development 23 (3): 207–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718524.2019.1687799.

Kantor, P., M. Morgan, and A. Choudhury. 2015. Amplifying outcomes by addressing inequality: The role of gender-transformative approaches in agricultural research for development. Gender, Technology and Development 19 (3): 292–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971852415596863.

Leder, S., F. Sugden, M. Raut, D. Ray, and P. Saikia. 2019. Ambivalences of collective farming Feminist Political ecologies from the Eastern Gangetic Plains. International Journal of the Commons 13 (1): 105–129.

Luna, J.K. 2020. ‘Pesticides are our children now’: Cultural change and the technological treadmill in the Burkina Faso cotton sector. Agriculture and Human Values 37 (2): 449–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-019-09999-y.

McDougall, C., L. Badstue, A. Mulema, G. Fischer, D. Najjar, R. Pyburn, M. Elias, D. Joshi, and A. Vos. 2021. Toward structural change: Gender transformative approaches. In Advancing gender equality through agricultural and environmental research: Past, present, and future, ed. R. Pyburn and A. van Eerdewijk, 365–420. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

McHoul, A., and W. Grace. 1993. A Foucault primer: Discourse, power, and the subject. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Meador, J.E., and D. O’Brien. 2019. Placing Rwanda’s agriculture boom: Trust, women empowerment and policy impact in maize agricultural cooperatives. Food Security 11 (4): 869–880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-019-00944-9.

MenCare 2021. About MenCare. https://men-care.org/about-mencare/. Accessed 1 July 2021.

MenEngage 2021. The Rwanda MenEngage Network (RWAMNET) brings together organizations to engage men and boys for gender equality in Rwanda. http://menengage.org/regions/africa/rwanda/. Accessed 1 July 2021.

Moser, C.O.N. 1989. Gender planning in the Third World: Meeting practical and strategic gender needs. World Development 17 (11): 1799–1825. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(89)90201-5.

Nation, M.L. 2010. Understanding women’s participation in irrigated agriculture: A case study from Senegal. Agriculture and Human Values 27 (2): 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-009-9207-8.

Nightingale, A.J. 2011. Bounding difference: Intersectionality and the material production of gender, caste, class and environment in Nepal. Geoforum 42 (2): 153–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.03.004.

NISR. 2012. The evolution of poverty in Rwanda from 2000 to 2011: Results from the household surveys. Kigali: National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda.

Njuki, J., A. Kaler, and J.R. Parkins. 2016. Conclusion: Towards gender transformative agriculture and food systems: Where next? In Transforming gender and food security in the Global South, ed. J. Njuki, J.R. Parkins, and A. Kaler, 283–291. New York, NY: Routledge.

Nyambura, R. 2015. Agrarian transformation(s) in Africa: What’s in it for women in rural Africa? Development 58 (2): 306–313. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41301-016-0034-0.

Nyenyezi Bisoka, A., and A. Ansoms. 2020a. Resistance to the New Green Revolution in Africa: The revenge of lives over norms. In Resistances - Between theories and the field, ed. S. Murru and A. Polese, 149–167. London: Rowman & Littlefield International.

Nyenyezi Bisoka, A., and A. Ansoms. 2020b. State and local authorities in land grabbing in Rwanda: Governmentality and capitalist accumulation. Canadian Journal of Development Studies 41 (2): 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2019.1629884.

Nyenyezi Bisoka, A., C. Giraud, and A. Ansoms. 2020. Competing claims over access to land in Rwanda: Legal pluralism, power and subjectivities. Geoforum 109: 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.04.015.

Okito, M. 2019. Rwanda poverty debate: Summarising the debate and estimating consistent historical trends. Review of African Political Economy 46 (162): 665–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2019.1678463.

Ossome, L., and S. Naidu. 2021. The agrarian question of gendered labour. In Labour questions in the global South, ed. P. Jha, W. Chambati, and L. Ossome, 63–86. Singapore: Springer.

Parpart, J.L. 2014. Exploring the transformative potential of gender mainstreaming in international development institutions. Journal of International Development 26 (3): 382–395. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.2948.

Quisumbing, A.R., D. Rubin, C. Manfre, E. Waithanji, M. van den Bold, D. Olney, N. Johnson, and R. Meinzen-Dick. 2015. Gender, assets, and market-oriented agriculture: Learning from high-value crop and livestock projects in Africa and Asia. Agriculture and Human Values 32 (4): 705–725. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9587-x.

Razavi, S. 2009. Engendering the political economy of agrarian change. The Journal of Peasant Studies 36 (1): 197–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150902820412.

Sachs, C.E. 2019. Gender, agriculture and agrarian transformations. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

Schneider, M. 2015. What, then, is a Chinese peasant? Nongmin discourses and agroindustrialization in contemporary China. Agriculture and Human Values 32 (2): 331–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-014-9559-6.

Tavenner, K., and T.A. Crane. 2018. Gender power in Kenyan dairy: Cows, commodities, and commercialization. Agriculture and Human Values 35 (3): 701–715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-018-9867-3.

Treidl, J. 2018. Sowing gender policies, cultivating agrarian change, reaping inequality? Intersections of gender and class in the context of marshland transformations in Rwanda. Antropologia 5 (1): 77–95.

Tsige, M., G. Synnevåg, and J.B. Aune. 2020. Is gender mainstreaming viable? Empirical analysis of the practicality of policies for agriculture-based gendered development in Ethiopia. Gender Issues 37 (2): 125–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-019-09238-y.

Wallace, T. 2020. Re-imagining development by (re)claiming feminist visions of development alternatives. Gender and Development 28 (1): 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2020.1724698.

Wangui, E.E. 2008. Development interventions, changing livelihoods, and the making of female Maasai pastoralists. Agriculture and Human Values 25 (3): 365–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-007-9111-z.

WB. 2019. Rwanda systematic country diagnostic: Report No. 138100-RW, World Bank Group.

WB Data. 2021. Rwanda. https://data.worldbank.org/country/rwanda. Accessed 10 June 2021.

Weedon, C. 1996. Feminist practice and poststructuralist theory. Oxford: Blackwell Publisher.

WEF. 2019. Global gender gap report 2020. Cologny/Geneva: World Economic Forum.

Wise, T.A. 2020. Failing Africa's farmers: An impact assessment of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa. Working Paper No. 20–01, Global Development and Environment Institute, Tufts University.

UN Women, UN Development Programme, and UN Environment. 2017. Equally productive? Assessing the gender gap in agricultural productivity in Rwanda. Kigali, Rwanda.

Acknowledgements