Abstract

Increasing women’s participation in intrahousehold decision-making has been linked with increased agricultural productivity and economic development. Existing studies focus on identifying the decision-maker and exploring factors affecting women’s participation, yet the context in which households make decisions is generally ignored. This paper narrows this gap by investigating perceptions of women's participation and the roles of social norms in agricultural decision-making. It specifically applies a fine-scale quantitative responses tool and constructs a women’s participation index (WPI) to measure men’s and women’s perceptions regarding women’s participation in decisions about 21 agricultural activities. The study further examines the correlation between social norms in these perceptions as measured by the WPI for 439 couples in West Java, Indonesia. We find that first, men and women have different perceptions about women's decision-making in agricultural activities, but the same perceptions of the types of activities in which women have the most and the least participation. Second, joint decisions come in various combinations but overall, the women’s role is smaller. Third, social norms influence spouses' perceptions of decision-making participation, which explains most of the variation of the WPI. These results suggest that rigorous consideration of social norms is required to understand intrahousehold decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Women’s empowerment and gender equality are paramount in achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (Maiorano et al. 2021; UNDP 2020; Nationen 2014). Empowerment and equality for women are leading to faster economic growth, reduction in social inequalities, and scaledown of environmental degradation around the world (Bayeh 2016; Duflo 2012; Stevens 2010). As a form of empowerment, increasing women’s participation in intrahousehold decision-making can increase women’s bargaining power and improve development outcomes for women and their families (Acosta et al. 2019; Doss 2013; Duflo 2012). For example, women’s influence in intrahousehold decisions leads to better education and nutritional outcomes for women and children, and improved access to reproductive and family planning for women (see e.g. Quisumbing 2003 for a synthesis of the literature).

Empirical studies have intensively explored possible indicators of drivers of women’s participation in intrahousehold decision-making (e.g. Akter et al. 2017; Anderson et al. 2017; Frankenberg and Thomas 2001; Reggio 2011). For instance, it is usually found that greater human and physical asset ownership increase women’s participation in decision-making. However, this literature is criticised for ignoring the context in which the household makes decisions (Agarwal 1997; Mabsout and Staveren 2010), and the rationale behind who makes the decisions (Bernard et al. 2020). Without understanding the context, these indicators may produce misinterpretable and contradictory meanings (Kabeer 1999), and knowing who makes a specified decision is insufficient as it does not reveal everything about the decision-making process (Bernard et al. 2020; Seymour and Peterman 2018).

Invisible barriers retard the attainment of gender equality. These barriers are rooted in persistent discriminatory social norms as the prescribing social roles and power relations between men and women in society (UNDP 2020). These norms affect people’s perception of themselves and others and directly affect individuals’ choices, freedoms, and capabilities (UNDP 2020; Nationen 2014). Some studies suggest that the role of social norms is key to understanding the process of intrahousehold decision-making (see e.g. Agarwal 1997; Jayachandran 2020; Laszlo 2020; Lundberg and Pollak 1996; Mabsout and Staveren 2010; Maiorano et al. 2021). Ignoring gender norms can undermine women’s empowerment interventions when too much focus is given to increasing women’s asset ownership (Anderson et al. 2021). For example, having property rights to land does not necessarily increase women’s empowerment if the access to complementary resources (such as access to market, capital, or hired labour) are limited by social, cultural, or ideological factors (Bhaumik et al. 2016; David 1998; Petrzelka and Marquart-Pyatt 2011). Thus, understanding the role of social norms around gender becomes central in closing the gap in gender equality.

Women’s empowerment through increased decision-making participation is widely recognised as an important pre-condition for broad based agricultural growth (Alwang et al. 2017; Anderson et al. 2021). Existing studies have highlighted the importance of asset ownership and resource allocation in determining women’s participation in agricultural decision-making, and its impact on agricultural outcomes (Akter et al. 2017; Alkire et al. 2012; Anderson et al. 2017; Alwang et al. 2017; Chiappori 1988; Doss and Quisumbing 2018; Udry 1996). However, these studies do not consider how social norms around gender affect their findings.

Measuring participation in decision-making in the household can be challenging. Questions such as the ones included in the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI) (Alkire et al. 2012) are commonly applied as a proxy for decision-making participation in agriculture (Alwang et al. 2017; Anderson et al. 2017). These questions usually ask who makes decisions for an agricultural activity, with answers that typically include the following options: myself, my spouse, or jointly (both). Women making decisions by themselves or together with their spouses is an indication of higher bargaining power. This measurement, however, has been criticized for a few reasons. For example, a woman can be making decisions about agricultural activities by herself because her spouse is away or sick, and this could be an additional burden to her (Akter et. al 2017; Spangler and Christie 2020). Also, making decisions jointly does not necessarily mean that the interests of each spouse have the same weight (Akter et. al 2017).

Some studies complement decision-making questions in WEAI with qualitative information that improves understanding of the decision-making process (see e.g. Acosta et al. 2019; Malapit et al. 2020). These studies incorporate information not only about who makes the decision but also how decisions are made. However, it is not always possible to collect both quantitative and qualitative information. A recent study by Maiorano et al. (2021) developed a measure of empowerment that included measures of decision-making and the reasoning behind the decision process. The Maiorano et al. (2021) decision-making questions are similar to the ones included in the WEIA, with the same options for the respondents (myself, spouse, joint), but they do not include questions on decisions regarding agricultural activities.

Most of the recent literature on intrahousehold agricultural decision-making participation focuses on Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (Quisumbing and Maluccio 2003). Very little is known about South East Asia (Akter et al. 2017), where family farming systems are substantially different from Sub-Saharan Africa. In South East Asia, men and women farm plots together and couples own and manage assets jointly (Akter et al. 2017). Whereas in Sub-Saharan Africa, men and women farm separate plots and have differential access to inputs and farm resources (Peterman et al. 2014).

Indonesia is the fourth most populous country in the world and has experienced high rates of growth in agriculture in recent years (Hill 2018). It is experiencing rapid structural transformation and urbanisation (Kis-Katos et al. 2018). These conditions are likely to influence the roles of men and women in the agricultural sector (FAO 2019). For example, as men migrate to urban centres in search of labour opportunities, women stay on the family farm and become the farm managers (Mulyoutami et al. 2020). A few studies on women’s participation in decision-making and its welfare impacts focus on urban areas (Frankenberg and Thomas 2001; Jayachandran 2020; Rammohan and Johar 2009), while those looking into rural areas are limited and more focused on farm labour division by gender (see e.g. Jha 2004; Sajogyo et al. 1979; White 1984).

In this study, we investigate men’s and women’s perceptions toward women’s participation in agricultural decision-making in Indonesia, and the correlation of these perceptions and social norms. Our contribution is twofold. Firstly, we focus on 439 complete paired husband-wife surveys that ask both spouses the same questions separately and apply a fine-scale quantitative responses tool (0–10 Likert-type scale). The tool explores the extent to which decisions are made “jointly”, and allows us to compare and contrast responses from husband and wife. Secondly, we empirically measure individual perceptionsFootnote 1 on women’s participation in agricultural decision-making and explore the importance of social norms to understand these perceptions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that explicitly explores the roles of social norms in intrahousehold decision-making in rural Indonesia.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section “Theoretical background” provides a theoretical background. Section “Women in agriculture in Indonesia” introduces the context of women’s participation in agriculture in Indonesia. Section “Data and methods” presents the data and methods. Section “Results and discussion” provides the results and discussion. Section “Conclusions and implications” presents conclusions and implications.

Theoretical background

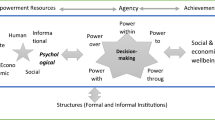

The literature on intrahousehold bargaining power has moved away from the assumptions of the unitary decision-making model of equal preferences among household members (Akter et al. 2017; Doss 1996, 2013; Quisumbing and Maluccio 2003). Chiappori (1992) followed by Quisumbing and Malucio (2003) proposed a collective model that allows different preferences for individuals within the household. This model assumes a household with two members, a man and a woman. The total utility of the household is equal to the weighted sum of the utility of each member's utility.Footnote 2 The weights are assumed to represent each household member’s bargaining power, which depends on income generation and a credible threat of living in the household. Laszlo (2020) incorporates psychosocial factors such as individual perceptions of self-worth, and social and cultural norms related to the roles of men and women. It is found that a woman's power to influence or control decisions within the household is positively affected by her income, her fall-back position, and her self-esteem, and negatively influenced by social norms that favour men.

Lundberg and Pollak (1996, followed by Browning et al. 2010; Cherchye et al. 2011) developed a bargaining power model in which a non-cooperative equilibrium emerges that reflects traditional gender roles and gender expectations. Men and women in the household are responsible for specific activities, as determined by their expected roles in society and what they are considered to know best. Therefore, each spouse specialises in making decisions and managing resources within their separate spheres.

These models explicitly consider how social norms affect women’s bargaining power and how they are likely to determine women’s role in the household. According to Agarwal (1994), social norms about the role of women, as justified by tradition and religion, can prevent women from being involved in agriculture. In Indonesia, women are perceived as mostly occupied with child-rearing and domestic activities, women allocate labour to agriculture, but agricultural activities and decisions are considered men’s domain (Herartri 2005; Puspitawati et al. 2018). This further leads to women’s lower participation in extension programs and limited access to land and agricultural inputs.

Women in agriculture in Indonesia

In Indonesia, approximately one-third of the total population is employed in agriculture, with women accounting for approximately 30% of all workers in the sector (ILO 2019). In rural communities, agriculture is the foundation of livelihood activities and is usually performed at the household level. Approximately 60% of the farming households are smallholders owning less than 0.5 hectares of land, growing multiple crops (e.g. paddy and horticultural crops/forestry), harvesting crops for household home consumption and/or for sale locally (Statistics Indonesia 2018). Generally, both men and women work together in agricultural production (Ekadjati 1995; Herartri 2005; Moji 1980; Sawit and O’Brien 1995).

Rural Indonesian women play multiple roles in agriculture, from planting and harvesting through post-harvest activities (FAO 2019). A clear division of labour by gender was observed with women occupied with weeding and pruning and men with land preparation and various chemical input applications, consistent with gender stereotypes of women being detail-oriented and careful and of men being strong (Koning et al. 2000). Women are also perceived as better at managing financial resources, with women influencing decisions on major household and land investments (Sajogyo et al. 1979).

In general, women’s roles in Indonesia are likely influenced by tradition, religious beliefs, plantation politics during Dutch colonialism, and dogmatic government during the New Order era from 1966 to 1998 (Backues 1992; Koning et al. 2000). In rural Indonesia, men are regarded as the head of the family and the primary decision-maker (Herartri 2005; Puspitawati et al. 2018). The traditional roles for wives and husbands emphasise that a woman’s place is in the domestic sphere; where men are responsible for family income while women run the household and take care of the children (Herartri 2005; Puspitawati et al. 2018). Although women play a significant role in agricultural activities, their participation is often considered to be merely helping their husbands, and their role is commonly under-recognized due to social norms that limit women’s participation in decision-making at both the household and community levels (Herartri 2005; Puspitawati et al. 2018; Wijers 2019). The occluded role of gender in intrahousehold decision-making may be profound and requires elucidation.

Data and methods

Data

This study uses primary data from 439 spouses (878 respondents) in agricultural households in the upper Citarum, the biggest watershed in West Java. This upper watershed is mostly located in mountainous areas and the majority of the study site is used for agriculture and forestry (Agaton et al. 2016). The rapid transformation of the agricultural sector in this area presents a great variety of agricultural activities. Increasing demand for agricultural products and its proximity to Bandung city, a major urban centre, led to rapid agricultural intensification, increased cultivation of horticultural crops, and increased diversification of agricultural and non-agricultural livelihoods (Agaton et al. 2016; Mulyono 2010).

The survey applied a multistage stratified random sampling procedure. First, Bandung and West Bandung Districts were selected purposely because 65% of the Citarum Watershed lies in these two districts. Second, six out of eight sub-watersheds were chosen purposely because it was located in rural areas (two sub-watersheds that are located in the urban area were not included due to the lack of farming activities). Third, 22 villages from both districts were randomly selected, representing 10% of all villages in these two districts. Finally, 20 households were randomly selected from each village. The survey was conducted in Bahasa, the local language of Indonesia by local enumerators not from the study site.

The data were collected in July–August 2019. The data set includes information about household members, household and farm characteristics, access to credit, organisation membership, and farm and non-farm physical assets ownership. The survey instrument further includes a gender-specific decision-making module, with questions about agricultural activities directed to husband and wife separately. The survey is thus unique in providing detailed information on intrahousehold decision-making with respect to 21 agricultural activities in six domains (production, conservation practices, processing and marketing, training, credits, and buying and selling assets).

Methods

Measuring participation in intrahousehold decision-making

The survey asked: “Who makes decisions in the following aspects for most of the time in the past year?” for a total of 21 agricultural activities.Footnote 3 The responses to these questions correspond to a Likert-type scale from 0 to 10, which 0 means that the spouse decides alone, and the respondent has no participation at all over the decision, and 10 means that the respondent has full participation over the decision and the spouse has no participation at all. If the respondent answered 5, it means that the respondent perceives that both participate equally in the decision. This provides finer-scale responses to decision-making questions and goes beyond most existing studies that include only three choices of decision-making: self, spouse, and jointly (Acosta et al. 2019; Seymour and Peterman 2018).

Capturing the role of social norms

To incorporate the role of social norms in intrahousehold decision-making we included a question about the rationale for men’s and women’s reported participation in each agricultural decision. This question, presented after the identification of the decision-maker and the decision-making participation, was: “Why do you think this decision is made this way?” Based on the households’ typologies described in Bernard et al. (2020), the responses options included in the survey were:

-

i.

Whoever has better knowledge about the activity (from now on knowledge).

-

ii.

This is how decisions are made in the family/village (from now on family/village).

-

iii.

Whoever allocates the most resources (from now on resources).

Knowledge The most informed individual is the one making decisions about an activity, corresponds to the Bernard et al. (2020) most-informed typology. As discussed in Mudege et al. (2015), there is a wide belief that men are regarded as the ones with knowledge and women are perceived as their helpers (not as farmers). Agarwal (1997) also mentioned that social norms about gender roles in agriculture affect who gets access to information (e.g. who is invited to extension activities and allowed to interact with extension agents).

Family/village Social norms of the community and/or the functions that men and women are expected to perform within the household affect decision-making, corresponds to three household typologies: dictator (one individual, usually the household head, makes all decisions in the households), separate sphere (individuals within the household are in charge of separate domains), and norms (the person who decides is determined by the community norms). These types are all determined by expected gender roles in society (Lundberg and Pollak 1996).

Resources The individual who contributes the most resources used for an activity is the one making decisions about the activity, corresponds to contributor household typology. It is not uncommon that women and girls, specifically in agriculture, are perceived to contribute less than men or boys (Agarwal 1997). Since the response rate to resources is less than 7%, implying limited variation in the data, we opt not to incorporate it in further analysis.Footnote 4 This limited variation is not surprising since, in the Indonesian context, it is commonly believed that family resources are perceived as belonging to the household after marriage (Akter et al. 2017).

Women’s participation index (WPI)

We constructed a women’s participation index (WPI) in agricultural decision-making to measure men’s and women’s perceptions toward women’s participation in agricultural decisions. We followed a widely used approach to estimate asset indices similar to Smits and Steendjik (2015) for the International Wealth Index and Almas et al. (2018), who applied this method to estimate a women’s empowerment index based on women’s perceptions of partner/spouse violence. We adopt this methodology to reduce the dimensionality of our data on intrahousehold decision-making in agricultural activities (Filmer and Pritchett 2001; McKenzie 2005) and also to account for the different weights of each decision.

Specifically, we perform a principal component analysis (PCA) on the responses to decision-making questions. We conducted a separate PCA for men’s and women’s responses. We generated the weights using PCA and used the loadings from the first component, which explains the largest part of the variation in the data, to weight the components of the indices (see online supplementary materials, Table S1). Using this method, the WPI ranges from 0 to 45. For easier interpretation, we used the squared PCA loadings to transform the WPI to be between 0 and 10, where 0 means that the individual has no participation in the agricultural decision at the household, and 10 means that the individual makes all the agricultural decisions without participation of their spouse.Footnote 5 Two resulting indices: WPIw and WPIm, where w means women and m means men, respectively capture women’s and men’s perceptions on women’s participation in decision-making in agricultural activities.

We understand that we can lose some information by aggregating the data in an index. For this reason, we present sex-disaggregated descriptive statistics for the 21 decisions and the WPI in the results section of the paper.

Multivariate analysis

We analyse the correlation between participation in agricultural decisions and social norms while controlling for individual and household characteristics likely to influence this correlation, using ordinary least squares (OLS) as follows:

where \(W{PI}_{xij}\) is the women’s participation index for x = women, men of individual \(i\) in household j, \({socialnorm}_{xij}\) represents individual i’s perceptions of social norms in household j from the perspective of x, \({individual}_{xij}\) represents individual i’s characteristics in household j from the perspective of x, \({diffspouses}_{ij}\) represents characteristics differences between spouses for individual i in household j, \({household}_{ij}\) represents household characteristics for individual i in household j, \({enumerator}_{ij}\) represent the gender of enumerator that interviewed individual i in household j and is used to capture any systematic effect of the enumerator gender, and \({district}_{j}\) represent the district location of household j, to capture the regional effect. \({\upbeta }_{1}, {\upbeta }_{2}, {\upbeta }_{3}, {\upbeta }_{4}, {\upbeta }_{5}, {\upbeta }_{6}\) are parameters to be estimated and \({\upvarepsilon }_{ij}\) as the error term.

Social norms variables are measured using knowledge, and family/village. Knowledge indicates respondent's perception related to the reason on the decision is made based on the person who has better knowledge, and family/village measures respondent’s perception on the reason is made because it is commonly done that way in the family or village. In our study we have 21 activities, thus if a respondent answers knowledge for all 21 activities, then his/her knowledge value will be 21; and 0 if the respondent answers none on knowledge for all 21 activities (see Table 1 for further details).

The first set of covariates capture a variety of observed individual characteristics which are usually hypothesized to play a role in determining women’s participation in decision-making. These include age (e.g. Anderson et al. 2017; Frankenberg and Thomas 2001; Reggio 2011), years of education (e.g. Doss 2013; Kabeer 2005; Sen 1999), agricultural organisation membership (e.g. Agarwal 1997; Lyon et al. 2017) and off-farm activity involvement (e.g. Bayudan-Dacuycuy 2013; Maligalig 2019). Interestingly, findings regarding these factors are usually mixed, where some studies suggest a significant effect while others do not, offering a further reason to test these factors in the current study.

In addition to individual characteristics, differentials of certain observed characteristics are also included. As suggested by Agarwal (1997), because “inequalities among family members in respect to determinant factors would place some members in a weaker bargaining position relative to others”, affecting the level of participation in the decision-making. In this study, differentials in age, years of schooling, and agricultural organisation membership between husband and wife are used, based on literature findings (Brown 2009; Doss 2013).

Household characteristics are further included to capture variations at this level. Following literature findings, women family farm labour participation (Bokemeier and Garkovich 1987; Rosenfled 1986), the total number of young children up to five that live in the household (in the spirit of Anderson et al. 2017), men to women ratio in the household (e.g. Brown 2009; Quisumbing and Malucio 2003), whether or not parents/parents-in-law living in the householdFootnote 6 (e.g. Anukriti et al. 2020; Bayudan-Dacuycuy 2013), land size (e.g. Alwang et al. 2017), and household asset index (e.g. Doss 2013) are used as variables to capture household characteristics \(.\)

Finally, we control for the gender of the enumerator. Alwang et al. (2017) found a tendency that men respondents that are interviewed by women enumerators to give a more positive response to wife's participation in decision-making. We also control for location in West Bandung district, since it is relatively closer to a major metropolitan area (Bandung city). Such proximity provides off-farm paid labour opportunities to women, and more urbanised settings, with less tight-knit communities, “may demonstrate a relaxation in social and gender norms” (Bradshaw 2013).

In identifying the determinant of WPIw and WPIm, we conducted two separate estimations. To adjust for potential heteroscedasticity, standard errors are clustered at the village level (Wooldridge 2002).

Results and discussion

Participation in agricultural decisions

Figure 1 presents the kernel probability distributions of the responses to decision-making questions for men and women. Most of the responses are around five and below and vary depending on the agricultural activity in question. Figure 1 shows that regardless of the activities (with a couple of exceptions), the spectrum of women’s decision-making participation responses is relatively wide, indicating that the “joint” decision is arrived at through various combinations.

In general, compared to women, men hold a quite different perception about women’s participation in decision-making. First, the kernel distribution for men’s responses is below the one for women’s responses, indicating that men perceive women’s participation to be lower than women perceive it themselves. Second, almost 40% of men perceive that women have zero participation, almost twice the level of women’s own perception. The kernel distribution for each activity also shows consistent results (see online supplementary materials, Figs. S1 to S21 for details).

Figure 2 shows a very visual representation of the degree of agreement between the women’s group and the men’s group. It shows that in general, the responses between the 25th and the 75th percentile for the women’s group are relatively shorter (more condensed) than the men’s. This suggests that the women’s group has a high level of internal agreement (more consistent response), while the men’s group holds quite different opinions about women’s participation.Footnote 7 The upper quartiles show that 75% of the women’s group and 75% of the men’s group perceive that women’s participation in agricultural decision making is less than five, partially explaining why the boxes are between zero and five. The medians (marked by “x”) that are shown in the box plots suggest women’s responses are skewed to the right (with most of the medians falling at five), indicating that women’s responses are closer together at higher scores. Meanwhile, the men’s responses are skewed to the left (closer to the lower scores).

Based on the average values for women’s and men’s responses, women perceive that their participation is higher than what the men perceive, in every single decision (online supplementary materials, Fig. S22). Women reported less than equal participation in decision-making with respect to their spouses, with average values between 2.9 to 4.3. Men tended to report more that women did not participate in the decision at all. Women reported higher levels of participation in decision-making for when and how to tend the crops, land purchase and sale, and credit requests for agricultural investment. This is consistent with an early study by Sajogyo et al. (1979) who reported that women in West Java were influential in major household investment decisions such as farmland purchases and house improvements. On the other hand, women reported lower participation in conservation decisions including building and maintenance of soil and water conservation (SWC) structures, implementation of SWC practices, safety and practice in spraying, and attending agricultural training. Government programs introduced SWC practices in West Java through farmer’s groups, mostly formed by men and considered to be the domain of men (Backues 1992).

The differences between men's and women's perceptions are all statistically significant at the 0.01 level (see Table S2 in the online supplementary materials for details). This is consistent with the literature: men tend to report that their wives have lower participation in decisions, usually due to intrahousehold information asymmetries (Alkire et al. 2012; Alwang et al. 2017; Anderson et al. 2017). The differences are higher for when and how to tend crops, safety and practices in spraying chemical inputs, and when and how to harvest crops. Whereas the differences are lower for credit requests for investment, livestock, and land purchases and sales. This is consistent with West Java's previously documented division of agricultural activities along gender lines (Backues 1992; FAO 2019; Moji 1980).

Rationale for intrahousehold decision-making in agriculture

Overall, there is a relatively even contribution of knowledge and family/village to the rationale of agricultural decision-making, with variability depending on the type of decisions (see Fig. 3). Women tend to respond that decisions are made under family/village (i.e. this is how the decision is made in the family/village), whereas men tend to respond that decisions are made according to knowledge (i.e. whoever has better knowledge about the activity). Within the female respondent cohort, 33% to 54% of the women responded that decision-making for activities related to conservation practices, for which they reported lower levels of participation, is based on knowledge. A possible explanation is that in rural Indonesia, men tend to have more access to information about agricultural technologies when compared to women (FAO 2019; Meadows 2013).

Figure 3 also shows that there is a tendency to systematic gender differences in perceived reasons affecting the way the decision is made. In all activities except for what crops to grow, the percentage of women who answered knowledge is lower than the percentage of men. The difference is statistically significant for the reason for decision-making related to production (when and how to do land preparation and planting, when and how to tend the crops, buying yield-increasing farm inputs), conservation practices, processing process, and training (attending other agricultural training) (see Table S3 in the online supplementary materials for details). On the converse, the percentage of women who responded family/village is higher than the percentage of men for almost all activities (except for what crop to grow and land purchasing and selling), and statistically significant for 12 out of 21 activities. These results may indicate that women in West Java are highly influenced by social norms related to gender roles: the husband is the head of the family and primary decision-maker, and that agriculture is men’s domain (see Herartri 2005 and Puspitawati et al. 2018), or, that men believe that they are more knowledgeable about agricultural activities and farm management.

Regression results

The descriptive statistics and definitions for all the variables included in this section are presented in Table 1.

Women’s WPI in agricultural decision-making

From the women’s perspective, factors capturing social norms are important in predicting women’s participation in decision-making. Table 2 shows the estimation results of WPIw for three different specifications: Specification 1 excludes variables that capture social norms, Specification 2 includes only knowledge, Specification 3 includes only family/village.Footnote 8 It is first observed that, once social norm factors (knowledge and/or family/village) are considered (in Specifications 2, and 3) in predicting WPIw, there are noticeable increases in the R2 and adjusted R2, suggesting the explanatory power of these factors and the need to incorporate them in understanding intrahousehold decision-making.

Table 2 shows that knowledge (in Specification 2) is negative and significantly associated with the WPIw. Decision made based on knowledge is associated with 0.12 point reduction of WPIw. This implies that for agricultural activities, women perceive their lack of knowledge (relative to men) limits their decision-making participation. This finding is consistent with the findings in the descriptive results in section “Regression results” that on average, women reported lower participation in agricultural decisions relative to their husbands for all agricultural activities. On the contrary, the coefficient for family/village (in Specification 3) is positive and significantly associated with the WPIw, indicating for each decision that is made because of family/village, the WPIw index increases by 0.12 points. This implies that women have higher decision-making authority in agricultural activities if it is something that is commonly practiced in the community. These results cumulatively suggest that women’s perceptions of decision-making authority in agriculture are influenced by social norms.

Table 2 also shows that women’s individual characteristics are not playing a significant role, contrary to the findings of previous research (e.g. Agarwal 1997; Anderson et al. 2017; Anukriti et al. 2020; Doss 2013; Frankenberg and Thomas 2001; Rammohan and Johar 2009).Footnote 9 Thus, social norms are of utmost importance compared to other observable characteristics. The total number of agricultural activities where women participate is the only household characteristic significantly associated with women’s WPI. The more women participate as farm family labour, the higher the amount of decision-making power they have. This result is consistent in both developing and developed country settings (e.g. Anderson et al. in 2017 for the case in Tanzania, and Bokemeier and Garkovich, in 1987 for the context of Kentucky farm women in The United States).

Men’s WPI in agricultural decision-making

From the men’s perspective, social norms are also important factors in predicting women’s participation in decision-making. Table 3 shows the estimation results for the correlation of the men’s WPI. Overall, there are noticeable increases of R2 and adjusted R2 from specification 1 to specification 2, and 3, suggesting the explanatory power of the social norm factors. These findings are consistent with what we found for the correlates of the women’s WPI, with the most variation in women’s participation in decision-making explained by social norms.

In Specification 2 and 3, WPIm is negatively correlated with knowledge and positively correlated with family/village. These findings suggest that men also perceive that lack of knowledge in agricultural activities limit women to participate in decision-making and they also perceive that women can participate more in the domains in which it is compliant with the norms. This is also consistent with the finding from the WPIw.

In all specifications, WPIm is correlated with men’s education, the higher the husband’s education level, the higher the WPIm. There are some possible explanations for this positive effect. First, education may impose men to a better understanding of the importance of women’s role in intrahousehold decision-making (ILO 2014). Second, related to the off-farm activities. Better-educated men have a higher probability of engaging in off-farm activities thus leaving farm matters to the wives consequently increasing women’s decision-making participation in agricultural activities.Footnote 10 The positive correlation of men’s education with the WPIm that we found in our study is consistent with the findings of Frankenberg and Thomas (2001) in the context of three ethnicities in Indonesia. They found that an increase in men’s education, increasing the probability that decisions in the household are made jointly with the spouse.

Other statistically significant correlations include the age difference between husband and wife, which is positively associated with the WPI (in all specifications). This indicates that the higher the age gap (with younger wife) the higher the WPIm. This is possibly related to whether the husband is at a non-productive age while the wife is still at a productive age, as in the case of Brown’s (2009) findings for China. However, additional analysis suggests that men 50 years of age or younger tend to report lower levels of women’s participation in agricultural decision making when compared to men older than 50 years of age as measured by WPIm (see online supplementary materials Table S7).

Consistent with the findings in the women’s WPI, men also perceive that women’s participation as family farm labour increases women’s participation in agricultural decision-making. This finding is consistent in all three specifications.

In all specifications, we find that in the wealthier households, men tend to report that women are less involved in agricultural decisions. It is consistent with Koning et al. (2000) findings for Indonesia, in which the wealthy/high status families are more likely dictated by tradition in which women are expected to be submissive to their husbands. Another possibility is households’ reliance on agriculture to generate income decreases with wealth. In this case, it can be that they use a third party to manage the farm, and thus by nature, it will reduce women’s participation in decision-making. On the other hand, a wealthy family can also have a high reliance on agriculture and has sufficient income to liberate one of the couple (woman) from agricultural labour thus reducing women’s participation in the decision-making. However, this result contradicts Doss (2013) who stated that wealthier households in developing countries, have better access to information and higher social status, leading to higher levels of participation in decision-making. This finding can therefore be context-specific and points to the importance of considering norms, values, and social context in related studies.

Finally, we conducted robustness checks and estimated Eq. (1) for men and women using Seemingly Unrelated Regressions (SUR) and using instrumental variables (IV). Further explanation and results are included in online supplementary materials, Table S4 and Table S5. We find that our results are robust to different estimation methods with different assumptions.

Conclusions and implications

We investigate sex-disaggregated perceptions of women's participation and the roles of social norms about gender in agricultural decision-making. We constructed a WPI to measure men’s and women’s perceptions regarding women’s participation in 21 agricultural decisions and applied OLS regressions to survey data from 439 couples (878 individuals) in smallholder agricultural households in West Java, Indonesia. First, it is found that while the “joint” decision comes in a wide spectrum of combinations, on average women’s participation in the decisions is less than equal. Second, men and women have different perceptions about women’s decision-making participation. However, they have roughly the same perception of the types of activities that have the most and the least women’s participation in decisions, which seems to be related to gender labour division in Indonesia. Third, from both women’s and men’s perspectives, the variation in women’s participation in decision-making is mostly explained by the variables capturing the role of social norms and context.

These results have implications for the design of decision-making surveys concerning agricultural activities conducted by researchers, government organisations, and NGOs collecting intrahousehold decision making data. The inclusion of more flexible ways of measuring decision-making can improve our understanding of the meaning of joint decision, and the observed differences in perceptions about men’s and women’s involvement in intrahousehold decision-making processes. Similarly, the correlation between responses to decision-making questions and social norms highlights that those interest in collecting these data incorporate questions on the rationale behind decision-making at the household level to better grasp how social norms shape these intrahousehold processes.

Finally, our results provide empirical evidence in the context of West Java, Indonesia that social norms regard men as household heads and primary decision-makers, that agriculture is men’s domain and that men are the ones with knowledge about agriculture are deeply rooted in both individual and community viewpoints. Thus, governmental organisations and NGOs promoting women empowerment in agriculture are encouraged to design interventions that promote collective awareness of the role of women in agriculture and the value of their contributions to agricultural activity at the community and the national level. These considerations are needed if we wish to increase gender equality and women empowerment in agriculture in Indonesia and elsewhere.

Several limitations should be kept in mind when considering our results. First, the non-experimental nature of the data prevented us from making any strong causal inference. Second, we do not know whether or not the current condition is reflecting women's preferences in decision-making participation, which is beyond the scope of the current study. These limitations suggest the need for further research into this important issue.

Notes

The term of “perception” is used because it is a stated response rather than a direct observation of respondents behaviour.

\({U}_{household}\left(.\right)={\alpha U}_{man}(.)+(1-\alpha ){U}_{woman}(.)\) where U indicates utility, α and 1 − α are the weights that indicate the ability of man and woman to influence decision making within the household.

The enumerators asked these questions separately to men and women. The survey implemented protocols to ensure privacy of respondents while answering these questions, and that it was appropriate for enumerators of a different sex of the respondent to ask administer the gender survey module.

When resources was incorporated in the regression equations for women’s participation index (as in section “Regression results”), the R2 was very low (0.07) and the coefficient was not significant. When the regression using resources was run together with knowledge and family/village, that the variance inflation factor (VIF) was very high (325) which suggesting that resources was highly correlated with other independent variables in the equation.

The square of each loading represents the proportion of variance explained by a specific component thus the sum of squared loadings in PCA summing to 1 (Jolliffe and Cadima 2016).

The study by Bayudan-Dacuycuy (2013) in the Phillippines shows that the presence of the extended families (especially parents) increases the wife’s participation in decision making, in which the existence of parents tend to act as a balancing element in the household. In India the presence of parents in law (particularly of the mother-in-law) in the household can undermine women’s participation in decisions and women’s agency (Anukriti et al. 2020).

Jhangiani and Tarry (2014) explained that “men are, on average, more concerned about appearing to have high status and may be able to demonstrate this status by acting independently from the opinions of others. Thus, men are likely to hold their ground, act independently, and tend to refuse to conform (to women)”. Our findings from the regression results (Table 3) also show that men’s education affects their perception related to women’s participation in decision-making.

Variable knowledge and family/village are run separately as in Specification 2 and 3 because these two variables have a strong negative correlation (Pearson's correlation result shows -0.97) which suggests that if knowledge increases, the family/village decreases with the same magnitude, and vice versa.

For example, previous studies found that in multigenerational households, where women live with their parents-in-law, women's education does not increase their decision-making power (Cheng 2018). In our study less than 4% of the household are multigenerational households, and for these cases we did not find a statistically significant correlation between parents/parents-in-law live in the household and the WPIm and WPIw. We also conducted additional t-tests comparing the WPIm and the WPIw of multigenerational households and nuclear ones and did not find statistically significant differences (see online suplementary materials Table S6 for further details).

The correlation between men’s years of schooling and off-farm activities participation is positive at p < .01.

Abbreviations

- FAO:

-

Food and Agriculture Organisation

- ILO:

-

International Labour Organisation

- IV:

-

Instrumental variable

- NGO:

-

Non-government organisation

- OLS:

-

Ordinary least squares

- SUR:

-

Seemingly unrelated regression

- SWC:

-

Soil and water conservation

- UNDP:

-

United Nations Development Program

- VIF:

-

Variance inflation factor

- WEAI:

-

Women’s empowerment in agriculture index

- WPI:

-

Women’s participation index

- WPIm :

-

Women’s participation index from men’s perception

- WPIw :

-

Women’s participation index from women’s perception

References

Acosta, M., M.V. Wessel, S.V. Bommel, E.L. Ampaire, J. Twyman, L. Jassogne, and P.H. Feindt. 2019. What does it mean to make a “joint” decision? Unpacking intrahousehold decision-making in agriculture: Implications for policy and practice. The Journal of Development Studies 56 (6): 1210–1229. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2019.1650169.

Agaton, M., Y. Setiawan, and H. Effendi. 2016. Land use/land cover change detection in an urban watershed: A case study of upper Citarum Watershed, West Java Province, Indonesia. Procedia Environmental Sciences 33: 654–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2016.03.120.

Agarwal, B. 1994. A field of one’s own: Gender and land rights in South Asia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511522000.

Agarwal, B. 1997. Bargaining and gender relations: Within and beyond the household. Feminist Economics 3 (1): 1–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/135457097338799.

Akter, S., P. Rutsaert, J. Luis, N.M. Htwe, S.S. San, B. Raharjo, and A. Pustika. 2017. Women’s empowerment and gender equity in agriculture: A different perspective from Southeast Asia. Food Policy 69: 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2017.05.003.

Alkire, S., R. Meinzen-Dick, A. Peterman, A.R. Quisumbing, G. Seymour, and A. Vaz. 2012. The women’s empowerment in agriculture index. World Development 52: 71–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.06.007.

Almas, I., A. Armand, O. Attanasio, and P. Carneiro. 2018. Measuring and changing control: Women’s empowerment and targeted transfers. The Economic Journal 128 (612): 609–639. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12517.

Alwang, J., C. Larochelle, and V. Barrera. 2017. Farm decision-making and gender: Results from a randomized experiment in Ecuador. World Development 92: 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.11.015.

Anderson, C.L., T.W. Reynolds, and M.K. Gugerty. 2017. Husband and wife perspectives on farm household decision-making authority and evidence on intrahousehold accord in rural Tanzania. World Development 90: 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.09.005.

Anderson, C.L., T.W. Reynolds, P. Biscaye, V. Patwardhan, and C. Schmidt. 2021. Economic benefits of empowering women in agriculture: Assumptions and evidence. The Journal of Development Studies 57 (2): 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2020.1769071.

Anukriti, S., C. Herrera-Almanza, P.K. Pathak, and M. Karra. 2020. Curse of the mummy-ji: The influence of mothers-in-law on women in India. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 102 (5): 1328–1351. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajae.12114.

Backues, L. 1992. Women and development: An area study-The Sundanese of West Java. Researchgate archive. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/310479794. Accessed 23 March 2021.

Bayeh, E. 2016. The role of empowering women and achieving gender equality to the sustainable development of Ethiopia. Pacific Science Review b: Humanities and Social Sciences 2 (1): 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psrb.2016.09.013.

Bayudan-Dacuycuy, C. 2013. The influence of living with parents on women’s decision-making participation in the household: Evidence from the Southern Philippines. The Journal of Development Studies 49 (5): 641–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2012.682987.

Bernard, T., C. Doss, M. Hidrobo, J.B. Hoel, and C. Kieran. 2020. Ask me why: Patterns of intrahousehold decision-making. World Development 125: 104671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104671.

Bhaumik, S.K., R. Dimova, and I.N. Gang. 2016. Is women’s ownership of land a panacea in developing countries? Evidence from land-owning farm households in Malawi. The Journal of Development Studies 52 (2): 242–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2015.1060314.

Bokemeier, J., and L. Garkovich. 1987. Assessing the influence of farm women’s self-identity on task allocation and decision-making. Rural Sociology 52 (1): 13–36.

Bradshaw, S. 2013. Women’s decision-making in rural and urban households in Nicaragua: The influence of income and ideology. Environment and Urbanization 25 (1): 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247813477361.

Brown, P.H. 2009. Dowry and intrahousehold bargaining: Evidence from China. Journal of Human Resources 44 (1): 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhr.2009.0016.

Browning, M., P. Chiappori, and V. Lechene. 2010. Distributional effects in household models: Separate spheres and income pooling. The Economic Journal 120 (545): 786–799. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2009.02311.x.

Cherchye, L., T. Demuynck, and B. De Rock. 2011. Revealed preference analysis of non-cooperative household consumption. The Economic Journal 121 (555): 1073–1096. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2011.02432.x.

Cheng, C. 2018. Women’s education, intergenerational coresidence, and household decision-making in China. Journal of Marriage and Family 81 (1): 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12511.

Chiappori, P.A. 1988. Rational household labour supply. Econometrica 56 (1): 63–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/1911842.

Chiappori, P.A. 1992. Collective labour supply and welfare. Journal of Political Economy 100 (3): 437–467. https://doi.org/10.1086/261825.

David, S. 1998. Intra-household processes and the adoption of hedgerow intercropping. Agriculture and Human Values 15: 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007410716663.

Doss, C. 1996. Testing among models of intrahousehold resources allocation. World Development 24 (10): 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(96)00063-0.

Doss, C. 2013. Intrahousehold bargaining and resource allocation in developing countries. The World Bank Research Observer 28 (1): 52–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkt001.

Doss, C., and A. R. Quisumbing. 2018. Gender, household behavior, and rural development. IFPRI Discussion Paper 01772. http://www.ifpri.org/publication/gender-household-behavior-and-rural-development. Accessed 15 February 2021.

Duflo, E. 2012. Women empowerment and economic development. Journal of Economic Literature 50 (4): 1051–1079. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.50.4.1051.

Ekadjati, E. S. 1995. Kebudayaan Sunda: Suatu pendekatan sejarah (Sundanese culture: A historical approach). Jakarta: Pustaka Jaya.

FAO. 2019. Country gender assessment of agriculture and the rural sector in Indonesia. http://www.fao.org/3/ca6110en/ca6110en.pdf. Accessed 20 February 2021.

Filmer, D., and L.H. Pritchett. 2001. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data-or tears: An application to educational enrolments in States of India. Demography 38 (1): 115–132. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088292.

Frankenberg, E., and D. Thomas. 2001. Measuring power. IFPRI Food Consumption and Nutrition Division Discussion Paper 113. https://ebrary.ifpri.org/digital/collection/p15738coll2/id/73304. Accessed 15 August 2020.

Herartri, R. 2005. Family planning decision-making at grass roots level: Case studies In West Java, Indonesia. PhD dissertation, School of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences. Wellington, NZ: Victoria University of Wellington.

Hill, H. 2018. Asia’s third giant: A survey of the Indonesian economy. Economic Record 94 (307): 469–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4932.12439.

ILO. 2014. Engaging men in women’s economic empowerment and entrepreneurship development interventions. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---emp_ent/-ifp_seed/documents/briefingnote/wcms_430936.pdf. Accessed 15 June 2020.

ILO. 2019. ILOSTAT database country profile. Accessed 15 June 2020.

Jayachandran, S. 2020. Social norms as a barrier to women’s employment in developing countries. http://www.nber.org/papers/w27449. Accessed 25 August 2020.

Jha, N. 2004. Gender and decision-making in Balinese agriculture. American Ethnologist 31 (4): 552–572. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.2004.31.4.552.

Jhangiani, R., and H. Tarry. 2014. Principles of social psychology. 1st international edition. https://opentextbc.ca/socialpsychology/chapter/person-gender-and-cultural-differences-in-conformity/. Accessed 10 August 2021.

Jolliffe, I.T., and J. Cadima. 2016. Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. Philosophical Transactions Series a: Mathematical, Physical, and Engineering Sciences 374 (2065): 20150202. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2015.0202.

Kabeer, N. 1999. Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change 30 (3): 435–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00125.

Kabeer, N. 2005. Gender equality and women’s empowerment: A critical analysis of the third-millennium development goal 1. Gender and Development 13 (1): 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552070512331332273.

Kis-Katos, K., J. Pieters, and R. Sparrow. 2018. Globalization and social change: Gender-specific effects of trade liberalization in Indonesia. IMF Economic Review 66 (4): 763–793. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41308-018-0065-5.

Koning, J., M. Nolten, J. Rodenburg, and R. Saptari. 2000. Women and households in Indonesia: Cultural notions and social practices. Studies in Asian Topics Series No. 27. Richmond: Curzon Press.

Laszlo, S., K. Grantham, E. Oskay, and T. Zhang. 2020. Grappling with the challenges of measuring women’s economic empowerment in intrahousehold settings. World Development 132: 104959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.104959.

Lundberg, S., and R. Pollak. 1996. Bargaining and distribution in marriage. Journal of Economic Perspective 10 (4): 139–158.

Lyon, S., T. Mutersbaugh, and H. Worthen. 2017. The triple burden: The impact of time poverty on women’s participation in coffee producer organizational governance in Mexico. Agriculture and Human Values 34: 317–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-016-9716-1.

Mabsout, R., and I.V. Staveren. 2010. Disentangling bargaining power from individual and household level to institutions: Evidence on women’s position in Ethiopia. World Development 38 (5): 783–796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.11.011.

Maiorano, D., D. Shrimankar, S. Thapar-Björkert, and H. Blomkvist. 2021. Measuring empowerment: Choices, values and norms. World Development 138: 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105220.

Malapit, H., C. Ragasa, E.M. Martinez, D. Rubin, G. Seymour, and A.R. Quisumbing. 2020. Empowerment in agricultural value chains: Mixed methods evidence from the Philippines. Journal of Rural Studies 76: 240–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.04.003.

Maligalig, R., M. Demont, W.J. Umberger, and A. Peralta. 2019. Off-farm employment increases women’s empowerment: Evidence from rice farms in the Philippines. Journal of Rural Studies 71: 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.09.002.

McKenzie, D. 2005. Measuring inequality with asset indicators. Journal of Population Economics 18: 229–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-005-0224-7.

Meadows, L. 2013. Indonesia: Agri-fin mobile’s gender analysis highlights female farmer’s vital role in production, limited access to agriculture information. https://www.mercycorps.org/research-resources/indonesia-mobile-women-farmers. Accessed 3 August 2020.

Moji, K. 1980. Labour allocation of Sundanese peasants, West Java. Journal Human Ergology 9: 159–173.

Mudege, N.N., T. Chevo, T. Nyekanyeka, E. Kapalasa, and P. Demo. 2015. Gender norms and access to extension services and training among potato farmers in Dedza and Ntcheu in Malawi. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 22 (3): 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2015.1038282.

Mulyono, D. 2010. Konservasi lahan dan air di hulu Daerah Aliran Sungai (DAS) Citarum melalui pengembangan budidaya pertanian system agroforestry. Jurnal Rekayasa Lingkungan 6 (3): 253–262.

Mulyoutami, E., B. Lusiana, and M. Noodwijk. 2020. Gendered migration and agroforestry in Indonesia: Livelihoods, labor, know-how, networks. Land 9 (12): 529. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9120529.

Nationen, V. 2014. Gender equality and sustainable development. World Survey on the Role of Women in Development 2014. New York, NY: United Nations.

Peterman, A., J. Behrman, and A.R. Quisumbing. 2014. A review of empirical evidence on gender differences in nonland agricultural inputs, technology, and services in developing countries. In Gender in agriculture: Closing the knowledge gap, ed. A.R. Quisumbing, R. Meinzen-Dick, T. Raney, A. Croppenstedt, J. Behrman, and A. Peterman, 145–186. Dordrecht: Springer.

Petrzelka, P., and S. Marquart-Pyatt. 2011. Land tenure in the US: Power, gender, and consequences for conservation decision making. Agriculture and Human Values 28: 549–560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-011-9307-0.

Puspitawati, H., P. Faulkner, M. Sarma, and T. Herawati. 2018. Gender relations and subjective family well-being among farmer’s families: A comparative study between uplands and lowlands areas in West Java Province, Indonesia. Journal of Family Sciences 3 (1): 53–74. https://doi.org/10.29244/jfs.3.1.53-72.

Quisumbing, A.R., ed. 2003H. Household decisions, gender, and development: A synthesis of recent research. Washington, DC: IFPRI.

Quisumbing, A.R., and J.A. Maluccio. 2003. Resources at marriage and intrahousehold allocation: Evidence from Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Indonesia, and South Africa. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 65 (3): 283–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0084.t01-1-00052.

Rammohan, A., and M. Johar. 2009. The determinants of married women’s autonomy in Indonesia. Feminist Economics 15 (4): 31–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545700903153989.

Reggio, I. 2011. The Influence of the mother’s power on her child’s labour in Mexico. Journal of Development Economics 96 (1): 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.07.002.

Rosenfled, R.A. 1986. U.S. farm women: Their part in farm work and decision-making. Work and Occupations 13 (2): 179–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888486013002001.

Sajogyo, P., E.L. Hastutui, S. Surkati, W. Wigna, and K. Suryanata. 1979. Studying rural women in West Java. Studies in Family Planning 10 (11/12): 364–370. https://doi.org/10.2307/1966093.pdf.

Sawit, M., and D. O’Brien. 1995. Farm household responses to government policies: Evidence from West Java. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 31 (2): 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/00074919512331336775.

Sen, A. 1999. Enhancing women’s choices in responding to domestic violence in Calcutta: A comparison of employment and education. The European Journal of Development Research 11 (2): 65–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/09578819908426739.

Seymour, G., and A. Peterman. 2018. Context and measurement: An analysis of the relationship between intrahousehold decision-making and autonomy. World Development 111: 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.06.027.

Smits, J., and R. Steendijk. 2015. The International Wealth Index (IWI). Social Indicators Research 122 (1): 65–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0683-x.

Spangler, K., and M.E. Christie. 2020. Renegotiating gender roles and cultivation practices in the Nepali mid-hills: Unpacking the feminization of agriculture. Agriculture and Human Values 37: 415–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-019-09997-0.

Statistics Indonesia. 2018. The Results of Inter-Census Agricultural Survey 2018. https://www.bps.gp.id. Accessed 12, August 2020.

Stevens, C. 2010. Are women the key to sustainable development? In Sustainable development insight, ed. A. Najam, 1–8. Boston, MA: Boston University.

Udry, C. 1996. Gender, agricultural production, and the theory of the household. Journal of Political Economy 104: 1010–1046. https://doi.org/10.1086/262050.

UNDP. 2020. Tackling social norms: A game changer for gender inequalities. Transport and Trade Facilitation Series. UN. https://doi.org/10.18356/ff6018a7-en.

White, B. 1984. Measuring time allocation, decision-making and agrarian changes affecting rural women: Examples from recent research in Indonesia. IDS Bulletin 15 (1): 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.1984.mp15001004.x.

Wijers, G.D.M. 2019. Inequality regimes in Indonesian dairy cooperatives: Understanding institutional barriers to gender equality. Agriculture and Human Values 36: 167–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-018-09908-9.

Wooldridge, J. 2002. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data, 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) through the project of Agricultural Policy Research to Support Natural Resource Management in Indonesia’s Upland Landscapes (project number ADP/2015/043). Open access funding was provided by the Centre for Global Food and Resources, The University of Adelaide. Analytical results do not reflect the funder’s opinion and all mistakes are our own. We are grateful for helpful discussions with Professor Randy Stringer, Dr. Daniel Gregg, Henri Wira Perkasa, and the Indonesian Center for Agricultural Socio-Economic and Policy Studies (ICASEPS) team. We also thank Associate Professor Patrick O’Connor for his insightful comments and two anonymous reviewers who provided invaluable insights and suggestions that helped to improve the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qanti, S.R., Peralta, A. & Zeng, D. Social norms and perceptions drive women’s participation in agricultural decisions in West Java, Indonesia. Agric Hum Values 39, 645–662 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-021-10277-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-021-10277-z