Abstract

Food democracy is a concept with growing influence in food research. Food democracy deals with how actors may regain democratic control over the food system enabling its sustainable transformation. Following multi-level perspective framework's connotations, food democracy research has so far mainly focused on the niche level of the food system. An integrative approach that includes the perspectives of both the regime and the niche is still missing. This study addresses this research gap and proposes a new conceptual framework for food democracy that includes actors from the niche and the regime level. Furthermore, we apply our conceptual framework to the urban food system of Vienna (Austria) to explore the deeper meaning and practice of food democracy. Finally, we have conducted semi-structured interviews with actors at niche level (10) and regime level (25) within Vienna’s urban food system. Findings from this research broaden the perspective on food democracy and illustrate actors’ contributions at niche and regime level such as promoting organic food, re-localizing food provision, and procuring environmentally sustainable public food. Barriers to food democracy were also identified, e.g.: actors’ self-enhancement values, market-orientation, and capitalist alignment or lack of transparency. We conclude that actors at the niche and, to some extent, at the regime level may contribute to a process of on-going changes that fosters a transformation of established structures within the food system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The current food system is under critique. Ecologically, it contributes to depleting water ecosystems and soils, air pollution and biodiversity loss (Lang et al. 2009). It also leads to social (e.g., double burden of malnutrition), economic (e.g., market concentration) and political (e.g., international agreements, new goals for ecological public health) challenges (Wood 2000; Lang et al. 2009). These challenges can be seen as outcomes of differentiation and specialization processes in the food system –i.e., each actor (producers, processors, retailers, etc.) focuses on those aspects that are of main relevance for their specific tasks and operations (Noe and Alrøe 2015). These processes are driven by capital accumulation strategies resulting in environmental degradation, social exclusion and inequality (Harvey 2006). Thereby food production is decoupled from broader social and ecological contexts and the options for securing long-term sustainable food systems are decreasing (Noe and Alrøe 2015). Hence, food system sustainability depends on its capacity to include environmental conservation and context-specific cultural values as well as the protection of citizens and workers (Canal Vieira et al. 2018).

Sustainability of the food system is a crucial and common aspect of concepts such as food sovereignty and food democracy (FD) (Friedrich et al. 2019). Food sovereignty and FD also share values such as access to healthy food, creating local economic opportunities, building stronger communities and societies, and making food policy decisions accessible to all citizens (Hamilton 2005). These two concepts are closely related because of their critical views on the industrial food system and offer alternatives to remedy the food system's ecological, social and economic challenges (Bornemann and Weiland 2019). However, food sovereignty mainly focuses on producers by advocating for sustainable production methods and the right of small producers (e.g., peasants, family farmers, etc.) to control their production; while the focus of FD lies on the reinforcement of the role of citizens to democratize the food system (Carlson and Chappell 2015; van de Griend et al. 2019). Although food sovereignty has received more international attention in the last decades, the FD concept also influences food policy research, especially in the Global North (Carlson and Chappell 2015; Davies et al. 2019).

FD deals with the transformation of established structures within the food system. From a FD perspective, the food system needs to be rebuilt by adopting democratic principles and practices –i.e., actors regaining democratic control over the food system enabling its sustainable transformation (Lang 1999; Hassanein 2003). FD has been criticized for being too simplistic in its views on the food system, idealizing the local scale while demonizing the mainstream food system. Following the connotations of the multi-level perspective (MLP)Footnote 1 (Geels 2002), FD research has so far mainly focused on the niche level of the food system (Levkoe 2006; Sieveking 2019), neglecting contributions of actors at the regime level and their interactions with actors at the niche level. An integrative approach including both perspectives—of the regime and the niche—is still missing. Although actors at the regime level follow core elements of capitalism such as self-interest and capital accumulation, they operate in manifold ways and even co-exist with non-capitalist logics, organizations, and practices (see Feola 2020). Thus, we hypothesize that contextualizing FD at the niche level is a too narrow understanding of the concept, ignoring that actors at the regime level are part of the food system and may contribute to FD as well.

We aim to contribute to the emerging research on FD by integrating an MLP (Rip and Kemp 1998; Geels 2002) to the dimensions of FD suggested by Hassanein (2008, p. 289). We apply this conceptual framework to an urban food system due to cities' important role in sustainability and in fostering FD (Sonnino 2009; McFadden and Stefanou 2016). The novelty of our conceptual framework for FD lies in the inclusion of niche and regime perspectives, focusing on local stakeholders' contributions. We attempt to answer how food actors may contribute to, be hindered towards or hinder FD at both the niche and regime level. To this end, we use Vienna's urban food system (VUFS) as a case study for a European city aiming to enhance sustainable urban food policies.

The city of Vienna is part of the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact, the European Organic Cities Network and has a Food Policy Council.Footnote 2 From a broader socio-political context, dynamics such as social and spatial segregation patterns are not increasing in contrast to most other European cities, due to political integration measures. A high proportion of communal housing across the city (i.e., 31% of the Viennese live in municipal housing) makes Vienna the largest property owner in Europe and enables low spatial segregation (Benz 2019). With a population of 1.897.491 people, as of 2015, around 19% were at risk of poverty. Yet, there is a decreasing trend over the last years. Financial support, free education and childcare, and a public health system contribute to decreasing social segregation (OECD 2018; Kohlbacher and Reeger 2020). 40.7% of people living in Vienna are of foreign origin (i.e., foreign or Austrian nationals born abroad). The largest ethnic minority groups are from ex-Yugoslavia, Turkey, and other EU and Eastern European countries. In contrast to other Western European cities, ethnic minorities in Vienna are not concentrated along the urban fringe but rather in the areas neighboring the city center (OECD 2018; MA172019). Vienna sees positive population growth since 1995, mostly related to immigration from abroad. Thus, a growing part of the population is excluded from political participation, as the right to vote is linked to possession of Austrian citizenship (MA172019).

Conceptual framework: integrating FD and MLP

Lang (1999, p. 218) first introduced the FD concept as “the demand for greater access and collective benefit from the food system.” He identified FD as a force in bottom-up food policy and described the need to balance citizens, state, and economic actors in the food system (Lang 1999, 2005). In contrast, Hassanein (2003, 2008) revealed participation and political engagement of informed citizens to guarantee equal opportunities for shaping the system. FD, in line with sustainability principles, seeks to ensure ethical food practices (e.g., fair labor standards), to address unequally distributed social and environmental effects of the food system as well as the health of citizens and producers, to increase the market power of producers and workers and to enhance diversity within the food system (Pimbert et al. 2001; Hamilton 2005; Prost et al. 2018; Bornemann and Weiland 2019; Friedrich et al. 2019). FD supports the idea that “voting with your dollar” is not the best way to change the system and seeks to create mechanisms needed by citizens and communities to contribute to transformation pathways towards a more sustainable food system. There is a wide range of literature examining how initiatives at the niche level contribute to FD. Community supported agriculture, for example, fosters solidarity and collaborative processes in the community while providing knowledge about food, food production, and agricultural skills (Renting et al. 2012; Bornemann and Weiland 2019). However, initiatives at the niche level, and the FD movement have been criticized for promoting narrow or elitist strategies at the expense of other societal interests (e.g., affordability or cultural appropriateness of food) and for idealizing the concept of “local” as an innately positive attribute of food (Campbell 2004; Hamilton 2005; Sonnino 2013).

Agri-food scholars call for comparatively analysing the diverse and interacting food chains and for considering governance and power dynamics determined by complex interactions within the food system and beyond (Sonnino and Marsden 2006; Howard 2016; Anderson et al. 2019). We argue that FD needs to be critically reflected without dismissing actors at the regime level, such as governments, interest groups, retailers, or producers. While FD contrasts sharply with the current food system, regime actors may contribute to change the food system towards FD by making food available and affordable for citizens, by providing information about food, by promoting organic food, by activating citizens, or by creating spaces for participation (Hamilton 2005; McFadden and Stefanou 2016; Griend et al. 2019). In their study, Carlson and Chappell (2015) show how organizations and municipalities contribute to deep democracy by, for example, promoting participatory budgets (Porto Alegre, Brazil) or by facilitating dialogue sessions in rural communities enabling them to participate in climate policy decisions (Minnesota, U.S.A.).

However, the few studies on FD that include alternative (niche) and mainstream (regime) perspectives seem to look at these interactions from a quite normatively grounded critique of an increasingly transnational agri-food system and its dominant actors and modes of governance (e.g., Johnston et al. 2009; McFadden and Stefanou 2016). This paper adds a more analytic perspective on how niche and regime actors contribute to, or impede the implementation of FD ideals by integrating an MLP into our framework. However, we use the concept of “transformation” instead of “transition”—used by the sustainability transitions research community—, as FD deals with transforming the food system. These two concepts are often used interchangeably, yet the transition concept has been criticized for not questioning existing power dynamics (Hölscher et al. 2018), which are a core element of FD.

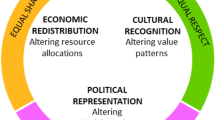

This study focuses on niche and regime level actorsFootnote 3' contributions to transforming the food system towards FD. To this end, we developed an empirically substantiated conceptual framework of FD, which is based on Hassanein’s (2008) key dimensions of FD. For our framework, we redefined all dimensions, thereby deepening the understanding of the dimensions of FD (Fig. 1 and Table 1). This framework is a descriptive model of how an urban food system could develop towards more FD. It contains a theory of change, namely that actors of the urban food system at niche and regime level build coalitions around the defined dimensions to drive FD.

First, collaboration among actors can create opportunities for innovation, for learning about one another, for increasing actors' participation in and understanding of the food system (Hassanein 2003, 2008; Prost et al. 2018). Second, FD involves citizens and actors in the food system who care about the community good (Hassanein 2008). Caring practices are essential for FD, e.g., friendly agricultural practices that ensure access to healthy food for all and fair wages (Norwood 2015; Friedrich et al. 2019). Third, citizens and actors in the food system need the knowledge necessary about food and the food system to participate effectively in their local food system and build and maintain FD. (Co-)learning allows for learning from one another about the sustainability of food and the food system (Levkoe 2006; Hassanein 2008). Regarding knowledge democracy,Footnote 4 it is crucial to consider various perspectives of food and the food system to ensure that different knowledge forms feed into decision-making (Freire 2000 in Adelle 2019). Finally, actors in the urban food system may be able to determine and produce desired results that contribute to food system sustainability—i.e., efficacy (Hassanein 2008) (Table 1).

The food system in the framework is structured in four interrelated subsystems: (i) Resource, representing the agri-food value chain—i.e., all activities from production to consumption; (ii) governance including government and authorities, interest groups, and businesses; (iii) food citizens, rather than consumers, as the active role of consumers in the food system is emphasized—i.e., food citizens may get engaged in and may actively shape the food system (Wilkins 2005) and; (iv) information, including media, research, and education (Ericksen 2008; Ostrom 2009). In this paper, actors at the regime level belonging to several subsystems are classified according to their main activity (e.g., supermarkets = resource subsystem, although they may also play a role as lobbyists in the governance subsystem). At the niche level, the subsystems’ boundaries are represented with a dashed line to show that classification of actors into food regime subsystems may not be possible. For the clarity of the framework, the authors decided to use this structure to display the actors’ contributions to FD on both levels (Fig. 1).

Methods

To analyze the complex relationships within a local food system and explore the deeper meaning and practice of FD, we applied our conceptual framework to the city of Vienna (Yin 1994).

Selection of food system actors

For selecting interview partners and focus group participants, purposive sampling was used to cover all subsystems identified by (López Cifuentes et al. submitted for publication) (i.e., the inclusion of niche and regime actors from different subsystems without establishing a quota) (Bernard 2006). Snowball sampling was used to help identify key niche and regime actors of VUFS (i.e., interview partners were asked to name other potential interviewees). In 2018, we conducted interviews upon the point of data saturation—i.e., we interviewed 40 people representing 25 regime actors and 10 niche actors (Table 2). The selected actors were classified along the subsystems and then further differentiated along sub-subsystems (López Cifuentes et al. submitted for publication) (Table 2).

Data collection and analysis

Exploratory fieldwork was based on two focus groups with representatives of Viennese niche and regime organizations. This led to the development of a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions (Bernard 2006) and the identification of potential interview partners. The interview guide focused on three main topics: (i) the structure and development of the different food actors and their role in VUFS, (ii) their orientation towards food system sustainability, and (iii) barriers and opportunities for the interaction among actors (niche-niche, niche-regime) towards food system sustainability. We referred to the term FD only indirectly to avoid influencing interviewees' answers by asking about sustainability as it is a crucial aspect for FD.

To analyze the collected data, we developed a code catalog (Fig. 1) that comprises deductive codes (i.e., the four FD dimensions defined in our conceptual framework) and inductive codes that emerged during the coding process. We used Atlas.ti software to support qualitative coding. Data analysis enabled a detailed exploration of niche and regime actors’ perceptions of their contributions and barriers to FD, within their levels and across levels.

Results: perceived FD contributions and barriers

Results are structured along the four dimensions of our conceptual framework (Fig. 1) and show actors’ contributions and barriers to FD. At an individual level, regime and niche actors may contribute to FD by adopting self-transcendent sustainability approaches, adopting different strategies towards efficacy with respect to food system sustainability and/or creating different kinds of knowledge. Intra and across levels, actors may also share the created knowledge and/or collaborate towards sustainability and thus contribute to FD. Actors may also be confronted with barriers to FD along the four dimensions, which are either inherent to the internal dynamics of the actors or the dynamics of the current food system (Table 3).

Orientation towards the community good

Among the interviewees, most niche actors and a few regime actors take a self-transcending approach of universalism and benevolence towards food system sustainability. They seem to be oriented towards the community good and prioritize practices going beyond their organizations' interests. Niche actors (N1, N4, N7), as well as interest groups (R12, R33, R34) and NGOs (R21, R22, R32) at the regime level, tackle the promotion of an environmentally sustainable food provision (e.g., increasing biodiversity, the share of organic food or reducing food waste). Some actors have a solidary approach towards the food system. At the niche level, interest groups try to integrate and empower socially disadvantaged citizens, such as immigrants and low-income persons (N9, N10). At the regime level, food banks provide free food to the people in need (R21, R22). About 20.0000 people in poverty get access to food from the largest local food bank. They are supplied with food donations or food (e.g., by retailers, bakeries) by local volunteers, which would have been thrown away otherwise (R22). Finally, niche actors of the resource subsystem (N1, N4, N8) aim to increase economic sustainability by orienting towards a fair price policy for food provision and consumption.

Apart from these self-transcending approaches, most interviewees conduct various practices towards the community good, next to other individualistic orientations –i.e., several niche and regime interviewees across different subsystems (N1, N2, N5-N9, R12, R20, R25, R26, R28, R29) increase citizens' food literacy through knowledge provision (e.g., on cooking skills, food production and origin). Furthermore, actors, mainly at the regime level (N1, N7, R12, R13, R17, R20, R23, R24, R25, R28, R30, R31), promote the re-localization of food provision (e.g., by preserving urban agricultural land (R28, R30) and increasing Vienna's food self-sufficiency (R22, R24, R31). While some niche interviewees (N2, N7, N7, N10) aim to develop large-scale approaches for their innovations, several interviewed regime actors have already implemented large-scale measures to promote, mainly, environmental sustainability. For example, municipal authorities, together with an organic farming association (R12, R14, R28, R31), among others, developed a program for integrating organic food and reducing food waste in public food procurement. Furthermore, retail chains promote organic food and other environmental measures (e.g., food packaging reduction) (R16, R17). An interest group points to the low orientation towards specific citizen-consumers' consumption behaviors (e.g., Halal food) within VUFS (N9) in terms of social sustainability. According to the Austrian trade association, ethnic minorities, such as the Turkish community, seem to consume more vegetables and buy food, often in greater quantities, preferably in specialized grocery shops or at food markets (R18). Interviewees rarely reported about their individualistic orientations. Only a few regime actors of the retail and distribution subsystems highlighted their orientation towards the self-enhancement value of power by increasing their market dominance in Vienna (R16), and of achievement by expanding their product range (R18). According to niche actors (N1, N2, N4), some regime actors (e.g., politicians, mainstream farmers, and retailers) lack an orientation towards social and environmental sustainability.

Efficacy with respect to food and the food system

Interviewees (N2, N6, R21) notice a growing number of niche innovations popping up in Vienna. Actors of the resource subsystem (N4, N7, R11, R14) perceive that these innovations could serve as lighthouse projects for others to follow (e.g., zero-waste packaging in retail). Several niche interviewees try to professionalize their innovations by optimizing niche internal structural processes (e.g., logistical organization of distribution, division of work, and responsibilities) (N1, N2, N5, N7-N9) and by tackling challenges within VUFS, such as legal frameworks change in favor of their innovation (N1, N2, N7). Moreover, niche interviewees (N2, N3, N5-N8) strive for efficacy to out-scale and/or up-scale by continually developing and experimenting with their innovation, expanding on it, and seeking funding for it.

Interviewees mentioned that powerful regime actors might be springboards for niche innovations and could leverage the niches' up-scaling (e.g., creation of laws favoring niches; adaption of niche innovations by the retail chain) (N2, N3, N6, R26, R32). Niche interviewees of the resource subsystem perceived that regime actors supported them in developing efficacy towards the food system (N2, N6). Regime actors of the resource and governance subsystems highlighted the integration of niche innovations into their organizations (R17) or their support for niche development (R11, R18, R22, R32). Furthermore, interviewees (N2, N3, N4, N7-N9, R12) perceive that municipal authorities and the local government can take the lead in contributing to food system sustainability. They may introduce local regulations and measures in favor of niche innovations (e.g., subsidies for sustainability measures) and food system sustainability (e.g., preservation of urban agricultural areas). Yet, municipal authorities (R28) highlight the dependence on national authorities when implementing regulations. Nevertheless, several interviewees of the governance subsystem (N10, R11, R14, R19, R22, R31) already see Vienna's municipal authorities as change agents who take specific sustainability measures, such as increasing the share of organic food and reducing food waste in public food procurement.

A niche interviewee (N10) perceived that niche actors seem to lack efficacy, appreciation, and visibility within the urban food system. They face difficulties finding interested collaboration partners (N2, N7) and suitable financial support (N1-N4, N7-N9) for their innovations. Internal organizational challenges (e.g., logistics, personnel management) seem to prevent niche interviewees from achieving desired outcomes towards food system sustainability (N1-3, N6, N7, N10). Furthermore, niche actors (N1, N2, N7-N9) seem to face restrictions on flexible and free experimentation due to limited financial resources. Niche interviewees perceive that, as soon as their organizations would out- and/or up-scale, they would reach structural, ideological, and financial limits (N1, N6, N7). Besides, most niche interviewees (N1-N3, N5-N8, N10) mention the existence of external barriers of societal (e.g., lack of societal acceptance for innovations), political (e.g., conservative policy, legal restrictions of innovation), and spatial nature (e.g., high rental costs for the limited space) within the VUFS.

Interviewees (N1, N4, N5, N8, N10, R14) perceive that farmers at the niche and the regime level depend on political lobbying and on national and European Union subsidies; they also struggle with an unfair price policy set by mainstream retail chains. Even educational organizations seem to depend on funding driven by economic or political interests (N5, R14). Niche and regime resource subsystem interviewees (N4, N8, R14, R15) criticize mainstream retail chains and gastronomy for their lack of sustainability resulting from a low and aggressive price policy. Moreover, several niche actors stated (N5, N7, N10) that mainstream retail chains and the food industry would misuse powers (e.g., lobbying, manipulation, putting pressure on other actors).

Finally, public organizations (R19, R20) perceive a lack of financial resources for food purchasing. Hence, sustainability quotas of public food procurement programs set by municipal authorities are difficult to meet.

Collaboration towards food system sustainability

Food actors established different collaboration types towards food system sustainability within or across the niche and the regime level, to jointly produce results, which cannot be achieved individually. Social collaborations occur both at niche and regime level. Niche actors meet and exchange within local networks, within their niche (N1-N3) or across niches (N1, N2, N5, N6, N8) as well as trans-locally. As the number of niche innovations rises, interviewees (N1, N2, N6-N10, R28) highlight the need for increased trust-building collaborations among niche actors and their stakeholders to empower them and to create a clear joint vision. Networking towards food system sustainability happens within (R11, R18, R20) and across different subsystems at the regime level. Both regime and niche interviewees (N1, N7-N10, R11, R22, R32) mention an exchange towards food system sustainability with municipal authorities and political parties. Several niche and regime actors (N3-N5, R22, R28) aim to exchange with educational institutions to spread or source information about food system sustainability.

Furthermore, resource collaborations towards food system sustainability are frequent at the niche and the regime level. At the niche level, actors collaborate materially with each other but also with regime actors by being supplied with food products (N2, N7, N9), by exchanging food products (N1), and by sharing agricultural machines (N1, N5). Moreover, niche actors of the resource subsystem provide or share agricultural fields or stalls on farmer markets (N1, N3, N4). Furthermore, the latter (N1-N3, N7, N8) also mentioned the provision of space and infrastructure (e.g., agricultural fields, kitchen, storage space) by regime actors (e.g., mainstream farmers, retailers, and restaurateurs), enabling niche actors to offer their food products and to experiment. Yet, at the regime level, interviewees seem to build material or spatial resource collaborations rarely. At the regime level, interviewees from the governance subsystem (R18, R28, R32) mentioned resource collaborations with niche actors who support their innovations with financial subsidies. Vice versa, niche interviewees (N2, N5-N9) claimed to receive financial subsidies from the latter. If needed, food citizens (e.g., friends and family) also support them financially (N1, N6, N8). At the regime level, interest groups and research institutions (R11, R12, R24, R31, R34) receive subsidies for taking sustainable measures (e.g., increasing the organic food share, training activities, academic work).

Institutional collaborations (concerning rules, regulations, and laws towards food system sustainability) are frequent between niche (N2-N4, N7) and regime actors of the governance subsystem (e.g., R27, R29) (e.g., implementing laws in favor of innovations). Regime actors collaborate to push regulations and interests (e.g., organic food) (R12, R14) and to implement guidelines and labels imposing sustainability criteria (R11, R26).

Niche interviewees (N1-N3, N7) perceive the lack of temporal and financial resources as barriers to networking and establishing collaborations. While niche actors (N1, N7) perceive that high bureaucracy levels seem to impede the building of collaborations, several interviewees (N1, N2, N7, N10, R14) sense that niche actors are often too radical and their innovations too expensive, which seems to keep regime actors from collaborating with them. Also, niche actors' low capacities (and sometimes unwillingness) to upscale and to adapt to mainstream structures seem to make a collaboration challenging (N10, R17). Furthermore, niche interviewees perceive a lack of trust (N3) and skepticism (N2) by regime actors (e.g., potential investors). Vice versa, a retail chain (R17) perceives a lack of trust by niche interviewees (N1, N5, N7, N10) (e.g., presumed non-adherence to agreements).

(Co-)learning towards food and the food system

Within VUFS, actors, at the niche and the regime level, produce different knowledge types about food and the food system; and they share it in one-way or mutual interaction(s). All niche interviewees produce strategic knowledge on how their innovations could solve specific sustainability issues within the food system. Niche actors seem especially interested in potential leverage effects they could nudge with their innovations (N2, N3, N6-N8). They also seem to develop ideas on how to change the food system with their innovations by involving food citizens (N7, N10), suppliers (N2, N7), investors (N6), or municipal authorities (N2, N10). Furthermore, niche and regime interviewees (N1-N3, N6-N8, R11, R18, R25, R27) strategically learn about landscape settings in and beyond Vienna (e.g., spatial conditions, legal concerns, food trends, potential target groups, collaboration partners). At the regime level, actors form the resource and governance subsystems (R12, R14, R25, R32) co-produce strategic knowledge with municipal authorities (e.g., R31) and/or universities (e.g., on innovations and measures that address specific sustainability issues) (e.g., R34). Several niche actors are international first movers in their field on a local or trans-local scale. Therefore, they have to create their own experiences, as other learning sources are rare (N1-N3, N5, N7, N8). Experiential knowledge production through trial and error is common among niche actors (N1, N4-N7). Only interest groups and a wholesale market at the regime level mentioned exchanging experiential knowledge with niche actors (R11, R32) or other regime actors (R15, R20).

Several niche actors and some regime actors, such as interest groups (R25), local authorities (R30), and research institutions (R24, R34), support food citizens in the creation of experiential food knowledge by organizing tastings and cooking courses (N2, N3, N9, R24), by enabling farm and garden visits as well as guided farm tours (N1, N3, N5, R25, R34) or by creating spaces for discourse about food and the local food system (N8, N10, R30). Scientific knowledge on niche innovations is often produced in cooperation with universities (N1-N3, N5, N7) and expert panels (N2, N3). At the regime level, actors from all subsystems either conduct studies about food system sustainability themselves (R12, R16, R28, R32, R33) or in co-production with municipal authorities (R24 with R28), with universities, or with other research institutes (R14, R22, R32).

Interviewees identified a lack of knowledge about food and the food system, especially of food citizens. Several interviewees noticed a decrease in citizens' food literacy (e.g., cooking skills (N6, N8)) as well as in knowledge on seasonality (N8), origin (N1, N4, R21), and food quality (N4, N8). Niche interviewees sense barriers towards (co-)learning in scarce financial and time resources (N1, N2, N10) as well as in the inability to limit knowledge production to the most relevant topics (N1, N2, N4). Niche and regime actors from the resource and governance subsystems (N1-N4, N6-8, R14, R22, R28) perceive that especially educational institutions, politicians, media, and other powerful actors have the potential and the responsibility to raise more awareness towards food and the food system. However, interviewees (N1-N5, R14) even named the production of questionable knowledge by media as a significant barrier. Moreover, one interviewee (N5) stressed that lobbyists influence knowledge production (e.g., by granting financial support to educational organizations). Finally, several interviewees from the resource subsystem (N1-3, N7, N8, R14, R21) criticized regime actors, such as retailers, the food industry, and restaurateurs, for their "greenwashing" strategies (e.g., manipulative advertising, misinformation) and their unwillingness to provide knowledge about food quality, origin, and seasonality.

Discussion

In the following section, we deepen the understanding for integrating the niche and the regime perspectives to transformation pathways towards more FD in Vienna by implementing the proposed framework. Drawing on the theory of change, our results show that niche and regime coalitions can support FD by contributing to a sustainable transformation of the food system. In line with Feola (2020), we argue that ignoring regime actors and prevailing capitalist structures may constrain rather than support the analysis of FD and the transformation towards food system sustainability. Furthermore, as the food system is expected to reflect and reinforce those actors' interest with power, including regime actors may support to what extent, FD will follow a sustainable, transformative pathway (Anderson et al. 2019). However, (food) regimes should not be studied as a homogeneous entity where all actors have similar interests, values, and goals. At the regime level, actors from the resource subsystem may be market-oriented. In contrast, others, particularly from the governance, information, and consumer subsystems, have a stronger focus on social aspects (e.g., NGOs, research institutions, municipal authorities). The latter may be especially willing to partly change the (food) system's capitalistic structures towards a democratic and sustainable food system. We can confirm that actors at both niche and regime levels may contribute to the four FD dimensions through our analytical perspective on FD.

Regime actors may contribute to FD by increasing the amount of available and affordable sustainable food (e.g., organic food) for citizens (Hamilton 2005; McFadden and Stefanou 2016; van de Griend et al. 2019) due to their advantage at reducing prices (Howard 2016), and by promoting the re-localization of food provision. Interest groups, NGOs and, municipal authorities also advocate for and support an environmentally sustainable food provision. In Vienna, municipal authorities especially contributed to integrating an organic food share and reducing food waste in public food procurement and supported food citizens to create a food policy council. Thus, in line with Baldy and Kruse (2019), we argue that municipal authorities may act as agents of change towards FD and food system sustainability. However, interviewees criticized regime actors (e.g., politicians, mainstream farmers, and retailers) for being not oriented towards food system sustainability and the community good –i.e., contributing to negative impacts on the environment and society (Howard 2016). The prevailing market-orientation, capitalist alignment, and power dynamics of some regime actors may hinder the fundamental change of established structures, processes, and practices in the food system (Lang 1999; Hassanein 2003; Howard 2016; Feola 2020). In line with Darnhofer et al. (2012), we agree that these regime actors may face difficulties when trying to overcome established regime structures and dynamics to promote the food system's transformation. In contrast, niche actors seem to generally follow universalism values, showing an orientation towards sustainability principles. Yet, as highlighted in literature, niche actors have difficulties including disadvantaged groups and minorities in their strategies (Campbell 2004; Hamilton 2005; Sonnino 2013).

Results show that the efficacy of niche and regime actors' efforts towards FD and food system sustainability is perceived to be lowered by a capitalist price policy, by "greenwashing" strategies, and by the misuse of power at the regime level. Furthermore, regime actors' (e.g., mainstream farmers, educational and public institutions, municipal authorities) financial and/or structural dependencies of other superordinate organizations impede their performances towards FD. Clapp and Fuchs (2009, p. 11) highlighted that further analysis at a broader socio-political context needs to pay attention to national and global corporations' role in food governance and their efforts to influence the public discourse. At the niche level, actors tackle a lack of efficacy by professionalizing internal structures and by out- and up-scaling their innovations. However, internal and external spatial, societal, and political barriers hinder their efforts. Following Gugerell and Penker (2020), we confirm that niches develop either towards adapting to the regime, staying independent from the regime, or nudging the regime by providing alternative solutions. These development paths towards the regime may determine niche efficacy. Niche actors aiming to nudge the regime might have high efficacy. The efficacy of niches opting to stay independent from the regime might be low due to their limited range within the food system. An adaption to regime structures could also transform niche innovations into regime actors' marketing products/business models. Mainstreaming niches might become competitive with the regime, yet their ability to change the regime and contribute to FD might remain limited (Smith and Raven 2012).

Our study illustrates that niche and regime actors' contributions and their cross-level collaborations may enhance a more democratic (urban) food system. Niche interviewees highlighted the need for collaborations with regime actors to up-scale their innovations. Our results indicate that institutional, social, and resource collaborations are crucial to fostering innovation at the niche level. Moreover, institutional cross-level collaborations promote the integration of sustainable innovations at the regime level. Therefore, our results align with Norwood (2015) and Friedrich et al. (2019), who indicate the importance of cross-level collaborations to push each other towards food system sustainability. Overall, cross-level collaborations towards FD may be challenging due to varying structures, values, and goals at different levels. It seems that there is a certain degree of tolerance among actors at the regime and the niche level that allows them to develop side by side. However, this tolerance may not be enough to transform the structure of the food system.

To support the transformation of the food system and move towards FD, food actors and citizens need to become more knowledgeable about food and the food system (Hassanein 2003; Levkoe 2006). Our results highlight that niche and regime actors (co-)produce and exchange different forms of knowledge (i.e., strategic, scientific, experiential), which enables the integration of multiple perspectives towards co-learning and decision-making within the food system (Freire 2000 in Adelle 2019). However, according to interviewees, citizens' level of food literacy is decreasing. Our results pinpoint a lack of sufficient information about food (e.g., through labeling) within the food system (Hamilton 2005; McFadden and Stefanou 2016; van de Griend et al. 2019). In this study, we found that retailers, the food industry, and restaurateurs still lack transparency and are unwilling to share specific knowledge (e.g., food quality and origin). In contrast, several regime actors and most niche actors actively contribute to co-learning processes with citizens and other food actors, widening their knowledge about food and the food system and thus contributing to FD (Hamilton 2005; van de Griend et al. 2019).

Conclusion

In this paper, we attempt to show the importance of analyzing FD from an MLP. Our framework allows us to better conceptualize FD by redefining its dimensions and including the food system’s niche and regime levels. Furthermore, our conceptual framework could provide an orientation for local governments within the context of the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact to identify food actors’ potential contributions and impediments on the road towards FD. However, the conceptualization of FD still needs further specification—e.g., a deeper understanding of the concept of “community” is still needed to include minorities and disadvantageous groups, the role of women, and cultural differences. Being largely excluded from political participation, especially the different food consumption behaviors and preferences of people of foreign origin are underrepresented within the VUFS. The importance of distinct FD aspects may vary in different local and trans-local contexts, especially in the Global South. Further research should expand the conceptualization of FD and analyze contextual differences.

This study shows that food actors at both the niche and regime level may contribute to FD’s four dimensions. Yet, our analysis confirms that FD’s main goal is still to be accomplished: the transformation of established structures within the food system (Lang 1999; Hassanein 2003). Food systems seem to be shaped by a hegemonic capitalist framework mainly characterized by self-enhancement values. This embeddedness might hinder actors willing to transform the structures in the food system. Furthermore, actors at the regime level may only tolerate changes as long as their position is maintained. However, the transformation of dominant structures in the food system may be achieved by smaller and on-going changes; rather in an open-ended search process than through a once-in-a-life-time revolution towards a clear state of FD. Therefore, developing an orientation towards food system sustainability, improving efficacy, encouraging (co-)learning processes, and fostering collaborations at the niche and the regime level is critical for a long-term and large-scale transformation of the food system towards FD.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the authors. The data are not publicly available due to the fact of privacy restrictions.

Notes

MLP differentiates three levels to understand the complex interacting developments in the food system (Geels 2002; Smith 2007): (i) Landscape includes trends that shape the food system (e.g. environmental and demographic change); (ii) the regime is characterized by stable rules and institutions that govern the structure of food provision and consumption and, (iii) niches are places for experimentation protected from the pressures of the dominant food regime.

The Milan Urban Food Policy Pact is an international pact that aims at developing sustainable food systems and promoting healthy diets (https://milanurbanfoodpolicypact.org).

The Organic Cities Network aims at public engagement in organic food (IFOAM 2018).

Vienna’s food policy council is a civil society association (https://ernaehrungsrat-wien.at/).

The term “actors” refers to discrete individuals, corporate or collective social units, e.g. people in a group, companies, public service agencies in a city or nation states in the food system (Wasserman and Faust 2007).

Knowledge democracy advocates for knowledge as a powerful tool for action and promulgates knowledge sharing (Tandon et al. 2016).

Abbreviations

- EU:

-

European union

- FD:

-

Food democracy

- MLP:

-

Multi-level perspective

- NGO:

-

Non-governmental organization

- VUFS:

-

Vienna’s urban food system

References

Anderson, C.R., J. Bruil, M.J. Chappell, C. Kiss, and M.P. Pimbert. 2019. From Transition to Domains of Transformation: Getting to Sustainable and Just Food Systems through Agroecology. Sustainability 11 (19): 5272. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195272.

Baldy, J., and S. Kruse. 2019. Food democracy from the top down? State-driven participation processes for local food system transformations towards sustainability. Politics and Governance 7 (4): 68–80. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i4.2089.

Benz, M. 2019. Die meisten Wiener leben in einer geförderten Wohnung. Was paradiesisch klingt, taugt dennoch nicht als Vorbild in der Wohnungspolitik. Neue Züricher Zeitung.

Bernard, H. R. 2006. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Altamira Press.

Bornemann, B., and S. Weiland. 2019. Empowering people—Democratising the food system? Exploring the democratic potential of food-related empowerment forms. Politics and Governance 7 (4). doi:https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i4.2190.

Caldwell, R. 2003. Models of change agency: a fourfold classification. British Journal of Management 14 (2): 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00270.

Campbell, M.C. 2004. Building a common table: The role for planning in community food systems. Journal of Planning Education and Research 23 (4): 341–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456x04264916.

Canal Vieira, L., S. Serrao-Neumann, M. Howes, and B. Mackey. 2018. Unpacking components of sustainable and resilient urban food systems. Journal of Cleaner Production 200: 318–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.283.

Carlson, J., and Chappell, M.J.. 2015. Deepening food democracy. The tools to create a sustainable, food secure and food sovereign future are already here - deep democratic approaches can show us how: Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy.

Clapp, J., and Fuchs, D. 2009. Agrifood corporations, global governance and sustainability: A framework analysis. In Corporate power in global agrifood governance. U.S.A.: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Darnhofer, I., Gibbon, D. and Dedieu, B. 2012. Farming systems research: an approach to inquiry. In Farming Systems Research into the 21st Century: The New Dynamic, 3–32. Dordrecht, Heidelberg, New York, London: Springer.

Davies, A.R., A. Cretella, and V. Franck. 2019. Food sharing initiatives and food democracy: Practice and policy in three European cities. Politics and Governance 7 (4): 8–20. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i4.2090.

Ericksen, P.J. 2008. Conceptualizing food systems for global environmental change research. Global Environmental Change 18: 234–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.09.002.

Feola, G. 2020. Capitalism in sustainability transitions research: Time for a critical turn? Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 35: 241–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.02.005.

Freire, P. 2000. Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 30th. Anniversary. New York: Continuum.

Friedrich, B., S. Hackfort, M. Boyer, and D. Gottschlich. 2019. Conflicts over GMOs and their contribution to food democracy. Politics and Governance 7 (4): 165–177. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i4.2082.

Gajda, R. 2004. Utilizing collaboration theory to evaluate strategic alliances. American Journal of Evaluation 25 (1): 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/109821400402500105.

Geels, F.W. 2002. Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: a multi-level perspective and a case-study. Research Policy 31 (8): 1257–1274. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00062-8.

Gugerell, C., and M. Penker. 2020. Change agents’ perspectives on spatial–Relational proximities and urban food niches. Sustainability 12 (6): 2333. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062333.

Guo, C., and M. Acar. 2016. Understanding collaboration among nonprofit organizations: Combining resource dependency, institutional, and network perspectives. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 34 (3): 340–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764005275411.

Hamilton, N. D. 2005. Food democracy II: Revolution or restoration? Journal of food law and policy 13.

Harvey, D. 2006. The Limits to Capital. London, New York: Verso.

Hassanein, N. 2003. Practicing food democracy: a pragmatic politics of transformation. Journal of Rural Studies 19: 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0743-0167(02)00041-4.

Hassanein, N. 2008. Locating food democracy: Theoretical and practical ingredients. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition 3 (2–3): 286–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/19320240802244215.

Hermans, F., D. Roep, and L. Klerkx. 2016. Scale dynamics of grassroots innovations through parallel pathways of transformative change. Ecological Economics 130: 285–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.07.011.

Hölscher, K., J.M. Wittmayer, and D. Loorbach. 2018. Transition versus transformation: What’s the difference? Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 27: 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2017.10.007.

Howard, P. H. 2016. Concentration and Power in the Food System. Who Controls What We Eat? In Contemporary food studies: economy, culture and politics, 1–16. London (UK): Bloomsbury Academy.

IFOAM. 2018. Organic cities & IFOAM EU join forces to bring organic on every table in Europe. https://www.bioecoactual.com/en/2018/02/19/organic-in-every-table/. Accessed 14 July 2020.

Johnston, J., A. Biro, and N. MacKendrick. 2009. Lost in the supermarket: The corporate-organic foodscape and the struggle for food democracy. Antipode 41 (3): 509–532. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2009.00685.x.

Kohlbacher, J., and U. Reeger. 2020. Chapter 6: Globalization, immigration and ethnic diversity: the exceptional case of Vienna. In Handbook of Urban Segregation, ed. S. Musterd, 101–117. UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Lang, Tim. 1999. Food policy for the 21st century. In For Hunger-Proof Cities: Sustainable Urban Food Systems, ed. M. Koc, R. MacRae, L.J.A. Mougeot, and J. Welsh, 216–224. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre Books.

Lang, T. 2005. Food control or food democracy? Re-engaging nutrition with society and the environment. Public Health Nutrition 8 (6A): 730–737. https://doi.org/10.1079/phn2005772.

Lang, T., D. Barling, and M. Caraher. 2009. Food Policy. Integrating Health, Environment and Society. New York: Oxford University Press.

Larson, A. 1992. Network dyads in entrepreneurial settings: A study of the governance of exchange relationships. Administrative science quarterly: 76–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2393534.

Levkoe, C.Z. 2006. Learning democracy through food justice movements. Agriculture and Human Values. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-005-5871-5.

López Cifuentes, M., Freyer, B., Sonnino, R. and Fiala, V. submitted for publication. Embedding sustainable diets into urban food strategies: A multi-actor approach. Geoforum.

MA17. 2019. Migrantinnen und Migranten in Wien. https://www.wien.gv.at/menschen/integration/pdf/daten-fakten-migrantinnen.pdf. Accessed 02 DeC 2020.

McFadden, B.R., and S. Stefanou. 2016. Another Perspective on understanding food democracy. Choices. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.232078.

Moore, M.-L., and F. Westley. 2011. Surmountable chasms: Networks and social innovation for resilient systems. Ecology and Society. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03812-160105.

Morgan, K., and R. Sonnino. 2008. The School Food Revolution: Public Food and the Challenge of Sustainable Development. London: Earthscan.

Noe, E., and H.F. Alrøe. 2015. Sustainable agriculture issues explained by differentiation and structural coupling using social systems analysis. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 35 (1): 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-014-0243-4.

Norwood, F.B. 2015. Understanding the food democracy movement. Choices. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.212510.

OECD. 2018. Working Together for Local Integration of Migrants and Refugees in Vienna, ed. OECD Publishing. Paris.

Oliver, C. 1990. Determinants of interorganizational relationships: Integration and future directions. Academy of Management Review 15 (2): 241–265. https://doi.org/10.2307/258156.

Ostrom, E. 2009. A General framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 325 (5939): 419–422. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1172133.

Pfeffer, J., and Salancik, G.R. 2003. The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective. Stanford University Press.

Pimbert, M. P., Thompson, J., Vorley, W.T., Fox, T., Kanji, N., and Tacoli, C. 2001. Global restructuring, agri-food systems and livelihoods: International Institute for Environment and Development.

Prost, S., Crivellaro, C., Haddon, A., and Comber, R. 2018. Food democracy in the making. Paper presented at the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, Canada,

Raymond, C.M., I. Fazey, M.S. Reed, L.C. Stringer, G.M. Robinson, and A.C. Evely. 2010. Integrating local and scientific knowledge for environmental management. Journal of Environmental Management 91 (8): 1766–1777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.03.023.

Renting, H., M. Schermer, and A. Rossi. 2012. Building Food Democracy: Exploring Civic Food Networks and Newly Emerging Forms of Food Citizenship. The International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food 19 (3): 289–307.

Rip, A., and R. Kemp. 1998. Technological change. In Human Choice and Climate Change, ed. Steve Rayner and Elisabeth L. Malone, 327–399. Columbus, OH, USA: Battellle Press.

Schwartz, S.H. 2006. Value orientations: Measurement, antecedents and consequences across nations. In Measuring Attitudes Cross-Nationally: Lessons from the European Social Survey, ed. Roger Jowell, Caroline Roberts, Rory Fitzgerald, and Gillian Eva, 169–203. London, U.K.: Sage Publications Inc.

Sieveking, A. 2019. Food policy councils as loci for practising food democracy? Insights from the case of Oldenburg, Germany. Politics and Governance. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i4.2081.

Smith, A. 2007. Translating sustainabilities between green niches and socio-technical regimes. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 19 (4): 427–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537320701403334.

Smith, A., and R. Raven. 2012. What is protective space? Reconsidering niches in transitions to sustainability. Research Policy 41 (6): 1025–1036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.12.012.

Sonnino, R. 2009. Feeding the city: Towards a new research and planning agenda. International Planning Studies 14 (4): 417–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563471003642795.

Sonnino, R. 2013. Local foodscapes: place and power in the agri-food system. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section b: Soil & Plant Science 63 (sup1): 2–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/09064710.2013.800130.

Sonnino, R., and T. Marsden. 2006. Beyond the divide: rethinking relationships between alternative and conventional food networks in Europe. Journal of Economic Geography 6 (2): 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbi006.

Tandon, R., W. Singh, D. Clover, and B. Hall. 2016. Knowledge democracy and excellence in engagement. IDS Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.19088/1968-2016.197.

van de Griend, J., J. Duncan, and J.S.C. Wiskerke. 2019. How civil servants frame participation: Balancing municipal responsibility with citizen initiative in Ede’s food policy. Politics and Governance 7 (4): 59–67. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i4.2078.

Wasserman, S., and K. Faust. 2007. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge University Press.

Wilkins, J.L. 2005. Eating right here: Moving from consumer to food citizen. Agriculture and Human Values 22: 269–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-005-6042-4.

Wood, E. M. 2000. The agrarian origins of capitalism. In Hungry for Profit. The Agribusiness Threat to Farmers, Food and the Environment, eds. Fred Magdoff, John Bellanmy Foster, and Frederick H. Buttel. New York: Monthy Review Press.

Yin, R.K. 1994. Case Study Research Design and Methods: Applied Social Research and Methods Series, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all interviewees and focus group participants for their contribution. We are particularly grateful for Christina Roder's editing support and Marianne Penker and Bernhard Freyer's feedback.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna (BOKU). The Vienna Science and Technology Fund (ESR17042), Austria, has financed this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Equally contributing authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Interviewees and focus group participants signed a consent form agreeing to the anonymous publication of data.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

López Cifuentes, M., Gugerell, C. Food democracy: possibilities under the frame of the current food system. Agric Hum Values 38, 1061–1078 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-021-10218-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-021-10218-w