Abstract

In this paper, we examine diverse political philosophical conceptualisations of justice and interrogate how these contested understandings are drawn upon in the burgeoning food justice scholarship. We suggest that three interconnected dimensions of justice—plurality, the spatial–temporal and the more-than-human—deserve further analytical attention and propose the notion of the ‘justice multiple’ to bring together a multiplicity of framings and situated practices of (food) justice. Given the lack of critical engagement food justice has received as both a concept and social movement in the context of the United Kingdom (UK), we draw upon empirical research with practitioners and activists involved with heterogenous food movements working at the local, regional and national level and apply the justice multiple concept to the interview data. We highlight the diverse ways that justice is discussed in terms of access, fairness, empowerment, rights and dignity that reflect established organisational discursive framings and the fragmented nature of food system advocacy and activism. Based on this insight, we argue that a plurivocal, relational conceptualisation of socioecological justice can help enhance the multiple politics of food justice, pluralise UK food movement praxis and nurture avenues for broader coalition-building across the food system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The notion of food justice has increasingly been evoked by various civil society groups as a powerful mobilising concept in the United Kingdom (UK) context. This has primarily occurred as a direct consequence of the ongoing impacts of austerity and welfare reform which has witnessed the proliferation of hunger and poverty (Just Fair 2014; O’Hara 2014; Nourish Scotland and the Poverty Truth Commission 2018; End Hunger UK 2019; MacLeod 2019; Raj 2019). However, despite this recent intensification of the politicisation of food-related inequities, we argue that ‘justice’—as a contested idea and practice—in food justice deserves far greater critical scholarly and activist attention by those involved with heterogenous UK food movements.Footnote 1 Indeed, the ways in which food justice is deployed in the UK have evaded critical scrutiny (however, see Tornaghi 2016; Kneafsey et al. 2017; Herman and Goodman 2018; Mama D and Anderson 2018), particularly the complex translation politics of drawing upon a concept that has deep situated roots in environmental and social justice movements of the United States (US). This raises the potential issue of mislabelling food-related activities that neglect addressing class and racial injustice (Slocum 2018) or stretching the concept to empty signifier status when applied to different contexts (Heynen et al. 2012), which can ultimately depoliticise activism and stymie marginalised voices.

While justice is open to multiple interpretations, food justice activism in the US has placed racial equity and racial justice (rooted in civil rights and environmental justice struggles) at the heart of its praxis (Alkon and Norgaard 2009; Alkon and Agyeman 2011; Myers and Sbicca 2015; Reynolds and Cohen 2016; Penniman 2018). Critical race theory has been central in grounding ideas of (abstract) justice through an intersectional analysis (of class, race, gender, (dis)ability and sexuality) that contextualises processes of domination and resistance within a broader socio-historical framework (Alkon and Agyeman 2011; Agyeman and McEntee 2014; Cadieux and Slocum 2015; Penniman 2018). Food justice scholar-activists/activist-scholars therefore start from the position of a normative commitment to justice that emphasises the necessity of reconfiguring socioecological relations and enacting structural change, while acknowledging that how justice is articulated and utilised will reflect place-based grounded concerns (Cadieux and Slocum 2015) often occupying a spectrum ranging from ‘progressive’ to ‘radical’ approaches (Holt-Giménez and Shattuck 2011). The ongoing tensions between the emancipatory potential of food justice activism and neoliberal constraints have been widely documented, particularly the tendency of food movements to prioritise entrepreneurial, market-centric strategies for social change (Alkon 2014). Furthermore, the over-reliance on volunteerism, self-exploitation and grant funding, and the reproduction of (race, class and gender) privilege within community groups and food justice organisations have been extensively critiqued (see, for example, Guthman 2008; Alkon and Mares 2012; McClintock 2014; Montalvo 2015; Broad 2016).

In the UK, there is a long and vibrant history of social justice activism led by marginalised groups tackling inequality, poverty and injustice, in which food has often played an important role (Sutton 2016). While actually existing food movements are multifaceted, fluid and fragmented with diverse and frequently contrasting priorities, contemporary UK food-related issues have been approached through two broad avenues. First, those engaging with food politics have gravitated towards the (re)connections between food production and consumption through various food ‘qualities’ (such as local, slow and organic) often related predominately to health and environmental sustainability objectives (Kneafsey et al. 2017). Consequently, mainstream environmentally-orientated food activism in the UK has tended to be dominated by white, middle-class consumers concentrating on the development of local food systems and individualised consumptive logics of social change that reinforce social privilege and fail to address the underlying structural causes of food injustice (Paddock 2016).

Second, issues of food poverty since the 2007–8 financial crisis have been framed through a predominately social welfare lens, focusing on food insecurity (Dowler and Lambie-Mumford 2015) and the contested spaces of food banks (Williams et al. 2016). Growing attention has been placed on the underlying issues driving people towards food charity (cf. Poppendieck 1998; Caraher and Furey 2018; MacLeod 2019), principally income inequality, the rising cost of living and punitive welfare restructuring (which has reduced social security entitlements and intensified conditionality) under the “alchemy of austerity” (Clarke and Newman 2012, p. 300). The cross-cutting nature of food and the stark ‘visibility’ of food poverty in contemporary UK society has acted as a catalyst for anti-hunger activism to increasingly frame its advocacy through a (rights-based) social justice, rather than charity, framework (End Hunger UK 2019). However, despite calls to develop integrated socioecological approaches to food system problems (Holt-Giménez 2011), in practice tensions persist between anti-hunger activism (focusing primarily on social justice concerns) and ‘alternative’ food movement practices (which prioritise environmental sustainability issues), thus impeding the possibilities of nurturing food justice for all.

The aim of this paper is to examine through an explicit pluralised justice lens the heterogenous actually existing forms of everyday food activism and advocacy in the UK. We do this by uncovering and bringing into conversation diverse voices of people working to address various inequalities throughout the food system and unpack the ideas of justice which underpin their work. This is significant, as the utilisation of a particular theory of justice to frame food system inequalities can open up or foreclose other ideas, visions and practices for emancipatory change (see Allen 2010; Harrison 2014; Dieterle 2015; Broad 2016). Informed by US food justice literature (Alkon and Agyeman 2011; Cadieux and Slocum 2015; Alkon and Guthman 2017; Sbicca 2018), we aim to identify the fusion and friction points in nurturing a multiscalar, reflexive and politicised UK food justice movement that addresses structural processes of power, privilege and oppression (Young 1990; Fraser 2008). It is hoped that this intervention will ignite a lively debate about the politics of UK food justice amongst scholar-activists, organisers, eaters and workers in the context of manifold contemporary socioecological crises that are produced or exacerbated by the global, industrialised food system.

The paper begins with a critical examination of the political theory of justice whereby consideration is given to three key dimensions—plurality, spatial–temporal and more-than-human—to elucidate the depth and breadth of the concept. We examine how these conceptualisations of justice have been utilised in the established food justice literature and argue for greater critical engagement to expand further the geographies, scales and subjects of food justice. We then proceed to present the empirical material of the paper, paying particular attention to how ‘justice’ is articulated and deployed by activists and practitioners working across the food system drawing upon 30 in-depth interviews. The final section of the paper critically reflects on what is gained or lost by adopting a broader (or plurivocal) ‘justice multiple’ approach to food justice praxis and outlines avenues for future research.

Interrogating political theories of ‘justice’ in food justice

Recent calls for greater clarity in relation to how food justice is conceptualised and practiced (Sbicca 2012; Cadieux and Slocum 2015) highlights the importance of bringing food justice into conversation with diverse literature from political philosophy that critically engages with the contested notion of justice (Dieterle 2015; Barnhill and Doggett 2018). In this section, we unpack three broad dimensions of justice – plurality, the spatial–temporal and the more-than-human—which we argue are crucial to expand, deepen and enrich the ways justice is conceptualised and intersects with food system issues. As Dixon (2014, p. 175) states, learning to enact food justice first necessitates that the lens of justice is attuned and refined in order to “see”, unpack and address multiple forms of inequality. We therefore conclude this section by advancing the notion of the ‘justice multiple’ to incorporate a diversity of justice framings, which are shaped by various spatial, temporal and scalar relations, to provide a basis to examine the heterogenous justice claims of UK food movement practitioners and activists.

Pluralising justice: distribution, recognition, participation and enhancing capabilities

In order to carefully consider the fundamental justice principles that inform the conceptual foundation of food justice, we begin by discussing the central dimension of distributive justice. Broadly speaking, the majority of Western liberal political philosophical writing on justice has been preoccupied with the notion of distributive justice in relation to the allocation of benefits and burdens between different individuals and groups, with focus placed on (abstract) fairness and impartiality. In this context, social justice is defined as the “standard whereby the distributive aspects of the basic structure of society are to be assessed” (Rawls 1971, p. 9). The importance placed on distributive elements of food justice is demonstrated by the definition put forward by Gottlieb and Joshi (2010, p. 6) in their seminal scholarly text, as “ensuring that the benefits and risks of where, what, and how food is grown and produced, transported and distributed, and accessed and eaten are shared fairly”. Given the complexity and intersectional nature of oppression that permeates food systems entangled with neoliberal capitalism, systemic racism and heteropatriarchy, scholar-activists contend that addressing distributional injustices in isolation (frequently framed in terms of ‘access’) is insufficient to tackle complex food inequalities. Therefore, relational difference and politicised actions that are transformative of oppressive structures must be positioned at the heart of food justice (Cadieux and Slocum 2015; Sbicca 2018; Slocum 2018). This underscores a more pluralistic, embodied and less universalistic notion of justice.

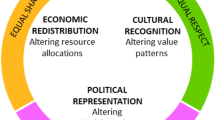

Political theorists who have critically examined the plurality of justice, such as Young (1990), Fraser (1997, 2008), Schlosberg (2007) and Sen (2009), have drawn heavily upon the praxis of social movements to develop their respective theories of justice by observing the complex relations of oppression and processes of inequality that contextualise our lifeworld, rather than relying on depersonalised idealised abstraction. This vividly highlights the symbiotic relationship between multidimensional justice theory and diversified social movement practice. Drawing upon the embodied justice claims of marginalised groups, Fraser (2005, 2008) understands justice as parity of participation, incorporating three dimensions: redistribution (socioeconomic), recognition (cultural-legal) and representation (political). This framework corresponds to the questions of what counts as a matter of justice, who counts as a subject of justice, and how justice claims are defined and determined. Similarly, Young (1990) advocates for a theory of justice grounded in the everyday practices of emancipatory social movements that endeavour to tackle systems of oppression. For Young (1990, p. 37), oppression is defined as “the institutional constraint on self-development” and is characterised by “five faces”: exploitation, marginalisation, powerlessness, cultural imperialism and violence—all of which need to be addressed in relation to the food system to create more just and socioecologically sustainable relations (Slocum 2018).

The work of Fraser (1997; Fraser and Honneth 2003) is particularly important for explicating the politics of recognition—a traditionally under-theorised dimension of justice in political theory. Fraser (1997) contends that recognition is both an important dimension of justice and a prerequisite for fair distribution, in which misrecognition (or lack of respect) is structural, social and symbolic—that is, a cultural and institutional form of injustice, or a “status injury”. In the context of food systems, recognitional injustices are rendered visible in the ways in which indigenous communities and marginalised groups have been historically subjected to cultural and political domination, discrimination and disrespect that disrupts or devalues traditional foodways (Mares and Peña 2011). Addressing such issues requires communities to exercise their right to determine their own food systems through collective leadership and participation in decision-making processes (Penniman 2018), challenging the norms and practices that (re)produce and legitimise inequality (Fraser and Honneth 2003) and nurturing political consciousness—or conscientisation (Freire 1970) – through critical food systems education that respects diverse knowledge systems.

Procedural or participatory justice (Loo 2014) is therefore crucial, as mere inclusion in decision-making processes is not enough—emancipatory strategies are needed to empower citizens, and in particular, the most marginalised communities. As Young (1990) has posited, in order for a policy to be just everyone in principle should be able to express their needs and have an effective voice in its deliberation. However, the traditional processes of formulating food and agricultural policy, particularly in the UK, and the European Union more broadly through the Common Agricultural Policy, have been highly asymmetrical, reflecting the vested interests of agribusiness (Lang et al. 2009). Procedural justice, therefore, emphasises the importance of participatory policy-making and democratic governance that enables the most marginalised to challenge elite control over policy development and pluralise the voices that shape (food) governance processes.Footnote 2

Collectively, these diverse justice insights (Young 1990; Fraser 1997, 2008; Loo 2014) provide the foundation for a pluralised conceptualisation of food justice, which is not based on the top-down application of abstract norms, but enacted in situated contexts in response to multidimensional, embodied injustices. Elucidating this point further, pragmatically focusing on addressing what Sen (2009, p. ix) terms remediable injustices in our everyday lives, does not rely on constructing a theory of “perfect justice” to evaluate unjust institutional and social relations. Rather, realising justice entails identifying and addressing inequalities “around us which we want to eliminate” (Sen 2009, p. vii). Indeed, any ideals of justice (however framed) need to be practiced (or performed) often in messy, ongoing, quotidian ways that seek to heal and repair in our imperfect world.

Developing the “capabilities approach” to justice, Sen (1999) argued Rawls (1971) ultimately failed to acknowledge that people are unable, for multiple reasons, to translate available primary goods into actual welfare-enhancing opportunities. Justice, therefore, requires bolstering basic entitlements and capabilities (in terms of resources, freedoms, opportunities and institutions) that people require to be full members of society. While the state clearly plays a key role ensuring that citizens have the capabilities to live meaningful lives, it is posited that the capabilities approach can strengthen rights-based frameworks of justice by moving focus away from ‘rights’ understood as simply abstract, formal, legal entitlements towards the ways in which grassroots collectives exercise those rights in everyday, situated practices. This reflects a “human rights enterprise” from below (Armaline et al. 2015, p. 14) through interconnected translocal micro-resistances. In this respect, forging cooperative relations of solidarity with those in other localities is crucial in order to create multiscalar geographies of food justice to nurture trajectories for socioecologically just futures. In the next section, we explicate the multiscalar spatial and temporal dimensions of justice in greater depth.

Expanding justice across space and time: global duties, obligations to distant others and intergenerational rights

The Westphalian conceptualisation of justice embodied in the work of Rawls has been critiqued for problematically focusing exclusively on the nation-state to the detriment of a multiscalar justice perspective (Caney 2005; Fraser 2005, 2008). Several theorists have argued for extending the Rawlsian conception of justice as fairness beyond state borders (Pogge 1989) to account for the contemporary realities of intensified globalisation and pervasive worldwide poverty to determine our duties and obligations of justice in relation to principles of global distributive justice (Pogge 2002). This tends to appeal to the basic liberal idea that all humans hold the same moral worth and value. Accordingly, our justice obligations transcend socially constructed territorial boundaries (Caney 2005), in which our embeddedness within globally interconnected social structures creates an interdependence of shared political responsibility to address injustices (Young 2011).

As Fraser (2008) argues, however, focusing merely on distributive (global) justice fails to comprehend the diverse dimensions and competing geographical scales of justice that entangle ‘global’ and ‘local’ ordinary-political injustices. Thus, any multiscalar understanding of justice must take into account the relational ways (in)justice is produced and performed across various spatial “power geometries” (Massey 1994). Food justice is consequently always a matter of sociospatial justice which requires “new ways of thinking about and acting to change the unjust geographies in which we live” (Soja 2010, p. 5). Food justice praxis therefore implicitly recognises the inherent multiscalar sociospatial organisation of food systems and the complex translocal power relations that shape (fluid) foodscapes in which injustice is always experienced in situated contexts by particular communities (Slocum et al. 2016). To be sure, the “scales of spatial justice are not separate and distinct; they interact and interweave in complex patterns” (Soja 2010, p. 46). Connecting different ‘local’ issues of food (in)justice can contribute to the advancement of collective justice by scaling up and across efforts at the institutional level of (food) policy and strengthen coalition networks at multiple scales (Sbicca 2018). This requires (re)focusing attention to shared experiences of structural inequality, moving beyond what Harvey (1996, p. 40) termed “militant particularisms”, and constructing pluralistic and heterogeneous coalitions between diverse organisations and social movements across space. However, compared to the multiscalar food sovereignty movement (under the auspices of La Vía Campesina), food justice activism has tended to place less explicit emphasis on translocal solidarity processes for global justice (Slocum 2018).

Against this backdrop, it is asserted that linking multiscalar environmental sustainability concerns with other justice issues such as labour precarity and workers’ rights is central in order to create an effective transnational food justice movement (Myers and Sbicca 2015; Slocum et al. 2016; Sbicca 2018). The necessity to cultivate this form of integrated solidarity-building exists within a broader neoliberal political-economic context of the intensified pursuit of global labour ‘flexibility’, income insecurity, workfare policies and the fragmentation of social entitlements (Ciplet and Harrison 2020). Thus, the push for greater focus on the multiscalar sociospatial relations of translocal solidarity (Slocum et al. 2016) is crucial given that food justice scholarship draws heavily on discrete ‘local’ food projects predominately in urban contexts of the US to develop its insights (Glennie and Alkon 2018), rather than the interconnected relationality of place (Massey 1994) and the multiscalar power-geometries of food systems. The latter of which deserves far greater critical scrutiny.

Crucially, our justice obligations also extend across time looking both to past injustices to challenge historical trauma and forward with regard to future generations (Cadieux and Slocum 2015; Penniman 2018). Debates regarding intergenerational justice have unfolded in political philosophy in relation to the possibility of extending rights to future people in the context of the “non-identity problem” (see Parfit [1984] 2004). Political theorists have, therefore, increasingly advocated for a more critical and fundamental focus on the creation of intergenerationally just policies (Schuppert 2011) that safeguard peoples fundamental interests, liberties and needs across temporalities.Footnote 3 The extension of egalitarian justice to future generations can be seen as a logical result of cosmopolitan intragenerational justice theorists who argue that people’s location in space should not restrict our justice obligations (Caney 2005); accordingly, people’s position in time is equally arbitrary (Caney 2009). These insights contextualise the complex intra-/inter-generational justice issues that emerge at the socioecological intersection of a climate emergency and unsustainable food systems.

As the concept of sustainability is inherently normative, what should be sustained for future generations reflects different situated values, and consequently, is highly contested. The notion of “just sustainabilities” (Agyeman et al. 2003) emerged in relation to the environmental justice movement and has been instrumental in explicitly politicising sustainability by emphasising the necessity of simultaneously working towards social justice and environmental sustainability. While the movement has transcended narrow liberal Rawlsian interpretations of distributive justice (Walker 2009), justice continues to be predominately conceptualised in primarily anthropocentric terms. In this respect, the work of Pellow (2014) is important in extending the environmental justice framework to incorporate nonhuman actors and directing focus towards socioecological inequality across species and space. In the following section, we outline recent developments in political theory that have incorporated the more-than-human in relation to justice and highlight current food justice scholarship that is engaging with, and developing, these debates in interesting ways.

Extending justice to the more-than-human: posthuman social justice and nonhuman vitality

The conceptual separation of ‘nature’ from ‘society’ has shaped anthropocentric framings of justice that posit the social in humanistic terms that disregards nonhuman (political) agency (Latour 2005). Thus, several scholars have worked to incorporate nonhuman concerns into justice frameworks. For example, Schlosberg (2007) has argued for expanding the capabilities approach (Sen 1999; Nussbaum 2000, 2006) to the more-than-human by recognising the interconnected injustices experienced in complex relational ecologies that impede the basic capabilities and functioning of animal and plant life. Moreover, ecological justice (Baxter 2005) highlights the complex ethical and moral questions that emerge when considering nonhumans as subjects of justice. This links with the systems thinking and integrated ethical framework of earth care, people care and fair share embodied in permaculture (Holmgren 2011), which provides a socioecological lens to articulate the ecological dimensions of our understanding of social justice (Millner 2017). Indeed, recent developments in food justice scholarship have increasingly highlighted that justice-orientated claims, such as the right to food, requires operating from the position of the inextricably socionatural world we inhabit relationally with a multiplicity of others, whereby food is “constituted through material histories of human and nonhuman collaboration” (Millner 2017, p. 780).

Unlike moral philosophy (see Singer’s 1975 classic text), Western political philosophy has largely failed to reflect critically in relation to humanity’s pervasive sense of “species entitlement” (Kymlicka and Donaldson 2016, p. 692), and therefore, ascertain obstacles to improve justice for animals (however, see for example, Nussbaum 2006; Donaldson and Kymlicka 2011; Garner 2013). Political philosophy has tended to hold that nonhuman animals do not directly place justice demands on us, despite their ethical standing (Plunkett 2016). While Nussbaum (2006) endeavoured to extend the capabilities approach embodied in her cosmopolitan theory of justice to nonhuman animals and intermittently discusses the possibility for “interspecies sociability”, ultimately an anthropocentric understanding of the demos is maintained (Pepper 2016). Disrupting pervasive anthropocentric imaginaries of ‘the political’, as Kymlicka and Donaldson (2016) argue, involves asking difficult questions in relation to the potential political status of non-linguistic agents (such as sentient nonhuman animals) in terms of voice, participation and agency. Food justice scholarship, however, has generally remained conspicuously silent on how interspecies sociability can inform broader conceptions of justice in relation to food systems (however, see Millner 2017; Perz et al. 2018; Rodríguez 2018; Broad 2019).

Bringing food justice into conversation with critical animal studies provides one productive terrain to focus attention to the intersectionality of all forms of oppression including sexism, speciesism and racism (Pellow 2014; Perz et al. 2018). Unpacking the more-than-human forms of injustice embedded in the “animal-industrial complex” (Twine 2012, p. 15) that exploits animals for purposes of corporate capital accumulation and the differential ecological and social inequalities that emerge from such a system, provides one avenue to expand understandings of food justice to nonhumans. In short, it is contended that in order to hold food justice activism accountable on the ‘justice’ dimension, working towards equitable and sustainable food systems must secure justice for humans and nonhumans (Rodríguez 2018). Recent work by Broad (2019, p. 225) in relation to the intersection of animal product alternatives and food justice – what he terms “food tech justice” – provides an interesting (albeit contested) example of one agenda that seeks to explore the possibilities for “food system health, equity, and sustainability” beyond animal agriculture.

Food systems, therefore, provide a pertinent, embodied and vital lens to examine how we can/do/do not live responsibly in multispecies worlds at various ‘contact zones’—the places where species meet (Haraway 2008)—such as agrifood systems. Drawing upon insights from new materialism (Bennett 2010; Coole and Frost 2010), scholars have argued that taking the agency or vitality of nonhumans seriously (Plumwood 2001)—for example, by exposing the more-than-human agencies of soil in the politics of food systems—is crucial in order to foster more just and sustainable socioecological relations (Ferguson and the Northern Rivers Landed Histories Research Group 2016). This creates new political terrains for social transformation beyond the nature/society dichotomy in ways that expand the parameters of justice to nonhuman life.

To summarise, encouraged by Schlosberg’s (2007, p. 165) insight that “a plurality of discourses of justices is a good thing” and informed by scholar-activists who argue for a multifaceted justice lens (Sbicca 2018), in this paper we posit that plural, spatial–temporal (or intra-/inter-generational) and more-than-human conceptions of justice should be more robustly examined and fully integrated into food justice praxis. This can inform broader diverse “counter narratives” (Dixon 2014, p. 175) that expand the who and what of food justice claims and activism, and nuance how they are defined and determined (Fraser 2008), and therefore, what interventions are enacted to address “remediable injustices” (Sen 2009, p. vii). Accordingly, an understanding of the justice multiple (cf. Mol 2002) that focuses on the diverse everyday practices, experiences and understandings that are constitutive of human and nonhuman justice is useful for examining the manifold and competing rationales that shape who participates in deciding what a just food system looks like and how it can be engendered, across both space and time.

Indeed, what is ‘fair’ or ‘just’ in relation to food systems is not complete, consistent or culturally universal, but instead always partial, situated and contextually embedded, reflecting diverse values, normative ideals and priorities (Harrison 2014). Thus, in this paper we examine how food justice is interpreted, mobilised and enacted by different actors involved with heterogenous UK food movements by applying the justice multiple lens. This is crucial, we argue, given that compared to North American food studies literature (see, for example, Guthman 2008; Allen 2010; Holt-Giménez 2011; Holt-Giménez and Shattuck 2011; Broad 2016; Sbicca 2018), there is a notable paucity of critical food justice scholarship unpacking the contested terrain of UK food movements and their justice claims, which this paper seeks to address.

Researching conceptualisations of justice in UK food movements

The empirical section of this paper draws upon the findings from 30 in-depth semi-structured interviews with food movement practitioners and activists working at the local, regional and national levels across the UK. Relatively few groups explicitly frame their work as ‘food justice’ in the UK, and therefore, participants were identified through a web-based search of diverse food-related advocacy groups, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and coalition networks that are working to address various (social, economic, and environmental) injustices in the food system. A database of potential organisations was compiled based on a search of key topics, including food access, food poverty, food policy, land use, labour/work, and alternative food practices. This search captured a range of activities, projects and initiatives, concerning food security, environmental sustainability, animal welfare, and labour struggles within the food chain. Furthermore, multiple alternative food practices were identified that focus on different aspects and (contested) qualities of food such as local, organic, slow, non-genetically modified organisms (GMO) and cruelty-free.

The main aim of the interviews was to discern what activists and food movement practitionersFootnote 4 mean when they employ the concept ‘justice’ in relation to their work, and therefore, examine how different theories of justice are utilised to shape social action. Thus, interviews centred upon the meaning, relevance and content of the term ‘justice’ in relation to participants’ advocacy and everyday practices. The interviews were undertaken from February to August 2018 and each lasted between 60 and 95 min and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Of the 30 people interviewed, 12 were women and 18 men with the majority White-British, highlighting the intersectional privilege that permeates mainstream food movements. The transcripts were analysed through two rounds of thematic coding, the first to identify key themes and ascertain ideas of justice explicitly or implicitly articulated in the narratives, and the second, to refine codes related to aspects of justice identified in the literature review: redistribution, recognition, participation, capabilities, spatial (intra-generational), temporal (inter-generational), and more-than-human. The following results section is structured around the different justice themes that emerged from the analysis based on the expanded conceptualisation of the justice multiple. Quotations from the interviewsFootnote 5 are utilised to highlight the central issues and topics uncovered from the research.

Examining justice in UK food movements

Pluralising justice through rights-based approaches to food

The global food and financial crisis of 2007–8 was identified by the majority of participants as the catalyst for increased practitioner and activist interest in contemporary food system inequalities. For some anti-hunger organisations, the very presence and prevalence of emergency food aid projects and charitable welfare provision signifies a fracturing welfare system that no longer provides security for those who need it (Poppendieck 1998). This was articulated in relation to a broader critique of the current ‘austere’ political-economic context, which is fundamentally “unfair and broken” (practitioner, national food NGO; see also O’Hara 2014; Raj 2019). Yet, for those involved with charitable food projects on the ground, their everyday focus was aligned to increasing access to food to meet an immediate need drawing primarily on notions of distributive (in)justice that emphasise the unfair allocation of material foodstuffs. As a manager of a franchised food bank located in the north east of England explained, their priority was addressing acute experiences of food insecurity: “we are a first responder in many ways for that food crisis”. For some interviewees, it was much easier to identify an apparent lived form of remediable injustice (Sen 2009) such as a lack of access to food and respond to it through everyday acts of kindness, collective action or voluntarism, which they believed did not necessarily reflect expressions of ‘justice’.

Several practitioners explained that, in their experience, communities were often averse to frame or communicate inequalities explicitly in terms of (in)justice, as a policy director for a human rights and social justice charity stated, “because it is perceived as very confrontational and elitist, perhaps legalistic”. It was proposed that the notion of fairness is much more intuitive, compared to framing food inequalities as a violation of human rights. Some practitioners, therefore, argued that people should be empowered as “rights holders” (campaigns manager, social justice charity) to demand access to food and a range of other entitlements as central to living a nourished and dignified life. However, as a community activist involved with a grassroots food project stated, there is a need for a “change in culture” in how we communicate food inequalities, whereby people feel comfortable to connect and articulate food issues to vital matters of social (in)justice (Raj 2019).

For those who focused on justice, rather than the food dimension of food injustice, a lack of economic rather than physical access was conveyed as the crucial factor that impeded food security. Notably, precarious employment opportunities, in-work poverty and punitive austerity policies that underpin economic injustice were described as an inhibiting factor encumbering peoples participation in an ‘alternative’ food movement that continues to fetishize the commodification of food for profit (Agyeman and McEntee 2014). As a chief executive for a national food NGO discussed, in practice “there is a gap between the local and sustainable or seasonable produce [sector] and access for low income communities […] the sustainable food movement in Britain is just so small and niche that it struggles to provide that food at an affordable price point that’s accessible to most people”. This creates a schism between the priorities of projects focusing on the immediate provision of food and the ‘alternative’ consumptive politics that dominates environmental sustainability movements that typically discussed their social action as “reconnecting production and consumption in sustainable ways” (farmer, community-supported agriculture scheme). In terms of the latter, food movement practitioners involved with organisations and projects focusing on the creation of localised food systems tended to emphasise mainstream environmentalism priorities and overlooked or downplayed social justice considerations.

For organisations and networks that adopted an explicit food justice frame (who remain a small and fragmented minority in the UK), connecting distributive, participative and recognitional (in)justice was crucial in order to move beyond a narrow focus on food access to incorporate “individual and community empowerment, dignity and political representation to [develop] the more collective right to a fair food system” (campaigns manager, food justice organisation). This is imperative in a highly unequal society in which differences in power and recognition exclude the most marginalised from decision-making processes, as a director of a permaculture NGO stated: “where’s the political voice of those one and a half million people using food banks?”. As described by an activist involved with a grassroots food policy movement, creating a holistic framework to convene multiple interests as they relate to food is vital for exploring fusion and friction points for developing solidarity towards food justice: “How do you find the thread that links people who are using a food bank with a farmer who might also be in destitution and on the brink of having to sell up? There’s actually a certain sort of commonality between them”. In this context, identifying the structural causes of inequality (re)produced by the political economy of food, enables diverse groups to acknowledge shared injustice; particularly the corporate food regime that entangles neo-productivist logics of agricultural intensification, the commodification of the commons (such as seeds) and promotes institutionalised food aid, which constructs food poverty as a matter of individualised scarcity, rather than systemic inequity.

The notion of ‘empowerment’ in terms of how it is expressed, enacted and experienced in food-related grassroots initiatives provides a particularly contested terrain for addressing participative, recognitional and representational injustice. For example, when critically reflecting on their involvement in advocacy tackling food poverty, an empowerment programme officer for an anti-poverty project commented:

Are you truly empowering people? Or is it just a consultation that actually decisions have already been made? […] Overall, it is giving a stronger voice to those with experiences in food poverty, and understanding that they’re the real experts, in terms of the actual injustices on the ground […] people growing up in poverty are those who are continuously disempowered.

This participant emphasised the intersecting axes of difference (such as class, gender and (dis)ability) that contextualise the accumulated quotidian, embodied processes of disempowerment that some people experience over their life-course, which can have significant long-term detrimental impacts on their mental and physical health, and reinforce participatory injustice. Some NGOs have, therefore, devised strategies to nurture grassroots discussions of rights-based approaches to food justice, for example, organising participative workshops with those most absent from food system discussions, as a coordinator of a civil society coalition working for food justice described:

we’ve been working with people who are traditionally excluded from the decision-making processes and who are likely to face much more complex food justice issues. […] we’ve been listening to peoples’ food injustice experiences, and their solutions to deal with those issues […] to embed this experience into policy and law.

In particular, Kitchen Table Talks, which are informal and convivial forums for citizens to discuss food (in)justice in diverse accessible spaces (such as allotments, community food hubs and cafes) were identified as important platforms to nurture inclusive, democratic, people-centred food policymaking. The process of fostering procedural or participative (food) justice in practice can be challenging, however, as articulated by a policy manager for a food justice organisation, because “the term ‘food justice’ is still in its infancy in Scotland, and we’re continually trying to work out how we communicate these complex ideas in an accessible way that is genuinely meaningful for people”. Moreover, some practitioners acknowledged that in a sociospatial context whereby many people feel disenfranchised from mainstream politics, bringing together heterogenous voices to develop inclusive and diverse food movement politics – by reaching beyond the middle-class privilege that has tended to dominate food activist spaces and networks – can be a challenging and slow (but imperative) process to realising participatory food justice.

In relation to their everyday work practices, several participants emphasised the importance of placing dignity and respect as core principles underpinning their advocacy and basing their organisational agenda on the lived experiences of people beyond the ‘mainstream’ food movement. This is exemplified by the Menu for ChangeFootnote 6 project’s emphasis on “Cash, Rights, Food” to address the root causes of food insecurity (see MacLeod 2019, p. 7), in which women, and lone parents in particular, are disproportionately affected (Independent Working Group on Food Poverty 2016). As a campaigns manager from a food justice organisation described, “empowering communities is essential to ensure people meaningfully participate in political processes that affect their everyday lives […] based on [values of] co-production and dignity, where a holistic rights-based framework is fundamental to move towards food justice”.

Notably, the majority of participants articulated their understanding of ‘food justice’ in terms of the universal (and fundamentally anthropocentric) right to food, as stated by a practitioner working for an international anti-poverty organisation: “I think everybody should have enough to eat is a basic human right, access to food, I guess it’s a rights-based approach […] there is enough food to go around, it’s just the distribution of it is skewed”. This interviewee, along with many others, elaborated the importance of understanding distributive inequities in a global context that transcended arbitrary socially constructed boundaries as a matter of fairness (Caney 2005). This sentiment was reiterated by a director of a permaculture organisation who commented: “the issue globally is not food supply, we grow enough calories to feed everybody, the issue is food distribution” and as a small-scale farmer explained, “you have to start from the point of view that the right to sufficient, adequate and high-quality food is a basic human right”. Overall, interviewees framed the right to food in terms of fairness and equality drawing on liberal understandings of justice (as found in the work of Rawls).

In Scotland, there is growing momentum to enshrine the right to food within Scottish legislation through the Good Food Nation agenda.Footnote 7 As a campaigns manager for a food justice organisation comments, this campaigning priority was justified because: “if you don’t design a food system which is to progress people’s rights, then we will only ever be tinkering around the edges […] we’d like a framework that enables a constant progress towards the progressive realisation of the right to food”. Legislation, therefore, was viewed as a vital vehicle for establishing a core (governmental), long-term commitment towards a fair, healthy and sustainable food system, necessitating a coherent and transparent governance framework to ensure accountability based on “national and local strategies and the right to food as a minimum core obligation” (policy director, social justice charity). While the discourse of ‘rights’ challenges narratives of charitable food (aid) – and enshrining the right to food in law makes policy more resilient and robust as governments change over the political lifecycle – without undoing the structures of power that reproduce inequality, institutionalising the right to food will not guarantee that people are nourished in practice.

In this context, some interviewees discussed how a performative collective grassroots food politics of “community-led initiatives such as community gardens or like a really good community café or food cooperative that runs alongside the credit union” (organisational lead, community food NGO) often work to guarantee ‘rights’ such as access to nutritious, socially acceptable, culturally appropriate and affordable food in specific, contextual circumstances, rather than relying on the state to do so. This embodies a prefigurative “human rights enterprise” from below (Armaline et al. 2015) based on tackling hunger, food insecurity and social isolation as remediable injustices (Sen 2009), which can be addressed in the here and now through collective action, thus creating a situated sense of food justice that endeavours to nurture people’s existing capabilities (Sen 1999; Nussbaum 2000). As noted by several community activists, these grassroots practices occur in a broader context whereby the UK Government violates a range of legally required obligations to “respect, protect and fulfil” the right to food imposed by international human rights frameworksFootnote 8 (Just Fair 2014).

Enacting sociospatial (food) justice: labour rights, consumptive politics and the invisibility of workers

Embedding struggles for economic justice in the local food movement creates particular tension points between labour unions advocating for greater economic equity and those aligning with consumption-based food politics. As described by a labour activist, supporters of alternative food initiatives frequently overlook or disregard conventional food-chain workers because their labour is associated with corporate power and bolsters a socio-environmentally undesirable food system. This tension is exemplified by the McStrike campaign,Footnote 9 whereby a privileged, biopolitical consumptive imaginary pervades the mainstream food movement and artificially separates the ‘alternative’ from the ‘conventional’ food system, impeding broader support and acts of solidarity. As an economic justice campaign officer for an anti-poverty charity comments:

there is quite a big education job to get people to understand that the role of these campaigns isn’t just to direct individuals’ consumption choices, so in one way that is the failure of our food movement to successfully articulate a position that marries workers’ rights within fast food with that broader desire to transform the food system, because far too often that falls within an organic consumption, consumer-led type activity […] some of the frames within that are problematic for generating and mobilising support for it.

The relative ‘invisibility’ and the devaluing of fast food work compared to, for example, the consideration and artisan skill associated with the Slow Food movement and its focus on “good, clean, fair food” (member, Slow Food Cymru) “as the ‘gold standard’ of food preparation labour at both home and in restaurants” (Thiemann and Roman-Alcalá 2019, p. 814) works to reinforce food privilege and devalue particular forms of labour that occupies differential positions throughout the food system. Thus, as a practitioner from a food justice organisation argued, it is crucial to identify synergies between the exploitation of labour “on farms, supermarkets, slaughterhouses and restaurants, […] throughout complex supply chains” in order to position labour justice more centrally within food movement praxis. However, as a food activist described, “connecting rural and urban is a really big piece of the jigsaw that is often missing” in nurturing translocal, cross-sectoral worker solidarity.

A key aspect of economic injustice that was expressed by many participants was the prevalence of in-work poverty. As a public affairs officer for an international Christian charity stated, those working in the food sector often “can’t afford to feed themselves because they are too stretched financially”. In-work poverty currently affects four million people in the UK, the highest in 20 years (JRF 2018). Pertinently, the poverty rate is the highest for people employed in food-related industries, with 25 percent of those working in accommodation and food services and 23 percent in agriculture, forestry and fishing, categorised as living in poverty (JRF 2018, p. 36). As a director of a permaculture NGO elucidated: “There’s a huge irony that the people who are paid the least are the people who work in the food industry and that works from farmers through to the people, the cashiers, who sit on the tills, so there’s something deeply broken”. While manifestations of economic inequality that permeate the food system were broadly recognised by participants, their involvement with collective, concerted and integrated action to address labour injustices was fragmented and limited.

For some, critical food system education was imperative to enable people to (re)value agrifood labour based on nurturing political conscientisation (Freire 1970), particularly in the context of a highly industrialised society such as the UK. As described by a food activist in relation to agricultural labour, “we assign so much value and prestige to office jobs, rather than working with our hands, food production, gardening is badly paid, so low-status jobs […] it’s all about our values”. Mainstream ‘local’ food movement practitioners, however, rarely discussed equitable conditions of food-chain workers or agricultural labour, rendering multiple forms of food system labour ‘hidden’, reflecting their structural and spatial invisibility in ‘placeless’ factories or remote fields. As a labour activist involved with an anti-poverty charity asserts, food justice can only be attained by revaluing food work in all its forms, paying particular attention to those low-paid, low-skilled sectors outside the purview of ‘local food’ imaginaries: “hospitality is one of those areas with very low wages and very high uses of the most insecure types of work, often marginalised workers, whether that’s because of gender and migrant status as well”.

In the UK, the annual need for seasonal agricultural workers is a permanent occurrence, however, they are rendered provisional and transitory – the migrant precariat. As a small-scale farmer commented, “There’s been this essentially quite racist stuff about Eastern Europeans [in populist Brexit narratives] and then everyone trying to figure out ways of […] allowing Eastern European labour migration to continue despite […] not wanting it to”. While increasing emphasis has been placed on the centrality of migrant labour to UK agriculture, processing and catering, they remain largely invisible and voiceless in debates over the future of post-Brexit food policy, highlighting the participative and recognitional injustices that marginalised groups experience (Loo 2014). Indeed, given that farmingFootnote 10 in the UK is the least ethnically diverse occupation, whereby 98.6 percent are classified as White-British compared to 80.1 percent of total population share (Norrie 2017), there is a pressing need to expand solidarity of agricultural work beyond the white privilege of farm ownership (and large, corporate-focused farming unions) to the marginalised migrant workers that the agricultural system relies upon. Hence, protecting the rights of migrant workers throughout the food chain is particularly important in the context of zero-hour contracts, piecework and Brexit: “We’re really keen that migrant workers aren’t receiving different minimum wages and receiving different conditions” (policy manager, food justice organisation) and through advocacy “draw attention to the overlap between precarious work and other forms of marginalisation, whether that is race, gender or migration status, and how precarious work, works as a system to reinforce those oppressions” (economic justice campaign officer, anti-poverty charity).

Through transnational alliances for labour justice, we begin to see how responsibility for global labour justice (Fraser 2005, 2008) can be enacted. As a general secretary for a trade union involved in the McStrike describes: “the SEIU [Service Employees International Union] have been an absolute pivotal part of our campaign, because they support us, send us over trainers to show us how to organise in the fast food arena, they have brought their activists over here to stand on picket-lines and demonstrations outside different McDonalds stores, they have really been an inspiration to us”. McStrike action took place across towns and cities seeking to strengthen a fair wages movement for food workers in the UK, but also enacted in solidarity with the US living wage campaign (the ‘Fight for $15′), with a productive exchange of knowledge and capacity-building processes that were discussed as central to fostering international labour solidarity in relation to sociospatial justice (Slocum et al. 2016). Notably, a small number of participants discussed the importance of moving beyond the labour-based “militant particularisms” (Harvey 1996) that can be embodied in traditional worker organisations such as trade unions, which can impede broader coalition-building with groups campaigning for the transition to a sustainable, decarbonised economy (Ciplet and Harrison 2020). This ‘sectoral’ fragmentation can ultimately encumber struggles for radical food system transformation.

Connecting concerns for the local with the global is central to examining the injustices embedded throughout international food supply chains that transverse ‘alternative’ and ‘conventional’ food systems. As an advocacy officer for an anti-poverty organisation comments, the interconnected, multiscalar nature of food systems means that any intervention in one place must consider the (global) justice dimensions of actions within, and across, nation-state boundaries:

[a key task is] how to connect the stuff we are doing locally with the global picture […] which is looking at the treatment of people within food supply chains […]. We’ve done some research in Wales, for example, on women’s low paid sector work, of which food is one, and how to link those two things together to show that there is a price for cheap food here and there is a price globally as well […]. Even if supermarkets are paying the living wage and have decent work in the UK, it doesn’t necessarily mean that that follows all the way through their supply chains.

The limited capacity of NGOs and activists in terms of time, resources and knowledge of campaigns in other sociospatial contexts were obstacles identified by practitioners that can encumber cultivating connections of trust, solidarity and relations of translocal food justice in practice within and between countries. This demonstrates the complexity of enacting responsibility towards harms and injustices involving distant strangers (Young 2011) from the position of a progressive global sense of place (Massey 1994).

Transforming food systems through socioecological justice: extending justice to the more-than-human

For those who articulated a more-than-human conception of food justice, diverse mobilisations emerged around animal activism (particularly animal rights and animal welfare advocates) and environmental/ecological justice. The former was discussed as a moral and ethical stance towards sentient nonhuman animals and the latter rooted in concerns for the destructive impacts of industrial, chemically-intensive agriculture on more-than-human ecologies. For some participants, the complicated and uneven power relations that entangle humans with other animals creates specific ethical and justice obligations dedicated to animal liberation approaches under the “animal-industrial complex” (Twine 2012). This is embodied by veganism that frames justice in terms of animal rights: “the key thing for us is considering the justice and rights of animals […] trying to attain justice for the voiceless animals within our food system […]. So we want to see a complete end to any form of exploitation, of all cruelty to animals” (manager, national vegan charity). In terms of participatory injustice, this interviewee identified nonhuman animals as the paradigmatic ‘voiceless’ marginalised group entangled in food system politics.

While vegan advocacy has conventionally radiated from the core ethical arguments of animal sentiency, those involved with vegan and vegetarian organisations discussed several factors that have been instrumental in diffusing veganism beyond animal rights concerns, most notably, environmental sustainability and health considerations, which have facilitated greater interest in more plant-based consumption. In particular, vegan activists discussed the importance of connecting the injustice and oppression experienced by agricultural animals to farmworkers and ecosystems, and articulated “the benefits of moving away from animal farming and towards plant protein agriculture [and] coming up with solutions to ensure that farmers can have a sustainable lifestyle […] there’s a perception that we are anti-farming… which we’re not” (campaigner, vegan NGO). This tension was discussed in relation to ensuring that farmers have support to transition towards plant protein agriculture and safeguard sustainable livelihoods (Rodríguez 2018; Broad 2019). Significantly, given the definitive ethico-political position of veganism (for example, regarding the moral treatment of animals), it was discussed by a manager of a national vegan charity that there were ethically defended barriers to building certain alliances, as campaigns such as “less and better meat and dairy does clash with our values”, resulting in various vegan groups and activists believing they occupy the ‘margins’ of the dominant UK food movement.

The material reality and ethical implications of killing animals exposes the complex terrain of justice claims that contextualise the idea of a ‘humane’ or ‘compassionate’ death. This narrative was most vividly expressed by animal welfare groups (who focus on regulation and protection policies) concerning interspecies relations, as a practitioner for an animal welfare organisation stated: “we are opposed to long distance animal transport and inhumane slaughter […] their welfare must be taken into account, so protecting animals as sentient beings”. In this context, protecting nonhuman animals’ welfare was discussed as ensuring their “capacity to perform natural functions, [and] live a dignified life” (policy manager, animal welfare organisation). This formulates animals as subjects of political justice as reflected by the capabilities approach extended to the more-than-human (Nussbaum 2006). It is important to note that such animal-orientated justice considerations (based on the recognition of the sentience and moral worth of nonhuman animals) were mostly absent from other food movement interviewee narratives that drew upon predominately anthropocentric understandings of justice, highlighting a particular obstacle in fostering justice for humans and nonhumans entangled within the food system (Rodríguez 2018).

The role of the neoliberal political economy in shaping the agricultural industrial complex that promotes the intensification of farming was also highlighted as a crucial factor in exploiting and degrading one of the most foundational actants in food systems – soil. As a director of an environmental network charity describes: “the other justice aspect that hasn’t been considered are things like the impact of this [agricultural intensification] on soils. […] there might only be 60 harvests left in our soils globally, and so constantly over-fertilising and taking the maximum out of that […] we’re losing soil at a huge rate”. While this highlights a heightened awareness of the vitality of nonhuman materiality such as soil and the intergenerational consequences of unsustainable farming practices, it still embodies an anthropocentric concern for future agricultural output. Decentring the human requires nurturing nonhuman vitality (Plumwood 2001; Bennett 2010) beyond the instrumentalist agricultural paradigm, and instead understanding ‘resources’ in a more-than-human relational context (Slocum et al. 2016).

Agroecological practices based on diverse situated knowledges, and permaculture in particular, were described by some as a “radical challenge to the mainstream liberal, capitalist model” of food production (practitioner, permaculture NGO). In this context, several community activists stressed that a growing number of grassroots food initiatives are adopting justice-orientated agroecological frameworks, and therefore, can play a crucial role in creating inclusive, nurturing and healing sociospatial relations that address social and ecological justice together (Holmgren 2011). This is vital given that very few groups and organisations adopt a systemic approach to food-related issues and challenges. As an anti-GMO campaigner discussed, despite people approaching the food system from different entry points “which is why the subject is often fragmented into small, specialist groups”, placing advocacy and activism in a broader landscape of just sustainability (Agyeman et al. 2003) provides a holistic foundation to build solidarity and develop connections in the context of intergenerational justice. As an activist involved with the anti-GMO movement explained:

We don’t just talk about GMO, but put it into the context of just sustainability, because in our view it is a symptom of a system that has failed to take up the challenge of producing food in an agroecological and just way. […] [and we] put food in the context of wildlife, health, hunger and malnutrition, and the use of pesticides and climate change […] in which we all have a stake because it affects our future health.

In this sense, coalitions that draw together multiple campaigns, advocacy work and projects that reflect the diversity of actually existing food activism and situate it within a broader (socioecological) justice framework were discussed by several activists as crucial in forging collective power and developing strategic interventions within the policy and governance landscape. This form of connectivity, however, is currently sparse in practice. Therefore, a fundamental challenge to cultivating food justice in the UK and addressing the structural, more-than-human injustices that shape food and farming systems lies in building collective momentum, strengthening alliances and creating political spaces to convene multiple interests in order to overcome fragmented social movement organising.

The justice multiple in UK food movements

Recent scholarship has called for a wider interpretation of food justice, incorporating distribution, recognition, participation and capability-based dimensions to strengthen avenues for collective solidarity (Sbicca 2018). However, there is a paucity of engagement with the multifaceted and extensive body of critical political theory that examines the complexity, meaning and nuance of justice and how this relates to, and can inform, food justice praxis in particular socio-spatial contexts (Dieterle 2015; Barnhill and Doggett 2018). Thus, we have posited that plural, spatial–temporal (or intra-/inter-generational) and more-than-human conceptions of justice should be more fully integrated into a broader notion of food justice. We propose the idea of the justice multiple to draw attention to the entangled web of co-dependencies in which (food) justice can only be achieved when relations of exploitation and the root causes of systems of oppression are addressed through manifold, interconnected contextual practices of justice, while acknowledging difference, diverse knowledges and uneven power relations (Young 1990; Fraser 2008). Indeed, the social, environmental and economic inequalities of the global food system demands that food justice is approached inclusively and holistically, connecting diverse sociospatial situated activism and advocacy within an integrated framework of socioecological justice.

While the concept of food justice is increasingly drawn upon by a range of actors to connect food to crucial matters of injustice (such as poverty), there is a lack of clarity in terms of what exactly food justice is, and what it should look like, in the UK context (Kneafsey et al. 2017). Our research demonstrates that food movement practitioners predominately understand ‘food justice’ in terms of the universal, abstract and anthropocentric right to food, in which all human beings should have access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food regardless of spatial location. Exploring how justice is deployed by actors in relation to their work in practice highlights that the explicit language of justice is often replaced with notions of access, fairness, empowerment, rights and dignity linked to their programmatic focus. This differential articulation of justice frequently reflects the established organisational discursive framings and fragmented nature of advocacy and activism, which tends to focus on particular food system issues.

Rights-based approaches have gained particular momentum among grassroots activists and organisations in the UK, building on academic scholarship advocating for rights-based frameworks to address food poverty (Dowler and Lambie-Mumford 2015). This is exemplified by advocacy currently underway in Scotland, whereby community groups, charities and individuals are campaigning for a legal framework for the progressive realisation of the right to food through the Good Food Nation agenda. The notion of dignity – understood as respect and a sense of meaningful agency – was frequently reiterated by participants in relation to food systems to denote the necessity of everyone having dignified access to adequate, nutritious and culturally appropriate food, whereby the right to food is a matter of justice, rather than charity. More broadly, this draws attention towards the role of the state and issues of governance, regulation and accountability in relation to rights-based frameworks for addressing structural inequalities. Therefore, we suggest future research must untangle the complex (oppositional and supportive) relationships emerging between food (justice) activism and the state (across the devolved nations), paying close attention to possible processes of co-option and de-politicising mechanisms.

The transformative capacity of the right to food agenda will rest not only on its ability to empower citizens and protect and respect the interdependency of different human rights, but also the co-dependencies of socioecological entanglements that form ‘the environment’ (Schlosberg 2007; Millner 2017), nurturing an inclusive rights-based enterprise from below (Armaline et al. 2015) based on the pluralistic recognition of diverse values and rights of humans and nonhumans to live a dignified life. Our research revealed, however, that while it is imperative to expand conceptions of food justice to nonhuman nature (Rodríguez 2018), in practice, placing nonhumans as subjects of justice frequently remains confined to activists or practitioners who explicitly frame their advocacy in relation to animal rights or ecological justice. Therefore, a key challenge remains in enacting plurivocal food justice praxis which recognises and protects the diverse rights of peoples and nonhuman natures, and systematically connects concerns for sustainable diets, animal welfare, environmental health, labour justice and the decarbonisation of the economy – in other words, pursuing sustainability and justice together – in the context of a climate crisis (Agyeman et al. 2003; Ciplet and Harrison 2020).

It is against this backdrop that a small but significant number of organisations have recently adopted a holistic food justice approach to pluralise and diversify the food politics of the possible (cf. Gibson-Graham 2006) based on the reflexive recognition that the established alternative ‘local’ food movement in the UK has largely failed to critically and collectively address the structural processes that reproduce socio-environmental inequality within and beyond the food system. Indeed, addressing the multiple injustices that are inherent within the globalised, industrial, chemically-intensive food system, requires moving beyond the politics of food consumption (Agyeman and McEntee 2014) to place focus on remaking political institutions and implementing progressive policy from the ground up (Alkon and Guthman 2017). In this sense, many food activists in the UK are increasingly and strategically building connections with those ‘outside’ the local food movement, particularly long-standing (broadly defined) ‘left’ organising groups (such as those drawing upon socialist, green, feminist and anti-racist thought), reorienting focus away from food itself and towards issues of (in)justice, rights and sustainable livelihoods.

Our research highlighted that there are multiple, situated endeavours and advocacy processes in the UK whereby the frame of food justice is a productive prism to contextualise various social movements’ activism related to food, particularly those who emphasise addressing class, ethnicity and/or migrant status-based inequalities. Nevertheless, notably absent from the majority of our interviewee narratives was a reflexive consideration of the complex intersectionality of injustices that permeate food systems, particularly in relation to (dis)ability, sexuality and race (the latter of which is central to US food justice activism; see Alkon and Agyeman 2011; Agyeman and McEntee 2014). While migrant labour was critically discussed by some interviewees who reflected upon the compounded injustices based on economic insecurity, gender and race/ethnicity, this was not widely discussed by members of the ‘mainstream’ local food movement. Thus, there are multiple historically-embedded invisibilities of food injustice (particularly related to workers’ rights and land ownership) in terms of how the dominant local food movement frames its priorities. This points to the erasure of the ongoing historical processes of marginalisation and disenfranchisement that reinforce distributional, recognitional, participative and representational injustices across the food system (Alkon and Agyeman 2011). In particular, the intersection of Brexit and the ‘crisis’ of migrant labour in the agrifood system (emphasised by some of our participants), opens up vital questions about the missing voices in deliberations of current and future UK food governance and policy, and the systems of oppression (colonialism, racism, capitalism and patriarchy) that shape post-Brexit food injustice. This requires urgent critical consideration by scholar-activists.

If food justice is to act as a powerful coalescing movement-building framework in the UK, we suggest that cultivating the radical and progressive edges – or the permeable boundaries – of diverse activism (that draw upon critical justice approaches) holds potential for nurturing relationships and developing capacity for meaningful, productive and contentious encounters across manifold creative tension points (Holt-Giménez and Shattuck 2011). Indeed, we argue seeing “the edge as an opportunity rather than a problem is more likely to be successful and adaptable” (Holmgren 2011, p. 223). In practice, this helps direct attention towards the possibilities of coalition networks to be productive translocal assemblages that can generate connectivity between disparate established groups (such as food cooperatives, trade unions and animal welfare groups) at multiple spatial scales to facilitate shared learning and initiate or strengthen imaginative, collaborative strategies that embody a collective ontology of justice to work towards transformative socioecological change.

Imbedding a plurivocal approach into food justice praxis by adopting a justice multiple lens highlights the unresolved tensions regarding the elasticity of the concept in terms of the trade-offs between its depth and breadth. On a practical level, we are not arguing for food movement groups to incorporate all elements of the justice multiple approach within their everyday programmatic focus as this would be highly demanding and idealistic given the tension-laden ethical issues and manifold contestations that exist in relation to food systems. Rather, the aim of this paper has been to propose a pluralised understanding of justice to strengthen ‘food justice’ and argue for a more inclusive, diversified and democratic food politics emanating from the UK that strives for collective solutions to structural food injustices based on shared political responsibility (Young 2011). Central to this approach is recognising the always more-than-human co-dependencies that shape food systems across space and over time. As stated above, cultivating the edges of diverse activism and advocacy to identify and nurture pluralised justice considerations holds particular promise in moving beyond pervasive dichotomies (local/global, rural/urban, human/nonhuman) in fostering avenues for broader coalition-building throughout the food system and beyond, based on collective solidarity to nurture food justice for all.

Notes

The phrase ‘food movement’ is utilised to designate the multiplicity of activists, practitioners, alternative food initiatives and coalition networks working to address diverse food system issues such as environmental sustainability and food (in)security.

A People’s Food Policy is an interesting example of an integrated and people-centred approach to grassroots participatory food policy-making within the UK context (see https://www.peoplesfoodpolicy.org/).

The Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act (2015) is notable for enshrining in legislation the obligation of public bodies in Wales to place sustainable development and the consideration of the long-term impacts of decision-making on current and future generations, at its core.

We use the term ‘practitioner’ to denote a paid employee of a NGO or alternative food initiative and ‘activist’ when utilised by the individual as a self-ascribed identifier.

As participants continue to play an active role in UK food movement politics they are anonymised to ensure confidentiality.

A Menu for Change was a partnership project (2017–19) established as a response to the proliferation of emergency food aid and increasing levels of hunger in Scotland (delivered by Oxfam Scotland, The Poverty Alliance, Nourish Scotland and Child Poverty Action Group in Scotland).

This relates to the campaigning agenda of NGOs within Scotland for a Good Food Nation Bill based on a coordinated approach to food policy.

For example, the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights outlines the right to food in Article 11 and was ratified by the UK Government in 1976.

A coalition of trade unions and civil society organisations enacting collective action in relation to low pay, precarious work, bullying and harassment in the workplace, and also a fight for union recognition across the fast food sector, accumulating in days of strike action in the UK since 2015 (for example, on 4 September 2017 and 4 October 2018).

Significantly, this category does not include farmworkers or fruit-pickers, many of whom are from Eastern Europe.

Abbreviations

- GMO:

-

Genetically Modified Organisms

- NGO:

-

Non-Governmental Organisation

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- US:

-

United States

References

Agyeman, J., R.D. Bullard, and B. Evans. 2003. Just sustainabilities: Development in an unequal world. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Agyeman, J., and J. McEntee. 2014. Moving the field of food justice forward through the lens of urban political ecology. Geography Compass 8 (3): 211–220.

Alkon, A.H. 2014. Food justice and the challenge to neoliberalism. Gastronomica 14 (2): 27–40.

Alkon, A.H., and J. Agyeman (eds.). 2011. Cultivating food justice: Race, class, and sustainability. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Alkon, A.H., and J. Guthman (eds.). 2017. The new food activism: Opposition, cooperation, and collective action. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Alkon, A.H., and T. Mares. 2012. Food sovereignty in US food movements: Radical visions and neoliberal constraints. Agriculture and Human Values 29 (3): 347–359.

Alkon, A.H., and K.M. Norgaard. 2009. Breaking the food chains: An investigation of food justice activism. Sociological Inquiry 79 (3): 289–305.

Allen, P. 2010. Realizing justice in local food systems. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 3 (2): 295–308.

Armaline, W.T., D.S. Glasberg, and B. Purkayastha. 2015. The human rights enterprise. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Barnhill, A., and T. Doggett. 2018. Food ethics I: Food production and food justice. Philosophy Compass 13 (3): 1–13.

Baxter, B. 2005. A theory of ecological justice. New York: Routledge.

Bennett, J. 2010. Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Broad, G.M. 2016. More than just food: Food justice and community change. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.