Abstract

Certification of banana plantations is widely used as a device for protecting and improving socio-economic conditions of wageworkers, including their incomes, working conditions and—increasingly—voice [related to labour relations and workplace representation]. However, to date, evidence about the effectiveness of certification in these domains is scarce. We collected detailed field data on (1) economic benefits for improving household income, (2) social benefits for labour practices, and (3) the voice of wageworkers focusing on identity and identification issues amongst wageworkers at Fairtrade certified banana plantations and comparable, non-certified plantations in the Dominican Republic. We used different types of regression models to identify significant relationships. Econometrical analysis of survey results complemented by field observations and outcomes from in-depth stakeholder interviews indicate that the impact of Fairtrade certification on wageworkers’ economic benefits is rather limited. However, the impact on the voice of wageworkers (job satisfaction, sense of ownership, trust), is more evident. On Fairtrade certified plantations workers are more satisfied with the course of life and better represented. Thus while the additional value of Fairtrade certification on primary wages seems limited, Fairtrade has relevant positive effects on the labour force, particularly by delivering in-kind benefits, offering a sense of job-security, improving voice and enabling private savings. Benefits of (Fairtrade) certification, but also other interventions with a similar purpose, might therefore not be discerned in terms of economic benefits such as wages or basic labour conditions that are under direct control of (inter)national law, but they should be identified in terms of social benefits and improved norms of conduct for wageworker engagement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Wageworkers on plantations and in factories in agriculture, forestry and fisheries represent around one in three out of all workers (FAO 2018a) and are among the most socially vulnerable people in the global commodity trade (ILO 2017a). They often face problems related to poor labour rights, lack of association, salaries that are below a living wage, and operating under abominable health, safety and environmental conditions. What’s more, they are rarely represented by labour unions and thus have a serious lack of social security and protection (Hurst et al. 2005; Mueller and Chan 2015).

To enhance farmers’ and workers’ welfare, there are several ongoing efforts to certify tropical commodities. One of the best-known certification initiatives is Fairtrade. Fairtrade certification of plantations that produce tropical commodities aims to provide workers with more secure and sustainable livelihoods and support their empowerment. This is promulgated through various interventions at the plantation level, such as setting labour standards for hired labour. These labour standards are designed to ensure that wageworkers operate under safe labour conditions, are treated fairly and receive a decent share of the economic returns, including a framework for joint decision-making on premium payments for community investments. In addition, policies focusing on the awareness of grievances and sexual harassment may have an impact on gender relations.

While there are several studies that report on the impact of certification for smallholder producers (e.g. Sirdey and Lemeilleur 2015; Ruben and Fort 2012; Weber 2011; Valkila and Nygren 2010), there is hardly any rigorous empirical evidence available on the effects of certification for wageworkers on plantations. Some recent conceptual papers discuss the potential effects of certification as a tool for improving wageworkers’ welfare (Riisgaard 2015; Raynolds 2014; Makita 2012). Current attention focuses mostly on calculating the necessary living wages to guarantee workers enough income to cover basic expenditures for a dignified and healthy life (Anker and Anker 2017). Far less attention is being devoted to some of the less tangible elements of livelihoods that might strongly influence workers’ well-being, such as perceived workplace safety, identity and transparency.

There are only a few empirical studies that address the net welfare effects of certification at the plantation level (e.g. Ostertag et al. 2014; Krumbiegel et al. 2018) covering the cocoa, coffee, flower and tea export sectors in Ecuador, Ghana, Ethiopia, Uganda and India respectively. However, these studies do not generate many conclusive outcomes on the role of certification in tropical supply chains due to the high diversity of outcomes and strong local spillovers to non-certified farms. It is also increasingly recognised that different impact pathways need to be distinguished to disentangle the effects on wageworkers’ livelihoods (Ruben 2017). In addition, there is clearly a need to collect sound empirical evidence given the large number of wageworkers employed in the agricultural sector in developing countries.

In this study we investigate the contribution between Fairtrade (FT) certification and well-being of wageworkers on banana plantations in the Dominican Republic. The banana is one of the most traded tropical commodities in the world. Most bananas produced at plantations in developing countries are sold to large global buyers and consumed in the United States, Europe, and Japan. The major exporting countries of certified bananas are Ecuador, Peru and the Dominican Republic. Bananas represent a significant product category within the Fairtrade system—both in terms of market demand and producer coverage. However, of all the bananas produced worldwide, only an estimated 5–8% is Fairtrade-certified or covered under another sustainability standard (ITC 2017). In the Dominican Republic, banana production directly provides jobs to an estimated 32,000 workers and generates US$ 430 million in export revenues (ILO 2017a).

We focus on three key impact pathways from FT certification related to wageworker well-being: (a) economic benefits for improving household income, (b) social benefits for labour practices and (c) voice-related benefits focusing on identity and identification issues. Whereas the first two issues are often prevalent in impact evaluation research of certification, the latter is not commonly addressed, while we consider it to be particularly important from a plantation level perspective.

To explore the impact of FT certification, we conducted a field survey among 161 wageworkers that are engaged with five FT-certified banana plantations and 222 wageworkers working at six comparable non-certified plantations. We complemented the survey data with in-depth stakeholder interviews. For the design of the surveys, we relied on the FT theory of change, translating the key topics of certification into specific questions for the structured worker survey, and building as much as possible on existing indicators, definitions and instruments.

Our results show that the direct impact of FT certification on wageworkers’ salaries and fringe benefits is limited, but that FT is positively related to in-kind benefits, a sense of job security, household savings and the number of leave days. The impact on voice indicators (job satisfaction, sense of ownership and trust) is even more evident: on FT-certified plantations workers are generally more satisfied with the course of life and feel better represented.

Role of standards for wageworkers on FT plantations

Most existing literature on the impact of FT certification in tropical commodity value chains focuses on individual smallholder producers (Oya et al. 2017; Sirdey and Lemeilleur 2015; Fort and Ruben 2008). However, since the late 1990 s FT also certifies plantations, aiming to improve working and living conditions for wageworkers. In addition to the general FT principles that focus on social, economic and environmental outcomes, the FT standard for wage labour includes provisions for distributing the FT premium, facilitating freedom of association, ensuring safe labour practices, and providing arrangements for collective bargaining on safe, decent and equitable working conditions (FLO 2017).

The expansion of FT into the fresh produce plantation sector was initially a highly contested issue. Many perceived it as an effort to broaden the FT market share and speed up the mainstreaming of FT standards in a market that is dominated by large multinational companies. At the same time, FT activists remained concerned that FT might lose its “transformative potential” (Raynolds 2007) by supporting the market inequalities it was designed to combat. Organisations of smallholder producers and cooperatives were initially also reluctant to accept certification for wageworkers. Nevertheless, the importance of hired-labour organisations with FT certification relative to smallholder organisations increased considerably. In 2013 a total of 213 hired labour enterprises were registered with a total of 168,600 workers, compared to 754 cooperatives with a total of 1026,000 smallholder farmers (Riisgaard 2015).

The FT labelling organisations made a considerable effort to outline an appropriate theory of change for the certification of hired labour plantations. In 2012, an FT workers’ rights strategy was announced, followed by a revised hired labour standard in 2014. Major attention is given to minimum wages and equal salaries, elimination of child labour, guarantees for gender empowerment, safe working conditions, freedom of union organisation and collective bargaining, and procedures for the distribution of the FT premium for the benefit of workers and their communities. This theory of change is based on a framework for organised and joint bargaining on labour standards and working practices that should generate tangible and intangible economic, social and environmental benefits for wageworkers (Nelson and Martin 2014). Frequent interaction between workers and the plantation management as well as greater stability of labour contracts may also be beneficial for increasing labour productivity at plantations and enhancing the quality of the production processes that could lead to better prices. The latter benefit motivates plantation owners to engage in certification.

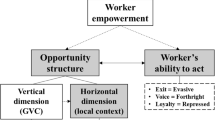

Most impact studies of FT certification focus on the effects on independent farmers’ income and livelihoods (see Oya et al. 2018 for a concise summary). The appraisal of the effectiveness of FT labour standards for wageworkers and their communities needs to devote more attention to mediating variables at the plantation level (i.e. labour conditions and wage bargaining) that may result in decent work and improved welfare. Moreover, the theory of change of certification for FT plantations considers both economic outcomes (wages and secondary benefits) as well as social effects (i.e. safe work, decent housing and fair treatment) that influence household well-being and life satisfaction in a broader sense. For the evaluation of such labour standards, Brown et al. (1996) distinguish three different—albeit mutually reinforcing—impact pathways: (a) economic benefits, (b) social benefits and (c) voice-related benefits from participation in decision-making. Economic effects mainly include improved wages and in-kind benefits that safeguard minimum food security standards. Social indicators especially concern safe working conditions and acceptable workplace relationships. Voice-related indicators relate to opportunities for worker representation, job satisfaction and life course control resulting from identification with plantation affairs. For each of these three categories, we discuss relevant indicators for capturing the potential benefits of certification and outline the evidence base that can be derived from earlier studies (see Fig. 1).

The evidence of FT’s contribution to economic benefits for wageworkers, in particular on wages, food security and living standards, is rather contradictory. Based on research on pineapple plantations in Ghana, Krumbiegel et al. (2018) conclude that wageworkers on FT plantations earn significantly higher wages than wageworkers on non-certified plantations. Ruben and Van Schendel (2008) find that workers on an FT banana plantation in Ghana earn higher hourly wages but receive lower total income than their counterparts on a nearby non-FT plantation. In contrast, Sáenz-Segura and Zúñiga-Arias (2008) find no significant income difference between the workers employed by an FT banana plantation in Costa Rica with those working on a non-FT plantation, even though there are some significant differences in both tangible and non-tangible assets, which are difficult to attribute directly to FT, however. In a similar vein, Cramer et al. (2014) conclude from a large-scale study using panel data from more than 500 carefully selected wageworkers in the tea and coffee sector in Ethiopia and Uganda that there is no conclusive evidence for higher wages among wageworkers of FT-certified producers. A major limitation of most of these studies is that they do not necessarily take into account that wageworkers on plantations may be receiving additional revenue from their homesteads and/or from engaging in off-farm employment or seasonal migration.

Evidence on the impact of FT certification in terms of social conditions is slightly less ambiguous, albeit not very conclusive across countries. Nelson et al. (2013) find a significant positive difference in labour conditions on FT tea plantations in Kenya (but not in India), but it proved hard to attribute this to FT certification as many of the non-certified comparison plantations became certified during the research period. Klier and Possinger (2012) record positive changes in community service provision, some reduction of child labour (due to awareness training) but still limited change in gender roles. Other studies by Cramer et al. (2014) and Valkila and Nygren (2010) conducted respectively among workers in Uganda and Ethiopia and in Nicaragua did not find evidence that FTs helped to improve working conditions for wageworkers.

Evidence on the extent to which FT plantations have contributed in the voice and participation domain is mixed and contradictory. Krumbiegel et al. (2018) find that workers on FT-certified pineapple plantations in Ghana are more satisfied with their jobs than workers on non-certified plantations. Likely drivers of increased job satisfaction are higher wages, permanent employment contracts, training opportunities, company services such as medical care and paid leave, as well as established labour unions on FT-certified plantations. Besky (2013) provides detailed ethnographic evidence of the undervaluation of the workforce and the “tied” labour arrangements at Indian tea plantations that hardly changed with certification. In a similar vein, Makita (2012, 2015) demonstrates that traditional patron-client relations on Asian tea and sugar cane plantations largely remain in place and are sometimes even reinforced, whereas the more independent management structure of the FT premium did help to empower some workers. In a survey of FT-certified organisations in Malawi, Pound (2013) concludes that due to limited education and little management experience most workers’ organisations cannot assume an autonomous role. On the other hand, Lyall (2014) held in-depth focus group discussions with wageworkers from flower plantations in Ecuador and concluded that FT helped to strengthen individual voices and the collective influence and individual choices of these workers, especially through their engagement with the allocation of the FT premium. However, in their qualitative studies on tea plantations in India, Besky (2008, 2013) and Makita (2012) demonstrate that the FT premium received was not invested based on a joint decision-making process by wageworkers but instead fortified the existing patron-client relationships between management and workers.

The wider effects of FT certification at the community and regional levels have been scarcely addressed in the literature. Brown (2013) provides unique insight into how certification of banana plantations in Urabá Valley (Colombia) even created new disparities in material resources and negotiation structures that tend to undermine labour solidarity and reaffirm elite control. In the Dominican Republic, Shreck (2002, 2006) found that minimum pricing and exclusivity of FT certification reinforced socio-economic disparity within farming communities, and reduced non-certified farmers’ access to the labour market. Therefore, standards of certification programmes may (unintentionally) strengthen corporate interests and not workers’ rights and well-being.

For a balanced appreciation of the different types of benefits that wageworkers might receive from FT certification, it is important to consider multiple indicators that together provide insight into the outcome of different impact pathways. In addition, due attention should be given to the appropriate sample size and composition in order to enable a balanced assessment of effects that can be attributed to FT certification. Many of the studies discussed above suffer from serious methodological flaws such as being too small and not having representative samples, and the lack of a credible counterfactual of non-certified plantations and households. In addition, they mostly focus on one of the three domains, and therefore do not provide a complete picture of the potential trade-offs between different impact pathways of FT certification for wageworkers, their families and communities.

Research context, data and methods

Research context: the banana sector in the Dominican Republic

Banana production plays an important role in the national economy of the Dominican Republic, because of its contribution to both the gross domestic product and the Dominican diet—either as a fruit (mature) or as part of a meal (green). The Dominican banana sector is characterised by its strong and dynamic positioning in FT and organic certification. The Dominican Republic is one of the world’s leading exporters of organic and FT bananas, together with Ecuador and Peru (FAO 2018b). An estimated 27,000 hectares are dedicated to the cultivation of bananas, 16,000 of which are exported mainly to Europe and the United States (Espinal 2015).

It is estimated that the sector employs 32,000 workers (ILO 2015). Of these workers, 53% are permanent workers and 47% temporary. Many of the producers do not have permanent workers (almost 30%). The main planting areas are in Montecristi (38%), Valverde (31%) and Azua (27%) (Espinal 2015). The banana production sector in the Dominican Republic contains an estimated 1815 farms, of which almost 60% are small producers with less than four hectares, representing only 12% of the total banana production area. The farms with more than four hectares, as well as those belonging to a plantation, represent around 7% of the total number of farms, and represent 46% of the total banana production area (BAM 2016).

While the banana sector provides a relatively stable flow of income to a large number of workers throughout the year (ILO 2015), the sector faces several challenges with respect to labour rights including the large portion of undocumented migrant workers, constraints on freedom of association, and salaries that are below a living wage.

An estimated 60–75% of wageworkers are migrant workers from Haiti, almost all undocumented (ILO 2015). The percentage of undocumented migrant workers is even higher in Montecristi and Valverde, given the large plantations in the region and the proximity to the Haitian border. This is one of the key challenges the sector faces in terms of workers’ rights. One of the consequences of this informality is that migrant workers (on plantations as well as on small-scale farms) do not have access to social security. While the government, as well as national and international organisations, have been undertaking new efforts recently to document migrant workers, these issues are far from resolved (ILO 2017b; BAM 2015).

A second challenge relates to the lack of worker representation. While the banana production sector is organised at the level of producers, this is not the case at the level of workers (ILO 2017b). In general, few companies have collective bargaining pacts in the Dominican Republic, nor are there any significant unions in the banana sector. Due to several formal and informal restrictions (Smith 2010), few plantations and/or workers are members. On some plantations wageworkers are represented in various wageworker committees, including FT premium committees, but these only have limited influence or bargaining power (ILO 2015).

Another key challenge is that wages are not high enough for workers to enjoy a decent living. Wages and secondary benefits in the banana sector are higher than in other agricultural sectors and above the minimum wage (ILO 2017b). However, ideally a fair wage should be judged according to the living wage definition.Footnote 1 That wages do not yet provide a decent living standard, especially for migrant workers, is evident from the low living standards. For example, based on data from 370 workers, ILO (2015) showed that only 11% of Haitians had access to water (vs. 50% of producers). Also, only 7% of temporary workers had access to healthcare (ILO 2015).

Data and sampling

For our research focus, the relationship between FT certification and labour conditions for wageworkers, we collected data on plantations in Montecristi and Valverde. Most of the plantations, and thus workers, are located in these two regions. There are approximately 22 plantations operating in the northeast region, close to the border with Haiti. To analyse the relationship between FT certification and labour conditions for wageworkers we used data that we collected in the banana sector in 2015 with funding from FT International and one of its member organisations—the FT Foundation in the UK.Footnote 2 Data were collected between February and May 2015. Fieldwork started with interviews with plantation management and other stakeholders; also to develop the appropriate sampling frame. In March and April, a team of local enumerators, trained by one of the authors of this paper, collected data among wageworkers. In May in-depth interviews were conducted with 12 wageworkers (six on FT plantations) and results were discussed in a validation workshop with plantations’ management and wageworker representatives of FT and non-FT plantations.Footnote 3

The data collection occurred at the request of FT to monitor progress in the implementation of FT’s revised hired labour standards in some key banana-producing countries. FT aimed to assess and analyse the difference that FT certification has made across economic, social and voice-related indicators thus far. Next, we discuss how we constructed a realistic counterfactual: what would have happened to the hired labour conditions if the plantation had not received FT certification? This study compares the situation of wageworkers from FT-certified plantations to the situation of wageworkers from otherwise similar but non-FT-certified banana plantations.

At the time of data collection, 14 of these plantations were FT certified, one was in the application process, and seven plantations were not certified.Footnote 4 This region is suitable for organic banana production, and plantations can be characterised by whether they produce organically or not. Organic plantations usually have a different production system and cost structure than conventional ones (i.e. more labour, and fewer chemical fertilisers and pesticides), and they also provide different markets and are confronted with different price fluctuations. All these differences can affect the productivity and profitability of the plantation and hence workers’ wages and conditions. Also, similar types of workers may have different loads and specific tasks in organic and conventional systems, so it is better to compare workers within the same production system. Another important difference among the plantations in this region of the Dominican Republic is their size in terms of workforce. Over half of the plantations in the region have fewer than 100 workers, five have between 100 and 200 workers, and 5 have more than 200 workers (based on primary data and data provided by FT, see Fig. 2).

To obtain a representative sample of plantations we selected FT-certified plantations and for the counterfactual analysis comparable non-certified plantations. First, we deliberately selected a representative sample of five FT-certified wageworker plantations out of the total of 14 FT-certified plantations. The selection was based on three key defining features of the banana hired labour sector in the Dominican Republic as described above: whether a plantation is FT certified,Footnote 5 whether the plantation produces organically, and the size of the plantation in terms of the number of wageworkers employed. All plantations became FT certified between 2007 and 2009. Second, we deliberately selected six comparable albeit non-certified plantations in the same areas, based on the same characteristics: organic versus non-organic production and plantation size in terms of the number of workers. The sample of plantations is well-balanced with respect to organic status, but non-certified plantations are generally somewhat larger in terms of number of workers than the certified ones. Market relations of plantations with their buyers do not differ strongly in terms of the stability of markets.

To obtain a representative sample of wageworkers from the selected plantations we randomly selected 369 wageworkers from the selected plantations; 161 from FT-certified plantations and 208 from non-certified plantations.Footnote 6 Wageworkers were selected randomly from wageworker lists provided by plantation managers, which resulted in a representative sample. For plantations with more than 200 workers we selected around 10% of their workers; for plantations with 100 to 200 workers 25%; and for plantations with less than 100 wageworkers we selected close to 50% of workers.

Table 1 compares wageworkers from FT-certified plantations to those from non-FT-certified plantations. Wageworkers are comparable in several aspects. Twelve percent of the respondents are female. Due to the proximity of the study areas to Haiti and the large immigration of Haitians into the Dominican Republic, more than 60% of wageworkers in both types of banana plantations are Haitians. Migrants’ original households (the ones they left behind) consist of 1.7 members on average. Only 4% of the respondents in both groups own the land they work on.

Wageworkers at FT plantations are significantly different from wageworkers at non-FT plantations in terms of various other characteristics. Compared to wageworkers at non-certified plantations, wageworkers at FT plantations have been employed longer at the plantation they work on, as well as in the banana sector in general, and have been living in the area for a longer time. They are slightly older, their (current) households are smaller, they are more often married, and their households tend to rely more often on other income sources than agricultural wage labour. The first two differences are especially interesting. In qualitative interviews during our first visit respondents told us that wageworkers in non-FT plantations are always looking out for job opportunities at FT plantations; they prefer to work at FT plantations because of more and/or better benefits. Plantation managers told us that workers, including Haitians workers, tend to stay longer on FT plantations than in non-FT plantations—probably for the same reasons. This may be related to the fact that FT policies make it mandatory for managers to help wageworkers from Haiti to obtain all the required papers to formalise their working status in the Dominican Republic.

Aside from these differences there may be other unobserved differences between certified and non-certified plantations, or the type of wageworkers they attract, that could bias our analysis if these same factors also influence wageworkers’ well-being or voice. A first potential bias would be that the FT plantations are more efficient, which could be an additional factor influencing worker well-being, aside from certification (e.g. through improved profits). We consider this bias to be unlikely. All plantations included in our sample were already exporting to European markets—including those that are not FT certified. Also, a recent study by the ILO (2017b) shows that productivity is not necessarily related to being certified or not. Some of the more efficient plantations, in terms of production and profitability, offer economic and social benefits that are in fact equal or higher than the ones available at some FT plantations. A second potential bias is that wageworkers who work on FT plantations are on average more motivated—given the prospect of better working conditions promoted under FT certification—or related to this, more ambitious or hard working. We control for these differences as much as possible by considering the variables listed in Table 1, including years of employment on the plantation.

Indicators

As argued before the study focuses on three key areas of benefits: economic, social and voice-related. The sub-themes covered under the economic benefits include wages, sense of job security, non-wage (in-kind) benefits and proxies for standard of living. These benefits relate to access to sanitation, healthcare and food at the workplace; transport to the plantation; housing and/or access to water and electricity; but also schooling for children, recreation and sports, and access to education for adults. Another key theme for FT that could be subsumed under economic benefits is living wage.1 The living standard sub-theme is strongly related to the living wage discussion, and includes savings (provision for unexpected events), poverty levels and food access (two measures of a decent standard of living).

The sub-themes covered under social benefits include: (awareness of) working conditions on the plantations (working hours, holidays, social security, and occupational health and safety), quality of social dialogue (grievance redressal, relationship to supervisors and trust in relationship) and the FT premium. The FT premium is an additional sum of money which goes to communal funds for workers, to be used to their economic, social or environmental benefit. Examples of such projects reported during field work are helping a community member rebuild a house after it burned down, providing travelling dentist clinics and providing scholarships to children. Many of the indicators related to working conditions are based on ILO concepts and definitions. In the survey we also asked wageworkers about their access to social security as an indicator of social benefits. However, access to social security turned out to be a sensitive issue in the Dominican Republic. Instead of asking wageworkers whether they received a certain security, we asked for details on the type of security received. However, these data turned out to be unreliable, probably because interviewees were often not aware of the details of the type of security they have access to.

The sub-themes captured under voice aimed to create a balance between the general literature and the definition of some empowerment practices (also see Lyall 2014). The sub-themes listed under voice are sense of ownership, membership in workers’ organisations, sense of control and life satisfaction, and changes in individual career prospects through participation in training. FT considers sense of ownership among workers as an important factor in ensuring future sustainability; it is expected to increase as an outcome of the joint decision-making process that Fairtrade aims to implement (for example, in the use of the FT premium). Ownership is based on a conceptual model used by Ruben and Van Schendel (2008) in a study of the banana sector in Ghana and in a study by Van Dyne and Pierce (2004) on psychological ownership and employee attitudes. Membership in worker committees is an important element of empowerment because the use and management of the Fairtrade premium is part of the work of these committees. Finally, life satisfaction captures workers’ satisfaction in relation to income, housing, schooling, vocational training, heath, food, loans and public services.

Empirical model

We empirically test for the contribution of FT certification to the selected indicators based on the worker survey. We estimate the outcome indicators (I) as defined in Table 2 as a function of working on an FT-certified plantation (FT), wageworker characteristics (X), household control variables (Y) and plantation control variables (Z)::

The nth indicator is measured for worker i at plantation j in 2015 (see Table 1). To control for potential bias of worker, household or plantation level characteristics (aside from those controlled for in the sampling designs), we incorporate the set of worker covariates (X), household covariates (Y) and plantation covariates (Y) as listed in Table 1. Household and worker covariates relate to wageworker demographics, education, assets, work experience and residency history (see Table 1). We estimate the model using ordinary least squares (OLS). Since treatment is at the plantation level, we cluster the error term (εij) at the plantation level j.

Robustness analysis

To build a strong counterfactual—i.e. “What would have happened to the hired labour conditions if the plantation had not received FT certification?”—the results from model 1 were combined with the results of qualitative data from the in-depth interviews to triangulate, validate and explain differences or lack thereof.

Moreover, to make our empirical results as robust as possible we test for the effect of FT certification on working conditions and wageworker well-being using three alternative model specifications. Only a randomised experiment can fully eliminate biases in the covariables, both observable and unobservable ones. However, several practical factors and ethical considerations may prevent this type of experiment from taking place. Hence, methods have been sought to approximate the robustness of randomised experiments. Pairing methods are among the most used and complex techniques (Stuart 2015). As a robustness test of the traditional OLS regression with control variables and clustering (model 1) we use propensity score matching (PSM) (model 2), and the entropy balancing method, with and without clustered standard errors at the plantation level (models 3 and 4). A result is considered fully robust if the four models show the same results in terms of sign and significance.Footnote 7

The use of the propensity score—defined as the probability of receiving a treatment given observable covariates—has been popularised among researchers from different fields. This is the first alternative model we use to test for robustness of our OLS estimation (model 1).Footnote 8

However, PSM can lead to bias when there is no clear treatment allocation rule or a very large set of covariates. While this method balances the mean values of the observable covariables, it does not balance variance of observable covariates or differences across groups. In addition, when there are no symmetric distributions in the covariates—such as binary covariables, continuous categories and/or biased variables in a distribution—bias can be reduced in some variables, but it can be increased in others. Hence, PSM can lead to biased impact estimates (Diamond and Sekhon 2013).

Hainmueller and Xu (2013) introduced the entropy balancing method as an alternative pairing method. This method relies on a maximum entropy reweighting scheme that calibrates unit weights so that the reweighted treatment and control group satisfy a potentially large set of pre-specified balance conditions that incorporate information about known sample moments (mean, covariance and bias). Entropy balancing thereby carefully adjusts inequalities between workers from certified and non-certified plantations.

Results

Economic benefits

Table 3 presents the status of wageworkers from FT-certified plantations versus wageworkers from non-certified plantations regarding four different types of economic benefits: (1) wages, (2) security of employment, (3) non-wage benefits and (4) standard of living.

We do not find any significant differences in wages earned by wageworkers at certified or non-certified plantations, nor in terms of job security. The average hourly wage of wageworkers on FT plantations in the sample is RD$ 38, including extra hours or working on a holiday. Wageworkers reported an average working week to consist of 44 working hours. Assuming wageworkers work 6 days a week, this corresponds to a daily wage of RD$ 279. This is in line with the minimum daily wage according to Dominican Republic law at the time of study (RD$ 250), but well below the living wage, which is between RD$ 460 and RD$ 533 per day according to a living wage study conducted by Anker and Anker (2013). Wageworkers from FT-certified plantations feel slightly but not significantly more secure about their jobs: 97% of wageworkers agreed fully or partially with the statement that the plantation offers them a secure job versus 91% among wageworkers at non-certified plantations (see Appendix Table 9). The validation workshop clarified that workers perceived a job to be secure when they could count on having sufficient work and they were paid regularly (usually every 15 days).

Workers at FT plantations also receive more non-wage benefits: an average of six versus four non-wage benefits at non-certified plantations. This difference is most apparent for adult education, transport, healthcare services and schooling for children (see Appendix Table 10). These benefits quite clearly link to FT policies. According to the wageworkers and management, all plantations provide at least food, healthcare, water and transport. Interestingly, many wageworkers indicate they do not receive these basic non-wage benefits or are not aware that they are being provided: 80% of FT workers indicated they received these four benefits versus only 27% of non-FT wageworkers. Whether this is because of a lack of awareness or whether wageworkers actually do not receive them has not become clear during field research. There is no statistically significant difference in the average level of satisfaction with these benefits.

In terms of standard of living, it seems FT wageworkers are slightly better off in two out of the three proxies used. First, more of them have savings (22% vs. 8%). Most workers in both groups said that they save to anticipate the costs of unexpected illness or health problems. Second, more wageworkers at FT plantations are classified as food secure (34% vs. 19%) according to the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale, while fewer wageworkers are classified as severely insecure in terms of food access (48% vs. 69%, see Appendix Table 11). No difference is registered between FT and non-FT wageworkers regarding the Progress out of Poverty Index (PPI) score. The PPI reflects the probability that a household will fall below a certain poverty line. Most of the sampled wageworkers (70%) have a probability of less than 40% of falling below the national poverty line. The difference between results from the PPI and the HFIAS index could not be explained by workers, management or other stakeholders.

Table 4 shows the correlation of FT certification with economic benefits in terms of wages, security of employment, non-wage benefits and standard of living according to model specification (1). First, results show that FT certification is not directly correlated to wages. Second, the model confirms FT certification is positively correlated with in-kind benefits. FT workers receive more in-kind benefits related to adult education, transport, healthcare and schooling for children (see Appendix Table 10), and these benefits are all traceable to the FT premium. Third, while workers at FT plantations report slightly higher levels of job security than workers at non-certified plantations, the difference is not statistically significant. Fourth, the model confirms the positive correlation of FT certification with savings. Note that the findings on hourly wages, non-wage benefits and savings are also confirmed by all other models specified in 3.5 and therefore can be considered robust.

Social benefits

Table 5 shows the status of wageworkers from FT-certified plantations versus wageworkers from non-certified plantations in two different areas of social benefits: (1) working conditions and (2) quality of dialogue on the plantation.

On FT plantations, the average number of paid holidays per year among sampled wageworkers is significantly higher with 15 days per year, which is more than twice as much as on non-FT certified plantations, where the average is 7 days. On both FT- and non-FT-certified plantations, less than a third of sampled wageworkers are aware of grievance and sexual abuse policies. However, differences between FT-certified and non-FT-certified plantations are quite significant. Thirty-two percent of the surveyed wageworkers on FT plantations are aware of a grievance policy, as opposed to only 19% on non-FT-certified plantations. For sexual abuse policies, these numbers are lower: 30% for FT- and 11% for non-FT-certified plantations. During the verification workshop, wageworkers indicated that on FT plantations, wageworkers are better educated to recognise signs of sexual abuse and more informed on how to communicate these.

We find that on average 16% of the surveyed wageworkers are exposed to chemicals in their work; this does not differ significantly between FT-certified and non-FT-certified plantations. Of those exposed, everyone at FT-certified plantations takes at least one precautionary measure, with an average of three measures; this is only slightly but statistically significantly higher than at non-FT-certified plantations (2.5). The measures that score significantly better at FT-certified plantations are the use of suitable overalls, facilities for changing and washing clothing, use of respirators and training received.

In terms of dialogue on the plantation we observe that FT wageworkers are equally confident in expressing their ideas to supervisors but feel significantly more listened to. More than 90% of FT wageworkers feel free and comfortable expressing ideas and concerns to administrators and supervisors. For wageworkers at non-FT-certified plantations this percentage is slightly over 80% (see Appendix Table 11). The average difference in level of agreement (− 2 stands for do not agree at all, + 2 for completely agree) is not statistically significant. However, FT wageworkers do feel significantly more listened to by their supervisors. This difference results from the fact that a significant portion (20%) of non-FT wageworkers disagree with the statement that “administrators and supervisors listen and respond adequately to ideas and concerns”.

Wageworkers also report relatively high levels of trust. More than 90% at both certified and non-certified plantations indicate that they trust other people inside the community, such as fellow wageworkers and the plantation management (see Appendix Table 11). The level of trust towards members of the plantation’s wageworkers committee is much lower—especially at non-certified plantations. At FT-certified plantations, 81% report that they trust members of wageworker committees, including worker representative groups and FT premium committees, compared to 48% at non-certified plantations.

Table 6 shows the contribution of FT in terms of working conditions and quality of dialogue on the plantation according to model (1). First, FT certification is correlated to days of paid leave. Wageworkers at FT-certified plantations have 7 days more paid leave than wageworkers on non-FT-certified plantations. This result is robust to other model specifications. Second, while the awareness of grievance and sexual harassment policies is significantly higher among workers on FT plantations, results from model (1) do not attribute this to FT. Interestingly, all models without clustered standard errors do indicate a significant and strong correlation. This could be caused by the fact that FT might have influenced both the degree and/or awareness of grievances among wageworkers. The same applies to the views of wageworkers regarding the role that FT certification plays in the relationship with supervisors. Third, our results show FT contributed to increased levels of trust in fellow wageworkers and the union or group that represents them at the plantation level, but not in plantation management. Only the correlation between FT certification and trust in members of the worker representation is robust to all models. Contrary to the findings concerning economic benefits, various findings regarding social benefits are not robust to our alternative model specifications; this means that some of the observed differences (or the lack thereof) are not consistently linked to being FT certified.

Voice-related benefits

Table 7 shows the status of wageworkers from FT-certified plantations versus wageworkers from non-FT-certified plantations in terms of four different areas of voice-related benefits: (1) sense of ownership, (2) membership in workers’ organisation, (3) perceived sense of control over course of life, and current satisfaction with life, and (4) career satisfaction and prospects for progression.

Wageworkers from FT plantations have a stronger sense of ownership than wageworkers from non-FT-certified plantations (80% compared to 51%—see Annex A2). The same pattern can be identified for other ownership-related statements. Overall, wageworkers from FT-certified plantations have a significantly stronger sense of (co)ownership compared to wageworkers from non-FT-certificated plantations. In the in-depth interviews various wageworkers explained that this sense of ownership is a way of expressing their gratitude for the extra benefits given by the FT premium. Furthermore, they feel better able to communicate with the administration via the wageworkers committee.

Significantly more wageworkers from FT plantations are members of a workers’ representative group (20% vs. 2%). These groups are often directly related to the use of the FT premium as collective bargaining and representatives’ groups are not common on plantations in the Dominican Republic. During the verification workshop, wageworkers indicated that on FT plantations it seems more worthwhile to join a workers’ committee because they deem it beneficial, while on non-FT-certified plantations wageworkers perceived fewer direct benefits.

In terms of sense of control and life satisfaction it seems that wageworkers from FT-certified plantations are more satisfied and feel that they have more control over their lives—although these differences are not, or only marginally, statistically significant. However, wageworkers at FT plantations are significantly more positive about current and future areas of development compared to wageworkers from non-FT-certified plantations. Managers indicated that these results stem from a clear advantage of FT plantations because they have the funds to improve the services for their workers. The more optimistic development perceptions at FT plantations appear to be based on various benefits (including housing, income and schooling). More access to loans is a salient difference between FT and non-FT plantations, while there appears to be hardly any difference in terms of better public services.

Finally, wageworkers from FT-certified plantations are doing better in terms of two out of three indicators related to career satisfaction and progression. FT wageworkers indicate they have experienced significantly more improvements in their job (90% vs. 57%, see Appendix Table 11). At both FT and non-FT plantations most of the wageworkers indicate that they fully agree with the statement that they are “able to reach full potential in their work”. The validation workshop did clarify that the positive attitude of wageworkers at banana plantations (FT and non-FT?) may have resulted from the fact that they are relatively better off than in some other sectors. The biggest and most significant difference is observed in relation to in-house training. Far more wageworkers from FT plantations receive training (71% vs. 27% on non-FT plantations), and they also receive it more often. During the interviews with wageworkers from FT plantations, many of them were proud to mention they feel more “competent”. Some started at the plantation as regular wageworkers and got a better position through training and opportunity. Some former FT wageworkers even gained positions as technicians elsewhere. The major difference according to wageworkers between FT- and non-FT-certified plantations is that FT also provides technical training in areas different from the ones they need on the plantation.

Table 8 shows the contribution of FT in terms of sense of ownership, membership in workers’ organisations, sense of control and life satisfaction, and career satisfaction and progression according to model (1). First, FT has contributed significantly to the sense of ownership, which is perhaps not surprising given the large difference in sense of ownership between wageworkers from certified and non-certified plantations. Second, FT certification is correlated to a higher level of satisfaction with current development, but not to a higher level of development prospects for the future. Third, FT has increased the likelihood that a wageworker experienced improvements in job satisfaction and received training. These results are robust to alternative model specifications. The higher membership in workers’ organisations among FT workers is, however, not robust to alternative model specifications, meaning that the role of FT is not strong or consistent.

Discussion and conclusions

Wageworkers on plantations and in factories that produce and process tropical commodities are among the most vulnerable people in the global commodity trade. Labour standards, such as those promoted under FT certification, are designed to ensure that wageworkers can operate under safe labour conditions, are treated fairly and receive a decent living wage. However, there is still little rigorous evidence on the effects of certification for wageworkers on plantations, and most earlier studies tend to focus only on direct income effects whereas other, less tangible benefits might be important as well.

This study evaluated the contribution of FT certification of banana plantations in the Dominican Republic on wageworkers’ (1) economic outcomes, (2) social outcomes, and (3) voice-related outcomes. We collected household survey data from 161 wageworkers engaged with five FT-certified plantations and from 222 wageworkers working at six comparable non-certified banana plantations in the Dominican Republic. Survey data were complemented with data from in-depth stakeholder interviews. We corrected for sample selection bias to distinguish the effects that can be attributed to FT certification and from those that can be attributed to differences between wageworkers or plantations.

Our results show that FT certification is not directly correlated to primary wages; while wages paid are in line with minimum wages they are still far below a decent living wage However, wageworkers at FT-certified plantations report more in-kind benefits and a higher sense of job security. They also maintain higher savings. Both the better sense of job security and the higher savings might be related to the better in-kind benefits, such as adult education for wageworkers at FT plantations, and company services of healthcare and schooling for children.

In terms of working conditions and the quality of dialogue on the plantation we find that FT workers have more paid leave days and have higher trust in worker representation compared to similar wageworkers on non-certified plantations. Both impact areas can be linked to stipulations in the FT standard. We find that approximately 30% of FT workers are aware of grievance and sexual harassment policies. While this is higher than on non-certified plantations, the difference cannot significantly be attributed to FT.

Our results also show that FT certification is most positively correlated to wageworkers’ voice-related benefits. While controlling for confounding variables and after matching, wageworkers at FT-certified plantations demonstrate a significantly higher sense of workplace co-ownership, are more satisfied with their current level of development and are more likely to have received technical or vocational training.

Since data analysis is based on a cross-sectional design, we cannot fully attribute all wageworker differences to FT certification alone. Plantations might have been different in more respects than just in terms of certification status alone, and these initial differences could contribute to the outcomes as well. However, we tried to reduce selection bias as much as possible, both in the sampling design (by deliberately selecting nearby non-certified plantations) and through our statistical analysis (by controlling for potentially confounding variables in different model specifications and by applying matching techniques). Several differences between wageworkers at certified and non-certified plantations that could be observed from descriptive statistics have thus been corrected.

The results reported in this study are robust to various model specifications. Part of the results we registered may be due to unobserved characteristics that are difficult to capture. For example, workers at FT-certified plantations might be more motivated and better informed about working conditions than their peers at non-FT-certified plantations. Their level of motivation and awareness could be the very reason why they are working at FT-certified plantations, and not vice versa. This means that the coefficients we measure might overestimate the true effect of FT certification. Moreover, FT banana certification (and compliance with EurepGAP standards) is becoming more generalised in banana production in the Dominican Republic, and thus differences between plantations tend to become smaller over time.

Keeping this in mind, we cautiously conclude that FT has some relevant positive effects on the labour force, particularly by delivering in-kind benefits, offering a sense of job security and enabling private savings. FT certification also seems to have a positive effect on wageworkers’ voice. The current focus on living wages in the sector tends to overlook these less tangible—albeit equally important—benefits. Even if FT certification does not lead directly to decent or even higher primary wages, and is thereby no substitute for legally enforceable standards of decent wages—as Besky concludes (2018)—it could contribute to better livelihood conditions. Bottom-up empowerment may be a requirement for modifying norms of conduct and to guarantee a true impact on labour conditions in the long term (e.g. see Raynolds 2014). Benefits of (FT) certification, but also other interventions with a similar purpose, may therefore not be reflected by economic benefits such as wages or basic labour conditions that are under the direct control of national and international law. Instead, they should be identified in terms of social benefits (e.g. access to and satisfaction with sanitation and healthcare), and especially in terms of voice-related benefits. Our research clearly shows the need for impact studies of certification to look beyond the directly observable effects and take a deeper dive into long-lasting behavioural implications.

Notes

The concept of “living wage” is defined as “remuneration received for a standard work week by a worker in a particular place sufficient to afford a decent standard of living of the worker and her or his family”. Elements of a decent standard of living include food, water, housing, education, healthcare, transport, clothing and other essential needs including provision for unexpected events. Living wage thus depends on many factors and is clearly a contextualised concept; it was outside the scope of this study to investigate this in its fullest extent (as done by Anker and Anker 2013, for example).

Fairtrade International, nor the Fairtrade Foundation, were directly involved in data collection, data analysis or report writing. FT was asked to provide information, feedback and validation at various stages in the research.

The survey and guidelines for in depth interviews can be accessed on www.wur.nl/upload_mm/d/e/9/8d34a466-9c6e-4853-a627-47be4753a256_2015-056%20Rijn_final.pdf.

Based on information provided by FT and Adobanano (Asociación Dominicana de Bananeros) (January 2015).

There are only 4 plantations in the area with other certifications, almost all of which are related to supermarket requirements. Two of the certified plantations in our sample have the Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI), focused on improving workers’ conditions and one also has a Tesco and Field to Folk certificate, focused on good agricultural practices required by supermarket chains.

To give an indication of the statistical power of the sample we calculated ex-post that we could capture a 9% difference in wages (with mean values and standard deviations based on the data) and an 8% difference in terms of control over life.

In the results table we indicate the number of robustness models that give the same result in terms of significance and direction.

In the PSM procedure, only one wageworker fell outside the area of common support (the area where the two sub-samples overlap in terms of propensity score) which indicates a good overlap for statistical analysis in terms of observable characteristics as provided in Table 1.

References

Anker, R., and M. Anker. 2017. Living Wages around the World. Manual for Measurement. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Anker, R., and M. Anker. 2013. Living Wage for Rural Dominican Republic with Focus on Banana Growing Area of the North. Report prepared for Fairtrade International (Bonn) and Social Accountability International.

Banana Accompanying Measures Programme (BAM). 2016. Informe Descriptivo Intermedio.- Periodo Febrero-2014-Enero-2015; Componente de Asistencia Técnica y Capacitación.- Medidas de Acompañamiento del Banano (BAM). República Dominicana.

Brown, S. 2013. One hundred years of labor control: Violence, militancy, and the fairtrade banana commodity chain in Colombia. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 45 (11): 2572–2591.

Brown, D.K., A.V. Deardorff, and R.M. Stern. 1996. International Labour Standards and Trade: A theoretical analysis. In Fair trade and harmonisation: Prerequisites for free trade?, ed. Jagdish Bhagwati and Robert Hudec, 227–272. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Besky, S. 2008. Can a plantation be fair? Paradoxes and possibilities in fair trade Darjeeling tea certification. Anthropology of Work Review 29 (1): 1–9.

Besky, S. 2013. The Darjeeling distinction: Labor and justice on Fair-Trade tea plantations in India. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Cramer, C., D. Johnston, C. Oya, and J. Sender. 2014. Fairtrade, employment and poverty reduction in Ethiopia and Uganda. London: School of Oriental and Asian Studies (SOAS).

Diamond, A., and J.S. Sekhon. 2013. Genetic matching for estimating causal effects: A general multivariate matching method for achieving balance in observational studies. Review of Economics and Statistics 95 (3): 932–945.

Espinal, J. 2015. Levantamiento de información sobre la situación actual de los productores de banano en relación a la obtención y/o actualización de certificaciones de mercado en las provincias de Azua, Valverde y Montecristi, República Dominicana.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2015. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide.

Fairtrade Labelling Organizations international (FLO). 2017. Aims of Fairtrade Standards https://www.fairtrade.net/standards/aims-of-fairtrade-standards.html. Accessed 20 Nov 2017.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2018a. Regulating labour and safety standards in the agriculture, forestry and fisheries sectors.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2018b. Banana facts and figures http://www.fao.org/economic/est/est-commodities/bananas/bananafacts/en. Accessed 7 Aug 2019.

Fort, R., and R. Ruben. 2008. The impact of Fairtrade on banana producers in Northern Peru. In The impact of Fairtrade, ed. Ruerd Ruben, 49–73. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

Hainmueller, J., and Y. Xu. 2013. Ebalance: A Stata package for entropy balancing. Journal of Statistical Software 54: 7.

Hurst, P., P. Termine, and M. Karl. 2005. Agricultural workers and their contribution to sustainable agriculture and rural development. Rome and Geneva: FAO and ILO.

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2015. Diagnóstico sobre las condiciones laborales y de seguridad social de los productores y trabajadores del sector banano de las provincias Azua, Valverde y Montecristi, República Dominicana, Oficina Internacional de Trabajo (OIT), Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo (PNUD).

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2017a. Trends and developments in the plantation sector, Sectoral Policies Department. Geneva: UN International Labour Organization.

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2017b. “Creating shared value in the Dominican Republic banana industry. A market systems analysis of plantation business performance and worker wages. Sectoral Policies Department”. Geneva: UN International Labour Organization.

International Trade Center (ITC). 2017. The state of sustainable markets 2017. http://www.intracen.org/uploadedFiles/intracenorg/Content/Publications/State-of-Sustainable-Market-2017_web.pdf. Accessed 7 Aug 2019.

Klier, S., and S. Possinger. 2012. Assessing the impact of Fairtrade on poverty reduction through rural development. Saarbrucken, Centre for Evaluation/CeVal. Commissioned by TransFair Germany and Max Havelaar Foundation Switzerland.

Krumbiegel, K., M. Maertens, and M. Wollni. 2018. The role of Fairtrade certification for wages and job satisfaction of wageworkers. World Development 102: 195–212.

Lyall, A. 2014. Assessing the impacts of Fairtrade on worker-defined norms of empowerment on Ecuadorian flower plantations. Geneva: Fairtrade International.

Makita, R. 2012. Fair trade certification: The case of tea wageworkers in India. Development Policy Review 30 (1): 87–107.

Makita, R. 2015. Fair trade and wageworkers in Asia. In Handbook of research on Fair Trade, ed. L. Raynolds and E. Bennett, 491–508. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Mueller, B. and M. Chan. 2015. Wage labor, Agriculture-based Economies and Pathways out of Poverty—Taking Stock of the Evidence. ACDI/VOCA with funding from USAID/E3’s Leveraging Economic Opportunities (LEO) project.

Nelson, V., et al. 2013. Assessing the poverty impact of voluntary trade standards. Greenwich: Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich.

Nelson, V., and A. Martin. 2014. Fairtrade International’s multi-dimensional impacts in Africa. In Handbook of research on Fair Trade, ed. Laura Raynolds and Elizabeth Bennett, 509–531. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Ostertag, C.F., et al. 2014. An evaluation of Fairtrade impact on smallholders and workers in the banana sector in northern Colombia. Bogota: The Corporation for Rural Business Development (CODER).

Oya, C., F. Schaefer, D. Skalidou, C. McCosker, and L. Langer. 2017. Effects of certification schemes for agricultural production on socio-economic outcomes in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews 13 (1): 1–346.

Oya, C., F. Schaefer, and D. Skalidou. 2018. The effectiveness of agricultural certification in developing countries: A systematic review. World Development 112: 282–312.

Pound, B. 2013. Branching out: Fair trade in Malawi. Monitoring the impact of Fairtrade on 5 certified organizations. Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich in collaboration with the Malawi Fairtrade Network, Fairtrade Africa and the Fairtrade Foundation.

Raynolds, L. 2007. Fair Trade bananas: Broadening the movement and market in the United States. In Handbook of research on Fair Trade, ed. Laura Raynolds and Elizabeth Bennett, 63–82. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Raynolds, L. 2014. Fairtrade, certification, and labor: Global and local tensions in improving conditions for agricultural workers. Agriculture and Human Values 31: 499–511.

Riisgaard, L. 2015. Fairtrade certification, conventions and labor. In Handbook of research on Fair Trade, ed. L. Raynolds and E. Bennett, 120–138. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Ruben, R. 2017. Impact assessment of commodity standards: Towards inclusive value chains. Microfinance and Enterprise Development 28 (1–2): 82–97.

Ruben, R., et al. 2008. Fairtrade impact of banana production in El Guabo Association, Ecuador: a production function analysis. The impact of Fairtrade, 155–167. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

Ruben, R., and R. Fort. 2012. The impact of Fair Trade certification for coffee farmers in Peru. World Development 40 (3): 570–582.

Ruben, R., and L. van Schendel. 2008. The impact of Fairtrade in banana plantations in Ghana: Income, ownership and livelihoods of banana workers. In The impact of Fair Trade, ed. R. Ruben. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

Sáenz-Segura, F., and G. Zúñiga-Arias. 2008. Assessment of the effect of Fair Trade on smallholder producers in Costa Rica: A comparative study in the coffee sector. In The impact of Fair Trade, ed. R. Ruben, 117–135. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

Schreiner, M. 2014. How Do the Poverty Scorecard and the PAT Differ? http://www.microfinance.com/#Poverty_Scoring. Accessed Dec 2014.

Sirdey, N. and S. Lemeilleur. 2015. Fair Trade Standards and food security: identifying potential impact pathways.

Shreck, A. 2002. Just bananas? Fair Trade banana production in the Dominican Republic. International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food 10: 11–21.

Shreck, A. 2006. What Organic and Fair Trade Labels do not tell us: Towards a place based understanding of certification. International Journal of Consumer Studies. 30 (5): 498.

Smith, G. 2010. Fairtrade bananas: A global assessment of impact. Sussex: Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex.

Stuart, Elizabeth A. 2015. Matching methods for causal inference: A review and a look forward. Statistical Science: A Review Journal of the Institute of Mathematical Statistics 25 (1): 1.

Van Dyne, L., and J.L. Pierce. 2004. Psychological ownership and feelings of possession: Three field studies predicting employee attitudes and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior 25 (4): 439–459.

Valkila, J., and A. Nygren. 2010. Impacts of Fair Trade certification on coffee farmers, cooperatives, and laborers in Nicaragua. Agriculture and Human Values 27 (3): 321–333.

Weber, J.G. 2011. How much more do growers receive for Fair Trade-organic coffee? Food Policy 36: 678–685.

Acknowledgements

Data collection for this study was supported by a grant from Fairtrade International and one of its member organisations—the Fairtrade Foundation in the UK. The design of field work procedures and data analysis was conducted fully independently. The authors would also like to thank Julian Cruz, Susana Gamez and Jaime Ortega Tous from Cruz CiD Dominican Republic for their contribution to the fieldwork. The importance of trustworthy and reliable local partners is often underestimated. Lastly, the authors would like to acknowledge both the Fairtrade-certified and non-certified plantations, the wageworkers in particular, for participating and contributing to the study. Their cooperation has been most appreciated. The authors remain fully responsible for independent data analysis and interpretation of results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

van Rijn, F., Fort, R., Ruben, R. et al. Does certification improve hired labour conditions and wageworker conditions at banana plantations?. Agric Hum Values 37, 353–370 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-019-09990-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-019-09990-7