Abstract

Farmers markets (FMs) have traditionally served as a space for farmers to sell directly to consumers. Recently, many FMs in the US and other regions have experienced a renaissance. This article compares the different value sets embedded in the rules and norms of two metropolitan FM regions—Minneapolis, Minnesota and in Vienna, Austria. It uses a values-based framework that reflects the relationships among FM operating structures (OS) and their values reflected by the key FM participants—i.e., farmer/vendors, consumers and market managers. The framework allows us to focus on two very contrasting value sets of metropolitan FM regions in (1) presenting and discussing the values found and embedded in the two metropolitan market regions; (2) illustrating how the values found are embodied as rules and norms in each FM region; (3) considering the alignment or not of FM participant values with their corresponding FM values; and (4) the differences and commonalities as well as the benefits and challenges of the two market regions. In contrasting metropolitan FMs we explain that FM value sets are complex and differ among and within FM participant groups and are dependent on their respective OS. We show that contrasting two metropolitan FM regions can be useful in understanding beneficial and disadvantageous relationships between the values and structures of, and in FMs, and specifically in examining institutional impediments such as governance. Thus we illustrate the possibilities and limitations of values for and within metropolitan FMs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

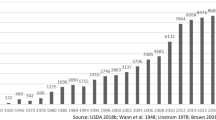

Over the past 20 years, metropolitan farmers markets, once the principal public means of food procurement for large urban populations in Europe and North America, have been experiencing a revival. Prior to this revival and since the 1950s, with globalization, refrigeration, and the opening of supermarkets that offered access to a far more diverse assortment of goods, farmers markets across the US experienced a decrease in sales and patronage. Many farmers markets (FMs) closed or drastically reduced in size. Some, like The Minneapolis Farmers Market, began to allow non-farmer food resellers into the market in order to attract customers. The revival of FMs in the US during the 1980s included the introduction of new perspectives on market values and functions. Markets were seen as opportunities to: support small farmers and to promote direct contact between consumers and producers (Holloway and Kneafsey 2000; Moore 2006); make locally produced and healthy products widely available (Baker et al. 2009; Byker et al. 2012); boost local economies (Brown and Miller 2009) create community (Andreatta and Wickliffe 2002; Colasanti et al. 2010), and to offer consumers an alternative to “industrialized food” marketing and distribution (Feagan and Morris 2009; Byker et al. 2012). These value changes, and others, continue to transform the role of FMs in our evolving food systems.

The principal author lived, participated and studied in two very different metropolitan FM areas—one in Vienna, Austria and the other in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Through her experience she noticed significant differences in the FMs of both regions. In particular, she observed that changes in the Viennese markets appeared to limit the opportunities of both farmers and consumers, unlike what seemed to be occurring in Minneapolis. More specifically, the market values widely exhibited in the Minneapolis markets were significantly less visible in the Viennese FMs. In Austria—a country where regional and organic foods are a high priority (BMLFUW 2016)—many Viennese metropolitan FMs have steadily declined in recent years in both the number of farmer/vendors and the space devoted to them. Moreover, the share of the Viennese FMs in overall food sales has fallen (Schermer 2008; Gutes vom Bauernhof 2016). This contrasts markedly with the dramatic growth in the number and popularity of FMs throughout the US (Farmers Market Coalition 2014; AMS and USDA 2014).

These cases illustrate two different approaches to values and functions of FMs and they reveal larger trends in their areas. In Vienna, the decline of FM space and of farmer/vendors contrasts with FM trends in the US, and with the explosion of CSAs and other alternative food movements in both North America and Europe, specifically outside of Austria (Schermer 2015).

This paper questions if comparing these different metropolitan FM regions within their place-based contexts can help to understand the role that predominantly non-economic values play within them? After discussing the prioritization of different values within both FM regions, this paper highlights the cross-cultural differences between the metropolitan FM regions. We use a cross-national comparative analytical framework that highlights the values-based relationships between the operating structure (OS) (see below) of the markets and the values reflected by the key FM participants—i.e., farmer/vendors, consumers and market managers. The framework draws our attention to the interrelationship between the structure of a FM, or its OS, and the values found in the FMs as expressed in the rules and norms and as practiced by major FM participants. Thus this paper—using Vienna and Minneapolis FM regions—illustrates the potential implication of different models of FMs that are possible. By taking a market-wide perspective that includes all FM participants, our values-based analysis helps to identify how FMs might become more significant social and marketing venues that connect farmers and consumers, specifically in European metropolitan markets.

Following a brief review of current research that addresses FM values, we discuss our values-based operational framework and research methods. After an overview of the markets in Vienna and Minneapolis, we apply the framework and focus our discussion on the ways in which values are embodied in the markets’ Purpose, that is, their mission and goals. The paper concludes with a discussion of the implications for prioritizing some operations and values over others and the use of our framework for further research.

Framing the study

As with any FM, those in the metropolitan areas of both Austria and the US can be seen as sites of ‘embedded’ economic activities.Footnote 1 They can connect a specific place and a set of socio-economic activities that might include ecological concerns (Hinrichs 2000; Sage 2003; Kirwan 2004; Feagan and Morris 2009; Morris and Kirwan 2011).

As socially embedded places, FMs are sites where direct face-to-face communication and trust can create more than simply commercial (buyer–seller) relationships between farmers and consumers (Holloway and Kneafsey 2000). In this way, FMs may contribute to a move away from a dominant industrial food system to one that offers spaces for alternative “green” economic relationships (Morris and Kirwan 2011; Alkon 2012). FMs can also support rural and urban community development (Hinrichs et al. 2004; Alkon 2008; Stephenson 2008; Beckie et al. 2012).

In order to capture this embeddedness, yet respect the individuality of markets we use an analytical framework that views FMs as sets of interrelated operations, values, social interactions and relationships among key participants. These interrelationships are expressed or found in a market’s operating structures, or what we see as their purpose, governance, participants, finance and marketing, and community.Footnote 2 We adapt these concepts in addition to aspects of Stephenson’s Agro-Social-Economic-Regulatory Ecology of FMs (2008) to describe and examine a FMs operating structure. In addition, we specifically seek to assess the ways in which values related to health, ecology, fairness and care are embodied in the FMs. These four values, drawn from the IFOAM Principles,Footnote 3 paired with a FM’s OS offer a useful analytic tool—a values-based operational framework—that generates useful insights for the cross-national comparison of metropolitan markets.

Our analysis builds on two bodies of FM studies: those examining how FMs are structured and operate (Govindasamy et al. 1998; Brown 2001; Andreatta and Wickliffe 2002; Payne 2002; Stephenson 2008), and those looking specifically at the value placed on the source or origin of produce and products on sale (La Trobe 2001; Feagan et al. 2004; Gillespie et al. 2007; Alkon 2008; Brown and Miller 2009). However, we expand our perspective beyond the value of “localness” or “farmer-only” sales per se in order to explore the relationships between the values embodied in FM’s operating structures, as well as those expressed by the FM managers, farmer/vendors and consumers (See: Smithers et al. 2008; Alkon and McCullen 2011; Alkon 2012).

The following two sub-sections outline the key concepts around which we build our values-based operating framework for a cross-national comparison of metropolitan FMs.

Farmers market operating structures

The central, empirically grounded components of a FM’s operating structure—purpose, governance, participants, finance and marketing, and community—are elaborated below through respective FM literature.

Purpose

FMs are socially embedded and reflect changes in consumer preferences and motivation among alternative food movements (Sage 2003; Kirwan 2006; Connell et al. 2008). Many FMs specifically advertise that their purpose may involve health, farmer support, community, food and farming education, and sustainability (Byker et al. 2012). For example, a FM whose purpose is to promote sustainability might recruit organic and local farmers, educate consumers at booths that offer presentations or materials on sustainability, or encourage zero-waste programs.

Governance

The way decisions are made within a FM, how it is structured, and how responsibility is distributed is vital to a FMs overall success (Gantla 2014). For Mount (2012), whether a governance system chooses to value the ability to be reflexive or non-reflexive determines whether a market can be flexible and adaptable to future changes. Some studies have examined the influence of a FM’s OS, including their governance, in relation to consumer participation. They recognized linkages from types of governance structures to types of FM shoppers (Hofmann et al. 2008; Betz and Farmer 2016). That is, the values behind FM governance can influence a FM’s success via its ability to connect to the values of its consumers.

Participants

Numerous FM studies focus on consumer perspectives. These include studies of FM consumer motivations and attitudes (Brown 2002; Rimal et al. 2010; Betz and Farmer 2016) including personal values and value systems to consumption motivation (Byker et al. 2012). Significantly fewer FM studies examine more than one FM participant group. Even rarer are studies that encompass consumers, vendors and market management (see Smithers et al. 2008). Since many sets of actors (managers, farmer/vendors and consumers) influence a FM, these three groups, at least, should be included in examining FM values and OS, thereby offering a more inclusive perspective of a FM system.

Finance and marketing

Although many FM studies focus on the economic impact of FMs (Hughes et al. 2008), or on effective marketing or advertisement techniques (Baker et al. 2009; Berry et al. 2013), few highlight how governance might influence these techniques. Gantla and Lev (2016) examined ownership structures of FMs in Oregon and found that different ownership structures can have significantly different impacts on the conduct and performance of the markets. In our research, we found similar results; the values underlying the different ownership and governance forms of Viennese and Minneapolis FMs often lead to both differences and limitations in the way the markets are financed or in marketing procedures.

Community

Some studies recognize FMs as spaces for “re-socializing food”, taking FMs beyond narrow economic definitions (Kirwan 2006). As socially embedded economic places (Winter 2003), FMs reflect their physical, cultural and political environments (Stephenson 2008). They are rooted in different contexts and reflect different sets of values that encompass everyday social and environmental issues (Alkon 2012). Values associated with, and at FMs, have often been framed as beneficial for the markets’ surrounding community both socially (Gillespie et al. 2007) and economically (Brown and Miller 2009). More broadly, FMs are also studied for their role in supporting alternative food systems (Feagan and Morris 2009).

Values

Connell et al. exploring values-based food choices of FM consumers, identified FMs as a “…medium for expressing values associated with food choices” (2008, p. 182). Values represent the critical link from principles to actions (Zak 2008). In FMs, values and attitudes are revealed through the creation and re-creation of these principles and actions and are part of shaping the alternative food movement as well as the current food system (Morris and Young 2000). The values for assessing the above OS components of FMs and their interrelationships are inspired by a set of food and farming principles that include values concerning: health, ecology, fairness and care. For our framework, we find that these IFOAM Principles are useful as they offer a coherent economic and ethical foundation for identifying the values of importance to the FM participant groups.Footnote 4 We are specifically interested in understanding how the values of health, ecology, fairness and care are embodied in, and expressed through market rules and norms. This understanding helps us then consider the alignment of values within markets. That is, how values are revealed in the FM rules and norms—these created and recreated principles and actions—and how they are shared or reconciled among the major participant groups.

We recognize the reciprocal influence and relationships between the OS and the values embodied in a FM. Some markets may be set up specifically to express certain values, while in others values are implicit in the OS. In other words, the structure may influence the values expressed just as the values might drive the operating structure.

Using this values-based operational framework we ask four central questions: What values are present in each FM region? How are these values manifested—through practices and understandings—in a FM’s rules and norms? Are these values ‘holistically aligned’ or shared among all of the FM participant groups? How do the values found and their alignment (or not) within FM participant groups compare between the two different metropolitan FM regions? In asking these questions, we gain new insight on the differences of the two FM regions examined here and how value prioritization and alignment among FM participants might benefit or limit a market.

Methods

The values-based operational framework was created to guide our entire research. It first helped to frame interview and dot-survey questions relating values to particular operations of FMs and inversely FM operations to values. Secondly the framework helped to identify what was being said within existing literature, interviews, participatory observation and dot-surveys, in which our participatory observation further allowed us to understand the actions behind FM values. These dynamics and values were compared between markets within the individual cities and between the markets of Minneapolis and Vienna. Discussions with central stakeholders and repeated contact with key actors added to our picture of both market regions. The resulting values identified in using this framework and discussed in the sections below (see also Tables 1, 2) were selected due to prevalence (i.e., the frequency in which they were found in the empirical data and their visibility at the market level), and influence (i.e., possible impact on the market or its participants).

Empirical data collection and visits to all farmers markets occurred from 2012 to 2014. Over this period, twelve farmers markets were studied—six from Vienna and six from Minneapolis. A content analysis identifying the key values in each FM’s mission statement found on their websites was undertaken. Semi-structured, open-ended qualitative interviews were conducted with market managers and market vendors of each market. These totaled in 42 interviews ranging from 45 min to 2.5 h. They were coded structurally and analyzed using the terminology of our values-based operational framework. Participatory observations as a volunteer or consumer ensued on multiple occasions at each market and notes were coded and analyzed. These experiences—e.g., helping one Viennese farmer sell at his stand, or volunteering to promote a market’s mission in Minneapolis by explaining and demonstrating a new compost and recycling system—built rapport between the researcher and market staff, managers and vendors. These experiences also offered opportunities to raise follow-up questions with all FM participants.

While there is an abundance of literature about FM consumers in the US, no scientific literature concerning Austrian FM consumers exists. To obtain a better view of FM consumers in Vienna, six dot-surveysFootnote 5 were run at each of the FMs examined in this study.Footnote 6 These dot-surveys were the first ever directed in Austrian markets and were conducted in the summer of 2014 on the days with the highest consumer numbers.

The individual FM cases were chosen to show maximum variability of values and OS among FM samples in both regions. The two case study regions with six case markets in each region allowed us to acquire a wide range of perspectives from key FM stakeholder groups. The markets were selected based on similarities in size, popularity, and demographics. The OS and values found in the six markets of each metropolitan area resulted in theoretical replication—predicting contrasting results for probable reasons—of each market region (Yin 2013).

Before examining the FM values and their alignment between FM participant groups in Minneapolis and Vienna, we present an overview of each market region.

Viennese and Minneapolis market descriptions

Vienna

The first officially recognized market in Vienna was in 1671, but historical records list markets in Vienna as early as 1151. The majority of Vienna’s 22 markets share this long history.

The City of Vienna governs and regulates all of the municipal markets through the same department that is responsible for regulating supermarkets, restaurants, etc. This city department, not the market managers directly, is responsible for most decision making and allocation of funds for the FMs. Thus, implementing any substantial changes results in the necessity of navigating bureaucratic avenues that can be lengthy and complex.

Most of the markets have separate, designated and outdoor spaces for farmers and temporary vendors. Until the 1970s and 1980s, farmers and local processors rented a majority of the permanent public market stands in Vienna. But today, as market stand rent has risen, only restaurants and re-sellers can afford them. This trend, in addition to competition from supermarkets, has led farmers largely to occupy the temporary stands. Furthermore, most markets in Vienna now attract fewer farmers. The markets have reduced the space available for temporary stands—or what is now called the “farmers market” in each public market—as well as the number of days open. Because this FM portion of the municipal markets is temporary and relatively small, market managers focus more on the “permanent” stands, rather than the FM section of the municipal market.

As municipal employees, the market managers are responsible principally for enforcing health and safety regulations and for overseeing market operations such as stall organization and distribution. Market managers do not have a mission statement that provides a unifying image of the markets. Yet when questioned a second time, they stated that an unofficial goal of the markets is to provide access to safe and hygienic food. The managers are primarily responsible for enforcing the municipal regulations and there are municipal rules for avoiding favoritism and corruption in market operations. Farmers and re-sellers are chosen through a lottery system to ensure a fair chance to sell with preference to actual farmers. The application of this regulation makes it almost impossible to gear the market to consumer needs or wishes; it sometimes leads to imbalances in the variety of products at the markets that can be damaging to market attractiveness.

FM regulations, governance structures and a division among governmental sectors in Vienna, often prevents managers from making improvements such as product and producer transparency, advertising and marketing. This results from the fact that managers are hired by the city and the relationships between the managers and the farmers are often influenced by partisan political priorities. Since the political orientation of city officials is quite different from that of most farmers (and the national Bureau of Agriculture), bi-partisan cooperation to unify the individual market image, support farmers and create a sense of community is rare. The restricted role of the market manager affects both the farmers—because they do not receive additional needed support—and consumers—because their preferences are rarely integrated at the market level.

Minneapolis

Farmers markets from the early twentieth century in the US—and subsequently in Minnesota—were public or municipal, similar to those in Vienna today. They typically had permanent infrastructure, were found principally in larger metropolitan areas and served primarily as wholesale markets for food retailers (Stephenson 2008). Today, producer-only restrictions are a hallmark of FMs in the US, with many open solely to grower-only sales. Minneapolis markets focus chiefly on retail sales in an open-air, temporary-style market. This form of market represents all but one of the 13 FMs present in Minneapolis. Each market has its own purpose, or mission statement commonly focusing on social or ecological goals relative to its surrounding community. Each market manager organizes weekly events and educational activities consistent with their goals and to create an atmosphere and overall public image of the market.

In Minneapolis, a non-profit organization or a neighborhood association typically governs and employs FM managers. Decisions are made for each FM through a board of directors. Each FM varies in the level of involvement accorded to their farmer/vendors on that board. The city conducts state health and regulation inspections, but remains independent of the FM governance structures. FM managers are responsible for attending board meetings and for day-to-day operational matters, including FM promotion and advertising. These activities vary from market to market, but they often include: themed events, food demonstrations, music, education, and community stands that rotate each week. They showcase themes such as composting, biking, gardening, nutrition, physical health, and farming among others. Overall, FM managers pay considerable attention to consumer concerns and demands.

All of the Minneapolis FMs have rules restricting the re-sale of food, and most allow a small number of additional craft and restaurant stands. Consistent with market policy, the FMs give precedence to local or regional farmers. Almost all farmer vendors are from central Minnesota or western Wisconsin. Many are young, innovative, or organic and value the ability to sell their products directly to their consumer. This includes building consumer relationships based on trust, quality and communication.

Metropolitan farmers market values in Vienna and Minneapolis

This section presents and discusses the values found and embedded in the two metropolitan market regions; shows how the values are embodied as rules and norms in each set; considers the alignment or not of FM participant values with their corresponding FM values; and compares these findings between the two different metropolitan areas.

A descriptive analysis of the values found in the norms and rules of the different FM regions is organized below into the value categories of health, ecology, fairness and care. Due to the interconnected nature of the values, some values found overlap with others. Therefore, we organized the values into the category that represented them most frequently.

In this section we discuss and compare the most prevalent (i.e., frequency, visibility) and seemingly influential (i.e., possible impact) FM values while taking into consideration the particular OS and key participants of the different market regions. To illustrate these similarities and differences of the metropolitan markets, we give specific descriptive examples of selected rules and norms embedded only in the purpose of each different market type in tables below. The purpose of a FM is critical since it both holds together and influences the other features of a FM structure and is manifested in FM practices.

Both tables—Table 1 for Vienna and Table 2 for Minneapolis—first show the value categories in which the rules and norms of the FMs are organized; second describe the type of rules or norms; and then list examples of how such rules and norms are represented through the practices and understandings of the FMs themselves.

Values, rules and norms in the Viennese markets

Health

Since the managers prioritize the purpose of all of the Viennese markets to provide access to safe and hygienic food, they carefully regulate the markets for these qualities. Yet, it is important to note that their job is to do this not only at FMs, but for the entire Viennese food system. As one manager explains: “My main priority is not the Viennese farmers markets. My main duty is to control the safety of all food in Vienna…whether this be from a supermarket, a large meat processing plant or at a farmers market stand”. More than one manager stated that their inspections and regulations ensure the freshness and quality of products being sold at the markets, which is a notion that all FM participant groups linked to health (Table 1).

Care

The success and future of FMs are often linked with fiscal matters. The FMs in Vienna are funded by the city and managers do not need to spend time finding sponsors. As noted above, this form of governance discourages farmer participation and weakens transparency and information exchange with consumers. Viennese managers are neither concerned with the number of farmers at the markets nor responsible for market advertising. As a result, innovation, education and promotion of FMs tend to come from outside actors—i.e. organizations, individuals or other governmental bureaus. As one FM manager expressed: “What the markets need are more people who have experience and information about food and diet that can come here and shop with a goal and shop critically. That is something that we cannot directly influence. Such a possibility has to come from above, from the state agricultural or business bureaus, or also from schools and academic directions. They [these outside actors] should be spreading propaganda to create awareness about such issues so that a customer can look over the facts and information”.

The recent involvement of a local political figure in Vienna, leading a few cooking demonstrations in the markets illustrates this kind of outside support. Such organizing is incredibly time consuming and likewise costly, especially when organizing with multiple governmental sectors, and often does not occur at the managerial level.Footnote 7 As the priority of the markets is not the education of an informed consumer base or farmer support, and because the Viennese economic bureau is solely responsible for marketing, organizing such market activities is minimal.

Viennese FM farmers come predominantly from families that have been at the markets for generations or are selling as a family endeavor. These vendors, concerned with the competition from supermarkets, are often adverse to change and view their generally small farm size as an impediment to their future. They often speak about being the last generation able to make a living from this way of selling: “Small farms are dying out, soon there won’t be any small farmers left”.

There is, however, a small group of innovative, alternative farmers and producers seeking to re-introduce direct marketing, specifically by focusing on new consumer trends and enhancing their market image. There are significant differences in farmer/vendor opinions about what the purpose of the Viennese FMs is or should be. Although farmers, as one farmer described, believe that “Farmers markets are great instruments for small farmers,” farmer numbers are dwindling in Viennese FMs. This has created farmer interest in advertising for small farmer support and FM participation, specifically associated with values surrounding trust, tradition and quality. Throughout the interview process, the farmer/vendor participant group made clear that FM management should do more for small farmers through marketing and advertising.

Viennese consumers are rapidly shifting away from more customary practices of daily shopping and cooking—indicative of family structures following more conservative gender roles—to eating regularly from street stands and restaurants, leaving weekends for food procurement and preparation. Viennese consumers express interest in supporting small farmers, local products and receiving information concerning farm practices and products (Zander et al. 2010). They are also concerned with nutrition, organic, local, sustainable, animal welfare, and food safety. Consumer interest demonstrates a broader spectrum of values than expressed by most managers and farmers in the Viennese FMs, and don’t align with these FM participant groups. The dot survey enabled us to understand consumer beliefs that markets should be largely made up of actual farmers. Forty-seven percent of consumers believe that having more farmer presence would motivate them to visit the markets more frequently (consumers often suppose that the majority of current vendors are farmers). As one market manager stated: “Consumers only come [to the public markets] because of the farmers”. Underlining such values of the support of farmers, the dot survey also showed that one-half (49%) of consumers are interested in education concerning the specific farmers and their products as well as farming in general.

Ecology

Issues such as environment and sustainability are not often directly emphasized in the FMs of Vienna. However, a strong organic presence exists and one market requires vendor organic certification. Although FM consumers acknowledge price differences, many consider organic to be very important. Although already widely available, nearly 20% of dot-survey participants expressed interest in increasing organic product availability.

Fairness

Temporary spaces for FM stands are assigned through a lottery system with priority given to farmers over resellers. This, however, may lead to a lack of product diversity because this system leaves who sells in the market open to chance instead of selecting vendors based on more consumer-oriented concerns. During the interviews some saw this factor as problematic: “The market needs advertisement and then more advertisement and diversity is missing at our market. Basically half of the market [around 60 stands] sells vegetables and the other half fruit”. Another concern involves building market transparency—particularly so consumers can readily distinguish non-farmer from farmer vendors. This, as well as organizing consumer events in support of farmers, are recognized as difficult to broach at the managerial level, however necessary: “We have the problem that there are fewer and fewer farmers and gardeners [at the FMs], but the market managers can’t do anything. They can’t support the farmers, so we need support from the government”.

Values, rules and norms in Minneapolis markets

In contrast to the FMs of Vienna, each Minneapolis market has a different purpose and governance structure. Although subject to some municipal and state regulations each market is run independently from the others. This encourages and enables different values and characteristics that are place-based and appeal to the differing communities and consumers (Table 2).

Care

This is expressed through community and education and both purposes are highlighted, albeit differently, throughout all Minneapolis FMs. They are expressed in governance processes by market managers and affect each market participant, consequently shaping the character of each market. As expressed by one FM manager: “We make sure that the farmers themselves are there, standing behind their booths so that there can be that kind of organic conversation…so that learning can happen and people can understand the true value of food, both the price and the [normative] value”. Additionally, market sponsors sharing such values as community and education offer significant additional revenue to the markets, allowing for the hiring of an independent (from city and health regulators, vending and farming) market manager. These managers are often responsible for organizing related programing.

The work invested by managers to integrate purpose-based values such as care of small farmers and community building is largely responsible for farmers and consumers sharing nearly all values embodied in the FMs of Minneapolis. A market manager illustrates this here: “They [farmer/vendors] like to be at a market that is curated because they are doing better business. Because we don’t have so much competition, I think that their ability to do higher sales being surrounded by other vendors who have the same values and farming practices [is an incentive]”.

Consumers are a high priority for Minneapolis FMs. All markets seek to comply with consumer wishes. Most include in their purposes the economic support of small farmers, and consumer education on food and farming issues (Holloway and Kneafsey 2000; Brown 2002). Consumer values are constantly gauged and applied to the markets. Consumer attitudes differ from farmer values on pricing—particularly for organic products. Consumers at the Minneapolis FMs are not necessarily looking for bargains, but are focused on issues of health, farmer support, and participating in a festive atmosphere with music and interactive educational activities. The market is seen as an experience—a way to spend Saturday or Sunday morning with family or friends. The majority of consumers do not procure their weekly food needs solely at the FMs. Instead, most FM customers supplement their normal supermarket purchases or purchase niche products as gifts.

Fairness

This is illustrated through the inclusion of vendors in governance positions (albeit to varying degrees among the 6 FMs), and in aligning market purposes and values of fairness among participant groups. As one manager states: “…we have a board of directors in which one farmer is part of [who represents the farmers and has voting power] and then a vendor advisory committee, which is to make sure that we are doing our jobs…to make sure we are taking everything into consideration”. In many Minneapolis markets, managers now make annual farm visits to ensure that products being sold are local and grown sustainably. Additionally, there has been a considerable effort in the past decade to address issues of food accessibility and affordability. This is especially evident through the integration of EBT participants at FMs.

Each participant group however, expresses some concerns. Farmer/vendors stated the need for further education or communication about the fairness of prices for products in relation to what farmers (small farmers in particular) actually earn and what they need to earn. Part of this concern stems from a perceived imbalance of food-truck and prepared food items to fresh produce or products from actual farmers represented at the markets. Often farmers will see shoppers pay more at food vendors then for their fresh products. A new farmer at a Minneapolis FM described this situation: “Because industrial priced chickens are so low, our chicken prices shock people at first. Yet, people who are dumbstruck at two chicken breasts for $17, go ahead and spend $12 on their pizza and pop. That is one meal for one person and at the stall right next door”. In some markets, farmers would like to see a more clear and transparent distinction made between small farmers and resellers: “…as a small farmer, to have the quantity that you need to make it is a tremendous pressure, and so have they [other vendors] crossed the line when they have started to buy from other people and just resell those people’s product? You start to have to really do some serious questioning…”. This farmer highlights issues of re-selling and a possible inequality among farm sizes accepted at FMs because small farmers often cannot compete with lower prices set by larger farms. Another concern includes farmers reporting having financial difficulty, especially in the beginning of the season. Younger farmers looking for permanent land or paying off machinery and equipment loans seem to balance these difficulties through their emotional feelings of ‘doing good’, introducing people to real food through the shortest supply chain possible and creating community.

Health

Aside from education on healthy eating and cooking demonstrations highlighting practical meals, many who sponsor FMs, such as local health insurance companies or clinics, do so specifically to promote their values with similar FM values, such as fresh, healthy food. This type of partnership encourages cooperation at deeper levels—e.g., through reduced health care premiums for market goers. Additionally, one FM exists solely because its governance system believes that FMs are healthy for its employees (this market is open to the public, but run by the University of Minnesota’s human resources department’s health and wellness program): “The farmers market really supports several of our wellness program objectives: to support the health and wellbeing of the University workforce, employees and their dependents; to make the university a good place to work; and to control U-plan health program costs”.

Ecology

This is illustrated primarily in educational activities at the market promoting local and organic foods, gardens, biodiversity, biking, composting and recycling (typically in the form of the ‘zero-waste’ project where all waste created at the FMs is compostable). Organic farming at FMs does not come without complications. Most farmer/vendors are regional (that is, from Minnesota or western Wisconsin), and many are organic. However, consumer beliefs that local and organic products are one and the same are a source of frustration for many organic farmers. Distinguishing these values from each other is difficult within the market arena; in highlighting one, you may undermine another, raising potential conflicts among vendors.

Generally consumers’ values are well managed as the Minneapolis markets perform similar to purpose-based businesses. They closely follow consumers’ wishes and attract them by marketing such values as atmosphere, education, and entertainment to product variety and quality.

Value alignment in Vienna and Minneapolis

The development trajectories of these two market regions are dictated both by their purposes and their resulting OS. Together, as purpose encompasses the values of the markets, these aspects have a reciprocal influence on each other in affecting general FM character and behaviors. In concentrating on purpose, differences in the amount, quality and variety of FM values between Minneapolis and the Viennese FMs are discernable. For example, all Viennese FMs focus on safety and hygiene, whereas each Minneapolis FM reflects individual interests and values, such as sustainability, farmer support, social justice or the offering of fresh products to a neighborhood. Ultimately, the success of a FM is dependent on its ability to motivate its consumers (Betz and Farmer 2016) and embody and react to current cultural and political changes such as consumer habits, trends, and surrounding environments (Stephenson 2008). The ability of a FM to respond to such changes is linked closely with how decisions are made within a FM system. Therefore it should be clear that FM governance structures and their interplay with their purpose(s)—and subsequent values—are crucial for the future of FMs.

Regardless of country, the alignment of FM marketing strategies to its consumers’ preferences and motivations is important to its success (Andreatta and Wickliffe 2002, p. 168). This alignment is highly dependent upon what Mount (2012) describes as ‘reflexive governance’ capabilities. This describes a governance structure choosing a form favoring negotiation over restrictions, and allowing for a flexible and adaptable structure responding to future changes and challenges. As Mount states: “…this approach enhances the potential to bring together in open discussion producer and consumer perspectives that are often the product of speculation—exposing a broader audience to the full diversity of reasons for participation in an alternative system” (p. 116).

The main disconnect in value alignment of Viennese FMs to those of consumers is perhaps best illustrated by the more traditional market form and governance structure. The OS of Viennese markets reflects archaic FM practices—e.g., by functioning as if they are still the main source of food procurement and assuming that consumers still shop and cook daily. This influences projected values by the FM managers and the system itself. Most significant in the Viennese markets and their OS is the inflexible role of governance, or using Mount’s description, a non-reflexive governance system. The narrow range and type of values embodied in the Viennese FM system stems from detachment between FMs and their stakeholders. Vendors have little to no influence on the markets themselves, nor are they regularly and formally asked for their opinions or preferences. Thus Viennese vendors address consumers individually rather than through the market. FM managers interact with consumers chiefly in ensuring safety and hygiene. As a result of this governance form the purpose of the Viennese markets lack embodied participant—i.e., farmer and consumer—values. Therefore FM rules and norms reflect only the values stemming from managerial and regulatory priorities. This misalignment drives the Viennese market purpose, not necessarily reflecting the varying local market environments and their cultural and political influences.

The slower development of the Viennese FMs into markets that encompass more modern trends is apparent to the managers through the difficulty of making visible changes to the FMs. One manager explained the consequences of the declining number of producers: “The market is only alive when the farmers are there”. As older, more traditional vendors retire, the rate of transition to new farmers is very slow, and often surpassed by resellers. This creates a market unsupportive of consumer values related to farming and its future.

Currently a worldwide movement of alternative consumers concerned with food safety, health, animal welfare, price, availability and social and environmental interests has been identified (Carey et al. 2011; Falguera et al. 2012; Lappo et al. 2013; Spaargaren et al. 2013). These common patterns in global alternative food consumption align with the primary values found in FM consumers in Minnesota and Vienna. The growing discussion of values related to food consumption in both regions (Kirwan 2004; Vermeir and Verbeke 2006; Zander et al. 2010; Schermer 2015) highlight the reciprocal relationship between FM values and consumers. This relationship is exemplified in FM values that both influence and are influenced by consumer preferences and their purchasing habits.

Our dot survey results in Vienna illustrate that consumers have different ideas about the purpose of the FMs than do the actions of the managers. Consumer preferences and motivations are becoming rapidly similar to those in Minneapolis. Changing consumption habits add to significant contemporary issues influencing farmers and FM vendors, such as values of health, education, and farmer support, which are principle priorities for Viennese consumers. Therefore, the results show that values have differing roles in FMs in Vienna and Minneapolis even though there are similar consumer preferences and motivations within both metropolitan regions.

Here we have learned that not only are values influential in FM success, but even more beneficial are the shared values aligned among FM participant groups. The differences between the two FM regions highlight the importance of having an OS that particularly includes a flexible governance structure ultimately allowing for improved alignment of FM participant values. Aligning the values and purposes of different FM participant groups ensures a successful market not only because consumer wishes are met but, due to the ability of a FM to support farmers both financially and politically in creating an educated consumer base, it is both supporting its vendors and perpetuating the FM.

Lessons learned from outlier farmers markets

The markets in Vienna and Minneapolis have considerably different histories and each reveals a decidedly different set of priorities and understanding of the values embodied in the markets. They have differing purposes, missions or goals. FMs in Vienna serve predominantly as spaces for everyday food procurement. Those in Minneapolis are mission-oriented and exhibit many values related to environmental and social concerns; reflect multiple-stakeholder values and trends, including a broader awareness of food and farming issues. In contrast to those in Vienna, the Minneapolis markets are focused on their alterity—or their alternativeness—from conventional groceries and supermarkets (Kirwan 2004; Smithers et al. 2008). Such differences are congruent in the few existing cross-cultural FMs studies (Vecchio 2010).

In each market region we identified one ‘outlier’ FM whose OS did not match those of the other markets in their region. These two exceptions underline the distinction between these two sets of markets and provide an interesting contrast to the other FMs in their metropolitan regions. In Minneapolis, the historical Minneapolis FM is municipally owned with permanent infrastructure and thus orients itself more toward the Viennese markets. This FM is the largest in Minnesota with a past paralleling many of the Viennese markets. This market illustrates the benefit of adapting its purposes to integrate certain contemporary characteristics, to compete with surrounding FMs in the area and meld with consumer wishes. It does so by mimicking smaller FMs in the metropolitan area in adapting a more modern purpose, an extensive social outreach program and limiting the amount of resellers allowed at the market. This exemplifies a possibility for modernizing the more traditional markets of Vienna and aligning their values with their FM participants.

In Vienna a temporary all-organic market, organized by an organic association is the exception to the rule. This market’s purpose differs from the other markets, as it requires organic certification. Complete with a different governing system in addition to the Viennese managers, an association manager supports and enforces their organic vision and organizes market events and themes. This market shares more FM characteristics with the Minneapolis FMs, thus illustrating an exception to markets in Vienna as a second possible way of modernizing their markets. These outliers prove useful for future FM strategies not only in Vienna but also in other European countries sharing similar systems—showing different innovative techniques to successfully maneuver through their respective systems.

Reflecting larger trends in their regions, the more traditional market form of Viennese markets are common among municipal regions throughout continental Europe—e.g. in France, Spain, and Italy—and are often linked with public markets (Vecchio 2009, 2010). Likewise, the more contemporary FM model predominant in Minneapolis is common and growing throughout metropolitan markets in the U.S. (Stephenson 2008; Alkon 2012). Although the results from these FM examples are not to be over-generalized, they offer cross-cultural suggestions as how to integrate purposes that are values-based within municipal FMs and that can help a market align their values among all FM participant groups.

Conclusions

This paper compares two different metropolitan FM regions within their place-based contexts and discusses how to understand the role that values play within them. Our interest was to understand the relationship between the values of different FM participant groups, how they are related to their FM operating structures, and how their alignment might influence their development. We found that FM value sets are complex and differ among and within FM participant groups, and that they are dependent upon their respective OS. We have shown that contrasting two FM regions can be useful in understanding beneficial and disadvantageous relationships between the values and structures of, and in FMs, and specifically in examining institutional impediments such as governance.

Our values-based comparative operating framework, reflecting the relationships among the FM operating structures and values, has helped to address four issues (1) the values found and embedded in the two metropolitan market regions; (2) how the values are embodied as rules and norms in each FM set; (3) the alignment of FM participant values with their corresponding FM values; and (4) the differences and commonalities as well as the benefits and challenges of the Viennese and Minneapolis metropolitan FMs. The resulting picture of each FM region—despite individual FM differences within each region—has served to descriptively distinguish the two market regions.

We have shown that values—particularly non-economic—are present in all main FM participant groups (market managers, farmer/vendors and consumers) and that communication, exchange and actualization of these values among and between each group is influential in the success of FMs. We also confirmed that Minneapolis FMs draw upon their alterity and align their values with those of their consumers and farmer/vendors. In contrast, FMs in Vienna have cumbersome governance structures impeding their recognition as an alternative to the dominant food system. Recent FM growth and successes have shown their transformative powers in numerous other countries. The traditional FMs of Vienna, due to many of their OS characteristics, particularly their governance, seem to make beneficial changes in FMs politically and bureaucratically improbable. However, Viennese markets undoubtedly have the potential to act as a challenging social movement by drawing upon the regional smallholder farming structure still intact; consumers who wish to support small farmers; and by remaining independent of sponsorship through municipal funding.

Mount (2012) cautions that shared goals and values within local food systems (LFS) provide a basis for ‘reconnection’ an added value of LFS itself, but how values are produced and how LFS are governed are to be taken into consideration. Our framework allowed for a similar understanding of a balance of values and governance but it might also provide other alternative food system researchers or market managers with a process in which they can address, reflect, and define their purposes. Although offering insight on FM purpose, use of the framework can be expanded to include other concepts from its basis—i.e., membership, governance, finance and marketing, and networking. In using the framework in its entirety it presents a comprehensive approach to the conceptual development of FMs studies in joining functions and values. This combination of OS and the IFOAM principles makes actors aware of common values and how they can best be aligned throughout the different FM participant groups. It seems particularly powerful when repeatedly reflected upon by actors in that through the remembrance of such values and through community participation in nurturing them, motivation to continue can be sustained (Feenstra 2002).

By shifting FM research away from solely economic and consumer focused topics, this framework brings to the foreground the importance of non-economic values in FMs among all major FM participant groups. Finally, in doing so, this research fills several gaps in existing FM literature: the values of FMs—including those of consumers, farmer/vendors and market managers—and their roles within FMs; what this understanding offers for more traditional markets, such as those in Vienna, struggling with identity and a changing consumer base; and general gaps in current studies of metropolitan FMs, especially those of cross-national nature.

Notes

This draws upon Polanyi’s concept of social embeddedness that identifies how economic activity is embedded within social structure. That is, non-economic factors play a key role in how a system functions and gives us a holistic approach to understanding, in our case, farmers markets (Polanyi 1944; Polanyi et al. 1971).

These concepts are derived from Marjorie Kelly’s Architecture of Ownership the foundation of her Generative Ownership concept (Kelly 2012). Generative ownership explores a set of patterns and designs of ownership that have a purpose of serving the common good. This framework attempts to draw out values of social and ecological benefit within ownership models.

International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements, in which organic agriculture should: Health: sustain and enhance the health of soil, plant, animal and human as one and indivisible. Ecology: be based on living ecological systems and cycles, work with them, emulate them and help sustain them. Fairness: build on relationships that ensure fairness with regard to the common environment and life opportunities. Care: be managed in a precautionary and responsible manner to protect the health and well-being of current and future generations and the environment (IFOAM 2014).

The focus of values also allows us to avoid the reductionist thinking that many alternative food systems researchers and organizers fall into, namely that successful economic market activity is the main vehicle to approach change in food systems (DeLind 2011).

Dot-surveys were originally developed in the US specifically for FMs by Lev and Stephenson (see Lev et al. 2007, 2008). They collect FM data from consumers through a limited number of closed-questions set up on easels where consumers indicate their answers with ‘dot’ stickers. These surveys are popular with consumers because of their interactive and quick manner. Many Viennese consumers took the opportunity to elaborate their opinions and ask questions, all of which was documented.

Information concerning consumers in both regions was obtained from literature, interviews, participatory observation and dot-surveys. All but one of the Minneapolis FMs already had existing dot-survey data on hand—some of them directed annually, in which we helped conduct one.

Since the time of data collection, more organizations have shown interest in using market space for community events, helping to bolster a community feel and bring in more potential consumers to the Viennese FMs, yet they are rather ad hoc and haven’t specifically approached farmer awareness or reached the level of involvement and organization of the Minneapolis markets.

Abbreviations

- EBT:

-

Electronic benefit transfer

- CSA:

-

Community supported agriculture

- FM:

-

Farmers market

- IFOAM:

-

International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements

- LFS:

-

Local food systems

- OS:

-

Operating structure

- SNAP:

-

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

- US:

-

United States

References

Alkon, A.H. 2008. From value to values: Sustainable consumption at farmers markets. Agriculture and Human Values 25(4): 487–498.

Alkon, A.H. 2012. Black, white, and green: Farmers markets, race, and the green economy. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Alkon, A.H., and C.G. McCullen. 2011. Whiteness and farmers markets: Performances, perpetuations… contestations? Antipode 43(4): 937–959.

Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS), USDA. 2014. Farmers Market and Local Food Marketing. http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/ams.fetchTemplateData.do?template=TemplateS&leftNav=WholesaleandFarmersMarkets&page=WFMFarmersMarketGrowth&description=Farmers Market Growth. Accessed 28 Aug 2014.

Andreatta, S., and W. Wickliffe. 2002. Managing farmer and consumer expectations: A study of a North Carolina farmers market. Human Organization 61(2): 167–176.

Baker, D., K. Hamshaw, and J. Kolodinsky. 2009. Who shops at the market? Using consumer surveys to grow farmers’ markets: Findings from a regional market in northwestern Vermont. Journal of Extension 47(6): 1–9.

Beckie, M.A., E.H. Kennedy, and H. Wittman. 2012. Scaling up alternative food networks: farmers’ markets and the role of clustering in western Canada. Agriculture and Human Values 29(3): 333–345.

Berry, J., B. Moyer, and L. Oberholtzer. 2013. Assessing training and information needs for Pennsylvania farmers markets: Results from a 2011 survey of market managers. Journal of the NACAA 6(1). http://www.nacaa.com/journal/index.php?jid=194.

Betz, M.E., and J.R. Farmer. 2016. Farmers’ market governance and its role on consumer motives and outcomes. Local Environment 21(11): 1420–1434.

BMLFUW. 2016. Grüner Bericht. eds. Umwelt und Wasserwirtschaft Bundesminesterium für Land- und Forstwirtschaft. Wien, Bundesminesterium für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Umwelt und Wasserwirtschaft. https://gruenerbericht.at/cm4/. Accessed 2 Aug 2016.

Brown, A. 2001. Counting farmers markets. Geographical Review 91(4): 655–674.

Brown, A. 2002. Farmers’ market research 1940–2000: an inventory and review. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture 17(4): 167–176.

Brown, C., and S. Miller. 2009. The impacts of local markets: a review of research on farmers markets and community supported agriculture (CSA). American Journal of Agricultural Economics 90(5): 1298–1302.

Byker, C., J. Shanks, S. Misyak, and E. Serrano. 2012. Characterizing farmers’ market shoppers: a literature review. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition 7(1): 38–52.

Carey, L., P. Bell, A. Duff, M. Sheridan, and M. Shields. 2011. Farmers’ Market consumers: a Scottish perspective. International Journal of Consumer Studies 35(3): 300–306.

Colasanti, K.J.A., D.S. Conner, and S.B. Smalley, 2010. Understanding barriers to farmers’ market patronage in Michigan: perspectives from marginalized populations. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition 5(3): 316–338.

Connell, D.J., J. Smithers, and A. Joseph. 2008. Farmers’ markets and the “good food” value chain: a preliminary study. Local Environment 13(3): 169–185.

DeLind, L.B. 2011. Are local food and the local food movement taking us where we want to go? Or are we hitching our wagons to the wrong stars? Agriculture and Human Values 28(2): 273–283.

Falguera, V., N. Aliguer, and M. Falguera. 2012. An integrated approach to current trends in food consumption: Moving toward functional and organic products? Food Control 26(2): 274–281.

Farmers Market Coalition. 2014. Farmers markets grow economies and jobs. http://farmersmarketcoalition.org/economic-engines-8-7-2012. Accessed.8 Aug 2012.

Feagan, R.B., and D. Morris. 2009. Consumer quest for embeddedness: a case study of the Brantford farmers’ market. International Journal of Consumer Studies 33(3): 235–243.

Feagan, R., D. Morris, and K. Krug. 2004. Niagara region farmers’ markets: local food systems and sustainability considerations. Local Environment 9(3): 235–254.

Feenstra, G. 2002. Creating space for sustainable food systems: Lessons from the field. Agriculture and Human Values 19(2): 99–106.

Gantla, S. 2014. The impact of farmers market ownership on conduct and performance. Oregon: Masters thesis,.Department of Public Policy, Oregon State University in Eugene.

Gantla, S., and L. Lev. 2016. Farmers’ market or farmers market? Examining how market ownership influences conduct and performance. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 6(1): 49–63.

Gillespie, G., D.L. Hirchey, C.C. Hinrichs, and G. Feenstra. 2007. Farmers’ marktes as kestones in rebuilding local and regional food systems. In: Remaking the North American food system; Strategies for sustainability eds. Clare Hinrichs and Thomas A Lyson, 65–83. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Govindasamy, R., M. Zurbriggen, J. Italia, A.O. Adelaja, P. Nitzsche, and R. Van Vranken. 1998. Farmers markets: Managers’ characteristics and factors affecting market organization. AgEcon Search. http://purl.umn.edu/36723. Accessed 16 Nov 2015.

Gutes vom Bauernhof. 2016. Studie: Direktvermarktung in Österreich 2016. https://www.gutesvombauernhof.at/uploads/pics/Oesterreich/ChanceDV/PB_Chance_DV-Studie_Berichtsband-Charts_20160606.pdf. Accessed 19 June 2016.

Hinrichs, C.C. 2000. Embeddedness and local food systems: notes on two types of direct agricultural markets. Journal of Rural Studies 16(3): 295–303.

Hinrichs, C.C., G.W. Gillespie, and G.W. Feenstra. 2004. Social learning and innovation at retail farmers’ markets. Rural Sociology 69(1): 31–58.

Hofmann, C., J.H. Dennis, and M. Marshall. 2008. An evaluation of market characteristics for Indiana farmers’ markets. Dallas, TX: Conference Paper. SAEA annual meeting

Holloway, L., and M. Kneafsey. 2000. Reading the space of the farmers’ market: a preliminary investigation from the UK. Sociologia Ruralis 40(3): 285–299.

Hughes, D.W., C. Brown, S. Miller, and T. McConnell. 2008. Evaluating the economic impact of farmers’ markets using an opportunity cost framework. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics 40(01): 253–265.

IFOAM. 2014. Principles of organic agriculture. The four principles. http://www.ifoam.org/en/organic-landmarks/principles-organic-agriculture. Accessed 30 Aug 2014.

Kelly, M. 2012. Owning our future: The emerging ownership revolution. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Kirwan, J. 2004. Alternative strategies in the UK Agro-food system: Interrogating the alterity of farmers’ markets. Sociologia Ruralis 44(4): 395–415.

Kirwan, J. 2006. The interpersonal world of direct marketing: examining conventions of quality at UK farmers’ markets. Journal Of Rural Studies 22(3): 301–312.

La Trobe, H. 2001. Farmers’ markets: consuming local rural produce. International Journal of Consumer Studies 25(3): 181–192.

Lev, L., L.J. Brewer, and G.O. Stephenson. 2008. Tools for rapid market assessments. OSU Scholar Archive. http://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1957/8665/SR_no.1088_ocr.pdf?sequence=4 Accessed 15 March 2014.

Lev, L., G. Stephenson, and L. Brewer. 2007. Practical research methods to enhance farmers’ markets. In Remaking the North American food system; Strategies for sustainability, eds. C. C. Hinrichs, and T. A. Lyson, 84–99. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Lappo, A., T. Bjørndal, J. Fernandez-Polanco, and A. Lem. 2013. Consumer trends and prefences in the demand for food. Institute for Research in Economics and Business Administration. http://hdl.handle.net/11250/225387. Accessed 24 Jan 2016.

Moore, O. 2006. Understanding postorganic fresh fruit and vegetable consumers at participatory farmers’ markets in Ireland: reflexivity, trust and social movements. International Journal of Consumer Studies 30(5): 416–426.

Morris, C., and J. Kirwan, 2011. Ecological embeddedness: An interrogation and refinement of the concept within the context of alternative food networks in the UK. Journal Of Rural Studies 27(3): 322–330.

Morris, C., and C. Young. 2000. `Seed to shelf’, `teat to table’, `barley to beer’ and `womb to tomb’: discourses of food quality and quality assurance schemes in the UK. Journal Of Rural Studies 16(1): 103–115.

Mount, P. 2012. Growing local food: scale and local food systems governance. Agriculture and Human Values 29(1): 107–121.

Payne, T. 2002. US farmers markets, 2000: A study of emerging trends. United States Department of Agriculture: Marketing Services Branch. Agcon search: http://ageconsearch.tind.io//bitstream/27625/1/33010173.pdf. Accessed 7 Aug 2014.

Polanyi, K. 1944. The great transformation: The political and economic origins of our time. Boston: Beacon Press.

Polanyi, K., C.M. Arensberg, and H.W. Pearson. 1971. Trade and market in the early empires: economies in history and theory. Washington, DC: Henry Regnery Company.

Rimal, A., B. Onyango, and J. Bailey. 2010. Farmers markets: Market attributes, market managers and other factors determining success. Agecon Search. http://ageconsearch.tind.io//bitstream/61651/2/FarmersMarket_aaea_10.pdf. Accessed 15 Nov 2015.

Sage, C. 2003. Social embeddedness and relations of regard: alternative ‘good food’networks in south-west Ireland. Journal Of Rural Studies 19(1): 47–60.

Schermer, M. 2008. The decline of farmers direct marketing in austria: consequences and counter strategies. In: Proceedings of the 8th European IFSA symposium eds. B. Dedieu and S. Zasser-Bedoya, 211–220. Clermont Ferrand.

Schermer, M. 2015. From “food from nowhere” to “Food from here:” Changing producer–consumer relations in Austria. Agriculture and Human Values 32(1): 121–132.

Smithers, J., J. Lamarche, and A. Joseph. 2008. Unpacking the terms of engagement with local food at the farmers’ market: Insights from Ontario. Journal Of Rural Studies 24(3): 337–350.

Spaargaren, G., P. Oosterveer, and A. Loeber 2013. Food practices in transition: changing food consumption, retail and production in the age of reflexive modernity. London: Routledge.

Stephenson, G.O. 2008. Farmers’ markets: success, failure, and management ecology. Amherst, NY: Cambria Press.

Vecchio, R. 2009. European and United States farmers’ markets: similarities, differences and potential developments. In presentation at the 113th EAAE Seminar “A resilient European food industry and food chain in a challenging world”. Chania, Crete.

Vecchio, R. 2010. Local food at Italian farmers’ markets: three case studies. International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food 17(2): 122–139.

Vermeir, I., and W. Verbeke. 2006. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude–behavioral intention” gap. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 19(2): 169–194.

Winter, M. 2003. Embeddedness, the new food economy and defensive localism. Journal Of Rural Studies 19(1): 23–32.

Yin, R.K. 2013. Case study research: Design and methods. London: Sage publications.

Zak, P.J. 2008. Values and value: Moral economics. In: Moral markets: The critical role of values in the economy, ed. P.J. Zak, 259–279. Princeton, MA: Princeton University Press.

Zander, K., U. Hamm, B. Freyer, K. Gössinger, M. Hametter, S. Naspetti, S. Padel, H. Stolz, M. Stolze, and R. Zanoli. 2010. Farmer consumer partnerships-how to successfully communicate the values of organic food. Kassel, DE: Department of Agricultural and Food Marketing, University of Kassel.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna (BOKU).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Klimek, M., Bingen, J. & Freyer, B. Metropolitan farmers markets in Minneapolis and Vienna: a values-based comparison. Agric Hum Values 35, 83–97 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-017-9800-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-017-9800-1