Abstract

This paper examines the discursive transformation of the historic American public market from that of a municipally regulated institution intended to ensure fair trade and equitable food distribution to “a public place” that emphasizes community identity and sociability. Using a semiotic analysis of interviews with 31 market managers of 30 historic and contemporary American public markets, data from historic documents, and multiple site visits, we compare the social construction of the contemporary public market to farmers markets, supermarkets, and the early twentieth century public market. We analyze the meanings managers create in the contemporary public market to understand the administrative rationalities within which the public market operates. Our analysis reveals evidence of competing imaginaries active in the public market, organized around broad notions of “public benefit,” “community culture” and “institutional viability.” We propose that these tensions are embedded in the public market as an institution historically implicated in regimes of food distribution. In the contemporary context, we conclude, public markets largely substitute the spectacle of community and the image of an historic public life for a legally instated commitment to the just governance of food systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Alkon and McCullen (2011, p. 941) reference farmers markets as “public spaces in which political activity is already present.” They note “We spell farmers markets without the apostrophe to connote that they belong to all of the managers, customers and vendors who play active roles in their creation and functioning… (R)ecasting farmers markets as consisting of farmers, rather than belonging to them, implies that farmers markets are a public resource rather than the property of the most prominent vendors” (endnote 1, p. 951).

See also Morales (2011) who reviews the literature on marketplaces broadly defined, with suggestions for further basic and applied research.

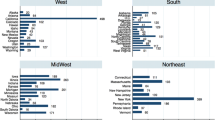

For the purposes of the present study, we defined “historic markets” as those originally listed in the 1918 census report and/or that were established prior to the 1950s, after which migration of food retailing to suburbs and shopping centers was dominant (Cohen 1996). The following are more specific creation date ranges and the relevant number of markets included in this study. Historic markets: 1730–1791 (3), 1802–1888 (10), and 1909–1935 (4). Contemporary markets: 1968–1997 (5) and 2001–2013 (8).

For reference in this article, we labeled the market managers with a two-letter state abbreviation and a number to distinguish multiple markets from the same state (e.g., PA1). The number accords with the original list of 75, rather than with the 30 studied markets. For example, we contacted thirteen markets in Pennsylvania, numbering them PA1 to PA13; however, only five of these markets participated in the study.

A self-identified “pop-up” “farmers market” retained the name of the historic market and located in its original site, but was not the same market.

We distinguished between market ownership (legal), management (agents of the owners), and legal ownership of the building or, in the case of open-air markets, the land that hosted the market. Given this delineation, government authorities and municipalities owned 12 markets, managed 8 of them, but owned 16 market structures and the land on which 6 open-air markets operated. Not-for-profits owned 12 markets, operated 15 of them, and owned 2 of the market structures. Private, for-profit organizations owned 5 of the markets, managed 6 of them, and owned 4 of the market structures. Lastly, vendors owned (including the market structure) and operated one market.

We use this as shorthand for the early twentieth century public market.

See also Baics’ (2012) discussion of this point as an example of an “agglomeration economy.”

We coded the data for the various ways that managers talked about their markets, producing 25 denotative meanings, which formed the basis of the cluster analysis. (We originally coded 47 denotative meanings, but collapsed these to 25 to reduce redundancy). We inferred from the interview context their connotative meanings and institutional concerns, as well as strategies that emanated from these concerns.

We thank one of the reviewers for this observation.

References

Agnew, J. 1979. The threshold of exchange: Speculations on the market. Radical History Review 21: 99–118.

Alkon, A.H., and C.G. McCullen. 2011. Whiteness and farmers markets: Performances, perpetuations… contestations? Antipode 43(2): 937–959.

Allen, D.N. 1985. Business incubators: Assessing their role in enterprise development. Economic Development Commentary Winter: 3–7.

Allen, P. 2010. Realizing justice in local food systems. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 3: 295–308.

Anderson, E. 2004. The cosmopolitan canopy. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 595: 14–31.

Baics, G. 2012. Is access to food a public good? Meat provisioning in early New York City, 1790–1820. Journal of Urban History 20(10): 1–26.

Banerjee, S.B. 2008. Corporate social responsibility: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Critical Sociology 34(1): 51–79.

Barley, S. 1983. Semiotics and the study of occupational and organizational cultures. Administrative Science Quarterly 28: 393–413.

Barnett, C., P. Cloke, N. Clarke, and A. Malpass. 2005. Consuming ethics: Articulating the subjects and spaces of ethical consumption. Antipode 37(1): 23–45.

Beyer, J.M. 1981. Ideologies, values, and decision making in organizations. In Handbook of organizational design, vol. 2, ed. P. Nystrom, and W.H. Starbuck, 166–197. London: Oxford University Press.

Brenner, N., and N. Theodore. 2002. Cities and the geographies of “actually existing neoliberalism”. Antipode 34(3): 349–379.

Brown, A. 2001. Counting farmers markets. Geographical Review 91: 655–674.

Bukenya, J.O., M.L. Mukiibi, J.J. Molnar, and A.T. Siaway. 2007. Consumer purchasing behaviors and attitudes toward shopping at public markets. Journal of Food Distribution Research. 38(2): 12–21.

Burke, P. 1978. Reviving the urban market. “Don’t Fix It Up Too Much.” Nation’s Cities. February: 9–12.

Cannella, B., S. Finkelstein, and D. Hambrick. 2008. Strategic leadership: Theory and research on executives, top management teams, and boards. New York: Oxford University Press.

Casmir, J. 2012. Reading Terminal Unveils New Renovations. NBC10 Philadelphia. http://www.nbcphiladelphia.com/news/local/Reading-Terminal-Market-Unveils-36-Million-Renovations–159485315.html. Accessed 26 Nov 2013.

Chandler, D. 2013. Denotation, connotation, and myth. Semiotics for beginners. http://users.aber.ac.uk/dgc/Documents/S4B/sem06.html. Accessed 5 Jan 2014.

Chatov, R. 1973. The role of ideology in the American corporation. In The corporate dilemma, ed. D. Votaw, and S.P. Sethi, 50–75. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Cohen, L. 1996. From town center to shopping center: The reconfiguration of community marketplaces in postwar America. The American Historical Review 101: 1050–1081.

Coles, B.F., and P. Crang. 2011. Placing alternative consumption: commodity fetishism in Borough Fine Foods Market, London. In Ethical consumption: A critical introduction, ed. T. Lewis, and E. Potter, 87–102. London and New York: Routledge.

Deering, R., and G. Ptucha. 1987. Super marketing: Once-dowdy public markets are taking on new life. Planning 53: 27–29.

DeLind, L.B. 2011. Are local food and the local food movement taking us where we want to go? Or are we hitching our wagons to the wrong stars? Agricultural and Human Values 28: 273–283.

Donofrio, G.A. 2007. Feeding the city. Gastronomica: The Journal of Food and Culture 7: 31–41.

Donofrio, G.A. 2009. The container and the contained: The functional preservation of historic food markets. Ph.D. Dissertation, City and Regional Planning, Cornell University.

Feldman, M.S. 1995. Strategies for interpreting qualitative data. Qualitative Research Methods, Series 33. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Gentry, J.D. 2013. A sustaining heritage: Historic markets, public space, and community revitalization. Master’s Thesis, School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, University of Maryland, College Park.

Goodman, D. 2010. Place and space in alternative food networks: Connecting production and consumption. In Consuming space: Placing consumption in perspective, ed. M.K. Goodman, D. Goodman, and M. Redclift, 189–211. Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

Goodwin, A.E. 1929. Markets: Public and private. Seattle, WA: Montgomery Printing Company.

Goss, J. 1996. Disquiet on the waterfront: Reflections on nostalgia and utopia in the urban archetype of festival marketplaces. Urban Geography 17: 221–247.

Granovetter, M. 1985. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology 91(3): 481–510.

Griffin, M.R., and E.A. Frongillo. 2003. Experiences and perspectives of farmers from upstate New York farmers’ markets. Agriculture and Human Values 20(2): 189–203.

Guthman, J. 2008. Neoliberalism and the making of food politics in California. Geoforum 39: 1171–1183.

Guthman, J., A.W. Morris, and P. Allen. 2006. Squaring farm security and food security in two types of alternative food institutions. Rural Sociology 71(4): 662–684.

Hambrick, D.C., and P.A. Mason. 1984. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review 9(2): 193–206.

Hambright, B. 2011. $7 M makeover takes Central Market into the future. Lancaster Intelligencer Journal. May 6. http://lancasteronline.com/news/m-makeover-takes-central-market-into-the-future/article_36d1aeae-8e2e-5494-8e46-89d85b4f18de.html. Accessed 25 June 2014.

Hinrichs, C. 2000. Embeddedness and local food systems: Notes on two types of direct agricultural market. Journal of Rural Studies 16: 295–303.

King, C.L. 1917. Public markets in the United States. Second report of a Committee of the National Municipal League. Philadelphia, PA: The League.

Kress, G. 2000. Text as the punctuation of semiosis: Pulling at some threads. In Intertextuality and the media: From genre to everyday life, ed. U. Meinhof, and J. Smith, 132–154. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Leitner, H., E.S. Sheppard, K. Sziarto, and A. Maringanti. 2007. Contesting urban futures: Decentering neoliberalism. In Contesting neoliberalism: Urban frontiers, ed. H. Leitner, J. Peck, and E.S. Sheppard, 1–25. New York: The Guilford Press.

Libbin, T.J. 1913. Constructive program for reduction of cost of food distribution in large cities. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 50: 247–251.

Lum, M. 2007. Public markets as sites for immigrant entrepreneurship in East Hollywood. Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Masters of Arts in Urban Planning, University of California, Los Angeles.

Manning, P. K. 1987. Semiotics and fieldwork. Qualitative Research Methods, Series 7. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Mayo, J.M. 1991. The American public market. Journal of Architectural Education 45: 41–57.

Morales, A. 2009. Public markets as community development tools. Journal of Planning Education and Research 28: 426–440.

Morales, A. 2011. Marketplaces: Prospects for social, economic, and political development. Journal of Planning Literature. 26(1): 3–17.

Moran, B. 2013. Defining ‘Farmers Market’—The devil is in the details. Farmers Market Coalition, http://farmersmarketcoalition.org/defining-devil-in-the-details/. Accessed 15 May 2014.

Murphy and Dittenhafer Architects. 2005. The Food Trust, Wagman Urban Group, and Mary Means and Associates. Lancaster Central Market Master Plan. http://www.friendsofcentralmarket.org/pdfs/lancastercentralmarket.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2014.

Nadal, L. 2000. Discourses of urban public space, USA 1960–1995: A historical critique. Ph.D. Dissertation, Columbia University.

Novak, W.J. 1993. Public economy and the well-ordered market: Law and economic regulation in 19th-century America. Law and Social Inquiry 18: 1–32.

Novak, W.J. 1996. The people’s welfare: Law and regulation in nineteenth-century America. Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press.

Project for Public Spaces and Partners for Livable Communities. 2003a. Public markets: Phase I report: An overview of existing programs and assessment of opportunities as a vehicle for social integration and upward mobility. New York: Project for Public Spaces, Inc. http://www.pps.org/pdf/Ford_Report.pdf. Accessed 26 Nov 2013.

Project for Public Spaces. 2003b. Public markets and community-based food systems making them work in lower-income neighborhoods. New York: Project for Public Spaces, Inc. (on behalf of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation). http://www.pps.org/pdf/kellogg_report.pdf. Accessed 26 Nov 2013.

Project for Public Spaces. n.d.(a) Endless Bounty: The transformative benefits of public markets. http://www.pps.org/reference/the-benefits-of-public-markets/. Accessed 27 Dec 2013.

Project for Public Spaces. n.d.(b) What is placemaking? http://www.pps.org/reference/what_is_placemaking/. Accessed 24 Jan 2014.

Rogers, S.L. 1919. Municipal markets in cities having a population of over 30,000 1918. Department of Commerce. Bureau of the Census. Washington, DC.: Government Printing Office.

Schein, E. 2010. Organizational culture and leadership, 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

Slater, D. 1993. Going shopping: Markets, crowds, and consumption. In Cultural reproduction, ed. C. Jenks, 188–209. London: Routledge.

Sommer, R., J. Herrick, and T.R. Sommer. 1981. The behavioral ecology of supermarkets and farmers’ markets. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 1: 13–19.

Spitzer, T.M. 2013. Does a public market make sense for Fresno? Fresno public market feasibility assessment, Market Ventures, Inc. http://www.fresno.gov/NR/rdonlyres/046501F5-2A7C-4530-AE39-FA52BCF9F32F/26569/Fresnopresentation201301v3small.pdf. Accessed 24 August 2013.

Spitzer, T.M., and H. Baum. 1995. Public markets and community revitalization. Washington, D.C.: ULI-the Urban Land Institute and Project for Public Spaces Inc.

Steel, C. 2013. Hungry city: How food shapes our lives. London: Vintage Books.

Tangires, H. 1997. Feeding the cities: Public markets and municipal reform in the progressive era. Prologue. Spring: 17–26.

Tangires, H. 2003. Public markets and civic culture in nineteenth-century America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Thompson, C.J., and G. Coskuner-Balli. 2007. Enchanting ethical consumerism. Journal of Consumer Culture. 7(3): 275–303.

Trauger, A., C. Sachs, M. Barbercheck, K. Brasier, and N.E. Kiernan. 2010. Our market is our community: Women farmers and civic agriculture in Pennsylvania USA. Agriculture and Human Values 27(1): 43–55.

USDA Farmers Market Directory. n.d. http://search.ams.usda.gov/farmersmarkets/. Accessed 24 July 2014.

Weber, K., K.L. Heinze, and M. DeSoucey. 2008. Forage for thought: Mobilizing codes in the movement for grass-fed meat and dairy products. Administrative Science Quarterly 53: 529–567.

Zade, J.C. 2009. Public market development strategy: Making the improbable possible. Master’s Thesis in City Planning and Master of Science in Real Estate Development, MIT.

Zukin, S. 1990. Socio-spatial prototypes of a new organization of consumption: The role of real cultural capital. Sociology 24(1): 37–56.

Zukin, S. 2010. Naked city: The death and life of authentic urban places. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Harvey James and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier drafts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kurland, N.B., Aleci, L.S. From civic institution to community place: the meaning of the public market in modern America. Agric Hum Values 32, 505–521 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-014-9579-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-014-9579-2