Abstract

Asian Indians comprise the largest group of skilled workers entering the United States on temporary work visas (H-1B). There are few studies that examine the constraints placed on H-1B visa holders and their families on H-4 dependent visas, and the associated stressors. In this exploratory study, we examined self-reported depression, anxiety, stress, well-being, and marital satisfaction among married Asian Indians on H-1B and H-4 visas in the United States. Participants reported moderate levels of stress and depression and mild levels of anxiety. Using multiple regression, well-being emerged as the only significant factor to explain marital satisfaction among both H-1B and H-4 visa holders. Implications for mental health, employment, and career counselors working with this group are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The United States immigration policy allows United States (US) employers to hire skilled workers on a temporary basis from other countries under the H-1B visa, and Congress restricts the number who can enter this visa category each year. In 2021, the number of H-1B visas was limited to 65,000 for applicants with a bachelor’s degree, plus 20,000 for applicants who graduated with a master’s or doctoral degree from a US institution (American Immigration Council, 2021). Many college-educated Asian Indians arrive in the US on H-1B temporary work visas, with their spouses and children on H-4 visas. In 2018, Asian Indians comprised approximately three-fourths of all the petitions for H-1B visas, 309,986 or 73.9%, the highest number of petitioners of all countries according to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services ([USCIS], 2018).

Employers are permitted to employ H-1B workers by making a case that there are not enough qualified workers to fill these jobs, while also making the case that employing them will not disadvantage US workers (American Immigration Council, 2021). Most H-1B petitions are from employers in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) fields (American Immigration Council, 2021). These workers are employed in positions that earn high wages, with a reported median income of $120,000 for foreign-born Asian Indians in 2019 (Budiman, 2021), but they are only allocated a limited time on the H-1B visa. The initial duration for H-1B visa holders to live and work in the US is 3 years, and this can be extended to 6 years (American Immigration Council, 2021).

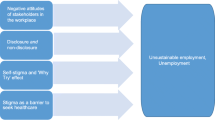

Most Asian Indian on H-1B visas aspire to obtain permanent residence by way of a green card and to eventually become US citizens. However, they face many barriers and challenges that affect their mental health adversely. Work visas are dependent on the employer, and these workers can be terminated at will by their employer. If they become unemployed, they and their H-4 dependents lose their visa status and have a limited time to either find another employer willing to hire them under H-1B or leave the country. Furthermore, converting to permanent residence requires the support of employers. An additional stressor is that H-1B visa holders are permitted to have their spouses or children under the age of 21 accompany them or join them on H-4 visas (American Immigration Council, 2018). H-4 holders are referred to as H-4 dependents as their status is dependent on their H-1B spouse or parent remaining in that status. While H-4 visa holders can enroll in education, they are not permitted to work or earn their own living, unless they apply for and are approved for temporary work status (also known as Employment Authorization Document [EAD]). The EAD can often take years to be approved (US Citizenship and Immigration Services [USCIS], 2021), resulting in qualified spouses being unable to work.

Literature Review

Psychological Distress and Well-being of Asian Indian Immigrants in the US

As the Asian Indian population is rapidly rising in the United States, counselors need to understand some of the mental health needs and stressors faced by them. Despite being from the same country, Asian Indians are not a homogenous group due to the high level of diversity in India by region, religion, diet, cultural norms, languages, socioeconomic status (SES), and educational level (Gawlick, 1997; Pillalamarri, 2019). Culture and immigration are issues that may impact the health and overall quality of life of this population (Chandra et al., 2016; Panjwani et al., 2021).

Acculturation stress has been linked to depression in Asian Indian college students (Ma, 2021) and in older Asian Indian immigrants (Diwan et al., 2004). Acculturating to life in a new country while maintaining one’s cultural identity could be both a risk factor and a coping resource, impacting the psychological well-being of immigrants (Alegría et al., 2017). In addition to the existing factors that may contribute to the lack of psychological well-being among Asian Indian communities, women may experience additional challenges related to sexual or intimate partner violence (Tummala-Narra et al., 2019). Immigration and acculturation may shape their conceptualization of such violence, and they may experience isolation or barriers to seeking help due to discrimination and a lack of equality in their relationships (Tummala-Narra et al., 2019).

Radhika (2016), in her book on visa wives, illuminating the stories of Indian women on H-4 visas, discussed the loneliness these women experience. They reported longing for some familiar Indian companionship, waiting for their husbands to return home, a lack of entertainment options, lack of visibility of human neighbors, and missing bustling crowded neighborhoods that they were used to in India. They did not discuss being depressed but suggest that mental health stigma may contribute to under-reported levels of depression among Asian Indians.

Wong and Miles (2014) reported that only 3% of their study of Asian Indians reported the presence of depression, and women were more likely to contribute to that figure. Siddiqui et al. (2020) reported that 11% of Asian Indians in their study reported psychological distress comprised of depression and anxiety. Panjwani et al. (2021) found that, among other quality-of-life factors, psychological well-being was comparatively lower among non-immigrant visa holders such as H-1B and H-4 Asian Indians than naturalized citizens or permanent residents. In addition to the stressors related to acculturating to a new country with new cultural norms and likely limited family support, stressors related to being on temporary visas are experienced by Asian Indians on H-1B and H-4 visas. In particular, the green card backlog seems to exacerbate fear and frustration and result in heightened stress and a range of negative psychological health conditions (Vijayakumar & Cunningham, 2019). The fear of a loss of visa status is a source of stress and could compromise the mental health and wellness of H-1B and H-4 visa holders. Furthermore, the temporary nature of H-1B and H-4 visas creates a loss of personal agency as workers and their families are dependent on employers to remain in status, and their ability to obtain a green card within the 6-year period requires support and documentation from their employer to do so.

For those Asian Indian residents on H-1B or H-4 visas who have children, there is the added fear of their children “aging-out” and not being able to remain in the US legally once they reach the age of 21 (Shoichet, 2021). The advocacy group, Improve The Dream (Improve The Dream, n.d.), estimates that there are over 200,000 children who were brought to the US legally by their parents on H-4 visas who face deportation upon turning 21. Many of the issues and sources of stress stem from an outdated system of immigration laws, with long waits for green cards to be processed, especially for H-1B visa holders from India (Shoichet, 2021). These concerns are highlighted in a mixed-methods research study with 1042 Indian immigrants in the US (Vijayakumar & Cunningham, 2019) wherein a range of challenges contributing negatively to work, family life, and overall stress and health are described, including wage stagnation, job insecurity, career roadblocks, financial insecurities, travel issues, issues pertaining to family separation, kids aging out, and H-4 Employment Authorization.

Married Asian Indians on Work Visas in the US

India is considered one of the most collectivistic countries in the world (Buss et al., 1990; Hofstede, 1980), and Indians tend to endorse traditional gender roles (Suppal et al., 1996). As a result of the collectivistic culture, individuals are socialized to consider the well-being of the group over their own needs (Le & Impett, 2013). These cultural norms can play a key role in marital relationships, shaping the ways that spouses behave toward each other, perceive the quality of their relationship, and divide up family responsibilities (Perry-Jenkins & Crouter, 1990).

A recent report by the Institute for Family Studies (IFS; Wang, 2021) compared 30 working-age immigrant groups in the US and reported that Asian Indian Americans ranked number one in family stability. According to this report, almost all (first-generation) Indian immigrants with children were found to be stably married (94%), i.e., married once and remaining in the marriage. Factors such as higher education and income levels of Indian immigrants compared to any other immigrant groups in the US may contribute to family stability (Wang, 2021). However, even while researchers controlled for education and income, first-generation Indian immigrants with children in the US were found to report the highest family stability. This, according to the study, is a result of Indian immigrants embracing a culture of familism where there is a family-first mindset with the value being placed on intact families with two married parents and a reluctance to consider divorce even when marriages have problems. Most marriages are arranged by the parents or families of the couple.

In an online study conducted with Asian Indians, both non-citizens and citizens in the US, the researchers reported a very high rate of marriage and endogamy (i.e., the custom of marrying within one’s community) among first-generation Indian immigrants (Badrinathan et al., 2021). In the 2020 Indian American Attitudes Survey, over 77% of the 728 participants reported that their spouses were of Indian origin, born in India. It is highly likely that many Indian immigrants may enter the US with H-4 dependent status. However, as discussed above, H-4 dependent visa holders cannot legally work in the US and are forcibly unemployed. About 90% of the H-4 holders have a college degree and might have left highly-paying jobs in order to join their spouses in the US (Bier, 2020). Despite the backlogged system for permanent residency, many talented spouses of H-1B holders continue to come and stay in the US due to the possibility of H-4 employment authorization, which can be a lengthy process. This restrictive policy may cause economic distress due to unemployment, but it also has long-term consequences due to the extended employment gap in resumes (Bier, 2020). With the range of stressors Asian Indians on H-1B or H-4 visas experience, we were interested in exploring marital satisfaction, well-being, depression, anxiety, and stress reported by married Asian Indians.

Purpose of the Study and Research Questions

There has been limited empirical work focusing on the mental health, well-being, and marital satisfaction of Asian Indians in the US in general, and no studies that we are aware of that explored these issues with married Asian Indians in the US on H-1B and H-4 visas. Thus, the purpose of this exploratory study was to understand the levels of self-reported depression, anxiety, stress, well-being, and marital satisfaction among married Asian Indians on H-1B and H-4 visas in the US and to inform the work of mental health, employment, and career counselors assisting this group. The following research questions guided our work:

-

1.

What is the self-reported depression, anxiety, and stress of married Asian Indians on H-1B and H-4 visas in the US as measured by the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21, Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995)?

-

2.

What is the self-reported well-being of married Asian Indians on H-1B and H-4 visas in the US as measured by the PERMA-Profiler (Butler & Kern, 2016)?

-

3.

What is the self-reported marital satisfaction of married Asian Indians on H-1B and H-4 visas in the US as measured by the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale [KMS] (Schumm et al., 1983)?

-

4.

To what extent do depression, anxiety, stress, and well-being explain the marital satisfaction of H-1B and H-4 visa holding Asian Indians in the US?

Methods

Participants Characteristics

There were 213 participants in the study, of which 62% (132) were males and 38% (81) were females. As further illustrated in Table 1, the majority of respondents (56.3%) were in the age range of 33–39, followed by 24.9% in the 26–32 age range. Only 0.5% were in the 54–60 age range. The mean age of the participants was 29.7 years.

Regarding visa status, 69% (n = 147) of the respondents reported having H-1B visas, while 31% (n = 66) were on H-4 visa status. Among H-4 participants, 74.24% (n = 49) were unemployed due to either ineligibility to work or unable to find employment in the US, leaving only 25.75% (n = 17) of H-4 participants being employed at the time of the study. The majority of participants in general reported having a master’s degree (51.6%), followed by 42.7% with a bachelor’s degree.

Regarding annual income, the majority of participants (n = 86; 40.4%) indicated their annual income was $100,000–$200,000, while only 0.9% (n = 2) of the participants reported an annual income of less than $20,000. There were over 4% (n = 9) of participants who reported an annual income of over $200,000. Of particular interest, 19.7% chose the “not applicable option” for their annual income, which presumably encompasses the majority of participants on H-4. The other 34.8% (n = 74) of participants reported an annual income ranging from $20,000–$100,000. Fifty-four percent (n = 117) of the respondents reported employment in the field of technology. Other reported fields of employment included advocacy, banking, daycare, dentistry, education, finance, and health care.

The mean years of marriage among the participants were 8.28 with a standard deviation of 5.143. The majority of them 51.2% (107) reported 0–7 years of marriage, while 0.5% (1) indicated that they were married for 24–31 or 32 + years. Approximately a third of participants reported having children—35.7% and 34.7% of the participants reported having one and two children, respectively, while 28.6% had no children. The mean years of stay in the United States (US) among participants were 7.55 years with a standard deviation of 3.33. On average, participants (102 or 47.9%) reported living in the US for 5–8 years. There were also a few (n = 2) who reported living in the US for 17–20 years.

Instruments

The three instruments that were used for this study are discussed below. Using a demographic questionnaire, we gathered information pertaining to the participants such as age, education levels, marital status, years of marriage, years of stay in the US, whether they were permanent residents or not, their visa status, etc.

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21)

DASS-21 (Lovibond and Lovibond, 1995) is a self-report instrument that is used to measure levels of psychological distress including depression, anxiety, and stress. Stress is characterized by nervous tension, being overreactive, impatient, difficulty relaxing, and irritability. Anxiety involves autonomic aroUSl, skeletal muscle affects, and situational and subjective experience of anxious affect. Depression constitutes hopelessness, dysphoria, devaluation of life, self-depression, lack of interest, anhedonia, and inertia (Lovibond and Lovibond, 1995). There are 7 items per scale. Scores in each sub-scale are multiplied by 2 in order to make it comparable to the corresponding original DASS-42 score. DASS-21 is a dimensional concept, and the scores are divided into normal, mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe into each of the 3 scales assessed. The alpha coefficient for DASS-21 is 0.966. In particular, Cronbach’s Alpha for depression, anxiety, and stress was 0.922, 0.890, and 0.912 respectively.

PERMA-Profiler

The PERMA-Profiler (Butler & Kern, 2016) was developed to measure Seligman’s (2011) PERMA elements of well-being: (P)ositive emotions, (E)ngagement, (R)elationships, (M)eaning, and (A)ccomplishment. The PERMA-Profiler consists of 23 items where 15 items are used to measure the five PERMA elements and the additional 8 items measure negative emotions, physical health, and loneliness. Each item is rated on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 10 (always), or 0 (not at all) to 10 (completely). Butler and Kern (2016) indicate well-being scores below 5 to be “languishing” and 9 and above to be “very high functioning.” Any score between 6.5 and 7.9 is considered normal functioning. Likewise, scores between 5 and 6.4 are considered to be sub-optimal functioning contrary to high functioning which is between 8 and 8.9. The reliability, test–retest stability, and construct validity of its subscales are high (Butler & Kern, 2016). Furthermore, in the present study, the alpha coefficients overall for PERMA dimensions of well-being were strong, i.e., positive emotions (0.80), engagement (0.66), relationships (0.84), meaning (0.88), and accomplishments (0.74). The alpha coefficient for overall PERMA well-being in the current study was 0.93.

Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale (KMS)

KMS is used to measure Marital Satisfaction among married couples using a three-item self-reported 7-point scale that ranges from extremely dissatisfied (1) to extremely satisfied (1). The original version of the measure developed by Schumm et al. (1983) includes items aimed at assessing a person’s satisfaction with their spouse, their marriage, and their marital relationship. There are no subscales in this assessment. An example item includes “how satisfied are you with your marriage?” The KMS scale was found to be the strongest measure overall with an average Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.95 across studies in a meta-analysis of 398 articles evaluating the reliability of seven different relationship satisfaction measures (Graham et al., 2011). In the current study, the alpha coefficient for the KMS was 0.98. The KMS scale also is known for its sensitivity to change (Jansen et al., 2021; Kwena et al., 2022) and brevity.

Data Collection Procedures

Researchers obtained University Institutional Review Board approval prior to data collection. A convenient snowball sampling method was used for this study with the aim to include married Asian Indian individuals on H-1B and H-4 visas across different states in the US. An electronic form of the assessment packet (i.e., demographic and background form, three standardized assessments) was created using Qualtrics. It was estimated that the survey would take approximately 10–15 min to complete. The survey link was emailed to Indian Student Associations and Organizations in universities and communities in the US as well as to counseling listservs (e.g., CESNET, TACES, ACA interest network) by researchers. Every request was sent three times. Prospective participants were requested to send the survey link to anyone they believed would meet the eligibility criteria. The inclusion criteria mentioned in the recruitment email/posts mentioned that individuals over the age of 18, married, identified as Asian Indian (from India), on H-1B or H-4 visa, and who resided in the US for a minimum of a year could participate in the study. Through the G power analysis technique, we aimed at recruiting a target of 190 participants for the study. A total of 339 participants attempted to take the survey between May 22, 2020, and July 20, 2021, out of which 213 participants with complete or almost complete data sets were included in the final sample.

Data Analysis Procedure

SPSS was utilized for analyzing the data. Data were cleaned and screened for potential problems (i.e., missing data, normality, linearity, homoscedasticity, and multicollinearity). During the initial screening of the data, respondents who dropped out of the survey and stopped answering questions were sorted and removed. If a participant failed to answer the entire items of the three scales, their data was considered incomplete and removed. Furthermore, if there were 20–30% of missing data where respondents had missed only a few items from the scales, the series mean imputation technique (Eekhout et al., 2014) was used wherein the missing value was replaced with a series mean of the indicator. The linearity, normality, homoscedasticity, and the absence of multicollinearity were also supported by the assessments of probability plots and VIF values. Prior to analysis, we assessed the multicollinearity of the study variables by reviewing correlations. We found significant correlations among several variables, although none of concern above 0.80 (Field, 2018). We reviewed the data for assumptions of multivariate analysis. The Durbin-Watson test was in the expected range to establish independence, visual inspection of plots confirms linearity, and skewness and kurtosis fell within an acceptable range (+ / − 1.0; Field, 2018). Given the exploratory nature of the study, we emphasized descriptive statistics of study variables for research questions one to three, including mean differences in marital satisfaction, well-being, and psychological distress between H-1B ad H-4 groups. To examine the effects of stress, anxiety, depression, and well-being, on marital satisfaction (research question four) among H-1B and H-4 visa holders, we utilized multiple regression analysis.

Results

The significant findings of the study are presented below. First, within the sample as a whole, stress was reported to be the highest (M = 15.53, SD = 11.831) among the three sub-scales of the DASS-21 scale measuring psychological distress, indicating moderate to high levels of stress. Following stress was depression (M = 14.56, SD = 12.296), categorized as a moderate level of depression. Anxiety (M = 11.22, SD = 10.543) was categorized as a mild level of anxiety (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 1, participants on H-4 visas reported slightly higher stress (M = 17.06, SD = 12.35), depression (M = 16.12, SD = 14.094), as well as anxiety (M = 11.94, SD = 10.618), compared to individuals on H-1B visa (i.e., stress—M = 14.84, SD = 11.567; depression—M = 13.86, SD = 11.380; and anxiety—M = 10.90, SD = 10.529). There were also differences in psychological distress levels among H-4 participants based on their employment status. For example, H-4 visa holders who were employed (depression: M = 11.06, SD = 11.83; anxiety: M = 9.88, SD = 9.20; stress: M = 14.59, SD = 10.97) versus unemployed (depression: M = 17.88, SD = 14.49; anxiety: M = 12.65, SD = 11.06; stress: M = 17.92, SD = 12.78).

Second, in general, the H-1B and H-4 participants combined reported experiencing sub-optimal functioning (M = 5.02; SD = 1.713). Upon looking closely into the PERMA factors, positive emotions (M = 5.31, SD = 2.154), relationships (M = 5.31, SD = 2.154), and engagement (M = 5.05, SD = 1.863) were in the sub-optimal functioning range, but other factors such as meaning (M = 4.94, SD = 2.093) and accomplishment (M = 4.83, SD = 1.798) were indicating a languishing state of functioning. In further examination of PERMA well-being differences among H-1B and H-4 groups, as seen in Fig. 2, it was found that individuals on H-4 visas scored consistently lower in positive emotions (M = 4.77, SD = 2.208), engagement (M = 4.67, SD = 2.082), meaning (M = 5.32, SD = 2.240), accomplishment (M = 4.53, SD = 1.914), health (M = 5.35, SD = 2.140), happiness (M = 5.25, SD = 2.472), and overall well-being (M = 4.82, SD = 1.873), compared to individuals on an H-1B visa [i.e., positive emotions (M = 4.93, SD = 1.838), engagement (M = 5.22, SD = 1.736), meaning (M = 5.05, SD = 1.999), accomplishment (M = 4.97, SD = 1.734), health (M = 5.46, SD = 1.966), happiness (M = 5.35, SD = 2.046), and overall well-being (M = 5.11, SD = 1.634)]. Also, the individuals on H-4 visas reported higher negative emotions (M = 4.86, SD = 1.840) and loneliness (M = 4.27, SD = 2.856) compared to the H-1B group, i.e., (NE—M = 4.23, SD = 1.919; Lon—M = 3.69, SD = 2.770). Among H-4 group, employed individuals higher well-being (M = 5.56; SD = 1.80) than those who were unemployed (M = 4.56; SD = 1.84).

Third, with regard to marital satisfaction scores among the sample as a whole, participants in the study indicated being between somewhat satisfied and very satisfied (M = 16.77, SD = 4.944). While comparing the means between H-1B and H-4 groups, it was found that the H-1B group indicated slightly lower marital satisfaction (M = 16.76, SD = 4.758) than the H-4 group (M = 16.77, SD = 5.375). Within the H-4 group, there were mean differences in marital satisfaction scores between those who were employed (M = 18.24; SD = 4.39) than those who were unemployed (M = 16.27; SD = 5.62).

Fourth, to determine the extent to which stress, anxiety, well-being, and depression explain marital satisfaction, multiple regression analysis was carried out among H-1B and H-4 visa holders separately (see Table 2). With regard to the H-1B group, the findings indicate that the prediction model with the four predictors—PERMA, anxiety, depression, and stress—was statistically significant (F (4, 142) = 4.22, p = 0.003) and accounted for approximately 11% of the variance of marital satisfaction (R2 = 0.11 and adjusted R2 = 0.08). The co-efficient table presents PERMA well-being as the only significant predictor of marital satisfaction (t = 3.49, p < 0.001). Similar to the findings among the H-1B group, PERMA well-being was the only significant predictor of marital satisfaction (t = 2.14, p = 0.04) among the H-4 group (F (4, 61) = 3.81, p = 0.008), accounting for approximately 20% of the variance of marital satisfaction (R2 = 0.20 and adjusted R2 = 0.15).

Discussion

The purpose of this exploratory study was to understand the levels of self-reported depression, anxiety, stress, well-being, and marital satisfaction among married Asian Indians on H-1B and H-4 visas in the US. It is pivotal to acknowledge that the self-reported scores on the study variables may to a greater extent be influenced by social desirability, particularly stemming from a culture that emphasizes saving face (Radhika, 2016). This may have resulted in participants to some extent feeling a need to under-report psychological distress levels and over-estimate well-being and marital satisfaction. With this consideration, we review the main findings of the study.

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

Participants as a whole reported moderate levels of stress and depression and mild levels of anxiety. Contrary to this finding, in a study on Indians during COVID-19, Rehman et al. (2021) reported mild levels of stress and depression and moderate levels of anxiety. Regardless, psychological distress was present. Compared to individuals on H-1B, the H-4 visa holders reported slightly higher levels of stress, depression, and anxiety, although not statistically significant. However, future researchers may find greater differences using a different instrument to measure these variables.

Higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression among H-4 visa holders may be attributed to aspects such as mental health and psychological impact of unemployment (Frijters et al., 2004), perceived change in self-identity from being working to being an unwaged spouse (Day, 2003), a sense of lack of control over one’s life (Ross, 1991), and lack of self-esteem (deTurck & Miller, 1986). Other factors that may have contributed include dependency or lack of financial freedom and unequal distribution of power among the couple (Cui et al., 2023), and acculturation challenges without organizational support (Martens & Grant, 2008). Mahendra and Agarwal (2016) found similar findings where individuals on H-4 dependent visas demonstrated higher levels of depression and anxiety. Although there were some participants on H-4 visa with work permits and employment in this study, there still seems to be a higher prevalence of stress, depression, and anxiety, which may possibly stem from participants’ difficulties to reintegrate n re-integrating back into the workforce, transition and acculturation challenges (Yellig, 2011).

Well-being

Participants reported below-average well-being in all the areas of PERMA well-being, including overall well-being. Prior research provides some possible reasons for lower levels of well-being. H-1B workers may struggle with needing to adjust to both their personal and professional lives in a new country, and this may impact their life and well-being (Sarmistha, 2019). It is plausible that a lack of adequate social support and supportive workplace policies hinders productivity and impacts the mental well-being of this population (Chaudhuri et al., 2020).

Given that majority of the study participants on H-4 visas were unable to work or were awaiting their work permits during the study, they may have reported lower PERMA factors, including positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment, indicative of the lower overall quality of life and well-being, consistent with previous studies among H-4 dependent visa holders (e.g., Bajpayee, 2021; Mahendra & Agarwal, 2016). Particularly, higher feelings of loneliness and negative emotions among H-4 dependents reported by participants are consistent with what we have known about this population from the literature (e.g., Radhika, 2016).

Marital Satisfaction

The scores reported by participants on marital satisfaction place them between somewhat satisfied and very satisfied in their satisfaction with their spouse, their marriage, and their marital relationship. This may be due to factors such as income, education level, number of children, single spouse, and overall family stability, as indicated in the previous studies (Badrinathan et al., 2021; Wang, 2021). Interestingly, individuals on H-1B reported slightly lower levels of marital satisfaction than those on H-4. This may be speculated that a myriad of stressors (e.g., risk related to job status, need for higher work performance, financial concerns, balancing work and family demands) associated with work may impact their marital satisfaction to some extent. In particular, the undue pressure on the shoulders of H-1B working members of the family to keep their dependent spouse happy and comfortable away from their home country may be weighing on their relational satisfaction. Further exploration of specific factors is warranted. We also believe that it warrants future researchers’ initiatives to investigate if the quality of marital relationships serves as a protective buffer and a coping strategy in dealing with challenges experienced by H-4 dependents as little is currently known about the factors contributing toward their overall resiliency.

PERMA Well-being as a Predictor of Marital Satisfaction

As expected, marital satisfaction was strongly positively associated with well-being and negatively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. It is important to note that PERMA well-being emerged as the only significant factor to explain marital satisfaction among both H-1B and H-4 groups in our study. This finding suggests that efforts to foster an individual’s well-being may significantly result in enhancing marital satisfaction among Asian Indian immigrant families. In general, in the literature, we find evidence to support the positive relationship between individual well-being and relationship satisfaction (Moore & Diener, 2019). However, as little is so far known about the Asian Indian immigrant populations’ well-being in relation to their marital satisfaction, further exploration in this area is warranted.

Implications for Mental Health Counselors

Prior studies (Abdullah & Brown, 2011; Rajkumar, 1991) have noted the stigma associated with mental health among Asian Indians, leading to an unwillingness to seek counseling. Counselors would have to understand this resistance to mental health treatment and diagnoses and work diligently to meet Asian Indian clients where they are related to their beliefs about mental health. Approaching interventions from an employment or career perspective may help engage Asian Indian clients in the process. For example, Clarke et al. (2018) utilized a series of action-oriented hope interventions with success in a group of immigrant professionals in Canada who were educated overseas and working through the process of obtaining licensure to practice in their fields. Kim et al. (2002) noted that individuals steeped in Asian cultural values tended to view counselors as authority figures with credibility and valued expertise, thus offering the potential for positive therapeutic outcomes when they sought counseling for personal and health-related problems. It is essential for counselors working with Asian Indians to understand acculturation issues (Miville & Constantine, 2007), especially as H-1B visa holders are brought into the US from their home countries to address workforce shortages.

We offer the following suggestions for employment, career, and mental health counselors working with Asian Indians on H-1B and H-4 visas. First, we recommend that counselors understand the complexities of H-1B and H-4 visas and the restrictive conditions that they impose on married Asian Indians who are on these visas. Restrictions include the time-bound nature of such visas (issued for a period of 3 years, which can be extended to a second term of 3 years, provided the H-1B visa holders are supported by their workplaces to extend to a second term) and the inability of spouses of H-4 visas to work. H-1B visa holders who are unable to convert their visas to permanent resident status would have to leave the country, and this is related to a sense of impermanence and a loss of personal agency in how their lives may unfold. The visa issues mentioned above can contribute to lower levels of well-being and greater levels of depression, anxiety, and stress.

Second, we suggest that counselors pay close attention to the psychological distress and well-being of Asian Indians on H-4 visas as many of these individuals are financially dependent on their spouses who are on H-1B visas because they are prohibited from working. Many H-4 visa holders are well-educated and would have left jobs in India to accompany their spouses. They may become frustrated or disheartened when they are unable to work outside of the home themselves. Qualitative research studies could help uncover these nuances.

Third, we recommend that counselors understand the pressures faced by Asian Indians on work visas related to the H-4 visa statuses of their children and discuss with clients the very real fears of their children “aging-out” and needing to self-deport or face becoming illegal immigrants at age 21, despite having lived legally in the US until they attained majority. Linking Asian Indian parents to national and state advocacy initiatives such as Improve the Dream (n.d.) and OPAWL – Building AAPI Feminist Leadership (n.d.) could be beneficial.

Fourth, we recommend that counselors pay attention to how visa status may be related to well-being and psychological distress, and explore how marriage may serve as a risk factor or a protective factor against psychological distress. In our study, marital satisfaction tended to range between somewhat satisfied and very satisfied, and there were negative, significant correlations between marital satisfaction and depression, anxiety, negative emotion, and loneliness, indicating that it served as a protective factor. Clarke et al. (2018) noted in their study that consistent with prior research, relationships, support, and inner strength were facilitative factors among immigrant professionals in Canada who successfully navigated career transitions and maintained hope (p. 163). Finally, we recommend that counselors be willing to explore issues of underemployment, unfair treatment, and racism or discrimination that H-1B visa holders may experience in workplaces. H-1B visa holders may feel particularly vulnerable and unable to speak up about these matters for fear that their work sponsor may terminate their work visas.

There is a need to offer supportive programs for dependent spouses of H-1B visa holders with a focus to enhance their overall well-being. Support groups and community-based orientation programs may be helpful in the acculturation process if offered during the initial months after immigrating to the US. In general, this study emphasizes the need for mental health counselors to possess a relevant and deeper understanding of the unique immigration struggles experienced by the H-1B and H-4 populations. In particular, gaining knowledge and awareness of the strengths, needs, and challenges of Asian Indian immigrant communities in US workplaces and societies may be beneficial for counselors to serve them with greater multicultural competency and responsiveness.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

We encourage future researchers to address the limitations of the current study in their work. Limitations include the use of self-report measures, lack of measuring and contrasting data from both the members of the married relationship, and lack of diverse recruitment strategies as most participants on H-4 were reached through social media and community groups. Combining quantitative findings with the qualitative experiences of the challenges associated with immigration status on mental health and well-being may aid in a fuller understanding of Asian Indian H-1B visa holders and their H-4 dependents in the US. Future researchers may shed further light on the interrelated, complex nature and dynamics of the constructs by using advanced statistical analyses. Additionally, because H-1B visas are granted initially for 3 years and subsequently for another 3 years, utilizing a longitudinal approach measuring psychological distress, well-being, and marital satisfaction over different time periods in the 6-year time frame may yield interesting findings. Finally, since many H-1B and H-4 visa holders are motivated to enter the US to secure a better future for themselves and their children, future researchers may want to examine how factors such as hope, optimism, and resiliency contribute to well-being.

Conclusion

The current research sheds light on married Asian Indians on skilled work visas in the US, focusing on their mental health, including depression, anxiety, and stress, and on their well-being. Mental health, career, and employment counselors could benefit from a better understanding of the stressors and challenges faced by this group of skilled workers and their families. The findings of this study could also be of interest to legislators, organizational leaders, and advocacy groups.

References

Abdullah, T., & Brown, T. L. (2011). Mental illness stigma and ethnocultural beliefs, values, and norms: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 934–948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.003

Alegría, M., Álvarez, K., & DiMarzio, K. (2017). Immigration and mental health. Current Epidemiology Reports, 4(2), 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-017-0111-2

American Immigration Council. (2018). The H-4 visa classification: Attracting and maintaining global talent. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/h-4-visa-classification. Accessed 8 May 2023

American Immigration Council. (2021). The H-1B visa program: A primer on the program and its impact on jobs, wages, and the economy. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/H-1B-visa-program-fact-sheet. Accessed 8 May 2023

Badrinathan, S., Kapur, D., Kay, Jonathan, & Vaishnav, M. (2021). Social realities of Indian Americans: Results from the 2020 Indian American Attitudes Survey. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/06/09/social-realities-of-indian-americans-results-from-2020-indian-american-attitudes-survey-pub-84667. Accessed 8 May 2023

Bajpayee, S. (2021). Perceived social status and gender role beliefs impact on self-efficacy and quality of life of women of color, dependent visa holders in the United States (Doctoral dissertation, The University of North Dakota). https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/perceived-social-status-gender-role-beliefs/docview/2546607312/se-2. Accessed 8 May 2023

Bier, D. J. (2020). The facts about H-4 visas for spouses of H-1B workers. https://www.cato.org/blog/facts-about-h-4-visas-spouses-h-1b-workers. Accessed 8 May 2023

Budiman, A. (2021). Indians in the US. Fact sheet. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/fact-sheet/Asianamericans-indians-in-the-u-s/. Accessed 8 May 2023

Buss D. M., Abbott M., Angleitner A., Asherian A., Biaggio A., Blanco-Villasenor A., Bruchon-Schweitzer, M., Ch’U, H., Czapinski, J., Deraad, B., Ekehammar, B., El Lohamny, N., Fioravanti, M., Georgas, J., Gjerde, P., Guttman, R., Hazan, F., Iwawaki, S., Janakiramaiah, N., … & Yang, K. (1990). International preferences in selecting mates: A study of 37 cultures.Journal of cross-cultural psychology, 21, 5–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022190211001

Butler, J., & Kern, M. L. (2016). The PERMA-Profiler: A brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. International Journal of Well-Being, 6(3), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v6i3.526

Chandra, R. M., Arora, L., Mehta, U. M., Asnaani, A., & Radhakrishnan, R. (2016). Asian Indians in America: The influence of values and culture on mental health. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 22, 202–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2015.09.011

Chaudhuri, S., Arora, R., & Roy, P. (2020). Work-Life balance policies and organisational outcomes–A review of literature from the Indian context. Industrial and Commercial Training, 52(3), 155–170.

Clarke, A., Amundson, N., Niles, S., & Yoon, H. J. (2018). Action-oriented hope: An agent of change for internationally educated professionals. Journal of Employment Counseling, 55(4), 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1002/JOEC.12095

Cui, C., Yu, S., & Huang, Y. (2023). His house, her house? Gender inequality and homeownership among married couples in urban China. Cities, 134, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.104187

Day, L. E. (2003). Culture shock and beyond: The experiences of foreign wives of foreign graduate students and postdoctoral fellows sojourning at Rutgers University. New Jersey: Doctoral dissertation, Rutgers University.

deTurck, M. A., & Miller, G. R. (1986). Conceptualizing and measuring social cognition in marital communication: A validation study. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 14(2), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909888609360306

Diwan, S., Jonnalagadda, S. S., & Balaswamy, S. (2004). Resources predicting positive and negative affect during the experience of stress: A study of older Asian Indian immigrants in the United States. The Gerontologist, 44(5), 605–614. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/44.5.605

Eekhout, I., De Vet, H. C., Twisk, J. W., Brand, J. P., de Boer, M. R., & Heymans, M. W. (2014). Missing data in a multi-item instrument were best handled by multiple imputation at the item score level. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(3), 335–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.09.009

Field, A. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics (5th ed.). SAGE.

Frijters, P., Haisken-DeNew, J. P., & Shields, M. A. (2004). Money does matter! Evidence from increasing real income and life satisfaction in East Germany following reunification. American Economic Review, 94(3), 730–740.

Gawlick, M., (1997). Adaptation strategies of second generation Asian Indians. Paper presented at the 1997 Conference on Asian Studies on the Pacific Coast, Asilomar, CA.

Graham, J. M., Diebels, K. J., & Barnow, Z. B. (2011). The reliability of relationship satisfaction: A reliability generalization meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022441

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Sage. https://doi.org/10.2307/2066725

Improve The Dream. (n.d.). Documented dreamers. https://www.improvethedream.org/. Accessed 8 May 2023

Jansen, E., Frantz, I., Hutchings, J., Lachman, J., Williams, M., Taut, D., Baban, A., Raleva, M., Lesco, G., Ward, C., Gardner, F., Fang, X., Heinrichs, N., & Foran, H. M. (2021). Preventing child mental health problems in southeastern Europe: Feasibility study (phase 1 of MOST framework). Family Process, 61(3), 1162–1179. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12720

Kim, B. S. K., Li, L. C., & Liang, C. T. H. (2002). Effects of Asian American client adherence to Asian cultural values, session goal, and counselor emphasis of client expression on career counseling process. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 49(3), 342–354. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.49.3.342

Kwena, Z. A., Bukusi, E. A., Turan, J. M., Darbes, L., Farquhar, C., Makokha, C., & Baeten, J. M. (2022). Effects of the waya intervention on marital satisfaction and HIV risk behaviors in Western Kenya: A pre-post study design. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(8), 3689–3701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02180-9

Le, B. M., & Impett, E. A. (2013). When holding back helps: Suppressing negative emotions during sacrifice feels authentic and is beneficial for highly independent people. Psychological Science, 24(9), 1809–1815. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613475365

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress Scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behavior Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u

Ma, K. (2021). Acculturation stress and depression among first-year international graduate students from China and India in the US. College Student Journal, 55(1), 104–118.

Mahendra, V., & Agarwal, G. (2016). Quality of life, psychological impairment, and resilience among employment-restricted immigrants. Indian Journal of Health and Wellbeing, 7(11), 1042–1047.

Martens, V. P., & Grant, P. R. (2008). A needs assessment of international students’ wives. Journal of Studies in International Education, 12(1), 56–75.

Miville, M. L., & Constantine, M. G. (2007). Cultural values, counseling stigma, and intentions to seek counseling among Asian American college women. Counseling and Values, 52(1), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-007x.2007.tb00083.x

Moore, S., & Diener, E. (2019). Types of subjective well-being and their associations with relationship outcomes. Journal of Positive Psychology and Wellbeing, 3(2), 112–118.

Panjwani, S., Manyam, S. B., & Prasath, P. R. (2021). The impact of immigration status on the quality of life among Asian Indians in the United States of America. Journal of Asia Pacific Counseling, 11(2).

Perry-Jenkins, M., & Crouter, A. C. (1990). Men’s provider role attitudes: Implications for household work and marital satisfaction. Journal of Family Issues, 11(2), 136–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251390011002002

Pillalamarri, A. (2019). Where did Indians come from, Part 4: How unique is Indian society? The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2019/02/where-did-indians-come-from-part-4-how-unique-is-indian-society/. Accessed 8 May 2023

Radhika, M. B. (2016). Visa wives: Emigration stories of Indian women in the US. Random House India.

Rajkumar, S. (1991). Mental health services in India. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 18, 41–55.

Rehman, U., Shahnawaz, M. G., Khan, N. H., Kharshiing, K. D., Khursheed, M., Gupta, K., ... & Uniyal, R. (2021). Depression, anxiety and stress among Indians in times of Covid-19 lockdown. Community Mental Health Journal, 57(1), 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00664-x

Ross, C. E. (1991). Marriage and the sense of control. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53(4), 831–838. https://doi.org/10.2307/352990

Sarmistha, U. (2019). Chai, Samosa, and H-1B visa: Indian IT workers in the United States. In: Transnational Immigrants. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8542-1_1

Schumm, W. R., Nichols, C. W., Schectman, K. L., & Grigsby, C. C. (1983). Characteristics of responses to the Kansas marital satisfaction scale by a sample of 84 married mothers. Psychological Reports, 53(2), 567–572. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1983.53.2.567

Seligman, M. E. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Simon and Schuster.

Shoichet, C. C. E. (2021). Why these students are dreading their 21st birthdays. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2021/11/27/us/documented-dreamers/index.html. Accessed 8 May 2023

Siddiqui, N. A., Fatima, S., Bint Taj, F., Shahid, A., & Moosa, Z. A. (2020). Depression among undergraduate medical and engineering students: A comparative study. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 36(5), 1096. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.36.5.1858

Suppal, P. G., Roopnarine, J. L., Buesig, T., & Bennett, A. (1996). Ideological beliefs about family practices: Contemporary perspectives among North Indian families. International Journal of PsycholOgy, 31(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/002075996401197

Tummala-Narra, P., Gordon, J., Gonzalez, L. D., de Mello Barreto, L., Meerkins, T., Nguyen, M. N., Medzhitova, J., & Perazzo, P. (2019). Breaking the silence: Perspectives on sexual violence among Indian American women. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 10(4), 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1037/aap0000159

US. Citizenship and Immigration Services. (2018). H-1B petitions by gender and country of birth: Fiscal year 2018. https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/reports/h-1b-petitions-by-gender-country-of-birth-fy2018.pdf. Accessed 8 May 2023

US. Citizenship and Immigration Services. (2021). Employment authorization for certain H-4 dependent spouses. https://www.uscis.gov/working-in-the-united-states/temporary-workers/h-1b-specialty-occupations-and-fashion-models/employment-authorization-for-certain-h-4-dependent-spouses. Accessed 8 May 2023

Vijayakumar, P. B., & Cunningham, C. J. L. (2019). An indentured servant: The impact of green card waiting time on the life of highly skilled Indian immigrants in the United States of America. Industrial and Organizational Psychology Translational Research and Working Papers. https://scholar.utc.edu/iopsy/2. Accessed 8 May 2023

Wang, W. (2021). Immigrant families are more stable. Institute for Family Studies. https://ifstudies.org/blog/immigrant-families-are-more-stable. Accessed 8 May 2023

Wong, E. C., & Miles, J. N. (2014). Prevalence and correlates of depression among new US immigrants. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 16, 422–428.

Yellig, A. (2011). The experiences of married international graduate students and their accompanying non-student spouses in the US culture: A qualitative study. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/485. Accessed 8 May 2023

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Richa Bhatia and Netra Chavan for their assistance with participant recruitment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Prasath, P.R., Bhat, C.S. & Manyam, S.B. Married Asian Indians on H-1B and H-4 Visas in the US: an Exploration of Depression, Anxiety, Stress, Well-being, and Marital Satisfaction. Int J Adv Counselling 45, 518–536 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-023-09512-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-023-09512-5