Abstract

In the design of long-term care systems, preferences can serve as an essential indication to better tailor services to the needs, wishes and expectations of its consumers. The aim of this systematic review was to summarize and synthesize available evidence on long-term care preferences that have been elicited by quantitative stated-preference methods. The databases PubMed and Web of Science were searched for the period 2000 to 2020 with an extensive set of search terms. Two independent researchers judged the eligibility of studies. The final number of included studies was 66, conducted in 19 different countries. Studies were systematized according to their content focus as well as the survey method used. Irrespective of the heterogeneity of studies with respect to research focus, study population, sample size and study design, some consistent findings emerged. When presented with a set of long-term care options, the majority of study participants preferred to “age in place” and make use of informal or home-based care. With increasing severity of physical and cognitive impairments, preferences shifted toward the exclusive use of formal care. Next to the severity of care needs, the influence on preferences of a range of other independent variables such as income, family status and education were tested; however, none showed consistent effects across all studies. The inclusion of choice-based elicitation techniques provides an impression of how studies operationalized long-term care and measured preferences. Future research should investigate how preferences might change over time and generations as well as people’s willingness and realistic capabilities of providing care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Population aging, especially in developed countries, has long been recognized as a global phenomenon, with varied magnitude and projections worldwide. With the increasing population of older adults, substantial pressures are placed on national health and social care systems to adequately prepare for future challenges. The population of older adults aged 80 years or above is predicted to rise globally from 137 million in 2017 to 425 million in 2050 (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division 2017). As an increase in age often coincides with an increasing likelihood of becoming care dependent, one major challenge that emerges is the delivery and financing of long-term care (LTC). In Europe, expenditure on LTC is expected to increase by 80% from 2015 to 2060 (Global Coalition on Aging 2018). According to the latest calculations of 2019, population aging will lead to an increase in the number of consumers of LTC services (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division 2019).

When a person becomes care-dependent and requires support from others, that person can generally either receive care in a home-based, community, or institutional setting. In a home-based setting, in most instances, one or more informal caregivers are actively involved in providing care. Formal caregiving provided by a professional service often complements informal caregiving in a home-based setting, however, formal caregivers could also be the sole care-provider. The proportion of informal to formal caregiving varies internationally. This can be partly explained by the manner in which LTC systems are organized, which differ substantially across countries with regard to their funding sources, entitlements, service providers, access, LTC workforce, and quality control measures (Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety 2020). Additional influencing factors might be diverging views on the responsibility for providing care (family vs. government), different normative beliefs and perceived barriers to caregiving as well as individual willingness to provide care (Hoefman et al. 2017). Other societal changes, such as increasing employment rates of women, larger geographical distances between family members, and a growing number of single-person households, might also play an important role (Broese van Groenou and de Boer 2016). Such societal changes, alongside demographic developments and a rising demand for high-quality care, increase the pressure for national governments to act and establish sustainable and affordable LTC systems (Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety 2020).

In the designing of LTC systems, preferences can serve as an important indication to better tailor services to the needs and wishes of its consumers. Recently, there has been an increase in the involvement of patients and the general public in healthcare decision-making (Coulter 2012; Litva et al. 2002). In systems with limited resources, it is important to know which aspects of LTC are most and least important to people. Integrating people’s preferences in the design of services and products has also been linked to improved quality of care, quality of life, and overall well-being (Swift and Callahan 2009). Stated preference (SP) methods are used to ask participants directly about their preferences. Quantitative techniques can be used to infer people’s preferences by measuring a change in their utility function. As people are asked to trade-off between different aspects of care, it is possible to generate a ranking of said preferences. Examples of SP methods are contingent valuation (CV), best–worst scaling (BWS), discrete choice experiment (DCE), and other ranking or rating techniques (Klose et al. 2016). In the field of older adult care, SP methods have been increasingly applied since the last 10 to 15 years.

Preferences in the field of older adult care are multifaceted. It depends on multiple factors such as the study population, country in question, and the study’s perspective and focus. The broad thematic use of SP studies in the field of older adult care is mainly motivated by the complexity of LTC. Therefore, some studies have investigated preferences for specific LTC services (e.g., home-based care packages) in order to make preference-based suggestions for the improvement of LTC service designs (Lehnert et al. 2018; Chester et al. 2017, Kampanellou et al. 2019). Thereby, LTC services are decomposed into a set of attributes in order to measure underlying preferences with the help of the choices made by the respondents. Other studies used instruments to measure caregiver’s outcomes or investigate the suitability of different forms of LTC, providing an indirect measure of what LTC should look like according to people’s preferences (Al-Janabi et al. 2011; Milte et al. 2018a). In a recent scoping review by Lehnert et al. (2019), stated preferences for LTC were reviewed and summarized. It identified 12 qualitative, 40 quantitative, and seven mixed-methods studies in the field from a database search in February 2016. This systematic review builds upon the scoping review by additionally capturing the period from February 2016 to October 2020 and including preferences for nursing home as well as dementia care. The aim of this review is to summarize and synthesize available evidence on LTC preferences that have been elicited by quantitative SP methods.

Methods

A systematic literature review was performed to identify original SP studies in the field of older adult care. Among others, these studies measure people’s willingness to provide care or their preferences for different LTC services (informal or formal). The systematic review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al. 2009).

Search strategy and information sources

The literature search was conducted in September 2019 and updated in October 2020 using the scientific databases, PubMed and Web of Science. The search strategy combined English terms for older adult care [care OR nursing OR elderly care OR long-term care OR LTC OR home care OR older adult care] in search block A with search terms for SP elicitation methods [stated preference(s) OR time trade-off OR TTO OR standard gamble OR conjoint OR contingent valuation OR discrete choice OR DCE OR willingness-to-pay OR WTP OR analytic hierarchy process OR AHP OR choice model OR best–worst scaling OR BWS OR willingness-to-accept OR WTA OR multi-criteria decision analysis OR MCDA OR multi-attribute utility OR MAUT] in search block B. Search terms for block B were selected with the help of the literature survey on methods to perform systematic reviews of patient preferences by Yu et al. (2017). The Boolean operator “AND” combined the search terms of block A and B. Database-specific adjustments were made in block A in Web of Science by leaving out the search terms “care” and “nursing,” as these yielded a very high number of unspecific search hits in the database. Only one database-specific search filter was used in PubMed, specifically limiting the species to only humans. The timeframe was set to exclude studies published prior to 2000.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

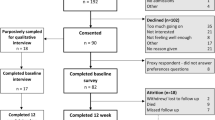

The selection process was based on a set of pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies were deemed eligible for inclusion if they (1) reported peer-reviewed, original quantitative data using SP methods such as DCE, BWS, CV, or other ranking or rating techniques, (2) were published in English or German, (3) were published in or after the year 2000, and (4) were focused specifically on LTC preferences of older adults in need of care. Studies were excluded if they (1) did not report original, peer-reviewed data (such as poster sessions, book chapters, reviews, reports and letter to the editors), (2) used qualitative or revealed preference methods to elicit preferences, (3) were published prior to 2000, or (4) focused on illness-related care, end-of-life care, or telecare. Studies focusing on specific illnesses or palliative care were excluded because of their tailored care needs and medical interventions that differ from general older adult care. Care for common cognitive and physical signs of old age such as incontinence, memory loss, and dementia were exempted from illness-related care and therefore included in this review. Based on these criteria, two independent researchers (de Jong, Damm) made a first selection by screening the titles and abstracts. Following the first selection, full texts of the remaining studies were screened and judged for inclusion. In case of disagreement, a third reviewer was consulted. Reference lists of included studies were hand-searched by the lead author.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

Key characteristics of each study were extracted and collected in an extensive Microsoft Excel file. The extracted characteristics included the year of publication, country, aim of the study, characteristics of the study participants, sample size, instrument design including the software used, attributes and levels if applicable, data analysis, and key findings. A summary of key characteristics is presented in Table 1 and a detailed overview of selected characteristics is presented in Tables 2, 3, and 4. Tables 3, 4 and 5 additionally include the content-related assignment of each study into one of the four main entities (or “blocks”) identified below. The quality of this systematic review was ensured using the PRISMA 2009 Checklist (Moher et al. 2009). The quality of the included studies was assessed using the PREFS (Purpose, Respondents, Explanation, Findings, Significance) checklist (Joy et al. 2013). According to the PREFS checklist, studies are ranked on a scale from zero to five, with five indicating the highest methodological quality. Two researchers (de Jong, Damm) independently judged the quality of the studies. Table 5 presents an overview of the quality scores of the included studies.

Results

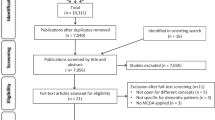

In total, the search strategy yielded 8,516 articles to be screened for eligibility. After the removal of duplicates, two independent researchers screened and assessed 6,764 titles and abstracts with a set of predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. As a result, 122 remaining full texts were assessed, of which 59 were ultimately included. Full texts with a different methodological or thematic focus, for instance, care needs or preferences for LTC insurance coverage were excluded. The reference lists of the included studies were additionally screened, which yielded another nine studies to be included. In total, 68 studies were included. The study selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

Results of the quality appraisal

The results of the quality assessment are presented in Table 1. According to the checklist, most studies were deemed to have a good or very good quality. Three studies adequately addressed all five elements of the PREFS Checklist, and a further 46 addressed four out of five elements. Most often, studies did not report any evidence on differences between responders and non-responders of the sample, thereby neglecting to adequately assess potential selection bias. As preference studies often do not possess information on non-responders, other reviews have decided to disregard this area of the checklist from the appraisals (Lepper et al. 2020). Seventeen additional studies adequately reported three out of five elements of the checklist. Two studies adequately reported on less than three elements and were therefore excluded from the final sample (Chan et al. 2000, Li and Wang 2016). The results of the remaining 66 studies are described in the following sections.

Description of included studies

The included studies were published between the year 2000 and 2020 and the majority were conducted in China (n = 16) and the USA (n = 18). Two studies collected data from multiple countries, particularly from the UK, Spain, USA, and Sweden (Gustavsson et al. 2010) and Germany and the USA (Pinquart and Sörensen 2002). In total, studies conducted in 19 different countries were included. An overview of study characteristics is shown in Table 1. Barring two studies that investigated preferences over time (Wolff et al. 2008; Abbott et al. 2018), the remaining used a cross-sectional design. The sample size ranged from 28 (Chester et al. 2017) to 244,718 respondents (Roberts and Saliba 2019). The share of women in the sample ranged from 38.2% (Qian et al. 2017) to 100% (Kasper et al. 2000; Wolff et al. 2008). The majority of the included studies (n = 38) surveyed a sample of the general population, mostly older adults aged 65 years and above. Eight studies included care-dependent older adults and eight informal caregivers or family members. Ten studies used multiple groups of study participants for their analysis, specifically, care-dependent older adults as well as their primary caregivers or family members as proxy. Most often (n = 44) the surveys were administered via telephone or face-to-face interviews to enable participants to ask questions. Next to descriptive statistics, most studies additionally used inferential statistics to analyze their findings. Multinomial logistic regression, conditional logistic regression, and mixed logit models were most frequently used.

The included studies (n = 66) investigated different facets of LTC. For this systematic overview, studies were grouped into four main entities:

-

(1)

Preferences for different LTC options and factors influencing these preferences: Twenty-eight studies exclusively focused on the preferred type of care in case the participants became care-dependent and its influencing factors (e.g., age, gender) that might explain respondent’s preferences. Participants were asked to choose their preferred LTC option from a set of pre-specified categories or show their level of agreement to a set of statements concerning different LTC options (usually Likert scales). Binary-choice questions investigated respondent’s willingness to make use of only one type of LTC, e.g., nursing home care.

-

(2)

Suitability of different types of care services and settings for hypothetical patient outcomes and factors influencing such preferences: In the majority of the studies (n = 11), hypothetical vignettes were used that depicted individuals in need of care, while the type and severity of impairment differed between studies. Physical and cognitive impairments were mostly compared. Participants were then asked to put themselves in the position of the hypothetical person in need of care and state the appropriate LTC option. The influencing factors in most studies were then analyzed.

-

(3)

Preferences for the design and structure of specific LTC services: Twenty-one studies focused on a singular type of LTC to make preference-based suggestions for the improvement of specific LTC service designs. Participants were mostly asked to make trade-offs between different attributes of the depicted LTC service, e.g., the cost and care time per day of two home-based care packages. DCE and conjoint analyses were most frequently used. When reported, the number of included attributes in the experimental designs ranged from four to ten. Studies either focused on informal care, home-based, and community-based care or LTC facilities.

-

(4)

Impact of LTC services to value quality of life or quality of care instruments: Preference-based instruments typically incorporate a scoring algorithm that has been elicited by using various SP methods and can be used to measure caregiver’s outcomes.

Block 1.1: Preferences for different LTC options

Twenty-eight studies exclusively asked respondents for their preferred LTC option in case of a care dependency situation and investigated the impact of a variety of independent variables on the choices of respondents. The majority of these studies were conducted in China (n = 12) and the USA (n = 7). The most preferred care option by almost all (60 to 85%) participants was home care, either provided by relatives or professionals (Chung et al. 2008; Costa-Font et al. 2009; Eckert et al. 2004; Fernandez-Carro 2016; Fu et al. 2017; Filipovič Hrast et al. 2019; Hajek et al. 2017; Imamoğlu and Imamoğlu 2006; Laditka et al. 2001; Liu et al. 2019; Rong et al. 2019; Spangenberg et al. 2012; Wei and Zhang 2020; Zeng et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2017; Fisher 2003; Kim and Choi 2008; Wang et al. 2004; Iwasaki et al. 2016). Some studies further differentiated between receiving care and living in one’s own home or the relative’s home, of which the option of remaining in one’s own home was preferred by all except in the study by Fernández-Carro (2016). Here living in the relative’s home was preferred by 56% of respondents compared to 21% of respondents preferring to be cared for in their own home. Pinquart and Sorenson (2002) found that older respondents preferred informal or mixed support for short-term care dependency and more formal assistance in the case of LTC needs. Seven studies investigated preferences for community-based care. On average, 5 to 10% of the respondents preferred to use community services in case of a care dependency (Chung et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2019; Wei and Zhang 2020; Zhang et al. 2017). In the remaining three studies, willingness to use community services was higher, documenting up to 38.7% (Laditka et al. 2001; Rong et al. 2019; Zeng et al. 2019).

The third LTC option most often investigated was institutional care, particularly, respondent’s intention or willingness to enter a nursing home when in need of care. Acceptability of institutional care varied greatly between studies. In most studies, 2 to 20% of respondents expressed their willingness to enter a care home in the future (Chung et al. 2008; Costa-Font et al. 2009; Eckert et al. 2004; Fernandez-Carro 2016; Fu et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2019; Wei and Zhang 2020; Zeng et al. 2019; Huang et al. 2018; Kim and Kim 2004; Qian et al. 2017, 2018; Chou 2010; Wang et al. 2004; Iwasaki et al. 2016). The lowest acceptability rate was found in a Chinese survey with 14,373 participants aged 60 and above with a willingness of less than 3% to enter a nursing home (Zhang et al. 2017). A study by Hrast et al. (2019) (72%) in Slovenia recorded the highest acceptability rates.

Block 1.2: Factors influencing preferences for different LTC options

To better understand the LTC choices of respondents, many of the included studies investigated the influence of a variety of independent variables on such choices. Which independent variables were looked at was, however, heterogenous across studies and either chosen research-focused (n = 19) or with the help of Anderson’s model of health services utilization (n = 9). When studies applied Anderson’s model, independent variables were most often grouped into predisposing (e.g., age, sex, nationality, educational level), enabling (e.g., income, number of children, family network, social support) and need (e.g., self-rated health, cognitive function, number of chronic diseases) factors on the choices of respondents. A list of independent variables that each study investigated can be found in Table 2.

Preferences for home care were positively associated with lower self-rated care (OR: 1.3), no need of care (OR: 5.5), and providing care for family members or friends (OR: 1.6) in a German study by Hajek et al. (2017). Expectations of reciprocity and strong family bonds might explain such preferences. In the Chinese study by Liu et al. (2019), older adults living in rural areas preferred home-based services and receiving support from family members. Eckert et al. (2004) found a higher education (OR: 1.78) and being female (OR: 1.55) increased preference for care by kin. Contrastingly, Fernandez-Carro (2016) found that factors like being widowed (Coeff: 0.09), a low educational (Coeff: 0.15), and financial profile (Coeff: 0.28), and already living at children’s home (Coeff: 0.14) significantly increased the likelihood of choosing co-residence at a relative’s home. Compared to home care, those respondents who preferred community-based care were in need of visiting a medical care team (OR: 2.12) and needed self-care information (OR: 4.39) (Chung et al. 2008). A study involving 169 older caregivers in the USA found a significant gender difference for being able to afford to pay for services. It found that almost 60% of male respondents and 33.9% of female respondents would rather use community services than ask family for help (Laditka et al. 2001).

When it comes to respondents’ willingness to use institutional care services, several studies found that poorer health status was positively associated with such willingness (Wei and Zhang 2020; Rong et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2017; Jang et al. 2008; Kim and Kim 2004; Hajek et al. 2017). Marital status (unmarried or widowed) additionally positively influenced respondents’ willingness to enter a care home (Wei and Zhang 2020; Zeng et al. 2019; Rong et al. 2019; Qian et al. 2018; Fernandez-Carro 2016). Income was found to have a statistically significant impact on respondents’ choice to receive institutional care in several studies. Studies by Wei and Zhang (2020), Qian et al. (2018), and Dong et al. (2020) found that respondents with a higher income were more likely to prefer an institutional setting. However, Kim and Kim (2004) and Kim and Choi (2008) found that the opposite was true. A higher education was also found to positively influence respondents’ willingness to enter a care home (Wei and Zhang 2020; Qian et al. 2018; Fernandez-Carro 2016; Chou 2010; Dong et al. 2020). Fewer children or a poor relationship with one’s children increased respondents’ willingness to move to a LTC facility in the future (Kim and Kim 2004; Qian et al. 2018). Having an acquaintance already living in a nursing home (OR: 2.80) additionally increased respondents’ willingness to enter a nursing home (Jang et al. 2008). A Chinese study investigating age-cohort differences on the intention toward old age home placement found that middle-aged and older Chinese respondents tended to have more positive attitudes toward old age home and were willing to enter a nursing home than younger participants (Tang et al. 2009).

Block 2.1: Suitability of different types of care services and settings for hypothetical patient outcomes

Nieboer et al. (2010) elicited the preferences of the general Dutch elderly population (n = 1,082) for LTC services by means of a DCE. In each choice set, respondents had to choose the most suitable care package (A vs. B) for a specific patient. Four patient profiles were presented: physically frail elderly, elderly with dementia, and then both groups either living alone or with a partner. Irrespective of the group, the greatest value was attached to a regular care provider and the availability of transportation services. For physically frail elderly, transportation services were deemed most important (living alone coeff: -0.572, WTP: €120; living with a partner coeff: -0.459, WTP: €76). For older patients with dementia who were living alone, the most important attribute was living in an apartment building in close proximity of the caregiver (Coeff: 0.498, WTP: €177). For patients with dementia who were living with a partner, the most important attribute was a regular care provider (Coeff: -0,493, WTP: €88). Generally, all services were deemed more important to care-dependent people living alone compared to those living with a partner. Living in a care or nursing home was the least preferred living situation, except for dementia patients living alone.

Additionally, 14 studies examined the suitability of LTC settings for different hypothetical patient outcomes. Of these studies, two applied the conjoint analysis method (Fahey et al. 2017; Robinson et al. 2015), one the time-trade off method (Guo et al. 2015), and the remaining 11 a vignette survey. Fahey et al. (2017) found that respondents placed the greatest weight on reducing strain on family members and wanting to stay at home with support for as long as possible. Robinson et al. (2015) found that the most important attribute of the respondents was going home with care support. Half of the respondents were additionally willing to sacrifice one year or more of their life to be able to stay at home with support. Guo et al. (2015) found that home care was strongly preferred compared to nursing home for mild to moderate physical impairments. Such preferences were found to decrease by 0.04 quality of life weight for every additional ADL impairment. With increasing severity of impairment, especially of a cognitive nature, preferences tended to shift toward nursing home care.

In the remaining studies, vignettes depicting situations with hypothetical older adults in need of care were used. In most cases, the severity of the depicted care dependency was altered in the vignettes and respondents were asked to choose an appropriate LTC option for that person. The majority of the vignette surveys were conducted in the USA and differentiated the hypothetical care dependencies into physical and cognitive impairments (Bradley et al. 2004; McCormick et al. 2002; Min 2005; Min and Barrio 2009; Wolff et al. 2008). In case of IADL needs or a hypothetical hip fracture, respondents preferred to make use of informal or formal home-based care services (Wolff et al. 2008; McCormick et al. 2002; Min 2005; Min and Barrio 2009; Kasper et al. 2000, 2019). While McCormick et al. (2002) found similar preferences between Japanese-Americans and Caucasian-Americans in case of a hip fracture, Min and Barrio (2009) found that 83.3% of non-Latino white older adults expressed a preference to rely on formal or paid help compared to 54.6% of Mexican-Americans. In terms of cultural values, 73.3% of Mexican–American respondents agreed that care should be provided by family members and not by outsiders as compared to 32.6% of non-Latino White respondents (Min and Barrio 2009). In a US study by Bradley et al. (2004), in the hypothetical case of cognitive and physical impairment, African-American respondents were more likely to use informal LTC (72.3%). In the hypothetical case of dementia or stroke, preferences shifted toward nursing home care or an exclusive use of formal care services (Min 2005; Wolff et al. 2008; Werner and Segel-Karpas 2016; Kasper et al. 2000). With increasing severity of impairment, preferences tended to also shift toward nursing home care (Carvalho et al. 2020; Santos-Eggimann and Meylan 2017). Adult children were more likely to recommend moving to a retirement facility than older adults (Caro et al. 2012).

Block 2.2: Factors influencing preferences for LTC settings for hypothetical patient outcomes

In case of a hip fracture, age (OR: 1.07) and being female (OR: 2.24) increased the likelihood of Japanese-American respondents choosing home healthcare (McCormick et al. 2002). In a sample of 144 Korean-Americans, being female (OR: 0.09), having a higher education (OR: 0.76), and having stronger traditional values (OR: 0.79) significantly increased the likelihood of choosing an informal instead of formal care arrangement for a possible hip fracture (Min 2005). With increasing severity of incontinence, the proportion of people choosing institutional care instead of home-based care increased significantly. Personal incontinence of respondents had no significant impact on their choice of LTC option (Carvalho et al. 2020). In three studies, race played a significant role in explaining preferences. Being African-American (OR: 2.41) and Mexican–American (OR: 4.6) increased the likelihood of turning to an informal caregiver in case of a care dependency situation (Bradley et al. 2004; Min and Barrio 2009). African-American respondents were less positive than white respondents about nursing home staff, trust, and quality (Bradley et al. 2004).

In case of dementia, age (OR: 0.96), being female (OR: 1.41), and marital status (OR: 0.53) significantly affected the intention of Japanese-Americans to use nursing home care (McCormick et al. 2002). In case of Alzheimer’s disease, institutional care was preferred by respondents with a higher education, better cognitive status, greater number of illnesses, and not wanting to become a burden on family (Werner and Segel-Karpas 2016). For a hypothetical stroke, independent decision-making style (OR: 7.96) increased the likelihood of choosing a mixed care arrangement instead of informal care. An independent decision-making style (OR: 9.83), having health insurance coverage (OR: 12.72), and greater IADL limitation (OR: 3.53) increased the odds of relying on all formal care (Min 2005).

Block 3: Preferences for the design and structure of specific LTC services

Home-based and community-based care

Six studies investigated people’s preferences for home-based services (package A vs. B) for care-dependent people by means of a DCE (Chester et al. 2017, Kaambwa et al. 2015, Kampanellou et al. 2019, Lehnert et al. 2018, Walsh et al. 2020, Chester et al. 2018). While Chester et al. (2017) and Kampanellou et al. (2019) asked British caregivers to people with dementia (PWD) for their appraisal, Kaambwa et al. (2015) and Chester et al. (2018) questioned care-dependent people as well as informal caregivers. Lehnert et al. (2018) and Walsh et al. (2020) surveyed a sample of the general population. Less rotation in the number of caregivers per month were valued as crucial by respondents in the DCE of Chester et al. (2017) and Lehnert et al. (2018). In the DCE by Lehnert et al., respondents were willing to pay up to 213.86€ per month for a regular caregiver. When it comes to dementia care, several studies have found specialized training and communication skills to be the most important attributes for respondents. In a second DCE by Chester et al. (2018), “support with personal feelings and concerns provided by a trained counsellor at home” (Coeff: 0.676, WTP: £31) and “information on coping with dementia provided by an experienced worker at home” (Coeff: 0.592, WTP: £27) were valued the highest. In the study by Walsh et al. (2020) “personalized communication with the person with dementia” (Coeff: 0.54, WTP: €135.45) was found to be one of the most important determinants of person-oriented home-care services for PWD. Guzman et al. (2019) investigated the type of communication skills. It found that non-verbal communication (eye contact, tone of voice, body language) had the greatest significance to the respondents. Especially implementing interventions or procedures promptly and completely (Coeff: 6.763) and listening attentively to verbalization of patients (Coeff: 4.732) was most important.

Loh and Shapiro (2013) assessed the willingness to pay for home- and community-based services (HCBS). On average, respondents were willing to pay up to $933.32 for HCBS per months. WTP varied across different HCBS programs, with the highest WTP of $1776.61 documented for Alzheimer Disease Initiative program (Loh and Shapiro 2013). Lehnert et al. (2018) found respondents of the German DCE were willing to pay up to €233.71 per month and up to €429.10 per month for high quality care and very high quality of care, respectively. Walsh et al. (2019) found respondents were willing to pay up to €154.18 for “20 h per week of publicly funded care hours” and up to €139.64 for “high flexibility of service provision.” Furthermore, Kampanellou et al. (2019) found that respondents ranked the attributes “respite care for you is available regularly to fit your needs” (Coeff: 1.292; WTP: £235) and “home care such as personal care and cleaning is provided regularly for as long as needed” (Coeff: 0.933; WTP: £170) to be the most important.

In the study by Kaambwa et al. (2015) the most preferred community aged care (CDC) package that was chosen across all subgroups with a probability of 0.124 was the one with multiple service providers as well as family members to provide day-to-day services. The individual (client) was responsible for managing funds. Another Chinese study by Xiang et al. (2019) found the provision of health care services the most important, of which regular health examination (mean priority: 1.51) and health counselling (mean priority: 2.46) were the most important. Culture-related activities were judged as the least important by the respondents, although it was deemed slightly more crucial by the male respondents compared to the women. Respondents’ education levels also influenced their answers. Respondents with a higher educational level placed greater importance on daily life assistance.

Long-term care facilities

Three studies examined people’s preferences for LTC facilities or nursing homes by means of a DCE (Milte et al. 2018b; Sawamura et al. 2015; Song et al. 2020). In an Australian study by Milte et al. 2018b, residents of nursing homes as well as family members as proxies were surveyed; the study focused on food preferences. The most important attribute of respondents was the taste of the food, whereby it was judged that it is crucial for the food that is provided to have an excellent taste (Coeff: 0.558, WTP: $24 per week). In the Japanese DCE by Sawamura et al. (2015), respondents had to choose between facility A and B for two different patient profiles, one with dementia and the other one with a fracture. Respondents valued the facility where relocation was not required as the highest even when the health of the patient deteriorates (dementia coeff: 1.67, fracture coeff: 1.36). Respondents with personal caregiving experience showed significantly greater preference for the availability of individual choice of daily schedule and meals. In the Chinese study by Song et al. (2020), older adults with the intention or willingness to live in a nursing home were asked to choose either between nursing homes A and B or neither of the options. The most important attributes for respondents were “location” and “care service”. The respondents preferred inner suburbs and regarded good care service as important.

In a large study by Roberts and Saliba (2019), assessment data of nursing homes was used to rank 16 daily care and activity services on a Likert scale from one to five. The latent class model showed that preferences could be grouped into four classes, namely “important” (38.3%), “activity” (27.1%), “care” (24.1%), and “unimportant” (10.4%). Race, ethnicity, cognition, and depression were found to be predicting values to determine the group to which the respondents were most likely to belong. African-American race and Hispanic ethnicity were predictors of membership to the first group, which ranked almost all care and activity preferences as important. Cognitive impairment and depression were predictive factors of belonging to the fourth group, in which respondents ranked more than half of daily care and activity preferences as unimportant.

In a survey study by Abbott et al. (2018), changes in preferences of 255 nursing home residents were examined over a period of three months. Sixteen of 72 preferences were rated as very or somewhat important by 90% or more of the residents. These preferences fell predominantly into the domain of self-dominion (n = 9) and enlisting others in care (n = 4). A total of 96.50% of respondents preferred having staff show respect to nursing home residents. When asked again after three months, the average agreement rate was 59% although 68 of 72 preferences had 70% or higher stability over the time period. Results reveal that residents who report high levels of importance at baseline are likely to report the same high preferences after the time period of three months. In a study by Przybyla et al. (2019), 214 senior Polish citizens were surveyed regarding their housing preferences. Willingness to move to housing options better tailored toward limited mobility was found in respondents living in larger cities. Based on the answers of the respondents, the preferred facilities at a senior housing estate included a 24 h medical care service (63%), a guarded estate (50%), having house cleaning services (48%), and a canteen (47%). A live-in caregiver was judged as important by less than 20% of respondents.

Informal care

Mentzakis et al. (2011) conducted a DCE in Scotland with 209 informal caregivers to estimate monetary valuations for various informal care tasks. Initially, respondents were asked to choose between two hypothetical informal care situations, with the opportunity to opt out in a second step and let a person of their choice take over. A three-class model was fitted and illustrated preference heterogeneity between these three groups. Monetary compensation to the caregiver was judged as more important by younger respondents than older adults. For the first class, the attribute “household tasks” was the most important, with the lower the number of hours of household tasks per week being preferred (Coeff: -0.0109). For the second and third class, “personal care” was the most important attribute, where a lower number of hours of personal care per week was preferred (Coeff: -0.0232 and -0.0704 respectively). Willingness to accept values were additionally calculated. For class 1, the only statistically significant value was for household tasks being valued £0.6 per hour. For class 2, a per hour value of £0.38 for personal care was estimated.

Several studies tried to explore the value of informal care by estimating the willingness-to-pay (WTP) for a reduction in informal caregiving time through contingent valuation method (Gervès et al. 2013; Gustavsson et al. 2010; Fu et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2020; König and Wettstein 2002). Three of these studies (Gustavsson et al. 2010; Gervès et al. 2013; König and Wettstein 2002) focused on informal care for Alzheimer’s disease or other mental disorders. Gervès et al. (2013) surveyed French informal caregivers of elderly care recipients with cognitive impairments. The authors found that negative influences on caregiver’s morale was associated with the ability of respondents to estimate a WTP value for a 1 h reduction in care time. About 45% of the respondents were, however, unable to estimate a WTP value; 19% were willing to pay ≤ €13, 23% between > €13 and ≤ €18 and 13% were willing to pay more than €18 to be replaced for one hour. Gustavsson et al. (2010) surveyed a total of 517 informal caregivers of elderly care recipients in four countries. Mean WTP was calculated for a 1 h reduction in care need per day. For the UK, Spain, Sweden, and the US, the estimated values were £105, £121, £59 and £144 per month, respectively. In a Swiss study by König and Wellstein (2002), 109 pairs of informal caregivers and PWD were interviewed. On average, informal caregivers of the sample were willing to pay 57,500 CHF (US$ 38,000) for the complete elimination of burden and around SRF 2,200 (US$ 1,500) per year for a reduction of self-rated burden from moderate to low. For a hypothetical cure, caregivers were willing to pay up to 29% of their wealth and up to 23% to prevent future worsening of the disease. In a Chinese study by Liu et al. (2020), WTP and WTA values for 1 h reduction or increase of the least preferred care tasks of 371 informal caregivers were estimated. The average WTP of the respondents for a 1 h reduction of the least-preferred care task per week was 25.31 CNY. The minimum WTA for having to provide another hour of their least-preferred care task per week was 38.66 CNY. In a study by Fu et al. (2019) the number of co-payment respondents were willing to pay for voucher schemes in Hong Kong was investigated. Older age, greater financial resources, and a positive attitude toward voucher schemes resulted in a higher WTP of respondents.

Block 4: Impact of LTC services on care-related quality of life and caregiver’s outcomes

Different instruments have been developed to measure care-related quality of life and caregiver’s outcomes to be used in economic evaluations. This provides an indirect measure of what caregivers wish for their LTC situation to look like. One of these preference-based index instruments is the Carer Experience Scale that was designed to capture the caring experience and consists of six domains, each with three levels. Al-Janabi et al. (2011) conducted a BWS experiment to estimate index values for England. For the surveyed informal caregivers, being able to do most of the activities you want outside caring (Coeff: 4.41) and getting a lot of support from family and friends (Coeff: 4.08) were selected most often as best.

The Consumer Choice Index–Six Dimension (CCI-6D) instrument was developed in Australia to assess the quality of care in nursing homes. Milte et al. (2018a, b) generated a scoring algorithm for the instrument by means of a DCE with 126 residents of nursing homes and 416 family member proxies. Always having the room set up to make the resident feel “at home” was the most important for residents (Coeff: 0.616). While this was equally important to family members (Coeff: 0.623), the most important item for family members was that care staff are always able to spend time with their care-dependent family member (Coeff: 0.648). The authors recommend using the resident scoring algorithm, as they have live experience and their preferences showed greater consistency across answers (Milte et al. 2018a).

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to summarize and synthesize available evidence on LTC preferences of older adults in need of care. For this purpose, a wide range of studies applying SP methods to elicit preferences were systematically searched. Sixty-six international peer-reviewed studies were included and relevant results were extracted. While this review focused exclusively on quantitative SP methods, the heterogeneous results of the included studies reflect the complexity of LTC. Even when the same methodology was applied, the studies differed with regard to their research focus, study population, sample size, analysis model, and study design. Studies conducted in 19 different countries were included, with a majority of studies conducted in Asia dealt with rapidly aging populations. The overview of attributes and levels used in the choice-based elicitation techniques (DCE, BWS, CA) provide an important impression on how the studies operationalized LTC and measured related preferences, as the choice of attributes is usually substantiated by extensive literature reviews and/or qualitative interviews with the target population.

Irrespective of the heterogeneity of studies, some consistent findings emerged. When presented with a set of LTC options, the majority of study participants preferred to “age in place” and make use of home-based services or informal care by family members in case of becoming care-dependent. Particularly for short-term or mild-to-moderate care needs (e.g., hip fracture), they generally preferred informal caregiving with some professional assistance if needed. Remaining in one’s own home was linked with maintaining independence, autonomy, control, and their social contacts. With increasing care-dependency needs, a shift in the preferences of study participants across all studies could be noticed toward the exclusive use of formal LTC services or nursing home care. For dementia patients, especially, nursing home care or a regular formal care provider at home was deemed important by respondents. Nevertheless, nursing home care was associated by many with a loss of freedom, independence, and dignity but preferred by some to not impose on family members in case of a greater care-dependency. Next to the severity of care needs, a few other independent variables were shown to influence LTC preferences, while none showed consistent effects across all studies. Being female, married with children, and already living with a partner or their children increased the likelihood of preferring informal or home-based care. A higher income, higher educational level, being unmarried or widowed, poorer health status, and having provided informal care in the past increased the likelihood of choosing nursing home care in the future.

The choice-based elicitation techniques showed that for home-based services, quality of care and less rotation in the number of caregivers per month were deemed to be crucial. In the selection of attributes, home-based packages tailored to informal caregivers to PWD placed a larger focus on the availability of respite and relaxation opportunities as well as sufficient support and coping strategies to deal with the disease. Specialized training and communication skills as well as support with personal feelings were very important to informal caregivers. For the design of LTC facilities, location, care services, individual choice of daily schedule, and excellent taste of served food were found to be the most important attributes for respondents. Even when focusing on one LTC service, attributes and levels differed greatly between studies. This aspect makes comparability difficult, however is attributable to the fact that country-specific conditions have been integrated into the particular survey designs. Nevertheless, the cost of services in terms of a co-payment played an important role and was integrated as an attribute in each of the 12 DCE studies.

Additionally, several contingent valuation studies assessed the value of informal care by estimating the WTP for a reduction in informal caregiving time. A dependency of such a WTP value on the financial status of the caregiver can be assumed and has been shown across studies. However, the influence of the care recipient's status (e.g., his or her health status), cultural and social backgrounds or country-specific care situations, have not yet been investigated and compared sufficiently. Nevertheless, studies also show that it may be difficult for respondents to provide a direct WTP or WTA value. Thus, indirect forms of questioning (e.g., DCE) may be an appropriate alternative, as shown in the study by Mentzakis et al. (2011).

Among all the choice-based elicitation techniques, DCE was mostly applied, enabling not only a ranking of the importance of attributes but also an assessment of which trade-offs respondents were willing to make for certain attributes. The use of conjoint analysis, AHP, DCE, and BWS to elicit LTC preferences is a relatively recent development as the vast majority of these studies have been published between 2015 and 2020. A major concern in the design and implementation of a DCE or conjoint analysis design is its complexity, comprehensibility, and feasibility. The fact that in more than 50% of these studies, older adults in need of care or older hospital patients were surveyed, sometimes in addition to informal caregivers, shows that these types of stated preference methods are not only suitable for targeting the general population. Preference elicitation techniques in the field of older adult care have largely been cross-sectional, measuring preferences at a single point in time. Thus, little is known about the changes in preferences across time and generations. The two studies in this review examining changes in preferences have done so in a period of three months or one year. Although extremely resource-intensive, further longitudinal studies could help understand changes in preferences.

Other reviews have tried to synthesize evidence on LTC preferences of dementia patients (Lepper et al. 2020), institutionalization factors for entering a nursing home for older adults (Luppa et al. 2010) or instruments for measuring outcomes within aged care (Bulamu et al. 2015). Such reviews underline the purpose of trying to reduce the complexity within the field of LTC by attempting to systematically reveal and condense the heterogeneity of results and studies. This systematic review builds upon the recent scoping review by Lehnert et al. (2019) by additionally capturing the period from February 2016 to October 2020 and including preferences for nursing home as well as dementia care. We included a total of 34 additional studies from 2016 to October 2020. The inclusion of these recent studies showcase the very dynamic research interest in LTC preferences. Additionally, two-thirds of the included DCE and conjoint analyses were conducted in this period. Such elicitation techniques have considerably increased in the last few years as a way to quantify preferences (Soekhai et al. 2019).

Implications for research and policy

In the design of LTC systems, the demand for preference data has increased over the last few years as a way to integrate people’s priorities, needs and expectations. National governments need to establish sustainable and affordable LTC systems to evolve with the on-going demographic developments. The heterogeneous methods and LTC operationalizations used in the included studies mirror the national LTC systems and their confrontation with LTC in general. Thus, comparing preferences across countries is onerous. National preference data should be consulted especially for improving policies and LTC structures. Against the background of changing social developments, studies are needed that investigate LTC preferences and needs from the perspective of care-dependent older adults as well as (potential) informal caregivers. Further research is needed on people’s willingness to care as well as their realistic capabilities to ease the immense physical and psychological strain most informal caregivers experience. As informal caregiving is still considered as an essential pillar of most LTC systems, willingness to care as an indicator of the informal care potential of each country is vital. Nevertheless, to avoid caregivers becoming the next generation of care-dependent people due to immense burden, LTC services should ideally be available to supplement informal care right from the beginning. Therefore, preference-based data on how LTC services such as home-based or nursing home care should look like is needed.

Conclusion

Irrespective of the heterogeneity of the included studies, the majority of study participants preferred to “age in place” and make use of home-based services or informal care by family members in case of becoming care-dependent. With increasing severity of functional and especially cognitive impairment, preferences shifted toward an exclusive use of formal care services. Several influencing factors were investigated and reported that might explain such preferences; however, none showed consistent effects across all studies. The inclusion of preference data in the design of LTC systems can constitute an important part in finding sustainable and affordable LTC solutions that specifically support caregivers and mirror the needs and wishes of people in need of care. As shown by the rapid rise in published studies in recent years, the research interest in LTC preferences is consistently increasing. Future research should additionally investigate the changes in preferences across time and generations as well as research people’s willingness to care and their realistic capability to care next to other responsibilities such as occupation and children in the household.

Data availability

The data generated during the current study are all presented in the publication.

References

Abbott KM, Heid AR, Kleban M, Rovine MJ, van Haitsma K (2018) The change in nursing home residents’ preferences over time. JAMDA 19(12):1092–1098

Al-Janabi H, Flynn TN, Coast J (2011) Estimation of a preference-based carer experience scale. MDM 31(3):458–468

Bradley EH, Curry LA, Mcgraw SA, Webster TR, Kasl SV, Andersen R (2004) Intended use of informal long-term care: the role of race and ethnicity. Ethn Health 9(1):37–54

Bulamu NB, Kaambwa B, Ratcliffe J (2015) A systematic review of instruments for measuring outcomes in economic evaluation within aged care. Health Qual Life Outcomes 13(1):1–23

Caro FG, Yee C, Levien S, Gottlieb AS, Winter J, McFadden DL, Ho TH (2012) Choosing among residential options: Results of a vignette experiment. Res Aging 34(1):3–33

Carvalho N, Fustinoni S, Abolhassani N, Blanco JM, Meylan L, Santos-Eggimann B (2020) Impact of urine and mixed incontinence on long-term care preference: a vignette-survey study of community-dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatr 20(1):1–12

Chan YF, Parsons RW, Piterman L (2000) Chinese attitudes to institutional care of their aged. a study of members from the Chung Wah association. Western Australia Aust Fam Physician 29(9):894–899

Chester H, Clarkson P, Davies L, Sutcliffe C, Roe B, Hughes J, Challis D (2017) A discrete choice experiment to explore carer preferences. QAOA

Chester H, Clarkson P, Davies L, Sutcliffe C, Davies S, Feast A, Hughes J, Challis D, HOST-D (Home Support in Dementia) Programme Management Group. (2018) People with dementia and carer preferences for home support services in early-stage dementia. Aging Ment Health 22(2):270–279

Chou RJ-A (2010) Willingness to live in eldercare institutions among older adults in urban and rural China: a nationwide study. Ageing Soc 30(4):583

Chung M-H, Hsu N, Wang Y-C, Lin H-C, Huang Y-L, Amidon RL, Kao S (2008) Factors affecting the long-term care preferences of the elderly in Taiwan. Geriatr Nurs 29(5):293–301

Costa-Font J, Elvira D, Mascarilla-Miró O (2009) Ageing in place’? Exploring elderly people’s housing preferences in Spain. Urban Stud Res 46(2):295–316

Coulter A (2012) Patient engagement—what works? J Ambul Care Manage 35(2):80–89

Dong X, Wong BO, Yang C, Zhang F, Xu F, Zhao L, Liu Y (2020) Factors associated with willingness to enter care homes for the elderly and pre-elderly in west of China. J Med 99(47):e23140

Eckert JK, Morgan LA, Swamy N (2004) Preferences for receipt of care among community-dwelling adults. J Aging Soc Policy 16(2):49–65

Fahey A, Ní Chaoimh D, Mulkerrin GR, Mulkerrin EC, O’Keeffe ST (2017) Deciding about nursing home care in dementia: a conjoint analysis of how older people balance competing goals. Geriatr Gerontol Int 17(12):2435–2440

Fernandez-Carro C (2016) Ageing at home, co-residence or institutionalisation? Preferred care and residential arrangements of older adults in Spain. Ageing Soc 36(3):586

Filipovič Hrast M, Sendi R, Hlebec V, Kerbler B (2019) Moving house and housing preferences in older age in Slovenia. Hous Theory Soc 36(1):76–91

Fisher C (2003) Long-term care preferences and attitudes among Great Lakes American Indian families: cultural context matters. Care Manag J 4(2):94

Fu YY, Guo Y, Bai X, Chui EWT (2017) Factors associated with older people’s long-term care needs: a case study adopting the expanded version of the Anderson Model in China. BMC Geriatr 17(1):1–13

Fu YY, Chui EW, Law CK, Zhao X, Lou VWQ (2019) An exploration of older Hong Kong residents’ willingness to make copayments toward vouchers for community care. J Aging Soc Policy 31(4):358–377

Gervès C, Bellanger MM, Ankri J (2013) Economic analysis of the intangible impacts of informal care for people with Alzheimer’s disease and other mental disorders. Value Health 16(5):745–754

Global Coalition on Aging (2018) Relationship-based home care: a sustainable solution for Europe's elder care crisis

Guo J, Konetzka RT, Magett E, Dale W (2015) Quantifying long-term care preferences. Med Decis Making 35(1):106–113

Gustavsson A, Jönsson L, McShane R, Boada M, Wimo A, Zbrozek AS (2010) Willingness-to-pay for reductions in care need: estimating the value of informal care in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 25(6):622–632

Hajek A, Lehnert T, Wegener A, Riedel-Heller SG, König H-H (2017) Factors associated with preferences for long-term care settings in old age: evidence from a population-based survey in Germany. BMC Health Serv Res 17(1):1–9

Hoefman RJ, Meulenkamp TM, de Jong JD (2017) Who is responsible for providing care? Investigating the role of care tasks and past experiences in a cross-sectional survey in the Netherlands. BMC Health Serv Res 17(1):477

Huang Z, Liu Q, Meng H, Liu D, Dobbs D, Hyer K, Conner KO (2018) Factors associated with willingness to enter long-term care facilities among older adults in Chengdu. China Plos One 13(8):e0202225

Imamoğlu Ç, Imamoğlu EO (2006) Relationship between familiarity, attitudes and preferences: Assisted living facilities as compared to nursing homes. Soc Indic Res 79(2):235–254

Iwasaki M, Pierson ME, Madison D, McCurry SM (2016) Long-term care planning and preferences among Japanese American baby boomers: comparison with non-Japanese Americans. Geriatr Gerontol Int 16(9):1074–1084

Jang Y, Kim G, Chiriboga DA, Cho S (2008) Willingness to use a nursing home: A study of Korean American elders. J Appl Gerontol 27(1):110–117

Joy SM, Little E, Maruthur NM, Purnell TS, Bridges JFP (2013) Patient preferences for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a scoping review. Pharmacoeconomics 31(10):877–892

Kaambwa B, Lancsar E, McCaffrey N, Chen G, Gill L, Cameron ID, Crotty M, Ratcliffe J (2015) Investigating consumers’ and informal carers’ views and preferences for consumer directed care: A discrete choice experiment. Soc Sci Med 140:81–94

K Kampanellou E, Chester H, Davies L, Davies S, Giebel C, Hughes J, Challis D, Clarkson P, HOST-D (Home Support in Dementia) Programme Management Group (2019) Carer preferences for home support services in later stage dementia. Aging Ment Health 23(1):60–68

Kasper JD, Shore A, Penninx B (2000) Caregiving arrangements of older disabled women, caregiving preferences, and views on adequacy of care. Aging Clin Exp Res 12(2):141–153

Kasper JD, Wolff JL, Skehan M (2019) Care arrangements of older adults: What they prefer, what they have, and implications for quality of life. Gerontologist 59(5):845–855

Kim H, Choi W-Y (2008) Willingness to use formal long-term care services by Korean elders and their primary caregivers. J Aging Soc Policy 20(4):474–492

Kim E-Y, Kim C (2004) Who wants to enter a long-term care facility in a rapidly aging non-western society? Attitudes of older Koreans toward long-term care facilities. JAGS 52(12):2114–2119

Klose K, Kreimeier S, Tangermann U, Aumann I, Damm K, RHO Group (2016) Patient-and person-reports on healthcare: preferences, outcomes, experiences, and satisfaction–an essay. Health Econ. Rev. 6(1):18

König M, Wettstein A (2002) Caring for relatives with dementia: willingness-to-pay for a reduction in caregiver’s burden. Expert Rev Pharmacoecom Outcomes Res 2(6):535–547

Laditka SB, Pappas-Rogich M, Laditka JN (2001) Home and community-based services for well educated older caregivers: gender differences in attitudes, barriers, and use. Home Health Care Serv Q 19(3):1–17

Lehnert T, Günther OH, Hajek A, Riedel-Heller SG, König HH (2018) Preferences for home-and community-based long-term care services in Germany: a discrete choice experiment. Eur J Health Econ 19(9):1213–1223

Lehnert T, Heuchert MA, Hussain K, Koenig H-H (2019) Stated preferences for long-term care: a literature review. Ageing Soc 39(9):1873–1913

Lepper S, Rädke A, Wehrmann H, Michalowsky B, Hoffmann W (2020) Preferences of cognitively impaired patients and patients living with dementia: a systematic review of quantitative patient preference studies. J. Alzheimer's Dis.:1–17

Li, X., and Wang, J. Fuzzy(2016) Comprehensive evaluation of aged community home-care service quality based on AHP. Atlantis Press

Litva A, Coast J, Donovan J, Eyles J, Shepherd M, Tacchi J, Abelson J, Morgan K (2002) ‘The public is too subjective’: public involvement at different levels of health-care decision making. Soc Sci Med 54(12):1825–1837

Liu Z-W, Yu Y, Fang L, Hu M, Zhou L, Xiao S-Y (2019) Willingness to receive institutional and community-based eldercare among the rural elderly in China. PLoS ONE 14(11):e0225314

Liu W, Lyu T, Zhang X, Yuan S, Zhang H (2020) Willingness-to-pay and willingness-to-accept of informal caregivers of dependent elderly people in Shanghai. China BMC Health Serv Res 20(1):1–11

Loh C-P, Shapiro A (2013) Willingness to pay for home-and community-based services for seniors in Florida. Home Health Care Serv Q 32(1):17–34

Luppa M, Luck T, Weyerer S, König H-H, Brähler E, Riedel-Heller SG (2010) Prediction of institutionalization in the elderly. A System Rev Age Ageing 39(1):31–38

McCormick WC, Ohata CY, Uomoto J, Young HM, Graves AB, Kukull W, Teri L, Vitaliano P, Mortimer JA, McCurry SM (2002) Similarities and differences in attitudes toward long-term care between Japanese Americans and Caucasian Americans. JAGS 50(6):1149–1155

Milte R, Ratcliffe J, Chen G, Crotty M (2018a) What characteristics of nursing homes are most valued by consumers? A discrete choice experiment with residents and family members. Value in Health 21(7):843–849

Milte R, Ratcliffe J, Chen G, Miller M, Crotty M (2018b) Taste, choice and timing: Investigating resident and carer preferences for meals in aged care homes. Nurs Health Sci 20(1):116–124

Min JW (2005) Preference for long-term care arrangement and its correlates for older Korean Americans. JAH 17(3):363–395

Min JW, Barrio C (2009) Cultural values and caregiver preference for Mexican-American and non-Latino White elders. J Cross Cult Gerontol 24(3):225

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 62(10):1006–1012

Pinquart M, Sörensen S (2002) Older adults’ preferences for informal, formal, and mixed support for future care needs: a comparison of Germany and the United States. Int J Aging Hum Dev 54(4):291–314

Qian Y, Chu J, Ge D, Zhang L, Sun L, Zhou C (2017) Gender difference in utilization willingness of institutional care among the single seniors: evidence from rural Shandong. China Int J Equity Health 16(1):1–9

Qian Y, Qin W, Zhou C, Ge D, Zhang L, Sun L (2018) Utilisation willingness for institutional care by the elderly: a comparative study of empty nesters and non-empty nesters in Shandong. China BMJ Open 8(8):e022324

Roberts TJ, Saliba D (2019) Exploring Patterns in Preferences for Daily Care and Activities Among Nursing Home Residents. J Gerontol Nurs 45(8):7–13

Robinson SM, Ní Bhuachalla B, Ní Mhaille B, Cotter PE, O’Connor M, O’Keeffe ST (2015) Home, please: a conjoint analysis of patient preferences after a bad hip fracture. Geriatr Gerontol Int 15(10):1165–1170

Rong C, Wan D, Xu C-M, Xiao L-W, Shen S-H, Lin J-M (2019) Factors associated with preferences for elderly care mode and choice of caregivers among parents who lost their only child in a central China city. Geriatr Gerontol Int 20(2):112–117

Royal commission into aged care quality and safety (2020) review of international systems for long-term care of older people. research paper 2

Santos-Eggimann B, Meylan L (2017) Older Citizens’ opinions on long-term care options: a vignette survey. JAMDA 18(4):326–334

Sawamura K, Sano H, Nakanishi M (2015) Japanese public long-term care insured: Preferences for future long-term care facilities, including relocation, waiting times, and individualized care. JAMDA 16(4):350-e9

Soekhai V, de Bekker-Grob EW, Ellis AR, Vass CM (2019) Discrete choice experiments in health economics: past, present and future. Pharmacoeconomics 37(2):201–226

Song S, de Wang ZhuW, Wang C (2020) Study on the spatial configuration of nursing homes for the elderly people in Shanghai: Based on their choice preference. Technol Forecast Soc Change 152:119859

Spangenberg L, Glaesmer H, Brähler E, Strauß B (2012) Use of family resources in future need of care preferences and expected willingness of providing care among relatives: a population-based study. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 55(8):954–960

Swift JK, Callahan JL (2009) The impact of client treatment preferences on outcome: A meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol 65(4):368–381

Tang CS, Wu AMS, Yeung D, Yan E (2009) Attitudes and intention toward old age home placement: A study of young adult, middle-aged, and older Chinese. Ageing Int 34(4):237–251

van Groenou B, Marjolein, de Boer A, (2016) Providing informal care in a changing society. Eur J Ageing 13(3):271–279

Walsh S, O’Shea E, Pierse T, Kennelly B, Keogh F, Doherty E (2020) Public preferences for home care services for people with dementia: A discrete choice experiment on personhood. Soc Sci Med 245:112675

Wang YC, Chung M-H, Lai KL, Chou CC, Kao S (2004) Preferences of the elderly and their primary family caregivers in the arrangement of long-term care. JFMA 103(7):533–539

Wei Y, Zhang L (2020) Analysis of the Influencing Factors on the Preferences of the Elderly for the Combination of Medical Care and Pension in Long-Term Care Facilities Based on the Andersen Model. IJERPH 17(15):5436

Werner P, Segel-Karpas D (2016) Factors associated with preferences for institutionalized care in elderly persons: Comparing hypothetical conditions of permanent disability and Alzheimer’s disease. J Appl Gerontol 35(4):444–464

Wolff JL, Kasper JD, Shore AD (2008) Long-term care preferences among older adults: a moving target? J Aging Soc Policy 20(2):182–200

World Population Ageing (2017). Highlights, ST/ESA/SER.A/397, New York

World Population Ageing (2019). Highlights, ST/ESA/SER.A/430, New York

Yu T, Enkh-Amgalan N, Zorigt G (2017) Methods to perform systematic reviews of patient preferences: a literature survey. BMC Med Res Methodol 17(1):166

Zeng L, Xu X, Zhang C, Chen L (2019) Factors influencing long-term care service needs among the elderly based on the latest anderson model: a case study from the middle and upper reaches of the yangtze river 4. Healthcare 7(4):157

Zhang L, Zeng Y, Fang Y (2017) The effect of health status and living arrangements on long term care models among older Chinese: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 12(9):e0182219

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant number 01EH1603A). The funding body had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or in the writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LDJ was responsible for study concept and design as well as implementation, analysis and interpretation of the literature research and for drafting a first manuscript version. KD contributed to the study concept and design, as well as implementation, analysis and interpretation of the literature search and drafting the manuscript. JZ contributed to the study concept and the drafting of the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Marja J. Aartsen.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Jong, L., Zeidler, J. & Damm, K. A systematic review to identify the use of stated preference research in the field of older adult care. Eur J Ageing 19, 1005–1056 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-022-00738-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-022-00738-7